Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples

Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples

Published on June 20, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

When you start planning a research project, developing research questions and creating a research design , you will have to make various decisions about the type of research you want to do.

There are many ways to categorize different types of research. The words you use to describe your research depend on your discipline and field. In general, though, the form your research design takes will be shaped by:

- The type of knowledge you aim to produce

- The type of data you will collect and analyze

- The sampling methods , timescale and location of the research

This article takes a look at some common distinctions made between different types of research and outlines the key differences between them.

Table of contents

Types of research aims, types of research data, types of sampling, timescale, and location, other interesting articles.

The first thing to consider is what kind of knowledge your research aims to contribute.

| Type of research | What’s the difference? | What to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Basic vs. applied | Basic research aims to , while applied research aims to . | Do you want to expand scientific understanding or solve a practical problem? |

| vs. | Exploratory research aims to , while explanatory research aims to . | How much is already known about your research problem? Are you conducting initial research on a newly-identified issue, or seeking precise conclusions about an established issue? |

| aims to , while aims to . | Is there already some theory on your research problem that you can use to develop , or do you want to propose new theories based on your findings? |

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The next thing to consider is what type of data you will collect. Each kind of data is associated with a range of specific research methods and procedures.

| Type of research | What’s the difference? | What to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Primary research vs secondary research | Primary data is (e.g., through or ), while secondary data (e.g., in government or scientific publications). | How much data is already available on your topic? Do you want to collect original data or analyze existing data (e.g., through a )? |

| , while . | Is your research more concerned with measuring something or interpreting something? You can also create a research design that has elements of both. | |

| vs | Descriptive research gathers data , while experimental research . | Do you want to identify characteristics, patterns and or test causal relationships between ? |

Finally, you have to consider three closely related questions: how will you select the subjects or participants of the research? When and how often will you collect data from your subjects? And where will the research take place?

Keep in mind that the methods that you choose bring with them different risk factors and types of research bias . Biases aren’t completely avoidable, but can heavily impact the validity and reliability of your findings if left unchecked.

| Type of research | What’s the difference? | What to consider |

|---|---|---|

| allows you to , while allows you to draw conclusions . | Do you want to produce knowledge that applies to many contexts or detailed knowledge about a specific context (e.g. in a )? | |

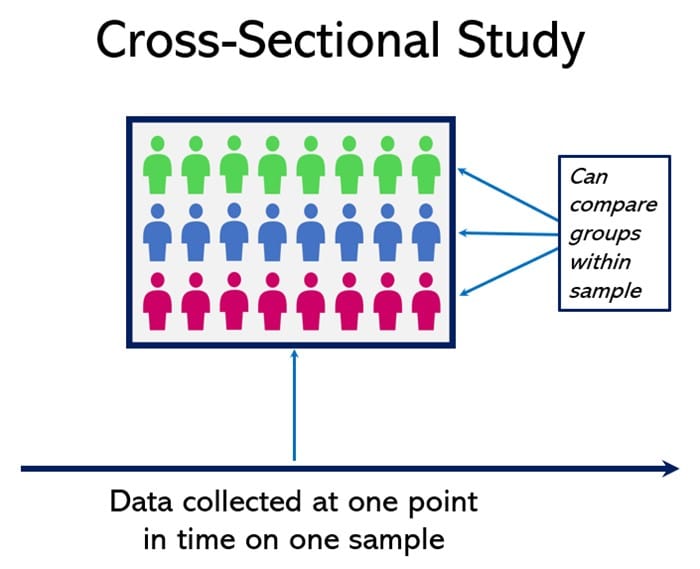

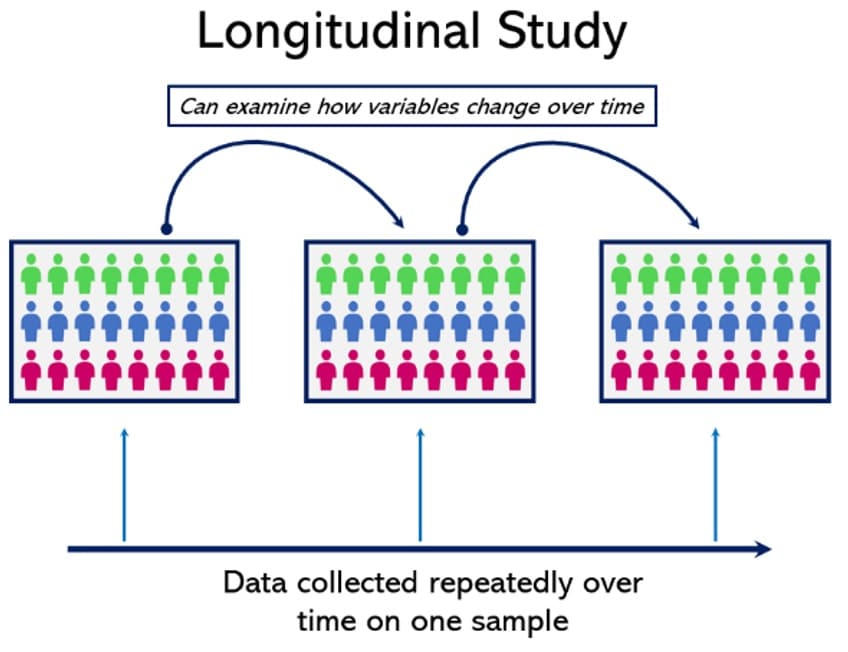

| vs | Cross-sectional studies , while longitudinal studies . | Is your research question focused on understanding the current situation or tracking changes over time? |

| Field research vs laboratory research | Field research takes place in , while laboratory research takes place in . | Do you want to find out how something occurs in the real world or draw firm conclusions about cause and effect? Laboratory experiments have higher but lower . |

| Fixed design vs flexible design | In a fixed research design the subjects, timescale and location are begins, while in a flexible design these aspects may . | Do you want to test hypotheses and establish generalizable facts, or explore concepts and develop understanding? For measuring, testing and making generalizations, a fixed research design has higher . |

Choosing between all these different research types is part of the process of creating your research design , which determines exactly how your research will be conducted. But the type of research is only the first step: next, you have to make more concrete decisions about your research methods and the details of the study.

Read more about creating a research design

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/types-of-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a research design | types, guide & examples, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Research Design 101

Everything You Need To Get Started (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2023

Navigating the world of research can be daunting, especially if you’re a first-time researcher. One concept you’re bound to run into fairly early in your research journey is that of “ research design ”. Here, we’ll guide you through the basics using practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Research Design 101

What is research design.

- Research design types for quantitative studies

- Video explainer : quantitative research design

- Research design types for qualitative studies

- Video explainer : qualitative research design

- How to choose a research design

- Key takeaways

Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project , from its conception to the final data analysis. A good research design serves as the blueprint for how you, as the researcher, will collect and analyse data while ensuring consistency, reliability and validity throughout your study.

Understanding different types of research designs is essential as helps ensure that your approach is suitable given your research aims, objectives and questions , as well as the resources you have available to you. Without a clear big-picture view of how you’ll design your research, you run the risk of potentially making misaligned choices in terms of your methodology – especially your sampling , data collection and data analysis decisions.

The problem with defining research design…

One of the reasons students struggle with a clear definition of research design is because the term is used very loosely across the internet, and even within academia.

Some sources claim that the three research design types are qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods , which isn’t quite accurate (these just refer to the type of data that you’ll collect and analyse). Other sources state that research design refers to the sum of all your design choices, suggesting it’s more like a research methodology . Others run off on other less common tangents. No wonder there’s confusion!

In this article, we’ll clear up the confusion. We’ll explain the most common research design types for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

Research Design: Quantitative Studies

Quantitative research involves collecting and analysing data in a numerical form. Broadly speaking, there are four types of quantitative research designs: descriptive , correlational , experimental , and quasi-experimental .

Descriptive Research Design

As the name suggests, descriptive research design focuses on describing existing conditions, behaviours, or characteristics by systematically gathering information without manipulating any variables. In other words, there is no intervention on the researcher’s part – only data collection.

For example, if you’re studying smartphone addiction among adolescents in your community, you could deploy a survey to a sample of teens asking them to rate their agreement with certain statements that relate to smartphone addiction. The collected data would then provide insight regarding how widespread the issue may be – in other words, it would describe the situation.

The key defining attribute of this type of research design is that it purely describes the situation . In other words, descriptive research design does not explore potential relationships between different variables or the causes that may underlie those relationships. Therefore, descriptive research is useful for generating insight into a research problem by describing its characteristics . By doing so, it can provide valuable insights and is often used as a precursor to other research design types.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational design is a popular choice for researchers aiming to identify and measure the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them . In other words, this type of research design is useful when you want to know whether a change in one thing tends to be accompanied by a change in another thing.

For example, if you wanted to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and overall health, you could use a correlational design to help you achieve this. In this case, you might gather data on participants’ exercise habits, as well as records of their health indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, or body mass index. Thereafter, you’d use a statistical test to assess whether there’s a relationship between the two variables (exercise frequency and health).

As you can see, correlational research design is useful when you want to explore potential relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled for ethical, practical, or logistical reasons. It is particularly helpful in terms of developing predictions , and given that it doesn’t involve the manipulation of variables, it can be implemented at a large scale more easily than experimental designs (which will look at next).

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that correlational research design has limitations – most notably that it cannot be used to establish causality . In other words, correlation does not equal causation . To establish causality, you’ll need to move into the realm of experimental design, coming up next…

Need a helping hand?

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to determine if there is a causal relationship between two or more variables . With this type of research design, you, as the researcher, manipulate one variable (the independent variable) while controlling others (dependent variables). Doing so allows you to observe the effect of the former on the latter and draw conclusions about potential causality.

For example, if you wanted to measure if/how different types of fertiliser affect plant growth, you could set up several groups of plants, with each group receiving a different type of fertiliser, as well as one with no fertiliser at all. You could then measure how much each plant group grew (on average) over time and compare the results from the different groups to see which fertiliser was most effective.

Overall, experimental research design provides researchers with a powerful way to identify and measure causal relationships (and the direction of causality) between variables. However, developing a rigorous experimental design can be challenging as it’s not always easy to control all the variables in a study. This often results in smaller sample sizes , which can reduce the statistical power and generalisability of the results.

Moreover, experimental research design requires random assignment . This means that the researcher needs to assign participants to different groups or conditions in a way that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group (note that this is not the same as random sampling ). Doing so helps reduce the potential for bias and confounding variables . This need for random assignment can lead to ethics-related issues . For example, withholding a potentially beneficial medical treatment from a control group may be considered unethical in certain situations.

Quasi-Experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used when the research aims involve identifying causal relations , but one cannot (or doesn’t want to) randomly assign participants to different groups (for practical or ethical reasons). Instead, with a quasi-experimental research design, the researcher relies on existing groups or pre-existing conditions to form groups for comparison.

For example, if you were studying the effects of a new teaching method on student achievement in a particular school district, you may be unable to randomly assign students to either group and instead have to choose classes or schools that already use different teaching methods. This way, you still achieve separate groups, without having to assign participants to specific groups yourself.

Naturally, quasi-experimental research designs have limitations when compared to experimental designs. Given that participant assignment is not random, it’s more difficult to confidently establish causality between variables, and, as a researcher, you have less control over other variables that may impact findings.

All that said, quasi-experimental designs can still be valuable in research contexts where random assignment is not possible and can often be undertaken on a much larger scale than experimental research, thus increasing the statistical power of the results. What’s important is that you, as the researcher, understand the limitations of the design and conduct your quasi-experiment as rigorously as possible, paying careful attention to any potential confounding variables .

Research Design: Qualitative Studies

There are many different research design types when it comes to qualitative studies, but here we’ll narrow our focus to explore the “Big 4”. Specifically, we’ll look at phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

Phenomenological Research Design

Phenomenological design involves exploring the meaning of lived experiences and how they are perceived by individuals. This type of research design seeks to understand people’s perspectives , emotions, and behaviours in specific situations. Here, the aim for researchers is to uncover the essence of human experience without making any assumptions or imposing preconceived ideas on their subjects.

For example, you could adopt a phenomenological design to study why cancer survivors have such varied perceptions of their lives after overcoming their disease. This could be achieved by interviewing survivors and then analysing the data using a qualitative analysis method such as thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences.

Phenomenological research design typically involves in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ subjective experiences. This richness is one of the key strengths of phenomenological research design but, naturally, it also has limitations. These include potential biases in data collection and interpretation and the lack of generalisability of findings to broader populations.

Grounded Theory Research Design

Grounded theory (also referred to as “GT”) aims to develop theories by continuously and iteratively analysing and comparing data collected from a relatively large number of participants in a study. It takes an inductive (bottom-up) approach, with a focus on letting the data “speak for itself”, without being influenced by preexisting theories or the researcher’s preconceptions.

As an example, let’s assume your research aims involved understanding how people cope with chronic pain from a specific medical condition, with a view to developing a theory around this. In this case, grounded theory design would allow you to explore this concept thoroughly without preconceptions about what coping mechanisms might exist. You may find that some patients prefer cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) while others prefer to rely on herbal remedies. Based on multiple, iterative rounds of analysis, you could then develop a theory in this regard, derived directly from the data (as opposed to other preexisting theories and models).

Grounded theory typically involves collecting data through interviews or observations and then analysing it to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data. These emerging ideas are then validated by collecting more data until a saturation point is reached (i.e., no new information can be squeezed from the data). From that base, a theory can then be developed .

As you can see, grounded theory is ideally suited to studies where the research aims involve theory generation , especially in under-researched areas. Keep in mind though that this type of research design can be quite time-intensive , given the need for multiple rounds of data collection and analysis.

Ethnographic Research Design

Ethnographic design involves observing and studying a culture-sharing group of people in their natural setting to gain insight into their behaviours, beliefs, and values. The focus here is on observing participants in their natural environment (as opposed to a controlled environment). This typically involves the researcher spending an extended period of time with the participants in their environment, carefully observing and taking field notes .

All of this is not to say that ethnographic research design relies purely on observation. On the contrary, this design typically also involves in-depth interviews to explore participants’ views, beliefs, etc. However, unobtrusive observation is a core component of the ethnographic approach.

As an example, an ethnographer may study how different communities celebrate traditional festivals or how individuals from different generations interact with technology differently. This may involve a lengthy period of observation, combined with in-depth interviews to further explore specific areas of interest that emerge as a result of the observations that the researcher has made.

As you can probably imagine, ethnographic research design has the ability to provide rich, contextually embedded insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of human behaviour within a natural, uncontrived setting. Naturally, however, it does come with its own set of challenges, including researcher bias (since the researcher can become quite immersed in the group), participant confidentiality and, predictably, ethical complexities . All of these need to be carefully managed if you choose to adopt this type of research design.

Case Study Design

With case study research design, you, as the researcher, investigate a single individual (or a single group of individuals) to gain an in-depth understanding of their experiences, behaviours or outcomes. Unlike other research designs that are aimed at larger sample sizes, case studies offer a deep dive into the specific circumstances surrounding a person, group of people, event or phenomenon, generally within a bounded setting or context .

As an example, a case study design could be used to explore the factors influencing the success of a specific small business. This would involve diving deeply into the organisation to explore and understand what makes it tick – from marketing to HR to finance. In terms of data collection, this could include interviews with staff and management, review of policy documents and financial statements, surveying customers, etc.

While the above example is focused squarely on one organisation, it’s worth noting that case study research designs can have different variation s, including single-case, multiple-case and longitudinal designs. As you can see in the example, a single-case design involves intensely examining a single entity to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. Conversely, in a multiple-case design , multiple cases are compared and contrasted to identify patterns and commonalities. Lastly, in a longitudinal case design , a single case or multiple cases are studied over an extended period of time to understand how factors develop over time.

As you can see, a case study research design is particularly useful where a deep and contextualised understanding of a specific phenomenon or issue is desired. However, this strength is also its weakness. In other words, you can’t generalise the findings from a case study to the broader population. So, keep this in mind if you’re considering going the case study route.

How To Choose A Research Design

Having worked through all of these potential research designs, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed and wondering, “ But how do I decide which research design to use? ”. While we could write an entire post covering that alone, here are a few factors to consider that will help you choose a suitable research design for your study.

Data type: The first determining factor is naturally the type of data you plan to be collecting – i.e., qualitative or quantitative. This may sound obvious, but we have to be clear about this – don’t try to use a quantitative research design on qualitative data (or vice versa)!

Research aim(s) and question(s): As with all methodological decisions, your research aim and research questions will heavily influence your research design. For example, if your research aims involve developing a theory from qualitative data, grounded theory would be a strong option. Similarly, if your research aims involve identifying and measuring relationships between variables, one of the experimental designs would likely be a better option.

Time: It’s essential that you consider any time constraints you have, as this will impact the type of research design you can choose. For example, if you’ve only got a month to complete your project, a lengthy design such as ethnography wouldn’t be a good fit.

Resources: Take into account the resources realistically available to you, as these need to factor into your research design choice. For example, if you require highly specialised lab equipment to execute an experimental design, you need to be sure that you’ll have access to that before you make a decision.

Keep in mind that when it comes to research, it’s important to manage your risks and play as conservatively as possible. If your entire project relies on you achieving a huge sample, having access to niche equipment or holding interviews with very difficult-to-reach participants, you’re creating risks that could kill your project. So, be sure to think through your choices carefully and make sure that you have backup plans for any existential risks. Remember that a relatively simple methodology executed well generally will typically earn better marks than a highly-complex methodology executed poorly.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Let’s recap by looking at the key takeaways:

- Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project, from its conception to the final analysis of data.

- Research designs for quantitative studies include descriptive , correlational , experimental and quasi-experimenta l designs.

- Research designs for qualitative studies include phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic and case study designs.

- When choosing a research design, you need to consider a variety of factors, including the type of data you’ll be working with, your research aims and questions, your time and the resources available to you.

If you need a helping hand with your research design (or any other aspect of your research), check out our private coaching services .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

10 Comments

Is there any blog article explaining more on Case study research design? Is there a Case study write-up template? Thank you.

Thanks this was quite valuable to clarify such an important concept.

Thanks for this simplified explanations. it is quite very helpful.

This was really helpful. thanks

Thank you for your explanation. I think case study research design and the use of secondary data in researches needs to be talked about more in your videos and articles because there a lot of case studies research design tailored projects out there.

Please is there any template for a case study research design whose data type is a secondary data on your repository?

This post is very clear, comprehensive and has been very helpful to me. It has cleared the confusion I had in regard to research design and methodology.

This post is helpful, easy to understand, and deconstructs what a research design is. Thanks

how to cite this page

Thank you very much for the post. It is wonderful and has cleared many worries in my mind regarding research designs. I really appreciate .

how can I put this blog as my reference(APA style) in bibliography part?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

The Four Types of Research Design — Everything You Need to Know

Updated: December 11, 2023

Published: January 18, 2023

When you conduct research, you need to have a clear idea of what you want to achieve and how to accomplish it. A good research design enables you to collect accurate and reliable data to draw valid conclusions.

In this blog post, we'll outline the key features of the four common types of research design with real-life examples from UnderArmor, Carmex, and more. Then, you can easily choose the right approach for your project.

Table of Contents

What is research design?

The four types of research design, research design examples.

Research design is the process of planning and executing a study to answer specific questions. This process allows you to test hypotheses in the business or scientific fields.

Research design involves choosing the right methodology, selecting the most appropriate data collection methods, and devising a plan (or framework) for analyzing the data. In short, a good research design helps us to structure our research.

Marketers use different types of research design when conducting research .

There are four common types of research design — descriptive, correlational, experimental, and diagnostic designs. Let’s take a look at each in more detail.

Researchers use different designs to accomplish different research objectives. Here, we'll discuss how to choose the right type, the benefits of each, and use cases.

Research can also be classified as quantitative or qualitative at a higher level. Some experiments exhibit both qualitative and quantitative characteristics.

.png)

Free Market Research Kit

5 Research and Planning Templates + a Free Guide on How to Use Them in Your Market Research

- SWOT Analysis Template

- Survey Template

- Focus Group Template

Download Free

All fields are required.

You're all set!

Click this link to access this resource at any time.

Experimental

An experimental design is used when the researcher wants to examine how variables interact with each other. The researcher manipulates one variable (the independent variable) and observes the effect on another variable (the dependent variable).

In other words, the researcher wants to test a causal relationship between two or more variables.

In marketing, an example of experimental research would be comparing the effects of a television commercial versus an online advertisement conducted in a controlled environment (e.g. a lab). The objective of the research is to test which advertisement gets more attention among people of different age groups, gender, etc.

Another example is a study of the effect of music on productivity. A researcher assigns participants to one of two groups — those who listen to music while working and those who don't — and measure their productivity.

The main benefit of an experimental design is that it allows the researcher to draw causal relationships between variables.

One limitation: This research requires a great deal of control over the environment and participants, making it difficult to replicate in the real world. In addition, it’s quite costly.

Best for: Testing a cause-and-effect relationship (i.e., the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable).

Correlational

A correlational design examines the relationship between two or more variables without intervening in the process.

Correlational design allows the analyst to observe natural relationships between variables. This results in data being more reflective of real-world situations.

For example, marketers can use correlational design to examine the relationship between brand loyalty and customer satisfaction. In particular, the researcher would look for patterns or trends in the data to see if there is a relationship between these two entities.

Similarly, you can study the relationship between physical activity and mental health. The analyst here would ask participants to complete surveys about their physical activity levels and mental health status. Data would show how the two variables are related.

Best for: Understanding the extent to which two or more variables are associated with each other in the real world.

Descriptive

Descriptive research refers to a systematic process of observing and describing what a subject does without influencing them.

Methods include surveys, interviews, case studies, and observations. Descriptive research aims to gather an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon and answers when/what/where.

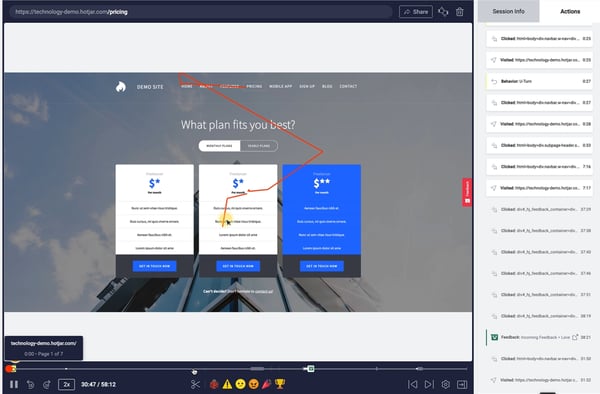

SaaS companies use descriptive design to understand how customers interact with specific features. Findings can be used to spot patterns and roadblocks.

For instance, product managers can use screen recordings by Hotjar to observe in-app user behavior. This way, the team can precisely understand what is happening at a certain stage of the user journey and act accordingly.

Brand24, a social listening tool, tripled its sign-up conversion rate from 2.56% to 7.42%, thanks to locating friction points in the sign-up form through screen recordings.

Carma Laboratories worked with research company MMR to measure customers’ reactions to the lip-care company’s packaging and product . The goal was to find the cause of low sales for a recently launched line extension in Europe.

The team moderated a live, online focus group. Participants were shown w product samples, while AI and NLP natural language processing identified key themes in customer feedback.

This helped uncover key reasons for poor performance and guided changes in packaging.

Home » Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Design

Definition:

Research design refers to the overall strategy or plan for conducting a research study. It outlines the methods and procedures that will be used to collect and analyze data, as well as the goals and objectives of the study. Research design is important because it guides the entire research process and ensures that the study is conducted in a systematic and rigorous manner.

Types of Research Design

Types of Research Design are as follows:

Descriptive Research Design

This type of research design is used to describe a phenomenon or situation. It involves collecting data through surveys, questionnaires, interviews, and observations. The aim of descriptive research is to provide an accurate and detailed portrayal of a particular group, event, or situation. It can be useful in identifying patterns, trends, and relationships in the data.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational research design is used to determine if there is a relationship between two or more variables. This type of research design involves collecting data from participants and analyzing the relationship between the variables using statistical methods. The aim of correlational research is to identify the strength and direction of the relationship between the variables.

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to investigate cause-and-effect relationships between variables. This type of research design involves manipulating one variable and measuring the effect on another variable. It usually involves randomly assigning participants to groups and manipulating an independent variable to determine its effect on a dependent variable. The aim of experimental research is to establish causality.

Quasi-experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is similar to experimental research design, but it lacks one or more of the features of a true experiment. For example, there may not be random assignment to groups or a control group. This type of research design is used when it is not feasible or ethical to conduct a true experiment.

Case Study Research Design

Case study research design is used to investigate a single case or a small number of cases in depth. It involves collecting data through various methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. The aim of case study research is to provide an in-depth understanding of a particular case or situation.

Longitudinal Research Design

Longitudinal research design is used to study changes in a particular phenomenon over time. It involves collecting data at multiple time points and analyzing the changes that occur. The aim of longitudinal research is to provide insights into the development, growth, or decline of a particular phenomenon over time.

Structure of Research Design

The format of a research design typically includes the following sections:

- Introduction : This section provides an overview of the research problem, the research questions, and the importance of the study. It also includes a brief literature review that summarizes previous research on the topic and identifies gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Research Questions or Hypotheses: This section identifies the specific research questions or hypotheses that the study will address. These questions should be clear, specific, and testable.

- Research Methods : This section describes the methods that will be used to collect and analyze data. It includes details about the study design, the sampling strategy, the data collection instruments, and the data analysis techniques.

- Data Collection: This section describes how the data will be collected, including the sample size, data collection procedures, and any ethical considerations.

- Data Analysis: This section describes how the data will be analyzed, including the statistical techniques that will be used to test the research questions or hypotheses.

- Results : This section presents the findings of the study, including descriptive statistics and statistical tests.

- Discussion and Conclusion : This section summarizes the key findings of the study, interprets the results, and discusses the implications of the findings. It also includes recommendations for future research.

- References : This section lists the sources cited in the research design.

Example of Research Design

An Example of Research Design could be:

Research question: Does the use of social media affect the academic performance of high school students?

Research design:

- Research approach : The research approach will be quantitative as it involves collecting numerical data to test the hypothesis.

- Research design : The research design will be a quasi-experimental design, with a pretest-posttest control group design.

- Sample : The sample will be 200 high school students from two schools, with 100 students in the experimental group and 100 students in the control group.

- Data collection : The data will be collected through surveys administered to the students at the beginning and end of the academic year. The surveys will include questions about their social media usage and academic performance.

- Data analysis : The data collected will be analyzed using statistical software. The mean scores of the experimental and control groups will be compared to determine whether there is a significant difference in academic performance between the two groups.

- Limitations : The limitations of the study will be acknowledged, including the fact that social media usage can vary greatly among individuals, and the study only focuses on two schools, which may not be representative of the entire population.

- Ethical considerations: Ethical considerations will be taken into account, such as obtaining informed consent from the participants and ensuring their anonymity and confidentiality.

How to Write Research Design

Writing a research design involves planning and outlining the methodology and approach that will be used to answer a research question or hypothesis. Here are some steps to help you write a research design:

- Define the research question or hypothesis : Before beginning your research design, you should clearly define your research question or hypothesis. This will guide your research design and help you select appropriate methods.

- Select a research design: There are many different research designs to choose from, including experimental, survey, case study, and qualitative designs. Choose a design that best fits your research question and objectives.

- Develop a sampling plan : If your research involves collecting data from a sample, you will need to develop a sampling plan. This should outline how you will select participants and how many participants you will include.

- Define variables: Clearly define the variables you will be measuring or manipulating in your study. This will help ensure that your results are meaningful and relevant to your research question.

- Choose data collection methods : Decide on the data collection methods you will use to gather information. This may include surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, or secondary data sources.

- Create a data analysis plan: Develop a plan for analyzing your data, including the statistical or qualitative techniques you will use.

- Consider ethical concerns : Finally, be sure to consider any ethical concerns related to your research, such as participant confidentiality or potential harm.

When to Write Research Design

Research design should be written before conducting any research study. It is an important planning phase that outlines the research methodology, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques that will be used to investigate a research question or problem. The research design helps to ensure that the research is conducted in a systematic and logical manner, and that the data collected is relevant and reliable.

Ideally, the research design should be developed as early as possible in the research process, before any data is collected. This allows the researcher to carefully consider the research question, identify the most appropriate research methodology, and plan the data collection and analysis procedures in advance. By doing so, the research can be conducted in a more efficient and effective manner, and the results are more likely to be valid and reliable.

Purpose of Research Design

The purpose of research design is to plan and structure a research study in a way that enables the researcher to achieve the desired research goals with accuracy, validity, and reliability. Research design is the blueprint or the framework for conducting a study that outlines the methods, procedures, techniques, and tools for data collection and analysis.

Some of the key purposes of research design include:

- Providing a clear and concise plan of action for the research study.

- Ensuring that the research is conducted ethically and with rigor.

- Maximizing the accuracy and reliability of the research findings.

- Minimizing the possibility of errors, biases, or confounding variables.

- Ensuring that the research is feasible, practical, and cost-effective.

- Determining the appropriate research methodology to answer the research question(s).

- Identifying the sample size, sampling method, and data collection techniques.

- Determining the data analysis method and statistical tests to be used.

- Facilitating the replication of the study by other researchers.

- Enhancing the validity and generalizability of the research findings.

Applications of Research Design

There are numerous applications of research design in various fields, some of which are:

- Social sciences: In fields such as psychology, sociology, and anthropology, research design is used to investigate human behavior and social phenomena. Researchers use various research designs, such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and correlational designs, to study different aspects of social behavior.

- Education : Research design is essential in the field of education to investigate the effectiveness of different teaching methods and learning strategies. Researchers use various designs such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and case study designs to understand how students learn and how to improve teaching practices.

- Health sciences : In the health sciences, research design is used to investigate the causes, prevention, and treatment of diseases. Researchers use various designs, such as randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies, to study different aspects of health and healthcare.

- Business : Research design is used in the field of business to investigate consumer behavior, marketing strategies, and the impact of different business practices. Researchers use various designs, such as survey research, experimental research, and case studies, to study different aspects of the business world.

- Engineering : In the field of engineering, research design is used to investigate the development and implementation of new technologies. Researchers use various designs, such as experimental research and case studies, to study the effectiveness of new technologies and to identify areas for improvement.

Advantages of Research Design

Here are some advantages of research design:

- Systematic and organized approach : A well-designed research plan ensures that the research is conducted in a systematic and organized manner, which makes it easier to manage and analyze the data.

- Clear objectives: The research design helps to clarify the objectives of the study, which makes it easier to identify the variables that need to be measured, and the methods that need to be used to collect and analyze data.

- Minimizes bias: A well-designed research plan minimizes the chances of bias, by ensuring that the data is collected and analyzed objectively, and that the results are not influenced by the researcher’s personal biases or preferences.

- Efficient use of resources: A well-designed research plan helps to ensure that the resources (time, money, and personnel) are used efficiently and effectively, by focusing on the most important variables and methods.

- Replicability: A well-designed research plan makes it easier for other researchers to replicate the study, which enhances the credibility and reliability of the findings.

- Validity: A well-designed research plan helps to ensure that the findings are valid, by ensuring that the methods used to collect and analyze data are appropriate for the research question.

- Generalizability : A well-designed research plan helps to ensure that the findings can be generalized to other populations, settings, or situations, which increases the external validity of the study.

Research Design Vs Research Methodology

| Research Design | Research Methodology |

|---|---|

| The plan and structure for conducting research that outlines the procedures to be followed to collect and analyze data. | The set of principles, techniques, and tools used to carry out the research plan and achieve research objectives. |

| Describes the overall approach and strategy used to conduct research, including the type of data to be collected, the sources of data, and the methods for collecting and analyzing data. | Refers to the techniques and methods used to gather, analyze and interpret data, including sampling techniques, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques. |

| Helps to ensure that the research is conducted in a systematic, rigorous, and valid way, so that the results are reliable and can be used to make sound conclusions. | Includes a set of procedures and tools that enable researchers to collect and analyze data in a consistent and valid manner, regardless of the research design used. |

| Common research designs include experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational, and descriptive studies. | Common research methodologies include qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods approaches. |

| Determines the overall structure of the research project and sets the stage for the selection of appropriate research methodologies. | Guides the researcher in selecting the most appropriate research methods based on the research question, research design, and other contextual factors. |

| Helps to ensure that the research project is feasible, relevant, and ethical. | Helps to ensure that the data collected is accurate, valid, and reliable, and that the research findings can be interpreted and generalized to the population of interest. |

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and...

Limitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Topics – Ideas and Examples

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Leave a comment x.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Types of Research Designs

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Introduction

Before beginning your paper, you need to decide how you plan to design the study .

The research design refers to the overall strategy and analytical approach that you have chosen in order to integrate, in a coherent and logical way, the different components of the study, thus ensuring that the research problem will be thoroughly investigated. It constitutes the blueprint for the collection, measurement, and interpretation of information and data. Note that the research problem determines the type of design you choose, not the other way around!

De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

General Structure and Writing Style

The function of a research design is to ensure that the evidence obtained enables you to effectively address the research problem logically and as unambiguously as possible . In social sciences research, obtaining information relevant to the research problem generally entails specifying the type of evidence needed to test the underlying assumptions of a theory, to evaluate a program, or to accurately describe and assess meaning related to an observable phenomenon.

With this in mind, a common mistake made by researchers is that they begin their investigations before they have thought critically about what information is required to address the research problem. Without attending to these design issues beforehand, the overall research problem will not be adequately addressed and any conclusions drawn will run the risk of being weak and unconvincing. As a consequence, the overall validity of the study will be undermined.

The length and complexity of describing the research design in your paper can vary considerably, but any well-developed description will achieve the following :

- Identify the research problem clearly and justify its selection, particularly in relation to any valid alternative designs that could have been used,

- Review and synthesize previously published literature associated with the research problem,

- Clearly and explicitly specify hypotheses [i.e., research questions] central to the problem,

- Effectively describe the information and/or data which will be necessary for an adequate testing of the hypotheses and explain how such information and/or data will be obtained, and

- Describe the methods of analysis to be applied to the data in determining whether or not the hypotheses are true or false.

The research design is usually incorporated into the introduction of your paper . You can obtain an overall sense of what to do by reviewing studies that have utilized the same research design [e.g., using a case study approach]. This can help you develop an outline to follow for your own paper.

NOTE: Use the SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases and the SAGE Research Methods Videos databases to search for scholarly resources on how to apply specific research designs and methods . The Research Methods Online database contains links to more than 175,000 pages of SAGE publisher's book, journal, and reference content on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methodologies. Also included is a collection of case studies of social research projects that can be used to help you better understand abstract or complex methodological concepts. The Research Methods Videos database contains hours of tutorials, interviews, video case studies, and mini-documentaries covering the entire research process.

Creswell, John W. and J. David Creswell. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018; De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Leedy, Paul D. and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. Practical Research: Planning and Design . Tenth edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2013; Vogt, W. Paul, Dianna C. Gardner, and Lynne M. Haeffele. When to Use What Research Design . New York: Guilford, 2012.

Action Research Design

Definition and Purpose

The essentials of action research design follow a characteristic cycle whereby initially an exploratory stance is adopted, where an understanding of a problem is developed and plans are made for some form of interventionary strategy. Then the intervention is carried out [the "action" in action research] during which time, pertinent observations are collected in various forms. The new interventional strategies are carried out, and this cyclic process repeats, continuing until a sufficient understanding of [or a valid implementation solution for] the problem is achieved. The protocol is iterative or cyclical in nature and is intended to foster deeper understanding of a given situation, starting with conceptualizing and particularizing the problem and moving through several interventions and evaluations.

What do these studies tell you ?

- This is a collaborative and adaptive research design that lends itself to use in work or community situations.

- Design focuses on pragmatic and solution-driven research outcomes rather than testing theories.

- When practitioners use action research, it has the potential to increase the amount they learn consciously from their experience; the action research cycle can be regarded as a learning cycle.

- Action research studies often have direct and obvious relevance to improving practice and advocating for change.

- There are no hidden controls or preemption of direction by the researcher.

What these studies don't tell you ?

- It is harder to do than conducting conventional research because the researcher takes on responsibilities of advocating for change as well as for researching the topic.

- Action research is much harder to write up because it is less likely that you can use a standard format to report your findings effectively [i.e., data is often in the form of stories or observation].

- Personal over-involvement of the researcher may bias research results.

- The cyclic nature of action research to achieve its twin outcomes of action [e.g. change] and research [e.g. understanding] is time-consuming and complex to conduct.

- Advocating for change usually requires buy-in from study participants.

Coghlan, David and Mary Brydon-Miller. The Sage Encyclopedia of Action Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014; Efron, Sara Efrat and Ruth Ravid. Action Research in Education: A Practical Guide . New York: Guilford, 2013; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 18, Action Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Kemmis, Stephen and Robin McTaggart. “Participatory Action Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2000), pp. 567-605; McNiff, Jean. Writing and Doing Action Research . London: Sage, 2014; Reason, Peter and Hilary Bradbury. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2001.

Case Study Design

A case study is an in-depth study of a particular research problem rather than a sweeping statistical survey or comprehensive comparative inquiry. It is often used to narrow down a very broad field of research into one or a few easily researchable examples. The case study research design is also useful for testing whether a specific theory and model actually applies to phenomena in the real world. It is a useful design when not much is known about an issue or phenomenon.

- Approach excels at bringing us to an understanding of a complex issue through detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships.

- A researcher using a case study design can apply a variety of methodologies and rely on a variety of sources to investigate a research problem.

- Design can extend experience or add strength to what is already known through previous research.

- Social scientists, in particular, make wide use of this research design to examine contemporary real-life situations and provide the basis for the application of concepts and theories and the extension of methodologies.

- The design can provide detailed descriptions of specific and rare cases.

- A single or small number of cases offers little basis for establishing reliability or to generalize the findings to a wider population of people, places, or things.

- Intense exposure to the study of a case may bias a researcher's interpretation of the findings.

- Design does not facilitate assessment of cause and effect relationships.

- Vital information may be missing, making the case hard to interpret.

- The case may not be representative or typical of the larger problem being investigated.

- If the criteria for selecting a case is because it represents a very unusual or unique phenomenon or problem for study, then your interpretation of the findings can only apply to that particular case.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 4, Flexible Methods: Case Study Design. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Greenhalgh, Trisha, editor. Case Study Evaluation: Past, Present and Future Challenges . Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 2015; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Stake, Robert E. The Art of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1995; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Theory . Applied Social Research Methods Series, no. 5. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2003.

Causal Design

Causality studies may be thought of as understanding a phenomenon in terms of conditional statements in the form, “If X, then Y.” This type of research is used to measure what impact a specific change will have on existing norms and assumptions. Most social scientists seek causal explanations that reflect tests of hypotheses. Causal effect (nomothetic perspective) occurs when variation in one phenomenon, an independent variable, leads to or results, on average, in variation in another phenomenon, the dependent variable.

Conditions necessary for determining causality:

- Empirical association -- a valid conclusion is based on finding an association between the independent variable and the dependent variable.

- Appropriate time order -- to conclude that causation was involved, one must see that cases were exposed to variation in the independent variable before variation in the dependent variable.

- Nonspuriousness -- a relationship between two variables that is not due to variation in a third variable.

- Causality research designs assist researchers in understanding why the world works the way it does through the process of proving a causal link between variables and by the process of eliminating other possibilities.

- Replication is possible.

- There is greater confidence the study has internal validity due to the systematic subject selection and equity of groups being compared.

- Not all relationships are causal! The possibility always exists that, by sheer coincidence, two unrelated events appear to be related [e.g., Punxatawney Phil could accurately predict the duration of Winter for five consecutive years but, the fact remains, he's just a big, furry rodent].

- Conclusions about causal relationships are difficult to determine due to a variety of extraneous and confounding variables that exist in a social environment. This means causality can only be inferred, never proven.

- If two variables are correlated, the cause must come before the effect. However, even though two variables might be causally related, it can sometimes be difficult to determine which variable comes first and, therefore, to establish which variable is the actual cause and which is the actual effect.

Beach, Derek and Rasmus Brun Pedersen. Causal Case Study Methods: Foundations and Guidelines for Comparing, Matching, and Tracing . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016; Bachman, Ronet. The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice . Chapter 5, Causation and Research Designs. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 2007; Brewer, Ernest W. and Jennifer Kubn. “Causal-Comparative Design.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 125-132; Causal Research Design: Experimentation. Anonymous SlideShare Presentation; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 11, Nonexperimental Research: Correlational Designs. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

Cohort Design

Often used in the medical sciences, but also found in the applied social sciences, a cohort study generally refers to a study conducted over a period of time involving members of a population which the subject or representative member comes from, and who are united by some commonality or similarity. Using a quantitative framework, a cohort study makes note of statistical occurrence within a specialized subgroup, united by same or similar characteristics that are relevant to the research problem being investigated, rather than studying statistical occurrence within the general population. Using a qualitative framework, cohort studies generally gather data using methods of observation. Cohorts can be either "open" or "closed."

- Open Cohort Studies [dynamic populations, such as the population of Los Angeles] involve a population that is defined just by the state of being a part of the study in question (and being monitored for the outcome). Date of entry and exit from the study is individually defined, therefore, the size of the study population is not constant. In open cohort studies, researchers can only calculate rate based data, such as, incidence rates and variants thereof.

- Closed Cohort Studies [static populations, such as patients entered into a clinical trial] involve participants who enter into the study at one defining point in time and where it is presumed that no new participants can enter the cohort. Given this, the number of study participants remains constant (or can only decrease).

- The use of cohorts is often mandatory because a randomized control study may be unethical. For example, you cannot deliberately expose people to asbestos, you can only study its effects on those who have already been exposed. Research that measures risk factors often relies upon cohort designs.

- Because cohort studies measure potential causes before the outcome has occurred, they can demonstrate that these “causes” preceded the outcome, thereby avoiding the debate as to which is the cause and which is the effect.

- Cohort analysis is highly flexible and can provide insight into effects over time and related to a variety of different types of changes [e.g., social, cultural, political, economic, etc.].

- Either original data or secondary data can be used in this design.

- In cases where a comparative analysis of two cohorts is made [e.g., studying the effects of one group exposed to asbestos and one that has not], a researcher cannot control for all other factors that might differ between the two groups. These factors are known as confounding variables.

- Cohort studies can end up taking a long time to complete if the researcher must wait for the conditions of interest to develop within the group. This also increases the chance that key variables change during the course of the study, potentially impacting the validity of the findings.

- Due to the lack of randominization in the cohort design, its external validity is lower than that of study designs where the researcher randomly assigns participants.

Healy P, Devane D. “Methodological Considerations in Cohort Study Designs.” Nurse Researcher 18 (2011): 32-36; Glenn, Norval D, editor. Cohort Analysis . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Levin, Kate Ann. Study Design IV: Cohort Studies. Evidence-Based Dentistry 7 (2003): 51–52; Payne, Geoff. “Cohort Study.” In The SAGE Dictionary of Social Research Methods . Victor Jupp, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), pp. 31-33; Study Design 101. Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. George Washington University, November 2011; Cohort Study. Wikipedia.

Cross-Sectional Design

Cross-sectional research designs have three distinctive features: no time dimension; a reliance on existing differences rather than change following intervention; and, groups are selected based on existing differences rather than random allocation. The cross-sectional design can only measure differences between or from among a variety of people, subjects, or phenomena rather than a process of change. As such, researchers using this design can only employ a relatively passive approach to making causal inferences based on findings.

- Cross-sectional studies provide a clear 'snapshot' of the outcome and the characteristics associated with it, at a specific point in time.

- Unlike an experimental design, where there is an active intervention by the researcher to produce and measure change or to create differences, cross-sectional designs focus on studying and drawing inferences from existing differences between people, subjects, or phenomena.

- Entails collecting data at and concerning one point in time. While longitudinal studies involve taking multiple measures over an extended period of time, cross-sectional research is focused on finding relationships between variables at one moment in time.

- Groups identified for study are purposely selected based upon existing differences in the sample rather than seeking random sampling.

- Cross-section studies are capable of using data from a large number of subjects and, unlike observational studies, is not geographically bound.

- Can estimate prevalence of an outcome of interest because the sample is usually taken from the whole population.

- Because cross-sectional designs generally use survey techniques to gather data, they are relatively inexpensive and take up little time to conduct.

- Finding people, subjects, or phenomena to study that are very similar except in one specific variable can be difficult.

- Results are static and time bound and, therefore, give no indication of a sequence of events or reveal historical or temporal contexts.

- Studies cannot be utilized to establish cause and effect relationships.

- This design only provides a snapshot of analysis so there is always the possibility that a study could have differing results if another time-frame had been chosen.

- There is no follow up to the findings.

Bethlehem, Jelke. "7: Cross-sectional Research." In Research Methodology in the Social, Behavioural and Life Sciences . Herman J Adèr and Gideon J Mellenbergh, editors. (London, England: Sage, 1999), pp. 110-43; Bourque, Linda B. “Cross-Sectional Design.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods . Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Alan Bryman, and Tim Futing Liao. (Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004), pp. 230-231; Hall, John. “Cross-Sectional Survey Design.” In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods . Paul J. Lavrakas, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 173-174; Helen Barratt, Maria Kirwan. Cross-Sectional Studies: Design Application, Strengths and Weaknesses of Cross-Sectional Studies. Healthknowledge, 2009. Cross-Sectional Study. Wikipedia.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research designs help provide answers to the questions of who, what, when, where, and how associated with a particular research problem; a descriptive study cannot conclusively ascertain answers to why. Descriptive research is used to obtain information concerning the current status of the phenomena and to describe "what exists" with respect to variables or conditions in a situation.

- The subject is being observed in a completely natural and unchanged natural environment. True experiments, whilst giving analyzable data, often adversely influence the normal behavior of the subject [a.k.a., the Heisenberg effect whereby measurements of certain systems cannot be made without affecting the systems].

- Descriptive research is often used as a pre-cursor to more quantitative research designs with the general overview giving some valuable pointers as to what variables are worth testing quantitatively.

- If the limitations are understood, they can be a useful tool in developing a more focused study.

- Descriptive studies can yield rich data that lead to important recommendations in practice.

- Appoach collects a large amount of data for detailed analysis.

- The results from a descriptive research cannot be used to discover a definitive answer or to disprove a hypothesis.

- Because descriptive designs often utilize observational methods [as opposed to quantitative methods], the results cannot be replicated.

- The descriptive function of research is heavily dependent on instrumentation for measurement and observation.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 5, Flexible Methods: Descriptive Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Given, Lisa M. "Descriptive Research." In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics . Neil J. Salkind and Kristin Rasmussen, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2007), pp. 251-254; McNabb, Connie. Descriptive Research Methodologies. Powerpoint Presentation; Shuttleworth, Martyn. Descriptive Research Design, September 26, 2008; Erickson, G. Scott. "Descriptive Research Design." In New Methods of Market Research and Analysis . (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017), pp. 51-77; Sahin, Sagufta, and Jayanta Mete. "A Brief Study on Descriptive Research: Its Nature and Application in Social Science." International Journal of Research and Analysis in Humanities 1 (2021): 11; K. Swatzell and P. Jennings. “Descriptive Research: The Nuts and Bolts.” Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants 20 (2007), pp. 55-56; Kane, E. Doing Your Own Research: Basic Descriptive Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities . London: Marion Boyars, 1985.

Experimental Design

A blueprint of the procedure that enables the researcher to maintain control over all factors that may affect the result of an experiment. In doing this, the researcher attempts to determine or predict what may occur. Experimental research is often used where there is time priority in a causal relationship (cause precedes effect), there is consistency in a causal relationship (a cause will always lead to the same effect), and the magnitude of the correlation is great. The classic experimental design specifies an experimental group and a control group. The independent variable is administered to the experimental group and not to the control group, and both groups are measured on the same dependent variable. Subsequent experimental designs have used more groups and more measurements over longer periods. True experiments must have control, randomization, and manipulation.

- Experimental research allows the researcher to control the situation. In so doing, it allows researchers to answer the question, “What causes something to occur?”

- Permits the researcher to identify cause and effect relationships between variables and to distinguish placebo effects from treatment effects.

- Experimental research designs support the ability to limit alternative explanations and to infer direct causal relationships in the study.

- Approach provides the highest level of evidence for single studies.

- The design is artificial, and results may not generalize well to the real world.

- The artificial settings of experiments may alter the behaviors or responses of participants.

- Experimental designs can be costly if special equipment or facilities are needed.

- Some research problems cannot be studied using an experiment because of ethical or technical reasons.

- Difficult to apply ethnographic and other qualitative methods to experimentally designed studies.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 7, Flexible Methods: Experimental Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Chapter 2: Research Design, Experimental Designs. School of Psychology, University of New England, 2000; Chow, Siu L. "Experimental Design." In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 448-453; "Experimental Design." In Social Research Methods . Nicholas Walliman, editor. (London, England: Sage, 2006), pp, 101-110; Experimental Research. Research Methods by Dummies. Department of Psychology. California State University, Fresno, 2006; Kirk, Roger E. Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Trochim, William M.K. Experimental Design. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Rasool, Shafqat. Experimental Research. Slideshare presentation.

Exploratory Design

An exploratory design is conducted about a research problem when there are few or no earlier studies to refer to or rely upon to predict an outcome . The focus is on gaining insights and familiarity for later investigation or undertaken when research problems are in a preliminary stage of investigation. Exploratory designs are often used to establish an understanding of how best to proceed in studying an issue or what methodology would effectively apply to gathering information about the issue.

The goals of exploratory research are intended to produce the following possible insights:

- Familiarity with basic details, settings, and concerns.

- Well grounded picture of the situation being developed.

- Generation of new ideas and assumptions.

- Development of tentative theories or hypotheses.

- Determination about whether a study is feasible in the future.

- Issues get refined for more systematic investigation and formulation of new research questions.

- Direction for future research and techniques get developed.

- Design is a useful approach for gaining background information on a particular topic.

- Exploratory research is flexible and can address research questions of all types (what, why, how).

- Provides an opportunity to define new terms and clarify existing concepts.

- Exploratory research is often used to generate formal hypotheses and develop more precise research problems.

- In the policy arena or applied to practice, exploratory studies help establish research priorities and where resources should be allocated.

- Exploratory research generally utilizes small sample sizes and, thus, findings are typically not generalizable to the population at large.

- The exploratory nature of the research inhibits an ability to make definitive conclusions about the findings. They provide insight but not definitive conclusions.

- The research process underpinning exploratory studies is flexible but often unstructured, leading to only tentative results that have limited value to decision-makers.

- Design lacks rigorous standards applied to methods of data gathering and analysis because one of the areas for exploration could be to determine what method or methodologies could best fit the research problem.

Cuthill, Michael. “Exploratory Research: Citizen Participation, Local Government, and Sustainable Development in Australia.” Sustainable Development 10 (2002): 79-89; Streb, Christoph K. "Exploratory Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos and Eiden Wiebe, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 372-374; Taylor, P. J., G. Catalano, and D.R.F. Walker. “Exploratory Analysis of the World City Network.” Urban Studies 39 (December 2002): 2377-2394; Exploratory Research. Wikipedia.

Field Research Design