- IIT JEE Study Material

The Gas Laws

Introduction: what are the gas laws.

The gas laws are a group of laws that govern the behaviour of gases by providing relationships between the following:

- The volume occupied by the gas.

- The pressure exerted by a gas on the walls of its container.

- The absolute temperature of the gas.

- The amount of gaseous substance (or) the number of moles of gas.

Download Complete Chapter Notes of States of Matter Download Now

The gas laws were developed towards the end of the 18 th century by numerous scientists (after whom the individual laws are named). The five gas laws are listed below:

- Boyle’s Law: It provides a relationship between the pressure and the volume of a gas.

- Charles’s Law: It provides a relationship between the volume occupied by a gas and the absolute temperature.

- Gay-Lussac’s Law: It provides a relationship between the pressure exerted by a gas on the walls of its container and the absolute temperature associated with the gas.

- Avogadro’s Law: It provides a relationship between the volume occupied by a gas and the amount of gaseous substance.

- The Combined Gas Law (or the Ideal Gas Law): It can be obtained by combining the four laws listed above.

Under standard conditions, all gasses exhibit similar behaviour. The variations in their behaviours arise when the physical parameters associated with the gas, such as temperature, pressure, and volume, are altered. The gas laws basically describe the behaviour of gases and have been named after the scientists who discovered them.

We will look at all the gas laws below and also understand a few underlying topics.

Boyle’s Law

- Charle’s Law

Gay-Lussac Law

Avogadro’s law, combined gas law.

- Gas Law Table

- Gas Law Problems

- Applications of Gas Law

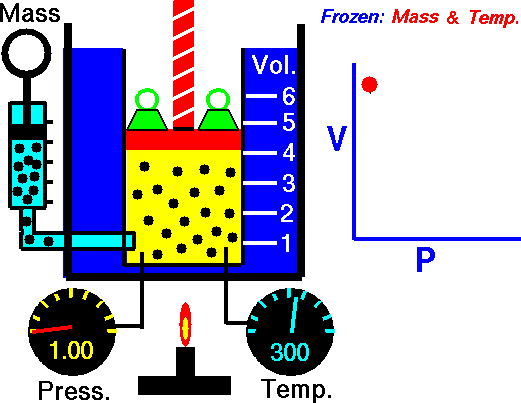

Boyle’s law gives the relationship between the pressure of a gas and the volume of the gas at a constant temperature. Basically, the volume of a gas is inversely proportional to the pressure of a gas at a constant temperature.

Boyle’s law equation is written as:

Where V is the volume of the gas, P is the pressure of the gas, and K 1 is the constant. Boyle’s Law can be used to determine the current pressure or volume of gas and can also be represented as,

P 1 V 1 = P 2 V 2

Problems Related to Boyle’s Law

An 18.10mL sample of gas is at 3.500 atm. What will be the volume if the pressure becomes 2.500 atm, with a fixed amount of gas and temperature?

By solving with the help of Boyle’s law equation

P 1 V 1 = P 2 V 2

V 2 = P 1 V 1 / P 2

V 2 = (18.10 * 3.500 atm)/2.500 atm

V 2 = 25.34 mL

Also Read: Behaviour of Gases

Charle’s Law

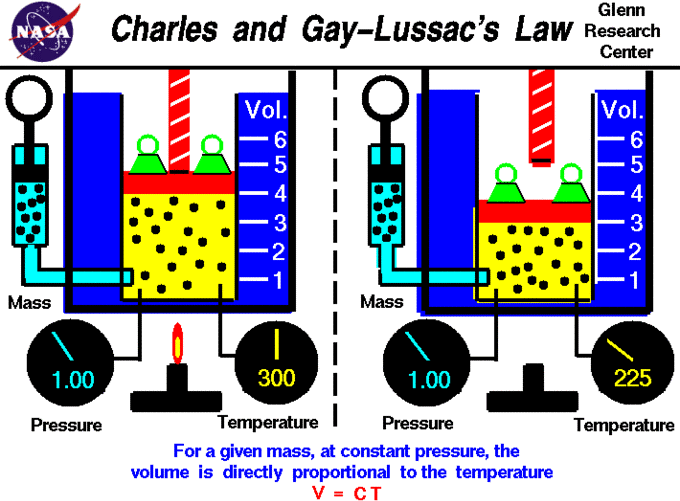

Charle’s law states that at constant pressure, the volume of a gas is directly proportional to the temperature (in Kelvin) in a closed system. Basically, this law describes the relationship between the temperature and volume of the gas.

Mathematically, Charle’s law can be expressed as,

Where, V = volume of gas, T = temperature of the gas in Kelvin. Another form of this equation can be written as,

V 1 / T 1 = V 2 / T 2

Problems Related to Charle’s Law

A sample of carbon dioxide in a pump has a volume of 21.5 mL, and it is at 50.0 °C. When the amount of gas and pressure remain constant, find the new volume of carbon dioxide in the pump if the temperature is increased to 75.0 °C.

V 2 = V 1 T 2 /T 1

V 2 = 7,485.225/ 323.15

V 2 = 23.16 mL

Gay-Lussac law gives the relationship between temperature and pressure at constant volume. The law states that at a constant volume, the pressure of the gas is directly proportional to the temperature of a given gas.

If you heat up a gas, the molecules will be given more energy; they move faster. If you cool down the molecules, they slow down, and the pressure decreases. The change in temperature and pressure can be calculated using the Gay-Lussac law, and it is mathematically represented as,

P / T = k 1

P 1 / T 1 = P 2 / T 2

Where, P is the pressure of the gas, and T is the temperature of the gas in Kelvin.

Problems Related to Gay-Lussac Law

Determine the pressure change when a constant volume of gas at 2.00 atm is heated from 30.0 °C to 40.0 °C.

P 1 = 2.00 atm P 2 =? T 1 = (30 + 273) = 303 K T 2 = (40 + 273) = 313 K

According to the Gay-Lussac law, P ∝ T P/T = constant P 1 /T 1 = P 2 /T 2 P 2 =( P 1 T 2 ) / T 1 = (2 x 313) / 303 =2.06 atm

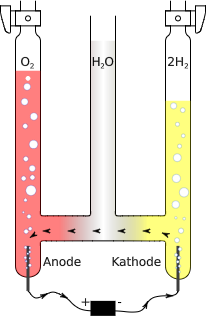

Avogadro’s law states that if the gas is an ideal gas, the same number of molecules exists in the system. The law also states that equal volumes of gases at the same temperature and pressure contain equal numbers of molecules. This statement can be mathematically expressed as,

V / n = constant

V 1 / n 1 = V 2 / n 2

Where V is the volume of an ideal gas and n represents the number of gas molecules.

Problems Related to Avogadro’s Law

At constant temperature and pressure, 6.00 L of a gas is known to contain 0.975 mol. If the amount of gas is increased to 1.90 mol, what new volume will result?

V 1 = 6.00 L V 2 = ? n 1 = 0.975 n 2 = 1.90 mol

According to Avogadro’s law V ∝ n V/n = constant V 1 / n 1 = V 2 / n 2 V 2 = V 1 n 2 /n 1 V 2 = (6 x 1.90)/ 0.975 = 11.69 L

The combined gas law, also known as a general gas equation, is obtained by combining three gas laws which include Charle’s law, Boyle’s Law and Gay-Lussac law. The law shows the relationship between temperature, volume and pressure for a fixed quantity of gas.

The general equation of combined gas law is given as,

If we want to compare the same gas in different cases, the law can be represented as,

P 1 V 1 / T 1 = P 2 V 2 / T 2

Also Read: Kinetic Theory of Gas

Ideal Gas Law

Much like the combined gas law, the ideal gas law is also an amalgamation of four different gas laws. Here, Avogadro’s law is added, and the combined gas law is converted into the ideal gas law. This law relates four different variables, which are pressure, volume, number of moles or molecules and temperature. Basically, the ideal gas law gives the relationship between these four different variables.

Recommended Videos

Boyle’s law – video lesson.

Ideal Gas Equation

Mathematically Ideal gas law is expressed as,

V = volume of gas

T = temperature of the gas

P = pressure of the gas

R = universal gas constant

And n denotes the number of moles

We can also use the equivalent equation given below.

Where, k = Boltzmann constant and N = number of gas molecules.

Ideal gases are also known as perfect gas. It establishes a relationship among the four different gas variables such as pressure (P), Volume (V), Temperature (T) and amount of gas (n).

Ideal Gas Properties and Characteristics

- The motion of ideal gas in a straight line is constant and random.

- The gas occupies a very small space because the particle in the gas is minimal.

- There is no force present between the particle of the gas. Particles only collide elastically with the walls of the container and with each other.

- The average kinetic energy of the gas particle is directly proportional to the absolute temperature.

- The gases are made up of many of the same particles (atoms or molecules), which are perfectly hard spheres and also very small.

- The actual volume of the gas molecule is considered negligible as compared to the space between them, and because of this reason, they are considered as the point masses.

Gas Law Formula Table

The following table consists of all the formulas of Gas Law:

Problems Related to Gas Law

(1) A sealed jar whose volume is exactly 1 L, which contains 1 mole of air at a temperature of 20 degrees Celcius, assuming that the air behaves as an ideal gas. So, what is the pressure inside the jar in Pa?

By solving with the help of the ideal gas equation,

(1) By rearranging the equation, we can get,

(2) Write down all the values which are known in the SI unit.

R= 8.314J/K/mol

T= 20degree celcius=(20+273.15)K=293.15K

V=1L=0.001m 3

(3) Put all the values in the equation

P=(1*8.314*293.15)/0.001

P= 2,437,249

P=2.437*10^6 Pa

The pressure is almost 24atm.

Application of Gas-law

During summer, when the temperature is high, and pressure is also high, a tire is at risk of bursting because it is inflated with air. Or when you start climbing a mountain, you feel problems related to inhaling. Why does it happen?

When the physical condition changes with changes in the environment, the behaviour of gases particle also deviates from their normal behaviour. These changes in gas behaviour can be studied by studying various laws known as gas laws.

Gas laws have been around for quite some time now, and they significantly assist scientists in finding amounts, pressure, volume, and temperature related to matters of gas.

Besides, the gas law, along with modern forms, are used in many practical applications that concern gas. For example, respiratory gas measurements of tidal volume and vital capacity etc., are done at ambient temperature while these exchanges actually take place in the body at 37 degrees Celsius. The law is used often in thermodynamics as well as in fluid dynamics. Also, it can be used in weather forecast systems.

Frequently Asked Questions on Gas Laws

What is an ideal gas.

Gases are puzzling. They are packed with a large number of very energetic gas molecules that can collide and interact. Because it’s difficult to precisely characterise a real gas, the concept of an ideal gas was developed as an approximation to help us model and understand the behaviour of real gases.

What are the rules followed by ideal gas?

Ideal gas molecules are neither attracted nor repellent to one another. An elastic collision is the only interaction between ideal gas molecules when they collide with each other or with the container’s walls.

The volume of ideal gas molecules is zero. The ideal gas molecules are considered as point particles with no volume in and of themselves.

What is the expression for ideal gas law?

PV = nRT P is the pressure of the ideal gas. V is the volume of the ideal gas. T is the temperature of the ideal gas. R is the gas constant. n is the number of moles.

Put your understanding of this concept to test by answering a few MCQs. Click ‘Start Quiz’ to begin!

Select the correct answer and click on the “Finish” button Check your score and answers at the end of the quiz

Visit BYJU’S for all JEE related queries and study materials

Your result is as below

Request OTP on Voice Call

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post My Comment

Register with Aakash BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

15 Gas Laws

LumenLearning

Boyle’s Law: Volume and Pressure

Boyle’s law describes the inverse relationship between the pressure and volume of a fixed amount of gas at a constant temperature.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Apply Boyle’s law using mathematical calculations.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- According to Boyle’s law, an inverse relationship exists between pressure and volume.

- Boyle’s law holds true only if the number of molecules (n) and the temperature (T) are both constant.

- Boyle’s law is used to predict the result of introducing a change in volume and pressure only and only to the initial state of a fixed quantity of gas.

- The relationship for Boyle’s law can be expressed as follows: P 1 V 1 = P 2 V 2 , where P 1 and V 1 are the initial pressure and volume values, and P 2 and V 2 are the values of the pressure and volume of the gas after change.

- isotherm : In thermodynamics, a curve on a p-V diagram for an isothermal process.

- Boyle’s law : The absolute pressure and volume of a given mass of confined gas are inversely proportional while the temperature remains unchanged within a closed system.

- ideal gas : A theoretical gas composed of a set of randomly moving, noninteracting point particles.

Boyle’s Law

Boyle’s law (sometimes referred to as the Boyle-Mariotte law) states that the absolute pressure and volume of a given mass of confined gas are inversely proportional, provided the temperature remains unchanged within a closed system. This can be stated mathematically as follows:

[latex]P_1V_1 = P_2V_2[/latex]

History and Derivation of Boyle’s Law

The law was named after chemist and physicist Robert Boyle, who published the original law in 1662. Boyle showed that the volume of air trapped by a liquid in the closed short limb of a J-shaped tube decreased in exact proportion to the pressure produced by the liquid in the long part of the tube.

The trapped air acted much like a spring, exerting a force opposing its compression. Boyle called this effect “the spring of the air” and published his results in a pamphlet with that title. The difference between the heights of the two mercury columns gives the pressure (76 cm = 1 atm), and the volume of the air is calculated from the length of the air column and the tubing diameter.

The law itself can be stated as follows: for a fixed amount of an ideal gas kept at a fixed temperature, P (pressure) and V (volume) are inversely proportional—that is, when one doubles, the other is reduced by half.

Remember that these relations hold true only if the number of molecules (n) and the temperature (T) are both constant.

In an industrial process, a gas confined to a volume of 1 L at a pressure of 20 atm is allowed to flow into a 12-L container by opening the valve that connects the two containers. What is the final pressure of the gas?

Set up the problem by setting up the known and unknown variables. In this case, the initial pressure is 20 atm (P 1 ), the initial volume is 1 L (V 1 ), and the new volume is 1L + 12 L = 13 L (V 2 ) since the two containers are connected. The new pressure (P 2 ) remains unknown. P 1 V 1 = P 2 V 2

(20 atm)(1 L) = (P 2 )(13 L)

20 atom = (13) P 2

P 2 = 1.54 atm

The final pressure of the gas is 1.54 atm.

“Boyle’s Law”: An introduction to the relationship between pressure and volume and an explanation of how to solve gas problems with Boyle’s law.

Charles’s and gay-lussac’s law: temperature and volume.

Charles’s and Gay-Lussac’s law states that at constant pressure, temperature, and volume are directly proportional.

State Charles’s Law and its underlying assumptions.

- The lower the pressure of a gas, the greater its volume (Boyle’s law); at low pressures, [latex]\frac{V}{273}[/latex] will have a larger value.

- Charles’s and Gay-Lussac’s law can be expressed algebraically as [latex]\frac{\Delta V}{\Delta T} = \text{constant or} \frac{V_1}{T_1} = \frac{V_2}{T_2}[/latex]

- Charles’ law : At constant pressure, the volume of a given mass of an ideal gas increases or decreases by the same factor as its temperature on the absolute temperature scale (i.e., gas expands as temperature increases).

- absolute zero : The theoretical lowest possible temperature; by international agreement, absolute zero is defined as 0 K on the Kelvin scale and as −273.15° on the Celsius scale.

Charles’s and Guy-Lussac’s Law

Charles’s law describes the relationship between the volume and temperature of a gas. The law was first published by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac in 1802, but he referenced unpublished work by Jacques Charles from around 1787. This law states that at constant pressure, the volume of a given mass of an ideal gas increases or decreases by the same factor as its temperature (in Kelvin); in other words, temperature and volume are directly proportional. Stated mathematically, this relationship is

- [latex]\frac{V_1}{T_1} = \frac{V_2}{T_2}[/latex]

- A car tire filled with air has a volume of 100 L at 10°C. What will the expanded volume of the tire be after driving the car has raised the temperature of the tire to 40°C?

- [latex]\frac{\text{100 L}}{\text{283 K}} = \frac{V_2}{\text{313 K}}[/latex]

- [latex]V_2 = \text{110 L}[/latex]

V vs. T Plot and Charles’s Law

A visual expression of Charles’s and Gay-Lussac’s law is shown in a graph of the volume of one mole of an ideal gas as a function of its temperature at various constant pressures. The plots show that the ratio [latex]\frac{V}{T}[/latex] (and thus [latex]\frac{\Delta V}{\Delta T}[/latex]) is a constant at any given pressure. Therefore, the law can be expressed algebraically as [latex]\frac{\Delta V}{\Delta T} = \text{constant or } \frac{V_1}{T_1} = \frac{V_2}{T_2}[/latex].

Extrapolation to Zero Volume

If a gas contracts by 1/273 of its volume for each degree of cooling, it should contract to zero volume at a temperature of –273°C; this is the lowest possible temperature in the universe, known as absolute zero. This extrapolation of Charles’s law was the first evidence of the significance of this temperature.

Why Do the Plots for Different Pressures Have Different Slopes?

The lower a gas’s pressure, the greater its volume (Boyle’s law), so at low pressures, the fraction [latex]\frac{V}{273}[/latex] will have a larger value; therefore, the gas must “contract faster” to reach zero volume when its starting volume is larger.

“Charles’ Law”: Discusses the relationship between volume and temperature of a gas and explains how to solve problems using Charles’s law.

Avogadro’s law: volume and amount.

Avogadro’s law states that at the same temperature and pressure, equal volumes of different gases contain an equal number of particles.

State Avogadro’s law and its underlying assumptions.

- The number of molecules or atoms in a specific volume of ideal gas is independent of size or the gas’s molar mass.

- Avogadro’s law is stated mathematically as follows, [latex]\frac{V}{n} = k[/latex], where V is the volume of the gas, n is the number of moles of the gas, and k is a proportionality constant.

- Volume ratios must be related to the relative numbers of molecules that react; this relationship was crucial in establishing the formulas of simple molecules at a time when the distinction between atoms and molecules was not clearly understood.

- Avogadro’s law : Under the same temperature and pressure conditions, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of particles; also referred to as Avogadro’s hypothesis or Avogadro’s principle.

Definition of Avogadro’s Law

Avogadro’s law (sometimes referred to as Avogadro’s hypothesis or Avogadro’s principle) is a gas law; it states that under the same pressure and temperature conditions, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of molecules. The law is named after Amedeo Avogadro who, in 1811, hypothesized that two given samples of an ideal gas—of the same volume and at the same temperature and pressure—contain the same number of molecules; thus, the number of molecules or atoms in a specific volume of ideal gas is independent of their size or the molar mass of the gas. For example, 1.00 L of N 2 gas and 1.00 L of Cl 2 gas contain the same number of molecules at Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP).

Avogadro’s law is stated mathematically as:

[latex]\frac{V}{n} = k[/latex]

V is the volume of the gas, n is the number of moles of the gas, and k is a proportionality constant.

As an example, equal volumes of molecular hydrogen and nitrogen contain the same number of molecules and observe ideal gas behavior when they are at the same temperature and pressure. In practice, real gases show small deviations from the ideal behavior and do not adhere to the law perfectly; the law is still a useful approximation for scientists, however.

Significance of Avogadro’s Law

Discovering that the volume of a gas was directly proportional to the number of particles it contained was crucial in establishing the formulas for simple molecules at a time (around 1811) when the distinction between atoms and molecules was not clearly understood. In particular, the existence of diatomic molecules of elements such as H 2 , O 2 , and Cl 2 was not recognized until the results of experiments involving gas volumes were interpreted.

Early chemists calculated the molecular weight of oxygen using the incorrect formula HO for water. This led to the molecular weight of oxygen being miscalculated as 8, rather than 16. However, when chemists found that an assumed reaction of [latex]\text{H + Cl} \rightarrow \text{HCl}[/latex] yielded twice the volume of HCl, they realized hydrogen and chlorine were diatomic molecules. The chemists revised their reaction equation to be [latex]\text{H}_\text{2} \text{ + Cl}_\text{2} \rightarrow \text{2HCl}[/latex].

When chemists revisited their water experiment and their hypothesis that [latex]\text{HO } \rightarrow \text{ H + O}[/latex], they discovered that the volume of hydrogen gas consumed was twice that of oxygen. By Avogadro’s law, this meant that hydrogen and oxygen were combining in a 2:1 ratio. This discovery led to the correct molecular formula for water (H 2 O) and the correct reaction [latex]\text{2H}_\text{2} \text{O} \rightarrow \text{2H}_\text{2} \text{ + O}_\text{2}[/latex].

“Avogadro’s Law”: Practice problems and examples looking at the relationship between the volume and amount of gas (number of moles) in a gas sample.

Licenses and attributions, cc licensed content, shared previously.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by : Boundless.com. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- ideal gas. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ideal_gas . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boyle’s law. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Boyle’s_law . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boyle’s law. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boyle’s_law . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemistry: the gas laws. Provided by : Steve Lower’s Website. Located at : http://www.chem1.com/acad/webtext/gas/gas_2.html . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Isotherm. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/isotherm . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boyles Law animated. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Boyles_Law_animated.gif . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- “Boyle’s Law.” Located at : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZoGtVVu3ymQ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Standard YouTube license

- absolute zero. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/absolute_zero . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Charles’s law. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles’s_law . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by : AskApache. Located at : http://nongnu.askapache.com/fhsst/Chemistry_Grade_10-12.pdf . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Charles. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles?+law . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- glussac.gif. Provided by : National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Located at : https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/glussac.html . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- “Charles’ Law”. Located at : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oIfFoiwRCVE . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Standard YouTube license

- Avogadro’s law. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avogadro’s_law . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Avogadro’s Law. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avogadro’s%20Law . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- “Charles’ Law.” Located at : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oIfFoiwRCVE . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Standard YouTube license

- “Avogadro’s Law.” Located at : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i-vA9uLSf7Y . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Standard YouTube license

- Hofmann_voltameter.svg. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hofmann_voltameter.svg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

This chapter is an adaptation of the chapter “ Gas Laws ” in Boundless Chemistry by LumenLearning and is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

in thermodynamics, a curve on a p-V diagram for an isothermal process

the absolute pressure and volume of a given mass of confined gas are inversely proportional, while the temperature remains unchanged within a closed system

a theoretical gas composed of a set of randomly-moving, non-interacting point particles

at constant pressure, the volume of a given mass of an ideal gas increases or decreases by the same factor as its temperature on the absolute temperature scale (i.e. gas expands as temperature increases)

the coldest possible temperature, zero on the Kelvin scale, or approximately −273.15 °C, −459.67 °F; total absence of heat; temperature at which motion of all molecules ceases

under the same temperature and pressure conditions, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of particles; also referred to as Avogadro’s hypothesis or Avogadro’s principle

Introductory Chemistry Copyright © by LumenLearning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Introduction to Temperature, Kinetic Theory, and the Gas Laws

Chapter outline.

Heat is something familiar to each of us. We feel the warmth of the summer Sun, the chill of a clear summer night, the heat of coffee after a winter stroll, and the cooling effect of our sweat. Manifestations of heat transfer —the movement of heat energy from one place or material to another—are apparent throughout the universe. Heat from beneath Earth’s surface is brought to the surface in flows of incandescent lava. The Sun warms Earth’s surface and is the source of much of the energy we find on it. Rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide threaten to trap more of the Sun’s energy, perhaps fundamentally altering the ecosphere. In space, supernovas explode, briefly radiating more heat than an entire galaxy does.

What is heat? How do we define it? How is it related to temperature? What are heat’s effects? How is it related to other forms of energy and to work? We will find that, in spite of the richness of the phenomena, there is a small set of underlying physical principles that unite the subjects and tie them to other fields.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/college-physics-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-science-and-the-realm-of-physics-physical-quantities-and-units

- Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: College Physics 2e

- Publication date: Jul 13, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-physics-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-science-and-the-realm-of-physics-physical-quantities-and-units

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-physics-2e/pages/13-introduction-to-temperature-kinetic-theory-and-the-gas-laws

© Jan 19, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Quick links

- Make a Gift

- Directories

How is the Ideal Gas Law Explanatory?

Using the ideal gas law as a comparative example, this essay reviews contemporary research in philosophy of science concerning scientific explanation. It outlines the inferential, causal, unification, and erotetic conceptions of explanation and discusses an alternative project, the functional perspective. In each case, the aim is to highlight insights from these investigations that are salient for pedagogical concerns. Perhaps most importantly, this essay argues that science teachers should be mindful of the normative and prescriptive components of explanatory discourse both in the classroom and in science more generally. Giving attention to this dimension of explanation not only will do justice to the nature of explanatory activity in science but also will support the development of robust reasoning skills in science students while helping them understand an important respect in which science is more than a straightforward collection of empirical facts, and consequently, science education involves more than simply learning them.

- YouTube

- Newsletter

- More ways to connect

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

How is the Ideal Gas Law Explanatory?

Using the ideal gas law as a comparative example, this essay reviews contemporary research in philosophy of science concerning scientific explanation. It outlines the inferential, causal, unification, and erotetic conceptions of explanation and discusses an alternative project, the functional perspective. In each case, the aim is to highlight insights from these investigations that are salient for pedagogical concerns. Perhaps most importantly, this essay argues that science teachers should be mindful of the normative and prescriptive components of explanatory discourse both in the classroom and in science more generally. Giving attention to this dimension of explanation not only will do justice to the nature of explanatory activity in science but also will support the development of robust reasoning skills in science students while helping them understand an important respect in which science is more than a straightforward collection of empirical facts, and consequently, science education involves more than simply learning them.

Related Papers

Andrea Woody

Philosophy of science offers a rich lineage of analysis concerning the nature of scientific explanation, but the vast majority of this work, aiming to provide an analysis of the relation that binds a given explanans to its corresponding explanandum, presumes the proper analytic focus rests at the level of individual explanations. There are, however, other questions we could ask about explanation in science, such as: What role(s) does explanatory practice play in science? Shifting focus away from explanations, as achievements, toward explaining, as a coordinated activity of communities, the functional perspective aims to reveal how the practice of explanatory discourse functions within scientific communities given their more comprehensive aims and practices. In this paper, I outline the functional perspective, argue that taking the functional perspective can reveal important methodological roles for explanation in science, and consequently, that beginning here provides resources for developing more adequate responses to traditional concerns. In particular, through an examination of the ideal gas law, I emphasize the normative status of explanations within scientific communities and discuss how such status underwrites a compelling rationale for explanatory power as a theoretical virtue. Keywords: explanation, explanatory power, functional perspective, idealization, ideal gas law

Science & Education

Ingo Brigandt

Contributing to the recent debate on whether or not explanations ought to be differentiated from arguments, this article argues that the distinction matters to science education. I articulate the distinction in terms of explanations and arguments having to meet different standards of adequacy. Standards of explanatory adequacy are important because they correspond to what counts as a good explanation in a science classroom, whereas a focus on evidence-based argumentation can obscure such standards of what makes an explanation explanatory. I provide further reasons for the relevance of not conflating explanations with arguments (and having standards of explanatory adequacy in view). First, what guides the adoption of the particular standards of explanatory adequacy that are relevant in a scientific case is the explanatory aim pursued in this context. Apart from explanatory aims being an important aspect of the nature of science, including explanatory aims in classroom instruction also promotes students seeing explanations as more than facts, and engages them in developing explanations as responses to interesting explanatory problems. Second, it is of relevance to science curricula that science aims at intervening in natural processes, not only for technological applications, but also as part of experimental discovery. Not any argument enables intervention in nature, as successful intervention specifically presupposes causal explanations. Students can fruitfully explore in the classroom how an explanatory account suggests different options for intervention.

Vin Saavedra

This paper presents an analysis of the different types of reasoning and physical explanation used in science, common thought, and physics teaching. It then reflects on the learning difficulties connected with these various approaches, and suggests some possible didactic strategies. Although causal reasoning occurs very frequently in common thought and daily life, it has long been the subject of debate and criticism among philosophers and scientists. In this paper, I begin by providing a description of some general tendencies of common reasoning that have been identified by didactic research. Thereafter, I briefly discuss the role of causality in science, as well as some different types of explanation employed in the field of physics. I then present some results of a study examining the causal reasoning used by students in solid and fluid mechanics. The differences found between the types of reasoning typical of common thought and those usually proposed during instruction can create learning difficulties and impede student motivation. Many students do not seem satisfied by the mere application of formal laws and functional relations. Instead, they express the need for a causal explanation, a mechanism that allows them to understand how a state of affairs has come about. I discuss few didactic strategies aimed at overcoming these problems, and describe, in general terms, two examples of mechanics teaching sequences which were developed and tested in different contexts. The paper ends with a reflection on the possible role to be played in physics learning by intuitive and imaginative thought, and the use of simple explanatory models based on physical analogies and causal mechanisms.

Kevin McCain

Foundations of Science

Gerhard Schurz

Jeroen Van Bouwel , Leen De Vreese

This paper investigates the working-method of three important philosophers of explanation: Carl Hempel, Philip Kitcher and Wesley Salmon. We argue that they do three things: (i) construct an explication in the sense of Carnap, which then is used as a tool to make (ii) descriptive and (iii) normative claims about the explanatory practice of scientists. We also show that they did well with respect to (i), but that they failed to give arguments for their descriptive and normative claims. We think it is the responsibility of current philosophers of explanation to go on where Hempel, Kitcher and Salmon failed. However, we should go on in a clever way. We call this clever way the “pragmatic approach to scientific explanation.” We clarify what this approach consists in and defend it.

Science & Education

Sahar Alameh

Alirio Rosales

This paper describes the development of theories of scientific explanation since Hempel's earliest models in the 1940ies. It focuses on deductive and probabilistic why-explanations and their main problems: lawlikeness, explanation-prediction asymmetries, causality, deductive and probabflistic relevance, maximal specifity and homogenity, tile height of the probability value. For all of these topic the paper explains the most important approaches as well as their criticism, including the author's own accounts. Three main theses of this paper are: (1) Both deductive and probabilistic explanations are important in science, not reducible to each other. (2) One must distinguish between (cause giving) explanations and (reason giving) justifications and predictions. (3) The adequacy of deductive as well as probabilistic explanations is relative to a pragmatically given background knowledge-which does not exclude, however, the possibility of purely semantic models.

Social Science Research Network

Mariam Thalos

RELATED PAPERS

XXIII Reunión Científica del GAB; II Encuentro Argentino - Chileno de Biometría. Neuquén, 10, 11 y 12 de octubre de 2018.

Guillermo R Pratta

arXiv (Cornell University)

christian espindola

Bioinformatics

Journal of veterinary diagnostic investigation : official publication of the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians, Inc

GM Barrington

Neuropsychopharmacology

Dongrong Xu

Journal of Surgical Research

Robert Talac

Estudos de Literatura Brasileira Contemporânea

Alice Áurea Penteado Martha

manuel muriel

Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM

Mahmoud Rahmati

Geraldo C O R R E I A Sobrinho

Ecological Entomology

Erick Provost

Journal of Molecular Structure-theochem

Frédéric Bohr

Real Estate Economics

Paul Asabere

Journal of Crohn's and Colitis

Simon Ghaly

Ezekiel Chinyio

PENSAMIENTO, vol. 79 (2023), núm. 304, pp. 723-739

Ramsés Sánchez Soberano

Garry Carnegie

Jurnal Chart Datum

Dipo Yudhatama

Gayana (Concepción)

Ana Hinojosa

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

How is the Ideal Gas Law Explanatory?

- Published: 07 December 2011

- Volume 22 , pages 1563–1580, ( 2013 )

Cite this article

- Andrea I. Woody 1

4678 Accesses

12 Citations

Explore all metrics

Using the ideal gas law as a comparative example, this essay reviews contemporary research in philosophy of science concerning scientific explanation. It outlines the inferential, causal, unification, and erotetic conceptions of explanation and discusses an alternative project, the functional perspective. In each case, the aim is to highlight insights from these investigations that are salient for pedagogical concerns. Perhaps most importantly, this essay argues that science teachers should be mindful of the normative and prescriptive components of explanatory discourse both in the classroom and in science more generally. Giving attention to this dimension of explanation not only will do justice to the nature of explanatory activity in science but also will support the development of robust reasoning skills in science students while helping them understand an important respect in which science is more than a straightforward collection of empirical facts, and consequently, science education involves more than simply learning them.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Scientific Truth in a Post-Truth Era: A Review*

Du Bois’ democratic defence of the value free ideal

Living the DReaM: The interrelations between statistical, scientific and nature of science uncertainty articulations through citizen science

Some of these conceptions have several distinct variants.

The terminology of nomological subsumption simply refers to particular states of affairs (that is, descriptions of events or objects with specific properties) being subsumed under general laws in the sense that these states of affairs are seen to be instances of some lawlike generalizations.

By ‘phenomenological’ I mean a description of phenomena solely in terms of the detectable and measurable properties of macroscopic physical objects. Phenomenological descriptions, or models, of gases are composed of variables representing measurable quantities, including temperature, pressure, and volume, drawn from the framework of phenomenological thermodynamics (and without reference to the underlying micro-level constitution of gases).

The interested reader might want to consider what Woodward would say about the air mattress example offered by Salmon.

Friedman’s original article refers to Graham’s law of diffusion. As an anonymous referee helpfully pointed out, the kinetic theory of gases allows one to derive the law of effusion, but not the more complex law of diffusion.

More precisely, the unifying power of a theoretical structure varies directly with the size of the conclusion set regarding empirical phenomena generated from the associated argument patterns, inversely with the number of argument patterns, and directly with the stringency of the patterns (Kitcher 1989 : 435).

‘Erotetics’ or ‘erotetic logic’ is the area of study concerned with the logic and pragmatics of questions.

But what about the person who generates an explanatory question and answers it herself? This is certainly possible in principle, but as Salmon ( 1998 ) and Van Fraassen ( 1980 ) both discuss, explanatory demands would not arise for an omniscient being. Explanations arise from ignorance, or at the very least, uncertainty. Consequently, for an individual to pose a genuine explanation-seeking question, even to herself, in some respect she must not already know the answer and she will likely turn to some external source of information, one she considers authoritative, to find the answer. In doing so, she is engaged in an activity that is arguably social.

A rationale for the ordering can be distinct, of course, from the reasons why the ordering was originally established. That gases are an early topic in introductory textbooks is partially a legacy of the historical development of chemistry, in which gas experiments played a central role as the discipline was first emerging during the eighteenth century. Still, there is common ground between the historical explanation of why we start with gases and the current rationale for doing so. In each, the investigation of gas behavior has cultivated the development of atomic hypotheses; this fact is as clearly evidenced in the writings of Dalton ( 1808 ) as in any contemporary text.

Beall, H., Trimbur, J., & Weininger, S. (1994). Mastery, insight, and the teaching of chemistry. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 3 , 99–105.

Article Google Scholar

Braaten, M., & Windschitl, M. (2011). Working toward a stronger conceptualization of scientific explanation for science education. Science Education, 95 , 639–669.

Cartwright, N. (1983). How the laws of physics lie . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Book Google Scholar

Dalton, J. (1808). A new system of chemical philosophy . London: Peter Owen Limited.

Google Scholar

De Vries, E., Lund, K., & Baker, M. (2002). Computer-mediated epistemic dialogue: Explanation and argumentation as vehicles for understanding scientific notions. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 11 , 63–103.

Dear, P. (2006). The intelligibility of nature: How science makes sense of the world . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dowe, P. (2000). Physical causation . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Friedman, M. (1974). Explanation and scientific understanding. The Journal of Philosophy, 71 , 5–19.

Hempel, C. G. (1965a). Aspects of scientific explanation. In C. Hempel (Ed.), Aspects of scientific explanation and other essays in the philosophy of science (pp. 331–496). New York: The Free Press.

Hempel, C. G. (1965b). The logic of functional analysis. In C. Hempel (Ed.), Aspects of scientific explanation and other essays in the philosophy of science (pp. 297–330). New York: The Free Press.

Hempel, C., & Oppenheim, P. (1965). Studies in the logic of explanation. In C. Hempel (Ed.), Aspects of scientific explanation and other essays in the philosophy of science (pp. 245–290). New York: The Free Press.

Hitchcock, C. (1995). Discussion: Salmon on explanatory relevance. Philosophy of Science, 62 , 304–320.

Kitcher, P. (1976). Explanation, conjunction, and unification. The Journal of Philosophy, 73 , 207–212.

Kitcher, P. (1981). Explanatory unification. Philosophy of Science, 48 , 507–531.

Kitcher, P. (1989). Explanatory unification and the causal structure of the world. In P. Kitcher & W. Salmon (Eds.), Minnesota studies in the philosophy of science, volume XIII: Scientific explanation (pp. 410–505). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lewis, D. (1986). Causal explanation. In D. Lewis (Ed.), Philosophical papers (Vol. 2, pp. 214–240). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Liu, X. (2006). Effects of combined hands-on laboratory and computer modeling on students learning of gas laws: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 15 , 89–100.

Mahan, B. H. (1975). University chemistry . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Merton, R. K. (1957). Manifest and latent functions. Social theory and social structure . New York: The Free Press.

Nagel, E. (1961). The structure of science . New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World.

Salmon, W. (1984). Scientific explanation and the causal structure of the world . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Salmon, W. (1998). Causality and explanation . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Salmon, W. (2006). Four decades of scientific explanation . Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Sandoval, W. A., & Millwood, K. (2005). The quality of students’ use of evidence in written scientific explanations. Cognition and Instruction, 23 , 23–55.

Smith, C., Maclin, D., Grosslight, L., & Davis, H. (1997). Teaching for understanding: A study of students’ preinstruction theories of matter and a comparison of the effectiveness of two approaches to teaching about matter and density. Cognition and Instruction, 15 , 317–393.

Strevens, M. (2009). Depth: An account of scientific explanation . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Van Fraassen, B. C. (1980). The scientific image . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Welsh, S. M. (2002). Advice to a new science teacher: The importance of establishing a theme in teaching scientific explanation. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 11 , 93–95.

Woody, A. I. (2003). On explanatory practice and disciplinary identity. Chemical explanation: Characteristics, development, autonomy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences , 988 , 22–29.

Woody, A. I. (2004). Telltale signs: What common explanatory strategies in chemistry reveal about explanation itself. Foundations of Chemistry , 6 , 13–43.

Woodward, J. (2003). Making things happen: A theory of causal explanation . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yamalidou, M. (2001). Molecular representations: Building tentative links between history of science and the study of cognition. Science & Education, 10 , 423–451.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Jim Greisemer, Roberta Millstein, the audience for a Philosophy Department Colloquium at University of California at Davis in February 2011, two anonymous referees for this journal, and especially members of a graduate seminar at the University of Washington in winter 2011 for constructive feedback and insights regarding aspects of this project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Philosophy, University of Washington, Box 353350, Seattle, WA, 98195, USA

Andrea I. Woody

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrea I. Woody .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Woody, A.I. How is the Ideal Gas Law Explanatory?. Sci & Educ 22 , 1563–1580 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-011-9424-6

Download citation

Published : 07 December 2011

Issue Date : July 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-011-9424-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scientific Explanation

- Explanatory Status

- Functional Perspective

- Individual Explanation

- Argument Pattern

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Ukraine-Russia war latest: Vladimir Putin repeats warning he could send weapons to adversaries of the West

Speaking at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum, Vladimir Putin also says he does not see the conditions for the use of nuclear weapons as set out in Russia's nuclear doctrine - but adds he could not rule out a change to it.

Friday 7 June 2024 17:15, UK

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

- Russia economically strong despite 'illegitimate sanctions'

- Ukraine has right to strike targets in Russia - NATO chief

- Russian vessels to make port in Cuba in 'hopes of invoking memory of missile crisis'

- Biden to discuss $225m package with Zelenskyy in France

- Ivor Bennett: Why is Lavrov in Africa?

- Big picture: Everything you need to know about the war right now

- Your questions answered: Are there any signs of an underground resistance in Russia?

- Live reporting by Andy Hayes and Ollie Cooper

Thank you for reading.

We will be back soon with more updates from the war in Ukraine.

Vladimir Putin has said he does not see the conditions for the use of nuclear weapons as set out in Russia's nuclear doctrine - but added he could not rule out a change to the doctrine.

"We have a nuclear doctrine which states that the use of nuclear arms is possible in an exceptional case, when the sovereignty and territorial integrity of our country is threatened," he told the St Petersburg International Economic Forum.

"But the doctrine can be changed.

"The same applies to nuclear tests. We will carry out tests if needed, but so far there is no such need."

Russia could send weapons to adversaries of the West, Vladimir Putin has warned for a second time.

The Russian president repeated the warning from earlier this week during the St Petersburg Economic Forum.

He did not say what countries or entities he was referring to, and he stressed that Moscow is not doing it currently.

"If they supply (weapons) to the combat zone and call for using these weapons against our territory, why don't we have the right to do the same?" he told the crowds.

"But I'm not ready to say that we will be doing it tomorrow, either."

On Wednesday, Putin told international journalists that Russia could provide long-range weapons to others to strike Western targets in response to NATO allies allowing Ukraine to use their arms to attack Russian territory.

He also reaffirmed Moscow's readiness to use nuclear weapons if it sees a threat to its sovereignty.

Joe Biden has apologised to Volodymyr Zelenskyy for the recent delay in approving new US aid for Ukraine.

Last month, following months of political disagreements, the Senate passed $95bn (£76.2bn) in war aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan .

"I apologise for those weeks of not knowing," the US president said.

"Some of our very conservative members [of Congress] were holding it up.

"But we got it done, finally. We're still in - completely, totally."

The Ukrainian president thanked his counterpart for American assistance.

"It's very important that you stay with us," he said.

"It's very important that in this unity, the United States of America, all American people stay with Ukraine, like it was during World War Two - how the United States helped to save human lives, to save Europe."

The two men were speaking in Paris, the day after D-Day commemorations in Normandy.

Russia needs to boost its use of non-Western currencies, Vladimir Putin said as he addressed the St Petersburg International Economic Forum.

He also said his country needs to reduce imports while calling for a major expansion of its domestic financial markets.

Trade with Asia is soaring, he told delegates, adding that almost two fifths of Russian external trade is now in roubles.

The share conducted in US dollars, euros and other Western currencies has declined.

Russia will try to boost the share of settlements conducted in the currencies of BRICS countries - which include Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, Mr Putin said.

"Last year, the share of payments for Russian exports in the so–called 'toxic' currencies of unfriendly states halved, while the share of the rouble in export and import transactions is growing - it is approaching 40% today," the president said.

Russia has referred to nations that imposed sanctions on it as "unfriendly".

The session begins with an address by the Russian president.

Vladimir Putin says there is a race among world powers to establish sovereignty.

He speaks of the need for countries to both establish partnerships and also to look internally to tackle challenges presented by the current global economic landscape.

Despite all the "obstacles and illegitimate sanctions", Russia remains one of the world's economic leaders, he says.

He adds that "friendly countries" - those that have not joined sanctions against Moscow - account for three quarters of Russia's mutual trade turnover, and praises them for that.

Countries including India and China have strengthened economic ties since Mr Putin launched his war in Ukraine.

Vladimir Putin has taken to the stage in St Petersburg to address the International Economic Forum there.

He's joined by Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwais and Bolivian President Luis Alberto Arce Catacora.

Chairing the session is Sergey Karaganov - a Russian political scientist.

We'll bring you any key lines here in this live blog.

A T-shirt is on sale at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum printed with a phrase attributed to Vladimir Putin, Sky News has discovered.

"If a fight is inevitable, throw the first punch," it says.

The Russian president reportedly said it in 2015.

He apparently explained that it was something he had learned while growing up on the streets of Leningrad - a former name of St Petersburg.

The Russian defence ministry has accused Ukraine of injuring 20 people, including children, in a missile attack on the Russian-controlled eastern Ukrainian city of Luhansk, using US-supplied ATACMS missiles.

Four of five missiles were shot down by air defence systems, the ministry said in a statement.

However, one of the missiles damaged two residential apartment blocks, it added, claiming it was deliberate.

Sky News is unable to verify the allegations.

There has been no immediate comment from Ukraine.

The European Commission supports starting EU accession talks with Ukraine, the country's prime minister has said.

Denys Shmyhal said the commission had confirmed in a report that Kyiv had fulfilled the remaining steps required to start negotiations.

"Now we expect our European partners to take the next step - to start negotiations on European Union membership this month," Mr Shmyhal said on Telegram.

Earlier (7.43am post) we reported that the commission was reportedly ready to recommend that accession talks get underway.

It is part of an attempt to signal support for Kyiv before Hungary takes over the rotating presidency of the EU next month, the Financial Times reported.

The EU announced earlier this year that it was sending an additional £42bn in aid to Ukraine - but only after weeks of resistance from Hungary , which reportedly has concerns about minority rights in Ukraine.

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

MIA > Archive > Pashukanis

Evgeny Pashukanis

Marksistskaia teoriia gosudarstva i prava , pp.9-44 in E. B. Pashukanis (ed.), Uchenie o gosudarstve i prave (1932), Partiinoe Izd., Moscow. From Evgeny Pashukanis, Selected Writings on Marxism and Law (eds. P. Beirne & R. Sharlet), London & New York 1980, pp.273-301. Translated by Peter B. Maggs . Copyright © Peter B. Maggs. Published here by kind permission of the translator. Downloaded from home.law.uiuc.edu/~pmaggs/pashukanis.htm Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive .

Introductory Note

In the winter of 1929-1930, during the first Five Year Plan, the national economy of the USSR underwent dramatic and violent ruptures with the inauguration of forced collectivization and rapid heavy industrialization. Concomitantly, it seemed, the Party insisted on the reconstruction and realignment of the appropriate superstructures in conformity with the effectuation of these new social relations of production. In this spirit Pashukanis was no longer criticized but now overtly attacked in the struggle on the “legal front”. In common with important figures in other intellectual disciplines, such as history, in late 1930 Pashukanis undertook a major self-criticism which was qualitatively different from the incremental changes to his work that he had produced earlier. During the following year, 1931, Pashukanis outlined this theoretical reconstruction in his speech to the first conference of Marxist jurists, a speech entitled Towards a Marxist-Leninist Theory of Law . The first results appeared a year later in a collective volume The Doctrine of State and Law .

Chapter I of this collective work is translated below, The Marxist Theory of State and Law , and was written by Pashukanis himself It should be noted that this volume exemplifies the formal transformations which occurred in Soviet legal scholarship during this heated period. Earlier, Pashukanis and other jurists had authored their own monographs; the trend was now towards a collective scholarship which promised to maximize individual safety. The source of authority for much of the work that ensued increasingly became the many expressions of Stalin’s interpretation of Bolshevik history, class struggle and revisionism, most notably his Problems of Leninism . Last, but not least, the language and vocabulary of academic discourse in the 1920s had been rich, open-ended and diverse, and varied tremendously with the personal preferences of the individual author; this gave way to a standardized and simplified style of prose devoid of nuance and ambiguity, and which was very much in keeping with the new theoretical content which comprised official textbooks on the theory of state and law. The reader will perhaps discover that The Marxist Theory of State and Law is a text imbued with these tensions. Pashukanis’ radical reconceptualization of the unity of form and content, and of the ultimate primacy of the relations of production, is without doubt to be preferred to his previous notions. But this is a preference guided by the advantages of editorial hindsight, and we feel that we cannot now distinguish between those reconceptualizations which Pashukanis may actually have intended and those which were produced by the external pressures of political opportunism.

CHAPTER I Socio-economic Formations, State, and Law

1. the doctrine of socio-economic formations as a basis for the marxist theory of state and law.

The doctrine of state and law is part of a broader whole, namely, the complex of sciences which study human society. The development of these sciences is in turn determined by the history of society itself, i.e. by the history of class struggle.

It has long since been noted that the most powerful and fruitful catalysts which foster the study of social phenomena are connected with revolutions. The English Revolution of the seventeenth century gave birth to the basic directions of bourgeois social thought, and forcibly advanced the scientific, i.e. materialist, understanding of social phenomena.

It suffices to mention such a work as Oceana – by the English writer Harrington, and which appeared soon after the English Revolution of the seventeenth century – in which changes in political structure are related to the changing distribution of landed property. It suffices to mention the work of Barnave – one of the architects of the great French Revolution – who in the same way sought explanations of political struggle and the political order in property relations. In studying bourgeois revolutions, French restorationist historians – Guizot, Mineaux and Thierry – concluded that the leitmotif of these revolutions was the class struggle between the third estate (i.e. the bourgeoisie) and the privileged estates of feudalism and their monarch. This is why Marx, in his well-known letter to Weydemeyer, indicates that the theory of the class struggle was known before him. “As far as I am concerned”, he wrote,

no credit is due to me for discovering the existence of classes in modern society, or the struggle between them. Long before me bourgeois historians had described the historical development of this class struggle, and bourgeois economists the economic anatomy of the classes.

What I did that was new was to prove: (1) that the existence of classes is only bound up with particular historical forms of struggle in the development of production ...; (2) that the class struggle inevitably leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat; (3) that this dictatorship itself only constitutes the transition to the abolition of all classes and the establishment of a classless society. [1]

[ Section 2 omitted – eds. ]

Top of the page

3. The class type of state and the form of government

The doctrine of socio-economic formations is particularly important to Marx’s theory of state and law, because it provides the basis for the precise and scientific delineation of the different types of state and the different systems of law.

Bourgeois political and juridical theorists attempt to establish a classification of political and legal forms without scientific criteria; not from the class essence of the forms, but from more or less external characteristics. Bourgeois theorists of the state, assiduously avoiding the question of the class nature of the state, propose every type of artificial and scholastic definition and conceptual distinction. For instance, in the past, textbooks on the state divided the state into three “elements”: territory, population and power.

Some scholars go further. Kellen – one of the most recent Swedish theorists of the state – distinguishes five elements or phenomena of the state: territory, people, economy, society and, finally, the state as the formal legal subject of power. All these definitions and distinctions of elements, or aspects of the state, are no more than a scholastic game of empty concepts since the main point is absent: the division of society into classes, and class domination. Of course, the state cannot exist without population, or territory, or economy, or society. This is an incontrovertible truth. But, at the same time, it is true that all these “elements” existed at that stage of development when there was no state. Equally, classless communist society – having territory, population and an economy – will do without the state since the necessity of class suppression will disappear.

The feature of power, or coercive power, also tells one exactly nothing. Lenin, in his polemic of the 1890s with Struve asserted that: “he most incorrectly sees the distinguishing feature of the state as coercive power. Coercive power exists in every human society – both in the tribal structure and in the family, but there was no state.” And further, Lenin concludes: “The distinguishing feature of the state is the existence of a separate class of people in whose hands power is concentrated. Obviously, no one could use the term ‘State’ in reference to a community in which the ‘organization of order’ is administered in turn by all of its members.” [2]

Struve’s position, according to which the distinguishing feature of a state is coercive power, was not without reason termed “professorial” by Lenin. Every bourgeois science of the state is full of conclusions on the essence of this coercive power. Disguising the class character of the state, bourgeois scholars interpret this coercion in a purely psychological sense. “For power and subordination”, wrote one of the Russian bourgeois jurists (Lazarevsky), “two elements are necessary: the consciousness of those exercising power that they have the right to obedience, and the consciousness of the subordinates that they must obey.”

From this, Lazarevsky and other bourgeois jurists reached the following conclusion: state power is based upon the general conviction of citizens that a specific state has the right to issue its decrees and laws. Thus, the real fact-concentration of the means of force and coercion in the hands of a particular class-is concealed and masked by the ideology of the bourgeoisie. While the feudal landowning state sanctified its power by the authority of religion, the bourgeoisie uses the fetishes of statute and law. In connection with this, we also find the theory of bourgeois jurists-which now has been adopted in its entirety by the Social Democrats whereby the state is viewed as an agency acting in the interests of the whole society. “If the source of state power derives from class”, wrote another of the bourgeois jurists (Magaziner), “then to fulfil its tasks it must stand above the class struggle. Formally, it is the arbiter of the class struggle, and even more than that: it develops the rules of this struggle.”

It is precisely this false theory of the supra-class nature of the state that is used for the justification of the treacherous policy of the Social Democrats. In the name “of the general interest”, Social Democrats deprive the unemployed of their welfare payments, help in reducing wages, and encourage shooting at workers’ demonstrations.

Not wishing to recognize the basic fact, i.e. that states differ according to their class basis, bourgeois theorists of the state concentrate all their attention on various forms of government. But this difference by itself is worthless. Thus, for instance, in ancient Greece and ancient Rome we have the most varied forms of government. But all the transitions from monarchy to republic, from aristocracy to democracy, which we observe there, do not destroy the basic fact that these states, regardless of their different forms, were slave-owning states. The apparatus of coercion, however it was organized, belong to the slave-owners and assured their mastery over the slaves with the help of armed force, assured the right of the slave-owners to dispose of the labour and personality of the slaves, to exploit them, to commit any desired act of violence against them.

Distinguishing between the form of rule and the class essence of the state is particularly important for the correct strategy of the working class in its struggle with capitalism. Proceeding from this distinction, we establish that to the extent that private property and the power of capital remain untouchable, to this extent the democratic form of government does not change the essence of the matter. Democracy with the preservation of capitalist exploitation will always be democracy for the minority, democracy for the propertied; it will always mean the exploitation and subjugation of the great mass of the working people. Therefore theorists of the Second International such as Kautsky, who contrast “democracy” in general with “dictatorship”, entirely refuse to consider their class nature. They replace Marxism with vulgar legal dogmatism, and act as the scholarly champions and lackeys of capitalism.

The different forms of rule had already arisen in slave-owning society. Basically, they consist of the following types: the monarchic state with an hereditary head, and the republic where power is elective and where there are no offices which pass by inheritance. In addition, aristocracy, or the power of a minority (i.e. a state where participation in the administration of the state is limited by law to a definite and rather narrow circle of privileged persons) is distinguished from democracy (or, literally, the rule of the people), i.e. a state where by law all take part in deciding public affairs either directly or through elected representatives. The distinction between monarchy, aristocracy and democracy had already been established by the Greek philosopher Aristotle in the fourth century. All the modern bourgeois theories of the state could add little to this classification.

Actually the significance of one form or another can be gleaned only by taking into account the concrete historical conditions under which it arose and existed, and only in the context of the class nature of a specific state. Attempts to establish any general abstract laws of the movement of state forms – with which bourgeois theorists of the state have often been occupied – have nothing in common with science.

In particular, the change of the form of government depends on concrete historical conditions, on the condition of the class struggle, and on how relationships are formed between the ruling class and the subordinate class, and also within the ruling class itself

The forms of government may change although the class nature of the state remains the same. France, in the course of the nineteenth century, and after the revolution of 1830 until the present time, was a constitutional monarchy, an empire and a republic, and the rule of the bourgeois capitalist state was maintained in all three of these forms. Conversely, the same form of government (for instance a democratic republic) which was encountered in antiquity as one of the variations of the slave-owning state, is in our time one of the forms of capitalist domination.

Therefore, in studying any state, it is very important primarily to examine not its external form but its internal class content, placing the concrete historical conditions of the class struggle at the very basis of scrutiny.

The question of the relationship between the class type of the state and the form of government is still very little developed. In the bourgeois theory of the state this question not only could not be developed, but could not even be correctly posed, because bourgeois science always tries to disguise the class nature of all states, and in particular the class nature of the capitalist state. Often therefore, bourgeois theorists of the state, without analysis, conflate characteristics relating to the form of government and characteristics relating to the class nature of the state.

As an example one may adduce the classification which is proposed in one of the newest German encyclopaedias of legal science.

The author [Kellreiter] distinguishes: (a) absolutism and dictatorship, and considers that the basic characteristic of these forms is that state powers are concentrated in the hands of one person. As an example, he mentions the absolute monarchy of Louis XIV in France, tsarist autocracy in Russia and the dictatorial power which was invested by the procedure of extraordinary powers in the one person, for instance the president of the German Republic on the basis of Art.48 of the Weimar Constitution; (b) constitutionalism, characterized by the separation of powers, their independence and their checks and balances, thereby weakening the pressure exerted by state power on the individual (examples: the German Constitution before the 1918 revolution, and the USA, where the President and Congress have independent powers); (c) democracy, whose basic premise is monism of power and a denial in principle of the difference between power and the subject of power (popular sovereignty, exemplified by the German Republic); and (d) the class-corporative state and the Soviet system where as opposed to formal democracy, the people appear not as an atomized mass of isolated citizens but as a totality of organized and discrete collectives. [3]

This classification is very typical of the confusion which bourgeois scholars consciously introduce into the question of the state. Starting with the fact that the concept of dictatorship is interpreted in the formal legal sense, deprived of all class content, the bourgeois jurist deliberately avoids the question: the dictatorship of which class and directed against whom ? He blurs the distinction between the dictatorship of a small group of exploiters and the dictatorship of the overwhelming majority of the working people; he distorts the concept of dictatorship, for he cannot avoid defining it without a relevant law or paragraph, while “the scientific concept of dictatorship means nothing less than power resting directly upon force, unlimited by laws, and unconstricted by absolute rules”. [4] Further it is sufficient to indicate, for instance, that under the latter heading the author includes: (a) a new type of state, never encountered before in history, where power belongs to the proletariat; (b) the reactionary dreams of certain professors and so-called guild socialists, about the return to the corporations and shops of the Middle Ages; and, finally (c) the fascist dictatorship of capital which Mussolini exercises in Italy.

This respected scholar consciously introduces confusion, consciously ignores the concrete historical conditions under which the working people actually can exercise administration of the state, acting as organized collectives. But such conditions are only the proletarian revolution and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

4. The class nature of law

Bourgeois science confuses the question of the essence of law no less than the question of the state. Here, Marxism-Leninism opposes the diverse majority of bourgeois, petit bourgeois and revisionist theories which, proceeding from the explanation of the historical and class nature of law, consider the state as a phenomenon essential to every human society. They thus transform law into a supra-historical category.

It is not surprising, therefore, that bourgeois philosophy of law serves as the main source for introducing confusion both into the concept of law and into the concept of state and society.

The bourgeois theory of the state is 90% the legal theory of the state. The unattractive class essence of the state, most often and most eagerly, is hidden by clever combinations of legal formalism, or else it is covered by a cloud of lofty philosophical legal abstractions.

The exposure of the class historical essence of law is not, therefore, an unimportant part of the Marxist-Leninist theory of society, of the state and of law.

The most widespread approach of bourgeois science to the solution of the question of the essence of law consists in the fact that it strives to embrace, through the concept of law, the existence of any consciously ordered human relationships, of any social rules, of any phenomenon of social authority or social power. Thus, bourgeois scholars easily transfer law to pre-class society, find it in the pre-state life of primitive tribes, and conclude that communism is unthinkable without law. They turn law as an empty abstraction into a universal concept devoid of historical content. Law, for bourgeois sociologists, becomes an empty form which is unconnected with concrete reality, with the relationships of production, with the antagonistic character of these relationships in class society, [and] with the presence of the state as a particular apparatus of power in the hands of the ruling class.

Representatives of idealist philosophy of law go still further. They begin with “the idea of law”, which stands above social history as something eternal, immutable and independent of space and time.

Here, for example, is the conclusion of one of the most important representatives of the ideological neo-Kantian philosophy of law – Stammler:

Through all the fates and deeds of man there extends a single unitary idea, the idea of law. All languages have a designation for this concept, and the direction of definitions and judgements expressed by it amount, upon careful study, to one and the same meaning.

Having made this discovery, it cost Stammler nothing “to prove” that regardless of the difference between the “life and activity of nations” and “the objects of legal consideration”, we observe the unity of the legal idea and its equal appearance and intervention.

This professorial rubbish is presented without the least attempt at factual proof In actuality it would be rather difficult to explain how this “unity of the legal idea and its equal appearance” gave birth to the laws of the Twelve Tablets of slave-owning Rome, the serf customs of the Middle Ages, the declarations of rights of capitalist democracies, and our Soviet Constitution.