Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Architecture: integration of art and engineering.

1. Introduction

2. contributions, 3. discussion and comments, 4. conclusions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Kapliński, O.; Bonenberg, W. (Eds.) Architecture and Engineering: The Challenges—Trends—Achievements ; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; 362p, Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/books/pdfview/book/3233 (accessed on 1 January 2021.).

- Kapliński, O.; Bonenberg, W. Architecture and Engineering: The Challenges—Trends—Achievements. Buildings 2020 , 10 , 181. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, S.; Bertagna, F.; Ohlbrock, P.O.; Tanadini, D. The Canopy: A Lightweight Spatial Installation Informed by Graphic Statics. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 1009. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J. Architectural Characteristics of Different Configurations Based on New Geometric Determinations for the Conoid. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jóźwik, A. Application of Glass Structures in Architectural Shaping of All-Glass Pavilions, Extensions, and Links. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 1254. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Li, B.; Guo, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Caneparo, L. The Third Solar Decathlon China Buildings for Achieving Carbon Neutrality. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 1094. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hu, R.; Iturralde, K.; Linner, T.; Zhao, C.; Pan, W.; Pracucci, A.; Bock, T. A Simple Framework for the Cost–Benefit Analysis of Single-Task Construction Robots Based on a Case Study of a Cable-Driven Facade Installation Robot. Buildings 2021 , 11 , 8. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C. Digital Simulation for Buildings’ Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Urban Neighborhoods. Buildings 2021 , 11 , 541. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Maksoud, A.; Mushtaha, E.; Al-Sadoon, Z.; Sahall, H.; Toutou, A. Design of Islamic Parametric Elevation for Interior, Enclosed Corridors to Optimize Daylighting and Solar Radiation Exposure in a Desert Climate: A Case Study of the University of Sharjah, UAE. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 161. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kołata, J.; Zierke, P. The Decline of Architects: Can a Computer Design Fine Architecture without Human Input? Buildings 2021 , 11 , 338. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Butelski, K.L. Contemporary Odeon Buildings as a Sustainable Environment for Culture. Buildings 2021 , 11 , 308. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Taraszkiewicz, A.; Grębowski, K.; Taraszkiewicz, K.; Przewłócki, J. Medieval Bourgeois Tenement Houses as an Archetype for Contemporary Architectural and Construction Solutions: The Example of Historic Downtown Gdańsk. Buildings 2021 , 11 , 80. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Targowski, W.; Kulowski, A. Influence of the Widespread Use of Corten Plate on the Acoustics of the European Solidarity Centre Building in Gdańsk. Buildings 2021 , 11 , 133. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Niebrzydowski, W. The Impact of Avant-Garde Art on Brutalist Architecture. Buildings 2021 , 11 , 290. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Anghel, A.A.; Cabeza-Lainez, J.; Xu, Y. Unknown Suns: László Hudec, Antonin Raymond and the Rising of a Modern Architecture for Eastern Asia. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 93. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liu, W.-F.; Tzeng, C.-T.; Kuo, W.-C. Historical Cultural Layers and Sustainable Design Art Models for Architectural Engineering—Took Public Art Proposal for the Tainan Bus Station Construction Project as an Example. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 1098. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Malewczyk, M.; Taraszkiewicz, A.; Czyż, P. Preferences of the Facade Composition in the Context of Its Regularity and Irregularity. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 169. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lee, K. The Interior Experience of Architecture: An Emotional Connection between Space and the Body. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 326. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Celadyn, M.; Celadyn, W. Apparent Destruction Architectural Design for the Sustainability of Building Skins. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 1220. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Park, E.J.; Lee, S. Creative Thinking in the Architecture Design Studio: Bibliometric Analysis and Literature Review. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 828. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Celadyn, M.; Celadyn, W. Application of Advanced Building Techniques to Enhance the Environmental Performance of Interior Components. Buildings 2021 , 11 , 309. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jung, C.; Mahmoud, N.S.A.; El Samanoudy, G.; Al Qassimi, N. Evaluating the Color Preferences for Elderly Depression in the United Arab Emirates. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 234. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Zou, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhou, X. Optimal Design and Verification of Informal Learning Spaces (ILSs) in Chinese Universities Based on Visual Perception Analysis. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 1495. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Średniawa, P. Szósty zmysł architektury. Zawód Archit. 2022 , 86 , 80–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- Walter, H. Social cognitive neuroscience of empathy: Concept, circuits and genes. Emot. Rev. 2012 , 4 , 9–17. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- AIA 2030 Commitment: Architects Prepare to Meet the Challenge. Available online: https://www.aiachicago.org/images/uploads/pdfs/2030-housing-focus-presentation.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2022).

Click here to enlarge figure

| Author | Subject of the Research | Research Problem | Research Techniques Instrumentality | Subject Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Canopy—a lightweight spatial installation The design and fabrication process of the temporary installation | The geometry of the perforated hanging membrane | Graphic statics Relationship between form diagram and force diagram. | Structural aspects and design | |

| The Conoid The Antisphera A revolution of forms | The evolution of new architectural forms Calculus of surface areas | A differential geometry procedure. Parametric design | ||

| Glass structures All-glass pavilions, extensions, and links | Indication of the relationship between functional and spatial aspects, form and structure. Shaping all-glass structures in buildings | EN 1990:2002 + A1 Eurocode-Basis of structural design—Section 5.2 Design assisted by testing. | ||

| The Third Solar Decathlon China (SDC) | Architecture vs. carbon dioxide emissions. Defining active and passive technologies | Scoring of 15 competition solutions | ||

| Facade installation. Curtain wall modules; | A case study of a cable-driven facade installation robot, cost–benefit analysis (CBA) | Single-task construction robots (STCRs) | ||

| Thermal comfort. The Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) Two districts in Beijing | The study of buildings’ outdoor thermal comfort in urban areas | Longer-term, digital techniques Grasshopper 3D and Rhinoceros 3D. Three-dimensional models | Digitization | |

| The University of Sharjah’s (UoS) campus | Improving the visual and environmental conditions of the interior Optimize daylighting and solar radiation exposure | Parametric design. The Ladybug tool for Grasshopper. Rhinoceros 3D. Solar radiation analysis | ||

| Designer position in architecture The replacement of humans by machines | Will computers eliminate the human factor in the design? | Literature review Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)/Strong Artificial Intelligence (SAI) Active Augmented Reality | ||

| Odeons: form, function. The Odeon in Biała Podlaska, Amphitheater in the Royal Baths Park in Warsaw | Mobile forms of roofing | Typology of open cultural spaces | Architectural Heritage | |

| Medieval Bourgeois Tenement Houses The historical centre of Gdańsk | Archetype for contemporary architectural and construction solutions | Iconographic analysis. 3D modelling of structural systems | ||

| The European Solidarity Center. Corten plates usage | Influence of material homogeneity on room acoustics | Reverberation time Flutter echo | ||

| Brutalist architecture | Identification and characterization the most important ideas and principles common to avant-garde art | Historical interpretative studies. Studies of buildings in situ | ||

| Historical origins modern architecture in East Asia. Space syntax | Preserving the architects’ legacy Historical research | Syntactic approach to architectural composition | ||

| The Tainan bus station construction project Artistic symbol of urban architectural | Modern urban renewal Balancing the cultural value of historic buildings | The Delphic Hierarchy Process (DHP). The AHP expert questionnaire. The MATLAB, a compiling software. | ||

| Multi-family housing Aesthetics-expectations of recipients | The degree of the composition regularity of the facade elements | Online questionnaire Social network (Facebook) Psychology and neurosciences elements | Aesthetics and emotions vs. engineering | |

| An emotional connection between space and the body. A phenomenological understanding of interior space | How people experience interior space Which aspects improve the quality of spatial and emotional experience | Multi-sensory experience and emotional connection: A review | ||

| The sustainability of building skins. The building’s enclosure as an active boundary Aesthetical longevity | Technical durability and aesthetical longevity of building skins | The proposed Apparent Destruction Architectural Design (ADAD) | ||

| Design studio Creative design pedagogy | Increasing the creativity of students in the design studio. | Bibliometric analysis | ||

| Aesthetic functionalism; Sensorial experiences | Improving the Environmental Performance of Interiors | creative introduction of advanced construction techniques | Interior architecture | |

| The Seniors’ Happiness Centre in Ajman UAE. Architectural design for elderly with depression | Colour therapy The physiological and psychological responses Colour preferences | A survey using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) Electroencephalogram (EEG | ||

| Informal learning space (ILS) | The relation between users’ perceptions and the spatial environments | Visual perception analysis. Eye tracking technique |

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Kapliński, O. Architecture: Integration of Art and Engineering. Buildings 2022 , 12 , 1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12101609

Kapliński O. Architecture: Integration of Art and Engineering. Buildings . 2022; 12(10):1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12101609

Kapliński, Oleg. 2022. "Architecture: Integration of Art and Engineering" Buildings 12, no. 10: 1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12101609

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

The Close Relationship Between Art and Architecture in Modernism

- Written by Camilla Ghisleni | Translated by Tarsila Duduch

- Published on July 21, 2023

The idea of integration between art and architecture dates back to the very origin of the discipline, however, it took on a new meaning and social purpose during the Avant-Garde movement of the early twentieth century, becoming one of the most defining characteristics of Modernism . This close relationship is evident in the works of some of the greatest modern architects, such as Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Oscar Niemeyer, to name a few.

Needless to say, modernism emerged from an expectation of moral and material reconstruction of a world devastated by war, serving as a tool to strengthen a collective identity and, consequently, the bond between the city and its inhabitants. In this context, artistic expression is used as a tool to shape the emotional life of the user, to which art and architecture combined can give a new meaning, offering a place that represents a sense of community, in addition to function and technique.

The professional development at Bauhaus was marked by what Argan (1992) calls "methodological-didactic rationalism," encouraging the unification of all the arts through a Gesamtkunstwerk , which roughly translates as a "total work of art," incorporating architecture, painting, sculpture, industrial design, and crafts. This collaboration was expected to happen even on the building site, thus bringing together intellectual and manual work in a shared experience. As their leading exponent Walter Gropius used to say, an architect should be as familiar with painting as a painter should be with architecture. One should not design a building and commission a sculptor afterward; this would be wrong and detrimental to the architectural unity.

Apart from the Bauhaus program, this integration between disciplines was also, and most notably, brought up by Le Corbusier through the combination of elements from painting and sculpture with the formal concepts of architecture. In this sense, Le Corbusier - despite being a "one-man show" who preached the synthesis of the arts in his designs, but always worked as a solo artist - argued that the roles of architects, painters, and sculptors were of equal importance contributing to productive collaborations in the real world, that is, on the building site, by creating and designing in complete harmony.

To some extent, this inseparable relationship sounded so utopian that Lucio Costa stated that this greater art would require a level of cultural and aesthetical evolution that was almost impossible to achieve, in which architecture, sculpture, and painting would form one cohesive body, a living organism that could not be disintegrated. Nevertheless, the Capanema Palace in Rio de Janeiro is arguably the closest one could get to this utopia in Brazil by relying on painter Candido Portinari, sculptor Bruno Giorgi and landscape architect Burle Marx from the very beginning of the project development. As French historian Yves Bruand states, the result is an ensemble of great artistic value, brilliantly enhancing and complementing architecture, but subordinated to it at the same time.

While his works turned out to be prime examples of the fusion of architecture and art, Oscar Niemeyer also shared Costa's opinion that only in extraordinary circumstances could a true synthesis of the arts be achieved. He also stressed the crucial need to establish a team that would work together from the very beginning of the architectural sketches to amicably discuss the problems and smallest details of the project, without dividing them into specialized fields but considering them as a single balanced entity.

The ideal goal is to integrate all disciplines from the beginning of the project, but inviting artists to participate later in the design process does not necessarily compromise the final result. A good example is the Salão Negro (Black Room) at the National Congress in Brasília, where artist Athos Bulcão, invited by Niemeyer after the project was finished, created an abstract and simple language using black granite on the floor and white marble on the walls, which resulted in a mural fully integrated with the architecture and building materials. This mural with abstract patterns is often cited by academics, including Paul Damaz when he states that non-figurative language is the best match for modern architecture. In this regard, the author also mentions Maria Martins' semi-figurative bronze sculpture in the gardens of the Palácio da Alvorada , highlighting the "formal affinity between the curves" of the sculpture and the "graceful pillars of the building," as a perfect example of integration.

However, while Damaz praises the integration between architecture and art in Oscar Niemeyer's projects, he rejects one of the most important examples of integration between disciplines in the history of modernism, which is Mexico City's UNAM Campus . This complex is one of the most emblematic architectural achievements in Mexico, a country considered to be a pioneer in the incorporation of art into architecture, as seen in their tradition of mural painting since the 1920s. Inaugurated in 1952, parallel to the CIAM VIII, the University Campus was designed by more than 100 architects, as well as engineers, artists, and landscape designers. Some of the most remarkable artworks featured in the project are the murals by Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Juan O'Gorman, and Francisco Eppens, which were criticized by the author for being figurative, creating a disparity in style between social realism and functionalist architecture, to the detriment of the latter. Nevertheless, despite the critiques, one cannot ignore the fact that UNAM is an open-air art museum and an example of cooperation and collectivity.

On a different scale but equally important, is integration between art and architecture through the inclusion of occasional individual elements such as the iconic Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe. Indeed, the sculpture Der Morgen , also known as Alba, by German sculptor Georg Kolbe (1877-1947) is not essential to the pavilion. But what else is essential in this new architectural concept, if not only the arrangement of planes and vertical supports? The pavilion is completely independent of the sculpture, as well as of the materials however, one cannot picture it today without this human figure with arms outstretched precisely positioned and framed for the user's experience. As Claudia Cabral beautifully explains, "in Mies' delicate balance, guided by partial asymmetries, and by a system of compensations, the sculpture is the only element that has no counterpart [...] Mies decided to place only one sculpture, a single figurative element in his abstract plane. Within the pavillions play with reflections, transparency, and parallels, we are the only possible partners for the bronze figure, we humans of flesh and blood, the visitors."

.jpg?1620863172)

Every form of integration of different disciplines consists of a coherent dialogue between architects, painters, and sculptors, whether from the very beginning of the project development or later on, during construction, whether on a large scale or with individual elements. Having this in mind, it is very alarming to witness events such as the relocation of the panels by artist Athos Bulcão in the Planalto Palace in Brasilia in 2009 due to a renovation. Even the Athos Bulcão Foundation - Fundathos opposed it since the original location was defined by Athos himself, along with Niemeyer while he was designing the palace in 1950.

As Rino Levi once said, architecture is not secondary, but neither is it the mother of all arts. There is only one art and its value is measured by the emotions it triggers in us. Painting and sculpture can be independent, however, when applied to architecture, they become part of a whole. This lesson on collectivity and shared experiences starts during project development and touches every single person who has the opportunity to visit the architectural work.

Reference List ARGAN, Giulio Carlo. Arte Moderna [Modern art]. São Paulo: Cia das Letras, 1992. BRUAND, Yves. Arquitetura contemporânea no Brasil. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2010. CABRAL, Cláudia Costa. Arte e arquitetura moderna em três projetos de Oscar Niemeyer [Art and modern architecture in three projects by Oscar Niemeyer]. DOCOMOMO Brasil, Salvador, 2019. CABRAL, Cláudia Costa. Arquitetura moderna e escultura figurativa: a representação naturalista no espaço moderno [Modern architecture and figurative sculpture: naturalist representation in modern spaces]. DOCOMOMO Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 2009. DAMAZ, Paul. Art in Latin American Architecture. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1963. DIÓGENES, Beatriz Helena Nogueira ; PAIVA, Ricardo Alexandre. Diálogo entre arte e arquitetura no modernismo em Fortaleza [Dialogue between art and architecture of modernism in Fortaleza]. DOCOMOMO Brasil, Recife, 2016. TAVARES, Camila Christiana de Aragão. A integração da arte e da arquitetura em Brasília: Lucio Costa e Athos Bulcão [The integration of art and architecture in Brasília: Lucio Costa and Athos Bulcão]. Dissertação de mestrado [Master's Thesis] UNB, Brasília.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topic: Collective Design . Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and projects. Learn more about our monthly topics . As always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us .

Editor's Note: This article was originally published on June 01, 2021.

Image gallery

- Sustainability

世界上最受欢迎的建筑网站现已推出你的母语版本!

想浏览archdaily中国吗, you've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

- Review article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2020

Senses of place: architectural design for the multisensory mind

- Charles Spence ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2111-072X 1

Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications volume 5 , Article number: 46 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

244k Accesses

82 Citations

34 Altmetric

Metrics details

Traditionally, architectural practice has been dominated by the eye/sight. In recent decades, though, architects and designers have increasingly started to consider the other senses, namely sound, touch (including proprioception, kinesthesis, and the vestibular sense), smell, and on rare occasions, even taste in their work. As yet, there has been little recognition of the growing understanding of the multisensory nature of the human mind that has emerged from the field of cognitive neuroscience research. This review therefore provides a summary of the role of the human senses in architectural design practice, both when considered individually and, more importantly, when studied collectively. For it is only by recognizing the fundamentally multisensory nature of perception that one can really hope to explain a number of surprising crossmodal environmental or atmospheric interactions, such as between lighting colour and thermal comfort and between sound and the perceived safety of public space. At the same time, however, the contemporary focus on synaesthetic design needs to be reframed in terms of the crossmodal correspondences and multisensory integration, at least if the most is to be made of multisensory interactions and synergies that have been uncovered in recent years. Looking to the future, the hope is that architectural design practice will increasingly incorporate our growing understanding of the human senses, and how they influence one another. Such a multisensory approach will hopefully lead to the development of buildings and urban spaces that do a better job of promoting our social, cognitive, and emotional development, rather than hindering it, as has too often been the case previously.

Significance statement

Architecture exerts a profound influence over our well-being, given that the majority of the world’s population living in urban areas spend something like 95% of their time indoors. However, the majority of architecture is designed for the eye of the beholder, and tends to neglect the non-visual senses of hearing, smell, touch, and even taste. This neglect may be partially to blame for a number of problems faced by many in society today including everything from sick-building syndrome (SBS) to seasonal affective disorder (SAD), not to mention the growing problem of noise pollution. However, in order to design buildings and environments that promote our health and well-being, it is necessary not only to consider the impact of the various senses on a building’s inhabitants, but also to be aware of the way in which sensory atmospheric/environmental cues interact. Multisensory perception research provides relevant insights concerning the rules governing sensory integration in the perception of objects and events. This review extends that approach to the understanding of how multisensory environments and atmospheres affect us, in part depending on how we cognitively interpret, and/or attribute, their sources. It is argued that the confusing notion of synaesthetic design should be replaced by an approach to multisensory congruency that is based on the emerging literature on crossmodal correspondences instead. Ultimately, the hope is that such a multisensory approach, in transitioning from the laboratory to the real world application domain of architectural design practice, will lead on to the development of buildings and urban spaces that do a better job of promoting our social, cognitive, and emotional development, rather than hindering it, as has too often been the case previously.

Introduction

We are visually dominant creatures (Hutmacher, 2019 ; Levin, 1993 ; Posner, Nissen, & Klein, 1976 ). That is, we all mostly tend to think, reason, and imagine visually. As Finnish architect Pallasmaa ( 1996 ) noted almost a quarter of a century ago in his influential work The eyes of the skin: Architecture and the senses, architects have traditionally been no different in this regard, designing primarily for the eye of the beholder (Bille & Sørensen, 2018 ; Pallasmaa, 1996 , 2011 ; Rybczynski, 2001 ; Williams, 1980 ). Elsewhere, Pallasmaa ( 1994 , p. 29) writes that: “The architecture of our time is turning into the retinal art of the eye. Architecture at large has become an art of the printed image fixed by the hurried eye of the camera . ” The famous Swiss architect Le Corbusier ( 1991 , p. 83) went even further in terms of his unapologetically oculocentric outlook, writing that: “I exist in life only if I can see”, going on to state that: “I am and I remain an impenitent visual—everything is in the visual” and “one needs to see clearly in order to understand”. Commenting on the current situation, Canadian designer Bruce Mau put it thus: “We have allowed two of our sensory domains—sight and sound—to dominate our design imagination. In fact, when it comes to the culture of architecture and design, we create and produce almost exclusively for one sense—the visual.” (Mau, 2018 , p. 20; see also Blesser & Salter, 2007 ).

Such visual dominance makes sense or, at the very least, can be explained or accounted for neuroscientifically (Hutmacher, 2019 ; Meijer, Veselič, Calafiore, & Noppeney, 2019 ). After all, it turns out that far more of our brains are given over to the processing of what we see than to dealing with the information from any of our other senses (Gallace, Ngo, Sulaitis, & Spence, 2012 ). For instance, according to Felleman and Van Essen ( 1991 ), more than half of the cortex is engaged in the processing of visual information (see also Eberhard, 2007 , p. 49; Palmer, 1999 , p. 24; though note that others believe that the figure is closer to one third). This figure compares to something like just 12% of the cortex primarily dedicated to touch, around 3% to hearing, and less than 1% given over to the processing of the chemical senses of smell and taste. Footnote 1 Information theorists such as Zimmerman ( 1989 ) arrived at a similar hierarchy, albeit with a somewhat different weighting for each of the five main senses. In particular, Zimmermann estimated a channel capacity (in bits/s) of 10 7 for vision, 10 6 for touch, 10 5 for hearing and olfaction, and 10 3 for taste (gustation).

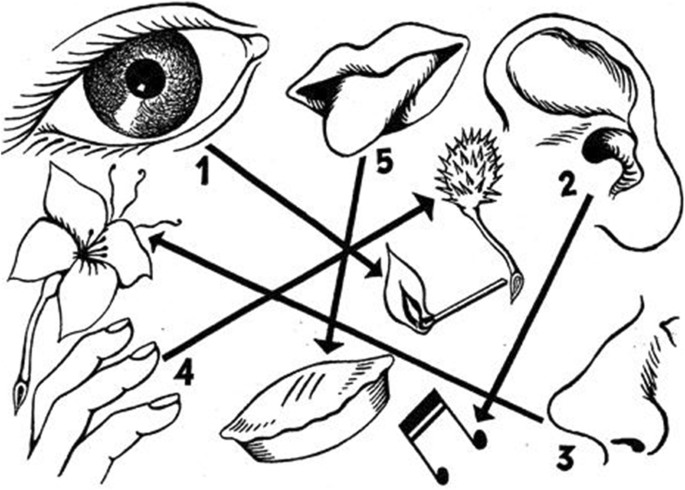

Figure 1 schematically illustrates the hierarchy of attentional capture by each of the senses as envisioned by Morton Heilig, the inventor of the Sensorama, the world’s first multisensory virtual reality apparatus (Heilig, 1962 ), when writing about the multisensory future of cinema in an article first published in 1955 (see Heilig, 1992 ). Nevertheless, while commentators from many different disciplines would seem to agree on vision’s current pre-eminence, one cannot help but wonder what has been lost as a result of the visual dominance that one sees wherever one looks in the world of architecture (“see” and “look” being especially apposite terms here).

Heilig ( 1992 ) ranked the order in which he believed our attention to be captured by the various senses. According to Heilig’s rankings: vision, 70%; audition, 20%; olfaction, 5%; touch, 4%; and taste, 1%. Does the same hierarchy (and weighting) apply to our appreciation of architecture, one might wonder? And is attentional capture the most relevant metric anyway?

While the hegemony of the visual (see Levin, 1993 ) is a phenomenon that appears across most aspects of our daily lives, the very ubiquity of this phenomenon certainly does not mean that the dominance of the visual should not be questioned (e.g., Dunn, 2017 ; Hutmacher, 2019 ). For, as Finnish architect and theoretician Pallasmaa ( 2011 , p. 595) notes: “Spaces, places, and buildings are undoubtedly encountered as multisensory lived experiences. Instead of registering architecture merely as visual images, we scan our settings by the ears, skin, nose, and tongue.” Elsewhere, he writes that: “Architecture is the art of reconciliation between ourselves and the world, and this mediation takes place through the senses” (Pallasmaa, 1996 , p. 50; see also Böhme, 2013 ). We will return later to question the visual dominance account, highlighting how our experience of space, as of anything else, is much more multisensory than most people realize.

Review outline

While architectural practice has traditionally been dominated by the eye/sight, a growing number of architects and designers have, in recent decades, started to consider the role played by the other senses, namely sound, touch (including proprioception, kinesthesis, and the vestibular sense), smell, and, on rare occasions, even taste. It is, then, clearly important that we move beyond the merely visual (not to mention modular) focus in architecture that has been identified in the writings of Juhani Pallasmaa and others, to consider the contribution that is made by each of the other senses (e.g., Eberhard, 2007 ; Malnar & Vodvarka, 2004 ). Reviewing this literature constitutes the subject matter of the next section. However, beyond that, it is also crucial to consider the ways in which the senses interact too. As will be stressed later, to date there has been relatively little recognition of the growing understanding of the multisensory nature of the human mind that has emerged from the field of cognitive neuroscience research in recent decades (e.g., Calvert, Spence, & Stein, 2004 ; Stein, 2012 ).

The principal aim of this review is therefore to provide a summary of the role of the human senses in architectural design practice, both when considered individually and, more importantly, when the senses are studied collectively. For it is only by recognizing the fundamentally multisensory nature of perception that one can really hope to explain a number of surprising crossmodal environmental or atmospheric interactions, such as between lighting colour and thermal comfort (Spence, 2020a ) or between sound and the perceived safety of public spaces (Sayin, Krishna, Ardelet, Decré, & Goudey, 2015 ), that have been reported in recent years.

At the same time, however, this review also highlights how the contemporary focus on synaesthetic design in architecture (see Pérez-Gómez, 2016 ) needs to be reframed in terms of the crossmodal correspondences (see Spence, 2011 , for a review), at least if the most is to be made of multisensory interactions and synergies that affect us all. Later, I want to highlight how accounts of multisensory interactions in architecture in terms of synaesthesia tend to confuse matters, rather than to clarify them. Accounting for our growing understanding of crossmodal interactions (specifically the emerging field of crossmodal correspondences research) and multisensory integration will help to explain how it is that our senses conjointly contribute to delivering our multisensory (and not just visual) experience of space. One other important issue that will be discussed later is the role played by our awareness of the multisensory atmosphere of the indoor environments in which we spend so much of our time.

Looking to the future, the hope is that architectural design practice will increasingly incorporate our growing understanding of the human senses, and how they influence one another. Such a multisensory approach will hopefully lead to the development of buildings and urban spaces that do a better job of promoting our social, cognitive, and emotional development, rather than hindering it, as has too often been the case previously. Before going any further, though, it is worth highlighting a number of the negative outcomes for our well-being that have been linked to the sensory aspects of the environments in which we spend so much of our time.

Negative health consequences of neglecting multisensory stimulation

It has been suggested that the rise in sick building syndrome (SBS) in recent decades (Love, 2018 ) can be put down to neglect of the olfactory aspect of the interior environments where city dwellers have been estimated to spend 95% of their lives (e.g., Ott & Roberts, 1998 ; Velux YouGov Report, 2018 ; Wargocki, 2001 ). Indeed, as of 2010, more people around the globe lived in cities than lived in rural areas (see UN-Habitat, 2010 and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2018 ). One might also be tempted to ask what responsibility, if any, architects bear for the high incidence of seasonal affective disorder (SAD) that has been documented in northern latitudes (Cox, 2017 ; Heerwagen, 1990 ; Rosenthal, 2019 ; Rosenthal et al., 1984 ). To give a sense of the problem of “light hunger” (as Heerwagen, 1990 , refers to it), Terman ( 1989 ) claimed that as many as 2 million people in Manhattan alone experience seasonal affective and behavioural changes severe enough to require some form of additional light stimulation during the winter months.

According to Pallasmaa ( 1994 , p. 34), Luis Barragán, the self-taught Mexican architect famed for his geometric use of bright colour (Gregory, 2016 ) felt that most contemporary houses would be more pleasant with only half their window surface. However, while such a suggestion might well be appropriate in Mexico, where Barragán’s work is to be found, many of us (especially those living in northern latitudes in the dark winter months) need as much natural light as we can obtain to maintain our psychological well-being. That said, Barragán is not alone in his appreciation of darkness and shadow. Some years ago, Japanese writer Junichirō Tanizaki also praised the aesthetic appeal of shadow and darkness in the native architecture of his home country in his extended essay on aesthetics, In praise of shadows (Tanizaki, 2001 ).

One of the problems with the extensive use of windows in northern climates is related to poor heat retention, an issue that is becoming all the more prominent in the era of sustainable design and global warming. One solution to this particular problem that has been put forward by a number of technology-minded researchers is simply to replace windows by the use of large screens that relay a view of nature for those who, for whatever reason, have to work in windowless offices (Kahn Jr. et al., 2008 ). However, the limited research that has been conducted on this topic to date suggests that the beneficial effects of being seated near to the window in an office building cannot easily be captured by seating workers next to such video-screens instead.

Similarly, the failure to fully consider the auditory aspects of architectural design may help to explain some part of the global health crisis associated with noise pollution interfering with our sleep, health, and well-being (Owen, 2019 ). The neglect of architecture’s fundamental role in helping to maintain our well-being is a central theme in Pérez-Gómez’s ( 2016 ) influential book Attunement: Architectural meaning after the crisis of modern science. Pérez-Gómez is the director of the History and Theory of Architecture Program at McGill University in Canada. Along similar lines, geographer J. Douglas Porteous had already noted some years earlier that: “Notwithstanding the holistic nature of environmental experience, few researchers have attempted to interpret it in a very holistic [or multisensory] manner.” (Porteous, 1990 , p. 201). Finally, here, it is perhaps also worth noting that there are even some researchers who have wanted to make a connection between the global obesity crisis and the obesogenic environments that so many of us inhabit (Lieberman, 2006 ). The poor diet of multisensory stimulation that we experience living a primary indoor life has also been linked to the growing sleep crisis apparently facing so many people in society today (Walker, 2018 ).

Designing for the modular mind

Researchers working in the field of environmental psychology have long stressed the impact that the sensory features of the built environment have on us (e.g., Mehrabian & Russell, 1974 , for an influential early volume detailing this approach). Indeed, many years ago, the famous modernist Swiss architect Le Corbusier ( 1948 ) made the intriguing suggestion that architectural forms “work physiologically upon our senses.” Inspired by early work with the semantic differential technique, researchers would often attempt to assess the approach-avoidance, active-passive, and dominant-submissive qualities of a building or urban space. This approach was based on the pleasure, arousal, and dominance (PAD) model that has long been dominant in the field. However, it is important to stress that in much of their research, the environmental psychologists took a separate sense-by-sense approach (e.g., Zardini, 2005 ).

The majority of researchers have tended to focus their empirical investigations on studying the impact of changing the stimulation presented to just one sense at a time. More often than not, in fact, they would focus on a single sensory attribute, such as, for example, investigating the consequences of changing the colour (hue) of the lighting or walls (e.g., Bellizzi, et al., 1983 ; Bellizzi & Hite, 1992 ; Costa, Frumento, Nese, & Predieri, 2018 ; Crowley, 1993 ), or else just modulating the brightness of the ambient lighting (e.g., Gal, Wheeler, & Shiv, 2007 ; Xu & LaBroo, 2014 ). Such a unisensory (and, in some cases, unidimensional) approach undoubtedly makes sense inasmuch as it may help to simplify the problem of studying how design affects us (Malnar & Vodvarka, 2004 ). What is more, such an approach is also entirely in tune with the modular approach to mind that was so popular in the fields of psychology and cognitive neuroscience in the closing decades of the twentieth century (e.g., Barlow & Mollon, 1982 ; Fodor, 1983 ). At the same time, however, it can be argued that this sense-by-sense approach neglects the fundamentally multisensory nature of mind, and the many interactions that have been shown to take place between the senses.

The visually dominant approach to research in the field of environmental psychology also means that far less attention has been given over to studying the impact of the auditory (e.g., Blesser & Salter, 2007 ; Kang et al., 2016 ; Schafer, 1977 ; Southworth, 1969 ; Thompson, 1999 ), tactile, somatosensory or embodied (e.g., Heschong, 1979 ; Pallasmaa, 1996 ; Pérez-Gómez, 2016 ), or even the olfactory qualities of the built environment (e.g., Bucknell, 2018 ; Drobnick, 2002 , 2005 ; Henshaw, McLean, Medway, Perkins, & Warnaby, 2018 ) than on the impact of the visual. Furthermore, until very recently, little consideration has been given by the environmental psychologists to the question of how the senses interact, one with another, in terms of their influence on an individual. This neglect is particularly striking given that the natural environment, the built environment, and the atmosphere of a space are nothing if not multisensory (e.g., Bille & Sørensen, 2018 ). In fact, it is no exaggeration to say that our response to the environments, in which we find ourselves, be they built or natural, is always going to be the result of the combined influence of all the senses that are being stimulated, no matter whether we are aware of their influence or not (this is a point to which we will return later).

Given that those of us living in urban environments, which as we have seen is now the majority of us, spend more than 95% of our lives indoors (Ott & Roberts, 1998 ), architects would therefore seem to bear at least some responsibility for ensuring that the multisensory attributes of the built environment work together to deliver an experience that positively stimulates the senses, and, by so doing, facilitates our well-being, rather than hinders it (see also Pérez-Gómez, 2016 , on this theme). Crucially, however, a growing body of cognitive neuroscience research now demonstrates that while we are often unaware of, or at least pay little conscious attention to the subtle sensory cues that may be conveyed by a space (e.g., Forster & Spence, 2018 ), that certainly does not mean that they do not affect us. In fact, the sensory qualities or attributes of the environment have long been known to affect our health and well-being in environments as diverse as the hospital and the home, and from the office to the gym (e.g., Spence, 2002 , 2003 , 2021 ; Spence & Keller, 2019 ). What is more, according to the research that has been published to date, environmental multisensory stimulation can potentially affect us at the social, emotional, and cognitive levels.

It can be argued, therefore, that we all need to pay rather more attention to our senses and the way in which they are being stimulated than we do at present (see also Pérez-Gómez, 2016 , on this theme). You can call it a mindful approach to the senses (Kabat-Zinn, 2005 ), Footnote 2 though my preferred terminology, coined in an industry report published almost 20 years ago, is “sensism” (see Spence, 2002 ). Sensism provides a key to greater well-being by considering the senses holistically, as well as how they interact, and incorporating that understanding into our everyday lives. The approach also builds on the growing evidence of the nature effect (Williams, 2017 ) and the fact that we appear to benefit from, not to mention actually desire, the kinds of environments in which our species evolved. As support for the latter claim, consider only how it has recently emerged that most people set their central heating to a fairly uniform 17–23 °C, meaning that the average indoor temperature and humidity most closely matches the mild outdoor conditions of west central Kenya or the Ethiopian highlands (i.e., the place where human life is first thought to have evolved), better than anywhere else (Just, Nichols, & Dunn, 2019 ; Whipple, 2019 ).

Architectural design for each of the senses

It is certainly not the case that architects have uniformly ignored the non-visual senses (e.g., see Howes, 2005 , 2014 ; McLuhan, 1961 ; Pallasmaa, 1994 , 2011 ; Ragavendira, 2017 ). For instance, in their 2004 book on Sensory design , Malnar and Vodvarka talk about challenging visual dominance in architectural design practice by giving a more equal weighting to all of the senses (Malnar & Vodvarka, 2004 ; see also Mau, 2019 ). Meanwhile, Howes ( 2014 ) writes of the sensory monotony of the bungalow-filled suburbs and of the corporeal experience of skyscrapers as their presence looms up before those on the sidewalk below. At the same time, however, there is also a sense in which it is the gaze of the inhabitants of those tall buildings who are offered the view that is prioritized over the other senses.

However, very often the approach as, in fact, evidenced by Malnar and Vodvarka ( 2004 ) has been to work one sense at a time. Until recently, that is, one finds exactly the same kind of sense-by-sense (or unisensory) approach in the worlds of interior design (Bailly Dunne & Sears, 1998 ), advertising (Lucas & Britt, 1950 ), marketing (Hultén, Broweus, & Dijk, 2009 ; Krishna, 2013 ; Lindstrom, 2005 ), and atmospherics (see Bille & Sørensen, 2018 , on architectural atmospherics; and Kotler, 1974 , on the theme of store atmospherics). Recently, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of the non-visual senses to various fields of design (Haverkamp, 2014 ; Lupton & Lipps, 2018 ; Malnar & Vodvarka, 2004 ). As yet, however, there has not been sufficient recognition of the extent to which the senses interact. As Williams ( 1980 , p. 5) noted some 40 years ago: “Aside from meeting common standards of performance, architects do little creatively with acoustical, thermal, olfactory, and tactile sensory responses.” As we will see later, it is not clear that much has changed since.

The look of architecture

There are a number of ways in which visual perception science can be linked to architectural design practice. For instance, think only of the tricks played on the eyes by the trapezoidal balconies on the famous The Future apartment building in Manhattan (see Fig. 2 ). They appear to slant downward when viewed from one side while appearing to slope upward instead, if viewed from the other. The causes of such a visual illusion can, at the very least, be meaningfully explained in terms of visual perception research (Bruno & Pavani, 2018 ).

The Future apartment building at 200 East 32nd Street in Manhattan. Architectural design that appeals primarily to the eye? [Credit Jeffrey Zeldman, and reprinted under Creative Commons agreement]

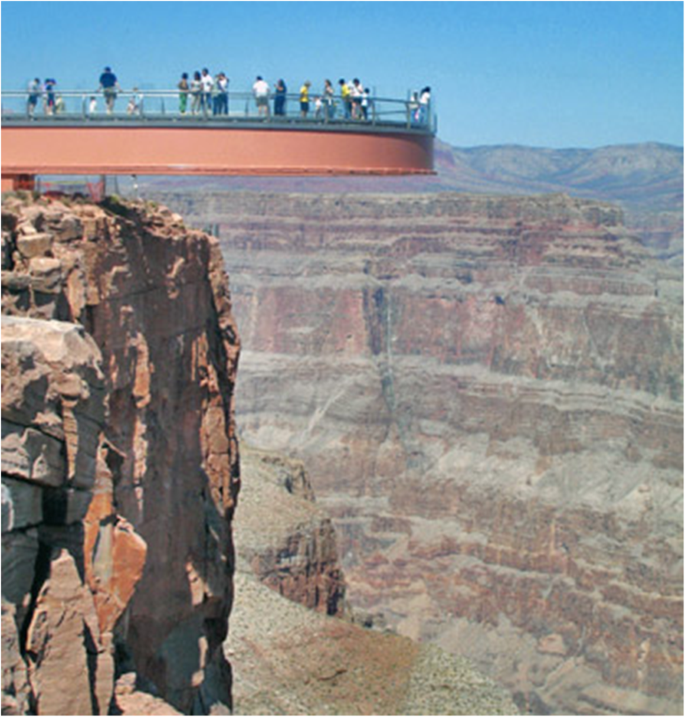

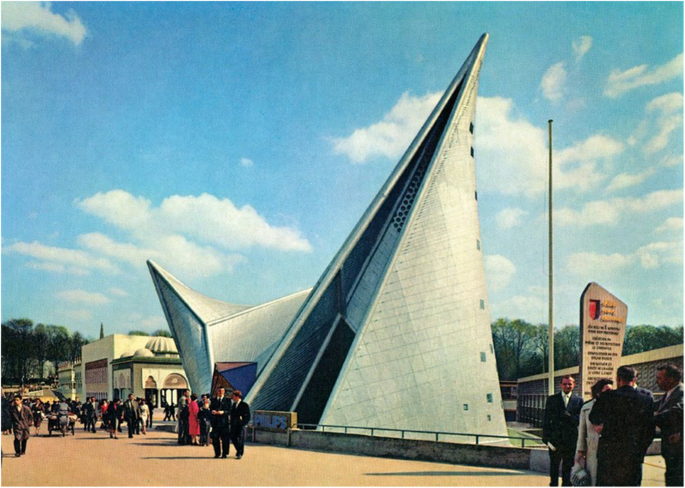

Cognitive neuroscientists have recently demonstrated that we have an innate preference for visual curvature, be it in internal space (Vartanian et al., 2013 ), or for the furniture that is found within that space (Dazkir & Read, 2012 ; see also Lee, 2018 ; Thömmes & Hübner, 2018 ). We typically rate curvilinear forms as being more approachable than rectilinear ones (see Fig. 3 ). Angular forms, especially when pointing downward/toward us, may well be perceived as threatening, and hence are somewhat more likely to trigger an avoidance response (Salgado-Montejo, Salgado, Alvarado, & Spence, 2017 ). As Ingrid Lee, former design director at IDEO New York put it in her book, Joyful: The surprising power of ordinary things to create extraordinary happiness : “Angular objects, even if they’re not directly in your path as you move through your home, have an unconscious effect on your emotions. They may look chic and sophisticated, but they inhibit our playful impulses. Round shapes do just the opposite. A circular or elliptical coffee table changes a living room from a space for sedate, restrained interaction to a lively center for conversation and impromptu games” (Lee, 2018 , p. 142). One might consider here whether Lee’s comments can be scaled up to describe how we move through the city. Does the visually striking building shown in Fig. 4 , for instance, really promote joyfulness and a carefree travel through the urban environment. It seems doubtful, given the evidence suggesting that viewing angular shapes, even briefly, has been shown to trigger a fear response in the amygdala, the part of the brain that is involved in emotion (e.g., LeDoux, 2003 ). Meanwhile, Liu, Bogicevic, and Mattila ( 2018 ) have noted how the round versus angular nature of the servicescape also influences the consumer response in service encounters.

A selection of the interiors shown to participants in a neuroimaging study designed to assess viewers’ approach-avoidance motivation in response to curvilinear vs. rectilinear spaces. [High/Low roof; Open/Enclosed space.] [Figure reprinted with permission from Vartanian et al., 2013 ]

Montcalm Shoreditch Signature Tower Hotel, 151–157 City Road, London, completed 2015 by SMC Alsop Architects. What is lost when architectural design focuses on eye appeal? [Figure copyright Ian Ritchie, RA]

The height of the ceiling has also been shown to exert an influence over our approach-avoidance responses, and perhaps even our style of thinking (Baird, Cassidy, & Kurr, 1978 ; Meyers-Levy & Zhu, 2007 ; Vartanian et al., 2015 ). However, here it should also be born in mind that the visual perception of space is significantly influenced by colour and lighting (Lam, 1992 ; Manav, Kutlu, & Küçükdoğu, 2010 ; Oberfeld, Hecht, & Gamer, 2010 ; von Castell, Hecht, & Oberfeld, 2018 ). Given many such psychological observations, it should perhaps come as no surprise to find that links between cognitive neuroscience and architecture have grown rapidly in recent years (Choo, Nasar, Nikrahei, & Walther, 2017 ; Eberhard, 2007 ; Mallgrave, 2011 ; Robinson & Pallasmaa, 2015 ). At the same time, however, it is also worth remembering that it has primarily been people’s response to examples or styles of architecture that have been presented visually (via a monitor), with the participant lying horizontal, that have been studied to date, given the confines of the brain-scanning environment (though see also Papale, Chiesi, Rampinini, Pietrini, & Ricciardi, 2016 ). Footnote 3

At the same time, however, it is important to realize that it is not just our visual cortex that responds to architecture. For, as Frances Anderton writes in The Architectural Review : “We appreciate a place not just by its impact on our visual cortex but by the way in which it sounds, it feels and smells. Some of these sensual experiences elide, for instance our full understanding of wood is often achieved by a perception of its smell, its texture (which can be appreciated by both looking and feeling) and by the way in which it modulates the acoustics of the space.” (Anderton, 1991 , p. 27). The multisensory appreciation of quality here linking to a growing body of research on multisensory shitsukan perception - shitsukan , the Japanese word for “a sense of material quality” or “material perception” (see Fujisaki, 2020 ; Komatsu & Goda, 2018 ; Spence, 2020b ). The following sub-sections summarize some of the key findings on how the non-visual sensory attributes of the built and urban environment affect us, when considered individually.

The sound of space: are you listening?

What a space sounds like is undoubtedly important (Bavister, Lawrence, & Gage, 2018 ; McLuhan, 1961 ; Porteous & Mastin, 1985 ; Thompson, 1999 ). Sounds can, after all, provide subtle cues as to the identity or proportions of a space, even hinting at its function (Blesser & Salter, 2007 ; Eberhard, 2007 ; Robart & Rosenblum, 2005 ). As Pallasmaa ( 1994 , p. 31) notes: “Every building or space has its characteristic sound of intimacy or monumentality, rejection or invitation, hospitality or hostility.” However, more often than not, discussion around sound and architectural design tends to revolve around how best to avoid, or minimize, unwanted noise (see Owen, 2019 , on growing concerns regarding the latter). Indeed, as J. Douglas Porteous notes: “with the rapid urbanization of the world’s population, far more attention is being given to noise than to environmental sound … Research has concentrated almost entirely upon a single aspect of sound, the concept of noise or ‘unwanted sound.’” (Porteous, 1990 , p. 48). Some years earlier, Schafer ( 1977 , p. 222) had made much the same point when he wrote that: “The modern architect is designing for the deaf …. The study of sound enters modern architecture schools only as sound reduction, isolation and absorption.” The fact that year-on-year, noise continues to be one of the top complaints from restaurant patrons, perhaps tells us all we need to know about how successful designers have been in this regard (see Spence, 2014 , for a review; Wagner, 2018 ).

There is also an emerging story here regarding the deleterious effects of loud background noise, and the often-beneficial effects of music and soundscapes, on the recovery of patients in the hospital/healthcare setting (see Spence & Keller, 2019 , for a review). Meanwhile, one of the main complaints from those office workers forced to move into one of the open plan offices that have become so popular (amongst employers, if not employees) in recent years (see ‘Redesigning the corporate office’, 2019 ) is around noise distraction (Borzykowski, 2017 ; Burkus, 2016 ; Evans & Johnson, 2000 ). Footnote 4 Once again, one might want to ask what responsibility architects bear. Experimental evidence documenting the deleterious effect of open-plan working has been reported by a number of researchers (e.g., Bernstein & Turban, 2018 ; De Croon, Sluiter, Kuijer, & Frings-Dresen, 2005 ; Otterbring, Pareigis, Wästlund, Makrygiannis, & Lindström, 2018 ).

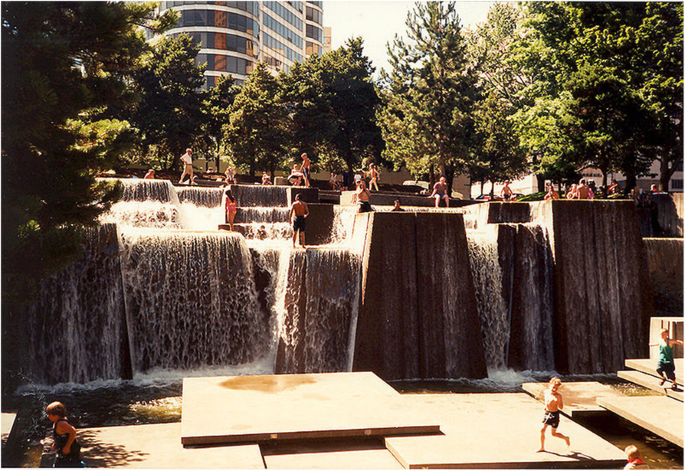

There is research ongoing in a number of countries to investigate the use of nature sounds, such as, for example, the sound of running water, to help mask other people’s distracting conversations (Hongisto, Varjo, Oliva, Haapakangas, & Benway, 2017 ). Intriguingly, however, it turns out that people’s beliefs about the source of masking sounds, especially in the case of ambiguous noise, can sometimes influence how much relief they provide (Haga, Halin, Holmgren, & Sörqvist, 2016 ). So, for instance, Haga and her colleagues played the same ambiguous pink noise with interspersed white noise to three groups of office-workers. To one control group, the experimenters said nothing, a second group of participants was told that they could hear industrial machinery noise, while a third group was told that they were listening to nature sounds, based on a waterfall, instead. Intriguingly, subjective restoration was significantly higher amongst those who thought that they were listening to the nature sounds than in those who thought that they were listening to industrial noise instead. As might have been expected, the results of the control group, fell somewhere in between.

Paley Park in New York has often been put forward as a particularly elegant solution to the problem of negating unwanted traffic noise in the context of urban design (e.g., Carroll, 1967 ; Prochnik, 2009 ). In 1967, the empty lot resulting from the demolition of the Stork Club on 53rd Street was transformed into a small public park (a so-called pocket park). The space was developed by Zion and Breen. In this case, the acoustic space, think only of the sounds, or better said noise, of the city, is effectively masked by the presence of a waterfall at the far end of the lot (see Fig. 5 ). What is more, the free-standing chairs allow the visitor to move closer to the waterfall should they feel the need to drown out a little more of the urban noise. The greenery growing thickly along the side walls also likely helps to absorb the noise of the city.

Paley Park, New York, by Zion and Breen in 1967. [Credit Jim Henderson, and reprinted under Creative Commons agreement]

Music plays an important role in our experience of the built environment - think here only of the Muzak of decades gone by (Lanza, 2004 ). This is as true of the guest’s hotel experience (e.g., when entering the lobby) as it is elsewhere (e.g., in a shopping centre or bar, say). Footnote 5 The sound that greets customers in the lobby is apparently very important to Ian Schrager, the Brooklyn-born entrepreneur who created fabled nightclub Studio 54 in New York. In recent years, he has been working with Marriott to launch The EDITION hotels in a number of major cities, including London and New York. Music plays a key role in the Schrager experience. As the entrepreneur puts it: “The sound of a hotel lobby is often dictated by monotonous, vapid lounge muzak – a zombie-like drone of new jazz and polite house, with the sole purpose of whiling away the waiting time between check-in and check-out.” As might have been expected, the music in the lobbies of The EDITION hotels is carefully curated (Eriksen, 2014 , p. 27). However, the thumping noise of the music from the nightclub/bar that is often also an integral part of the experience offered by these hip venues means that meticulous architectural design is also required in order to limit the spread of unwanted noise through the rest of the building (e.g., so as not to disturb the sleep of those who may be resting in the rooms upstairs). Note here that there are also some increasingly sophisticated solutions - including sound-absorbing panels, as well as active noise cancellation systems - to dampen unwanted sound in open spaces such as restaurants and offices (Clynes, 2012 ).

Designing for “the eyes of the skin”

The tactile element of architecture is often ignored. In fact, very often, the first point of physical contact with a building typically occurs when we enter or leave. Or, as Pallasmaa ( 1994 , p. 33) once evocatively put it: “The door handle is the handshake of the building”. However, once inside a building, it is worth remembering that we will also typically make contact with flooring (Tonetto, Klanovicz, & Spence, 2014 ), hand rails (Spence, 2020d ), elevator buttons, furniture, and the like (though this is, of course, likely to change somewhat in the era of pandemia). As Richard Sennett, author of Flesh and Stone, laments in his critical take on the sensory order of modernity: “sensory deprivation which seems to curse most modern buildings; the dullness, the monotony, and the tactile sterility which afflicts the urban environment” (Sennett, 1994 , p. 15). The absence of tactile interest is also something that Witold Rybczynski author of The Look of Architecture acknowledges when writing that: “Although architecture is often defined in terms of abstractions such as space, light and volume, buildings are above all physical artifacts. The experience of architecture is palpable: the grain of wood, the veined surface of marble, the cold precision of steel, the textured pattern of brick.” (Rybczynski, 2001 , p. 89). Notice here how Rybczynski mentions both texture and temperature, two of the key attributes of tactile sensation(see also Henderson, 1939 ). Temperature change, and change in the flooring material (tatami matting or cedarwood), is also something that the Tom museum for the blind in Tokyo also plays with deliberately (Classen, 1998 , p. 150; Vorreiter, 1989 ; Wagner, 1989 ). There is also a braille poen on the knob of the exit door too.

The careful use of material can evoke tactility as the viewer (or occupant) imagines or mentally simulates what it would feel like to reach out and touch or caress an intriguing surface (Sigsworth, 2019 ; see also Lupton, 2002 ). Juhani Pallasmaa, who has perhaps written more than anyone else on the theme of the tactile, or haptic in architecture, writes that “Natural materials - stone, brick and wood - allow the gaze to penetrate their surfaces and they enable us to become convinced of the veracity of matter … But the materials of today - sheets of glass, enamelled metal and synthetic materials - present their unyielding surfaces to the eye without conveying anything of their material essence or age.” (Pallasmaa, 1994 , p. 29).

Lisa Heschong, architect, and partner of architectural research firm Heschong Mahone Group, has written extensively on the theme of thermal (as opposed to textural) aspects of architectural design in her book Thermal Delight in Architecture (Heschong, 1979 ) . There, she points to examples such as the hearth, the sauna, and Roman and Japanese baths as archetypes of thermal delight about which rituals have developed, the shared experience reinforcing social bonds of affection and ceremony (see also Lupton, 2002 ; Papale et al., 2016 ). At this point, one might also want to mention the much-admired Therme Vals Spa by Peter Zumthor, in Switzerland with their use of different temperatures of both water and touchable surfaces (Ryan, 1997 , though see also Mairs, 2017 ). The tactile element is, in other words, fundamental to the total (multisensory) experience of architectural design. This is true no matter whether the materiality is touched directly or not (i.e., merely seen, inferred, or imagined). So, for example, here one might only think about how looking at a cheap fake marble or wood veneer can make one feel, to realize that touch in often not required to assess material quality, or the lack thereof (see also Karana, 2010 ).

An architecture of the chemical senses

Talking of an architecture of scent, or of taste (these two of the so-called chemical senses), might seem like a step too far. That said, one does come across titles such as Eating Architecture (Horwitz & Singley, 2004 ) and An Architecture of Smell (McCarthy, 1996 ; see also Barbara & Perliss, 2006 ). Footnote 6 Unfortunately, however, all too often, consideration of the olfactory in architectural design practice has focused on the elimination of negative odours. When thinking about the mundane experience of odours in buildings, what immediately comes to mind includes the smell of wood (i.e., building materials), dust, mould, cleaning products, and flowers. As Eberhard ( 2007 , p. 47) puts it: “We all have our favorite smells in a building, as well as ones that are considered noxious. A cedar closet in the bedroom is an easy example of a good smell. The terrible smell of a house that was ravaged by fire or floods is seared in the memory of those who have endured one of these disasters.” This is perhaps no coincidence, given that it tends to be the bad odours, rather than the neutral or positive ones, that have generally proved most effective in immersing us in an experience (Baus & Bouchard, 2017 ; see also Aggleton & Waskett, 1999 ). Research by Schifferstein, Talke, and Oudshoorn ( 2011 ) investigated whether the nightlife experience could be enhanced by the use of pleasant fragrance to mask the stale odour after the indoor smoking ban was introduced a few years ago. Once again, notice how the focus here is on the elimination of the negative stale odours rather than necessarily the introduction of the positive (the latter merely being introduced in order to mask the former).

Jim Drohnik captures the idea of olfactory absence when talking about not just the “white cube” mentality but the “anosmic cube” (Drobnick, 2005 ). The former phrase was famously coined by O’Doherty ( 1999 , 2009 ) in order to describe the then-popular practice of displaying art in gallery spaces that were devoid of colour or any other form of visual distraction. Footnote 7 Some years later, Jim Drobnik introduced the latter phrase in order to highlight the fact that too many spaces are seemingly deliberately designed to have no smell, nor to leave any lasting olfactory trace, either. Footnote 8 And yet, at the same time, it is clear that odour of a space can be incredibly evocative too, as anecdotally noted by Pallasmaa ( 1994 , p. 32) in the following quote: “The strongest memory of a space is often its odor; I cannot remember the appearance of the door to my grandfather’s farm-house from my early childhood, but I do remember the resistance of its weight, the patina of its wood surface scarred by a half century of use, and I recall especially the scent of home that hit my face as an invisible wall behind the door.” And thinking back to my memories of visiting my own grandfather, long since deceased, on his fairground wagon in Bradford, it was undoubtedly the intense smell of “derv” (English slang for diesel-engine road vehicle), the liquid diesel oil that was used for trucks at the time, that I can still remember better than anything else. The residents of buildings tend to adapt to the positive and neutral smells in the buildings we inhabit. This is evidenced by the fact that we are typically only aware of the smell of our own home, what some call building odour, or BO for short, when we return after a long trip away (Dalton & Wysocki, 1996 ; McCooey, 2008 ).

Sick building syndrome and the problem of poor olfactory design

Improving indoor air quality might well also provide an effective means of helping to alleviate some of the symptoms of sick building syndrome (SBS) that were mentioned earlier (Guieysse et al., 2008 ). It is certainly striking how many large outbreaks of this still-mysterious condition reported in the 1980s were linked to the presence of an unfamiliar smell in closed office buildings with little natural ventilation (Wargocki, Wyon, Baik, Clausen, & Fanger, 1999 ; Wargocki, Wyon, Sundell, Clausen, & Fanger, 2000 ). For instance, in June 1986, more that 12% of the workforce of 2500 people working at the Harry S. Truman State Office Building in Missouri came down with the symptoms of SBS over a 3-day period (Donnell Jr. et al., 1989 ). The symptoms presented by some of the workers (including dizziness and difficulty in breathing) were so severe they had to be rushed to the local hospital for emergency treatment. And while a thorough examination of the building subsequently failed to reveal the presence of any particular toxic airborne pollutants that might have been responsible for the outbreak, in the majority of cases, it turned out that the symptoms of SBS were preceded by the perception of unusual odours and inadequate airflow in the building.

According to Donnell Jr. et al. ( 1989 ), these complaints of odours may well have heightened the perception of poor air quality by some employees in the building. This, in turn, may have led to an epidemic anxiety state resulting in the SBS outbreak (Faust & Brilliant, 1981 ). In fact, workers suffering from SBS were more than twice as likely to have noticed a particular odour in the work area before the onset of their symptoms than those who were working in the same building who were unaffected by the outbreak. Footnote 9 At the same time, however, it should also be borne in mind that our tendency to focus on what we see and hear means that we often exhibit olfactory anosmia to ambient scents (Forster & Spence, 2018 ).

To give a sense of the potential scale of the problem, Woods ( 1989 ) estimated that 30–70 million people in the USA alone are exposed to offices that manifest SBS. As such, anything (and everything) that can be done to reduce the symptoms associated with this reaction to the indoor environment (Finnegan, Pickering, & Burge, 1984 ) will likely have a beneficial effect on the health and well-being of many people. At the same time, however, it is perhaps also worth bearing in mind here that the incidence of SBS would seem to have declined in recent years (though see also Joshi, 2008 ; Magnavita, 2015 ; Redlich, Sparer, & Cullen, 1997 ), perhaps suggesting that building design/ventilation has improved as a result of the earlier outbreaks. Footnote 10 That said, it is perhaps also worth noting that there continues to be some uncertainty as to whether the very real symptoms of SBS should be attributed to airborne pollutants, or may instead be better understood as a psychosomatic response to a particular environmental atmosphere (see Fletcher, 2005 and Love, 2018 ). What is more, there has been a move by some researchers to talk in terms of the less pejorative-sounding building-related symptoms (BRS) instead (Niemelä, Seppänen, Korhonen, & Reijula, 2006 ). One more psychological factor that may be relevant here concerns the feeling of a lack of control over one’s multisensory environment that many of those working in ventilated buildings where the windows cannot be opened manually have may indeed play a role in the elicitation of SBS.

Scent and the city: designing fragrant spaces

There are, however, signs that the situation is slowly starting to change with regards to the emphasis placed on olfaction in both architectural and urban design practice. For instance, a number of commentators have noted, not to mention sometimes been puzzled by, the distinctive, yet unexplained, pleasant - and hence, one assumes, deliberately introduced - fragrances that some new constructions appear to have. Just take the case of the Barclays Center arena in Brooklyn, NY, home of the Brooklyn Nets, as a case in point. On its opening in 2013, various commentators in the press drew attention to the distinctive, if not immediately identifiable, scent that appeared to pervade the space, and which appeared to have been added deliberately - almost as if it were intended to be a signature scent for the space (e.g., Albrecht, 2013 ; Doll, 2013 ; Martinez, 2013 ). That said, the idea of fragrancing public spaces dates back at least as far as 1913. In that year, at the opening of the Marmorhaus cinema in Berlin, the fragrance of Marguerite Carré, a perfume by Bourjois, Paris, was deliberately (and innovatively, at least for the time) wafted through the auditorium (Berg-Ganschow & Jacobsen, 1987 ). Meanwhile, in what may well be a sign of things to come, synaesthetic perfumer Dawn Goldsworthy and her scent design company 12:29 recently made the press after apparently creating a bespoke scent for a new US$40 million apartment in Miami (Schroeder, 2018 ). What further opportunities might there be to design distinctive “signature” scents for spaces/buildings, one might ask (Henshaw et al., 2018 ; Jones, 2006 ; Trivedi, 2006 )?

Evidence that the olfactory element of design can be used to affect behaviour change positively includes, for example, the observation that people tend to engage in more cleaning behaviours when there is a hint of citrus in the air (De Lange, Debets, Ruitenburg, & Holland, 2012 ; Holland, Hendriks, & Aarts, 2005 ). In the future, it may not be too much of a stretch to imagine public spaces filled with aromatic flowers and blossoming trees, introduced with the aim of helping to discourage people from littering, and who knows, perhaps even reducing vandalism (see also Steinwald, Harding, & Piacentini, 2014 ). In terms of the cognitive mechanism underlying such crossmodal effects of scent on behaviour, the suggestion, at least in the citrus cleaning example just mentioned, is that smelling an ambient scent that we associate with clean and cleaning then activates, or primes, the associated concepts (Smeets & Dijksterhuis, 2014 ). Having been primed, the suggestion is thus that this makes it that bit more likely that we will engage in behaviours that are congruent or consistent with the primed concept (though see Doyen, Klein, Pichon, & Cleeremans, 2012 ).

Elsewhere, researchers have already demonstrated the beneficial effects that lavender, and other scents normally associated with aromatherapy, have on those who are exposed to them. So, for instance, the latter tend to show reduced stress, better sleep, and even enhanced recovery from illness (see Herz, 2009 ; Spence, 2003 , for reviews; though see also Haehner, Maass, Croy, & Hummel, 2017 ). According to one commentator writing in The New York Times: “While these findings have obvious implications for health care, the opportunities for architecture and urban planning are particularly intriguing. Designers are trained to focus mostly on the visual, but the science of design could significantly expand designers’ sensory palette. Call it medicinal urbanism.” (Hosey, 2013 ). Effects on people’s mood resulting from exposure to ambient scent have been reported in some by no means all studies (Glass & Heuberger, 2016 ; Glass, Lingg, & Heuberger, 2014 ; Haehner et al., 2017 ; Weber & Heuberger, 2008 ). It remains somewhat uncertain though whether the beneficial effects of aromatherapy scents can be explained by priming effects, based on associative learning, as in the case of the clean citrus scents mentioned above (see Herz, 2009 ), versus via a more direct (i.e., less cognitively mediated) physiological route (cf. Harada, Kashiwadani, Kanmura, & Kuwaki, 2018 ).

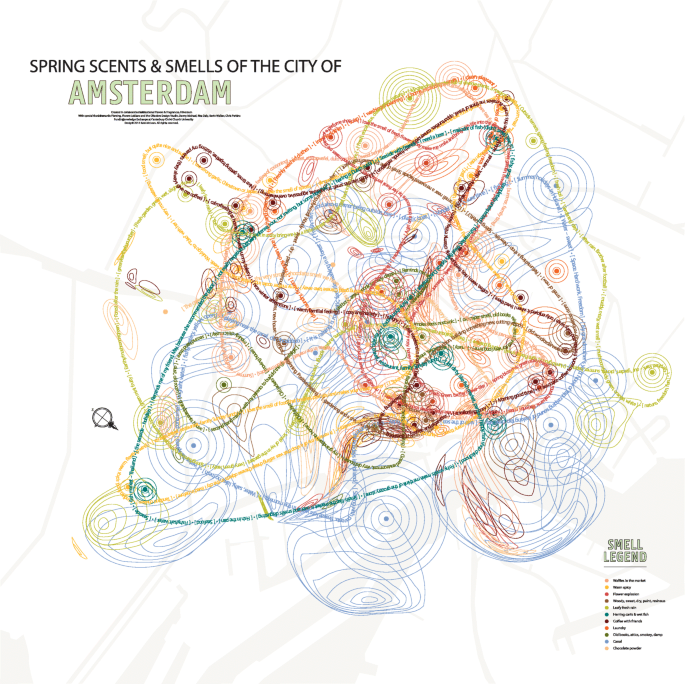

The olfactory scentscapes, and scent maps of cities, that have been discussed by various researchers (see Fig. 6 ) have also helped to draw people’s attention to the often rich olfactory landscapes offered by many urban spaces (e.g., https://sensorymaps.com/ ; Bucknell, 2018 ; Henshaw, 2014 ; Henshaw et al., 2018 ; Lipps, 2018 ; Lupton & Lipps, 2018 ; Margolies, 2006 ).

Scentscape of the city. Spring scents and smells of the city of Amsterdam by Kate McLean. [Credit “Spring Scents & Smells of the City of Amsterdam” © 2013-2014. Digital print. 2000 x 2000 mm. Courtesy of Kate McLean]

The notion of the healing garden has also seen something of a resurgence in recent years, and the benefits now, as historically, are likely to revolve, at least in part, around the healing, or restorative effect of the smell of flowers and plants (e.g., Pearson, 1991 ; see also Ottoson & Grahn, 2005 ). One building that is often mentioned in this regard, namely in terms of its olfactory design credentials, is the Silicon House by architects, SelgasCano, situated on the outskirts of Madrid ( https://www.architectmagazine.com/project-gallery/silicon-house-6143 ). This house is set in what has been described as “a garden of smells”, which emphasize the olfactory, while also stressing the tactile elements of the design. Hence, while the olfactory aspects of architectural design practice have long been ignored, there are at least signs of a revival of interest in stimulating this sense through both architectural and urban design practice.

Architectural taste

The British writer and artist Adrian Stokes once wrote of the “oral invitation of Veronese marble” (Stokes, 1978 , p. 316). And while I must admit that I have never felt the urge to lick a brick, Pallasmaa ( 1996 , p. 59) vividly recounts the urge that he once experienced to explore/connect with architecture using his tongue. He writes that: “Many years ago when visiting the DL James Residence in Carmel, California, designed by Charles and Henry Greene, I felt compelled to kneel and touch the delicately shining white marble threshold of the front door with my tongue. The sensuous materials and skilfully crafted details of Carlo Scarpa’s architecture as well as the sensuous colours of Luis Barragan’s houses frequently evoke oral experiences. Deliciously coloured surfaces of stucco lustro , a highly polished colour or wood surfaces also present themselves to the appreciation of the tongue.”

Perhaps aware of many readers’ presumed scepticism on the theme of the gustatory contribution to architecture, Footnote 11 Pallasmaa writes elsewhere that: “The suggestions that the sense of taste would have a role in the appreciation of architecture may sound preposterous. However, polished and coloured stone as well as colours in general, and finely crafted wood details, for instance, often evoke an awareness of mouth and taste. Carlo Scarpa’s architectural details frequently evoke sensation of taste.” (Pallasmaa, 2011 , p. 595). The suggestion here that “colours in general … often evoke … [a] taste” seemingly linking to the widespread literature on the crossmodal correspondences that have increasingly been documented between colour and basic tastes (see Spence et al., 2015 , for a review). However, rather than describing this in terms of architecture that one can taste, one might more fruitfully refer to the growing literature on crossmodal correspondences instead (see below for more on this theme).

When, in his book Architecture and the brain , Eberhard ( 2007 , p. 47) talks about what the sense of taste has to do with architecture, he suggests that: “You may not literally taste the materials in a building, but the design of a restaurant can have an impact on your ‘conditioned response’ to the taste of the food.” Environmental multisensory effects on tasting is undoubtedly an area that has grown markedly in interest in recent years (e.g., see Spence, 2020c , for a review). It is though worth noting that just as for the olfactory case, some atmospheric effects on tasting may be more cognitively-mediated (e.g., associated with the priming of notions of luxury/expense, or lack thereof) while others may be more direct, as when changing the colour (see Oberfeld, Hecht, Allendorf, & Wickelmaier, 2009 ; Spence, Velasco, & Knoeferle, 2014 ; Torrico et al., 2020 ) or brightness (Gal et al., 2007 ; Xu & LaBroo, 2014 ) of the ambient lighting changes taste/flavour perception.

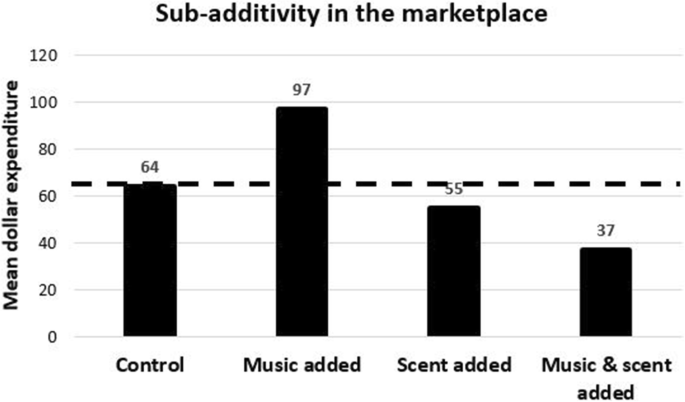

“An architecture of the seven senses”?