Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

Case study of a patient with heart failure

13 Case study of a patient with heart failure Chapter aims • To provide you with an example of the nursing care that a patient with heart failure may require • To encourage you to research and deepen your knowledge of heart failure Introduction This chapter provides you with an example of the nursing care that a patient with heart failure may require. The heart failure care plan ( Fig. 13.1 ) has been written by a senior charge nurse for coronary care, Rafael Ripoll, and outlines care for the four stages of heart failure. The case history for Martha will then guide you through the assessment, nursing action and evaluation of a patient with heart failure. Fig 13.1 Heart failure care plan (Reproduced with permission of Rafael Ripoll) Activity A definition of heart failure was given in Chapter 1 and asked you to revise your anatomy and physiology (see Montague et al 2005 ). Before reading the case study, find out the following: 1. What are some of the symptoms of heart failure? 2. What health education could you provide for a patient with heart failure? You can find out the answers to these questions by following the link below. The British Heart Foundation provides free booklets to download: http://www.bhf.org.uk/heart-health/conditions/heart-failure.aspx (accessed July 2011). Patient profile Martha is a 60-year-old lady who is admitted to accident and emergency (A&E) with breathlessness – her respiratory rate is 40 per minute and her oxygen saturation is 89%. On admission, her pulse is 175 beats per minute (bpm) and irregular. Her blood pressure is 90/50 mmHg. Martha is put on high-flow oxygen, a continuous cardiac monitor, hourly observation of vital signs and an intravenous cannula is inserted. Martha is administered intravenous digoxin and furosemide in A&E and is catheterised to enable accurate fluid balance. Martha is married with three grown-up children and smokes 20 cigarettes a day. Martha is then transferred to a medical ward with a cardiac specialty. Assessment on admission Martha is breathless and on oxygen therapy 35% via the mask. She has peripheral oedema and is fluid overloaded. Furosemide is being administered intravenously. She is on stage 2 (see Fig. 13.1 ) of the heart failure care plan but is not receiving glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) due to hypotension. Martha is tachycardic and attached to a cardiac monitor which is showing atrial fibrillation between 110 and 115 bpm. Urinary output is greater than 70 mL/hour. Martha is very distressed but knows where she is and why. She is unable to eat or drink at the moment due to her breathlessness. She is a life-long smoker. She lives with her husband in a third-floor flat with a lift. She still works part time as a cleaner for a local company. Activity See Appendix 4 in Holland et al (2008) for possible questions to consider during the assessment stage of care planning. Many organisations will have a care plan pathway, and Figure 13.1 is an example of one by R. Ripoll (2005 unpublished). This is to ensure that the care of the patient is explicit and standardised. This does not mean that the care becomes less individualised. Martha’s problems Based on your assessment of Martha, the following problems should form the basis of your care plan: • Martha is breathless. • Martha is cardiovascularly unstable due to her condition. • Martha is frightened and distressed. • Martha has a urinary catheter. • Martha is unable to eat or drink adequately due to her condition. • Martha is a life-long smoker and cannot smoke in hospital. Martha’s nursing care plans 1. Problem: Martha is breathless. Goal: To restore normal breathing pattern. Nursing action Rationale Assess Martha’s breathing, respiratory rate and keep oxygen saturation > 95% Observe for signs of cyanosis Administer prescribed oxygen Inform the nurse in charge of any changes to Martha’s condition To observe for any signs of deterioration To ensure that Martha does not become hypoxic Oxygen is a drug and must be prescribed Encourage Martha to sit upright supported by pillows To maximise lung expansion and gaseous exchange To increase comfort Administer any medication as prescribed and ensure that Martha is fully informed about the medication and any side effects For example, explain to Martha why she needs to keep her oxygen mask on Martha is much more likely to comply with her medication if she understands why she needs to have it Refer Martha to the physiotherapist and liaise To maximise gaseous exchange To prevent complications from immobility To ensure consistent treatment from nurses and physiotherapists 2. Problem: Martha is cardiovascularly unstable due to her condition. Goal : To stabilise Martha. Nursing action Rationale Martha needs continuous cardiac monitoring of her condition until it has stabilised Ensure that alarm limits are set within appropriate limits Hourly observations of pulse and blood pressure Inform the nurse in charge and doctor regarding any changes in observations and discuss the frequency of observations required To detect any change in Martha’s condition as soon as possible To be able to respond to these changes and for the team to be informed To check blood urea and electolytes Abnormal potassium levels will increase the risk cardiovascular instability 3. Problem: Martha is frightened and distressed. Goal : To try to relieve Martha’s distress. Nursing action Rationale Spend time with Martha using verbal and non-verbal communication to reassure her Being alone will increase Martha’s distress Always introduce Martha to the nurse who is relieving you or taking over your shift If you need to go to another area, explain to Martha who will be looking after her Explain to Martha how the call bell system works and make sure that it is in easy reach Knowing who is looking after her will help Martha to relax Knowing where her nurse is is important as Martha will know that there is someone identified who is looking after her needs If Martha cannot see her nurse she will understand how to summon help Communicate with Martha’s family and significant others with her permisssion Family and friends may find the environment and equipment daunting Information will help them to understand about Martha’s condition Nurses should never presume that a patient wants her family to know about their condition and it is important to respect Martha’s wishes 4. Problem: Martha has a urinary catheter. Goal: To monitor fluid balance accurately and to prevent infection. Nursing action Rationale Explain to Martha why she requires urinary catheter. Hourly measurements of urine: if below 30 mL/h or above 200 mL/h, report to the nurse in charge and liaise with the doctors when reducing the frequency of the urine output measurements Document urine output on a fluid balance chart To accurately monitor Martha’s fluid balance. Martha is at risk of fluid overload due to her cardiac condition Provide catheter care and hygiene Check the colour of the urine each shift Report any changes to the nurse in charge Provide privacy when providing catheter care To prevent infection To detect any signs of infection or trauma To ensure that Martha’s privacy and dignity needs are met Monitor temperature, pulse and blood pressure and respirations four times a day while Martha has an indwelling urinary catheter Take a catheter specimen of urine for microscopy, culture and sensitivity testing if Martha’s temperature is > 37.5°C and inform the nurse/doctor To detect any infection and treat as soon as possible 5. Problem: Martha is unable to eat or drink adequately due to her condition. Goal: For Martha to have adequate fluid and dietary intake. Nursing action Rationale Ensure a malnutrition risk assessment is undertaken in the first 24 hours (see Ch. 9 ) To determine Martha’s nutritional status Maintain strict food and fluid balance monitoring Martha may be on fluid restriction Inform Martha about this and provide her with rationale Inform the nurse in charge or doctor if Martha’s diet or fluid intake are below the normal limits Due to her cardiac failure, Martha is at risk of fluid overload To ensure that Martha receives adequate fluids and nutrition To prevent complications of dehydration To ensure that there is effective communication within the multidisciplinary team Ensure that nutritional supplements are explained to Martha and encourage her to drink them To keep Martha fully informed Monitor and document observations of her vital signs (see Ch. 7 ) To detect any deterioration/improvement Administer intravenous therapy as prescribed and ensure that a cannula care plan is in place for this (see Ch. 9 ) To reduce the risk of cannula-associated infection/complications Keep Martha informed of her condition To promote and enhance communication 6. Problem: Martha is a life-long smoker and cannot smoke in hospital. Goal: To help Martha deal with any cravings or withdrawal symptoms. Nursing action Rationale To discuss with Martha how she is feeling and discuss prescribing nicotine supplements with the medical team To prevent Martha from suffering from nicotine withdrawal symptoms Once Martha is feeling better, discuss how she feels about smoking after discharge and whether she would accept a referral to the cardiac rehabilitation/heart failure team or smoking cessation team Provide verbal and written information for Martha and her husband To provide health education and promotion to Martha and her family

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- Medical placements

- Revision and future learning

- The end of the journey

- Medicines management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Heart Failure

Learn about the nursing care management of patients with heart failure.

Table of Contents

- What is Heart Failure?

Left-Sided Heart Failure

Right-sided heart failure, pathophysiology, left-sided hf, right-sided hf, complications, assessment and diagnostic findings, pharmacologic therapy, nutritional therapy, additional therapy, nursing management, what is heart failure.

Heart failure, also known as congestive heart failure, is recognized as a clinical syndrome characterized by signs and symptoms of fluid overload or of inadequate tissue perfusion .

- Heart failure is the inability of the heart to pump sufficient blood to meet the needs of the tissues for oxygen and nutrients.

- The term heart failure indicates myocardial disease in which there is a problem with contraction of the heart (systolic dysfunction) or filling of the heart (diastolic dysfunction) that may or may not cause pulmonary or systemic congestion .

- Heart failure is most often a progressive, life-long condition that is managed with lifestyle changes and medications to prevent episodes of acute decompensated heart failure.

Classification

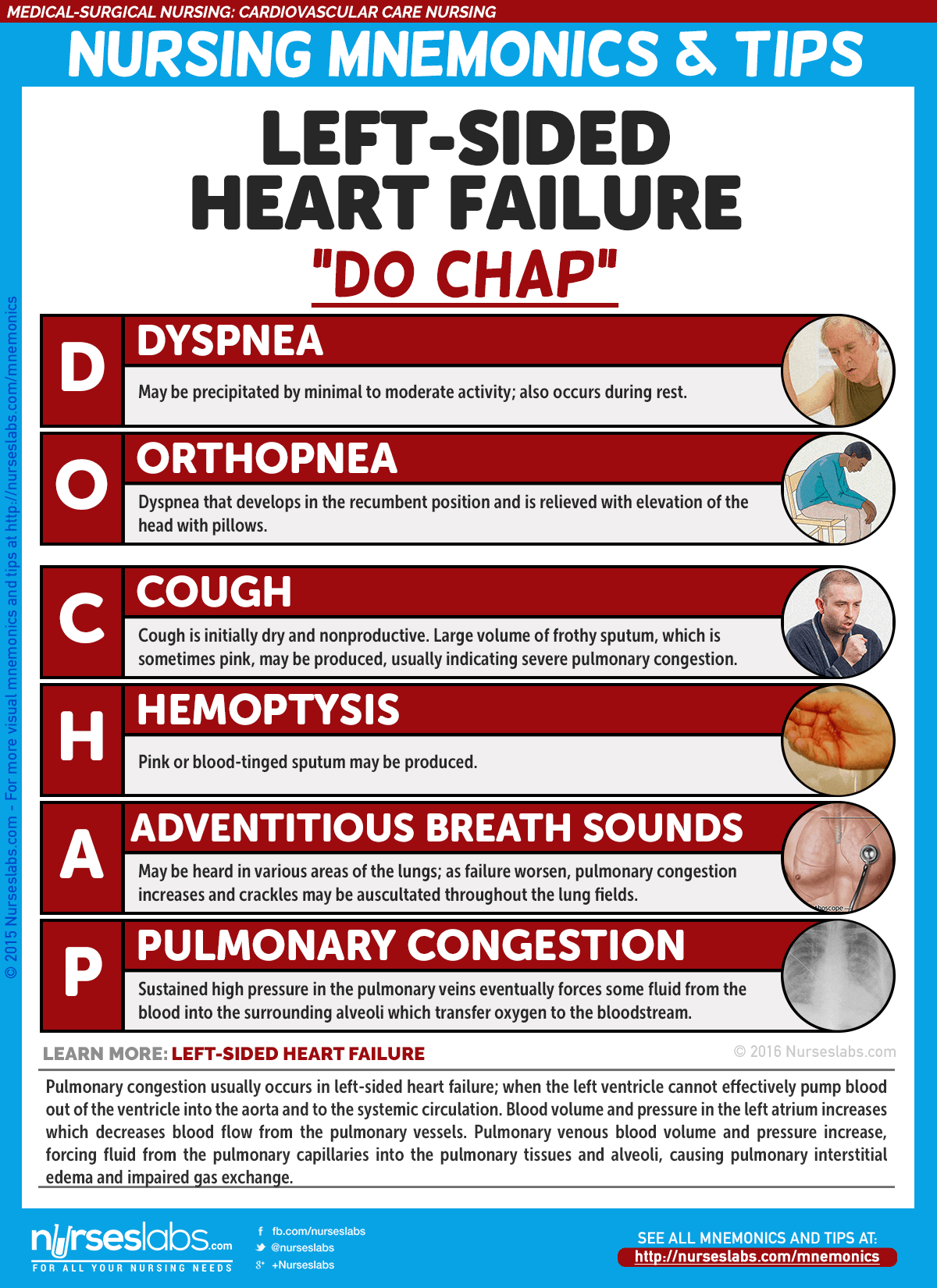

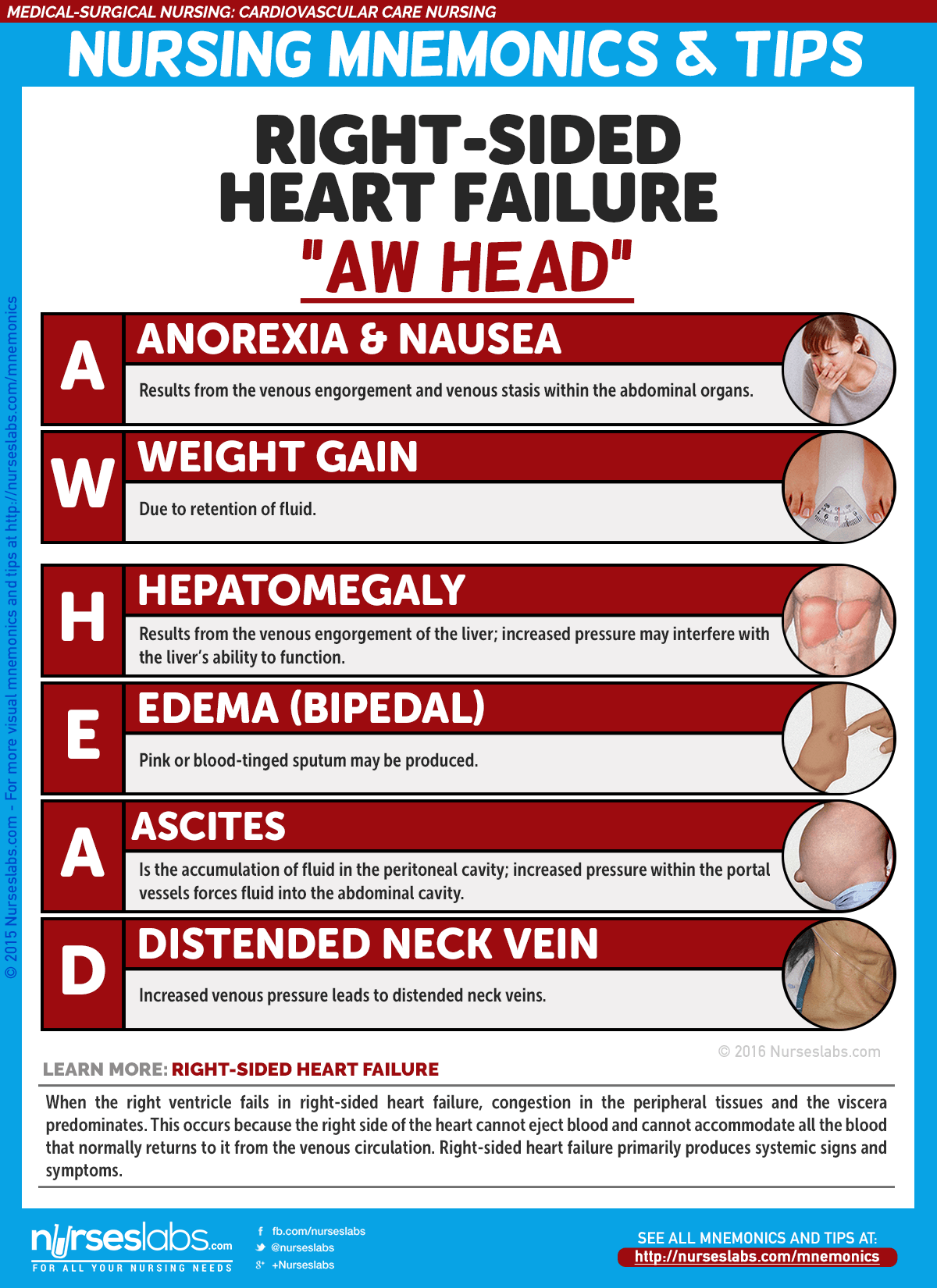

Heart failure is classified into two types: left-sided heart failure and right-sided heart failure.

- Left-sided heart failure or left ventricular failure have different manifestations with right-sided heart failure.

- Pulmonary congestion occurs when the left ventricle cannot effectively pump blood out of the ventricle into the aorta and the systemic circulation.

- Pulmonary venous blood volume and pressure increase, forcing fluid from the pulmonary capillaries into the pulmonary tissues and alveoli, causing pulmonary interstitial edema and impaired gas exchange .

- When the right ventricle fails, congestion in the peripheral tissues and the viscera predominates.

- The right side of the heart cannot eject blood and cannot accommodate all the blood that normally returns to it from the venous circulation.

- Increased venous pressure leads to JVD and increased capillary hydrostatic pressure throughout the venous system.

The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association have classifications of heart failure.

- Stage A. Patients at high risk for developing left ventricular dysfunction but without structural heart disease or symptoms of heart failure.

- Stage B. Patients with left ventricular dysfunction or structural heart disease that has not developed symptoms of heart failure.

- Stage C. Patients with left ventricular dysfunction or structural heart disease with current or prior symptoms of heart failure.

- Stage D. Patients with refractory end-stage heart failure requiring specialized interventions.

Heart failure results from a variety of cardiovascular conditions, including chronic hypertension , coronary artery disease, and valvular disease.

- As HF develops, the body activates neurohormonal compensatory mechanisms.

- Systolic HF results in decreased blood volume being ejected from the ventricle.

- The sympathetic nervous system is then stimulated to release epinephrine and norepinephrine .

- Decrease in renal perfusion causes renin release, and then promotes the formation of angiotensin I .

- Angiotensin I is converted to angiotensin II by ACE which constricts the blood vessels and stimulates aldosterone release that causes sodium and fluid retention.

- There is a reduction in the contractility of the muscle fibers of the heart as the workload increases.

- Compensation . The heart compensates for the increased workload by increasing the thickness of the heart muscle.

Just like coronary artery disease , the incidence of HF increases with age.

- More than 5 million people in the United States have HF.

- There are 550, 000 cases of HF diagnosed each year according to the American Heart Association.

- HF is most common among people older than 75 years of age .

- HF is now considered epidemic in the United States.

- HF is the most common reason for hospitalization of people older than 65 years of age.

- It is also the second most common reason for visits to the physician’s office.

- The estimated economic burden caused by HF is more than $33 billion annually in direct and indirect costs and is still expected to increase.

Heart failure can affect both women and men, although the mortality is higher among women.

- There are also racial differences; at all ages death rates are higher in African American than in non-Hispanic whites.

- Heart failure is primarily a disease of older adults, affecting 6% to 10% of those older than 65.

- It is also the leading cause of hospitalization in older people .

Systemic diseases are usually one of the most common causes of heart failure.

- Coronary artery disease . Atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries is the primary cause of HF, and coronary artery disease is found in more than 60% of the patients with HF.

- Ischemia . Ischemia deprives heart cells of oxygen and leads to acidosis from the accumulation of lactic acid.

- Cardiomyopathy . HF due to cardiomyopathy is usually chronic and progressive.

- Systemic or pulmonary hypertension . Increase in afterload results from hypertension , which increases the workload of the heart and leads to hypertrophy of myocardial muscle fibers.

- Valvular heart disease . Blood has increasing difficulty moving forward, increasing pressure within the heart and increasing cardiac workload.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations produced y the different types of HF are similar and therefore do not assist in differentiating the types of HF. The signs and symptoms can be related to the ventricle affected.

- Dyspnea or shortness of breath may be precipitated by minimal to moderate activity.

- Cough . The cough associated with left ventricular failure is initially dry and nonproductive .

- Pulmonary crackles . Bibasilar crackles are detected earlier and as it worsens, crackles can be auscultated across all lung fields.

- Low oxygen saturation levels . Oxygen saturation may decrease because of increased pulmonary pressures.

- Enlargement of the liver result from venous engorgement of the liver.

- Accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity may increase pressure on the stomach and intestines and cause gastrointestinal distress.

- Loss of appetite results from venous engorgement and venous stasis within the abdominal organs.

Prevention of heart failure mainly lies in lifestyle management.

- Healthy diet. Avoiding intake of fatty and salty foods greatly improves the cardiovascular health of an individual.

- Engaging in cardiovascular exercises thrice a week could keep the cardiovascular system up and running smoothly.

- Smoking cessation . Nicotine causes vasoconstriction that increases the pressure along the vessels.

Many potential problems associated with HF therapy relate to the use of diuretics .

- Hypokalemia . Excessive and repeated dieresis can lead to hypokalemia .

- Hyperkalemia . Hyperkalemia may occur with the use of ACE inhibitors , ARBs, or spironolactone .

- Prolonged diuretic therapy might lead to hyponatremia and result in disorientation , fatigue , apprehension, weakness , and muscle cramps.

- Dehydration and hypotension . Volume depletion from excessive fluid loss may lead to dehydration and hypotension .

HF may go undetected until the patient presents with signs and symptoms of pulmonary and peripheral edema.

- ECG : May show hypertrophy, axis deviation, ischemia , and damage patterns. Dysrhythmias and ST-T segment abnormalities may be present.

- Chest x-ray : May show enlarged cardiac shadow or abnormal contour indicating ventricular aneurysm .

- Sonograms ( echocardiography , Doppler, and transesophageal echocardiography): May reveal chamber dimensions, valvular function/structure, and ventricular dilation and dysfunction.

- Heart scan (MUGA): Measures cardiac volume, ejection fraction, and wall motion.

- Exercise or pharmacological stress myocardial perfusion: Determines presence of myocardial ischemia and wall motion abnormalities.

- PET scan: Sensitive test for evaluating myocardial ischemia and viability.

- Cardiac catheterization : Assesses pressures, differentiates right- versus left-sided heart failure, and evaluates coronary artery patency.

- Liver enzymes: Elevated in liver congestion/failure.

- Digoxin and other cardiac drug levels: Determines therapeutic range.

- Bleeding and clotting times: Identifies clotting risks and therapeutic range.

- Electrolytes: May be altered due to fluid shifts, renal function, or diuretic therapy.

- Pulse oximetry: Measures oxygen saturation , especially in conjunction with COPD or chronic HF.

- Arterial blood gases ( ABGs ): Reflects respiratory and acid-base status.

- BUN/ creatinine : Evaluates renal perfusion and function.

- Serum albumin/transferrin: Indicates protein intake and liver function.

- Complete blood count (CBC): Assesses for anemia , polycythemia, and dilutional changes.

- ESR: Evaluates acute inflammatory reaction.

- Thyroid studies: Determines thyroid activity as a potential precipitator of HF.

Medical Management

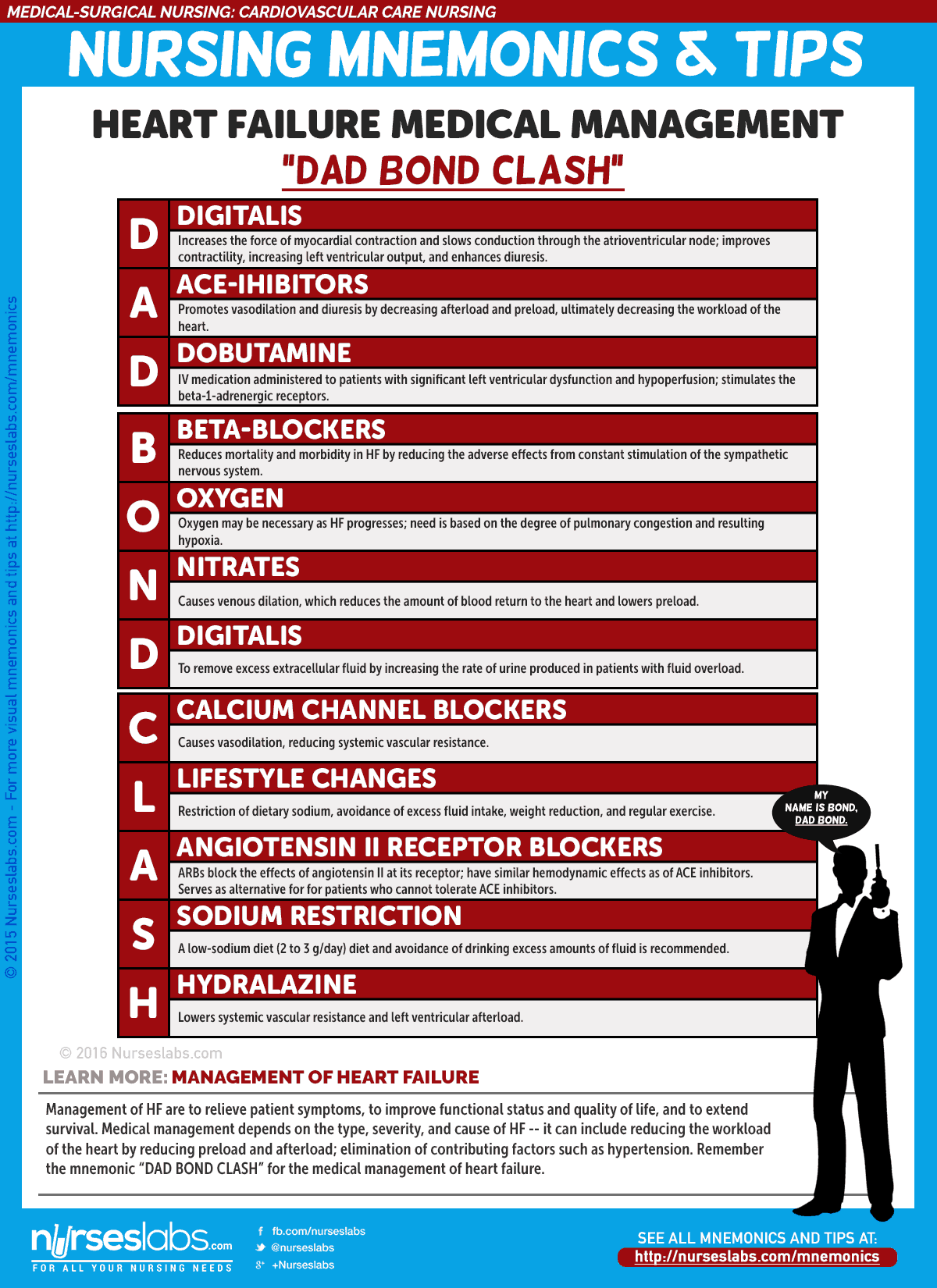

The overall goals of management of HF are to relieve patient symptoms, to improve functional status and quality of life, and to extend survival.

- ACE Inhibitors . ACE inhibitors slow the progression of HF, improve exercise tolerance, decrease the number of hospitalizations for HF, and promote vasodilation and diuresis by decreasing afterload and preload .

- Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers . ARBs block the conversion of angiotensin I at the angiotensin II receptor and cause decreased blood pressure , decreased systemic vascular resistance, and improved cardiac output.

- Beta Blockers . Beta blockers reduce the adverse effects from the constant stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system.

- Diuretics . Diuretics are prescribed to remove excess extracellular fluid by increasing the rate of urine produced in patients with signs and symptoms of fluid overload .

- Calcium Channel Blockers . CCBs cause vasodilation , reducing systemic vascular resistance but contraindicated in patients with systolic HF.

- Sodium restriction . A low sodium diet of 2 to 3g/day reduces fluid retention and the symptoms of peripheral and pulmonary congestion, and decrease the amount of circulating blood volume, which decreases myocardial work.

- Patient compliance . Patient compliance is important because dietary indiscretions may result in severe exacerbations of HF requiring hospitalizations.

- Supplemental Oxygen . The need for supplemental oxygen is based on the degree of pulmonary congestion and resulting hypoxia.

- Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. CRT involves the use of a biventricular pacemaker to treat electrical conduction defects.

- Ultrafiltration . Ultrafiltration is an alternative intervention for patients with severe fluid overload.

- Cardiac Transplant . For some patients with end-stage heart failure, cardiac transplant is the only option for long term survival.

Despite advances in the treatment of HF, morbidity and mortality remains high. Nurses have a major impact on outcomes for patients with HF.

For a more comprehensive nursing care management, please visit 18 Heart Failure Nursing Care Plans

Posts related to Heart Failure:

- Myocardial Infarction and Heart Failure NCLEX Practice Quiz (70 Items)

- 16+ Heart Failure Nursing Care Plans

- 7 Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack) Nursing Care Plans

5 thoughts on “Heart Failure”

Great work and keep it up to help nurses. Can you do an app for it on play store or IOS so that we can easily assess it anywhere at any time like medscape did

THANK YOU FOR YOUR WORK, IT HELP US AS NURSES TO BE UPDATED.

Great work keep it up sir. Almighty God blessing you in everything of life.

This is an excellent resource for nurses! However, I think nurses would benefit from an update in the medication section to include angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI: sacubitril/valsartan), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs: spironolactone, eplerenone), and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2I: dapagliflozin, empagliflozin). The 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guidelines for Heart Failure Management recommends quadruple therapy (ARNI, BB, MRA, SGLT2I) up-titrated to target or maximally tolerated doses for patients diagnosed with heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction to reverse, stabilize, or slow disease progression. These medications are also used in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction.

Hi Keysha, thank you for sharing this. I’ll add your suggestions and the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guidelines on our next update for this care plan.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Congestive heart failure (nursing).

Ahmad Malik ; Daniel Brito ; Sarosh Vaqar ; Lovely Chhabra ; Chaddie Doerr .

Affiliations

Last Update: November 5, 2023 .

- Learning Outcome

- Understand the clinical signs and symptoms of heart failure

- Understand the pathophysiology of heart failure

- Review the lifestyle modifications recommended for patients with heart failure

- Introduction

Heart failure is a common and complex clinical syndrome that results from any functional or structural heart disorder, impairing ventricular filling or ejection of blood to the systemic circulation to meet the body's needs. Heart failure can be caused by several different diseases. Most patients with heart failure have symptoms due to impaired left ventricular myocardial function. Patients usually present with dyspnea, fatigue, decreased exercise tolerance, and fluid retention, seen as pulmonary and peripheral edema. [1]

Heart failure due to left ventricular dysfunction is categorized according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) into heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (LVEF 40% or less), known as HFrEF, and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (LVEF greater than 40%); known as HFpEF. [2]

- Nursing Diagnosis

- Decreased cardiac output

- Activity intolerance

- Excess fluid volume

- Risk for impaired skin integrity

- Ineffective tissue perfusion

- Ineffective breathing pattern

- Impaired gas exchange

Heart failure is caused by several disorders, including diseases affecting the pericardium, myocardium, endocardium, cardiac valves, vasculature, or metabolism. The most common causes of systolic dysfunction (HFrEF) are idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), coronary heart disease (ischemic), hypertension, and valvular disease. For diastolic dysfunction (HFpEF), similar conditions have been described as common causes, adding hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy and restrictive cardiomyopathy. [1]

- Risk Factors

- Coronary artery disease

- Myocardial infarction

- Hypertension

- Alcohol use disorder

- Atrial fibrillation

- Thyroid diseases

- Congenital heart disease

- Aortic stenosis

Symptoms of heart failure include those due to excess fluid accumulation (dyspnea, orthopnea, edema, pain from hepatic congestion, and abdominal distention from ascites) and those due to a reduction in cardiac output (fatigue, weakness) most pronounced with physical exertion. [1]

Acute and subacute presentations (days to weeks) are characterized by shortness of breath at rest and/or with exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and right upper quadrant discomfort due to acute hepatic congestion (right heart failure). Palpitations, with or without lightheadedness, can occur if patients develop atrial or ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

Chronic presentations (months) differ in that fatigue, anorexia, abdominal distension, and peripheral edema may be more pronounced than dyspnea. The anorexia is secondary to several factors, including poor perfusion of the splanchnic circulation, bowel edema, and nausea induced by hepatic congestion. [1]

Characteristic features:

- Pulsus alternans phenomenon characterized by evenly spaced alternating strong and weak peripheral pulses.

- Apical impulse: Laterally displaced past the midclavicular line, usually indicative of left ventricular enlargement.

- S3 gallop: A low-frequency, brief vibration occurring in early diastole at the end of the rapid diastolic filling period of the right or left ventricle. It is the most sensitive indicator of ventricular dysfunction.

- Peripheral edema

- Pulmonary rales

New York Heart Association Functional Classification [3]

Based on symptoms, the patients can be classified using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification as follows:

- Class I: Symptom onset with more than ordinary level of activity

- Class II: Symptom onset with an ordinary level of activity

- Class III: Symptom onset with minimal activity

- Class IV: Symptoms at rest

Tests used in the evaluation of patients with HF include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): Important for identifying evidence of acute or prior myocardial infarction or acute ischemia, rhythm abnormalities, such as atrial fibrillation.

- Chest x-ray: Characteristic findings are cardiac-to-thoracic width ratio above 50%, cephalization of the pulmonary vessels, Kerley B-lines, and pleural effusions.

- Blood test: Cardiac troponin (T or I), complete blood count, serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, liver function test, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). BNP (or NT-proBNP) level adds greater diagnostic value to the history and physical examination than other initial tests mentioned above.

- Transthoracic echocardiogram: To determine ventricular function and hemodynamics.

- Medical Management

Diuretics, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, hydralazine plus nitrate, digoxin, and aldosterone antagonists can produce an improvement in symptoms and are indicated for patients with HF based on their functional classification and severity of symptoms. Combination therapy with these agents improves outcomes and reduces hospitalizations in patients with HF. [3]

Improved patient survival has been documented with the use of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, hydralazine plus nitrate, and aldosterone antagonists. More limited evidence of survival benefit is available for diuretic therapy. Diuretic therapy is mainly used for symptom control. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors should not be given within 36 hrs of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors dose. [3]

In African-Americans, hydralazine plus oral nitrate is indicated in patients with persistent NYHA class III to IV HF and LVEF less than 40%, despite optimal medical therapy (beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB, aldosterone antagonist (if indicated), and diuretics. [3]

Device therapy: Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is used for primary or secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death. Cardiac resynchronization therapy with biventricular pacing can improve symptoms and survival in selected patients who are in sinus rhythm and have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and a prolonged QRS duration. Most patients who satisfy the criteria for cardiac resynchronization therapy implantation are also candidates for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and receive a combined device. [3]

A ventricular assist device (bridge to transplant or as a destination therapy) or cardiac transplant is reserved for those with severe disease despite all other measures.

- Nursing Management

The nursing care plan for patients with HF should include: [4]

- Relieving fluid overload symptoms

- Relieving symptoms of anxiety and fatigue

- Promoting physical activity

- Increasing medication compliance

- Decreasing adverse effects of treatment

- Teaching patients about dietary restrictions

- Teaching patient about self-monitoring of symptoms

- Teaching patients about daily weight monitoring

- When To Seek Help

Prompt assessment by the medical team is indicated in the following situations:

- Worsening symptoms of fluid overload

- Worsening hypoxia

- Uncontrolled tachycardia regardless of the rhythm

- Change in cardiac rhythm

- Change in mental status

- Decreased urinary output despite diuretic therapy

Patients with HF require frequent monitoring of vital signs, including oxygen saturation. They may also require constant monitoring of the heart rate and rhythm via telemetry monitoring. Frequent assessment and monitoring for symptoms is also indicated. All patients with HF require daily weight monitoring.

- Coordination of Care

Heart failure is a serious disorder best managed by an interprofessional team that includes the primary care physician, emergency department physician, cardiologist, radiologist, cardiac nurses, internist, and cardiac surgeons. It is imperative to treat the cause of heart failure. Healthcare workers who look after these patients must be familiar with current guidelines on treatment. The risk factors for heart disease must be modified, and the clinical nurse should educate the patient on the importance of medication compliance and lifestyle modifications. When the condition is not managed appropriately, it is associated with high morbidity and mortality, including poor quality of life. [5]

- Health Teaching and Health Promotion

Nursing care plans for patients with HF must include patient education to improve clinical outcomes and reduce hospital readmissions. Patients need education and guidance on self-monitoring of symptoms at home, medication compliance, daily weight monitoring, dietary sodium restriction to 2 to 3 g/day, and daily fluid restriction to 2 L/day. In addition, patients with HF need aggressive treatment for underlying risk factors and the potential triggers for HF exacerbations. Modifiable risk factors include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, nicotine use, alcohol use disorder, and recreational drug use, especially cocaine. Patients with sleep apnea and HF should be encouraged to use continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy as uncontrolled sleep apnea can also increase HF-associated morbidity and mortality.

- Discharge Planning

Discharge planning for patients with HF must include patient education on medication management, medication compliance, low-sodium diet, fluid restriction, activity and exercise recommendations, smoking cessation, and learning to recognize the signs and symptoms of worsening HF. Discharge planning for patients with HF must also include follow-up appointments to ensure patients have a close medical follow-up after discharge. Nurse-driven education at the time of discharge has been shown to improve compliance with therapy and improve patient outcomes in heart failure. [6]

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Congestive Heart Failure Contributed by S Bhimji, MD

Disclosure: Ahmad Malik declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Daniel Brito declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Sarosh Vaqar declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Lovely Chhabra declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Chaddie Doerr declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Malik A, Brito D, Vaqar S, et al. Congestive Heart Failure (Nursing) [Updated 2023 Nov 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF). [StatPearls. 2024] Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF). Golla MSG, Shams P. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Heart Failure and Midrange Ejection Fraction: Implications of Recovered Ejection Fraction for Exercise Tolerance and Outcomes. [Circ Heart Fail. 2016] Heart Failure and Midrange Ejection Fraction: Implications of Recovered Ejection Fraction for Exercise Tolerance and Outcomes. Nadruz W Jr, West E, Santos M, Skali H, Groarke JD, Forman DE, Shah AM. Circ Heart Fail. 2016 Apr; 9(4):e002826.

- [Clinical characteristics of heart failure with recovered ejection fraction]. [Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za ...] [Clinical characteristics of heart failure with recovered ejection fraction]. Luo Y, Chai K, Cheng YL, Zhu WR, Li YY, Wang H, Yang JF. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2021 Apr 24; 49(4):333-339.

- Review [Heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction]. [Praxis (Bern 1994). 2013] Review [Heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction]. Maeder MT, Rickli H. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2013 Oct 16; 102(21):1299-307.

- Review Breakthroughs in the treatment of heart failure with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction. [Clin Cardiol. 2022] Review Breakthroughs in the treatment of heart failure with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Talha KM, Butler J. Clin Cardiol. 2022 Jun; 45 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S31-S39.

Recent Activity

- Congestive Heart Failure (Nursing) - StatPearls Congestive Heart Failure (Nursing) - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 5: 10 Real Cases on Acute Heart Failure Syndrome: Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up

Swathi Roy; Gayathri Kamalakkannan

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case review, case discussion.

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Case 1: Diagnosis and Management of New-Onset Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction

A 54-year-old woman presented to the telemetry floor with shortness of breath (SOB) for 4 months that progressed to an extent that she was unable to perform daily activities. She also used 3 pillows to sleep and often woke up from sleep due to difficulty catching her breath. Her medical history included hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and history of triple bypass surgery 4 years ago. Her current home medications included aspirin, atorvastatin, amlodipine, and metformin. No significant social or family history was noted. Her vital signs were stable. Physical examination showed bilateral diffuse crackles in lungs, elevated jugular venous pressure, and 2+ pitting lower extremity edema. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with left ventricular hypertrophy. Chest x-ray showed vascular congestion. Laboratory results showed a pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP) level of 874 pg/mL and troponin level of 0.22 ng/mL. Thyroid panel was normal. An echocardiogram demonstrated systolic dysfunction, mild mitral regurgitation, a dilated left atrium, and an ejection fraction (EF) of 33%. How would you manage this case?

In this case, a patient with known history of coronary artery disease presented with worsening of shortness of breath with lower extremity edema and jugular venous distension along with crackles in the lung. The sign and symptoms along with labs and imaging findings point to diagnosis of heart failure with reduced EF (HFrEF). She should be treated with diuretics and guideline-directed medical therapy for congestive heart failure (CHF). Telemetry monitoring for arrythmia should be performed, especially with structural heart disease. Electrolyte and urine output monitoring should be continued.

In the initial evaluation of patients who present with signs and symptoms of heart failure, pro-BNP level measurement may be used as both a diagnostic and prognostic tool. Based on left ventricular EF (LVEF), heart failure is classified into heart failure with preserved EF (HFpEF) if LVEF is >50%, HFrEF if LVEF is <40%, and heart failure with mid-range EF (HFmEF) if LVEF is 40% to 50%. All patients with symptomatic heart failure should be started on an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (or angiotensin receptor blocker if ACE inhibitor is not tolerated) and β-blocker, as appropriate. In addition, in patients with New York Heart Association functional classes II through IV, an aldosterone antagonist should be prescribed. In African American patients, hydralazine and nitrates should be added. Recent recommendations also recommend starting an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) in patients who are symptomatic on ACE inhibitors.

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

NurseStudy.Net

Nursing Education Site

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) Nursing Diagnosis and Care Plan

Last updated on February 20th, 2023 at 08:45 am

CHF can affect either both sides of the heart or just one side. The three types of CHF are biventricular, left-sided, and right-sided heart failure. In left-sided heart failure, the left ventricle becomes enlarged (hypertrophy) and becomes dilated together with the left atrium in order to compensate for the increased pressure.

Right-sided heart failure usually happens after left-sided heart failure. Pooling of blood in the left heart chambers causes an increase in pressure, impairing the normal blood drainage from the lungs to the left atrium.

The pressure in the pulmonary veins increases, causing the right ventricle to compensate by pumping more vigorously.

In time, the cardiac muscles of the right chambers wear down, causing right-sided heart failure. Failure of both sides of the heart is called biventricular heart failure.

Congestion is one of the common features of heart failure, thus the term “congestive heart failure” is still used by many medical professionals.

Signs and Symptoms of Heart Failure

- Dyspnea ( shortness of breath ) upon exertion or lying down

- Jugular vein distention (JVD)

- Fatigue and reduced ability to exercise

- Peripheral edema (swelling of limbs, ankles, and feet)

- Pulmonary edema

- Ascites (swelling of the abdominal cavity)

- Irregular and/or rapid heartbeat

- Cough and wheezing – may come with white or blood-tinged sputum

- Nausea and lack of appetite

- Decreased level of alertness and concentration

- Increased urinary frequency at night

- Chest pain if the HF is caused by myocardial infarction (heart attack)

Causes of Heart Failure

- Myocardial Infarction (heart attack) and Coronary Artery Disease (CAD). These are the most common causes of heart failure. Fat buildup on the arterial walls leads to the reduction of blood flow, resulting to cardiac arrest.

- Hypertension . Having a high blood pressure causes the heart to work harder than normal in order to facilitate the blood circulation throughout the body. This makes the cardiac muscles stiffer and/or weaker, leading to heart failure.

- Alcohol, tobacco, and drug abuse. The toxic effects of alcohol, nicotine, and drugs (e.g. cocaine) may lead to the damage of the cardiac muscles known as cardiomyopathy .

- Congenital heart defects. Faulty heart chambers or valves at birth can directly affect the functionality of the heart.

- Other heart conditions. Viral infections such as COVID-19 may cause inflammation of the cardiac muscles known as myocarditis .

- Chronic diseases. HIV , diabetes , arrythmias, and thyroid problems may lead to heart failure.

- Certain medications. Non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) , several anaesthesia drugs, chemotherapy agents, and some antihypertensives puts a person at a higher risk for heart problems which may eventually lead to heart failure.

Complications of Heart Failure

- Kidney damage. A reduction of blood flow from the heart to the kidneys may result to reduce capacity of the kidneys to remove toxic waste. If left untreated, this may lead to kidney failure which may require the patient to undergo dialysis .

- Liver damage. Fluid build up may result to an increased pressure to the liver . If left untreated, this may result to liver damage known as scarring.

- Other cardiac issues. Heart failure may result to faulty heart valves and arrythmias if there is an increased pressure in the heart or enlargement of the heart.

Diagnostic Tests for Heart Failure

- Physical examination – crackles heard upon auscultation, signs of edema upon inspection

- Blood tests – CBC, biochemistry, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP)

- Imaging – Chest X-Ray, Echocardiogram, CT scan, MRI, coronary angiogram (insertion of a catheter and injecting a dye for visualization)

- Electrocardiogram

- Stress test – letting the patient walk on a treadmill while attached to an ECG machine

- Myocardial biopsy – insertion of a biopsy cord in a vein in the neck or groin to take heart muscle tissue samples

Treatment for Heart Failure

- Medications. Several medications are used in combination to treat heart failure. These include:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme ( ACE ) inhibitors – promotes vasodilation of the blood vessels, lowering the pressure and improving the blood flow (e.g. lisinopril and enalapril).

- Beta blockers – reduces heart rate and blood pressure (e.g. bisoprolol and carvedilol).

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers – similar to ACE inhibitors and can be used if the patient does not tolerate ACE inhibitors (e.g. losartan and valsartan).

- Digitalis or digoxin – improves the contraction of heart muscles, regulate heart rhythm and reduces heartbeat.

- Inotropes – to improve the function of the heart to pump blood in severe heart failure.

- Diuretics – to facilitate elimination of excess fluid in the body through urination (e.g. furosemide and spironolactone).

- Inotropes. These are intravenous medications used in people with severe heart failure in the hospital to improve heart pumping function and maintain blood pressure.

2. Surgical interventions. These include coronary bypass surgery, heart valve repair or replacement, and heart transplant. It may also involve the insertion of medical devices such as implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), and ventricular assist devices (VADs).

3. Lifestyle changes. A crucial part of the treatment plan for a patient with heart failure is to change several habits that are linked to the disease. These include smoking cessation, blood pressure control, diabetes management, dietary changes, stress management, exercise and increase in physical activity.

CHF Nursing Diagnosis

Chf nursing care plan 1.

Nursing Diagnosis: Decreased Cardiac Output related to increased preload and afterload and impaired contractility as evidenced by irregular heartbeat, heart rate of 128, dyspnea upon exertion, and fatigue.

Desired outcome: The patient will be able to maintain adequate cardiac output.

CHF Nursing Care Plan 2

Nursing Diagnosis: Impaired Gas Exchange related to alveolar edema due to elevated ventricular pressures as evidenced by shortness of breath, SpO2 level of 85%, and crackles upon auscultation.

Desired Outcome: The patient will have improved oxygenation and will not show any signs of respiratory distress.

CHF Nursing Care Plan 3

Nursing Diagnosis: Deficient Knowledge related to new diagnosis of Congestive Heart Failure as evidenced by patient’s verbalization of “I want to know more about my new diagnosis and care”

Desired Outcome: At the end of the health teaching session, the patient will be able to demonstrate sufficient knowledge of congestive heart failure and its management.

CHF Nursing Care Plan 4

Nursing Diagnosis: Activity intolerance related to imbalance between oxygen supply and demand as evidenced by fatigue, overwhelming lack of energy, verbalization of tiredness, generalized weakness, and shortness of breath upon exertion

Desired Outcome: The patient will demonstration active participation in necessary and desired activities and demonstrate increase in activity levels.

CHF Nursing Care Plan 5

Nursing Diagnosis: Excess Fluid Volume related to decreased cardiac output and increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as evidenced by S3 heart sound, blood pressure level of 190/85, orthopnea, pitting edema of the ankles, and weight gain

Desired Outcome: The patient will demonstrate a balanced input and output, and stabilized fluid volume

CHF Nursing Care Plan 6

Nursing Diagnosis: Acute Pain related to decreased myocardial blood flow as evidenced by pain score of 10 out of 10, verbalization of pressure-like/ squeezing chest pain (angina), guarding sign on the chest, blood pressure level of 180/90, respiratory rate of 29 cpm, and restlessness

Desired Outcome: The patient will demonstrate relief of pain as evidenced by a pain score of 0 out of 10, stable vital signs, and absence of restlessness.

CHF Nursing Care Plan 7

Nursing Diagnosis: Ineffective Breathing Pattern related to pulmonary congestion secondary to CHF as evidenced by shortness of breath, SpO2 level of 85%, cough, respiratory rate of 25 bpm, and frothy sputum

Desired Outcome: The patient will achieve effective breathing pattern as evidenced by normal respiratory rate, oxygen saturation within target range, and verbalize ease of breathing.

With proper use of the nursing process, a patient can benefit from various nursing interventions to assess, monitor, and manage heart failure and promote client safety and wellbeing.

Nursing References

Ackley, B. J., Ladwig, G. B., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M. R., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnoses handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Gulanick, M., & Myers, J. L. (2022). Nursing care plans: Diagnoses, interventions, & outcomes . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Ignatavicius, D. D., Workman, M. L., Rebar, C. R., & Heimgartner, N. M. (2018). Medical-surgical nursing: Concepts for interprofessional collaborative care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Silvestri, L. A. (2020). Saunders comprehensive review for the NCLEX-RN examination . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Disclaimer:

Please follow your facilities guidelines, policies, and procedures.

The medical information on this site is provided as an information resource only and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes.

This information is intended to be nursing education and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment.

Anna Curran. RN, BSN, PHN

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5: Case Study #4- Heart Failure (HF)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 9899

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

- 5.1: Learning Objectives

- 5.2: Patient- Meryl Smith

- 5.3: In the Supermarket

- 5.4: Emergency Room

- 5.5: Day 0- Medical Ward

- 5.6: Day 1- Medical Ward

- 5.7: Day 2- Medical Ward

- 5.8: Day 3- Medical Ward

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Book Title: Nursing Case Studies by and for Student Nurses

Author: jaimehannans

Book Information

Nursing Case Studies by and for Student Nurses Copyright © by jaimehannans is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Heart Failure Case Study (45 min)

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

What initial nursing assessments need to be performed for Mr. Jones?

- Full set vital signs

- Heart sounds

- Lung Sounds

What diagnostic tests do you anticipate being ordered by the provider?

- Chest X-ray

- 12-lead EKG

- Echocardiogram

- Cardiac Enzymes

Upon further assessment, the patient has crackles bilaterally and tachycardia. A chest X-ray shows cardiomegaly and bilateral pulmonary edema. An ECG revealed atrial fibrillation. His vital signs were as follows:

BP 150/72 mmHg Urine Yellow and Cloudy

HR 102-123 bpm and irregular BUN 17 mg/dL

RR 24-32 bpm Cr 1.2 mg/dL

Temp 37.3°C H/H 11.8 g/dL / 36.2%

Ht 175 cm LDH 705 U/L

Wt 79 kg ** BNP 843 pg/mL

Mr. Jones was admitted to the cardiac telemetry unit.

Mr. Jones states that this weight is approximately 3 kg more than it was 3 days ago.

What is the significance of Mr. Jones' weight gain?

- 1 kg weight gain is equal to 1 liter of weight gain. This means Mr. Jones has gained 3 liters of fluid (as volume excess) in just 3 days.

- This likely means that there is a new onset or exacerbation of heart failure

What medications do you anticipate the provider ordering for Mr. Jones? Why?

- Diuretics – he is volume overloaded and it is affected his lungs. Diuretics can help relieve fluid retention by promoting excretion of water from the kidneys.

- Beta-Blockers – his blood pressure is high and his heart rate is fast. The beta-blocker can help slow this down and relieve some of the workload of his heart

About three hours after admission to the telemetry unit, Mr. Jones’s skin becomes cool and clammy. His respirations are labored and he is complaining of abdominal pain. Upon physical examination, Mr. Jones is diaphoretic and gasping for air, with jugular venous distension, bilateral crackles, and an expiratory wheeze. His SpO 2 is 88% on room air and it was noted that his urine output had been approximately 20 mL/hr since admission. His BP is 190/100 mmHg, HR 130 bpm and irregular, RR 43 bpm.

What nursing interventions should you perform right away for Mr. Jones?

- Place into High Fowler’s position

- Apply oxygen

- Administer any PRN medications available for blood pressure (like hydralazine or metoprolol) if criteria are met

- Notify the provider

Describe what is happening to Mr. Jones physiologically.

- Because his heart cannot pump blood efficiently to the body, the blood is backing up into the lungs. This causes pulmonary edema. His pulmonary edema is so severe that he is struggling to breathe and struggling to oxygenate appropriately.

- His heart is trying to work extra hard to compensate for the low cardiac output, that’s why his blood pressure and heart rate are so elevated. This is perpetuated by the RAAS.

- We also see that his kidneys are not being perfused as his urine output has decreased

What medications should be given to decrease Mr. Jones’s preload? Improve his contractility? Decrease his afterload?

- Preload – diuretics (furosemide, bumetanide, spironolactione), ACE inhibitors (captopril, enalapril), ARB’s (losartan, valsartan), ARNI’s (sacubitril/valsartan)

- Contractility – Inotropes (dobutamine), cardiac glycosides (digoxin)

- Afterload – Beta Blockers (metoprolol, carvedilol), vasodilators (hydralazine, nitrates)

What is the expected outcome of administration of Furosemide? Digoxin?

- Furosemide – should see increase in urine output and decrease in respiratory symptoms – may also see a decrease in any peripheral edema

- Digoxin – decrease heart rate and increase the force of contraction – should see evidence of improved peripheral perfusion.

Melander, S. (2004). Case studies in critical care nursing: A guide for application and review, 3 rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier.

View the full outline.

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

Nursing Case Studies

- Open access

- Published: 22 May 2024

Preparedness for a first clinical placement in nursing: a descriptive qualitative study

- Philippa H. M. Marriott 1 ,

- Jennifer M. Weller-Newton 2 nAff3 &

- Katharine J. Reid 4

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 345 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

255 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

A first clinical placement for nursing students is a challenging period involving translation of theoretical knowledge and development of an identity within the healthcare setting; it is often a time of emotional vulnerability. It can be a pivotal moment for ambivalent nursing students to decide whether to continue their professional training. To date, student expectations prior to their first clinical placement have been explored in advance of the experience or gathered following the placement experience. However, there is a significant gap in understanding how nursing students’ perspectives about their first clinical placement might change or remain consistent following their placement experiences. Thus, the study aimed to explore first-year nursing students’ emotional responses towards and perceptions of their preparedness for their first clinical placement and to examine whether initial perceptions remain consistent or change during the placement experience.

The research utilised a pre-post qualitative descriptive design. Six focus groups were undertaken before the first clinical placement (with up to four participants in each group) and follow-up individual interviews ( n = 10) were undertaken towards the end of the first clinical placement with first-year entry-to-practice postgraduate nursing students. Data were analysed thematically.

Three main themes emerged: (1) adjusting and managing a raft of feelings, encapsulating participants’ feelings about learning in a new environment and progressing from academia to clinical practice; (2) sinking or swimming, comprising students’ expectations before their first clinical placement and how these perceptions are altered through their clinical placement experience; and (3) navigating placement, describing relationships between healthcare staff, patients, and peers.

Conclusions

This unique study of first-year postgraduate entry-to-practice nursing students’ perspectives of their first clinical placement adds to the extant knowledge. By examining student experience prior to and during their first clinical placement experience, it is possible to explore the consistency and change in students’ narratives over the course of an impactful experience. Researching the narratives of nursing students embarking on their first clinical placement provides tertiary education institutions with insights into preparing students for this critical experience.

Peer Review reports

First clinical placements enable nursing students to develop their professional identity through initial socialisation, and where successful, first clinical placement experiences can motivate nursing students to persist with their studies [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Where the transition from the tertiary environment to learning in the healthcare workplace is turbulent, it may impact nursing students’ learning, their confidence and potentially increase attrition rates from educational programs [ 2 , 5 , 6 ]. Attrition from preregistration nursing courses is a global concern, with the COVID-19 pandemic further straining the nursing workforce; thus, the supply of nursing professionals is unlikely to meet demand [ 7 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic has also impacted nursing education, with student nurses augmenting the diminishing nursing workforce [ 7 , 8 ].

The first clinical placement often triggers immense anxiety and fear for nursing students [ 9 , 10 ]. Research suggests that among nursing students, anxiety arises from perceived knowledge deficiencies, role ambiguity, the working environment, caring for ‘real’ people, potentially causing harm, exposure to nudity and death, and ‘not fitting in’ [ 2 , 3 , 11 ]. These stressors are reported internationally and often relate to inadequate preparation for entering the clinical environment [ 2 , 10 , 12 ]. Previous research suggests that high anxiety before the first clinical placement can be related to factors likely to affect patient outcomes, such as self-confidence and efficacy [ 13 ]. High anxiety during clinical placement may impair students’ capacity to learn, thus compromising the value of the clinical environment for learning [ 10 ].

The first clinical placement often occurs soon after commencing nursing training and can challenge students’ beliefs, philosophies, and preconceived ideas about nursing. An experience of cultural or ‘reality’ shock often arises when entering the healthcare setting, creating dissonance between reality and expectations [ 6 , 14 ]. These experiences may be exacerbated by tertiary education providers teaching of ‘ideal’ clinical practice [ 2 , 6 ]. The perceived distance between theoretical knowledge and what is expected in a healthcare placement, as opposed to what occurs on clinical placement, has been well documented as the theory-practice gap or an experience of cognitive dissonance [ 2 , 3 ].

Given the pivotal role of the first clinical placement in nursing students’ trajectories to nursing practice, it is important to understand students’ experiences and to explore how the placement experience shapes initial perceptions. Existing research focusses almost entirely either on describing nursing students’ projected emotions and perceptions prior to undertaking a first clinical placement [ 3 ] or examines student perceptions of reflecting on a completed first placement [ 15 ]. We wished to examine consistency and change in student perception of their first clinical placement by tracking their experiences longitudinally. We focused on a first clinical placement undertaken in a Master of Nursing Science. This two-year postgraduate qualification provides entry-to-practice nursing training for students who have completed any undergraduate qualification. The first clinical placement component of the course aimed to orient students to the clinical environment, support students to acquire skills and develop their clinical reasoning through experiential learning with experienced nursing mentors.

This paper makes a significant contribution to understanding how nursing students’ perceptions might develop over time because of their clinical placement experiences. Our research addresses a further gap in the existing literature, by focusing on students completing an accelerated postgraduate two-year entry-to-practice degree open to students with any prior undergraduate degree. Thus, the current research aimed to understand nursing students’ emotional responses and expectations and their perceptions of preparedness before attending their first clinical placement and to contrast these initial perceptions with their end-of-placement perspectives.

Study design

A descriptive qualitative study was undertaken, utilising a pre- and post-design for data collection. Focus groups with first-year postgraduate entry-to-practice nursing students were conducted before the first clinical placement, with individual semi-structured interviews undertaken during the first clinical placement.

Setting and participants

All first-year students enrolled in the two-year Master of Nursing Science program ( n = 190) at a tertiary institution in Melbourne, Australia, were eligible to participate. There were no exclusion criteria. At the time of this study, students were enrolled in a semester-long subject focused on nursing assessment and care. They studied the theoretical underpinnings of nursing and science, theoretical and practical nursing clinical skills and Indigenous health over the first six weeks of the course. Students completed a preclinical assessment as a hurdle before commencing a three-week clinical placement in a hospital setting, a subacute or acute environment. Overall, the clinical placement aimed to provide opportunities for experiential learning, skill acquisition, development of clinical reasoning skills and professional socialisation [ 16 , 17 ].

In total, sixteen students participated voluntarily in a focus group of between 60 and 90 min duration; ten of these students also participated in individual interviews of between 30 and 60 min duration, a number sufficient to reach data saturation. Table 1 shows the questions used in the focus groups conducted before clinical placement commenced and the questions for the semi-structured interview questions conducted during clinical placement. Study participants’ undergraduate qualifications included bachelor’s degrees in science, arts and business. A small number of participants had previous healthcare experience (e.g. as healthcare assistants). The participants attended clinical placement in the Melbourne metropolitan, Victorian regional and rural hospital locations.

Data collection

The study comprised two phases. The first phase comprised six focus groups prior to the first clinical placement, and the second phase comprised ten individual semi-structured interviews towards the end of the first clinical placement. Focus groups (with a maximum of four participants) and individual interviews were conducted by the lead author online via Zoom and were audio-recorded. Capping group size to a relatively small number considered diversity of perceptions and opportunities for participants to share their insights and to confirm or contradict their peers, particularly in the online environment [ 18 , 19 ].

Focus groups and interview questions were developed with reference to relevant literature, piloted with volunteer final-year nursing students, and then verified with the coauthors. All focus groups and interviewees received the same structured questions (Table 1 ) to ensure consistency and to facilitate comparison across the placement experience in the development of themes. Selective probing of interviewees’ responses for clarification to gain in-depth responses was undertaken. Nonverbal cues, impressions, or observations were noted.

The lead author was a registered nurse who had a clinical teaching role within the nursing department and was responsible for coordinating clinical placement experiences. To ensure rigour during the data collection process, the lead author maintained a reflective account, exploring her experiences of the discussions, reflecting on her interactions with participants as a researcher and as a clinical educator, and identifying areas for improvement (for instance allowing participants to tell their stories with fewer prompts). These reflections in conjunction with regular discussion with the other authors throughout the data collection period, aided in identifying any researcher biases, feelings and thoughts that possibly influenced the research [ 20 ].

To maintain rigour during the data analysis phase, we adhered to a systematic process involving input from all authors to code the data and to identify, refine and describe the themes and subthemes reported in this work. This comprehensive analytic process, reported in detail in the following section, was designed to ensure that the findings arising from this research were derived from a rigorous approach to analysing the data.

Data analysis

Focus groups and interviews were transcribed using the online transcription service Otter ( https://otter.ai/ ) and then checked and anonymised by the first author. Preliminary data analysis was carried out simultaneously by the first author using thematic content analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke [ 21 ] using NVivo 12 software [ 22 ]. All three authors undertook a detailed reading of the first three transcripts from both the focus groups and interviews and independently identified major themes. This preliminary coding was used as the basis of a discussion session to identify common themes between authors, to clarify sources of disagreement and to establish guidelines for further coding. Subsequent coding of the complete data set by the lead author identified a total of 533 descriptive codes; no descriptive code was duplicated across the themes. Initially, the descriptive codes were grouped into major themes identified from the literature, but with further analysis, themes emerged that were unique to the current study.

The research team met frequently during data analysis to discuss the initial descriptive codes, to confirm the major themes and subthemes, to revise themes on which there was disagreement and to identify any additional themes. Samples of quotes were reviewed by the second and third authors to decide whether these quotes were representative of the identified themes. The process occurred iteratively to refine the thematic categories, to discuss the definitions of each theme and to identify exemplar quotes.

Ethical considerations

The lead author was a clinical teacher and the clinical placement coordinator in the nursing department at the time of the study. Potential risks of perceived coercion and power imbalances were identified because of the lead author’s dual roles as an academic and as a researcher. To manage these potential risks, an academic staff member who was not part of the research study informed students about the study during a face-to-face lecture and ensured that all participants received a plain language statement identifying the lead author’s role and how perceived conflicts of interest would be managed. These included the lead author not undertaking any teaching or assessment role for the duration of the study and ensuring that placement allocations were completed prior to undertaking recruitment for the study. All students who participated in the study provided informed written consent. No financial or other incentives were offered. Approval to conduct the study was granted by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (Ethics ID 1955997.1).

Three main themes emerged describing students’ feelings and perceptions of their first clinical placement. In presenting the findings, before or during has been assigned to participants’ quotes to clarify the timing of students’ perspectives related to the clinical placement.

Major theme 1: Adjusting and managing a raft of feelings

The first theme encompassed the many positive and negative feelings about work-integrated learning expressed by participants before and during their clinical placement. Positive feelings before clinical placement were expressed by participants who were comfortable with the unknown and cautiously optimistic.

I am ready to just go with the flow, roll with the punches (Participant [P]1 before).

Overwhelmingly, however, the majority of feelings and thoughts anticipating the first clinical placement were negatively oriented. Students who expressed feelings of fear, anxiety, lack of knowledge, lack of preparedness, uncertainty about nursing as a career, or strong concerns about being a burden were all classified as conveying negative feelings. These negative feelings were categorised into four subthemes.

Subtheme 1.1 I don’t have enough knowledge

All participants expressed some concerns and anxiety before their first clinical placement. These encompassed concerns about knowledge inadequacy and were linked to a perception of under preparedness. Participants’ fears related to harming patients, responsibility for managing ‘real’ people, medication administration, and incomplete understanding of the language and communication skills within a healthcare setting. Anxiety for many participants merged with the logistics and management of their life during the clinical placement.

I’m scared that they will assume that I have more knowledge than I do (P3 before). I feel quite similar with P10, especially when she said fear of unknown and fear that she might do something wrong (P9 before).

Subtheme 1.2 Worry about judgment, being seen through that lens

Participants voiced concerns that they would be judged negatively by patients or healthcare staff because they perceived that the student nurse belonged to specific social groups related to their cultural background, ethnicity or gender. Affiliation with these groups contributed to students’ sense of self or identity, with students often describing such groups as a community. Before the clinical placement, participants worried that such judgements would impact the support they received on placement and their ability to deliver patient care.

Some older patients might prefer to have nurses from their own background, their own ethnicity, how they would react to me, or if racism is involved (P10 before). I just don’t want to reinforce like, whatever negative perceptions people might have of that community (P16 before).

Participants’ concerns prior to the first clinical placement about judgement or poor treatment because of patients’ preconceived ideas about specific ethnic groups did not eventuate.

I mean, it didn’t really feel like very much of a thing once I was actually there. It is one of those things you stress about, and it does not really amount to anything (P16 during).

Some students’ placement experiences revealed the positive benefits of their cultural background to enhancing patient care. One student affirmed that the placement experience reinforced their commitment to nursing and that this was related to their ability to communicate with patients whose first language was not English.

Yeah, definitely. Like, I can speak a few dialects. You know, I can actually see a difference with a lot of the non-English speaking background people. As soon as you, as soon as they’re aware that you’re trying and you’re trying to speak your language, they, they just open up. Yeah, yes. And it improves the care (P10 during).

However, a perceived lack of judgement was sometimes attributed to wearing the full personal protective equipment required during the COVID-19 pandemic, which meant that their personal features were largely obscured. For this reason, it was more difficult for patients to make assumptions or attributions about students’ ethnic or gender identity based on their appearance.

People tend to assume and call us all girls, which was irritating. It was mostly just because all of us were so covered up, no one could see anyone’s faces (P16 during).

Subtheme 1.3 Is nursing really for me?

Prior to their first clinical placement experience, many participants expressed ambivalence about a nursing career and anticipated that undertaking clinical placement could determine their suitability for the profession. Once exposed to clinical placement, the majority of students were completely committed to their chosen profession, with a minority remaining ambivalent or, in rare cases, choosing to leave the course. Not yet achieving full commitment to a nursing career was related to not wishing to work in the ward they had for their clinical placement, while remaining open to trying different specialities.

I didn’t have an actual idea of what I wanted to do after arts, this wasn’t something that I was aiming towards specifically (P14 before). I think I’m still not 100%, but enough to go on, that I’m happy to continue the course as best as I can (P11 during).

Subtheme 1.4 Being a burden

Before clinical placement, participants had concerns about being burdensome and how this would affect their clinical placement experiences.

If we end up being a burden to them, an extra responsibility for them on top of their day, then we might not be treated as well (P10 before).