The Most Contentious Meal of the Day

The current debates about breakfast are nothing new; the morning meal has long been a source of medical confusion, moral frustration, and political anxiety.

It was the (up)shot heard ‘round the world. In May, The New York Times ’s data blog , having conducted a lengthy review of scholarly assessments of the meal that Americans have been told, time after time, is the day’s most important, declared what many had known, in their hearts as well as their stomachs, to be true: “Sorry, there’s nothing magical about breakfast.”

Recommended Reading

Toward a Universal Theory of ‘Mom Jeans’

My Friend Mister Rogers

The Life in The Simpsons Is No Longer Attainable

The pre-emptive “sorry” was an appropriate way both to soften the announcement and to sharpen it: Breakfast—when to eat it, what to eat for it (cereal? smoothies? cage-free eggs fried in organic Irish butter?), whether to eat it at all—has long been a subject of intense debate, accompanied by intense confusion and intense feeling. “Breakfast nowadays is cool,” the writer Jen Doll noted in Extra Crispy , the new newsletter from Time magazine that is devoted to, yep, breakfast. She wrote that in an essay about her failed attempt to enjoy pre-noon eating.

But breakfast wasn’t always cool. People of the Middle Ages shunned it on roughly the same grounds—food’s intimate connection to moral ideals of self-regimentation—that people of the current age glorify it; later, those navigating the collision of industrialization and the needs of the human body came to blame hearty breakfasts for indigestion and other ailments. Breakfast has been subject to roughly the same influences that any other fickle food fashions will be: social virality, religious dogmas, economic cycles, new scientific discoveries about the truth or falsity of the old saying “you are what you eat.” And all that has meant that the meal associated with the various intimacies of the morning hours has transformed, fairly drastically, over the centuries. Our current confusion when it comes to breakfast is, for better or worse, nothing new: We in the West, when it comes to our eggs—and our pancakes, and our bacon, and our muffins, and our yogurt, and our coffee—have long been a little bit scrambled.

The Europeans of the Middle Ages largely eschewed breakfast. Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica , lists praepropere —eating too soon— as one of the ways to commit the deadly sin of gluttony ; the eating of a morning meal, following that logic, was generally considered to be an affront against God and the self. Fasting was seen as evidence of one’s ability to negate the desires of the flesh; the ideal eating schedule, from that perspective, was a light dinner (then consumed at midday) followed by heartier supper in the evening. People of the Middle Ages, the food writer Heather Arndt Anderson notes in her book Breakfast: A History , sometimes took another evening meal, an indulgent late-evening snack called the reresoper (“rear supper”). The fact that the reresoper was taken with ale and wine, Anderson writes, meant that it was “shunned by most decent folk”; that fact also might have contributed to breakfast’s own low status among medieval moralists, as “it was presumed that if one ate breakfast, it was because one had other lusty appetites as well.”

There were some exceptions to those prohibitions . Laborers were allowed a breakfast—they needed the calories for their morning exertions—as were the elderly, the infirm, and children. Still, the meal they took was generally small—a chunk of bread, a piece of cheese, perhaps some ale—and not treated as a “meal,” a social event, so much as a pragmatic necessity.

It was Europe’s introduction to chocolate, Anderson argues, that helped to change people’s perspective on the moral propriety of breaking fast in the morning hours. “Europe was delirious with joy” at the simultaneous arrival, via expeditions of the New World, of coffee, tea, and chocolate (which Europeans of the time often took as a beverage), she writes. Chocolate in particular “caused such an ecstatic uproar among Europe’s social elite that the Catholic Church began to feel the pressure to change the rules.” And so, in 1662, Cardinal Francis Maria Brancaccio declared that “ Liquidum non frangit jejunum ”: “Liquid doesn’t break the fast.”

That barrier to breakfast having been dismantled, people started to become breakfast enthusiasts. Thomas Cogan, a schoolmaster in Manchester, was soon claiming that breakfast, far from being merely acceptable, was in fact necessary to one’s health : “[to] suffer hunger long filleth the stomack with ill humors.” Queen Elizabeth was once recorded eating a hearty breakfast of bread, ale, wine, and “a good pottage [stew], like a farmer’s, made of mutton or beef with ‘real bones.’”

The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century—and the rise of factory work and office jobs that accompanied it—further normalized breakfast, transforming it, Abigail Carroll writes in Three Squares: The Invention of the American Meal , from an indulgence to an expectation. The later years of the 1800s, in particular, saw an expansion of the morning meal into a full-fledged social event. Wealthy Victorians in the U.S. and in England dedicated rooms in their homes to breakfasting, the BBC notes , considering the meal a time for the family to gather before they scattered for the day. Newspapers targeted themselves for at-the-table consumption by the men of the families. Morning meals of the wealthy often involved enormous, elaborate spreads: meats, stews, sweets.

With that, the Victorians met the Medieval edicts against breakfast by swinging to the other extreme: Breakfast became not a prohibition or a pragmatic acquiescence to the demands of the day, but rather a feast in its own right. And that soon led to another feature of industrialization, Carroll writes: the host of health problems , indigestion chief among them, that people of the 19th century and the early 20th came to know as “dyspepsia.” They weren’t sure exactly what caused those problems; they suspected, however, that the heavy meals of the morning hours were key contributors. (They were, of course, correct.)

Here were the roots of the current obesity epidemic—the culinary traditions of active lifestyles, imported to sedentary ones—and they led to another round of debates about what breakfast was and should be. Fighting against his era’s preference for heavy breakfasts, Pierre Blot, the French cookbook author and professor of gastronomy, stipulated that breakfast that be, ideally, as small as possible . He also argued that it should, when consumed at all, consist of meats (cold, leftover from the supper the night before) rather than cakes or sweets, which rotted the teeth. (Blot further advised against taking tea with breakfast—water, coffee, milk, and even cocoa were preferable—and prohibited liquor.)

Blot was echoed in his advice by the Clean Living Movement that arose during the Jacksonian era and that has remained as a feature of American culture, in some form, ever since. The movement, which emphasized vegetarianism and resisted industrialized food processes like the chemical leavening of bread, also recommended abstinence from stimulants like coffee and tea. It led to products like Sylvester Graham’s eponymous “crackers”—made of the whole grain that, Graham thought, would curb sexual appetites along with those of the stomach —and helped to make cereal a thus-far-enduring feature of the American breakfast table. (The irony that the “cereal” of today is laden with sugar and chemicals would surely not be lost on Graham or on his fellow Clean Living proponent, John Harvey Kellogg.)

The cereals invented by Graham and Kellogg and C.W. Post became popular in part because they could simply be poured into bowls, with no cooking required; soon, technological developments were doing their own part to turn the laborious breakfasts of the 19th century into briefer, simpler affairs. The advent of toasters meant that stale bread could be quickly converted, with the help of a little butter and maybe some jam, into satisfying meals. Waffle irons and electric griddles and the invention in Bisquik, in 1930, did the same. Those appliances and other cooking aids made breakfast more convenient to produce during a time that found more and more women leaving the home for the workplace—first in response to the labor shortages brought about by the World Wars, and then on their own accord.

But breakfast also became more fraught. During a time that found Betty Friedan equating cooking with the systemic oppression of women , the morning meal forced a question: Could women both win bread and toast it? Breakfast presented a similar challenge for men: In the 1940s and 1950s, Anderson notes , amid the anxieties about traditional gender roles that the post-war climate brought about, cookbooks aimed at men emerged in the marketplace. They suggested how to cook breakfasts, in particular, that would be composed of “manly” foods like steak and bacon. They proposed that eggs be fried not in pats of butter, but in “man-sized lumps” of it. Even baked goods got masculine-ized : Brick Gordon, in 1947, recommended that male cooks might, if baking biscuits, eschew ladylike rolling pins for … beer bottles.

Today, those anxieties live on, in their way: Breakfast remains fraught, politically and otherwise. (And that’s not even outside of the slow-poached minefield that is brunch .) The current debates, though, tend to address not gender roles, but rather considerations of health—for the individual consumer, for the culture in which they participate, and for the planet. The low-fat craze of the 1990s, the low-carb craze of the 2000s, today’s anxieties about animal cruelty and environmental sustainability and GMOs and gluten and longevity and, in general, the moral dimensions of a globalized food system—all of them are embodied in breakfast.

And so is another unique feature of contemporary life: the internet argument. The essay in which Jen Doll declared breakfast’s coolness was a confessional titled “I’m a Breakfast Hater.” The Times ’s article describing the non-magical nature of breakfast was preceded by “ Is Breakfast Overrated? ” and, elsewhere on the web, an article explaining breakfast’s importance from the blog Shake Up Your Wake Up. It was preceded by thousands of other pieces that are all, in some way, engaging with profound questions about the most basic meal of the day. One of them was from The Times itself. It was called “ Seize the Morning: The Case for Breakfast .”

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

How the kellogg brothers transformed breakfast and pioneered ‘wellness’.

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-the-kellogg-brothers-transformed-breakfast-and-pioneered-wellness

The Kellogg brothers transformed the American breakfast. They promoted revolutionary ideas we now consider central to wellness, and celebrities flocked to their famous sanitarium and spa in Battle Creek, Michigan. But their commercial success came at a heavy personal cost. William Brangham talks to Dr. Howard Markel about his new book, "The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek."

Read the Full Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Judy Woodruff:

It is said that roughly 350 million people ate a bowl of Kellogg's Corn Flakes today. The ubiquitous cereal is a testament to our modern-day revolution in ready-to-eat foods.

And it's also the brainchild of two fascinating brothers from Battle Creek, Michigan.

William Brangham is here with the latest installment of the "NewsHour" Bookshelf.

William Brangham:

America's stomach ached for much of the 19th and early 20th century. Walt Whitman called it the great American evil, the nation's intense, widespread indigestion, fueled in part by what Americans were eating for breakfast, potatoes cooked in congealed fat, heavily salted meats, gruels and mush slow-cooked for hours over wood-burning stoves.

Enter the Kellogg brothers. Out of their medical complex, grand hotel and spa in Battle Creek, Michigan came an invention, ready-to-eat, easily digestible, quick-to-prepare breakfast cereals.

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, a beloved doctor to stars and presidents, baked the first batches of flaked cereal with his younger brother, Will Kellogg. Will eventually turned that recipe into corn flakes and birthed a multibillion-dollar company.

Together, the brothers transformed the American breakfast and helped foster many of the ideas now considered central to health and wellness.

But it all came at great personal cost. Their story is the focus of a new book out in paperback, "The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek."

It's by Dr. Howard Markel, a medical historian at the University of Michigan and a regular columnist for the "PBS NewsHour."

And Dr. Howard Markel joins me now.

The Kellogg name in American society is now, of course, hopelessly associated with breakfast and breakfast foods, but even before that, they had, especially John, had some very pioneering ideas about health, well before their time.

Dr. Howard Markel:

Absolutely.

You know, Dr. Kellogg created the term that we would now call wellness. And so he prescribed all sorts of healthy living practices, with the notion that it's far easier to prevent a disease than to treat it after the body has broken down.

So he advised about good diets, grain and vegetable diets, but no meat. He advised against nicotine or smoking of any kind, caffeine, alcohol. And he prescribed lots of exercise and fresh air, when people were not doing that at all.

They created a sanitarium in Battle Creek, and — what was called a sanitarium. And it centered around what you referred to as biologic living. This was a term that they coined?

What does that mean?

That was the doctor's term for wellness and the thought that you took care of your body.

It came from some of his religious beliefs as a Seventh Day Adventist. But he added on to them, using the best medical literature of the day, always shoehorning the latest science into his world view. And he wanted to teach both the healthy and the unhealthy how to live healthier lives.

But it was also a complete medical center, and a grand hotel and spa all rolled into one. Tens of thousands of people came to Battle Creek every year. It was the most popular train stop on the Michigan Central between Chicago and Detroit.

And lots of celebrities came as well. Johnny Weissmuller, the old Tarzan from the MGM movies, he would do his Tarzan yell just before the meal started.

Amelia Earhart, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, John D. Rockefeller Jr., they all came.

One of the Dr. Kellogg's goals was to develop an easily digestible breakfast food, and that's the cereal that we now all know, which maybe turned out to be not the healthiest food after all.

But why was that his goal? What was the — what was his drive there?

Well, you have to remember who he was seeing. They were mostly very constipated people who ate a terrible…

Literally, who saw — it wasn't — not just an adjective.

But they were eating terrible, fatty diets. They were often obese.

So he thought, if I could make grains more digestible, maybe that would help these invalided patients, as he called them.

And so first it was just rolls, until one lady broker dentures on these hard double-baked rolls and wanted him to replace her dentures. Then he ground them up into little, tiny kernels. And, finally, they came up with flaked cereal.

And it is indeed easily digested, and, probably, if you have a stomach ache, that might be a good food to eat.

But this whole process was what gave birth to, I guess, then wheat flakes, and now corn flakes as we know it.

Yes, they were originally wheat flakes.

And then John's little brother, Will, who really ran the sanitarium, experimented with it on and on and on, and he developed corn flakes because corn was a cheaper grain and it was tastier.

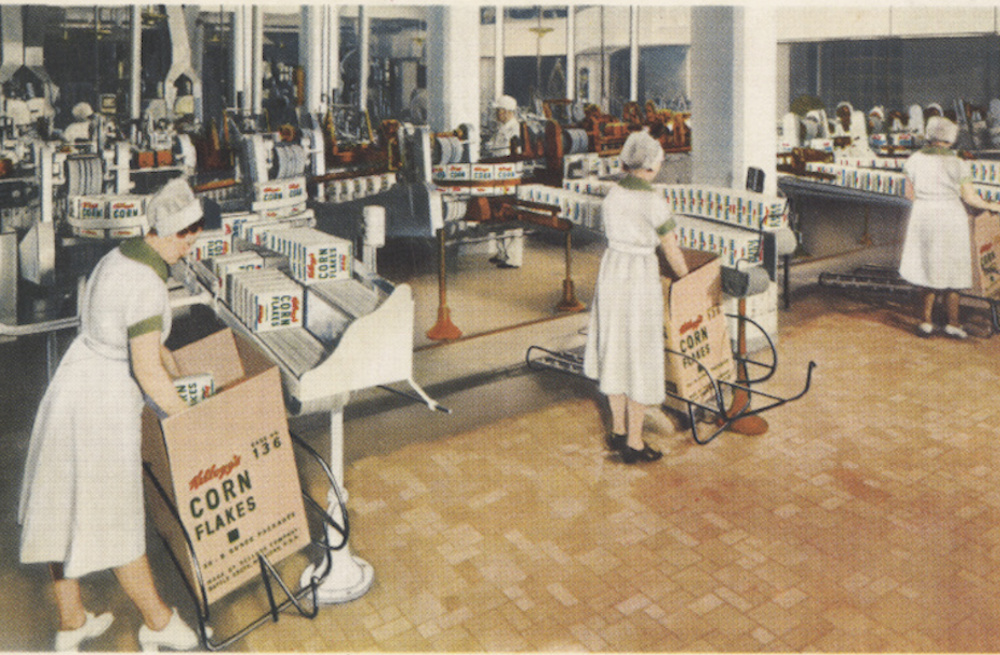

And when it came out in 1906, it took the world by storm, because now even a father could make breakfast simply by pouring it out of the box. And people just loved it.

You write a lot about the relationship between the brothers.

And for as close as that working relationship and personal relationship was, it does sound that they really — there was a real antipathy between them.

Can you describe a little bit about them?

Yes, that's putting it mildly.

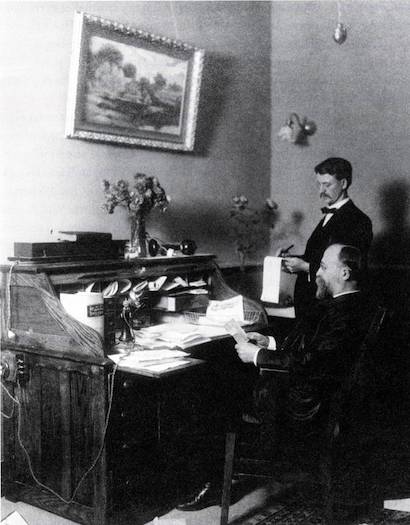

John Harvey was eight years older than Will, and he treated Will like a little brother. But he could also dominate him and treat him very badly.

So, when the doctor was riding his bicycle across the campus of the sanitarium, Will had to run along and take notes. When the doctor had one of his five daily bowel movements, he would ask Will to come or order Will to come into the bathroom with him and take notes on his latest lecture or his latest book chapter, so that he wouldn't miss it.

And no wonder Will hated his guts. And with all this dominant relationship, Will finally decided, at the age of 46, to leave the doctor's employ after 25 years and founded what people Kellogg's.

They did sue each other for almost a decade over who had the right to be the real Kellogg. The doctor said, well, I'm the famous Dr. Kellogg. And he was more famous than Will at the time, bestselling author, lecturer and so on.

Will said, well, look, I have advertised everywhere. I have spent millions of dollars. I have the largest electric sign in the world in Times Square. And I…

He really was a commercial genius.

He was brilliant. He adopted advertising. He adopted electricity in his factories, conveyor belts.

He marketed to the perfect demographic, mothers and their children. He invented the toy in the box, which was really great, because it took up space and was cheaper than the corn flakes.

And so he said, I'm the real Kellogg, and then all the way up to the Michigan State Supreme Court. And the judges said, when we think of Kellogg's, we think of the cereal.

So, Will won.

The problem was that, after that, they rarely spoke to one another, and they lost a great deal. This is such a great American story. The fact that they had this sadness in their life, this rift, to me, was the great tragedy of the brothers Kellogg.

The book is "The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek."

Dr. Howard Markel, thank you very much.

Listen to this Segment

Watch the Full Episode

Support Provided By: Learn more

More Ways to Watch

Educate your inbox.

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Get More Zócalo

Eclectic but curated. Smart without snark. Ideas journalism with a head and heart.

Zócalo Podcasts

How the Kellogg Brothers Taught America to Eat Breakfast

Informed by their religious faith, the siblings merged spiritual with physical health.

Women in a factory, boxing Kellogg’s corn flakes. Image courtesy of Miami University Libraries, Digital Collections/ Wikimedia Commons .

By Howard Markel | August 3, 2017

Fewer still know that among the ingredients in the Kelloggs’ secret recipe were the teachings of the Seventh-day Adventist church, a homegrown American faith that linked spiritual and physical health, and which played a major role in the Kellogg family’s life.

For half a century, Battle Creek was the Vatican of the Seventh-day Adventist church. Its founders, the self-proclaimed prophetess Ellen White and her husband, James, made their home in the Michigan town starting in 1854, moving the church’s headquarters in 1904 to Takoma Park, outside of Washington, D.C. Eventually, Seventh-day Adventism grew into a major Christian denomination with churches, ministries, and members all around the world. One key component of the Whites’ sect was healthy living and a nutritious, vegetable and grain based diet.

Patrons dining at the Battle Creek Sanitarium. Image courtesy of the Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

From the distance of more than a century and a half, it is fascinating to note how many of Ellen White’s religious experiences were connected to personal health. During the 1860s, inspired by visions and messages she claimed to receive from God, she developed a doctrine on hygiene, diet, and chastity enveloped within the teachings of Christ. She began promoting health as a major part of her ministry as early as June 6, 1863. At a Friday evening Sabbath welcoming service in Otsego, Michigan, she described a 45-minute revelation on “the great subject of Health Reform,” which included advice on proper diet and hygiene. Her canon of health found greater clarity in a sermon that she delivered on Christmas Eve 1865 in Rochester, New York. White vividly described a vision from God which emphasized the importance of diet and lifestyle in helping worshippers stay well, prevent disease, and live a holy life. Good health relied on physical and sexual purity, White preached, and because the body was intertwined with the soul her prescriptions would help eliminate evil, promote the greater good in human society, and please God.

The following spring, on May 20, 1866, “Sister” White formally presented her ideas to the 3,500 Adventists comprising the denomination’s governing body, or General Conference. When it came to diet, White’s theology found great import in Genesis 1:29: “And God said, ‘Behold, I have given you every herb bearing seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in the which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat.’” White interpreted this verse strictly, as God’s order to consume a grain and vegetarian diet.

She told her Seventh-day Adventist flock that they must abstain not only from eating meat but also from using tobacco or consuming coffee, tea, and, of course, alcohol. She warned against indulging in the excitatory influences of greasy, fried fare, spicy condiments, and pickled foods; against overeating; against using drugs of any kind; and against wearing binding corsets, wigs, and tight dresses. Such evils, she taught, led to the morally and physically destructive “self-vice” of masturbation and the less lonely vice of excessive sexual intercourse.

Dr. John Kellogg dictating to his brother Will, circa 1890. Image courtesy of John Harvey Kellogg Papers, Bentley Historical Library, The University of Michigan.

The Kellogg family moved to Battle Creek in 1856, primarily to be close to Ellen White and the Seventh-day Adventist church. Impressed by young John Harvey Kellogg’s intellect, spirit, and drive, Ellen and James White groomed him for a key role in the Church. They hired John, then 12 or 13, as their publishing company’s “printer’s devil,” the now-forgotten name for an apprentice to printers and publishers in the days of typesetting by hand and cumbersome, noisy printing presses. Like many other American printer’s devils who went on to greatness—including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Lyndon Johnson—Kellogg mixed up batches of ink, filled paste pots, retrieved individual letters of type to set, and proofread the not-always-finished printed copy. He was swimming in a river of words and took to it with glee, discovering his own talent for composing clear and balanced sentences, filled with rich explanatory metaphors and allusions. By the time he was 16, Kellogg was editing and shaping the church’s monthly health advice magazine, The Health Reformer .

The Whites wanted a first-rate physician to run medical and health programs for their denomination and they found him in John Harvey Kellogg. They sent the young man to the Michigan State Normal College in Ypsilanti, the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and the Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York. It was during medical school when a time-crunched John, who prepared his own meals on top of studying round the clock, first began to think about creating a nutritious, ready-to-eat cereal.

Upon returning to Battle Creek in 1876, with the encouragement and leadership of the Whites, the Battle Creek Sanitarium was born and within a few years it became a world famous medical center, grand hotel, and spa run by John and Will, eight years younger, who ran the business and human resources operations of the Sanitarium while the doctor tended to his growing flock of patients. The Kellogg brothers’ “San” was internationally known as a “university of health” that preached the Adventist gospel of disease prevention, sound digestion, and “wellness.” At its peak, it saw more than 12,000 to 15,000 new patients a year, treated the rich and famous, and became a health destination for the worried well and the truly ill.

There were practical factors, beyond those described in Ellen White’s ministry, that inspired John’s interest in dietary matters. In 1858, Walt Whitman described indigestion as “the great American evil.” A review of mid-19th-century American diet on the “civilized” eastern seaboard, within the nation’s interior, and on the frontier explains why one of the most common medical complaints of the day was dyspepsia, the 19th-century catchall term for a medley of flatulence, constipation, diarrhea, heartburn, and “upset stomach.”

Breakfast was especially problematic. For much of the 19th century, many early morning repasts included filling, starchy potatoes, fried in the congealed fat from last night’s dinner. For protein, cooks fried up cured and heavily salted meats, such as ham or bacon. Some people ate a meatless breakfast, with mugs of cocoa, tea, or coffee, whole milk or heavy cream, and boiled rice, often flavored with syrup, milk, and sugar. Some ate brown bread, milk-toast, and graham crackers to fill their bellies. Conscientious (and frequently exhausted) mothers awoke at the crack of dawn to stand over a hot, wood-burning stove for hours on end, cooking and stirring gruels or mush made of barley, cracked wheat, or oats.

Advertisement, 1934. Image courtesy of N. W. Ayer Advertising Agency Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

It was no wonder Dr. Kellogg saw a need for a palatable, grain-based “health food” that was “easy on the digestion” and also easy to prepare. He hypothesized that the digestive process would be helped along if grains were pre-cooked—essentially, pre-digested—before they entered the patient’s mouth. Dr. Kellogg baked his dough at extremely high heat to break down starch contained in the grain into the simple sugar dextrose. John Kellogg called this baking process dextrinization. He and Will labored for years in a basement kitchen before coming up with dextrinized flaked cereals—first, wheat flakes, and then the tastier corn flakes. They were easily-digested foods meant for invalids with bad stomachs.

Today most nutritionists, obesity experts, and physicians argue that the easy digestibility the Kelloggs worked so hard to achieve is not such a good thing. Eating processed cereals, it turns out, creates a sudden spike in blood sugar, followed by an increase in insulin, the hormone that enables cells to use glucose. A few hours later, the insulin rush triggers a blood sugar “crash,” loss of energy, and a ravenous hunger for an early lunch. High fiber cereals like oatmeal and other whole grain preparations are digested more slowly. People who eat them report feeling fuller for longer periods of time and, thus, have far better appetite control than those who consume processed breakfast cereals.

By 1906, Will had had enough of working for his domineering brother, who he saw as a tyrant who refused to allow him the opportunity to grow their cereal business into the empire he knew it could become. He quit the San and founded what ultimately became the Kellogg’s Cereal Company based upon the brilliant observation that there were many more normal people who wanted a nutritious and healthy breakfast than invalids—provided the cereal tasted good, which by that point it did, thanks to the addition of sugar and salt.

The Kelloggs had the science of corn flakes all wrong, but they still became breakfast heroes. Fueled by 19th-century American reliance on religious authority, they played a critical role in developing the crunchy-good breakfast many of us ate this morning.

Send A Letter To the Editors

Please tell us your thoughts. Include your name and daytime phone number, and a link to the article you’re responding to. We may edit your letter for length and clarity and publish it on our site.

(Optional) Attach an image to your letter. Jpeg, PNG or GIF accepted, 1MB maximum.

By continuing to use our website, you agree to our privacy and cookie policy . Zócalo wants to hear from you. Please take our survey !-->

No paywall. No ads. No partisan hacks. Ideas journalism with a head and a heart.

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Examples >

- Essay Topics

Essays on American Breakfast

1 sample on this topic

Writing a lot of American Breakfast papers is an inherent part of modern studying, be it in high-school, college, or university. If you can do that unassisted, that's just awesome; yet, other students might not be that lucky, as American Breakfast writing can be quite challenging. The directory of free sample American Breakfast papers offered below was set up in order to help flunker learners rise up to the challenge.

On the one hand, American Breakfast essays we showcase here clearly demonstrate how a really exceptional academic paper should be developed. On the other hand, upon your request and for a fair cost, a pro essay helper with the relevant academic background can put together a fine paper model on American Breakfast from scratch.

Traditional American Breakfast: A Complete Guide

Dive into the heart of American mornings with our guide to the traditional American breakfast. I'll show you the must-haves that make a breakfast truly American, from fluffy pancakes to crispy bacon. We'll explore menus, recipes, and the secrets behind crafting these beloved dishes. Whether you're a busy parent or on the go, this guide has everything to start your day right. Let's bring the taste of America to your table!

- Traditional American breakfast includes eggs, pancakes, bacon, and toast, often enjoyed between 6 AM and 9 AM.

- Weekends and holidays see larger, traditional meals, reflecting a culture of connection over morning meals.

- American breakfasts vary regionally, from biscuits and gravy in the South to breakfast tacos in Texas.

- Quick and easy options like breakfast sandwiches and oatmeal cater to busy mornings and kid-friendly meals.

- The American breakfast has evolved from light continental fare to hearty, diverse options with a trend towards healthier choices.

- Top breakfast spots and chains across the USA include The Pancake House, Denny’s, IHOP, and Panera Bread, with a focus on both taste and health.

- Homemade traditional breakfasts can be made with simple recipes for scrambled eggs, bacon, and pancakes, emphasizing fresh ingredients and low heat cooking.

What Are the Essentials of a Traditional American Breakfast?

Overview of traditional american breakfast foods.

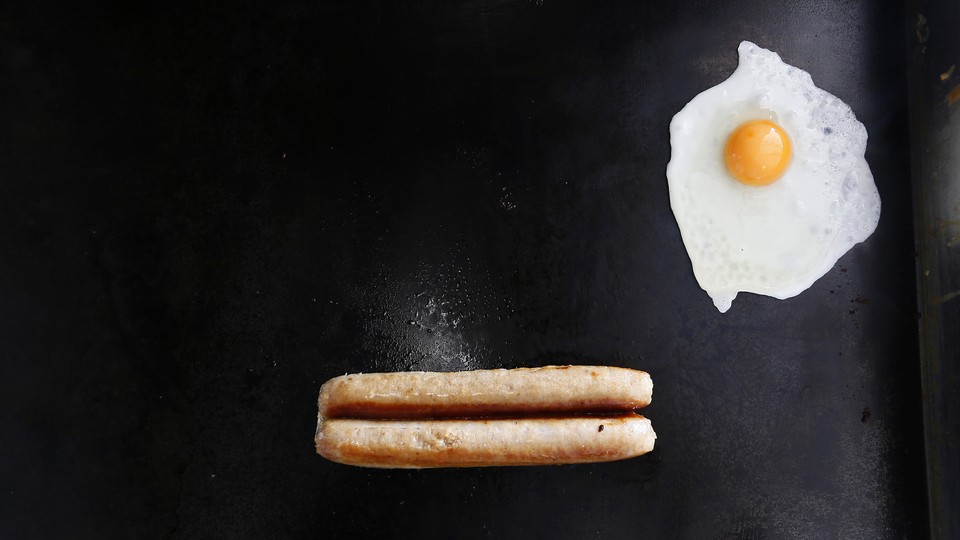

American breakfast is not just a meal; it's a feast for the taste buds. Eggs, pancakes, bacon, and toast make up the core. Picture eggs, sunny side up, with crispy bacon strips. Add fluffy pancakes on the side drizzled with maple syrup. A slice or two of buttered toast often seals the deal.

Crafting the Perfect American Breakfast Menu

To craft a true American breakfast menu, you must choose from the essentials. Eggs can be fried, scrambled, or poached. Bacon or sausage brings that savory punch. Pancakes or waffles add a sweet touch. Don't forget a hot cup of brewed coffee to wake up your senses.

Recipes for Iconic American Breakfast Dishes

Let’s explore a simple recipe for a classic breakfast dish:

Traditional Pancakes:

- Ingredients:

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- 2 tbsp sugar

- 2 tsp baking powder

- 1/2 tsp salt

- 2 tbsp melted butter

- Mix flour, sugar, baking powder, and salt in a big bowl.

- In another bowl, whisk milk and egg.

- Pour wet mix into dry ingredients.

- Stir in melted butter.

- Heat a skillet and pour 1/4 cup of batter for each pancake.

- Cook until bubbles form, then flip to brown the other side.

Serve hot with maple syrup or fresh fruit.

Learning to make these dishes at home can bring the taste of American culture right into your kitchen. Each component of breakfast plays a pivotal role in delivering a meal that's hearty and fulfilling, setting the tone for the day ahead. Explore more options and breakfast ideas on Wikipedia's list of American breakfast foods .

When Do Americans Typically Enjoy Breakfast?

Understanding american breakfast traditions and history.

Americans eat breakfast mainly in the morning. Most start their day between 6 AM and 9 AM. This timing fits well with work and school schedules.

The Culture Surrounding Breakfast in the USA

Morning meals are a big deal in the USA. They are more than just eating; they're a time for connection. Families and friends often use this meal to enjoy time together.

In the past, big, hearty breakfasts included eggs, bacon, or sausage, alongside pancakes or waffles. Learn more about traditional American breakfast . This large meal would provide energy for the day. Over time, though, as lives got busier, quicker options became popular. Now, many opt for faster, simpler meals like cereal, toast, or fruit on regular days.

On weekends and holidays, more Americans take time for a fuller breakfast. They revisit the tradition of large, cooked meals. This often includes what's sometimes called a "farmer's breakfast". It's a larger meal meant to fill you up for the day ahead.

Breakfast benefits aren't just about the body. This time can strengthen bonds among loved ones. It's seen as a comforting ritual to start the day positively.

Related Links: – Golden Corral breakfast buffet price: What to Know – First Watch Traditional Breakfast: What to Expect

How Can Breakfast Variations Reflect Regional Differences?

Exploring regional variations of american breakfast.

American breakfast varies a lot from place to place. In the South, you might enjoy biscuits with gravy, while a New Yorker may grab a bagel. This shows how local food, culture, and history shape what folks eat in the morning.

Popular Breakfast Foods Across Different States

In Texas, breakfast tacos steal the show, filled with eggs, cheese, and meat. Head to Vermont, and you'll likely find maple syrup on pancakes. This variation shows unique local tastes and ingredients across the United States. List of American breakfast foods provides a deeper look at different recipes.

Let's talk about breakfast sandwiches, a favorite in many states. About 60% of Americans eat them weekly. They mix bread, eggs, cheese, and meats like bacon. However, many seek healthier options now.

Places like coffee shops have adapted, offering a variety of sandwiches. They cater to all, from vegans to those avoiding gluten. While fast-food options might be less healthy, making sandwiches at home lets you control ingredients, suiting your diet and saving money too.

What Are Some Quick and Easy American Breakfast Ideas?

Easy american breakfast recipes for busy mornings.

Are you always in a rush in the morning? Try making quick breakfast sandwiches. They’re loved by many. You can make them fast. They taste great too. Let’s dive into how to make one.

What you need:

- Bread (whole wheat or white)

- Cheese (cheddar or American)

- Meat (bacon or sausage)

- Cook the meat until it’s crisp.

- Fry or scramble the eggs.

- Toast the bread lightly.

- Layer cheese, eggs, and meat on the bread.

- Close with another slice of bread.

- Heat in a pan until the cheese melts.

This meal fits great with both kids’ tastes and adult diets. It’s very filling.

Kid-Friendly Breakfast Ideas for a Healthy Start

Kids love fun, simple meals. Eggs are a fantastic choice. They are full of protein. You can serve them in so many ways! Scrambled eggs are the easiest. Just beat eggs, pour them into a hot pan, and stir until they're firm. Add some cheese for extra flavor.

For something sweet, make quick oatmeal. Just mix rolled oats with milk or water. Cook them until they're soft. Then top with fruits like bananas or berries. It’s yummy and keeps the kids happy and healthy.

These ideas are not only fast but also versatile. Enjoy your morning with these delicious, easy breakfast recipes that keep the rush manageable and mornings enjoyable!

How Has the American Breakfast Menu Evolved Over Time?

From continental to american breakfast: an evolution story.

The shift from a continental to a traditional American breakfast is striking. Originally, the continental style was more about light fare: think pastries, fruit, and coffee. Now, the American breakfast boasts big, hearty options. Eggs, bacon, and pancakes often grace our tables. In fact, around 60% of us enjoy such savory dishes weekly. The love for these rich, filling meals started many decades ago, as people sought more energy to fuel their busy, active lives.

Trending Breakfast Ingredients in American Cuisine

Breakfast in America has seen many trends. One lasting trend is the breakfast sandwich’s rise in popularity. These quick meals are loved for their convenience and varied options. Commonly, they include eggs, cheese, and meat like bacon. But as health awareness grows, so does the desire for healthier versions. Now, many opt for ingredients like whole wheat bread and egg whites. For more insights into what Americans love on their breakfast plates and to join the conversation, check out what Reddit users say about their favorites here .

Every shift in breakfast choice echoes changes in our lifestyle and values, from fast and convenient to wholesome and nourishing. This meal's evolution paints a vivid picture of American life, reflecting our diversity and dynamism through every bite.

What Are the Best Breakfast Restaurants and Chains in the USA?

Recommendations for top breakfast spots across the usa.

In your quest for the best breakfast in the USA, certain spots shine. You might start your day at "The Pancake House" in New York with their fluffy, famed pancakes. Then, there's "Southern Sunshine Breakfast" in Atlanta, where biscuits and gravy take center stage. Each spot offers a unique take on morning meals.

Popular Breakfast Chains and What They Offer

As for breakfast chains, "Denny’s" and "IHOP" remain favorites. Denny's is loved for its hearty Slam breakfasts, and IHOP is the go-to for an array of pancake options. They cater to all, from those who favor a classic bacon and eggs platter to ones seeking something a bit different like a breakfast burrito.

For a mix of taste and health, "Panera Bread" offers choices that blend both, like their avocado, egg white, and spinach breakfast sandwich. Their focus on fresh, clean ingredients resonates well with health-minded folks.

The rise in popularity of breakfast sandwiches is seen nationwide. Almost 60% of Americans enjoy these sandwiches weekly. While fast food chains feature tempting, quick options, many people opt to make these at home, customizing ingredients to their liking.

Wherever you choose to dine, from coast to coast, delightful breakfast options abound. Check out what Americans eat for breakfast to plan your next morning meal adventure.

How to Make Your Own Traditional American Breakfast at Home?

Step-by-step recipes for a homestyle american breakfast.

Start with a heart of the meal: the eggs. Scramble them for ease. Add salt and pepper to taste. Next, fry up some bacon or sausage. Both add rich flavor to your breakfast. To balance out all that meat, toss bread slices in the toaster for a crunchy bite.

Here’s what you need for scrambled eggs:

- Eggs (2 per person)

- Milk (a splash)

- Salt and pepper

- Butter (for the pan)

- Crack the eggs into a bowl.

- Add milk and whisk until blend is even.

- Heat butter in a pan.

- Pour in the eggs. Stir slowly over low heat. Pull them off when they’re softly set.

- Lay strips in a cold pan.

- Turn heat to medium. Turn them until crisp.

- Drain on paper towels.

Don’t forget a stack of pancakes. Here’s a quick guide:

- Mix: a cup of flour, two spoons of sugar, a spoon of baking powder, a pinch of salt, a beaten egg, a cup of milk, and a spoon of melted butter.

- Cook on a hot griddle until bubbles form, then flip. Cook until golden.

Serve all items hot. Add fruits or jam for an extra layer of taste.

Tips for Crafting Classic Breakfast Dishes at Home

Use fresh ingredients for the best flavors. Cook eggs and pancakes on low heat to avoid burning. Keep your bacon out of hot oil until the pan is correct temp. This detail keeps it from burning. Cook items that take less time last to keep everything warm. For more great dishes, check out recipes for the best American breakfast . These small touches will improve your meal game. You’ll feel like a chef in no time!

We dived into the heart of American breakfast, from its classic dishes to the times and ways Americans enjoy their first meal. We explored regional variations, easy recipes for busy mornings, and how breakfast menus have evolved. Also, we checked out the best spots for breakfast across the USA and how to whip up a traditional American breakfast at home. My final thought? Breakfast in America is more than a meal; it's a rich tapestry of traditions, flavors, and stories waiting to start your day right.

- Social Justice

- Environment

- Health & Happiness

- Get YES! Emails

- Teacher Resources

- Give A Gift Subscription

- Teaching Sustainability

- Teaching Social Justice

- Teaching Respect & Empathy

- Student Writing Lessons

- Visual Learning Lessons

- Tough Topics Discussion Guides

- About the YES! for Teachers Program

- Student Writing Contest

Follow YES! For Teachers

Six brilliant student essays on the power of food to spark social change.

Read winning essays from our fall 2018 “Feeding Ourselves, Feeding Our Revolutions,” student writing contest.

For the Fall 2018 student writing competition, “Feeding Ourselves, Feeding Our Revolutions,” we invited students to read the YES! Magazine article, “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” by Korsha Wilson and respond to this writing prompt: If you were to host a potluck or dinner to discuss a challenge facing your community or country, what food would you cook? Whom would you invite? On what issue would you deliberate?

The Winners

From the hundreds of essays written, these six—on anti-Semitism, cultural identity, death row prisoners, coming out as transgender, climate change, and addiction—were chosen as essay winners. Be sure to read the literary gems and catchy titles that caught our eye.

Middle School Winner: India Brown High School Winner: Grace Williams University Winner: Lillia Borodkin Powerful Voice Winner: Paisley Regester Powerful Voice Winner: Emma Lingo Powerful Voice Winner: Hayden Wilson

Literary Gems Clever Titles

Middle School Winner: India Brown

A Feast for the Future

Close your eyes and imagine the not too distant future: The Statue of Liberty is up to her knees in water, the streets of lower Manhattan resemble the canals of Venice, and hurricanes arrive in the fall and stay until summer. Now, open your eyes and see the beautiful planet that we will destroy if we do not do something. Now is the time for change. Our future is in our control if we take actions, ranging from small steps, such as not using plastic straws, to large ones, such as reducing fossil fuel consumption and electing leaders who take the problem seriously.

Hosting a dinner party is an extraordinary way to publicize what is at stake. At my potluck, I would serve linguini with clams. The clams would be sautéed in white wine sauce. The pasta tossed with a light coat of butter and topped with freshly shredded parmesan. I choose this meal because it cannot be made if global warming’s patterns persist. Soon enough, the ocean will be too warm to cultivate clams, vineyards will be too sweltering to grow grapes, and wheat fields will dry out, leaving us without pasta.

I think that giving my guests a delicious meal and then breaking the news to them that its ingredients would be unattainable if Earth continues to get hotter is a creative strategy to initiate action. Plus, on the off chance the conversation gets drastically tense, pasta is a relatively difficult food to throw.

In YES! Magazine’s article, “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” Korsha Wilson says “…beyond the narrow definition of what cooking is, you can see that cooking is and has always been an act of resistance.” I hope that my dish inspires people to be aware of what’s at stake with increasing greenhouse gas emissions and work toward creating a clean energy future.

My guest list for the potluck would include two groups of people: local farmers, who are directly and personally affected by rising temperatures, increased carbon dioxide, drought, and flooding, and people who either do not believe in human-caused climate change or don’t think it affects anyone. I would invite the farmers or farm owners because their jobs and crops are dependent on the weather. I hope that after hearing a farmer’s perspective, climate-deniers would be awakened by the truth and more receptive to the effort to reverse these catastrophic trends.

Earth is a beautiful planet that provides everything we’ll ever need, but because of our pattern of living—wasteful consumption, fossil fuel burning, and greenhouse gas emissions— our habitat is rapidly deteriorating. Whether you are a farmer, a long-shower-taking teenager, a worker in a pollution-producing factory, or a climate-denier, the future of humankind is in our hands. The choices we make and the actions we take will forever affect planet Earth.

India Brown is an eighth grader who lives in New York City with her parents and older brother. She enjoys spending time with her friends, walking her dog, Morty, playing volleyball and lacrosse, and swimming.

High School Winner: Grace Williams

Apple Pie Embrace

It’s 1:47 a.m. Thanksgiving smells fill the kitchen. The sweet aroma of sugar-covered apples and buttery dough swirls into my nostrils. Fragrant orange and rosemary permeate the room and every corner smells like a stroll past the open door of a French bakery. My eleven-year-old eyes water, red with drowsiness, and refocus on the oven timer counting down. Behind me, my mom and aunt chat to no end, fueled by the seemingly self-replenishable coffee pot stashed in the corner. Their hands work fast, mashing potatoes, crumbling cornbread, and covering finished dishes in a thin layer of plastic wrap. The most my tired body can do is sit slouched on the backless wooden footstool. I bask in the heat escaping under the oven door.

As a child, I enjoyed Thanksgiving and the preparations that came with it, but it seemed like more of a bridge between my birthday and Christmas than an actual holiday. Now, it’s a time of year I look forward to, dedicated to family, memories, and, most importantly, food. What I realized as I grew older was that my homemade Thanksgiving apple pie was more than its flaky crust and soft-fruit center. This American food symbolized a rite of passage, my Iraqi family’s ticket to assimilation.

Some argue that by adopting American customs like the apple pie, we lose our culture. I would argue that while American culture influences what my family eats and celebrates, it doesn’t define our character. In my family, we eat Iraqi dishes like mesta and tahini, but we also eat Cinnamon Toast Crunch for breakfast. This doesn’t mean we favor one culture over the other; instead, we create a beautiful blend of the two, adapting traditions to make them our own.

That said, my family has always been more than the “mashed potatoes and turkey” type.

My mom’s family immigrated to the United States in 1976. Upon their arrival, they encountered a deeply divided America. Racism thrived, even after the significant freedoms gained from the Civil Rights Movement a few years before. Here, my family was thrust into a completely unknown world: they didn’t speak the language, they didn’t dress normally, and dinners like riza maraka seemed strange in comparison to the Pop Tarts and Oreos lining grocery store shelves.

If I were to host a dinner party, it would be like Thanksgiving with my Chaldean family. The guests, my extended family, are a diverse people, distinct ingredients in a sweet potato casserole, coming together to create a delicious dish.

In her article “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” Korsha Wilson writes, “each ingredient that we use, every technique, every spice tells a story about our access, our privilege, our heritage, and our culture.” Voices around the room will echo off the walls into the late hours of the night while the hot apple pie steams at the table’s center.

We will play concan on the blanketed floor and I’ll try to understand my Toto, who, after forty years, still speaks broken English. I’ll listen to my elders as they tell stories about growing up in Unionville, Michigan, a predominately white town where they always felt like outsiders, stories of racism that I have the privilege not to experience. While snacking on sunflower seeds and salted pistachios, we’ll talk about the news- how thousands of people across the country are protesting for justice among immigrants. No one protested to give my family a voice.

Our Thanksgiving food is more than just sustenance, it is a physical representation of my family ’s blended and ever-changing culture, even after 40 years in the United States. No matter how the food on our plates changes, it will always symbolize our sense of family—immediate and extended—and our unbreakable bond.

Grace Williams, a student at Kirkwood High School in Kirkwood, Missouri, enjoys playing tennis, baking, and spending time with her family. Grace also enjoys her time as a writing editor for her school’s yearbook, the Pioneer. In the future, Grace hopes to continue her travels abroad, as well as live near extended family along the sunny beaches of La Jolla, California.

University Winner: Lillia Borodkin

Nourishing Change After Tragedy Strikes

In the Jewish community, food is paramount. We often spend our holidays gathered around a table, sharing a meal and reveling in our people’s story. On other sacred days, we fast, focusing instead on reflection, atonement, and forgiveness.

As a child, I delighted in the comfort of matzo ball soup, the sweetness of hamantaschen, and the beauty of braided challah. But as I grew older and more knowledgeable about my faith, I learned that the origins of these foods are not rooted in joy, but in sacrifice.

The matzo of matzo balls was a necessity as the Jewish people did not have time for their bread to rise as they fled slavery in Egypt. The hamantaschen was an homage to the hat of Haman, the villain of the Purim story who plotted the Jewish people’s destruction. The unbaked portion of braided challah was tithed by commandment to the kohen or priests. Our food is an expression of our history, commemorating both our struggles and our triumphs.

As I write this, only days have passed since eleven Jews were killed at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. These people, intending only to pray and celebrate the Sabbath with their community, were murdered simply for being Jewish. This brutal event, in a temple and city much like my own, is a reminder that anti-Semitism still exists in this country. A reminder that hatred of Jews, of me, my family, and my community, is alive and flourishing in America today. The thought that a difference in religion would make some believe that others do not have the right to exist is frightening and sickening.

This is why, if given the chance, I would sit down the entire Jewish American community at one giant Shabbat table. I’d serve matzo ball soup, pass around loaves of challah, and do my best to offer comfort. We would take time to remember the beautiful souls lost to anti-Semitism this October and the countless others who have been victims of such hatred in the past. I would then ask that we channel all we are feeling—all the fear, confusion, and anger —into the fight.

As suggested in Korsha Wilson’s “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” I would urge my guests to direct our passion for justice and the comfort and care provided by the food we are eating into resisting anti-Semitism and hatred of all kinds.

We must use the courage this sustenance provides to create change and honor our people’s suffering and strength. We must remind our neighbors, both Jewish and non-Jewish, that anti-Semitism is alive and well today. We must shout and scream and vote until our elected leaders take this threat to our community seriously. And, we must stand with, support, and listen to other communities that are subjected to vengeful hate today in the same way that many of these groups have supported us in the wake of this tragedy.

This terrible shooting is not the first of its kind, and if conflict and loathing are permitted to grow, I fear it will not be the last. While political change may help, the best way to target this hate is through smaller-scale actions in our own communities.

It is critical that we as a Jewish people take time to congregate and heal together, but it is equally necessary to include those outside the Jewish community to build a powerful crusade against hatred and bigotry. While convening with these individuals, we will work to end the dangerous “otherizing” that plagues our society and seek to understand that we share far more in common than we thought. As disagreements arise during our discussions, we will learn to respect and treat each other with the fairness we each desire. Together, we shall share the comfort, strength, and courage that traditional Jewish foods provide and use them to fuel our revolution.

We are not alone in the fight despite what extremists and anti-semites might like us to believe. So, like any Jew would do, I invite you to join me at the Shabbat table. First, we will eat. Then, we will get to work.

Lillia Borodkin is a senior at Kent State University majoring in Psychology with a concentration in Child Psychology. She plans to attend graduate school and become a school psychologist while continuing to pursue her passion for reading and writing. Outside of class, Lillia is involved in research in the psychology department and volunteers at the Women’s Center on campus.

Powerful Voice Winner: Paisley Regester

As a kid, I remember asking my friends jokingly, ”If you were stuck on a deserted island, what single item of food would you bring?” Some of my friends answered practically and said they’d bring water. Others answered comically and said they’d bring snacks like Flamin’ Hot Cheetos or a banana. However, most of my friends answered sentimentally and listed the foods that made them happy. This seems like fun and games, but what happens if the hypothetical changes? Imagine being asked, on the eve of your death, to choose the final meal you will ever eat. What food would you pick? Something practical? Comical? Sentimental?

This situation is the reality for the 2,747 American prisoners who are currently awaiting execution on death row. The grim ritual of “last meals,” when prisoners choose their final meal before execution, can reveal a lot about these individuals and what they valued throughout their lives.

It is difficult for us to imagine someone eating steak, lobster tail, apple pie, and vanilla ice cream one moment and being killed by state-approved lethal injection the next. The prisoner can only hope that the apple pie he requested tastes as good as his mom’s. Surprisingly, many people in prison decline the option to request a special last meal. We often think of food as something that keeps us alive, so is there really any point to eating if someone knows they are going to die?

“Controlling food is a means of controlling power,” said chef Sean Sherman in the YES! Magazine article “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” by Korsha Wilson. There are deeper stories that lie behind the final meals of individuals on death row.

I want to bring awareness to the complex and often controversial conditions of this country’s criminal justice system and change the common perception of prisoners as inhuman. To accomplish this, I would host a potluck where I would recreate the last meals of prisoners sentenced to death.

In front of each plate, there would be a place card with the prisoner’s full name, the date of execution, and the method of execution. These meals could range from a plate of fried chicken, peas with butter, apple pie, and a Dr. Pepper, reminiscent of a Sunday dinner at Grandma’s, to a single olive.

Seeing these meals up close, meals that many may eat at their own table or feed to their own kids, would force attendees to face the reality of the death penalty. It will urge my guests to look at these individuals not just as prisoners, assigned a number and a death date, but as people, capable of love and rehabilitation.

This potluck is not only about realizing a prisoner’s humanity, but it is also about recognizing a flawed criminal justice system. Over the years, I have become skeptical of the American judicial system, especially when only seven states have judges who ethnically represent the people they serve. I was shocked when I found out that the officers who killed Michael Brown and Anthony Lamar Smith were exonerated for their actions. How could that be possible when so many teens and adults of color have spent years in prison, some even executed, for crimes they never committed?

Lawmakers, police officers, city officials, and young constituents, along with former prisoners and their families, would be invited to my potluck to start an honest conversation about the role and application of inequality, dehumanization, and racism in the death penalty. Food served at the potluck would represent the humanity of prisoners and push people to acknowledge that many inmates are victims of a racist and corrupt judicial system.

Recognizing these injustices is only the first step towards a more equitable society. The second step would be acting on these injustices to ensure that every voice is heard, even ones separated from us by prison walls. Let’s leave that for the next potluck, where I plan to serve humble pie.

Paisley Regester is a high school senior and devotes her life to activism, the arts, and adventure. Inspired by her experiences traveling abroad to Nicaragua, Mexico, and Scotland, Paisley hopes to someday write about the diverse people and places she has encountered and share her stories with the rest of the world.

Powerful Voice Winner: Emma Lingo

The Empty Seat

“If you aren’t sober, then I don’t want to see you on Christmas.”

Harsh words for my father to hear from his daughter but words he needed to hear. Words I needed him to understand and words he seemed to consider as he fiddled with his wine glass at the head of the table. Our guests, my grandma, and her neighbors remained resolutely silent. They were not about to defend my drunken father–or Charles as I call him–from my anger or my ultimatum.

This was the first dinner we had had together in a year. The last meal we shared ended with Charles slopping his drink all over my birthday presents and my mother explaining heroin addiction to me. So, I wasn’t surprised when Charles threw down some liquid valor before dinner in anticipation of my anger. If he wanted to be welcomed on Christmas, he needed to be sober—or he needed to be gone.

Countless dinners, holidays, and birthdays taught me that my demands for sobriety would fall on deaf ears. But not this time. Charles gave me a gift—a one of a kind, limited edition, absolutely awkward treat. One that I didn’t know how to deal with at all. Charles went home that night, smacked a bright red bow on my father, and hand-delivered him to me on Christmas morning.

He arrived for breakfast freshly showered and looking flustered. He would remember this day for once only because his daughter had scolded him into sobriety. Dad teetered between happiness and shame. Grandma distracted us from Dad’s presence by bringing the piping hot bacon and biscuits from the kitchen to the table, theatrically announcing their arrival. Although these foods were the alleged focus of the meal, the real spotlight shined on the unopened liquor cabinet in my grandma’s kitchen—the cabinet I know Charles was begging Dad to open.

I’ve isolated myself from Charles. My family has too. It means we don’t see Dad, but it’s the best way to avoid confrontation and heartache. Sometimes I find myself wondering what it would be like if we talked with him more or if he still lived nearby. Would he be less inclined to use? If all families with an addict tried to hang on to a relationship with the user, would there be fewer addicts in the world? Christmas breakfast with Dad was followed by Charles whisking him away to Colorado where pot had just been legalized. I haven’t talked to Dad since that Christmas.

As Korsha Wilson stated in her YES! Magazine article, “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” “Sometimes what we don’t cook says more than what we do cook.” When it comes to addiction, what isn’t served is more important than what is. In quiet moments, I like to imagine a meal with my family–including Dad. He’d have a spot at the table in my little fantasy. No alcohol would push him out of his chair, the cigarettes would remain seated in his back pocket, and the stench of weed wouldn’t invade the dining room. Fruit salad and gumbo would fill the table—foods that Dad likes. We’d talk about trivial matters in life, like how school is going and what we watched last night on TV.

Dad would feel loved. We would connect. He would feel less alone. At the end of the night, he’d walk me to the door and promise to see me again soon. And I would believe him.

Emma Lingo spends her time working as an editor for her school paper, reading, and being vocal about social justice issues. Emma is active with many clubs such as Youth and Government, KHS Cares, and Peer Helpers. She hopes to be a journalist one day and to be able to continue helping out people by volunteering at local nonprofits.

Powerful Voice Winner: Hayden Wilson

Bittersweet Reunion

I close my eyes and envision a dinner of my wildest dreams. I would invite all of my relatives. Not just my sister who doesn’t ask how I am anymore. Not just my nephews who I’m told are too young to understand me. No, I would gather all of my aunts, uncles, and cousins to introduce them to the me they haven’t met.

For almost two years, I’ve gone by a different name that most of my family refuses to acknowledge. My aunt, a nun of 40 years, told me at a recent birthday dinner that she’d heard of my “nickname.” I didn’t want to start a fight, so I decided not to correct her. Even the ones who’ve adjusted to my name have yet to recognize the bigger issue.

Last year on Facebook, I announced to my friends and family that I am transgender. No one in my family has talked to me about it, but they have plenty to say to my parents. I feel as if this is about my parents more than me—that they’ve made some big parenting mistake. Maybe if I invited everyone to dinner and opened up a discussion, they would voice their concerns to me instead of my parents.

I would serve two different meals of comfort food to remind my family of our good times. For my dad’s family, I would cook heavily salted breakfast food, the kind my grandpa used to enjoy. He took all of his kids to IHOP every Sunday and ordered the least healthy option he could find, usually some combination of an overcooked omelet and a loaded Classic Burger. For my mom’s family, I would buy shakes and burgers from Hardee’s. In my grandma’s final weeks, she let aluminum tins of sympathy meals pile up on her dining table while she made my uncle take her to Hardee’s every day.

In her article on cooking and activism, food writer Korsha Wilson writes, “Everyone puts down their guard over a good meal, and in that space, change is possible.” Hopefully the same will apply to my guests.

When I first thought of this idea, my mind rushed to the endless negative possibilities. My nun-aunt and my two non-nun aunts who live like nuns would whip out their Bibles before I even finished my first sentence. My very liberal, state representative cousin would say how proud she is of the guy I’m becoming, but this would trigger my aunts to accuse her of corrupting my mind. My sister, who has never spoken to me about my genderidentity, would cover her children’s ears and rush them out of the house. My Great-Depression-raised grandparents would roll over in their graves, mumbling about how kids have it easy nowadays.

After mentally mapping out every imaginable terrible outcome this dinner could have, I realized a conversation is unavoidable if I want my family to accept who I am. I long to restore the deep connection I used to have with them. Though I often think these former relationships are out of reach, I won’t know until I try to repair them. For a year and a half, I’ve relied on Facebook and my parents to relay messages about my identity, but I need to tell my own story.

At first, I thought Korsha Wilson’s idea of a cooked meal leading the way to social change was too optimistic, but now I understand that I need to think more like her. Maybe, just maybe, my family could all gather around a table, enjoy some overpriced shakes, and be as close as we were when I was a little girl.

Hayden Wilson is a 17-year-old high school junior from Missouri. He loves writing, making music, and painting. He’s a part of his school’s writing club, as well as the GSA and a few service clubs.

Literary Gems

We received many outstanding essays for the Fall 2018 Writing Competition. Though not every participant can win the contest, we’d like to share some excerpts that caught our eye.

Thinking of the main staple of the dish—potatoes, the starchy vegetable that provides sustenance for people around the globe. The onion, the layers of sorrow and joy—a base for this dish served during the holidays. The oil, symbolic of hope and perseverance. All of these elements come together to form this delicious oval pancake permeating with possibilities. I wonder about future possibilities as I flip the latkes.

—Nikki Markman, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California

The egg is a treasure. It is a fragile heart of gold that once broken, flows over the blemishless surface of the egg white in dandelion colored streams, like ribbon unraveling from its spool.

—Kaylin Ku, West Windsor-Plainsboro High School South, Princeton Junction, New Jersey

If I were to bring one food to a potluck to create social change by addressing anti-Semitism, I would bring gefilte fish because it is different from other fish, just like the Jews are different from other people. It looks more like a matzo ball than fish, smells extraordinarily fishy, and tastes like sweet brine with the consistency of a crab cake.

—Noah Glassman, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

I would not only be serving them something to digest, I would serve them a one-of-a-kind taste of the past, a taste of fear that is felt in the souls of those whose home and land were taken away, a taste of ancestral power that still lives upon us, and a taste of the voices that want to be heard and that want the suffering of the Natives to end.

—Citlalic Anima Guevara, Wichita North High School, Wichita, Kansas

It’s the one thing that your parents make sure you have because they didn’t. Food is what your mother gives you as she lies, telling you she already ate. It’s something not everybody is fortunate to have and it’s also what we throw away without hesitation. Food is a blessing to me, but what is it to you?

—Mohamed Omar, Kirkwood High School, Kirkwood, Missouri

Filleted and fried humphead wrasse, mangrove crab with coconut milk, pounded taro, a whole roast pig, and caramelized nuts—cuisines that will not be simplified to just “food.” Because what we eat is the diligence and pride of our people—a culture that has survived and continues to thrive.

—Mayumi Remengesau, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California

Some people automatically think I’m kosher or ask me to say prayers in Hebrew. However, guess what? I don’t know many prayers and I eat bacon.

—Hannah Reing, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, The Bronx, New York

Everything was placed before me. Rolling up my sleeves I started cracking eggs, mixing flour, and sampling some chocolate chips, because you can never be too sure. Three separate bowls. All different sizes. Carefully, I tipped the smallest, and the medium-sized bowls into the biggest. Next, I plugged in my hand-held mixer and flicked on the switch. The beaters whirl to life. I lowered it into the bowl and witnessed the creation of something magnificent. Cookie dough.

—Cassandra Amaya, Owen Goodnight Middle School, San Marcos, Texas

Biscuits and bisexuality are both things that are in my life…My grandmother’s biscuits are the best: the good old classic Southern biscuits, crunchy on the outside, fluffy on the inside. Except it is mostly Southern people who don’t accept me.

—Jaden Huckaby, Arbor Montessori, Decatur, Georgia

We zest the bright yellow lemons and the peels of flavor fall lightly into the batter. To make frosting, we keep adding more and more powdered sugar until it looks like fluffy clouds with raspberry seed rain.

—Jane Minus, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

Tamales for my grandma, I can still remember her skillfully spreading the perfect layer of masa on every corn husk, looking at me pitifully as my young hands fumbled with the corn wrapper, always too thick or too thin.

—Brenna Eliaz, San Marcos High School, San Marcos, Texas

Just like fry bread, MRE’s (Meals Ready to Eat) remind New Orleanians and others affected by disasters of the devastation throughout our city and the little amount of help we got afterward.

—Madeline Johnson, Spring Hill College, Mobile, Alabama

I would bring cream corn and buckeyes and have a big debate on whether marijuana should be illegal or not.

—Lillian Martinez, Miller Middle School, San Marcos, Texas

We would finish the meal off with a delicious apple strudel, topped with schlag, schlag, schlag, more schlag, and a cherry, and finally…more schlag (in case you were wondering, schlag is like whipped cream, but 10 times better because it is heavier and sweeter).

—Morgan Sheehan, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

Clever Titles

This year we decided to do something different. We were so impressed by the number of catchy titles that we decided to feature some of our favorites.

“Eat Like a Baby: Why Shame Has No Place at a Baby’s Dinner Plate”

—Tate Miller, Wichita North High School, Wichita, Kansas

“The Cheese in Between”

—Jedd Horowitz, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

“Harvey, Michael, Florence or Katrina? Invite Them All Because Now We Are Prepared”

—Molly Mendoza, Spring Hill College, Mobile, Alabama

“Neglecting Our Children: From Broccoli to Bullets”

—Kylie Rollings, Kirkwood High School, Kirkwood, Missouri

“The Lasagna of Life”

—Max Williams, Wichita North High School, Wichita, Kansas

“Yum, Yum, Carbon Dioxide In Our Lungs”

—Melanie Eickmeyer, Kirkwood High School, Kirkwood, Missouri

“My Potluck, My Choice”

—Francesca Grossberg, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

“Trumping with Tacos”

—Maya Goncalves, Lincoln Middle School, Ypsilanti, Michigan

“Quiche and Climate Change”

—Bernie Waldman, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

“Biscuits and Bisexuality”

“W(health)”

—Miles Oshan, San Marcos High School, San Marcos, Texas

“Bubula, Come Eat!”

—Jordan Fienberg, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

Get Stories of Solutions to Share with Your Classroom

Teachers save 50% on YES! Magazine.

Inspiration in Your Inbox

Get the free daily newsletter from YES! Magazine: Stories of people creating a better world to inspire you and your students.

We Finally Know Why Americans Like To Eat Sweets For Breakfast

When you think of American breakfasts, the first things that come to mind may be bacon and eggs — but there's a whole other side of the plate that's much more iconic than you might think. From fluffy pancakes doused in maple syrup, sugary cereals drowning in milk, pastries smothered in chocolate and glaze, coffees sweetened until the coffee taste is no more, and that glass of fruit juice ripened with sweeteners you don't know about — sweet breakfasts have come to reign supreme in America.

But why is that? While the rest of the world wakes up to savory bowls full of bold flavors or hearty slices of meat, why do we have a morning urge to consume sugars? We might mock the idea of dessert for breakfast , but is America unknowingly indulging in it daily?

While waking up to the smell of cinnamon rolls just seems to be the norm, there's a fascinating history as to why sweets have found a permanent home in our breakfast platter. It's a blend of America's evolving culture and economy, some genius (or sneaky?) marketing, and unfortunately, some misinformation as well. In this list, we compiled the delightful history and a bit of the science behind why Americans prefer to start their day on a sweet note. And who knows, by the end, you might look at your morning waffles in an entirely new light.

Historically, American breakfasts have always been sweet

Picture this: Before the sun has fully risen over Colonial America, families gather around their hearth, coaxing a pot of creamy cornmeal or oat — the precursor to our beloved oatmeal. Depending on where you were and what was within arm's reach, this warming breakfast could be sweetened by a dollop of butter, a drizzle of molasses, or perhaps a generous splash of maple syrup — which was produced after early settlers of the U.S. Northeast gleaned the secret of the sugar maples from their Native American neighbors. More than porridge , families also feasted on corn breads — which, back then, were called hoecakes and johnny cakes. They were the breakfast staples that graced households for generations, all the way to this day and age where they share the table with more modern breakfast bakes .

Fast forward to when the colonies unified into a single nation, the new era brought with it not only a sense of identity, but also the blessings of affordable sugar. No longer a luxury, sugar now sat on pantry shelves alongside honey, molasses, and maple syrup, resulting in an outpouring of breakfast breads. One could wake up to the aroma of Sally Lunn — a sweet, cakelike bread — or perhaps be greeted by the tempting spirals of the first rendition of cinnamon rolls and sticky buns. Thus, history shows us that America's sweet tooth didn't just appear overnight, but was formed through generations, leaving us with the sweet legacy we savor today.

Americans need quick bites and sugar spikes in the morning

In a country that prides itself on its "go-getter" mentality, time is a luxury. So, breakfast better be quick, filling, and well ... sweet. Why? There's an underlying belief that sugar delivers that much-needed energy boost — breakfast is the most important meal , right? Not to mention, that prepackaged treat is just so convenient when you're running late for school, so what if it's a bit sweet? But is that morning muffin really giving us the kick we think it does?

Sugars, being the most straightforward form of carbs, offer a tempting promise — a rapid energy lift. This is because our body processes them at breakneck speed, giving us an exhilarating, if not fleeting, energy jolt. However, this sugar high merely comes and goes. You'll feel a rapid plummet in your blood glucose levels, leaving you wanting elevenses and your concentration broken in mere hours.

Sure, a bite of a sweet pastry is nothing to fret about. But with off-the-charts calorie counts and a lack of fiber, our bodies process this sugary confection faster than our organs are wired to handle. Evolution never prepared our digestive systems for such a sugar bombardment. A significant chunk of this sugary overload gets promptly escorted into our visceral fat stores. So, while America's love for quick, sugary breakfast bites does stem from a genuine need for a quick pick-me-up, understanding sugar's role in health can help us navigate our mornings with more informed choices.

The bittersweet rise of breakfast cereals