- Best Online Colleges & Universities

- Best Nationally Accredited Online Colleges & Universities

- Regionally Accredited Online Colleges

- Online Colleges That Offer Free Laptops

- Self-Paced Online College Degrees

- Best Online Universities & Colleges

- Cheapest and Most Affordable Online Colleges

- The Most Affordable Online Master's Programs

- Best Online MBA Programs

- Most Affordable Online MBA Programs

- Online MBA Programs with No GMAT Requirement

- Cheapest Law Schools Online

- Quickest Online Master's Degrees

- Easiest PhD and Shortest Doctoral Programs Online

- Fastest Accelerated Online Degree Programs

- Best Accredited Online Law Schools

- 4-Week Online Course for Medical Coding and Billing

- Accredited Medical Billing and Coding Schools Online with Financial Aid

- Become a Medical Assistant in 6 Weeks

- Most Useless College Degrees

- 6 Month Certificate Programs That Pay Well

- Accredited Online Colleges

- Search Programs

15 Least & Most Expensive Colleges in the U.S.

Online colleges that offer laptops in georgia, online colleges that offer laptops in illinois, new york online colleges that offer laptops, the quickest online master's degrees 2024, 6 month certificate programs that pay well 2024, easiest phd and shortest doctoral programs online 2024, 4-week online course for medical coding and billing 2024.

Explore a range of online doctoral programs, including Ph.D. degrees, that offer accelerated paths, reduced residency requirements, and flexible online learning options.

Find Your School in 5 Minutes or Less

Many schools have rolling admissions, which means you can start a program in a few weeks!

Many degree programs fall under the title of doctorate, including Doctor of Philosophy degrees or Ph.D.

These Ph.D. degree programs are available in a variety of subjects and are intended to help students understand their specialty in the abstract and as a school of thought and theory rather than strictly as a practice.

Institutions that offer the best programs typically have exceptional funding, prestigious reputations, top-of-the-line research facilities, and abundant academic resources.

When selecting one of the shortest online doctoral programs or easiest online Ph.D. programs, you can access more info by visiting the links provided in each school description to ensure that you find the best program for you!

The easiest isn't always the shortest nor the shortest the easiest.

1-year Online Doctoral Programs | 18 Month Doctorate Programs Without Dissertation | Shortest Doctoral Programs Online and On-campus | Easiest Ph.D. to Get Online | Easiest PhD to Get (Traditional) | Free PhD Programs Online

Doctorate Degree vs PhD

Ph.D. programs focus more on the theoretical and abstract aspects of their respective fields of study to understand it as a school of thought rather than just a practical application.

Usual doctorate programs tend to be more practical in their study and focus on the application of knowledge rather than understanding more abstract perspectives.

Ph.D. degrees are often offered in the same fields that have standard doctoral degrees available usually offered in fields such as engineering, mathematics, natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities.

Doctorate programs are made up of advanced coursework, research projects, or thesis work almost strictly for practical application. Such degrees will get you ready to teach at the university level or help you advance to the leading edge of your field researching, serving, and creating.

Ph.D. and Doctorate degrees can often achieve the same ends and should be considered more or less equal in weight.

1 Year Ph.D. Programs Online

Chatham university.

Chatham offers a 1-year online DNP program for working nurses seeking advanced leadership roles. The intensive curriculum covers care delivery models, quality improvement, evidence-based practice, and informational systems. The program features synchronous online classes and immersive clinicals at sites nationwide. Students collaborate virtually with renowned faculty.

Within 12 months, students complete 36 credits and 1,000 clinical hours. Graduates can sit for Family Nurse Practitioner certification. Nurses with a BSN can enter the accelerated program. Applicants need an active RN license. This online DNP empowers nurses to rapidly earn doctoral credentials while working. It prepares graduates to advance as clinical, executive, research, and teaching leaders.

Breyer State Theology University

Breyer State Theology University offers a 1-year online PhD in Grief Counseling through its Department of Ethereal Studies. This accelerated program is tailored for working professionals seeking to advance their bereavement therapy career. The curriculum covers advanced grief counseling theories and interventions for diverse populations. Students gain expertise in areas like trauma-informed care, healing rituals, afterlife philosophies, and continuing bonds.

The online format combines asynchronous learning with live classes in an intimate cohort overseen by esteemed faculty. Students complete their dissertation in just one year. Graduates earn a PhD from BSU's pioneering metaphysical psychology department. This flexible doctoral program prepares students to progress their counseling practice or pursue academic research roles.

American International Theism University

American International Theism University (AITU) offers one-year online doctoral degrees for working professionals. Accelerated PhD tracks include Philosophy of Islamic Studies, Business Administration, Education, Finance, and Grief Counseling. Professional doctorates prepare leaders in Divinity, Sacred Music, Spiritual Psychotherapy, and more. The online programs blend video lectures, discussions, and immersive retreats. Curricula explore metaphysics, ethics, and wisdom traditions across faiths.

Within 12 months, students complete doctoral coursework, exams, and a dissertation overseen by distinguished faculty. Applicants should hold a relevant master's degree and background in theological studies or social sciences. These intensive online doctoral programs allow students to rapidly earn advanced credentials through flexible study with global peers. Graduates pursue roles driving innovation in spiritual care, research, and leadership.

Online Doctorate Programs That Might Interest You

15-18 month doctorate programs without dissertation, boston university.

Boston University offers a Post-Professional Doctor of Occupational Therapy degree program that can be completed in 18 months. The program consists of 10 courses, which are about 33 to 37 credits. Students may concentrate on various areas and can then choose what else they would prefer to learn to complete their credit requirements.

This is a fully online degree program that accelerates each semester’s worth of class to take only seven weeks to complete with new courses starting every September, January, and May. The program is available to doctoral students who have completed an accredited occupational therapy program. There are foundation courses, which include evidence-based practice and health care management, but no dissertation is necessary whereas a doctoral project is still required.

Frontier Nursing University

The Maryville University of St. Louis offers a Doctor of Nursing (DNP) program that is available online. The DNP program requires students to complete a total of 33 credit hours, including 18 to 20 months for completion. Many students in the online DNP program are working as nurses in the field, and this affords them a flexible program that allows many students to achieve their academic goals while active in the healthcare industry.

This course is an online program that does not require a GMAT or GRE. It may have a waiting list, but unlike other programs, it does not require clinical hours. The Doctorate in Higher Education Leadership is an online program that offers personal coaching throughout the process. It is a cohort learning method with online education, and students might need a bit more time to complete it.

Maryville University

Maryville University offers online doctoral degrees tailored for working professionals. Programs available fully online include Doctorates in Higher Education Leadership, Educational Leadership, Nursing Practice, Health Administration, Physical Therapy, and Occupational Therapy. The EdD programs prepare graduates for leadership and faculty roles in education. The DNP equips nurses for advanced clinical and executive practice.

Health Administration focuses on healthcare organizational development, quality, and finance. Licensed PTs and OTs can pursue clinical doctorates while working. Courses blend live online classes and self-paced learning. Programs leverage cutting-edge virtual labs and simulations. With a relevant master's degree, students can earn an accredited doctorate from Maryville University online to advance their careers.

24 Month Doctorate Programs

University of north carolina – chapel hill.

One option is to earn an online Ph.D. in Nursing, while another option is to earn their Medical Degree at the same time as their Master of Business Administration , but the Transitional Doctoral Program in Physical therapy may be earned in 24 months fully online. This part-time program provides online learning courses to help licensed physical therapists enhance their skills and gain access to higher career options. Some credits can be earned through workplace applications.

Grand Canyon University

Grand Canyon University offers over a dozen online doctoral degrees tailored for working professionals. GCU provides online EdD tracks in Organizational Leadership, Higher Education Leadership, and K-12 Leadership. Other doctorates cover psychology, nursing, business, and more. Programs blend asynchronous and live virtual classes focused on applying concepts. Specialized tracks allow customization.

Online students get personalized faculty support and access to robust digital resources. Within 2 years (or less), learners complete coursework, residencies, exams, and a dissertation to earn an accredited doctoral degree from GCU. With flexible and practical curricula, GCU enables busy professionals to obtain doctorates fully online and further their careers.

Liberty University

Liberty University offers a Doctor of Education degree program that can be completed fully online. The minimum time to earn the degree is about 30 months for completion of all 54 credits. The courses are each 8 weeks long and no dissertation is required. The Doctor of Education degree program provides a curriculum that focuses on developing innovative programs, as well as a capstone project.

University of West Georgia

The University of West Georgia offers several online doctoral degree options for working professionals seeking advanced training. UWG provides online doctorates in School Improvement, Nursing Education, Professional Counseling and Supervision, and Higher Education Administration. The EdD programs focus on data-driven leadership strategies and developing administrative expertise.

The DNP prepares nurses to improve care systems and patient outcomes. Coursework blends synchronous evening classes and self-paced learning for flexibility. Experiential projects allow application to careers. With a relevant master's degree, students can earn an accredited doctorate fully online from UWG to advance as leaders in their field.

Shortest Ph.D. Programs Online and On-campus

Obtaining a Ph.D. can be a long-term commitment and many doctoral programs can take over five years to complete. To help busy working professionals looking to jumpstart their careers and those looking to begin their careers at a high level, this list serves as a simple reference guide, compiling information on some of the shortest doctoral programs in the country.

These online degree programs operate in full-time, part-time, fully online, or hybrid formats.

- Baylor University - online EdD in Learning and Organizational Change, 54 credits, 36 months

- Maryville University - online Doctor of Nursing Practice (Online DNP), 20 months, no GRE or no GMAT requirement

- University of Dayton - online Doctor of Education (Ed.D.) in Leadership for Organizations, 36 months, 60 credits

- Capella University - online Doctor of Philosophy in Counselor Education and Supervision, 0 max transfer credits, 60 credits, CACREP accredited

- Franklin University - online Doctor of Business Administration (DBA), 58 credit hours, transfer up to 24 hours of previously earned credit, 36 months + 1 year for dissertation

- Walden University - online Ph.D. in Forensic Psychology, up to 53 credits, fast-track option, earn MPhil at the same time

- Frontier Nursing University - online Doctor of Nursing Practice, MSN with DNP, 675 clinical hours for MSN plus 360 additional for DNP

- Boston University - Online Post-Professional Doctor of Occupational Therapy, PP-OTD, 33-37 credits

- University of Florida - online MSN to DNP, 35 credits, five semesters

- Gwynedd Mercy University - Accelerated Executive Doctorate of Education ABD (All But Dissertation) Completion Program, online EdD , 27 credit hours, 18 months

- Duquesne University - Online Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP), 35 credit hours

- The College of St. Scholastica - Transitional Doctor of Physical Therapy, online tDPT, 16 credits

- Liberty Univesity - Doctor of Ministry, online DMin, 30 credit hours, 24 months

- University of Florida - Doctor of Nursing Practice, MSN to DNP, 35 credits, 5 semesters

- University of North Dakota - Post-Master's Doctor of Nursing Practice, online DNP, 36 credit hours, 5 semesters

- Seton Hall University - Doctor of Nursing Practice, online DNP, 31+ credits for post-MSN students, 73-79 credits for post-BSN students

- Regis University - Doctor of Nursing Practice, online DNP , 28-33 credit hours, 8-week terms

- Georgia State University - Curriculum and Instruction EdD, Educational Leadership EdD, on-campus EdD, 54 credit hours

- Bowling Green State University - Technology Management, web-based Ph.D., 66 credit hours

- Hampton University - Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Management, online Ph.D., 60 credit hours

- Indiana University of Pennsylvania - Safety Sciences, online Ph.D., 54 credit hours

- East Carolina University - Doctor of Nursing Practice, hybrid online DNP

Easiest Ph.D. Programs Online & On-Campus

To be sure, at the Ph.D. level, no program could be considered "easy," but there are certain programs designed to be "easier" than others. Generally, education, humanities, and the social sciences are considered the easiest fields in which to pursue degrees.

With that in mind, our list of the easiest Ph.D. programs includes schools and programs that offer significantly reduced residency requirements, accelerated courses, credit transfers, and integrated dissertation colloquia.

The rankings below display schools with accreditation from at least one of the six regional accrediting agencies , and all offer at least one virtual Ph.D. degree. Accredited online Ph.D. programs are also organized according to the U.S. News and World Report and Forbes Magazine rankings.

Easiest Online Ph.D. Programs & Online Doctoral Programs

- WALDEN UNIVERSITY - 156 Online Doctoral Programs

- REGENT UNIVERSITY - 81 online doctorate degrees, 6 Ph.D. programs online

- HAMPTON UNIVERSITY - 5 online doctoral degree programs

- UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA - 8 online doctoral degree programs

- UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI - 4 online doctorate programs

- COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY - 3 online Ph.D. programs, 1 online doctoral program

- UNIVERSITY OF NORTH DAKOTA - 12 online Ph.D. programs, 3 online doctoral programs

- NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY - 10 online doctorate programs, 8 online Ph.D. programs

- LIBERTY UNIVERSITY - 19 online Ph.D. programs, 16 online doctorate programs

Easiest Ph.D. to Get (Traditional)

The easiest doctorate degree can vary depending on your interests, skills, and strengths. However, here is a list of doctorate degrees that are mentioned as potentially less difficult to obtain:

- Business Administration: This program focuses on business development, design, methods, tools, and professional ethics. A Ph.D. in Business Administration can be a good choice for professionals looking to advance their careers in business.

- Counseling: A doctorate in counseling allows you to specialize in areas such as human behavior, social psychology, counseling supervision, or specific therapy approaches. This degree can lead to advanced career opportunities in healthcare and social services.

- Criminal Justice: This program equips you with research skills and the ability to analyze data in the field of criminal justice. It can open doors to various career paths, including emergency management, forensic departments, and information security sectors.

- Education: A doctorate in education focuses on enhancing educational research skills and preparing for leadership roles in educational institutions. It can lead to administrative positions in universities, professional departments, or elementary and secondary schools.

- Healthcare Administration: This program prepares you for leadership roles in the business aspect of the medical industry. It covers topics such as policies, ethics, group management, hospital administration, and advanced patient care.

- Human Services: A doctorate in human services prepares you for leadership positions within organizations that help underserved populations. It focuses on policies, legislation, rights, ethics, and protocols for serving within human services organizations.

- Management: This program provides practical skills applicable to various industry settings. It covers areas such as financial management, system management, conflict management, and human resources management.

- Public Administration: A doctorate in public administration develops managerial and strategic planning skills for administrative roles in different industries. It offers coursework in ethics of management, public policy, strategic planning, performance management, employee evaluation, and economics of administration.

- Public Health: This program equips you with advanced training and research skills for the healthcare industry. It focuses on leadership and management roles in public health, emphasizing innovative thinking and communication mastery.

- Public Policy: A doctorate in public policy focuses on theory, ethics, research, and practice in public service programs. It prepares you to analyze and propose policies to improve communities and societies.

- Psychology: A doctorate in psychology combines research skills with professional practice. It can lead to careers as addictions counselors, applied researchers, professional consultants, or clinical psychologists.

- Theology: A doctorate in theology explores divine and spiritual traditions through academics, research, and religious studies. It can lead to careers as professors, social service managers, private school teachers, or directors of religious education.

Please note that the difficulty of a doctorate degree can vary depending on individual circumstances, personal strengths, and the specific requirements of each program. It's important to thoroughly research and consider your own interests, skills, and career goals before deciding on a doctorate program.

Free Ph.D. Programs Online (Fully Funded)

According to Best-Universities.net .

- Brown University - Fully-funded Ph.D. program in computer science

- University of Houston-Downtown - Full scholarship program for online doctorate

- Devry University - Comprehensive scholarship program for online degrees

- University of Maryland-Baltimore County - Full scholarship program for online undergraduate and graduate degrees

- Wilson Community College - Full scholarship program for community college students

- University of Leeds - Up to 30 fully-funded online Ph.D. programs

- University of the Witwatersrand - Comprehensive scholarship program for online bachelor's or master's degrees

- The University of Texas at Dallas - Full scholarship program for online bachelor's, master's, or doctoral degrees

- University of Strathclyde - Full scholarship program for online undergraduate or master's degrees

- Emory University - Fully-funded online Ph.D. program in economics

- New York University - Fully-funded Ph.D. program in childhood education

- University of Pennsylvania - Fully-funded online Ph.D. program in educational leadership and policy

If you're not looking for an accelerated program , the list below displays some of the best traditional Ph.D. programs in the country, according to Study.com.

Best Ph.D. Programs in the U.S.

| College/University Name | Distinction | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Conducts interdisciplinary research through at least 100 centers, institutes, and on-campus laboratories | Ithaca, NY | |

| Interdisciplinary clusters give students the option to collaborate with peers and faculty outside of their respective programs | Evanston, IL | |

| Hosts a faculty comprised of 19 Nobel Laureates and 4 Pulitzer Prize Winners | Stanford, CA | |

| Allows a doctoral student to participate in customized interdisciplinary degree programs | Berkeley, CA | |

| Offers over 160 Ph.D. programs | Ann Arbor, MI | |

| Home to 142 research centers and institutes | Philadelphia, PA | |

| Maintains 19 libraries stocked with over 10 million total volumes | Austin, TX | |

| Provides $11 million in graduate fellowships and other awards yearly, according to 2013 data | Seattle, WA | |

| Offers over 120 doctoral programs | Madison, WI |

Guide to Online Doctorate Degrees

Fewer positions requiring this advanced level qualification and reduced competition for such job opportunities among job seekers are some of the reasons behind the few doctoral graduates.

With technological advancements in almost all areas of life, acquiring education, a significantly advanced level of education has become more accessible.

Graduate students now do not have to attend physical classes to pursue their dreams of developing and advancing their skills.

You can pursue your doctorate in the comfort of your home or even your office. There was a 20% growth in students granted doctorate degrees between the 2009/2010 and 2019/2020 academic years, according to NCES. This growth has been attributed in part to online Ph.D. programs and the streamlining of modern universities.

Online Ph.D. programs are a relatively newer idea and online schooling in general has greatly increased access, flexibility, and convenience.

Students typically complete these degrees soon after completing a Master’s degree in the same area. As such, and with bachelor's degrees being necessary stepping stones, students can expect their journey from primary school to a Ph.D. to take about nine years, barring any accelerated tracks and failed classes.

Cost of an Online Doctoral Degree Program

When choosing any doctoral degree program, it is crucial to evaluate the costs and salary after attending. Even though online Ph.D. courses may usually be cheaper than on-campus learning, secondary schooling is rarely cheap and not every field will allow you to make back the cost in a reasonable amount of time.

Tuition, materials, technology, transportation, housing, and groceries should all be factors brought into account when deciding whether or where to attend, and in what field you can find the most success and fulfillment.

Below are the annual tuition rates of different institutions as reported by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

- Private-For profit institutions- $18,200

- Private-Not for-profit institutions- $37,600

- Public institutions- $9,400

Choosing an Online Doctoral Degree Program

Since doctoral programs require considerable investments of money and time, it is important to consider every factor before deciding on a school or program. Take some time to consider the marketability, cost, and difficulty of each program and your own interest in the subject. To reach your career and educational goals, do your best research.

How Long Does it Take to Get a PhD

The length of a Ph.D. program can vary, but it typically takes 3 to 6 years to complete.

- A Ph.D. program typically takes 5 to 6 years in the United States.

- A Ph.D. program typically takes 3 to 4 years in the UK and many other European countries.

The actual length of a Ph.D. program can be influenced by many factors, including the nature of the research, the student's progress, the advisor's availability, and funding considerations.

- Some students may finish in less time, while others may take longer.

- Part-time Ph.D. programs are also available, which can take longer to complete.

Here is a table summarizing the length of Ph.D. programs in different countries:

| Country | Typical Length of a Ph.D. Program |

|---|---|

| United States | 5 to 6 years |

| UK | 3 to 4 years |

| European countries | 3 to 4 years |

| Part-time | 6 to 8 years |

Top 50 doctorate-granting institutions ranked by the total number of doctorate recipients, by sex: 2020

| Walden U. | 1 | 867 | 276 | 591 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U. Michigan, Ann Arbor | 2 | 846 | 500 | 346 |

| U. Illinois, Urbana-Champaign | 3 | 821 | 505 | 316 |

| U. California, Berkeley | 4 | 797 | 475 | 322 |

| Purdue U., West Lafayette | 5 | 794 | 529 | 265 |

| Texas A&M U., College Station and Health Science Center | 6 | 772 | 466 | 306 |

| Stanford U. | 7 | 769 | 494 | 275 |

| U. Texas, Austin | 8 | 744 | 438 | 306 |

| U. Wisconsin-Madison | 9 | 724 | 374 | 350 |

| Ohio State U., Columbus | 10 | 704 | 400 | 304 |

| Pennsylvania State U., University Park and Hershey Medical Center | 11 | 688 | 389 | 299 |

| U. Washington, Seattle | 12 | 681 | 335 | 346 |

| Columbia U. in the City of New York | 13 | 673 | 362 | 311 |

| U. Florida | 14 | 650 | 345 | 305 |

| U. Minnesota, Twin Cities | 15 | 647 | 340 | 307 |

| U. California, Los Angeles | 16 | 632 | 381 | 251 |

| Harvard U. | 17 | 630 | 331 | 299 |

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology | 18 | 579 | 414 | 165 |

| U. Maryland, College Park | 19 | 568 | 328 | 240 |

| U. North Carolina, Chapel Hill | 20 | 556 | 254 | 302 |

| Arizona State U. | 21 | 536 | 304 | 232 |

| North Carolina State U. | 22 | 533 | 305 | 228 |

| Michigan State U. | 23 | 524 | 282 | 242 |

| Cornell U. | 24 | 514 | 277 | 237 |

| Georgia Institute of Technology | 25 | 512 | 377 | 135 |

| U. California, San Diego | 25 | 512 | 330 | 182 |

| Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State U. | 27 | 495 | 295 | 200 |

| U. California, Davis | 28 | 493 | 254 | 239 |

| U. Arizona | 29 | 473 | 252 | 221 |

| U. Pennsylvania | 30 | 469 | 255 | 214 |

| U. Georgia | 31 | 449 | 209 | 240 |

| U. Southern California | 32 | 437 | 244 | 193 |

| Northwestern U. | 33 | 433 | 237 | 196 |

| Johns Hopkins U. | 34 | 426 | 240 | 186 |

| Yale U. | 35 | 423 | 209 | 214 |

| U. California, Irvine | 36 | 420 | 241 | 179 |

| U. Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh | 36 | 420 | 211 | 209 |

| New York U. | 38 | 411 | 220 | 191 |

| Duke U. | 39 | 407 | 241 | 166 |

| Iowa State U. | 39 | 407 | 259 | 148 |

| Indiana U., Bloomington | 41 | 395 | 205 | 190 |

| Rutgers, State U. New Jersey, New Brunswick | 41 | 395 | 209 | 186 |

| CUNY, Graduate Center | 43 | 394 | 187 | 207 |

| U. Tennessee, Knoxville | 44 | 393 | 222 | 171 |

| U. Colorado Boulder | 45 | 392 | 249 | 143 |

| Florida State U. | 46 | 381 | 192 | 189 |

| U. Chicago | 47 | 370 | 245 | 125 |

| SUNY, U. Buffalo | 48 | 358 | 193 | 165 |

| Texas Tech U. | 49 | 356 | 172 | 182 |

| Boston U. | 50 | 337 | 176 | 161 |

Tied institutions are listed alphabetically.

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Earned Doctorates.

Doctorate recipients from U.S. colleges and universities: 1958–2020

(Number and percent) * = value < |0.05%|.

State or location of doctorate institution ranked by the total number of doctorate recipients, by sex: 2020

| California | 1 | 5,988 | 3,396 | 2,591 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texas | 2 | 4,201 | 2,324 | 1,875 |

| New York | 3 | 4,168 | 2,174 | 1,994 |

| Massachusetts | 4 | 2,815 | 1,571 | 1,244 |

| Pennsylvania | 5 | 2,602 | 1,433 | 1,169 |

| Illinois | 6 | 2,435 | 1,382 | 1,052 |

| Florida | 7 | 2,386 | 1,246 | 1,140 |

| Michigan | 8 | 1,967 | 1,093 | 874 |

| Ohio | 9 | 1,953 | 1,054 | 899 |

| North Carolina | 10 | 1,873 | 987 | 886 |

| Indiana | 11 | 1,613 | 970 | 643 |

| Minnesota | 12 | 1,545 | 626 | 919 |

| Virginia | 13 | 1,532 | 797 | 735 |

| Georgia | 14 | 1,484 | 821 | 663 |

| Maryland | 15 | 1,269 | 684 | 585 |

| Colorado | 16 | 1,079 | 630 | 449 |

| Arizona | 17 | 1,052 | 576 | 476 |

| Tennessee | 18 | 1,023 | 533 | 490 |

| Washington | 19 | 1,015 | 514 | 501 |

| New Jersey | 20 | 991 | 535 | 456 |

| Wisconsin | 21 | 976 | 509 | 467 |

| Missouri | 22 | 960 | 552 | 408 |

| Connecticut | 23 | 764 | 362 | 402 |

| Iowa | 24 | 727 | 417 | 310 |

| Alabama | 25 | 692 | 368 | 324 |

| Louisiana | 26 | 638 | 364 | 274 |

| South Carolina | 27 | 603 | 304 | 299 |

| District of Columbia | 28 | 579 | 285 | 294 |

| Oregon | 29 | 551 | 290 | 261 |

| Kansas | 30 | 548 | 306 | 242 |

| Utah | 31 | 543 | 326 | 217 |

| Kentucky | 32 | 504 | 270 | 234 |

| Oklahoma | 33 | 492 | 272 | 220 |

| Mississippi | 34 | 445 | 225 | 220 |

| Nebraska | 35 | 361 | 183 | 178 |

| Rhode Island | 36 | 311 | 150 | 161 |

| New Mexico | 37 | 300 | 135 | 165 |

| Arkansas | 38 | 270 | 159 | 111 |

| Nevada | 39 | 251 | 133 | 118 |

| Delaware | 40 | 218 | 117 | 101 |

| West Virginia | 41 | 214 | 119 | 95 |

| New Hampshire | 42 | 198 | 101 | 97 |

| Hawaii | 43 | 195 | 83 | 112 |

| North Dakota | 44 | 189 | 103 | 86 |

| Puerto Rico | 45 | 129 | 49 | 80 |

| South Dakota | 46 | 126 | 79 | 47 |

| Montana | 47 | 120 | 60 | 60 |

| Idaho | 48 | 114 | 71 | 43 |

| Wyoming | 49 | 94 | 62 | 32 |

| Maine | 50 | 69 | 31 | 37 |

| Vermont | 51 | 57 | 30 | 27 |

| Alaska | 52 | 54 | 25 | 29 |

Online PhD Programs for You

Take the next step toward your future with online learning., you might also like.

Accelerated Bachelor's Degree Online

What Are The 12 Ivy League Schools

Most Popular Online Colleges

Contact information

Quick links, subscribe to our newsletter.

- Majors & Careers

- Online Grad School

- Preparing For Grad School

- Student Life

Top 10 Best 1-Year PhD Programs Online

Are you searching for the best 1-year PhD programs online? A growing number of students are choosing master’s and doctorate degrees with flexible, online models. In a highly competitive job market, having an advanced qualification gives you better salary potential and job prospects. However, not everyone can afford the time and costs of a traditional-length PhD program and living on-campus. If you’re a working professional and want to continue your studies, an online PhD is an excellent option.

Remember, don’t be fooled by the online mode. While the fastest PhD programs offer immense flexibility, they’re by no means easy. It can still be a major time commitment, and that’s where 1-year PhD programs online come into play. Additionally, not everyone will complete 1-year PhD programs in one year; rather, the curriculum makes it possible. Other obligations might force students to take two years to complete their programs.

Ready to find the shortest doctoral program online? Let’s get started!

Table of Contents

Best 1-Year PhD Programs Online

Chatham university.

Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP)

Chatham University is known for its social mobility and support for disadvantaged students. The school’s Doctor of Nursing Practice takes 12 months to complete if you stay on track, and you’ll need to have a master’s degree in nursing to be considered. The program aims to develop future nursing leaders who will improve healthcare delivery and could very well be the fastest doctorate degree program out there!

- Courses : Structure and application of contemporary nursing knowledge, quality improvement in health care, and communication & collaboration for healthcare leadership

- Duration : 12 months

- Credits : 27

- Tuition : $1,126 per credit

- Financial aid : Scholarships, graduate assistantships, veteran benefits, and alumni discounts

- Graduation rate : 62.5%

- Location : Pittsburgh, PA

Breyer State Theology University, Department of Ethereal Doctor of Psychology in Grief Counseling

Ethereal Accelerated Doctor of Psychology in Grief Counseling

Breyer State Theology University aims to provide students with high-level knowledge to follow religious careers as ministers, theologians, and counselors. Its Ethereal Doctor of Psychology program in Grief Counseling is also one of the shortest doctoral programs available, with a 1-year duration. It is one of the only online accelerated PhD that helps counselors become specialized in grief and bereavement.

- Courses : An overview of psychotherapy & counseling, ethics in grief counseling, and therapy with the terminally ill

- Tuition : $4,500

- Location : Brandenton, FL

Related: Top 10 Best PhD in Theology Programs

American International Theism University

Accelerated Ethereal Doctorate in Business Administration

The American International Theism University provides accelerated doctoral programs in various disciplines, including theology, business, social work , music, and the arts. This specific accelerated doctoral program prepares students for roles in education, research, government departments, or private business administration. The school offers many disciplines for its online accelerated PhD programs, and you can complete them within one year.

- Courses : International business, managerial economics, and strategic management

- Tuition : $7,950

- Location : Englewood, Florida

Frontier Nursing University

Frontier Nursing University was ranked third in the nation for the best online master’s program in FNP by the US News & World Report. This program is suitable for certified nursing practitioners and midwives with an MSN in nursing. The minimum duration for completion is 15 months.

- Duration : 15-18 months

- Credits : 30

- Tuition : $19,950

- Financial aid : Scholarships, loans, etc.

- Location : Versailles, KY

Boston University, Boston University College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College

Online Post-Professional Doctor of Occupational Therapy (PP-OTD)

Boston University is the largest non-profit university in the US, offering a range of programs across various levels and disciplines. Its PP-OTD program is open to graduates in occupational therapy and has three intakes per year (May, September, and January). As part of this online accelerated PhD program, each semester requires you to work on your doctoral project parallel to other coursework.

- Courses : Contemporary trends in occupational therapy, health promotion and wellness, and social policy and disability practicum

- Duration : 18 months

- Credits : 33-36

- Tuition : $1,994 per credit

- Financial aid : Merit-based scholarships, loans, etc.

- Graduation rate: 87.2%

- Location : Boston, MA

Maryville University

Online Doctor of Nursing Practice

Maryville University is a private university that has offered post-secondary education since 1872. Its DNP enables practitioner nurses to pursue roles at the highest level of the nursing sector. The program is fully online, with no campus attendance required.

- Courses : Principles of epidemiology and biostatistics, advanced health care policy, and quality and patient safety in advanced nursing practice

- Duration : 20 months

- Credits : 33

- Courses : 11

- Tuition : $922 per credit

- Financial aid: Scholarships, student employment, loans, and grants

- Graduation rate: 44.6%

- Location : St. Louis, MO

The University of North Carolina, School of Medicine

Transitional Doctor of Physical Therapy (tDPT)

The University of North Carolina is a public research university, the flagship university of the North Carolina system. A public Ivy university, its transitional DPT program equips working professionals with specialized knowledge in three key areas: clinical foundation, clinical practice, and specialty practice.

- Duration : 24 months

- Tuition : Refer tuition page

- Financial aid : Scholarships and loans

- Graduation rate : 90.8%

- Location : Chapel Hill, NC

Grand Canyon University, College of Nursing and Healthcare Professions

Grand Canyon University is a private Christian university. Its DNP program is well-suited to professional working nurses and offers advanced education in nursing leadership, medical informatics, and public health . You can transfer up to three doctoral credits from previous studies.

- Courses : Emerging areas of human health, patient outcomes and sustainable change, and data analysis.

- Credits : 39

- Tuition : $725 per credit

- Financial aid : Scholarships, grants, and loans.

- Graduation rate : 37.6%

- Location : Phoenix, AZ

Liberty University

Doctor of Ministry (DMin)

Liberty University is a Christian university that offers various online programs at undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral levels in various disciplines. Its DMin program has a practical focus, equipping students to handle ministry-setting challenges. The program is made up of 8-week courses, and you can transfer up to 50% of degree credits.

- Tuition : $565 per credit hour

- Graduation rate: 28.5%

- Location : Lynchburg, VA

University of West Georgia

Doctor of Education in Professional Counseling and Supervision

The University of West Georgia is a public university with 12,700 students with a student-faculty ratio of 19:1. This doctoral program in counseling covers counseling methods through clinical and administrative supervision, advocacy and leadership, and program evaluation.

- Courses : Ethical leadership in education and advanced therapeutic techniques in counseling.

- Tuition : $241 per credit

- Financial aid : Scholarships, grants, federal work-study, and loans.

- Graduation rate : 39.1%

- Location : Carrollton, GA

What Are 1-Year PhD Programs Online?

A one-year PhD program is a doctorate you can complete in a very short time and generally requires 30 credits. Though short online PhD programs are called “1-year online doctoral programs”, very few universities offer PhD programs that can be completed in a year.

Most programs take around 15 months or so to complete, though some can last up to two years. Generally, any PhD you can complete in two years or less is considered in this category.

Related Reading: Top 15 Cheapest Online PhD Programs

Do All The Shortest PhD Programs Require a Dissertation?

No. Many short Ph.D. programs don’t require a dissertation. However, some of these programs involve a research project parallel to other coursework. This means the project must be completed within the program duration, unlike longer doctorates, where the research component is dedicated years after your coursework.

Why Choose a One-year PhD Program Online?

Many opt to study 1-year PhD programs online because they want to earn their doctorate in a short period and enter the competitive job market earlier. This can save you years, not to mention a significant amount of money. After all, many of us cannot afford to spend 5-7 years getting a PhD while balancing work and personal commitments.

Benefits and Challenges of Short Online Doctoral Programs

The key benefit of short doctoral programs is earning a PhD while saving a considerable amount of time and money . You’ll also be able to enter the job market with your doctoral qualification much earlier.

On the other hand, it can be challenging to complete a doctorate in such a short period , often making your studies rather intense. However, if you’re willing to work hard for these short years, you will be able to enjoy the many benefits of having the letter “PhD” after your name.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the shortest doctoral program online.

You won’t find a doctoral program that can be completed in less than a year. Chatham University’s DNP (Doctor of Nursing Practice) and Breyer State Theology University’s Ethereal Accelerated Doctor of Psychology in Grief Counseling are two of the few, if not only, programs currently available that you can complete within a year. However, you can complete some in a little over a year or two years.

Can you Get a PhD in 1 Year?

Very few universities provide PhD programs that can be completed in exactly one year. Even many programs referred to as “1-year PhDs” actually take a little more to complete and up to two years. However, several doctorates can be completed within a year or two, though not across all disciplines.

What is the Quickest Doctorate Degree to Get?

Chatham University’s DNP (Doctor of Nursing Practice) is probably the quickest PhD you can get today, as you can finish it in 12 months. Breyer State Theology University’s Ethereal Accelerated Doctor of Psychology in Grief Counseling also takes only one year.

How Can an Online Program Help Accelerate the Doctorate-Earning Process?

On-campus programs typically have a rigid structure and fixed program duration, usually meaning you have to complete them within around three and seven years. On the other hand, many online programs give you the flexibility to go at your own pace. This often means that you can choose to accelerate through the courses fast and complete the program in a shorter period of time.

Are Fast Doctorate Programs as Good as Regular Programs?

You can’t make a direct comparison between fast doctoral programs and regular programs. Regular programs go at a slower pace, so you get plenty of time to study, observe, reflect, and experiment with what you’re learning.

On the other hand, fast doctoral programs involve a more intense type of study and, arguably, you need to put in more effort. However, these short programs also allow you to gain a valuable doctorate qualification and take your career to the next level in a comparatively short period of time.

Final Thoughts

Though rapid PhD programs are broadly called one-year programs, not all can be completed within one year. Many universities provide PhD programs that you can complete within two years. The best 1-year PhD programs online are an excellent way to earn a doctoral degree with minimal disruption to your work and personal life.

If you’re interested in exploring other PhD programs, take a look at our guides on the best PhD programs in marketing , psychology , and history .

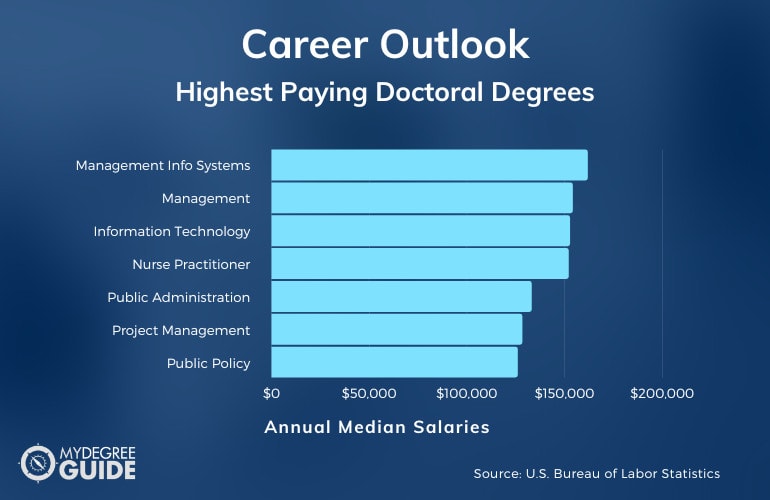

Related: Top 10 Highest Paying PhD Degrees in 2022

Lisa Marlin

Lisa is a full-time writer specializing in career advice, further education, and personal development. She works from all over the world, and when not writing you'll find her hiking, practicing yoga, or enjoying a glass of Malbec.

- Lisa Marlin https://blog.thegradcafe.com/author/lisa-marlin/ 12 Best Laptops for Computer Science Students

- Lisa Marlin https://blog.thegradcafe.com/author/lisa-marlin/ ACBSP Vs AACSB: Which Business Program Accreditations is Better?

- Lisa Marlin https://blog.thegradcafe.com/author/lisa-marlin/ BA vs BS: What You Need to Know [2024 Guide]

- Lisa Marlin https://blog.thegradcafe.com/author/lisa-marlin/ The 19 Best MBA Scholarships to Apply for [2024-2025]

Top 10 Best PhD in Engineering Programs [2024]

Top 10 best ux design graduate programs in 2024, related posts.

- The Sassy Digital Assistant Revolutionizing Student Budgeting

The 18 Best Scholarships for Black Students in 2024-2025

The 19 Best MBA Scholarships to Apply for [2024-2025]

10 Best Lap Desks for Students in 2024

Top 10 Best Online CRNA Programs

Best Online MBA in Florida: Top 7 Choices [2024 Review]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

- How New Grads Research Companies to Find Jobs

- Computer Science Graduate Admission Trends: Annual Results

- The Best Academic Planners for 2024/2025

- Experience Paradox: Entry-Level Jobs Demand Years in Field

© 2024 TheGradCafe.com All rights reserved

- Partner With Us

- Results Search

- Submit Your Results

- Write For Us

The 20 Shortest Doctoral Programs Available

Find your perfect school.

According to PremiumSchools’ chief editor, Malcolm Peralty, “These speedy doctoral programs are your fast track to becoming a leader in what you love. Dive into a world of valuable knowledge, grab those must-have skills, and step out as the go-to expert in your field. Your shortcut to a successful career is right here, ready and waiting!”

With the rapid innovation of education, many academic institutions offer accelerated or shortest doctoral programs in various academic disciplines. Reputable colleges and universities are known for their state-of-the-art resources and tools, facilities, research works, and funding to support professional students.

The following article has been reviewed by Malcolm Peralty

Quick Summarization of the Shortest Doctoral Programs Available Completing the shortest doctoral program is an important aspect of professional students wanting to advance in the current roles of their profession. Since they come with convenience and flexibility, doctoral programs with shorter lengths allow students to work and study without compromising their obligations. These programs also provide non-traditional doctoral students and career shifters with excellent alternatives, especially those who can’t afford traditional doctoral programs or don’t have the luxury of time to complete their graduate studies.

While doctorate studies are considered the culminating term that marks students’ finale of their academic venture, they often require a lot of discipline, effort, time, and resources to obtain. Doctorate credentials are highly desired for professional students wanting to pursue advanced roles or participate in high research activities.

The 20 Shortest Doctorate Careers and School Selections

Let’s get started!

Doctorate in Psychology/General Psychology

Unlike the traditional equivalent, the online Doctorate in Psychology or Doctorate in General Psychology is one of the shortest doctoral programs available. Instead of completing the 6- to 8-year program, accelerated doctorate in psychology programs can be completed in less than three years.

This online program is a terminal degree that helps professional students understand how people behave and think, covering various specializations, including clinical psychology, health & wellness psychology, sport & performance psychology, and business psychology.

The online Doctorate in Psychology program is a heavy research-based academic program, emphasizing research and development of analytical and critical thinking proficiencies. Although each school has different study plans, some of the most common sets of coursework include:

- ethics and multicultural issues

- quantitative research methods

- qualitative analysis

- counseling theories

- tests and measurements

Doctoral students should also expect dissertations and practicums to be a part of the doctorate program’s culminating requirements.

Doctoral programs in Psychology help prepare students for numerous career opportunities in consultancy, academia, research, organization, healthcare, and private practices.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Psychology:

- Capella University

- The University of Arizona

- Walden University

Doctorate in Behavioral Health

With an average completion period of three years, the Doctorate in Behavioral Health is one of the shortest doctoral programs in psychology. It is designed for licensed, working clinical professionals interested in furthering their education and knowledge, offering holistic medical services to help individuals improve their well-being through behavioral changes.

Professional students pursuing an online Doctorate in Behavioral Health will receive advanced training and learning opportunities in entrepreneurship, medical literacy, and behavioral interventions. They will learn in-depth how mental health affects their clients’ overall well-being and discover the different approaches to resolving issues through counseling, therapies, behavioral interventions, and other clinical approaches.

Graduates with DBH credentials don’t have licensing requirements. However, they are required to have certifications in the practice of their profession. They also participate in and conduct extensive research studies that highlight the behavioral and mental health aspects. Unlike licensed psychologists and psychiatrists, DBH graduates aren’t allowed to diagnose clients with mental health issues.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Behavioral Health:

- Arizona State University

- Cummings Graduate Institute

- Freed-Hardeman University

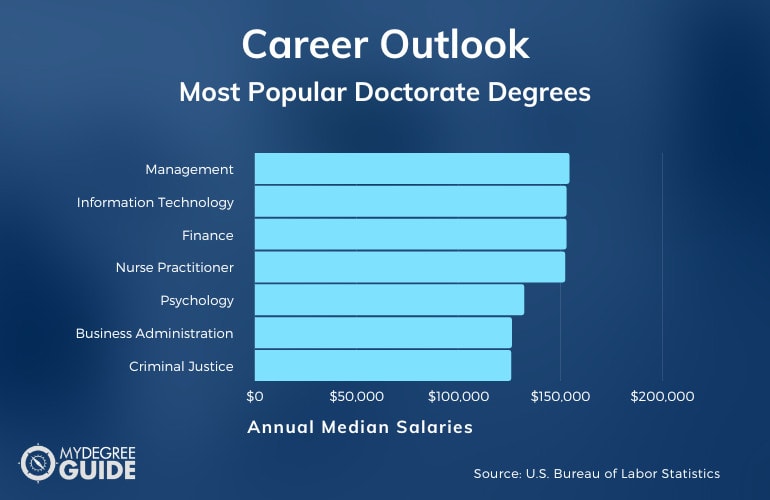

Doctorate in Business Administration

Many schools offer a variety of online Doctorate in Business Administration (DBA), making it one of the most popular and shortest doctoral programs available. It is a doctorate program that prepares students for management and leadership roles in different organizations within the local and global markets.

The DBA program is ideal for professional students desiring advanced studies for career advancements in business, including government sectors, non-profit organizations, and for-profit companies. Graduates can also work in the academe as professors, deans, and other school administrative roles.

Unlike MBA programs, the Doctorate of Business Administration program has a more exclusive curriculum. Although most schools offer online coursework, some will require in-person residencies during summer terms. Professional students are expected to complete a set of required courses, dissertation work, comprehensive examination, and final defense as part of the program requirements of their DBA programs.

Many schools also allow students to specialize in their preferred academic discipline, including marketing, management & organizations, leadership, information technology management, accounting, or finance. Students who are more inclined to work in the field of education can also pursue an online Ph.D. in Business Administration, focusing more on research work rather than applied learning.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Business Administration:

- Hampton University (Hybrid)

- National University

- Trident University

Doctor of Nursing Practice

One of the most popular doctoral programs offering fast-tracked learning is the Doctor of Nursing Practice. It is an ideal program for working nurse practitioners, helping them learn more about evidence-based practices.

Through the online Doctor of Nursing Practice program, students will have advanced knowledge of complex decision-making, management, and healthcare practices. Depending on the students’ learning commitments and pace, the online Doctor of Nursing Practice program can be completed within two years on average.

Considered a professional, practice-focused doctorate program, the online Doctor of Nursing Practice program will prepare nursing professionals to be industry leaders who deliver advanced-level nursing care and state-of-the-art healthcare outcomes.

Apart from advanced clinical roles, pursuing the Doctor of Nursing Practice program will help students conduct teaching and research initiatives in higher education. Doctor of Nursing Practice graduates complete a set of coursework that emphasizes healthcare ethics, statistical analysis, organizational social and behavioral policies, and evidence-based research and practice.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctor of Nursing Practice:

- Duquesne University

- The Pennsylvania State University

- The University of Alabama

Doctorate in Management

Completing a Doctorate in Management program is possible in less than three or four years, making it a popular option for professional students who prefer the shortest doctoral programs available. Many schools offer transfer-friendly Doctorate in Management programs that combine highly desirable skills in technology and communication with core technical components of quality research. It is a terminal degree that prepares students for various rewarding professions in the public and private sectors.

Professional students will develop crucial writing and research skills to publish a dissertation throughout the online Doctorate in Management program. Each dissertation of students will highlight their proficiencies to identify a particular area of interest within the modern workplace, test their hypothesis in real-world applications, and develop effective solutions to specific business-related challenges.

Some schools offer a variety of concentrations to choose from implemented into the online Doctorate of Management program, including information technology, human resource management, conflict management, and strategic management.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Management:

- Franklin University

- Indiana State University

- Sullivan University

Doctor of Occupational Therapy

Given that the online Doctor of Occupational Therapy program can be completed within 18 to 24 months, it is one of the shortest doctoral programs sought-after by students in the field. It is a post-professional occupational therapy program designed for licensed occupational therapists pursuing advanced skills and expertise applicable in the workplace.

While most schools offer online doctoral programs in Occupational Therapy, their programs are integrated with on-campus opportunities. They provide students with a space to present their work to various professional audiences, participate in engaging services, and collaborate with professional leaders within the industry.

All courses are evidence-based, advocating a wide spectrum of knowledge of certain topics, including quality improvement, social policy & disability, educational theory & practice, theories of change, and health promotion & wellness.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctor of Occupational Therapy:

- Fairleigh Dickinson University

- University of Pittsburgh

Doctor of Public Administration

Professional students with a Doctor of Public Administration program have earned their doctorate credentials within three to four years. Considered one of the shortest doctorate programs, the DPA program only requires a minimum of 49 credit hours of coursework and dissertation work.

The doctorate program is designed to develop the skills and expertise of innovative leaders who prefer maximizing impact in non-profit, private, and public organizations.

While each university has a unique set of coursework requirements, most online Doctor of Public Administration programs include courses in employment discrimination law, ethics, and social justice, government regulations and administrative law, leadership in public sectors, and introduction to public service management.

Each course is developed to meet the needs of professional students seeking advanced knowledge in addressing unique and complex issues of organizations at the local, state, and federal levels. Developed with a holistic curriculum, the DPA program will highlight the essential components of social service, health management, policy, governance, criminal justice, and business.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctor of Public Administration:

- California Baptist University

- Old Dominion University

- University of Illinois-Springfield

Doctorate in Educational Leadership

The Doctorate of Educational Leadership is primarily designed for working professionals, allowing students to complete their doctorate studies in two years in a full-time learning format. Like the Doctorate in Business Administration, the online Ed.D. in Educational Leadership is one of the most popular options for students seeking shorter doctorate programs.

The Ed.D. in Educational Leadership program helps prepare innovative leaders who have the knowledge and skill set to oversee complex organizations through uncertain times. While many students assume that the program is only applicable to education, many schools have offered an interdisciplinary doctorate program in Educational Leadership.

Some of the online Doctorate in Educational Leadership offer specializations in Sport Leadership, Special Education Leadership, Nursing Education, Human Resource Development, Disaster Preparedness & Emergency Management, Global Education, and Health Communication & Leadership.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Educational Leadership:

- Drexel University

- Louisiana State University

- Spalding University

Doctorate in Public Policy

The Doctorate in Public Policy program is an excellent option for professional students seeking advanced roles in Education and non-profit, public, and government sectors. It is a practitioner-based terminal doctorate program that highlights a set of coursework, developing students’ problem-solving, communication, management, and leadership skills.

With an average completion time of 36 months, the online Doctorate in Public Policy program is considered one of the shortest doctorate programs available. It is an academic doctorate program that builds upon students’ expertise and skills in the development of applied research skills essential for professional students working in public administration.

Although program requirements vary per school, some of the most common include foundational, core and elective courses, writing assessments, residency programs, and dissertation requirements. Some schools also offer a variety of specializations for a Doctorate in Public Policy, including social policy, national security policy, foreign policy, education policy, and economic policy.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Public Policy:

- Liberty University

- Valdosta State University

Doctorate in Social Work

Professional students enrolled in the online Doctorate in Social Work program can receive their degrees in less than three years. It is designed for experienced clinical social workers with diverse professional experience, learning styles, and academic goals.

Through the doctorate program, students will develop characteristics of both scholars and practitioners. They also adopt the disciplinary habits of scholars through different methodological tools and rigorous study.

Regardless of professional background, the Doctorate in Social Work program will prepare students to pursue a variety of social work career pathways. It is a terminal degree with a clinically-driven curriculum, providing students with advanced practice methods and clinical overview essential to succeed.

Given that it is one of the shortest doctorate programs, professional students pursuing the DSW degree will only require a set of coursework and capstone projects. Depending on the nature of their program, some students will complete a leadership practicum and a teaching practicum.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Social Work:

- Simmons University

- University of Louisville

- University of Southern California

Doctor of Theology or Ministry

Design for professional students in religious studies, the Doctor of Theology or Ministry program will provide students with a practice-focused academic degree that focuses on solving real-world ministry or theological problems with advanced research and practice. Many online schools offer a Doctor of Theology or Ministry program that helps equip students with essential skills in the practice of Christianity.

Many students can already complete their Doctor of Theology or Ministry degree within 24 months, making it one of the shortest doctorate programs in Religious Education.

Students will immerse themselves in an in-depth journey through the New and Old Testaments through the program. It is an academic degree that will help develop students’ skills in bibliographies, theological methodologies, and doctorate-level writing and research.

Students may also choose a concentration in Theology, including Pastoral Theology, Theological Apologetics, Systematic Theology, Biblical Theology, and Church History.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctor of Theology or Ministry:

- Regent University

- Trinity College of the Bible & Theological Seminary

Doctorate in Organizational Leadership and Change

Professional students interested in enrolling in one of the shortest doctorate programs available shouldn’t miss the Doctorate in Organizational Leadership and Change program. It is an academic program that will prepare students to explore a diverse range of solution-building initiatives for complex social challenges.

As a terminal doctorate, the Doctorate in Organizational Leadership and Change program features an extensive research-based study plan. It is a holistic, interdisciplinary program covering organizational behavior, business analytics, research design, statistics, and business methodologies and theories.

Due to the nature of the program, many schools require at least three years of professional experience for students to enroll. After completing the doctorate program, graduates will become effective leaders in various professional settings, including healthcare organizations, academia, non-profits, businesses, and ministries.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Organizational Leadership and Change:

- Adler University

- Vanderbilt University

Doctorate in Healthcare Management or Administration

The Doctorate in Healthcare Management/Administration is one of the shortest doctorate programs designed for mid-to senior-level professionals to help them perform applied research in the healthcare setting. Students will become knowledgeable in performing and capitalizing on practice-based research, leading a diverse range of institutions, and shaping public health policies through the doctorate program.

The doctorate program can be completed in three years, depending on students’ pace and commitment. While schools have different curricula for their doctorate programs, the majority of Doctorate in Healthcare Management degrees will require the completion of the core, elective, and foundational courses, dissertations, and comprehensive examinations.

After graduation, professional students will focus more on achieving leadership in healthcare management, ethics of healthcare, healthcare information systems, and healthcare practices and theories. Working as healthcare consultants, healthcare data analysts, pharmaceutical product managers, or hospital CEOs are some of the career pathways for graduates with Doctorate in Healthcare Management credentials.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Healthcare Management or Administration:

- California Intercontinental University

- Loyola University Chicago

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Doctorate in Physical Therapy

A list of the shortest doctorate programs wouldn’t be complete without the Doctorate in Physical Therapy program. With one to three years of completion time, the doctorate program is designed for licensed physical therapists and physiotherapists, providing industry-standard experience, skills, and knowledge.

It is an ideal program for professional students seeking to maintain their relevance while pursuing the practice of their profession in the field of physiotherapy or physical therapy.

Through the program, professional students will take control of various therapeutic procedures, including diagnosis and implementation of physical therapy treatments tailored to every patient’s unique requirements. Its curriculum features a set of coursework in diagnostic imaging, foundations of autonomous practice, pathophysiology, pharmacology, and global healthcare issues.

Apart from coursework completion, students must accomplish practicum requirements in their chosen field of specialty areas.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Physical Therapy:

- AT Still University of Health Sciences

- Northeastern University

Doctorate in Education

Another option for educators and aspiring school administrators pursuing the shortest doctorate programs available is the Doctorate in Education program. The online, accelerated doctorate program can be completed within 36 months, depending on the student’s pace and preferences.

The doctorate program will develop an in-depth understanding of the educational process and build a skill set applicable to educational leadership settings. It is a doctorate program designed for experienced and skilled educators and other aspiring professionals in learning and development career positions.

Integrated with practitioner-oriented learning, professional students will become transformative leaders with a diverse range of expertise in organizational change, learning & teaching, and curriculum development.

Completing the Doctorate in Education program will equip graduates with the essential skills and knowledge to manage and lead positive transformations in community programs, non-government and government sectors, corporations, and academic systems.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Education:

- Baylor University

- Johns Hopkins University

- Marymount University

Doctorate in Counselor Education and Supervision

The Doctorate in Counselor Education and Supervision is another popular option for students seeking the shortest doctorate programs in counseling or psychology. Although the doctorate program has an average completion time of three to four years, many universities offer accelerated, web-based programs that can be completed within 24 months.

Professional students with CACREP-accredited master’s degrees can also transfer academic credits, making it the shortest way possible to complete their doctorate studies.

The majority of the curriculum is designed and aligned with the standards administered by the Council of Accreditation for Counseling & Related Educational Programs. It is a doctorate program that prepares graduates and other professionals to become practitioners, researchers, supervisors, and counselor educators in various clinical and educational settings.

The academic program will also provide graduates with the necessary credentials and knowledge to assume leadership roles in the counseling profession.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Counselor Education and Supervision:

- Adam State University Colorado

- Antioch University (Flexible, Low Residency)

- University of the Cumberlands

Doctorate in Criminal Justice

The Doctorate in Criminal Justice is one of the rarest doctorate programs available in the country, with only a few schools offering this type of program. It is a unique doctorate program that will explore and address the demand for highly skilled criminal justice practitioners in the US.

The doctorate program is also designed for professional students seeking teaching opportunities and other high-level positions within various educational and criminal justice systems. Many distance learners can complete their Doctorate in Criminal Justice credentials within two years of full-time learning.

Through the doctorate program, Criminal Justice majors will strengthen their skills in policy implementation, in-depth analysis, and evaluation for criminal justice practitioners. They will have an in-depth understanding of real-world problems concerning the criminal justice field, including reducing recidivism of cases, wrongful convictions, police use-of-force, and federal consent decrees.

Apart from online coursework completion, professional students will accomplish residency programs, dissertations, and comprehensive examinations.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Criminal Justice:

- California University of Pennsylvania

- Saint Leo University

Doctorate in Information Technology

Given that Information Technology is a rapidly evolving field, the Doctorate in Information Technology is a multidisciplinary academic program designed for innovative professionals and leaders seeking to advance their abilities, skills, and knowledge in computing systems and technology.

Apart from technical proficiencies, students will also develop relevant information technology abilities essential to influencing and leading a diverse range of organizations. The academic program will offer a comprehensive understanding of foundational theories and practices and how they can be applied to IT.

While every school has its unique program requirements, students can expect to complete foundational, elective, and core courses, specialization, comprehensive examination, dissertation, and residency programs. After completing the doctorate program, graduates can pursue senior-level roles in academic, government, and industrial sectors.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Information Technology:

- City University of Seattle

Doctorate in Grief Counseling

Another rare doctorate program with a shorter program length is the Doctorate in Grief Counseling . Unlike traditional doctorates in counseling, the Grief Counseling post-masters program emphasizes clinical practice instead of counselor supervision and education.

It is a doctorate program that helps professional students explore and gain a holistic understanding of community trauma and disaster, crisis management, critical incidents, forgiveness, inner healing, and grief management. The academic program will also prepare psychotherapists and professional counselors for leadership and advanced clinical practice.

Through a series of coursework, students will become knowledgeable in reviewing models, theories, and research on bereavement, grief counseling techniques, and factors that impact grief. Some of the most common topics include community & crisis counseling, grief & bereavement, counseling ministry for the bereaved, psychotherapy integration, and ethics in grief counseling.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Grief Counseling:

- American International Theism University

- Mississippi College

Doctorate in Public Health

Professional students completing the Doctorate in Public Health can graduate within 36 months, depending on their professional commitments and pace. It is a doctorate program designed for mid to senior-level practitioners with more than five years of professional experience in the related field.

The doctorate curriculum highlights advanced public health studies and training for preparing graduates for leadership positions in practice-based settings, including community-based organizations, international agencies, non-profit organizations, and health departments.

Completing the Doctorate in Public Health program will help graduates foster advanced expertise in evaluating, implementing, and developing evidence-based, applied public health practices.

Best Schools Offering an Online Doctorate in Public Health:

- Indiana University

- University of South Florida (Low Residency)

Frequently Asked Questions

Regardless of the type of doctorate programs you enroll in, completing doctorate credentials requires significant commitment. While fast-tracked or the shortest doctoral programs online help students earn their doctorate in less time, online doctoral degree programs have a rigorous and comprehensive curriculum that can be completed faster, requiring hard work, grit, and dedication.

Professional students can choose any of the two major types of doctorate degrees, namely the following:

A doctorate program that emphasizes theories, data analysis, and research to have an in-depth expansion of a particular area of discipline.

- Professional/Applied Doctorate

It is a doctorate program that emphasizes developing effective professional practices, finding solutions, and applying research methodologies to a diverse range of practical problems within the field of discipline.

Although Ph.D. programs have 8.2 years to complete on average, some online schools offer fast-tracked programs as alternatives. Instead of application, Ph.D. programs focus more on theories. Due to the nature of applied doctorate programs, they’ve become an in-demand type of post-master’s degree since many working professionals prefer applied learning.

While students prefer shorter program lengths and affordability, others have more specific preferences. Each preference and school classification is considered by students when comparing and choosing academic institutions.

Since many professional students have unique criteria and goals for pursuing doctorate studies, it can be challenging to standardize the shortest doctorate programs. Students who prefer individualized and comprehensive mentoring from academic or thesis advisors can enroll in a private institution with a smaller student-to-faculty ratio. However, extra perks often involve more expensive programs.

The completion time for completing doctorate studies, such as the DBA or Doctor of Nursing Practice programs, will depend on students’ commitment and their chosen discipline area. Some universities have an average completion time of more than six years, while others have 5.5 years as the median completion time. With reputable online doctorate programs, students have the option to complete their doctoral studies in as few as three years.

Both traditional and online doctorate programs have become widely accepted in financial aid coverage. Given that doctorate students will complete their FAFSA requirements, they will receive financial assistance to help them complete their doctorate education.

Here are some of the types of financial aid options available for doctorate students:

- Fellowships/Assistantships

- Private Loans

- Scholarships

- Student Loans

- Work-Study Programs

Most students can obtain their doctorate degrees within two years when pursuing online, fast-tracked learning programs. However, some students extend their completion time to more than five years due to their personal and professional obligations.

Although online programs are mostly self-paced, schools have time limits to prevent their students from extending their completion time to almost a decade. The extension will depend on the academic institution and specific areas of study.

However, most universities offer a 7- to 8-year deadline from students’ admission date to their final thesis. At some point, the thesis requirements of students are slowed down due to their circumstances and work schedules.

Given the scenarios, it is hard to standardize exactly how long it will take to complete doctorate studies. Students’ pace and timetable significantly impact obtaining their doctorate degrees on time.

As distance learning has become a trend, many professional students have enrolled in fast-tracked online programs at the doctorate level without leaving their current professions.

For example, the field of education requires candidates to have a doctoral degree when taking on leadership roles in the academe, including associate deans, academic supervisors, and deans. Having doctorate credentials will help candidates negotiate higher salaries, career advancements, or licensing requirements in the business industry.

Here are the most popular academic fields for students pursuing the shortest doctorate online programs:

- Leadership/Management

- Political Science

In Conclusion

Since many colleges and universities offer a variety of online programs, it’s easier and more possible for students to pursue the shortest doctorate programs available. Gone are the days when online, fast-tracked doctorate degrees are not as good as traditional, on-campus degrees.

Many professionals and adult graduate students nowadays prefer the shortest online doctoral degree programs available due to their flexibility, convenience, and program duration, making them ideal for career advancements and career shifters.

On the contrary, pursuing the shortest doctorate program, such as the Doctor of Nursing Practice, can involve additional pressure. Since it is a fast-tracked program, students accomplish more deliverables in less time than traditional doctorate programs.