5 Common Thesis Crises and How to Overcome Them

Writing a research project, thesis or dissertation is a colossal task. However, it can be accomplished if one exercises discipline and hones their organizational skills. I strongly advise my student clients to categorise and collate all aspects of their research from the beginning of their project; leaving sufficient time for vital complementary responsibilities such as formatting, proofreading, and editing. Even the best-laid plans can veer off course. Few students get through the year without at least one or two significant hiccups and some end up facing a personal or professional crisis whilst working towards the looming submission deadline.

In my experience, as an academic performance coach, I’ve navigated these crises alongside my students. I’ve seen some major, and in some instances, multiple, obstacles overcome by students. What’s the secret? Tenacity. That saying, “When times get tough, the tough get going,” has never been more true than when I’ve worked with students who have to make difficult decisions in order to realise their graduation dream.

Here are five common potential crises that occur during the thesis component of your qualification and how you too can take control and graduate on time.

1. Supervisor Issues

Whether your supervisor is AWOL or overbearing, the key to solving this problem is clear, firm and professional communication. Take the initiative to set up meetings. Arrive prepared and on time. Make use of technology to facilitate meetings by using digital calendars and online platforms for meetings.

Together with regular meetings, it is vital that you open up to your supervisor about challenges with your research or anything else that may be hindering your progress. Showing that you have doubts or concerns or asking for help are not signs of weakness but a conscious decision to want to succeed.

- Identify where you need training or help.

- Share your concerns about where your project is and where it is going.

- Ask about techniques, resources and recommended reading which could help.

Remember to be realistic with your demands and expectations. Supervisors are busy academics and researchers, often juggling teaching, research, pastoral, administrative, and family roles.

2. Traumatic Life Events

Psychologists have identified death/birth, divorce, moving house and a change in financial circumstances as dominant stress-inducing life events. This year, 2020, we can add living through a pandemic to this list. On a superficial level, lockdown seems like the perfect time to knuckle down and get the writing done. But lockdown comes with its own set of challenges: spouses and children at home, homeschooling kids, financial stress, adjusting to working from home – to name just a few. If you experience a traumatic turn of events in your life do not assume you can simply stick to your original plan – that is just setting yourself up for failure. Instead, review and adjust your plan. Speak to your supervisor and acknowledge the problems you are experiencing. The quicker you adjust your strategy, the better chance of success you’ll have.

3. Poor Planning and Under Preparation

Talking about how you will spend two hours a day working on your thesis does not constitute having a plan. Many postgrads have jobs, families and social lives to juggle. Thinking you can simply add researching and writing a thesis on top of all that is naive and short-sighted. You will have to review your day to day, week by week activities and commitments, and adjust your schedule accordingly.

Part of your preparation should be directed at putting the necessary measures in place to prevent data loss. I cannot stress this enough: back up your work. Use Google Drive or other cloud storage solutions to save your work. You could even email yourself every day’s work so that you have a copy of it if your computer breaks. You’ll save yourself a lot of stress knowing you have your work saved in another location.

Making time for your academic work will mean making sacrifices. In my experience, the students who accept that sacrifice is necessary and get all their stakeholders on board with those sacrifices are the ones who get the job done. And, without causing animosity at home/work or succumbing to feelings of guilt. Remember, these are calculated sacrifices with a real reward at the end.

Here are examples of the types of sacrifices that have proved to pay off:

- Asking the spouse to take over some of the parenting responsibilities such as driving the kids to extra-mural activities.

- Asking for accumulated/unpaid leave from the employer.

- Giving up recurring social activities such as book clubs.

- Saying no to invitations unless the emotional and relationship pay off is worth it.

Creating, negotiating and navigating a workable plan is not easy. I highly recommend engaging with a coach to assist you. In my practice, students make a PACT: Personal Action Commitment Timetable as part of their process. The confidence they derive from having a solid and realistic plan in place has proven to be priceless.

4. Toxic Work Environment

While the space you choose to work in does not have to look like something from a magazine, it doesn’t hurt to take some time to tidy up and make your space organised and comfortable. Get rid of the clutter. A clean desk means fewer distractions. It should be a space that does not stress you out as you will spend a significant amount of time there. You must want to be in your space, it must invite you in:

- A quiet space.

- A stable internet connection.

- Plenty of wall plugs.

- An ergonomically designed chair for comfort and support.

- Natural light.

- Perhaps a piece of art, a carpet, or a plant for inspiration & company.

I have found that a spot of greenery, like a plant (even a cactus will do!). An image that makes you happy will not go amiss.

Aside from the room itself, it’s vital that you have the necessary tools to perform the task. Any computer hardware or software is important. Invest in these. And, invest in the time to learn your products so you don’t get sidetracked with them at a later stage.

5. Confidence and Motivation

Self-doubt often manifests as imposter syndrome during the thesis year, usually when you feel that you are too far behind to catch up and finish on time. While it is ‘normal’ to have doubts, if your state of mind is so negative that it’s debilitating, you should immediately talk to your coach or supervisor to gain some perspective and help you navigate the crisis to get back on track. You would not be in the post-graduate programme if the institution and its staff did not believe you were capable of passing.

Motivation is another common problem. Performing research and writing the necessary reports is a discipline. Believe me when I say, motivation is your fickle friend who only shows up when the sun is shining. You have to learn: do not rely on motivation to get you to sit down and put in the hours. Get your bum in your chair and write.

You do not have to be motivated to pass your course, you need to be disciplined.

Show up for thesis writing every day, as you promised yourself, and success will follow.

The Confounder

News, updates, and information for current students and alumni of the Department of Epidemiology at Rollins School of Public Health

The Struggles of Writing a Thesis

- January 17, 2022

Category : PROspective

Getting an MPH or PhD in Epidemiology on its own is no easy feat. Add in jobs, APEs, covid, and any kind of personal life and it can sometimes feel like you’re drowning in responsibilities and expectations. For second year master’s students, as we enter our final semester, we are also faced with the massive obstacle of completing a thesis or capstone. As I’ve seen countless peers, like myself, struggling to work on their thesis recently I thought I would share some of my own struggles and the things that have made them a bit easier, in the hopes of making someone else feel a little less alone.

Take a break . This past week I spent almost an entire day struggling to find an answer to a question I wasn’t even sure I understood. After agonizing over tables and DAGs but accomplishing nothing for hours I decided to take a break and go on a short hike near my apartment. Getting away from my computer, experiencing some nature, and getting some activity outside of the 30 foot walk from my desk to the kitchen saved my mental health, and reminded me that I don’t have to figure out the answer to every question on my own. Sometimes, giving your brain some time to reset may be just what you need.

On that note, talk to your advisor ! Or at least a professor that can help you answer those hard questions you just can’t figure out. As much as we’ve learned in our classes over the past year and a half, there is still much to be learned in the field of public health that can only come from experience. Our professors, advisors, supervisors, and even our peers can offer insight into a problem we may have never considered. Having someone to go over ideas with or ask questions to has made this process so much easier for me, which is the point! Just remember, you’re not going through this alone.

Ask someone to hold you accountable. When I initially created the outline of my thesis, I thought the deadlines I set for myself to complete various parts were doable. Now that I’ve adjusted those deadlines 3 or more times I laugh at my early optimism. If you, like me, are slow to complete any task without external pressure then maybe you can relate. Telling someone else– your thesis advisor, a friend, or even a parent– when you plan to complete each section may help you hold yourself accountable and finally put in the work you know you’re capable of.

Create an inviting workspace. I’m someone who is easily distracted and who often finds any excuse not to do my work (hence writing this article instead of my thesis). That’s why spending the majority of my time working on the couch in my living room was not cutting it for me. I recently revamped my study space and I cannot emphasize how big of a difference it has made. Having a desk chair that is actually comfortable to sit in is a big enough enticement to forgo working on the couch, where a roommate, TV, and kitchen are all within easy access to help me ignore my responsibilities. Moving a lamp by my desk to get better lighting has also given the space a cozier feel. While I’m still battling temptations like my bed and social media, having a comfortable, clutter-free, and inviting study space has definitely helped ease some stress and increase my productivity. If you want to make your desk more inviting consider adding a plant, candle, or even hanging a picture over it to add a little positivity to your workspace.

Ultimately, we’re entering a period that has so much stress and uncertainty. Figuring out post-graduation plans while reconciling that for many, this is your last semester of school EVER is hard enough without rising covid cases, returning to online learning, and the exhaustion of surviving through two years of a global pandemic. Be gentle with yourself and give yourself grace. You and your thesis don’t have to be perfect. And remember that if there’s something you can do that would add even a little bit of joy to your life in this uneasy time, it’s probably worth it.

Featured Image by nikko macaspac on Unsplash

Definitely needed to read this! Thank you!

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Recent Posts

- TA Positions Available, Center for the Study of Human Health

- Epidemiologist 2, Tennessee Department of Health

- Scholarship Opportunities, Association for Environmental Health & Sciences Foundation

- Registration Open, CDC Workshop on Applied Epidemiology and Environmental Health

- Molecular Epidemiologic Research Postdoctoral Fellowship

Upcoming Events

- The Summer Institute in Statistics and Modeling in Infectious Diseases (SISMID) July 15, 2024 – July 31, 2024 Conference / Symposium Event Type: Conference / SymposiumSeries: The Summer Institute in Statistics and Modeling in Infectious Diseases (SISMID)Speaker: Leaders in the FieldContact Name: Pia ValerianoContact Email: [email protected]: https://sph.emory.edu/SISMID/index.htmlThe Summer Institute in Statistics and Modeling in Infectious Diseases (SISMID) is designed to introduce infectious disease researchers to modern methods of statistical analysis and mathematical modeling.

- Functional Biomarkers for Early Detection and Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy August 5, 2024 at 12:00 pm – 1:00 pm Zoom Online Location: ZoomSeries: EGDRC Seminar SeriesSpeaker: Dr. Machelle PardueContact Name: Wendy GillContact Email: [email protected]: https://tinyurl.com/Machelle-PardueDr. Pardue’s lab is focused on clinically relevant treatments for retinal disease that can make a difference in the quality of life of patients. She is developing novel screening and treatment strategies for early-stage diabetic retinopathy and elucidating the retinoscleral mechanisms…

- The Second Annual RSPH Staff and Post-Doctoral Ice Cream Social August 14, 2024 at 1:00 pm – 2:00 pm Networking and Special Event Event Type: Networking,Special EventContact Name: Staff CouncilContact Email: [email protected] Location: RRR_Terrace 2nd FloorRSPH staff and post-docs are invited to join us for ice cream and delightful conversation. This event is hosted by the RSPH Staff Council.

Follow Us on Social Media:

Recent Comments

- Erica Schipper on Student Position Available, WellRoot

- Haritha Dhamodharan on Student Position Available, WellRoot

- Connie on 8 Books Every Epidemiologist Should Read

- Riley on #WeAreEmoryEPI: Meet Ellisen Herndon

- Erica Schipper on Epidemiology Graduate Intern, Johnson & Johnson

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

- News/Events

- #WeAreEmoryEPI

- PROspective

- Recent Publications

- Tricks and Treats with the Council, hosted by the RSPH Staff Council October 31, 2024 at 10:00 am – 11:30 am Networking and Special Event Event Type: Networking,Special EventContact Name: Staff CouncilContact Email: [email protected] Location: CNR_8030 Lawrence P. &Ann Estes Klamon roomRSPH staff and post-docs are invited to join the RSPH Staff Council for a festive gathering featuring sweet treats and refreshments. Costumes are encouraged but not required.

Epidemiology Department Rollins School of Public Health

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

Mitigating the Challenges of Thesis Writing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Autoethnographic Reflection of Two Doctoral Students’ Perezhivanie

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Jennifer Cutri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5328-5332 4 &

- Ricky W. K. Lau ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2340-2366 5

987 Accesses

4 Citations

3 Altmetric

Undertaking a doctoral degree is a challenging but worthwhile endeavour where PhD students invest years of academic, physical, and emotional energy contributing to their specialist field. The emotional toll upon doctoral students’ wellbeing has been highlighted in recent years. More recently, another issue has impacted PhD students—the COVID-19 pandemic. While emerging research has highlighted doctoral students’ struggles and coping mechanisms, we offer our experience as two PhD students navigating our ways through the unknown terrain of doctoral study as a couple during a pandemic. With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, we were forced to retreat from our allocated offices at the university and write together within the same vicinity at home during the sudden lockdown. During this time, we found that even though writing a thesis was stressful and our future was uncertain due to the pandemic, we found comfort and solace in each other. Writing together, in isolation, has brought us together. As we are in different disciplines—Medicine and Education, we also learnt how to approach our theses from different perspectives and became more resilient in our development as researchers. We discuss how our research backgrounds influenced the way we experienced academia and what we learnt from each other. We employ Vygotsky’s term of perezhivanie to capture our emotional journey and academic development together to represent the unique environmental conditions experienced.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

I Can’t Complain

My PhD Life, and Connecting the Dots Between Here and There…

Anxiety, Desire, Doubt, and Joy: The Dualities of a Latin American Emerging Researcher during Academic Writing Processes

Blunden, A. (2016). Translating perezhivanie into English. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 23 (4), 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2016.1186193

Article Google Scholar

Blunden, A. (2021). Chapter 25: The coronavirus pandemic is a world perezhivanie. In A. Blunden (Ed.), Hegel, Marx and Vygotsky (pp. 402–406). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004470972_027

Boaz, J. (2021, October 3). Melbourne passes Buenos Aires’ world record for time spent in COVID-19 lockdown . ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-03/melbourne-longest-lockdown/100510710

Börgeson, E., Sotak, M., Kraft, J., Bagunu, G., Biörserud, C., & Lange, S. (2021). Challenges in PhD education due to COVID-19 - disrupted supervision or business as usual: A cross-sectional survey of Swedish biomedical sciences graduate students. BMC Medical Education, 21 , Article 294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02727-3

Bozhovich, L. I. (2009). The social situation of child development. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 47 (4), 59–86. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-0405470403

Byrom, N. (2020). COVID-19 and the research community: The challenges of lockdown for early-career researchers. eLife, 9 , Article e59634. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.59634

Cahusac de Caux, B. (2022a). The effects of the pandemic on the research output and strategies of early career researchers and doctoral candidates. In B. Cahusac de Caux, L. Pretorius, & L. Macaulay (Eds.), Research and teaching in a pandemic world: The challenges of establishing academic identities during times of crisis . Springer.

Google Scholar

Cahusac de Caux, B. (2022b). Introduction to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on academia. In B. Cahusac de Caux, L. Pretorius, & L. Macaulay (Eds.), Research and teaching in a pandemic world: The challenges of establishing academic identities during times of crisis . Springer.

Cross, R. (2012). Creative in finding creativity in the curriculum: The CLIC second language classroom. Australian Education Research, 39 (4), 431–445. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ984464

Dang, T. K. A. (2013). Identity in activity: Examining teacher professional identity formation in the paired-placement of student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 30 , 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.10.006

Davis, S. (2021). Perezhivanie, art, and creative traversal: A method of marking and moving through COVID and grief. Qualitative Inquiry, 27 (7), 767–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420960158

Davis, S., & Phillips, L. G. (2020). Teaching during COVID 19 times – The experiences of drama and performing arts teachers and the human dimensions of learning. NJ, 44 (2), 66–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/14452294.2021.1943838

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, 36 (4), 273–290. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23032294

Esteban-Guitart, M., & Moll, L. C. (2014a). Funds of identity: A new concept based on the funds of knowledge approach. Culture & Psychology, 20 (1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13515934

Esteban-Guitart, M., & Moll, L. C. (2014b). Lived experience, funds of identity and education. Culture & Psychology, 20 (1), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13515940

Etmanski, B. (2019). The prospective shift away from academic career aspirations. Higher Education, 77 , 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0278-6

Evans, T., Bira, L., Gastelum, J., Weiss, L., & Vanderford, N. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36 (3), 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089

Ferholt, B. (2010). A synthetic-analytic method for the study of perezhivanie: Vygotsky’s literary analysis applied to playworlds. In M. C. Connery, V. P. John-Steiner, & A. Marjanovic-Shane (Eds.), Vygotsky and creativity: A cultural-historical approach to play, meaning making, and the arts (pp. 163–179). Peter Lang.

Fleer, M., González Rey, F., & Veresov, N. (2017). Perezhivanie, emotions and subjectivity: Setting the stage. In M. Fleer, F. González Rey, & N. Veresov (Eds.), Perezhivanie, emotions and subjectivity: Advancing Vygotsky’s legacy (pp. 1–15). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4534-9_1

Freya, A., & Cutri, J. (2022). “Memeing it up!”: Doctoral students’ reflections of collegiate virtual writing spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic. In B. Cahusac de Caux, L. Pretorius, & L. Macaulay (Eds.), Research and teaching in a pandemic world: The challenges of establishing academic identities during times of crisis . Springer.

Ghaffarzadegan, N., Hawley, J., & Desai, A. (2014). Research workforce diversity: The case of balancing national versus international postdocs in US biomedical research. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 31 (2), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2190

Ghebreyesus, T. A. (2020). WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID19–11 March 2020 . World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020

González Rey, F. (2016). Vygotsky’s concept of perezhivanie in the psychology of art and at the final moment of his work: Advancing his legacy. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 23 (4), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2016.1186196

Haas, N., Gureghian, A., Jusino Díaz, C., & Williams, A. (2022). Through their own eyes: The implications of COVID-19 for PhD students. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 9 (1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.34

Holman Jones, S., Adams, T. E., & Ellis, C. (2016). Coming to know autoethnography as more than a method. In S. Holman Jones, T. E. Adams, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 17–47). Routledge.

Hradsky, D., Soyoof, A., Zeng, S., Foomani, E. M., Lem, N. C., Maestre, J.-L., & Pretorius, L. (2022). Pastoral care in doctoral education: A collaborative autoethnography of belonging and academic identity. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 17 , 1–23. https://doi.org/10.28945/4900

Iaroshevskii, M. G. (1997). Experience and the drama of the development of personality: LS Vygotskii’s last word. Russian Studies in Philosophy, 36 (1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.2753/RSP1061-1967360170

Johnson, R. L., Coleman, R. A., Batten, N. H., Hallsworth, D., & Spencer, E. E. (2020). The quiet crisis of PhDs and COVID-19: Reaching the financial tipping point . Preprint. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-36330/v2

Kozulin, A. (1991). Psychology of experiencing: A Russian view. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 31 (3), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167891313003

Lau, R. W. K., & Pretorius, L. (2019). Intrapersonal wellbeing and the academic mental health crisis. In L. Pretorius, L. Macaulay, & B. Cahusac de Caux (Eds.), Wellbeing in doctoral education: Insights and guidance from the student experience (pp. 37–45). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9302-0_5

Leontiev, A. N. (2005). Study of the environment in the pedological works of L. S. Vygotsky: A critical study. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 43 (4), 8–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10610405.2005.11059254

Lockdown Stats Melbourne. (2021, November 6). Days in lockdown since the pandemic began . https://lockdownstats.melbourne/

Mason, M. A., Goulden, M., & Frasch, K. (2009). Why graduate students reject the fast track. Academe, 95 (1), 11–16. https://www.aaup.org/article/why-graduate-students-reject-fast-track/#.Ynpm1tpBw2w

Mitchell, M. (2016). Finding the “prism”: Understanding Vygotsky’s perezhivanie as an ontogenetic unit of child consciousness. International Research in Early Childhood Education, 7 (1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.4225/03/584fa3e2a9779

Neumann, R., & Tan, K. K. (2011). From PhD to initial employment: The doctorate in a knowledge economy. Studies in Higher Education, 36 (5), 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.594596

Poole, A., & Huang, J. (2018). Resituating funds of identity within contemporary interpretations of perezhivanie. Mind, Culture and Activity, 25 (2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2018.1434799

Pretorius, L. (2022). “I realised that, if I am dead, I cannot finish my PhD!”: A narrative ethnography of psychological capital in academia [Preprint]. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1868055/v2

Pretorius, L., & Cutri, J. (2019). Autoethnography: Researching personal experiences. In L. Pretorius, L. Macaulay, & B. Cahusac de Caux (Eds.), Wellbeing in doctoral education: Insights and guidance from the student experience (pp. 27–34). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9302-0_4

Pretorius, L., & Macaulay, L. (2021). Notions of human capital and academic identity in the PhD: Narratives of the disempowered. Journal of Higher Education, 92 (4), 623–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2020.1854605

Rafi, H. (2018). Natural spirituality as an educational process: An autoethnography . Doctoral Dissertation, Monash University. Figshare. Melbourne, Australia. https://figshare.com/articles/Natural_Spirituality_as_an_educational_process_An_autoethnography/6873857

Varshava, B., & Vygotsky, L. (1931). Psihologicheskii slovar [Psychological dictionary] . Gosudarstvennoye Uchebnopedagogicheskoye Publ.

Vasilyuk, F. (1992). The psychology of experiencing: The resolutions of life's critical situations . University Press.

Veresov, N. (2016a). Duality of categories or dialectical concepts? Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 50 (2), 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9327-1

Veresov, N. (2016b). Perezhivanie as a phenomenon and a concept: Questions on clarification and methodological meditations. Cultural-Historical Psychology, 12 (3), 129–148. https://psyjournals.ru/en/kip/2016/n3/veresov.shtml

Veresov, N. (2017). The concept of perezhivanie in cultural-historical theory: Content and contexts. In M. Fleer, F. González Rey, & N. Veresov (Eds.), Perezhivanie, emotions and subjectivity: Advancing Vygotsky’s legacy (pp. 47–70). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4534-9_3

Veresov, N. (2019). Subjectivity and perezhivanie: Empirical and methodological challenges and opportunities. In F. González Rey, A. Mitjáns Martínez, & D. Magalhães Goulart (Eds.), Subjectivity within cultural-historical approach (pp. 61–83). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3155-8_4

Vygotsky, L. S. (1994). The problem of the environment. In R. Van der Veer & J. Valsiner (Eds.), The Vygotsky reader . Blackwell.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1998). The collected works of LS Vygotsky: Child psychology (M. J. Hall, Trans.; R. W. Rieber, Ed. Vol. 5). Plenum Press.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their PhD supervisors for their ongoing support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Jennifer Cutri acknowledges the support from Dr. Clare Hall, Dr. Howard Prosser, and Dr. George Variyan which has resulted in her passing her final review milestone. Furthermore, Dr. Ricky Lau acknowledges the support of Prof. Sharon Ricardo, Dr. Pratibha Tripathi, and Dr. Yasuyuki Osanai for their support until his PhD completion.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Australian International School Hong Kong, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong, China

Jennifer Cutri

Centre for Translational Stem Cell Biology, Hong Kong, China

Ricky W. K. Lau

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jennifer Cutri .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

American University of the Middle East, Egaila, Kuwait

Basil Cahusac de Caux

Faculty of Education, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

Lynette Pretorius

CREATE, Deakin University, Burwood, VIC, Australia

Luke Macaulay

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cutri, J., Lau, R.W.K. (2022). Mitigating the Challenges of Thesis Writing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Autoethnographic Reflection of Two Doctoral Students’ Perezhivanie . In: Cahusac de Caux, B., Pretorius, L., Macaulay, L. (eds) Research and Teaching in a Pandemic World. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-7757-2_17

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-7757-2_17

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-7756-5

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-7757-2

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The 10 crises of the PhD thesis - and how to overcome them

Is your doctoral thesis in jeopardy? Do you want to give it all up? Even though you have been working on it for several months or even years? Then you must be suffering from one of ten dissertation crises. These tips will help you to overcome them fast!

1. The focus crisis of the dissertation

Problem: I cannot narrow my research question enough.

- Find models, especially graphic ones, and build on them.

- Brainstorm the relevant factors.

- Build your own model using the research question.

- Keep improving your model (by iteration).

- Talk your supervisor through the model.

- Consider the current status as the CONCLUSION of the first phase. Take an inventory and start working on the second big phase, your dissertation 2.0 so to speak.

2. The status quo crisis of the dissertation

Problem: Every author writes something different. So what?

- Follow the most recognized experts. They have several published works on the subject and which are usually the most frequently quoted. In addition, they have the most studies and most cited studies on the subject.

- These author’s arguments should be the most obvious to you.

- Create a thorough literature review with the Review Matrix. Then you’ll have the overview.

3. The data crisis of the dissertation

Problem: How can I finally collect the data I need?

Find useful answers to these questions:

- Who has what data?

- Where can I find the people with the data?

- How do I address them?

- What is a good plan to get the data?

4. The Citavi crisis of the dissertation

Problem: You found so many useful arguments in articles... And all are nicely stored in Citavi… How do I write a compelling text that incorporates everything I’ve read?

- Make the outline as detailed as possible. Follow our sample outline for a dissertation.

- Assign the passages from the sources to the chapters.

- Set dates = deadlines (no more than 3-5 days!)

- Analyze chapters in the text with your own insight.

5. The findings' crisis of the dissertation

Problem: I think my findings are too banal.

Here are five questions to overcome your doubts… LINK

6. The writing crisis of the dissertation

Problem: This writing is never ending...

- Formulate ALL chapters of the outline.

- Assign ALL content to the chapters.

- Plan specific time units and deadlines for each chapter.

- Build in rewards and follow-up projects.

- A great writing assistant: dictate and let Dragon Naturally Speaking write.

7. The dissertation's money crisis

Problem: I’m out of money.

- This is actually good because it will motivate you to finish.

- Plan your time like this: Part time everyday job and part-time for the doctoral thesis.

- Set a real deadline for the whole PhD project. Find a motivating follow-up project.

8. The time crisis of the dissertation

Problem: I have already done so much but there’s simply no more time.

- Make the presentation for the defense NOW.

- Learn the Aristolo writing technique for five pages of good text per day.

- Omit everything unimportant!

- Follow the Aristolo Master Plan for the dissertation, set daily rituals and task packages.

- Power working with power sleeping is the method of choice.

- High-Speed Writing is possible with Dragon Naturally Speaking.

- Formulate your set of theses NOW. These become your framework for the text writing.

9. The social crisis of the dissertation

Problem: Everyone's bugging me.

- There are libraries, cafés, hotel lobbies, etc. where nobody knows you…

- You surely can find the off button on your phone…

- Put signs on the door: "Do not disturb - research in progress"...

- Surely you have friends that will prevent others from disturbing you.

Admittedly: these are trivial tips, but they help in the same way that washing hands in hospital reduces the risk of infection by 95%.

10. The thesis crisis of self-confidence

Problem: I'm too stupid to write a dissertation.

- You started this project, so…

- YOU had already convinced a professional supervisor that you are NOT too stupid…

- You're the one who pushed through your first concepts with the supervisor, so…

- You're always down until the next sense of accomplishment, so…

- You're in good company. Every great explorer has said after a discovery: Am I stupid! Why didn't I think of that much sooner??

It’s better to get your doctorate fast. This is the best thing for EVERYONE, for YOU, your social environment, the university, science and future employers. We wish you success with your dissertation! Silvio and the Aristolo Team PS: Check out the PhD Guide for writing a PhD in 200 days .

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Aspect | Thesis | Thesis Statement |

Definition | An extensive document presenting the author's research and findings, typically for a degree or professional qualification. | A concise sentence or two in an essay or research paper that outlines the main idea or argument. |

Position | It’s the entire document on its own. | Typically found at the end of the introduction of an essay, research paper, or thesis. |

Components | Introduction, methodology, results, conclusions, and bibliography or references. | Doesn't include any specific components |

Purpose | Provides detailed research, presents findings, and contributes to a field of study. | To guide the reader about the main point or argument of the paper or essay. |

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

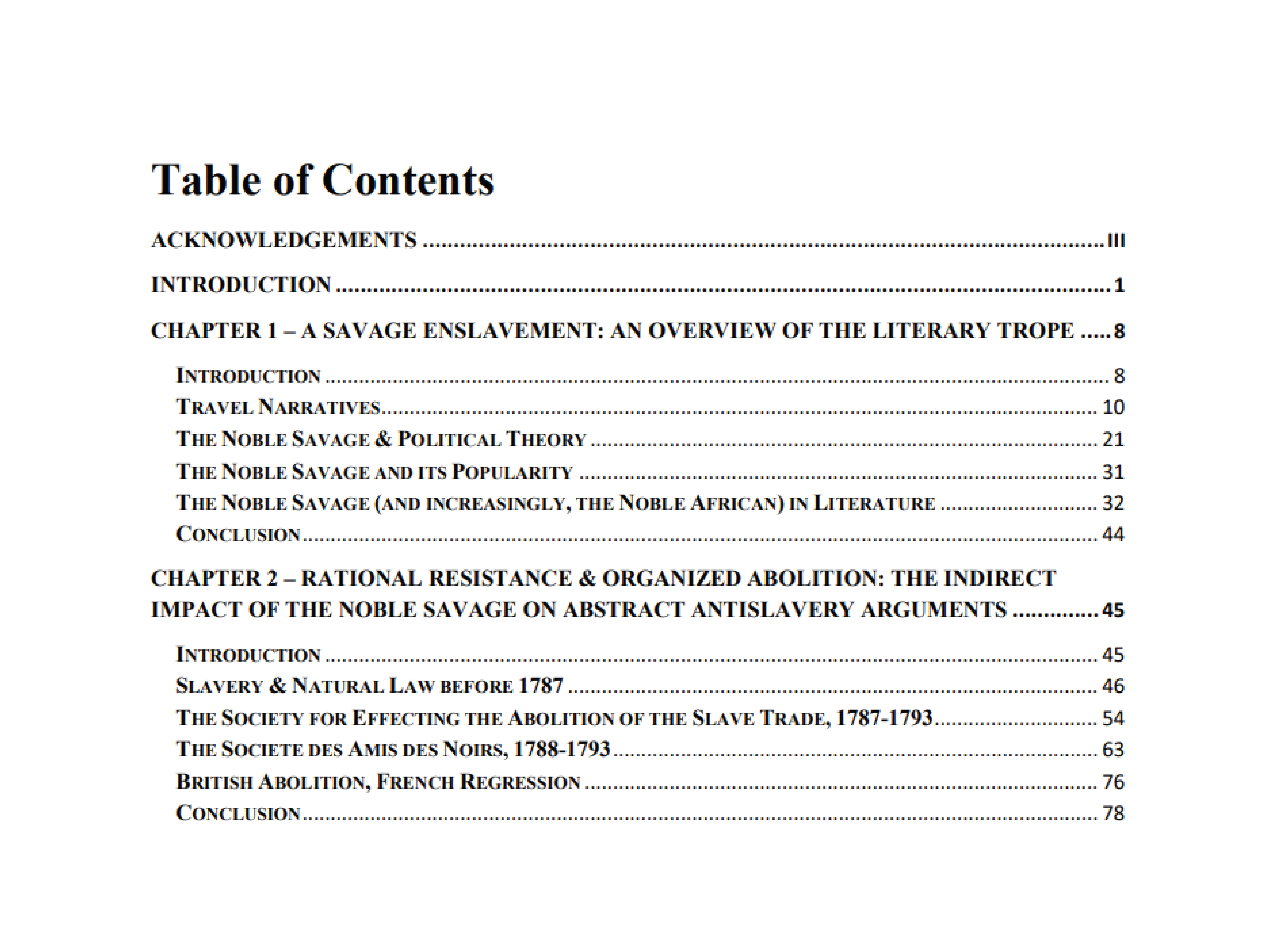

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.

- Literature review : Introduce any relevant existing research on your topic, situating your work within the broader academic conversation and highlighting where your research fits in.

- State the research Question(s) or objective(s) : Clearly articulate the primary questions or objectives your research aims to address.

- Outline the study's structure : Give a brief overview of how the subsequent sections of your work will unfold, guiding your readers through the journey ahead.

The introduction should captivate your readers, making them eager to delve deeper into your research journey.

Literature review section

Your study correlates with existing research. Therefore, in the literature review section, you'll engage in a dialogue with existing knowledge, highlighting relevant studies, theories, and findings.

It's here that you identify gaps in the current knowledge, positioning your research as a bridge to new insights.

To streamline this process, consider leveraging AI tools. For example, the SciSpace literature review tool enables you to efficiently explore and delve into research papers, simplifying your literature review journey.

Methodology

In the research methodology section, you’ll detail the tools, techniques, and processes you employed to gather and analyze data. This section will inform the readers about how you approached your research questions and ensures the reproducibility of your study.

Here's a breakdown of what it should encompass:

- Research Design : Describe the overall structure and approach of your research. Are you conducting a qualitative study with in-depth interviews? Or is it a quantitative study using statistical analysis? Perhaps it's a mixed-methods approach?

- Data Collection : Detail the methods you used to gather data. This could include surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, etc. Mention where you sourced your data, the duration of data collection, and any tools or instruments used.

- Sampling : If applicable, explain how you selected participants or data sources for your study. Discuss the size of your sample and the rationale behind choosing it.

- Data Analysis : Describe the techniques and tools you used to process and analyze the data. This could range from statistical tests in quantitative research to thematic analysis in qualitative research.

- Validity and Reliability : Address the steps you took to ensure the validity and reliability of your findings to ensure that your results are both accurate and consistent.

- Ethical Considerations : Highlight any ethical issues related to your research and the measures you took to address them, including — informed consent, confidentiality, and data storage and protection measures.

Moreover, different research questions necessitate different types of methodologies. For instance:

- Experimental methodology : Often used in sciences, this involves a controlled experiment to discern causality.

- Qualitative methodology : Employed when exploring patterns or phenomena without numerical data. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, or content analysis.

- Quantitative methodology : Concerned with measurable data and often involves statistical analysis. Surveys and structured observations are common tools here.

- Mixed methods : As the name implies, this combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The Methodology section isn’t just about detailing the methods but also justifying why they were chosen. The appropriateness of the methods in addressing your research question can significantly impact the credibility of your findings.

Results (or Findings)

This section presents the outcomes of your research. It's crucial to note that the nature of your results may vary; they could be quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both.

Quantitative results often present statistical data, showcasing measurable outcomes, and they benefit from tables, graphs, and figures to depict these data points.

Qualitative results , on the other hand, might delve into patterns, themes, or narratives derived from non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations.

Regardless of the nature of your results, clarity is essential. This section is purely about presenting the data without offering interpretations — that comes later in the discussion.

In the discussion section, the raw data transforms into valuable insights.

Start by revisiting your research question and contrast it with the findings. How do your results expand, constrict, or challenge current academic conversations?

Dive into the intricacies of the data, guiding the reader through its implications. Detail potential limitations transparently, signaling your awareness of the research's boundaries. This is where your academic voice should be resonant and confident.

Practical implications (Recommendation) section

Based on the insights derived from your research, this section provides actionable suggestions or proposed solutions.

Whether aimed at industry professionals or the general public, recommendations translate your academic findings into potential real-world actions. They help readers understand the practical implications of your work and how it can be applied to effect change or improvement in a given field.

When crafting recommendations, it's essential to ensure they're feasible and rooted in the evidence provided by your research. They shouldn't merely be aspirational but should offer a clear path forward, grounded in your findings.

The conclusion provides closure to your research narrative.

It's not merely a recap but a synthesis of your main findings and their broader implications. Reconnect with the research questions or hypotheses posited at the beginning, offering clear answers based on your findings.

Reflect on the broader contributions of your study, considering its impact on the academic community and potential real-world applications.

Lastly, the conclusion should leave your readers with a clear understanding of the value and impact of your study.

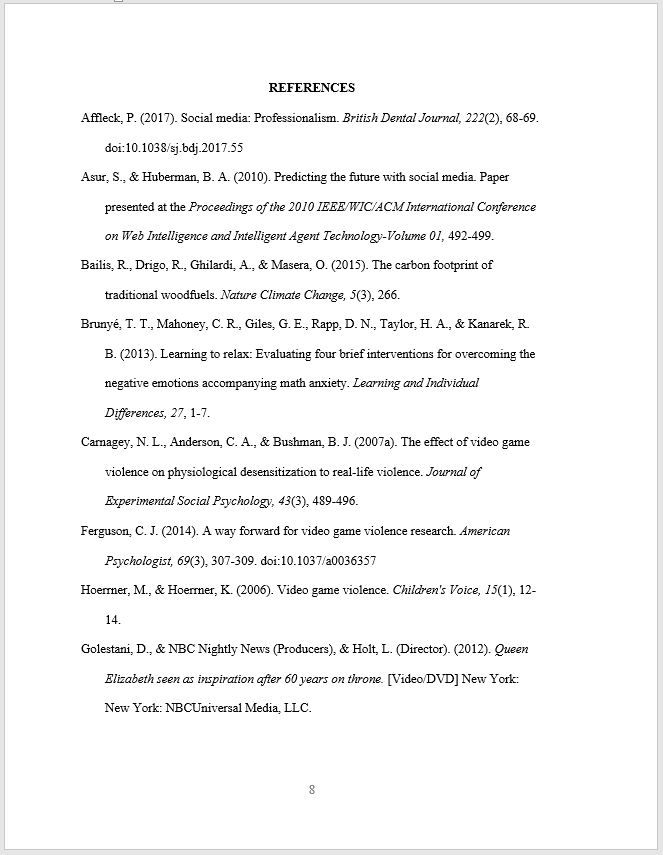

References (or Bibliography)

Every theory you've expounded upon, every data point you've cited, and every methodological precedent you've followed finds its acknowledgment here.

In references, it's crucial to ensure meticulous consistency in formatting, mirroring the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style .

Proper referencing helps to avoid plagiarism , gives credit to original ideas, and allows readers to explore topics of interest. Moreover, it situates your work within the continuum of academic knowledge.

To properly cite the sources used in the study, you can rely on online citation generator tools to generate accurate citations!

Here’s more on how you can cite your sources.

Often, the depth of research produces a wealth of material that, while crucial, can make the core content of the thesis cumbersome. The appendix is where you mention extra information that supports your research but isn't central to the main text.

Whether it's raw datasets, detailed procedural methodologies, extended case studies, or any other ancillary material, the appendices ensure that these elements are archived for reference without breaking the main narrative's flow.

For thorough researchers and readers keen on meticulous details, the appendices provide a treasure trove of insights.

Glossary (optional)

In academics, specialized terminologies, and jargon are inevitable. However, not every reader is versed in every term.

The glossary, while optional, is a critical tool for accessibility. It's a bridge ensuring that even readers from outside the discipline can access, understand, and appreciate your work.

By defining complex terms and providing context, you're inviting a wider audience to engage with your research, enhancing its reach and impact.

Remember, while these components provide a structured framework, the essence of your thesis lies in the originality of your ideas, the rigor of your research, and the clarity of your presentation.

As you craft each section, keep your readers in mind, ensuring that your passion and dedication shine through every page.

Thesis examples

To further elucidate the concept of a thesis, here are illustrative examples from various fields:

Example 1 (History): Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807 by Suchait Kahlon.

Example 2 (Climate Dynamics): Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennial-scale climate changes: a statistical modelling study by Takahito Mitsui · Michel Crucifix

Checklist for your thesis evaluation

Evaluating your thesis ensures that your research meets the standards of academia. Here's an elaborate checklist to guide you through this critical process.

Content and structure

- Is the thesis statement clear, concise, and debatable?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background and context?

- Is the literature review comprehensive, relevant, and well-organized?

- Does the methodology section clearly describe and justify the research methods?

- Are the results/findings presented clearly and logically?

- Does the discussion interpret the results in light of the research question and existing literature?

- Is the conclusion summarizing the research and suggesting future directions or implications?

Clarity and coherence

- Is the writing clear and free of jargon?

- Are ideas and sections logically connected and flowing?

- Is there a clear narrative or argument throughout the thesis?

Research quality

- Is the research question significant and relevant?

- Are the research methods appropriate for the question?

- Is the sample size (if applicable) adequate?

- Are the data analysis techniques appropriate and correctly applied?

- Are potential biases or limitations addressed?

Originality and significance

- Does the thesis contribute new knowledge or insights to the field?

- Is the research grounded in existing literature while offering fresh perspectives?

Formatting and presentation

- Is the thesis formatted according to institutional guidelines?

- Are figures, tables, and charts clear, labeled, and referenced in the text?

- Is the bibliography or reference list complete and consistently formatted?

- Are appendices relevant and appropriately referenced in the main text?

Grammar and language

- Is the thesis free of grammatical and spelling errors?

- Is the language professional, consistent, and appropriate for an academic audience?

- Are quotations and paraphrased material correctly cited?

Feedback and revision

- Have you sought feedback from peers, advisors, or experts in the field?

- Have you addressed the feedback and made the necessary revisions?

Overall assessment

- Does the thesis as a whole feel cohesive and comprehensive?

- Would the thesis be understandable and valuable to someone in your field?

Ensure to use this checklist to leave no ground for doubt or missed information in your thesis.

After writing your thesis, the next step is to discuss and defend your findings verbally in front of a knowledgeable panel. You’ve to be well prepared as your professors may grade your presentation abilities.

Preparing your thesis defense

A thesis defense, also known as "defending the thesis," is the culmination of a scholar's research journey. It's the final frontier, where you’ll present their findings and face scrutiny from a panel of experts.

Typically, the defense involves a public presentation where you’ll have to outline your study, followed by a question-and-answer session with a committee of experts. This committee assesses the validity, originality, and significance of the research.

The defense serves as a rite of passage for scholars. It's an opportunity to showcase expertise, address criticisms, and refine arguments. A successful defense not only validates the research but also establishes your authority as a researcher in your field.

Here’s how you can effectively prepare for your thesis defense .

Now, having touched upon the process of defending a thesis, it's worth noting that scholarly work can take various forms, depending on academic and regional practices.

One such form, often paralleled with the thesis, is the 'dissertation.' But what differentiates the two?

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they refer to distinct research projects undertaken at different levels of higher education.

To the uninitiated, understanding their meaning might be elusive. So, let's demystify these terms and delve into their core differences.

Here's a table differentiating between the two.

Aspect | Thesis | Dissertation |

Purpose | Often for a master's degree, showcasing a grasp of existing research | Primarily for a doctoral degree, contributing new knowledge to the field |

Length | 100 pages, focusing on a specific topic or question. | 400-500 pages, involving deep research and comprehensive findings |

Research Depth | Builds upon existing research | Involves original and groundbreaking research |

Advisor's Role | Guides the research process | Acts more as a consultant, allowing the student to take the lead |

Outcome | Demonstrates understanding of the subject | Proves capability to conduct independent and original research |

Wrapping up

From understanding the foundational concept of a thesis to navigating its various components, differentiating it from a dissertation, and recognizing the importance of proper citation — this guide covers it all.

As scholars and readers, understanding these nuances not only aids in academic pursuits but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the relentless quest for knowledge that drives academia.

It’s important to remember that every thesis is a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the indomitable spirit of discovery.

Good luck with your thesis writing!

Frequently Asked Questions

A thesis typically ranges between 40-80 pages, but its length can vary based on the research topic, institution guidelines, and level of study.

A PhD thesis usually spans 200-300 pages, though this can vary based on the discipline, complexity of the research, and institutional requirements.

To identify a thesis topic, consider current trends in your field, gaps in existing literature, personal interests, and discussions with advisors or mentors. Additionally, reviewing related journals and conference proceedings can provide insights into potential areas of exploration.

The conceptual framework is often situated in the literature review or theoretical framework section of a thesis. It helps set the stage by providing the context, defining key concepts, and explaining the relationships between variables.

A thesis statement should be concise, clear, and specific. It should state the main argument or point of your research. Start by pinpointing the central question or issue your research addresses, then condense that into a single statement, ensuring it reflects the essence of your paper.

You might also like

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

The Impact of Visual Abstracts on Boosting Citations

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.