Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

Talk to Our counsellor: 9916082261

- Book your demo

- GS Foundation Classroom Program

- Current Affairs Monthly Magazine

- Our Toppers

SOCIOLOGY AND COMMON SENSE (KEY POINTS TO REMEMBER)

- Common Sense is defined as routine knowledge that people have of their everyday world and activities.

- It is generally based on what may be called naturalistic or individualist explanation.

- It is taken for granted knowledge.

- It is unexamined.

- Common Sense help sociologist in hypothesis building.

- it provides raw material for sociological investigations.

- Considerations in Sociology are framed by taking into account the commonsensical knowledge.

- When sociology moved closer to Positivism, common sense was discarded. Anti-positivists gave importance to common sense.

- The fascination of sociology lies in the fact that its perspective makes us see in a new light the very world in which we have lived our lives – Peter Berger.

- Sometimes Sociological knowledge itself becomes a part of common sense knowledge – Anthony Giddens.

- Common sense and Science are together used which to expand man’s understanding of truth – Moore and Reid

- All philosophy gradually develops from the ordinary day-to-day consciousness – Hegel

- Common Sense perceptions are prejudices which can mar the scientific study of social world – Durkheim

- Common Sense is the knowledge that people used to make judgements and navigate their way around the world – Goffman

- Common Sense takes cues from what appears on surface but sociology looks for interconnections and causal explanations.

- Common Sense promotes stereotypical beliefs but sociology uses reason and logic.

- Common sense is based upon assumptions while sociology is based upon evidences.

- Empirical testing has no place in common sense knowledge whereas Sociology pursue research with an empirical orientation.

- Common sense knowledge may not be coherent. Birds of a feather flock together and opposites attract convey opposite meanings.

- Common sense knowledge are personal but sociological knowledge results into generalisations.

- Sociology is change oriented while common sense promotes status quoism.

Request a call back.

Let us help you guide towards your career path We will give you a call between 9 AM to 9 PM

Join us to give your preparation a new direction and ultimately crack the Civil service examination with top rank.

- #1360, 2nd floor,above Philips showroom, Marenhalli, 100ft road, Jayanagar 9th Block, Bangalore

- [email protected]

- +91 9916082261

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

© 2022 Achievers IAS Classes

Click Here To Download Brochure

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.1 Sociology as a Social Science

Learning objectives.

- Explain what is meant by saying that sociology is a social science.

- Describe the difference between a generalization and a law in scientific research.

- List the sources of knowledge on which people rely for their understanding of social reality and explain why the knowledge gained from these sources may sometimes be faulty.

- List the basic steps of the scientific method.

Like anthropology, economics, political science, and psychology, sociology is a social science. All these disciplines use research to try to understand various aspects of human thought and behavior. Although this chapter naturally focuses on sociological research methods, much of the discussion is also relevant for research in the other social and behavioral sciences.

When we say that sociology is a social science, we mean that it uses the scientific method to try to understand the many aspects of society that sociologists study. An important goal is to yield generalizations —general statements regarding trends among various dimensions of social life. We discussed many such generalizations in Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective” : men are more likely than women to commit suicide, young people were more likely to vote for Obama than McCain in 2008, and so forth. A generalization is just that: a statement of a tendency, rather than a hard-and-fast law. For example, the statement that men are more likely than women to commit suicide does not mean that every man commits suicide and no woman commits suicide. It means only that men have a higher suicide rate, even though most men, of course, do not commit suicide. Similarly, the statement that young people were more likely to vote for Obama than for McCain in 2008 does not mean that all young people voted for Obama; it means only that they were more likely than not to do so.

A generalization regarding the 2008 election is that young people were more likely to vote for Barack Obama than for John McCain. This generalization does not mean that every young person voted for Obama and no young person voted for McCain; it means only that they were more likely than not to vote for Obama.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 2.0.

Many people will not fit the pattern of such a generalization, because people are shaped but not totally determined by their social environment. That is both the fascination and the frustration of sociology. Sociology is fascinating because no matter how much sociologists are able to predict people’s behavior, attitudes, and life chances, many people will not fit the predictions. But sociology is frustrating for the same reason. Because people can never be totally explained by their social environment, sociologists can never completely understand the sources of their behavior, attitudes, and life chances.

In this sense, sociology as a social science is very different from a discipline such as physics, in which known laws exist for which no exceptions are possible. For example, we call the law of gravity a law because it describes a physical force that exists on the earth at all times and in all places and that always has the same result. If you were to pick up the book you are now reading—or the computer or other device on which you are reading or listening to—and then let go, the object you were holding would definitely fall to the ground. If you did this a second time, it would fall a second time. If you did this a billion times, it would fall a billion times. In fact, if there were even one time out of a billion that your book or electronic device did not fall down, our understanding of the physical world would be totally revolutionized, the earth could be in danger, and you could go on television and make a lot of money.

People’s attitudes, behavior, and life chances are influenced but not totally determined by many aspects of their social environment.

redjar – Cheering – CC BY-SA 2.0.

For better or worse, people are less predictable than this object that keeps falling down. Sociology can help us understand the social forces that affect our behavior, beliefs, and life chances, but it can only go so far. That limitation conceded, sociological understanding can still go fairly far toward such an understanding, and it can help us comprehend who we are and what we are by helping us first understand the profound yet often subtle influence of our social backgrounds on so many things about us.

Although sociology as a discipline is very different from physics, it is not as different as one might think from this and the other “hard” sciences. Like these disciplines, sociology as a social science relies heavily on systematic research that follows the standard rules of the scientific method. We return to these rules and the nature of sociological research later in this chapter. Suffice it to say here that careful research is essential for a sociological understanding of people, social institutions, and society.

At this point a reader might be saying, “I already know a lot about people. I could have told you that young people voted for Obama. I already had heard that men have a higher suicide rate than women. Maybe our social backgrounds do influence us in ways I had not realized, but what beyond that does sociology have to tell me?”

Students often feel this way because sociology deals with matters already familiar to them. Just about everyone has grown up in a family, so we all know something about it. We read a lot in the media about topics like divorce and health care, so we all already know something about these, too. All this leads some students to wonder if they will learn anything in their introduction to sociology course that they do not already know.

How Do We Know What We Think We Know?

Let’s consider this issue a moment: how do we know what we think we know? Our usual knowledge and understanding of social reality come from at least five sources: (a) personal experience; (b) common sense; (c) the media (including the Internet); (d) “expert authorities,” such as teachers, parents, and government officials; and (e) tradition. These are all important sources of our understanding of how the world “works,” but at the same time their value can often be very limited.

Personal Experience

Let’s look at these sources separately by starting with personal experience. Although personal experiences are very important, not everyone has the same personal experience. This fact casts some doubt on the degree to which our personal experiences can help us understand everything about a topic and the degree to which we can draw conclusions from them that necessarily apply to other people. For example, say you grew up in Maine or Vermont, where more than 98% of the population is white. If you relied on your personal experience to calculate how many people of color live in the country, you would conclude that almost everyone in the United States is also white, which certainly is not true. As another example, say you grew up in a family where your parents had the proverbial perfect marriage, as they loved each other deeply and rarely argued. If you relied on your personal experience to understand the typical American marriage, you would conclude that most marriages were as good as your parents’ marriage, which, unfortunately, also is not true. Many other examples could be cited here, but the basic point should be clear: although personal experience is better than nothing, it often offers only a very limited understanding of social reality other than our own.

Common Sense

If personal experience does not help that much when it comes to making predictions, what about common sense? Although common sense can be very helpful, it can also contradict itself. For example, which makes more sense, haste makes waste or he or she who hesitates is lost ? How about birds of a feather flock together versus opposites attract ? Or two heads are better than one versus too many cooks spoil the broth ? Each of these common sayings makes sense, but if sayings that are opposite of each other both make sense, where does the truth lie? Can common sense always be counted on to help us understand social life? Slightly more than five centuries ago, everyone “knew” the earth was flat—it was just common sense that it had to be that way. Slightly more than a century ago, some of the leading physicians in the United States believed that women should not go to college because the stress of higher education would disrupt their menstrual cycles (Ehrenreich & English, 1979). If that bit of common sense(lessness) were still with us, many of the women reading this book would not be in college.

During the late 19th century, a common belief was that women should not go to college because the stress of higher education would disrupt their menstrual cycles. This example shows that common sense is often incorrect.

Steven Depolo – Female Black College Graduates Cap Gown – CC BY 2.0.

Still, perhaps there are some things that make so much sense they just have to be true; if sociology then tells us that they are true, what have we learned? Here is an example of such an argument. We all know that older people—those 65 or older—have many more problems than younger people. First, their health is generally worse. Second, physical infirmities make it difficult for many elders to walk or otherwise move around. Third, many have seen their spouses and close friends pass away and thus live lonelier lives than younger people. Finally, many are on fixed incomes and face financial difficulties. All of these problems indicate that older people should be less happy than younger people. If a sociologist did some research and then reported that older people are indeed less happy than younger people, what have we learned? The sociologist only confirmed the obvious.

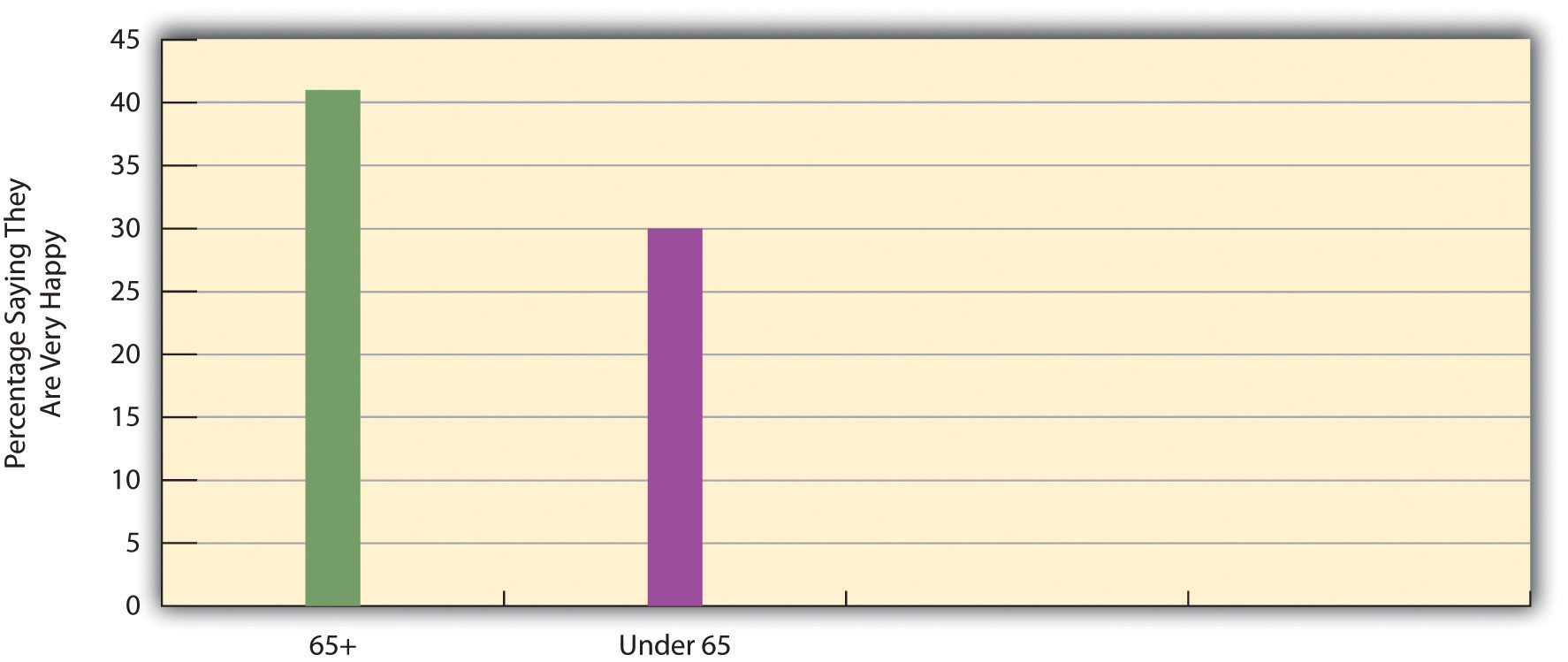

The trouble with this confirmation of the obvious is that the “obvious” turns out not to be true after all. In the 2008 General Social Survey, which was given to a random sample of Americans, respondents were asked, “Taken all together, how would you say things are these days? Would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?” Respondents aged 65 or older were actually slightly more likely than those younger than 65 to say they were very happy! About 40% of older respondents reported feeling this way, compared with only 30% of younger respondents (see Figure 2.1 “Age and Happiness” ). What we all “knew” was obvious from common sense turns out not to have been so obvious after all.

Figure 2.1 Age and Happiness

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2008.

The news media often oversimplify complex topics and in other respects provide a misleading picture of social reality. As one example, news coverage sensationalizes violent crime and thus suggests that such crime is more common than it actually is.

Wikiemedia Commons – CC BY-SA 2.0.

If personal experience and common sense do not always help that much, how about the media? We learn a lot about current events and social and political issues from the Internet, television news, newspapers and magazines, and other media sources. It is certainly important to keep up with the news, but media coverage may oversimplify complex topics or even distort what the best evidence from systematic research seems to be telling us. A good example here is crime. Many studies show that the media sensationalize crime and suggest there is much more violent crime than there really is. For example, in the early 1990s, the evening newscasts on the major networks increased their coverage of murder and other violent crimes, painting a picture of a nation where crime was growing rapidly. The reality was very different, however, as crime was actually declining. The view that crime was growing was thus a myth generated by the media (Kurtz, 1997).

Expert Authorities

Expert authorities, such as teachers, parents, and government officials, are a fourth source that influences our understanding of social reality. We learn much from our teachers and parents and perhaps from government officials, but, for better or worse, not all of what we learn from these sources about social reality is completely accurate. Teachers and parents do not always have the latest research evidence at their fingertips, and various biases may color their interpretation of any evidence with which they are familiar. As many examples from U.S. history illustrate, government officials may simplify or even falsify the facts. We should perhaps always listen to our teachers and parents and maybe even to government officials, but that does not always mean they give us a true, complete picture of social reality.

A final source that influences our understanding of social reality is tradition, or long-standing ways of thinking about the workings of society. Tradition is generally valuable, because a society should always be aware of its roots. However, traditional ways of thinking about social reality often turn out to be inaccurate and incomplete. For example, traditional ways of thinking in the United States once assumed that women and people of color were biologically and culturally inferior to men and whites. Although some Americans continue to hold these beliefs, these traditional assumptions have given way to more egalitarian assumptions. As we shall also see in later chapters, most sociologists certainly do not believe that women and people of color are biologically and culturally inferior.

If we cannot always trust personal experience, common sense, the media, expert authorities, and tradition to help us understand social reality, then the importance of systematic research gathered by sociology and the other social sciences becomes apparent.

The Scientific Method

As noted earlier, because sociology is a social science, sociologists follow the rules of the scientific method in their research. Most readers probably learned these rules in science classes in high school, college, or both. The scientific method is followed in the natural, physical, and social sciences to help yield the most accurate and reliable conclusions possible, especially ones that are free of bias or methodological errors. An overriding principle of the scientific method is that research should be conducted as objectively as possible. Researchers are often passionate about their work, but they must take care not to let the findings they expect and even hope to uncover affect how they do their research. This in turn means that they must not conduct their research in a manner that “helps” achieve the results they expect to find. Such bias can happen unconsciously, and the scientific method helps reduce the potential for this bias as much as possible.

This potential is arguably greater in the social sciences than in the natural and physical sciences. The political views of chemists and physicists typically do not affect how an experiment is performed and how the outcome of the experiment is interpreted. In contrast, researchers in the social sciences, and perhaps particularly in sociology, often have strong feelings about the topics they are studying. Their social and political beliefs may thus influence how they perform their research on these topics and how they interpret the results of this research. Following the scientific method helps reduce this possible influence.

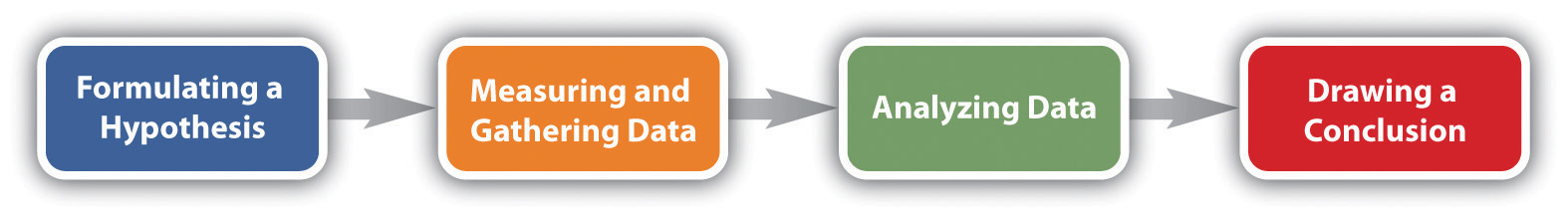

Figure 2.2 The Scientific Method

As you probably learned in a science class, the scientific method involves these basic steps: (a) formulating a hypothesis, (b) measuring and gathering data to test the hypothesis, (c) analyzing these data, and (d) drawing appropriate conclusions (see Figure 2.2 “The Scientific Method” ). In following the scientific method, sociologists are no different from their colleagues in the natural and physical sciences or the other social sciences, even though their research is very different in other respects. The next section discusses the stages of the sociological research process in more detail.

Key Takeaways

- As a social science, sociology presents generalizations, or general statements regarding trends among various dimensions of social life. There are always many exceptions to any generalization, because people are not totally determined by their social environment.

- Our knowledge and understanding of social reality usually comes from five sources: (a) personal experience, (b) common sense, (c) the media, (d) expert authorities, and (e) tradition. Sometimes and perhaps often, the knowledge gained from these sources is faulty.

- Like research in other social sciences, sociological research follows the scientific method to ensure the most accurate and reliable results possible. The basic steps of the scientific method include (a) formulating a hypothesis, (b) measuring and gathering data to test the hypothesis, (c) analyzing these data, and (d) drawing appropriate conclusions.

For Your Review

- Think of a personal experience you have had that might have some sociological relevance. Write a short essay in which you explain how this experience helped you understand some aspect of society. Your essay should also consider whether the understanding gained from your personal experience is generalizable to other people and situations.

- Why do you think the media sometimes provide a false picture of social reality? Does this problem result from honest mistakes, or is the media’s desire to attract more viewers, listeners, and readers to blame?

Ehrenreich, B., & English, D. (1979). For her own good: 150 years of the experts’ advice to women . Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Kurtz, H. (1997, August 12). The crime spree on network news. The Washington Post , p. D1.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

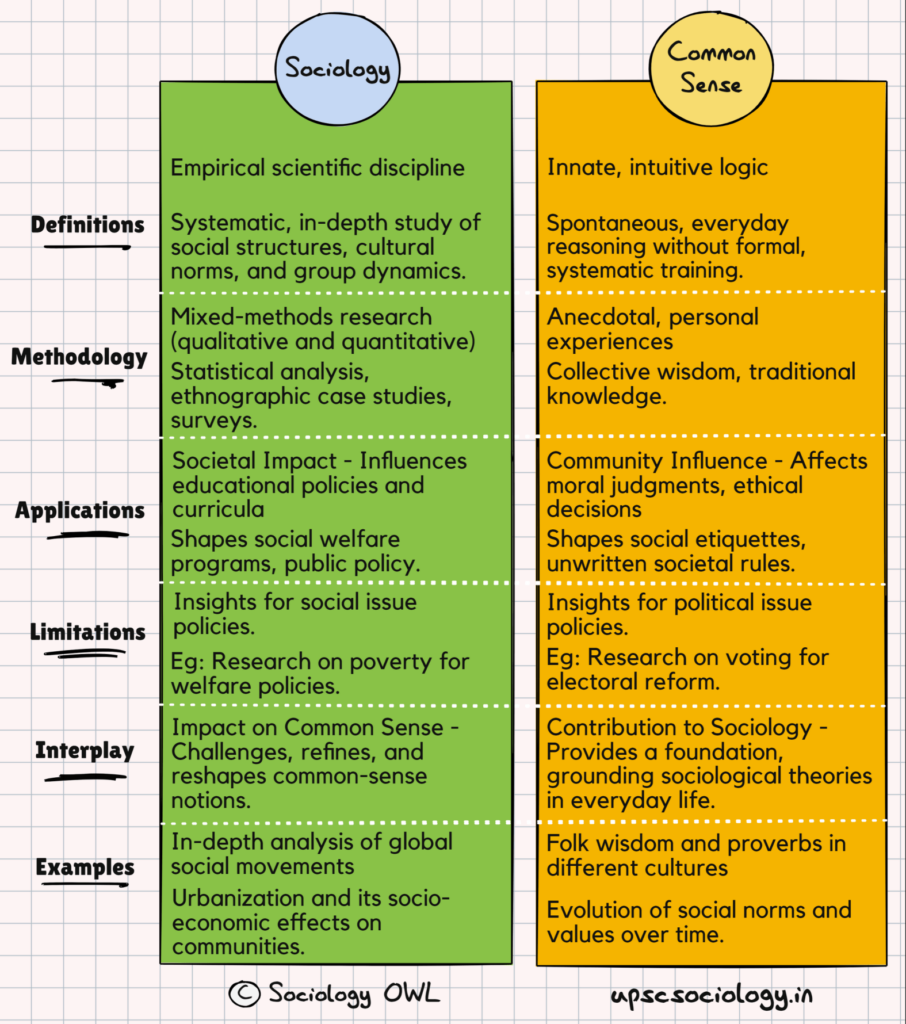

Differences between Sociology and Common sense

Sociology and common sense, unlike popular belief, do not refer to the same thing. Many people believe that sociology is just common sense. This misconception arises due to people not trying to even study sociology in the first place. In this article, I am going to discuss how sociology and common sense are different from each other.

To study this, we need to define what they exactly are. In layman terms, the social science which helps people to study the structure and dynamics of the society is called Sociology . It is more than common sense and this is why it is studied as a discipline . Common sense , on the other hand, is based on individual and natural hypotheses that one makes and this varies from person to person since opinions are not the same among a group of people. Though there is a close relationship between sociology and common sense, there is still a gap between them. While in sociology, the sociologist’s research on whether which theories are fact or fiction by elaborately researching beliefs as well as evidence, in common sense, there is no hard and fast rule that a particular theory applies to everyone (since people have conflicting opinions). Though common sense is of use at times, it is not a systematic study and not everything can be predicted correctly.

Sociology calls for a great of research and this allows for the authenticity of the data provided as well as the theories formulated. But this doesn’t imply that common sense is of no use at all. Common sense is very useful and in fact, has helped many sociologists ponder over them and probe into them. So, both common sense and sociology are different but are closely knit.

Sociology Group

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Sociological Perspective — Differences Between Sociology And Common Sense

Differences Between Sociology and Common Sense

- Categories: Social Change Sociological Perspective

About this sample

Words: 1299 |

Published: Feb 8, 2022

Words: 1299 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 956 words

1 pages / 605 words

3 pages / 1443 words

1 pages / 519 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Sociological Perspective

Poverty and crime are two societal issues that have long been intertwined in a complex and multifaceted relationship. This essay explores the intricate connection between poverty and crime, examining the root causes, [...]

The movie Coco is a film full of Mexican Culture and takes place during the Día de Muertos, Day of the Dead celebration. It’s directed by Lee Unkrich and released in 2017. The main character, Miguel Rivera loves music and [...]

John Steinbeck's short story "The Chrysanthemums" is a poignant exploration of gender roles, isolation, and the longing for fulfillment. Through the character of Elisa Allen, Steinbeck delves into the complexities of a woman's [...]

Symbolic interactionism in our society is present everywhere and on everything; Shrek from its comedic and light hearted nature proves to be an antithesis to this idea of symbolism amongst our society. Shrek is about a story of [...]

Regarding different aspects of sociological thought, the 1998 film Mulan provides many illustrations of intriguing social behavior. Mulan is about a young Chinese woman who disguises herself as a man in order to protect her [...]

“The adjustment one individual makes affects the adjustments the others must make, which in turn require readjustment.” — John Thibaut and Harold Kelley According to the textbook, the definition of Social [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

The Structure of Common Sense and Its Relation to Engagement and Social Change – A Pragmatist Account

Srdjan Prodanovic (Srđan Prodanović), geb. 1985 in Sarajevo. Er studierte Soziologie an der Universität Belgrad (Philosophische Fakultät). Promotion in Belgrad. Seit mehr als zehn Jahren (2011–2022) ist er als wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Institut für Philosophie und Gesellschaftstheorie (Universität Belgrad) tätig, wo er 2022 den Titel Senior Research Associate erwarb.

Forschungsschwerpunkte: Gesellschaftstheorie, gesellschaftlicher Wandel, Soziologie des Alltags, Philosophie der Sozialwissenschaften

Prodanović, S., 2016: Pragmatic Epistemology and the Community of Engaged Actors. Philosophy and Society 27: 398–406.

There are three approaches one can take toward the epistemic value of common sense. The pessimists will argue that common sense, due to its intrinsic tendency to reproduce prejudice and ideology, should somehow be displaced. Conversely, the optimist will maintain that common sense is a valuable type of knowledge because it prevents us from overlooking evident practical problems. This article aims to show that (a) neither of these two widespread accounts can explain why public invocation of common sense is, in fact, a reliable indicator that the reproduction of norms and rules of a given society is in crisis, and is therefore essentially a call for social engagement. And, more importantly, that (b) only the third, pragmatist approach to common sense can provide insight into its structure. This more diversified and interdisciplinary view can, in turn, shed new light on the relation between everyday knowledge and social theory.

Zusammenfassung

Es gibt drei Ansätze, die man in Bezug auf den epistemischen Wert des gesunden Menschenverstandes verfolgen kann. Die Pessimisten werden argumentieren, dass der gesunde Menschenverstand aufgrund seiner intrinsischen Tendenz, Ideologien zu reproduzieren, irgendwie verdrängt werden sollte. Der Optimist behauptet, dass der gesunde Menschenverstand eine wertvolle Art von Wissen ist, weil er uns daran hindert, praktische Probleme zu übersehen. Dieser Artikel soll zeigen, dass (a) keine dieser beiden weit verbreiteten Darstellungen erklären kann, warum die öffentliche Berufung auf den gesunden Menschenverstand tatsächlich den Aufruf zu sozialem Engagement darstellt. Und was noch wichtiger ist, dass (b) nur der dritte, pragmatische Ansatz zum gesunden Menschenverstand Einblick in seine Struktur geben kann.

1 Introduction

The term common sense has nowadays become an ever-pervasive catchphrase. Its “popularity” seems to enhance the fact that this form of knowledge has a rather controversial status in the public sphere. For some, common sense denotes a set of somehow “forgotten solutions” applicable to any kind of problem, while others hold that it represents an intrinsically unscientific and simplistic way of thinking. It is seen both as the last bulwark against “empty highbrow scholasticism” of the “elites” and as a cause for concern, since the invocation of common sense allegedly plays a crucial role in the rising tide of “anti-intellectualism” and “populism”. Accordingly, in (everyday) political life, we often hear promises that assure us that abstract (scientific) problems are in fact reducible to an understandable and communicable language of catchphrases and proverbs. These types of claims are often followed by a corollary according to which we found ourselves in this grave situation where “there is a need to make ourselves communicable again” (sic.) simply because we have lost touch with some “universally shared core values”. On the other side, (social) scientists – especially sociologists – have traditionally been suspicious of any kind of everyday knowledge. Even if we can find relatively sympathetic views on its importance in interactionist sociology, perhaps most notably in the works of Garfinkel (1967) and Goffman (1974), the prevailing view among sociologists ( Merton 1968, 22; Manis 1972) has been that common sense is, as Watts eloquently observes, “the Rodney Dangerfield of epistemologies” ( Watts 2014: 13) and therefore deserves no scientific recognition.

After Brexit, and the overall rise of populist movements in Europe, as well as the election of Donald Trump as the US president, this skepticism regarding common sense has only increased. With these developments, social scientists have found themselves in this rather strange situation where some of them feel obliged to get socially engaged and debunk the retrograde populist rhetoric threatening the democratic procedures of the society. And yet, the path of engagement seems to entail that this skepticism regarding common sense in fact needs to be widely communicable to all actors of the public sphere in such a way that avoids both the pitfalls of demagogy and the exclusivity of elitism. In other words, for aforementioned scientists the central question is how to change common sense through (theoretically informed) common sense? Efforts to answer this kind of issues will be at the heart of this paper. [1]

The following text will be structured in six sections. In the first two sections, we will describe three widespread approaches to common sense and argue why the pragmatist outtake, exemplified in the works of Dewey and Peirce is the most promising one when it comes to theoretically understating this type of knowledge. Then, we will consider how the pragmatist understanding of common sense influenced modern sociological theory – most notably interactionist sociology. In the fourth section we will rely on Donald Davidson’s philosophy of language in order to describe the structure of common sense and also try to illustrate how this “diversification of common sense” might resolve some of the shortcomings regarding issues that we detected in interactionist sociology. Finally, in the last two sections, we will consider how our account of the structure of common sense provides a more nuanced understanding the complex history that lies behind the distinction between common and good sense which will in turn help us to a differentiate theoretical interconnections between different elements of the mentioned structure, social engagement and (radical) social change. Finally, we will outline common sense engagement and goods sense engagement as one more theoretical avenue for achieving Burawoy’s plea (2005) for public sociology.

2 Framing Common Sense

Our preliminary effort to analyze common sense more systematically must start from the fact that both its apologists and critics seem to agree that it provides an inherently intersubjective mode of reduction of the complexity found in our social and natural environment, which in turns enables intervention and engagement with (pressing) practical problems. In this regard, common sense type of problem-solving always refers to an already constructed and relatively stable body of social customs and institutions. It is precisely this fusion between our personal and communal epistemological capabilities which makes common sense such an interesting and often controversial notion.

As already suggested, there are more ways in which one can approach this hybrid nature of common sense. First, there is the optimistic account according to which commonsense knowledge is a perfectly sufficient cognitive resource for regulating our daily political and social life. Taken to its extreme, this view of the apologists of common sense is deeply conservative since it holds that “common sense solutions” can resolve any practical issue – even those that are immensely complicated; such as financial crises and climate change. Moreover, this conservative outtake ( Holthoon & Olson 1987) also implies that “fancy talk” found in scientific or philosophical knowledge, in fact, muddies the clear waters created by the commonsense approach of “regular folks”, and when that happens it is up to the conservatives to make sure that we “return” to common sense.

Secondly, there is the pessimistic account which holds that common sense has almost no epistemological value because it is contradictory, incoherent and (to a great degree) culturally biased ( Geertz 1975). Authors who denounce common sense on this ground usually admit that this type of knowledge presents a starting point for proper scientific investigation, but at the same time claim that (social) science should somehow progressively displace all kinds of everyday knowledge ( Bernstein 1971: 282). The progress of a given community according to this account of the critic and the expert depends on the proper distribution of scientific knowledge that is done by the epistemologically privileged members of that community ( Ackerman 2014).

Finally, there is the pragmatist account according to which common sense is both the starting point and the ultimate goal of scientific knowledge ( Dewey 1948; Taylor 1947; Hookway 2006), since no matter how technical the vocabulary of science might get, it still must remain relevant and transferrable to practical problems that are selected and defined using commonsense vocabularies. According to this approach, the relationship between common sense and science is not antagonistic and is in fact seen as a form of partnership.

In this paper, we will try to show that this third holistic approach is of key importance for understating why exactly common sense is epistemologically relevant for social sciences. But, perhaps more importantly, the pragmatist account can also inform us on how social sciences could engage with pressing social issues without invoking accusations of “empty scholasticism”, “fancy talk” and elitism on the one side, and on the other, charges of shallow-mindedness and populism that respectively follow the optimistic and pessimistic approach to common sense.

3 Intersubjectivity Of Common Sense and Its Relation to Social Science – Reconstructing the Pragmatist Approach

Epistemological considerations of common sense usually imply some universal and mutually shared cognitive and/or emotional capabilities of our mind that enable us to follow a common interpretive scheme, and allow us to interact with each other and our natural surroundings. When the problem is formulated in this manner, it is of course hard not to consult some of the voluminous literature from cognitive science and developmental psychology ( Greenwood 1991; Bloom 2005; Ratcliffe 2006; Bogdan 2008; Andrews 2012) that focuses on folk psychology – a term that at surface seems to be synonymous with common sense. The two most dominant and often opposing views on the nature of folk psychology are the theory-theory and the simulation theory. Proponents of the first school of thought (for example, Bloom 2005) claim that we create innate theories about natural surroundings and mental states of others that we subsequently modify and develop during our social interactions. Conversely, simulation theory proposes that we ascribe beliefs and desires to other people based on our own inner mental experience, that is, proponents of this theory claim that during social interaction we try to mentally simulate the most relevant beliefs and desires of others in order to figure out how to attain mutual understanding and take the appropriate course of action. Both the theory-theory and the simulation theory refer to problems of intersubjectivity, as one of the central issues surrounding common sense. However, there is a subtle and yet important difference in the way in which cognitive science and psychology approach common sense intersubjectivity and the way sociologists have treated this issue. Namely, while the concept of folk psychology is focused on the question of how we attain intersubjectivity in the first place, sociologists are much more interested in social factors that enable or hinder the reproduction of the (already established) intersubjectivity of customs and habits found in a given culture.

This idea that common sense is intrinsically intersubjective is deeply rooted in modern sociological theory. In Common-Sense and Scientific Explanation of Human Action , Schutz (1953) notices that we cannot reduce common sense just to problems of ascribing beliefs and desires to others, since the course of social life in our everyday interactions presupposes an established community with already posited intersubjective norms of interpretation of these interactions. [2] Therefore, he insists that common sense is an “intersubjective world of culture” and goes on to claim:

“It is intersubjective because we live in it as men among other men, bound to them through common influence and work , understanding others and being understood by them. It is a world of culture because, from the outset, the world of everyday life is a universe of significance to us, that is, a texture of meaning which we have to interpret in order to find our bearings within it and come to terms with it ” (Schutz 1953: 7) (emphasis added)

Schutz’s insight brings two important points to the foreground. Namely, common sense is something that society or some specific group demands that we adopt – in other words, it is a form of social obligation that regulates a vast amount of daily social interactions. Second, although these rules of commonsense interpretation are socially bound, they at the same time pertain to a particular problem we find ourselves in during the course of our everyday life. Therefore, every use of common sense entails a constant search for the “middle ground” between, on the one hand, the socially determined “texture of meaning” which is routinely applied to concrete situations, and, on the other, our own bearings within the lifeworld that are based on particular interpretive endeavors aimed at modifying this texture in light of contingency that surrounds human action ( León 2016: 167–8). [3] Common sense should, therefore, be seen as a form of knowledge that bridges the gap between the social structure that we perceive as customs and norms and our own (individual and group) intentions and desires that aim to reshape them and, in the case of a more radical situation, to change them entirely.

The complexity of this “middle ground” is of key importance in any attempt to understand the relation of common sense with other forms of knowledge. Let’s now examine how the three accounts of common sense that we previously outlined approach this complexity. If one fosters an optimistic view of common sense he will probably claim that “ our culture” or “our tradition” give plenty of epistemological resources to resolve any problem at hand. We just perhaps need to tweak our commonsense knowledge to the peculiarity of the concrete problem. However, we can relatively quickly “stop talking and start getting things done” (provided that our action does not run too much against our tradition). Reflection and abstraction that give a more complex take on the problem at hand are thus seen as unnecessary, or even as a dubious attempt to slow down the much-needed action. Although this approach to common sense is more often found in politics and journalism, it could be claimed that the earliest theoretical considerations of common sense, like those of Reid, Beattie and other proponents of the “Scottish Enlightenment”, fall fairly close to this outtake ( Boulter 2007; Rosenfeld 2011). One of the biggest issues for all proponents of this approach is precisely this need to “guard” or plead for something which is so self-evident and culturally rooted as a resource for figuring out the best possible solution for any practical problem.

On the other hand, the tendency of common sense to reproduce already established norms and customs is the chief reason why the critical or pessimistic approach maintains that common sense must be deconstructed and displaced with a more reflexive and analytical form of common knowledge. This critical stance – which focuses on the fact that common sense is an emanation of historical, cultural and structural givenness – is typical both for structuralists and post-structuralists. Broadly speaking, the former maintain that the change in some underlaying features of the system will cause “ordinary actors” to “let go” of their common sense interpretations of social reality and adopt a more complex worldview based on an ever more precise scientific or theoretical method which ultimately warrants social progress, while the latter tended to claim that common sense (which, according to poststructuralists, also nurtures various hypostatized terms produced in science) needs to be brought into question through permanent negation by showing its genealogy or sedimentation of meaning. Both variations of the pessimist account of common sense remain clearly focused on its alleged inert nature regarding the current normative order which is then used in the ideological justification of this order. [4] The main problem of this approach is that it fails to understand the adaptive nature of common sense, as well as that this knowledge holds the actors’ identity in coherence [5] – which is why displacing common sense is a much more difficult task than simply proving that it is determined by the current normative order.

Finally, as already suggested in the introduction, the holistic or pragmatist position on common sense maintains that it can be changed through theory and social science, but also that it has the potential of fostering more comprehensive – and yet intersubjective – acts of social critique and engagement. The most distinctive feature of this outtake on common sense – found in some varieties of phenomenology, interpretive sociology, critical theory – would, therefore, be that there is no rigid boundary between practice and theory.

However, one could argue that pragmatism, in fact, played a key role in the formation of this complex take on common sense. Namely, from the very beginning of the pragmatist movement at the end of the 19 th century, one of the key preoccupations was how to create a profound connection between thought and action. As we shall see, common sense was to provide this mediation. For example, Peirce was very critical of the Cartesian absolute doubt, claiming that rather than dismissing prejudices using maxims, we need to nurture “real and living doubt”, urging us not to “pretend to doubt in philosophy what we do not doubt in our hearts” (quoted according to: Hookway 2006: 210). He thus claimed that common sense is an important factor in both starting and settling a rational debate. This collective sense of certainty that surrounds common sense knowledge strongly influences our abductive reasoning, that is, those “ideas about what sorts of theory should be taken seriously in trying to explain phenomena” (Hookway 2006: 211). This is why the so-called “second-level abstractions” ( Rosenthal 1994: 15) of science are inherently connected to common sense knowledge used in everyday experience. On the other hand, Peirce does not glorify common sense, because having “living doubt” for him meant that one applies “critical common-sensism”, which entails a “critical acceptance of uncriticizable propositions” ( Peirce 1974: 346). Therefore, according to Peirce, as pragmatists, we should have only one fear: petrification of knowledge. In that regard, it does not matter if common sense or Cartesian philosophy are offering absolute epistemological certainty – their promises are false simply because they exclude potentially more coherent explanations that might be developed in the future.

Building on these insights, in his Common Sense and Science: Their Respective Frames of Reference (1948), Dewey states that common sense and science must be seen as transactions, adding that this means “that neither common sense nor science is regarded as an entity – as something set apart, complete and self-enclosed” (Dewey 1948: 197). Apart from highlighting anti-essentialism, this metaphor of transaction aims also to point out the fact that the two forms of knowledge are bound to be in continuous partnership, as well as that through transaction both common sense and science undergo a change that prevents their petrification. [6] According to Dewey, we need this flexible and holistic approach to common sense because the environment is an (indistinguishable) interplay between social and cultural factors:

“What is called environment is that in which the conditions called physical are enmeshed in cultural conditions and thereby are more than ‘physical’ in its technical sense. ‘Environment’ is not something around and about human activities in an external sense; it is their medium , or milieu , in the sense in which a medium s inter mediate in the execution of carrying out all human activities, as well as being the channel through which they move, and the vehicle by which they go on” (Dewey 1948: 198) (original emphasis).

Here Dewey, much like Schutz, also points out the importance of the pre-given intersubjective world that is socially binding. However, there are two important twists within this position that are also typical for pragmatists. Namely, when Schutz justifies the importance of this pre-given intersubjective world, he follows a general phenomenological line of reasoning and bases his claims on the social structure of the self. Somewhat conversely, Dewey in his definition of environment wants to go beyond strict distinctions between the self, community and our surroundings; arguing that we should instead focus our attention on the process of interaction between these different aspects of environment. And common sense is in that regard valuable because it cognitively and emotionally expresses this interaction. This pragmatist holism further implies that common sense and science must also interact (make transactions) with each other and undergo a change from within during this process. Thus, from the pragmatist perspective, the whole idea of some sort of rigid, “displaceable” distinction between theory and practice or common sense and science is unacceptable.

Common sense according to pragmatists is to a lesser degree abstract knowledge that both cognitively and emotionally denotes concrete practical problems (Dewey 1948: 208). This “hybrid” character of common sense is crucial for our abductive intuitions regarding the process of collectively selecting and solving problems. On the other hand, scientific knowledge has the “liberating effect of abstraction” (Dewey 1948: 206) that enables scientists to make connections between distant parts of the environment. When thinking about distinctive concerns of science and common sense Dewey claims:

“It consists of the position occupied by each member in relation to the other. In the concerns of common sense knowing is as necessary, as important, as in those of science. But knowing is there, for the sake of agenda the what and the how of which have to be studied and to be learned – in short, known in order that the necessary affairs of everyday life be carried on” (Dewey 1948: 205).

Therefore, one could argue that this difference in focus is at the heart of something that we might call the pragmatist critique of common sense. Namely, being critical for pragmatists [7] means being relevant within the given community regarding the problems and concerns that are raised through common sense, while at the same time trying to make our common sense more complex and reflexive by providing insight into the ways in which the mentioned problems are connected through infinitely complex environment.

4 Some Sociological Implications of The Pragmatist Approach to Common Sense

Views developed by pragmatists profoundly influenced modern sociological theory. Perhaps the most important sociological work that “bears the mark” of the pragmatist account of common sense was done by interactionist sociologists, especially Garfinkel and Goffman. According to Garfinkel’s ethnomethodology, [8] positivist sociology tended to (over)standardize human social behavior by claiming that particularistic knowledge does not affect the overall functionalist model of social behavior which arguably explains the reproduction of a given culture ( Heritage 1991; Emirbayer & Maynard 2011: 239). Thus, he accused this at the time dominant paradigm of being epistemologically authoritarian. According to Garfinkel, this approach to social sciences reduces “the ordinary actor” to a mere “cultural dope” who “produces the stable features of the society by acting in compliance with pre-established and legitimate alternatives of action that the common culture provides” ( Garfinkel 1967: 68). And the most important characteristic of this procedure which renders everyday action irrelevant is its total disregard of common sense:

“The common feature in the use of these [dope-like] ‘models of man’ is the fact that courses of common sense rationalities of judgment which involve the person’s use of common sense knowledge of social structures over the temporal “succession” of here and now situations are treated as epiphenomenal” (Garfinkel 1967: 68).

For Garfinkel, therefore, social structure cannot be properly sociologically explained without understanding the laymen methods in which these structures are enveloped and embodied within everyday practices. The commonsensical approximation of these structurally determined and relatively stable rules for interpreting social action, that is, the ways in which we follow and re-articulate them within concrete everyday situations, is of key importance for every sociological theoretical endeavor that wishes to avoid the pitfalls of epistemological authoritarianism. In that regard, Garfinkel’s view on common sense can also help us understand why someone might resent reductionist explanations of their behavior: simply put, no one likes to have his knowledge of the social structure denied because no one likes to feel like a dope, especially a dope regarding his own culture (which is an unfortunate implication of the pessimistic account of common sense).

One could likewise argue that Goffman’s work presents another example of the pragmatist approach to common sense. In his Frame Analysis, Goffman right from the outset dismisses a reductionist approach to everyday experience: “To uncover the informing, constitutive rules of everyday behavior would be to perform the sociologist’s alchemy — the transmutation of any patch of ordinary social activity into an illuminating publication”( Goffman 1974: 5). Frame analysis, according to Goffman, must show how general presuppositions about the meaning of social interaction are continuously modified in concrete social situations. In other words, common sense as the knowledge that fosters both these general presuppositions and particular modifications of rules that govern social interaction cannot be avoided – or for that matter “bracketed”, “deconstructed” or displaced – by any other form of theoretical abstraction ( Craib 1978: 80; Scheff 2005: 370):

“I assume that when individuals attend to any current situation, they face the question: ‘What is it that’s going on here?’ Whether asked explicitly, as in times of confusion and doubt, or tacitly, during occasions of usual certitude, the question is put and the answer to it is presumed by the way the individuals then proceed to get on with the affairs at hand” (Goffman 1974: 8).

Framing process [9] according to Goffman refers to the common sense organization of social experience, or more precisely, to translating contingent situations into intersubjective schemes of meaning. This translation is achieved through linguistic experimentation – or as Scheff points out “shuffling through vocabularies” (Scheff 2005: 382). However, it is important to notice that unlike Garfinkel, Goffman holds that common sense cannot be a stable form of knowledge that could be “taken for granted” primarily because framings of the given situation can be so different that ultimately one could argue that all actors found within one face-to-face interaction are not witnessing the same event. [10]

Another effort to stress the importance of common sense comes from the “pragmatic turn” in Bourdieu’s sociology that was mainly put forward by Boltanski and Thévenot. In their On Justification (2006) they argue that beneath the seemingly crude way of creating and resolving conflicts found in everyday life lies a profound and complex set of both individual and collective strategies that are ultimately based on various (common sense) “systems of worth”, or “polities”, as Boltanski and Thevenot like to call them (Boltanski & Thévenot 2006: 74–80). The purposeful act of “shuffling through polities” caused by the contingency of everyday practice makes “ordinary actors” able to see the cracks in structural and historically pregiven social structures ( Celikates 2006: 31) – which constitutes the starting point of social critique:

“Our intent here … is to treat instances of agreement reaching and critique as intimately linked occurrences within a single continuum of action. Contemporary social scientists often seek to minimize the diversity of their constructs by situating them within a single basic opposition … Our own perspective offers a third approach: we seek to embrace the various constructs within a more general model, and to show how each one integrates, in its own way, the relation between moments of agreement reaching and moments of critical questioning” (Boltanski & Thévenot 2006: 25)

If Garfinkel and Goffman articulated a modern version of pragmatist holism in the sense that they gave us a sociological insight into the pivotal role that common sense plays in rendering social situations intersubjective, then Boltanski and Thévenot surely created a very comprehensive elaboration of the sociological importance of the pragmatist [11] critique of common sense. The public role of the sociologist therefore in some sense lies beyond the everlasting debate of the scientific relevance of common sense knowledge and should be, as Cyril Lemieux points out, conceived in terms of “clarification and stylization of the rules that organize … common sense” ( Lemieux 2014: 155). [12]

However, even if these sociological implementations of pragmatist holism help us to understand the epistemological importance of common sense, they still remain shorthanded regarding our ability to comprehend the controversial nature of this form of knowledge. For example, both Garfinkel and Goffman explain the “epistemological hazards” sociologists are exposed to when they try to displace everyday knowledge. In a similar vein, Boltanski and Thévenot help us to understand how pragmatist account of common sense might bring about a change in the normative order. Nonetheless, neither of the mentioned sociological models does a good job of explaining why common sense has both a stabilizing and de-stabilizing property when it comes to social structure. I think that one of the reasons for this outcome lies in the fact that Garfinkel, Goffman, Boltanski and Thévenot share a rather homogeneous view on common sense. As we have seen, according to these authors, the ability of common sense to connect the pre-given intersubjectivity of social customs and the particularistic modifications of these customs that are tailored towards solving concrete practical problems under one interactionist scheme makes common sense an indispensable factor in our interaction with the natural and social environment. This, of course, is an important insight, but we also must bear in mind that this seemingly homogeneous form of knowledge is in fact filled with the tension between the world we are socialized in and the one in which we are currently acting and actively changing. Moreover, neither of the aforementioned approaches in sociology can account for the fundamental paradox: that invoking common sense means that we commonsensically understand that some part of the interpretive scheme of common sense doesn’t make sense anymore. In other words, the contingency of social action might put us in a situation where the pre-given nature of common sense loses intelligibility and where we are left only with (particularistic) modifications of common sense as the source of the intersubjectivity of everyday practice. This, in turn, suggests that common sense itself has some sort of internal structure and dynamics that is closely related both to the reproduction of the normative order and to its change.

5 The Structure of Common Sense

Perhaps the easiest way to envision the internal dynamics within the structure of common sense would be to frame the problem of its universality and particularity in linguistic terms. In that regard, the “universal texture of meaning” that we develop through socialization could be redefined as a general vocabulary that was learned with the help of our peers, while, on the other hand, the particularistic modification of this general vocabulary that was forged to tackle concrete situations would be seen as a form of idiolect. If we make this analogy, then complex problems surrounding the issue of how contingency effects the reproduction of structurally pre-given norms of interpretation of everyday life could be further analyzed from a relatively new, neopragmatist, perspective. What the neopragmatist blend of analytic philosophy and classical pragmatist holism brings to the table is a relatively robust theory of translation which can hopefully help us understand how exactly particularistic knowledge attains intersubjectivity, as well as how the convergence of different particularistic commonsensical insights might change the universal norms of everyday understanding or the intelligibility of social action.

When in his A Nice Derangement of Epitaphs (2006), Donald Davidson ponders the nature of language competence, he makes a rather revealing distinction between prior theories and passing theories . Namely, according to Davidson, prior theories fall close to what we colloquially call “the dictionary meaning” in the sense that they “… come first in the order of interpretation” ( Davidson 2006: 253). From our early childhood, we adopt numerous tokens of language competence; we learn the meanings of words and non-verbal gestures, and later in life, we adopt peer jargon and enter adulthood with an array of specialized or vocational vocabularies. This type of socially and culturally pre-given “dictionary knowledge” is a necessary condition for making any kind of social action intelligible. However, as we know, everyday life communication is full of inaccuracies, misunderstandings and flat-out blunders that cannot be predicted in advance and therefore cannot be part of any general vocabulary. According to Davidson, from these instances of linguistic contingency emerges a set of particularistic, or as he calls them, passing theories of meaning which aim to attain intersubjectivity even though they were caused by “miscommunication”. This is why malapropisms are illustrative and important; when the speaker utters: “I wish to dance the flamingo” or “all people are cremated equal” the interpreter gets the intended meaning in spite of the fact that both the speaker and the interpreter do not have a pre-given scheme of interpretation. Davidson summarizes the relation between first and passing theories in the following way:

“For the hearer, the prior theory expresses how he is prepared in advance to interpret an utterance of the speaker, while the passing theory is how he does interpret the utterance. For the speaker, the prior theory is what he believes the interpreter’s prior theory to be, while his passing theory is the theory he intends the interpreter to use” (Davidson 2006: 260–61).

If we take a closer look, Davidson’s analysis of malapropisms implies that pre-given norms of interpretation, strictly speaking, cannot be intersubjective because the success of any given communication depends on the correctness of the speaker’s belief regarding how the hearer is ready to interpret him – which can vary wildly during the speech interaction. Therefore, mutual understanding cannot be determined through prior theories simply because they stand outside of the realm of concrete speech situations. However, prior theories are still important because they are in some sense a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for entering concrete speech situations.

“Stated more broadly now, the problem is this: what interpreter and speaker share, to the extent that communication succeeds, is not learned and so is not a language governed by rules or conventions known to speaker and interpreter in advance; but what the speaker and interpreter know in advance is not (necessarily) shared, and so is not a language governed by shared rules or conventions. What is shared is, as before, the passing theory; what is given in advance is the prior theory, or anything on which it may in turn be based” (Davidson 2006: 264).

Here Davidson draws our attention to the fact that although prior theories provide to the speakers the initial intelligibility of the concrete speech situation, their intersubjectivity is far from warranted. In other words, just because we are socialized to have beliefs regarding how a situation might be interpreted does not mean that these beliefs will be mutually shared once we find ourselves within concrete (speech) practice ( Lepore & Ludwig 2007: 271–73; Turner 2001: 130). [13]

We can now use Davidson’s insight into everyday communication in order to shed some new light on our initial question regarding the dynamics and structure of common sense. The first aspect of this structure which pertains to concrete everyday situations we will call everyday common-sense knowledge . This is the world that Garfinkel and Goffman depict in their sociologies, a world where people ask “what is going on here” and then very often, quite competently, get the answer they were looking for. This type of common sense is utilized in those situations where the problem at hand does not require much abstraction, and therefore solutions remain more or less obvious. Everyday commonsense knowledge can thus be defined as particularistic knowledge obtained through individual interactions with natural and/or social environment which remains applicable to a limited number of situations. Although we navigate through everyday practice using competences that are gained through various institutions, one can hardly ignore the fact that our daily routines also generate relatively separate type of knowledge which is based on idiosyncrasies of individual experience and situations. In other words, everyday commonsense knowledge is extremely variable and therefore resists total determination. In that regard, it falls close to Davidson’s passing theories because everyday commonsense knowledge is the vocabulary that we deploy in order to obtain intersubjectivity and mutual understanding. It is precisely this type of common sense that must converge between different actors when contingency obstructs the reproduction of everyday practice. From the perspective of Garfinkel’s and Goffman’s sociology, everyday common-sense knowledge is the knowledge of indexical modifications of common understanding – or particularistic re-framings – that are generated within new social experiences. The fact that this type of knowledge is particularistic can raise the objection that we are advocating here some sort of psychologism or extreme nominalism. However, everyday common-sense knowledge is a product of the convergence of idiosyncrasies and in that regard, it is intrinsically social, which means that we can set aside worries about this kind of reductionisms. Finally, everyday common-sense knowledge is limited in its universalizability because of its extreme context-dependence. [14] This restricted universalizability is the main reason why this type of common sense remains confined to the realm of everyday practice. In other words, it cannot be codified into abstract rules that usually govern institutions.

Now we come to the second dimension of common sense which is much more abstract in its nature. This aspect of structure of common sense, which we shall call common-sense quasi-theories , can be defined as a set of historically generated and metaphysically based rules that to a variable degree instruct the way in which we form and use everyday commonsense knowledge. Let’s take a closer look at the first part of the definition. What exactly do we mean when we say that the quasi-theories are historically generated and metaphysically founded? Here we first want to stress the fact that, through socialization, social actors adopt and interiorize social conventions that provide the initial intelligibility of social situations, as well as cognitive resources for solving potential practical misunderstandings. In other words, quasi-theory refers to those commonsense insights that are a part of tradition or culture which are therefore inherently historical. However, from the perspective of an actor that habitually acts using commonsense quasi-theory, these cultural resources are not understood as a product of uncertain complex historical development, conflict and struggle, but rather as something which is “self-evidently” valid and eternal. This tendency of essentializing and petrifying culture is the main reason why common-sense quasi-theories are also metaphysical. The second part of our definition states that quasi-theories aim to determine the “lower level” everyday commonsense knowledge. Namely, as already mentioned, ad hoc solutions of everyday knowledge of common sense cannot be effectively socialized. Therefore, if we are to embark upon any type of communicative acts, we need initial rules which will guide our interpretation of social interaction. This is why in the early childhood actors adopt culturally coded abstract notions which overcome the idiosyncrasies and provide typification of all particular social situations. The metaphysical nature of quasi-theories certainly helps in “bridging the gaps” in the stream of our everyday social life. However, this feeling of continuity comes at a cost; the eternal metaphysical perspective of quasi-theories is often used for providing a specific justification of institutions and customs which goes beyond the contingencies of everyday social life – and history for that matter – and thus perpetuates current structural inequalities and injustices. This rationalization of structural asymmetries is the main reason why in the eyes of some social theorists, as is the case with Bourdieuan sociology and critical theory, common sense is seen as an embodiment of social domination.

As we can see, common-sense quasi-theories fall close to Davidson’s understanding of prior theories in that they provide the intelligibility of social interaction. But, as Davidson has shown, the more abstract and codified linguistic rules which provide the intelligibility of social interaction can never entirely determine ad hoc rules that are formed within concrete social practice. The main reason for this indeterminacy between two vocabularies of common sense lies in the contingency of language and our everyday practice. This unresolvable instability of meaning formation within the structure of common sense can help social theory to understand both the dynamics of common sense and the modes of engagement between theory and practice. According to our account, common sense always presents itself to social actors as something unquestionably valid and self-evident, even though they must, on daily basis, derail from their quasi-theoretical hypotheses and form with their peers more specific meanings of concrete social problems and situations based on everyday commonsense knowledge. From here it is easy to claim that if the convergence of everyday commonsense knowledge is wide enough it can change the quasi theories and become a new social custom or basis for engaged social action. It is also very important to highlight that regular theoretical and scientific knowledge can comprehend and describe the contingency of social practice and change quasi-theories and, consequently, to a degree alter everyday common-sense knowledge. Our education can also largely modify the quasi-theoretical worldview which could consequently change the way in which we approach a practical misunderstanding and form the intersubjectivity within the concrete instances of social interaction. [15] Therefore, one could argue that the role of social theory is twofold: on the one hand, it needs to uncover and interconnect those situations in which quasi-theories have lost their potential to generate intelligibility of social interaction, while on the other it needs to analyze and critique quasi-theories in order to render them more adaptive towards contingency of everyday life (or in some circumstances altogether change them). In this way, social theory remains critical towards common sense without the risk of being reductionist or metaphysically irrelevant when it comes to issues of everyday social practice.

This abstract account of common sense certainly demands a more concrete illustration. Hence, in the next section we will try to give a few examples of how our understanding of structure of common sense might help settle some of the controversies that have followed common sense throughout its history.

6 Common Sense and Good Sense Modes of Social Engagement

The structure of common sense that we have laid out in the previous section can also help us to understand how common sense ignites social engagement and brings about social change. Namely, common sense has always been in some regard a paradoxical notion. Indeed, if some statement is self-evident why is controversy always somehow shadowing it? The shortest possible answer would be that invocation of common sense in fact usually marks some sort of hindrance of mutual understanding. This inherently intersubjective sense that intersubjectivity of social interaction is endangered causes the actors to reflect upon social rules and norms which otherwise might remain a matter of habit or custom. [16] This type of collective reflection on rules is at the heart of what we colloquially call “engagement”. In other words, when we invoke common sense we are basically stating that norms and rules of interaction need to be attended or altogether changed.

The close connection between the structure of common sense that we introduced in the last section and the perceived crises of intersubjectivity has followed the term from its very beginning – and its history is somewhat surprisingly relevant for the issues we have raised in this paper. As Sophia Rosenfeld points out in her inspiring book, Common Sense: A Political History : “Common sense generally only comes out of the shadows and draws attention to itself at moments of perceived crisis or collapsing consensus” (Rosenfeld 2011: 24). According to her opinion, the modern historical starting point of common sense came with Shaftesbury’s modification of the Aristotelian idea of κοινὴ αἴσθησις or sensus communis – which roughly refers to the one sense that binds all others in both humans and animals ( Gregoric 2007) – into a much more culturally situated notion. Namely, in Shaftesbury’s interpretation there is a mutually binding sense that reflects “the public weal and [is] of the common interest” (quoted according to: Rosenfeld 2011: 23, see also: Klein 1994; Rivers 2000). Shaftesbury’s innovation had big political implications because if there is an innate cognitive sense to apprehend common interest which is – as is the case with sight and hearing – evenly distributed among the population, then we can develop an entirely secular mode of public deliberation. This modern formula of common sense which combines epistemology (because it deals with interpretation), social ontology (because it deals with inherently group modes of interpretations) and policy (because these group interpretations pertain to practical issues and public life) had two major developments: common sense and good sense.

Although this distinction has never been clear-cut, one could argue that from a historical perspective it is rather obvious that common sense was first conceptualized in its modern form at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century as a relatively conservative cognitive means for gradual social change which would be justified in a secular manner. This “epistemological populism” as Rosenfeld calls it, was first successfully used by the Aberdeen members of the so-called Scottish Enlightenment as a safeguard against the “anomic tendencies” of English empiricism. Reid and Beattie, who were the main proponents of common sense at the time, were mainly worried that “philosophical skepticism” advocated both by Locke and Hume entailed corrosive doubt which could introduce relativism into everyday life and thus ultimately render it meaningless. Therefore, according to Reid, we should base our knowledge on common sense principles which are “unconditionally given to all men” ( Reid 1785: 506) and reflect “the consent of ages and nations, of the learned and unlearned” (1785: 43).

As we can see, even in its early days, common sense is understood as a form of collective consent , that is, as something which is extremely stable, but not (necessarily) metaphysically petrified. In other words, when someone calls for common sense, he is in fact calling for a Peirceian “everyday grounded doubt” that takes into account both the “mind and heart” when questioning the current social norms. If we fail to do this, then Beattie, in a rather pragmatist tone, warns us that “When Reason invades the Rights of Common Sense, and presumes to arraign that authority by which she herself acts, nonsense and confusion must of necessity ensue; science will soon come to have neither head nor tail, beginning nor end” ( Beattie 1805: 153). Therefore, when conventional rules of social interaction fail to account for contingent practical issues – something Boltanski and Thevenot call “tests” (Boltanski & Thévenot 2006: 133–38) – and when we wish to amend the given social order, we will say that common sense demands the correction of social norms.