What Is Critical Thinking in Social Work?

- Career Advice

- Frustrations at Work

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Pinterest" aria-label="Share on Pinterest">

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Reddit" aria-label="Share on Reddit">

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Flipboard" aria-label="Share on Flipboard">

Effective Communication Skills for Social Workers

Top 5 values in being a social worker, legal & ethical issues facing social workers.

- Clinical Model Vs. Developmental Model in Social Work Practice

- Emotional Stresses of Being a Clinical Psychologist

Social workers offer many valuable services to people in need. They provide mental health services, such as diagnosis and counseling, advocate for clients who are unable to do so themselves, provide direct care services, such as housing assistance and help clients obtain social services benefits. The ability to remain open-minded and unbiased while gathering and interpreting data, otherwise known as critical thinking, is crucial for helping clients to the fullest extent possible. Critical thinking is one of the top skills required to be a successful social worker.

Meaning of Critical Thinking

The Foundation for Critical Thinking describes critical thinking as the ability to analyze, synthesize, evaluate and apply new information. Critical thinking in social work practice involves looking at a person or situation from an objective and neutral standpoint, without jumping to conclusions or making assumptions. Social workers spend their days observing, experiencing and reflecting on all that is happening around them.

In your role as a social worker, you obtain as much data as possible from interviews, case notes, observations, research, supervision and other means. Social workers must be self-aware of their feelings and beliefs. Stereotypical biases or prejudices must be recognized and not allowed to influence thinking when assembling a plan of action to help your clients to the highest level possible.

Importance of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is important for the development of social work skills in direct practice. Social workers help people from all walks of life and come across people or populations with experiences, ideas and opinions that often vary from their own culture and background. Clients may be misunderstood and misjudged if thinking critically does not take place in a social context.

Applying critical thinking and analysis in social work helps social workers formulate a treatment plan or intervention for working with a client. First, you need to consider the beliefs, thoughts or experiences that underlie your client's actions without making a snap decision. What seems crazy or irrational to you at first may in fact be better understood in the context of cultural and biopsychosocial factors that play a role in your client's life. Critical thinking helps you objectively examine these factors, consider their importance and impact on your course of action, while simultaneously maintaining professional detachment and a non-biased attitude.

Interrelated Critical Thinking Skills

To develop critical thinking skills as a social worker, you need to have the ability to self-reflect and observe your own behaviors and thoughts about a particular client or situation. Self-awareness, observation and critical thinking are closely intertwined and impact your ability to be an effective social worker. For example, observing your gut reactions and initial responses to a client without immediately taking action can help you identify transference and counter-transference reactions, which can have a negative or harmful impact on your client.

Self-reflection is particularly important when working with clients who have very different or very similar backgrounds and beliefs to your own. You don't want your abilities to be clouded by your own preconceived notions or biases. Likewise, you don't want to merge with a client with whom you over-identify because you come from very similar situations or have had similar experiences.

Purpose of Clinical Supervision

Social workers engage in clinical practice under professional supervision to hone their critical thinking abilities. According to the Administration for Children and Families , clinical supervision not only encourages critical thinking but also helps social workers develop other core social work skills. Clinical experiences focus on maintaining positive social work ethics, self-reflection and the ability to intervene in crises.

Many, if not most, social work settings require or, at least offer, the opportunity to participate in peer, individual or group supervision. Discussing your cases or clients with a supervisor or with colleagues can help you sort out your own opinions and judgments and prevent these issues from impacting your work.

- The Center for Critical Thinking: Defining Critical Thinking

- Administration for Children and Families: Clinical Supervision

Related Articles

Why acceptance is important as a social worker, how not to impose your values on clients, what are some assumptions for working as a social worker, skills needed to be a clinical social worker, distinguishing characteristics of social work, what qualities make a good developmental psychologist, social work interviewing skills, social counselor pay scale & education required, differences between psychologists & clinical social workers, most popular.

- 1 Why Acceptance Is Important as a Social Worker

- 2 How Not to Impose Your Values on Clients

- 3 What Are Some Assumptions for Working as a Social Worker?

- 4 Skills Needed to Be a Clinical Social Worker

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Critical Thinking and Professional Judgement for Social Work

- Lynne Rutter - Bournemouth University, UK

- Keith Brown - Bournemouth University, UK

- Description

Critical thinking can appear formal and academic, far removed from everyday life where decisions have to be taken quickly in less than ideal conditions. It is, however, a vital part of social work, and indeed any healthcare and leadership practice.

Taking a pragmatic look at the range of ideas associated with critical thinking, this Fifth Edition continues to focus on learning and development for practice. The authors discuss the importance of sound, moral judgement based on critical thinking and practical reasoning, and its application to different workplace situations; critical reflection, and its importance to academic work and practice; and the connection between critical thinking ideas and professionalism.

| ISBN: 9781526466990 | Electronic Version | Suggested Retail Price: $31.00 | Bookstore Price: $24.80 |

| ISBN: 9781526466969 | Paperback | Suggested Retail Price: $34.00 | Bookstore Price: $27.20 |

| ISBN: 9781526466952 | Hardcover | Suggested Retail Price: $112.00 | Bookstore Price: $89.60 |

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Good overview on foundational issues in social work eduction. Easy to read thus appropriate for ESL students. Chapter on critical style proved valuable as a guideline to literature reviews.

This book is written in such a way that it appears the authors are actually speaking to the students and in fact uses 'we' which is as if it is a collegial journey to learning. The content is relevent and is well informed, analytical in enough detail without being too intimidating for non-academic students.

This concise and clearly-written volume is useful across a range of early-career post-qualifying modules.

Very helpful introduction to some introductory reflective learning concepts.

Helpful addition to the students reading list for their unit of study

a concise, revised and accessible text for any NQSW practitioner re their evolving professional practice and beyond in terms of their continual professional development. Revisits key essential themes within a fresh context especially liked Chapters 3 and 4. A useful reference text for any Practice Educator, SW educator and ASYE assessor.

Preview this book

For instructors, select a purchasing option, related products.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Thinking Like a Social Worker: Examining the Meaning of Critical Thinking in Social Work

Critical thinking is frequently used to describe how social workers ought to reason. But how well has this concept helped us to develop a normative description of what it means to think like a social worker? This critical review mines the literature on critical thinking for insight into the kinds of thinking social work scholars consider important. Analysis indicates that critical thinking in social work is generally treated as a form of practical reasoning. Further, epistemological disagreements divide 2 distinct proposals for how practical reasoning in social work should proceed. Although these disagreements have received little attention in the literature, they have important implications for social work practice.

Related Papers

Journal of Teaching in Social Work

Michaela Rogers

Empathy Study

Helena Rocha

Teresa Aurora Carmona Scott

Vol. 4(2), 1-7

Kathiresan Loganathan

Social Work as an applied discipline aims to 'help people to help themselves'. Its knowledge base originates and thrives on western theories, perspectives, models and dimensions of various other disciplines, which is applied within the vast realms of social work practice. Theories of social work are broadly categorized into two types. The first one relates to theories that help social workers to understand individuals and their problems in various settings such as family, group, community and society; and thus help these professionals to intervene effectively. The second one deals with practice theories which are derived from the field. Many of these western oriented theories overlook the importance of socio-economic, cultural and political milieu of the non-western societies. While applying these theories, the practitioners thus face a multitude of challenges; and hence they tend to become dogmatic in their perseverance towards goal achievement. This paper argues that if critical reflection is used as a method of theorization, it would provide an inclusive approach (bottomup) as against the rigid deductive empirical (top-down) theories.

EDULEARN Proceedings

Inês Casquilho-Martins

Jeremiah Nyongesa

Brian Cooper

Summary This study is a preliminary definitional study that examines the idea of literacy and critical thinking in social work practice, especially as it applies to evidenced-based practice. It is not a definitive study as such, but more an exploration of what would constitute literacy and critical thinking in social work practice especially in a changing policy framework that requires greater accountability for practice through an evidence-based approach. The paper accepts the proposition that the essence of literacy is the communication of an idea or concept in a way others who are not familiar with that idea are able to understand it. The study examined five related areas, which would be considered important for the basis the background understanding required to participate in the evidenced-based discourse. These are critical thinking, statistical literacy, data visualisation, data literacy and information literacy. Findings Whilst there are differences in what is understood as literacy of the various areas, there are also commonalities between each area. The emphasis that evidenced-based practice will require in the mode and method of argument to be used will be based on the principles of argument that arise will be influenced by critical thinking, statistical literacy, data visualisation, data literacy or information literacy. Application The application of this preliminary study to social work practice is how one views and communicates information and observations to a wider audience. It provides a basis for argument for social work practice to be able to participate in a discourse dealing with evidence-based practice whilst within the ethical and values framework of social work philosophy. Key Words Critical thinking, statistical literacy, data visualisation, information literacy, evidenced-based practice, social work, disadvantage, spatial literacy

The Routledge Handbook of Critical Social Work

Christopher Thorpe

This chapter critically considers the steady turn away from social theory within social work generally, and the unintended consequences of this for critical social work specifically. Historically, social theoretical concepts and forms of argumentation have played a decisive role in shaping the ideational and normative agenda of critical social work. As the relationship between social work and social theory has steadily broken down, however, the latter has become increasingly (mis-)understood and (mis-)represented by the former. Herein, the argument is made that current (mis-)conceptions of social theory divert attention away from the fact that social workers ‘do’ a form of critical social theorizing all the time, albeit in ways that are actively and institutionally misrecognised. Putting to work various social theoretical concepts and forms of argumentation, the chapter calls for critical social workers to (re-)present the relationship between social work and social theory to social workers. Doing so constitutes a crucial step towards ameliorating the intellectual conditions of reception for the critical social work message.

Critical Social Work Praxis

Sobia Shaheen Shaikh

Chapter 1 of Critical Social Work Praxis, written by Brenda A. LeFrancois, Teresa Macias, and Sobia Shaheen Shaikh

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services

Lorraine Moya Salas

Social Sciences

Charlie O'Bree

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Find My Rep

You are here

Critical Thinking and Professional Judgement for Social Work

- Lynne Rutter - Bournemouth University, UK

- Keith Brown - Bournemouth University, UK

- Description

Critical thinking can appear formal and academic, far removed from everyday life where decisions have to be taken quickly in less than ideal conditions. It is, however, a vital part of social work, and indeed any healthcare and leadership practice.

Taking a pragmatic look at the range of ideas associated with critical thinking, this Fifth Edition continues to focus on learning and development for practice. The authors discuss the importance of sound, moral judgement based on critical thinking and practical reasoning, and its application to different workplace situations; critical reflection, and its importance to academic work and practice; and the connection between critical thinking ideas and professionalism.

Good overview on foundational issues in social work eduction. Easy to read thus appropriate for ESL students. Chapter on critical style proved valuable as a guideline to literature reviews.

This book is written in such a way that it appears the authors are actually speaking to the students and in fact uses 'we' which is as if it is a collegial journey to learning. The content is relevent and is well informed, analytical in enough detail without being too intimidating for non-academic students.

This concise and clearly-written volume is useful across a range of early-career post-qualifying modules.

Very helpful introduction to some introductory reflective learning concepts.

Helpful addition to the students reading list for their unit of study

a concise, revised and accessible text for any NQSW practitioner re their evolving professional practice and beyond in terms of their continual professional development. Revisits key essential themes within a fresh context especially liked Chapters 3 and 4. A useful reference text for any Practice Educator, SW educator and ASYE assessor.

Preview this book

For instructors.

Please select a format:

Select a Purchasing Option

- Electronic Order Options VitalSource Amazon Kindle Google Play eBooks.com Kobo

What Are Critical Thinking Skills and Why Are They Important?

Learn what critical thinking skills are, why they’re important, and how to develop and apply them in your workplace and everyday life.

![what is critical thinking in social work [Featured Image]: Project Manager, approaching and analyzing the latest project with a team member,](https://d3njjcbhbojbot.cloudfront.net/api/utilities/v1/imageproxy/https://images.ctfassets.net/wp1lcwdav1p1/1SOj8kON2XLXVb6u3bmDwN/62a5b68b69ec07b192de34b7ce8fa28a/GettyImages-598260236.jpg?w=1500&h=680&q=60&fit=fill&f=faces&fm=jpg&fl=progressive&auto=format%2Ccompress&dpr=1&w=1000)

We often use critical thinking skills without even realizing it. When you make a decision, such as which cereal to eat for breakfast, you're using critical thinking to determine the best option for you that day.

Critical thinking is like a muscle that can be exercised and built over time. It is a skill that can help propel your career to new heights. You'll be able to solve workplace issues, use trial and error to troubleshoot ideas, and more.

We'll take you through what it is and some examples so you can begin your journey in mastering this skill.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is the ability to interpret, evaluate, and analyze facts and information that are available, to form a judgment or decide if something is right or wrong.

More than just being curious about the world around you, critical thinkers make connections between logical ideas to see the bigger picture. Building your critical thinking skills means being able to advocate your ideas and opinions, present them in a logical fashion, and make decisions for improvement.

Build job-ready skills with a Coursera Plus subscription

- Get access to 7,000+ learning programs from world-class universities and companies, including Google, Yale, Salesforce, and more

- Try different courses and find your best fit at no additional cost

- Earn certificates for learning programs you complete

- A subscription price of $59/month, cancel anytime

Why is critical thinking important?

Critical thinking is useful in many areas of your life, including your career. It makes you a well-rounded individual, one who has looked at all of their options and possible solutions before making a choice.

According to the University of the People in California, having critical thinking skills is important because they are [ 1 ]:

Crucial for the economy

Essential for improving language and presentation skills

Very helpful in promoting creativity

Important for self-reflection

The basis of science and democracy

Critical thinking skills are used every day in a myriad of ways and can be applied to situations such as a CEO approaching a group project or a nurse deciding in which order to treat their patients.

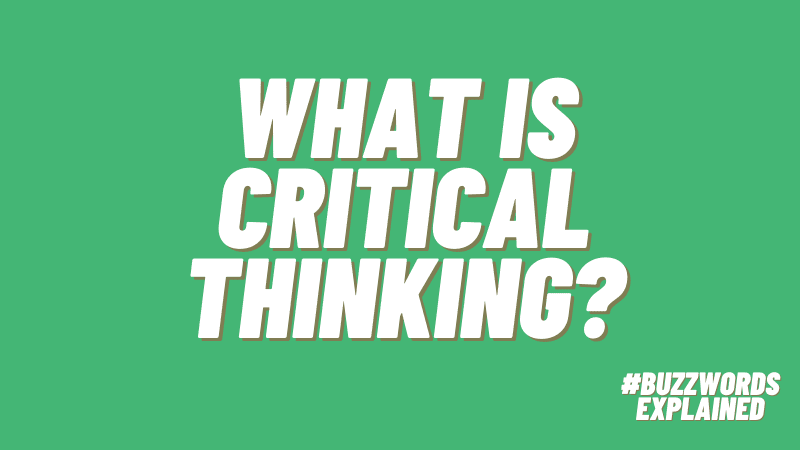

Examples of common critical thinking skills

Critical thinking skills differ from individual to individual and are utilized in various ways. Examples of common critical thinking skills include:

Identification of biases: Identifying biases means knowing there are certain people or things that may have an unfair prejudice or influence on the situation at hand. Pointing out these biases helps to remove them from contention when it comes to solving the problem and allows you to see things from a different perspective.

Research: Researching details and facts allows you to be prepared when presenting your information to people. You’ll know exactly what you’re talking about due to the time you’ve spent with the subject material, and you’ll be well-spoken and know what questions to ask to gain more knowledge. When researching, always use credible sources and factual information.

Open-mindedness: Being open-minded when having a conversation or participating in a group activity is crucial to success. Dismissing someone else’s ideas before you’ve heard them will inhibit you from progressing to a solution, and will often create animosity. If you truly want to solve a problem, you need to be willing to hear everyone’s opinions and ideas if you want them to hear yours.

Analysis: Analyzing your research will lead to you having a better understanding of the things you’ve heard and read. As a true critical thinker, you’ll want to seek out the truth and get to the source of issues. It’s important to avoid taking things at face value and always dig deeper.

Problem-solving: Problem-solving is perhaps the most important skill that critical thinkers can possess. The ability to solve issues and bounce back from conflict is what helps you succeed, be a leader, and effect change. One way to properly solve problems is to first recognize there’s a problem that needs solving. By determining the issue at hand, you can then analyze it and come up with several potential solutions.

How to develop critical thinking skills

You can develop critical thinking skills every day if you approach problems in a logical manner. Here are a few ways you can start your path to improvement:

1. Ask questions.

Be inquisitive about everything. Maintain a neutral perspective and develop a natural curiosity, so you can ask questions that develop your understanding of the situation or task at hand. The more details, facts, and information you have, the better informed you are to make decisions.

2. Practice active listening.

Utilize active listening techniques, which are founded in empathy, to really listen to what the other person is saying. Critical thinking, in part, is the cognitive process of reading the situation: the words coming out of their mouth, their body language, their reactions to your own words. Then, you might paraphrase to clarify what they're saying, so both of you agree you're on the same page.

3. Develop your logic and reasoning.

This is perhaps a more abstract task that requires practice and long-term development. However, think of a schoolteacher assessing the classroom to determine how to energize the lesson. There's options such as playing a game, watching a video, or challenging the students with a reward system. Using logic, you might decide that the reward system will take up too much time and is not an immediate fix. A video is not exactly relevant at this time. So, the teacher decides to play a simple word association game.

Scenarios like this happen every day, so next time, you can be more aware of what will work and what won't. Over time, developing your logic and reasoning will strengthen your critical thinking skills.

Learn tips and tricks on how to become a better critical thinker and problem solver through online courses from notable educational institutions on Coursera. Start with Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking from Duke University or Mindware: Critical Thinking for the Information Age from the University of Michigan.

Article sources

University of the People, “ Why is Critical Thinking Important?: A Survival Guide , https://www.uopeople.edu/blog/why-is-critical-thinking-important/.” Accessed May 18, 2023.

Keep reading

Coursera staff.

Editorial Team

Coursera’s editorial team is comprised of highly experienced professional editors, writers, and fact...

This content has been made available for informational purposes only. Learners are advised to conduct additional research to ensure that courses and other credentials pursued meet their personal, professional, and financial goals.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

NEW: Classroom Clean-Up/Set-Up Email Course! 🧽

What Is Critical Thinking and Why Do We Need To Teach It?

Question the world and sort out fact from opinion.

The world is full of information (and misinformation) from books, TV, magazines, newspapers, online articles, social media, and more. Everyone has their own opinions, and these opinions are frequently presented as facts. Making informed choices is more important than ever, and that takes strong critical thinking skills. But what exactly is critical thinking? Why should we teach it to our students? Read on to find out.

What is critical thinking?

Source: Indeed

Critical thinking is the ability to examine a subject and develop an informed opinion about it. It’s about asking questions, then looking closely at the answers to form conclusions that are backed by provable facts, not just “gut feelings” and opinion. These skills allow us to confidently navigate a world full of persuasive advertisements, opinions presented as facts, and confusing and contradictory information.

The Foundation for Critical Thinking says, “Critical thinking can be seen as having two components: 1) a set of information and belief-generating and processing skills, and 2) the habit, based on intellectual commitment, of using those skills to guide behavior.”

In other words, good critical thinkers know how to analyze and evaluate information, breaking it down to separate fact from opinion. After a thorough analysis, they feel confident forming their own opinions on a subject. And what’s more, critical thinkers use these skills regularly in their daily lives. Rather than jumping to conclusions or being guided by initial reactions, they’ve formed the habit of applying their critical thinking skills to all new information and topics.

Why is critical thinking so important?

Imagine you’re shopping for a new car. It’s a big purchase, so you want to do your research thoroughly. There’s a lot of information out there, and it’s up to you to sort through it all.

- You’ve seen TV commercials for a couple of car models that look really cool and have features you like, such as good gas mileage. Plus, your favorite celebrity drives that car!

- The manufacturer’s website has a lot of information, like cost, MPG, and other details. It also mentions that this car has been ranked “best in its class.”

- Your neighbor down the street used to have this kind of car, but he tells you that he eventually got rid of it because he didn’t think it was comfortable to drive. Plus, he heard that brand of car isn’t as good as it used to be.

- Three independent organizations have done test-drives and published their findings online. They all agree that the car has good gas mileage and a sleek design. But they each have their own concerns or complaints about the car, including one that found it might not be safe in high winds.

So much information! It’s tempting to just go with your gut and buy the car that looks the coolest (or is the cheapest, or says it has the best gas mileage). Ultimately, though, you know you need to slow down and take your time, or you could wind up making a mistake that costs you thousands of dollars. You need to think critically to make an informed choice.

What does critical thinking look like?

Source: TeachThought

Let’s continue with the car analogy, and apply some critical thinking to the situation.

- Critical thinkers know they can’t trust TV commercials to help them make smart choices, since every single one wants you to think their car is the best option.

- The manufacturer’s website will have some details that are proven facts, but other statements that are hard to prove or clearly just opinions. Which information is factual, and even more important, relevant to your choice?

- A neighbor’s stories are anecdotal, so they may or may not be useful. They’re the opinions and experiences of just one person and might not be representative of a whole. Can you find other people with similar experiences that point to a pattern?

- The independent studies could be trustworthy, although it depends on who conducted them and why. Closer analysis might show that the most positive study was conducted by a company hired by the car manufacturer itself. Who conducted each study, and why?

Did you notice all the questions that started to pop up? That’s what critical thinking is about: asking the right questions, and knowing how to find and evaluate the answers to those questions.

Good critical thinkers do this sort of analysis every day, on all sorts of subjects. They seek out proven facts and trusted sources, weigh the options, and then make a choice and form their own opinions. It’s a process that becomes automatic over time; experienced critical thinkers question everything thoughtfully, with purpose. This helps them feel confident that their informed opinions and choices are the right ones for them.

Key Critical Thinking Skills

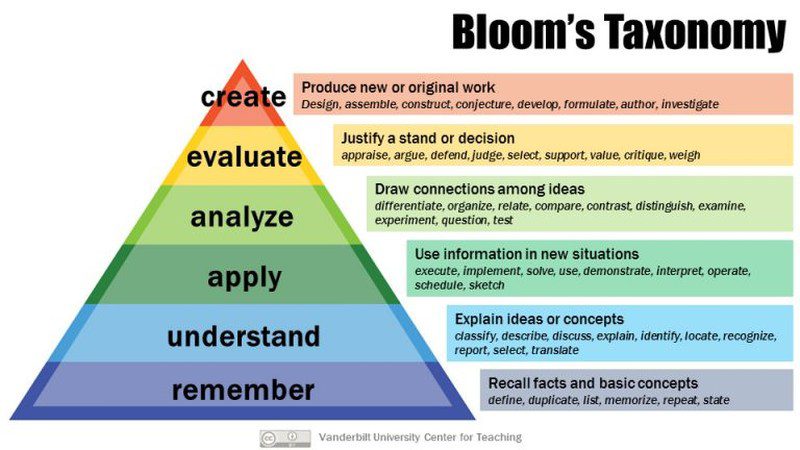

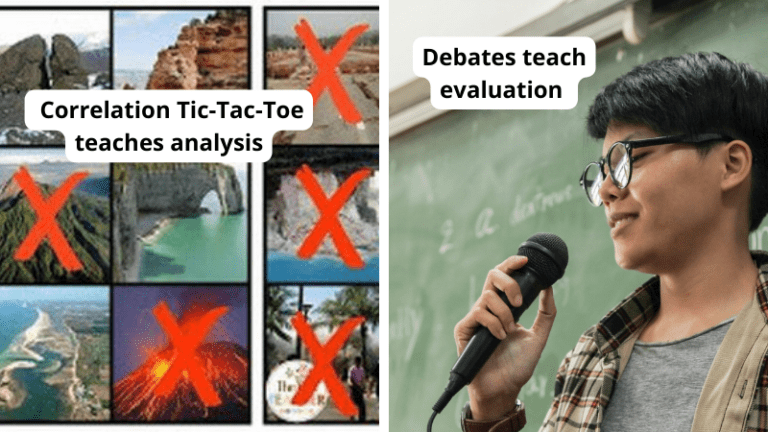

There’s no official list, but many people use Bloom’s Taxonomy to help lay out the skills kids should develop as they grow up.

Source: Vanderbilt University

Bloom’s Taxonomy is laid out as a pyramid, with foundational skills at the bottom providing a base for more advanced skills higher up. The lowest phase, “Remember,” doesn’t require much critical thinking. These are skills like memorizing math facts, defining vocabulary words, or knowing the main characters and basic plot points of a story.

Higher skills on Bloom’s list incorporate more critical thinking.

True understanding is more than memorization or reciting facts. It’s the difference between a child reciting by rote “one times four is four, two times four is eight, three times four is twelve,” versus recognizing that multiplication is the same as adding a number to itself a certain number of times. When you understand a concept, you can explain how it works to someone else.

When you apply your knowledge, you take a concept you’ve already mastered and apply it to new situations. For instance, a student learning to read doesn’t need to memorize every word. Instead, they use their skills in sounding out letters to tackle each new word as they come across it.

When we analyze something, we don’t take it at face value. Analysis requires us to find facts that stand up to inquiry. We put aside personal feelings or beliefs, and instead identify and scrutinize primary sources for information. This is a complex skill, one we hone throughout our entire lives.

Evaluating means reflecting on analyzed information, selecting the most relevant and reliable facts to help us make choices or form opinions. True evaluation requires us to put aside our own biases and accept that there may be other valid points of view, even if we don’t necessarily agree with them.

Finally, critical thinkers are ready to create their own result. They can make a choice, form an opinion, cast a vote, write a thesis, debate a topic, and more. And they can do it with the confidence that comes from approaching the topic critically.

How do you teach critical thinking skills?

The best way to create a future generation of critical thinkers is to encourage them to ask lots of questions. Then, show them how to find the answers by choosing reliable primary sources. Require them to justify their opinions with provable facts, and help them identify bias in themselves and others. Try some of these resources to get started.

5 Critical Thinking Skills Every Kid Needs To Learn (And How To Teach Them)

- 100+ Critical Thinking Questions for Students To Ask About Anything

- 10 Tips for Teaching Kids To Be Awesome Critical Thinkers

- Free Critical Thinking Poster, Rubric, and Assessment Ideas

More Critical Thinking Resources

The answer to “What is critical thinking?” is a complex one. These resources can help you dig more deeply into the concept and hone your own skills.

- The Foundation for Critical Thinking

- Cultivating a Critical Thinking Mindset (PDF)

- Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking (Browne/Keeley, 2014)

Have more questions about what critical thinking is or how to teach it in your classroom? Join the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook to ask for advice and share ideas!

Plus, 12 skills students can work on now to help them in careers later ..

You Might Also Like

Teach them to thoughtfully question the world around them. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Constructivism Learning Theory & Philosophy of Education

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Constructivism is a learning theory that emphasizes the active role of learners in building their own understanding. Rather than passively receiving information, learners reflect on their experiences, create mental representations , and incorporate new knowledge into their schemas . This promotes deeper learning and understanding.

Constructivism is ‘an approach to learning that holds that people actively construct or make their own knowledge and that reality is determined by the experiences of the learner’ (Elliott et al., 2000, p. 256).

In elaborating on constructivists’ ideas, Arends (1998) states that constructivism believes in the personal construction of meaning by the learner through experience and that meaning is influenced by the interaction of prior knowledge and new events.

Constructivism Philosophy

Knowledge is constructed rather than innate, or passively absorbed.

Constructivism’s central idea is that human learning is constructed, that learners build new knowledge upon the foundation of previous learning.

This prior knowledge influences what new or modified knowledge an individual will construct from new learning experiences (Phillips, 1995).

Learning is an active process.

The second notion is that learning is an active rather than a passive process.

The passive view of teaching views the learner as ‘an empty vessel’ to be filled with knowledge, whereas constructivism states that learners construct meaning only through active engagement with the world (such as experiments or real-world problem-solving).

Information may be passively received, but understanding cannot be, for it must come from making meaningful connections between prior knowledge, new knowledge, and the processes involved in learning.

John Dewey valued real-life contexts and problems as an educational experience. He believed that if students only passively perceive a problem and do not experience its consequences in a meaningful, emotional, and reflective way, they are unlikely to adapt and revise their habits or construct new habits, or will only do so superficially.

All knowledge is socially constructed.

Learning is a social activity – it is something we do together, in interaction with each other, rather than an abstract concept (Dewey, 1938).

For example, Vygotsky (1978) believed that community plays a central role in the process of “making meaning.” For Vygotsky, the environment in which children grow up will influence how they think and what they think about.

Thus, all teaching and learning is a matter of sharing and negotiating socially constituted knowledge.

For example, Vygotsky (1978) states cognitive development stems from social interactions from guided learning within the zone of proximal development as children and their partners co-construct knowledge.

All knowledge is personal.

Each individual learner has a distinctive point of view, based on existing knowledge and values.

This means that same lesson, teaching or activity may result in different learning by each pupil, as their subjective interpretations differ.

This principle appears to contradict the view the knowledge is socially constructed.

Fox (2001, p. 30) argues:

- Although individuals have their own personal history of learning, nevertheless they can share in common knowledge, and

- Although education is a social process powerfully influenced by cultural factors, cultures are made up of sub-cultures, even to the point of being composed of sub-cultures of one.

- Cultures and their knowledge base are constantly in a process of change and the knowledge stored by individuals is not a rigid copy of some socially constructed template. In learning a culture, each child changes that culture.

Learning exists in the mind.

The constructivist theory posits that knowledge can only exist within the human mind, and that it does not have to match any real-world reality (Driscoll, 2000).

Learners will be constantly trying to develop their own individual mental model of the real world from their perceptions of that world.

As they perceive each new experience, learners will continually update their own mental models to reflect the new information, and will, therefore, construct their own interpretation of reality.

Types of Constructivism

Typically, this continuum is divided into three broad categories: Cognitive constructivism, based on the work of Jean Piaget ; social constructivism, based on the work of Lev Vygotsky; and radical constructivism.

According to the GSI Teaching and Resource Center (2015, p.5):

Cognitive constructivism states knowledge is something that is actively constructed by learners based on their existing cognitive structures. Therefore, learning is relative to their stage of cognitive development.

Cognitivist teaching methods aim to assist students in assimilating new information to existing knowledge, and enabling them to make the appropriate modifications to their existing intellectual framework to accommodate that information.

According to social constructivism, learning is a collaborative process, and knowledge develops from individuals” interactions with their culture and society.

Social constructivism was developed by Lev Vygotsky (1978, p. 57), who suggested that:

Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level and, later on, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological).

The notion of radical constructivism was developed by Ernst von Glasersfeld (1974) and states that all knowledge is constructed rather than perceived through senses.

Learners construct new knowledge on the foundations of their existing knowledge. However, radical constructivism states that the knowledge individuals create tells us nothing about reality, and only helps us to function in your environment. Thus, knowledge is invented not discovered.

Radical constructivism also argues that there is no way to directly access an objective reality, and that knowledge can only be understood through the individual’s subjective interpretation of their experiences.

This theory asserts that individuals create their own understanding of reality, and that their knowledge is always incomplete and subjective.

The humanly constructed reality is all the time being modified and interacting to fit ontological reality, although it can never give a ‘true picture’ of it. (Ernest, 1994, p. 8)

| Knowledge is created through social interactions and collaboration with others. | Knowledge is constructed through mental processes such as attention, perception, and memory. | Knowledge is constructed by the individual through their subjective experiences and interactions with the world. |

| The learner is an active participant in the construction of knowledge and learning is a social process. | The learner is an active problem-solver who constructs knowledge through mental processes. | The learner is the sole constructor of knowledge and meaning, and their reality is subjective and constantly evolving. |

| The teacher facilitates learning by providing opportunities for social interaction and collaboration. | The teacher provides information and resources for the learner to construct their own understanding. | The teacher encourages the learner to question and reflect on their experiences to construct their own knowledge. |

| Learning is a social process that involves collaboration, negotiation, and reflection. | Learning is an individual process that involves mental processes such as attention, perception, and memory. | Learning is an individual and subjective process that involves constructing meaning from one’s experiences. |

| Reality is socially constructed and subjective, and there is no one objective truth. | Reality is objective and exists independently of the learner, but the learner constructs their own understanding of it. | Reality is subjective and constantly evolving, and there is no one objective truth. |

| For example: Collaborative group work in a classroom setting. | For example: Solving a math problem using mental processes. | For example: Reflecting on personal experiences to construct meaning and understanding. |

Constructivism Teaching Philosophy

Constructivist learning theory underpins a variety of student-centered teaching methods and techniques which contrast with traditional education, whereby knowledge is simply passively transmitted by teachers to students.

What is the role of the teacher in a constructivist classroom?

Constructivism is a way of teaching where instead of just telling students what to believe, teachers encourage them to think for themselves. This means that teachers need to believe that students are capable of thinking and coming up with their own ideas. Unfortunately, not all teachers believe this yet in America.

The primary responsibility of the teacher is to create a collaborative problem-solving environment where students become active participants in their own learning.

From this perspective, a teacher acts as a facilitator of learning rather than an instructor.

The teacher makes sure he/she understands the students” preexisting conceptions, and guides the activity to address them and then build on them (Oliver, 2000).

Scaffolding is a key feature of effective teaching, where the adult continually adjusts the level of his or her help in response to the learner’s level of performance.

In the classroom, scaffolding can include modeling a skill, providing hints or cues, and adapting material or activity (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009).

What are the features of a constructivist classroom?

A constructivist classroom emphasizes active learning, collaboration, viewing a concept or problem from multiple perspectives, reflection, student-centeredness, and authentic assessment to promote meaningful learning and help students construct their own understanding of the world.

Tam (2000) lists the following four basic characteristics of constructivist learning environments, which must be considered when implementing constructivist teaching strategies:

1) Knowledge will be shared between teachers and students. 2) Teachers and students will share authority. 3) The teacher’s role is one of a facilitator or guide. 4) Learning groups will consist of small numbers of heterogeneous students.

| Traditional Classroom | Constructivist Classroom |

|---|---|

| Strict adherence to a fixed curriculum is highly valued. | Pursuit of student questions and interests is valued. |

| Learning is based on repetition. | Learning is interactive, building on what the student already knows. |

| Teacher-centered. | Student-centered. |

| Teachers disseminate information to students; students are recipients of knowledge (passive learning). | Teachers have a dialogue with students, helping students construct their own knowledge (active learning). |

| Teacher’s role is directive, rooted in authority. | Teacher’s role is interactive, rooted in negotiation. |

| Students work primarily alone (competitive). | Students work primarily in groups (cooperative) and learn from each other. |

What are the pedagogical (i.e., teaching) goals of constructivist classrooms?

Honebein (1996) summarizes the seven pedagogical goals of constructivist learning environments:

- To provide experience with the knowledge construction process (students determine how they will learn).

- To provide experience in and appreciation for multiple perspectives (evaluation of alternative solutions).

- To embed learning in realistic contexts (authentic tasks).

- To encourage ownership and a voice in the learning process (student-centered learning).

- To embed learning in social experience (collaboration).

- To encourage the use of multiple modes of representation, (video, audio text, etc.)

- To encourage awareness of the knowledge construction process (reflection, metacognition).

Brooks and Brooks (1993) list twelve descriptors of constructivist teaching behaviors:

- Encourage and accept student autonomy and initiative. (p. 103)

- Use raw data and primary sources, along with manipulative, interactive, and physical materials. (p. 104)

- When framing tasks, use cognitive terminology such as “classify,” analyze,” “predict,” and “create.” (p. 104)

- Allow student responses to drive lessons, shift instructional strategies, and alter content. (p. 105)

- Inquire about students’ understandings of the concepts before sharing [your] own understandings of those concepts. (p. 107)

- Encourage students to engage in dialogue, both with the teacher and with one another. (p. 108)

- Encourage student inquiry by asking thoughtful, open-ended questions and encouraging students to ask questions of each other. (p. 110)

- Seek elaboration of students’ initial responses. (p. 111)

- Engage students in experiences that might engender contradictions to their initial hypotheses and then encourage discussion. (p. 112)

- Allow wait time after posing questions. (p. 114)

- Provide time for students to construct relationships and create metaphors. (p. 115)

- Nurture students’ natural curiosity through frequent use of the learning cycle model. (p. 116)

Critical Evaluation

Constructivism promotes a sense of personal agency as students have ownership of their learning and assessment.

The biggest disadvantage is its lack of structure. Some students require highly structured learning environments to be able to reach their potential.

It also removes grading in the traditional way and instead places more value on students evaluating their own progress, which may lead to students falling behind, as without standardized grading teachers may not know which students are struggling.

Summary Tables

| Behaviourism | Constructivism |

|---|---|

| Emphasizes the role of the environment and external factors in behavior | Emphasizes the role of internal mental processes in learning and knowledge creation |

| Knowledge is gained through external stimuli and observable behaviors | Knowledge is actively constructed by the individual based on their experiences |

| Teachers are the authority figures who impart knowledge to students | Teachers are facilitators who guide students in constructing their own knowledge |

| Students are passive receivers of knowledge and respond to rewards/punishments | Students are active participants in constructing their own understanding and knowledge |

| Observable behavior and measurable outcomes | Internal mental processes, thinking, and reasoning |

| Evaluation is based on observable behavior and measurable outcomes | Evaluation is based on individual understanding and internal mental processes |

| Classical and operant conditioning, behavior modification, reinforcement | Problem-based learning, inquiry-based learning, cognitive apprenticeship |

| Constructivism | Cognitivism |

|---|---|

| Emphasizes the active role of learners in constructing their own understanding | Emphasizes the role of internal mental processes in learning and the acquisition of knowledge |

| Knowledge is actively constructed by the learner based on their experiences | Knowledge is a product of internal mental processes and can be objectively measured and assessed |

| Teachers are facilitators who guide learners in constructing their own knowledge | Teachers are experts who provide knowledge to learners and guide them in developing their cognitive abilities |

| Students are active participants in constructing their own understanding | Students are receivers of knowledge from teachers and use their cognitive abilities to process information |

| Active construction of knowledge based on experiences | Internal mental processes and information processing |

| Evaluation is based on individual understanding and internal mental processes | Evaluation is based on objectively measurable outcomes and mastery of specific knowledge and skills |

| Problem-based learning, inquiry-based learning, cognitive apprenticeship | Information processing theory, schema theory, metacognition |

What is constructivism in the philosophy of education?

Constructivism in the philosophy of education is the belief that learners actively construct their own knowledge and understanding of the world through their experiences, interactions, and reflections.

It emphasizes the importance of learner-centered approaches, hands-on activities, and collaborative learning to facilitate meaningful and authentic learning experiences.

How would a constructivist teacher explain 1/3÷1/3?

They might engage students in hands-on activities, such as using manipulatives or visual representations, to explore the concept visually and tangibly.

The teacher would encourage discussions among students, allowing them to share their ideas and perspectives, and guide them toward discovering the relationship between dividing by a fraction and multiplying by its reciprocal.

Through guided questioning, the teacher would facilitate critical thinking and help students arrive at the understanding that dividing 1/3 by 1/3 is equivalent to multiplying by the reciprocal, resulting in a value of 1.

Arends, R. I. (1998). Resource handbook. Learning to teach (4th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Brooks, J., & Brooks, M. (1993). In search of understanding: the case for constructivist classrooms, ASCD. NDT Resource Center database .

Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs . Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Dewey, J. (1938) Experience and Education . New York: Collier Books.

Driscoll, M. (2000). Psychology of Learning for Instruction . Boston: Allyn& Bacon

Elliott, S.N., Kratochwill, T.R., Littlefield Cook, J. & Travers, J. (2000). Educational psychology: Effective teaching, effective learning (3rd ed.) . Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill College.

Ernest, P. (1994). Varieties of constructivism: Their metaphors, epistemologies and pedagogical implications. Hiroshima Journal of Mathematics Education, 2 (1994), 2.

Fox, R. (2001). Constructivism examined . Oxford review of education, 27(1) , 23-35.

Honebein, P. C. (1996). Seven goals for the design of constructivist learning environments. Constructivist learning environments : Case studies in instructional design, 11-24.

Oliver, K. M. (2000). Methods for developing constructivism learning on the web. Educational Technology, 40 (6)

Phillips, D. C. (1995). The good, the bad, and the ugly: The many faces of constructivism . Educational researcher, 24 (7), 5-12.

Tam, M. (2000). Constructivism, Instructional Design, and Technology: Implications for Transforming Distance Learning. Educational Technology and Society, 3 (2).

Teaching Guide for GSIs. Learning: Theory and Research (2016). Retrieved from http://gsi.berkeley.edu/media/Learning.pdf

von Glasersfeld, E. V. (1974). Piaget and the radical constructivist epistemology . Epistemology and education , 1-24.

von Glasersfeld, E. (1994). A radical constructivist view of basic mathematical concepts. Constructing mathematical knowledge: Epistemology and mathematics education, 5-7.

Von Glasersfeld, E. (2013). Radical constructivism (Vol. 6). Routledge.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Further Reading

Constructivist Teaching Methods

Constructivism Learning Theory: A Paradigm for Teaching and Learning Strategies Which Can be Implemented by Teachers When Planning Constructivist Opportunities in the Classroom

Related Articles

Child Psychology

Vygotsky vs. Piaget: A Paradigm Shift

Interactional Synchrony

Internal Working Models of Attachment

Learning Theory of Attachment

Stages of Attachment Identified by John Bowlby And Schaffer & Emerson (1964)

Child Psychology , Personality

How Anxious Ambivalent Attachment Develops in Children

- Critical Thinking

Thinking Like a Social Worker: Examining the Meaning of Critical Thinking in Social Work

- Journal of Social Work Education 51(3):457-474

- 51(3):457-474

- Florida State University

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Michelle D. DiLauro

- D Rheinheimer

- CHILD FAM SOC WORK

- Magdalena Troncoso del Río

- Elda Savoie

- Jane Maidment

- Pamela Stowers Johansen

- Tina U. Hancock

- Etty Vandsburger

- Hugh G. Clark

- Robert C. Kersting

- Ann Marie Mumm

- RES SOCIAL WORK PRAC

- Marie Thielke Huff

- Karl R. Popper

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Need to start saving with a new ATS? Learn how to calculate the return on investment of your ATS Calculate ROI now

- HR Toolkit |

- Definitions |

What are soft skills?

Soft skills are general traits not specific to any job, helping employees excel in any workplace. They include communication, teamwork, and adaptability, often termed as transferable or interpersonal skills. They’re essential for professional success.

An experienced recruiter and HR professional who has transferred her expertise to insightful content to support others in HR.

At a minimum, employees need role-specific knowledge and abilities to perform their job duties. But, those who usually stand out as high performers need some additional qualities, such as the ability to communicate clearly, the ability to work well with others and the ability to manage their time effectively. These abilities are examples of soft skills.

Neil Carberry , Director for Employment and Skills at CBI , talks about the balance between attitude and technical skills: “Business is clear that developing the right attitudes and attributes in people – such as resilience, respect, enthusiasm, and creativity – is just as important as academic or technical skills. In an ever more competitive jobs market it is such qualities that will give our young talent a head start and also allow existing employees to progress to higher skilled, better-paid roles”.

According to research conducted by Harvard University, 85% of job success comes from having well-developed soft and people skills , with only 15% attributed to technical skills. This underlines the substantial impact soft skills have on professional success.

In addition, Deloitte’s research indicates that jobs requiring intensive soft skills are expected to grow 2.5 times faster than other job types. By 2030, it is predicted that 63% of all jobs will be comprised of soft skills roles, showcasing the growing demand for these competencies in the labor market.

Get our new HRIS Buyer's Guide

Learn what an HRIS is, what features to look for, and how it can help you so you can make the right decision in getting this crucial HR software.

Download your guide now

- 15 soft skills examples that are essential traits among employees

Why are soft skills important?

How do you assess soft skills in candidates, here are 15 soft skills examples that are essential traits among employees:.

- Communication

- Problem-solving

- Time management

- Critical thinking

- Decision-making

- Organizational

- Stress management

- Adaptability

- Conflict management

- Resourcefulness

- Openness to criticism

Forbes adds to the above Emotional Intelligence and Work Ethic, which are as important as the others mentioned.

Move the right people forward faster

Easily collaborate with hiring teams to evaluate applicants, gather fair and consistent feedback, check for unconscious bias, and decide who’s the best fit, all in one system.

Start evaluating candidates

In job ads, it’s common to include requirements such as “communication skills” or “a problem-solving attitude”. That’s because soft skills help you:

- Example: An employee with good time management skills knows how to prioritize tasks to meet deadlines.

- Example: When two candidates have a similar academic and professional background, you’re more likely to hire the one who’s more collaborative and flexible.

- Example: For a junior position, it makes sense to look for candidates with a “willingness to learn” and an “adaptive personality”, as opposed to hiring an expert.

- Example: When hiring a salesperson, you want to find a candidate who’s familiar with the industry and has experience in sales, but is also resilient, knows how to negotiate and has excellent verbal communication abilities.

- Example: If you value accountability and you want to have employees who can take initiative, it’s important to look for candidates who are not afraid to take ownership of their job, who are decisive and have a problem-solving aptitude.

How to evaluate soft skills in the workplace

Identifying and assessing soft skills in candidates is no easy feat: those qualities are often intangible and can’t be measured by simply looking at what soft skills each candidate includes in their resume. Besides, candidates will try to present themselves as positively as possible during interviews, so it’s your job to dig deeper to uncover what they can really bring to the table in terms of soft skills.

1. Know what you’re looking for in potential hires beforehand and ask all candidates the same questions.

Before starting your interview process for an open role, consider what kind of soft skills are important in this role and prepare specific questions to assess those skills. This step is important for you to evaluate all candidates objectively. For example, in a sales role, good communication is key. By preparing specific questions that evaluate how candidates use their communication skills on the job, you’re more likely to find someone who can actually communicate with clients effectively, instead of hiring someone who only appears so (e.g. because they’re extroverted).

To help you out, we gathered examples of soft skills questions that test specific skills:

- Adaptability interview questions

- Analytical interview questions

- Change management interview questions

- Communication interview questions

- Critical-thinking interview questions

- Decision-making interview questions

- Leadership interview questions

- Presentation interview questions

- Problem-solving interview questions

- Team player interview questions

2. Ask behavioral questions to learn how they’ve used soft skills in previous jobs.

Past behaviors indicate how candidates behave in business settings, so they can be used as a soft skill assessment, too. For example, you can ask targeted questions to learn how candidates have resolved conflicts, how they’ve managed time-sensitive tasks or how they’ve worked in group projects.

Here are some ideas:

- How do you prioritize work when there are multiple projects going on at the same time?

- What happened when you disagreed with a colleague about how you should approach a project or deal with a problem at work?

Check our list of behavioral interview questions for more examples.

3. Use hypothetical scenarios, games and activities that test specific abilities.

Often, it’s useful to simulate job duties to test how candidates would approach regular tasks and challenges. That’s because each job, team and company is different, so you want to find a candidate who fits your unique environment. For example, a role-playing activity can help you assess whether salespeople have the negotiation skills you’re specifically looking for. Or, you can use a game-based exercise to identify candidates who solve problems creatively.

Here are some examples:

- If you had two important deadlines coming up, how would you prioritize your tasks?

- If one of your team members was underperforming, how would you give them feedback?

For more ideas on using hypothetical scenarios to evaluate candidates, take a look at our situational interview questions .

4. Pay attention to candidates’ answers and reactions during interviews

You can learn a lot about candidates’ soft skills through job-specific questions and assignments. Even if you want to primarily test candidates’ knowledge and hard skills, you can still notice strong and weak points in soft skills, too. For example, one candidate might claim to have excellent attention to detail, but if their written assignment has many typos and errors, then that’s a red flag. Likewise, when a candidate gives you clear, well-structured answers, it’s a hint they’re good communicators.

To form an objective opinion on candidates’ soft skills and abilities, make sure you take everything into consideration: from the way they interact with you during interviews to their performance on job-related tasks. This way, you’ll be more confident you select the most competent employees, but also those who fit well to your work environment.

Want more definitions? See our complete library of HR Terms .

Frequently asked questions

Get our hris buyer’s guide.

What's an HRIS? What do I need to know in order to get one? How can it help my business? If you've asked yourself these questions, our new HRIS Buyer's Guide is for you.

Let's grow together

Explore our full platform with a 15-day free trial. Post jobs, get candidates and onboard employees all in one place.

6 Fun Morning Work and Bell Ringer Ideas

The first five minutes of class can set the tone for an entire lesson. So what can you do to capture your students’ attention and get them ready to learn right away? This is where fun morning work and bell ringer activities come in handy.

These start-of-class activities go by many different names — morning bell work, do nows, and warm ups, to name a few. No matter what you call them, they all serve a similar purpose: to get your students’ minds moving the moment they walk through your door.

If you need a little morning and bell work inspiration, check out these ideas and resources from fellow educators like you.

Morning Work and Bell Work Activities for Elementary, Middle School, and High School

1. creative and critical thinking questions.

Jump start your students’ creativity and critical thinking with bell ringer questions and prompts that get them thinking outside the box. For example, have students reflect on a provocative quote, ask them to brainstorm solutions to a problem, or prompt them to invent a new technology. By kick starting class with higher-order thinking, your students will be ready to take on any learning challenge.

Creativity Jump Starts: STEM Bell Ringers for Out of the Box Thinking!

By Playful Stem

Morning Work Journal or Bell Ringers

By Teaching With a Mountain View

2. Social emotional learning prompts and journals

Teaching social-emotional learning (SEL) is critical to student success, but it can be difficult to find time for it during the busy school day. So why not take advantage of those first few moments of class to support it? Help students prepare their minds and bodies for learning by assigning a daily check-in or SEL activity as morning work or bell ringers.

Daily Social Emotional Learning Warm Up Journal

By Allie Szczecinski with Miss Behavior

Growth Mindset Bell Ringers | 40 SEL Writing Prompts For Any Subject | Volume 2

By Mister Harms

Not Grade Specific

3. Morning tubs and hands-on activities

Who says morning work has to be pencil and paper? Try something hands on, such as morning tubs, to get students engaged in learning right away. Morning tubs are bins that are pre-filled with an activity and various hands-on materials, such as manipulatives, puzzles, spinners, dice, or dominoes. For younger students, they can be a great opportunity to develop those fine motor skills.

INSTANT VOCABULARY Tubs N Trays MORNING WORK, CENTERS, FINE MOTOR

By Tara West – Little Minds at Work

Grades PreK-K

4th Grade Morning Tubs Work Bin Hands-on Activities Fall, Winter, Spring, Summer

By Cynthia Vautrot – My Kind of Teaching

4. Brain teasers and logic puzzles

Encourage your students to put on their thinking caps during morning work or bell work with brain teasers and logic puzzles! Share a riddle, rebus puzzle, or logic game as a fun way for students to put their minds to work. You could even add a collaborative element by having your students think through the puzzles in partners or groups.

Brain Teaser Bell Ringers | Digital Math Morning Work | Logic Puzzles

By Acres of Learning

BRAIN TEASERS VOL. 2 – Logic, Word Sense, Puzzles, Lateral Thinking – Fun Stuff

By Laura Randazzo

Grades 8-11

5. Article of the day or week

Assigning an article of the day or week is a fantastic way to incorporate reading comprehension and relevant content into your morning work or bell ringers. No matter what you teach — social studies, math, music, science — you can bring in thought-provoking articles and passages that build students’ curiosity and comprehension skills.

Article of the Week Nonfiction Reading Comprehension Passages Weekly 4th 5th 6th

By Lindsay Flood

Strange Geography Article of the Day-Bellringers-Reading Comprehension Passages

By Think Tank

6. Concept review activities

Last but certainly not least, those first minutes of class are an excellent opportunity to review key concepts and skills with students. Whether you’re reviewing the prior day’s learning or circling back to a previously taught skill, devoting a little time to review every day can help those important concepts sink in. You might even consider differentiating your morning work or bell ringers based on the needs of your individual students.

1st Grade Daily Math Warm Up and Morning Work – 120 Chart Review

By Mr Elementary Math

Science Daily Warmups FULL YEAR | Bell ringers | 4th grade & 5th grade

By The Science Penguin

Daily Grammar Practice with Editable Spiraled ELA | Morning Work

By Tanya G Marshall The Butterfly Teacher

MUSIC VOCAB 10 Minute Terms | Music Bellringers | Secondary Music Vocabulary

By Sarah Stockton Resources

Grades 6-12

BACK TO SCHOOL FULL YEAR ALGEBRA 1 WARM UPS Bundle | Bell Ringers | Exit Tickets

By Algebra Accents

Grades 7-10

With these morning and bell work ideas and activities in hand, you’re sure to start your lessons off strong. If you need more inspiration, be sure to check out other morning work and bell ringer resources on TPT.

- Middle School

- High School

- Social Studies

- Social-Emotional Learning

- Back-to-School

- Asian Pacific American Heritage Month

- Autism Acceptance Month

- Black History Month

- Hispanic Heritage Month

- Pride Month

- Indigenous Peoples’ Month

- Women’s History Month

What is STEM Education?

STEM education, now also know as STEAM, is a multi-discipline approach to teaching.

- Importance of STEAM education

STEAM blended learning

- Inequalities in STEAM

Additional resources

Bibliography.

STEM education is a teaching approach that combines science, technology, engineering and math . Its recent successor, STEAM, also incorporates the arts, which have the "ability to expand the limits of STEM education and application," according to Stem Education Guide . STEAM is designed to encourage discussions and problem-solving among students, developing both practical skills and appreciation for collaborations, according to the Institution for Art Integration and STEAM .

Rather than teach the five disciplines as separate and discrete subjects, STEAM integrates them into a cohesive learning paradigm based on real-world applications.

According to the U.S. Department of Education "In an ever-changing, increasingly complex world, it's more important than ever that our nation's youth are prepared to bring knowledge and skills to solve problems, make sense of information, and know how to gather and evaluate evidence to make decisions."

In 2009, the Obama administration announced the " Educate to Innovate " campaign to motivate and inspire students to excel in STEAM subjects. This campaign also addresses the inadequate number of teachers skilled to educate in these subjects.

The Department of Education now offers a number of STEM-based programs , including research programs with a STEAM emphasis, STEAM grant selection programs and general programs that support STEAM education.

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Education awarded $141 million in new grants and $437 million to continue existing STEAM projects a breakdown of grants can be seen in their investment report .

The importance of STEM and STEAM education

STEAM education is crucial to meet the needs of a changing world. According to an article from iD Tech , millions of STEAM jobs remain unfilled in the U.S., therefore efforts to fill this skill gap are of great importance. According to a report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics there is a projected growth of STEAM-related occupations of 10.5% between 2020 and 2030 compared to 7.5% in non-STEAM-related occupations. The median wage in 2020 was also higher in STEAM occupations ($89,780) compared to non-STEAM occupations ($40,020).

Between 2014 and 2024, employment in computer occupations is projected to increase by 12.5 percent between 2014 and 2024, according to a STEAM occupation report . With projected increases in STEAM-related occupations, there needs to be an equal increase in STEAM education efforts to encourage students into these fields otherwise the skill gap will continue to grow.

STEAM jobs do not all require higher education or even a college degree. Less than half of entry-level STEAM jobs require a bachelor's degree or higher, according to skills gap website Burning Glass Technologies . However, a four-year degree is incredibly helpful with salary — the average advertised starting salary for entry-level STEAM jobs with a bachelor's requirement was 26 percent higher than jobs in the non-STEAM fields.. For every job posting for a bachelor's degree recipient in a non-STEAM field, there were 2.5 entry-level job postings for a bachelor's degree recipient in a STEAM field.

What separates STEAM from traditional science and math education is the blended learning environment and showing students how the scientific method can be applied to everyday life. It teaches students computational thinking and focuses on the real-world applications of problem-solving. As mentioned before, STEAM education begins while students are very young:

Elementary school — STEAM education focuses on the introductory level STEAM courses, as well as awareness of the STEAM fields and occupations. This initial step provides standards-based structured inquiry-based and real-world problem-based learning, connecting all four of the STEAM subjects. The goal is to pique students' interest into them wanting to pursue the courses, not because they have to. There is also an emphasis placed on bridging in-school and out-of-school STEAM learning opportunities.

– Best microscopes for kids

– What is a scientific theory?

– Science experiments for kids

Middle school — At this stage, the courses become more rigorous and challenging. Student awareness of STEAM fields and occupations is still pursued, as well as the academic requirements of such fields. Student exploration of STEAM-related careers begins at this level, particularly for underrepresented populations.

High school — The program of study focuses on the application of the subjects in a challenging and rigorous manner. Courses and pathways are now available in STEAM fields and occupations, as well as preparation for post-secondary education and employment. More emphasis is placed on bridging in-school and out-of-school STEAM opportunities.

Much of the STEAM curriculum is aimed toward attracting underrepresented populations. There is a significant disparity in the female to male ratio when it comes to those employed in STEAM fields, according to Stem Women . Approximately 1 in 4 STEAM graduates is female.

Inequalities in STEAM education

Ethnically, people from Black backgrounds in STEAM education in the UK have poorer degree outcomes and lower rates of academic career progression compared to other ethnic groups, according to a report from The Royal Society . Although the proportion of Black students in STEAM higher education has increased over the last decade, they are leaving STEAM careers at a higher rate compared to other ethnic groups.

"These reports highlight the challenges faced by Black researchers, but we also need to tackle the wider inequalities which exist across our society and prevent talented people from pursuing careers in science." President of the Royal Society, Sir Adrian Smith said.

Asian students typically have the highest level of interest in STEAM. According to the Royal Society report in 2018/19 18.7% of academic staff in STEAM were from ethnic minority groups, of these groups 13.2% were Asian compared to 1.7% who were Black.

If you want to learn more about why STEAM is so important check out this informative article from the University of San Diego . Explore some handy STEAM education teaching resources courtesy of the Resilient Educator . Looking for tips to help get children into STEAM? Forbes has got you covered.

- Lee, Meggan J., et al. ' If you aren't White, Asian or Indian, you aren't an engineer': racial microaggressions in STEM education. " International Journal of STEM Education 7.1 (2020): 1-16.

- STEM Occupations: Past, Present, And Future . Stella Fayer, Alan Lacey, and Audrey Watson. A report. 2017.

- Institution for Art Integration and STEAM What is STEAM education?

- Barone, Ryan, ' The state of STEM education told through 18 stats ', iD Tech.

- U.S. Department of Education , Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math, including Computer Science.

- ' STEM sector must step up and end unacceptable disparities in Black staff ', The Royal Society. A report, March 25, 2021.

- 'Percentages of Women in STEM Statistics' Stemwomen.com

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What's the difference between a rock and a mineral?

'Physics itself disappears': How theoretical physicist Thomas Hertog helped Stephen Hawking produce his final, most radical theory of everything

Hundreds of centuries-old coins unearthed in Germany likely belonged to wealthy 17th-century mayor

Most Popular

- 2 Rare fungal STI spotted in US for the 1st time

- 3 James Webb telescope finds carbon at the dawn of the universe, challenging our understanding of when life could have emerged

- 4 Neanderthals and humans interbred 47,000 years ago for nearly 7,000 years, research suggests

- 5 Noise-canceling headphones can use AI to 'lock on' to somebody when they speak and drown out all other noises

- 2 Bornean clouded leopard family filmed in wild for 1st time ever

- 3 What is the 3-body problem, and is it really unsolvable?

- 4 7 potential 'alien megastructures' spotted in our galaxy are not what they seem