Resilience Tested: Toyota Crisis Management Case Study

Crisis management is organization’s ability to navigate through challenging times.

The renowned Japanese automaker Toyota faced such challenge which shook the automotive industry and put a dent in the previously pristine reputation of the brand.

The Toyota crisis, characterized by sudden acceleration issues in some of its vehicles, serves as a compelling case study for examining the importance of effective crisis management.

Toyota crisis management case study gives background of the crisis, analyze Toyota’s initial response, explore their crisis management strategy, evaluate its effectiveness, and draw valuable lessons from this pivotal event.

By understanding how Toyota tackled this crisis, we can glean insights that will help organizations better prepare for and respond to similar challenges in the future.

Let’s start reading

Brief history of Toyota as a company

Toyota, one of the world’s largest automobile manufacturers, has a rich history that spans over eight decades. The company was founded by Kiichiro Toyoda in 1937 as a spinoff of his father’s textile machinery business.

Initially, Toyota focused on producing automatic looms, but Kiichiro had a vision to expand into the automotive industry. Inspired by a trip to the United States and Europe, he saw the potential for automobiles to transform society and decided to steer the company in that direction.

In 1936, Toyota built its first prototype car, the A1, and in 1937, they officially established the Toyota Motor Corporation. The company faced numerous challenges in its early years, including the disruption caused by World War II, which halted production.

However, Toyota persisted and resumed operations after the war, embarking on a journey that would eventually lead to global recognition.

Toyota’s breakthrough came in the 1960s with the introduction of the compact and affordable Toyota Corolla, which quickly gained popularity worldwide. This success laid the foundation for Toyota’s reputation for producing reliable, fuel-efficient, and high-quality vehicles.

Throughout the following decades, Toyota expanded its product lineup, launching models like the Camry, Prius (the world’s first mass-produced hybrid car), and the Land Cruiser, among others.

Toyota’s commitment to continuous improvement and efficiency led to the development and implementation of the Toyota Production System (TPS), often referred to as “lean manufacturing.” TPS revolutionized the automotive industry by minimizing waste, improving productivity, and enhancing quality.

Over the years, Toyota successfully implemented many change initiatives.

By the turn of the 21st century, Toyota had firmly established itself as a global automotive powerhouse, consistently ranking among the top automakers in terms of sales volume.

However, the company would soon face a significant challenge in the form of the sudden acceleration crisis, which tested Toyota’s crisis management capabilities and had far-reaching implications for the brand.

Description of the sudden acceleration crisis

The sudden acceleration crisis was a pivotal event in Toyota’s history, which unfolded in the late 2000s and early 2010s. It involved a series of incidents where Toyota vehicles experienced unintended acceleration, leading to accidents, injuries, and even fatalities. Reports emerged of vehicles accelerating uncontrollably, despite drivers attempting to apply the brakes or shift into neutral.

The crisis gained significant media attention and scrutiny , as it posed serious safety concerns for Toyota customers and raised questions about the company’s manufacturing processes and quality control. The issue affected a wide range of Toyota models, including popular ones such as the Camry, Corolla, and Prius.

Investigations revealed that the unintended acceleration was attributed to various factors. One prominent cause was a design flaw in the accelerator pedal assembly, where the pedals could become trapped or stuck in a partially depressed position. Additionally, electronic throttle control systems were also identified as potential contributors to the issue.

The sudden acceleration crisis had severe consequences for Toyota. It tarnished the company’s reputation for reliability and safety, and public trust in the brand was significantly eroded. Toyota faced a wave of lawsuits, regulatory investigations, and recalls, as it scrambled to address the issue and restore consumer confidence.

The crisis prompted Toyota to launch one of the largest recalls in automotive history, affecting millions of vehicles worldwide. The company took steps to redesign and replace the faulty accelerator pedals and improve the electronic throttle control systems to prevent future incidents. Toyota also faced criticism for its initial response, with accusations of a lack of transparency and timely communication with the public.

The sudden acceleration crisis served as a wake-up call for Toyota, highlighting the importance of effective crisis management and the need for proactive measures to address safety concerns promptly.

Toyota crisis management case study helps us to understand how company’s respond to this crisis and set a precedent for handling future challenges in the years to come.

Timeline of events leading up to the crisis

To understand the timeline of events leading up to the sudden acceleration crisis at Toyota, let’s explore the key milestones:

- Early 2000s: Reports of unintended acceleration incidents begin to surface, with some drivers claiming their Toyota vehicles experienced sudden and uncontrolled acceleration. These incidents, although relatively isolated, raised concerns among consumers.

- August 2009: A tragic incident occurs in California when a Lexus ES 350, a Toyota brand, accelerates uncontrollably, resulting in a high-speed crash that claims the lives of four people. The incident receives significant media attention, highlighting the potential dangers of unintended acceleration.

- September 2009: The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) launches an investigation into the sudden acceleration issue in Toyota vehicles. The probe focuses on floor mat entrapment as a possible cause.

- November 2009: Toyota announces a voluntary recall of approximately 4.2 million vehicles due to the risk of floor mat entrapment causing unintended acceleration. The recall affects several popular models, including the Camry and Prius.

- January 2010: Toyota expands the recall to an additional 2.3 million vehicles, citing concerns over sticking accelerator pedals. This brings the total number of recalled vehicles to nearly 6 million.

- February 2010: In a highly publicized event, Toyota halts sales of eight of its models affected by the accelerator pedal recall, causing a significant disruption to its production and sales.

- February 2010: The U.S. government launches a formal investigation into the safety issues related to unintended acceleration in Toyota vehicles. Congressional hearings are held, during which Toyota executives are questioned about the company’s handling of the crisis.

- April 2010: Toyota faces a $16.4 million fine from the NHTSA for failing to promptly notify the agency about the accelerator pedal defect, violating federal safety regulations.

- Late 2010 and 2011: Toyota faces a wave of lawsuits from affected customers seeking compensation for injuries, deaths, and vehicle damages caused by unintended acceleration incidents.

- 2012 onwards: Toyota continues to address the sudden acceleration crisis by implementing various measures, including improving quality control processes, enhancing communication with regulators and customers, and establishing an independent quality advisory panel.

Toyota’s initial denial and dismissal of the problem

During the early stages of the sudden acceleration crisis, one notable aspect was Toyota’s initial response, which involved a degree of denial and dismissal of the problem. This response contributed to the escalation of the crisis and further eroded public trust in the company. Let’s delve into Toyota’s initial reaction to the issue:

- Downplaying the Problem: In the initial stages, Toyota downplayed the reports of unintended acceleration incidents, attributing them to driver error or mechanical issues. The company maintained that their vehicles were safe and reliable, asserting that the incidents were isolated and not indicative of a systemic problem.

- Lack of Transparency: Toyota faced criticism for its perceived lack of transparency regarding the issue. The company was accused of withholding information and failing to disclose potential safety risks to the public and regulatory agencies promptly. This lack of transparency fueled suspicions and raised questions about the company’s commitment to addressing the problem.

- Slow Response: Toyota’s response to the growing concerns regarding unintended acceleration was relatively slow, leading to accusations of negligence. Critics argued that the company should have acted more swiftly and decisively to investigate and address the issue before it escalated into a full-blown crisis.

- Reluctance to Acknowledge Defects: Initially, Toyota resisted the notion that there were inherent defects in their vehicles that could lead to unintended acceleration. The company’s reluctance to accept responsibility and acknowledge the problem further strained its relationship with consumers, regulators, and the media.

- Impact on Customer Trust: Toyota’s initial denial and dismissal of the problem had a significant impact on customer trust. As more incidents were reported and investigations progressed, customers began to question the integrity of the brand and its commitment to safety. This led to a decline in sales and a tarnishing of Toyota’s once-sterling reputation for reliability.

Lack of transparency and communication with the public

One critical aspect of Toyota’s initial response to the sudden acceleration crisis was the perceived lack of transparency and ineffective communication with the public. This deficiency in open and timely communication further intensified the crisis and eroded trust in the company. Let’s explore the key issues related to transparency and communication:

- Delayed Public Announcement: Toyota faced criticism for the delay in publicly acknowledging the safety concerns surrounding unintended acceleration. As reports of incidents surfaced and investigations commenced, there was a perception that Toyota withheld information and failed to promptly address the issue. This lack of transparency fueled public skepticism and eroded confidence in the company.

- Insufficient Explanation: When Toyota did address the sudden acceleration issue, their explanations and communications were often vague and lacking in detail. Customers and the public were left with unanswered questions and a sense that the company was not providing comprehensive information about the problem and its resolution.

- Ineffective Recall Communication: Toyota’s communication regarding the recalls linked to unintended acceleration was criticized for its inadequacy. Some customers reported confusion and frustration with the recall process, including unclear instructions and delays in obtaining necessary repairs. This lack of clarity and efficiency in communicating recall information further strained the company’s relationship with its customers.

- Limited Engagement with Stakeholders: Toyota’s engagement with key stakeholders, such as regulatory bodies, industry experts, and affected customers, was perceived as insufficient. The company’s communication efforts were criticized for being reactive rather than proactive, lacking a comprehensive plan to engage stakeholders and address their concerns promptly.

- Perception of Cover-up: The lack of transparency and ineffective communication led to a perception that Toyota was attempting to cover up the severity of the sudden acceleration issue. This perception further damaged the company’s credibility and fueled public skepticism about the company’s commitment to consumer safety.

Impact on the company’s reputation and customer trust

The sudden acceleration crisis had a profound impact on Toyota’s reputation and customer trust, which were previously regarded as key strengths of the company. Let’s explore the repercussions of the crisis on these crucial aspects:

- Reputation Damage: Toyota’s reputation as a manufacturer of reliable and safe vehicles took a significant hit due to the sudden acceleration crisis. The widespread media coverage of incidents and recalls associated with unintended acceleration eroded the perception of Toyota’s quality and reliability. The crisis challenged the long-standing perception of Toyota as a leader in automotive excellence.

- Loss of Customer Trust: The crisis shattered the trust that customers had placed in Toyota. The incidents of unintended acceleration and the subsequent recalls created doubts about the safety of Toyota vehicles. Customers who had been loyal to the brand for years felt betrayed and concerned about the potential risks associated with owning or purchasing a Toyota vehicle.

- Sales Decline: The erosion of customer trust and the negative publicity surrounding the sudden acceleration crisis resulted in a significant decline in sales for Toyota. Consumers were hesitant to buy Toyota vehicles, leading to a loss of market share. Competitors seized the opportunity to capitalize on Toyota’s weakened position and gain a foothold in the market.

- Legal Consequences: Toyota faced a wave of lawsuits from individuals and families affected by incidents related to unintended acceleration. These lawsuits not only had financial implications but also further damaged the company’s reputation as it faced allegations of negligence and failure to ensure the safety of its vehicles.

- Regulatory Scrutiny: The sudden acceleration crisis brought increased regulatory scrutiny upon Toyota. Government agencies, such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), conducted investigations into the issue, which further dented the company’s reputation. Toyota had to cooperate with regulatory bodies and demonstrate its commitment to rectifying the problems to restore trust.

- Long-Term Brand Perception: The sudden acceleration crisis left a lasting impression on how Toyota is perceived by consumers. Despite the company’s efforts to address the issue and improve safety measures, the crisis served as a reminder that even renowned brands can face significant challenges. It highlighted the importance of transparency, accountability, and a proactive approach to crisis management.

Recognition and acceptance of the crisis

In the face of mounting evidence and public scrutiny, Toyota eventually recognized and accepted the severity of the sudden acceleration crisis. The company’s acknowledgment of the crisis marked a significant turning point in their approach to addressing the issue. Let’s explore how Toyota recognized and accepted the crisis:

- Admitting the Problem: As the number of reported incidents increased and investigations progressed, Toyota eventually acknowledged that there was a problem with unintended acceleration in some of their vehicles. This admission was a crucial step towards recognizing the crisis and accepting the need for immediate action.

- Apology and Responsibility: Toyota’s top executives, including the company’s President at the time, issued public apologies for the safety issues and the negative impact on customers. The company took responsibility for the unintended acceleration problem, acknowledging that there were defects in their vehicles and accepting accountability for the consequences.

- Collaboration with Authorities: Toyota actively collaborated with regulatory bodies, such as the NHTSA, and other government agencies involved in investigating the sudden acceleration issue. This collaboration demonstrated a commitment to resolving the crisis and addressing the concerns of the authorities.

- Openness to Independent Investigation: In an effort to ensure transparency and unbiased assessment of the crisis, Toyota welcomed independent investigations into the unintended acceleration incidents. The company engaged external experts and formed advisory panels to evaluate their manufacturing processes, safety systems, and quality control measures.

- Recall and Repair Initiatives: Toyota initiated a massive recall campaign to address the safety issues associated with unintended acceleration. The company implemented comprehensive repair programs aimed at fixing the defects and improving the safety features in affected vehicles. These initiatives were crucial in demonstrating Toyota’s commitment to rectifying the problems and ensuring customer safety.

- Internal Process Evaluation : Toyota conducted internal evaluations and reviews of their manufacturing processes and quality control systems. They identified areas for improvement and implemented changes to prevent similar issues from arising in the future. This internal introspection showed a dedication to learning from the crisis and strengthening their processes.

Appointment of crisis management team

In response to the sudden acceleration crisis, Toyota recognized the need for a dedicated crisis management team to effectively handle the situation. The appointment of such a team was crucial in coordinating the company’s response, managing communications, and implementing appropriate strategies to address the crisis.

Toyota appointed experienced and senior executives to lead the crisis management team. These individuals had a deep understanding of the company’s operations, values, and stakeholder relationships. They were entrusted with making critical decisions and guiding the organization through the crisis.

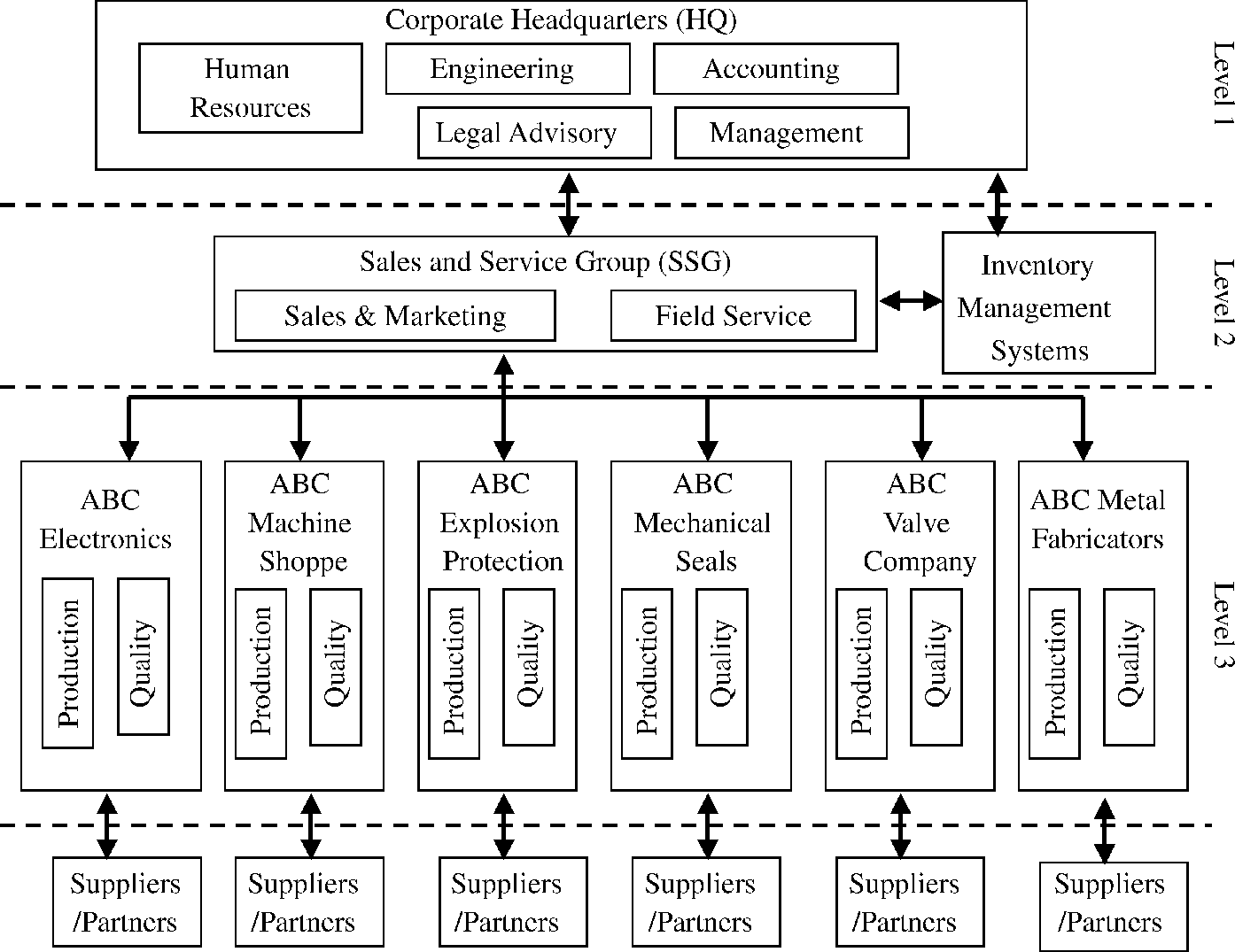

The crisis management team comprised representatives from various functions and departments within Toyota, ensuring a comprehensive approach to addressing the crisis. Members included executives from engineering, manufacturing, quality control, legal, public relations, and other relevant areas. This cross-functional representation facilitated a holistic understanding of the issues and enabled effective collaboration.

Implementation of recall and repair programs

In response to the sudden acceleration crisis, Toyota implemented extensive recall and repair programs to address the safety concerns associated with unintended acceleration. These programs aimed to rectify the defects, enhance the safety features, and restore customer confidence.

Toyota identified the models and production years that were potentially affected by unintended acceleration issues. This involved a thorough examination of reported incidents, investigations, and collaboration with regulatory agencies. By pinpointing the specific vehicles at risk, Toyota could direct their efforts towards addressing the problem efficiently.

Toyota launched a comprehensive communication campaign to reach out to affected customers. The company sent notifications via mail, email, and other channels to inform them about the recall and repair programs. The communication highlighted the potential risks, steps to take, and the importance of addressing the issue promptly.

Toyota actively engaged its dealership network to support the recall and repair initiatives. Dealerships were provided with detailed information, training, and necessary resources to assist customers in scheduling appointments, conducting inspections, and performing the required repairs. This collaboration between the company and its dealerships aimed to ensure a seamless and efficient recall process.

Toyota developed a structured repair process to address the unintended acceleration issue in the affected vehicles. This involved inspecting and, if necessary, replacing or modifying components such as the accelerator pedals, floor mats, or electronic control systems. The company ensured an adequate supply of replacement parts to minimize delays and facilitate timely repairs.

Collaboration with regulatory bodies and industry experts

During the sudden acceleration crisis, Toyota recognized the importance of collaborating with regulatory bodies and industry experts to address the safety concerns and restore confidence in their vehicles. This collaboration involved working closely with relevant agencies and seeking external expertise to investigate the issue and implement necessary improvements.

Let’s delve into Toyota’s collaboration with regulatory bodies and industry experts:

- Regulatory Engagement: Toyota actively engaged with regulatory bodies, such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) in the United States and other similar agencies globally. The company cooperated with these organizations by providing them with relevant data, participating in investigations, and adhering to their guidelines and recommendations. This collaboration aimed to ensure a thorough and unbiased assessment of the sudden acceleration issue.

- Joint Investigations: Toyota collaborated with regulatory bodies in conducting joint investigations into the unintended acceleration incidents. These investigations involved sharing data, conducting extensive testing, and evaluating potential causes and contributing factors. By working together with the regulatory authorities, Toyota aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the problem and find effective solutions.

- Advisory Panels and External Experts: Toyota sought the expertise of external industry experts and formed advisory panels to provide independent assessments of the sudden acceleration issue. These panels consisted of experienced engineers, scientists, and safety specialists who analyzed the data, evaluated the vehicle systems, and offered recommendations for improvement. Their insights and recommendations helped guide Toyota’s response and ensure a thorough and impartial evaluation.

- Safety Standards Compliance: Toyota collaborated with regulatory bodies to ensure compliance with safety standards and regulations. The company actively participated in discussions and consultations to contribute to the development of robust safety standards for the automotive industry. By actively engaging with regulatory bodies, Toyota aimed to demonstrate its commitment to maintaining high safety standards and fostering an environment of continuous improvement.

- Sharing Best Practices: Toyota collaborated with industry peers and participated in industry forums and conferences to share best practices and learn from others’ experiences. By engaging with other automotive manufacturers, Toyota aimed to gain insights into safety practices, quality control measures, and crisis management strategies. This exchange of knowledge and collaboration helped Toyota strengthen their approach to safety and crisis management.

Final Words

Toyota crisis management case study serves as a valuable reminder to all automobiles companies on managing crisis. The sudden acceleration crisis presented a significant challenge for Toyota, testing the company’s crisis management capabilities and resilience. While Toyota demonstrated strengths in their crisis management strategy, such as a swift response, transparent communication, and a customer-focused approach, they also faced weaknesses and shortcomings. Initial denial, lack of transparency, and communication issues hampered their crisis response.

The crisis had profound financial consequences for Toyota, including costs associated with recalls, repairs, legal settlements, fines, and a decline in market value. Legal settlements were reached to address claims from affected customers, shareholders, and other stakeholders seeking compensation for damages and losses. The crisis also resulted in reputation damage that required significant efforts to rebuild trust and restore the company’s standing.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

10 Top Change Management Skills with Examples

Portfolio Change Management – Principles and Best Practices

Different Types of Change Management- Examples, Advantages and Disadvantages

Case Study: Crisis Response Strategies of Toyota

- First Online: 01 January 2014

Cite this chapter

- Olga Bloch 2

1533 Accesses

As outlined in the objectives of this research, Toyota Motor Corporation was selected for the analysis of its communication in crisis. The reasons for this choice were the following. First, the company has recently experienced a crisis due to several major recalls of its vehicles. While working on this dissertation, therefore, enough data could be obtained from the media and the internet. At the same time, the case of Toyota was relatively new and not much was written so far on the subject of interpretation of crisis at Toyota.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

International Advisory Services, Frankfurt School of Finance & Management gemeinnützige GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Olga Bloch .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden

About this chapter

Bloch, O. (2014). Case Study: Crisis Response Strategies of Toyota. In: Corporate Identity and Crisis Response Strategies. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06222-4_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06222-4_4

Published : 26 May 2014

Publisher Name : Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-06221-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-06222-4

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

(Still) learning from Toyota

In the two years since I retired as president and CEO of Canadian Autoparts Toyota (CAPTIN), I’ve had the good fortune to work with many global manufacturers in different industries on challenges related to lean management. Through that exposure, I’ve been struck by how much the Toyota production system has already changed the face of operations and management, and by the energy that companies continue to expend in trying to apply it to their own operations.

Yet I’ve also found that even though companies are currently benefiting from lean, they have largely just scratched the surface, given the benefits they could achieve. What’s more, the goal line itself is moving—and will go on moving—as companies such as Toyota continue to define the cutting edge. Of course, this will come as no surprise for any student of the Toyota production system and should even serve as a challenge. After all, the goal is continuous improvement.

Room to improve

The two pillars of the Toyota way of doing things are kaizen (the philosophy of continuous improvement) and respect and empowerment for people, particularly line workers. Both are absolutely required in order for lean to work. One huge barrier to both goals is complacency. Through my exposure to different manufacturing environments, I’ve been surprised to find that senior managers often feel they’ve been very successful in their efforts to emulate Toyota’s production system—when in fact their progress has been limited.

The reality is that many senior executives—and by extension many organizations—aren’t nearly as self-reflective or objective about evaluating themselves as they should be. A lot of executives have a propensity to talk about the good things they’re doing rather than focus on applying resources to the things that aren’t what they want them to be.

When I recently visited a large manufacturer, for example, I compared notes with a company executive about an evaluation tool it had adapted from Toyota. The tool measures a host of categories (such as safety, quality, cost, and human development) and averages the scores on a scale of zero to five. The executive was describing how his unit scored a five—a perfect score. “Where?” I asked him, surprised. “On what dimension?”

“Overall,” he answered. “Five was the average.”

When he asked me about my experiences at Toyota over the years and the scores its units received, I answered candidly that the best score I’d ever seen was a 3.2—and that was only for a year, before the unit fell back. What happens in Toyota’s culture is that as soon as you start making a lot of progress toward a goal, the goal is changed and the carrot is moved. It’s a deep part of the culture to create new challenges constantly and not to rest when you meet old ones. Only through honest self-reflection can senior executives learn to focus on the things that need improvement, learn how to close the gaps, and get to where they need to be as leaders.

A self-reflective culture is also likely to contribute to what I call a “no excuse” organization, and this is valuable in times of crisis. When Toyota faced serious problems related to the unintended acceleration of some vehicles, for example, we took this as an opportunity to revisit everything we did to ensure quality in the design of vehicles—from engineering and production to the manufacture of parts and so on. Companies that can use crises to their advantage will always excel against self-satisfied organizations that already feel they’re the best at what they do.

A common characteristic of companies struggling to achieve continuous improvement is that they pick and choose the lean tools they want to use, without necessarily understanding how these tools operate as a system. (Whenever I hear executives say “we did kaizen ,” which in fact is an entire philosophy, I know they don’t get it.) For example, the manufacturer I mentioned earlier had recently put in an andon system, to alert management about problems on the line. 1 1. Many executives will have heard of the andon cord, a Toyota innovation now common in many automotive and assembly environments: line workers are empowered to address quality or other problems by stopping production. Featuring plasma-screen monitors at every workstation, the system had required a considerable development and programming effort to implement. To my mind, it represented a knee-buckling amount of investment compared with systems I’d seen at Toyota, where a new tool might rely on sticky notes and signature cards until its merits were proved.

An executive was explaining to me how successful the implementation had been and how well the company was doing with lean. I had been visiting the plant for a week or so. My back was to the monitor out on the shop floor, and the executive was looking toward it, facing me, when I surprised him by quoting a series of figures from the display. When he asked how I’d done so, I pointed out that the tool was broken; the numbers weren’t updating and hadn’t since Monday. This was no secret to the system’s operators and to the frontline workers. The executive probably hadn’t been visiting with them enough to know what was happening and why. Quite possibly, the new system receiving such praise was itself a monument to waste.

Room to reflect

At the end of the day, stories like this underscore the fact that applying lean is a leadership challenge, not just an operational one. A company’s senior executives often become successful as leaders through years spent learning how to contribute inside a particular culture. Indeed, Toyota views this as a career-long process and encourages it by offering executives a diversity of assignments, significant amounts of training, and even additional college education to help prepare them as lean leaders. It’s no surprise, therefore, that should a company bring in an initiative like Toyota’s production system—or any lean initiative requiring the culture to change fundamentally—its leaders may well struggle and even view the change as a threat. This is particularly true of lean because, in many cases, rank-and-file workers know far more about the system from a “toolbox standpoint” than do executives, whose job is to understand how the whole system comes together. This fact can be intimidating to some executives.

Senior executives who are considering lean management (or are already well into a lean transformation and looking for ways to get more from the effort and make it stick) should start by recognizing that they will need to be comfortable giving up control. This is a lesson I’ve learned firsthand. I remember going to CAPTIN as president and CEO of the company and wanting to get off to a strong start. Hoping to figure out how to get everyone engaged and following my initiatives, I told my colleagues what I wanted. Yet after six or eight months, I wasn’t getting where I wanted to go quickly enough. Around that time, a Japanese colleague told me, “Deryl, if you say ‘do this’ everybody will do it because you’re president, whether you say ‘go this way,’ or ‘go that way.’ But you need to figure out how to manage these issues having absolutely no power at all.”

So with that advice in mind, I stepped back and got a core group of good people together from all over the company—a person from production control, a night-shift supervisor, a manager, a couple of engineers, and a person in finance—and challenged them to develop a system. I presented them with the direction but asked them to make it work.

And they did. By the end of the three-year period we’d set as a target, for example, we’d dramatically improved our participation rate in problem-solving activities—going from being one of the worst companies in Toyota Motor North America to being one of the best. The beauty of the effort was that the team went about constructing the program in ways I never would have thought of. For example, one team member (the production-control manager) wanted more participation in a survey to determine where we should spend additional time training. So he created a storyboard highlighting the steps of problem solving and put it on the shop floor with questionnaires that he’d developed. To get people to fill them out, his team offered the respondents a hamburger or a hot dog that was barbecued right there on the shop floor. This move was hugely successful.

Another tip whose value I’ve observed over the years is to find a mentor in the company, someone to whom you can speak candidly. When you’re the president or CEO, it can be kind of lonely, and you won’t have anyone to talk with. I was lucky because Toyota has a robust mentorship system, which pairs retired company executives with active ones. But executives anywhere can find a sounding board—someone who speaks the same corporate language you do and has a similar background. It’s worth the effort to find one.

Finally, if you’re going to lead lean, you need knowledge and passion. I’ve been around leaders who had plenty of one or the other, but you really need both. It’s one thing to create all the energy you need to start a lean initiative and way of working, but quite another to keep it going—and that’s the real trick.

Room to run

Even though I’m retired from Toyota, I’m still engaged with the company. My experiences have given me a unique vantage point to see what Toyota is doing to push the boundaries of lean further still.

For example, about four years ago Toyota began applying lean concepts from its factories beyond the factory floor—taking them into finance, financial services, the dealer networks, production control, logistics, and purchasing. This may seem ironic, given the push so many companies outside the auto industry have made in recent years to drive lean thinking into some of these areas. But that’s very consistent with the deliberate way Toyota always strives to perfect something before it’s expanded, looking to “add as you go” rather than “do it once and stop.”

Of course, Toyota still applies lean thinking to its manufacturing operations as well. Take major model changes, which happen about every four to eight years. They require a huge effort—changing all the stamping dies, all the welding points and locations, the painting process, the assembly process, and so on. Over the past six years or so, Toyota has nearly cut in half the time it takes to do a complete model change.

Similarly, Toyota is innovating on the old concept of a “single-minute exchange of dies” 2 2. Quite honestly, the single-minute exchange of dies aspiration is really just that—a goal. The fastest I ever saw anyone do it during my time at New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) was about 10 to 15 minutes. and applying that thinking to new areas, such as high-pressure injection molding for bumpers or the manufacture of alloy wheels. For instance, if you were making an aluminum-alloy wheel five years ago and needed to change from one die to another, that would require about four or five hours because of the nature of the smelting process. Now, Toyota has adjusted the process so that the changeover time is down to less than an hour.

Finally, Toyota is doing some interesting things to go on pushing the quality of its vehicles. It now conducts surveys at ports, for example, so that its workers can do detailed audits of vehicles as they are funneled in from Canada, the United States, and Japan. This allows the company to get more consistency from plant to plant on everything from the torque applied to lug nuts to the gloss levels of multiple reds so that color standards for paint are met consistently.

The changes extend to dealer networks as well. When customers take delivery of a car, the salesperson is accompanied by a technician who goes through it with the new owner, in a panel-by-panel and option-by-option inspection. They’re looking for actionable information: is an interior surface smudged? Is there a fender or hood gap that doesn’t look quite right? All of this checklist data, fed back through Toyota’s engineering, design, and development group, can be sent on to the specific plant that produced the vehicle, so the plant can quickly compare it with other vehicles produced at the same time.

All of these moves to continue perfecting lean are consistent with the basic Toyota approach I described: try and perfect anything before you expand it. Yet at the same time, the philosophy of continuous improvement tells us that there’s ultimately no such thing as perfection. There’s always another goal to reach for and more lessons to learn.

Deryl Sturdevant, a senior adviser to McKinsey, was president and CEO of Canadian Autoparts Toyota (CAPTIN) from 2006 to 2011. Prior to that, he held numerous executive positions at Toyota, as well as at the New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) plant (a joint venture between Toyota and General Motors), in Fremont, California.

Explore a career with us

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Strategic Management - a Dynamic View

Organizational Identity, Corporate Strategy, and Habits of Attention: A Case Study of Toyota

Submitted: 20 April 2018 Reviewed: 24 August 2018 Published: 31 December 2018

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.81117

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Strategic Management - a Dynamic View

Edited by Okechukwu Lawrence Emeagwali

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

2,010 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

This chapter links organizational identity as a cohesive attribute to corporate strategy and a competitive advantage, using Toyota as a case study. The evolution of Toyota from a domestic producer, and exporter, and now a global firm using a novel form of lean production follows innovative tools of human resources, supply chain collaboration, a network identity to link domestic operations to overseas investments, and unparalleled commercial investments in technologies that make the firm moving from a sustainable competitive position to one of unassailable advantage in the global auto sector. The chapter traces the strategic moves to strength Toyota’s identity at all levels, including in its overseas operations, to build a global ecosystem model of collaboration.

- institutional identity

- lean management

- learning symmetries

- habits of attention

Author Information

Charles mcmillan *.

- Schulich School of Business, York University, Toronto, Canada

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

(Article for Lawrence Emeagwali (Ed.), Strategic Management . London, 2018)

October 18, 2018.

“There is no use trying” said Alice, “we cannot believe impossible things.”—Lewis Carroll

1. Introduction

Few organizations combine the institutional benefits of longevity and tradition with the disruptive startup advantages of novelty and suspension of path dependent behavior. This chapter provides a case study of Toyota Corporation, an organization with an explicit philosophy that embodies “…standardized work and kaizen (that) are two sides of the same coin. Standardized work provides a consistent basis for maintaining productivity, quality and safety at high levels. Kaizen furnishes the dynamics of continuing improvement and the very human motivation of encouraging individuals to take part in designing and managing their own jobs” ([ 1 ], p. 38). Toyota’s philosophy, combining a model that is “stable and paranoid, systematic experimental, formal and frank” [ 2 ], often called the Toyota Way, evolved from the founding of Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, founded in 1911, setting up an auto division in 1933, and Toyota Motor Company in 1937 [ 3 ].

What is unique about Toyota and its pioneering lean production, described colloquially as just-in-time (JIT), embraces a deliberative philosophy that establishes a corporate identity for safety, quality, and aspirational performance goals. Going forward, with plants and distribution centers around the world, Toyota cultivates a direct involvement of employees, suppliers, and other organizations, called the Toyota Group, as a network identity that extends boundary members of the firm’s eco-system that also embodies detailed performance measures to strengthen and reinforce identity enhancement. These identity attributes creating novel and seemingly contradictory configurations, both at home and now in global markets. Toyota provides a framework to link identity as a cohesive attribute for problem-solving with explicit, data-driven benchmarks, a DNA that encompasses observation, analysis, hypothesis testing from the shop floor to the executive suite [ 3 , 4 ].

The concept of identity has a long pedigree in the social sciences, dating from classical writers like Adam Smith, Karl Marx, Max Weber, and Emile Durkheim, focusing on individual identities separate and distinct from larger social systems arising from the division of labor. However, identity in organizations is a relatively new construct, based on claims that are “central, distinctive, and enduring” [ 5 ]. Despite the growing literature on organizational identity [ 6 , 7 ], there is less consensus given the multiple disciplinary focus, the levels of analysis, well as minimum empirical work linking organizational identity to corporate strategy. In some cases, identity linkages touch on outcomes like brand equity, reputation, visual media like social networking and the gap between defining what the organization is today and what it wants to become, despite the high failure rate of firms [ 8 ]. Indeed, there is little reason to doubt that “the concept of organizational identity is suffering an identity crisis” ([ 9 ], p. 206).

Despite the growing literature on organization identity, encompassing diverse constructs and methodologies [ 6 , 7 ], often at different organizational levels (individuals, groups and senior management), has limited empirical study linking individual and group identity both to corporate strategy and corporate performance. Various accounts of social experiences, concentrating on a sense of insider and outsider to frame a mutual identity mindset that shapes organizational identity, apply personal histories and narratives, but leave open the distinction between corporate identity and organizational identity [ 10 ]. Identity producing mechanisms flowing from purposeful actions vary by context, such as universities and faith-based organizations to technology and engineering organizations with complicated role activities grounded in socio-technical design [ 11 ]. Compelling cases of identity as a tool for organizational integration, or the impact of cleavage and conflict owing to human diversity policies, personality characteristics of key actors, and sub-unit identity images advance understanding of behavior within organizations, but often ignores how both strategic choice and external forces impact these internal mindsets. Many scholars associate internal identity issues to external stakeholders using sundry communication tools (e.g., [ 12 ]) but the literature has few studies that explain what organizational identity features are truly different and give a competitive advantage in contested markets over time. To advance hypothesis testing and to encourage conceptual development in both theory and practice, there must be a linkage to identity as a construct that provides insights to an organization’s competitive advantage.

This chapter addresses the issues linking strategic choices and capabilities to Toyota’s identity as a case study. Toyota’s strategic positioning and high-performance outcomes amplify identity tools at three levels, its employees (both in Japan and its factories overseas), its suppliers, and its customers. Depicted as a best practice company [ 13 ], Toyota is seen as a model to emulate in sectors as diverse as hospitals and retailing. This chapter has three objectives: first, by examining Toyota’s transformation as a leading domestic producer to a top global company, the firm’s core identity has changed little despite numerous internal and external changes; second, Toyota as a case study illustrates the capacity to have multiple images in different contexts, without sacrificing its core identity; and third, the chapter offers recommendations for empirical studies of organizational identity.

2. Organizational identification and identity

In their seminal article, Stuart and Whetten [ 5 ] put forward the concept of organizational identity constituting a set of “claims” and specified what was central, distinctive and enduring, but recognizing that organizations can have multiple identities and claims that can be contradictory, ambiguous, or even unrelated. While some authors have attempted to provide more clarity, Pratt addresses the construct of identity and its generality, stating it was “often overused and under specified” beyond general statements about “who are we?” and “who do we want to become?”

Historically, identity and identification are described in classical writings focusing on societies, social systems, and their constituent parts. Such examples as Adam Smith in economics on the division of labor, Babbage on the division of work tasks, Marx on division of social class, Max Weber on the division of status and occupation, and Durkheim on differentiated social structures, each contributed to current views of how individuals, groups, and teams become a cohesive collective in a complex organization. More specifically, Durkheim’s [ 14 ] analysis of the division of labor and differentiated social structures with distinct socio-psychological values and impacts required variations in role homogeneity in sub-systems. 1 His views influenced subsequent writers as diverse as Freud in psychiatry and Harold Laswell in political theory, whose study of world politics includes a chapter entitled “Nations and Classes: The Symbols of Identification.”

Simon [ 15 ] introduced identification to organization theory, describing it as follows: “the process of identification permits the broad organizational arrangements to govern the decisions of the persons who participate in the structure” (p. 102). More specifically, “a person identifies himself with a group when, in making a decision, he evaluates the several alternatives of choice in terms of their consequences for the specified group” in contrast to personal motivation, where “his evaluation is based upon an identification with himself or his family” ([ 16 ], p. 206). Both the fault lines of identity, based on status, perverse incentives, class or occupation, as well as group identification [ 17 ] impact organizational performance by variations in shared goals and preferences, as well as forms of interaction and feedback, often enhanced or lessoned by recruitment patterns and work rules and incentives.

Identity and identification as reference points in organizations also flow from the configuration of roles, role structures, and “clusters of activities” where “a person has an occupational self-identity and is motivated to behave in ways which affirm and enhance the value attributes of that identity” ([ 18 ], p. 179). Theories of social identity assume individual identity is partitioned into ingroups and outgroups is social situations and organizational life, often with an implicit cost–benefit calculation, but acts of altruistic behavior, where behavioral norms benefit the welfare of others, often seen in “collectivist societies,” strengthens organizational identity [ 19 ]. Other approaches take a social constructionist approach, emphasizing social and cultural perspectives [ 20 ], where sense-making comes from stories and narratives of everyday experience [ 21 ], thereby, “…in linking identity and narrative in an individual, we link an individual [career] story to a particular cultural and historical narrative of a group” [ 22 ]. Going further, Dutton et al. [ 23 ] speculate that organizational identification is a process of self-categorization cultivated by distinctive, central, and enduring attributes that get reflected in corporate image, reputation, or strategic vision. Alvesson [ 24 ] describes the need for identity alignment: “…by strengthening the organization’s identity—its experienced distinctiveness, consistency, and stability—it can be assumed that individual identities and identification will be strengthen with what they are supposed to be doing at their work place.”

While some studies [ 25 ] purport to focus on managerial strategies that project images as a tool to shape distinctive identities with stakeholders, the reality is that organizational identities without corresponding integration of individual, sub-unit, or group identification may lead to behavioral frictions, and detachment via lower compliance and cues of detachment. Conflict and cleavages affect group-binding identification, often persisting as conformity of opinion, forms of social interaction, and group loyalties, as well as enhancing internal legitimacy for desired outcomes. While both individuals and groups may have multiple and loosely connected identities, there remains lingering organizations dysfunctions that exacerbate cleavage and conflict, such as hypocrisy, selective amnesia, or disloyalty [ 18 ]. Psychological exit comes from unsatisfactory outcomes, a form of weakening organizational identity and strengthening group identity to give voice for remedial actions [ 26 ]. In the extreme, such sub-identities found in groups and sub-units compete with other forms of identification and may lead to organizational dysfunctions [ 17 ].

Akerlof and Kranton [ 27 ] view organizational identity, with emphasis on why firms must transform workers from outsiders to insiders, as a form of motivational capital. In short, a distinctive identity is a distinctive competence. To quote Likert [ 28 ]. “the favorable attitudes towards the organization and the work are not those of easy complacency but are the attitudes of identification with the organization and its objectives and a high sense of involvement in achieving them” (p. 98). Other theorists suggest variations in organizational identity impact sense-making and interpretative processes [ 29 ], internalization of learning [ 10 ] and processes linking shared values and modes of performance [ 30 ].

Identity and identification cues, viewed as the mental perceptions of individual self-awareness, social interactions and experiences, and self-esteem have many antecedents, such as social class [ 31 ], demographic factors like age, race, religion, or sex [ 32 ], and national culture and identity [ 33 ]. Studies emphasizing social construction perspectives stem from individual accounts, often defined in social narratives, histories, and biographies rooted in time and place [ 34 ]. As Hammack [ 22 ] emphasizes, “…in linking identity and narrative in an individual, we link an individual story to a particular cultural and historical narrative of a group” (p. 230). At a general level, organizational culture depicts the set of norms and values that are widely shared and strongly held throughout the organization [ 35 ], and refers to the “unspoken code of communication among members of an organization” [ 36 ] and aids and supplements task coordination and group identity. In this way, individual employees better understand the premises of decision choices in problem solving at the organizational level. In complex organizations, identity is linked to the strategic capacity of choice opportunities and implementation dynamics of priorities and preferences. As Thoenig and Paradieise [ 37 ] emphasize, “strategic capacity lies to a great extent in how much its internal subunits … shape its identity, define its priorities approve its positions, prepare the way for general agreement to be adopted on its roadmap and provide a framework for the decisions and acts of all its components” (p. 299).

Such diverse views leave open how organizational identity, or shared central vision, confers competitive advantage in contested spaces. As a starting hypothesis, a shared identity strengthens coordination across diverse groups applying common norms, codes and protocols, hence improving shared learning skills. In a similar vein, individual cleavages and loyalties are lessoned by shared interactions and information sharing that mobilize learning tools. Further, organizational identity strengthens individual identities via performance success that promotes a shared set of preferences, expectation, and habits of rule setting.

3. Organizational performance at Toyota

By any standards—shareholder value, product innovation, employee satisfaction measured by low turnover and lack of strike action, market capitalization—Toyota has been astonishingly successful, both against rival incumbents in the auto sector, but as a organizational pioneer in transportation with just-in-time thinking. Against existing rivals at home, or in an industry with firms pursuing growth by alliances and acquisition (Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, VW-Porsche), facing receivership and saved by public funding (GM and Chrysler), exiting as a going concern (British Leyland) or new startups (Tesla). Toyota’s performance is unrivaled. Toyota remains a firm committed to organic development, steady and consistent market share in all key international markets, and cultivating a shared identity within its eco-system around measurable outcomes of product safety, quality, and consumer value.

As shown in Figure 1 , despite many forms of competitive advantages, such as size, high domestic market share, being part of a larger group, or diversification, there are many times when the side expected to win actually is less profitable and may actually lose. Toyota’s growth and expansion, despite the turbulent 2009 recall and temporary retreats [ 38 , 39 ], comes with consistent profitability and market share growth. In this organizational transformation, Toyota has replicated its identity of “safety, quality, and value” outside its home market, often depicted by foreigners as “inscrutable,” closed, and Japan Inc. [ 40 ]. Strategically, this organizational identity framework is multipurpose, allowing shared alignment of identities with domestic employees, suppliers and supervisors, but also incorporating these identity attributes first to foreign operations in North America and subsequently to Europe and Asia. Toyota management considers the firm as a learning organization, where learning symmetries take place at all levels, vertically and horizontally.

Operating Profits versus Firm Revenues in the Auto Sector.

Unlike many corporate design models of multinationals, where foreign subsidiaries passively replicate the production systems of the home market (a miniature replica effect) or seek out decision-attention from head-quarters [ 41 ] Toyota is evolving as a global enterprise. In this model, Toyota’s foreign subsidies and trade blocks (e.g., NAFTA and Europe), solve key problems and translate the protocols for headquarters and its global network of factories, distribution outlets, and service and maintenance dealerships. In this way, Toyota’s training protocols, network learning systems, and using foreign subsidies to develop new technologies (e.g., Toyota Canada pioneering cold weather technologies for ignitions engineering), i.e., a learning chain that mobilizes employee identity to network identity, including its global supply chain collaboration [ 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ].

To illustrate the complexity of contemporary auto production and the need to evolve both organizational design around supply chains, and the nature of complementarities in production, firms like Toyota must realign engineering and technological systems to novel role configurations for a diverse workforce. A car (or truck) has over 5000 parts, components, and sub-assemblies, where factories are linked to diverse supply chains with tightly-knit communications and transport linkages, often across national boundaries, to produce a factory production cycle of 1 minute per vehicle, or even less. Parts or components like steel, for instance, are not commodities, undifferentiated only by price, and Japanese steel producers produced the high carbon steel that was more resistant to water, hence rust. This production cycle demands very high quality and safety of each part and component, plus the precision engineering processes to assemble them. This alignment determines not only the standards of quality and safety of the finished vehicle but the image and reputation of the company, plus an indispensable need to retain price value of the brand in the aftermarket sales cycle.

To this contemporary production system, reshaped and refined since Toyota first introduced in 1956 what Womack et al. [ 46 ] termed “the machine that changed the world,” auto production now faces a steady, relentless, and inexorable technology disruption. This shift in engines and fuel consumption technologies, away from diesel and gasoline-powered vehicles, to new dominant technologies, such as electric vehicles, fuel-cells, battery, hydrogen, or hybrid, each requiring massive changes to traditional parts and components suppliers, and the layout of factory assembly. Successful firms thus require forward-looking strategic intent and novel organizational configurations both to exploit existing systems based on gasoline vehicles, or novel organizational systems to explore new technologies and processes. Strategies differ widely. Tesla as a new startup has dedicated factories and labs using lithium battery technology. To gain equivalent scale of Toyota, GM, and Volkswagen, i.e., over 10 million vehicles per year, Nissan and Renault joined with Mitsubishi as a new alliances and equity investment partner.

By contrast, both Ford and GM are retreating from large markets like Europe, Japan, or India with direct-foreign investment strategies. Even more intrusive to existing production programs and protocols are new demands for data analytics, artificial intelligence, robotic and associated Internet and social media technologies. Both incumbent firms, new startups, and suppliers are developing futuristic technologies in drivers’ facial recognition, driving habits, and consumer disabilities, from wheel chairs to hearing that impact cars of the future, and impose threats to existing distinctive competences and corporate identity. Not all firms can manage simultaneously the processes of exploitation of existing organizational programs, and the exploration of product innovation and assembly [ 47 ]. Toyota is an exception.

The Toyota production system is transformational, an organizational philosophy around two core ideas, kaizen or principles of continuous improvement, and nemawashi , or consensus decision-making that allow network effects across its global factories, research labs, its supplier organizations, and related parts of the global eco-system, from universities to global shipping firms. In the firm’s century-old evolution, starting as a leading textile firm that still exists but migrating to auto manufacturing as only the second largest by unit sales (behind Nissan), Toyota has emerged as the top producer both at home and globally, measured by market share, and a leading player in markets like North America, Europe, Latin America, India and China, where many rivals have a low market share presence (e.g., Europe firms in the US, American firms in Europe).

Strategies of corporate retreat in key markets (GM in Europe, GM and Ford in India, Ford in Japan), suggest home market advantages are the new testing ground for first-mover disadvantage [ 48 ] when firms face massive technology disruption. To cite an example, during the 1990s, four major automakers, Toyota, GM, Honda, and Ford, took the lead in the development of hybrid technologies, with GM the leader with 23 patents in hybrid vehicles (vs. 17 for Toyota, 16 for Ford, and 8 for Honda). By 2000, however, Honda and Toyota were the clear leaders, with Honda had filed 170 patents, and Toyota with 166 in hybrid drivetrain technology, far ahead pf Ford with 85 and GM at 56. Today, Fords’ hybrid is a license from Toyota.

4. Toyota identity as a social construct

The auto sector symbolizes the development of post-war multinationals largely based on firm-specific capabilities and proprietary advantages. This organizational evolution includes changing work mechanisms characterized as machine theory by management [ 49 ], a catch-all phrase to describe scientific management techniques espoused by Frederick Taylor from his 1911 book with that title. He first learned time management at Philips Executer Academy and became an early practitioner of what became known as kaizen, continuous improvement, working with Henry Gantt [ 50 ], studying all aspects of work, tools, machine speeds, workflow design, the conversion of raw materials into finished products, and payment systems. The Taylor studies, later dubbed Fordism [ 51 ], was an approach to eliminate waste and unnecessary movements, or “soldiering”—a deliberate restriction of worker output.

Taylor’s disciples in the engineering profession spread his message beyond America, to Europe, as well as to Japan and Russia, where even Lenin and Trotsky developed an interest after the Revolution of 1917. In appearances before Congressional committees, and in other forums, Taylor’s theories faced withering criticisms and great resistance by American union movement a “dehumanizing of the worker” and a tool for profits at the expense of the worker. [ 50 , 52 ]. In Japan, however, Taylorism and scientific management had wide acceptance, starting with Yukinori Hoshino’s translation of Principles of Scientific Management with the title, The Secret of Saving Lost Motion, which sold 2 million copies. Several firms adopted scientific management practices, including standard motions, worker bonuses, and Japanese authors published best sellers on similar notions of work practices, including one entitled Secrets for Eliminating Futile Work and Increasing Production [ 3 ].

After 1945 in Japan, given the wartime devastation of Japan’s industrial capacity, resource scarcity—food, building supplies, raw materials of all sorts, electric power—had a profound and lasting impact on Japanese society, even more so when the American military supervised the Occupation and displayed abundance of everyday goods—big cars, no shortage of food, long leisure hours, and consumer spending using American dollars. As Japanese firms slowly rebuilt, the corporate ethos promoted efficient use of everything, and waste became a watchword for inefficiency. Japanese executives visited US factories, the Japanese media documented US success stories. American management practices were widely emulated, and US consultants—notably Peter Drucker, W. Juran, and W. Edwards Deming—had an immense following and their books, papers and personal appearances were publicized, translated and widely-read, even by high school students. While American firms emphasized a marketing philosophy where the customer is king, Japanese firms remained committed to production, helped in part by trading firms, led by the nine giant Soga Sosha , to distribute and sell both at home and abroad. US human resource practices also showed a stark contrast with Japanese practices. In the US, the rise of the trade union movement and national legislation from Roosevelt’s New Deal, meant that management-worker relations for firms and factories were contractual, setting out legal norms, and negotiated commitments for pay, seniority, promotion, job rotation and skills differentials, so that worker identity was less towards the firm, more to the trade union, and what incentives and compensation union leadership could deliver [ 53 ].

Japan industrial firms, by contrast, cultivated three features of management-worker relations. The first was life time employment—once hired, the employee stayed in the firm until retirement. Second, wages and compensation were determined by seniority—young workers received lower wages and bonus compensation, just as older workers were paid more relative to their actual productivity. And third, firms had enterprise unions, as distinct from industry unions in the US and Europe (e.g., unions autoworkers, coal workers or shipbuilders). All three characteristics greatly extended the psychological linkages between employee identity and the firm’s identity, and the employee’s career success was directly tied to the firm’s success. In Japan, with very low turnover, but high screening processes, firms hired the best graduates, and training was on-going and formed part of the job description, with little layoffs, firing, or absenteeism. Additionally, there was little employee fear of adopting new technologies. Abegglen and Stalk [ 54 ] describe the implication of technological diffusion as follows: “…it is the relatively close identification of the interests of kaisha and their employees that have made this rate of technological change possible and the patterns of union relations implicit in that degree of identification” (p. 133). Indeed, some writers go further, citing how the human resource system was imposed on a Confucian society, with an ethos to govern individual and group interactions for reciprocal benefits, in a market system of winners and losers. As Morishima [ 55 ] puts it, Korea and China chose Confucianism with the market, Japan chose the market with Confucianism, while North America and Europe were characterized by Protestant-driven market behavior of winners and losers. For Toyota, a family enterprise with links to many sectors like steel, textiles, aviation and machinery, the post-war environment brought inevitable contracts with American automotive practices.

Okika [ 56 ] describes the implications of the evolving Japanese model of labor-management relations in the firm:

Japanese enterprises made their decisions by gaining an overall consensus through repeated discussions starting from the bottom and working up … making it easier for workers to accept technical innovation flexibly. For a start, that sense of identity with the firm is strong and they are aware that the firm’s development is to their own advantage, so they tend to improve the efficiency of its production system and strengthens its competitiveness (p. 22).

Across Japan, industrial firms, from Sony to Canon, recruited workers from rural areas, executives read US textbooks, and many visited US factories to study management practices. The production focus of Japanese firms, in a competitive environment of limited slack, hence the need for managerial improvisation and what the French call bricolage , i.e., making do with what is available [ 57 ]. In operational terms, this meant long production runs, division of labor taken to the extreme is monotonous assembly work tasks, product output determined by managerial estimates of demand, and wide use of buffer stocks to absorb varying time cycles of different sub-assembly needs. Buffer stocks also allowed conflicting management department goals to get sorted out with little time constraints, and less need to focus on quality issues based on bad product design, resource waste (e.g., steel), or timing processes that lead to product defects. Organizational reforms widely adopted across US industry, such as product divisions for large enterprises, largely left the product system intact, allowing middle management to focus on coordination between operational benchmarks at the factory level and financial benchmarks imposed by top management [ 58 ]. GM was seen in Japan as the prototype models to emulate.

5. Challenges to orthodox industrial production

The advance of industrialization involved new methods of energy, raw materials, dominant technologies, and organizational configurations [ 58 ] but relatively little to consideration actual production systems, especially after Henry Ford introduced mass production using interchangeable parts. As foreign executives visited Ford’s assembly lines, there were dissenting opinions, such as Czech entrepreneur Thomas Bata and S. Toyoda who worked a year in Detroit. How could three core concepts be integrated—craft skills of custom-made products like a kimono or a house, the volume-cost advantages of mass production, and the nigh utilization capacity of process production in beer or chemicals?

Toyota’s introduction of the lean production system has been widely studied, 2 including its the origins in the 1950s by Ohno [ 62 ], when visiting America and adopting ideas from super market chains, and had strong views on scientific management’s focus on the total production system, and Japanese concepts of jishu kanri (voluntary work groups). Japanese managers had both knowledge and experience with traditional crafts sectors like woodblock prints and silk designs in textiles or the long training needed for Japan’s culinary arts. How could three core concepts be integrated—craft skills of custom-made products like a kimono or a house, the volume-cost advantages of mass production, and the nigh utilization capacity of process production in beer or chemicals?

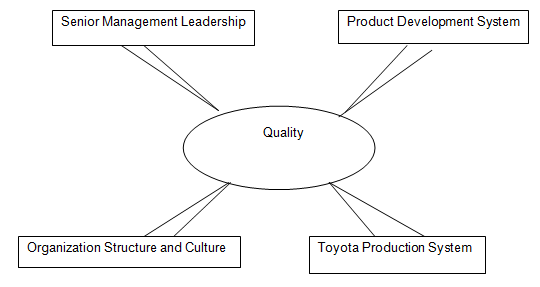

Core concepts of lean production is the desire to maximize capacity utilization, by reducing production variability and minimize excess inventories with a view to eradicating waste [ 54 ]. But other factors are critical, such as supplying high quality workmanship of craft production, reducing per unit costs via mass production using interchangeable parts, and high capacity utilization of continuous flow production, typically seen as three distinct systems. The ingrained ethos of resource scarcity in Japanese society, demonstrating that low slack in organizations encourage search behavior [ 63 ], and these requirements required pooling of efforts as an organizational philosophy ( Figure 2 ).

Contrasts Between Traditional Technical Design and Toyota’s Model.

To perfect the system over time, starting in the 1960s, Toyota accelerated the adoption of high work commitment by organizing workers in teams, reducing the number of job classifications, seeking suggestions from employees, and investing in training of new workers, 47–48 days per worker, compared to less than 5–6 days for US plants, 21–22 days for European plants [ 3 ]. The focus on production as an integrated system, using hardware ideas like quick die change equipment, robots, and advanced computer-aided design, also meant removing traditional tasks that are noisy, hard on the eyes, or dangerous to allow employees to concentrate on tasks like quality assessment, and allowing a worker to stop the entire production line, known as andon, in the case of equipment problems, shortage of parts, and discovery of defects, i.e., transferring certain responsibilities from managers and supervisors to workers [ 60 ]. Paradoxically, Toyota and other Japanese auto plants were far less automated than their foreign-owned rivals, not just for assembly line work but other tasks like welding and painting.

Einstein once said, “Make everything as simple as possible, but no simpler.” Simplicity became a watchword in the evolution of Toyota’s lean production system, a contrast to the complicated vertical integration model adopted in Detroit. Toyota adopted a highly focused structural design, becoming a systems assembler and sourcing from dedicated suppliers, each with core competences in specialized domains and technologies. Production engineering—e.g., craft, mass assembly or process systems—became central features as organizational configuration, choosing from the strengths of each but discarding the perceived weaknesses. Stress was place on the worker, avoiding the monotonous routines of a moving assembly line, by including job rotation and special training to apply quality management circles within a group structure. The advantages of process manufacturing as high capacity utilization came from high initial overhead of equipment and overhead, including IT investments, but allowing flexibility in machine set up, such as quick die change that reduced the need to stop the line for product variability from 3 months, to 3 weeks, to 3 minutes, to less than 3 seconds. The internal factory layout, an S shape configuration, changed the sequencing of tasks, the forms of supervisor-employee interactions, and the speed and timing of interdependencies between the production operations and external suppliers of parts, delivering “just in time.”

In some cases, the interactions involve the core production system and independent suppliers serving as complementarities 3 where the competitive advantage of one is augmented by the presence of the other [ 45 ]. Early examples included Ford’s cooperation with Firestone to produce tires, or Renault’s links to Michelin to produce radial tires. Complementarities allow synergistic advantages, a contrast to additive, discrete features [ 64 ], and allow two immediate effects: knowledge spillovers at differing stages of production, including process learning impacts, and complimentary and coordinated changes in activities and programs across the value chain, such as process benchmarks for product design, scheduling, inspection, and time cycles of production. Toyota cultivates complementarity attributes but instituted a revised activity sequence, discarding production based on estimated demand forecasts, and turning finished production of cars and trucks to car lots for ultimate sale. The pull system starts with customer demands, allowing novel design using the advantages of the need for high capacity utilization of smaller actual output demands, to manufacture outputs with shorter time for product delivery.

6. JIT and Toyota’s deep supplier collaboration systems