Essay Papers Writing Online

Master the art of crafting a concept essay and perfect your writing skills.

Every great work of literature begins with a spark of inspiration, a kernel of an idea that germinates within the writer’s mind. It is this concept, this central theme, that serves as the foundation of the entire writing process, guiding the writer along the creative journey. In the realm of academic writing, the concept essay holds a special place, as it requires the writer to explore abstract ideas, dissect complex theories, and present their understanding of a particular concept.

Unlike traditional essays where arguments are made, and evidence is provided, concept essays delve into the intangible realm of ideas, taking the reader on a captivating exploration of abstract concepts. These essays challenge the writer to convey their understanding of a concept without relying on concrete evidence or facts. Instead, they rely on the writer’s ability to provide clear definitions, logical explanations, and compelling examples that elucidate the intricacies of the concept at hand.

Effectively crafting a concept essay requires skillful mastery of language and an astute understanding of how ideas interconnect. It is a delicate dance between the power of words and the depth of thought, where metaphors and analogies can breathe life into otherwise elusive notions. The successful concept essay requires more than merely stating definitions or describing the concept; it necessitates the writer’s ability to engage and captivate the reader, transporting them into the realm of ideas where the abstract becomes clear and tangible.

Mastering the Art of Crafting a Conceptual Essay: Indispensable Suggestions and Instructions

Embarking on the journey of composing a conceptual essay necessitates an astute understanding of the complexities involved. This particular form of written expression empowers individuals to delve deeply into abstract concepts, unravel their intricacies, and articulate their findings in a clear and coherent manner. To accomplish this task with finesse, it is imperative to familiarize oneself with indispensable suggestions and instructions that pave the way to success.

1. Explore Profusely:

- Investigate, scrutinize, and immerse yourself in the vast realm of ideas, allowing your mind to explore a myriad of perspectives.

- Delve into diverse disciplines and subjects, sourcing inspiration and insight from a wide array of sources such as literature, art, philosophy, science, and history.

- Be cognizant of the fact that the more extensive your exploration, the richer your conceptual essay will be.

2. Define Your Focus:

- Once you have gathered an abundant collection of ideas, narrow down your focus to a specific concept that captivates your interest.

- Choose a concept that is both intriguing and stimulating, as this will fuel your motivation throughout the writing process.

- Strive to select a concept that possesses a level of complexity, rendering it ripe for analysis and interpretation.

3. Establish a Clear Structure:

- Prior to commencing the writing process, create a well-structured outline that delineates the key sections and points you wish to convey in your essay.

- Ensure that your essay possesses a clear introduction, body paragraphs that expound upon your chosen concept, and a comprehensive conclusion that ties together your arguments.

- Organize your thoughts in a logical manner, employing effective transitions that allow your essay to flow seamlessly.

4. Support your Claims:

- Avoid presenting mere conjecture or personal opinions; instead, bolster your arguments with credible evidence and examples.

- Cite reputable sources, such as scholarly articles, books, or studies, to lend credibility and authority to your assertions.

- Engage critically with the works of other esteemed thinkers, analyzing their viewpoints and incorporating them into your own exploration of the concept.

5. Polish and Perfect:

- Once you have crafted the initial draft of your conceptual essay, allocate ample time for revision and refinement.

- Engage in meticulous proofreading to eliminate any errors in grammar, punctuation, or syntax that may detract from the overall impact of your work.

- Solicit feedback from trusted peers or mentors, incorporating their suggestions into your final version.

In conclusion, mastering the art of crafting a conceptual essay demands diligent exploration, focused attention, and a commitment to delivering a well-structured and thought-provoking piece of writing. By following these essential tips and guidelines, you can navigate the intricacies of this unique form of expression and develop an essay that both captivates and informs its readers.

Understanding the Purpose of a Concept Essay

Having a clear understanding of the purpose behind writing a concept essay is crucial for creating a successful piece of writing. Concept essays aim to explore and explain abstract ideas, theories, or concepts in a way that is accessible and engaging to readers.

Although concept essays may vary in subject matter, their main objective is to break down complex ideas and make them understandable to a wider audience. These essays often require deep analysis and critical thinking to present the chosen concept in a comprehensive and enlightening manner.

A concept essay goes beyond simply defining a concept but delves deeper into the underlying principles and implications. It requires the writer to provide insight, examples, and evidence to support their claims and demonstrate a thorough understanding of the concept being discussed.

Concept essays also provide an opportunity for writers to explore new and innovative ideas and present them in a thought-provoking way. They allow for personal interpretation and creativity, encouraging writers to examine a concept from different angles and offer unique perspectives.

Furthermore, concept essays can be used as a tool for education and learning, helping readers expand their knowledge and gain a deeper understanding of various concepts. By breaking down complex ideas into more digestible forms, these essays enable readers to grasp abstract concepts and apply them to real-world situations.

In conclusion, the purpose of a concept essay is to convey abstract ideas or concepts in a clear and engaging manner, utilizing critical thinking and analysis. By presenting complex ideas in a comprehensive way, concept essays facilitate understanding and encourage readers to explore and expand their knowledge in the chosen subject area.

Choosing a Strong and Specific Concept

When it comes to crafting a well-written piece of work, selecting a compelling and precise concept is crucial. The concept you choose will serve as the foundation for your essay, shaping the content, tone, and direction of your writing.

Before diving into the process of choosing a concept, it’s important to understand what exactly a concept is. In this context, a concept can be defined as a broad idea or theme that encapsulates a particular subject or topic. It is the main point or central idea that you want to convey to your readers through your essay.

An effective concept should be strong, meaning it should be able to capture the attention and interest of your readers. It should be something that has depth and substance, allowing for exploration and analysis. A strong concept will engage your audience and motivate them to continue reading.

In addition to being strong, your concept should also be specific. It should be focused and clearly defined, narrowing down your topic to a specific aspect or angle. A specific concept will help you maintain a clear direction in your writing and prevent your essay from becoming too broad or unfocused.

To choose a strong and specific concept, start by brainstorming ideas related to your topic. Think about the main themes or issues you want to address in your essay. Consider what aspects of the topic interest you the most and which ones you feel are worth exploring further.

Once you have a list of potential concepts, evaluate each one based on its strength and specificity. Ask yourself whether the concept captures your interest and whether it has the potential to captivate your audience. Consider whether it is specific enough to guide your writing and provide a clear focus for your essay.

By choosing a strong and specific concept, you will set yourself up for success in writing your concept essay. Remember to select a concept that is compelling, focused, and meaningful to you and your readers. With a well-chosen concept, you will be able to create a thought-provoking and engaging essay that effectively conveys your ideas.

Developing a Clear and Coherent Thesis Statement

When crafting an effective essay, one of the most important elements to consider is the development of a clear and coherent thesis statement. The thesis statement acts as the central theme or main argument of your essay, providing a roadmap for your readers to understand the purpose and direction of your writing.

A well-developed thesis statement not only states your main argument but also provides a clear focus for your essay. It helps you organize your thoughts and ensures that your essay remains cohesive and logical. A strong thesis statement sets the tone for your entire essay and guides the reader through your main ideas.

To develop a clear and coherent thesis statement, it is crucial to thoroughly understand the topic you are writing about. Conducting research and gathering relevant information will help you form a solid foundation for your thesis statement. Make sure to analyze different perspectives on the topic and consider any counterarguments that may arise.

Once you have a good understanding of the topic, you can begin brainstorming and drafting your thesis statement. Start by considering the main idea or argument you want to communicate to your readers. Your thesis statement should be concise and specific, clearly conveying your main point. Avoid vague or general statements that lack focus.

In addition to being clear and concise, your thesis statement should also be arguable. It should present a debatable claim that can be supported with evidence and logical reasoning. This allows you to engage your readers and encourages them to consider different perspectives on the topic.

After drafting your thesis statement, it is important to review and revise it as needed. Make sure it accurately reflects the content and direction of your essay. Consider seeking feedback from peers or instructors to ensure that your thesis statement is clear, coherent, and effectively conveys your main argument.

In conclusion, developing a clear and coherent thesis statement is essential for writing an effective essay. It sets the tone for your entire essay, provides a clear focus, and guides the reader through your main ideas. By thoroughly understanding the topic, brainstorming and drafting a concise and arguable thesis statement, and revising as needed, you can ensure that your essay is well-structured and persuasive.

Structuring Your Concept Essay Effectively

Creating a well-organized structure is vital when it comes to conveying your ideas effectively in a concept essay. By carefully structuring your essay, you can ensure that your audience understands your concept and its various aspects clearly. In this section, we will explore some essential guidelines for structuring your concept essay.

1. Introduction: Begin your essay with an engaging introduction that captures the reader’s attention. This section should provide a brief overview of the concept you will be discussing and its significance. You can use an anecdote, a rhetorical question, or a thought-provoking statement to make your introduction compelling.

2. Definition: After the introduction, it is crucial to provide a clear definition of the concept you will be exploring in your essay. Define the concept in your own words and highlight its key characteristics. You may also include any relevant background information or historical context to enhance the reader’s understanding.

3. Explanation: In this section, you will delve deeper into the concept and explain its various elements, components, or features. Use examples, analogies, or real-life situations to illustrate your points and make them more relatable to the reader. Break down complex ideas into simpler terms and highlight the connections between different aspects of the concept.

4. Analysis: Once you have provided a thorough explanation of the concept, it is time to analyze it critically. Discuss different perspectives or interpretations of the concept and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses. Consider any controversies or debates surrounding the concept and present a balanced view by weighing different arguments.

5. Examples and Case Studies: To further support your arguments and enhance the reader’s understanding, include relevant examples and case studies. These examples can be from real-life situations, historical events, or fictional scenarios. Analyze how the concept has been applied or manifested in these examples and discuss their implications.

6. Conclusion: Conclude your concept essay by summarizing your main points and restating the significance of the concept. Reflect on the insights gained from your analysis and offer any recommendations or suggestions for further exploration. End your essay on a thought-provoking note that leaves the reader with a lasting impression.

By structuring your concept essay effectively, you can ensure that your ideas are presented coherently and persuasively. Remember to use clear and concise language, provide logical transitions between sections, and support your arguments with evidence. With a well-structured essay, you can effectively communicate your understanding of the concept to your audience.

Using Concrete Examples to Illustrate Your Concept

One effective way to clarify and reinforce your concept in a concept essay is by using concrete examples. By providing specific and tangible instances, you can help your readers grasp the abstract and theoretical nature of your concept. Concrete examples bring your concept to life, making it easier for your audience to understand and relate to.

Instead of relying solely on abstract theories, you can support your concept with real-life scenarios, research studies, or personal anecdotes. These examples add depth and relevance to your essay, making it more engaging and meaningful.

When choosing examples to illustrate your concept, it is important to select ones that accurately represent the core elements of your concept. Look for examples that exhibit the underlying principles, attributes, or behaviors that are associated with your concept.

For instance, if your concept is “leadership,” you can provide examples of influential leaders from history or modern-day society. These examples can demonstrate the qualities that define effective leadership, such as integrity, communication skills, and the ability to inspire and motivate others.

Additionally, when presenting concrete examples, ensure that they are relevant and relatable to your target audience. Consider the background and interests of your readers and choose examples that they can easily comprehend and connect with. This will enhance the effectiveness of your essay and create a stronger impact.

In conclusion, using concrete examples is a powerful technique for illustrating your concept in a concept essay. By incorporating specific instances, you can bring clarity, relevance, and authenticity to your writing. This approach allows your readers to grasp your concept more easily and appreciate its practical application in real-life scenarios.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

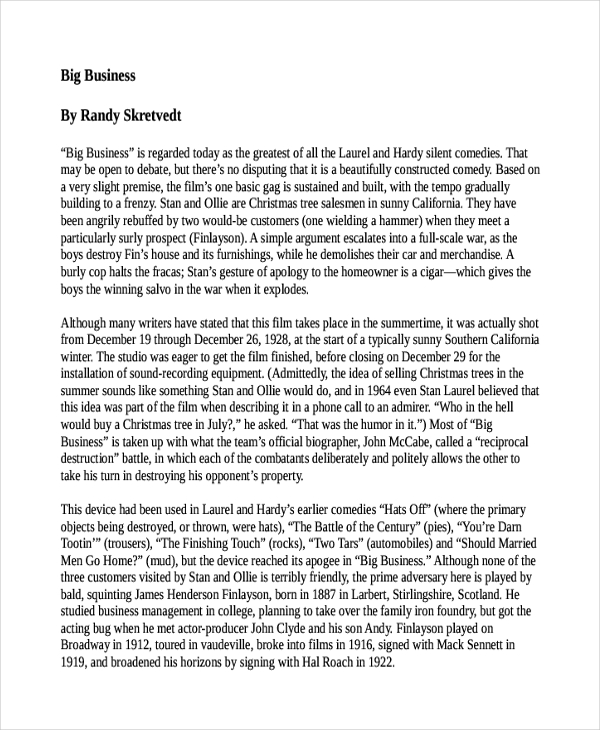

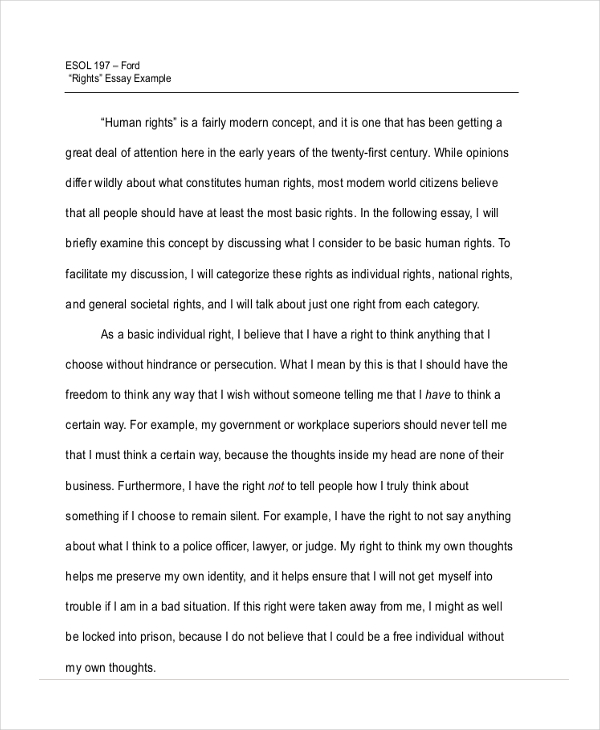

Concept Essay Paper

Concept essay generator.

Every writer has his/her own way of presenting a topic or an idea to the readers. Some of them wants to stir imaginations and make you create characters and places of your own. Others want to provoke your emotions and indulge you into the story. While others want to simply demonstrate a subject.

Essay writing is considered a talent. It requires a creative mind to be able to present thoughts and emotions and put them into writing. And the most difficult part is how to make it appealing to the readers. Knowing how to start an essay is even more difficult because you have to find the right inspiration to write.

What is Concept Essay? A concept essay is a piece writing that is used to present an idea or a topic with the sole purpose of providing a clear definition and explanation. Their usual content are those topics that may have previously been presented but were not given with full emphasis. Others are controversial and timely issues that raises questions but are not given full answers. What is Concept Paper? A concept paper is a brief document written to provide an overview of a project, research, or idea. It outlines the main goals, objectives, and methods of the intended project, serving as a preliminary proposal. Concept papers are often used to seek approval or funding, presenting the project’s significance, potential impact, and feasibility in a concise manner. This document helps stakeholders, such as sponsors or academic committees, understand the essence of the proposed work and decide whether to support it further.

Concept Paper Writing Topics & Ideas

In conceptual writing, the central focus lies on the idea or concept driving the work, positioning it as the cornerstone of the narrative. This approach dictates that all planning and critical decisions are determined in advance, rendering the actual writing process secondary. Essentially, the concept acts as a blueprint, guiding the creation of the text in a manner that is almost mechanical. Through this method, the initial idea transforms into an engine that propels the development of the written piece, underscoring the precedence of thought over the act of writing itself. Below are the topics and ideas of concept writing

- The Evolution of Digital Privacy

- The Psychology Behind Social Media Addiction

- The Impact of Remote Work on Urban Development

- Sustainability in Fashion: A New Trend

- The Future of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

- Cultural Identity in a Globalized World

- The Ethics of Genetic Editing

- The Role of Cryptocurrency in Modern Finance

- Mental Health Awareness in the Workplace

- The Influence of Music on Cognitive Development

- Climate Change and Its Effects on Biodiversity

- The Philosophy of Minimalism and Its Life Benefits

- The Rise of E-Learning and Its Educational Impacts

- Urban Farming: Solutions for Food Security

- Virtual Reality: Transforming Entertainment and Education

- The Gig Economy and Its Impact on Traditional Employment

- Social Entrepreneurship: Business for Social Good

- The Intersection of Art and Technology

- Cybersecurity in the Age of Internet of Things

- The Role of Nutrition in Preventing Chronic Diseases

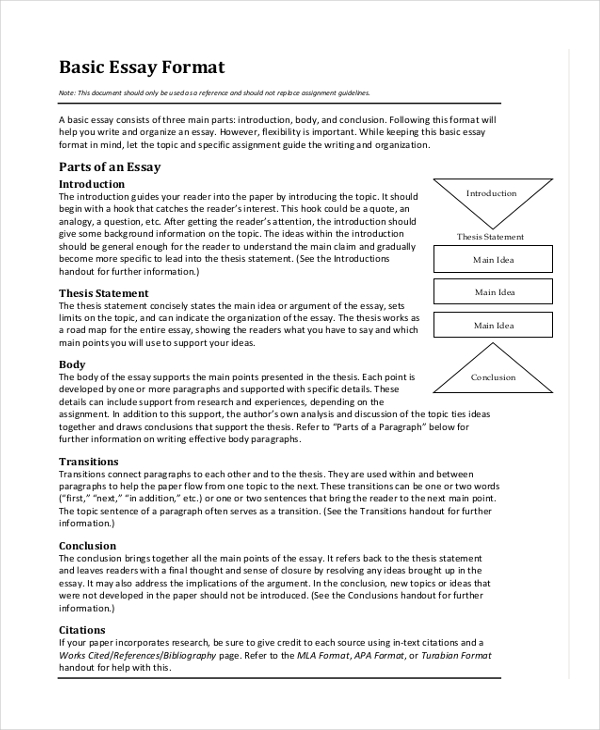

Concept Essay Paper Format

Introduction.

Hook : Start with an engaging sentence to capture the reader’s interest. Background Information : Provide a brief context for the concept you are going to explore. Thesis Statement : Clearly state the concept or idea you will discuss, outlining the main point or argument of your essay.

Body Paragraphs

Each paragraph should focus on a specific aspect of the concept or idea.

Topic Sentence : Introduce the main idea of the paragraph that supports your thesis. Explanation : Offer a detailed explanation of the idea, including definitions, descriptions, and relevant information. Examples and Evidence : Use specific examples, illustrations, or evidence to support your explanations and arguments. This could include statistics, quotes from experts, or real-life scenarios. Analysis : Analyze how the example or evidence supports your topic sentence and thesis, explaining its significance. Transition : Conclude the paragraph with a sentence that smoothly transitions to the next point or paragraph.

Summary of Main Points : Briefly recap the key arguments or explanations presented in your essay. Restatement of Thesis : Reiterate your thesis statement, highlighting how it has been supported through your discussion. Final Thoughts : Offer closing remarks that leave a lasting impression on the reader. This could include implications, future prospects, or a call to action related to the concept.

Concept Paper Example

Enhancing Digital Literacy in Rural Communities: A Pathway to Bridging the Digital Divide The rapid advancement of digital technologies has significantly transformed the way we live, work, and communicate. However, this digital revolution has also led to a widening gap between urban and rural areas in terms of access to technology and digital skills. This concept paper proposes a comprehensive project aimed at enhancing digital literacy in rural communities as a fundamental step toward bridging the digital divide. By equipping rural populations with the necessary digital skills, the project seeks to empower individuals, improve educational outcomes, and unlock economic opportunities. The purpose of this initiative is to develop and implement a scalable digital literacy program tailored to the needs of rural communities. This program will focus on basic computer skills, internet navigation, online safety, and the use of digital tools for education and entrepreneurship. The significance of this project lies in its potential to transform the lives of rural residents, providing them with the skills required to participate fully in the digital world. Objectives of the project include: Assessing the current level of digital literacy in targeted rural areas. Developing a comprehensive digital literacy curriculum that addresses identified needs. Delivering digital literacy training to residents of rural communities through workshops and online modules. Establishing community-based digital hubs equipped with internet access and computing resources. Evaluating the impact of the program on participants’ digital skills, economic opportunities, and educational outcomes. The methodology will encompass a needs assessment to identify specific digital literacy gaps, followed by the development of a curriculum that incorporates both theoretical knowledge and practical skills. Training will be delivered through a combination of in-person workshops and online modules, ensuring broad access. Pre- and post-program assessments will measure the effectiveness of the training. Expected outcomes include improved digital literacy rates among rural populations, increased access to educational and economic opportunities, and enhanced participation in the digital economy. The project aims to establish a model for digital literacy training that can be replicated and scaled in other rural areas. In conclusion, enhancing digital literacy in rural communities presents a critical opportunity to bridge the digital divide and foster equitable access to the benefits of the digital age. This concept paper outlines a clear and actionable plan to empower rural residents with the digital skills necessary for success in a rapidly evolving world.

Concept Essay Outline Sample

penandthepad.com

Concept Essay on Love

professays.com

Concept on Success

nicoletaylor13.weebly.com

Self Concept Essay Example

bestessayhelp.com

Cultural Concept Essay Sample

missouriwestern.edu

Concept Analysis

bristolcc.edu

Concept Essay Format

Business Concept Essay Example

Free Concept Essay

What Are the Steps to Writing a Concept Essay?

One of the things to consider in essay writing is to know how to start an essay. In addition to that, you have to come up with the steps on how to write an effective one.

- Choose a topic. An effective essay is one that presents a more relevant topic. You need to choose the right topic first before you start writing.

- Do your research. You have to back up your claims with factual information from reliable sources. Present at least three to four points for reference.

- Create your outline. The essay outline of your concept essay because readers will consider how your ideas are presented.

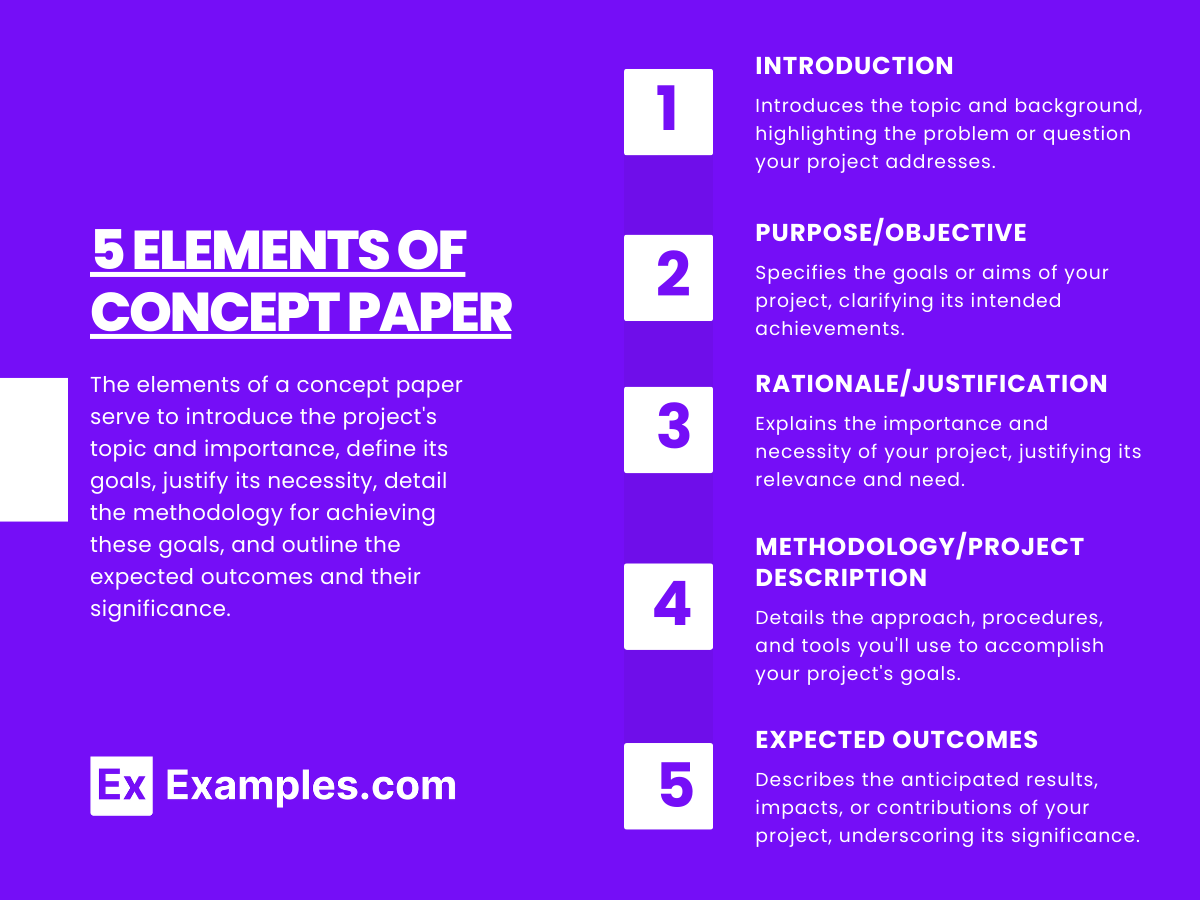

Key Elements of Concept Paper

A concept paper outlines a project or idea, presenting its purpose, significance, methodology, expected outcomes, and, if applicable, budget and timeline. It serves to introduce and justify the project, aiming to secure interest or support by succinctly detailing its goals and potential impact.

The key elements are:

How to Make/ Create Concept Paper

1. choose your topic wisely.

Select a topic that is both interesting to you and relevant to your audience or potential funders. It should address a specific problem, need, or question.

2. Conduct Preliminary Research

Gather information on your topic to ensure there’s enough background material to support your concept. This research will help refine your idea and identify gaps your project could fill.

3. Write the Introduction

Start with a strong introduction that captures the essence of your concept. Include a brief overview of the problem or issue your project intends to address, its significance, and why it is worth exploring or implementing.

4. State the Purpose or Objective

Clearly articulate the purpose or objectives of your project or research. What do you aim to achieve? Be specific about the outcomes you anticipate.

5. Provide Background Information

Offer a detailed background that gives context to your concept. This section should include any relevant research, current findings, and a justification for your project or study.

6. Describe the Project or Research Design

Outline how you plan to achieve your objectives. This includes your methodology, the steps you will take, and the resources you will need. For research projects, specify your research questions, hypothesis, and the methods for data collection and analysis.

7. Discuss the Significance

Explain the potential impact of your project or research. How will it contribute to the field, benefit a specific group, or solve a problem? This section is crucial for persuading readers of the value of your concept.

8. Outline the Budget (if applicable)

If your concept paper is for a project requiring funding, provide an estimate of the budget. Break down the costs involved, including materials, personnel, and any other resources.

9. Set a Timeline

Include a proposed timeline for your project or research. This demonstrates planning and feasibility and helps funders understand the project’s scope.

10. Conclude Your Paper

Summarize the key points of your concept paper, reinforcing the importance and feasibility of your project or research. End with a call to action or a statement of next steps.

Importance of Concept Essay

As we go along the path of discovering new and better ideas that could feed our minds with more useful information, we also need to pause and make sure that these concepts are well explained.

The main importance of a concept analytical essay is to provide a more vivid evaluation as well as explanation of the ideas that may seem ambiguous. We cannot just live in a world where we are fed with information that we are supposed to accept. Remember that we have the freedom to accept what is true and decline what is not. With a concept essay, we can dig deeper into things and find out its true essence.

When do you need a concept paper?

A concept paper is needed when initiating a project, seeking funding, or proposing an idea to stakeholders. It serves as a preliminary outline, presenting the project’s rationale, goals, and methodology in a concise format to gauge interest or secure support.

How is a concept paper different from a research paper?

A concept paper differs from a research paper in its purpose and scope. While a concept paper outlines a project idea, seeking approval or funding with a focus on potential impact and methodology, a research paper presents detailed findings from completed research, including analysis and results.

What is the purpose of a concept essay?

The purpose of a concept essay is to explore and clarify a specific idea or concept. It aims to deepen understanding and stimulate thought by examining the concept from various angles, using examples, definitions, and personal insights to articulate its significance and implications.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Explore the concept essay of happiness: what does it mean and how is it achieved?

Discuss in a concept essay the idea of freedom in the modern world.

Conceptual Analysis: The Cornerstone of Philosophical Inquiry

Table of Contents

Have you ever wondered how philosophers manage to navigate through the dense forest of complex ideas to find clarity and understanding? The secret lies in a method known as conceptual analysis , a philosophical technique that dissects intricate concepts into their elemental parts. Think of it as a mental toolkit that helps us break down big ideas to understand and evaluate them better.

What is conceptual analysis?

At its core, conceptual analysis is the process of examining and clarifying what we mean when we use particular concepts. The aim is to uncover the underlying structure of a concept by asking what conditions must be met for it to apply. This might sound straightforward, but it’s often anything but. Philosophers like John Locke and Immanuel Kant have shown that the way we analyze concepts can have profound implications for how we understand the world and our place in it.

The process of conceptual analysis

Conceptual analysis typically involves several key steps:

- Identifying the concept: This is the starting point where we define which concept we want to analyze.

- Clarifying the concept: Here, we try to articulate what we mean when we use the concept in question.

- Breaking down the concept: We dissect the concept into its fundamental components or attributes.

- Assessing the concept: Finally, we evaluate the concept’s coherence and utility in philosophical discourse.

Locke and Kant: Analytic vs. Synthetic propositions

Two titans of philosophy, Locke and Kant, approached conceptual analysis in distinct ways, particularly when dealing with analytic and synthetic propositions .

Locke’s take on analytic propositions

Locke’s perspective was that analytic propositions are those where the predicate concept is contained within the subject concept. A classic example is the statement “All bachelors are unmarried men.” The concept of being unmarried is part of what we mean by ‘bachelor,’ so the proposition is true by virtue of the meanings of the words involved.

Kant’s revolution with synthetic propositions

Kant, however, introduced the idea of synthetic propositions, which are statements where the predicate concept is not contained within the subject but is connected to it. An example of a synthetic proposition is “All bachelors are unhappy.” Unhappiness is not a defining characteristic of a bachelor, so we must look beyond definitions and into the world to determine the truth of the proposition.

Applying conceptual analysis: Real-world examples

Conceptual analysis isn’t just for armchair philosophers; it has practical applications in many areas including law, ethics , and artificial intelligence .

In law: Interpreting statutes and precedents

When lawyers argue over the interpretation of a law, they are often engaging in conceptual analysis. They must dissect legal concepts to understand precisely what a statute means and how it should be applied to a specific case.

In ethics: Understanding moral concepts

What do we mean when we say something is ‘good’ or ‘just’? Ethicists use conceptual analysis to unpack these terms, which can help us make clearer ethical decisions.

In artificial intelligence: Programming understanding

For AI to “understand” human commands, it must have a framework for analyzing concepts. This often involves creating algorithms that mimic the way humans use conceptual analysis to parse language and ideas.

Challenges and criticisms of conceptual analysis

While conceptual analysis is a valuable tool, it’s not without its challenges and critics. Some argue that our concepts are too fluid and context-dependent for such analysis to be truly effective. Others suggest that focusing too much on language can distract us from engaging with the real substance of philosophical problems.

Conceptual change and evolution

One of the main challenges is that concepts evolve over time. Consider how the concept of ‘privacy’ has changed with the advent of the internet and social media. This dynamic nature of concepts can make any analysis potentially outdated.

Philosophical skepticism about language

Critics like Ludwig Wittgenstein have questioned whether language can ever truly capture the essence of reality, suggesting that conceptual analysis may be fundamentally limited.

Conceptual analysis remains a cornerstone of philosophical inquiry, despite its challenges. By understanding the nuances of this method, we can better appreciate the work of philosophers and apply their insights to our own lives. By dissecting complex ideas into simpler components, we develop a clearer understanding of the intricate tapestry of concepts that form our worldviews.

What do you think? Is there a concept you’ve struggled to understand that might benefit from this kind of analysis? How might conceptual analysis change with the evolution of language and society?

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating / 5. Vote count:

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

Research Methodology

1 Introduction to Research in General

- Research in General

- Research Circle

- Tools of Research

- Methods: Quantitative or Qualitative

- The Product: Research Report or Papers

2 Original Unity of Philosophy and Science

- Myth Philosophy and Science: Original Unity

- The Myth: A Spiritual Metaphor

- Myth Philosophy and Science

- The Greek Quest for Unity

- The Ionian School

- Towards a Grand Unification Theory or Theory of Everything

- Einstein’s Perennial Quest for Unity

3 Evolution of the Distinct Methods of Science

- Definition of Scientific Method

- The Evolution of Scientific Methods

- Theory-Dependence of Observation

- Scope of Science and Scientific Methods

- Prevalent Mistakes in Applying the Scientific Method

4 Relation of Scientific and Philosophical Methods

- Definitions of Scientific and Philosophical method

- Philosophical method

- Scientific method

- The relation

- The Importance of Philosophical and scientific methods

5 Dialectical Method

- Introduction and a Brief Survey of the Method

- Types of Dialectics

- Dialectics in Classical Philosophy

- Dialectics in Modern Philosophy

- Critique of Dialectical Method

6 Rational Method

- Understanding Rationalism

- Rational Method of Investigation

- Descartes’ Rational Method

- Leibniz’ Aim of Philosophy

- Spinoza’ Aim of Philosophy

7 Empirical Method

- Common Features of Philosophical Method

- Empirical Method

- Exposition of Empiricism

- Locke’s Empirical Method

- Berkeley’s Empirical Method

- David Hume’s Empirical Method

8 Critical Method

- Basic Features of Critical Theory

- On Instrumental Reason

- Conception of Society

- Human History as Dialectic of Enlightenment

- Substantive Reason

- Habermasian Critical Theory

- Habermas’ Theory of Society

- Habermas’ Critique of Scientism

- Theory of Communicative Action

- Discourse Ethics of Habermas

9 Phenomenological Method (Western and Indian)

- Phenomenology in Philosophy

- Phenomenology as a Method

- Phenomenological Analysis of Knowledge

- Phenomenological Reduction

- Husserl’s Triad: Ego Cogito Cogitata

- Intentionality

- Understanding ‘Consciousness’

- Phenomenological Method in Indian Tradition

- Phenomenological Method in Religion

10 Analytical Method (Western and Indian)

- Analysis in History of Philosophy

- Conceptual Analysis

- Analysis as a Method

- Analysis in Logical Atomism and Logical Positivism

- Analytic Method in Ethics

- Language Analysis

- Quine’s Analytical Method

- Analysis in Indian Traditions

11 Hermeneutical Method (Western and Indian)

- The Power (Sakti) to Convey Meaning

- Three Meanings

- Pre-understanding

- The Semantic Autonomy of the Text

- Towards a Fusion of Horizons

- The Hermeneutical Circle

- The True Scandal of the Text

- Literary Forms

12 Deconstructive Method

- The Seminal Idea of Deconstruction in Heidegger

- Deconstruction in Derrida

- Structuralism and Post-structuralism

- Sign Signifier and Signified

- Writing and Trace

- Deconstruction as a Strategic Reading

- The Logic of Supplement

- No Outside-text

13 Method of Bibliography

- Preparing to Write

- Writing a Paper

- The Main Divisions of a Paper

- Writing Bibliography in Turabian and APA

- Sample Bibliography

14 Method of Footnotes

- Citations and Notes

- General Hints for Footnotes

- Writing Footnotes

- Examples of Footnote or Endnote

- Example of a Research Article

15 Method of Notes Taking

- Methods of Note-taking

- Note Book Style

- Note taking in a Computer

- Types of Note-taking

- Notes from Field Research

- Errors to be Avoided

16 Method of Thesis Proposal and Presentation

- Preliminary Section

- Presenting the Problem of the Thesis

- Design of the Study

- Main Body of the Thesis

- Conclusion Summary and Recommendations

- Reference Material

Share on Mastodon

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Belitung Nurs J

- v.9(5); 2023

- PMC10600704

Beyond the classics: A comprehensive look at concept analysis methods in nursing education and research

Joko gunawan.

1 Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

2 Belitung Raya Foundation, Manggar, East Belitung, Bangka Belitung, Indonesia

Yupin Aungsuroch

Colleen marzilli.

3 University of Maine, School of Nursing, Orono, ME USA

Associated Data

Not applicable.

This editorial presents eight concept analysis methods for use in nursing research and education. In addition to the two classical methods of Walker and Avant’s and Rodgers’ concept analysis approaches that are typically utilized in nursing education and briefly discussed within this editorial, six additional methods are also presented including Schwartz-Barcott and Kim’s Hybrid model, Chinn and Kramer’s approach, Simultaneous Concept Analysis, Pragmatic Utility, Principle-Based Concept Analysis, and Semantic Concept Analysis. By familiarizing nursing educators, researchers, and students with these methods, educators can enhance their critical thinking and understanding of complex nursing concepts, preparing them for enhanced, multi-faceted contributions to nursing science.

Introduction

Concepts serve as abstract mental constructs, mental images of phenomena, units of meaning, or building blocks of theory, intended to summarize specific aspects or elements of the human experience (Chinn & Kramer, 1995 ; Penrod & Hupcey, 2005 ; Smith & Mörelius, 2021 ). However, for theory to be grounded in, and arise from real-world nursing practice, it is essential to bring clarity to the concepts under examination, known as concept analysis (Smith & Mörelius, 2021 ).

The primary aim of a concept analysis is to carefully study, clarify, develop, and critically assess a particular concept (Smith & Mörelius, 2021 ), all to attain a more profound and detailed understanding of the concept. While various methodologies for concept analysis are discussed in the nursing scientific literature, the most prominent approaches used among nursing students include the classical methods of Walker and Avant’s technique (Walker & Avant, 2014 ) and Rodger’s evolutionary approach (Rodgers, 1989 ).

This heavy reliance on these two methodologies raises an important question: are nursing students aware of the spectrum of available concept analysis methodologies rather than just the two common approaches? To our knowledge, teaching focuses mainly on Walker and Avant’s concept analysis and Rodgers’ evolutionary method in doctoral education influencing the analytical patterns of educators, researchers, and students. As a result, many students might not be familiar with other strategies for concept analysis. With this context in mind, this editorial article aims to provide a concise overview of various approaches that can be employed to conduct a thorough concept analysis.

Types of Concept Analysis Methods

1. walker and avant’s concept analysis.

Walker and Avant’s model presents a step-by-step method for analyzing a concept and creating a clear definition of the concept in question (Walker & Avant, 2014 ). It has eight stages based on Wilson’s techniques (Wilson, 1973 ). It starts by choosing a concept related to research goals and outlining the purpose of the analysis. Various uses of the concept in nursing are studied to understand its significance. Identifying defining attributes is crucial, serving as the concept’s core and distinguishing it from related ideas (Walker & Avant, 2014 ). While some researchers spot attributes through repeated terms, others use content analysis, thematic analysis, keyword clustering, or summative content analysis.

To make the concept more transparent, a model case is constructed as a “real-life” example, illustrating all main attributes. Additional cases, including borderline, related, and contrary examples, further explain the concept’s variations, refining its boundaries, and addressing differences from the model case (Walker & Avant, 2014 ). Antecedents and consequences are pinpointed. Empirical referents, or measurable indicators, ensure the concept’s practical applicability and verifiability (Walker & Avant, 2014 ).

It is noted that the method’s strengths lie in its systematic and organized approach, facilitating replication by other researchers. It is also tailored for nursing concepts, ensuring its relevance and practicality. However, the method may potentially oversimplify complex concepts, limit philosophical foundation, overlook contextual considerations and qualitative insights, and overclaim the operational definition of the concept (Weaver & Mitcham, 2008 ). Thus, researchers should consider complementing the method with other approaches to understand the concept under study better.

2. Schwartz-Barcott and Kim’s Hybrid Model

This model aims to refine concepts for theory development, builds upon Wilson’s method, and provides a learning platform for graduate students. As the term “hybrid” suggests, this model connects theoretical analysis and practical observation. It is built upon insights from three knowledge domains: the philosophy of science, the sociology of theory development, and participant observation, or field research. The method comprises three phases: Theoretical, Field Work, and Analytical (Schwartz-Barcott, 2000 ).

The Theoretical Phase establishes a foundation by selecting a loose concept definition, starting a literature review, and outlining essential elements. The Field Work Phase validates and refines through empirical observations and using standard qualitative research steps focusing on definition and measurement. The minimum data collection time is 2.5 to 3 months. The Analytical Phase involves comparing findings, and it also includes addressing the concept’s nursing relevance, justification, support in literature, theory, and data (Schwartz-Barcott, 2000 ).

The Schwartz-Barcott and Kim’s hybrid model provides a comprehensive and structured approach to concept analysis, combining theoretical and empirical aspects. Like any qualitative research approach, this hybrid model has limitations, such as potential bias and limited generalizability to broader groups or settings.

3. Chinn and Kramer’s Method

Chinn and Kramer [Jacobs] introduced their concept analysis methodology in 1983, crediting its origins to Wilson. The steps outlined by Chinn and Kramer in 1991 contrast with the method proposed by Walker and Avant by excluding “identifying antecedents and consequences” and “formulating criteria.” Instead, they formulate criteria after collecting and analyzing data, considering values and social context (Hupcey et al., 1996 ). They also include cases as “data sources” and incorporate various potential data sources for analysis, such as visual images, contemporary and traditional literature, musical expressions, poems, and insights from individuals interacting with the concept.

Chinn and Kramer’s method offers a less linear process that involves more interaction between steps. Their purpose of this technique is to better understand the concept by looking at the term used, what it represents, the linked emotions, principles, and perspectives. Chinn and Jacobs ( 1987 ) also describe the outcomes of a concept analysis as tentative, acknowledging that the concept’s definition and criteria for presence in a specific context may change as new evidence emerges. Chinn and Kramer’s method aligns more closely with Wilson’s approach than Walker and Avant’s interpretation. The method creates cases to find characteristics linked with the concept and distinguish criteria that genuinely belong to it from those that don't. They also explore the social situation and values related to the concept, similar to Wilson. Chinn and Kramer anticipate that criteria should be developed only after examining all these aspects. While Chinn and Kramer consider various factors in concept analysis, they may not stress the same level of intellectual rigor as Wilson (Hupcey et al., 1996 ). Chinn and Kramer’s method of concept analysis consists of choosing, establishing a purpose, investigating data, and developing validation criteria for the concept (Weaver & Mitcham, 2008 ).

4. Rodgers’ Evolutionary Concept Analysis

Rodgers' evolutionary concept analysis is an inductive approach that highlights how concepts evolve over time and are impacted by their context (Rodgers, 1989 ). This approach consistently examines a concept’s context, surrogate and related terms, antecedents, attributes, examples, and consequences. This approach does not offer definitive conclusions but serves as a guide for further research (Rodgers, 1989 ). In essence, Rodgers presents a cyclical model that accommodates the ever-changing nature of concepts.

Rodgers suggests six preliminary activities ( Table 1 ), which can occur simultaneously during the study. Unlike Walker and Avant, the research process is non-linear, rotational, and flexible (Ghadirian et al., 2014 ; Rodgers, 1989 ). The activities involve recognizing the concept of focus and its linked terms, choosing a suitable context, gathering data to determine the traits of the concept and its context, analyzing the collected information, pinpointing a prime example of the concept if applicable, and creating hypotheses and potential outcomes for advancing the concept's understanding. These stages represent the activities that should occur during the study rather than a continuous process. Rogers’ approach emphasizes detailed analysis and focuses on gathering and analyzing raw data, particularly within a profession’s specific social and cultural context (Ghadirian et al., 2014 ; Rodgers, 1989 ).

Summary of the steps/phases/principles of each concept analysis method

| Methods | Steps/Phases/Principles |

|---|---|

| Walker and Avant’s Concept Analysis | |

| Schwartz-Barcott & Kim’s Hybrid Model | |

| Chinn & Kramer’s Method | |

| Rodger’s Evolutionary Method | |

| Simultaneous Concept Analysis | |

| Pragmatic Utility | |

| Principle-Based Concept Analysis | Principles: |

| Semantic Concept Analysis |

Despite its strengths, such as the inductive approach, flexibility and adaptability, and the utilization of comprehensive data sources, the findings derived from Rodger’s concept analysis might not always be readily generalizable to other contexts or populations, as the focus on specific social and cultural contexts restricts the broader applicability of the results. Furthermore, the iterative and flexible nature of the analysis may hinder the study’s reproducibility, making it challenging for other researchers to replicate the exact process and achieve identical results.

5. Simultaneous Concept Analysis

The Simultaneous Concept Analysis method consists of nine executive steps proposed by Haase et al. ( 2000 ), firmly rooted in Rodgers’ evolutionary perspective. The foundational principle of the Simultaneous Concept Analysis model lies in the recognition that numerous concepts have intricate interconnections, rendering isolated analysis impractical. However, these concepts can be effectively comprehended through comparative assessment, as their shared characteristics often warrant examination of closely related counterparts (Tavares et al., 2022 ).

The main goal of the Simultaneous Concept Analysis is not to establish a definitive and ultimate concept definition but to lay the groundwork for future exploration in the field of nursing. The analysis involves carefully examining each article to discover the attributes, antecedents, and outcomes associated with individual concepts (Haase et al., 2000 ; Tavares et al., 2022 ). This first analysis helps make a validity matrix. Thorough analysis ensures the method is systematic, verifiable, and replicable. Attributes, antecedents, and outcomes are gathered from relevant literature and subjected to comprehensive comparison within and across disciplines, thereby setting the stage for constructing a comparative validity matrix. Subsequently, the next step involves independently deriving the concept’s critical attributes, theoretical definitions, antecedents, and consequences (Tavares et al., 2022 ). The Simultaneous Concept Analysis comprises a series of nine stages (see Table 1 ).

6. Pragmatic Utility

Janice M. Morse initially developed the pragmatic utility concept analysis method as an alternative to Wilsonian and Rodgers’ methods. The pragmatic utility method examines the concept maturation level by scrutinizing its internal composition, utility, representational attributes, and interconnections with other concepts (Morse, 2000 ). Contrary to a linear progression, the pragmatic utility embodies a non-linear and iterative approach (Weaver & Mitcham, 2008 ). This method serves various purposes, including refining or elucidating concepts and examining the alignment between a concept’s definition and its operationalization (Zumstein & Riese, 2020 ).

The pragmatic utility aims to develop “partially mature” concepts using literature as data. Instead of synthesis, this meta-analytic approach examines how other researchers use the lay concept in their work. It uncovers definitions, attributes, and uses through systematic analysis, asking analytical questions about their conceptualizations and synthesizing data (Morse, 2016 ). This reveals implied/explicit assumptions, inferred meaning, and components. It identifies the lay concept’s commonalities, differences, perspectives, and operationalization degrees (Morse, 2016 ).

The pragmatic utility is not a literature summary or critique, nor a research synthesis or meta-analysis. It compares more than perspectives; it goes beyond creating new models and insights (Morse, 2016 ). Pragmatic utility stands apart from common literature summaries. It is also noted that this method emphasizes the ‘critical appraisal’ technique (Weaver & Mitcham, 2008 ), comparing attributes from different authors and revealing underlying assumptions and practical applications. Also, Morse et al. ( 1996 ) set a guideline, including the database’s extensiveness, analysis depth, argument logic, abstractness level, validity, and knowledge contribution, to assess rigor. Procedures of pragmatic utility include 1) clarifying the inquiry purpose, 2) pinpointing a partially mature lay concept, 3) determining concept maturity, 4) formulating key analytic questions, and 5) Synthesizing outcomes (Morse, 2016 ).

7. Principle-Based Concept Analysis

Penrod and Hupcey ( 2005 ) developed the Principle-Based Concept Analysis approach based on Morse et al. ( 1996 ) to define concepts based on principles exclusively within scientific use, disregarding creative interpretations found in art or fiction. The intentional and strategic extraction of data forms the foundation of this method. The approach acknowledges the dynamic and evolving nature of concept advancement over time, offering a robust framework for theoretically defining and understanding a concept’s state within the scientific community.

The analysis revolves around four broad principles: epistemological, pragmatic, linguistic, and logical (Penrod & Hupcey, 2005 ). The concept’s alignment with these principles determines its level of maturity and advancement. The epistemological principle is the study of how knowledge plays a role in revealing the scientific knowledge underpinning the concept (Waldon, 2018 ). The epistemological analysis focuses on the concept’s distinctiveness within the discipline’s knowledge base, indicating maturity through differentiation and clear positioning (Penrod & Hupcey, 2005 ). The pragmatic principle assesses a concept’s utility within the discipline and its operationalization, particularly in nursing (Penrod & Hupcey, 2005 ). The principle evaluates whether the concept’s applicability is supported by the literature and recognized by the discipline, profession, and society. Mature concepts are manifested in clinical practice (Penrod & Hupcey, 2005 ). The linguistic principle examines language and human speech, assessing a concept’s contextual flexibility and consistent meaning (Penrod & Hupcey, 2005 ; Waldon, 2018 ). The analysis includes various contexts, ensuring the concept’s relevance across different settings (Penrod & Hupcey, 2005 ). The logical principle involves a concept’s compatibility with related concepts and the clarity of its boundaries. Clearly defined conceptual boundaries prevent ambiguity when the concept is positioned alongside others in a theoretical framework (Penrod & Hupcey, 2005 ).

The outcome of Principle-Based Concept Analysis involves a comprehensive synthesis of the concept using scientific literature, along with identifying gaps and inconsistencies to drive concept development. Subsequently, the results are integrated into a theoretical definition, enhancing the concept’s understanding. In addition, Smith and Mörelius ( 2021 ) also combine Principle-Based Concept Analysis with a phased approach to enhance method clarity.

8. Semantic Concept Analysis

The semantic concept analysis, initially formulated by Koort ( 1975 ) and subsequently refined by Eriksson ( 2010 ), constitutes a prevalent approach in Nordic nursing science research aimed at enhancing comprehension of concepts or phenomena requiring clarification (Almerud Österberg et al., 2023 ). This method transcends a mere combination of words or letters, and it instead intimately intertwines with human existence and lived encounters (Almerud Österberg et al., 2023 ; Eriksson, 2010 ). This method includes an analysis of etymological, semantic, and discrimination (Honkavuo et al., 2018 ). Etymological analysis involves exploring a concept’s origin, transformation, and evolution using etymological dictionaries (Koort, 1975 ). Historical meanings may not persist in current language usage (Honkavuo et al., 2018 ; Koort, 1975 ). The semantic analysis uses dictionaries and synonyms to find linguistic consensus. It is about interpreting linguistic expressions, symbols, words, and terms, and if researchers agree on synonyms, the analysis concludes. If not, a discrimination analysis comes next, exploring closely related concepts to distinguish the concept in question. These related concepts form clusters based on qualitative differences in meanings and degrees of synonymy (Honkavuo et al., 2018 ; Koort, 1975 ).

The eight concept analysis methods discussed above provide various ways to systematically examine and understand complex concepts across different fields, especially in nursing. The first three methods—Walker and Avant’s concept analysis, Schwartz-Barcott and Kim’s hybrid model, and the Chinn and Kramer’s method—have evolved and expanded from Wilson’s foundational approach. Each brings unique contributions, adaptations, and modifications to the concept analysis process.

Rodgers’ cyclical model considers the dynamic nature of concepts, encouraging an iterative analysis and emphasizing the importance of considering the context and cultural factors. The Simultaneous Concept Analysis method incorporates principles from Rodgers’ approach and focuses on how concepts are interconnected. It also highlights the comparison of related concepts, offering a more complete perspective.

Like Rodger’s approach, the pragmatic utility concept analysis method uses a non-linear and iterative approach. It emphasizes the practical usefulness of concepts and how they align with guiding principles. It also strongly emphasizes critical appraisal, resulting in a rigorous evaluation. In addition, the Principle-Based Concept Analysis approach extends Morse’s approach aiming to align concepts with epistemological, pragmatic, linguistic, and logical principles. Lastly, the Semantic Concept Analysis method deeply explores a concept’s linguistic origins, synonyms, and distinctive features. It provides a comprehensive understanding of concepts within their linguistic context.

It is noteworthy that these methods are not mutually exclusive. This editorial aims to spur educators, researchers and students to adopt, adapt, and combine elements from different ways to create a customized approach that suits their research needs as well as to further discuss the concept analysis development. Ultimately, the chosen concept analysis method should align with the research objectives and be accountable conceptually, critically, and philosophically. Additionally, it should contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the concept under study.

Acknowledgment

Declaration of conflicting interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in this study.

Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed equally in this article.

Authors’ Biographies

Joko Gunawan, S.Kep.Ners, PhD is a Managing Editor of Belitung Nursing Journal and a Research Fellow at the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Yupin Aungsuroch, PhD, RN is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. She is also an Editor-in-Chief of Belitung Nursing Journal.

Colleen Marzilli, PhD, DNP, MBA, RN-BC, CCM, PHNA-BC, CNE, NEA-BC, FNAP is a Professor of Nursing at the University of Maine, School of Nursing, Orono, ME USA. She is also an Editorial Advisory Board Member of Belitung Nursing Journal.

Data Availability

Declaration of use of ai in scientific writing.

Nothing to declare.

- Almerud Österberg, S., Hörberg, U., Ozolins, L.-L., Werkander Harstäde, C., & Elmqvist, C. (2023). Exposed–a semantic concept analysis of its origin, meaning change over time and its relevance for caring science . International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being , 18 ( 1 ), 2163701. 10.1080/17482631.2022.2163701 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chinn, P. L., & Jacobs, M. K. (1987). Theory and nursing: A systematic approach (2nd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chinn, P. L., & Kramer, M. K. (1995). Theory and nursing: A systematic approach (4th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eriksson, K. (2010). Concept determination as part of the development of knowledge in caring science . Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences , 24 ( s1 ), 2-11. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00809.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghadirian, F., Salsali, M., & Cheraghi, M. A. (2014). Nursing professionalism: An evolutionary concept analysis . Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research , 19 ( 1 ), 1-10. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haase, J. E., Leidy, N. K., Coward, D. D., Britt, T., & Penn, P. E. (2000). Simultaneous concept analysis: A strategy for developing multiple interrelated concepts . In B. L. Rodgers (Ed.), Concept development in nursing: Foundations, techniques, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 209-229). Saunders. [ Google Scholar ]

- Honkavuo, L., Sivonen, K., Eriksson, K., & Nåden, D. (2018). A hermeneutic concept analysis of serving-a challenging concept for nursing administration . International Journal of Caring Sciences , 11 ( 3 ), 1377-1385. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hupcey, J. E., Morse, J. M., Lenz, E. R., & Tasón, M. C. (1996). Wilsonian methods of concept analysis: A critique . Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice , 10 ( 3 ), 185-210. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Koort, P. (1975). Semantisk analys: konfigurationsanalys: två hermeneutiska metoder [metoder [ Semantic Analysis and Configuration Analysis. Two Hermeneutical Methods ]. Lund: ILU/Studentlitteratur. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morse, J. M. (2000). Exploring pragmatic utility: Concept analysis by critically appraising the literature . In B. L. Rodgers & K. A. Knafl (Eds.), Concept development in nursing: Foundations, techniques, and applications (Vol. 2 , pp. 333-352). W.B. Saunders [ Google Scholar ]

- Morse, J. M. (2016). Concept clarification: The use of pragmatic utility . In J. M. Morse (Ed.), Analyzing and conceptualizing the theoretical foundations of nursing (pp. 267-280). Springer Publishing Company. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morse, J. M., Hupcey, J. E., & Cerdas, M. (1996). Criteria for concept evaluation . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 24 ( 2 ), 385-390. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.18022.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Penrod, J., & Hupcey, J. E. (2005). Enhancing methodological clarity: Principle-based concept analysis . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 50 ( 4 ), 403-409. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03405.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodgers, B. L. (1989). Concepts, analysis and the development of nursing knowledge: The evolutionary cycle . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 14 ( 4 ), 330-335. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03420.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz-Barcott, D. (2000). An expansion and elaboration of the hybrid model of concept development . In B. L. Rodgers & K. A. Knafl (Eds.), Concept development in nursing foundations, techniques, and applications (pp. 129-159). WB Saunders. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith, S., & Mörelius, E. (2021). Principle-based concept analysis methodology using a phased approach with quality criteria . International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 20 , 16094069211057995. 10.1177/16094069211057995 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tavares, A. P., Martins, H., Pinto, S., Caldeira, S., Pontífice Sousa, P., & Rodgers, B. (2022). Spiritual comfort, spiritual support, and spiritual care: A simultaneous concept analysis . Nursing Forum , 57 ( 6 ), 1559-1566. 10.1111/nuf.12845 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Waldon, M. (2018). Frailty in older people: A principle-based concept analysis . British Journal of Community Nursing , 23 ( 10 ), 482-494. 10.12968/bjcn.2018.23.10.482 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Walker, L. O., & Avant, K. C. (2014). Strategies for theory construction in nursing (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weaver, K., & Mitcham, C. (2008). Nursing concept analysis in North America: State of the art . Nursing Philosophy , 9 ( 3 ), 180-194. 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2008.00359.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson, J. (1973). Thinking with concepts . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zumstein, N., & Riese, F. (2020). Defining severe and persistent mental illness—a pragmatic utility concept analysis . Frontiers in Psychiatry , 11 , 648. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00648 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

NURS 700: Advanced Nursing Science

Concept analysis assignment.

- Scholarly Journal Articles

- Article Database Tutorials

- Books & Films

For your Concept Analysis assignment, you need to find specific types of scholarly sources. These can include books or peer-reviewed articles from scholarly journals. Remember, you can use a reference book such as an encyclopedia, thesaurus or dictionary, but you are limited to only one of each.

Please see the D2L page for your class for assignment instructions and the Walker and Avant book chapter. It is very important that you read both carefully.

Selection of appropriate search terms is very appropriate. We recommend connecting the term for your concept with any of these search terms using the Boolean operator AND. Also, truncate words using the * symbol to search for variant word endings. Here are some helpful search strategies to try:

- compassion AND "concept analysis"

- compassion AND philosoph*

- compassion AND theor*

- compassion AND defin*

- compassion AND concept*

- compassion AND (religious OR religion* OR theolog*)

- compassion AND anthropolog*

- compassion AND theor* AND psycholog*

It is often useful to use the advanced search screens in the article databases. Please also see the videos below for more search tips.

For a complete list of article databases available through the library, click on Search for Articles - Library Databases on the homepage of the library website ( www.metrostate.edu/library) or go to the A-Z Listing of Guides .

- Sample Concept Analysis Paper

Click on the PDF icon below to download a sample concept analysis paper written by a student for a previous term (shared with the consent of the student).

Please note the comments from the instructor.

Sample Database Searches

Here are some videos of sample searches in some commonly used databases. Note: You will need headphones or speakers in order to hear the audio.

Academic Search Premier

Tutorial: Peer Review in Five Minutes

The Peer Review In Five Minutes video was created by North Carolina State University Libraries , and is licensed for free, noncommercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution - Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License .

Boolean Operators Tutorial

Learn to use the Boolean operators AND, OR and NOT to retrieve more items on your topic and to search more precisely.

Searching Effectively Using AND, OR, NOT

Tutorial produced by the Colorado State University Libraries. Used with permission.

Reference Desk: (651) 793-1614 General information: (651) 793-1616 Email: [email protected]

- Next: Scholarly Journal Articles >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 4:02 PM

- URL: https://libguides.metrostate.edu/nurs700

A Guide to Conceptual Analysis Research

Understand how to conduct a more accurate and detailed conceptual analysis research to convert it into a more concrete concept.

There are countless researches, theories, studies and concepts on countless subjects. This is the result of years of collecting data and turning it into informative text.

There are times when it is necessary to investigate existing theories and concepts in order to gain a better understanding or to bring out more nuances. When it comes to concepts, the best way to approach them is through a conceptual analysis research , which will provide and clarify all possible information, coherent or not, that surrounds this specific concept.

This article will walk you through how to conduct a more accurate and detailed conceptual analysis research to convert an abstract and ambiguous idea into a more concrete concept.

What is conceptual analysis, and how does it work?

Conceptual Analysis Research can be defined as the examination of a concept into simpler elements to promote clarification while having a consistent understanding; analysis can include distinguishing, analyzing, and representing the various aspects to which the concept refers.

The ultimate goal in general is to improve the conceptual clarity and coherence of careful clarifications and definitions of meaning. Or, on occasion, to expose practical inconsistency.

Preparing a conceptual analysis entails conducting a literature review, identifying the key characteristics or attributes of the concept, identifying its antecedents and consequences, and possibly applying them to a model case.

How to write a conceptual analysis?

Choose a Concept to Study

First and foremost, determine the concept that will guide the research. Examine specific and interesting areas, then select a field of study for the research, which should be based on a theoretical framework.

And remember, the conceptual analysis is supposed to bring clarity and coherence; the subject chosen must allow this. Avoid subjects that do not allow further clarification, do not have enough data, or are not ambiguous enough to warrant in-depth analysis.

Conduct a Literature Review

An initial review of the literature on the chosen concept can provide countless insights into the concept and hence the researcher can find out whatever is known, not known, or confusing about a concept.

Conduct a review of the literature on your chosen concept from a wide range of disciplines. Instead of focusing solely on the chosen field of study, search for nuances in other disciplines and potential collaborations.

Let’s say the chosen field is medicine, for example, look for psychological, sociological, interpersonal, and any other possible aspects of it. While conducting the literature review, begin by identifying surrogate terms, relevant uses, and inconsistencies in the concept.

Select an Appropriate Sample to Collect Data

There will be a large amount of data to understand and use after conducting a thorough literature review. This step is inestimable since it is so important to be critical during this stage of the process to select the best and more assertive data to analyze and include in the analysis.

It might be useful to inquire whether the authors are “describing the concept the same,” “similarly using the concept,” or “were any inconsistencies available in literature?”.

Identify Characteristics

Determine the key characteristics or features of your concept. The characteristics of a concept are what makes it true. Assume the concept is a pregnancy, and the fetus’s heartbeat is what makes the pregnancy real, therefore this is the main characteristic of the concept.

Making good use of the concept’s characteristics will result in the operationalization of the concept, which will lead to the selection of a measurement tool.

Assess the Concept Antecedents and Consequences

By definition, antecedents are what initiated the concept, what led to it. While consequences are the results and outcomes, what follows the concept.

This is an important step in dissecting the concept and understanding all of its nuances. This step gives the researchers an idea of how tangible the concept is.

Identify Concepts Related to the Concept of Interest

After defining the concept’s characteristics, antecedents and consequences, it is time to determine whether any related concepts in the literature require clarification.

Again, a critical review of the literature will reveal to the researcher what relevant research has been conducted, any conceptual ambiguity, and the implications for future research.

Construct Cases for Analysis

When doing conceptual analysis research , enrich your analysis by adding cases into the research, which will provide the research with a more concrete understanding of the concept and will aid in the clarification of the research’s direction.

Include a model case, a contrary case, a related case, and a borderline case in the analysis. A model case has all of the concept’s key characteristics, all or most of the defining criteria, and at least one of the antecedents and consequences.

A contrary case possesses none of the defining characteristics, while a related case possesses a similar defining characteristic, and a borderline case may be a metaphorical application of the concept.

Understanding the uses of conceptual analysis in research

Before deciding to do a conceptual analysis research, it is critical to consider both the advantages and disadvantages of conducting it.

Advantages of Conceptual Analysis

- Refining and validating a possibly confusing concept.

- Provides valuable historical and cultural insights over time.

- Clarify any ambiguous concepts that could be used as synonyms

- Possibly developing instruments for better measurement of the concept’s data.

Disadvantages of Conceptual Analysis

- Conceptual analysis can not create a new concept, only validate existing ones.

- It’s a difficult process that requires a long time and persistence to investigate and validate a concept.

- Dealing with such a large amount of data can be uncertain and overwhelming for the researcher.

- More prone to error, especially when a relational analysis is used to achieve a higher level of interpretation.

Your figures ready within minutes with Mind the Graph

Mind The Graph is an easy professional tool specialized in creating figures and graphs. Begin easily creating amazing scientific infographics with infographics templates and without any complications.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

About Fabricio Pamplona

Fabricio Pamplona is the founder of Mind the Graph - a tool used by over 400K users in 60 countries. He has a Ph.D. and solid scientific background in Psychopharmacology and experience as a Guest Researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry (Germany) and Researcher in D'Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR, Brazil). Fabricio holds over 2500 citations in Google Scholar. He has 10 years of experience in small innovative businesses, with relevant experience in product design and innovation management. Connect with him on LinkedIn - Fabricio Pamplona .

Content tags

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top