Nutrition Journal

Climate-friendly diet for healthier planet.

The association between serum phosphate and length of hospital stay and all-cause mortality in adult patients: a cross-sectional study

Authors: Yiquan Zhou, Shuyi Zhang, Zhiqi Chen, Xiaomin Zhang, Yi Feng and Renying Xu

Effects of a cafeteria-based sustainable diet intervention on the adherence to the EAT-Lancet planetary health diet and greenhouse gas emissions of consumers: a quasi-experimental study at a large German hospital

Authors: Laura Harrison, Alina Herrmann, Claudia Quitmann, Gabriele Stieglbauer, Christin Zeitz, Bernd Franke and Ina Danquah

Very high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol may be associated with higher risk of cognitive impairment in older adults

Authors: Huifan Huang, Bin Yang, Renhe Yu, Wen Ouyang, Jianbin Tong and Yuan Le

Is the frequency of breakfast consumption associated with life satisfaction in children and adolescents? A cross-sectional study with 154,151 participants from 42 countries

Authors: José Francisco López-Gil, Mark A. Tully, Carlos Cristi-Montero, Javier Brazo-Sayavera, Anelise Reis Gaya, Joaquín Calatayud, Rubén López-Bueno and Lee Smith

Seafood intake in childhood/adolescence and the risk of obesity: results from a Nationwide Cohort Study

Authors: Tianyue Zhang, Hao Ye, Xiaoqin Pang, Xiaohui Liu, Yepeng Hu, Yuanyou Wang, Chao Zheng, Jingjing Jiao and Xiaohong Xu

Most recent articles RSS

View all articles

Childhood obesity, prevalence and prevention

Authors: Mahshid Dehghan, Noori Akhtar-Danesh and Anwar T Merchant

Weight Science: Evaluating the Evidence for a Paradigm Shift

Authors: Linda Bacon and Lucy Aphramor

A survey of energy drink consumption patterns among college students

Authors: Brenda M Malinauskas, Victor G Aeby, Reginald F Overton, Tracy Carpenter-Aeby and Kimberly Barber-Heidal

Nutrition and cancer: A review of the evidence for an anti-cancer diet

Authors: Michael S Donaldson

The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices, herbs and supplements used worldwide

Authors: Monica H Carlsen, Bente L Halvorsen, Kari Holte, Siv K Bøhn, Steinar Dragland, Laura Sampson, Carol Willey, Haruki Senoo, Yuko Umezono, Chiho Sanada, Ingrid Barikmo, Nega Berhe, Walter C Willett, Katherine M Phillips, David R Jacobs Jr and Rune Blomhoff

Most accessed articles RSS

Featured Article: Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and its association with sustainable dietary behaviors, sociodemographic factors, and lifestyle: a cross-sectional study in US University students

Dr. Gao won the Irwin H. Rosenberg Pre-doctoral Award from the Jean Mayor USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts(2006), the Wayne A. Hening Sleep Medicine Investigator Award from the American Academy of Neurology (2011), the Leadership/Expertise Alumni Award from the Tufts Nutrition School (2012), and the Samuel Fomon Young Physician Investigator Award from American Society for Nutrition(2015). He was selected into the Tufts Honorable Alumni Registry in 2015.

Dr. Gao received his M.S. in Epidemiology from Peking Union Medical College and his M.D. from Shanghai Second Medical University. He received his Ph.D. in nutritional epidemiology from Tufts University.

Qi Sun, MD, Sc.D., Co-Editor-in-Chief

Dr. Qi Sun is Associate Professor of Medicine in Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. He is also Associate Professor in the Departments of Nutrition and Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Sun’s primary research interests include identifying and examining biomedical risk factors, particularly dietary biomarkers, in relation to type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease through epidemiological investigations. His research is primarily based on several large-scale cohort studies including the Nurses’ Health Studies and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Dr. Sun is also interested in understanding the role of environmental pollutants, such as perfluoroalkyl substances and legacy persistent organic pollutants, in the etiology of weight change and type 2 diabetes. In the era of precision nutrition, Dr. Sun develops a new research interest of understanding the role of microbiome in mediating and modulating diet-health associations. Dr. Sun is currently leading a few NIH-funded projects that focus on food biomarker discovery and validation, diet-microbiome-health inter-relationships, as well as associations between obesogens and weight change in human populations.

- Editorial Board

- Manuscript editing services

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

- Follow us on Twitter

Annual Journal Metrics

Citation Impact 2023 Journal Impact Factor: 4.4 5-year Journal Impact Factor: 4.6 Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP): 1.551 SCImago Journal Rank (SJR): 1.288

Speed 2023 Submission to first editorial decision (median days): 15 Submission to acceptance (median days): 181

Usage 2023 Downloads: 2,353,888 Altmetric mentions: 3,953

- More about our metrics

ISSN: 1475-2891

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Last updated 10th July 2024: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- < Back to search results

- Journal of Nutritional Science

Journal of Nutritional Science

- Submit your article

- Announcements

This journal utilises an Online Peer Review Service (OPRS) for submissions. By clicking "Continue" you will be taken to our partner site https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jns . Please be aware that your Cambridge account is not valid for this OPRS and registration is required. We strongly advise you to read all "Author instructions" in the "Journal information" area prior to submitting.

- Information

- Journal home

- Journal information

- Latest volume

- All volumes

- You have access: full Access: Full

- Open access

- ISSN: 2048-6790 (Online)

- Editor: Professor Bernard Corfe Newcastle University, UK

- Editorial board

Latest articles

The assessment of dietary carotenoid intake of the cardio-med ffq using food records and biomarkers in an australian cardiology cohort: a pilot validation.

- Teagan Kucianski , Hannah L. Mayr , Audrey Tierney , Hassan Vally , Colleen J. Thomas , Leila Karimi , Lisa G. Wood , Catherine Itsiopoulos

- Journal of Nutritional Science , Volume 13

Processed food consumption and risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in South Africa: evidence from Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) VII

- Swapnil Godbharle , Hema Kesa , Angeline Jeyakumar

Impact of lipid emulsions in parenteral nutrition on platelets: a literature review

- Betul Kisioglu , Funda Tamer

Only two in five pregnant women have adequate dietary diversity during antenatal care at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital in Eastern Ethiopia

- Sinetibeb Mesfin , Dawit Abebe , Hirut Dinku Jiru , Seboka Abebe Sori

Changing sustainable diet behaviours during the COVID-19 Pandemic: inequitable outcomes across a sociodemographically diverse sample of adults

- Elizabeth Ludwig-Borycz , Ana Baylin , Andrew D. Jones , Allison Webster , Anne Elise Stratton , Katherine W. Bauer

The effects of nutrition and health education on the nutritional status of internally displaced schoolchildren in Cameroon: a randomised controlled trial

- Mirabelle Boh Nwachan , Richard Aba Ejoh , Ngangmou Thierry Noumo , Clementine Endam Njong

Advancing assessment of responsive feeding environments and practices in child care

- Julie E. Campbell , Jessie-Lee D. McIsaac , Margaret Young , Elizabeth Dickson , Sarah Caldwell , Rachel Barich , Misty Rossiter

Professor William Philip Trehearne James, FRSE FMedSci CBE (1938–2023)

- Paul Trayhurn

Journal of Nutritional Science Blog

Meet Bernard Corfe: Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Nutritional Science

- 22 November 2023, Bernard Corfe

- I was always interested in core biological processes, from school years, genetics was the area of biology I found most inspiring and through my BSc and PhD...

Nutrition Society Paper of the Month

Can mechanistic research in nutrition contribute to a better understanding of relationships between diet and non-communicable diseases (NCD)?

- 21 May 2024, Christine M Williams

- Most of the evidence linking diet with complex diseases such as heart disease and cancer (non-communicable diseases (NCD)) is based on findings from epidemiological...

Nutrition blog

Recent evidence on selenoneine highlights the need to consider selenium speciation in research and dietary guidelines

- 16 April 2024, Matthew Little, Pierre Ayotte and Mélanie Lemire

- There are numerous essential vitamins and minerals that play crucial roles in maintaining our health and wellbeing. Among these, selenium stands out as a lesser...

Can health-related food taxes green our diets?

- 27 March 2024, Margreet R Olthof, Michelle Eykelenboom, Derek Mersch, Reina E Vellinga, Elisabeth HM Temme, Ingrid HM Steenhuis and Alessandra Grasso

- In a world increasingly concerned with both health and environmental sustainability, the way we eat plays a critical role. However, in our search for solutions...

Tweets by Nutrition Society Publications

2022 Journal Citation Reports © Clarivate Analytics

EDITORIAL article

Editorial: eating behavior and chronic diseases: research evidence from population studies.

- 1 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Jiangsu Province Geriatric Institute, Nanjing, China

- 2 Department of Primary Health Management, Nanjing Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Nanjing, China

- 3 School of Population Health, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4 School of Public Health, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 5 College of Health Sciences, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Editorial on the Research Topic Eating behavior and chronic diseases: research evidence from population studies

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as overweight/obesity, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory disease, have been becoming a major global public health problem ( 1 ). NCDs account for over 70% of all deaths and impose significant economic burdens worldwide ( 1 ). Therefore, it is in urgent need on a global scale to implement effective and feasible actions against NCDs from either public health or economic viewpoint. NCDs are usually preventable, as they share key modifiable lifestyle and behavioral risk factors, including unhealthy eating behavior ( 1 ).

As a major lifestyle-related modifiable factor of NCDs, eating behavior is particularly important for the prevention of NCDs. Typically, eating behavior refers to not only dietary patterns but also nutrient intake. From the public health nutrition perspective, population-based evidence on healthy eating is of significance for sharpening policies aimed at preventing NCDs. Thus, this Research Topic was designed to provide population-level evidence on the relationship between eating behavior (both dietary patterns and nutrient intake) and selected NCDs across diverse sub-populations, with particular interest in the interactive associations between eating behavior and other lifestyle/behaviors (e.g., physical activity) in relation to NCDs.

In the paper Associations of healthy eating index-2015 with osteoporosis and low bone mass density in postmenopausal women: a population-based study from NHANES 2007-2018 ( Wang et al. ), it was observed that diet quality indicated with healthy eating index-2015 (HEI-2015) was in negative association with the risk of osteoporosis but had no link with low bone mass density (BMD) among postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older in the USA. Osteoporosis, a common metabolic bone disorder, has been emerging as a significant public health issue with a prevalence of 19.7% in the general population worldwide ( 2 ). In addition to existing evidence on the association of nutrients intake with osteoporosis and BMD, this study reported the potential link between overall dietary patterns and osteoporosis as well as BMD. It is of important public health meaningfulness to examine the associations of both overall dietary patterns and nutrients intake with osteoporosis.

The correlation between fruit intake and all-cause mortality in hypertensive patients: a 10-year follow-up study ( Sun et al. ). Based data derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), this cohort study found that, among the common five fruits (apple, banana, pear, pineapple, and grape), intake of apple or banana was associated with decreased risk of all-cause mortality for American hypertensive people. As one of major types of daily foods, fruit is essential to human health. Previously, it has been well-documented that fruit intake was negatively associated with the risk of developing hypertension ( 3 ). Meanwhile, it is also important to investigate the relationship between eating behaviors and the risk of death. The present study made a contribution to literature, as it provided another scenario of the association between fruit intake and human health in that increased consumption of specific fruits can reduce the risk of all-cause death for hypertensive individuals.

Compliance with the EAT-Lancet diet and risk of colorectal cancer: a prospective cohort study in 98,415 American adults ( Ren et al. ). With a mean follow-up period of 8.82 years, this study identified that the EAT-Lancet diet (ELD) can reduce the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) among American adults. ELD, a universally applicable dietary pattern introduced in 2019, encourages the intake of plant-based foods (including vegetables, whole grains, fruits, unsaturated oils, legumes, and nuts) and fish, but limits the consumption of meat and animal products (e.g., beef and lamb, pork, poultry, eggs, and dairy), potatoes and added sugar ( 4 ). Different from traditional dietary patterns, the ELD pattern integrated the concepts of nutrition-based health promotion approaches and environmental sustainability ( 4 ). In terms of human health promotion, ELD has been examined that it can decrease the incidence and mortality of NCDs such as stroke, CVDs, and cancers ( 5 – 8 ). On the other hand, in terms of environmental sustainability, compliance with the ELD was investigated to be associated with a significant reduction in either greenhouse gas emissions or freshwater consumption ( 9 ). Therefore, the ELD may be a scientifically optimized dietary pattern for human long-term development on the earth.

Soft and energy drinks consumption and associated factors in Saudi adults: a national cross sectional study ( Aljaadi et al. ). This study reported a high prevalence of weekly consumption of energy-dense drinks among Saudi adults based on nationally representative data collected in 2021. Energy-dense drinks consumption has been examined to be associated with adverse health outcomes, including obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), and CVDs ( 10 – 12 ). It is crucial to implement interventions aimed at reducing the consumption of energy-dense drinks to prevent and alleviate NCDs. The findings regarding energy-dense drinks consumption in this study were similar to those documented in a nationwide survey conducted among Saudi adults in 2013 ( 13 ), unfortunately showing that it is not easy for people to modify their preference or habit of food consumption at the population level. Therefore, for the purpose of population-based NCDs prevention through precision lifestyle/behavior intervention, it is important to dynamically investigate population-level eating behaviors and the associated factors.

Patient-centered nutrition education improved the eating behavior of persons with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus in North Ethiopia: a quasi-experimental study ( Gebreyesus et al. ). This study presented that a 3-month patient-centered nutrition education intervention could significantly improve both specific and overall eating behaviors for T2D patients with HbA1c ≥ 7.0% in Ethiopia. Additionally, the nutritional intervention was effective in lowering the HbA1c levels among the participants in this study. It highlighted that nutrition education as an intervention approach would be effective to improve eating behavior and glycemic control for diabetic patients in a resource-limited country. Adopting and maintaining healthy eating are always encouraged for diabetic patients to effectively manage the blood glucose ( 14 ). However, the biggest challenge is not to have people's eating behaviors modified with an intervention program, but to have the favorably-changed eating behaviors maintained for a lifetime or, at least, as long as possible.

Population-based comprehensive lifestyle and behavior intervention is of particular importance and effectiveness for NCDs prevention, and it is often viewed as a feasible and cost-effective approach for preventing NCDs. It is necessary to document the updated findings on the association of lifestyle and behavior with NCDs from nutritional epidemiological studies. The papers related to our Research Topic could offer valuable information to assist researchers, clinicians and policy-makers in designing and implementing dietary-specific intervention programs or policies, thus contributing to the prevention of NCDs.

In summary, eating behavior is time and economic status dependent, which may change as an individual's age or/and socio-economic status changes. This may occur in both developing societies and economically settled communities. Meanwhile, updating the dietary patterns and nutrient intake levels of different sub-populations is also necessary for precision eating behavior intervention. Therefore, although relationships between eating behaviors (dietary pattern, nutrients intake) and specific NCDs have been examined in different societies, studies are always welcome to continuously investigate population-level associations between eating behavior and NCDs in sub-populations with culturally and linguistically diverse background, and especially to further examine the interaction between eating behavior and other factors, such as physical activity, on NCDs. In future, research in these two areas needs to be encouraged to provide evidence supporting healthy dietary guidelines or policies for the prevention of NCDs.

Author contributions

FX: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XX: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZS: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. World Health Organization. Non-communicable disease Progress Monitor 2020 . Geneva: World Health Organization (2020).

Google Scholar

2. Xiao PL, Cui AY, Hsu CJ, Peng R, Jiang N, Xu XH, et al. Global, regional prevalence, and risk factors of osteoporosis according to the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. (2022) 33:2137–53. doi: 10.1007/s00198-022-06454-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Madsen H, Sen A, Aune D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Nutr. (2023) 62:1941–55. doi: 10.1007/s00394-023-03145-5

4. Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. (2019) 393:447–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4

5. Ibsen DB, Christiansen AH, Olsen A, Tjønneland A, Overvad K, Wolk A, et al. Adherence to the EAT-lancet diet and risk of stroke and stroke subtypes: a cohort study. Stroke. (2022) 53:154–63. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.036738

6. Berthy F, Brunin J, Allès B, Fezeu LK, Touvier M, Hercberg S, et al. Association between adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet and risk of cancer and cardiovascular outcomes in the prospective NutriNet-Santé cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. (2022) 116:980–91. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac208

7. Stubbendorff A, Sonestedt E, Ramne S, Drake I, Hallström E, Ericson U. Development of an EAT-Lancet index and its relation to mortality in a Swedish population. Am J Clin Nutr. (2022) 115:705–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab369

8. Zhang S, Dukuzimana J, Stubbendorff A, Ericson U, Borné Y, Sonestedt E. Adherence to the EAT-lancet diet and risk of coronary events in the Malmö diet and cancer cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. (2023) 117:903–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.02.018

9. Springmann M, Spajic L, Clark MA, Poore J, Herforth A, Webb P, et al. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: modelling study. BMJ. (2020) 370:m2322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2322

10. Heidari-Beni M, Kelishadi R. The role of dietary sugars and sweeteners in metabolic disorders and diabetes In: Sweeteners: pharmacology, biotechnology, and applications . Cham: Springer International Publishing (2018). p. 225–43. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-27027-2_31

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després JP, Hu FB. Sugar sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. (2010) 121:1356–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185

12. Al-Hanawi MK, Ahmed MU, Alshareef N, Qattan AMN, Pulok MH. Determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among the Saudi adults: findings from a nationally representative survey. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:744116. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.744116

13. Hu H, Song J, Mac Gregor GA, He FJ. Consumption of soft drinks and overweight and obesity among adolescents in 107 countries and regions. JAMA Netw Open. (2023) 6:e2325158–8. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.25158

14. Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, Brunzell JD, Chiasson JL, Garg A, et al. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. (2003) 26 Suppl 1:S51–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.148

Keywords: eating behavior, chronic disease, dietary pattern, nutrients intake, nutritional epidemiology, population-based evidence

Citation: Xu F, Xu X, Zhao L and Shi Z (2024) Editorial: Eating behavior and chronic diseases: research evidence from population studies. Front. Nutr. 11:1454339. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1454339

Received: 25 June 2024; Accepted: 08 July 2024; Published: 16 July 2024.

Edited and reviewed by: Mauro Serafini , University of Teramo, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Xu, Xu, Zhao and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fei Xu, xufei@njmu.edu.cn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Assessing the Cost of Healthy and Unhealthy Diets: A Systematic Review of Methods

- Public Health Nutrition (KE Charlton, Section Editor)

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2022

- Volume 11 , pages 600–617, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Cherie Russell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1251-4810 1 ,

- Jillian Whelan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9434-109X 2 &

- Penelope Love ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1244-3947 1 , 3

6561 Accesses

4 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

Poor diets are a leading risk factor for chronic disease globally. Research suggests healthy foods are often harder to access, more expensive, and of a lower quality in rural/remote or low-income/high minority areas. Food pricing studies are frequently undertaken to explore food affordability. We aimed to capture and summarise food environment costing methodologies used in both urban and rural settings.

Recent Findings

Our systematic review of high-income countries between 2006 and 2021 found 100 relevant food pricing studies. Most were conducted in the USA ( n = 47) and Australia ( n = 24), predominantly in urban areas ( n = 74) and cross-sectional in design ( n = 76). All described a data collection methodology, with just over half ( n = 57) using a named instrument. The main purpose for studies was to monitor food pricing, predominantly using the ‘food basket’, followed by the Nutrition Environment Measures Survey for Stores (NEMS-S). Comparatively, the Healthy Diets Australian Standardised Affordability and Price (ASAP) instrument supplied data on relative affordability to household incomes.

Future research would benefit from a universal instrument reflecting geographic and socio-cultural context and collecting longitudinal data to inform and evaluate initiatives targeting food affordability, availability, and accessibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

A tale of two cities: the cost, price-differential and affordability of current and healthy diets in Sydney and Canberra, Australia

Healthy diets asap – australian standardised affordability and pricing methods protocol, testing the price and affordability of healthy and current (unhealthy) diets and the potential impacts of policy change in australia.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Poor diets, described as those low in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and high in red and processed meats and ultra-processed foods, are a leading risk factor for chronic disease globally [ 1 ]. In most high-income countries (HIC), poor diets disproportionally affect lower socioeconomic populations, Indigenous Peoples, and those living in rural and/or remote areas [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Rather than solely a consequence of individual behaviours, poor diets are critically informed by broad contextual factors, including social, commercial, environmental, and cultural influences [ 6 , 7 ]. Crucially, the consumption of a healthy diet is constrained by the range, affordability, and acceptability of foods available for sale [ 8 ]. Research suggests that healthy foods are often harder to access, more expensive, and often of a lower quality in rural, remote, or low-income/high minority areas, than in metropolitan or high-income areas [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Such food environments contribute to higher rates of diet-related non-communicable diseases and food insecurity [ 13 , 14 ]. In order to improve population diets, all aspects of the food environment must be addressed to ensure healthy foods are affordable, available, and of adequate nutritional quality [ 15 ].

Price is a primary factor impacting food choice, diet quality, and food security, therefore having affordable, acceptable, healthy food should be a political and social priority [ 8 , 15 , 16 ]. Some research suggests that healthy diets are associated with greater total spending [ 17 , 18 , 19 ], while other studies report that adherence to a healthy diet is less expensive than current or ‘unhealthy’ diets [ 9 , 20 , 21 ]. Regardless, the cost of a healthy diet is a proportionately large household expense (> 30% of household income) and may therefore be considered ‘unaffordable’ [ 22 ]. Additionally, public perception that healthy diets are expensive is high, which itself may be a barrier to the purchase of healthy foods [ 23 ]. Therefore, improving the affordability of healthy food could improve population diets, regardless of context [ 24 ].

To address the issue of food affordability and inform appropriate attenuating policy and intervention strategies, food pricing studies are frequently undertaken. Food pricing, however, is not a universal construct and is highly influenced by country and context. Numerous methods have been developed to measure food pricing, with data therefore not always comparable or replicable, and of limited value to inform appropriate policy [ 25 ]. Most studies that collect food pricing data conclude that food prices are rising, making healthy eating unaffordable for many populations. However, few studies to date have used this data to suggest strategies to improve affordability. Our systematic review aims to capture and summarise food environment costing methodologies used in HIC, in both urban and rural settings, between 2006 and 2021. In addressing this aim, we answer the following questions: (i) What is the stated purpose of collecting data on food prices, including whether the data is used to inform or advocate for interventions? (ii) Which instruments are being used to measure food pricing? (iii) What are the strengths and limitations of each instrument as reported by study authors?

To address the research aim, we undertook a systematic review of the literature, following the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 26 ]. We followed four steps: (i) systematic search for relevant literature; (ii) selection of studies, (iii) data extraction, and (iv) analysis and synthesis of results.

Systematic Search Strategy

After consultation with a research liaison librarian, databases used included EBSCOHOST (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Complete, GlobalHealth, Medline Complete, and PsychINFO) and Informit. We chose these databases for their comprehensiveness and conventional use in the public health nutrition discipline. We identified search terms using a scoping review and key words used in previous food pricing reviews [ 15 , 23 , 27 , 28 ]. We searched both article abstracts and titles using the following search string: ‘food affordability’ OR ‘food cost’ OR ‘food price*’ OR ‘food promotion*’. We completed an initial search for studies published 2016–2021 in October 2021, followed by a search for studies published 2006–2015 in December 2021.

Selection of Studies

Studies were included if they were English, peer-reviewed journal articles presenting original research, monitored food prices in a high-income country/s, and were published between 2006 and 2021. The article by Glanz (2006) [ 15 ] is considered a seminal paper in food pricing research and was therefore chosen as the starting date for our search. Studies prior to this date were considered unlikely to be relevant to the research question and were thus excluded. Review articles, opinion pieces, posters, perspectives, study protocols, viewpoints, editorials, and commentaries were excluded, as well as those assessing middle- or low-income countries.

Study screening involved an initial review of all titles and removal of duplicates by A1 using online Covidence software [ 29 ], followed by abstract screening (A1), and then full text screening of remaining studies (A1). A second reviewer independently screened all articles by abstract and full text to minimise bias (A2 and A3). Disagreements were resolved through discussion between researchers; where no agreement was reached, a third party acted as an arbiter (A2 and A3). Limited hand searching was conducted given the volume of papers identified. Online Resource 1 presents a PRISMA flow chart of the study selection process.

Data Extraction

Included studies were uploaded to an Endnote (V. X9) [ 30 ] library. We systematically extracted details of each study to Microsoft Excel (V. 2112), including the author/s, year published, article title, aim, pricing instrument used (if specified), country and geographical context (e.g. urban or rural), type of data collected, number and type of locations assessed, number and type of food items captured, population (if the study used sales receipts to estimate food prices), time period of study, strengths, limitations, and conclusions.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

The coded data were used to identify major themes that were then synthesised in the results. We used an inductive thematic approach for our analysis, with the results discussed between the research team to limit researcher subjectivity [ 31 ]. We used Microsoft Excel to calculate descriptive statistics and graphical outputs.

Overview of Studies

Database searching identified 2737 studies, with 1882 studies remaining after removal of duplicates. After abstract screening, a total of 287 were identified for full-text screening, with 187 excluded, and a total of 100 studies included in this systematic review (Online Resource 1).

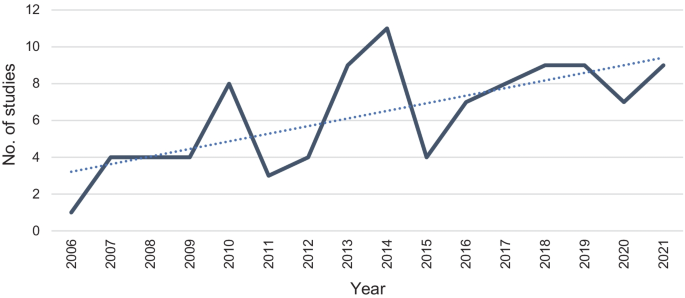

We observed an increasing number of studies each year, with peaks in 2013, 2014, and 2018 (Fig. 1 ).

Frequency of studies published assessing food prices between 2006 and 2021

Most studies measured food prices in the USA ( n = 47), followed by Australia ( n = 25). Urban food environments were assessed more frequently ( n = 74) than rural ( n = 33). Most studies were cross-sectional ( n = 77). Most studies included instore price audits ( n = 59), followed by online price audits (supermarket websites, n = 13), or electronic point of sale data (consumer receipts, register sales, or electronic scanning of food prices in the home, n = 12), and a combination of these ( n = 17). Most studies collected food price data from more than 20 food retail outlets ( n = 34) (Table 1 ).

Details of all included studies, grouped according to data source used (instore price audits, online price audits, electronic point of sale, and combinations of these), are shown in Tables 2 , 3 , and 4 . Details include instrument used (if applicable), purpose of data collection, country, context, study type (e.g. cross-sectional, longitudinal), healthiness comparisons (between healthy and unhealthy products or diets), study author, and year. The use of a named instrument was captured to identify commonalities in usage of instruments, and not as an indication of study quality. When assessing differentials in ‘healthiness’, studies either presented a comparison of a ‘healthy diet’ with an ‘unhealthy or currently consumed diet’ or a comparison of the cost of ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ foods or product categories.

Study Purpose for Collecting Data on Food Prices

The studies included in this review had a multitude of aims (Tables 2 , 3 , and 4 ). While most studies were conducted solely to monitor food prices in a specific location/s [ 33 , 39 , 42 , 46 , 47 , 52 , 54 , 56 , 57 , 59 , 64 , 67 , 71 , 75 , 80 , 81 , 88 , 89 , 104 , 106 , 108 , 109 , 114 ], others aimed to monitor food price changes over time [ 53 , 63 , 74 , 83 , 93 , 97 , 111 , 127 ], assess food prices as a function of income, socioeconomic status, or welfare assistance [ 9 , 19 , 20 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 66 , 69 , 70 , 77 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 94 , 100 , 110 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 122 ]; assess food price in relation to geographic distance [ 19 , 77 , 91 , 92 , 94 , 98 ]; compare perceptions of food price with actual food prices [ 68 , 101 , 107 ]; and relate food price with a health outcome [ 34 , 35 , 37 , 40 , 47 , 58 , 70 , 72 , 78 , 105 , 116 , 117 , 124 , 125 ], compare the price of healthy or unhealthy foods/diets [ 9 , 20 , 34 , 43 , 50 , 51 , 55 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 76 , 85 , 86 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 99 , 102 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 120 , 121 , 123 , 124 , 126 ], assess diet costs for a specific population [ 82 , 118 ], compare food prices between brands [ 79 ], compare approaches for estimating dietary costs [ 32 ], or understand how prices impact consumption [ 44 ]. Only seven studies specifically aimed to collect data to inform policy strategies and/or community interventions to improve population health [ 10 , 11 , 49 , 80 , 87 , 103 , 113 ]. However, 26 studies did discuss their study findings on food price in relation to potential further action to improve food environments [ 9 , 19 , 20 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 40 , 43 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 54 , 55 , 59 , 63 , 64 , 81 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 110 ]. Specific suggested strategies included those targeting individuals, such as education campaigns to promote healthy and more affordable food choices [ 9 , 36 , 43 , 45 , 49 , 50 , 55 ], and those targeting environmental changes, such as taxes on ‘unhealthy’ foods [ 33 , 49 , 85 , 104 , 110 ], subsidies and exemptions for ‘healthy’ foods [ 9 , 20 , 45 , 62 , 63 , 85 , 104 , 110 ], vouchers for farmer’s markets [ 43 ], establishing more food stores [ 33 , 45 , 48 , 104 ], better public transportation for consumers to access food stores [ 59 ], generating savings at the manufacturer/wholesaler level that can be passed on to customers [ 81 ], establishing community-led food supply options [ 9 ], and increasing welfare support proportionate to food prices and geographic distances to food stores [ 37 , 40 , 50 , 73 , 85 ].

Overview of Instruments Used to Measure Food Prices

Of the 100 included studies, 57 used a named instrument to measure food prices, as described below. The remaining 43 studies did not name a pre-existing data collection instrument; instead, the authors described the data collection methodology used, for example, in store, online, or via electronic sales data.

Food Basket Instruments

The majority ( n = 30) of studies used a variation of a ‘food basket’ to estimate food prices. Food baskets capture the prices of a pre-defined list of foods, often in quantities representative of the total diet of reference families over a defined timeframe [ 9 ], and is a longstanding methodology used to investigate the availability and affordability of food. Food basket studies were mainly conducted in the USA ( n = 14) and Australia ( n = 12) [ 19 , 20 , 80 , 81 , 83 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 ]. Food basket studies using named instruments were conducted in the USA—using the Thrifty Food Plan Market Basket ( n = 5), the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Market Basket ( n = 3), the University of Washington’s Center for Public Health Nutrition Market Basket ( n = 3), and the USDA Market Basket ( n = 2); in Australia—using the Victorian Healthy Food Basket ( n = 4), the Food Basket informed by the INFORMAS framework ( n = 2), the Adelaide Healthy Food Basket ( n = 2), the Illawarra Healthy Food Basket ( n = 2), the Queensland Healthy Food Access Basket Survey ( n = 1), and the Northern Territory Market Basket ( n = 1); and in Canada—using the Ontario Nutritious food basket ( n = 1), the Revised Northern Food Basket ( n = 1), and an unspecified market basket ( n = 1). Food basket studies were conducted in both rural ( n = 13) [ 19 , 37 , 49 , 50 , 52 , 81 , 83 , 87 , 88 , 90 , 91 , 103 , 110 ] and urban contexts ( n = 25) [ 19 , 20 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 46 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 66 , 67 , 70 , 80 , 81 , 83 , 88 , 89 , 92 , 104 , 105 , 111 ].

All but two [ 37 , 40 ] food basket studies collected prices from physical instore locations [ 19 , 20 , 38 , 43 , 46 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 55 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 66 , 67 , 70 , 73 , 80 , 81 , 83 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 110 ], with four of these studies supplementing the data with online supermarket prices [ 62 , 63 , 64 , 81 ]. Additionally, three instruments compared the cost of a ‘healthy diet’ to either an ‘unhealthy or currently consumed diet’ [ 20 , 88 , 110 ], 13 instruments compared the cost of ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ individual foods or product categories [ 19 , 38 , 51 , 62 , 63 , 66 , 83 , 87 , 89 , 90 , 103 ], and 14 instruments did not present a comparison [ 37 , 40 , 46 , 49 , 50 , 52 , 64 , 67 , 70 , 80 , 81 , 91 , 92 , 104 , 105 ]. ‘Current’ diets were defined using national survey data [ 20 , 110 ]. Level of healthiness was defined using various benchmarks, namely the NOVA food processing classification system [ 38 ], nutrient composition and energy density [ 38 , 51 , 62 , 63 , 66 , 80 , 83 , 90 ], national Dietary Guidelines [ 19 , 43 , 70 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 ], and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern [ 43 ]. Food affordability was benchmarked using household income [ 20 , 49 , 50 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 103 , 105 , 110 ], government subsidies [ 37 , 40 , 87 , 89 , 91 ], and minimum wage [ 38 , 66 , 70 ]; however, most studies ( n = 13) did not determine relative affordability in their analysis [ 43 , 51 , 52 , 55 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 67 , 73 , 80 , 81 , 83 , 88 ].

Healthy Diets Australian Standardised Affordability and Price (ASAP) Instrument

Following critiques of existing food baskets, the previously described INFORMAS instrument was refined to assess and compare the price and affordability of healthy and current diets in Australia, leading to the development of the Healthy Diets Australian Standardised Affordability and Price (ASAP). This instrument assesses the cost of a ‘recommended’ Australian diet (defined by the Australian Dietary Guidelines and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating) and the cost of the ‘current’ Australian diet (as reported in the 2011–12 Australian Health Survey) using the reference household of two parents and two children (boy aged 14 years; girl aged 8 years) [ 128 ]. Thus, all studies using this instrument present a comparison of the cost of a ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ diet in their analysis. Intrinsic to the instrument, the relative affordability of a healthy diet is measured against household incomes. The ASAP instrument was used by four studies to collect food price data in physical instore locations [ 9 , 85 , 86 ] or from online supermarkets [ 94 ]. Studies were conducted in both rural ( n = 2) [ 9 , 85 , 94 ] and urban ( n = 2) [ 85 , 86 , 94 ] contexts.

Nutrition Environment Measures Survey for Stores (NEMS-S) Instrument

The Nutrition Environment Measures Survey for Stores (NEMS-S) and its variants were also frequently used throughout food pricing studies ( n = 15). These included NEMS-S-Rev (Nutrition Environment Measures Survey for Stores Revised), TxNEAS (Texas Nutrition Environment Assessment), NEMS-S-NL (Nutrition Environment Measures Survey for Stores Newfoundland and Labrador), and The Bridging the Gap Food Store Observation Form. This instrument was used mostly in the USA ( n = 11) [ 11 , 33 , 36 , 44 , 47 , 48 , 54 , 57 , 68 , 71 , 107 ]. Studies were conducted in both rural ( n = 4) [ 10 , 11 , 56 , 106 ] and urban ( n = 11) [ 33 , 36 , 44 , 47 , 48 , 54 , 57 , 68 , 71 , 107 , 108 ] contexts. Compared to the food basket methodology, the NEMS-S instrument compares products in the same category that are considered ‘healthy’ or ‘unhealthy’ based on American Dietetic Association (ADA) recommended dietary guidelines, focusing on availability, price, and quality. All studies using the NEMS-S instrument collected food price data in physical instore locations. While the instrument itself does not include a calculation of relative affordability, approximately half the NEMS-S studies included this step in their methods [ 33 , 36 , 44 , 47 , 48 , 54 , 57 ], while all others did not [ 10 , 11 , 56 , 68 , 71 , 106 , 107 , 108 ].

Other Instruments

Several other named instruments were identified, used in single studies. These included the Diet and Nutrition Tool for Evaluation (DANTE) [ 101 ], the Flint Store Food Assessment Instrument [ 60 ], the Food Label Trial registry tool [ 76 ], the New Zealand Food Price Index [ 111 ], the USDA Food Store Survey Instrument [ 73 ], USDA Low-cost food plan [ 55 ] and audit forms developed by the Yale Rudd Center [ 39 ], the Hartford Advisory Commission on Food Policy [ 59 ], and the USDA Authorized Food Retailers’ Characteristics and Access Study [ 43 ]. Only three instruments compared healthy and unhealthy products [ 43 , 76 , 111 ] and none analysed the relative affordability of food.

Instrument Strengths and Limitations

The strengths and limitations of instruments commonly used across studies, as identified by study authors, are presented in Online Resource 2 . Commonly cited limitations, regardless of instrument used, included that actual purchasing behaviours were not captured (unless electronic point of sales data was utilised); culturally important and region-specific products were often not captured; tools were cross-sectional in nature, thus seasonality or changes overtime were not considered; and out-shopping, described as food purchases undertaken outside the local residential geography, including internet orders or foods purchased during travel to other communities, could not be accounted for. While some food basket studies and those using the ASAP instrument did contextualise the relative affordability of healthy foods and/or diets, this was not a part of the methodology for NEMS-S. Other limitations specific to NEMS-S included the length of the survey, and a low convergence between NEMS-S results and consumer perceptions of affordability. Specific limitations for food basket studies included results being constrained by the reference family used and the assumption that food is shared equally among household members. Additionally, most instruments did not capture geographical information regarding access to food retail outlets or availability of foods within food retail outlets.

Authors less commonly described instrument strengths. For NEMS-S, cited strengths included the ability to compare food prices between healthy and unhealthy options, that it has strong inter-rater and test-re-test reliability, and that it has been validated in multiple countries. ASAP studies, and some food basket studies, included a comparison between healthy and current (‘unhealthy’) diets (based on actual consumption) and included alcohol in the survey.

Our systematic review details the key purposes, and methodologies used, for measuring food prices in HIC between 2006 and 2021. While most studies were conducted solely to monitor food prices in specific locations, some sought to report price changes over time, and others collected data to assess comparability of food costs to healthier alternatives, average earnings, welfare payments, rurality, and socioeconomic position. Most studies measured food prices in urban areas, using instore food price audits, with an emerging use of online data collection evident. The most frequently used instruments were ‘food baskets’, used predominantly to monitor food prices; the NEMS-S instrument, used to provide data on relative cost and availability; and the ASAP instrument, use to provide data on relative affordability.

Our review differs from previous reviews of food price and affordability instruments [ 23 , 28 ] by taking a broadened focus on food pricing measures used in HIC globally and including new technology that is affording opportunities for electronic food pricing data collection. While a previous review critiqued food pricing measures for relevance specific to a rural context, our review includes both rural and urban contexts [ 28 ]. Another review [ 23 ] also describes the components of individual instruments, such as the identification of differently sized ‘food baskets’, ranging between 30 and 200 food items. Such critique was beyond the scope of our research questions.

Despite emerging options for electronic methodologies, the predominance of in person, instore data collection continues, notwithstanding the time-consuming and resource-intensive nature of this method. Studies indicate that these instore instruments can be targeted and applied within multiple contexts, such as rural [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ], Indigenous [ 129 , 130 ], and low socioeconomic areas [ 85 ]. Perhaps researchers consider instore data collection as providing real-world insights at a community and population health level. Our review identified that food pricing instruments were mostly used to monitor food prices at a single point in time (cross-sectional) rather than changes at different time points (longitudinal). Instruments that enable the comparison of food prices in terms of a healthy diet (as recommended by dietary guidelines) compared with current dietary patterns (as reported through population health surveys) [ 128 ], and relative affordability for families, appear to provide data of greater practice and policy relevance with regard to community strategies, taxes, and subsidies that have potential to enhance food affordability, availability, and accessibility.

Technological innovations are an emerging alternative to in person data collection, facilitating the acquisition of online supermarket prices, a less labour-intensive method for capturing food prices [ 131 ]. To date, this method has been used within major chain-supermarkets, with a recent study reporting similar results when comparing pricing data obtained instore versus online [ 94 ]. This method therefore holds potential where an online supermarket presence exists, which was increasingly the case during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 53 ], providing rapid feedback to inform price promotions. However, for smaller and/or independent food retail outlets, frequently located in rural areas, online data collection does not appear to capture the contextual nuances of instore price promotions.

Our review found an over-representation of food pricing studies within urban areas. This is consistent with multiple studies that reflect inequities experienced within rural environments [ 132 ], and rural food environments are no exception [ 133 ]. The predominance of research within urban areas may also reflect a pragmatic researcher response to the physical proximity of stores (ease of measurement) and larger population reach (potential for greater population impact). Previous research shows significant differences in income-based variables, food environments, and the affordability of healthy food between urban and rural settings [ 134 ]. There is therefore a need for rural-specific food pricing studies, using appropriate instruments, to evaluate and inform rural-specific food environment initiatives [ 28 ].

During the period covered by this review, high level experts from the World Health Organization [ 135 ], the Lancet Commission [ 136 ], and the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations [ 137 ] have identified the potential benefits that initiatives located within food retail environments can provide in nudging dietary choices towards healthier options through instore food pricing and promotion, with the overall aim of improving population level diets [ 14 ]. Measures of food pricing, and the relative affordability of a healthy diet, are important to both inform and measure the effectiveness of such initiatives. However, few studies in our review explicitly aimed to inform initiatives or strategies, either at the community or policy level. Assessment of author-reported strengths and limitations of food pricing instruments and methodologies also identified a need for a universal instrument that reflects contextual geographic and socio-cultural information; is intended to be used repeatedly over time; and is adaptable to different country/cultural/contextual settings [ 17 , 23 ]. Future research would benefit from linking the purpose of undertaking food pricing data collection more explicitly to potential initiatives. Our review supports this call and suggests that the instrument selected should suit the context and collect longitudinal data to provide greater insights into the design and effectiveness of initiatives that make healthy food not only affordable but also available and accessible.

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review provides a current and comprehensive overview of international food pricing studies across HIC. We acknowledge that while food prices are an important factor influencing food choice, it is only one component of the food environment; however, analysing instruments that assess food acceptability, availability, and accessibility was beyond the scope of this review. This review focused on HIC and a similar review on food pricing studies in low- and middle-income countries would be informative. This review may have missed additional relevant data as it only included English language studies and did not include grey literature or hand searching of reference lists.

Food security has come under heightened scrutiny given the food supply interruptions experienced worldwide during the COVID-19 pandemic. While studies providing a snapshot of food prices can be useful to identify areas impacted by rising food prices, much of this cross-sectional data is known. This review raises questions regarding the purpose of collecting food price data, and how this data can best be used to inform change through practice and policy strategies. We suggest that longitudinal studies using a consistent methodology, which acknowledges contextual nuances and demonstrates temporal changes in food pricing, are needed to inform and to evaluate community-based or legislative strategies to improve the relative affordability of a healthy diet.

Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Abdollahi M, Abdollahpour I, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223–49.

Article Google Scholar

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2022: Burden of Disease. Canberra: AIHW; 2020.

Google Scholar

Sloane DC, Diamant AL, Lewis LB, Yancey AK, Flynn G, Nascimento LM, Mc Carthy WJ, Guinyard JJ, Cousineau MR. Improving the nutritional resource environment for healthy living through community-based participatory research. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:568–75.

Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML, Gortmaker SL. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378:804–14.

Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1107–17.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kickbusch I, Allen L, Franz C. The commercial determinants of health. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e895–6.

Wilkinson RG, Marmot M. Social determinants of health: the solid facts, (World Health Organization). 2003.

Lee JH, Ralston RA, Truby H. Influence of food cost on diet quality and risk factors for chronic disease: a systematic review. Nutr Diet. 2011;68:248–61.

Love P, Whelan J, Bell C, Grainger F, Russell C, Lewis M, Lee A. Healthy diets in rural Victoria-cheaper than unhealthy alternatives, yet unaffordable. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15.

Whelan J, Millar L, Bell C, Russell C, Grainger F, Allender S, Love P. You can’t find healthy food in the bush: poor accessibility, availability and adequacy of food in rural Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:2316.

Pereira RF, Sidebottom AC, Boucher JL, Lindberg R, Werner R. Peer Reviewed: Assessing the Food Environment of a Rural Community: Baseline Findings From the Heart of New Ulm Project, Minnesota, 2010–2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11.

Vilaro MJ, Barnett TE. The rural food environment: a survey of food price, availability, and quality in a rural Florida community. Food Public Health. 2013;3:111–8.

Garasky S, Morton LW, Greder KA. The effects of the local food environment and social support on rural food insecurity. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2006;1:83–103.

Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Kumanyika S, Lobstein T, Neal B, Barquera S, Friel S, Hawkes C, Kelly B. INFORMAS (I nternational N etwork for F ood and O besity/non-communicable diseases R esearch, M onitoring and A ction S upport): overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013;14:1–12.

Glanz K, Johnson L, Yaroch AL, Phillips M, Ayala GX, Davis EL. Measures of retail food store environments and sales: review and implications for healthy eating initiatives. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(280–288): e281.

Begemann F. Ecogeographic differentiation of bambarra groundnut (Vigna subterranea) in the collection of the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA, (Wissenschaftlicher Fachverlag). 1988.

Lee A, Mhurchu CN, Sacks G, Swinburn B, Snowdon W, Vandevijvere S, Hawkes C, L’Abbé M, Rayner M, Sanders D. Monitoring the price and affordability of foods and diets globally. Obes Rev. 2013;14:82–95.

Rao M, Afshin A, Singh G, Mozaffarian D. Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3: e004277.

Palermo C, McCartan J, Kleve S, Sinha K, Shiell A. A longitudinal study of the cost of food in Victoria influenced by geography and nutritional quality. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40:270–3.

Lee AJ, Kane S, Ramsey R, Good E, Dick M. Testing the price and affordability of healthy and current (unhealthy) diets and the potential impacts of policy change in Australia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1–22.

Clark P, Mendoza-Gutiérrez CF, Montiel-Ojeda D, Denova-Gutiérrez E, López-González D, Moreno-Altamirano L, Reyes A. A healthy diet is not more expensive than less healthy options: cost-analysis of different dietary patterns in Mexican children and adolescents. Nutrients. 2021;13:3871.

Burns C, Friel S. It’s time to determine the cost of a healthy diet in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31:363–5.

Lewis M, Lee A. Costing ‘healthy’food baskets in Australia–a systematic review of food price and affordability monitoring tools, protocols and methods. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:2872–86.

Moayyed H, Kelly B, Feng X, Flood V. Is living near healthier food stores associated with better food intake in regional Australia? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:884.

Seal J. Monitoring the price and availability of healthy food–time for a national approach? Nutr Diet. 2004;61:197–200.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9.

Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian S, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place. 2012;18:1172–87.

Love P, Whelan J, Bell C, McCracken J. Measuring rural food environments for local action in Australia: a systematic critical synthesis review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2416.

Covidence systematic review software. Volume 2022. (Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation).

The Endnote Team. Endnote. Endnote. X9 ed. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate; 2013.

Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11:589–97.

Aaron GJ, Keim NL, Drewnowski A, Townsend MS. Estimating dietary costs of low-income women in California: a comparison of 2 approaches. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:835–41.

Andreyeva T, Blumenthal DM, Schwartz MB, Long MW, Brownell KD. Availability and prices of foods across stores and neighborhoods: the case of New Haven, Connecticut. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2008;27:1381–8.

Anekwe TD, Rahkovsky I. The association between food prices and the blood glucose level of US adults with type 2 diabetes. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:678–85.

Bernstein AM, Bloom DE, Rosner BA, Franz M, Willett WC. Relation of food cost to healthfulness of diet among US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1197–203.

Borja K, Dieringer S. Availability of affordable healthy food in Hillsborough County, Florida. J Public Aff (14723891). 2019;19. N.PAG-N.PAG.

Bronchetti ET, Christensen G, Hoynes HW. Local food prices, SNAP purchasing power, and child health. J Health Econ. 2019;68: 102231.

Buszkiewicz J, House C, Anju A, Long M, Drewnowski A, Otten JJ. The impact of a city-level minimum wage policy on supermarket food prices by food quality metrics: a two-year follow up study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:102.

Caspi CE, Pelletier JE, Harnack LJ, Erickson DJ, Lenk K, Laska MN. Pricing of staple foods at supermarkets versus small food stores. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14.

Christensen G, Bronchetti ET. Local food prices and the purchasing power of SNAP benefits. Food Policy. 2020;95. N.PAG-N.PAG.

Colabianchi N, Antonakos CL, Coulton CJ, Kaestner R, Lauria M, Porter DE. The role of the built environment, food prices and neighborhood poverty in fruit and vegetable consumption: an instrumental variable analysis of the moving to opportunity experiment. Health Place. 2021;67: 102491.

Cole S, Filomena S, Morland K. Analysis of fruit and vegetable cost and quality among racially segregated neighborhoods in Brooklyn. New York J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2010;5:202–15.

Connell CL, Zoellner JM, Yadrick MK, Chekuri SC, Crook LB, Bogle ML. Energy density, nutrient adequacy, and cost per serving can provide insight into food choices in the lower Mississippi Delta. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44:148–53.

DiSantis KI, Grier SA, Oakes JM, Kumanyika SK. Food prices and food shopping decisions of black women. Appetite. 2014;77:106–14.

Fan L, Canales E, Fountain B, Buys D. An assessment of the food retail environment in counties with high obesity rates in Mississippi. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2021;16:571–93.

Franzen L, Smith C. Food system access, shopping behavior, and influences on purchasing groceries in adult Hmong living in Minnesota. Am J Health Promot. 2010;24:396–409.

Ghosh-Dastidar B, Cohen D, Hunter G, Zenk SN, Huang C, Beckman R, Dubowitz T. Distance to store, food prices, and obesity in urban food deserts. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:587–95.

Ghosh-Dastidar M, Hunter G, Collins RL, Zenk SN, Cummins S, Beckman R, Nugroho AK, Sloan JC, Wagner LV, Dubowitz T, et al. Does opening a supermarket in a food desert change the food environment? Health Place. 2017;46:249–56.

Greenberg JA, Luick B, Alfred JM, Barber LR Jr, Bersamin A, Coleman P, Esquivel M, Fleming T, Guerrero RTL, Hollyer J, et al. The affordability of a thrifty food plan-based market basket in the United States-affiliated Pacific Region. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2020;79:217–23.

Hardin-Fanning F, Rayens MK. Food cost disparities in rural communities. Health Promot Pract. 2015;16:383–91.

Hardin-Fanning F, Wiggins AT. Food costs are higher in counties with poor health rankings. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;32:93–8.

Hilbert N, Evans-Cowley J, Reece J, Rogers C, Ake W, Hoy C. Mapping the cost of a balanced diet, as a function of travel time and food price. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems and Community Development. 2014;5:105–27.

Hillen J. Online food prices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Agribusiness (New York). 2021;37:91–107.

Jin H, Lu Y. Evaluating consumer nutrition environment in food deserts and food swamps. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18.

Karp RJ, Wong G, Orsi M. Demonstrating nutrient cost gradients: a Brooklyn case study. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2014;84:244–51.

Ko LK, Enzler C, Perry CK, Rodriguez E, Mariscal N, Linde S, Duggan C. Food availability and food access in rural agricultural communities: use of mixed methods. BMC Public Health. 2018;18. N.PAG-N.PAG.

Lee Smith M, Sunil TS, Salazar CI, Rafique S, Ory MG. Disparities of food availability and affordability within convenience stores in Bexar County. Texas J Environ Public Health. 2013;2013:1–7.

Lipsky LM. Are energy-dense foods really cheaper? Reexamining the relation between food price and energy density. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1397–401.

Martin KS, Ghosh D, Page M, Wolff M, McMinimee K, Zhang M. What role do local grocery stores play in urban food environments? A case study of Hartford-Connecticut. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e94033.

Mayfield KE, Hession SL, Weatherspoon L, Hoerr SL. A cross-sectional analysis exploring differences between food availability, food price, food quality and store size and store location in Flint Michigan. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2020;15:643–57.

Meyerhoefer CD, Leibtag ES. A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down: the relationship between food prices and medical expenditures on diabetes. Am J Agr Econ. 2010;92:1271–82.

Monsivais P, Drewnowski A. The rising cost of low-energy-density foods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:2071–6.

Monsivais P, McLain J, Drewnowski A. The rising disparity in the price of healthful foods: 2004–2008. Food Policy. 2010;35:514–20.

Monsivais P, Perrigue MM, Adams SL, Drewnowski A. Measuring diet cost at the individual level: a comparison of three methods. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:1220–5.

Nansel TR, Lipsky LM, Eisenberg MH, Liu A, Mehta SN, Laffel LMB. Can families eat better without spending more? Improving diet quality does not increase diet cost in a randomized clinical trial among youth with type 1 diabetes and their parents. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:1751.

Otten JJ, Buszkiewicz J, Tang W, Anju A, Long M, Vigdor J, Drewnowski A. The impact of a city-level minimum-wage policy on supermarket food prices in Seattle-King County. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1039.

Richards R, Smith C. Shelter environment and placement in community affects lifestyle factors among homeless families in Minnesota. Am J Health Promot. 2006;21:36–44.

Shen Y, Clarke P, Gomez-Lopez IN, Hill AB, Romero DM, Goodspeed R, Berrocal VJ, Vydiswaran VV, Veinot TC. Using social media to assess the consumer nutrition environment: comparing Yelp reviews with a direct observation audit instrument for grocery stores. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22:257–64.

Smith C, Butterfass J, Richards R. Environment influences food access and resulting shopping and dietary behaviors among homeless Minnesotans living in food deserts. Agric Hum Values. 2010;27:141–61.

Spoden AL, Buszkiewicz JH, Drewnowski A, Long MC, Otten JJ. Seattle’s minimum wage ordinance did not affect supermarket food prices by food processing category. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:1762–70.

Stroebele-Benschop N, Wolf K, Palmer K, Kelley CJ, Jilcott Pitts SB. Comparison of food and beverage products’ availability, variety, price and quality in German and US supermarkets. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23:3387–93.

Townsend MS, Aaron GJ, Monsivais P, Keim NL, Drewnowski A. Less-energy-dense diets of low-income women in California are associated with higher energy-adjusted diet costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1220–6.

Wright L, Palak G, Yoshihara K. Accessibility and affordability of healthy foods in food deserts in Florida: policy and practice implications. Florida Public Health Review. 2018;15:98–103.

Yang Y, Leung P. Price premium or price discount for locally produced food products? A temporal analysis for Hawaii. J Asian Pac Econ. 2020;25:591–610.

Zenk SN, Grigsby-Toussaint DS, Curry SJ, Berbaum M, Schneider L. Short-term temporal stability in observed retail food characteristics. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42:26–32.

Abreu MD, Charlton K, Probst Y, Li N, Crino M, Wu JHY. Nutrient profiling and food prices: what is the cost of choosing healthier products? J Hum Nutr Diet. 2019;32:432–42.

Ball K, Timperio A, Crawford D. Neighbourhood socioeconomic inequalities in food access and affordability. Health Place. 2009;15:578–85.

Brimblecombe J, Ferguson M, Liberato SC, O’Dea K, Riley M. Optimisation modelling to assess cost of dietary improvement in remote aboriginal Australia. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e83587.

Chapman K, Innes-Hughes C, Goldsbury D, Kelly B, Bauman A, Allman-Farinelli M. A comparison of the cost of generic and branded food products in Australian supermarkets. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:894–900.

Cuttler R, Evans R, McClusky E, Purser L, Klassen KM, Palermo C. An investigation of the cost of food in the Geelong region of rural Victoria: essential data to support planning to improve access to nutritious food. Health Promot J Austr. 2019;30:124–7.

Ferguson M, O’Dea K, Chatfield M, Moodie M, Altman J, Brimblecombe J. The comparative cost of food and beverages at remote Indigenous communities, Northern Territory, Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40(Suppl 1):S21–6.

Ferguson M, O’Dea K, Holden S, Miles E, Brimblecombe J. Food and beverage price discounts to improve health in remote Aboriginal communities: mixed method evaluation of a natural experiment. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41:32–7.

Harrison MS, Coyne T, Lee AJ, Leonard D, Lowson S, Groos A, Ashton BA. The increasing cost of the basic foods required to promote health in Queensland. Med J Aust. 2007;186:9–14.

Kettings C, Sinclair AJ, Voevodin M. A healthy diet consistent with Australian health recommendations is too expensive for welfare-dependent families. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2009;33:566–72.

Lee A, Patay D, Herron L-M, Parnell Harrison E, Lewis M. Affordability of current, and healthy, more equitable, sustainable diets by area of socioeconomic disadvantage and remoteness in Queensland: insights into food choice. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:1–17.

Lee AJ, Kane S, Herron L-M, Matsuyama M, Lewis M. A tale of two cities: the cost, price-differential and affordability of current and healthy diets in Sydney and Canberra, Australia. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:1–13.

Palermo CE, Walker KZ, Hill P, McDonald J. The cost of healthy food in rural Victoria. Rural Remote Health. 2008;8. (1 December 2008).

Pollard CM, Landrigan TJ, Ellies PL, Kerr DA, Lester MLU, Goodchild SE. Geographic factors as determinants of food security: a Western Australian food pricing and quality study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2014;23:703–13.

Tsang A, Ndung’u MW, Coveney J, O’Dwyer L. Adelaide Healthy Food Basket: a survey on food cost, availability and affordability in five local government areas in metropolitan Adelaide, South Australia. Nutr Diet. 2007;64:241–7.

Walton K, do Rosario V, Kucherik M, Frean P, Richardson K, Turner M, Mahoney J, Charlton K, Andre do Rosario V. Identifying trends over time in food affordability: the Illawarra Healthy Food Basket survey, 2011–2019. Health Promot J Austr. 2021;1–1.

Ward PR, Coveney J, Verity F, Carter P, Schilling M. Cost and affordability of healthy food in rural South Australia. Rural Remote Health 2012;12. Article No. 1938.

Wong K, Coveney J, Ward P, Muller R, Carter P, Verity F, Tsourtos G. Availability, affordability and quality of a healthy food basket in Adelaide, South Australia. Nutr Diet. 2011;68:8–14.

Burns C, Sacks G, Gold L. Longitudinal study of Consumer Price Index (CPI) trends in core and non-core foods in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32:450–3.

Zorbas C, Lee A, Peeters A, Lewis M, Landrigan T, Backholer K. Streamlined data-gathering techniques to estimate the price and affordability of healthy and unhealthy diets under different pricing scenarios. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:1–11.

Conklin AI, Monsivais P, Khaw K, Wareham NJ, Forouhi NG. Dietary diversity, diet cost, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in the United Kingdom: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2016;13: e1002085.

Jones NRV, Tong TYN, Monsivais P. Meeting UK dietary recommendations is associated with higher estimated consumer food costs: an analysis using the National Diet and Nutrition Survey and consumer expenditure data, 2008–2012. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:948–56.

Lan H, Lloyd T, Morgan W, Dobson PW. Are food price promotions predictable? The hazard function of supermarket discounts. J Agric Econ. 2021;1.

Mackenbach JD, Burgoine T, Lakerveld J, Forouhi NG, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ, Monsivais P. Accessibility and affordability of supermarkets: associations with the DASH diet. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:55–62.

Monsivais P, Scarborough P, Lloyd T, Mizdrak A, Luben R, Mulligan AA, Wareham NJ, Woodcock J. Greater accordance with the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension dietary pattern is associated with lower diet-related greenhouse gas production but higher dietary costs in the United Kingdom. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:138–45.

Timmins KA, Hulme C, Cade JE. The monetary value of diets consumed by British adults: an exploration into sociodemographic differences in individual-level diet costs. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:151–9.

Timmins KA, Morris MA, Hulme C, Edwards KL, Clarke GP, Cade JE. Comparability of methods assigning monetary costs to diets: derivation from household till receipts versus cost database estimation using 4-day food diaries. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:1072–6.

Vogel C, Abbott G, Ntani G, Barker M, Cooper C, Moon G, Ball K, Baird J. Examination of how food environment and psychological factors interact in their relationship with dietary behaviours: test of a cross-sectional model. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16. N.PAG-N.PAG.

Kenny T-A, Fillion M, MacLean J, Wesche SD, Chan HM. Calories are cheap, nutrients are expensive – the challenge of healthy living in Arctic communities. Food Policy. 2018;80:39–54.

Latham J, Moffat T. Determinants of variation in food cost and availability in two socioeconomically contrasting neighbourhoods of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Health Place. 2007;13:273–87.

Lear SA, Gasevic D, Schuurman N. Association of supermarket characteristics with the body mass index of their shoppers. Nutr J. 2013;12. (13 August 2013).

Mah CL. Taylor N. Store patterns of availability and price of food and beverage products across a rural region of Newfoundland and Labrador. Canadian journal of public health = Revue canadienne de sante publique. 2020;111:247–256.

Minaker LM, Raine KD, Wild TC, Nykiforuk CIJ, Thompson ME, Frank LD. Objective food environments and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:289–96.

Minaker LM, Raine KD, Wild TC, Nykiforuk CIJ, Thompson ME, Frank LD. Construct validation of 4 food-environment assessment methods: adapting a multitrait-multimethod matrix approach for environmental measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:519–28.

Pakseresht M, Lang R, Rittmueller S, Roache C, Sheehy T, Batal M, Corriveau A, Sangita S. Food expenditure patterns in the Canadian Arctic show cause for concern for obesity and chronic disease. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11. (17 April 2014).

Mackay S, Buch T, Vandevijvere S, Goodwin R, Korohina E, Funaki-Tahifote M, Lee A, Swinburn B. Cost and affordability of diets modelled on current eating patterns and on dietary guidelines, for New Zealand total population, Māori and Pacific households. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15.

Mackay S, Vandevijvere S, Lee A. Ten-year trends in the price differential between healthier and less healthy foods in New Zealand. Nutrition & dietetics: the journal of the Dietitians Association of Australia. 2019;76:271–6.

Vandevijvere S, Young N, Mackay S, Swinburn B, Gahegan M. Modelling the cost differential between healthy and current diets: the New Zealand case study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:1–1.

Wilson N, Nghiem N, Mhurchu CN, Eyles H, Baker MG, Blakely T. Foods and dietary patterns that are healthy, low-cost, and environmentally sustainable: a case study of optimization modeling for New Zealand. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e59648.

Alexy U, Bolzenius K, Köpper A, Clausen K, Kersting M. Diet costs and energy density in the diet of German children and adolescents. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:1362–3.

Stroebele N, Dietze P, Tinnemann P, Willich SN. Assessing the variety and pricing of selected foods in socioeconomically disparate districts of Berlin, Germany. J Public Health. 2011;19:23–8.

Albuquerque G, Moreira P, Rosário R, Araújo A, Teixeira VH, Lopes O, Moreira A, Padrão P. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in children: Is it associated with economic cost? Porto biomedical journal. 2017;2:115–9.

Alves R, Lopes C, Rodrigues S, Perelman J. Adhering to a Mediterranean diet in a Mediterranean country: an excess cost for families? Br J Nutr. 2021;1–24.

Faria AP, Albuquerque G, Moreira P, Rosário R, Araújo A, Teixeira V, Barros R, Lopes Ó, Moreira A, Padrão P. Association between energy density and diet cost in children. Porto Biomed J. 2016;1:106–11.

Mackenbach JD, Dijkstra SC, Beulens JWJ, Seidell JC, Snijder MB, Stronks K, Monsivais P, Nicolaou M. Socioeconomic and ethnic differences in the relation between dietary costs and dietary quality: the HELIUS study. Nutr J. 2019;18. N.PAG-N.PAG.

Waterlander WE, de Haas WE, van Amstel I, Schuit AJ, Twisk JWR, Visser M, Seidell JC, Steenhuis IHM. Energy density, energy costs and income - how are they related? Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:1599–608.

Rydén P, Mattsson Sydner Y, Hagfors L. Counting the cost of healthy eating: a Swedish comparison of Mediterranean-style and ordinary diets. Int J Consum Stud. 2008;32:138–46.

Rydén PJ, Hagfors L. Diet cost, diet quality and socio-economic position: how are they related and what contributes to differences in diet costs? Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:1680–92.

Keiko S, Kentaro M, Hitomi O, Livingstone MBE, Satomi K, Hitomi S, Satoshi S. Nutritional correlates of monetary diet cost in young, middle-aged and older Japanese women. J Nutr Sci. 2017;6:1–11.

Bolarić M, Šatalić Z. The relation between food price, energy density and diet quality. Croatian Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2013;5:39–45.

Parlesak A, Tetens I, Jensen JD, Smed S, Blenkuš MG, Rayner M, Darmon N, Robertson A. Use of linear programming to develop cost-minimized nutritionally adequate health promoting food baskets. PLoS ONE. 2016;11: e0163411.