Insult or Honor?

- Student sensitivity.

Print this Text

Select the Student Version to print the text and Text Dependent Questions only. Select the Teacher Version to print the text with labels, Text Dependent Questions and answers. Highlighted vocabulary will appear in both printed versions.

- Google Classroom

Sign in to save these resources.

Login or create an account to save resources to your bookmark collection.

Get the Learning for Justice Newsletter

Module 11: Cotton Is King — The Antebellum South (1800-1860)

Southern culture of honor, learning objectives.

- Describe the Southern culture of honor

Honor in the South

Figure 1 . “The Modern Tribunal and Arbiter of Men’s Differences,” an illustration that appeared on the cover of The Mascot, a newspaper published in nineteenth-century New Orleans, reveals the importance of dueling in southern culture; it shows men bowing before an altar on which are laid a pistol and knife.

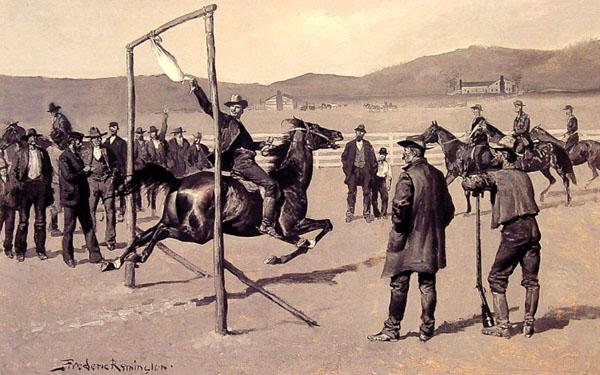

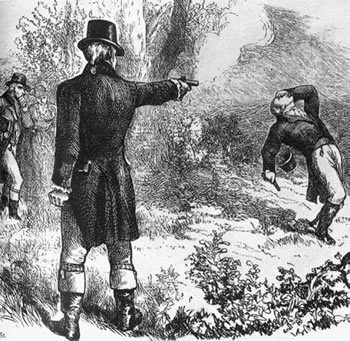

A complicated code of honor among privileged White southerners, dictating the beliefs and behavior of “gentlemen” and “ladies,” developed in the antebellum years. Maintaining appearances and reputation was supremely important. It can be argued that, as in many societies, the concept of honor in the antebellum South had much to do with control over dependents, whether enslaved people, wives, or relatives. Defending their honor and ensuring that they received proper respect became preoccupations of White people in the slave states of the South. To question another man’s assertions was to call his honor and reputation into question. Insults in the form of words or behavior, such as calling someone a coward, could trigger a rupture that might well end on the dueling ground. Dueling had largely disappeared in the antebellum North by the early nineteenth century, but it remained an important part of the southern code of honor through the Civil War years. Southern White men, especially those of high social status, settled their differences with duels, before which antagonists usually attempted reconciliation, often through the exchange of letters addressing the alleged insult. If the challenger was not satisfied by the exchange, a duel would often result.

The formal duel exemplified the code in action. If two men could not settle a dispute through the arbitration of their friends, they would exchange pistol shots to prove their equal honor status. Duelists arranged a secluded meeting, chose from a set of deadly weapons, and risked their lives as they clashed with swords or fired pistols at one another. Some of the most illustrious men in American history participated in a duel at some point during their lives, including President Andrew Jackson, Vice President Aaron Burr, and U.S. senators Henry Clay and Thomas Hart Benton. In all but Burr’s case, dueling helped elevate these men to prominence.

Violence among the lower classes, especially those in the backcountry, involved fistfights and shoot-outs. Tactics included the sharpening of fingernails and filing of teeth into razor-sharp points, which would be used to gouge eyes and bite off ears and noses. In a duel, a gentleman achieved recognition by risking his life rather than killing his opponent, whereas those involved in rough-and-tumble fighting achieved victory through maiming their opponent.

The legal system was partially to blame for the prevalence of violence in the Old South. Although states and territories had laws against murder, rape, and various other forms of violence, including specific laws against dueling, upper-class southerners were rarely prosecuted, and juries often acquitted the accused. Despite the fact that hundreds of duelists fought and killed one another, there is little evidence that many duelists faced prosecution, and only one, Timothy Bennett (of Belleville, Illinois), was ever executed. By contrast, prosecutors routinely sought cases against lower-class southerners, who were found guilty in greater numbers than their wealthier counterparts.

The dispute between South Carolina’s James Hammond and his erstwhile friend (and brother-in-law) Wade Hampton II illustrates the southern culture of honor and the place of the duel in that culture. A strong friendship bound Hammond and Hampton together. Both stood at the top of South Carolina’s society as successful, married plantation owners involved in state politics. Prior to his election as governor of the state in 1842, Hammond became sexually involved with each of Hampton’s four teenage daughters, who were his nieces by marriage. “[A]ll of them rushing on every occasion into my arms,” Hammond confided in his private diary, “covering me with kisses, lolling on my lap, pressing their bodies almost into mine . . . and permitting my hands to stray unchecked.” Hampton found out about these dalliances, and in keeping with the code of honor, could have demanded a duel with Hammond. However, Hampton instead tried to use the liaisons to destroy his former friend politically. This effort proved disastrous for Hampton, because it represented a violation of the southern code of honor. “As matters now stand,” Hammond wrote, “he [Hampton] is a convicted dastard who, not having nerve to redress his own wrongs, put forward bullies to do it for him. . . . To challenge me [to a duel] would be to throw himself upon my mercy for he knows I am not bound to meet him [for a duel].” Because Hampton’s behavior marked him as a man who lacked honor, Hammond was no longer bound to meet Hampton in a duel even if Hampton were to demand one. Hammond’s reputation, though tarnished, remained high in the esteem of South Carolinians, and the governor went on to serve as a U.S. senator from 1857 to 1860. As for the four Hampton daughters, they never married; their names were disgraced, not only by the whispered-about scandal but by their father’s actions in response to it; and no man of honor in South Carolina would stoop so low as to marry them.

Gender and the Southern Household

The antebellum South was an especially male-dominated society. Far more than in the North, southern men, particularly wealthy planters, were patriarchs and sovereigns of their own household. Among the White members of the household, labor and daily ritual conformed to rigid gender delineations. Men represented their household in the larger world of politics, business, and war. Within the family, the patriarchal male was the ultimate authority. White women were relegated to the household and lived under the thumb and protection of the male patriarch. The ideal southern lady conformed to her prescribed gender role, a role that was largely domestic and subservient. While responsibilities and experiences varied across different social tiers, women’s subordinate state in relation to the male patriarch remained the same.

Femininity in the South was intimately tied to the domestic sphere, even more so than for women in the North. The cult of domesticity strictly limited the ability of wealthy southern women to engage in public life. While northern women began to organize reform societies, southern women remained bound to the home, where they were instructed to cultivate their families’ religious sensibility and manage their household. Managing the household was not easy work, however. For women on large plantations, managing the household would include directing a large bureaucracy of potentially rebellious enslaved people. For most southern women who did not live on plantations, managing the household included nearly constant work in keeping families clean, fed, and well-behaved. On top of these duties, many southern women were required to help with agricultural tasks.

Figure 2 . This cover illustration from Harper’s Weekly in 1861 shows the ideal of southern womanhood.

Female labor was an important aspect of the southern economy, but the social position of women in southern culture was understood not through economic labor but rather through moral virtue. While men fought to get ahead in the turbulent world of the cotton boom, women were instructed to offer a calming, moralizing influence on husbands and children. The home was to be a place of quiet respite and spiritual solace. Under the guidance of a virtuous woman, the southern home would foster the values required for economic success and cultural refinement. Female virtue came to be understood largely as a euphemism for sexual purity, and southern culture, southern law, and southern violence largely centered on protecting that virtue of sexual purity from any possible imagined threat. In a world saturated with the sexual exploitation of Black women, southerners developed a paranoid obsession with protecting the sexual purity of White women. Black men were presented as an insatiable sexual threat. Racial systems of violence and domination were wielded with crushing intensity for generations, all in the name of keeping White womanhood as pure as the cotton that anchored southern society.

Writers in the antebellum period were fond of celebrating the image of the ideal southern woman. One such writer, Thomas Roderick Dew, president of Virginia’s College of William and Mary in the mid-nineteenth century, wrote approvingly of the virtue of southern women, a virtue he concluded derived from their natural weakness, piety, grace, and modesty. In his Dissertation on the Characteristic Differences Between the Sexes , he writes that southern women derive their power not by leading armies to combat, or of enabling her to bring into more formidable action the physical power which nature has conferred on her. No! It is but the better to perfect all those feminine graces, all those fascinating attributes, which render her the center of attraction, and which delight and charm all those who breathe the atmosphere in which she moves; and, in the language of Mr. Burke, would make ten thousand swords leap from their scabbards to avenge the insult that might be offered to her. By her very meekness and beauty does she subdue all around her.

Such popular idealizations of elite southern White women, however, are difficult to reconcile with their lived experience: in their own words, these women frequently described the trauma of childbirth, the loss of children, and the loneliness of the plantation.

Louisa Cheves McCord’s “Woman’s Progress”

Louisa Cheves McCord was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1810. A child of some privilege in the South, she received an excellent education and became a prolific writer. As the excerpt from her poem “Woman’s Progress” indicates, some southern women also contributed to the idealization of southern White womanhood.

Sweet Sister! stoop not thou to be a man! Man has his place as woman hers; and she As made to comfort, minister and help; Moulded for gentler duties, ill fulfils His jarring destinies. Her mission is To labour and to pray; to help, to heal, To soothe, to bear; patient, with smiles, to suffer; And with self-abnegation noble lose Her private interest in the dearer weal Of those she loves and lives for. Call not this— (The all-fulfilling of her destiny; She the world’s soothing mother)—call it not, With scorn and mocking sneer, a drudgery. The ribald tongue profanes Heaven’s holiest things, But holy still they are. The lowliest tasks Are sanctified in nobly acting them. Christ washed the apostles’ feet, not thus cast shame Upon the God-like in him. Woman lives Man’s constant prophet. If her life be true And based upon the instincts of her being, She is a living sermon of that truth Which ever through her gentle actions speaks, That life is given to labour and to love.—Louisa Susanna Cheves McCord, “Woman’s Progress,” 1853

What womanly virtues does Louisa Cheves McCord emphasize? How might her social status, as an educated southern woman of great privilege, influence her understanding of gender relations in the South?

For enslaver Whites, the male-dominated household operated to protect gendered divisions and prevalent gender norms; for enslaved women, however, the same system exposed them to brutality and frequent sexual domination. The demands on the labor of enslaved women made it impossible for them to perform the role of domestic caretaker that was so idealized by southern men. That enslavers put them out into the fields, where they frequently performed work traditionally thought of as male, reflected little the ideal image of gentleness and delicacy reserved for White women. Nor did the enslaved woman’s role as daughter, wife, or mother garner any patriarchal protection. Each of these roles and the relationships they defined was subject to the prerogative of a master, who could freely violate enslaved women’s persons, sell off their children, or separate them from their families.

- US History. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/12-3-wealth-and-culture-in-the-south . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Religion and Honor in the Slave South. Provided by : The American Yawp. Located at : http://www.americanyawp.com/text/11-the-cotton-revolution/#footnote_14_84 . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Accessories

- Facial Hair

Browse all Get Style

- Program Review

Browse all Get Strong

- Relationships

- Social Skills

Browse all Get Social

- Manly Know-How

- Outdoor/Survival

Browse all Get Skilled

in: Behavior , Character , Featured

Brett & Kate McKay • November 26, 2012 • Last updated: October 7, 2023

Manly Honor Part V: Honor in the American South

This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction free ebook to read offline at your leisure. Click here to buy.

Welcome back to our series on manly honor. Today we tackle Southern honor in the 19 th century. Now, be prepared: this is and will be the longest post in the series by far. The complexity of traditional honor and its various cultural manifestations cannot possibly be underestimated, nor can the difficulty in distilling these complexities into an accessible, coherent narrative. We have done our best with that task so far, and here as well; however, understanding Southern honor requires a more in-depth exploration. We could have just sketched out the very basics, but truly grasping those basics necessitates an understanding of the framework which underlies them. Also, as we shall see, because the South’s culture of honor still influences that region today, it’s a good subject to become knowledgeable about if you want to understand the country. Plus, it’s just really interesting!

We didn’t set out to do it, but I’m proud of the fact that this series has turned into a resource unlike any other that is out there. I don’t imagine there’s a huge audience among blog readers for 7,000-word posts about Southern honor, but those who are interested in the subject will hopefully really dig it, and anyone who girds up his loins and reads the whole thing will be rewarded.

Southern Honor: An Introduction

In our last post about the history of honor, we took a look at how honor manifested itself in the American North around the time of the Civil War. Yet when most folks think about honor in the States, both then and now, what first comes to mind is invariably the South .

There’s a reason for that. While honor in the North evolved during the 19 th century away from the ideals of primal honor and towards a private, personal quality synonymous with “integrity,” the South held onto the tenets of traditional honor for a much longer period of time.

Unlike the Northern code of honor, which emphasized emotional restraint, moral piety, and economic success, the Southern honor code in many ways paralleled the medieval honor code of Europe — combining the reflexive, violent honor of primitive man with the public virtue and chivalry of knights.

The code of honor for Southern men required having: 1) a reputation for honesty and integrity, 2) a reputation for martial courage and strength, 3) self-sufficiency and “mastery,” defined as patriarchal dominion over a household of dependents (wife/children/slaves), and 4) a willingness to use violence to defend any perceived slight to his reputation as a man of integrity, strength, and courage, as well as any threats to his independence and kin. Just as in medieval times, “might made right” in the American South. If a man could physically dominate or kill someone who accused him of dishonesty, that man maintained his reputation as a man of integrity (even if the accusations were in fact true).

Anthropologists and social psychologists believe this form of classical honor survived and thrived in the American South and died in the North because of cultural differences between their respective early settlers, as well as the North’s and South’s divergent economies.

Herding, the Scotch-Iris h, and the South’s Culture of Honor

To understand why a more primal and violent culture of honor took root in the American South, it helps to understand the cultural background of its early settlers. While the northern United States was settled primarily by farmers from more established European countries like the Netherlands, Germany, and especially England (particularly from areas around London), the southern United States was settled primarily by herdsmen from the more rural and undomesticated parts of the British Isles. These two occupations — farming and herding — produced cultures with starkly different notions of honor.

Some researchers argue that herding societies tend to produce cultures of honor that emphasize courage, strength, and violence. Unlike crops, animal herds are much more vulnerable to theft. A herdsman could lose his entire fortune in one overnight raid. Consequently, martial valor and strength and the willingness to use violence to protect his herd became useful assets to an ancient herdsman. What’s more, a reputation for these martial attributes served as a deterrent to would-be thieves. It’s telling that many of history’s most ferocious warrior societies had pastoral economies. The ancient Hittites, the ancient Hebrews, and the ancient Celts are just a few examples of these warrior/herder societies.

As it happened, the Scotch-Irish settlers that poured into the Southern colonies from the late 17 th century through the antebellum period were genetic and cultural descendants of the war-like and pastoral Celts. Hailing from Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Cornwall, and the English Uplands, these Scotch-Irish peoples made up perhaps half of the South’s population by 1860 (in contrast, three-quarters of New Englanders, up until the massive influx of Irish immigrants in the 1840s, were English in origin). As the Celtic-herdsmen theory goes (and it is not without its critics), their influence on Southern culture was even larger than their numbers. These rough and scrappy Scotch-Irish immigrants not only brought with them their ancestors’ penchant for herding, but also imported their love of whiskey, music, leisure, gambling, hunting, and…their warrior-bred, primal code of honor. Even as the South became an agricultural powerhouse, the vast majority of white Southerners – from big plantation owners to the landless — continued to raise hogs and livestock. Whether a man spent most his time working a farm or herding his animals, the pastoral culture of honor, with its emphasis on courage, strength, and violence — characterized by an aggressive stance towards the world and a wariness towards outsiders who might want to take what was his — remained (and as we will see later, continues even to this day).

Agrarian Economics

While the South’s ethno-cultural background may explain the origin of its primal and sometimes violent code of honor, it doesn’t explain why it remained so entrenched in Southern life for so long while contemporaneous Northerners were quick to adopt the more modern, private notion of honor. To answer that question we simply need to look to the divergent economies of the two regions.

While industrialization transformed the Northern landscape in the 19 th century and sparked the rise of urbanization, the antebellum South remained largely agrarian and rural. This created two important effects in the region: economic opportunities were fewer in number and less diverse, and kinship ties remained very strong.

Land Ownership and Class

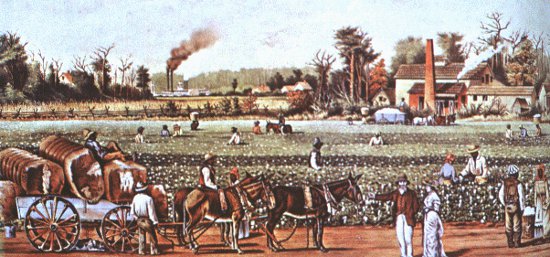

While for many, slavery is the first thing that comes to mind when they think of the Old South, only 25% of the white population owned slaves, and 73% of those who did held fewer than ten. In other words, three-quarters of the white population were nonslaveholders. While it is common to imagine there were only two white classes in the South — rich, slave-holding planters and poor whites — there was actually a middle-class majority of non-slaveholders (around 60-70%) who owned their own land. All told, about 75% of all white males in the South owned land. Another number were professionals and artisans, and the remaining percentage were “poor white trash” (yes, this derogatory term originated way back in the 19 th century). Alternately referred to as “squatters,” “crackers,” “clay/dirt-eaters,” and “sand-hillers,” these poor whites eked out a subsistence living in isolated settlements nestled in the hills and mountains, planting perhaps a few crops and raising a few animals, but mainly getting by through hunting and fishing.

The richest planters might own thousands of acres and hundreds of slaves, while a yeoman farmer worked a hundred acres and held no slaves; 90-95% of all agricultural wealth in the South was in the hands of slaveholders by 1860. Despite this deep inequality, the culture of the South was quite different than the walled-off oligarchy of the Old World nobility. Whereas Europe’s landed aristocracy held a monopoly on power and claimed honor as exclusively their own, because of the accessibility of land in the South – even if men’s holdings vastly differed – a common bond between the two groups existed.

Yeoman farmers typically lived close to plantation owners, and the two groups frequently intermingled through both trade and kinship. While entering the upper echelon of Southern gentlemen depended partly on family lineage, there was a degree of social and economic mobility; non-landowners acquired land, non-slave owners acquired slaves, and non-planters married into planter families. Yet, most yeoman farmers sought not great wealth, but being a “good-liver” — attaining a simple, comfortable self-sufficiency surrounded by one’s family and enough land to pass onto one’s sons. Striving to get ahead was too much work ; while industry was perhaps the sine qua non of honorable virtues both in Victorian England and the American North, Southerners valued leisure in their lives. In this they harkened back to their Celtic forbearers, who had employed the least labor-intensive method of herding — the open range system – and used the rest of their time for feasting, fighting, and merriment.

This satisfaction with self-sufficiency was rooted in both cultural ideals and practical considerations. While industrialization in the North had opened up a new stratum of diverse professions, options in the South outside of agriculture were far fewer; the only other honorable professions were law, medicine, clergy, and the military, but even then, many men hoped these positions would simply serve as stepping-stones towards becoming a planter. And while Northern men were celebrated for having the pluck and initiative to leave home in pursuit of personal goals, Southerners wished to stay close to hearth and home, and some saw such pecuniary striving as crass. Again, this viewpoint derived from both cultural and utilitarian considerations; the ability to move into professions and politics in the South relied less on the egalitarian boot-strapping that defined the North, and more on personal and familial connections.

Honor in the South

The differences between the industrialized North and agrarian South led to differences in their honor codes. While the North equated honor with economic success, and economic success with moral character, honor in the South hinged on hitting a more basic threshold.

The Southern ideal, in theory, if not always in practice, was that the rich man was no better than the poor man; all whites of all classes considered themselves part of the same honor group. As all traditional honor groups are, it was a classless hierarchy not of wealth, but of rank. The military makes a good comparison. All soldiers are equals as men of honor, but there are higher and lower ranks; each strata has greater or lesser responsibilities and privileges, and its own culture.

Every white man acknowledged the personal equality of every other – horizontal honor – while also acknowledging that some, because of blood and talent – had risen higher than others and achieved greater vertical honor . Most who occupied a position below the top respected that setup as proper and natural; differences in status did not hold moral significance. Southerners also did not see hierarchy as incompatible with democracy, but rather as a necessary way of bringing order to what would otherwise be a society dominated by chaos and mob rule.

While the poorest whites were seen as dishonorable and despicable because they did not contribute anything to society, and just as importantly, chose to live in isolation from the “tribe,” such a label was only possible for those who could perhaps be members of the honor group, but failed to meet the code. While some Northern gentlemen did not even acknowledge the common manhood of “the roughs” because of their failure to meet any of the requirements of the Stoic-Christian honor code , poor whites in the South had the potential to be included because basic Southern honor was not dependent on gentility (clothes/education/manners), but things that were accessible to every man. While poor whites weren’t generally concerned about the integrity part of the Southern honor code as much as the farmers and planters were, all were united in honoring independence (not working for another man and being master of one’s own “little commonwealth”), strength and personal valor, and a man’s willingness to use violence to defend his reputation. Men from every rank in the South believed that honor required a man to take an aggressive stance to the world – a constant readiness to fight for what was his against the encroachments of outsiders and the insults of scalawags of all varieties.

What About Slavery?

When discussing the differences between North and South in the 19 th century, obviously the huge elephant in the room is slavery. Slavery definitely affected the honor code inasmuch as it shaped the South’s economy and was part of the way of life whites wished to defend. It influenced it in other ways as well, but historians disagree on exactly how. Some think the fear of a slave uprising made Southerners more prone to engaging in reflexive violence – demonstrating strength as a warning against would-be mutineers. Some say that by including all whites in the Southern honor group, rich and poor alike, they pacified possible resentment from the lower class, and thus headed off the possibility of their teaming up with slaves in a rebellion against rich plantation owners. Slavery helped solidify the Southern hierarchy, and traditional honor thrives in an environment of “us vs. them.”

It’s obviously a complex subject, which sits outside the purview of this article. Since an honor group can only consist of those who consider themselves equals, for Southern whites, blacks were obviously excluded. Thus, honor for whites in the South was something generally only judged, jockeyed for, and mediated amongst each other (with the exception of black on white crime, in which a white man’s honor necessitated his meting out justice himself, sometimes in the form of a lynch mob.)

As with the North, we know that just because one group claims exclusive right to honor, doesn’t mean those left out don’t have their own code ( i.e., the gentlemen and the roughs ). Slaves assuredly had their own code of honor too, but unfortunately no one has tackled that subject yet that I know of. A Ph.D. dissertation waiting to be written…

The Public Nature of Southern Honor

That a man’s public reputation remained the basis of his honor, as opposed to shifting towards private conscience as in the North, was due to the close communities and kinship ties in the South. In the North, waves of immigration, coupled with urbanization, created a diverse society dominated by impersonal relations, making agreement on a single honor code difficult, and sparking the development of personal codes of honor. The South, on the other hand, remained agrarian and sparsely populated; at the start of the Civil War, the North had 10+ million more residents.

Southerners preferred to live physically close to their relatives, and the foundation of every community was one’s extended family. One of the interesting signifiers of the way Southerners were more tied to tradition and familial interests versus Northerners can be found in the diverging naming practices of the two regions. For example, at the beginning of the 1800s, only 10% of boys in a typical Massachusetts community were given non-familial names, but that jumped up to 30% by the time of the Civil War. In contrast, Bertram Wyatt-Brown reports that as late as 1940, a rural sociologist in Kentucky “discovered that only 5% of all males had names not affiliated with traditional family first and middle names. Over 70 percent of the men were named for their fathers.” Giving sons familial names symbolized the patriarch’s important position in Southern families, tied grandparents and grandchildren together, and imparted to sons a sense of pride and place in a long lineage – a lineage he was charged with honorably upholding.

As a result of the close-knit, more homogenized nature of Southern society, two fundamental requirements of traditional honor remained in place : a cohesive honor code that everyone in the group understood and ascribed to, and frequent face-to-face interactions that allowed members to judge each other’s reputations. This also left in place traditional honor’s mechanism for dealing with social deviants: public shame and group justice.

Honor acted in tandem with the formal legal system in the South. For Southern men, some matters of honor could not possibly be justly settled in a court of law; the matter had to be resolved mano-a-mano, sometimes in the form of a duel. On her deathbed, Andrew Jackson’s mother (Scotch-Irish herself, and an immigrant to the Carolinas) told him: “Avoid quarrels as long as you can without yielding to imposition. But sustain your manhood always. Never bring a suit in law for assault and battery or for defamation. The law affords no remedy for such outrages that can satisfy the feelings of a true man.” Jackson took his mother’s advice to heart, participating in at least 13 “affairs of honor.”

Crimes and disputes that did end up in court were discussed in the taverns and parlors about town, and judges were swayed by the public’s opinion of the crime and of the accused when rendering their sentences. Southerners wanted it this way; impersonal justice seemed too Northern — a justice system which incorporated local circumstances preserved local autonomy.

When the community felt that justice, according to the dictates of honor, had not been served by the court, they believed it within their rights to step in and mete out the proper punishment themselves. This often took the form of lynch mobs, which frequently went after blacks, but sometimes fellow whites as well. Whites in need of shaming were more likely to be on the receiving end of a “charivari”, which was an ancient ritual that dates back at least to the Middle Ages in which the townspeople would gather outside the home of one who had violated the community’s norms – perhaps through adultery or wife-beating – and beat on pots and pans, hoot and holler, and sometimes give the accused a tar and feathering. The duly shamed would quickly get the message and high-tail it out of town.

For Southerners, these extra-legal forms of justice were not a substitute for the court system, but a supplement; as Wyatt-Brown puts it: “Common law and lynch law were ethically compatible. The first enabled the legal profession to present traditional order, and the second conferred upon ordinary men the prerogative of ensuring that community values held ultimate sovereignty.”

Yet it was the threat of simple, informal shunning — being made an outcast — that was enough to get most Southerners to conform to the code. As in all traditional honor societies, a Southerner’s relations with others and their inclusion in the community were the heart of life; one could not separate their personal identity and happiness from their membership in the group. What Moses I. Finley said of the world of Odysseus was true of the South as well: “one’s kin were indistinguishable from oneself.” Thus to be abandoned was the worst possible fate. Thomas Carlyle, a Scottish writer who was popular in the American South, described this tribal mindset well:

“Isolation is the sum-total of wretchedness to man. To be cut off, to be left solitary: to have a world alien, not your world, all a hostile camp for you; not a home at all, of hearts and faces who are yours, whose you are! … To have neither superior, nor inferior, nor equal, united manlike to you. Without father, without child, without brother. Man knows no sadder destiny.”

These strong bonds with kin, along with their deep connection to the land, created an honor culture extraordinarily rooted in people and place.

The Three Pillars of Southern Honor Culture

While it is true, as Wyatt-Brown asserts, that “honor in the Old South applied to all white classes,” it was still lived with “manifestations appropriate to each ranking.” If you remember our military analogy above, it can be compared to the way officers and privates are equals as men of honor, but each group has its own culture and way of interacting with each other.

For example, the code of honor of the upper middle class and the wealthy was tempered by gentility. Their aggressive stance to the world was refined and balanced by an emphasis on moral, dignified uprightness, clothes and manners, and education. The latter was typically devoted to classical literature from ancient Greece and Rome; The Illiad and The Odyssey were instruction manuals on living a life of honor, and Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations was considered second only to the Bible in importance.

There were, however, three pillars of Southern honor culture that transcended socio-economic status, even if they sometimes manifested themselves differently according to class. For all white Southern men, these three pillars were public, ritual encounters which served to test a man’s honor, and Wyatt-Brown argues, “helped Southerners determine community standing and reaffirm their membership in the immediate circle to which they belonged. In all of them honor and pursuit of place muted the threat of being alone and provided the chance to enjoy the power in fellowship.”

1. Sociability and Hospitality

Generosity, friendliness, warm-heartedness, and expressive sociability were points of honor for a Southerner and one of the primary ways in which he “distinguish[ed] himself from the Yankee.” If the watchwords for the Northerner gentleman were “coolness and detachment,” the watchwords for his Southern counterpart were “passion and affability.” While Southern men honored the Stoics for their apathy towards death and centered calmness in times of both crisis and fortune, they made more allowance for joviality in social situations than their more restrained Northern brethren. Even today, Southerners take pride in their region’s friendly and big-hearted ways.

To combat the fear of solitariness discussed above, Southerners looked for any excuse to get together with friends and kin and held frequent dances, corn huskings, barn raisings, picnics, and militia musterings, amongst many other types of gatherings.

But it was the ancient ritual of hospitality that held the most central role in a Southern man’s sociability and acted as a test of his honor. Wyatt-Brown defines hospitality as “the relationship of an individual and family to outsiders on home turf.” But it started with taking care of one’s own kin. Southerners contrasted their generous approach in aiding their relatives to that which they perceived as the impersonal and tightfisted way in which Northerners more frequently relied on public assistance – leaving the job to asylums, poorhouses, and charitable organizations.

And of course when it came to strangers and visitors, Southerners felt duty-bound to show hospitality to whomever showed up. An element of competition existed in Southern hospitality – households which pulled out more of the stops in entertaining won status in the eyes of the community.

The honor-bound obligation to show hospitality to everyone who appeared on your doorstep could lead to financial distress. When Jefferson returned to Monticello after serving in the White House, even folks who had simply voted for him felt entitled to swing by and say hello; having to entertain this constant stream of well-wishers contributed to the large debt with which the president died.

2. Gambling and Drinking

While Southerners were a religious people – often Baptist or Methodist in their faith – the Second Great Awakening that swept the Northeast did not have as transforming an effect in Dixie. In the North, a revival in evangelical Christianity led to an emphasis on seeking moral perfection – both individually and as a community. This desire for purification sparked the creation of reformation groups, such as temperance societies, and led some gentlemen to believe that abstinence from things like alcohol and gambling were requirements of a man’s code of honor.

While such things fell out of favor with Northerners (and some Southerners as well) most Southern men continued to heartily believe that drinking and gambling (what one contemporary referred to as a “generous and manly vice”) were not incompatible with their faith or morality, and greatly contributed to maintaining a social, honorable culture. Their piety on Sundays with their families and the rowdy good fun they had with each other could be compartmentalized, like two different roles in their life. As has famously been said, “The South votes dry, and drinks wet.”

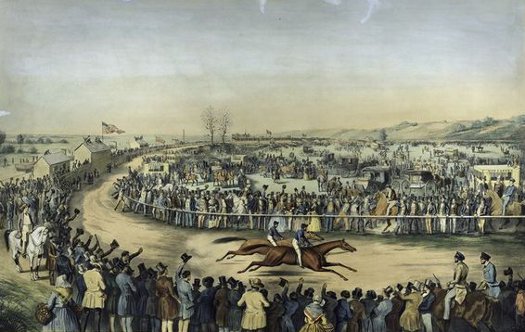

In a time before basketball, football, and hockey, horse racing was America’s most popular sport. Especially anticipated were races that played up sectional hostilities — pitting a Southern-bred horse against a Northern one

Southern men felt that vices like drinking and gambling didn’t make them less of a man, but more of one, because they, just like their Scotch-Irish ancestors, saw its role in building and managing the honor group. As we’ve discussed, in honor groups men challenge and test each other to earn status, and also to prepare each other to face a common enemy. In peace-time, men use games, sports, and drinking to accomplish this. Such diversions give men a chance to best their rivals without rocking the social boat. And through all this friendly competition, camaraderie is built and bonds between men are strengthened.

The “gander pull” was a popular Southern pastime. An old tough male goose (gander) was strung up and its neck slathered with grease. Male contestants, fortified with whisky , would ride under the goose, reach for its neck, and attempt to pull the head off. The ladies would cheer for their “knights,” and hope their man would be the one to present the head to them as a trophy.

Sports gave Southern men a chance to demonstrate their physical prowess — gambling, one’s strategic skill. Even in games of chance, winning boosted a man’s status. Johann Huizinga explains that a lucky win “had a sacred significance; the fall of the dice may signify and determine divine workings.” Winning meant God favored you and deemed you worthy of praise from your brethren. That’s why cheating constituted the ultimate dishonor and was worthy of death; it was an attempt to unfairly gain status and thwart the will of the gods.

Cheating was sometimes punishable by death.

Fathers in the Old South initiated their sons into the “manly art” of gambling at an early age so they would be ready to take part in the world of men. “Betting,” according to Wyatt-Brown, “was almost a social obligation when men gathered at barbecues, taverns, musters, supper and jockey clubs, race tracks, and on steamboats.” To not ante up was to deny your equal standing with your fellow men, and thus refusing to play “implied cowardice, differentness, unwholesome and even antisocial behavior.” However, compulsive gambling, which consumed one’s inheritance, and the failure to pay a gambling debt were seen as very shameful.

Drinking served the same purpose as gambling. It brought men together and acted as a sorting mechanism for status within the group. The man who could drink the most and hold his liquor showed hardihood and earned the admiration of his peers. Intoxication also heightened the chances that men would provoke or dare each other into fights or hijinks – opportunities for a rollickin’ good time and further tests of manhood.

3. Fighting and Dueling

“The Palmetto State: Her sons bold and chivalrous in war, mild and persuasive in peace, their spirits flush with resentment for wrong.” — toast of J.J. McKilla, at Independence Day militia banquet in Sumterville, South Carolina, 1854

As we’ve mentioned in previous posts, traditional honor began with your own claim to honor, but then that claim had to be ratified by one’s peers. If one of your fellows disavowed your claim, and said the image you projected was false, this was a grave insult; if you tolerated the insult, you essentially let another man dominate you, and thus lost status in the group. Fighting the accuser allowed you to maintain your honorable reputation; if you beat or killed him, you demonstrated that he was wrong, whether his insult had been true or not.

An accuser knew when he was intentionally drawing a man into a fight; calling another man a coward (or in the parlance of the time a “poltroon” or “puppy”) was essentially a declaration you wanted to duel or duke it out. Insulting a man’s honesty in the South, known as “giving the lie,” had the same effect and was sure to provoke instantaneous rage. Ditto for doing wrong to a man’s wife, mother, or daughter; Southerners prided themselves on their chivalry. But whether it was a man’s courage or his integrity that was questioned, the recourse was always the same: violence.

While childrearing in the North emphasized the cultivation of inner conscience , and the feeling of guilt in wrongdoing, Southern parents instilled in their progeny a sense of honor , and feeling shame for violating the code. Young boys were encouraged by both their parents and the community to be aggressive and manly, and to fight to defend one’s honor from an early age. And it wasn’t just fathers who sought to impress upon their sons the importance of personal valor; mothers were equally adamant on this point. For example, Sam Houston’s mother urged him to fight in the War of 1812, and when he decided to join up, she gave him a plain gold ring with “Honor” engraved inside it, and then handed him a musket saying, “Never disgrace it; for remember, I had rather all my sons should fill one honorable grave, than that one of them should turn his back to save his life.”

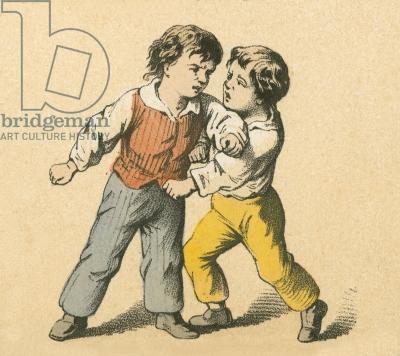

Boys were taught that even if you got creamed, simply showing your willingness to fight demonstrated your manhood. A story recalled by James Ross, born 1801, illustrates this well. When he was six, Ross bought a knife, but then lost it, and in his naivety, returned to the storekeeper who had sold it to him for a refund of his money. The boy argued with the shopkeep for a while, and some other boys in the store began laughing at him, making him feel ridiculous. When Ross saw a boy he already disliked among the laughing crowd, he fell upon him, and the two proceeded to engage in a long and unmerciful scuffle as the other boys gathered in a circle to watch. When he could no longer go on, Ross was told he had been whipped, and began to make his way home, thoroughly dejected and humiliated. But then an older, more respected boy who had witnessed the fight came over and offered him this advice: “I must cheer up—adding that I had done exactly right; every man ought to fight when insulted; being whipped was nothing; he had been whipped twenty times and was none the worse for it; I had fought bravely; all the boys said so; and he thought a great deal more of me than he did before. This talk comforted me wonderfully and all my troubles soon vanished. It is true my ribs felt sore for several days, but I cared little for that.”

Seldom did a boy of any class make it to adolescence without getting into a fight, or several. For poor boys, as they grew into men they were expected to begin to participate in what was called the “rough and tumble.” A rough and tumble was a no-holds-barred fight where the first man to cry “uncle” lost, and opponents sought to disfigure and maim each other to claim victory; fights often ended when one employed “The Gouge” – scooping the other man’s eyeball out of its socket.

“As far as it can be done, we should live peaceably with our associates; but, as we cannot always do so, it is necessary occasionally to resist. And when our honor demands resistance, it should be done with courage.” –Advice of North Carolinian William Pettigrew to his younger brother

For middle and upper class boys, schoolyard scraps quickly evolved into true “affairs of honor;” teenage duels were not uncommon in the South. Introduced to the US by French and British aristocrats during the Revolutionary War, the Southern upper classes saw dueling as a way to fight and show courage that distinguished itself from the heedless, ugly “rough and tumbles” of their lower class brethren. While theirs were bodily fights of immediate passion, duels were carefully orchestrated rituals between gentlemen who considered each other equals (an insult from an inferior was not worthy of notice). That it required a man to resist the urge to punch a man right on the spot made the duel seem a much more gentlemanly and honorable form of combat. Duels were governed by an elaborate set of rules, and could take weeks and even months to arrange. During that time, the men’s chosen “seconds” (a man’s representative and duel referee) would try to negotiate a peaceful resolution in order to avoid bloodshed.

Even for those showdowns that did make it to the “field of honor,” only 20% of duels ended in a fatality. Gentlemen often aimed for an appendage or deliberately missed. Dueling was much more about demonstrating one’s willingness to literally die for one’s honor, than it was about killing another man; it symbolized the culture’s belief that dishonor was worse than death . Southerners scoffed at the way Northern men used the word honor, but defended an insult with a fist fight or a contemptuous laugh and turn of the heel; an honor not worth dying for was not honor at all.

Dueling was seen by some as a way to head off feuds, and as an incentive for gentlemen to conduct themselves in the most upright manner. But it always had its critics and was the most controversial of the three pillars – even Jefferson Davis condemned it. Yet even as Southern states outlawed the practice and anti-dueling societies arose, gentlemen continued to participate in the ritual without much public censure during the antebellum period. Including violence, even if in a ritualized way, allowed upper class men to hold onto the essential nature of traditional honor; the celebration of personal valor tied all classes of whites together.

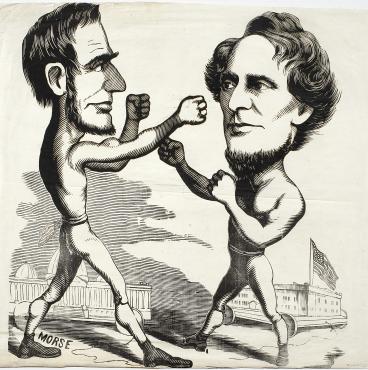

Southern Honor and the Civil War

While folks still debate whether the Civil War was primarily about states’ rights or slavery, an argument can in fact be made that it was also largely about something that has subsequently been lost to time: honor.

Both sides saw and referred to the struggle as a duel ; as Wyatt-Brown puts it, “for many, the Civil War was reduced to a simple test of manhood.”

In the South, William L. Yancey told the 1860 Democratic convention in Charleston:

“Ours is the property invaded; ours are the institutions which are at stake; ours in the peace that is to be destroyed; ours is the honor at stake–the honor of children, the honor of families, the lives, perhaps, of all.”

In the North, Lorien Foote describes a report in the popular magazine Harper’s Weekly “about the private meeting among some of the leading gentlemen of New York City in the tense days of the secession crisis. When one participant proposed to ‘accede’ to all the south’s demands, others jumped to their feet to denounce such a ‘total, unqualified, abject surrender in advance of all national and individual honor.’ They demanded that the men of the north at least ‘strike one blow for our own honor’ rather than ‘deliberately to relinquish our manhood.’”

The conflict between North and South was depicted by cartoonists as a fist fight between Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis.

While both the North and the South saw the war in terms of honor, what motivated the men to fight differed greatly. In the North, volunteers joined the cause because of more abstract ideals like freedom, equality, democracy, and Union. In the South, men grabbed their rifles to protect something more tangible — hearth and home — their families and way of life. Their motivation was rooted in their deeply entrenched loyalty to people and place.

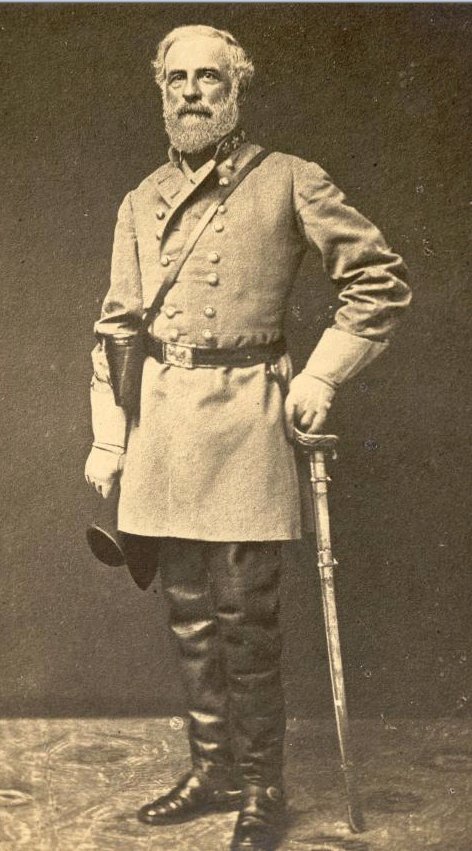

But what if a man felt allegiance both to the principles espoused by the North, and the honor of the South? The ancient Greeks had grappled with what to do when one’s loyalties to one’s honor group conflicted with one’s loyalty to conscience. Such a conflict has been a struggle for warriors ever since, and is best embodied during this time in the life of Robert E. Lee.

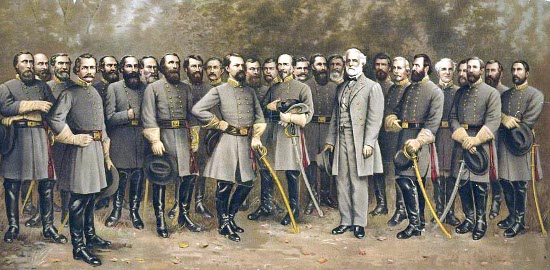

Lee was the perfect example of the South’s genteel honor code and what William Alexander Percy called the “broad-sword tradition:” “a dedication to manly valor in battle; coolness under fire; sacrifice of self to succor and protect comrades, family, and country; magnamity; gracious manners; prudence in council; deference to ladies; and finally, stoic acceptance of what Providence has dictated.” He had also served and greatly distinguished himself in the United States Army for 32 years, so much so, that as the Civil War loomed, Lincoln offered Lee command of the Union forces. Lee was torn; in the days before secession, he wrote, “I wish to live under no other government & there is no sacrifice I am not ready to make for the preservation of the Union save that of honor .” Lee did not favor secession and wished for a peaceable solution instead; but his home state of Virginia seceded, and he was thus faced with the decision to remain loyal to the Union and take up arms against his people, or break with the Union to fight against his former comrades. He chose the latter. Lee’s wife (who privately sympathized with the Union cause) said this of her husband’s decision: “[He] has wept tears of blood over this terrible war, but as a man of honor and a Virginian, he must follow the destiny of his State.” In a traditional honor culture, loyalty to your honor group takes precedence over all other demands — even those of one’s own conscience.

Many other Southerners of divided loyalties made the same choice as Lee. United in opposition to the encroachment of outsiders, the perceived threat to their autonomy, and simply the necessity of showing honor by adopting an aggressive stance and fighting when insulted, the vast majority of white Southerners, whether slave-owners or not, took up arms for the Confederacy. Because of their shared honor code, there was, at least at first, a great deal of unity in the “solid South,” and less of the socioeconomic clashes that arose between the gentlemen and the roughs in the Union Army . For example, while the average personal wealth for company officers in the Confederate Army was $88,500, for noncoms and privates it was $760 – an incredible gulf. And yet company officers were elected by troops themselves – showing that they saw such men as their natural leaders.

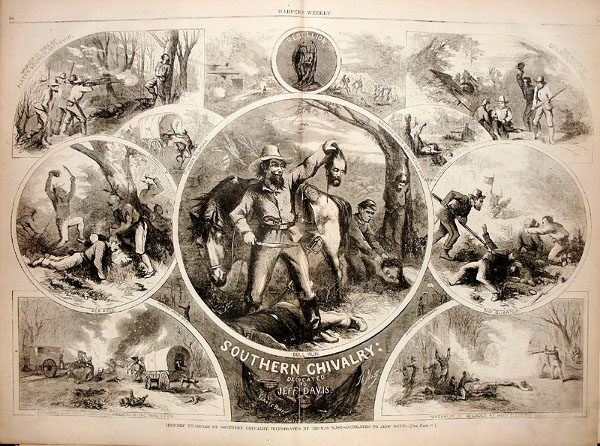

Northerners were long critical of the South’s claims to chivalry, as depicted in this Thomas Nast cartoon from Harper’s Weekly.

Greater conflict would arise in the South, as it had in the North, when the Confederacy instituted conscription. Some chafed at this insult to their personal mastery of their lives, as well as Jefferson Davis’ suspension of habeas corpus, wartime inflation, and laws that exempted men who owned 15 slaves or more from the draft. These and other onerous effects of the conflict led some lower class men to grumble that it was a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

In some ways, the South’s traditional honor code worked against the Confederacy’s efforts. A man would sometimes only agree to enlist if given a guarantee that he’d be retained in his own county or state – he was interested in fighting to protect his kin, not on some anonymous battlefield a few states over. For that same reason, drafted men, particularly if married, would often desert their unit if they were transferred far from home. And if a family emergency arose, or his wife and children needed help bringing in the crop, a man felt justified in going AWOL. Southern honor demanded loyalty to one’s people and place above all, and devotion to family and home was the highest of those sacred obligations.

Southern Honor Culture Lives On

Although the Civil War ended almost 150 years ago, 4 in 10 Southerners still sympathize with the Confederacy . While I won’t wade into the endless debate over whether, and to what extent, this attachment to history is appropriate, I will say that what is invariably missing from the debate, and crucial to fully apprehending it, is an understanding of the culture of Southern honor. The echoes of that culture go far beyond the displaying of the Confederate flag, and still influence the behavior of many Southern men to this day.

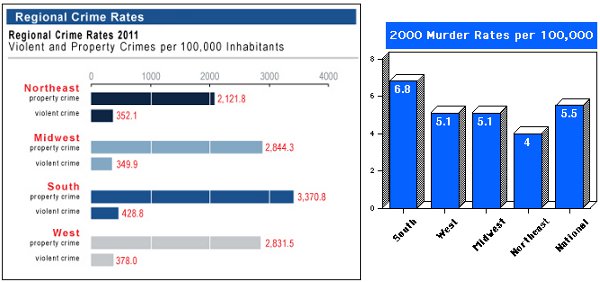

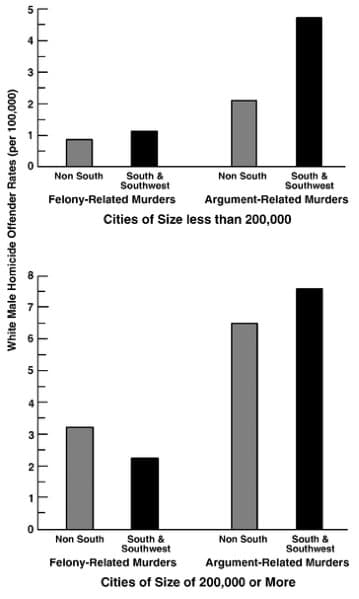

Since the end of the war until now, the South has had an overall higher rate of violent crime and of homicide specifically, than the Northeast. Compare, for example, two quintessential Southern and Northern states: South Carolina and Massachusetts. According to the US Census , in 2007 SC ranked first in the country as to the number of violent crimes per 100,000 people (788), while Massachusetts came in at twenty-second with nearly half that (432).

Chart Source: Culture Of Honor: The Psychology Of Violence In The South by Richard E Nisbett and Dov Cohen

However, when you start to analyze the data further, things get much more interesting. Psychologists Richard Nisbett and Dov Cohen looked at homicide stats for the North and South, and found that once you separate the murders into two categories — argument/conflict-related and felony-related — the South only has a significantly higher rate when it comes to the former. What this means is that murders in the North are more likely to occur during the course of another crime, like burglary, and involve strangers, whereas murders in the South are more likely to arise from a personal conflict, such as a barfight or love triangle. Other studies have shown that only homicides that involve a victim personally known to the perpetrator are elevated in the South compared to other regions of the country. Most interesting of all is the fact that this effect is correlated to the size of a town or city. In medium-size cities (pop. 50k-200k), Southern white males commit murder at a rate of 2 to 1 when compared to the rest of the country; in small cities (pop. 10k-50k) the ratio is 3 to 1; in rural areas it is 4 to 1. After reading this post, you can probably guess why this is so – a small town provides the intimate, face-to-face relationships that are essential to an honor culture, and creates an environment where everyone knows your reputation, and an insult to it can lead to violent altercations.

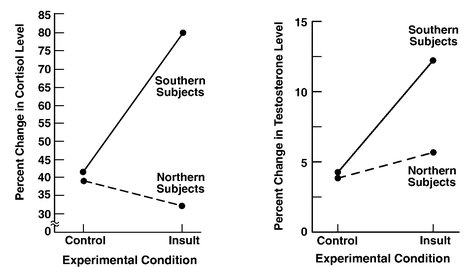

Nisbett and Cohen followed up their findings with a study that looked at the differences between the emotional and physiological responses of Northern and Southern white men when faced with an insult. They had both Northern and Southern college-age men come into the lab under the pretense of taking part in an unrelated study. They were asked to take a questionnaire to a room at the end of a long and narrow hallway, and as they made their way down it, a confederate to the experimenters would bump into the subject, and call him an “asshole.” During this altercation, the subjects’ emotional response was recorded, and afterwards their levels of cortisol (which is released from arousal and stress), and testosterone (which increases when gearing up for something that will involve aggression and dominance) were measured. The result? Nisbett and Cohen found that Northern men reacted with more amusement to the insult than anger, while the Southerners reacted with more anger than amusement. Their physiological response differed too. The cortisol levels of insulted Northerners rose 33%, even less than the control Northerners who walked down the hallway without being bumped at all. But the cortisol levels of insulted Southerners went up more than double that: 79%. The testosterone levels of Northern increased by 6%, but went up 12% for Southerners.

All of which is to say that in their reaction to insult, Southern men today remain tied, both culturally and physiologically, to their antebellum forbearers, and to their Scotch-Irish ancestors.

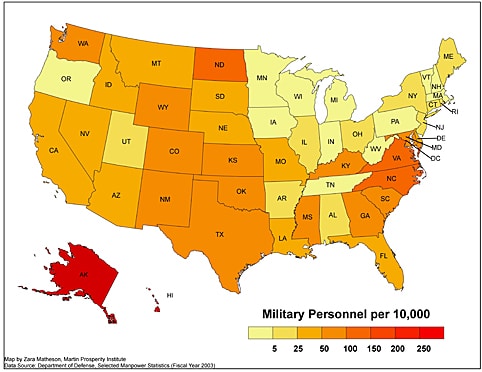

This is true when it comes to those ancestors’ warrior values as well. Before the Civil War, Southerners occupied nearly every important position in the US Army, could claim the lion’s share of its most distinguished commanders, and had served as Secretary of War every year in the decade and a half prior to secession. Overall, Southern families contributed more sons to the Army than the North, despite the difference in population. And this too remains true today. As you can see from this map (which is controlled for population), many more service members are based in the South (and in the Western frontier states where an honor culture also thrived in the 19 th century) than in the Northeast:

Since this has gone on so long, let’s make this the shortest conclusion possible. While we said in the last post that after the Civil War, the North’s Stoic-Christian honor code triumphed over the South’s traditional one, it would really be more accurate to say that each region’s respective code continued on for a few more decades. But despite the echoes that remain in the South today, the public, cultural nature of neither code were any match for the increasing urbanization, diversification, and shifting values of the US in the 20 th century. Which is where we’ll turn next.

Manly Honor Series: Part I: What is Honor? Part II: The Decline of Traditional Honor in the West, Ancient Greece to the Romantic Period Part III: The Victorian Era and the Development of the Stoic-Christian Code of Honor Part IV: The Gentlemen and the Roughs: The Collision of Two Honor Codes in the American North Part V: Honor in the American South Part VI: The Decline of Traditional Honor in the West in the 20th Century Part VII: How and Why to Revive Manly Honor in the Twenty-First Century Podcast: The Gentlemen and the Roughs with Dr. Lorien Foote ________________________

Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South by Bertram Wyatt-Brown

Plain Folk of the Old South by Frank Lawrence Owsley

Common Whites: Class and Culture in Antebellum North Carolina by Bill Cecil-Fronsman

Cracker Culture: Celtic Ways in the Old South by Grady McWhiney

Culture Of Honor: The Psychology Of Violence In The South by Richard E Nisbett and Dov Cohen

The Gentlemen and the Roughs: Violence, Honor, and Manhood in the Union Army by Lorien Foote

Related Posts

Subscriber Only Resources?

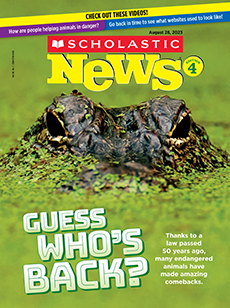

Access this article and hundreds more like it with a subscription to Scholastic News magazine.

Article Options

Honor or Insult?

Washington, d.c.’s pro football team has been called the redskins for more than 80 years. many people say it’s time for a change..

DAVID J. PHILLIP/AP IMAGES

A Washington Redskins fan wore a feathered headdress at a game last year.

The Washington Redskins face tough opponents during football games each week. But lately, one of the team’s biggest battles has been taking place off the field.

Many people want the team to change its name and logo. They say the symbols are insulting to American Indians (also called Native Americans).

The controversy over the Redskins name is the latest chapter in a long argument over American Indian team names. Since 1970, more than 2,000 high school and college teams have changed their Indian-themed names. Should the Redskins change theirs too?

What's in a Name?

RICH SCHULTZ/GETTY IMAGES

Former Washington Redskins quarterback Kirk Cousins

Many people dislike the name Redskins because they say it’s offensive. It’s considered a cruel way to describe Native Americans.

Tara Houska is a lawyer fighting to get rid of Native American team names. She points out that few people would ever call a Native American a redskin to his or her face, because they know it’s an offensive word.

However, many fans don’t want the team to give up its name. They say it’s an important part of football history. The team has been called the Redskins since 1933. Daniel Snyder, the team’s owner, has promised never to change the name.

“We owe it to our fans and coaches and players, past and present, to preserve that heritage,” he wrote in a letter to fans in 2013.

ANN HEISENFELT/AP IMAGES

Native American protesters march outside a Washington Redskins game.

Redskins isn’t the only team name that has come under fire. People argue that teams should drop names like Chiefs and Indians too. Critics of these names say the teams’ mascots—and fans who dress up like them—are a big part of the problem.

American Indian mascots often look the same. They wear war paint on their faces and carry weapons called tomahawks. Many Native Americans point out that this makes them seem violent or like cartoon characters.

Many people also argue that the mascots give people the idea that all American Indians are alike. More than 500 tribes live in the United States. Each has its own history and traditions. But when fans wear “Indian” costumes or headdresses, it suggests that American Indians are one big group with the same clothing and customs.

Also, wearing a headdress is considered an honor among the tribes that use them. When fans wear them to sporting events, it’s seen as disrespectful.

“Your actual race and culture are viewed as a costume, and it’s really hurtful,” Houska says.

Still, many people think that these team names and mascots actually honor Native American cultures. They argue that names like Braves and Chiefs celebrate values like strength and bravery. The team names are even a source of pride among some tribes (see “ Support for the Seminoles ”).

The Next Chapter

Today, about 2,000 high school, college, and pro teams have Indian-themed names and logos. But that number is falling each year.

Last month, California Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill that will make the state the first to ban public schools from using the Redskins name or logo. Schools in the state that use the name have until January 2017 to change it.

Luis Alejo is the lawmaker who wrote the bill. He says the ban is about showing respect for all cultures.

“This is a great opportunity to create a new identity . . . that inspires joy and pride for all students,” Alejo said.

Support for the Seminoles

A football game is about to start at Florida State University (FSU). Suddenly, a student on horseback gallops across the field. He’s wearing war paint and holding a burning spear. The crowd goes wild. The student is dressed as Chief Osceola (oh-see-OH-la), a famous leader of the Seminole tribe from the 1800s.

FSU is one of the few major college teams with an American Indian name and mascot. The NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) oversees major college sports. In 2005, the NCAA told 18 teams to drop their Indian names and logos.

But the Seminole Tribe of Florida gave FSU permission to use the name and mascot ( below ). They say FSU is honoring their history.

“We Seminoles embrace the mascot,” says James Billie, the tribe’s leader.

STACY REVERE/GETTY IMAGES

Part of the Text Set:

A bumpy train ride: a field experiment on insult, honor, and emotional reactions.

The present research examined the relationship between adherence to honor norms and emotional reactions after an insult. Participants were 42 Dutch male train travelers, half of whom were insulted by a confederate who bumped into the participant and made a degrading remark. Compared with insulted participants with a weak adherence to honor norms, insulted participants with a strong adherence to honor norms were (a) more angry, (b) less joyful, (c) less fearful, and (d) less resigned. Moreover, insulted participants with a strong adherence to honor norms perceived more anger in subsequent stimuli than not-insulted participants with a strong adherence to these norms. The present findings support a direct relationship among insult, adherence to honor norms, and emotional reactions.

Related Papers

Marcello Gallucci

The present research examined the relationship between adherence to honor norms and emotional reactions after an insult. Participants were 42 Dutch male train travelers, half of whom were insulted by a confederate who bumped into the participant and made a degrading remark. Compared with insulted participants with a weak adherence to honor norms, insulted participants with a strong adherence to honor norms were (a) more angry,(b) less joyful,(c) less fearful, and (d) less resigned. Moreover, insulted participants with a ...

Cognition & Emotion

Antony S R Manstead

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

Francesca D'Errico

The paper presents a survey study that investigates the self-conscious emotion of feeling offended and provides an account of it in terms of a socio-cognitive model of emotions. Based on the qualitative and quantitative analysis of the participants' answers, the study provides a definition of offense and of the feeling of offense in terms of its " mental ingredients, " the beliefs and goals represented in a person who feels this emotion, and finds out what are its necessary and aggravating conditions, what are the explicit and implicit causes of offense (the other's actions, omissions, inferred mental states), what negative evaluations are offensive and why. It also shows that the feeling of offense is not only triggered about honor or public image, but it is mainly felt in personal affective relationships. The paper finally highlights that high self-esteem may protect a person against the feeling of offense and the constellation of negative emotions triggered by it.

Group Processes & Intergroup Relations

Hannah Wilkerson

Human Relations

Yiannis GABRIEL

The social psychology of …

Ronnie Janoff-bulman

CHAPTER 7 The Social Psychology of Respect: Implications for Delegitimization and Reconciliation Ronnie Janoff-Bulman and Amelie Werther In both ... to reflect respect or disrespect (eg, Barreto & Ellemers, 2002; Boeckmann & Tyler, 2002; Branscombe, Spears, Ellemers, & ...

Patricia M Rodriguez Mosquera

Page 1. The role of honour concerns in emotional reactions to offences Patricia M. Rodriguez Mosquera, Antony SR Manstead, and Agneta H. Fischer University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands We investigated the role of honour ...

Peter Coleman

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

SSRN Electronic Journal

Tae-Yeol Kim , Debra Shapiro

Hammad Sheikh

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

Emanuele Castano

luvell anderson

Daphna Oyserman

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

Zeynep Sunbay

Annual Review of Psychology

Dale Miller

Elena Gaviria

Systemic Humiliation in America

Karyna Korostelina

Gavin B Sullivan

SPELL: Swiss Papers in English Language and Literature 30: 67-88.

Jonathan Culpeper

Journal of Research in Personality

Donald Lynam

Thierry Devos

IACM 24th Annual Conference Paper

Dorit Efrat-Treister

Journal of Applied Social Psychology

Lieven Brebels

Daniel Balliet

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Free associations

Digressions on psychology, society and culture

The psychology of insults

Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne

University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

With the Trump presidency we may be entering a golden age of insult and name-calling. Trump himself is exercising leadership in this regard. No fewer than 305 people, places and things have felt the sting of his derisive tweets .

Psychology has recently swung towards the study of the positive side of human experience. However a few brave researchers have explored the intricacies of verbal abuse. Their work offers an intriguing perspective on the ways in which we disparage one another, and the values derogatory terms reinforce.

Basic forms of verbal abuse

One of the most interesting lines of research investigates the basic forms that verbal abuse takes. Do insults share a few common themes, and what might they be?

A pioneering study addressed this question by examining highly evaluative personality characteristics. These characteristics were omitted from earlier studies that established the fundamental dimensions of human personality: the so called “Big Five”. Because they say more about the ill feeling of the user than the attributes of the person described they were deliberately set aside. But for precisely this reason they may reveal the fundamental dimensions of human animus.

I shall call these the “Foul Four” because the researchers showed words conveying negative evaluations exemplify four themes. Those themes are worthlessness, stupidity, depravity and peculiarity.

Words conveying “worthlessness” – such as piddling, pointless or incapable – signify that a person lacks all value or merit. Those conveying “stupidity” – brainless, dumb or moronic – communicate a lack of intellect. Those conveying “depravity” – beastly, disgraceful or deplorable – indicate immorality. “Peculiarity” terms – odd, bizarre, warped – signal violations of social convention.

These primary dimensions of negative evaluation conceal deeply held values. We use them when we judge others to have transgressed four kinds of standard. We value power, intelligence, morality and normality, and when people violate these values we show our disapproval with corresponding abusive expressions.

Of course, we don’t all hold these values equally. A cursory inspection of Trump’s twittering shows he specialises in the language of worthlessness. Enemies are routinely derided as “weak”, “ineffective”, “incompetent”, “failing”, “lightweight”, “third-rate”, “losers” or simply the “worst” at something or other. These insults are belittling, communicating a perspective of power and rank looking downward.

Stupidity, depravity and peculiarity are lesser quills in Trump’s rhetorical quiver. Opponents are frequently dismissed as “stupid”, “dopey”, “dumb as rocks” or “clowns”. Selected others were singled out for supposed immorality, most famously “crooked Hillary”, the rigged electoral system that delivered his victory and the corrupt liberal media. Rare individuals, notably Bernie Sanders, are damned for their rarity, ridiculed as “wacko” and “crazy”.

Insults and culture

Donald Trump derides his adversaries in a form of English, but the language of insult varies around the globe. Indeed, some fascinating work compares insults across cultures. One such study examined insulting expressions from eleven distinct language communities.

The researchers sampled almost 3,000 people, asking each how they might respond if someone rudely and unapologetically bumped into them. About 12,000 pungent expressions were generated. Their content varied revealingly between different national groups.

Germans, Americans and Italians were especially drawn to anal terms of abuse, such as variations on “asshole”, whereas Spaniards preferred to query the offender’s intelligence. British and Dutch participants leaned towards genital terminology, and Norwegians specialised in satanic expressions. Animal terms and sexual inadequacies and abnormalities were also common.

One finding of this study was that abusive terms implicating the offender’s family members were only common in some Mediterranean cultures. This kind of verbal abuse was the focus of my favourite study in the psychology of insults. The authors of the study used insults as a window into cultural differences in the understandings of personhood.

In collectivist cultures, they reasoned, people see themselves as inextricably embedded in a web of family relationships. Insults will therefore tear at the web rather than targeting the person in isolation. In individualist cultures, where people see themselves as autonomous and separate, insults are more likely to disparage the singular person.

The researchers collected an anthology of insults from participants in several cities in Italy, where the north tends to be less collectivist than the south. They classified insults as individualistic or relational. The former disparage the person’s intellect, physical features, manners or sexuality. The latter target family members, taboo family relationships or stigmatised group identities.

Sure enough, southern Italians were more likely to make relational insults than northerners (for example, “eff off, you and 36 of your relatives”). Individualistic northerners, in turn, were especially prone to deride an individual’s intelligence while sparing their relations.

How we disparage others reveals who we are and what we value. As a supreme individualist who values competition we should not be surprised Donald Trump repeatedly savages his competitors for their supposed personal failings.

At some level this is a rather harmless way to express hostility. As Freud wrote, “the man who first flung a word of abuse at his enemy instead of a spear was the founder of civilisation”. We might just hope that the 45th president becomes a little more civil.

- Donald Trump

- Trump administration

Social Media Producer

Post Doctoral Research Fellow, Generative AI

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Senior Research Fellow - Curtin Institute for Energy Transition (CIET)

Laboratory Head - RNA Biology

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Culture of Honor

Culture of honor definition.

A culture of honor is a culture in which a person (usually a man) feels obliged to protect his or her reputation by answering insults, affronts, and threats, oftentimes through the use of violence. Cultures of honor have been independently invented many times across the world. Three well-known examples of cultures of honor include cultures of honor in parts of the Middle East, the southern United States, and inner-city neighborhoods (of the United States and elsewhere) that are controlled by gangs.

Cultures of honor can vary in many ways. Some stress female chastity to an extreme degree, whereas others do not. Some have strong norms for hospitality and politeness toward strangers, whereas others actively encourage aggression against outsiders. What all cultures of honor share, however, is the central importance placed on insult and threat and the necessity of responding to them with violence or the threat of violence.

Many violent incidents in cultures of honor center on what might be considered a trivial incident to outsiders. Such matters are not trivial to the people in the argument, however, because people are defending (or establishing) their reputations. What is really at stake is something of far greater importance than a one-dollar debt owed or a record on the jukebox.

In cultures of honor, reputation is highly tied up with masculinity. A telling anecdote from Hodding Carter’s book Southern Legacy (1950) concerned a 1930s Louisiana court case, in which Carter served as a juror. The facts of the matter were clear. The defendant lived near a gas station and had been pestered for some time by workers there. One day, the man had had enough and opened fire on the workers, killing one person and wounding two others. As Carter tells it, the case seemed open and shut, and so Carter began discussions in the jury room by offering up the obvious (to him) verdict of guilty. The other 11 jurors had very different ideas about the obvious verdict, however, and they strongly and unanimously favored acquittal. Fellow jurors explained to Carter that the man couldn’t be guilty—what kind of man wouldn’t have shot the others? An elder juror later told Carter that a man can’t be jailed for standing up for his rights. In cultures of honor everywhere, traditional masculinity is a virtue that has to be defended.