- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How the US Government Used Propaganda to Sell Americans on World War I

By: Patricia O'Toole

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: May 22, 2018

When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson faced a reluctant nation. Wilson had, after all, won his reelection in 1916 with the slogan, “He kept us out of the war.” To convince Americans that going to war in Europe was necessary, Wilson created the Committee on Public Information (CPI), to focus on promoting the war effort.

To head up the committee, Wilson appointed a brilliant political public relations man, George Creel. As head of the CPI, Creel was in charge of censorship as well as flag-waving, but he quickly passed the censor’s job to Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson. The Post Office already had the power to bar materials from the mail and revoke the reduced postage rates given to newspapers and magazines.

Creel dispatches positive news to stir a ‘war-will’ among Americans

Handsome, charismatic, and indefatigable, Creel thought big and out of the box. He disliked the word “propaganda,” which he associated with Germany’s long campaign of disinformation. To him, the CPI’s business was more like advertising, “a vast enterprise in salesmanship” that emphasized the positive. A veteran of Wilson’s two successful presidential campaigns, Creel knew how to organize an army of volunteers, and 150,000 men and women answered his call. The Washington office, which operated on a shoestring, was part government communications bureau and part media conglomerate, with divisions for news, syndicated features, advertising, film, and more. At Wilson’s insistence, the CPI also published the Official Bulletin , the executive-branch equivalent of the Congressional Record.

Creel’s first idea was to distribute good news and disclose as many facts about the war as he could without compromising national security. His M.O. was simple: flood the country with press releases disguised as news stories. Summing up after the war, Creel said he aimed to “weld the people of the United States into one white-hot mass instinct” and give them a “war-will, the will to win.”

HISTORY Vault: World War I Documentaries

Stream World War I videos commercial-free in HISTORY Vault.

During the 20 months of the U.S. involvement in the war, the CPI issued nearly all government announcements and sent out 6,000 press releases written in the straightforward, understated tone of newspaper articles. It also designed and circulated more than 1,500 patriotic advertisements. In addition, Creel distributed uncounted articles by famous authors who had agreed to write for free. At one point, newspapers were receiving six pounds of CPI material a day. Editors eager to avoid trouble with the Post Office and the Justice Department published reams of CPI material verbatim and often ran the patriotic ads for free.

Propaganda describes the enemy as ‘mad brute’

For the first two months, nearly all of the information generated by the CPI consisted of announcements and propaganda of the cheerleading variety: salutes to America’s wartime achievements and American ideals. At Creel’s direction, the CPI celebrated America’s immigrants and fought the perception that those who hailed from Germany, Austria, and Hungary were less American than their neighbors. Creel thought it savvier to try to befriend large ethnic groups than to attack them.

But after two months, Creel and Wilson could see that popular enthusiasm for the war was nowhere near white-hot. So on June 14, 1917, Wilson used the occasion of Flag Day to paint a picture of American soldiers about to carry the Stars and Stripes into battle and die on fields soaked in blood. And for what? he asked. In calling for a declaration of war, he had argued that the world must be made safe for democracy, but with his 1917 Flag Day speech, he trained the country’s sights on a less exalted goal: the destruction of the government of Germany, which was bent on world domination.

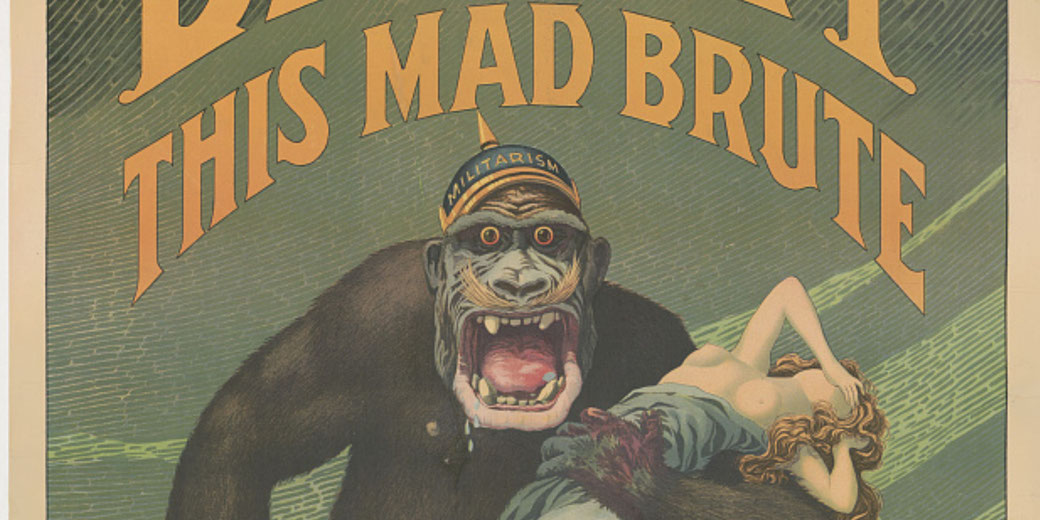

After Flag Day , the CPI continued to churn out positive news by the ton, but it also began plastering the country with lurid posters of ape-like German soldiers, some with bloody bayonets, others with bare-breasted young females in their clutches. “Destroy this mad brute,” read one caption. It also funded films with titles like The Kaiser: The Beast of Berlin and The Prussian Curse .

Vigilantes inflict terror on suspected skeptics of the war

The CPI’s happy news sometimes downplayed the shortcomings of the U.S. war effort, but the demonizing of all Germans played to low instincts. Thousands of self-appointed guardians of patriotism began to harass pacifists, socialists, and German immigrants who were not citizens. And many Americans took CPI’s dark warnings to heart.

Even the most casual expression of doubt about the war could trigger a beating by a mob and the humiliation of being made to kiss the flag in public. Americans who declined to buy Liberty Bonds (issued by the Treasury to finance the war) sometimes awoke to find their homes streaked with yellow paint. Several churches of pacifist sects were set ablaze. Scores of men suspected of disloyalty were tarred and feathered, and a handful were lynched. Most of the violence was carried out in the dark by vigilantes who marched their victims to a spot outside the city limits, where the local police had no jurisdiction. Perpetrators who were apprehended were rarely tried, and those tried were almost never found guilty. Jurors hesitated to convict, afraid that they too would be accused of disloyalty and roughed up.

Both Creel and Wilson privately deplored the vigilantes, but neither acknowledged his role in turning them loose. Less violent but no less regrettable were the actions taken by state and local governments and countless private institutions to fire German aliens, suspend performances of German music, and ban the teaching of German in schools.

In their effort to unify the country, Wilson and Creel deployed their own versions of fake news. While the worst that can be said of the sunny fake news flowing out of the CPI was that it was incomplete, the dark fake news, which painted the enemy as subhuman, let loose a riptide of hatred and emboldened thousands to use patriotism as an excuse for violence.

Patricia O’Toole is the author of five books, including The Moralist: Woodrow Wilson and the World He Made and The Five of Hearts: An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and His Friends , which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Manipulating the masses: How propaganda was used during World War I

World War I was a conflict that not only consumed the lives of the soldiers in the trenches and battlefields, but also had a powerful impact on the hearts and minds of millions at home.

This was done through the strategic use of propaganda. The proactive manipulation of people's attitudes through the media played a surprisingly pivotal role in shaping public opinion and mobilizing resources.

But how exactly was propaganda used during World War I?

What were the different types of propaganda employed by the warring nations?

And how did it influence society's perception of the war?

What is 'propaganda'?

The term 'propaganda' often carries negative connotations, associated with manipulation and deceit.

However, its roots are far more neutral, derived from the Latin 'propagare', meaning 'to spread or propagate'.

In essence, propaganda is about disseminating information, ideas, or rumors for the purpose of helping or injuring an institution, a cause, or a person.

It has always been a powerful tool of persuasion, with the capability of molding public opinion and directing collective action.

Propaganda, as a concept, is as old as human civilization itself: from the ancient Egyptians who used it to glorify their pharaohs, to the Romans who utilized it to control public opinion.

However, it was during World War I that propaganda was used on an industrial scale.

It leveraged the advancements in mass communication technologies such as the printing press, radio, and cinema.

Governments quickly realized that to sustain a war on a global scale, they needed not just the physical resources but also the psychological backing of their citizens.

How countries used propaganda

Each nation involved in the war had its unique propaganda strategies; h owever, there were common themes and techniques that transcended national boundaries.

Firstly, and most obviously, propaganda was used to justify the war, usually to portray it as a noble and necessary endeavor.

At the same time, it was used to demonize the enemy. To do this, it would paint them as a threat not just to the nation but to civilization itself.

In a much more benign way, it was also used to mobilize resources by encouraging men to enlist or for civilians to buy war bonds.

The British, for example, established the War Propaganda Bureau early in the war which enlisted famous writers and artists to create compelling propaganda materials.

These were distributed both at home and abroad.

The Germans, on the other hand, relied heavily on propaganda to maintain morale during the British naval blockade.

These blockades had prevented shipping from reaching German ports, which caused severe food shortages in Germany.

In comparison, in the United States, which entered the war later , the Committee on Public Information, which was established by President Woodrow Wilson, launched a massive propaganda campaign to build support for the war effort.

Interestingly, this campaign was not just aimed at adults but also at children, with propaganda materials distributed in schools to instill a sense of patriotism and duty from a young age.

In Russia, propaganda was used to try and maintain support for the war amidst growing social unrest, which eventually led to the Russian Revolution .

The Russian government used propaganda to portray the war as a fight against German imperialism.

This was aimed at appealing to the nationalist sentiments of the Russian people, but it had little effect in the end.

Common types of WWI propaganda

During World War I, propaganda was employed in a variety of forms, each designed to serve a specific purpose.

The types of propaganda used can be broadly categorized into recruitment propaganda, war bond propaganda, enemy demonization propaganda, and nationalism and patriotism propaganda.

Recruitment propaganda

One of the most visible forms of propaganda during the war was recruitment propaganda.

As the war dragged on and casualty numbers rose, it became increasingly important for nations to encourage more men to enlist.

Recruitment posters often depicted the ideal soldier as brave, honorable, and patriotic, appealing to a sense of duty and masculinity.

Iconic images such as Lord Kitchener's "Your Country Needs You" poster in Britain, or Uncle Sam's "I Want You" poster in the United States, became powerful symbols of the call to arms.

War bonds propaganda

Another crucial aspect of propaganda was the promotion of war bonds. Financing the war was a massive undertaking.

So, governments turned to their citizens for help.

War bond propaganda aimed to convince the public that purchasing bonds was both a financial investment and a patriotic duty.

These campaigns often used emotional appeals. It suggested that buying bonds was a way to support the troops and contribute to the war effort.

Enemy demonisation propaganda

The demonization of the enemy was a common theme in World War I propaganda.

By portraying the enemy as monstrous, barbaric, or inhuman, governments could justify the war and stoke a sense of fear and hatred.

This type of propaganda was often based on stereotypes or outright lies, such as the infamous "Rape of Belgium" campaign by the Allies, which exaggerated German atrocities to gain international support.

Nationalisation and patriotism propaganda

Finally, propaganda was also used to foster a sense of nationalism and patriotism.

This was especially important in multi-ethnic empires like Austria-Hungary or the Ottoman Empire, where loyalty to the state was not a given.

The resultant nationalistic propaganda often used symbols, myths, and historical narratives to create a sense of shared identity and purpose.

The impact on society

One of the most significant impacts of propaganda was its role in creating a culture of sacrifice and service, where everyone was expected to do their part for the war effort.

Furthermore, propaganda influenced the way the war was understood and remembered.

It created a narrative of the war that highlighted the heroism and sacrifice of the soldiers, while downplaying the horror and destruction.

This narrative was often uncritically accepted, leading to a romanticized and distorted view of the war.

Ultimately, the use of propaganda during World War I may have had a significant impact on society by introducing new methods of mass communication and persuasion.

The techniques developed during the war, from the use of posters and films to the manipulation of news and information, became a standard part of political and commercial communication in the decades that followed.

The crucial role of artists and designers

Artists and designers' skills were harnessed to create powerful images and messages.

They were, in essence, visual storytellers, crafting narratives of heroism, sacrifice, and patriotism that resonated with the masses.

A well-designed poster or illustration could convey a message instantly and emotionally.

As a result, artists and designers used a variety of techniques to maximize the impact of their work: from the use of bold colors and simple, striking designs to the manipulation of symbols and stereotypes.

There are a number of very famous examples form various countries. In Britain, o ne of the most famous examples is the "Your Country Needs You" poster, featuring Lord Kitchener.

The poster, designed by Alfred Leete, became an iconic symbol of the call to arms.

Its simple yet powerful design resonating with the British public.

In Germany, artists like Ludwig Hohlwein and Lucian Bernhard created striking posters that promoted war bonds and recruitment.

Their work, characterized by bold typography and dramatic imagery, was instrumental in maintaining morale and unity during the war.

Then, in the United States, artists like James Montgomery Flagg and Howard Chandler Christy created memorable propaganda posters.

Flagg's "I Want You" poster, featuring Uncle Sam, became one of the most iconic images of the war, while Christy's posters, featuring idealized images of women, appealed to a sense of chivalry and duty.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

- Teaching Resources

- Upcoming Events

- On-demand Events

The Impact of Nazi Propaganda: Visual Essay

- facebook sharing

- email sharing

At a Glance

- The Holocaust

Propaganda was one of the most important tools the Nazis used to shape the beliefs and attitudes of the German public. Through posters, film, radio, museum exhibits, and other media, they bombarded the German public with messages designed to build support for and gain acceptance of their vision for the future of Germany. The gallery of images below exhibits several examples of Nazi propaganda, and the introduction that follows explores the history of propaganda and how the Nazis sought to use it to further their goals.

Examples of Nazi Propaganda

Nazi national welfare program.

This 1934 propaganda poster in support of the national welfare program reads: “National health, national community, child protection, protection of mothers, care for travelers, are the tasks of the NS-Welfare Service. Join now!”

Nazi Recruitment Propaganda

This mid-1930s poster says, “The NSDAP [Nazi Party] protects the people. Your fellow comrades need your advice and help, so join the local party organization.

Hitler Youth Propaganda

This 1935 poster promotes the Hitler Youth by stating: “Youth serves the Führer! All ten-year-olds into the Hitler Youth.”

Nazi Propaganda Newspaper

An issue of the antisemitic propaganda newspaper Der Stürmer (The Attacker) is posted on the sidewalk in Worms, Germany, in 1935. The headline above the case says, "The Jews Are Our Misfortune."

Triumph of the Will Propaganda Film

Leni Riefenstahl's documentary-style film glorified Hitler and the Nazi Party. It was shot at the 1934 Nazi Party congress and rally in Nuremberg.

Propaganda Portrait of Hitler

This portrait, The Standard Bearer , was painted by artist Hubert Lanzinger and displayed in the Great German Art Exhibition in Munich in 1937.

The Eternal Jew

This 1938 poster advertises a popular antisemitic traveling exhibit called Der Ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew).

Antisemitic Display at Der Ewige Jude

Women examining a display at the Der Ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew) exhibition in the Reichstag building in November 1938.

Antisemitic Children's Book

From the 1938 antisemitic children’s book The Poisonous Mushroom . The boy is drawing a nose on the chalkboard, and the caption reads: “The Jewish nose is crooked at its tip. It looks like a 6.”

The Definition and History of Propaganda

Propaganda is information that is intended to persuade an audience to accept a particular idea or cause, often by using biased material or by stirring up emotions. This was one of the most powerful tools the Nazis used to consolidate their power and create a German “national community” in the mid-1930s.

Hitler and Goebbels did not invent propaganda. The word itself was coined by the Catholic Church to describe its efforts to discredit Protestant teachings in the 1600s. Over the years, almost every nation has used propaganda to unite its people in wartime. Both sides spread propaganda during World War I, for example.

How the Nazis Used Propaganda

The Nazis were notable for making propaganda a key element of government even before Germany went to war again. One of Hitler’s first acts as chancellor was to establish the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, demonstrating his belief that controlling information was as important as controlling the military and the economy. He appointed Joseph Goebbels as director. Through the ministry, Goebbels was able to penetrate virtually every form of German media, from newspapers, film, radio, posters, and rallies to museum exhibits and school textbooks, with Nazi propaganda.

Whether or not propaganda was truthful or tasteful was irrelevant to the Nazis. Goebbels wrote in his diary, "no one can say your propaganda is too rough, too mean; these are not criteria by which it may be characterized. It ought not be decent nor ought it be gentle or soft or humble; it ought to lead to success." 1 Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf that to achieve its purpose, propaganda must "be limited to a very few points and must harp on these in slogans until the last member of the public understands what you want him to understand by your slogan. As soon as you sacrifice this slogan and try to be many-sided, the effect will piddle away."

Some Nazi propaganda used positive images to glorify the government’s leaders and its various activities, projecting a glowing vision of the “national community.” Nazi propaganda could also be ugly and negative, creating fear and loathing by portraying the regime’s “enemies” as dangerous and even sub-human. The Nazis’ distribution of antisemitic films, newspaper cartoons, and even children’s books aroused centuries-old prejudices against Jews and also presented new ideas about the racial impurity of Jews. The newspaper Der Stürmer (The Attacker), published by Nazi Party member Julius Streicher, was a key outlet for antisemitic propaganda.

This visual essay includes a selection of Nazi propaganda images, both “positive” and “negative.” It focuses on posters that Germans would have seen in newspapers like Der Stürmer and passed in the streets, in workplaces, and in schools. Some of these posters were advertisements for traveling exhibits—on topics like “The Eternal Jew” or the evils of communism—that were themselves examples of propaganda.

Connection Questions

- As you explore the images in this visual essay, consider what each image is trying to communicate to the viewer. Who is the audience for this message? How is the message conveyed?

- Do you notice any themes or patterns in this group of propaganda images? How do the ideas in these images connect to what you have already learned about Nazi ideology? How do they extend your thinking about Nazi ideas?

- Based on the images you analyze, how do you think the Nazis used propaganda to define the identities of individuals and groups? What groups and individuals did Nazi propaganda glorify? What stereotypes did it promote?

- Why was propaganda so important to Nazi leadership? How do you think Nazi propaganda influenced the attitudes and actions of Germans in the 1930s?

- Some scholars caution that there are limits to the power of propaganda; they think it succeeds not because it persuades the public to believe an entirely new set of ideas but because it expresses beliefs people already hold. Scholar Daniel Goldhagen writes: “No man, [no] Hitler, no matter how powerful he is, can move people against their hopes and desires. Hitler, as powerful a figure as he was, as charismatic as he was, could never have accomplished this [the Holocaust] had there not been tens of thousands, indeed hundreds of thousands of ordinary Germans who were willing to help him.” 2 Do you agree? Would people have rejected Nazi propaganda if they did not already share, to some extent, the beliefs it communicated?

- Can you think of examples of propaganda in society today? How do you think this propaganda influences the attitudes and actions of people today? Is there a difference between the impact of propaganda in a democracy that has a free press and an open marketplace of ideas and the impact of propaganda in a dictatorship with fewer non-governmental sources of information?

- 1 Quoted in Joachim C. Fest, The Face of the Third Reich: Portraits of the Nazi Leadership (New York: Da Capo Press, 1999), 90.

- 2 Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, interview with Richard Heffner, “Hitler’s Willing Executioners, Part I,” The Open Mind (TV program), PBS, July 9, 1996.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, " Visual Essay: The Impact of Propaganda ," last updated August 2, 2016.

You might also be interested in…

The power of propaganda, analyzing nazi propaganda, discussing contemporary islamophobia in the classroom, confronting islamophobia, exploring islamophobic tropes, addressing islamophobia in the media, understanding gendered islamophobia, standing up against contemporary islamophobia, antisemitic conflation: what is the impact of conflating all jews with the actions and policies of the israeli government, influence, celebrity, and the dangers of online hate, where do we get our news and why does it matter, creating healthy news habits, inspiration, insights, & ways to get involved.

Top of page

Analyzing Propaganda’s Role in World War I

May 10, 2018

Posted by: Cheryl Lederle

Share this post:

This post is by Matthew Poth, 2017-18 Library of Congress Teacher in Residence. For more WWI resources, download the Teaching World War I with Primary Sources Idea Book for Educators from HISTORY.

Are you tired of the same routine, day in and day out? Sick of tilling the fields or sweating in the factories? Join the United States Marine Corps!…but expect to be shipped to France to fight in the trenches.

The use of military recruitment posters and other forms of propaganda may be nothing new to students today; they see ads and pop-ups on social media and elsewhere. At the start of World War I, however, posters offered a powerful tool to reach and influence citizens of every social, educational, and racial background. Propaganda posters sought to rally the fighting spirit on the home front, raise money for war bonds, and create a sense of togetherness across a vast and diverse nation. Artists crafted posters to reach people on multiple levels, often in subconscious ways, to compel them to action by challenging any resistance as unpatriotic and even sympathetic to the enemy.

Start a class about World War I with Fred Spear’s Enlist poster. Give students a couple of minutes to observe the image and create a list of their reactions to details in the poster. Some might be drawn to what the woman is wearing or notice that she is holding a baby close to her. Invite students to share what they think is happening in this image (or has just happened). Distribute the bibliographic information only after several students have shared their thoughts. After students learn that the poster was created in response to the sinking of the Lusitania (1915), allow them to revise their interpretation of the poster and to write a short paragraph interpreting the poster and the techniques the artist used to elicit a reaction.

Introduce Harry Hopps’ Destroy this mad brute (1917) poster and allow time for students to list their reactions. Comparing it to Enlist , students might identify that the message of each poster is the same: enlist. However, the approach and the methods of encouraging enlistment are vastly different.

|

|

|

As students become comfortable with evaluating propaganda posters, consider asking them to select a poster or two from the Library of Congress online collections for close analysis and to better understand the evolving public opinion of American involvement throughout the war. Students could identify the message, the target audience, any subtext, and how the artist is trying to convince the audience to accept the message. To learn more about the prevalence of posters in society at the time of WWI, and the iconic WWI poster featuring Uncle Sam created by illustrator James Montgomery Flagg, students might watch this video by Library of Congress Curator Katherine Blood , featured in the Teaching World War I with Primary Sources Idea Book for Educators from HISTORY.

How do you support students when they analyze propaganda?

Do you enjoy these posts? Subscribe ! You’ll receive free teaching ideas and primary sources from the Library of Congress.

Comments (2)

This is a lesson that is particularly important in today’s political climate.

I am beginning to develop a lesson with an eye toward gender equality and the pre-existing gender stereotypes. The portrayal of women within the war propaganda is a nice magnifying glass into the commonly accepted role men they believe they have as protectors of purity of the women.

See All Comments

Add a Comment Cancel reply

This blog is governed by the general rules of respectful civil discourse. You are fully responsible for everything that you post. The content of all comments is released into the public domain unless clearly stated otherwise. The Library of Congress does not control the content posted. Nevertheless, the Library of Congress may monitor any user-generated content as it chooses and reserves the right to remove content for any reason whatever, without consent. Gratuitous links to sites are viewed as spam and may result in removed comments. We further reserve the right, in our sole discretion, to remove a user's privilege to post content on the Library site. Read our Comment and Posting Policy .

Required fields are indicated with an * asterisk.

My Accounts

- My Library Account View/renew books, media, and equipment

- ILL Account (ILLiad) Interlibrary loan requests

- Special Collections Research Account (Aeon) Archives and Special Collections requests

War of Words: Propaganda of World War I

World War I (1914-1918) was different than any previous war. It was a total war that required all members of the nation to be involved in the war effort. All of the resources of the state were mobilized for war. Ultimately, 65,000,000 soldiers from 30 countries fought in World War I and tens of millions citizens across the world would be involved in the conflict one way or another.

Between 1914 and 1918, war propaganda was virtually unavoidable. It came in many different forms, including posters, pamphlets and leaflets, magazine articles and advertisements, short films and speeches, and door-to-door campaigning. Print propaganda blanketed the nation, in both rural and urban areas, covering walls, windows, taxis and kiosks. In Britain, for example, the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee published and distributed almost 12 million copies of 140 different posters, 34 million leaflets, and 5.5 million pamphlets by the second year of the war. By the time of the armistice in November 1918, the American government had produced more than 20 million copies of some 2,500 distinct poster designs.

Propaganda often incorporated national symbols and figures that drew on each nation’s history of and mythology. Propaganda also employed depictions of the enemy to scare citizens into action and strengthen national resolve. These images were also used to justify the war, recruit men to fight, and raise war loans. A successful poster allowed for only one interpretation.

One of many purposes of propaganda was recruiting men for military service. Great Britain and the United States used propaganda to raise troops, often appealing to men’s notions of courage and duty. Recruitment propaganda also reinforced traditional gender roles, reminding men that it was their job to protect the women and children. However, once the draft was implemented in these nations, propaganda focused on other causes, such as boosting morale among soldiers and civilians.

However, for most nations involved in the fighting, this was not necessary as they already had universal conscription. Rather these countries, like France and Germany, used their propaganda to appeal to other nations to join their cause and to boost morale.

- Special Collections News

- Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library

- Skip to Guides Search

- Skip to breadcrumb

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

- Skip to chat link

- Report accessibility issues and get help

- Go to Penn Libraries Home

- Go to Franklin catalog

WWI Primary and Secondary Sources: Print and Online: Primary Sources

- Primary Sources

- Primary Sources continued

- Personal Narratives, Speeches, Papers

- Databases and Secondary Sources

- Research terms for Searching in Franklin Catalog and other Databases

Penn's World War I Digital Collections

- Penn's World War I Pamphlet Collection Penn has digitized over 400 pamphlets from its print collections dating from and relating to World War I. These pamphlets are now findable in Franklin via the series title: World War I Pamphlet Collection with live links to the facsimiles available through Hathi Trust and to Penn's Print at Penn. Access all pamphlets via the libraries Franklin catalog whether from Print at Penn or the Hathi Trust.

Connect to pamphlets via the Hathi Trust Digital Library

Connect to pamphlets via Print at Penn .

- Penn Libraries World War I Printed Media and Art Collection This collections contains over one thousand prints, propaganda posters, postcards, trench newspapers, maps, broadsides and original artworks dating from 1914 to 1931 and offers an enormous range of perspectives on the First World War.

First World War Primary Source Databases

Map From " The First World War " database collections

- The First World War This First World War portal includes primary source materials for the study of the Great War, complemented by a range of secondary features. The collection is divided into three modules: Personal Experiences, Propaganda and Recruitment, and Visual Perspectives and Narratives.

- Women, War and Society, 1914-1918 The First World War had a revolutionary and permanent impact on the personal, social and professional lives of all women. Their essential contribution to the war in Europe is fully documented in this definitive collection of primary source materials from the Imperial War Museum, London. Documents include charity and international relief reports, pamphlets, photographs, press cuttings, magazines, posters, correspondence, minutes, records, diaries, memoranda, statistics, circulars, regulations and invitation, all fully-searchable with interpretative essays from leading scholars.

- World War I and Revolution in Russia This collection documents the Russian entrance into World War I and culminates in reporting on the Revolution in Russia in 1917 and 1918. The documents consist primarily of correspondence between the British Foreign Office, various British missions and consulates in the Russian Empire and the Tsarist government and later the Provisional Government.

- Archives Unbound Browse "categories" or conduct keyword searches to find other primary source collections relevant to WW I. Interface can be very slow and might not work if you are using Firefox off campus.

- Prisoners of the First World War: ICRC Historical Archives 5 Million index cards with prisoner of war data provided by the countries at war. As of September 2014, 90% of the card have been loaded. Arrangement is by nationality rather than alphabetical by prisoner.

- World War I Document Archive This archive of primary documents from World War One has been assembled by volunteers of the World War I Military History List (WWI-L). International in focus, the archive intends to present in one location primary documents concerning the Great War.

- Times Digital Archive The Times of London 1785-2008. See a separate link for the Sunday Times

- Sunday Times Digital Archive The Sunday Times of London, 1855-2006

- New York Times Historical 1851-2010 A different perspective on world events

- German History in Documents and Images A comprehensive collection of primary source materials each of which documents Germany's political, social, and cultural history from 1500 to the present. It comprises original German texts, all of which are accompanied by new English translations, and a wide range of visual imagery. Use the timeline to select the time period 1890-1918.

- HathiTrust Digital Library Hathitrust.org brings together digitized public domain resources from libraries across the country. This is a good source for finding pamphlets, journals, magazines, and publications from the time before, during, and after the war.

Correspondence from the British Foreign Office

From World War I and the Revolution in Russia, 1914-1918"

World War I Posters

- Summons to Comradeship: World War I and World War II Posters This link takes you to Artstor and nearly 6,000 images for posters at the University of Minnesota. May require Pennkey sign in.

- World War I Posters from the University of Illinois This collection of 66 images is made available through the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA).

Journals and Newspapers

Search various newspaper archives, including the Illustrated London News,Economist, The Sunday Times, The Times, The Telegraph, and the International Herald Tribune Historical Archives.

Limit by "Source Type" to search historical newspapers and periodicals. Proquest Historical Newspapers includes the New York Times Historical Archive

- Times of London Digital Archive (See Gale Primary Sources above--for a combined search with some options for visualizations)

- Economist Historical Archive (See Gale Primary Sources above--for a combined search with some options for visualizations)

- The Times History of the War Print volumes. Libra 940.3 T483. Coverage of the war issued in weekly installments from 1914 to 1918. 22 volumes. Volumes at Libra and available through HathiTrust

- The Times Documentary History of the War . Print volumes. Library 940.92 T483.6. Divided into the diplomatic, naval, miltary and overseas histories.11 volumes. All 11 volumes are available through HathiTrust.

- Belgium under German rule : the deportations . Print volume. Kislak Center Folio D615 .B48 1917 -. From the London Times , 1917.

Foreign Relations Papers

The following are resources available in Van Pelt Library. Clicking on the links will take you to the item's catalog record in Franklin.

U.S. Foreign Relations

- Foreign Relations of the United States : Official documentary history of foreign policy decisions from the U.S. State Department's Office of the Historian.

British Foreign Relations

- British Documents on the Origins of the War, 1898-1914 : 11 volumes. Available through Hein Online, Hathitrust and Libra

- British and Foreign State Papers , 1812-1968 : 170 volumes all available through HeinOnline

- British Documents on Foreign Affairs: Reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print. Series H, The First World War, 1914-1918 : 12 volumes. Available through a variety of print and online editions.

Russian Foreign Relations

- Russia in War and Revolution, 1914-1922: A Documentary History

French Foreign Relations

- Les Origines de la Guerre et la Politique Extérieure de l'Allemagne au Début du XXe Siècle d'Après les Documents Diplomatiques

- Documents Diplomatiques français (1871-1914) 41 volumes. Most volumes available through Hathitrust

German Foreign Relations

- German War Planning, 1891-1914: Sources and Interpretations

WWI Histories

French WWI poster courtesy of the Library of Congress.

War Records

- War Trade Board journal

Official rulings and announcements of the War Trade Board and its Bureaus, from 1917-1919.

23 volumes.

- History of the Great War, based on official documents, by direction of the Historical section of the Committee of Imperial defence : medical services

Covers such topics as casualties and statistics, surgery, diseases and pathology.

- The medical department of the United States Army in the World War

Large, multi-volume series covering all aspects of medical services during World War I.

15 volumes.

- World War records; First Division, A.E.F., Regular

Records on military regiments, including operations, field orders and training.

25 volumes.

- Diplomatic documents relating to the outbreak of the European war

Correspondences and primary sources at the outbreak of the war.

- La Paix de Versailles

Conditions of the Treaty of Versailles, in French.

12 Volumes. Online through Gallica and in print at Van Pelt

- United States Army in the World War, 1917-1919

A series on the organization, policies, training and operations. Also contains reports.

17 volumes.

Economic and Social History of the World War Series

This series published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Division of Economics and History, provides a detailed account of the expense and consequences of the war to all countries involved. Listed below are the series and their call number. volumes may be in storage at Libra or in Van Pelt. Try the following search to bring up all volumes: economic and social history of the world war and author carnegie. If you have difficulty finding the volumes you are looking for, please ask for assistance. (Print and Hathitrust)

Subsets of the series:

| American | 940.92 W2744.8 | Japanese | 940.92 W2744.14 |

| Austro-Hungarian | 940.92 W2744.4 | Polish | 940.92 W2744.20 |

| Belgian | 940.92 W2744.6 | Rumanian | 940.92 W2744.5 |

| British | 940.92 W2744.2 | Russian | 940.92 W2744.12 |

| Czechoslovak | 336.43 R188 | Scandinavian | 940.92 W2744.11 |

| European | 940.92 W2744.7 | Serbian | 940.92 W2744.18 |

| French | 940.92 W2744.5 | Turkish | 940.92 W2744.17 |

| German | 940.92 W2744.13 | General | 940.92 W2744 |

| Italian | 940.92 W2744.9 |

World War I Document Archive

An online resource to support use of primary documents, the World War I Archive is an electronic repository of primary documents from World War One, which has been assembled by volunteers of the World War I Military History List (WWI-L). International in focus, the archive intends to present in one location primary documents concerning the Great War. It includes biographical material, convention and treaty documents, links to other WW I sites, documents available through H-net, and other resources.

- Next: Primary Sources continued >>

- Last Updated: Jun 25, 2023 3:29 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.upenn.edu/WorldWarI

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Propaganda — Ww1 Propaganda Poster Analysis

Ww1 Propaganda Poster Analysis

- Categories: Propaganda Textual Analysis

About this sample

Words: 532 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 532 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, historical context of world war i propaganda, visual analysis of world war i propaganda posters, textual analysis of world war i propaganda posters, impact and effectiveness of world war i propaganda posters.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 617 words

3 pages / 1299 words

2 pages / 783 words

1 pages / 496 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Propaganda

The proliferation of social media platforms has brought about a significant challenge in contending with hate speech and far-right propaganda. The digital age has provided unprecedented opportunities for individuals and groups [...]

Nazi propaganda, a dark and insidious tool of the Nazi regime under Adolf Hitler's leadership, played a pivotal role in shaping the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of the German populace during the Third Reich. This essay [...]

Is there a difference between propaganda and social and political marketing? Propaganda emerged during the first World War as a means to increase state power through battling for the hearts and minds of the masses or, ‘hegemony’ [...]

Lenin and Stalin are two towering figures in the history of the Soviet Union. Both leaders played instrumental roles in shaping the course of the country, and their policies had far-reaching impacts on the lives of millions of [...]

In George Orwell's allegorical novel Animal Farm, the character of Squealer serves as the voice of propaganda and manipulation, using his intelligence and cunning to manipulate the other animals on the farm. Squealer's ability [...]

From Hitler to Hussein, the rise and fall of dictators has captivated historians and writers alike for centuries. British novelist George Orwell (1903-1950) was no exception. In his 1946 allegory Animal Farm, Orwell [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Library of Congress

Prints & photographs online catalog.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- PPOC collections

- Search Tips

- Download Tips

This Collection:

- About this Collection

Background and Scope

- Selected Bibliography

- Related Resources

- Rights And Restrictions

- Creator/Related Names (558)

- Subjects (1592)

- Formats (109)

More Resources

- Prints & Photographs Reading Room

- Ask a Prints & Photographs Librarian

Posters: World War I Posters

Join the brave throng, ca. 1915.

- Search All

- Search This Collection

All images are digitized | All jpegs/tiffs display outside Library of Congress | View All

Introduction

During World War I, the impact of the poster as a means of communication was greater than at any other time during history. The ability of posters to inspire, inform, and persuade combined with vibrant design trends in many of the participating countries to produce thousands of interesting visual works. As a valuable historical research resource, the posters provide multiple points of view for understanding this global conflict. As artistic works, the posters range in style from graphically vibrant works by well-known designers to anonymous broadsides (predominantly text).

The Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division has extensive holdings of World War I era posters. Available online are approximately 1,900 posters created between 1914 and 1920. Most relate directly to the war, but some German posters date from the post-war period and illustrate events such as the rise of Bolshevism and Communism, the 1919 General Assembly election and various plebiscites.

This collection's international representation is among the strongest in any public institution. (For other major holdings, see the Related Resources page.) The majority of the posters were printed in the United States. Posters from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Russia are included as well. The Library acquired these posters through gift, purchase, and exchange or transfer from other government institutions, and continues to add to the collection.

World War I and the Role of the Poster

World War I began as a conflict between the Alllies (France, the United Kingdom, and Russia) and the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary). The assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary and his wife Sophie ignited the war in 1914. Italy joined the Allies in 1915, followed by the United States in 1917. A ceasefire was declared at 11 AM on November 11, 1918.

The poster was a major tool for broad dissemination of information during the war. Countries on both sides of the conflict distributed posters widely to garner support, urge action, and boost morale. During World War II, a larger quantity of posters were printed, but they were no longer the primary source of information. By that time, posters shared their audience with radio and film.

Even with its late entry into the war, the United States produced more posters than any other country. Taken as a whole, the imagery in American posters is more positive than the relatively somber appearance of the German posters.

Poster Themes

The posters in the Prints and Photographs Division deal primarily with recruitment, finance, and home front issues. Although produced in different countries, many designs use symbols and messages that share a common purpose. (To explore the full array of topics and symbols supplied as index terms on individual poster descriptions, see the Subject/Format browse list .)

Enlistment and Recruitment Posters

Many posters asked men to do their duty and join the military forces. In the early years of the war, Great Britain issued a large number of recruitment posters. Prior to May of 1916, when conscription was introduced, the British army was all-volunteer. Compelling posters were an important tool in encouraging as many mean as possible to enlist. Four rarely seen posters printed in Jamaica and addressed to the men of the Bahamas illustrate the point that this war involved many parts of the world beyond the actual battlegrounds [ view Bahamas recruitment posters ].

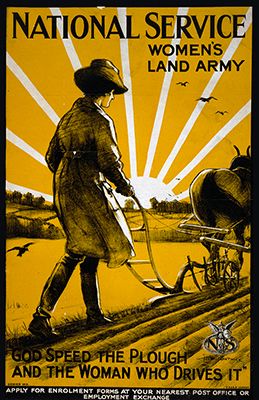

Women, who weren't being recruited for the military, were also asked to do their part. They could serve through relief organizations such as the YWCA or the Red Cross, or through government jobs. The Women's Land Army was originally a British civilian organization formed to increase agricultural production by having women work the land for farmers who were serving in the military. A Women's Land Army was also assembled in the United States.

View selected enlistment posters View selected women's recruitment and relief agency posters

Posters for War Bonds and Funds

In countries where conscription was the norm (France, Germany, Austria), recruitment was not such a pressing need, and most posters were aimed at raising money to finance the war. Those who did not enlist were asked to do their part by purchasing bonds or subscribing to war loans. Many finance posters use numismatic imagery to illustrate their point. Coins transform into bullets, crush the enemy, or become shields in the war effort.

View selected war bonds and funds posters

Posters Dealing with Food Issues

Food shortages were widespread in Europe during the war. Even before the United States entered the war, American relief organizations were shipping food overseas. On the home front, it was hoped that Americans would adjust their eating habits in such a way as to conserve food that could then be sent abroad. Americans were told to go meatless and wheatless and to eat more corn and fish. Americans were also encouraged to plant victory gardens and to can fruits and vegetables. In Great Britain, eggs were collected for the wounded to aid in their recovery. In France, the ComitŽ National de PrŽvoyance et d'Economies sponsored a poster competition among schoolchildren to design conservation posters.

View selected food issues posters

National Symbols

Many of the posters rely on symbolism to illustrate their point. Uncle Sam appears quite frequently on posters as a symbol for the United States. On other posters, John Bull and Britannia represent the United Kingdom, while France is personified by Marianne. Posters produced by the Allies often depict Germany as a caricature called a "Hun" who was usually portrayed wearing a pickelhaube (spiked helmet), often covered in blood.

Whistler's mother, from the painting "Arrangement in Grey and Black," is used to represent all motherhood on one Canadian poster. Men are asked to join the Irish Canadian Rangers and "fight for her."

View selected national symbols posters

The Poster Artists

(Note: Select the name of the artist to view posters he designed.)

Many well-known artists and illustrators contributed their work to the war effort. Even though the British posters were primarily the work of anonymous printers and lithographers, established artists such as Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) , John Hassall (1868-1948) , and Gerald Spencer Pryse (1881-1956) designed posters as well.

In Germany, Lucian Bernhard (1883-1972) produced many posters notable for their typography. Ludwig Hohlwein (1874-1949) , who worked for most of his life in Munich, was internationally recognized for his integration of text and image and his brilliant use of color. In addition to his posters for the war effort, he designed many travel and advertising posters. Some of his last works were posters he designed for the Nazi Party during World War II.

Abel Faivre (1867-1945) , a well-known cartoonist, and Théophile Steinlen (1859-1923) , whose cats and Parisian scenes are some of the most recognizable images of the Belle Époque, lent their skills to the war effort and produced posters of considerable emotional depth.

In the U.S., the Committee on Public Information's Division of Pictorial Publicity urged artists to contribute their work in support of the war effort, and hundreds of poster designs were produced. The Division of Pictorial Publicity accepted Joseph Pennell's design for the Fourth Liberty Loan Drive of 1918, for example, which showed New York City in flames. Although the likelihood of enemy attack was small (aircraft of the day could not cross the Atlantic Ocean), the visual argument made for a haunting poster printed in approximately two million copies. The Prints & Photographs Division is fortunate to have works that show different phases of the design process: the original watercolor sketch , a proof for the poster , and the poster that was distributed .

Howard Chandler Christy (1873-1952) put the Christy girl into wartime service for the Marines and the Navy, as did other poster creators.

James Montgomery Flagg (1870-1960) designed what has become probably the best-known war recruiting poster: "I Want You for U.S. Army" [ view poster ]. Said to be a self-portrait, this most recognized of all American posters is also one of the most imitated. Flagg had adapted his design from Alfred Leete's 1914 poster of Lord Kitchener . Posters employing a similar composition were used on both sides of the conflict [ view examples ]. The American poster was altered slightly for use in World War II [ view poster ]. Since then, this image of Uncle Sam has been modified and parodied countless times [ view examples of parodies ].

For a full list of names included as index terms on individual poster descriptions, see the browse lists of creators and other associated names .

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

David's ESOL Blog

Tips for efl / esol teachers.

A war of words – poetry and propaganda in World War I

Poppy Field (Photo credit: Neilhooting)

95 years ago, the guns fell silent across the Western Front, as the Armistice took effect, leaving behind four years of destruction on a previously unimaginable scale. This conflict marked the lives of a generation of poets, who are studied in English literature classes in the United Kingdom. Yesterday was Remembrance Sunday, and in honour of this day, here is a lesson plan designed around one of my favourite poems from the First World War, ‘Dulce et decorum est’ by Wilfred Owen.

This lesson plan is designed to last for three two- hour sessions, and is suitable for advanced students, from B2+ to C2.

Session 1 – Who’s for the game?

This session focuses on the early propaganda aimed at convincing the young men of Britain to join up to fight for their country as the war began. The poem we will examine is ‘ Who’s for the game? ‘ by Jessie Pope.

As a way of introducing the theme, use the following video, which presents some of the propaganda posters used to encourage men to volunteer for the armed forces.

Then draw attention to the role played by women in the posters – some posters address women directly, urging them to convince their husbands and boyfriends to join up. This will provide the link to the poem for today, written by a woman but addressed to young men.

Give the students a copy of the poem and allow them to read it, helping with vocabulary if necessary. Once they have finished, in pairs get them to complete a T-chart with sports terms on one side and references to the war on the other. In reality, there are few direct references to the war. Most of the images are related to something which the young men of the time would be very familiar with – the sports’ field. At this point, it is a good idea to focus on any students who are particularly sporty in the class, and ask them for their reactions to what Pope is saying. Would you really want to be left on the sidelines? Have you ever suffered an injury as a result of your sport? What was your reaction?

Finally, examine the language itself, focusing on the elements which can be considered persuasive. Here it is important to focus on the direct address used throughout the poem by Pope, which echoes the language and images of many of the posters seen earlier – notably the image of Kitchener pointing out of the poster at ‘YOU’ reproduced above. The informal register of the poem is also important, addressing the ‘lads’ as peers, creating the illusion of peer pressure. To work on these elements of language, you can use this worksheet.

To finish the session, watch the first part of the video which will be used to start Session two, up to the point where the soldiers are on parade (0:16).

Session 2 – The reality of war

This second session focuses on the reality of the war which the recruits found when they arrived at the front line. We will read a brief biography of Wilfred Owen and we will focus on his poem, ‘ Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori ‘.

To begin the session, we return to the video which closed session 1, but this time the students should watch to the end. Ask students to give their impressions of the differences between the ideal which Pope was selling to the young men and the reality they faced on the Western Front.

After a brief discussion, it is time to give the students more details about life in the trenches. The following video by Dan Snow examines the conditions that the soldiers faced in the trenches.

Wilfred Owen

The presentation of the biography of Wilfred Owen can be done in various ways. The students can be asked to research his life as homework after the first session, or they can be asked to research in class if they have access to internet or reference material. Alternatively, you can use this worksheet and have them read it in class, or adapt it as a jigsaw reading activity / running dictation . They should receive the following key information:

Portrait of Wilfred Owen (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

• D.O.B – 18th of March 1893 • Became a teacher of English in 1913 • Enlisted in Artists’ Rifles on 21/10/15;14 months training in England • Total war experience was short: four months, only 5 weeks on front line • After experiencing war first hand, Owen became strongly anti-war. People at home had no idea of what war was like & wanted to persuade them against it. • Owen was killed in war on 4th Nov 1918 • War ended 11th November 1918 at 11 o’clock. Owen’s family received the telegram informing them of his death as the church bells of the village rang to celebrate the end of the war.

Give the students the first part of the poem – up to ‘Of gas shells dropping softly behind’:

‘Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs, And towards our distant rest began to trudge. Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots, But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind; Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.’

Work on any vocabulary the students need. In pairs, have the students work on a mindmap around the concept ‘Emotions’. How do the soldiers feel at this point in the poem? Once the students have worked on their mindmaps, have them change pairs and compare their ideas. Then give them the rest of the poem and have them add to their mindmaps:

‘Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! — An ecstasy of fumbling Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time, But someone still was yelling out and stumbling And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.— Dim through the misty panes and thick green light, As under a green sea, I saw him drowning. In all my dreams before my helpless sight He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace Behind the wagon that we flung him in, And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin, If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs Bitter as the cud Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, — My friend, you would not tell with such high zest To children ardent for some desperate glory, The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.’

Share the ideas from the pairs in class.

Focus on the change of address in the last stanza. Here, just as in the poem by Pope, the poet addresses a reader directly. But who? Who is ‘My friend’? Allow the students to express their ideas. If they need help, remind them of Owen’s biography – he volunteered in 1915, inspired by the propaganda of the time. The original dedication of this poem was ‘To a certain poetess’ – this is Owen’s answer to Pope and her ‘Who’s for the game?’

As a final exercise, have the students compare the emotions expressed in ‘Who’s for the game?’ with those expressed by Owen in ‘Dulce et decorum est…’ Also have them look back at the propaganda posters they worked on in the first session, and include the emotions expressed there.How does the reality measure up to the propaganda?

In the next post, I will present the final session in this scheme of work – ‘Lest we forget’, and possible ideas for extension.

Share this:

2 thoughts on “ a war of words – poetry and propaganda in world war i ”.

Pingback: A war of words – Part II | David's ESOL Blog

Reblogged this on David's ESOL Blog and commented:

As we prepare to commemorate the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War, I thought I would revive this post which has ideas for lessons based around the poetry which grew from the horrors of war.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

learning to teach and teaching to learn

Free resources for language teachers by language teachers

This is my personal blog. I´m very interested in learning, teaching and sharing. I want to share ideas about teaching and learning, education technology and web tools to enrich my lessons as well as learn from all those who visit me here

Database of English language resources

Thoughts about personalized and adaptive learning in ELT

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- An Ordinary Man, His Extraordinary Journey

- Hours/Admission

- Nearby Dining and Lodging

- Information

- Library Collections

- Online Collections

- Photographs

- Harry S. Truman Papers

- Federal Records

- Personal Papers

- Appointment Calendar

- Audiovisual Materials Collection

- President Harry S. Truman's Cabinet

- President Harry S. Truman's White House Staff

- Researching Our Holdings

- Collection Policy and Donating Materials

- Truman Family Genealogy

- To Secure These Rights

- Freedom to Serve

- Events and Programs

- Featured programs

- Civics for All of US

- Civil Rights Teacher Workshop

- High School Trivia Contest

- Teacher Lesson Plans

- Truman Library Teacher Conference 2024

- National History Day

- Student Resources

- Truman Library Teachers Conference

- Truman Presidential Inquiries

- Student Research File

- The Truman Footlocker Project

- Truman Trivia

- The White House Decision Center

- Three Branches of Government

- Electing Our Presidents Teacher Workshop

- National History Day Workshops from the National Archives

- Research grants

- Truman Library History

- Contact Staff

- Volunteer Program

- Internships

- Educational Resources

You're the Author: WWI Propaganda Creation Project

In this lesson, students will view a variety of examples of WWI propaganda posters and discuss their message and why they were important for the war effort. After the discussion, students will create their own examples of WWI propaganda posters.

To inform students why WWI propaganda posters were so effective and important for the war effort.

- Define the concept of propaganda.

- Explain why the use of propaganda was of particular significance during this time period.

- Evaluate the different strategies and tools used in the creation of propaganda.

- Demonstrate their knowledge of propaganda characteristics, strategies, and tools by creating their own piece of propaganda.

- 9-12.AH.3.CC.B - Evaluate the motivations for United States’ entry into WWI.

- 9-12.AH.3.PC.D - Assess the impact of WWI related events, on the formation of “patriotic” groups, pacifist organizations, and the struggles for and against racial equality, and diverging women’s roles in the United States.

WWI Propaganda posters - examples can be found at http://www.ww1propaganda.com/ , http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/wwipos/background.html , http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object-groups/women-in-wwi/war-posters , and other various internet and print sources

DAY 1 Students will walk into the classroom that has various examples of WWI propaganda posters (see primary sources above) on the walls. Students will walk around the classroom examining the posters and write quick notes about the posters. Students will pay close attention to:

- Message/theme

- Effectiveness

- Author/organization

After students have had time to examine the posters, the class will discuss propaganda What does propaganda mean? Propaganda is information that is spread for the purpose of promoting a cause or belief. During WWI, posters were used to

- Recruit men to join the army

- Recruit women to work in the factories and in the Women’s Land Army

- Encourage people to save food and not to waste it

- Keep morale high and encourage people to buy government bonds

Why were propaganda posters needed during WWI? Countries only had small standing, professional armies at the start of the war They desperately needed men to join up and fight Most people did not own radios and TVs had not yet been invented The easiest way for the government to communicate with the people was through posters stuck on walls in all the towns and cities How were men encouraged to join the army? Men were made to feel unmanly and cowardly for staying at home How were women used to encourage men to join the army? Women were encouraged to pressurise their husbands, boyfriends, sons, and brothers to join up How was fear used? Some posters tried to motivate men to join up through fear Posters showed the atrocities that the Germans were said to be committing in France and Belgium People were encouraged to fear that unless they were stopped, the Germans would invade Britain and commit atrocities against their families How were women encouraged to work in the factories or to join the army or the land girls? When the men joined the war, the women were needed to do their jobs There was a massive need for women in the factories, to produce the weapons, ammunition and uniforms needed for the soldiers There was a major food shortage and women were desperately needed to grow food for the people of Britain and the soldiers in France Posters encouraged everyone to do their bit Through joining up Through working for the war effort By not wasting food Through investing in government bonds Why are WWI propaganda posters important? For historians today, propaganda posters of WWI reveal the values and attitudes of the people at the time They tell us something about the feelings in Britain during WWI Class will discuss the assignment (poster creation) Students will begin brainstorming ideas for their own propaganda posters in small groups Students will begin creating their propaganda posters

DAY 2 Students will continue working to create their propaganda posters

DAY 3 Students will be given 15 minutes to finish their posters and hang them up around the classroom Students will walk around the room and look at the posters created by their classmates Students will play close attention to:

Directions: You will create an effective propaganda poster on one of the topics below that could have been used in World War I. • Possible topics: • Enlistment and recruitment • The role of women • Financing the war • Food conservation • Aiding our allies • Entering the war • Guidelines • The poster will be drawn or printed (using photoshop or etc) on 8 ½” by 11” paper and graded on your use of message/theme, creativity, neatness, historical accuracy, explanation, and use of characteristics/techniques

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

To convince Americans that going to war in Europe was necessary, Wilson created the Committee on Public Information (CPI), to focus on promoting the war effort. To head up the committee, Wilson ...

World War I was a conflict that not only consumed the lives of the soldiers in the trenches and battlefields, but also had a powerful impact on the hearts and minds of millions at home. This was done through the strategic use of propaganda. The proactive manipulation of people's attitudes through the media played a surprisingly pivotal role in shaping public opinion and mobilizing resources.

The Impact of Nazi Propaganda: Visual Essay. Explore a curated selection of primary source propaganda images from Nazi Germany. Propaganda was one of the most important tools the Nazis used to shape the beliefs and attitudes of the German public. Through posters, film, radio, museum exhibits, and other media, they bombarded the German public ...

Propaganda in World War I. World War I was the first war in which mass media and propaganda played a significant role in keeping the people at home informed on what occurred at the battlefields. [1] [page needed] It was also the first war in which governments systematically produced propaganda as a way to target the public and alter their opinion.

U.S. newspaper coverage of World War I (1914-18) provides a unique perspective on wartime propaganda. The scope of articles and images clearly exhibits America's evolution from firm isolationism in 1914 to staunch interventionism by 1918. Once American soldiers joined the war, public opinion at home changed. And newspapers helped change it.

As students become comfortable with evaluating propaganda posters, consider asking them to select a poster or two from the Library of Congress online collections for close analysis and to better understand the evolving public opinion of American involvement throughout the war. Students could identify the message, the target audience, any subtext, and how the artist is trying to convince the ...

Propaganda played an important part in the politics of the war, but was only successful as part of wider political and military strategies. For each belligerent, the most effective and important forms of propaganda were aimed at its own domestic population and based on consensus. As part of this, the Allies largely managed relations with their own newspapers and other media by negotiated ...

Slide 1 of 3, A child on a street selling newspapers to passers-by during World War One, People in Britain wanted to know what was happening But the Government knew spies might read the papers. A ...

War of Words: Propaganda of World War I. Submitted by cleveland on Thu, 06/14/2018. World War I (1914-1918) was different than any previous war. It was a total war that required all members of the nation to be involved in the war effort. All of the resources of the state were mobilized for war. Ultimately, 65,000,000 soldiers from 30 countries ...

Ask students whether they believe advertisements, news stories, and social media posts are effective in influencing our attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors. Emphasize that this lesson, while focusing on news and propaganda from World War I, will help introduce skills that are needed to avoid being duped by misleading information in today's world.

World War 1 Propaganda Essay. World War 1, beginning from August 1914 to November 1918, was ultimately a time of demise for European countries. During this time, the use of propaganda became widespread and significant to be considered a turning point for World War 1. The power of image became largely recognized as important because of each ...

The First World War. This First World War portal includes primary source materials for the study of the Great War, complemented by a range of secondary features. The collection is divided into three modules: Personal Experiences, Propaganda and Recruitment, and Visual Perspectives and Narratives. Women, War and Society, 1914-1918.

Student will also be graded on satisfactorily identifying the poster's audience, explaining the meaning of the poster, as well as deciding the effectiveness of each poster. Each of these three will be graded on the same number system as above, 5 to 10. Students will analyze American propaganda posters from World War 1, the Great War.

World War I propaganda posters played a pivotal role in influencing public opinion and garnering support for the war effort. These posters were designed to evoke strong emotions, appeal to patriotism, and mobilize the masses towards the war. By analyzing the visual and textual elements of these posters, we can gain valuable insights into the ...

Background and Scope Introduction During World War I, the impact of the poster as a means of communication was greater than at any other time during history. The ability of posters to inspire, inform, and persuade combined with vibrant design trends in many of the participating countries to produce thousands of interesting visual works. As a valuable historical research resource, the posters ...

A war of words - poetry and propaganda in World War I. 95 years ago, the guns fell silent across the Western Front, as the Armistice took effect, leaving behind four years of destruction on a previously unimaginable scale. This conflict marked the lives of a generation of poets, who are studied in English literature classes in the United Kingdom.

Propaganda Effects of World War One Essay examples. It must be emphasized that the ultimate object of propaganda in war is the destruction of enemy morale, and its corollary, the strengthening of friendly morale. "It consists of the dissemination of ideas, designed to react in different ways upon their various recipients. ...

Propaganda Posters WW1. The propaganda posters of World War 1 had several different purposes. One of these purposes was to obtain man power for the battles of the war. Another reason was to obtain money for financing the war. A third reason for the posters was to spark nationalism within the respective countries of which the posters were made.

World War 1 Propaganda Essay. For this assignment I chose the piece of World War I propaganda that reads "Beat back the Hun with Liberty Bonds" across a large body of water,which is specified as being the Atlantic, with a bloody and beady-eyed German soldier looming at the edge of the water. The German soldier is represented as quite ...

propaganda of the "Belgian atrocities" of 1914 in the context both of domestic and international politics and of the military conduct of the war.[1] The purpose of this essay is to provide an overview of the major propaganda organisations, policies and ideas of the main belligerents of the war, with an emphasis on the British about who most is

Propaganda is information that is spread for the purpose of promoting a cause or. belief. During WWI, posters were used to. Recruit men to join the army. Recruit women to work in the factories and in the Women's Land Army. Encourage people to save food and not to waste it.

World War 1 Propaganda Essay. During the First World War Government propaganda played a crucial role during war and it also played and important role in the nation's culture and society. Propaganda took form of posters, paintings, photographs, books, articles, leaflets, pamphlets, and newspapers and sometimes letters.

The Pros And Cons Of Propaganda. Propaganda was an important tool which was used during World was 11. The purpose it played was to change the way people viewed what was happening during the war. Persuasion was used in the form of posters, art, and television in order to change people's perspectives.