Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

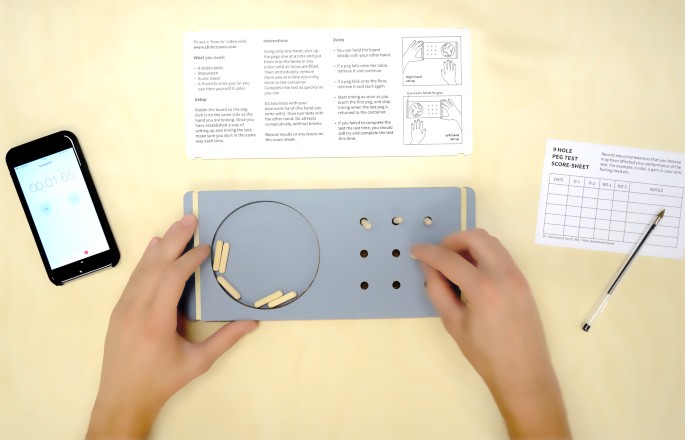

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Transformative Design – Methods, Types, Guide

Textual Analysis – Types, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Case Studies

Case studies are a popular research method in business area. Case studies aim to analyze specific issues within the boundaries of a specific environment, situation or organization.

According to its design, case studies in business research can be divided into three categories: explanatory, descriptive and exploratory.

Explanatory case studies aim to answer ‘how’ or ’why’ questions with little control on behalf of researcher over occurrence of events. This type of case studies focus on phenomena within the contexts of real-life situations. Example: “An investigation into the reasons of the global financial and economic crisis of 2008 – 2010.”

Descriptive case studies aim to analyze the sequence of interpersonal events after a certain amount of time has passed. Studies in business research belonging to this category usually describe culture or sub-culture, and they attempt to discover the key phenomena. Example: “Impact of increasing levels of multiculturalism on marketing practices: A case study of McDonald’s Indonesia.”

Exploratory case studies aim to find answers to the questions of ‘what’ or ‘who’. Exploratory case study data collection method is often accompanied by additional data collection method(s) such as interviews, questionnaires, experiments etc. Example: “A study into differences of leadership practices between private and public sector organizations in Atlanta, USA.”

Advantages of case study method include data collection and analysis within the context of phenomenon, integration of qualitative and quantitative data in data analysis, and the ability to capture complexities of real-life situations so that the phenomenon can be studied in greater levels of depth. Case studies do have certain disadvantages that may include lack of rigor, challenges associated with data analysis and very little basis for generalizations of findings and conclusions.

John Dudovskiy

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park in the US |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race, and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

A Case Study is a research method involving a detailed examination and in-depth description of a particular empirical case. This can be done in many different ways, and the unit of analysis can vary (a person, an institution, a country, etc.). Case Studies can include both quantitative and qualitative evidence (Stake, 1995) and typically rely on bringing together many different articles of evidence from various sources to illuminate the case as a whole.

Case Studies benefit from having a developed theoretical framework before data collection begins (Yin, 2003). At the same time, the Case Study approach allows flexibility and can be used in exploratory contexts. This can be attractive to the researcher because it allows data collection to begin immediately (though there remains a need to impose a theoretical structure in the analysis phase). Consequently, Case Studies can be conducted at different levels of formality and replicability (Hetherington, 2013).

The case study research design can be used to test whether theories and models work in real contexts of application (Shuttleworth, 2008) and, conversely, to generate hypotheses and theories.

Case Study: GO-GN Insights

Sarah Hutton used a hermeneutic phenomenological case study to illuminate a direct connection between undergraduate student participation in courses with a participatory OER authorship or open access publishing of student artefacts model, to the development of internal goals and deepened engagement:

“Participatory OER development and an open pedagogical model provide the potential for students to have autonomous control over the development of course content, fostering greater intrinsic motivation, and therefore more successful and transferable learning outcomes. The resulting analysis creates a compelling case for the adoption of OER materials beyond the affordability argument, further advocating for the engagement of students in open scholarship at the undergraduate level.”

Viviane Vladimirschi explored evidence-based guidelines in the context of Teacher Professional Development (TPD) for Brazilian fundamental education public school teachers by undertaking an intervention in one school. The main goal of the OER Development Program was to raise awareness and build teachers’ knowledge regarding OER adoption and use:

“The case study methodology used in this research is a very common approach within Educational Studies. It is also a fairly easy method to use and the analysis of multiple sources of data have the potential to not only generate new insights throughout the case study but also generate new theory. Theory-building is very well-suited to new research areas, which was the case of this research. However, there are some disadvantages to using this methodology. First, it is not possible to generalize the findings from a single case study. Second, achieving the balance between producing an overly complex theory or a narrow idiosyncratic theory is quite challenging. Theory generated by case studies must be testable, replicable and coherent. The TPD guidelines generated by this research are testable, replicable and pretty straightforward so I am confident I managed to achieve this balance. The Design Thinking for Educators approach (please note that it is not a method) that I used in this research for the face-to-face workshops I highly recommend to any researcher who wishes to undertake an intervention, especially in the K-12 sector. This approach not only enables researchers to gain more insight into potential solutions for introducing new professional practices, but also affords teachers multiple opportunities to participate in the process of determining how innovation may be best implemented. Its only potential disadvantage is that it requires a longer period of time of application during each of its distinct phases to obtain bottom-up buy-in to an innovation.”

Useful references for Case Studies: Hetherington (2013); Shuttleworth (2008); Stake (1995); Yin (2003)

Research Methods Handbook Copyright © 2020 by Rob Farrow; Francisco Iniesto; Martin Weller; and Rebecca Pitt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Res Methodol

The case study approach

Sarah crowe.

1 Division of Primary Care, The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Kathrin Cresswell

2 Centre for Population Health Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Ann Robertson

3 School of Health in Social Science, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Anthony Avery

Aziz sheikh.

The case study approach allows in-depth, multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in their real-life settings. The value of the case study approach is well recognised in the fields of business, law and policy, but somewhat less so in health services research. Based on our experiences of conducting several health-related case studies, we reflect on the different types of case study design, the specific research questions this approach can help answer, the data sources that tend to be used, and the particular advantages and disadvantages of employing this methodological approach. The paper concludes with key pointers to aid those designing and appraising proposals for conducting case study research, and a checklist to help readers assess the quality of case study reports.

Introduction

The case study approach is particularly useful to employ when there is a need to obtain an in-depth appreciation of an issue, event or phenomenon of interest, in its natural real-life context. Our aim in writing this piece is to provide insights into when to consider employing this approach and an overview of key methodological considerations in relation to the design, planning, analysis, interpretation and reporting of case studies.

The illustrative 'grand round', 'case report' and 'case series' have a long tradition in clinical practice and research. Presenting detailed critiques, typically of one or more patients, aims to provide insights into aspects of the clinical case and, in doing so, illustrate broader lessons that may be learnt. In research, the conceptually-related case study approach can be used, for example, to describe in detail a patient's episode of care, explore professional attitudes to and experiences of a new policy initiative or service development or more generally to 'investigate contemporary phenomena within its real-life context' [ 1 ]. Based on our experiences of conducting a range of case studies, we reflect on when to consider using this approach, discuss the key steps involved and illustrate, with examples, some of the practical challenges of attaining an in-depth understanding of a 'case' as an integrated whole. In keeping with previously published work, we acknowledge the importance of theory to underpin the design, selection, conduct and interpretation of case studies[ 2 ]. In so doing, we make passing reference to the different epistemological approaches used in case study research by key theoreticians and methodologists in this field of enquiry.

This paper is structured around the following main questions: What is a case study? What are case studies used for? How are case studies conducted? What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided? We draw in particular on four of our own recently published examples of case studies (see Tables Tables1, 1 , ,2, 2 , ,3 3 and and4) 4 ) and those of others to illustrate our discussion[ 3 - 7 ].

Example of a case study investigating the reasons for differences in recruitment rates of minority ethnic people in asthma research[ 3 ]

| Minority ethnic people experience considerably greater morbidity from asthma than the White majority population. Research has shown however that these minority ethnic populations are likely to be under-represented in research undertaken in the UK; there is comparatively less marginalisation in the US. |

| To investigate approaches to bolster recruitment of South Asians into UK asthma studies through qualitative research with US and UK researchers, and UK community leaders. |

| Single intrinsic case study |

| Centred on the issue of recruitment of South Asian people with asthma. |

| In-depth interviews were conducted with asthma researchers from the UK and US. A supplementary questionnaire was also provided to researchers. |

| Framework approach. |

| Barriers to ethnic minority recruitment were found to centre around: |

| 1. The attitudes of the researchers' towards inclusion: The majority of UK researchers interviewed were generally supportive of the idea of recruiting ethnically diverse participants but expressed major concerns about the practicalities of achieving this; in contrast, the US researchers appeared much more committed to the policy of inclusion. |

| 2. Stereotypes and prejudices: We found that some of the UK researchers' perceptions of ethnic minorities may have influenced their decisions on whether to approach individuals from particular ethnic groups. These stereotypes centred on issues to do with, amongst others, language barriers and lack of altruism. |

| 3. Demographic, political and socioeconomic contexts of the two countries: Researchers suggested that the demographic profile of ethnic minorities, their political engagement and the different configuration of the health services in the UK and the US may have contributed to differential rates. |

| 4. Above all, however, it appeared that the overriding importance of the US National Institute of Health's policy to mandate the inclusion of minority ethnic people (and women) had a major impact on shaping the attitudes and in turn the experiences of US researchers'; the absence of any similar mandate in the UK meant that UK-based researchers had not been forced to challenge their existing practices and they were hence unable to overcome any stereotypical/prejudicial attitudes through experiential learning. |

Example of a case study investigating the process of planning and implementing a service in Primary Care Organisations[ 4 ]

| Health work forces globally are needing to reorganise and reconfigure in order to meet the challenges posed by the increased numbers of people living with long-term conditions in an efficient and sustainable manner. Through studying the introduction of General Practitioners with a Special Interest in respiratory disorders, this study aimed to provide insights into this important issue by focusing on community respiratory service development. |

| To understand and compare the process of workforce change in respiratory services and the impact on patient experience (specifically in relation to the role of general practitioners with special interests) in a theoretically selected sample of Primary Care Organisations (PCOs), in order to derive models of good practice in planning and the implementation of a broad range of workforce issues. |

| Multiple-case design of respiratory services in health regions in England and Wales. |

| Four PCOs. |

| Face-to-face and telephone interviews, e-mail discussions, local documents, patient diaries, news items identified from local and national websites, national workshop. |

| Reading, coding and comparison progressed iteratively. |

| 1. In the screening phase of this study (which involved semi-structured telephone interviews with the person responsible for driving the reconfiguration of respiratory services in 30 PCOs), the barriers of financial deficit, organisational uncertainty, disengaged clinicians and contradictory policies proved insurmountable for many PCOs to developing sustainable services. A key rationale for PCO re-organisation in 2006 was to strengthen their commissioning function and those of clinicians through Practice-Based Commissioning. However, the turbulence, which surrounded reorganisation was found to have the opposite desired effect. |

| 2. Implementing workforce reconfiguration was strongly influenced by the negotiation and contest among local clinicians and managers about "ownership" of work and income. |

| 3. Despite the intention to make the commissioning system more transparent, personal relationships based on common professional interests, past work history, friendships and collegiality, remained as key drivers for sustainable innovation in service development. |

| It was only possible to undertake in-depth work in a selective number of PCOs and, even within these selected PCOs, it was not possible to interview all informants of potential interest and/or obtain all relevant documents. This work was conducted in the early stages of a major NHS reorganisation in England and Wales and thus, events are likely to have continued to evolve beyond the study period; we therefore cannot claim to have seen any of the stories through to their conclusion. |

Example of a case study investigating the introduction of the electronic health records[ 5 ]

| Healthcare systems globally are moving from paper-based record systems to electronic health record systems. In 2002, the NHS in England embarked on the most ambitious and expensive IT-based transformation in healthcare in history seeking to introduce electronic health records into all hospitals in England by 2010. |

| To describe and evaluate the implementation and adoption of detailed electronic health records in secondary care in England and thereby provide formative feedback for local and national rollout of the NHS Care Records Service. |

| A mixed methods, longitudinal, multi-site, socio-technical collective case study. |

| Five NHS acute hospital and mental health Trusts that have been the focus of early implementation efforts. |

| Semi-structured interviews, documentary data and field notes, observations and quantitative data. |

| Qualitative data were analysed thematically using a socio-technical coding matrix, combined with additional themes that emerged from the data. |

| 1. Hospital electronic health record systems have developed and been implemented far more slowly than was originally envisioned. |

| 2. The top-down, government-led standardised approach needed to evolve to admit more variation and greater local choice for hospitals in order to support local service delivery. |

| 3. A range of adverse consequences were associated with the centrally negotiated contracts, which excluded the hospitals in question. |

| 4. The unrealistic, politically driven, timeline (implementation over 10 years) was found to be a major source of frustration for developers, implementers and healthcare managers and professionals alike. |

| We were unable to access details of the contracts between government departments and the Local Service Providers responsible for delivering and implementing the software systems. This, in turn, made it difficult to develop a holistic understanding of some key issues impacting on the overall slow roll-out of the NHS Care Record Service. Early adopters may also have differed in important ways from NHS hospitals that planned to join the National Programme for Information Technology and implement the NHS Care Records Service at a later point in time. |

Example of a case study investigating the formal and informal ways students learn about patient safety[ 6 ]

| There is a need to reduce the disease burden associated with iatrogenic harm and considering that healthcare education represents perhaps the most sustained patient safety initiative ever undertaken, it is important to develop a better appreciation of the ways in which undergraduate and newly qualified professionals receive and make sense of the education they receive. | |

|---|---|

| To investigate the formal and informal ways pre-registration students from a range of healthcare professions (medicine, nursing, physiotherapy and pharmacy) learn about patient safety in order to become safe practitioners. | |

| Multi-site, mixed method collective case study. | |

| : Eight case studies (two for each professional group) were carried out in educational provider sites considering different programmes, practice environments and models of teaching and learning. | |

| Structured in phases relevant to the three knowledge contexts: | |

| Documentary evidence (including undergraduate curricula, handbooks and module outlines), complemented with a range of views (from course leads, tutors and students) and observations in a range of academic settings. | |

| Policy and management views of patient safety and influences on patient safety education and practice. NHS policies included, for example, implementation of the National Patient Safety Agency's , which encourages organisations to develop an organisational safety culture in which staff members feel comfortable identifying dangers and reporting hazards. | |

| The cultures to which students are exposed i.e. patient safety in relation to day-to-day working. NHS initiatives included, for example, a hand washing initiative or introduction of infection control measures. | |

| 1. Practical, informal, learning opportunities were valued by students. On the whole, however, students were not exposed to nor engaged with important NHS initiatives such as risk management activities and incident reporting schemes. | |

| 2. NHS policy appeared to have been taken seriously by course leaders. Patient safety materials were incorporated into both formal and informal curricula, albeit largely implicit rather than explicit. | |

| 3. Resource issues and peer pressure were found to influence safe practice. Variations were also found to exist in students' experiences and the quality of the supervision available. | |

| The curriculum and organisational documents collected differed between sites, which possibly reflected gatekeeper influences at each site. The recruitment of participants for focus group discussions proved difficult, so interviews or paired discussions were used as a substitute. | |

What is a case study?

A case study is a research approach that is used to generate an in-depth, multi-faceted understanding of a complex issue in its real-life context. It is an established research design that is used extensively in a wide variety of disciplines, particularly in the social sciences. A case study can be defined in a variety of ways (Table (Table5), 5 ), the central tenet being the need to explore an event or phenomenon in depth and in its natural context. It is for this reason sometimes referred to as a "naturalistic" design; this is in contrast to an "experimental" design (such as a randomised controlled trial) in which the investigator seeks to exert control over and manipulate the variable(s) of interest.

Definitions of a case study

| Author | Definition |

|---|---|

| Stake[ ] | (p.237) |

| Yin[ , , ] | (Yin 1999 p. 1211, Yin 1994 p. 13) |

| • | |

| • (Yin 2009 p18) | |

| Miles and Huberman[ ] | (p. 25) |

| Green and Thorogood[ ] | (p. 284) |

| George and Bennett[ ] | (p. 17)" |

Stake's work has been particularly influential in defining the case study approach to scientific enquiry. He has helpfully characterised three main types of case study: intrinsic , instrumental and collective [ 8 ]. An intrinsic case study is typically undertaken to learn about a unique phenomenon. The researcher should define the uniqueness of the phenomenon, which distinguishes it from all others. In contrast, the instrumental case study uses a particular case (some of which may be better than others) to gain a broader appreciation of an issue or phenomenon. The collective case study involves studying multiple cases simultaneously or sequentially in an attempt to generate a still broader appreciation of a particular issue.

These are however not necessarily mutually exclusive categories. In the first of our examples (Table (Table1), 1 ), we undertook an intrinsic case study to investigate the issue of recruitment of minority ethnic people into the specific context of asthma research studies, but it developed into a instrumental case study through seeking to understand the issue of recruitment of these marginalised populations more generally, generating a number of the findings that are potentially transferable to other disease contexts[ 3 ]. In contrast, the other three examples (see Tables Tables2, 2 , ,3 3 and and4) 4 ) employed collective case study designs to study the introduction of workforce reconfiguration in primary care, the implementation of electronic health records into hospitals, and to understand the ways in which healthcare students learn about patient safety considerations[ 4 - 6 ]. Although our study focusing on the introduction of General Practitioners with Specialist Interests (Table (Table2) 2 ) was explicitly collective in design (four contrasting primary care organisations were studied), is was also instrumental in that this particular professional group was studied as an exemplar of the more general phenomenon of workforce redesign[ 4 ].

What are case studies used for?

According to Yin, case studies can be used to explain, describe or explore events or phenomena in the everyday contexts in which they occur[ 1 ]. These can, for example, help to understand and explain causal links and pathways resulting from a new policy initiative or service development (see Tables Tables2 2 and and3, 3 , for example)[ 1 ]. In contrast to experimental designs, which seek to test a specific hypothesis through deliberately manipulating the environment (like, for example, in a randomised controlled trial giving a new drug to randomly selected individuals and then comparing outcomes with controls),[ 9 ] the case study approach lends itself well to capturing information on more explanatory ' how ', 'what' and ' why ' questions, such as ' how is the intervention being implemented and received on the ground?'. The case study approach can offer additional insights into what gaps exist in its delivery or why one implementation strategy might be chosen over another. This in turn can help develop or refine theory, as shown in our study of the teaching of patient safety in undergraduate curricula (Table (Table4 4 )[ 6 , 10 ]. Key questions to consider when selecting the most appropriate study design are whether it is desirable or indeed possible to undertake a formal experimental investigation in which individuals and/or organisations are allocated to an intervention or control arm? Or whether the wish is to obtain a more naturalistic understanding of an issue? The former is ideally studied using a controlled experimental design, whereas the latter is more appropriately studied using a case study design.

Case studies may be approached in different ways depending on the epistemological standpoint of the researcher, that is, whether they take a critical (questioning one's own and others' assumptions), interpretivist (trying to understand individual and shared social meanings) or positivist approach (orientating towards the criteria of natural sciences, such as focusing on generalisability considerations) (Table (Table6). 6 ). Whilst such a schema can be conceptually helpful, it may be appropriate to draw on more than one approach in any case study, particularly in the context of conducting health services research. Doolin has, for example, noted that in the context of undertaking interpretative case studies, researchers can usefully draw on a critical, reflective perspective which seeks to take into account the wider social and political environment that has shaped the case[ 11 ].

Example of epistemological approaches that may be used in case study research

| Approach | Characteristics | Criticisms | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Involves questioning one's own assumptions taking into account the wider political and social environment. | It can possibly neglect other factors by focussing only on power relationships and may give the researcher a position that is too privileged. | Howcroft and Trauth[ ] Blakie[ ] Doolin[ , ] | |

| Interprets the limiting conditions in relation to power and control that are thought to influence behaviour. | Bloomfield and Best[ ] | ||

| Involves understanding meanings/contexts and processes as perceived from different perspectives, trying to understand individual and shared social meanings. Focus is on theory building. | Often difficult to explain unintended consequences and for neglecting surrounding historical contexts | Stake[ ] Doolin[ ] | |

| Involves establishing which variables one wishes to study in advance and seeing whether they fit in with the findings. Focus is often on testing and refining theory on the basis of case study findings. | It does not take into account the role of the researcher in influencing findings. | Yin[ , , ] Shanks and Parr[ ] |

How are case studies conducted?

Here, we focus on the main stages of research activity when planning and undertaking a case study; the crucial stages are: defining the case; selecting the case(s); collecting and analysing the data; interpreting data; and reporting the findings.

Defining the case

Carefully formulated research question(s), informed by the existing literature and a prior appreciation of the theoretical issues and setting(s), are all important in appropriately and succinctly defining the case[ 8 , 12 ]. Crucially, each case should have a pre-defined boundary which clarifies the nature and time period covered by the case study (i.e. its scope, beginning and end), the relevant social group, organisation or geographical area of interest to the investigator, the types of evidence to be collected, and the priorities for data collection and analysis (see Table Table7 7 )[ 1 ]. A theory driven approach to defining the case may help generate knowledge that is potentially transferable to a range of clinical contexts and behaviours; using theory is also likely to result in a more informed appreciation of, for example, how and why interventions have succeeded or failed[ 13 ].

Example of a checklist for rating a case study proposal[ 8 ]

| Clarity: Does the proposal read well? | |

| Integrity: Do its pieces fit together? | |

| Attractiveness: Does it pique the reader's interest? | |

| The case: Is the case adequately defined? | |

| The issues: Are major research questions identified? | |

| Data Resource: Are sufficient data sources identified? | |

| Case Selection: Is the selection plan reasonable? | |

| Data Gathering: Are data-gathering activities outlined? | |

| Validation: Is the need and opportunity for triangulation indicated? | |

| Access: Are arrangements for start-up anticipated? | |

| Confidentiality: Is there sensitivity to the protection of people? | |

| Cost: Are time and resource estimates reasonable? |

For example, in our evaluation of the introduction of electronic health records in English hospitals (Table (Table3), 3 ), we defined our cases as the NHS Trusts that were receiving the new technology[ 5 ]. Our focus was on how the technology was being implemented. However, if the primary research interest had been on the social and organisational dimensions of implementation, we might have defined our case differently as a grouping of healthcare professionals (e.g. doctors and/or nurses). The precise beginning and end of the case may however prove difficult to define. Pursuing this same example, when does the process of implementation and adoption of an electronic health record system really begin or end? Such judgements will inevitably be influenced by a range of factors, including the research question, theory of interest, the scope and richness of the gathered data and the resources available to the research team.

Selecting the case(s)

The decision on how to select the case(s) to study is a very important one that merits some reflection. In an intrinsic case study, the case is selected on its own merits[ 8 ]. The case is selected not because it is representative of other cases, but because of its uniqueness, which is of genuine interest to the researchers. This was, for example, the case in our study of the recruitment of minority ethnic participants into asthma research (Table (Table1) 1 ) as our earlier work had demonstrated the marginalisation of minority ethnic people with asthma, despite evidence of disproportionate asthma morbidity[ 14 , 15 ]. In another example of an intrinsic case study, Hellstrom et al.[ 16 ] studied an elderly married couple living with dementia to explore how dementia had impacted on their understanding of home, their everyday life and their relationships.

For an instrumental case study, selecting a "typical" case can work well[ 8 ]. In contrast to the intrinsic case study, the particular case which is chosen is of less importance than selecting a case that allows the researcher to investigate an issue or phenomenon. For example, in order to gain an understanding of doctors' responses to health policy initiatives, Som undertook an instrumental case study interviewing clinicians who had a range of responsibilities for clinical governance in one NHS acute hospital trust[ 17 ]. Sampling a "deviant" or "atypical" case may however prove even more informative, potentially enabling the researcher to identify causal processes, generate hypotheses and develop theory.

In collective or multiple case studies, a number of cases are carefully selected. This offers the advantage of allowing comparisons to be made across several cases and/or replication. Choosing a "typical" case may enable the findings to be generalised to theory (i.e. analytical generalisation) or to test theory by replicating the findings in a second or even a third case (i.e. replication logic)[ 1 ]. Yin suggests two or three literal replications (i.e. predicting similar results) if the theory is straightforward and five or more if the theory is more subtle. However, critics might argue that selecting 'cases' in this way is insufficiently reflexive and ill-suited to the complexities of contemporary healthcare organisations.

The selected case study site(s) should allow the research team access to the group of individuals, the organisation, the processes or whatever else constitutes the chosen unit of analysis for the study. Access is therefore a central consideration; the researcher needs to come to know the case study site(s) well and to work cooperatively with them. Selected cases need to be not only interesting but also hospitable to the inquiry [ 8 ] if they are to be informative and answer the research question(s). Case study sites may also be pre-selected for the researcher, with decisions being influenced by key stakeholders. For example, our selection of case study sites in the evaluation of the implementation and adoption of electronic health record systems (see Table Table3) 3 ) was heavily influenced by NHS Connecting for Health, the government agency that was responsible for overseeing the National Programme for Information Technology (NPfIT)[ 5 ]. This prominent stakeholder had already selected the NHS sites (through a competitive bidding process) to be early adopters of the electronic health record systems and had negotiated contracts that detailed the deployment timelines.

It is also important to consider in advance the likely burden and risks associated with participation for those who (or the site(s) which) comprise the case study. Of particular importance is the obligation for the researcher to think through the ethical implications of the study (e.g. the risk of inadvertently breaching anonymity or confidentiality) and to ensure that potential participants/participating sites are provided with sufficient information to make an informed choice about joining the study. The outcome of providing this information might be that the emotive burden associated with participation, or the organisational disruption associated with supporting the fieldwork, is considered so high that the individuals or sites decide against participation.

In our example of evaluating implementations of electronic health record systems, given the restricted number of early adopter sites available to us, we sought purposively to select a diverse range of implementation cases among those that were available[ 5 ]. We chose a mixture of teaching, non-teaching and Foundation Trust hospitals, and examples of each of the three electronic health record systems procured centrally by the NPfIT. At one recruited site, it quickly became apparent that access was problematic because of competing demands on that organisation. Recognising the importance of full access and co-operative working for generating rich data, the research team decided not to pursue work at that site and instead to focus on other recruited sites.

Collecting the data

In order to develop a thorough understanding of the case, the case study approach usually involves the collection of multiple sources of evidence, using a range of quantitative (e.g. questionnaires, audits and analysis of routinely collected healthcare data) and more commonly qualitative techniques (e.g. interviews, focus groups and observations). The use of multiple sources of data (data triangulation) has been advocated as a way of increasing the internal validity of a study (i.e. the extent to which the method is appropriate to answer the research question)[ 8 , 18 - 21 ]. An underlying assumption is that data collected in different ways should lead to similar conclusions, and approaching the same issue from different angles can help develop a holistic picture of the phenomenon (Table (Table2 2 )[ 4 ].

Brazier and colleagues used a mixed-methods case study approach to investigate the impact of a cancer care programme[ 22 ]. Here, quantitative measures were collected with questionnaires before, and five months after, the start of the intervention which did not yield any statistically significant results. Qualitative interviews with patients however helped provide an insight into potentially beneficial process-related aspects of the programme, such as greater, perceived patient involvement in care. The authors reported how this case study approach provided a number of contextual factors likely to influence the effectiveness of the intervention and which were not likely to have been obtained from quantitative methods alone.

In collective or multiple case studies, data collection needs to be flexible enough to allow a detailed description of each individual case to be developed (e.g. the nature of different cancer care programmes), before considering the emerging similarities and differences in cross-case comparisons (e.g. to explore why one programme is more effective than another). It is important that data sources from different cases are, where possible, broadly comparable for this purpose even though they may vary in nature and depth.

Analysing, interpreting and reporting case studies

Making sense and offering a coherent interpretation of the typically disparate sources of data (whether qualitative alone or together with quantitative) is far from straightforward. Repeated reviewing and sorting of the voluminous and detail-rich data are integral to the process of analysis. In collective case studies, it is helpful to analyse data relating to the individual component cases first, before making comparisons across cases. Attention needs to be paid to variations within each case and, where relevant, the relationship between different causes, effects and outcomes[ 23 ]. Data will need to be organised and coded to allow the key issues, both derived from the literature and emerging from the dataset, to be easily retrieved at a later stage. An initial coding frame can help capture these issues and can be applied systematically to the whole dataset with the aid of a qualitative data analysis software package.

The Framework approach is a practical approach, comprising of five stages (familiarisation; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; charting; mapping and interpretation) , to managing and analysing large datasets particularly if time is limited, as was the case in our study of recruitment of South Asians into asthma research (Table (Table1 1 )[ 3 , 24 ]. Theoretical frameworks may also play an important role in integrating different sources of data and examining emerging themes. For example, we drew on a socio-technical framework to help explain the connections between different elements - technology; people; and the organisational settings within which they worked - in our study of the introduction of electronic health record systems (Table (Table3 3 )[ 5 ]. Our study of patient safety in undergraduate curricula drew on an evaluation-based approach to design and analysis, which emphasised the importance of the academic, organisational and practice contexts through which students learn (Table (Table4 4 )[ 6 ].

Case study findings can have implications both for theory development and theory testing. They may establish, strengthen or weaken historical explanations of a case and, in certain circumstances, allow theoretical (as opposed to statistical) generalisation beyond the particular cases studied[ 12 ]. These theoretical lenses should not, however, constitute a strait-jacket and the cases should not be "forced to fit" the particular theoretical framework that is being employed.

When reporting findings, it is important to provide the reader with enough contextual information to understand the processes that were followed and how the conclusions were reached. In a collective case study, researchers may choose to present the findings from individual cases separately before amalgamating across cases. Care must be taken to ensure the anonymity of both case sites and individual participants (if agreed in advance) by allocating appropriate codes or withholding descriptors. In the example given in Table Table3, 3 , we decided against providing detailed information on the NHS sites and individual participants in order to avoid the risk of inadvertent disclosure of identities[ 5 , 25 ].

What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided?

The case study approach is, as with all research, not without its limitations. When investigating the formal and informal ways undergraduate students learn about patient safety (Table (Table4), 4 ), for example, we rapidly accumulated a large quantity of data. The volume of data, together with the time restrictions in place, impacted on the depth of analysis that was possible within the available resources. This highlights a more general point of the importance of avoiding the temptation to collect as much data as possible; adequate time also needs to be set aside for data analysis and interpretation of what are often highly complex datasets.

Case study research has sometimes been criticised for lacking scientific rigour and providing little basis for generalisation (i.e. producing findings that may be transferable to other settings)[ 1 ]. There are several ways to address these concerns, including: the use of theoretical sampling (i.e. drawing on a particular conceptual framework); respondent validation (i.e. participants checking emerging findings and the researcher's interpretation, and providing an opinion as to whether they feel these are accurate); and transparency throughout the research process (see Table Table8 8 )[ 8 , 18 - 21 , 23 , 26 ]. Transparency can be achieved by describing in detail the steps involved in case selection, data collection, the reasons for the particular methods chosen, and the researcher's background and level of involvement (i.e. being explicit about how the researcher has influenced data collection and interpretation). Seeking potential, alternative explanations, and being explicit about how interpretations and conclusions were reached, help readers to judge the trustworthiness of the case study report. Stake provides a critique checklist for a case study report (Table (Table9 9 )[ 8 ].

Potential pitfalls and mitigating actions when undertaking case study research

| Potential pitfall | Mitigating action |

|---|---|

| Selecting/conceptualising the wrong case(s) resulting in lack of theoretical generalisations | Developing in-depth knowledge of theoretical and empirical literature, justifying choices made |

| Collecting large volumes of data that are not relevant to the case or too little to be of any value | Focus data collection in line with research questions, whilst being flexible and allowing different paths to be explored |

| Defining/bounding the case | Focus on related components (either by time and/or space), be clear what is outside the scope of the case |

| Lack of rigour | Triangulation, respondent validation, the use of theoretical sampling, transparency throughout the research process |

| Ethical issues | Anonymise appropriately as cases are often easily identifiable to insiders, informed consent of participants |

| Integration with theoretical framework | Allow for unexpected issues to emerge and do not force fit, test out preliminary explanations, be clear about epistemological positions in advance |

Stake's checklist for assessing the quality of a case study report[ 8 ]

| 1. Is this report easy to read? |

| 2. Does it fit together, each sentence contributing to the whole? |

| 3. Does this report have a conceptual structure (i.e. themes or issues)? |

| 4. Are its issues developed in a series and scholarly way? |

| 5. Is the case adequately defined? |

| 6. Is there a sense of story to the presentation? |

| 7. Is the reader provided some vicarious experience? |

| 8. Have quotations been used effectively? |

| 9. Are headings, figures, artefacts, appendices, indexes effectively used? |

| 10. Was it edited well, then again with a last minute polish? |

| 11. Has the writer made sound assertions, neither over- or under-interpreting? |

| 12. Has adequate attention been paid to various contexts? |

| 13. Were sufficient raw data presented? |

| 14. Were data sources well chosen and in sufficient number? |

| 15. Do observations and interpretations appear to have been triangulated? |

| 16. Is the role and point of view of the researcher nicely apparent? |

| 17. Is the nature of the intended audience apparent? |

| 18. Is empathy shown for all sides? |

| 19. Are personal intentions examined? |

| 20. Does it appear individuals were put at risk? |

Conclusions

The case study approach allows, amongst other things, critical events, interventions, policy developments and programme-based service reforms to be studied in detail in a real-life context. It should therefore be considered when an experimental design is either inappropriate to answer the research questions posed or impossible to undertake. Considering the frequency with which implementations of innovations are now taking place in healthcare settings and how well the case study approach lends itself to in-depth, complex health service research, we believe this approach should be more widely considered by researchers. Though inherently challenging, the research case study can, if carefully conceptualised and thoughtfully undertaken and reported, yield powerful insights into many important aspects of health and healthcare delivery.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AS conceived this article. SC, KC and AR wrote this paper with GH, AA and AS all commenting on various drafts. SC and AS are guarantors.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/11/100/prepub

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants and colleagues who contributed to the individual case studies that we have drawn on. This work received no direct funding, but it has been informed by projects funded by Asthma UK, the NHS Service Delivery Organisation, NHS Connecting for Health Evaluation Programme, and Patient Safety Research Portfolio. We would also like to thank the expert reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback. Our thanks are also due to Dr. Allison Worth who commented on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

- Yin RK. Case study research, design and method. 4. London: Sage Publications Ltd.; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keen J, Packwood T. Qualitative research; case study evaluation. BMJ. 1995; 311 :444–446. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sheikh A, Halani L, Bhopal R, Netuveli G, Partridge M, Car J. et al. Facilitating the Recruitment of Minority Ethnic People into Research: Qualitative Case Study of South Asians and Asthma. PLoS Med. 2009; 6 (10):1–11. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]