Writing a history essay

An essay is a piece of sustained writing in response to a question, topic or issue. Essays are commonly used for assessing and evaluating student progress in history. History essays test a range of skills including historical understanding, interpretation and analysis, planning, research and writing.

To write an effective essay, students should examine the question, understand its focus and requirements, acquire information and evidence through research, then construct a clear and well-organised response. Writing a good history essay should be rigorous and challenging, even for stronger students. As with other skills, essay writing develops and improves over time. Each essay you complete helps you become more competent and confident in exercising these skills.

Study the question

This is an obvious tip but one sadly neglected by some students. The first step to writing a good essay, whatever the subject or topic, is to give plenty of thought to the question.

An essay question will set some kind of task or challenge. It might ask you to explain the causes and/or effects of a particular event or situation. It might ask if you agree or disagree with a statement. It might ask you to describe and analyse the causes and/or effects of a particular action or event. Or it might ask you to evaluate the relative significance of a person, group or event.

You should begin by reading the essay question several times. Underline, highlight or annotate keywords or terms in the text of the question. Think about what it requires you to do. Who or what does it want you to concentrate on? Does it state or imply a particular timeframe? What problem or issue does it want you to address?

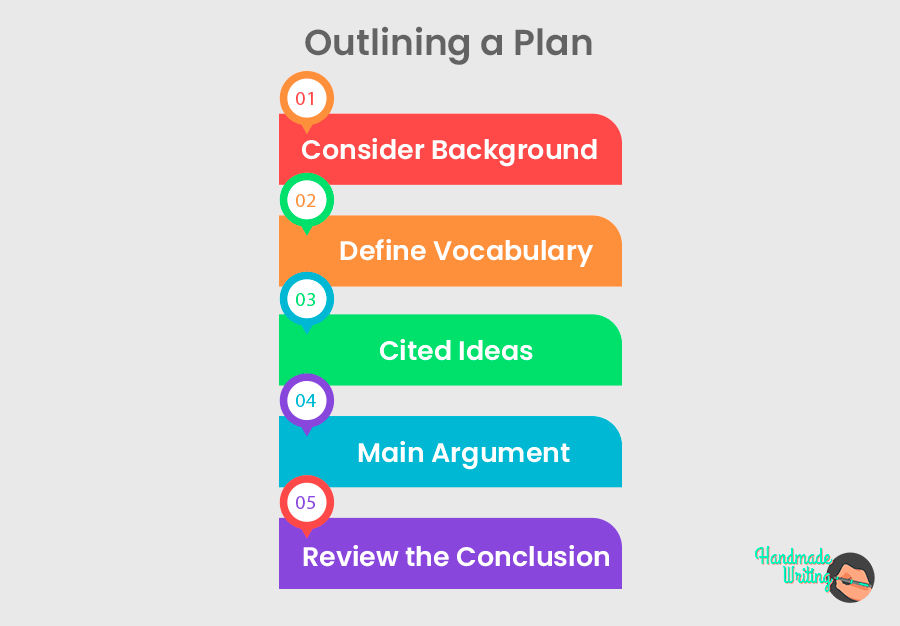

Begin with a plan

Every essay should begin with a written plan. Start constructing a plan as soon as you have received your essay question and given it some thought.

Prepare for research by brainstorming and jotting down your thoughts and ideas. What are your initial responses or thoughts about the question? What topics, events, people or issues are connected with the question? Do any additional questions or issues flow from the question? What topics or events do you need to learn more about? What historians or sources might be useful?

If you encounter a mental ‘brick wall’ or are uncertain about how to approach the question, don’t hesitate to discuss it with someone else. Consult your teacher, a capable classmate or someone you trust. Bear in mind too that once you start researching, your plan may change as you locate new information.

Start researching

After studying the question and developing an initial plan, start to gather information and evidence.

Most will start by reading an overview of the topic or issue, usually in some reliable secondary sources. This will refresh or build your existing understanding of the topic and provide a basis for further questions or investigation.

Your research should take shape from here, guided by the essay question and your own planning. Identify terms or concepts you do not know and find out what they mean. As you locate information, ask yourself if it is relevant or useful for addressing the question. Be creative with your research, looking in a variety of places.

If you have difficulty locating information, seek advice from your teacher or someone you trust.

Develop a contention

All good history essays have a clear and strong contention. A contention is the main idea or argument of your essay. It serves both as an answer to the question and the focal point of your writing.

Ideally, you should be able to express your contention as a single sentence. For example, the following contention might form the basis of an essay question on the rise of the Nazis:

Q. Why did the Nazi Party win 37 per cent of the vote in July 1932? A. The Nazi Party’s electoral success of 1932 was a result of economic suffering caused by the Great Depression, public dissatisfaction with the Weimar Republic’s democratic political system and mainstream parties, and Nazi propaganda that promised a return to traditional social, political and economic values.

An essay using this contention would then go on to explain and justify these statements in greater detail. It will also support the contention with argument and evidence.

At some point in your research, you should begin thinking about a contention for your essay. Remember, you should be able to express it briefly as if addressing the essay question in a single sentence, or summing up in a debate.

Try to frame your contention so that is strong, authoritative and convincing. It should sound like the voice of someone well informed about the subject and confident about their answer.

Plan an essay structure

Once most of your research is complete and you have a strong contention, start jotting down a possible essay structure. This need not be complicated, a few lines or dot points is ample.

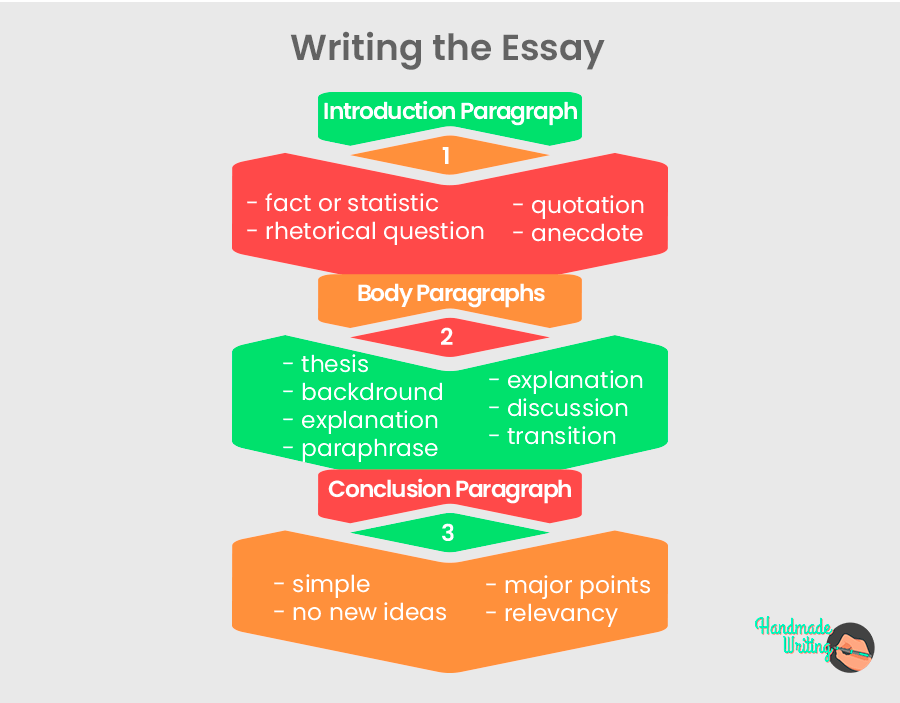

Every essay must have an introduction, a body of several paragraphs and a conclusion. Your paragraphs should be well organised and follow a logical sequence.

You can organise paragraphs in two ways: chronologically (covering events or topics in the order they occurred) or thematically (covering events or topics based on their relevance or significance). Every paragraph should be clearly signposted in the topic sentence.

Once you have finalised a plan for your essay, commence your draft.

Write a compelling introduction

Many consider the introduction to be the most important part of an essay. It is important for several reasons. It is the reader’s first experience of your essay. It is where you first address the question and express your contention. It is also where you lay out or ‘signpost’ the direction your essay will take.

Aim for an introduction that is clear, confident and punchy. Get straight to the point – do not waste time with a rambling or storytelling introduction.

Start by providing a little context, then address the question, articulate your contention and indicate what direction your essay will take.

Write fully formed paragraphs

Many history students fall into the trap of writing short paragraphs, sometimes containing as little as one or two sentences. A good history essay contains paragraphs that are themselves ‘mini-essays’, usually between 100-200 words each.

A paragraph should focus on one topic or issue only – but it should contain a thorough exploration of that topic or issue.

A good paragraph will begin with an effective opening sentence, sometimes called a topic sentence or signposting sentence. This sentence introduces the paragraph topic and briefly explains its significance to the question and your contention. Good paragraphs also contain thorough explanations, some analysis and evidence, and perhaps a quotation or two.

Finish with an effective conclusion

The conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay. A good conclusion should do two things. First, it should reiterate or restate the contention of your essay. Second, it should close off your essay, ideally with a polished ending that is not abrupt or awkward.

One effective way to do this is with a brief summary of ‘what happened next’. For example, an essay discussing Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 might close with a couple of sentences about how he consolidated and strengthened his power in 1934-35.

Your conclusion need not be as long or as developed as your body paragraphs. You should avoid introducing new information or evidence in the conclusion.

Reference and cite your sources

A history essay is only likely to succeed if it is appropriately referenced. Your essay should support its information, ideas and arguments with citations or references to reliable sources.

Referencing not only acknowledges the work of others, but it also gives authority to your writing and provides the teacher or assessor with an insight into your research. More information on referencing a piece of history writing can be found here .

Proofread, edit and seek feedback

Every essay should be proofread, edited and, if necessary, re-drafted before being submitted for assessment. Essays should ideally be completed well before their due date then put aside for a day or two before proofreading.

When proofreading, look first for spelling and grammatical errors, typographical mistakes, incorrect dates or other errors of fact.

Think then about how you can improve the clarity, tone and structure of your essay. Does your essay follow a logical structure or sequence? Is the signposting in your essay clear and effective? Are some sentences too long or ‘rambling’? Do you repeat yourself? Do paragraphs need to be expanded, fine-tuned or strengthened with more evidence?

Read your essay aloud, either to yourself or another person. Seek feedback and advice from a good writer or someone you trust (they need not have expertise in history, only in effective writing).

Some general tips on writing

- Always write in the third person . Never refer to yourself personally, using phrases like “I think…” or “It is my contention…”. Good history essays should adopt the perspective of an informed and objective third party. They should sound rational and factual – not like an individual expressing their opinion.

- Always write in the past tense . An obvious tip for a history essay is to write in the past tense. Always be careful about your use of tense. Watch out for mixed tenses when proofreading your work. One exception to the rule about past tense is when writing about the work of modern historians (for example, “Kershaw writes…” sounds better than “Kershaw wrote…” or “Kershaw has written…”).

- Avoid generalisations . Generalisation is a problem in all essays but it is particularly common in history essays. Generalisation occurs when you form general conclusions from one or more specific examples. In history, this most commonly occurs when students study the experiences of a particular group, then assume their experiences applied to a much larger group – for example, “All the peasants were outraged”, “Women rallied to oppose conscription” or “Germans supported the Nazi Party”. Both history and human society, however, are never this clear cut or simple. Always try to avoid generalisation and be on the lookout for generalised statements when proofreading.

- Write short, sharp and punchy . Good writers vary their sentence length but as a rule of thumb, most of your sentences should be short and punchy. The longer a sentence becomes, the greater the risk of it becoming long-winded or confusing. Long sentences can easily become disjointed, confused or rambling. Try not to overuse long sentences and pay close attention to sentence length when proofreading.

- Write in an active voice . In history writing, the active voice is preferable to the passive voice. In the active voice, the subject completes the action (e.g. “Hitler [the subject] initiated the Beer Hall putsch [the action] to seize control of the Bavarian government”). In the passive voice, the action is completed by the subject (“The Beer Hall putsch [the action] was initiated by Hitler [the subject] to seize control of the Bavarian government”). The active voice also helps prevent sentences from becoming long, wordy and unclear.

You may also find our page on writing for history useful.

Citation information Title : ‘Writing a history essay’ Authors : Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson Publisher : Alpha History URL : https://alphahistory.com/writing-a-history-essay/ Date published : April 13, 2020 Date updated : December 20, 2022 Date accessed : Today’s date Copyright : The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a History Essay

Last Updated: December 27, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA . Emily Listmann is a Private Tutor and Life Coach in Santa Cruz, California. In 2018, she founded Mindful & Well, a natural healing and wellness coaching service. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. Emily also received her Wellness Coach Certificate from Cornell University and completed the Mindfulness Training by Mindful Schools. There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 244,617 times.

Writing a history essay requires you to include a lot of details and historical information within a given number of words or required pages. It's important to provide all the needed information, but also to present it in a cohesive, intelligent way. Know how to write a history essay that demonstrates your writing skills and your understanding of the material.

Preparing to Write Your Essay

- The key words will often need to be defined at the start of your essay, and will serve as its boundaries. [2] X Research source

- For example, if the question was "To what extent was the First World War a Total War?", the key terms are "First World War", and "Total War".

- Do this before you begin conducting your research to ensure that your reading is closely focussed to the question and you don't waste time.

- Explain: provide an explanation of why something happened or didn't happen.

- Interpret: analyse information within a larger framework to contextualise it.

- Evaluate: present and support a value-judgement.

- Argue: take a clear position on a debate and justify it. [3] X Research source

- Your thesis statement should clearly address the essay prompt and provide supporting arguments. These supporting arguments will become body paragraphs in your essay, where you’ll elaborate and provide concrete evidence. [4] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Your argument may change or become more nuanced as your write your essay, but having a clear thesis statement which you can refer back to is very helpful.

- For example, your summary could be something like "The First World War was a 'total war' because civilian populations were mobilized both in the battlefield and on the home front".

- Pick out some key quotes that make your argument precisely and persuasively. [5] X Research source

- When writing your plan, you should already be thinking about how your essay will flow, and how each point will connect together.

Doing Your Research

- Primary source material refers to any texts, films, pictures, or any other kind of evidence that was produced in the historical period, or by someone who participated in the events of the period, that you are writing about.

- Secondary material is the work by historians or other writers analysing events in the past. The body of historical work on a period or event is known as the historiography.

- It is not unusual to write a literature review or historiographical essay which does not directly draw on primary material.

- Typically a research essay would need significant primary material.

- Start with the core texts in your reading list or course bibliography. Your teacher will have carefully selected these so you should start there.

- Look in footnotes and bibliographies. When you are reading be sure to pay attention to the footnotes and bibliographies which can guide you to further sources a give you a clear picture of the important texts.

- Use the library. If you have access to a library at your school or college, be sure to make the most of it. Search online catalogues and speak to librarians.

- Access online journal databases. If you are in college it is likely that you will have access to academic journals online. These are an excellent and easy to navigate resources.

- Use online sources with discretion. Try using free scholarly databases, like Google Scholar, which offer quality academic sources, but avoid using the non-trustworthy websites that come up when you simply search your topic online.

- Avoid using crowd-sourced sites like Wikipedia as sources. However, you can look at the sources cited on a Wikipedia page and use them instead, if they seem credible.

- Who is the author? Is it written by an academic with a position at a University? Search for the author online.

- Who is the publisher? Is the book published by an established academic press? Look in the cover to check the publisher, if it is published by a University Press that is a good sign.

- If it's an article, where is published? If you are using an article check that it has been published in an academic journal. [8] X Research source

- If the article is online, what is the URL? Government sources with .gov addresses are good sources, as are .edu sites.

- Ask yourself why the author is making this argument. Evaluate the text by placing it into a broader intellectual context. Is it part of a certain tradition in historiography? Is it a response to a particular idea?

- Consider where there are weaknesses and limitations to the argument. Always keep a critical mindset and try to identify areas where you think the argument is overly stretched or the evidence doesn't match the author's claims. [9] X Research source

- Label all your notes with the page numbers and precise bibliographic information on the source.

- If you have a quote but can't remember where you found it, imagine trying to skip back through everything you have read to find that one line.

- If you use something and don't reference it fully you risk plagiarism. [10] X Research source

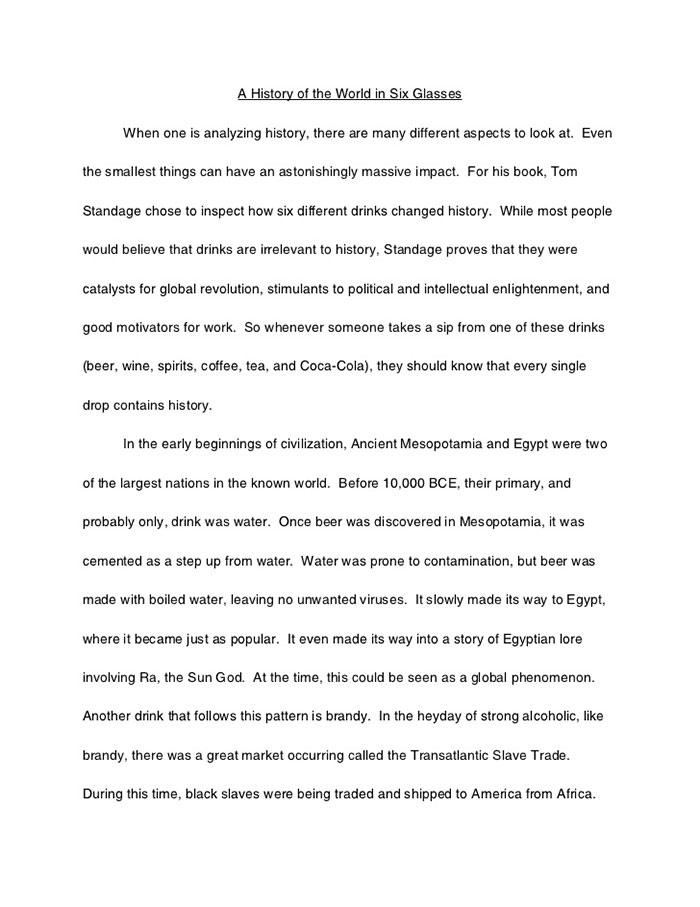

Writing the Introduction

- For example you could start by saying "In the First World War new technologies and the mass mobilization of populations meant that the war was not fought solely by standing armies".

- This first sentences introduces the topic of your essay in a broad way which you can start focus to in on more.

- This will lead to an outline of the structure of your essay and your argument.

- Here you will explain the particular approach you have taken to the essay.

- For example, if you are using case studies you should explain this and give a brief overview of which case studies you will be using and why.

Writing the Essay

- Try to include a sentence that concludes each paragraph and links it to the next paragraph.

- When you are organising your essay think of each paragraph as addressing one element of the essay question.

- Keeping a close focus like this will also help you avoid drifting away from the topic of the essay and will encourage you to write in precise and concise prose.

- Don't forget to write in the past tense when referring to something that has already happened.

- Don't drop a quote from a primary source into your prose without introducing it and discussing it, and try to avoid long quotations. Use only the quotes that best illustrate your point.

- If you are referring to a secondary source, you can usually summarise in your own words rather than quoting directly.

- Be sure to fully cite anything you refer to, including if you do not quote it directly.

- Think about the first and last sentence in every paragraph and how they connect to the previous and next paragraph.

- Try to avoid beginning paragraphs with simple phrases that make your essay appear more like a list. For example, limit your use of words like: "Additionally", "Moreover", "Furthermore".

- Give an indication of where your essay is going and how you are building on what you have already said. [15] X Research source

- Briefly outline the implications of your argument and it's significance in relation to the historiography, but avoid grand sweeping statements. [16] X Research source

- A conclusion also provides the opportunity to point to areas beyond the scope of your essay where the research could be developed in the future.

Proofreading and Evaluating Your Essay

- Try to cut down any overly long sentences or run-on sentences. Instead, try to write clear and accurate prose and avoid unnecessary words.

- Concentrate on developing a clear, simple and highly readable prose style first before you think about developing your writing further. [17] X Research source

- Reading your essay out load can help you get a clearer picture of awkward phrasing and overly long sentences. [18] X Research source

- When you read through your essay look at each paragraph and ask yourself, "what point this paragraph is making".

- You might have produced a nice piece of narrative writing, but if you are not directly answering the question it is not going to help your grade.

- A bibliography will typically have primary sources first, followed by secondary sources. [19] X Research source

- Double and triple check that you have included all the necessary references in the text. If you forgot to include a reference you risk being reported for plagiarism.

Sample Essay

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.historytoday.com/robert-pearce/how-write-good-history-essay

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/writing-a-good-history-paper

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/thesis_statement_tips.html

- ↑ http://history.rutgers.edu/component/content/article?id=106:writing-historical-essays-a-guide-for-undergraduates

- ↑ https://guides.lib.uw.edu/c.php?g=344285&p=2580599

- ↑ http://www.hamilton.edu/documents/writing-center/WritingGoodHistoryPaper.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/

- ↑ https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/hppi/publications/Writing-History-Essays.pdf

About This Article

To write a history essay, read the essay question carefully and use source materials to research the topic, taking thorough notes as you go. Next, formulate a thesis statement that summarizes your key argument in 1-2 concise sentences and create a structured outline to help you stay on topic. Open with a strong introduction that introduces your thesis, present your argument, and back it up with sourced material. Then, end with a succinct conclusion that restates and summarizes your position! For more tips on creating a thesis statement, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Lea Fernandez

Nov 23, 2017

Did this article help you?

Matthew Sayers

Mar 31, 2019

Millie Jenkerinx

Nov 11, 2017

Oct 18, 2019

Shannon Harper

Mar 9, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

How to Write a History Essay with Outline, Tips, Examples and More

Samuel Gorbold

Before we get into how to write a history essay, let's first understand what makes one good. Different people might have different ideas, but there are some basic rules that can help you do well in your studies. In this guide, we won't get into any fancy theories. Instead, we'll give you straightforward tips to help you with historical writing. So, if you're ready to sharpen your writing skills, let our history essay writing service explore how to craft an exceptional paper.

What is a History Essay?

A history essay is an academic assignment where we explore and analyze historical events from the past. We dig into historical stories, figures, and ideas to understand their importance and how they've shaped our world today. History essay writing involves researching, thinking critically, and presenting arguments based on evidence.

Moreover, history papers foster the development of writing proficiency and the ability to communicate complex ideas effectively. They also encourage students to engage with primary and secondary sources, enhancing their research skills and deepening their understanding of historical methodology. Students can benefit from utilizing essay writers services when faced with challenging assignments. These services provide expert assistance and guidance, ensuring that your history papers meet academic standards and accurately reflect your understanding of the subject matter.

History Essay Outline

.png)

The outline is there to guide you in organizing your thoughts and arguments in your essay about history. With a clear outline, you can explore and explain historical events better. Here's how to make one:

Introduction

- Hook: Start with an attention-grabbing opening sentence or anecdote related to your topic.

- Background Information: Provide context on the historical period, event, or theme you'll be discussing.

- Thesis Statement: Present your main argument or viewpoint, outlining the scope and purpose of your history essay.

Body paragraph 1: Introduction to the Historical Context

- Provide background information on the historical context of your topic.

- Highlight key events, figures, or developments leading up to the main focus of your history essay.

Body paragraphs 2-4 (or more): Main Arguments and Supporting Evidence

- Each paragraph should focus on a specific argument or aspect of your thesis.

- Present evidence from primary and secondary sources to support each argument.

- Analyze the significance of the evidence and its relevance to your history paper thesis.

Counterarguments (optional)

- Address potential counterarguments or alternative perspectives on your topic.

- Refute opposing viewpoints with evidence and logical reasoning.

- Summary of Main Points: Recap the main arguments presented in the body paragraphs.

- Restate Thesis: Reinforce your thesis statement, emphasizing its significance in light of the evidence presented.

- Reflection: Reflect on the broader implications of your arguments for understanding history.

- Closing Thought: End your history paper with a thought-provoking statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

References/bibliography

- List all sources used in your research, formatted according to the citation style required by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include both primary and secondary sources, arranged alphabetically by the author's last name.

Notes (if applicable)

- Include footnotes or endnotes to provide additional explanations, citations, or commentary on specific points within your history essay.

History Essay Format

Adhering to a specific format is crucial for clarity, coherence, and academic integrity. Here are the key components of a typical history essay format:

Font and Size

- Use a legible font such as Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri.

- The recommended font size is usually 12 points. However, check your instructor's guidelines, as they may specify a different size.

- Set 1-inch margins on all sides of the page.

- Double-space the entire essay, including the title, headings, body paragraphs, and references.

- Avoid extra spacing between paragraphs unless specified otherwise.

- Align text to the left margin; avoid justifying the text or using a centered alignment.

Title Page (if required):

- If your instructor requires a title page, include the essay title, your name, the course title, the instructor's name, and the date.

- Center-align this information vertically and horizontally on the page.

- Include a header on each page (excluding the title page if applicable) with your last name and the page number, flush right.

- Some instructors may require a shortened title in the header, usually in all capital letters.

- Center-align the essay title at the top of the first page (if a title page is not required).

- Use standard capitalization (capitalize the first letter of each major word).

- Avoid underlining, italicizing, or bolding the title unless necessary for emphasis.

Paragraph Indentation:

- Indent the first line of each paragraph by 0.5 inches or use the tab key.

- Do not insert extra spaces between paragraphs unless instructed otherwise.

Citations and References:

- Follow the citation style specified by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include in-text citations whenever you use information or ideas from external sources.

- Provide a bibliography or list of references at the end of your history essay, formatted according to the citation style guidelines.

- Typically, history essays range from 1000 to 2500 words, but this can vary depending on the assignment.

How to Write a History Essay?

Historical writing can be an exciting journey through time, but it requires careful planning and organization. In this section, we'll break down the process into simple steps to help you craft a compelling and well-structured history paper.

Analyze the Question

Before diving headfirst into writing, take a moment to dissect the essay question. Read it carefully, and then read it again. You want to get to the core of what it's asking. Look out for keywords that indicate what aspects of the topic you need to focus on. If you're unsure about anything, don't hesitate to ask your instructor for clarification. Remember, understanding how to start a history essay is half the battle won!

Now, let's break this step down:

- Read the question carefully and identify keywords or phrases.

- Consider what the question is asking you to do – are you being asked to analyze, compare, contrast, or evaluate?

- Pay attention to any specific instructions or requirements provided in the question.

- Take note of the time period or historical events mentioned in the question – this will give you a clue about the scope of your history essay.

Develop a Strategy

With a clear understanding of the essay question, it's time to map out your approach. Here's how to develop your historical writing strategy:

- Brainstorm ideas : Take a moment to jot down any initial thoughts or ideas that come to mind in response to the history paper question. This can help you generate a list of potential arguments, themes, or points you want to explore in your history essay.

- Create an outline : Once you have a list of ideas, organize them into a logical structure. Start with a clear introduction that introduces your topic and presents your thesis statement – the main argument or point you'll be making in your history essay. Then, outline the key points or arguments you'll be discussing in each paragraph of the body, making sure they relate back to your thesis. Finally, plan a conclusion that summarizes your main points and reinforces your history paper thesis.

- Research : Before diving into writing, gather evidence to support your arguments. Use reputable sources such as books, academic journals, and primary documents to gather historical evidence and examples. Take notes as you research, making sure to record the source of each piece of information for proper citation later on.

- Consider counterarguments : Anticipate potential counterarguments to your history paper thesis and think about how you'll address them in your essay. Acknowledging opposing viewpoints and refuting them strengthens your argument and demonstrates critical thinking.

- Set realistic goals : Be realistic about the scope of your history essay and the time you have available to complete it. Break down your writing process into manageable tasks, such as researching, drafting, and revising, and set deadlines for each stage to stay on track.

Start Your Research

Now that you've grasped the history essay topic and outlined your approach, it's time to dive into research. Here's how to start:

- Ask questions : What do you need to know? What are the key points to explore further? Write down your inquiries to guide your research.

- Explore diverse sources : Look beyond textbooks. Check academic journals, reliable websites, and primary sources like documents or artifacts.

- Consider perspectives : Think about different viewpoints on your topic. How have historians analyzed it? Are there controversies or differing interpretations?

- Take organized notes : Summarize key points, jot down quotes, and record your thoughts and questions. Stay organized using spreadsheets or note-taking apps.

- Evaluate sources : Consider the credibility and bias of each source. Are they peer-reviewed? Do they represent a particular viewpoint?

Establish a Viewpoint

By establishing a clear viewpoint and supporting arguments, you'll lay the foundation for your compelling historical writing:

- Review your research : Reflect on the information gathered. What patterns or themes emerge? Which perspectives resonate with you?

- Formulate a thesis statement : Based on your research, develop a clear and concise thesis that states your argument or interpretation of the topic.

- Consider counterarguments : Anticipate objections to your history paper thesis. Are there alternative viewpoints or evidence that you need to address?

- Craft supporting arguments : Outline the main points that support your thesis. Use evidence from your research to strengthen your arguments.

- Stay flexible : Be open to adjusting your viewpoint as you continue writing and researching. New information may challenge or refine your initial ideas.

Structure Your Essay

Now that you've delved into the depths of researching historical events and established your viewpoint, it's time to craft the skeleton of your essay: its structure. Think of your history essay outline as constructing a sturdy bridge between your ideas and your reader's understanding. How will you lead them from point A to point Z? Will you follow a chronological path through history or perhaps dissect themes that span across time periods?

And don't forget about the importance of your introduction and conclusion—are they framing your narrative effectively, enticing your audience to read your paper, and leaving them with lingering thoughts long after they've turned the final page? So, as you lay the bricks of your history essay's architecture, ask yourself: How can I best lead my audience through the maze of time and thought, leaving them enlightened and enriched on the other side?

Create an Engaging Introduction

Creating an engaging introduction is crucial for capturing your reader's interest right from the start. But how do you do it? Think about what makes your topic fascinating. Is there a surprising fact or a compelling story you can share? Maybe you could ask a thought-provoking question that gets people thinking. Consider why your topic matters—what lessons can we learn from history?

Also, remember to explain what your history essay will be about and why it's worth reading. What will grab your reader's attention and make them want to learn more? How can you make your essay relevant and intriguing right from the beginning?

Develop Coherent Paragraphs

Once you've established your introduction, the next step is to develop coherent paragraphs that effectively communicate your ideas. Each paragraph should focus on one main point or argument, supported by evidence or examples from your research. Start by introducing the main idea in a topic sentence, then provide supporting details or evidence to reinforce your point.

Make sure to use transition words and phrases to guide your reader smoothly from one idea to the next, creating a logical flow throughout your history essay. Additionally, consider the organization of your paragraphs—is there a clear progression of ideas that builds upon each other? Are your paragraphs unified around a central theme or argument?

Conclude Effectively

Concluding your history essay effectively is just as important as starting it off strong. In your conclusion, you want to wrap up your main points while leaving a lasting impression on your reader. Begin by summarizing the key points you've made throughout your history essay, reminding your reader of the main arguments and insights you've presented.

Then, consider the broader significance of your topic—what implications does it have for our understanding of history or for the world today? You might also want to reflect on any unanswered questions or areas for further exploration. Finally, end with a thought-provoking statement or a call to action that encourages your reader to continue thinking about the topic long after they've finished reading.

Reference Your Sources

Referencing your sources is essential for maintaining the integrity of your history essay and giving credit to the scholars and researchers who have contributed to your understanding of the topic. Depending on the citation style required (such as MLA, APA, or Chicago), you'll need to format your references accordingly. Start by compiling a list of all the sources you've consulted, including books, articles, websites, and any other materials used in your research.

Then, as you write your history essay, make sure to properly cite each source whenever you use information or ideas that are not your own. This includes direct quotations, paraphrases, and summaries. Remember to include all necessary information for each source, such as author names, publication dates, and page numbers, as required by your chosen citation style.

Review and Ask for Advice

As you near the completion of your history essay writing, it's crucial to take a step back and review your work with a critical eye. Reflect on the clarity and coherence of your arguments—are they logically organized and effectively supported by evidence? Consider the strength of your introduction and conclusion—do they effectively capture the reader's attention and leave a lasting impression? Take the time to carefully proofread your history essay for any grammatical errors or typos that may detract from your overall message.

Furthermore, seeking advice from peers, mentors, or instructors can provide valuable insights and help identify areas for improvement. Consider sharing your essay with someone whose feedback you trust and respect, and be open to constructive criticism. Ask specific questions about areas you're unsure about or where you feel your history essay may be lacking. If you need further assistance, don't hesitate to reach out and ask for help. You can even consider utilizing services that offer to write a discussion post for me , where you can engage in meaningful conversations with others about your essay topic and receive additional guidance and support.

History Essay Example

In this section, we offer an example of a history essay examining the impact of the Industrial Revolution on society. This essay demonstrates how historical analysis and critical thinking are applied in academic writing. By exploring this specific event, you can observe how historical evidence is used to build a cohesive argument and draw meaningful conclusions.

FAQs about History Essay Writing

How to write a history essay introduction, how to write a conclusion for a history essay, how to write a good history essay.

Samuel Gorbold , a seasoned professor with over 30 years of experience, guides students across disciplines such as English, psychology, political science, and many more. Together with EssayHub, he is dedicated to enhancing student understanding and success through comprehensive academic support.

- Plagiarism Report

- Unlimited Revisions

- 24/7 Support

A guide to writing history essays

This guide has been prepared for students at all undergraduate university levels. Some points are specifically aimed at 100-level students, and may seem basic to those in upper levels. Similarly, some of the advice is aimed at upper-level students, and new arrivals should not be put off by it.

The key point is that learning to write good essays is a long process. We hope that students will refer to this guide frequently, whatever their level of study.

Why do history students write essays?

Essays are an essential educational tool in disciplines like history because they help you to develop your research skills, critical thinking, and writing abilities. The best essays are based on strong research, in-depth analysis, and are logically structured and well written.

An essay should answer a question with a clear, persuasive argument. In a history essay, this will inevitably involve a degree of narrative (storytelling), but this should be kept to the minimum necessary to support the argument – do your best to avoid the trap of substituting narrative for analytical argument. Instead, focus on the key elements of your argument, making sure they are well supported by evidence. As a historian, this evidence will come from your sources, whether primary and secondary.

The following guide is designed to help you research and write your essays, and you will almost certainly earn better grades if you can follow this advice. You should also look at the essay-marking criteria set out in your course guide, as this will give you a more specific idea of what the person marking your work is looking for.

Where to start

First, take time to understand the question. Underline the key words and consider very carefully what you need to do to provide a persuasive answer. For example, if the question asks you to compare and contrast two or more things, you need to do more than define these things – what are the similarities and differences between them? If a question asks you to 'assess' or 'explore', it is calling for you to weigh up an issue by considering the evidence put forward by scholars, then present your argument on the matter in hand.

A history essay must be based on research. If the topic is covered by lectures, you might begin with lecture and tutorial notes and readings. However, the lecturer does not want you simply to echo or reproduce the lecture content or point of view, nor use their lectures as sources in your footnotes. They want you to develop your own argument. To do this you will need to look closely at secondary sources, such as academic books and journal articles, to find out what other scholars have written about the topic. Often your lecturer will have suggested some key texts, and these are usually listed near the essay questions in your course guide. But you should not rely solely on these suggestions.

Tip : Start the research with more general works to get an overview of your topic, then move on to look at more specialised work.

Crafting a strong essay

Before you begin writing, make an essay plan. Identify the two-to-four key points you want to make. Organize your ideas into an argument which flows logically and coherently. Work out which examples you will use to make the strongest case. You may need to use an initial paragraph (or two) to bring in some context or to define key terms and events, or provide brief identifying detail about key people – but avoid simply telling the story.

An essay is really a series of paragraphs that advance an argument and build towards your conclusion. Each paragraph should focus on one central idea. Introduce this idea at the start of the paragraph with a 'topic sentence', then expand on it with evidence or examples from your research. Some paragraphs should finish with a concluding sentence that reiterates a main point or links your argument back to the essay question.

A good length for a paragraph is 150-200 words. When you want to move to a new idea or angle, start a new paragraph. While each paragraph deals with its own idea, paragraphs should flow logically, and work together as a greater whole. Try using linking phrases at the start of your paragraphs, such as 'An additional factor that explains', 'Further', or 'Similarly'.

We discourage using subheadings for a history essay (unless they are over 5000 words in length). Instead, throughout your essay use 'signposts'. This means clearly explaining what your essay will cover, how an example demonstrates your point, or reiterating what a particular section has added to your overall argument.

Remember that a history essay isn't necessarily about getting the 'right' answer – it's about putting forward a strong case that is well supported by evidence from academic sources. You don't have to cover everything – focus on your key points.

In your introduction or opening paragraph you could indicate that while there are a number of other explanations or factors that apply to your topic, you have chosen to focus on the selected ones (and say why). This demonstrates to your marker that while your argument will focus on selected elements, you do understand the bigger picture.

The classic sections of an essay

Introduction.

- Establishes what your argument will be, and outlines how the essay will develop it

- A good formula to follow is to lay out about 3 key reasons that support the answer you plan to give (these points will provide a road-map for your essay and will become the ideas behind each paragraph)

- If you are focusing on selected aspects of a topic or particular sources and case studies, you should state that in your introduction

- Define any key terms that are essential to your argument

- Keep your introduction relatively concise – aim for about 10% of the word count

- Consists of a series of paragraphs that systematically develop the argument outlined in your introduction

- Each paragraph should focus on one central idea, building towards your conclusion

- Paragraphs should flow logically. Tie them together with 'bridge' sentences – e.g. you might use a word or words from the end of the previous paragraph and build it into the opening sentence of the next, to form a bridge

- Also be sure to link each paragraph to the question/topic/argument in some way (e.g. use a key word from the question or your introductory points) so the reader does not lose the thread of your argument

- Ties up the main points of your discussion

- Should link back to the essay question, and clearly summarise your answer to that question

- May draw out or reflect on any greater themes or observations, but you should avoid introducing new material

- If you have suggested several explanations, evaluate which one is strongest

Using scholarly sources: books, journal articles, chapters from edited volumes

Try to read critically: do not take what you read as the only truth, and try to weigh up the arguments presented by scholars. Read several books, chapters, or articles, so that you understand the historical debates about your topic before deciding which viewpoint you support. The best sources for your history essays are those written by experts, and may include books, journal articles, and chapters in edited volumes. The marking criteria in your course guide may state a minimum number of academic sources you should consult when writing your essay. A good essay considers a range of evidence, so aim to use more than this minimum number of sources.

Tip : Pick one of the books or journal articles suggested in your course guide and look at the author's first few footnotes – these will direct you to other prominent sources on this topic.

Don't overlook journal articles as a source. They contain the most in-depth research on a particular topic. Often the first pages will summarise the prior research into this topic, so articles can be a good way to familiarise yourself with what else has 'been done'.

Edited volumes can also be a useful source. These are books on a particular theme, topic or question, with each chapter written by a different expert.

One way to assess the reliability of a source is to check the footnotes or endnotes. When the author makes a claim, is this supported by primary or secondary sources? If there are very few footnotes, then this may not be a credible scholarly source. Also check the date of publication, and prioritise more recent scholarship. Aim to use a variety of sources, but focus most of your attention on academic books and journal articles.

Paraphrasing and quotations

A good essay is about your ability to interpret and analyse sources, and to establish your own informed opinion with a persuasive argument that uses sources as supporting evidence. You should express most of your ideas and arguments in your own words. Cutting and pasting together the words of other scholars, or simply changing a few words in quotations taken from the work of others, will prevent you from getting a good grade, and may be regarded as academic dishonesty (see more below).

Direct quotations can be useful tools if they provide authority and colour. For maximum effect though, use direct quotations sparingly – where possible, paraphrase most material into your own words. Save direct quotations for phrases that are interesting, contentious, or especially well-phrased.

A good writing practice is to introduce and follow up every direct quotation you use with one or two sentences of your own words, clearly explaining the relevance of the quote, and putting it in context with the rest of your paragraph. Tell the reader who you are quoting, why this quote is here, and what it demonstrates. Avoid simply plonking a quotation into the middle of your own prose. This can be quite off-putting for a reader.

- Only include punctuation in your quote if it was in the original text. Otherwise, punctuation should come after the quotation marks. If you cut out words from a quotation, put in three dots (an ellipsis [ . . .]) to indicate where material has been cut

- If your quote is longer than 50 words, it should be indented and does not need quotation marks. This is called a block quote (use these sparingly: remember you have a limited word count and it is your analysis that is most significant)

- Quotations should not be italicised

Referencing, plagiarism and Turnitin

When writing essays or assignments, it is very important to acknowledge the sources you have used. You risk the charge of academic dishonesty (or plagiarism) if you copy or paraphrase words written by another person without providing a proper acknowledgment (a 'reference'). In your essay, whenever you refer to ideas from elsewhere, statistics, direct quotations, or information from primary source material, you must give details of where this information has come from in footnotes and a bibliography.

Your assignment may be checked through Turnitin, a type of plagiarism-detecting software which checks assignments for evidence of copied material. If you have used a wide variety of primary and secondary sources, you may receive a high Turnitin percentage score. This is nothing to be alarmed about if you have referenced those sources. Any matches with other written material that are not referenced may be interpreted as plagiarism – for which there are penalties. You can find full information about all of this in the History Programme's Quick Guide Referencing Guide contained in all course booklets.

Final suggestions

Remember that the easier it is to read your essay, the more likely you are to get full credit for your ideas and work. If the person marking your work has difficulty reading it, either because of poor writing or poor presentation, they will find it harder to grasp your points. Try reading your work aloud, or to a friend/flatmate. This should expose any issues with flow or structure, which you can then rectify.

Make sure that major and controversial points in your argument are clearly stated and well- supported by evidence and footnotes. Aspire to understand – rather than judge – the past. A historian's job is to think about people, patterns, and events in the context of the time, though you can also reflect on changing perceptions of these over time.

Things to remember

- Write history essays in the past tense

- Generally, avoid sub-headings in your essays

- Avoid using the word 'bias' or 'biased' too freely when discussing your research materials. Almost any text could be said to be 'biased'. Your task is to attempt to explain why an author might argue or interpret the past as they do, and what the potential limitations of their conclusions might be

- Use the passive voice judiciously. Active sentences are better!

- Be cautious about using websites as sources of information. The internet has its uses, particularly for primary sources, but the best sources are academic books and articles. You may use websites maintained by legitimate academic and government authorities, such as those with domain suffixes like .gov .govt .ac or .edu

- Keep an eye on word count – aim to be within 10% of the required length. If your essay is substantially over the limit, revisit your argument and overall structure, and see if you are trying to fit in too much information. If it falls considerably short, look into adding another paragraph or two

- Leave time for a final edit and spell-check, go through your footnotes and bibliography to check that your references are correctly formatted, and don't forget to back up your work as you go!

Other useful strategies and sources

- Student Learning Development , which offers peer support and one-on-one writing advice (located near the central library)

- Harvard College's guide to writing history essays (PDF)

- Harvard College's advice on essay structure

- Victoria University's comprehensive essay writing guide (PDF)

How to Write a History Essay

The analytical essay.

One of the most important skills you must learn in order to succeed in a history classroom is the art of essay writing. Writing an essay is one of the most common tasks assigned to a history student, and often one of the most daunting. However, once you gain the skills and confidence to write a great essay it can also be one of the most fun assignments you have. Essays allow you to engage with the material you have studied and draw your own conclusions. A good essay shows that you have mastered the material at hand and that you are able to engage with it in a new and meaningful way.

The Thesis Statement

The most important thing to remember when writing an analytical essay is that it calls for you to analyze something. That is to say your essay should have a challengeable argument . An argument is a statement which people can disagree about. The goal of your essay is to persuade the reader to support your argument. The best essays will be those which take a strong stance on a topic, and use evidence to support that stance. You should be able to condense your strong stance into one or two concrete sentences called your thesis statement . The thesis of your essay should clearly lay out what you will be arguing for in your essay. Again, a good thesis statement will present your challengeable argument – the thing you are trying to prove.

Here are two examples

Bad Thesis Statement : Johannes Kepler was an important figure in the Scientific Revolution.

Good Thesis Statement : Johannes Kepler’s mathematical evidence supporting the heliocentric model of the universe was instrumental in progressing the scientific revolution because it legitimized the need for scientists to question authority, gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe, and it laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method.

As you can see the first thesis statement is not a challengeable argument. The fact that Johannes Kepler was an important figure is not disputed, and an essay to prove that he was important wouldn’t be effective, and would also be no fun to write (or read.)

The second thesis statement however does make a challengeable argument. It argues that Kepler’s discovery helped to progress the scientific revolution and goes on to explain three reasons why. This thesis statement not only poses a challengeable argument, but also outlines the evidence which will be used to prove the argument. Now the reader knows right away what you will be arguing for, and why you believe the argument is correct.

Note : This type of thesis is called a ‘ three-prong thesis .’ There are other valid ways to set up a thesis statement, but the three prong thesis form is a very straightforward approach which is allows both beginner and advanced essayists the ability to clearly define the structure of their essay.

Writing an Introduction

The introduction is the first part of your essay anyone will read and so it is the most important. People make up their minds about the quality of a paper within the first few lines, so it’s important that you start strong. The introduction of your paper must layout the basic premise behind the paper. It should include any background knowledge essential to understanding your argument that is not directly addressed in your paper. In addition, your introduction should telegraph to a reader what your argument will be, and what topics you will discuss. In order write a good intro, there are a few essential elements which you must have.

First, every good introduction has to have a snappy opening or hook . Your first few lines must be engaging to the reader the same way it’s important to make a good impression with a new classmate. Resist the urge to open your paper with a famous quote. Readers never respond favorably to irrelevant epigraphs. Worse still, is the tired tradition of opening your essay with a definition. If your essay opens with “Webster’s dictionary defines blank as…” then you have some serious editing to do. You should always write your papers as though they are being read by an equally educated individual who is not a member of your class. As such, you should assume they already know the definitions of the key terms you are using, or able to look them up on their own time. Instead, you should try to introduce the topic of your paper in some informal way using a relevant anecdote, rhetorical question, interesting fact or metaphor. Your introduction should start out broadly and so your hook can begin introducing your topic informally. At the same time however, your hook must be relevant enough to lead into the meat of your paper.

Once you have a hook and have begun to introduce your topic, it is important to provide a roadmap for your essay. The roadmap is the portion of your introduction in which you briefly explain to your reader where your essay is going. The clearer your roadmap is the more engaged the reader will be. Generally speaking, you should devote one or two sentences to introducing the main ideas in each of your body paragraphs . By doing this you allow the reader to better understand the direction your essay will take. They will know what each body paragraph will be about and understand right way what your argument is and how plan to prove it.

Finally every introduction must include your thesis statement. As discussed above, our thesis statement should be the specific statement of what you are arguing. Make sure it is as clear as possible. The thesis statement should be at the end of your introduction. When you first begin writing essays, it is usually a good idea to make the thesis statement the final sentence of your introduction, but you can play around with the placement of the components of the introduction as you master the art of essay writing.

Remember, a good introduction should be shaped like a funnel. In the beginning your introduction starts broadly, but as it gets more specific as it goes, eventually culminating in the very specific thesis statement.

The body paragraphs of your essay are the meat of the work. It is in this section that you must do the most writing. All of your sub-arguments and evidence which prove your thesis are contained within the body of your essay. Writing this section can be a daunting task – especially if you are faced with what seems like an enormous expanse of blank pages to fill. Have no fear. Though the essay may seem intimidating to completely finish, practice will make essay writing seem easier, and by following these tips you can ensure the body of your essay impresses your reader.

It helps to consider each individual paragraph as an essay within itself. At the beginning of each new paragraph you should have a topic sentence . The topic sentence explains what the paragraph is about and how it relates to your thesis statement. In this way the topic sentence acts like the introduction to the paragraph. Next you must write the body of the paragraph itself – the facts and evidence which support the topic sentence. Finally, you need a conclusion to the paragraph which explains how what you just wrote about related to the main thesis.

Approaching each body paragraph as its own mini essay makes writing the whole paper seem much less intimidating. By breaking the essay up into smaller portions, it’s much easier to tackle the project as a whole.

Another great way to make essay writing easier is to create an outline. We’ll demonstrate how to do that next. Making a through outline will ensure that you always know where you are going. It makes it much easier to write the whole essay quickly, and you’ll never run into the problem of writers block, because you will always have someplace to go next.

Writing The Outline

Before you begin writing an essay you should always write an outline . Be as through as possible. You know that you will need to create a thesis statement which contains your challengeable argument, so start there. Write down your thesis first on a blank piece of paper. Got it? Good.

Now, think about how you will prove your thesis. What are the sub-arguments? Suppose we take our thesis from earlier about Kepler.

Thesis : Johannes Kepler’s mathematical evidence supporting the heliocentric model of the universe was instrumental in progressing the scientific revolution because it legitimized the need for scientists to question authority, gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe, and it laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method.

What are the sub-arguments here? Well fortunately, because we made our thesis very clear the sub-arguments are easy to find. They are the bolded portions below:

Thesis : Johannes Kepler’s mathematical evidence supporting the heliocentric model of the universe was instrumental in progressing the scientific revolution because it legitimized the need for scientists to question authority , gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe , and it laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method .

Now we know what the sections of our body should cover and argue:

1) Kepler’s evidence legitimized the need for scientists to question authority. 2) Kepler’s evidence gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe 3) Kepler’s evidence laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method.

Note : The structure we are employing here is called the 5 paragraph essay . When you begin writing essays it is a good idea to master this structure first, and then, once you feel comfortable, you can branch out into different forms. You may also pursue a 5 paragraph essay with the body structure: ‘Narration,’ ‘Affirmation,’ ‘Negation,’ etc. In this structure the first paragraph provides background, the second presents your argument, and the third presents a counter argument which you proceed to rebut.

Now that we know what each body paragraph is about, it is time to fill out what information they will contain. Consider what facts can be used to prove the argument of each paragraph. What sources do you have which might justify your claims? Try your best to categorize your knowledge so that it fits into one of the three groups. Once you know what you want to talk about in each paragraph, try to order it either chronologically or thematically. This will help to give your essay a logical flow.

Once finished your outline should look something like this :

1) Introduction : Thesis: Johannes Kepler’s mathematical evidence supporting the heliocentric model of the universe was instrumental in progressing the scientific revolution because it legitimized the need for scientists to question authority, gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe, and it laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method. 2) Body Paragraph 1 : legitimized questioning of authority 2.a) Kepler’s discovery proved that the European understanding of the universe was flawed 2.b) By proving that the European understanding was flawed in one area, Kepler’s work suggested there might be flaws in other areas inspiring scientists in all fields to question authority 3) Body Paragraph 2 : gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe 3.a) Kepler’s discovery was widely read by other scientists who were able to expand on his work to make new discoveries 4) Body Paragraph 3 : laid the groundwork for the scientific method 4.a) Kepler’s discovery relied heavily on mathematical proof rather than feelings, or even observations. This made Kepler’s theory able to hold up under scrutiny. 4.b) The method of Kepler’s work impressed Renaissance thinkers like Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes who saw his work as more legitimate than that which came before it. They then measured other scientific work against Kepler’s method of experimental and mathematical proof. 5) Conclusion : Wrap up your paper and explain its importance.

The final part of your essay is the conclusion . The conclusion is the last part of your essay that anyone will read, so it is important that it is also as strong as the introduction. The conclusion should synthesize you argument into one succinct paragraph. You should reiterate your thesis statement – though in slightly different words – and explain how the thesis was proved. Be sure that your conclusion does not simply summarize your paper, but rather ensure that it enhances it. The best way to do this is by explaining how your whole argument fits together. Show in your conclusion that the examples you picked were not just random, but fit together to tell a compelling story.

The best conclusions will also attempt to answer the question of ‘so what?’ Why did you write this paper? What meaning can be taken from it? Can it teach us something about the world today or does it enhance our knowledge of the past? By relating your paper back to the bigger picture you are able to enhance your work by placing it within the larger discussion. If the reader knows what they have gained from reading your paper, then it will have greater meaning to them.

Subscription Offers

Give a Gift

How To Write a Good History Essay

The former editor of History Review Robert Pearce gives his personal view.

First of all we ought to ask, What constitutes a good history essay? Probably no two people will completely agree, if only for the very good reason that quality is in the eye – and reflects the intellectual state – of the reader. What follows, therefore, skips philosophical issues and instead offers practical advice on how to write an essay that will get top marks.

Witnesses in court promise to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. All history students should swear a similar oath: to answer the question, the whole question and nothing but the question. This is the number one rule. You can write brilliantly and argue a case with a wealth of convincing evidence, but if you are not being relevant then you might as well be tinkling a cymbal. In other words, you have to think very carefully about the question you are asked to answer. Be certain to avoid the besetting sin of those weaker students who, fatally, answer the question the examiners should have set – but unfortunately didn’t. Take your time, look carefully at the wording of the question, and be certain in your own mind that you have thoroughly understood all its terms.

If, for instance, you are asked why Hitler came to power, you must define what this process of coming to power consisted of. Is there any specific event that marks his achievement of power? If you immediately seize on his appointment as Chancellor, think carefully and ask yourself what actual powers this position conferred on him. Was the passing of the Enabling Act more important? And when did the rise to power actually start? Will you need to mention Hitler’s birth and childhood or the hyperinflation of the early 1920s? If you can establish which years are relevant – and consequently which are irrelevant – you will have made a very good start. Then you can decide on the different factors that explain his rise.

Or if you are asked to explain the successes of a particular individual, again avoid writing the first thing that comes into your head. Think about possible successes. In so doing, you will automatically be presented with the problem of defining ‘success’. What does it really mean? Is it the achievement of one’s aims? Is it objective (a matter of fact) or subjective (a matter of opinion)? Do we have to consider short-term and long-term successes? If the person benefits from extraordinary good luck, is that still a success? This grappling with the problem of definition will help you compile an annotated list of successes, and you can then proceed to explain them, tracing their origins and pinpointing how and why they occurred. Is there a key common factor in the successes? If so, this could constitute the central thrust of your answer.

Save 35% with a student subscription to History Today

The key word in the above paragraphs is think . This should be distinguished from remembering, daydreaming and idly speculating. Thinking is rarely a pleasant undertaking, and most of us contrive to avoid it most of the time. But unfortunately there’s no substitute if you want to get the top grade. So think as hard as you can about the meaning of the question, about the issues it raises and the ways you can answer it. You have to think and think hard – and then you should think again, trying to find loopholes in your reasoning. Eventually you will almost certainly become confused. Don’t worry: confusion is often a necessary stage in the achievement of clarity. If you get totally confused, take a break. When you return to the question, it may be that the problems have resolved themselves. If not, give yourself more time. You may well find that decent ideas simply pop into your conscious mind at unexpected times.

You need to think for yourself and come up with a ‘bright idea’ to write a good history essay. You can of course follow the herd and repeat the interpretation given in your textbook. But there are problems here. First, what is to distinguish your work from that of everybody else? Second, it’s very unlikely that your school text has grappled with the precise question you have been set.

The advice above is relevant to coursework essays. It’s different in exams, where time is limited. But even here, you should take time out to do some thinking. Examiners look for quality rather than quantity, and brevity makes relevance doubly important. If you get into the habit of thinking about the key issues in your course, rather than just absorbing whatever you are told or read, you will probably find you’ve already considered whatever issues examiners pinpoint in exams.

The Vital First Paragraph

Every part of an essay is important, but the first paragraph is vital. This is the first chance you have to impress – or depress – an examiner, and first impressions are often decisive. You might therefore try to write an eye-catching first sentence. (‘Start with an earthquake and work up to a climax,’ counselled the film-maker Cecil B. De Mille.) More important is that you demonstrate your understanding of the question set. Here you give your carefully thought out definitions of the key terms, and here you establish the relevant time-frame and issues – in other words, the parameters of the question. Also, you divide the overall question into more manageable sub-divisions, or smaller questions, on each of which you will subsequently write a paragraph. You formulate an argument, or perhaps voice alternative lines of argument, that you will substantiate later in the essay. Hence the first paragraph – or perhaps you might spread this opening section over two paragraphs – is the key to a good essay.

On reading a good first paragraph, examiners will be profoundly reassured that its author is on the right lines, being relevant, analytical and rigorous. They will probably breathe a sign of relief that here is one student at least who is avoiding the two common pitfalls. The first is to ignore the question altogether. The second is to write a narrative of events – often beginning with the birth of an individual – with a half-hearted attempt at answering the question in the final paragraph.

Middle Paragraphs

Philip Larkin once said that the modern novel consists of a beginning, a muddle and an end. The same is, alas, all too true of many history essays. But if you’ve written a good opening section, in which you’ve divided the overall question into separate and manageable areas, your essay will not be muddled; it will be coherent.

It should be obvious, from your middle paragraphs, what question you are answering. Indeed it’s a good test of an essay that the reader should be able to guess the question even if the title is covered up. So consider starting each middle paragraph will a generalisation relevant to the question. Then you can develop this idea and substantiate it with evidence. You must give a judicious selection of evidence (i.e. facts and quotations) to support the argument you are making. You only have a limited amount of space or time, so think about how much detail to give. Relatively unimportant background issues can be summarised with a broad brush; your most important areas need greater embellishment. (Do not be one of those misguided candidates who, unaccountably, ‘go to town’ on peripheral areas and gloss over crucial ones.)

The regulations often specify that, in the A2 year, students should be familiar with the main interpretations of historians. Do not ignore this advice. On the other hand, do not take historiography to extremes, so that the past itself is virtually ignored. In particular, never fall into the trap of thinking that all you need are sets of historians’ opinions. Quite often in essays students give a generalisation and back it up with the opinion of an historian – and since they have formulated the generalisation from the opinion, the argument is entirely circular, and therefore meaningless and unconvincing. It also fatuously presupposes that historians are infallible and omniscient gods. Unless you give real evidence to back up your view – as historians do – a generalisation is simply an assertion. Middle paragraphs are the place for the real substance of an essay, and you neglect this at your peril.

Final Paragraph

If you’ve been arguing a case in the body of an essay, you should hammer home that case in the final paragraph. If you’ve been examining several alternative propositions, now is the time to say which one is correct. In the middle paragraph you are akin to a barrister arguing a case. Now, in the final paragraph, you are the judge summing up and pronouncing the verdict.

It’s as well to keep in mind what you should not be doing. Do not introduce lots of fresh evidence at this stage, though you can certainly introduce the odd extra fact that clinches your case. Nor should you go on to the ‘next’ issue. If your question is about Hitler coming to power, you should not end by giving a summary of what he did once in power. Such an irrelevant ending will fail to win marks. Remember the point about answering ‘nothing but the question’? On the other hand, it may be that some of the things Hitler did after coming to power shed valuable light on why he came to power in the first place. If you can argue this convincingly, all well and good; but don’t expect the examiner to puzzle out relevance. Examiners are not expected to think; you must make your material explicitly relevant.

Final Thoughts

A good essay, especially one that seems to have been effortlessly composed, has often been revised several times; and the best students are those who are most selfcritical. Get into the habit of criticising your own first drafts, and never be satisfied with second-best efforts. Also, take account of the feedback you get from teachers. Don’t just look at the mark your essay gets; read the comments carefully. If teachers don’t advise how to do even better next time, they are not doing their job properly.