A Guide to Lyric Essay Writing: 4 Evocative Essays and Prompts to Learn From

Poets can learn a lot from blurring genres. Whether getting inspiration from fiction proves effective in building characters or song-writing provides a musical tone, poetry intersects with a broader literary landscape. This shines through especially in lyric essays, a form that has inspired articles from the Poetry Foundation and Purdue Writing Lab , as well as become the concept for a 2015 anthology titled We Might as Well Call it the Lyric Essay.

Put simply, the lyric essay is a hybrid, creative nonfiction form that combines the rich figurative language of poetry with the longer-form analysis and narrative of essay or memoir. Oftentimes, it emerges as a way to explore a big-picture idea with both imagery and rigor. These four examples provide an introduction to the writing style, as well as spotlight tips for creating your own.

1. Draft a “braided essay,” like Michelle Zauner in this excerpt from Crying in H Mart .

Before Crying in H Mart became a bestselling memoir, Michelle Zauner—a writer and frontwoman of the band Japanese Breakfast—published an essay of the same name in The New Yorker . It opens with the fascinating and emotional sentence, “Ever since my mom died, I cry in H Mart.” This first line not only immediately propels the reader into Zauner’s grief, but it also reveals an example of the popular “braided essay” technique, which weaves together two distinct but somehow related experiences.

Throughout the work, Zauner establishes a parallel between her and her mother’s relationship and traditional Korean food. “You’ll likely find me crying by the banchan refrigerators, remembering the taste of my mom’s soy-sauce eggs and cold radish soup,” Zauner writes, illuminating the deeply personal and mystifying experience of grieving through direct, sensory imagery.

2. Experiment with nonfiction forms , like Hadara Bar-Nadav in “ Selections from Babyland . ”

Lyric essays blend poetic qualities and nonfiction qualities. Hadara Bar-Nadav illustrates this experimental nature in Selections from Babyland , a multi-part lyric essay that delves into experiences with infertility. Though Bar-Nadav’s writing throughout this piece showcases rhythmic anaphora—a definite poetic skill—it also plays with nonfiction forms not typically seen in poetry, including bullet points and a multiple-choice list.

For example, when recounting unsolicited advice from others, Bar-Nadav presents their dialogue in the following way:

I heard about this great _____________.

a. acupuncturist

b. chiropractor

d. shamanic healer

e. orthodontist ( can straighter teeth really make me pregnant ?)

This unexpected visual approach feels reminiscent of an article or quiz—both popular nonfiction forms—and adds dimension and white space to the lyric essay.

3. Travel through time , like Nina Boutsikaris in “ Some Sort of Union .”

Nina Boutsikaris is the author of I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Sorry: An Intimacy Triptych , and her work has also appeared in an anthology of the best flash nonfiction. Her essay “Some Sort of Union,” published in Hippocampus Magazine , was a finalist in the magazine’s Best Creative Nonfiction contest.

Since lyric essays are typically longer and more free verse than poems, they can be a way to address a larger idea or broader time period. Boutsikaris does this in “Some Sort of Union,” where the speaker drifts from an interaction with a romantic interest to her childhood.

“They were neighbors, the girl and the air force paramedic. She could have seen his front door from her high-rise window if her window faced west rather than east,” Boutsikaris describes. “When she first met him two weeks ago, she’d been wearing all white, buying a wedge of cheap brie at the corner market.”

In the very next paragraph, Boutskiras shifts this perspective and timeline, writing, “The girl’s mother had been angry with her when she was a child. She had needed something from the girl that the girl did not know how to give. Not the way her mother hoped she would.”

As this example reveals, examining different perspectives and timelines within a lyric essay can flesh out a broader understanding of who a character is.

4. Bring in research, history, and data, like Roxane Gay in “ What Fullness Is .”

Like any other form of writing, lyric essays benefit from in-depth research. And while journalistic or scientific details can sometimes throw off the concise ecosystem and syntax of a poem, the lyric essay has room for this sprawling information.

In “What Fullness Is,” award-winning writer Roxane Gay contextualizes her own ideas and experiences with weight loss surgery through the history and culture surrounding the procedure.

“The first weight-loss surgery was performed during the 10th century, on D. Sancho, the king of León, Spain,” Gay details. “He was so fat that he lost his throne, so he was taken to Córdoba, where a doctor sewed his lips shut. Only able to drink through a straw, the former king lost enough weight after a time to return home and reclaim his kingdom.”

“The notion that thinness—and the attempt to force the fat body toward a state of culturally mandated discipline—begets great rewards is centuries old.”

Researching and knowing this history empowers Gay to make a strong central point in her essay.

Bonus prompt: Choose one of the techniques above to emulate in your own take on the lyric essay. Happy writing!

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

6 Sensitive Writing Prompts for Navigating Big Emotions

Poetry in Motion: How Dance and Rhythm Influence Verse

4 Influential Indigenous Poets to Read

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- The Lit Hub Podcast

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- I’m a Writer But

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Behind the Mic

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- Emergence Magazine

- The History of Literature

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Writing From the Margins: On the Origins and Development of the Lyric Essay

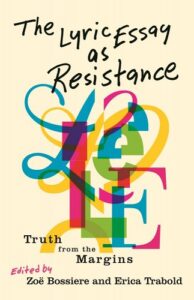

Zoë bossiere and erica trabold consider essay writing as resistance.

Once, the lyric essay did not have a name.

Or, it was called by many names. More a quality of writing than a category, the form lived for centuries in the private zuihitsu journals of Japanese court ladies, the melodic folktales told by marketplace troubadours, and the subversive prose poems penned by the European romantics.

Before I came to lyric essays, I came to writing. When my teacher asked the class to write a story for homework , I couldn’t believe my luck. But in response to my first attempt, she wrote in the margins: this is cliché .

As a first-generation college student, I was afraid I didn’t know how to tell a story properly, that my mind didn’t work that way. That I didn’t belong in a college classroom, wasn’t a real writer.

And yet, language pulled me. Alone in my dorm room, I arranged and rearranged words, whispered them aloud until the cadences pleased me, their smooth sounds like prayers. I had no name for what I was writing then, but it felt like a style I could call my own.

While the origins of the lyric essay predate its naming, the most well-known attempt to categorize the form came in 1997, when writers John D’Agata and Deborah Tall, coeditors of Seneca Review , noticed a “new” genre in the submission queue—not quite poetry, but neither quite narrative.

This form-between-forms seemed to ignore the conventions of prose writing—such as a linear chronology, narrative, and plot—in favor of embracing more liminal styles, moving by association rather than story, dancing around unspoken truths, devolving into a swirling series of digressions.

D’Agata and Tall’s proposed term for this kind of writing, “the lyric essay,” stuck, and in the ensuing decade the word would be adopted by many essayists to describe the kind of writing they do.

As a genderfluid writer and as a writing teacher, I’ve always appreciated the lyric essay as a literary beacon amid turbulent narrative waves. A means to cast light on negative space, to illuminate subjects that defy the conventions of traditional essay writing.

Introducing this writing style to students is among my favorite course units. Semester after semester, the students most drawn to the lyric essay tend to be those who enter the classroom from the margins, whose perspectives are least likely to be included on course reading lists.

Since its naming, the lyric essay has existed in an almost paradoxical space, at once celebrated for its unique characteristics while also relegated to the margins of creative nonfiction. Perhaps because of this contradiction, much of the conversation about the lyric essay—the definition of what it is and does, where it fits on the spectrum of nonfiction and poetry, whether it has a place in literary journals and in the creative writing classroom—remains unsettled, extending into the present.

I thought getting accepted into a graduate program meant I had finally opened the gilded, solid oak doors of academia—a place no one in my family, not a parent, an aunt or uncle, a sibling or cousin, had ever seen the other side of.

But at my cohort’s first meeting in a state a thousand miles from home, I understood I was still on the outside of something.

“Are you sure you write lyric essays?” the other writers asked. “What does that even mean?”

The acceptance of the lyric form seems to depend largely on who is writing it. The essays that tend to thrive in dominant-culture spaces like academia and publishing are often written by writers who already occupy those spaces. This may be part of why, despite its expansive nature, many of the most widely-anthologized, widely-read, and widely-taught lyric essays represent a narrow range of perspectives: most often, those of the center.

To name the lyric essay—to name anything—is to construct rules about what an essay called “lyric” should look like on the page, should examine in its prose, even who it should be written by. But this categorization has its uses, too.

Much like when a person openly identifies as queer , identifying an essayistic style as “lyric” provides a blueprint for others on the margins to name their experiences—a form through which to speak their truths.

The center is, by definition, a limited perspective, capable of viewing only itself.

In “Marginality as a Site of Resistance,” bell hooks positions the margins not as a state “one wishes to lose, to give up, or surrender as part of moving into the center, but rather as a site one stays on, clings to even, because it nourishes one’s capacity to resist.”

To write from the margins is to write from the perspective of the whole—to see the world from both the margins and the center.

I graduated with a manuscript of lyric essays, one that coalesced into my first book. That book went on to win a prize judged by John D’Agata and named for Deborah Tall. I had finally found my footing, unlocked that proverbial door. But skepticism followed me in.

On my book tour, I was invited to read at my alma mater alongside another writer whose nonfiction tackled pressing social issues with urgency, empathy, and wit. I read an essay about home and friendship, about being young and the hard lessons of growing up.

After the reading, we fielded a Q&A. The Dean of my former college raised his hand.

“I can see what work the other writer is doing quite clearly,” he said to me. “But what exactly is the point of yours?”

Writing is never a neutral act. Although a rallying slogan from a different era and cause, the maxim “the personal is political” still applies to the important work writers do when they speak truth to power, call attention to injustice, and advocate for social change.

Because the lyric essay is fluid, able to occupy both marginal and center spaces, it is a form uniquely suited to telling stories on the writer’s terms, without losing sight of where the writer comes from, and the audiences they are writing toward.

When we tell the stories of our lives—especially when those stories challenge assumptions about who we are—it is an act of resistance.

Many of the contemporary LGBTQIA+ essayists I teach in my classes write lyrical prose to capture queer experience on the page. Their works reckon with nonbinary family building and parenthood, the ghosts of trans Midwestern origin, coming of age in a queer Black body, the over- whelming epidemic of transmisogyny and gendered violence.

The lyric essay is an ideal container for these stories, each a unique prism reflecting the ambiguous, messy, and ever-evolving processes through which we as queer people come to understand ourselves.

Lyric essays rarely stop to provide directions, instead mapping the reader on a journey into the writer’s world, toward an unknown end. Along the way, the reader learns to interpret the signs, begins to understand that the road blocks and potholes and detours—those gaps, the words left unspoken on the page—are as important as the essay’s destination.

The lyric essays that have taught me the most as a writer never showed their full hand. Each became its own puzzle, with secrets to unlock. When the text on a page was obscured, the essay taught me to fill in the blanks. When the conflict didn’t resolve, I realized irresolution might be its truest end. When the segments of the essay seemed unconnected, I learned to read between the lines.

The most powerful lyric essays reclaim silence from the silencers, becoming a space of agency for writers whose experiences are routinely questioned, flattened, or appropriated.

Readers from the margins, those who have themselves been silenced, recognize the game.

The twenty contemporary lyric essays in this volume embody resistance through content, style, design, and form, representing of a broad spectrum of experiences that illustrate how identities can intersect, conflict, and even resist one another. Together, they provide a dynamic example of the lyric essay’s range of expression while showcasing some of the most visionary contemporary essayists writing in the form today.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Lyric Essay as Resistance: Truth from the Margins , edited by Zoë Bossiere and Erica Trabold. Copyright © 2023. Available from Wayne State University Press.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Zoë Bossiere and Erica Trabold

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Ling Ling Huang on the Similarities Between Classical Music and Fiction Writing

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Lyric Essays

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Because the lyric essay is a new, hybrid form that combines poetry with essay, this form should be taught only at the intermediate to advanced levels. Even professional essayists aren’t certain about what constitutes a lyric essay, and lyric essays disagree about what makes up the form. For example, some of the “lyric essays” in magazines like The Seneca Review have been selected for the Best American Poetry series, even though the “poems” were initially published as lyric essays.

A good way to teach the lyric essay is in conjunction with poetry (see the Purdue OWL's resource on teaching Poetry in Writing Courses ). After students learn the basics of poetry, they may be prepared to learn the lyric essay. Lyric essays are generally shorter than other essay forms, and focus more on language itself, rather than storyline. Contemporary author Sherman Alexie has written lyric essays, and to provide an example of this form, we provide an excerpt from his Captivity :

"He (my captor) gave me a biscuit, which I put in my

pocket, and not daring to eat it, buried it under a log, fear-

ing he had put something in it to make me love him.

FROM THE NARRATIVE OF MRS. MARY ROWLANDSON,

WHO WAS TAKEN CAPTIVE WHEN THE WAMPANOAG

DESTROYED LANCASTER, MASSACHUSETS, IN 1676"

"I remember your name, Mary Rowlandson. I think of you now, how necessary you have become. Can you hear me, telling this story within uneasy boundaries, changing you into a woman leaning against a wall beneath a HANDICAPPED PARKING ONLY sign, arrow pointing down directly at you? Nothing changes, neither of us knows exactly where to stand and measure the beginning of our lives. Was it 1676 or 1976 or 1776 or yesterday when the Indian held you tight in his dark arms and promised you nothing but the sound of his voice?"

Alexie provides no straightforward narrative here, as in a personal essay; in fact, each numbered section is only loosely related to the others. Alexie doesn’t look into his past, as memoirists do. Rather, his lyric essay is a response to a quote he found, and which he uses as an epigraph to his essay.

Though the narrator’s voice seems to be speaking from the present, and addressing a woman who lived centuries ago, we can’t be certain that the narrator’s voice is Alexie’s voice. Is Alexie creating a narrator or persona to ask these questions? The concept and the way it’s delivered is similar to poetry. Poets often use epigraphs to write poems. The difference is that Alexie uses prose language to explore what this epigraph means to him.

An Introduction to the Lyric Essay

An introduction to the lyric essay, how it differs from other nonfiction, and some excellent examples to get you started.

Rebecca Hussey

Rebecca holds a PhD in English and is a professor at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. She teaches courses in composition, literature, and the arts. When she’s not reading or grading papers, she’s hanging out with her husband and son and/or riding her bike and/or buying books. She can't get enough of reading and writing about books, so she writes the bookish newsletter "Reading Indie," focusing on small press books and translations. Newsletter: Reading Indie Twitter: @ofbooksandbikes

View All posts by Rebecca Hussey

Essays come in a bewildering variety of shapes and forms: they can be the five paragraph essays you wrote in school — maybe for or against gun control or on symbolism in The Great Gatsby . Essays can be personal narratives or argumentative pieces that appear on blogs or as newspaper editorials. They can be funny takes on modern life or works of literary criticism. They can even be book-length instead of short. Essays can be so many things!

Perhaps you’ve heard the term “lyric essay” and are wondering what that means. I’m here to help.

What is the Lyric Essay?

A quick definition of the term “lyric essay” is that it’s a hybrid genre that combines essay and poetry. Lyric essays are prose, but written in a manner that might remind you of reading a poem.

Before we go any further, let me step back with some more definitions. If you want to know the difference between poetry and prose, it’s simply that in poetry the line breaks matter, and in prose they don’t. That’s it! So the lyric essay is prose, meaning where the line breaks fall doesn’t matter, but it has other similarities to what you find in poems.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox. By signing up you agree to our terms of use

Lyric essays have what we call “poetic” prose. This kind of prose draws attention to its own use of language. Lyric essays set out to create certain effects with words, often, although not necessarily, aiming to create beauty. They are often condensed in the way poetry is, communicating depth and complexity in few words. Chances are, you will take your time reading them, to fully absorb what they are trying to say. They may be more suggestive than argumentative and communicate multiple meanings, maybe even contradictory ones.

Lyric essays often have lots of white space on their pages, as poems do. Sometimes they use the space of the page in creative ways, arranging chunks of text differently than regular paragraphs, or using only part of the page, for example. They sometimes include photos, drawings, documents, or other images to add to (or have some other relationship to) the meaning of the words.

Lyric essays can be about any subject. Often, they are memoiristic, but they don’t have to be. They can be philosophical or about nature or history or culture, or any combination of these things. What distinguishes them from other essays, which can also be about any subject, is their heightened attention to language. Also, they tend to deemphasize argument and carefully-researched explanations of the kind you find in expository essays . Lyric essays can argue and use research, but they are more likely to explore and suggest than explain and defend.

Now, you may be familiar with the term “ prose poem .” Even if you’re not, the term “prose poem” might sound exactly like what I’m describing here: a mix of poetry and prose. Prose poems are poetic pieces of writing without line breaks. So what is the difference between the lyric essay and the prose poem?

Honestly, I’m not sure. You could call some pieces of writing either term and both would be accurate. My sense, though, is that if you put prose and poetry on a continuum, with prose on one end and poetry on the other, and with prose poetry and the lyric essay somewhere in the middle, the prose poem would be closer to the poetry side and the lyric essay closer to the prose side.

Some pieces of writing just defy categorization, however. In the end, I think it’s best to call a work what the author wants it to be called, if it’s possible to determine what that is. If not, take your best guess.

Four Examples of the Lyric Essay

Below are some examples of my favorite lyric essays. The best way to learn about a genre is to read in it, after all, so consider giving one of these books a try!

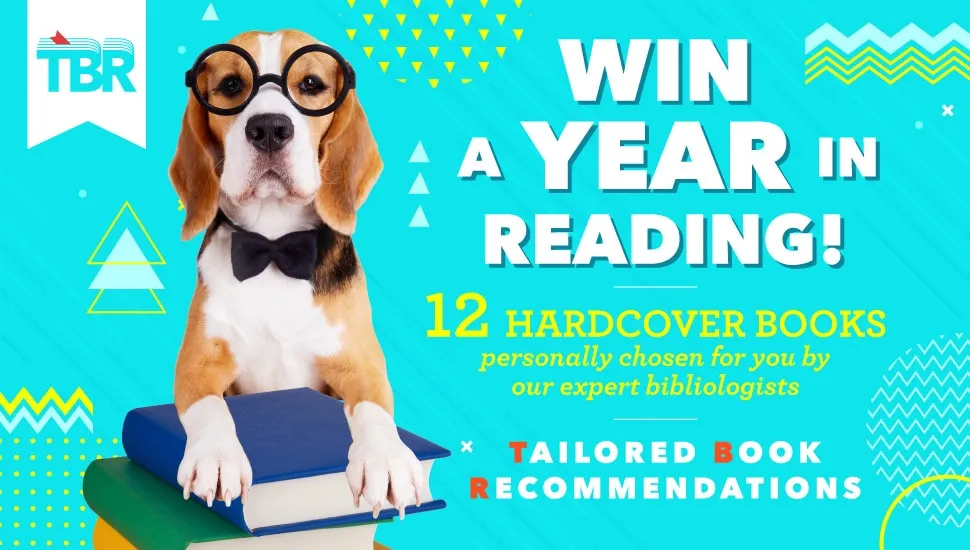

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine

Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen counts as a lyric essay, but I want to highlight her lesser-known 2004 work. In Don’t Let Me Be Lonely , Rankine explores isolation, depression, death, and violence from the perspective of post-9/11 America. It combines words and images, particularly television images, to ponder our relationship to media and culture. Rankine writes in short sections, surrounded by lots of white space, that are personal, meditative, beautiful, and achingly sad.

Calamities by Renee Gladman

Calamities is a collection of lyric essays exploring language, imagination, and the writing life. All of the pieces, up until the last 14, open with “I began the day…” and then describe what she is thinking and experiencing as a writer, teacher, thinker, and person in the world. Many of the essays are straightforward, while some become dreamlike and poetic. The last 14 essays are the “calamities” of the title. Together, the essays capture the artistic mind at work, processing experience and slowly turning it into writing.

The Self Unstable by Elisa Gabbert

The Self Unstable is a collection of short essays — or are they prose poems? — each about the length of a paragraph, one per page. Gabbert’s sentences read like aphorisms. They are short and declarative, and part of the fun of the book is thinking about how the ideas fit together. The essays are divided into sections with titles such as “The Self is Unstable: Humans & Other Animals” and “Enjoyment of Adversity: Love & Sex.” The book is sharp, surprising, and delightful.

Bluets by Maggie Nelson

Bluets is made up of short essayistic, poetic paragraphs, organized in a numbered list. Maggie Nelson’s subjects are many and include the color blue, in which she finds so much interest and meaning it will take your breath away. It’s also about suffering: she writes about a friend who became a quadriplegic after an accident, and she tells about her heartbreak after a difficult break-up. Bluets is meditative and philosophical, vulnerable and personal. It’s gorgeous, a book lovers of The Argonauts shouldn’t miss.

It’s probably no surprise that all of these books are published by small presses. Lyric essays are weird and genre-defying enough that the big publishers generally avoid them. This is just one more reason, among many, to read small presses!

If you’re looking for more essay recommendations, check out our list of 100 must-read essay collections and these 25 great essays you can read online for free .

You Might Also Like

IMAGES

VIDEO