Essay Papers Writing Online

Ultimate guide to writing a five paragraph essay.

Are you struggling with writing essays? Do you find yourself lost in a sea of ideas, unable to structure your thoughts cohesively? The five paragraph essay is a tried-and-true method that can guide you through the writing process with ease. By mastering this format, you can unlock the key to successful and organized writing.

In this article, we will break down the five paragraph essay into easy steps that anyone can follow. From crafting a strong thesis statement to effectively supporting your arguments, we will cover all the essential components of a well-written essay. Whether you are a beginner or a seasoned writer, these tips will help you hone your skills and express your ideas clearly.

Step-by-Step Guide to Mastering the Five Paragraph Essay

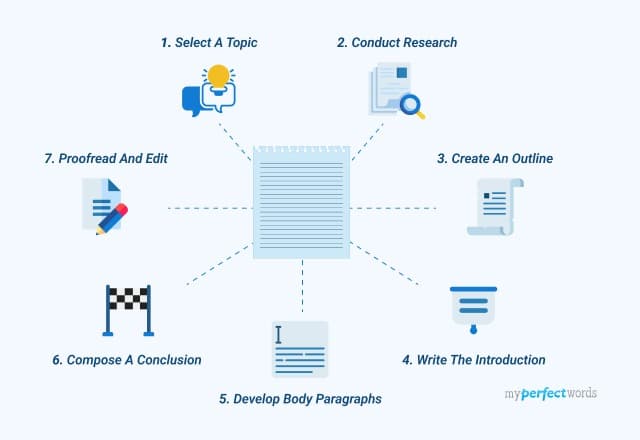

Writing a successful five paragraph essay can seem like a daunting task, but with the right approach and strategies, it can become much more manageable. Follow these steps to master the art of writing a powerful five paragraph essay:

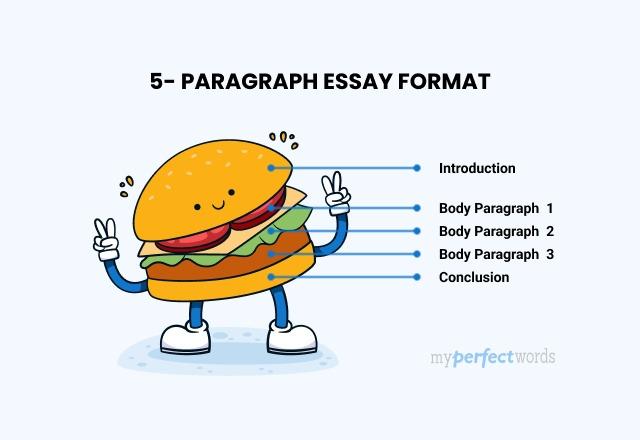

- Understand the structure: The five paragraph essay consists of an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Each paragraph serves a specific purpose in conveying your message effectively.

- Brainstorm and plan: Before you start writing, take the time to brainstorm ideas and create an outline. This will help you organize your thoughts and ensure that your essay flows smoothly.

- Write the introduction: Start your essay with a strong hook to grab the reader’s attention. Your introduction should also include a thesis statement, which is the main argument of your essay.

- Develop the body paragraphs: Each body paragraph should focus on a single point that supports your thesis. Use evidence, examples, and analysis to strengthen your argument and make your points clear.

- Conclude effectively: In your conclusion, summarize your main points and restate your thesis in a new way. Leave the reader with a thought-provoking statement or a call to action.

By following these steps and practicing regularly, you can become proficient in writing five paragraph essays that are clear, coherent, and impactful. Remember to revise and edit your work for grammar, punctuation, and clarity to ensure that your essay is polished and professional.

Understanding the Structure of a Five Paragraph Essay

When writing a five paragraph essay, it is important to understand the basic structure that makes up this type of essay. The five paragraph essay consists of an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Introduction: The introduction is the first paragraph of the essay and sets the tone for the rest of the piece. It should include a hook to grab the reader’s attention, a thesis statement that presents the main idea of the essay, and a brief overview of what will be discussed in the body paragraphs.

Body Paragraphs: The body paragraphs make up the core of the essay and each paragraph should focus on a single point that supports the thesis statement. These paragraphs should include a topic sentence that introduces the main idea, supporting details or evidence, and explanations or analysis of how the evidence supports the thesis.

Conclusion: The conclusion is the final paragraph of the essay and it should summarize the main points discussed in the body paragraphs. It should restate the thesis in different words, and provide a closing thought or reflection on the topic.

By understanding the structure of a five paragraph essay, writers can effectively organize their thoughts and present their ideas in a clear and coherent manner.

Choosing a Strong Thesis Statement

One of the most critical elements of a successful five-paragraph essay is a strong thesis statement. Your thesis statement should clearly and concisely present the main argument or point you will be making in your essay. It serves as the foundation for the entire essay, guiding the reader on what to expect and helping you stay focused throughout your writing.

When choosing a thesis statement, it’s important to make sure it is specific, debatable, and relevant to your topic. Avoid vague statements or generalizations, as they will weaken your argument and fail to provide a clear direction for your essay. Instead, choose a thesis statement that is narrow enough to be effectively supported within the confines of a five-paragraph essay, but broad enough to allow for meaningful discussion.

| Tip 1: | Brainstorm several potential thesis statements before settling on one. Consider different angles or perspectives on your topic to find the most compelling argument. |

| Tip 2: | Make sure your thesis statement is arguable. You want to present a position that can be debated or challenged, as this will lead to a more engaging and persuasive essay. |

| Tip 3: | Ensure your thesis statement directly addresses the prompt or question you are responding to. It should be relevant to the assigned topic and provide a clear focus for your essay. |

By choosing a strong thesis statement, you set yourself up for a successful essay that is well-organized, coherent, and persuasive. Take the time to carefully craft your thesis statement, as it will serve as the guiding force behind your entire essay.

Developing Supporting Arguments in Body Paragraphs

When crafting the body paragraphs of your five paragraph essay, it is crucial to develop strong and coherent supporting arguments that back up your thesis statement. Each body paragraph should focus on a single supporting argument that contributes to the overall discussion of your topic.

To effectively develop your supporting arguments, consider using a table to organize your ideas. Start by listing your main argument in the left column, and then provide evidence, examples, and analysis in the right column. This structured approach can help you ensure that each supporting argument is fully developed and logically presented.

Additionally, be sure to use transitional phrases to smoothly connect your supporting arguments within and between paragraphs. Words like “furthermore,” “in addition,” and “on the other hand” can help readers follow your train of thought and understand the progression of your ideas.

Remember, the body paragraphs are where you provide the meat of your argument, so take the time to develop each supporting argument thoroughly and clearly. By presenting compelling evidence and analysis, you can effectively persuade your readers and strengthen the overall impact of your essay.

Polishing Your Writing: Editing and Proofreading Tips

Editing and proofreading are crucial steps in the writing process that can make a significant difference in the clarity and effectiveness of your essay. Here are some tips to help you polish your writing:

1. Take a break before editing: After you finish writing your essay, take a break before starting the editing process. This will help you approach your work with fresh eyes and catch mistakes more easily.

2. Read your essay aloud: Reading your essay aloud can help you identify awkward phrasing, grammar errors, and inconsistencies. This technique can also help you evaluate the flow and coherence of your writing.

3. Use a spelling and grammar checker: Utilize spelling and grammar checkers available in word processing software to catch common errors. However, be mindful that these tools may not catch all mistakes, so it’s essential to manually review your essay as well.

4. Check for coherence and organization: Make sure your ideas flow logically and cohesively throughout your essay. Ensure that each paragraph connects smoothly to the next, and that your arguments are supported by relevant evidence.

5. Look for consistency: Check for consistency in your writing style, tone, and formatting. Ensure that you maintain a consistent voice and perspective throughout your essay to keep your argument coherent.

6. Seek feedback from others: Consider asking a peer, teacher, or tutor to review your essay and provide feedback. External perspectives can help you identify blind spots and areas for improvement in your writing.

7. Proofread carefully: Finally, proofread your essay carefully to catch any remaining errors in spelling, grammar, punctuation, and formatting. Pay attention to details and make any necessary revisions before submitting your final draft.

By following these editing and proofreading tips, you can refine your writing and ensure that your essay is polished and ready for submission.

Tips for Successful Writing: Practice and Feedback

Writing is a skill that improves with practice. The more you write, the better you will become. Set aside time each day to practice writing essays, paragraph by paragraph. This consistent practice will help you develop your writing skills and grow more confident in expressing your ideas.

Seek feedback from your teachers, peers, or mentors. Constructive criticism can help you identify areas for improvement and provide valuable insights into your writing. Take their suggestions into consideration and use them to refine your writing style and structure.

- Set writing goals for yourself and track your progress. Whether it’s completing a certain number of essays in a week or improving your introductions, having specific goals will keep you motivated and focused on your writing development.

- Read widely to expand your vocabulary and expose yourself to different writing styles. The more you read, the more you will learn about effective writing techniques and ways to engage your readers.

- Revise and edit your essays carefully. Pay attention to sentence structure, grammar, punctuation, and spelling. A well-polished essay will demonstrate your attention to detail and dedication to producing high-quality work.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

PeopleImages / Getty Images

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A five-paragraph essay is a prose composition that follows a prescribed format of an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph, and is typically taught during primary English education and applied on standardized testing throughout schooling.

Learning to write a high-quality five-paragraph essay is an essential skill for students in early English classes as it allows them to express certain ideas, claims, or concepts in an organized manner, complete with evidence that supports each of these notions. Later, though, students may decide to stray from the standard five-paragraph format and venture into writing an exploratory essay instead.

Still, teaching students to organize essays into the five-paragraph format is an easy way to introduce them to writing literary criticism, which will be tested time and again throughout their primary, secondary, and further education.

Writing a Good Introduction

The introduction is the first paragraph in your essay, and it should accomplish a few specific goals: capture the reader's interest, introduce the topic, and make a claim or express an opinion in a thesis statement.

It's a good idea to start your essay with a hook (fascinating statement) to pique the reader's interest, though this can also be accomplished by using descriptive words, an anecdote, an intriguing question, or an interesting fact. Students can practice with creative writing prompts to get some ideas for interesting ways to start an essay.

The next few sentences should explain your first statement, and prepare the reader for your thesis statement, which is typically the last sentence in the introduction. Your thesis sentence should provide your specific assertion and convey a clear point of view, which is typically divided into three distinct arguments that support this assertation, which will each serve as central themes for the body paragraphs.

Writing Body Paragraphs

The body of the essay will include three body paragraphs in a five-paragraph essay format, each limited to one main idea that supports your thesis.

To correctly write each of these three body paragraphs, you should state your supporting idea, your topic sentence, then back it up with two or three sentences of evidence. Use examples that validate the claim before concluding the paragraph and using transition words to lead to the paragraph that follows — meaning that all of your body paragraphs should follow the pattern of "statement, supporting ideas, transition statement."

Words to use as you transition from one paragraph to another include: moreover, in fact, on the whole, furthermore, as a result, simply put, for this reason, similarly, likewise, it follows that, naturally, by comparison, surely, and yet.

Writing a Conclusion

The final paragraph will summarize your main points and re-assert your main claim (from your thesis sentence). It should point out your main points, but should not repeat specific examples, and should, as always, leave a lasting impression on the reader.

The first sentence of the conclusion, therefore, should be used to restate the supporting claims argued in the body paragraphs as they relate to the thesis statement, then the next few sentences should be used to explain how the essay's main points can lead outward, perhaps to further thought on the topic. Ending the conclusion with a question, anecdote, or final pondering is a great way to leave a lasting impact.

Once you complete the first draft of your essay, it's a good idea to re-visit the thesis statement in your first paragraph. Read your essay to see if it flows well, and you might find that the supporting paragraphs are strong, but they don't address the exact focus of your thesis. Simply re-write your thesis sentence to fit your body and summary more exactly, and adjust the conclusion to wrap it all up nicely.

Practice Writing a Five-Paragraph Essay

Students can use the following steps to write a standard essay on any given topic. First, choose a topic, or ask your students to choose their topic, then allow them to form a basic five-paragraph by following these steps:

- Decide on your basic thesis , your idea of a topic to discuss.

- Decide on three pieces of supporting evidence you will use to prove your thesis.

- Write an introductory paragraph, including your thesis and evidence (in order of strength).

- Write your first body paragraph, starting with restating your thesis and focusing on your first piece of supporting evidence.

- End your first paragraph with a transitional sentence that leads to the next body paragraph.

- Write paragraph two of the body focussing on your second piece of evidence. Once again make the connection between your thesis and this piece of evidence.

- End your second paragraph with a transitional sentence that leads to paragraph number three.

- Repeat step 6 using your third piece of evidence.

- Begin your concluding paragraph by restating your thesis. Include the three points you've used to prove your thesis.

- End with a punch, a question, an anecdote, or an entertaining thought that will stay with the reader.

Once a student can master these 10 simple steps, writing a basic five-paragraph essay will be a piece of cake, so long as the student does so correctly and includes enough supporting information in each paragraph that all relate to the same centralized main idea, the thesis of the essay.

Limitations of the Five-Paragraph Essay

The five-paragraph essay is merely a starting point for students hoping to express their ideas in academic writing; there are some other forms and styles of writing that students should use to express their vocabulary in the written form.

According to Tory Young's "Studying English Literature: A Practical Guide":

"Although school students in the U.S. are examined on their ability to write a five-paragraph essay , its raison d'être is purportedly to give practice in basic writing skills that will lead to future success in more varied forms. Detractors feel, however, that writing to rule in this way is more likely to discourage imaginative writing and thinking than enable it. . . . The five-paragraph essay is less aware of its audience and sets out only to present information, an account or a kind of story rather than explicitly to persuade the reader."

Students should instead be asked to write other forms, such as journal entries, blog posts, reviews of goods or services, multi-paragraph research papers, and freeform expository writing around a central theme. Although five-paragraph essays are the golden rule when writing for standardized tests, experimentation with expression should be encouraged throughout primary schooling to bolster students' abilities to utilize the English language fully.

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- How to Find the Main Idea

- How To Write an Essay

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- How to Write a Great Essay for the TOEFL or TOEIC

- How to Write and Format an MBA Essay

- How to Structure an Essay

- Paragraph Writing

- How to Help Your 4th Grader Write a Biography

- What Is Expository Writing?

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- Definition and Examples of Body Paragraphs in Composition

- 3 Changes That Will Take Your Essay From Good To Great

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

UMGC Effective Writing Center Secrets of the Five-Paragraph Essay

Explore more of umgc.

- Writing Resources

This form of writing goes by different names. Maybe you've heard some of them before: "The Basic Essay," "The Academic Response Essay," "The 1-3-1 Essay." Regardless of what you've heard, the name you should remember is "The Easy Essay."

Once you are shown how this works--and it only takes a few minutes--you will have in your hands the secret to writing well on almost any academic assignment. Here is how it goes.

Secret #1—The Magic of Three

Three has always been a magic number for humans, from fairy tales like "The Three Little Pigs" to sayings like “third time’s a charm.” Three seems to be an ideal number for us--including the academic essay. So whenever you are given a topic to write about, a good place to begin is with a list of three. Here are some examples (three of them, of course):

Topic : What are the essential characteristics of a good parent? Think in threes and you might come up with:

- unconditional love

Certainly, there are more characteristics of good parents you could name, but for our essay, we will work in threes.

Here's a topic that deals with a controversial issue:

Topic : Should women in the military be given frontline combat duties?

- The first reason that women should be assigned to combat is equality.

- The second reason is their great teamwork.

- The third reason is their courage.

As you see, regardless of the topic, we can list three points about it. And if you wonder about the repetition of words and structure when stating the three points, in this case, repetition is a good thing. Words that seem redundant when close together in an outline will be separated by the actual paragraphs of your essay. So in the essay instead of seeming redundant they will be welcome as signals to the reader of your essay’s main parts.

Finally, when the topic is an academic one, your first goal is the same: create a list of three.

Topic: Why do so many students fail to complete their college degree?

- First, students often...

- Second, many students cannot...

- Finally, students find that...

Regardless of the reasons you might come up with to finish these sentences, the formula is still the same.

Secret #2: The Thesis Formula

Now with your list of three, you can write the sentence that every essay must have—the thesis, sometimes called the "controlling idea," "overall point," or "position statement." In other words, it is the main idea of the essay that you will try to support, illustrate, or corroborate.

Here’s a simple formula for a thesis: The topic + your position on the topic = your thesis.

Let’s apply this formula to one of our examples:

Topic: Essential characteristics of a good parent Your Position: patience, respect, love Thesis: The essential characteristics of a good parent are patience, respect, and love.

As you see, all we did was combine the topic with our position/opinion on it into a single sentence to produce the thesis: The essential characteristics of a good parent are patience, respect, and love.

In this case, we chose to list three main points as part of our thesis. Sometimes that’s a good strategy. However, you can summarize them if you wish, as in this example:

Topic: Women in combat duty in the military Your Position: They deserve it Thesis: Women deserve to be assigned combat duty in the military.

This type of thesis is shorter and easier to write because it provides the overall position or opinion without forcing you to list the support for it in the thesis, which can get awkward and take away from your strong position statement. The three reasons women deserve to be assigned combat duties--equality, teamwork, courage--will be the subjects of your three body paragraphs and do not need to be mentioned until the body paragraph in which they appear.

Secret #3: The 1-3-1 Outline

With your thesis and list of three main points, you can quickly draw a basic outline of the paragraphs of your essay. You’ll then see why this is often called the 1-3-1 essay.

- Supporting Evidence for Claim 1

- Supporting Evidence for Claim 2

- Supporting Evidence for Claim 3

The five-paragraph essay consists of one introduction paragraph (with the thesis at its end), three body paragraphs (each beginning with one of three main points) and one last paragraph—the conclusion. 1-3-1.

Once you have this outline, you have the basic template for most academic writing. Most of all, you have an organized way to approach virtually any topic you are assigned.

Our helpful admissions advisors can help you choose an academic program to fit your career goals, estimate your transfer credits, and develop a plan for your education costs that fits your budget. If you’re a current UMGC student, please visit the Help Center .

Personal Information

Contact information, additional information.

By submitting this form, you acknowledge that you intend to sign this form electronically and that your electronic signature is the equivalent of a handwritten signature, with all the same legal and binding effect. You are giving your express written consent without obligation for UMGC to contact you regarding our educational programs and services using e-mail, phone, or text, including automated technology for calls and/or texts to the mobile number(s) provided. For more details, including how to opt out, read our privacy policy or contact an admissions advisor .

Please wait, your form is being submitted.

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Guide on How to Write a 5 Paragraph Essay Effortlessly

What is a 5-paragraph Essay

5-paragraph essay is a common format used in academic writing, especially in schools and standardized tests. This type of essay is structured into five distinct sections: an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The introduction serves to present the main topic and ends with a thesis statement, which outlines the primary argument or points that will be discussed. This format is favored because it provides a clear and organized way to present information and arguments.

The three body paragraphs each focus on a single point that supports the thesis statement. Each paragraph begins with a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of the paragraph, followed by supporting details, examples, and evidence. This structured approach helps the writer stay on topic and provides the reader with a clear understanding of the arguments being made. The consistency in structure also aids in the logical flow of the essay, making it easier for the reader to follow and comprehend the writer's points.

The conclusion, the final paragraph, summarizes the main points discussed in the essay and restates the thesis in a new way. It provides closure to the discussion and reinforces the essay's main argument. The 5-paragraph essay format is an effective tool for teaching students how to organize their thoughts and present them clearly and logically. It is a foundational skill that serves as a building block for more complex writing tasks in the future.

Guide on How to Write a 5 Paragraph Essay

Writing a 5-paragraph essay becomes manageable if you follow these simple and effective tips below from our admission essay writing service :

.webp)

1. Plan Before You Write: Before you start writing, create an outline to organize your thoughts and ensure a logical flow of ideas. This will help you stay on track and cover all your points. Draft an outline with headings for the introduction, each body paragraph, and the conclusion. Under each heading, jot down the main points and supporting details.

2. Focus on Main Points : Stick to your main arguments and avoid adding unnecessary information. This keeps your essay clear and easy to understand. If your thesis is about the benefits of exercise, each body paragraph should discuss a specific benefit, such as improved health, increased energy, or better mood.

3. Maintain a Smooth Flow : Use transition words to link your paragraphs and ideas. This helps the reader follow your argument seamlessly.

Examples : "Furthermore," "In addition," "Moreover," "On the other hand," "In conclusion."

Example Sentence : "In addition to improving physical health, exercise also enhances mental well-being."

4. Provide Strong Evidence: Use facts, examples, and quotes to back up your arguments. This makes your essay more convincing and credible.

Example : "According to a study by the World Health Organization, regular physical activity can reduce the risk of chronic diseases by up to 30%."

5. Vary Your Sentence Structure : Mix short and long sentences to keep your writing engaging. This helps maintain the reader's interest and makes your essay more dynamic.

6. Proofread and Revise : Review your essay for grammar mistakes, spelling errors, and unclear sentences. Make necessary revisions to improve clarity and coherence. : After writing your essay, take a break and then read it again. This helps you spot mistakes you might have missed initially.

7. Stay Focused on Your Thesis: Ensure that all your paragraphs support your thesis statement. If your thesis is about the importance of education, every paragraph should relate to how education impacts individuals and society.

8. Manage Your Time: Allocate specific times for planning, writing, and revising your essay. This helps you stay organized and avoid last-minute stress. For example, spend 10 minutes outlining, 30 minutes writing, and 10 minutes proofreading for a 50-minute essay task.

Don't Let Essay Writing Stress You Out!

Order a high-quality, custom-written paper from our professional writing service and take the first step towards academic success!

5 Paragraph Essay Format

The five-paragraph essay format is designed to provide a clear and straightforward structure for presenting ideas and arguments. This format is broken down into an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion, each serving a specific purpose in the essay.

| Introduction 📚 | Details 📝 | Example 💡 |

|---|---|---|

| Hook: Start with a sentence that grabs the reader's attention. This could be a quote, a surprising fact, or a rhetorical question. | Background Information: Provide a brief context or background information about the topic. | Example: "Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world," said Nelson Mandela. |

| Example: In today's world, education is more important than ever for achieving success and creating opportunities. | ||

| Thesis Statement: State your main argument or point clearly. This will guide the rest of your essay. | Example: This essay will discuss the importance of education, its impact on career success, and its role in personal development. | |

| Body Paragraph 1 📄 | ||

| Topic Sentence: Introduce the first main point. | Supporting Details: Provide evidence, examples, and explanations to support the point. | Example: First and foremost, education provides individuals with the knowledge and skills necessary for career success. |

| Supporting Details: Provide evidence, examples, and explanations to support the point. | Example: For instance, studies show that individuals with higher education levels tend to have higher earning potential and more job opportunities. | |

| Body Paragraph 2 📄 | ||

| Topic Sentence: Introduce the second main point. | Supporting Details: Provide evidence, examples, and explanations to support the point. | Example: Additionally, education fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills. |

| Supporting Details: Provide evidence, examples, and explanations to support the point. | Example: Through coursework and real-world applications, students learn to analyze situations, make informed decisions, and solve complex problems. | |

| Body Paragraph 3 📄 | ||

| Topic Sentence: Introduce the third main point. | Supporting Details: Provide evidence, examples, and explanations to support the point. | Example: Finally, education plays a crucial role in personal development and growth. |

| Supporting Details: Provide evidence, examples, and explanations to support the point. | Example: Education exposes individuals to diverse perspectives and ideas, encouraging them to develop a broader understanding of the world and their place in it. | |

| Conclusion 🎓 | ||

| Restate Thesis: Summarize the main argument in a new way. | Summarize Main Points: Briefly recap the points discussed in the body paragraphs. | Closing Thought: End with a final thought or call to action. |

| Example: In conclusion, education is essential for career success, critical thinking, and personal growth. | Example: By providing knowledge and skills, fostering problem-solving abilities, and promoting personal development, education lays the foundation for a successful and fulfilling life. | Example: Investing in education is investing in a brighter future for individuals and society as a whole. |

Types of 5 Paragraph Essay

There are several types of five-paragraph essays, each with a slightly different focus or purpose. Here are some of the most common types of five-paragraph essays:

.webp)

- Narrative essay : A narrative essay tells a story or recounts a personal experience. It typically includes a clear introductory paragraph, body sections that provide details about the story, and a conclusion that wraps up the narrative.

- Descriptive essay: A descriptive essay uses sensory language to describe a person, place, or thing. It often includes a clear thesis statement that identifies the subject of the description and body paragraphs that provide specific details to support the thesis.

- Expository essay: An expository essay offers details or clarifies a subject. It usually starts with a concise introduction that introduces the subject, is followed by body paragraphs that provide evidence and examples to back up the thesis, and ends with a summary of the key points.

- Persuasive essay: A persuasive essay argues for a particular viewpoint or position. It has a thesis statement that is clear, body paragraphs that give evidence and arguments in favor of it, and a conclusion that summarizes the important ideas and restates the thesis.

- Compare and contrast essay: An essay that compares and contrasts two or more subjects and looks at their similarities and differences. It usually starts out simply by introducing the topics being contrasted or compared, followed by body paragraphs that go into more depth on the similarities and differences, and a concluding paragraph that restates the important points.

Don’t forget, you can save time and reduce the stress of academic assignments by using our research paper writing services to help you.

5 Paragraph Essay Example Topics

Choosing a specific and interesting topic can make your essay stand out. Here are 20 more engaging essay topics that provide a good starting point for your 5-paragraph paper:

- Why Is Recycling Important for Our Planet?

- The Day I Met My Best Friend

- How Does Playing Sports Benefit Children?

- What Are the Challenges of Being a Teenager Today?

- A Time I Made a Difficult Decision

- My Most Embarrassing Moment

- How Can We Encourage People to Read More?

- How I Spent My Last Summer Vacation

- The Best Gift I Ever Received

- What Makes a Good Friend?

- My Experience Learning a New Skill

- How Do Video Games Affect Our Brains?

- Why Is It Important to Learn About Different Cultures?

- The Day I Got My First Pet

- How Can Schools Better Prepare Students for the Future?

- An Adventure I Will Never Forget

- A Time I Helped Someone in Need

- What Are the Pros and Cons of Remote Work?

- The Most Interesting Person I Have Met

- How Does Peer Pressure Affect Our Decisions?

General Grading Rubric for a 5 Paragraph Essay

The following is a general grading rubric that can be used to evaluate a five-paragraph essay:

| Criteria 📊 | Details 📝 |

|---|---|

Based on the points discussed, your paper needs to show a good grasp of the topic, clear structure, strong writing skills, and critical thinking. Teachers use this rubric to assess essays comprehensively and give feedback on what you do well and where you can improve. If you want to simplify meeting your professors' expectations, you can buy an essay from our experts and see how it can ease your academic life!

Five Paragraph Essay Examples

Final thoughts.

Writing a five-paragraph essay might seem challenging at first, but it doesn't have to be difficult. By following these simple steps and tips, you can break down the process into manageable parts and create a clear, concise, and well-organized essay.

Start with a strong thesis statement, use topic sentences to guide your paragraphs, and provide evidence and analysis to support your ideas. Remember to revise and proofread your work to ensure it is error-free and coherent. With time and practice, you'll be able to write a five-paragraph essay with ease and confidence. Whether you're writing for school, work, or personal projects, these skills will help you communicate your ideas effectively!

Ready to Take the Stress Out of Essay Writing?

Order your 5 paragraph essay today and enjoy a high-quality, custom-written paper delivered promptly

Is a 5 Paragraph Essay 500 Words?

How long is a five-paragraph essay, how do you write a 5 paragraph essay.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

- Updated definition, writing tips and format

- Added FAQs and topics

- Secrets of the Five-Paragraph Essay | UMGC Effective Writing Center . (n.d.). University of Maryland Global Campus. https://www.umgc.edu/current-students/learning-resources/writing-center/writing-resources/writing/secrets-five-paragraph-essay#:~:text=The%20five%2Dparagraph%20essay%20consists

- Outline for a Five-Paragraph Essay . (n.d.). https://www.bucks.edu/media/bcccmedialibrary/pdf/FiveParagraphEssayOutlineJuly08_000.pdf

%202.webp)

- How to Order

Essay Writing Guide

Five Paragraph Essay

A Guide to Writing a Five-Paragraph Essay

10 min read

People also read

An Easy Guide to Writing an Essay

A Complete 500 Word Essay Writing Guide

A Catalog of 370+ Essay Topics for Students

Common Types of Essays - Sub-types and Examples

Essay Format: A Basic Guide With Examples

How to Write an Essay Outline in 5 Simple Steps

How to Start an Essay? Tips for an Engaging Start

A Complete Essay Introduction Writing Guide With Examples

Learn How to Write an Essay Hook, With Examples

The Ultimate Guide to Writing Powerful Thesis Statement

20+ Thesis Statement Examples for Different Types of Essays?

How to Write a Topic Sentence: Purpose, Tips & Examples

Learn How to Write a Conclusion in Simple Steps

Transition Words For Essays - The Ultimate List

4 Types of Sentences - Definition & Examples

Writing Conventions - Definition, Tips & Examples

Essay Writing Problems - 5 Most Paralyzing Problems

Tips On How to Make an Essay Longer: 15 Easy Ways

How to Title an Essay Properly- An Easy Guide

1000 Word Essay - A Simple Guide With Examples

How To Write A Strong Body Paragraph

The five-paragraph essay is a fundamental writing technique, sometimes called "The Basic Essay," "The Academic Response Essay," or the "1-3-1 Essay."

No matter what you call it, understanding this format is key to organizing your thoughts clearly and effectively. Once you learn the structure, writing essays for any academic subject becomes much easier.

In this guide, we'll walk you through each part of the five-paragraph essay, showing you how to create strong introductions, develop your ideas in body paragraphs, and conclude with impact. With these tips, you'll be ready to tackle any writing assignment with confidence.

So let’s get started!

- 1. What is a 5 Paragraph Essay?

- 2. Steps to Write a Five-Paragraph Essay

- 3. 5 Paragraph Essay Examples

- 4. 5 Paragraph Essay Topics

What is a 5 Paragraph Essay?

A five-paragraph essay is a structured format of essay writing that consists of one introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and one concluding paragraph. It is also known by several other names, including Classic Essay, Three-Tier Essay, Hamburger Essay, and One-Three-One Essay.

This type of essay format is commonly taught in middle and high school and is mainly used for assignments and quick writing exercises. The five-paragraph essay is designed to help writers organize their thoughts clearly and logically, making it easier for readers to follow the argument or narrative.

The structure is popular because it works for almost all types of essays . Whether you're writing a compare and contrast or argumentative essay , this format helps you organize your thoughts clearly. It's best for topics that can be explained well in just five paragraphs.

Steps to Write a Five-Paragraph Essay

Writing a five-paragraph essay involves clear and structured steps to effectively communicate your ideas. Here’s how to do it:

Step 1: Understand the Assignment

Knowing your topic before you start writing is really important. The first thing you need to do is figure out what your essay is supposed to be about. This is usually called the thesis statement or main idea.

If your teacher didn’t give you a specific topic, you should pick something that you can talk about enough to fill five paragraphs.

Here are some tips to help you understand your topic:

- Think about what interests you or something you already know a bit about. It’s easier to write when you care about the topic.

- Read through the assignment carefully to see if there are any specific instructions or questions you need to answer.

- If you’re not sure about your topic, try talking it over with someone else—a friend, family member, or even your teacher—to get some ideas. You can also find some good essay ideas by checking out our essay topics blog.

Once you’ve picked a topic, take a moment to write down what you already know about it. This can help you see if you need to do more research or if you have enough to start writing. Understanding your topic well from the start makes the writing process much smoother.

Step 2: Outline Your Essay

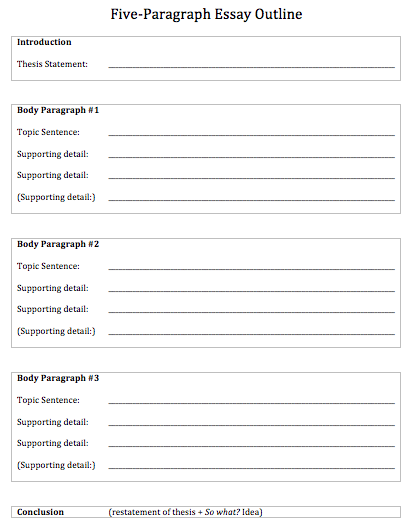

Creating an outline is like making a plan for your essay before you start writing. An essay outline helps you organize your ideas and decide what you want to say in each part of your essay.

Your outline acts as a guide that reveals any gaps or the need for rearranging ideas. It functions like a roadmap that guides you through writing your essay, so it should be easy for you to understand and follow.

To create a good outline think about the most important things you want to say about your topic. These will be your main ideas for each body paragraph .

Here’s a simple 5-paragraph essay outline template:

: Start with an engaging opening sentence. : Give context about your topic. : State your main argument clearly. : Introduce your first main idea. : Provide evidence or examples. : Connect to the next paragraph. : Introduce your second main idea. : Provide evidence or examples. : Connect to the next paragraph. : Introduce your third main idea. : Provide evidence or examples. : Connect to the conclusion. : Summarize your main argument. : Recap your main points. : End with a final idea related to your topic. |

Step 3: Write the Introduction

Writing the essay introduction is like inviting someone into your essay—it sets the tone and tells them what to expect. Here’s how to craft a strong introduction:

- First, start with a hook . This could be something surprising or interesting, like a shocking fact or a thought-provoking question. It’s meant to grab your reader's attention right away, making them curious about what you’re going to say next.

- Next, provide some background information about your topic. This helps your reader understand the context of your essay. Think of it like setting the stage before a play—you want to give enough information so that your audience knows what’s going on.

- Finally, write your thesis statement . This is the main point of your essay summed up in one clear sentence. It tells your reader what you’re going to argue or explain throughout the rest of your essay.

For Example:

For the exercise essay, an introduction could start with: "Did you know that regular physical activity not only keeps you fit but also enhances your mental well-being? Exercise is more than just a way to stay in shape—it's a key to a healthier, happier life." |

Step 4: Develop Body Paragraphs

Developing body paragraphs is like building the main part of your essay—it’s where you explain your ideas in detail. Here’s how to do it effectively:

First, each body paragraph should have one main idea that supports your thesis. This main idea is introduced in the topic sentence , which is like a mini-thesis for that paragraph. It tells your reader what the paragraph is going to be about.

After you introduce your main idea, you need to support it with evidence. These could be examples, facts, or explanations that help prove your point. Imagine you’re explaining your idea to a friend—you’d give reasons and examples to make them understand and believe what you’re saying.

Step 5: Transition Between Paragraphs

Smooth transitions between paragraphs are like bridges that connect one idea to the next in your essay. They help your reader follow your thoughts easily and see how each point relates to the overall argument.

To use transitions effectively, think about how each paragraph connects to the next. If you're moving from talking about one idea to another that contrasts or supports it, use transition words like "however," "similarly," or "on the other hand." These words signal to your reader that you're shifting to a new point while still maintaining the flow of your argument.

For example, if you're discussing the physical benefits of exercise in one paragraph and want to transition to its mental benefits in the next, you might write: "After discussing the physical benefits of exercise, it's important to consider its impact on mental well-being as well." |

Step 6: Write the Conclusion

Writing an essay conclusion is like wrapping up a conversation. You want to remind the reader of what you've discussed and leave them with something to think about. Here’s how to do it:

- Start by summarizing the main points of your essay. Go over the key ideas from each of your body paragraphs. This reminds the reader of what you’ve covered without going into too much detail again.

- Next, restate your thesis in different words. This helps reinforce your main argument and shows that you’ve supported it throughout your essay.

- Finally, end with a final thought or recommendation . This could be a call to action, a suggestion, or a thought-provoking statement that leaves the reader thinking about your topic.

For Example :

"In conclusion, incorporating regular exercise into your routine not only improves your physical fitness but also enhances your overall quality of life. Start small, stay consistent, and reap the rewards of a healthier, happier you." |

Step 7: Revise and Edit

Revising and editing your essay is like giving it a final polish to make sure everything is clear and correct. Here are some tips for revising and editing:

- Take a Break: After writing your essay, take a short break before you start revising. This helps you see your work with fresh eyes.

- Read Aloud: Reading your essay out loud can help you catch errors and awkward sentences.

- Ask for Feedback: Sometimes, another person can spot mistakes you’ve overlooked. Ask a friend or family member to read your essay and give feedback.

- Be Patient: Don’t rush the revision process. Take your time to ensure your essay is the best it can be.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job

5 Paragraph Essay Examples

Here is some free 5-paragraph essay example pdfs for you to download and get an idea of the format of this type of essay.

5 Paragraph Essay Benefits of Exercise

5 Paragraph Essay on Technology

5 Paragraph Essay on What Makes A Good Friend

5 Paragraph Essay on Cell Phones in School

5 Paragraph Essay on Climate Change

5 Paragraph Essay about Sports

5 Paragraph Essay about Cats

5 Paragraph Essay about Love

5 Paragraph Essay Topics

Here are some common and trending topics for 5-paragraph essays:

- Discuss needed changes to improve the education system.

- Analyze the effects of globalization on society.

- Explore ways to promote sustainable practices.

- Address issues of healthcare equity.

- Examine progress and challenges in gender equality.

- Discuss the impact of immigration policies.

- Explore needed changes in the criminal justice system.

- Analyze ethical dilemmas in science and medicine.

- Discuss the effects of global pandemics.

- Explore the importance of diversity and inclusion.

So, learning the five-paragraph essay isn't just about school, it's about building strong communication skills that will serve you well in any writing task. By following this structured approach—you'll be writing with confidence in no time.

Now that you've got the basics down, don't hesitate to put them into practice. Whether you're tackling assignments for school or exploring new topics on your own, these skills will help you organize your thoughts.

And if you ever need a helping hand, visit our website and request " write my essay ." Our expert writers are ready to assist with any type of assignment, from college essays to research papers. Don't wait—take your writing to the next level today!

Frequently Asked Questions

How long is a five-paragraph essay.

A five-paragraph essay typically ranges from 500 to 1000 words in total length. The essay word count may vary based on the specific requirements provided by the assignment or academic standards set by the instructor.

Is a 5 paragraph essay 500 words?

Not necessarily. The word count of a five-paragraph essay can vary widely depending on the topic, level of detail in each paragraph, and specific instructions provided by the teacher or professor. While some five-paragraph essays might be around 500 words, others could be shorter or longer.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Nova Allison is a Digital Content Strategist with over eight years of experience. Nova has also worked as a technical and scientific writer. She is majorly involved in developing and reviewing online content plans that engage and resonate with audiences. Nova has a passion for writing that engages and informs her readers.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

- Essay Guides

- Basics of Essay Writing

- How to Write a 5 Paragraph Essay: Guide with Structure, Outline & Examples

- Speech Topics

- Essay Topics

- Other Essays

- Main Academic Essays

- Research Paper Topics

- Basics of Research Paper Writing

- Miscellaneous

- Chicago/ Turabian

- Data & Statistics

- Methodology

- Admission Writing Tips

- Admission Advice

- Other Guides

- Student Life

- Studying Tips

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Academic Writing Tips

- Basics of Dissertation & Thesis Writing

- Research Paper Guides

- Formatting Guides

- Basics of Research Process

- Admission Guides

- Dissertation & Thesis Guides

How to Write a 5 Paragraph Essay: Guide with Structure, Outline & Examples

Table of contents

Use our free Readability checker

You may also like

A 5-paragraph essay is a common assignment in high school and college, requiring students to follow a standard structure. This essay format consists of five main components: an introduction paragraph, followed by 3 body paragraphs, and a final paragraph. Each paragraph serves a specific purpose and contributes to the overall coherence and organization of the essay.

Since this is one of the most popular assignments teachers give, you should be prepared to write using a five paragraph essay format. From structure and outline template to actual examples, we will explain how to write a 5 paragraph essay with ease. Follow our suggestions and you will be able to nail this task.

Our team of experienced writers is ready to provide you with high-quality, custom-written essays tailored to your specific requirements. Whether you're struggling with a complex topic or short on time, our reliable service ensures timely delivery and top-notch content. Buy essays online and forget about struggles.

FAQ About Five-Paragraph Essays

1. how long is a 5-paragraph essay.

A five-paragraph essay typically ranges from 300 to 500 words, depending on the topic and type of paper. It's important to consider the length of your essay when determining how much information you want to include in each paragraph. For shorter essays, it is best to stick to one main point per paragraph so that your essay remains concise and focused.

2. What is a 5-paragraph format?

The five-paragraph essay format is a classic structure used to organize essays and persuasive pieces. It consists of an introduction (which includes your thesis statement), 3 body paragraphs that explain each point, and a conclusion which sums up your fundamental ideas. Each paragraph should feature one main aspect, with supporting evidence discovered during research.

3. How to start a 5-paragraph essay?

The best way to start a five-paragraph essay is by writing an engaging introduction that contains your thesis statement. Your first paragraph should provide readers with some context as well as introduce your main argument. Make sure to cover at least 2 or 3 points in your thesis statement so that you have something to elaborate on further in your text.

Daniel Howard is an Essay Writing guru. He helps students create essays that will strike a chord with the readers.

A 5-paragraph essay is as simple as it sounds: an essay composed of five paragraphs. It's made up of five distinct sections, namely an introduction , 3 body paragraphs and a concluding section . However, a 5 paragraph essay goes beyond just creating 5 individual sections. It's a method of organizing your thoughts and making them interconnected.

Despite its straightforward 5-paragraph format, there's more going on beneath the surface. When writing a 5-paragraph essay, you should address the main objective of each part and arrange every section properly.

Let’s learn about each of these sections more in detail.

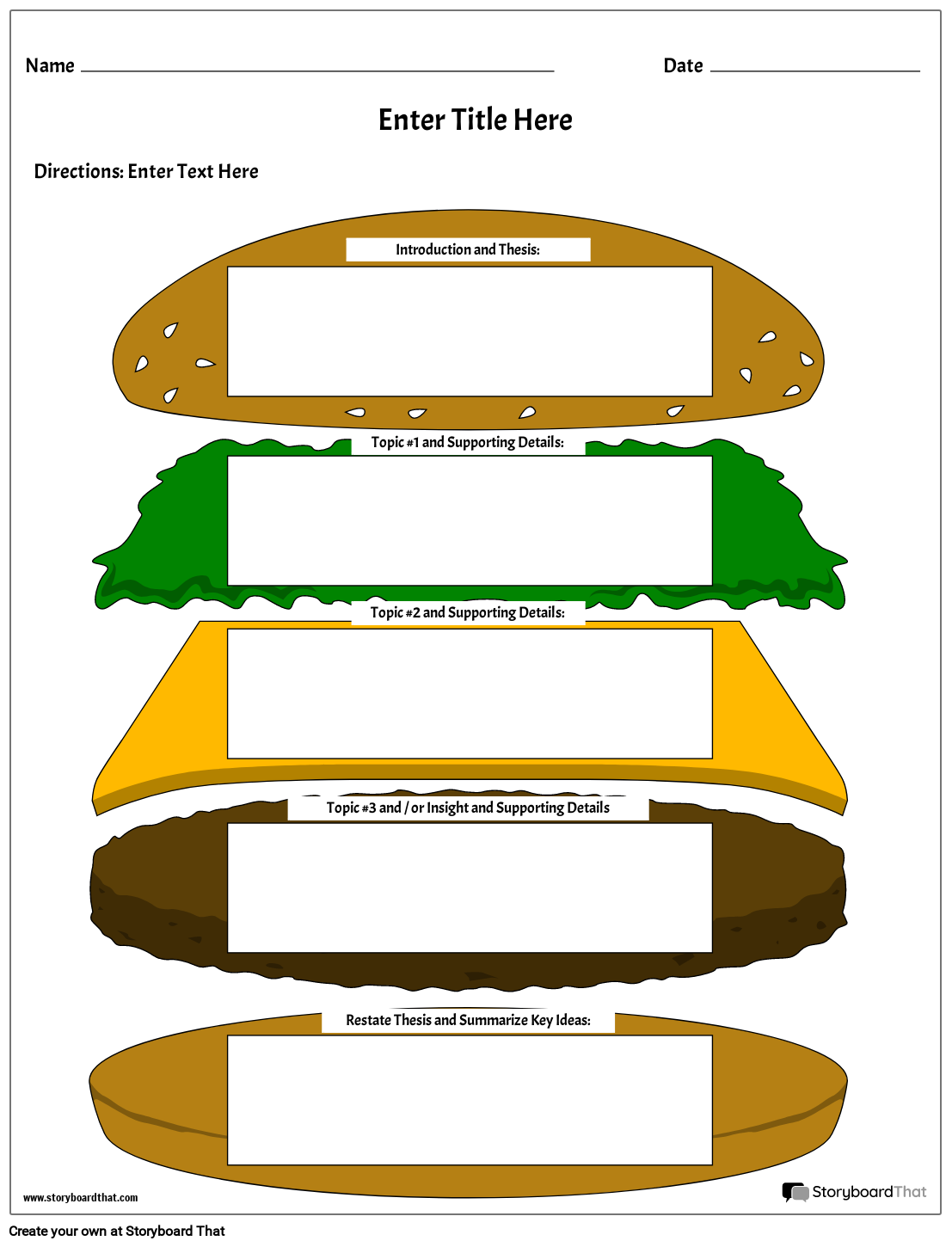

A five-paragraph essay structure is often compared to a sandwich that has 3 distinct layers:

As you can notice, each of these sections plays an important role in creating the overall piece.

Imagine heading out for a journey in the woods without a map. You'd likely find yourself wandering aimlessly, right? Similarly, venturing into writing an essay without a solid essay outline is like stepping into the academic jungle without a guide. Most high school and college students ignore this step for the sake of time. But eventually they end up writing a five-paragraph essay that lacks a clear organization.

It’s impossible to figure out how to write a 5-paragraph essay without having a well-arranged outline in front. Here’s a five-paragraph essay outline example showing subsections of each major part.

5 Paragraph Essay Outline Example

When creating an outline for 5-paragraph essay, begin by identifying your topic and crafting a thesis statement. Your thesis statement should encapsulate your main argument. Identify 3 ideas that support your thesis to lay the foundation of your body section. For each point, think about examples and explanations that will help convince the reader of your perspective. Finally, plan what you will include in the concluding section.

Throughout this process, remember that clarity and organization are key. While it's not necessary for your 5-paragraph outline to be "perfect", it is indeed important for it to be arranged logically.

Below, you can spot an example of an outline created based on these instructions.

There is nothing difficult about writing a 5-paragraph essay. All you need to do is to just start creating the first sentence. But for most of us, it;s easier said than done. For this reason, we prepared informative step-by-step guidelines on how to write a 5-paragraph essay that your teacher will like.

As we navigate these stages, remember that good writing isn't a destination, it's a process. So grab your notebook (or laptop) and let's dive into the art of crafting your five-paragraph essay.

>> Learn more: How to Write an Essay

The initial step is to make sure you have a full grasp of your assignment instructions. How well you understand the given guidelines can either make or break your 5-paragraph essay. Take a few minutes to read through your instructor’s requirements and get familiar with what you're supposed to do:

Understanding these crucial details will help you remain on course.

Now that you have a good idea of your assignment, it’s time to roll up your sleeves and start researching. Spend some quality time gathering relevant resources to get acquainted with the discussed topic. Make sure you don;t refer to outdated resources. Always give a preference to credible, recent sources.

Read these sources carefully and jot down important facts – this is what will form the basis of your essay's body section. Also, you will need to save the online sources to cite them properly.

We can’t stress enough: your thesis statement will guide your entire essay. Write 1-2 sentences that convey your underlying idea. Keep in mind that your thesis must be succinct. There is no need for long introductions or excessive details at this point.

A five-paragraph essay outline shows how your paper will be arranged. This visual structure can be represented using bullet points or numbers. You can come up with another format. But the main idea is to prepare a plan you are going to stick to during the writing process.

Did you know that you can send an outline to professionals and have your essay written according to the structure. Order essay from academic experts should you need any assistance.

To start a 5-paragraph essay, compose an attention-grabbing statement, such as a question or fact. This is also known as an essay hook – an intriguing opening sentence. Its goal is to spark curiosity and draw your reader into your topic.

Next, you need to establish a background and show what;s under the curtains. Write 1-2 contextual sentences helping your reader understand the broad issue you're about to discuss.

Your 5-paragraph essay introduction won’t be complete without a thesis statement – the heart of your writing. This 1 or 2-sentence statement clearly expresses the main point you will develop throughout your essay. Make sure your thesis is specific, debatable, and defensible.

>> Read more: How to Start an Essay

A body section of a standard 5-paragraph essay layout comprises 3 paragraphs. Each body paragraph should contain the most important elements of the discussion:

Begin your body paragraph by introducing a separate aspect related to your thesis statement. For example, if you are writing about the importance of physical activity, your body paragraph may start this way:

Don’t just make a bold statement. You will need to expand on this idea and explain it in detail. You should also incorporate facts, examples, data, or quotes that back up your topic sentence. Your evidence should sound realistic. Try to draw the examples from personal experience or recent news. On top of that, you should analyze how this evidence ties back to your overall argument.

It’s not a good idea to finish your body paragraph just like that. Add essay transition words to keep your five-paragraph paper cohesive.

>> Read more: How to Write a Body Paragraph

Wrapping up your 5-paragraph essay might seem like a breeze after developing your introductory and body parts. Yet, it's crucial to ensure your conclusion is equally impactful. Don't leave it to the reader to join the dots – restate your thesis statement to reinforce your main argument. Follow this by a brief recap of the 2-3 key points you've discussed in your essay.

The last taste should be the best, so aim to end your 5-paragraph essay on a high note. Craft a compelling closing sentence that underscores the importance of your topic and leaves your reader considering future implications.

>> Learn more: How to Write a Conclusion for an Essay

Your 5-paragraph essay should be up to scratch now. However, double-check your work for any errors or typos. It's worth revising your essay at least twice for maximum impact. Our practice shows that revising your essay multiple times will help you refine the arguments, making your piece more convincing.

As you proofread, make sure the tone is consistent, and each sentence contributes something unique to the overall point of view. Also, check for spelling and grammar errors.

Once you're happy with your 5-paragraph essay, submit it to your teacher or professor.

Students can ease their life by exploring a sample five paragraph essay example shared by one the writers. Consider buying a college essay if you want your homework to be equally good.

Here’re some bonus tips on how to write a good 5-paragraph essay:

Writing a five-paragraph essay may seem challenging at first, but with practice and determination it can become a piece of cake. Don’t forget to use your secret power – an outline, so that you have a clear idea of what points to cover in each paragraph. Make sure that you stick to the right format and cite your sources consistently. With these tips and 5 paragraph essay examples, you will be able to write an effective piece.

If any questions pop out, do not hesitate to leave the comments below or contact our professional writing service for expert assistance with your “ write an essay for me ” challenge.

- Introduction: This initial paragraph should introduce the main topic and tell what will be discussed further in the essay.

- Body: This part consists of three body paragraphs, each focusing on a specific aspect of your subject.

- Conclusion: The final paragraph rounds off the main points and offers key takeaways.

- Hook: Spark the reader's interest.

- Brief background: Provide a general context or background.

- Thesis statement: State the main argument or position.

- Topic sentence: Introduce the main point of this paragraph.

- Supporting evidence/example 1: Provide data, examples, quotes, or anecdotes supporting your point.

- Analysis: Explain how your evidence supports your thesis.

- Transition: Tie the paragraph together and link to the next paragraph.

- Supporting evidence/example 2 : Provide further supporting evidence.

- Analysis: Discuss how the evidence relates back to your thesis.

- Transition: Summarize the point and smoothly shift to the next paragraph.

- Topic sentence: Present the main idea of this paragraph.

- Supporting evidence/example 3: Offer additional support for your thesis.

- Analysis: Show how this backs up your main argument.

- Transition: Sum up and signal the conclusion of the body section.

- Thesis reiteration: Revisit your main argument accounting for the evidence provided.

- Summary: Briefly go over the main points of your body paragraphs.

- Final thoughts: Leave the reader with a parting thought or question to ponder.

- What’s your topic? Do you need to choose one yourself?

- What essay type do you need to write – argumentative , expository or informative essay ?

- What’s your primary goal – persuade, analyze, descibe or inform?

- How long should an essay be ? Is there any specific word count?

- Topic sentence

- Detailed explanation

- Supporting evidence from credible sources

- Further exploration of examples

- Transition.

- Be clear and concise Avoid fluff and filler. Every sentence should contribute to your argument or topic.

- Keep paragraphs focused Each paragraph should be dedicated to an individual point or idea.

- Use strong evidence To support your points, use solid evidence. This could be statistics, research findings, or relevant quotes from experts.

- Use active voice Active voice makes writing direct and dynamic. It puts the subject of the sentence in the driver's seat, leading the action.

- Avoid first-person pronouns To maintain a formal, academic tone, try to avoid first-person pronouns (I, me, my, we, our). First-person pronouns are acceptable only when writing a narrative essay , personal statement or college application essay .

What Is a 5-Paragraph Essay: Definition

5-paragraph essay structure , 5-paragraph essay outline & template example , how to write a 5-paragraph essay outline , how to write a 5 paragraph essay step-by-step, 1. understand the task at hand , 2. research and take notes , 3. develop your thesis statement, 4. make an outline , 5. write an introduction paragraph , 6. create a body part , 7. write a concluding paragraph , 8. review and revise, 5 paragraph essay example, extra 5-paragraph writing tips , final thoughts on how to write a five paragraph essay .

A staggering report by the World Health Organization reveals that poor diet contributes to more disease than physical inactivity, alcohol, and smoking combined. In our fast-paced world, convenience often trumps health when it comes to food choices. With an alarming rise in obesity and diet-related illnesses, a closer look at our eating habits is more critical than ever. For this reason, adopting a healthy diet is essential for individual health, disease prevention, and overall wellbeing.

Regular exercise is essential for maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

First and foremost, a healthy diet plays a pivotal role in maintaining individual health and vitality. A balanced diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, provides the essential nutrients our bodies need to function effectively. A research study by the American Heart Association found that individuals who adhered to a healthy eating pattern had a 25% lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease. This data emphasizes that a proper diet is not just about staying in shape. It directly affects critical health outcomes, impacting our susceptibility to serious health conditions like heart disease. While the implications of diet on personal health are substantial, the preventative power of healthy eating against disease is equally noteworthy, as we shall explore next.

As was outlined in this essay, a balanced diet isn't just a lifestyle choice, but an essential tool for maintaining individual health, preventing disease, and promoting overall wellbeing. Healthy eating directly affects our personal health, its power in disease prevention, and how it contributes to a sense of wellness. What we consume profoundly impacts our lives. Therefore, a commitment to healthy eating isn't merely an act of self-care; it's a potent declaration of respect for the life we've been given.

English Current

ESL Lesson Plans, Tests, & Ideas

- North American Idioms

- Business Idioms

- Idioms Quiz

- Idiom Requests

- Proverbs Quiz & List

- Phrasal Verbs Quiz

- Basic Phrasal Verbs

- North American Idioms App

- A(n)/The: Help Understanding Articles

- The First & Second Conditional

- The Difference between 'So' & 'Too'

- The Difference between 'a few/few/a little/little'

- The Difference between "Other" & "Another"

- Check Your Level

- English Vocabulary

- Verb Tenses (Intermediate)

- Articles (A, An, The) Exercises

- Prepositions Exercises

- Irregular Verb Exercises

- Gerunds & Infinitives Exercises

- Discussion Questions

- Speech Topics

- Argumentative Essay Topics

- Top-rated Lessons

- Intermediate

- Upper-Intermediate

- Reading Lessons

- View Topic List

- Expressions for Everyday Situations

- Travel Agency Activity

- Present Progressive with Mr. Bean

- Work-related Idioms

- Adjectives to Describe Employees

- Writing for Tone, Tact, and Diplomacy

- Speaking Tactfully

- Advice on Monetizing an ESL Website

- Teaching your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation

- Teaching Different Levels

- Teaching Grammar in Conversation Class

- Members' Home

- Update Billing Info.

- Cancel Subscription

- North American Proverbs Quiz & List

- North American Idioms Quiz

- Idioms App (Android)

- 'Be used to'" / 'Use to' / 'Get used to'

- Ergative Verbs and the Passive Voice

- Keywords & Verb Tense Exercises

- Irregular Verb List & Exercises

- Non-Progressive (State) Verbs

- Present Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Present Simple vs. Present Progressive

- Past Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Subject Verb Agreement

- The Passive Voice

- Subject & Object Relative Pronouns

- Relative Pronouns Where/When/Whose

- Commas in Adjective Clauses

- A/An and Word Sounds

- 'The' with Names of Places

- Understanding English Articles

- Article Exercises (All Levels)

- Yes/No Questions

- Wh-Questions

- How far vs. How long

- Affect vs. Effect

- A few vs. few / a little vs. little

- Boring vs. Bored

- Compliment vs. Complement

- Die vs. Dead vs. Death

- Expect vs. Suspect

- Experiences vs. Experience

- Go home vs. Go to home

- Had better vs. have to/must

- Have to vs. Have got to

- I.e. vs. E.g.

- In accordance with vs. According to

- Lay vs. Lie

- Make vs. Do

- In the meantime vs. Meanwhile

- Need vs. Require

- Notice vs. Note

- 'Other' vs 'Another'

- Pain vs. Painful vs. In Pain

- Raise vs. Rise

- So vs. Such

- So vs. So that

- Some vs. Some of / Most vs. Most of

- Sometimes vs. Sometime

- Too vs. Either vs. Neither

- Weary vs. Wary

- Who vs. Whom

- While vs. During

- While vs. When

- Wish vs. Hope

- 10 Common Writing Mistakes

- 34 Common English Mistakes

- First & Second Conditionals

- Comparative & Superlative Adjectives

- Determiners: This/That/These/Those

- Check Your English Level

- Grammar Quiz (Advanced)

- Vocabulary Test - Multiple Questions

- Vocabulary Quiz - Choose the Word

- Verb Tense Review (Intermediate)

- Verb Tense Exercises (All Levels)

- Conjunction Exercises

- List of Topics

- Business English

- Games for the ESL Classroom

- Pronunciation

- Teaching Your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation Class

Template for 5-Paragraph Essay Outline

Essay Template Description :

It's important that students write an outline before they begin their essay writing. A solid outline is key to ensuring students follow the standard essay-writing structure and stay on topic.

This is a simple template I have my students complete before they begin writing their five-paragraph academic essay.

The essay template includes sections for the following.

- Thesis statement

- Supporting Detail

- I have put the third supporting detail section in each body paragraph in brackets , since it may not be needed if the first two points support the topic sentence sufficiently (this is my opinion).

- I have not put a blank field for the conclusion section, since the student is merely meant to restate the thesis statement in a fresh way and include a So What? idea that indicates why the topic is important.

Feel free to edit the essay template as you'd like.

Essay Template Download : five-paragraph-essay-outline-template.docx

Essay Template Preview :

- Matthew Barton / Creator of Englishcurrent.com

EnglishCurrent is happily hosted on Dreamhost . If you found this page helpful, consider a donation to our hosting bill to show your support!

9 comments on “ Template for 5-Paragraph Essay Outline ”

Thank you. Love this template for my students.

Thank you. I also love this template for my students

Thank you this template is very good..and I understand now

Thank you for the outline…. would you consider providing examples of topics ? Just a thought… Once again, thank you

Here are some topics you could write an essay on: https://www.englishcurrent.com/speaking/discussion-speech-topics-esl/

i think it is very good. but like someone else said would you give more examples, but thank you verry much

so this is where my teacher gets her lesson plans. XD thanks this will help when i constantly lose my work.

This is a great template for 5-paragraph essay outlines. It is easy to follow and provides a good starting point for writing your own essays.

They are over 100 fields of fun and exciting types of science including Biology, Archeology chemistry and SO much more. However, the one field of science that really fascinates me, is Astronomy. Ever since I was like six years old I was always so curios about our world, the other planets, black holes, and how things worked and formed in space, which is what really got me in to space. Then I realized there were types of scientist that study this particular branches of science, and they are called Astronomers. Astronomy is defined as the celestial objects, space, and the physical world as a whole. Astronomy is actually one of the OLDEST fields of science. Through out the years, people have utilized astronomy to learn about the universe, our own planet, and even make predictions about life its self. Understanding astronomy requires a great understanding of it’s origins, and the numerous groups and cultures that used it, which is why astronomers usually work for university’s or research institutions. In order to succeed in Astronomy you will need a PHD in physics and math, analytical thinking skills and the ability to think clearly using logic and reasoning. Somethings that i find inserting about Astronomy is the physics behind it and like how things are formed/created, like stars, black holes, the Big-Bang theory, galaxy’s, and so much more. Last but mot least, Astronomy actually makes a huge deference in our would because with out Astronomers to build up theory’s and Laws, there is so much stuff that we would not know, and will be left a mystery. In addition, Even our ideas about the future of Earth were shaped by astronomers’ observations of the runaway global greenhouse effect on Venus — and what it meant for climate change on our own planet. We have also been exposed to Astronomy since birth as it determines our Zodiac signs.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subject Material

How to Write a Five-Paragraph Essay

The five-paragraph essay is often assigned to students to help them in this process. A good five-paragraph essay is a lot like a triple-decker burger, and it is therefore often called the hamburger essay. It requires a clear introduction and conclusion (the top and bottom bun) that hold the main body of the essay (the burger and all the juicy stuff) in place.

Before you start writing an essay, you need to get organised. Read through the task you are given several times, underlining important words that tell you what you are expected to do. Pay special attention to the verbs in the task you are given ('discuss', 'summarise', 'give an account of', 'argue'…). Make sure you do what you are asked and that you answer the whole question, not just parts of it.

Introduction

The introduction to a text is extremely important. A good introduction should accomplish three things:

- Firstly, try to capture the reader’s interest and create a desire to read on and learn more. There are many ways to achieve this. For example, you can start with a relevant quotation from a famous person or a short anecdote. You could also present some interesting statistics, state a startling fact, or simply pose a challenging question.

- Secondly, provide the reader with the necessary information to understand the main body of the text. Explain what the paper is about and why this topic is important. What is the specific focus of this paper? Include background information about your topic to establish its context.

- Thirdly, present your approach to the topic and your thesis statement. The thesis statement is the main idea of the essay expressed in a single sentence. Make sure your thesis statement comes out clearly in your introduction.

The body of the essay consists of three paragraphs, each limited to one idea that supports your thesis. Each paragraph should have a clear topic sentence: a sentence that presents the main idea of the paragraph. The first paragraph should contain the strongest argument and the most significant examples, while the third paragraph should contain the weakest arguments and examples. Include as much explanation and discussion as is necessary to explain the main point of the paragraph. You should try to use details and specific examples to make your ideas clear and convincing.

In order to create a coherent text, you must avoid jumping from one idea to the next. Always remember: one idea per paragraph. A good essay needs good transitions between the different paragraphs. Use the end of one paragraph and/or the beginning of the next to show the relationship between the two ideas. This transition can be built into the topic sentence of the next paragraph, or it can be the concluding sentence of the first.

You can also use linking words to introduce the next paragraph. Examples of linking words are: in fact, on the whole, furthermore, as a result, simply put, for this reason, similarly, likewise, it follows that, naturally, by comparison, surely, yet, firstly, secondly, thirdly …

This is your fifth and final paragraph. The conclusion is what the reader will read last and remember best. Therefore, it is important that it is well written. In the conclusion, you should summarise your main points and re-assert your main claim. The conclusion should wrap up all that is said before, without starting off on a new topic. Avoid repeating specific examples.

There are several ways to end an essay. You need to find a way to leave your reader with a sense of closure. The easiest way to do this is simply to repeat the main points of the body of your text in the conclusion, but try to do this in a way that sums up rather than repeats. Another way to do it is to answer a question that you posed in the introduction. You may also want to include a relevant quotation that throws light on your message.

A few notes before you hand in your essay