Marriage Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on marriage.

In general, marriage can be described as a bond/commitment between a man and a woman. Also, this bond is strongly connected with love, tolerance, support, and harmony. Also, creating a family means to enter a new stage of social advancement. Marriages help in founding the new relationship between females and males. Also, this is thought to be the highest as well as the most important Institution in our society. The marriage essay is a guide to what constitutes a marriage in India.

Whenever we think about marriage, the first thing that comes to our mind is the long-lasting relationship. Also, for everyone, marriage is one of the most important decisions in their life. Because you are choosing to live your whole life with that 1 person. Thus, when people decide to get married, they think of having a lovely family, dedicating their life together, and raising their children together. The circle of humankind is like that only.

Read 500 Words Essay on Dowry System

As it is seen with other experiences as well, the experience of marriage can be successful or unsuccessful. If truth to be held, there is no secret to a successful marriage. It is all about finding the person and enjoying all the differences and imperfections, thereby making your life smooth. So, a good marriage is something that is supposed to be created by two loving people. Thus, it does not happen from time to time. Researchers believe that married people are less depressed and more happy as compared to unmarried people.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Concepts of Marriage

There is no theoretical concept of marriage. Because for everyone these concepts will keep on changing. But there are some basic concepts which are common in every marriage. These concepts are children, communication , problem-solving , and influences. Here, children may be the most considerable issue. Because many think that having a child is a stressful thing. While others do not believe it. But one thing is sure that having children will change the couple’s life. Now there is someone else besides them whose responsibilities and duties are to be done by the parents.

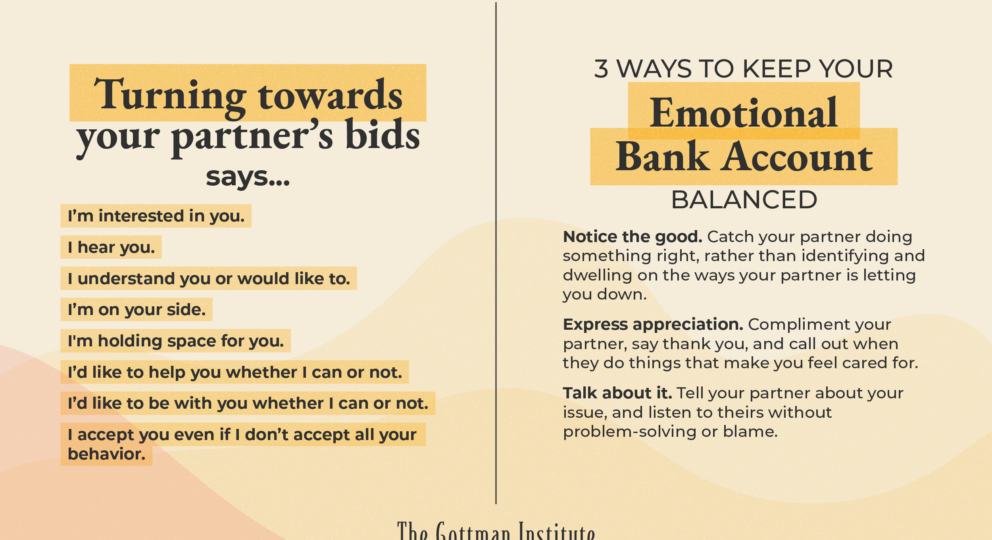

Another concept in marriage is problem-solving where it is important to realize that you can live on your own every day. Thus, it is important to find solutions to some misunderstandings together. This is one of the essential parts of a marriage. Communication also plays a huge role in marriage. Thus, the couple should act friends, in fact, be,t friends. There should be no secret between the couple and no one should hide anything. So, both persons should do what they feel comfortable. It is not necessary to think that marriage is difficult and thus it makes you feel busy and unhappy all the time.

Marriage is like a huge painting where you brush your movements and create your own love story.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Marriage and Domestic Partnership

Marriage, a prominent institution regulating sex, reproduction, and family life, is a route into classical philosophical issues such as the good and the scope of individual choice, as well as itself raising distinctive philosophical questions. Political philosophers have taken the organization of sex and reproduction to be essential to the health of the state, and moral philosophers have debated whether marriage has a special moral status and relation to the human good. Philosophers have also disputed the underlying moral and legal rationales for the structure of marriage, with implications for questions such as the content of its moral obligations and the legal recognition of same-sex marriage. Feminist philosophers have seen marriage as playing a crucial role in women’s oppression and thus a central topic of justice. In this area philosophy courts public debate: in 1940, Bertrand Russell’s appointment to an academic post was withdrawn on the grounds that the liberal views expressed in Marriage and Morals made him morally unfit for such a post. Likewise, debate over same-sex marriage has been highly charged. Unlike some contemporary issues sparking such wide interest, there is a long tradition of philosophical thought on marriage.

Philosophical debate concerning marriage extends to what marriage, fundamentally, is; therefore, Section 1 examines its definition. Section 2 sets out the historical development of the philosophy of marriage, which shapes today’s debates. Many of the ethical positions on marriage can be understood as divided on the question of whether marriage should be defined contractually by the spouses or by its institutional purpose, and they further divide on whether that purpose necessarily includes procreation or may be limited to the marital love relationship. Section 3 taxonomizes ethical views of marriage accordingly. Section 4 will examine rival political understandings of marriage law and its rationale. Discussion of marriage has played a central role in feminist philosophy; Section 5 will outline the foremost critiques of the institution.

1. Defining Marriage

2. understanding marriage: historical orientation, 3.1 contractual views, 3.2 institutional views, 4.1 marriage and legal contract, 4.2 the rationale of marriage law, 4.3 same-sex marriage, 4.4 arguments for marriage reform, 5.1 feminist approaches, 5.2 the queer critique, contemporary works, historical works, other internet resources, related entries.

‘Marriage’ can refer to a legal contract and civil status, a religious rite, and a social practice, all of which vary by legal jurisdiction, religious doctrine, and culture. History shows considerable variation in marital practices: polygyny has been widely practiced, some societies have approved of extra-marital sex and, arguably, recognized same-sex marriages, and religious or civil officiation has not always been the norm (Boswell 1994; Mohr 2005, 62; Coontz 2006). More fundamentally, while the contemporary Western ideal of marriage involves a relationship of love, friendship, or companionship, marriage historically functioned primarily as an economic and political unit used to create kinship bonds, control inheritance, and share resources and labor. Indeed, some ancients and medievals discouraged ‘excessive’ love in marriage. The Western ‘love revolution’ in marriage dates popularly to the 18 th century (Coontz 2006, Part 3). The understanding of marriage as grounded in individual choice and romantic love reflects historically and culturally situated beliefs and practices. Most notably, the aspect of consent or voluntary entry - often taken to be crucial to marriage (Cott 2000) - is challenged where practices of forced or child marriage are prevalent (Narayan 1997; Bhandary 2018). Arranged marriage, which is compatible with the consent of the spouses, prioritizes caregiving and economic aspects of the institution over romantic love (Bhandary 2018).

The global variety of marriage practices and law is difficult to encapsulate: notable variations in law include recognition of same-sex marriage, polygamy, and ‘common-law’ marriage, restrictions on marriages between members of the same family or of different social castes, the existence of civil marriage, practices of arranged, forced, or child marriage, and women’s rights within marriage (see Moses 2018 for an entry into the literature on these differences), as well as cultural and religious practices of temporary marriage (Shrage 2013, Nolan 2016) or polyamorous marriage (Brake 2018). Religious, cultural, and philosophical traditions also shape ideals of marriage. For instance, Xiaorong Li writes that “Confucian ideals of family, society, and women’s role” influence expectations of marriage in China (Li 1995, 413). However, scholarship on such differences must be careful to avoid misrepresentation (see for example discussion of misleading Western accounts of ‘sati’ and dowry-murder in India in Narayan 1997).

Ethical and political questions regarding marriage are sometimes answered by appeal to the definition of marriage. But the historical and cultural variation in marital practices has prompted some philosophers to argue that marriage is a ‘family resemblance’ concept, with no essential purpose or structure (Wasserstrom 1974; see also the interesting discussion of whether the many different practices identified by anthropologists as marriage should be counted as marriages in Nolan, forthcoming). If marriage has no essential features, then one cannot appeal to definition to justify particular legal or moral obligations. For instance, if monogamy is not an essential feature of marriage, then one cannot appeal to the definition of marriage to justify a requirement that legal marriage be monogamous. To a certain extent, the point that actual legal or social definitions cannot settle the question of what features marriage should have is just. First, past applications of a term need not yield necessary and sufficient criteria for applying it: ‘marriage’ (like ‘citizen’) may be extended to new cases without thereby changing its meaning (Mercier 2001). Second, appeal to definition may be uninformative: for example, legal definitions are sometimes circular, defining marriage in terms of spouses and spouses in terms of marriage (Mohr 2005, 57). Third, appeal to an existing definition in the context of debate over what the law of marriage, or its moral obligations, should be risks begging the question: in debate over same-sex marriage, for example, appeal to the current legal definition begs the normative question of what the law should be. However, this point also tells against the argument for the family resemblance view of marriage, as the variation of marital forms in practice does not preclude the existence of a normatively ideal form. Thus, philosophers who defend an essentialist definition of marriage offer normative definitions, which appeal to fundamental ethical or political principles. Defining marriage must depend on, rather than precede, ethical and political inquiry.

Setting the agenda for contemporary debate, ancient and medieval philosophers raised recurring themes in the philosophy of marriage: the relation between marriage and the state, the role of sex and procreation in marriage, and the gendered nature of spousal roles. Their works reflect evolving, and overlapping, ideas of marriage as an economic or procreative unit, a religious sacrament, a contractual association, and a relationship of mutual support.

In his depiction of the ideal state, Plato (427–347 BCE) described a form of marriage contrasting greatly with actual marriage practices of his time. He argued that, just as male and female watchdogs perform the same duties, men and women should work together, and, among Guardians, ‘wives and children [should be held] in common’ ( The Republic , ca. 375–370 BCE, 423e–424a). To orchestrate eugenic breeding, temporary marriages would be made at festivals, where matches, apparently chosen by lot, would be secretly arranged by the Rulers. Resulting offspring would be taken from biological parents and reared anonymously in nurseries. Plato’s reason for this radical restructuring of marriage was to extend family sympathies from the nuclear family to the state itself: the abolition of the private family was intended to discourage private interests at odds with the common good and the strength of the state ( ibid ., 449a-466d; in Plato’s Laws , ca. 355–47 BCE, private marriage is retained but still designed for public benefit).

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) sharply criticized this proposal as unworkable. On his view, Plato errs in assuming that the natural love for one’s own family can be transferred to all fellow-citizens. The state arises from component parts, beginning with the natural procreative union of male and female. It is thus a state of families rather than a family state, and its dependence on the functioning of individual households makes marriage essential to political theory ( Politics , 1264b). The Aristotelian idea that the stability of society depends on the marital family influenced Hegel, Rawls, and Sandel, among others. Aristotle also disagreed with Plato on gender roles in marriage, and these views too would prove influential. Marriage, he argued, is properly structured by gender: the husband, “fitter for command,” rules. The sexes express their excellences differently: “the courage of a man is shown in commanding, of a woman in obeying,” a complementarity which promotes the marital good ( Politics , ca. 330 BCE, 1253b, 1259b, 1260a; Nicomachean Ethics , ca. 325 BCE, 1160–62).

In contrast to the ancients, whose philosophical discussion of sex and sexual love was not confined to marriage, Christian philosophers introduced a new focus on marriage as the sole permissible context for sex, marking a shift from viewing marriage as primarily a political and economic unit. St. Augustine (354–430), following St. Paul, condemns sex outside marriage and lust within it. “[A]bstinence from all sexual union is better even than marital intercourse performed for the sake of procreating,” and the unmarried state is best of all ( The Excellence of Marriage , ca. 401, §6, 13/15). But marriage is justified by its goods: “children, fidelity [between spouses], and sacrament.” Although procreation is the purpose of marriage, marriage does not morally rehabilitate lust. Instead, the reason for the individual marital sexual act determines its permissibility. Sex for the sake of procreation is not sinful, and sex within marriage solely to satisfy lust is a pardonable (venial) sin. As marital sex is preferable to “fornication” (extra-marital sex), spouses owe the “marriage debt” (sex) to protect against temptation, thereby sustaining mutual fidelity ( Marriage and Desire , Book I, ca. 418–19, §7, 8, 17/19, 14/16).

St. Thomas Aquinas (ca. 1225–1274) grounded concurring judgments about sexual morality in natural law, explicating marriage in terms of basic human goods, including procreation and fidelity between spouses (Finnis 1997). Monogamous marriage, as the arrangement fit for the rearing of children, “belong[s] to the natural law.” Monogamous marriage secures paternal guidance, which a child needs; fornication is thus a mortal sin because it “tends to injure the life of the offspring.” (Aquinas rejects polygamy on similar grounds while, like Augustine, arguing that it was once permitted to populate the earth.) Marital sex employs the body for its purpose of preserving the species, and pleasure may be a divinely ordained part of this. Even within marriage, sex is morally troubling because it involves “a loss of reason,” but this is compensated by the goods of marriage ( Summa Theologiae , unfinished at Aquinas’ death, II-II, 153, 2; 154, 2). Among these goods, Aquinas emphasizes the mutual fidelity of the spouses, including payment of the “marriage debt” and “partnership of a common life”—a step towards ideas of companionate marriage ( Summa Theologiae, Supp. 49, 1).

Indeed, we see indications of discontent with the economic model of marriage a century earlier in the letters of Héloïse (ca. 1100–1163) to Abelard (1079–1142). Héloïse attacks marriage, understood as an economic transaction, arguing that a woman marrying for money or position deserves “wages, not gratitude” and would “prostitute herself to a richer man, if she could.” In place of this economic relation she praises love, understood on a Ciceronian model of friendship: the “name of wife may seem more sacred or more binding, but sweeter for me will always be the word friend ( amica ), or, if you will permit me, that of concubine or whore” (Abelard and Héloïse, Letters , ca. 1133–1138, 51–2). The relation between love and marriage will continue to preoccupy later philosophers. Do marital obligations and economic incentives threaten love, as Héloïse suggested? (Cave 2003, Card 1996) As Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855) dramatically suggests in The Seducer’s Diary , are the obligations of marriage incompatible with romantic and erotic love? Or, instead, does marital commitment uniquely enable spousal love, as Aquinas suggested? (Finnis 1997; cf. Kierkegaard’s Judge William’s defense of marriage [ Either/Or , 1843, vol. 2].)

Questions of the relation between love and marriage emerge from changing understandings of the role of marriage; in the early modern era, further fault lines appear as new understandings of human society conflict with the traditional structure of marriage. For Aristotle, Augustine, and Aquinas, marriage was unproblematically structured by sexual difference, and its distinctive features explained by nature or sacrament. But in the early modern era, as doctrines of equal rights and contract appeared, a new ideal of relationships between adults as free choices between equals appeared. In this light, the unequal and unchosen content of the marriage relationship raised philosophical problems. Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) acknowledged that his arguments for rough equality among humans apply to women: “whereas some have attributed the dominion [over children] to the man only, as being of the more excellent sex; they misreckon in it. For there is not always that difference of strength, or prudence between the man and the woman, as that the right can be determined without war.” Nonetheless, Hobbes admits that men dominate in marriage, which he explains (inadequately) thus: “for the most part commonwealths have been erected by the fathers, not by the mothers of families” ( Leviathan , 1651, Ch. 20; Okin 1979, 198–199, Pateman 1988, 44–50).

Likewise, defending marital hierarchy posed a problem for John Locke (1632–1704). Locke ties his rejection of political patriarchy to a rejection of the patriarchal family, arguing that marriage, like the state, rests on consent, not natural hierarchy; marriage is a “voluntary compact.” But Locke fails to follow this reasoning consistently, for Lockean marriage remains hierarchical: in cases of conflict, “the rule … naturally falls to the man’s as the abler and stronger.” Ceding decision-making power to one party on the basis of a presumed natural hierarchy creates an internal tension in Locke’s views ( The Second Treatise of Government , 1690, §77, 81, 82; Okin 1979, 199–200). This inconsistency prompted Mary Astell’s (1666–1731) response: “If all Men are born free , how is it that all women are born slaves? as they must be if the being subjected to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, arbitrary Will of Men, be the perfect Condition of Slavery ?” (“Reflections upon Marriage,” 1700, 18) Similar tensions arise for Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), whose treatise on education, Émile , describes the unequal status of Émile’s wife, Sophie. Her education, a template for all women’s, prepares her only to please and serve her husband and rear children. Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1798) attacked Rousseau’s views on women’s nature, education, and marital inequality in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (see also Okin 1979, Chapter 6).

The contractual understanding of marriage prompts the question as to why marital obligations should be fixed other than by spousal agreement. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) combined a contractual account of marriage with an Augustinian preoccupation with sexual morality to argue that the distinctive content of the marriage contract was required to make sex permissible. In Kant’s view, sex involves morally problematic objectification, or treatment of oneself and other as a mere means. The marriage right, a “right to a person akin to a right to a thing,” gives spouses “lifelong possession of each other’s sexual attributes,” a transaction supposed to render sex compatible with respect for humanity: “while one person is acquired by the other as if it were a thing , the one who is acquired acquires the other in turn; for in this way each reclaims itself and restores its personality.” But while these rights, according to Kant, make sex compatible with justice, married sex is not clearly virtuous unless procreation is a possibility ( Metaphysics of Morals , 1797–98, Ak 6:277–79, 6:424–427). Kant’s account of sexual objectification has had wide influence—from feminists to new natural lawyers. More surprisingly, given his views on gender inequality and the wrongness of same-sex sexual activity, Kant’s account of marriage has been sympathetically reconstructed by feminists and defenders of same-sex marriage drawn by Kant’s focus on equality, reciprocity, and the moral rehabilitation of sex within marriage (Herman 1993, Altman 2010, Papadaki 2010). Kant interestingly suggests that morally problematic relationships can be reconstructed through equal juridical rights, but how such reconstruction occurs is puzzling (Herman 1993, Brake 2005). Among other things, it is difficult to see how Kant’s insistence on equal marriage rights can be reconciled with his views on gender inequality (Sticker 2020).

Characteristically, G. W. F. Hegel’s (1770–1831) account of marriage synthesizes the preceding themes. Hegel returns to Aristotle’s understanding of (nuclear) marriage as the foundation of a healthy state, while explicating its contribution in terms of spousal love. Hegel criticized Kant’s reduction of marriage to contract as “disgraceful” because spouses begin “from the point of view of contract—i.e. that of individual personality as a self-sufficient unit— in order to supersede it .” They “consent to constitute a single person and to give up their natural and individual personalities within this union.” The essence of marriage is ethical love, “the consciousness of this union as a substantial end, and hence in love, trust, and the sharing of the whole of individual existence.” Ethical love is not, like sexual love, contingent: “Marriage should not be disrupted by passion, for the latter is subordinate to it” ( Elements of the Philosophy of Right , 1821, §162–63, 163A).

Like his predecessors, Hegel must justify the distinctive features of marriage, and in particular, why, if it is the ethical love relationship which is ethically significant, formal marriage is necessary. Hegel’s contemporary Friedrich von Schlegel had argued that love can exist outside marriage—a point which Hegel denounced as the argument of a seducer! For Hegel, ethical love depends on publicly assuming spousal roles which define individuals as members in a larger unit. Such unselfish membership links marriage and the state. Marriage plays an important role in Hegel’s system of right, which culminates in ethical life, the customs and institutions of society: family, civil society, and the state. The role of marriage is to prepare men to relate to other citizens as sharers in a common enterprise. In taking family relationships as conditions for good citizenship, Hegel follows Aristotle and influences Rawls and Sandel; it is also notable that he takes marriage as a microcosm of the state.

Kant and Hegel attempted to show that the distinctive features of marriage could be explained and justified by foundational normative principles. In contrast, early feminists argued that marital hierarchy was simply an unjust remnant of a pre-modern era. John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) argued that women’s subordination within marriage originated in physical force—an anomalous holdover of the ‘law of the strongest’. Like Wollstonecraft in her 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Woman , Mill compared marriage and slavery: under coverture wives had no legal rights, little remedy for abuse, and, worse, were required to live in intimacy with their ‘masters’. This example of an inequality based on force had persisted so long, Mill argued, because all men had an interest in retaining it. Mill challenged the contractual view that entry into marriage was fully voluntary for women, pointing out that their options were so limited that marriage was “only Hobson’s choice, ‘that or none’” ( The Subjection of Women , 1869, 29). He also challenged the view that women’s nature justified marital inequality: in light of different socialization of girls and boys, there was no way to tell what woman’s nature really was. Like Wollstonecraft, Mill described the ideal marital relationship as one of equal friendship (Abbey and Den Uyl, 2001). Such marriages would be “schools of justice” for children, teaching them to treat others as equals. But marital inequality was a school of injustice, teaching boys unearned privilege and corrupting future citizens. The comparison of marriage with slavery has been taken up by more recent feminists (Cronan 1973), as has the argument that marital injustice creates unjust citizens (Okin 1994).

Marxists also saw marriage as originating in ancient exercises of force and as continuing to contribute to the exploitation of women. Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) argued that monogamous marriage issued from a “ world historical defeat of the female sex ” (Engels 1884, 120). Exclusive monogamy “was not in any way the fruit of individual sex love, with which it had nothing whatever to do … [but was based on] economic conditions—on the victory of private property over primitive, natural communal property” ( ibid ., 128). Monogamy allowed men to control women and reproduction, thereby facilitating the intergenerational transfer of private property by producing undisputed heirs. Karl Marx (1818–83) argued that abolishing the private family would liberate women from male ownership, ending their status “as mere instruments of production” ( The Communist Manifesto , Marx 1848, 173). The Marxist linking of patriarchy and capitalism, in particular its understanding of marriage as an ownership relation ideologically underpinning the capitalist order, has been especially influential in feminist thought (Pateman 1988, cf. McMurtry 1972).

3. Marriage and Morals

The idea that marriage has a special moral status and entails fixed moral obligations is widespread—and philosophically controversial. Marriage is a legal contract, although an anomalous one (see 4.1); as the idea of it as a contract has taken hold, questions have arisen as to how far its obligations should be subject to individual choice. The contractual view of marriage implies that spouses can choose marital obligations to suit their interests. However, to some, the value of marriage consists precisely in the limitations it sets on individual choice in the service of a greater good: thus, Hegel commented that arranged marriage is the most ethical form of marriage because it subordinates personal choice to the institution. The institutional view holds that the purpose of the institution defines its obligations, taking precedence over spouses’ desires, either in the service of a procreative union or to protect spousal love, in the two most prominent forms of this view. These theories have implications for the moral status of extra-marital sex and divorce, as well as the purpose of marriage.

On the contractual view, the moral terms and obligations of marriage are understood as promises between spouses. Their content is supplied by surrounding social and legal practices, but their promissory nature implies that parties to the promise can negotiate the terms and release each other from marital obligations.

One rationale for treating marital obligations as such promises might be thought to be the voluntaristic account of obligation. On this view, all special obligations (as opposed to general duties) are the result of voluntary undertakings; promises are then the paradigm of special obligations (see entry on Special Obligations). Thus, whatever special obligations spouses have to one another must originate in voluntary agreement, best understood as promise. We will return to this below. A second rationale is the assumption that existing marriage practices are morally arbitrary, in the sense that there is no special moral reason for their structure. Further, there are diverse social understandings of marriage. If the choice between them is morally arbitrary, there is no moral reason for spouses to adopt one specific set of marital obligations; it is up to spouses to choose their terms. Thus, the contractual account depends upon the assumption that there is no decisive moral reason for a particular marital structure.

On the contractual account, not just any contracts count as marriages. The default content of marital promises is supplied by social and legal practice: sexual exclusivity, staying married, and so on. But it entails that spouses may release one another from these moral obligations. For example, extra-marital sex has often been construed as morally wrong by virtue of promise-breaking: if spouses promise sexual exclusivity, extra-marital sex breaks a promise and is thereby prima facie wrong. However, if marital obligations are simply promises between the spouses, then the parties can release one another, making consensual extra-marital sex permissible (Wasserstrom 1974). Marriage is also sometimes taken to involve a promise to stay married. This seems to make unilateral divorce morally problematic, as promisors cannot release themselves from promissory obligations (Morse 2006). But standard conditions for overriding promissory obligations, such as conflict with more stringent moral duties, inability to perform, or default by the other party to a reciprocal promise would permit at least some unilateral divorces (Houlgate 2005, Chapter 12). Some theorists of marriage have suggested that marital promises are conditional on enduring love or fulfilling sex (Marquis 2005, Moller 2003). But this assumption is at odds with the normal assumption that promissory conditions are to be stated explicitly.

Release from the marriage promise is not the only condition for permissible divorce on the contractual view. Spouses may not be obligated to one another to stay married—but they may have parental duties to do so: if divorce causes avoidable harm to children, it is prima facie wrong (Houlgate 2005, Chapter 12, Russell 1929, Chapter 16). However, in some cases divorce will benefit the child—as when it is the means to escape abuse. A vast empirical literature disputes the likely effects of divorce on children (Galston 1991, 283–288, Young 1995). What is notable here, philosophically, is that this moral reason against divorce is not conceived as a spousal, but a parental, duty.

Marriage is widely taken to have an amatory core, suggesting that a further marital promise is a promise to love, as expressed in wedding vows ‘to love and cherish’. But the possibility of such promises has met with skepticism. If one cannot control whether one loves, the maxim that ‘ought implies can’ entails that one cannot promise to love. One line of response has been to suggest that marriage involves a promise not to feel but to behave a certain way—to act in ways likely to sustain the relationship. But such reinterpretations of the marital promise face a problem: promises depend on what promisors intend to promise—and presumably most spouses do not intend to promise mere behavior (Martin 1993, Landau 2004, Wilson 1989, Mendus 1984, Brake 2012, Chapter 1; see also Kronqvist 2011). However, developing neuroenhancement technology promises to bring love under control through “love drugs” which would produce bonding hormones such as oxytocin. While the use of neuroenhancement to keep one’s vows raises questions about authenticity and the nature of love (as well as concerns regarding its use in abusive relationships), it is difficult to see how such technology morally differs from other love-sustaining devices such as romantic dinners—except that it is more likely to be effective (Savulescu and Sandberg 2008).

One objection to the contractual account is that, without appeal to the purpose of the institution, there is no reason why not just any set of promises count as marriage (Finnis 2008). The objection continues that the contractual account cannot explain the point of marriage. Some marriage contractualists accept this implication. According to the “bachelor’s argument,” marriage is irrational: chances of a strongly dis-preferred outcome (a loveless marriage) are too high (Moller 2003). Defenders of the rationality of marriage have replied that marital obligations are rational because they help agents to secure their long-term interests in the face of passing desires (Landau 2004). From the institutional perspective, evaluating the rationality of marriage thus, in terms of fulfilling subjective preferences, clashes with the tradition of viewing it as uniquely enabling certain objective human goods; however, a positive case must be made for the latter view.

Another objection to the contractual view concerns voluntarism. Critics of the voluntarist approach to the family deny that family morality is exhausted by voluntary obligations (Sommers 1989). Voluntarist conceptions of the family conflict with common-sense intuitions that there are unchosen special duties between family members, such as filial duties. However, even if voluntarism is false, this does not suffice to establish special spousal duties. On the other hand, voluntarism alone does not entail the contractual view, for it does not entail that spouses can negotiate the obligations of marriage or that the obligations be subject to release, only that spouses must agree to them. Voluntarism, in other words, need not extend to the choice of marital obligations and hence need not entail the contractual account. The contractual account depends on denying that there is decisive moral reason for marriage to incorporate certain fixed obligations. Let us turn to the case that there is such reason.

The main theoretical alternatives to the contractual view hold that marital obligations are defined by the purpose of the institution and that spouses cannot alter these institutional obligations (much like the professional moral obligations of a doctor; to become a doctor, one must voluntarily accept the role and its obligations, and one cannot negotiate the content of these obligations). The challenge for institutional views is to defend such a view of marriage, explaining why spouses may not jointly agree to alter obligations associated with marriage. Kant confronted this question, arguing that special marital rights were morally necessary for permissible sex. His account of sexual objectification has influenced a prominent contemporary rival to the contractual view—the new natural law view, which takes procreation as essential to marriage. A second widespread approach focuses solely on love as the defining purpose of marriage.

3.2.1 New Natural Law: Marriage as Procreative Union

Like Kant, the new natural law account of marriage focuses on the permissible exercise of sexual attributes; following Aquinas, it emphasizes the goods of marriage, which new natural lawyers, notably John Finnis (cf. George 2000, Grisez 1993, Lee 2008), identify as reproduction and fides —roughly, marital friendship (see entry on The Natural Law Tradition in Ethics). Marriage is here taken to be the institution uniquely apt for conceiving and rearing children by securing the participation of both parents in an ongoing union. The thought is that there is a distinctive marital good related to sexual capacities, consisting in procreation and fides , and realizable only in marriage. Within marriage, sex may be engaged in for the sake of the marital good. Marital sex need not result in conception to be permissible; it is enough that it is open towards procreation and expresses fides . The view does not entail that it is wrong to take pleasure in sex, for this can be part of the marital good.

However, sex outside marriage (as defined here) cannot be orientated toward the marital good. Furthermore, sexual activity not orientated toward this good—including same-sex activity, masturbation, contracepted sex, sex without marital commitment (even within legal marriage)—is valueless; it does not instantiate any basic good. Furthermore, such activity is impermissible because it violates the basic good of marriage. Marital sex is thought to instantiate the good of marriage. By contrast, non-marital sex is thought to treat sexual capacities instrumentally—using them merely for pleasure. (It is here that the account is influenced by Kant.) Non-marital sex violates the good of marriage by treating sexual capacities in a way contrary to that good. Furthermore, for an agent merely to condone non-marital sex damages his or her relation to the marital good, for even a hypothetical willingness to treat sex instrumentally precludes proper marital commitment (Finnis 1997, 120).

As Finnis emphasizes, one feature of the new natural law account of marriage is that the structure of marriage can be fully explained by its purpose. Marriage is between one man and one woman because this is the unit able to procreate without third-party assistance; permanence is required to give children a lifelong family. Finnis charges, as noted above, that accounts which do not ground marriage in this purpose have no theoretical reason to resist the extension of marriage to polygamy, incest, and bestiality (Finnis 1995). As all non-marital sex fails to instantiate basic goods, there is no way morally to distinguish these different relations.

A further point concerns law: to guide citizens’ judgments and choices towards the relationship in which they can uniquely achieve the marital good, the state should endorse marriage, as understood on this view, and not recognize same-sex relationships as marriages. However, it might be asked whether this is an effective way to guide choice, and whether state resources might be better spent promoting other basic human goods. Moreover, as the argument equally implies a state interest in discouraging contraception, divorce, and extra-marital sex, the focus on same-sex marriage appears arbitrary (Garrett 2008, Macedo 1995). This objection is a specific instance of a more general objection: this account treats sex and the marital good differently than it does the other basic human goods. Not only is less attention paid to promoting those goods legally (and discouraging behavior contrary to them), but the moral principle forbidding action contrary to basic human goods is not consistently applied elsewhere—for example, to eating unhealthily (Garrett 2008).

A second objection attacks the claim that non-marital sex cannot instantiate any basic human goods. This implausibly consigns all non-marital sex (including all contracepted sex) to the same value as anonymous sex, prostitution, or masturbation (Macedo 1995, 282). Plausibly, non-marital sex can instantiate goods such as “pleasure, communication, emotional growth, personal stability, long-term fulfillment” (Corvino 2005, 512), or other basic human goods identified by the new natural law account, such as knowledge, play, and friendship (Garrett 2008; see also Blankschaen 2020).

A third objection is related. The view seems to involve a double standard in permitting infertile opposite-sex couples to marry (Corvino 2005; Macedo 1995). The new natural lawyers have responded that penile-vaginal sex is reproductive in type, even if not in effect, while same-sex activity can never be reproductive in type (Finnis 1997, cf. George 2000, Lee 2008). Reproductive-type sex can be oriented towards procreation even if not procreative in effect. But it is unclear how individuals who know themselves to be infertile can have sex for the reason of procreation (Macedo 1995, Buccola 2005). Ultimately, to differentiate infertile heterosexual couples from same-sex couples, new natural lawyers invoke complementarity between men and women as partners and parents. Thus, the defense of this account of marriage turns on a controversial view of the nature and importance of sexual difference (Finnis 1997, Lee 2008).

A related, influential argument focuses on the definition of marriage. This argues that marriage is necessarily between one man and one woman because it involves a comprehensive union between spouses, a unity of lives, minds, and bodies. Organic bodily union requires being united for a biological purpose, in a procreative-type act (Girgis, et al., 2010). Like the new natural law arguments, this has raised questions as to why only, and all, different-sex couples, even infertile ones, can partake in procreative-type acts, and why bodily union has special significance (Arroyo 2018, Johnson 2013).

While much discussion of new natural law accounts of marriage oscillates between attacking and defending the basis in biological sex difference, some theorists sympathetic to new natural law attempt to avoid the Scylla of rigid biological restrictions and the Charybdis of liberal “plasticity” regarding marriage (Goldstein 2011). Goldstein, for one, offers an account of marriage as a project generated by the basic good of friendship; while this project includes procreation as a core feature, the institution of marriage has, on this account, a compensatory power, meaning that the institution itself can compensate for failures such as inability to procreate. Such an account grounds marriage in the new natural law account of flourishing, but it also allows the extension to same-sex marriage without, according to Goldstein, permitting other forms such as polygamy.

3.2.2 Marriage as Protecting Love

A second widespread (though less unified) institutional approach to marriage appeals to the ideal marital love relationship to define the structure of marriage. This approach, in the work of different philosophers, yields a variety of specific prescriptions, on, for example, whether marital love (or committed romantic love in general) requires sexual difference or sexual exclusivity (Scruton 1986, 305–311, Chapter 11, Halwani 2003, 226–242, Chartier 2016). Some, but not all, proponents explicitly argue that the marital love relationship is an objective good (Scruton 1986, Chapter 11, 356–361, Martin 1993). These views, however, all take the essential feature, and purpose, of marriage to be protecting a sexual love relationship. The thought is that marriage helps to maintain and support a relationship either in itself valuable, or at least valued by the parties to it.

On this approach, the structure of marriage derives from the behavior needed to maintain such a relationship. Thus marriage involves a commitment to act for the relationship as well as to exclude incompatible options—although there is controversy over what specific policies these general commitments entail. To take an uncontroversial example, marriage creates obligations to perform acts which sustain love, such as focusing on the beloved’s good qualities (Landau 2004). More controversially, some philosophers argue that sustaining a love relationship requires sexual exclusivity. The thought is that sexual activity generates intimacy and affection, and that objects of affection and intimacy will likely come into competition, threatening the marital relationship. Another version focuses on the emotional harm, and consequent damage to the relationship, caused by sexual jealousy. Thus, due to the psychological conditions required to maintain romantic love, marriage, as a love-protecting institution, generates obligations to sexual exclusivity (Martin 1993, Martin 1994, Scruton 1986, Chapter 11, 356–361, Steinbock 1986). However, philosophers dispute the psychological conditions needed to maintain romantic love. Some argue that casual extra-marital sex need not create competing relationships or trigger jealousy (Halwani 2003, 235; Wasserstrom 1974). Indeed, some have even argued that extra-marital sex, or greater social tolerance thereof, could strengthen otherwise difficult marriages (Russell 1929, Chapter 16), and some polyamorists (those who engage in multiple sex or love relationships) claim that polyamory allows greater honesty and openness than exclusivity (Emens 2004). Other philosophers have treated sexual fidelity as something of a red herring, shifting focus to other qualities of an ideal relationship such as attentiveness, warmth, and honesty, or a commitment to justice in the relationship (Martin 1993, Kleingeld 1998).

Views understanding marriage as protecting love generate diverse conclusions regarding its obligations. But such views share two crucial assumptions: that marriage has a role to play in creating a commitment to a love relationship, and that such commitments may be efficacious in protecting love (Cave 2003, Landau 2004, Martin 1993, Martin 1994, Mendus 1984, Scruton 1986, 356–361). However, both of these assumptions may be questioned. First, even if commitment can protect a love relationship, why must such a commitment be made through a formal marriage? If it is possible to maintain a long-term romantic relationship outside marriage, the question as to the point of marriage re-emerges: do we really need marriage for love? May not the legal and social supports of marriage, indeed, trap individuals in a loveless marriage or themselves corrode love by associating it with obligation? (Card 1996, Cave 2003; see also Gheaus 2016) Second, can commitment, within or without marriage, really protect romantic love? High divorce rates would seem to suggest not. Of course, even if, as discussed in 3.1, agents cannot control whether they love, they can make a commitment to act in ways protective of love (Landau 2004, Mendus 1984). But this returns us the difficulty, suggested by the preceding paragraph, of knowing how to protect love!

Reflecting the difficulty of generating specific rules to protect love, many such views have understood the ethical content of marriage in terms of virtues (Steinbock 1991, Scruton 1986, Chapter 11, 356–361). The virtue approach analyzes marriage in terms of the dispositions it cultivates, an approach which, by its reference to emotional states, promises to explain the relevance of marriage to love. However, such approaches must explain how marriage fosters virtues (Brake 2012). Some virtue accounts cite the effects of its social status: marriage triggers social reactions which secure spousal privacy and ward off the disruptive attention of outsiders (Scruton 1986, 356–361). Its legal obligations, too, can be understood as Ulysses contracts [ 1 ] : they protect relationships when spontaneous affection wavers, securing agents’ long-term commitments against passing desires. Whether or not such explanations ultimately show that marital status and obligations can play a role in protecting love, the general focus on ideal marital love relationships may be characterized as overly idealistic when contrasted with problems in actual marriages, such as spousal abuse (Card 1996). This last point suggests that moral analysis of marriage cannot be entirely separated from political and social inquiry.

4. The Politics of Marriage

In political philosophy, discussions of marriage law invoke diverse considerations, reflecting the theoretical orientations of contributors to the debate. This discussion will set out the main considerations invoked in arguments concerning the legal structure of marriage.

Marriage is a legal contract, but it has long been recognized to be an anomalous one. Until the 1970s in the U.S., marriage law restricted divorce and defined the terms of marriage on the basis of gender. Marking a shift towards greater alignment of marriage with contractual principles of individualization, marriage law no longer imposes gender-specific obligations, it allows pre-nuptial property agreements, and it permits easier exit through no-fault divorce. But marriage remains (at least in U.S. federal law) an anomalous contract: “there is no written document, each party gives up its right to self-protection, the terms of the contract cannot be re-negotiated, neither party need understand its terms, it must be between two and only two people, and [until 2015, when the US Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges established same-sex marriage in the US] these two people must be one man and one woman” (Kymlicka 1991, 88).

Proponents of the contractualization, or privatization, of marriage have argued that marriage should be brought further into line with the contractual paradigm. A default assumption for some liberals, as for libertarians, is that competent adults should be legally permitted to choose the terms of their interaction. In a society characterized by freedom of contract, restrictions on entry to or exit from marriage, or the content of its legal obligations, appear to be an illiberal anomaly. Full contractualization would imply that there should be no law of marriage at all—marriage officiation would be left to religions or private organizations, with the state enforcing whatever private contracts individuals make and otherwise not interfering (Vanderheiden 1999, Sunstein and Thaler 2008, Chartier 2016; for a critique of contractualization, see Chambers 2016). The many legal implications of marriage for benefit entitlements, inheritance, taxation, and so on, can also be seen as a form of state interference in private choice. By conferring these benefits, as well as merely recognizing marriage as a legal status, the state encourages the relationships thereby formalized (Waldron 1988–89, 1149–1152). [ 2 ]

Marriage is the basis for legal discrimination in a number of contexts; such discrimination requires justification, as does the resource allocation involved in providing marital benefits (Cave 2004, Vanderheiden 1999). In the absence of such justification, providing benefits through marriage may treat the unmarried unjustly, as their exclusion from such benefits would then be arbitrary (Card 1996). Thus, there is an onus to provide a rationale justifying such resource allocations and legal discrimination on the basis of marriage, as well as for restricting marriage in ways that other contracts are not restricted.

Before exploring some common rationales, it is worth noting that critics of the social contract model of the state and of freedom of contract have used the example of marriage against contractual principles. First, Marxists have argued that freedom of contract is compatible with exploitation and oppression—and Marxist feminists have taken marriage as a special example, arguing against contractualizing it on these grounds (Pateman 1988, 162–188). Such points, as we will see, suggest the need for rules governing property division on divorce. Second, communitarians have argued that contractual relations are inferior to those characterized by trust and affection—again, using marriage as a special example (Sandel 1982, 31–35, cf. Hegel 1821, §75, §161A). This objection applies not only to contractualizing marriage, but more generally, to treating it as a case for application of principles of justice: the concern is that a rights-based perspective will undermine the morally superior affection between family members, importing considerations of individual desert which alienate family members from their previous unselfish identification with the whole (Sandel 1982, 31–35). However, although marriages are not merely an exchange of rights, spousal rights protect spouses’ interests when affection fails; given the existence of abuse and economic inequality within marriage, these rights are especially important for protecting individuals within, and after, marriage (Kleingeld 1998, Shanley 2004, 3–30, Waldron 1988).

As noted, a rationale must be given for marriage law which explains the restrictions placed on entry and exit, the allocation of resources to marriage, and legal discrimination on the basis of it. The next section will examine gender restrictions on entry; this section will examine reasons for recognizing marriage in law at all, allocating resources to it, and constraining property division on divorce.

A first reason for recognizing marriage should be set aside. This is that the monogamous heterosexual family unit is a natural, pre-political structure which the state must respect in the form in which it finds it (Morse 2006; cf. new natural lawyers, Girgis et al. 2010). But, whatever the natural reproductive unit may be, marriage law, as legislation, is constrained by principles of justice constraining legislation. Within most contemporary political philosophy, the naturalness of a given practice is irrelevant; indeed, in no area other than the family is it proposed that law should follow nature (with the possible exception of laws regarding suicide). Finally, such objections must answer to feminist concerns that excluding the family unit from principles of justice, allowing natural affection to regulate it, has facilitated inequality and abuse within it (see section 5).

Let us then begin with the question of why marriage should be recognized in law at all. One answer is that legal recognition conveys the state’s endorsement, guiding individuals into a valuable form of life (George 2000). A second is that legal recognition is necessary to maintain and protect social support for the institution, a valuable form of life which would otherwise erode (Raz 1986, 162, 392–3; Scruton 1986, 356–361; see discussion in Waldron 1988–89). But this prompts the question as to why this form of life is valuable.

It is sometimes argued that traditions, having stood the test of time, have proved their value. Not only is marriage itself such a tradition, but through its child-rearing role it can pass on other traditions (Sommers 1989, Scruton 1986, 356–361, cf. Devlin 1965, Chapter 4). But many marital traditions—coverture, gender-structured legal duties, marital rape exemptions, inter-racial marriage bans—have been unjust. Tradition provides at best a prima facie reason for legislation which may be overridden by considerations of justice. Further, in a diverse society, there are many competing traditions, amongst which this rationale fails to choose (Garrett 2008).

An account of the value of a particular form of marriage itself (and not just qua tradition) is needed. One thought is that monogamous marriage encourages the sexual self-control needed for health and happiness; another is that it encourages the goods of love and intimacy found in committed relationships. State support for monogamous marriage, by providing incentives to enter marital commitments, thus helps people lead better lives (e.g. Macedo 1995, 286). However, this approach faces objections. First, the explanation in terms of emotional goods underdetermines the institution to be supported: other relationships, such as friendships, embody emotional goods. Second, claims about the value of sexual self-control are controversial; objectors might argue that polygamy, polyamory, or promiscuity are equally good options (see 5.2). There is a further problem with this justification, which speaks to a division within liberal thought. Some liberals embrace neutrality, the view that the state should not base law on controversial judgments about what constitutes valuable living. To such neutral liberals, this class of rationales, which appeal to controversial value judgments about sex and love, must be excluded (Rawls 1997, 779). Some theorists have sought to develop rationales consistent with political liberalism, arguing, for instance, that the intimate dyadic marital relationship protects autonomy (Bennett 2003), or that some form of marriage could be justified by its efficiency in providing benefits (Toop 2019) or its role in protecting diverse caring relationships (Brake 2012), fragile romantic love relationships (Cave 2017), or caregivers and children (Hartley and Watson 2012, Toop 2019; see also May 2016, Wedgwood 2016).

It is widely accepted that the state should protect children. If two-parent families benefit children, incentives to marry may be justified as promoting two-parent families and hence children’s welfare. One benefit of two-parent families is economic: there is a correlation between single motherhood and poverty. Another benefit is emotional: children appear to benefit from having two parents (Galston 1991, 283–288). (Moreover, some argue that gender complementarity in parenting benefits children; but empirical evidence does not seem to support this [Lee 2008, Nussbaum 1999, 205, Manning et al ., 2014].)

One objection to this line of argument is that marriage is an ineffective child anti-poverty plan. For one thing, this account assumes that incentives to marry will lead a significant number of parents who would not otherwise have married to marry. But marriage and child-rearing have increasingly diverged despite incentives to marry. Second, this approach does not address the many children outside marriages and in poor two-parent families. Child poverty could be addressed more efficiently through direct anti-child-poverty programs rather than the indirect strategy of marriage (Cave 2004; Vanderheiden 1999; Young 1995). Moreover, there is controversy over the psychological effects of single parenthood, particularly over the causality underlying certain correlations: for instance, are children of divorce unhappier due to divorce itself, or to the high-conflict marriage preceding it? (Young 1995) Indeed, some authors have recently argued that children might be better protected by legally separating marriage from parenting: freestanding parenting frameworks would be more durable than marriage (which can end in divorce), would protect children outside of marriages, and would accommodate new family forms such as three-parent families (Brennan and Cameron 2016, Shrage 2018; see also Chan and Cutas 2012).

A related, but distinct, line of thought invokes the alleged psychological effects of two-parent families to argue that marriage benefits society by promoting good citizenship and state stability (Galston 1991, 283–288). This depends on the empirical case (as we have seen, a contested one) that children of single parents face psychological and economic hurdles which threaten their capacity to acquire the virtues of citizenship. Moreover, if economic dependence produces power inequality within marriage, then Mill’s ‘school of injustice’ objection applies—an institution teaching injustice is likely to undermine the virtues of citizenship (Okin 1994, Young 1995).

Finally, a rationale for restricting the terms of exit from marriage (but not for supporting it as a form of life) is the protection of women and children following divorce. Women in gender-structured marriages, particularly if they have children, tend to become economically vulnerable. Statistically, married women are more likely than their husbands to work in less well-paid part-time work, or to give up paid work entirely, especially to meet the demands of child-rearing. Thus, following divorce, women are likely to have a reduced standard of living, even to enter poverty. Because these patterns of choice within marriages lead to inequalities between men and women, property division on divorce is a matter of equality or equal opportunity, and so a just law of divorce is essential to gender justice (Okin 1989, Chapters 7 and 8; Rawls 1997, 787–794; Shanley 2004, 3–30; Waldron 1988, and see 5.1). However, it can still be asked why a law recognizing marriage as such should be necessary, as opposed to default rules governing property distribution when such gender-structured relationships end (Sunstein and Thaler 2008, Chambers 2017). Indeed, placing these restrictions only on marriage, as opposed to enacting general default rules, may make marriage less attractive, especially to men, and hence be counter-productive, leaving women more vulnerable.

The preceding two rationales are both weakened by the diminished social role of marriage; changing legal and social norms undermine its effectiveness as a policy tool. In the 20 th century, marriage was beset by a “perfect storm”: the expectation that it should be emotionally fulfilling, women’s liberation, and effective contraception (Coontz 2006, Chapter 16). Legally, exit from marriage has become relatively easy since the ‘no-fault divorce revolution’ of the 1970’s. Moreover, cohabitation and child-rearing increasingly take place outside marriage. This reflects the end of laws against unmarried cohabitation and legal discrimination against children on grounds of ‘illegitimacy’, as well as diminishing social stigmas against such behavior. Given such significant changes, marriage is at best an indirect strategy for achieving goals such as protecting women or children (Cave 2004, Sunstein and Thaler 2008, Vanderheiden 1999).

Some theorists have argued, in the absence of a compelling rationale for marriage law, for abolishing marriage altogether, replacing it with civil unions or domestic partnerships. This line of thought will be taken up in 4.4, after an examination of the debate over same-sex marriage.

Many arguments for same-sex marriage invoke liberal principles of justice such as equal treatment, equal opportunity, and neutrality. Where same-sex marriage is not recognized in law, marriage provides benefits which are denied to same-sex couples on the basis of their orientation; if the function of marriage is the legal recognition of loving, or “voluntary intimate,” relationships, the exclusion of same-sex relationships appears arbitrary and unjustly discriminatory (Wellington 1995, 13). Same-sex relationships are relevantly similar to different-sex relationships recognized as marriages, yet the state denies gays and lesbians access to the benefits of marriage, hence treating them unequally (Mohr 2005, Rajczi 2008, Williams 2011). Further, arguments in support of such discrimination seem to depend on controversial moral claims regarding homosexuality of the sort excluded by neutrality (Wellington 1995, Schaff 2004, Wedgwood 1999, Arroyo 2018).

A political compromise (sometimes proposed in same-sex marriage debates) of restricting marriage to different-sex couples and offering civil unions or domestic partnerships to same-sex couples does not fully answer the arguments for same-sex marriage. To see why such a two-tier solution fails to address the arguments grounded in equal treatment, we must consider what benefits marriage provides. There are tangible benefits such as eligibility for health insurance and pensions, privacy rights, immigration eligibility, and hospital visiting rights (see Mohr 2005, Chapter 3), which could be provided through an alternate status. Crucially, however, there is also the important benefit of legal, and indirectly social, recognition of a relationship as marriage. The status of marriage itself confers legitimacy and invokes social support. A two-tier system would not provide equal treatment because it does not confer on same-sex relationships the status associated with marriage .

In addition, some philosophers have argued that excluding gays and lesbians from marriage is central to gay and lesbian oppression, making them ‘second-class citizens’ and underlying social discrimination against them. Marriage is central to concepts of good citizenship, and so exclusion from it displaces gays and lesbians from full and equal citizenship: “being fit for marriage is intimately bound up with our cultural conception of what it means to be a citizen … because marriage is culturally conceived as playing a uniquely foundational role in sustaining civil society” (Calhoun 2000, 108). From this perspective, the ‘separate-but-equal’ category of civil unions retains the harmful legal symbol of inferiority (Card 2007, Mohr 2005, 89, Calhoun 2000, Chapter 5; cf. Stivers and Valls 2007; for a comprehensive survey of these issues, see Macedo 2015).

However, if marriage is essentially different-sex, excluding same-sex couples is not unequal treatment; same-sex relationships simply do not qualify as marriages. One case that marriage is essentially different-sex invokes linguistic definition: marriage is by definition different-sex, just as a bachelor is by definition an unmarried man (Stainton, cited in Mercier 2001). But this confuses meaning and reference. Past applications of a term need not yield necessary and sufficient criteria for applying it: ‘marriage’, like ‘citizen’, may be extended to new cases without thereby changing its meaning (Mercier 2001). As noted above, appeal to past definition begs the question of what the legal definition should be (Stivers and Valls 2007).

A normative argument for that marriage is essentially different-sex appeals to its purpose: reproduction in a naturally procreative unit (see 3.2.a). But marriage does not require that spouses be able to procreate naturally, or that they intend to do so at all. Further, married couples adopt and reproduce using donated gametes, rather than procreating ‘naturally’. Nor do proponents of this objection to same-sex marriage generally suggest that entry to marriage should be restricted by excluding those unable to procreate without third-party assistance, or not intending to do so.

Indeed, as the existence of intentionally childless married couples suggests, marriage has purposes other than child-rearing—notably, fostering a committed relationship (Mohr 2005, Wellington 1995, Wedgwood 1999). This point suggests a second defense of same-sex marriage: exclusive marital commitments are goods which the state should promote amongst same-sex as well as opposite-sex couples (Macedo 1995). As noted above, such rationales come into tension with liberal neutrality; further controversy regarding them will be discussed below (5.2).

Some arguments against same-sex marriage invoke a precautionary principle urging that changes which might affect child welfare be made with extreme caution. But in light of the data available, Murphy argues that the precautionary principle has been met with regard to harm to children. On his view, parenting is a basic civil right, the restriction of which requires the threat of a certain amount of harm. But social science literature shows that children are neither typically nor seriously harmed by same-sex parenting (see Manning et al ., 2014). Even if two biological parents statistically provide the optimal parenting situation, optimality is too high a standard for permitting parenting. This can be seen if an optimality condition is imagined for other factors, such as education or wealth (Murphy 2011).

A third objection made to same-sex marriage is that its proponents have no principled reason to oppose legally recognizing polygamy (e.g. Finnis 1997; see Corvino 2005). One response differentiates the two by citing harmful effects and unequal status for women found in male-headed polygyny, but not in same-sex marriage (e.g. Wedgwood 1999, Crookston 2014, de Marneffe 2016, Macedo 2015). Another response is to bite the bullet: a liberal state should not choose amongst the various ways (compatible with justice) individuals wish to organize sex and intimacy. Thus, the state should recognize a diversity of marital relationships—including polygamy (Calhoun 2005, Mahoney 2008) or else privatize marriage, relegating it to private contract without special legal recognition or definition (Baltzly 2012).

Finally, some arguments against same-sex marriage rely on judgments that same-sex sexual activity is impermissible. As noted above, the soundness of these arguments aside, neutrality and political liberalism exclude appeal to such contested moral views in justifying law in important matters (Rawls 1997, 779, Schaff 2004, Wedgwood 1999, Arroyo 2018). However, some arguments against same-sex marriage have invoked neutrality, on the grounds that legalizing same-sex marriage would force some citizens to tolerate what they find morally abhorrent (Jordan 1995, and see Beckwith 2013). But this reasoning seems to imply, absurdly, that mixed-race marriage, where that is the subject of controversy, should not be legalized. A rights claim to equal treatment (if such a claim can support same-sex marriage) trumps offense caused to those who disagree; the state is not required to be neutral in matters of justice (Beyer 2002; Boonin 1999; Schaff 2004; see also Barry 2011, Walker 2015).

A number of theorists have argued for the abolition or restructuring of marriage. While same-sex marriage became legally recognized throughout the United States following the Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v Hodges 576 U.S. _ (2015) , some philosophers contend that justice requires further reform. Some have proposed that temporary marriage contracts be made available (Nolan 2016, Shrage 2013) and that legal frameworks for marriage and parenting be separated (Brennan and Cameron 2016, Shrage 2018). A more sweeping view, to be discussed in Section 5, is that marriage is in itself oppressive and unjust, and hence ought to be abolished (Card 1996, Fineman 2004, Chambers 2013, 2017). A second argument for disestablishing or privatizing legal marriage holds that, in the absence of a pressing rationale for marriage law (as discussed in 4.2), the religious or ethical associations of marriage law give reason for abolishing marriage as a legal category. Marriage has religious associations in part responsible for public controversy over same-sex marriage. If marriage is essentially defined by a religious or ethical view of the good, then legal recognition of it arguably violates state neutrality or even religious freedom (Metz 2010, but see Macedo 2015, May 2016, Wedgwood 2016).

There are several reform proposals compatible with the ‘disestablishment’ of marriage. One proposal is full contractualization or privatization, leaving marriage to churches and private organizations. “Marital contractualism” (MC) would relegate spousal agreements to existing contract law, eradicating any special legal marital status or rights. Garrett has defended MC as the default position, arguing that state regulation of contracts between spouses and state expenditures on marriage administration and promotion need justification. On his view, efficiency, equality, diversity, and informed consent favor MC; there is no adequate justification for the costly redistribution of taxpayer funds to the married, or for sustaining social stigma against the unmarried through legal marriage (Garrett 2009, see also Chartier 2016).

But marriage confers rights not available through private contract and which arguably should not be eliminated due to their importance in protecting intimate relationships—such as evidentiary privilege or special eligibility for immigration. A second proposal would retain such rights while abolishing marriage; on this proposal, the state ought to replace civil marriage entirely with a secular status such as civil union or domestic partnership, which could serve the purpose of identifying significant others for benefit entitlements, visiting rights, and so on (March 2010, 2011). This would allow equal treatment of same-sex relationships while reducing controversy, avoiding non-neutrality, and respecting the autonomy of religious organizations by not compelling them to recognize same-sex marriage (Sunstein and Thaler 2008). However, neither solution resolves the conflict between religious autonomy and equality for same-sex relationships. Privatization does not solve this conflict so long as religious organizations are involved in civil society—for example, as employers or benefit providers. The question is whether religious autonomy would allow them, in such roles, to exclude same-sex civil unions from benefits. Such exclusion could be defended as a matter of religious autonomy; but it could also be objected to as unjust discrimination—as it would be if, for example, equal treatment were denied to inter-racial marriages.

Another issue raised by such a reform proposal is how to delimit the relationships entitled to such recognition. Recall the new natural law charge that liberalism entails an objectionable “plasticicty” regarding marriage (3.2.1). One question is whether recognition should be extended to polygamous or polyamorous relationships. Some defenders of same-sex marriage hold that their arguments do not entail recognizing polygamy, due to its oppressive effects on women (Wedgwood 1999). However, some monogamous marriages are also oppressive (March 2011), and egalitarian polygamous or polyamorous relationships, such as a group of three women or three men, exist (Emens 2004). Thus, oppressiveness does not cleanly distinguish monogamous from polygamous relationships. Brooks has sought to show that polygamy is distinctively structurally inegalitarian as one party (usually the husband) can determine who will join the marriage, whereas wives cannot (Brooks 2009). However, this overlooks various possible configurations—if a polygamous “sister wife,” for instance, has the legal right to marry outside the existing marriage, there is no structural inequality (Strauss 2012). Most fundamentally, some authors have urged that a politically liberal state should not prescribe the arrangements in which its competent adult members seek love, sex, and intimacy, so long as they are compatible with justice (Calhoun 2005, March 2011). Some philosophers have argued that polygamists and polyamorous people are unjustly excluded from the benefits of marriage, and that legal recognition of plural marriage - or small groups of friends – can preserve equality (Brake 2012, 2014, Den Otter 2015, Shrage 2016). Finally, the history of racialized stigmatization of polygamy gives reason to consider whether anti-polygamous intuitions rest on just foundations (Denike 2010).

Conservatives also charge that the liberal approach cannot rule out incestuous marriage. While this topic has sparked less debate than polygamy, one defender of the civil-unions-for-all proposal has pointed out that civil union status, as justified on politically liberal grounds, would not connote sexual or romantic involvement. Thus, eligibility of adult family members for this status would not convey state endorsement of incest; whether the state should prohibit or discourage incest is an independent question (March 2010).

A further problem arises with the proposal to replace marriage with civil unions on neutrality grounds. Civil unions, if they carry legal benefits similar to marriage, would still involve legal discrimination (between members of civil unions and those who were not members) requiring justification (for a specific example of this problem in the area of immigration law, see Ferracioli 2016). Depending on how restrictive the entry criteria for civil unions were (for example, whether more than two parties, blood relations, and those not romantically involved could enter) and how extensive the entitlements conferred by such unions were, the state would need to provide reason for this discrimination. In the absence of compelling neutral reasons for such differential treatment, liberty considerations suggest the state should cease providing any special benefits to members of civil unions (or intimate relationships) (Vanderheiden 1999, cf. Sunstein and Thaler 2008). As noted in 4.2, some political liberals have sought to provide rationales showing why a liberal state should support certain relationships; these rationales generate corresponding reform proposals. One approach focuses on protecting economically dependent caregivers; Metz proposes replacing civil marriage with “intimate care-giving unions” which would protect the rights of dependent caregivers (Metz 2010; cf. Hartley and Watson 2012). Another approach holds that caring relationships themselves - whether friendships or romantic relationships - should be recognized as valuable by the politically liberal state, and it should, accordingly, distribute rights supporting them equally; the corresponding reform proposal, “minimal marriage,” would provide rights directly supporting relationships, but not economic benefits, without restriction as to sex or number of parties or the nature of their caring relationship (Brake 2012). This would extend marriage not only to polyamorists, but to asexuals and aromantics, as well as those who choose to build their lives around friendships. A third approach proposes that marital rights and status be replaced by “piecemeal directives” which would regulate the various functional contexts to which marriage law now applies (such as cohabitation and co-parenting) (Chambers 2017); this proposal would avoid designating any relationship type as entitled to special treatment.

Many of the views discussed to this point imply that current marriage law is unjust because it arbitrarily excludes some groups from benefits; it follows, on such views, that marrying is to avail oneself of privileges unjustly extended. This seems to give reason for boycotting the institution, so long as some class of persons is unjustly excluded (Parsons 2008).

Before Obergefell , U.S. law was in patchwork regarding marriages involving at least one transgender person — “trans—marriage,” in Loren Cannon’s term. As a transgender person traveled from state to state, both their legal sex and marital status could change (Cannon 2009, 85). While some raised concerns that the political rationales given for recognizing such marriages (such as the possibility of penile-vaginal intercourse) reaffirmed heteronormative assumptions (Robson 2007), to other theorists, the possibility of trans-marriage itself suggests the instability or incoherence of legal gender categories and gendered restrictions on marriage (Cannon 2009, Almeida 2012).

5. Marriage and Oppression: Gender, Race, and Class