Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Research Problem? Characteristics, Types, and Examples

A research problem is a gap in existing knowledge, a contradiction in an established theory, or a real-world challenge that a researcher aims to address in their research. It is at the heart of any scientific inquiry, directing the trajectory of an investigation. The statement of a problem orients the reader to the importance of the topic, sets the problem into a particular context, and defines the relevant parameters, providing the framework for reporting the findings. Therein lies the importance of research problem s.

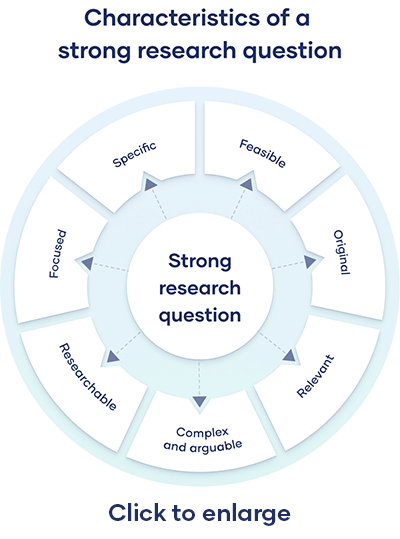

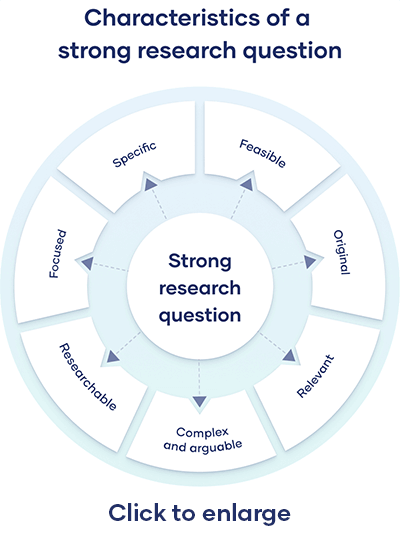

The formulation of well-defined research questions is central to addressing a research problem . A research question is a statement made in a question form to provide focus, clarity, and structure to the research endeavor. This helps the researcher design methodologies, collect data, and analyze results in a systematic and coherent manner. A study may have one or more research questions depending on the nature of the study.

Identifying and addressing a research problem is very important. By starting with a pertinent problem , a scholar can contribute to the accumulation of evidence-based insights, solutions, and scientific progress, thereby advancing the frontier of research. Moreover, the process of formulating research problems and posing pertinent research questions cultivates critical thinking and hones problem-solving skills.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Problem ?

Before you conceive of your project, you need to ask yourself “ What is a research problem ?” A research problem definition can be broadly put forward as the primary statement of a knowledge gap or a fundamental challenge in a field, which forms the foundation for research. Conversely, the findings from a research investigation provide solutions to the problem .

A research problem guides the selection of approaches and methodologies, data collection, and interpretation of results to find answers or solutions. A well-defined problem determines the generation of valuable insights and contributions to the broader intellectual discourse.

Characteristics of a Research Problem

Knowing the characteristics of a research problem is instrumental in formulating a research inquiry; take a look at the five key characteristics below:

Novel : An ideal research problem introduces a fresh perspective, offering something new to the existing body of knowledge. It should contribute original insights and address unresolved matters or essential knowledge.

Significant : A problem should hold significance in terms of its potential impact on theory, practice, policy, or the understanding of a particular phenomenon. It should be relevant to the field of study, addressing a gap in knowledge, a practical concern, or a theoretical dilemma that holds significance.

Feasible: A practical research problem allows for the formulation of hypotheses and the design of research methodologies. A feasible research problem is one that can realistically be investigated given the available resources, time, and expertise. It should not be too broad or too narrow to explore effectively, and should be measurable in terms of its variables and outcomes. It should be amenable to investigation through empirical research methods, such as data collection and analysis, to arrive at meaningful conclusions A practical research problem considers budgetary and time constraints, as well as limitations of the problem . These limitations may arise due to constraints in methodology, resources, or the complexity of the problem.

Clear and specific : A well-defined research problem is clear and specific, leaving no room for ambiguity; it should be easily understandable and precisely articulated. Ensuring specificity in the problem ensures that it is focused, addresses a distinct aspect of the broader topic and is not vague.

Rooted in evidence: A good research problem leans on trustworthy evidence and data, while dismissing unverifiable information. It must also consider ethical guidelines, ensuring the well-being and rights of any individuals or groups involved in the study.

Types of Research Problems

Across fields and disciplines, there are different types of research problems . We can broadly categorize them into three types.

- Theoretical research problems

Theoretical research problems deal with conceptual and intellectual inquiries that may not involve empirical data collection but instead seek to advance our understanding of complex concepts, theories, and phenomena within their respective disciplines. For example, in the social sciences, research problem s may be casuist (relating to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience), difference (comparing or contrasting two or more phenomena), descriptive (aims to describe a situation or state), or relational (investigating characteristics that are related in some way).

Here are some theoretical research problem examples :

- Ethical frameworks that can provide coherent justifications for artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, especially in contexts involving autonomous decision-making and moral agency.

- Determining how mathematical models can elucidate the gradual development of complex traits, such as intricate anatomical structures or elaborate behaviors, through successive generations.

- Applied research problems

Applied or practical research problems focus on addressing real-world challenges and generating practical solutions to improve various aspects of society, technology, health, and the environment.

Here are some applied research problem examples :

- Studying the use of precision agriculture techniques to optimize crop yield and minimize resource waste.

- Designing a more energy-efficient and sustainable transportation system for a city to reduce carbon emissions.

- Action research problems

Action research problems aim to create positive change within specific contexts by involving stakeholders, implementing interventions, and evaluating outcomes in a collaborative manner.

Here are some action research problem examples :

- Partnering with healthcare professionals to identify barriers to patient adherence to medication regimens and devising interventions to address them.

- Collaborating with a nonprofit organization to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs aimed at providing job training for underserved populations.

These different types of research problems may give you some ideas when you plan on developing your own.

How to Define a Research Problem

You might now ask “ How to define a research problem ?” These are the general steps to follow:

- Look for a broad problem area: Identify under-explored aspects or areas of concern, or a controversy in your topic of interest. Evaluate the significance of addressing the problem in terms of its potential contribution to the field, practical applications, or theoretical insights.

- Learn more about the problem: Read the literature, starting from historical aspects to the current status and latest updates. Rely on reputable evidence and data. Be sure to consult researchers who work in the relevant field, mentors, and peers. Do not ignore the gray literature on the subject.

- Identify the relevant variables and how they are related: Consider which variables are most important to the study and will help answer the research question. Once this is done, you will need to determine the relationships between these variables and how these relationships affect the research problem .

- Think of practical aspects : Deliberate on ways that your study can be practical and feasible in terms of time and resources. Discuss practical aspects with researchers in the field and be open to revising the problem based on feedback. Refine the scope of the research problem to make it manageable and specific; consider the resources available, time constraints, and feasibility.

- Formulate the problem statement: Craft a concise problem statement that outlines the specific issue, its relevance, and why it needs further investigation.

- Stick to plans, but be flexible: When defining the problem , plan ahead but adhere to your budget and timeline. At the same time, consider all possibilities and ensure that the problem and question can be modified if needed.

Key Takeaways

- A research problem concerns an area of interest, a situation necessitating improvement, an obstacle requiring eradication, or a challenge in theory or practical applications.

- The importance of research problem is that it guides the research and helps advance human understanding and the development of practical solutions.

- Research problem definition begins with identifying a broad problem area, followed by learning more about the problem, identifying the variables and how they are related, considering practical aspects, and finally developing the problem statement.

- Different types of research problems include theoretical, applied, and action research problems , and these depend on the discipline and nature of the study.

- An ideal problem is original, important, feasible, specific, and based on evidence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it important to define a research problem?

Identifying potential issues and gaps as research problems is important for choosing a relevant topic and for determining a well-defined course of one’s research. Pinpointing a problem and formulating research questions can help researchers build their critical thinking, curiosity, and problem-solving abilities.

How do I identify a research problem?

Identifying a research problem involves recognizing gaps in existing knowledge, exploring areas of uncertainty, and assessing the significance of addressing these gaps within a specific field of study. This process often involves thorough literature review, discussions with experts, and considering practical implications.

Can a research problem change during the research process?

Yes, a research problem can change during the research process. During the course of an investigation a researcher might discover new perspectives, complexities, or insights that prompt a reevaluation of the initial problem. The scope of the problem, unforeseen or unexpected issues, or other limitations might prompt some tweaks. You should be able to adjust the problem to ensure that the study remains relevant and aligned with the evolving understanding of the subject matter.

How does a research problem relate to research questions or hypotheses?

A research problem sets the stage for the study. Next, research questions refine the direction of investigation by breaking down the broader research problem into manageable components. Research questions are formulated based on the problem , guiding the investigation’s scope and objectives. The hypothesis provides a testable statement to validate or refute within the research process. All three elements are interconnected and work together to guide the research.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

Simple Random Sampling: Definition, Methods, and Examples

What is a Case Study in Research? Definition, Methods, and Examples

- Thesis Action Plan New

- Academic Project Planner

Literature Navigator

Thesis dialogue blueprint, writing wizard's template, research proposal compass.

- Why students love us

- Why professors love us

- Rebels Blog (Free)

- Why we are different

- All Products

- Coming Soon

Identifying a Research Problem: A Step-by-Step Guide

Identifying a research problem is a crucial first step in the research process, serving as the foundation for all subsequent research activities. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of the steps involved in identifying a research problem, from understanding its essence to employing advanced strategies for refinement.

Key Takeaways

- Understanding the definition and importance of a research problem is essential for academic success.

- Exploring diverse sources such as literature reviews and consultations can help in formulating a solid research problem.

- A clear problem statement, aligned research objectives, and well-defined questions are crucial for a focused study.

- Evaluating the feasibility and potential impact of a research problem ensures its relevance and scope.

- Advanced strategies, including interdisciplinary approaches and technology utilization, can enhance the identification and refinement of research problems.

Understanding the Essence of Identifying a Research Problem

Defining the research problem.

A research problem is the focal point of any academic inquiry. It is a concise and well-defined statement that outlines the specific issue or question that the research aims to address. This research problem usually sets the tone for the entire study and provides you, the researcher, with a clear purpose and a clear direction on how to go about conducting your research.

Importance in Academic Research

It also demonstrates the significance of your research and its potential to contribute new knowledge to the existing body of literature in the world. A compelling research problem not only captivates the attention of your peers but also lays the foundation for impactful and meaningful research outcomes.

Initial Steps to Identification

To identify a research problem, you need a systematic approach and a deep understanding of the subject area. Below are some steps to guide you in this process:

- Conduct a thorough literature review to understand what has been studied before.

- Identify gaps in the existing research that could form the basis of your study.

- Consult with academic mentors to refine your ideas and approach.

Exploring Sources for Research Problem Identification

Literature review.

When you embark on the journey of identifying a research problem, a thorough literature review is indispensable. This process involves scrutinizing existing research to find literature gaps and unexplored areas that could form the basis of your research. It's crucial to analyze recent studies, seminal works, and review articles to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Existing Theories and Frameworks

The exploration of existing theories and frameworks provides a solid foundation for developing a research problem. By understanding the established models and theories, you can identify inconsistencies or areas lacking in depth which might offer fruitful avenues for research.

Consultation with Academic Mentors

Engaging with academic mentors is vital in shaping a well-defined research problem. Their expertise can guide you through the complexities of your field, offering insights into feasible research questions and helping you refine your focus. This interaction often leads to the identification of unique and significant research opportunities that align with current academic and industry trends.

Formulating the Research Problem

Crafting a clear problem statement.

To effectively address your research problem, start by crafting a clear problem statement . This involves succinctly describing who is affected by the problem, why it is important, and how your research will contribute to solving it. Ensure your problem statement is concise and specific to guide the entire research process.

Setting Research Objectives

Setting clear research objectives is crucial for maintaining focus throughout your study. These objectives should directly align with the problem statement and guide your research activities. Consider using a bulleted list to outline your main objectives:

- Understand the underlying factors contributing to the problem

- Explore potential solutions

- Evaluate the effectiveness of proposed solutions

Determining Research Questions

The formulation of precise research questions is a pivotal step in defining the scope and direction of your study. These questions should be directly derived from your research objectives and designed to be answerable through your chosen research methods. Crafting well-defined research questions will help you maintain a clear focus and avoid common pitfalls in the research process.

Evaluating the Scope and Relevance of the Research Problem

Feasibility assessment.

Before you finalize a research problem, it is crucial to assess its feasibility. Consider the availability of resources, time, and expertise required to conduct the research. Evaluate potential constraints and determine if the research problem can be realistically tackled within the given limitations.

Significance to the Field

Ensure that your research problem has a clear and direct impact on the field. It should aim to contribute to existing knowledge and address a real-world issue that is relevant to your academic discipline.

Potential Impact on Existing Knowledge

The potential impact of your research problem on existing knowledge cannot be understated. It should challenge, extend, or refine current understanding in a meaningful way. Consider how your research can add value to the existing body of work and potentially lead to significant advancements in your field.

Techniques for Refining the Research Problem

Narrowing down the focus.

To effectively refine your research problem, start by narrowing down the focus . This involves pinpointing the specific aspects of your topic that are most significant and ensuring that your research problem is not too broad. This targeted approach helps in identifying knowledge gaps and formulating more precise research questions.

Incorporating Feedback

Feedback is crucial in the refinement process. Engage with academic mentors, peers, and experts in your field to gather insights and suggestions. This collaborative feedback can lead to significant improvements in your research problem, making it more robust and relevant.

Iterative Refinement Process

Refinement should be seen as an iterative process, where you continuously refine and revise your research problem based on new information and feedback. This approach ensures that your research problem remains aligned with current trends and academic standards, ultimately enhancing its feasibility and relevance.

Challenges in Identifying a Research Problem

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them.

Identifying a research problem can be fraught with common pitfalls such as selecting a topic that is too broad or too narrow. To avoid these, you should conduct a thorough literature review and seek feedback from peers and mentors. This proactive approach ensures that your research question is both relevant and manageable.

Dealing with Ambiguity

Ambiguity in defining the research problem can lead to significant challenges down the line. Ensure clarity by operationalizing variables and explicitly stating the research objectives. This clarity will guide your entire research process, making it more structured and focused.

Balancing Novelty and Practicality

While it's important to address a novel issue in your research, practicality should not be overlooked. A research problem should not only contribute new knowledge but also be feasible and have clear implications. Balancing these aspects often requires iterative refinement and consultation with academic mentors to align your research with real-world applications.

Advanced Strategies for Identifying a Research Problem

Interdisciplinary approaches.

Embrace the power of interdisciplinary approaches to uncover unique and comprehensive research problems. By integrating knowledge from various disciplines, you can address complex issues that single-field studies might overlook. This method not only broadens the scope of your research but also enhances its applicability and depth.

Utilizing Technology and Data Analytics

Leverage technology and data analytics to refine and identify research problems with precision. Advanced tools like machine learning and big data analysis can reveal patterns and insights that traditional methods might miss. This approach is particularly useful in fields where large datasets are involved, or where real-time data integration can lead to more dynamic research outcomes.

Engaging with Industry and Community Needs

Focus on the needs of industry and community to ensure your research is not only academically sound but also practically relevant. Engaging with real-world problems can provide a rich source of research questions that are directly applicable and beneficial to society. This strategy not only enhances the relevance of your research but also increases its potential for impact.

Dive into the world of academic success with our 'Advanced Strategies for Identifying a Research Problem' at Research Rebels. Our expertly crafted guides and action plans are designed to simplify your thesis journey, transforming complex academic challenges into manageable tasks. Don't wait to take control of your academic future. Visit our website now to learn more and claim your special offer!

In conclusion, identifying a research problem is a foundational step in the academic research process that requires careful consideration and systematic approach. This guide has outlined the essential steps involved, from understanding the context and reviewing existing literature to formulating clear research questions. By adhering to these guidelines, researchers can ensure that their studies are grounded in a well-defined problem, enhancing the relevance and impact of their findings. It is crucial for scholars to approach this task with rigor and critical thinking to contribute meaningfully to the body of knowledge in their respective fields.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a research problem.

A research problem is a specific issue, inconsistency, or gap in knowledge that needs to be addressed through scientific inquiry. It forms the foundation of a research study, guiding the research questions, methodology, and analysis.

Why is identifying a research problem important?

Identifying a research problem is crucial as it determines the direction and scope of the study. It helps researchers focus their inquiry, formulate hypotheses, and contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

How do I identify a suitable research problem?

To identify a suitable research problem, start with a thorough literature review to understand existing research and identify gaps. Consult with academic mentors, and consider relevance, feasibility, and your own interests.

What are some common pitfalls in identifying a research problem?

Common pitfalls include choosing a problem that is too broad or too narrow, not aligning with existing literature, lack of originality, and failing to consider the practical implications and feasibility of the study.

Can technology help in identifying a research problem?

Yes, technology and data analytics can aid in identifying research problems by providing access to a vast amount of data, revealing patterns and trends that might not be visible otherwise. Tools like digital libraries and research databases are particularly useful.

How can I refine my research problem?

Refine your research problem by narrowing its focus, seeking feedback from peers and mentors, and continually reviewing and adjusting the problem statement based on new information and insights gained during preliminary research.

How to Begin Writing Your Thesis: A Step-by-Step Guide

Recognizing the symptoms of phd burnout, crafting the perfect introduction for your thesis, conquering the fear of failure in your dissertation, overcoming lack of motivation, stress, and anxiety while completing your master's thesis.

Demystifying Research: Understanding the Difference Between a Problem and a Hypothesis

Avoiding Procrastination Pitfalls: Bachelor Thesis Progress and Weekend Celebrations

How Do You Write a Hypothesis for a Research Paper? Step-by-Step Guide

How to Write a Thesis Fast: Tips and Strategies for Success

The Note-Taking Debate: Pros and Cons of Digital and Analog Methods

Thesis Action Plan

- Rebels Blog

- Blog Articles

- Terms and Conditions

- Payment and Shipping Terms

- Privacy Policy

- Return Policy

© 2024 Research Rebels, All rights reserved.

Your cart is currently empty.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Research Problem

Definition:

Research problem is a specific and well-defined issue or question that a researcher seeks to investigate through research. It is the starting point of any research project, as it sets the direction, scope, and purpose of the study.

Types of Research Problems

Types of Research Problems are as follows:

Descriptive problems

These problems involve describing or documenting a particular phenomenon, event, or situation. For example, a researcher might investigate the demographics of a particular population, such as their age, gender, income, and education.

Exploratory problems

These problems are designed to explore a particular topic or issue in depth, often with the goal of generating new ideas or hypotheses. For example, a researcher might explore the factors that contribute to job satisfaction among employees in a particular industry.

Explanatory Problems

These problems seek to explain why a particular phenomenon or event occurs, and they typically involve testing hypotheses or theories. For example, a researcher might investigate the relationship between exercise and mental health, with the goal of determining whether exercise has a causal effect on mental health.

Predictive Problems

These problems involve making predictions or forecasts about future events or trends. For example, a researcher might investigate the factors that predict future success in a particular field or industry.

Evaluative Problems

These problems involve assessing the effectiveness of a particular intervention, program, or policy. For example, a researcher might evaluate the impact of a new teaching method on student learning outcomes.

How to Define a Research Problem

Defining a research problem involves identifying a specific question or issue that a researcher seeks to address through a research study. Here are the steps to follow when defining a research problem:

- Identify a broad research topic : Start by identifying a broad topic that you are interested in researching. This could be based on your personal interests, observations, or gaps in the existing literature.

- Conduct a literature review : Once you have identified a broad topic, conduct a thorough literature review to identify the current state of knowledge in the field. This will help you identify gaps or inconsistencies in the existing research that can be addressed through your study.

- Refine the research question: Based on the gaps or inconsistencies identified in the literature review, refine your research question to a specific, clear, and well-defined problem statement. Your research question should be feasible, relevant, and important to the field of study.

- Develop a hypothesis: Based on the research question, develop a hypothesis that states the expected relationship between variables.

- Define the scope and limitations: Clearly define the scope and limitations of your research problem. This will help you focus your study and ensure that your research objectives are achievable.

- Get feedback: Get feedback from your advisor or colleagues to ensure that your research problem is clear, feasible, and relevant to the field of study.

Components of a Research Problem

The components of a research problem typically include the following:

- Topic : The general subject or area of interest that the research will explore.

- Research Question : A clear and specific question that the research seeks to answer or investigate.

- Objective : A statement that describes the purpose of the research, what it aims to achieve, and the expected outcomes.

- Hypothesis : An educated guess or prediction about the relationship between variables, which is tested during the research.

- Variables : The factors or elements that are being studied, measured, or manipulated in the research.

- Methodology : The overall approach and methods that will be used to conduct the research.

- Scope and Limitations : A description of the boundaries and parameters of the research, including what will be included and excluded, and any potential constraints or limitations.

- Significance: A statement that explains the potential value or impact of the research, its contribution to the field of study, and how it will add to the existing knowledge.

Research Problem Examples

Following are some Research Problem Examples:

Research Problem Examples in Psychology are as follows:

- Exploring the impact of social media on adolescent mental health.

- Investigating the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for treating anxiety disorders.

- Studying the impact of prenatal stress on child development outcomes.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to addiction and relapse in substance abuse treatment.

- Examining the impact of personality traits on romantic relationships.

Research Problem Examples in Sociology are as follows:

- Investigating the relationship between social support and mental health outcomes in marginalized communities.

- Studying the impact of globalization on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of gentrification in urban neighborhoods.

- Investigating the impact of family structure on social mobility and economic outcomes.

- Examining the effects of social capital on community development and resilience.

Research Problem Examples in Economics are as follows:

- Studying the effects of trade policies on economic growth and development.

- Analyzing the impact of automation and artificial intelligence on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Investigating the factors that contribute to economic inequality and poverty.

- Examining the impact of fiscal and monetary policies on inflation and economic stability.

- Studying the relationship between education and economic outcomes, such as income and employment.

Political Science

Research Problem Examples in Political Science are as follows:

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of political polarization and partisan behavior.

- Investigating the impact of social movements on political change and policymaking.

- Studying the role of media and communication in shaping public opinion and political discourse.

- Examining the effectiveness of electoral systems in promoting democratic governance and representation.

- Investigating the impact of international organizations and agreements on global governance and security.

Environmental Science

Research Problem Examples in Environmental Science are as follows:

- Studying the impact of air pollution on human health and well-being.

- Investigating the effects of deforestation on climate change and biodiversity loss.

- Analyzing the impact of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and food webs.

- Studying the relationship between urban development and ecological resilience.

- Examining the effectiveness of environmental policies and regulations in promoting sustainability and conservation.

Research Problem Examples in Education are as follows:

- Investigating the impact of teacher training and professional development on student learning outcomes.

- Studying the effectiveness of technology-enhanced learning in promoting student engagement and achievement.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to achievement gaps and educational inequality.

- Examining the impact of parental involvement on student motivation and achievement.

- Studying the effectiveness of alternative educational models, such as homeschooling and online learning.

Research Problem Examples in History are as follows:

- Analyzing the social and economic factors that contributed to the rise and fall of ancient civilizations.

- Investigating the impact of colonialism on indigenous societies and cultures.

- Studying the role of religion in shaping political and social movements throughout history.

- Analyzing the impact of the Industrial Revolution on economic and social structures.

- Examining the causes and consequences of global conflicts, such as World War I and II.

Research Problem Examples in Business are as follows:

- Studying the impact of corporate social responsibility on brand reputation and consumer behavior.

- Investigating the effectiveness of leadership development programs in improving organizational performance and employee satisfaction.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful entrepreneurship and small business development.

- Examining the impact of mergers and acquisitions on market competition and consumer welfare.

- Studying the effectiveness of marketing strategies and advertising campaigns in promoting brand awareness and sales.

Research Problem Example for Students

An Example of a Research Problem for Students could be:

“How does social media usage affect the academic performance of high school students?”

This research problem is specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular area of interest, which is the impact of social media on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on social media usage and academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because it addresses a current and important issue that affects high school students.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use various methods, such as surveys, interviews, and statistical analysis of academic records. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between social media usage and academic performance, which could help educators and parents develop effective strategies for managing social media use among students.

Another example of a research problem for students:

“Does participation in extracurricular activities impact the academic performance of middle school students?”

This research problem is also specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular type of activity, extracurricular activities, and its impact on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on students’ participation in extracurricular activities and their academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because extracurricular activities are an essential part of the middle school experience, and their impact on academic performance is a topic of interest to educators and parents.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use surveys, interviews, and academic records analysis. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between extracurricular activities and academic performance, which could help educators and parents make informed decisions about the types of activities that are most beneficial for middle school students.

Applications of Research Problem

Applications of Research Problem are as follows:

- Academic research: Research problems are used to guide academic research in various fields, including social sciences, natural sciences, humanities, and engineering. Researchers use research problems to identify gaps in knowledge, address theoretical or practical problems, and explore new areas of study.

- Business research : Research problems are used to guide business research, including market research, consumer behavior research, and organizational research. Researchers use research problems to identify business challenges, explore opportunities, and develop strategies for business growth and success.

- Healthcare research : Research problems are used to guide healthcare research, including medical research, clinical research, and health services research. Researchers use research problems to identify healthcare challenges, develop new treatments and interventions, and improve healthcare delivery and outcomes.

- Public policy research : Research problems are used to guide public policy research, including policy analysis, program evaluation, and policy development. Researchers use research problems to identify social issues, assess the effectiveness of existing policies and programs, and develop new policies and programs to address societal challenges.

- Environmental research : Research problems are used to guide environmental research, including environmental science, ecology, and environmental management. Researchers use research problems to identify environmental challenges, assess the impact of human activities on the environment, and develop sustainable solutions to protect the environment.

Purpose of Research Problems

The purpose of research problems is to identify an area of study that requires further investigation and to formulate a clear, concise and specific research question. A research problem defines the specific issue or problem that needs to be addressed and serves as the foundation for the research project.

Identifying a research problem is important because it helps to establish the direction of the research and sets the stage for the research design, methods, and analysis. It also ensures that the research is relevant and contributes to the existing body of knowledge in the field.

A well-formulated research problem should:

- Clearly define the specific issue or problem that needs to be investigated

- Be specific and narrow enough to be manageable in terms of time, resources, and scope

- Be relevant to the field of study and contribute to the existing body of knowledge

- Be feasible and realistic in terms of available data, resources, and research methods

- Be interesting and intellectually stimulating for the researcher and potential readers or audiences.

Characteristics of Research Problem

The characteristics of a research problem refer to the specific features that a problem must possess to qualify as a suitable research topic. Some of the key characteristics of a research problem are:

- Clarity : A research problem should be clearly defined and stated in a way that it is easily understood by the researcher and other readers. The problem should be specific, unambiguous, and easy to comprehend.

- Relevance : A research problem should be relevant to the field of study, and it should contribute to the existing body of knowledge. The problem should address a gap in knowledge, a theoretical or practical problem, or a real-world issue that requires further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem should be feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It should be realistic and practical to conduct the study within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem should be novel or original in some way. It should represent a new or innovative perspective on an existing problem, or it should explore a new area of study or apply an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem should be important or significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It should have the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Manageability : A research problem should be manageable in terms of its scope and complexity. It should be specific enough to be investigated within the available time and resources, and it should be broad enough to provide meaningful results.

Advantages of Research Problem

The advantages of a well-defined research problem are as follows:

- Focus : A research problem provides a clear and focused direction for the research study. It ensures that the study stays on track and does not deviate from the research question.

- Clarity : A research problem provides clarity and specificity to the research question. It ensures that the research is not too broad or too narrow and that the research objectives are clearly defined.

- Relevance : A research problem ensures that the research study is relevant to the field of study and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. It addresses gaps in knowledge, theoretical or practical problems, or real-world issues that require further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem ensures that the research study is feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It ensures that the research is realistic and practical to conduct within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem ensures that the research study is original and innovative. It represents a new or unique perspective on an existing problem, explores a new area of study, or applies an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem ensures that the research study is important and significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It has the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Rigor : A research problem ensures that the research study is rigorous and follows established research methods and practices. It ensures that the research is conducted in a systematic, objective, and unbiased manner.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and...

Appendix in Research Paper – Examples and...

Dissertation vs Thesis – Key Differences

Research Topics – Ideas and Examples

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to...

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE: A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps exist in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people]. Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it but simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to a the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something that needs to be investigated.

IV. Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be investigated. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and helps define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

V. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., perhaps there's a hospital in the community ten miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital, but it was conducted ten years ago]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; D'Souza, Victor S. "Use of Induction and Deduction in Research in Social Sciences: An Illustration." Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (1982): 655-661; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question. The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question. [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- How To Formulate A Research Problem

Introduction

In the dynamic realm of academia, research problems serve as crucial stepping stones for groundbreaking discoveries and advancements. Research problems lay the groundwork for inquiry and exploration that happens when conducting research. They direct the path toward knowledge expansion.

In this blog post, we will discuss the different ways you can identify and formulate a research problem. We will also highlight how you can write a research problem, its significance in guiding your research journey, and how it contributes to knowledge advancement.

Understanding the Essence of a Research Problem

A research problem is defined as the focal point of any academic inquiry. It is a concise and well-defined statement that outlines the specific issue or question that the research aims to address. This research problem usually sets the tone for the entire study and provides you, the researcher, with a clear purpose and a clear direction on how to go about conducting your research.

There are two ways you can consider what the purpose of your research problem is. The first way is that the research problem helps you define the scope of your study and break down what you should focus on in the research. The essence of this is to ensure that you embark on a relevant study and also easily manage it.

The second way is that having a research problem helps you develop a step-by-step guide in your research exploration and execution. It directs your efforts and determines the type of data you need to collect and analyze. Furthermore, a well-developed research problem is really important because it contributes to the credibility and validity of your study.

It also demonstrates the significance of your research and its potential to contribute new knowledge to the existing body of literature in the world. A compelling research problem not only captivates the attention of your peers but also lays the foundation for impactful and meaningful research outcomes.

Identifying a Research Problem

To identify a research problem, you need a systematic approach and a deep understanding of the subject area. Below are some steps to guide you in this process:

- Conduct a Literature Review: Before you dive into your research problem, ensure you get familiar with the existing literature in your field. Analyze gaps, controversies, and unanswered questions. This will help you identify areas where your research can make a meaningful contribution.

- Consult with Peers and Mentors: Participate in discussions with your peers and mentors to gain insights and feedback on potential research problems. Their perspectives can help you refine and validate your ideas.

- Define Your Research Objectives: Clearly outline the objectives of your study. What do you want to achieve through your research? What specific outcomes are you aiming for?

Formulating a Research Problem

Once you have identified the general area of interest and specific research objectives, you can then formulate your research problem. Things to consider when formulating a research problem:

- Clarity and Specificity: Your research problem should be concise, specific, and devoid of ambiguity. Avoid vague statements that could lead to confusion or misinterpretation.

- Originality: Strive to formulate a research problem that addresses a unique and unexplored aspect of your field. Originality is key to making a meaningful contribution to the existing knowledge.

- Feasibility: Ensure that your research problem is feasible within the constraints of time, resources, and available data. Unrealistic research problems can hinder the progress of your study.

- Refining the Research Problem: It is common for the research problem to evolve as you delve deeper into your study. Don’t be afraid to refine and revise your research problem if necessary. Seek feedback from colleagues, mentors, and experts in your field to ensure the strength and relevance of your research problem.

How Do You Write a Research Problem?

Steps to consider in writing a Research Problem:

- Select a Topic: The first step in writing a research problem is to select a specific topic of interest within your field of study. This topic should be relevant, and meaningful, and have the potential to contribute to existing knowledge.

- Conduct a Literature Review: Before formulating your research problem, conduct a thorough literature review to understand the current state of research on your chosen topic. This will help you identify gaps, controversies, or areas that need further exploration.

- Identify the Research Gap: Based on your literature review, pinpoint the specific gap or problem that your research aims to address. This gap should be something that has not been adequately studied or resolved in previous research.

- Be Specific and Clear: The research problem should be framed in a clear and concise manner. It should be specific enough to guide your research but broad enough to allow for meaningful investigation.

- Ensure Feasibility: Consider the resources and constraints available to you when formulating the research problem. Ensure that it is feasible to address the problem within the scope of your study.

- Align your Research Goals: The research problem should align with the overall goals and objectives of your study. It should be directly related to the research questions you intend to answer.

Related: How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Research Problem vs Research Questions

Research Problem: The research problem is a broad statement that outlines the overarching issue or gap in knowledge that your research aims to address. It provides the context and motivation for your study and helps establish its significance and relevance. The research problem is typically stated in the introduction section of your research proposal or thesis.

Research Questions: Research questions are specific inquiries that you seek to answer through your research. These questions are derived from the research problem and help guide the focus of your study. They are often more detailed and narrow in scope compared to the research problem. Research questions are usually listed in the methodology section of your research proposal or thesis.

Difference Between a Research Problem and a Research Topic

Research Problem: A research problem is a specific issue, gap, or question that requires investigation and can be addressed through research. It is a clearly defined and focused problem that the researcher aims to solve or explore. The research problem provides the context and rationale for the study and guides the research process. It is usually stated as a question or a statement in the introduction section of a research proposal or thesis.

Example of a Research Problem: “ What are the factors influencing consumer purchasing decisions in the online retail industry ?”

Research Topic: A research topic, on the other hand, is a broader subject or area of interest within a particular field of study. It is a general idea or subject that the researcher wants to explore in their research. The research topic is more general and does not yet specify a specific problem or question to be addressed. It serves as the starting point for the research, and the researcher further refines it to formulate a specific research problem.

Example of a Research Topic: “ Consumer behavior in the online retail industry.”

In summary, a research topic is a general area of interest, while a research problem is a specific issue or question within that area that the researcher aims to investigate.

Difference Between a Research Problem and Problem Statement

Research Problem: As explained earlier, a research problem is a specific issue, gap, or question that you as a researcher aim to address through your research. It is a clear and concise statement that defines the focus of the study and provides a rationale for why it is worth investigating.

Example of a Research Problem: “What is the impact of social media usage on the mental health and well-being of adolescents?”

Problem Statement: The problem statement, on the other hand, is a brief and clear description of the problem that you want to solve or investigate. It is more focused and specific than the research problem and provides a snapshot of the main issue being addressed.

Example of a Problem Statement: “ The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between social media usage and the mental health outcomes of adolescents, with a focus on depression, anxiety, and self-esteem.”

In summary, a research problem is the broader issue or question guiding the study, while the problem statement is a concise description of the specific problem being addressed in the research. The problem statement is usually found in the introduction section of a research proposal or thesis.

Challenges and Considerations

Formulating a research problem involves several challenges and considerations that researchers should carefully address:

- Feasibility: Before you finalize a research problem, it is crucial to assess its feasibility. Consider the availability of resources, time, and expertise required to conduct the research. Evaluate potential constraints and determine if the research problem can be realistically tackled within the given limitations.

- Novelty and Contribution: A well-crafted research problem should aim to contribute to existing knowledge in the field. Ensure that your research problem addresses a gap in the literature or provides innovative insights. Review past studies to understand what has already been done and how your research can build upon or offer something new.

- Ethical and Social Implications: Take into account the ethical and social implications of your research problem. Research involving human subjects or sensitive topics requires ethical considerations. Consider the potential impact of your research on individuals, communities, or society as a whole.

- Scope and Focus: Be mindful of the scope of your research problem. A problem that is too broad may be challenging to address comprehensively, while one that is too narrow might limit the significance of the findings. Strike a balance between a focused research problem that can be thoroughly investigated and one that has broader implications.

- Clear Objectives: Ensure that your research problem aligns with specific research objectives. Clearly define what you intend to achieve through your study. Having well-defined objectives will help you stay on track and maintain clarity throughout the research process.

- Relevance and Significance: Consider the relevance and significance of your research problem in the context of your field of study. Assess its potential implications for theory, practice, or policymaking. A research problem that addresses important questions and has practical implications is more likely to be valuable to the academic community and beyond.

- Stakeholder Involvement: In some cases, involving relevant stakeholders early in the process of formulating a research problem can be beneficial. This could include experts in the field, practitioners, or individuals who may be impacted by the research. Their input can provide valuable insights that can help you enhance the quality of the research problem.

In conclusion, understanding how to formulate a research problem is fundamental for you to have meaningful research and intellectual growth. Remember that a well-crafted research problem serves as the foundation for groundbreaking discoveries and advancements in various fields. It not only enhances the credibility and relevance of your study but also contributes to the expansion of knowledge and the betterment of society.

Therefore, put more effort into the process of identifying and formulating research problems with enthusiasm and curiosity. Engage in comprehensive literature reviews, observe your surroundings, and reflect on the gaps in existing knowledge. Lastly, don’t forget to be mindful of the challenges and considerations, and ensure your research problem aligns with clear objectives and ethical principles.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- problem statements

- research objectives

- research problem vs research topic

- research problems

- research studies

You may also like:

Naive vs Non Naive Participants In Research: Meaning & Implications

Introduction In research studies, naive and non-naive participant information alludes to the degree of commonality and understanding...

How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Learn how to write problem statements before commencing any research effort. Learn about its structure and explore examples

Defining Research Objectives: How To Write Them

Almost all industries use research for growth and development. Research objectives are how researchers ensure that their study has...

Sources of Data For Research: Types & Examples

Introduction In the age of information, data has become the driving force behind decision-making and innovation. Whether in business,...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Developing a Research Problem

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- Phyllis G. Supino EdD 3 &

- Helen Ann Brown Epstein MLS, MS, AHIP 4

5879 Accesses

A well-designed research project, in any discipline, begins with conceptualizing the problem.