- Fundamentals NEW

- Biographies

- Compare Countries

- World Atlas

Introduction

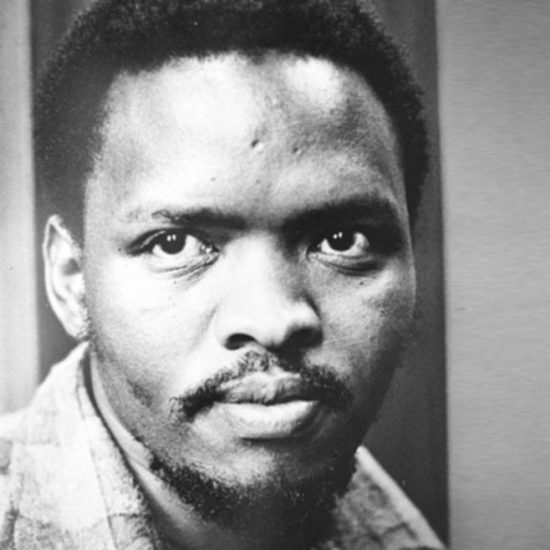

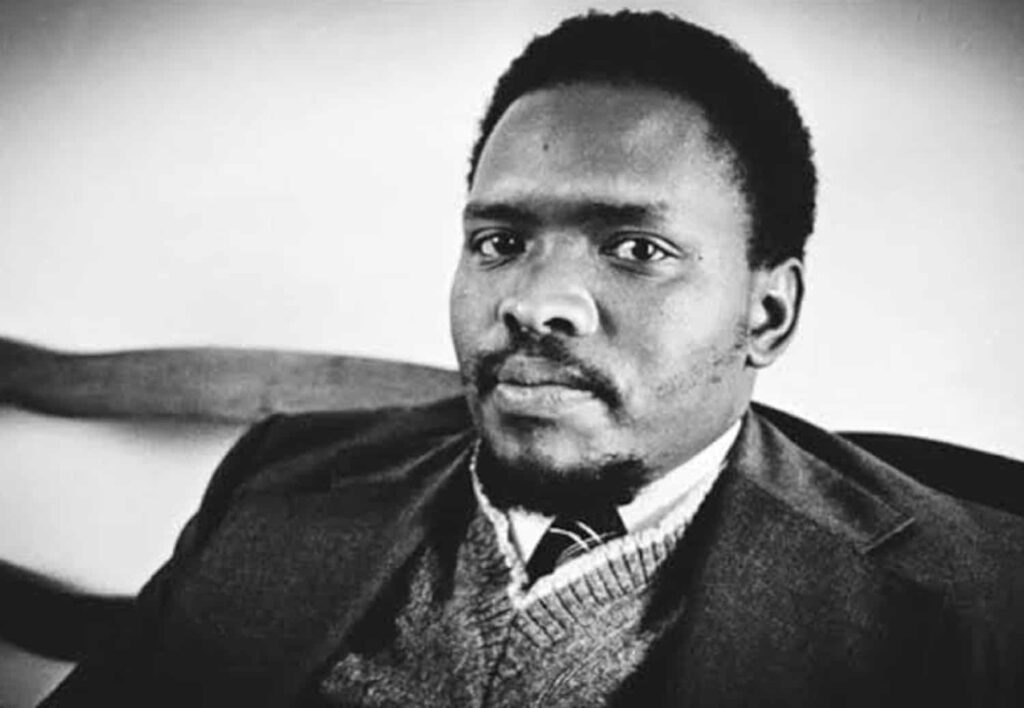

Bantu Stephen (“Steve”) Biko was born on December 18, 1946, in King William’s Town, South Africa . His father was a clerk and his mother was a domestic worker.

Biko began fighting against apartheid at an early age. He was expelled from Lovedale High School for his political activities. He then attended Saint Francis College. After graduating, he was admitted to the University of Natal’s medical school. In 1968 he helped start the all-black South African Students’ Organization (SASO). He became president of SASO the next year.

Black Consciousness

The SASO was based on the ideas of Black Consciousness. The leaders of the Black Consciousness movement had a new goal for change in South Africa. Other groups were working to allow blacks to participate in the current society. The leaders of the Black Consciousness movement, however, wanted blacks to establish their own society based on their own culture.

In 1972 Biko left the university and began to work for the Black Community Programmes (BCP) in Durban. The BCP provided resources to help blacks become independent. These included schools, newspapers, health clinics, and businesses. Biko believed that black South Africans needed to work together to break “the chains of oppression.”

The South African government felt threatened by Biko’s activities. It banned Biko in 1973. The ban meant that he could not move around freely or make any public statements. Biko challenged the ban by continuing to organize for the BCP.

In August 1977 Biko was arrested. The police took him to jail, where they beat him severely. On September 12, 1977, Biko died in Pretoria from his injuries. More than 20,000 people attended his funeral. His death had a major influence on the movement to end apartheid because it inspired blacks to fight for their rights.

It’s here: the NEW Britannica Kids website!

We’ve been busy, working hard to bring you new features and an updated design. We hope you and your family enjoy the NEW Britannica Kids. Take a minute to check out all the enhancements!

- The same safe and trusted content for explorers of all ages.

- Accessible across all of today's devices: phones, tablets, and desktops.

- Improved homework resources designed to support a variety of curriculum subjects and standards.

- A new, third level of content, designed specially to meet the advanced needs of the sophisticated scholar.

- And so much more!

Want to see it in action?

Start a free trial

To share with more than one person, separate addresses with a comma

Choose a language from the menu above to view a computer-translated version of this page. Please note: Text within images is not translated, some features may not work properly after translation, and the translation may not accurately convey the intended meaning. Britannica does not review the converted text.

After translating an article, all tools except font up/font down will be disabled. To re-enable the tools or to convert back to English, click "view original" on the Google Translate toolbar.

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What is apartheid?

- When did apartheid start?

- How did apartheid end?

- What is the apartheid era in South African history?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- African American Registry - Stephen Biko, African Freedom Fighter born

- My Hero - Biography of Bantu Stephen Biko

- Stanford University - Steve Biko

- South African History Online - Biography of Stephen Bantu Biko

- Digital Innovation South Africa - Steve Biko (1946 - 1977)

- CORE - Incomplete Histories: Steve Biko, the Politics of Self-Writing and the Apparatus of Reading

- Academia - Steve Biko: The Intellectual Roots of South African Black Consciousness

- Steve Biko - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Steve Biko - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Steve Biko (born December 18, 1946, King William’s Town , South Africa—died September 12, 1977, Pretoria) was the founder of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa . His death from injuries suffered while in police custody made him an international martyr for South African Black nationalism .

After being expelled from high school for political activism, Biko enrolled in and graduated (1966) from St. Francis College, a liberal boarding school in Natal , and then entered the University of Natal Medical School. There he became involved in the multiracial National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), a moderate organization that had long espoused the rights of Blacks. He soon grew disenchanted with NUSAS, believing that, instead of simply allowing Blacks to participate in white South African society, the society itself needed to be restructured around the culture of the Black majority. In 1968 he cofounded the all-Black South African Students’ Organization (SASO), and he became its first president the following year. SASO was based on the philosophy of Black consciousness , which encouraged Blacks to recognize their inherent dignity and self-worth. In the 1970s the Black Consciousness Movement spread from university campuses into urban Black communities throughout South Africa. In 1972 Biko was one of the founders of the Black People’s Convention, an umbrella organization of Black consciousness groups.

Biko drew official censure in 1973, when he and other SASO members were banned; their associations, movements, and public statements were thereby restricted. He then operated covertly, establishing the Zimele Trust Fund in 1975 to help political prisoners and their families. He was arrested four times over the next two years and was held without trial for months at a time. On August 18, 1977, he and a fellow activist were seized at a roadblock and jailed in Port Elizabeth . Biko was found naked and shackled outside a hospital in Pretoria , 740 miles (1,190 km) away, on September 11 and died the next day of a massive brain hemorrhage.

Police initially denied any maltreatment of Biko; it was determined later that he had probably been severely beaten while in custody, but the officers involved were cleared of wrongdoing. In 1997 five former police officers confessed to having killed Biko and applied for amnesty to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (a body convened to review atrocities committed during the apartheid years); amnesty was denied in 1999. Donald Woods, a South African journalist, depicts his friendship with Biko in Biko (1977; 3rd rev. ed., 1991), and their relationship is portrayed in the film Cry Freedom (1987).

World History Edu

- Africa / South Africa

Steve Biko: 6 Memorable Achievements of the South African anti-Apartheid Activist

by World History Edu · December 16, 2020

Steve Biko was a South African anti-apartheid activist who is best remembered for devoting his short-lived life to fighting against racial segregation. Steve Biko is renowned for co-founding the South African Students’ Organization (SASO) to promote the rights of Blacks. He spent the majority of his youth and significant amount of resources in fighting against the apartheid government. For example, such was his dedication to the cause of Black rights that he got expelled from many of the schools he attended.

His grassroots campaigns for universal suffrage and the empowerment of Black South Africans drew the ire of the authorities, resulting in him getting arrested many times. Biko called on all Blacks to take pride in their race (i.e. through the adopted slogan “black is beautiful”) and eschew the pressure to maintain value systems of the white-minority. In 1977, Steve Biko sadly passed away after sustaining life-threatening injuries while in police custody.

READ MORE: Greatest African Leaders and Their Accomplishments

Fast Facts about Steve Biko

Born : Bantu Stephen Biko

Date of birth : December 18, 1946

Place of birth : King William’s Town, Eastern Cape, South Africa

Date of death : September 12, 1977

Place of death : Pretoria, South Africa

Burial place: Ginsberg Cemetery

Parents : Mzingaye Mathew Biko and Alice ‘Mamcete’ Biko

Siblings : Bukelwa, Khaya, Nobandile

Education: University of Natal Medical School, St. Francis College (1964-1965)

Spouse : Ntiki Nashalaba (married in 1970)

Children : Nkosinathi and Samora (with Ntsiki Mahalaba); Lerato and Hlumelo (with Mamphela Ramphele); Motlatsi (with Lorraine Tabane)

Ideology : African nationalist and socialist

Influenced by : Ahmed Ben Bella and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga

Most known for : being an anti-apartheid campaigner; Martyr of Black Consciousness; Father of Black Consciousness

Achievements of Steve Biko

Here are 6 important achievements of Steve Biko (1946-1977), the anti-apartheid activist and the leader of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa.

United all racial groups to fight against white minority rule in South Africa

Although Biko was a huge fan of the Pan Africanist Congress and other African nationalist organizations, he reasoned that apartheid in South Africa could only end when all the racial groups (i.e. non-whites) unite to defeat the ruling white minority class. Starting at an early age while at a boarding school called St. Francis College,

Biko was irritated by the nature of the school’s administration. He voiced his resentment against the apartheid government. Much of his inspiration came from pan Africanists such as Kenya’s independence fighter Jaramogi Oginga and Algeria’s Ahmed Ben Bella (later Algeria’s first president).

READ MORE: 10 African Countries That Had The Bloodiest Path To Independence

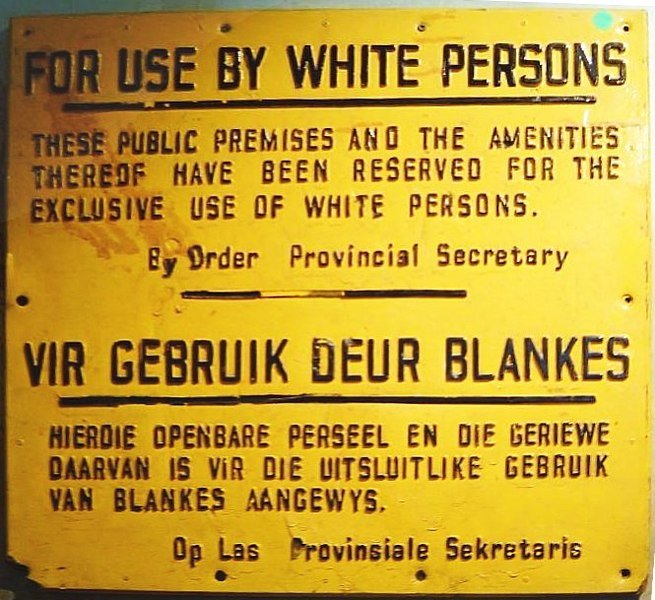

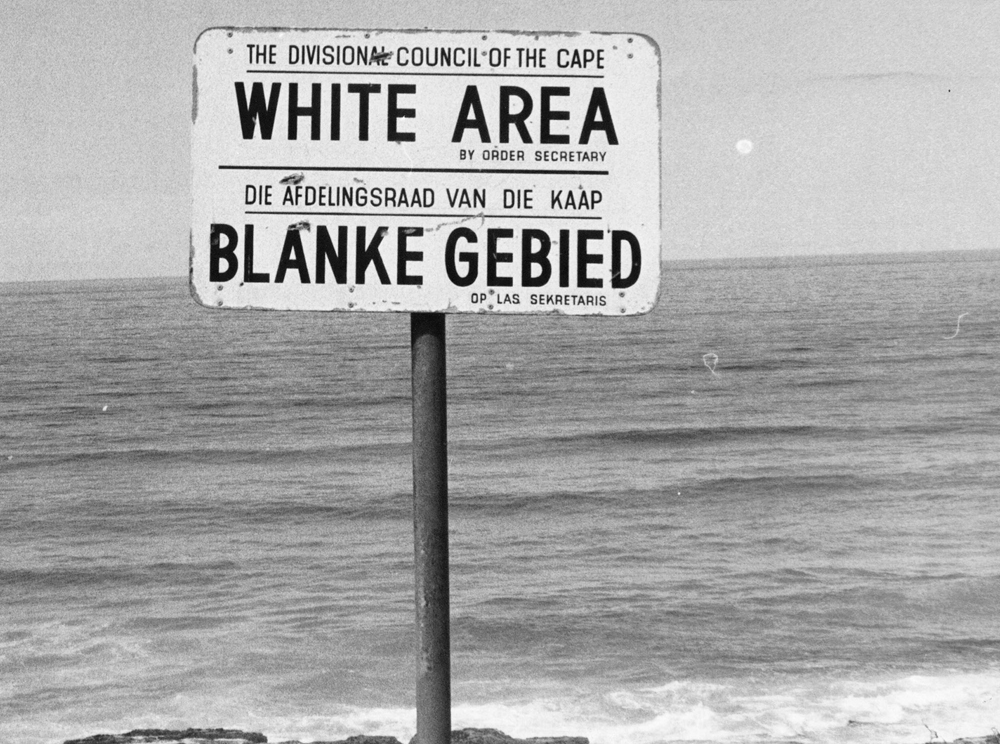

Apartheid in South Africa

Active member of the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS)

His activism started from quite an early age. As a matter of fact, he was dismissed from his high school for his activism. After he was expelled, he went on to study at St. Francis College in KwaZulu-Natal. He graduated in 1966 and attended the University of Natal Medical School.

He was active in student activism, participating in the activities the Students’ Representative Council (SRC). He was also a member of the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), fighting vocally against the apartheid government’s perpetration of white minority rule and racial segregation.

Encouraged blacks to feel worthy of a better life

Steve Biko achievements

The students’ union was largely made up of white liberals, who Biko believed that could never understand the ills that black people had to go through in apartheid South Africa. He was particularly concerned by the fact that the NUSAS was financed by white students and liberals. What irritated him the most was that, black Africans were prevented from entering the very dormitories that took host to the parties organized by NUSAS.

Biko’s admiration for a multi-racial approach to ending apartheid in South quickly evaporated, making way for a “black” nationalist approach. He called on Black students to act and organize as an independent people and push against the oppressive and racist South African government.

He went on to advocate for the psychological empowerment of blacks. He stated on numerous occasions that the Blackman must abandon all beliefs passed onto to him by his colonial masters. Those beliefs he reasoned were mental chains that held the black race down in a life of no dignity. According to Steve Biko, the “Blacks” should feel worthy of freedom and aspire to greater heights.

Did you know : Steve Biko drew quite a lot of inspiration from the French West Indian philosopher Frantz Fanon and the African-American Black Power Movement?

Steve Biko co-foundered the South African Students’ Organization

Founded in July 1969, the South African Students’ Organization (SASO) was Biko’s way of placing “blacks” at the forefront in the fight against white-minority rule and racial segregation. Biko and the co-founders of SASO made sure that the organization was opened to only blacks; by blacks he referred to non-whites; meaning it included the likes of Indians and other non-white minorities.

Steve Biko’s South African Students’ Organization (SASO) worked hard to promote the rights of Blacks through the usage of student activities such as sports, cultural exchanges, debates, and other social activities. The group directed a significant amount of its resources in fighting against the apartheid government in South Africa. A year after its establishment, in 1969, Biko was elected the organization’s president – the first president. Such was his dedication to the cause of Black rights that school’s authority panicked and expelled Biko from the university in 1972.

It must be noted that Biko categorically stated that he was against anti-white racism. As a matter of fact, he had several white friends and acquaintances, most notably Duncan Innes (former president of NUSAS) and Donald Woods. The latter went on to write a Steve Biko’s Biography in 1978.

The change in direction of activists like Biko from multi-racial activism to a Black Nationalist approach came as good news for the white-minority National Party. The NP as a matter of fact initially gave their tacit approval to the activities of SASO as it reinforced their goal of racial segregation.

Did you know : Perhaps owing to poor academic results, Steve Biko was expelled from the University of Natal? Some have attributed his dismissal to his activism in the South African Students’ Organization.

Promoted Black Consciousness among the people

Steve Biko’s quote

The guiding ideology of Biko’s student organizations was the ideology of “Black Consciousness” – an ideology that encouraged Blacks to dispel the notions of race inferiority imposed on them for centuries by colonialists. Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement targeted the emancipation of the minds of Blacks. He and his fellow activists – such as Barney Pityana, Pat Matshaka (vice president of SASO) and Wulia Mashalaba (secretary of SASO) – believed that Blacks had to surmount the cultural, moral and psychological harm inflicted on them by white racists groups before they could step into their full greatness. The ideology was inspired by Black Power Movements and activists (notably Malcolm X) in the United States.

In simple terms, the Black Consciousness that Biko and the SASO preached was a way of life that was geared towards independent thought and critical reasoning.

Read More: 12 Important Accomplishments by Nelson Mandela

Co-founded the Black People’s Convention

Much of the work that Biko did as president of SASO was in the area of fundraising and recruiting activists to push the cause of the organization. In 1972, Biko voluntarily stepped down from his position at SASO, stating that he was passing on the mantle to a new crop of leaders. Biko was concerned that a cult of personality could build around him were he to stay longer as president of SASO.

After attending a conference in Edendale in August 1971, Biko and other Black Consciousness activists set about to establish the Black People’s Convention (BPC). The goal of the convention was to bring Black Consciousness to the masses. To the slight dismay of Steve Biko, the BPC, which was founded in July, 1972, excluded Coloured South Africans and Indians from participating.

The Convention appointed A. Mayatula as its president. Biko helped the Convention open up branches all across the country. About a year after its formation, the BPC could boast of more than 40 branches and a membership size of over 3500. Biko also tried to coordinate the activities of the BPC and SASO.

Biko and other Black activists set up the Black People’s Convention. As the leader of the group, Biko continued to call for the end of the apartheid regime. The group remained very relevant throughout the 1970s, working in cohort with other civil rights organizations in and outside South Africa. Their approach to spreading Black Consciousness was through the use of community programs (which were run by the Black Community Programmes) and healthcare centers. For example, they established a number of schools in the Ginsberg area.

Did you know : Steve Biko initiated talks with anti-apartheid organizations such as the African National Congress (ANC) in order to merge the activities of the BCM and the Pan Africanist Congress?

How did Steve Biko Die?

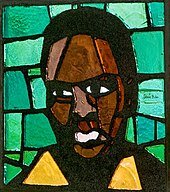

Steve Biko image on a stained glass window in the Saint Anna Church in Heerlen, the Netherlands

With the passage of time, and the increasing intensity of Steve Biko’s activism, the apartheid government became very concerned about the activities of the BCM, considering the movement and Biko threats to the state. Tagging the activism of Biko as everything but subversive, the apartheid government acted swiftly and imposed a ban on him in 1973.

Biko was stripped of the most basic of civil liberties. For example, he was banned from leaving his home King William’s Town. The activist was also prevented from voicing out his opinions, either in speech or in writing. He was also prevented from speaking to any journalist. He was also prevented from goin to his hometown King William’s Town.

The ban on Biko put a huge strain on his personal life, affecting his marriage and his ambitions to get a law degree from the University of South Africa. He was also subjected to threatening phone calls and outright malicious attacks from unidentified people. His house was once shot up by unknown assailants. The ban on him also put enormous financial hardships on him, as he could not find any gainful job.

This ban on Steve Biko’s civil liberties somewhat curtailed the gains that were being his movement. However, Biko circumvented this ban taking most of his operations underground, hiding away from the authorities. By the late 1970s, Steve Biko had been arrested and detained on several occasions.

On August 18, 1977, Steve Biko, while he was on his way from a political meeting in Cape Town, was taken into custody and locked up in Port Elizabeth, which is in the southern part of the country. He was charged under the Terrorism Act. The authorities also accused him of obstructing the course of justice and tempering with witnesses’ oral statements.

While in custody, he was interrogated for hours a day and subjected to the most inhumane conditions. On September 11, 1977, Biko, chained and stripped naked, was sent to Pretoria, South Africa. While in police custody, Biko was brutally assaulted to the extent that he had to be later sent to the hospital. The renowned activist and anti-apartheid icon succumbed to the injuries he sustained at the hands of the racist cops. Steve Biko died on September 12, 1977. He died of what doctors say was a brain hemorrhage.

Biko’s death came as a huge blow to BCM and the anti-apartheid movement in general. His death was received with huge outrage and protests in South Africa and beyond.

The international anti-apartheid icon was buried on September 25, 1977 in Ginsberg Cemetery, near King William’s Town. His funeral was attended by more than 20,000 people.

Steve Biko’s quotes

READ MORE: Nelson Mandela’s Contributions in the Struggle Against Apartheid

Tags: Anti-Apartheid Pan-Africanism Steve Biko

You may also like...

Nelson Mandela: 12 Important Achievements

August 22, 2020

Robert Mugabe’s role in Zimbabwe’s liberation from colonial rule

August 14, 2023

What was the Orange Free State?

January 31, 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story Suez Canal – History, Construction, Significance, Map, Crisis, & Facts

- Previous story Egyptian Goddess Seshat: Origins, Family, Symbols, & Worship

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

John Calvin – History & Major Works of the French Theologian

Frequently Asked Questions about the 1936 Summer Olympics held in Nazi Germany

Helen Keller – Biography, Major Works and Accomplishments

Alien and Sedition Acts: Definition, Origin Story, & Significance

The Pergamon Altar

Greatest African Leaders of all Time

Queen Elizabeth II: 10 Major Achievements

Donald Trump’s Educational Background

Donald Trump: 10 Most Significant Achievements

8 Most Important Achievements of John F. Kennedy

Odin in Norse Mythology: Origin Story, Meaning and Symbols

Ragnar Lothbrok – History, Facts & Legendary Achievements

9 Great Achievements of Queen Victoria

Most Ruthless African Dictators of All Time

12 Most Influential Presidents of the United States

Greek God Hermes: Myths, Powers and Early Portrayals

Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

Kwame Nkrumah: History, Major Facts & 10 Memorable Achievements

8 Major Achievements of Rosa Parks

How did Captain James Cook die?

Trail of Tears: Story, Death Count & Facts

5 Great Accomplishments of Ancient Greece

10 Most Famous Pharaohs of Egypt

The Exact Relationship between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I

How and when was Morse Code Invented?

- Adolf Hitler Alexander the Great American Civil War Ancient Egyptian gods Ancient Egyptian religion Apollo Athena Athens Black history Carthage China Civil Rights Movement Cold War Constantine the Great Constantinople Egypt England France Hera Horus India Isis John Adams Julius Caesar Loki Medieval History Military Generals Military History Napoleon Bonaparte Nobel Peace Prize Odin Osiris Ottoman Empire Pan-Africanism Queen Elizabeth I Religion Set (Seth) Soviet Union Thor Timeline Turkey Women’s History World War I World War II Zeus

Biography of Stephen Bantu (Steve) Biko, Anti-Apartheid Activist

Bfluff / Wikimedia Commons

- American History

- African American History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Postgraduate Certificate in Education, University College London

- M.S., Imperial College London

- B.S., Heriot-Watt University

Steve Biko (Born Bantu Stephen Biko; Dec. 18, 1946–Sept. 12, 1977) was one of South Africa's most significant political activists and a leading founder of South Africa's Black Consciousness Movement . His murder in police detention in 1977 led to his being hailed a martyr of the anti-apartheid struggle. Nelson Mandela , South Africa's post-Apartheid president who was incarcerated at the notorious Robben Island prison during Biko's time on the world stage, lionized the activist 20 years after he was killed, calling him "the spark that lit a veld fire across South Africa."

Fast Facts: Stephen Bantu (Steve) Biko

- Known For : Prominent anti-apartheid activist, writer, founder of Black Consciousness Movement, considered a martyr after his murder in a Pretoria prison

- Also Known As : Bantu Stephen Biko, Steve Biko, Frank Talk (pseudonym)

- Born : December 18, 1946 in King William's Town, Eastern Cape, South Africa

- Parents : Mzingaye Biko and Nokuzola Macethe Duna

- Died : September 12, 1977 in a Pretoria prison cell, South Africa

- Education : Lovedale College, St Francis College, University of Natal Medical School

- Published Works : "I Write What I Like: Selected Writings by Steve Biko," "The Testimony of Steve Biko"

- Spouses/Partners : Ntsiki Mashalaba, Mamphela Ramphele

- Children : Two

- Notable Quote : "The blacks are tired of standing at the touchlines to witness a game that they should be playing. They want to do things for themselves and all by themselves."

Early Life and Education

Stephen Bantu Biko was born on December 18, 1946, into a Xhosa family. His father Mzingaye Biko worked as a police officer and later as a clerk in the King William’s Town Native Affairs office. His father achieved part of a university education through the University of South Africa, a distance-learning university, but he died before completing his law degree. After his father's death, Biko's mother Nokuzola Macethe Duna supported the family as a cook at Grey's Hospital.

From an early age, Steve Biko showed an interest in anti-apartheid politics. After being expelled from his first school, Lovedale College in the Eastern Cape, for "anti-establishment" behavior—such as speaking out against apartheid and speaking up for the rights of Black South African citizens—he was transferred to St. Francis College, a Roman Catholic boarding school in Natal. From there he enrolled as a student at the University of Natal Medical School (in the university's Black Section).

While at medical school, Biko became involved with the National Union of South African Students. The union was dominated by White liberal allies and failed to represent the needs of Black students. Dissatisfied, Biko resigned in 1969 and founded the South African Students' Organisation. SASO was involved in providing legal aid and medical clinics, as well as helping to develop cottage industries for disadvantaged Black communities.

Black Consciousness Movement

In 1972 Biko was one of the founders of the Black Peoples Convention, working on social upliftment projects around Durban. The BPC effectively brought together roughly 70 different Black consciousness groups and associations, such as the South African Student's Movement , which later played a significant role in the 1976 uprisings, the National Association of Youth Organisations, and the Black Workers Project, which supported Black workers whose unions were not recognized under the apartheid regime.

In a book first published posthumously in 1978, titled, "I Write What I Like"—which contained Biko's writings from 1969, when he became the president of the South African Students' Organization, to 1972, when he was banned from publishing—Biko explained Black consciousness and summed up his own philosophy:

"Black Consciousness is an attitude of the mind and a way of life, the most positive call to emanate from the black world for a long time. Its essence is the realisation by the black man of the need to rally together with his brothers around the cause of their oppression—the blackness of their skin—and to operate as a group to rid themselves of the shackles that bind them to perpetual servitude."

Biko was elected as the first president of the BPC and was promptly expelled from medical school. He was expelled, specifically, for his involvement in the BPC. He started working full-time for the Black Community Programme in Durban, which he also helped found.

Banned by the Apartheid Regime

In 1973 Steve Biko was banned by the apartheid government for his writing and speeches denouncing the apartheid system. Under the ban, Biko was restricted to his hometown of Kings William's Town in the Eastern Cape. He could no longer support the Black Community Programme in Durban, but he was able to continue working for the Black People's Convention.

During that time, Biko was first visited by Donald Woods , the editor of the East London Daily Dispatch , located in the province of Eastern Cape in South Africa. Woods was not initially a fan of Biko, calling the whole Black Consciousness movement racist. As Woods explained in his book, "Biko," first published in 1978:

"I had had up to then a negative attitude toward Black Consciousness. As one of a tiny band of white South African liberals, I was totally opposed to race as a factor in political thinking, and totally committed to nonracist policies and philosophies."

Woods believed—initially—that Black Consciousness was nothing more than apartheid in reverse because it advocated that "Blacks should go their own way," and essentially divorce themselves not just from White people, but even from White liberal allies in South Africa who worked to support their cause. But Woods eventually saw that he was incorrect about Biko's thinking. Biko believed that Black people needed to embrace their own identity—hence the term "Black Consciousness"—and "set our own table," in Biko's words. Later, however, White people could, figuratively, join them at the table, once Black South Africans had established their own sense of identity.

Woods eventually came to see that Black Consciousness "expresses group pride and the determination by all blacks to rise and attain the envisaged self" and that "black groups (were) becoming more conscious of the self. They (were) beginning to rid their minds of the imprisoning notions which are the legacy of the control of their attitudes by whites."

Woods went on to champion Biko's cause and become his friend. "It was a friendship that ultimately forced Mr. Woods into exile," The New York Times noted when Woods' died in 2001. Woods was not expelled from South Africa because of his friendship with Biko, per se. Woods' exile was the result of the government's intolerance of the friendship and support of anti-apartheid ideals, sparked by a meeting Woods arranged with a top South African official.

Woods met with South African Minister of Police James "Jimmy" Kruger to request the easing of Biko's banning order—a request that was promptly ignored and led to further harassment and arrests of Biko, as well as a harassment campaign against Woods that eventually caused him to flee the country.

Despite the harassment, Biko, from King William's Town, helped set up the Zimele Trust Fund which assisted political prisoners and their families. He was also elected honorary president of the BPC in January 1977.

Detention and Murder

Biko was detained and interrogated four times between August 1975 and September 1977 under Apartheid era anti-terrorism legislation. On August 21, 1977, Biko was detained by the Eastern Cape security police and held in Port Elizabeth. From the Walmer police cells, he was taken for interrogation at the security police headquarters. According to the "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa" report, on September 7, 1977:

"Biko sustained a head injury during interrogation, after which he acted strangely and was uncooperative. The doctors who examined him (naked, lying on a mat and manacled to a metal grille) initially disregarded overt signs of neurological injury. "

By September 11, Biko had slipped into a continual semi-conscious state and the police physician recommended a transfer to the hospital. Biko was, however, transported nearly 750 miles to Pretoria—a 12-hour journey, which he made lying naked in the back of a Land Rover. A few hours later, on September 12, alone and still naked, lying on the floor of a cell in the Pretoria Central Prison, Biko died from brain damage.

South African Minister of Justice Kruger initially suggested Biko had died of a hunger strike and said that his murder "left him cold." The hunger strike story was dropped after local and international media pressure, especially from Woods. It was revealed in the inquest that Biko had died of brain damage, but the magistrate failed to find anyone responsible. He ruled that Biko had died as a result of injuries sustained during a scuffle with security police while in detention.

Anti-Apartheid Martyr

The brutal circumstances of Biko's murder caused a worldwide outcry and he became a martyr and symbol of Black resistance to the oppressive apartheid regime. As a result, the South African government banned a number of individuals (including Woods) and organizations, especially those Black Consciousness groups closely associated with Biko.

The United Nations Security Council responded by imposing an arms embargo against South Africa. Biko's family sued the state for damages in 1979 and settled out of court for R65,000 (then equivalent to $25,000). The three doctors connected with Biko's case were initially exonerated by the South African Medical Disciplinary Committee.

It was not until a second inquiry in 1985, eight years after Biko's murder, that any action was taken against them. At that time, Dr. Benjamin Tucker who examined Biko before his murder lost his license to practice in South Africa. The police officers responsible for Biko's killing applied for amnesty during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings, which sat in Port Elizabeth in 1997, but the application was denied. The commission had a very specific purpose:

"The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was created to investigate gross human rights violations that were perpetrated during the period of the Apartheid regime from 1960 to 1994, including abductions, killings, torture. Its mandate covered both violations by both the state and the liberation movements and allowed the commission to hold special hearings focused on specific sectors, institutions, and individuals. Controversially the TRC was empowered to grant amnesty to perpetrators who confessed their crimes truthfully and completely to the commission.

(The commission) was comprised of seventeen commissioners: nine men and eight women. Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu chaired the commission. The commissioners were supported by approximately 300 staff members, divided into three committees (Human Rights Violations Committee, Amnesty Committee, and Reparations and Rehabilitation Committee)."

Biko's family did not ask the Commission to make a finding on his murder. The "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa" report, published by Macmillan in March 1999, said of Biko's murder:

"The Commission finds that the death in detention of Mr Stephen Bantu Biko on 12 September 1977 was a gross human rights violation. Magistrate Marthinus Prins found that the members of the SAP were not implicated in his death. The magistrate's finding contributed to the creation of a culture of impunity in the SAP. Despite the inquest finding no person responsible for his death, the Commission finds that, in view of the fact that Biko died in the custody of law enforcement officials, the probabilities are that he died as a result of injuries sustained during his detention."

Woods went on to write a biography of Biko, published in 1978, simply titled, "Biko." In 1987, Biko’s story was chronicled in the film “Cry Freedom,” which was based on Woods' book. The hit song " Biko ," by Peter Gabriel, honoring Steve Biko's legacy, came out in 1980. Of note, Woods, Sir Richard Attenborough (director of "Cry Freedom"), and Peter Gabriel—all White men—have had perhaps the most influence and control in the widespread telling of Biko's story, and have also profited from it. This is an important point to consider as we reflect on his legacy, which remains notably small when compared to more famous anti-apartheid leaders such as Mandela and Tutu. But Biko remains a model and hero in the struggle for autonomy and self-determination for people around the world. His writings, work, and tragic murder were all historically crucial to the momentum and success of the South African anti-apartheid movement.

In 1997, at the 20th anniversary of Biko's murder, then-South African President Mandela memorialized Biko, calling him "a proud representative of the re-awakening of a people" and adding:

“History called upon Steve Biko at a time when the political pulse of our people had been rendered faint by banning, imprisonment, exile, murder and banishment....While Steve Biko espoused, inspired, and promoted black pride, he never made blackness a fetish. At the end of the day, as he himself pointed out, accepting one’s blackness is a critical starting point: an important foundation for engaging in struggle."

- Biko, Steve. I Write What I Like . Bowerdean Press, 1978.

- “ Cry Freedom .” IMDb , IMDb.com, 6 Nov. 1987.

- “ Donald James Woods .” Donald James Woods | South African History Online , sahistory.org.

- Mangcu, Xolela. Biko, A Biography. Tafelberg, 2012.

- Sahoboss. “ Stephen Bantu Biko .” South African History Online , 4 Dec. 2017.

- “ Steve Biko: The Philosophy of Black Consciousness ." Black Star News, 20 Feb. 2020.

- Swarns, Rachel L. “ Donald Woods, 67, Editor and Apartheid Foe .” The New York Times , The New York Times, 20 Aug. 2001.

- Woods, Donald. Biko . Paddington Press, 1978.

“ Apartheid Police Officers Admit to the Killing of Biko before the TRC .” Apartheid Police Officers Admit to the Killing of Biko before the TRC | South African History Online , 28 Jan. 1997.

Daley, Suzanne. “ Panel Denies Amnesty for Four Officers in Steve Bikos Death .” The New York Times , The New York Times, 17 Feb. 1999.

“ Truth Commission: South Africa .” United States Institute of Peace , 22 Oct. 2018.

- Biography of Donald Woods, South African Journalist

- South Africa's Black Consciousness Movement in the 1970s

- Understanding South Africa's Apartheid Era

- What Was Apartheid in South Africa?

- Biography: Joe Slovo

- Biography of Nontsikelelo Albertina Sisulu, South African Activist

- The End of South African Apartheid

- Memorable Quotes by Steve Biko

- South Africa's Extension of University Education Act of 1959

- Biography of Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu, Anti-Apartheid Activist

- Women's Anti-Pass Law Campaigns in South Africa

- Apartheid 101

- Pass Laws During Apartheid

- Apartheid Quotes About Bantu Education

- The Origins of Apartheid in South Africa

- The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act

Steve Biko: The Black Consciousness Movement

The saso, bcp & bpc years.

By Steve Biko Foundation

Stephen Bantu Biko was an anti-apartheid activist in South Africa in the 1960s and 1970s. A student leader, he later founded the Black Consciousness Movement which would empower and mobilize much of the urban black population. Since his death in police custody, he has been called a martyr of the anti-apartheid movement. While living, his writings and activism attempted to empower black people, and he was famous for his slogan “black is beautiful”, which he described as meaning: “man, you are okay as you are, begin to look upon yourself as a human being”. Scroll on to learn more about this iconic figure and his pivotal role in the Black Consciousness Movement...

“Black Consciousness is an attitude of mind and a way of life, the most positive call to emanate from the black world for a long time” - Biko

1666/67 University of Natal SRC

On completion of his matric at St Francis College, Biko registered for a medical degree at the University of Natal’s Black Section. The University of Natal professed liberalism and was home to some of the leading intellectuals of that tradition. The University of Natal had also become a magnet attracting a number of former black educators, some of the most academically capable members of black society, who had been removed from black colleges by the University Act of 1959. The University of Natal also attracted as law and medical students some of the brightest men and women from various parts of the country and from various political traditions. Their convergence at the University of Natal in the 1960s turned the University into a veritable intellectual hub, characterised by a diverse culture of vibrant political discourse. The University thus became the mainstay of what came to be known as the Durban Moment.

At Natal Biko hit the ground running. He was immediately influenced by, and in turn, influenced this dynamic environment. He was elected to serve on the Student's Representative Council (SRC) of 1966/67, in the year of his admission. Although he initially supported multiracial student groupings, principally the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), a number of voices on campus were radically opposed to NUSAS, through which black students had tried for years to have their voices heard but to no avail. This kind of frustration with white liberalism was not altogether unknown to Steve Biko, who had experienced similar disappointment at Lovedale.

Medical Students at the University of Natal (Left to Right: Brigette Savage, Rogers Ragavan, Ben Ngubane, Steve Biko)

Correspondence designating Biko as an SRC delegate at the annual NUSAS Conference

In 1967, Biko participated as an SRC delegate at the annual NUSAS conference held at Rhodes University. A dispute arose at the conference when the host institution prohibited racially mixed accommodation in obedience to the Group Areas Act, one of the laws under apartheid that NUSAS professed to abhor but would not oppose. Instead NUSAS opted to drive on both sides of the road: it condemned Rhodes University officials while cautioning black delegates to act within the limits of the law. For Biko this was another defining moment that struck a raw nerve in him.

Speech by Dr. Saleem Badat, author of Black Man You Are on Your Own, on SASO

Reacting angrily, Biko slated the artificial integration of student politics and rejected liberalism as empty echoes by people who were not committed to rattling the status quo but who skilfully extracted what best suited them “from the exclusive pool of white privileges”. This gave rise to what became known as the Best-able debate: Were white liberals the people best able to define the tempo and texture of black resistance? This debate had a double thrust. On the one hand, it was aimed at disabusing white society of its superiority complex and challenged the liberal establishment to rethink its presumed role as the mouthpiece of the oppressed. On the other, it was designed as an equally frank critique of black society, targeting its passivity that cast blacks in the role of “spectators” in the course of history. The 7th April 1960 saw the banning of the African National Congress and the Pan African Congress and the imprisonment of the leadership of the liberation movement had created a culture of apathy

Bantu Stephen Biko

“ We have set out on a quest for true humanity, and somewhere on the distant horizon we can see the glittering prize. Let us march forth with courage and determination, drawing strength from our common plight and our brotherhood. In time we shall be in a position to bestow upon South Africa the greatest gift possible - a more human face.”

Biko argued that true liberation was possible only when black people were, themselves, agents of change. In his view, this agency was a function of a new identity and consciousness, which was devoid of the inferiority complex that plagued black society. Only when white and black societies addressed issues of race openly would there be some hope for genuine integration and non-racialism.

Transcript of a 1972 Interview with Biko

At the University Christian Movement (UCM) meeting at Stutterheim in 1968, Biko made further inroads into black student politics by targeting key individuals and harnessing support for an exclusively black movement. In 1969, at the University of the North near Pietersburg, and with students of the University of Natal playing a leading role, African students launched a blacks-only student organisation, the South African Student Organisation (SASO). SASO committed itself to the philosophy of black consciousness. Biko was elected president.

Black Student Manifesto

The idea that blacks could define and organise themselves and determine their own destiny through a new political and cultural identity rooted in black consciousness swept through most black campuses, among those who had experienced the frustrations of years of deference to whites. In a short time, SASO became closely identified with 'Black Power' and African humanism and was reinforced by ideas emanating from Diasporan Africa. Successes elsewhere on the continent, which saw a number of countries, achieve independence from their colonial masters also fed into the language of black consciousness.

SASO's Definition of Black Consciousness

Cover of a 1971 SASO Newsletter

“ In 1968 we started forming what is now called SASO... which was firmly based on Black Consciousness, the essence of which was for the black man to elevate his own position by positively looking at those value systems that make him distinctively a man in society” - Biko

Cover of a 1971 SASO Newsletter

Cover of a 1972 SASO Newsletter

Cover of SASO newsletter, 1973

Cover of a 1975 SASO Newsletter

Steve Biko speaks on BCM

The Black People’s Convention By 1971, the influence of SASO had spread well beyond tertiary education campuses. A growing body of people who were part of SASO were also exiting the university system and needed a political home. SASO leaders moved for the establishment of a new wing of their organisation that would embrace broader civil society. The Black People’s Convention (BPC) with just such an aim was launched in 1972. The BPC immediately addressed the problems of black workers, whose unions were not yet recognised by the law. This invariably set the new organisation on a collision path with the security forces. By the end of the year, however, forty-one branches were said to exist. Black church leaders, artists, organised labour and others were becoming increasingly politicised and, despite the banning in 1973 of some of the leading figures in the movement, black consciousness exponents became most outspoken, courageous and provocative in their defiance of white supremacy.

BPC Membership Card

Minutes of the first meeting of the Black People's Convention

In 1974 nine leaders of SASO and BPC were charged with fomenting unrest. The accused used the seventeen-month trial as a platform to state the case of black consciousness in a trial that became known as the Trial of Ideas. They were found guilty and sentenced to various terms of imprisonment, although acquitted on the main charge of being party to a revolutionary conspiracy.

SASO/BPC Trial Coverage SASO/BPC Trial Coverage BPC Members

SASO/BPC Coverage

Poster from the 1974 Viva Frelimo Rally

Their conviction simply strengthened the black consciousness movement. Growing influence led to the formation of the South African Students Movement (SASM), which targeted and organised at high school level. SASM was to play a pivotal role in the student uprisings of 1976.

Barney Pityana, Founding SASO Member

In 1972, the year of the birth of the BPC, Biko was expelled from medical school. His political activities had taken a toll on his studies. More importantly, however, according to his friend and comrade Barney Pityana, “his own expansive search for knowledge had gone well beyond the field of medicine.” Biko would later go on to study law through the University of South Africa.

Steve Biko's Order Form for Law Textbooks

Upon leaving university, Biko joined the Durban offices of the Black Community Programmes (BCP), the developmental wing of the Black People Convention, as an employee reporting to Ben Khoapa. The Black Community Programmes engaged in a number of community-based projects and published a yearly called Black Review, which provided an analysis of political trends in the country.

Black Community Programmes Pamphlet

Overview of the BCP

BCP Head, Ben Khoapa

86 Beatrice Street, Former Headquarters of the BCP

"To understand me correctly you have to say that there were no fears expressed" - Biko

Ben Khoapa, Beatrice Street Circa 2007

Biko's Banning Order

When Biko was banned in March 1973, along with Khoapa, Pityana and others, he was deported from Durban to his home town, King William’s Town. Many of the other leaders of SASO, BPC, and BCP were relocated to disparate and isolated locations. Apart from assaulting the capacity of the organisations to function, the bannings were also intended to break the spirit of individual leaders, many of whom would be rendered inactive by the accompanying banning restrictions and thus waste away.

Following his banning, Biko targeted local organic intellectuals whom he engaged with as much vigour as he had engaged the more academic intellectuals at the University of Natal. Only this time, the focus was on giving depth to the practical dimension of BC ideas on development, which had been birthed within SASO and the BPC. He set up the King William’s Town office (No 15 Leopold Street) of the Black Community Programmes office where he stood as Branch Executive. The organisation focused on projects in Health, Education, Job Creation and other areas of community development.

No 15 Leopold Street , Former King William's Town Offices of the BCP

It was not long before his banning order was amended to restrict him from any meaningful association with the BCP. Biko could not meet with more that one person at a time. He could not leave the magisterial area of King William’s Town without permission from the police. He could not participate in public functions nor could he be published or quoted.

Zanempilo Clinic, a BPC Clinic

These restrictions on him and others in the BCM and their regular arrests, forced the development of a multiplicity of layers of leadership within the organisation in order to increase the buoyancy of the organisation. Notwithstanding the challenges, the local Black Community Programme office did well, managing among other achievements to build and operate Zanempilo Clinic, the most advanced community health centre of its time built without public funding. According to Dr. Ramphele, “it was a statement intended to demonstrate how little, with proper planning and organisation, it takes to deliver the most basic of services to our people.” Dr. Ramphele and Dr. Solombela served as resident doctors at Zanempilo Clinic.

Community Member from Njwaxa

Other projects under Biko’s office included Njwaxa Leatherworks Project, a community crèche and a number of other initiatives. Biko was also instrumental in founding in 1975 the Zimele Trust Fund set up to assist political prisoners and their families. Zimele Trust did not discriminate on the basis of party affiliation. In addition, Biko set up the Ginsberg Educational Trust to assist black students. This trust was also a plough-back to a community that had once assisted him with his own education.

Click on the Steve Biko Foundation logo to continue your journey into Biko's extraordinary life. Take a look at Steve Biko: The Black Consciousness Movement, Steve Biko: The Final Days, and Steve Biko: The Legacy.

—Steve Biko Foundation:

Steve Biko: The Inquest

Steve biko foundation, 11 february 1990: mandela's release from prison, africa media online, detention without trial in john vorster square, south african history archive (saha), what happened at the treason trial, steve biko: final days, 9 august 1956: the women's anti-pass march, steve biko: the early years, the signs that defined the apartheid, steve biko: legacy, leadership during the rise and fall of apartheid.

- Submissions

- Video and audio

- Development

- Book Reviews

Mubarak Aliyu

August 19th, 2021, steve biko and the philosophy of black consciousness.

5 comments | 644 shares

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

The Black Consciousness Movement pioneered by Steve Biko played a crucial role in the resistance to Apartheid in South Africa. Pursuing broad coalitions alongside ideas of Black theology and indigenous values, Biko’s role in the anti-Apartheid struggle can be read as one of philosopher as much as activist.

This post is a winning entry in the lse student writing competition black forgotten heroes , launched by the firoz lalji institute for africa ..

Born 18 December 1946, Steve Biko was a South African activist who pioneered the philosophy of Black Consciousness in the late 1960s. He later founded the South African Students Organisation (SASO) in 1968, in an effort to represent the interests of Black students in the then University of Natal (later KwaZulu-Natal). SASO was a direct response to what Biko saw as the inaction of the National Union of South African Students in representing the needs of Black students.

Biko’s experiences under Apartheid drove his philosophy and political activism. He had witnessed police raids during his childhood and lived through the brutality and intimidation the Apartheid government was known for. Biko’s philosophy focused primarily on liberating the minds of Black people who had been relegated to an inferior status by white power structures, seeing the power struggle in South Africa as ‘a microcosm of the confrontation between the third world and the first world’.

The philosophy of Black consciousness

The Black Consciousness Movement centred on race as a determining factor in the oppression of Black people in South Africa, in response to racial oppression and the dehumanisation of Black people under Apartheid. ‘Black’ as defined by Biko was not limited to Africans, but also included Asians and ‘coloureds’ (South Africans of mixed race including African, European and/or Asian origin), incorporating Black Theology, indigenous values and political organisation against the ruling system.

The movement viewed the liberation of the mind as the primary weapon in the fight for freedom in South Africa, defining Black consciousness as, first, an inward-looking process, where Black people regain the pride stripped away from them by the Apartheid system. His philosophy casts a positive retelling of African history, which has been heavily distorted and vilified by European imperialists in an attempt to construct their colonies. In his writings, he notes that ‘[a] people without a positive history is like a vehicle without an engine’.

At the heart of this thinking is the realisation by blacks that the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed

A necessary step towards restoring dignity to Black people, according to Biko, involves elevating the heroes of African history and promoting African heritage to deconstruct the idea of Africa as the dark continent. Black consciousness seeks to extract the positive values within indigenous African cultures and to make it a standard with which Black people judge themselves – the first form of resistance towards imperialism and Apartheid. According to Biko, ‘what black consciousness seeks to do is to produce at the output end of the process, real black people who do not consider themselves as appendages to white society’.

In Apartheid South Africa, Black consciousness aimed to unite citizens under the main cause of their oppression. Biko’s philosophy goes further to introduce the concept of Black theology, arguing the message in Christianity needs to be taught from the perspective of the oppressed to fit the journey of Black people’s self-realisation. According to Biko, Black theology must preach that it is a sin to allow oneself to be oppressed. Adapting Christianity to African values and belief systems is at the core of doing away with ‘spiritual poverty’.

In 1972, Biko founded the Black People’s Convention as an umbrella organisation for the Black Consciousness Movement, which had begun sweeping through universities across the nation. One year later, he and eight other leaders of the movement were banned by the South African government, which limited Biko to his home of King William’s Town. He continued to defy the banning order, however, by supporting the Convention, leading to several arrests in the following years.

On 21 August 1977, Biko was detained by the police and held at the eastern city of Port Elizabeth, where he was violently tortured and interrogated. By 11 September, he was found naked and chained to a prison cell door. He died in a hospital cell the following day as a result of brain injuries sustained at the hands of the police. Although the details of his torture remain unknown, Biko’s death has been understood by many South Africans as an assassination.

Black consciousness was beyond a movement; it was a philosophy deeply grounded in African Humanism, for which Biko should be considered not only an activist but a philosopher in his own right. His legacy remains one deeply relevant today – of resistance and self-determination in the face of widespread oppression.

All quotes are taken from Steve Biko’s selected writings in his book ‘I write what I like’ .

Photo : Steve Biko . Stained glass window by Daan Wildschut in the Saint Anna Church, Heerlen (the Netherlands), ca. 1976. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 .

About the author

Mubarak Aliyu is an MSc Development Studies candidate at LSE, with a specialism in African Development. His research interests include education reform, indigenous knowledge systems and grassroots political organisation.

Black history should be spread to empire the youth of Africans and erase the mind motive of slavery

The Born Frees ( Everyone Who Is Born During The State Of Independence Of South Africa ) Of South Africa Should Acknowledge Historical Legitimate Activists As Honoured Egalitarians And Patriots Who Fought For Freedom, Liberty & The Downfall Of Apartheid Regime. Those Legends Fought For Our Rights And Privileges We Are Currently Enjoying.

I’m The Top Learner (Historian) Of Mavalani High School Which Is Located South Africa In Limpopo.

This really helped me in my biography project and i got 85%

Thank you so much for the summary. I’m assisting a grade 5 learner with her school project

As a black South African woman in her 50s, I think it is every child’s right to know who they are. Black consciousness was and still is necessary. I’m saddened by what the apartheid regime did to us.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Celebrating the life and legacy of wangari maathai july 30th, 2021, related posts.

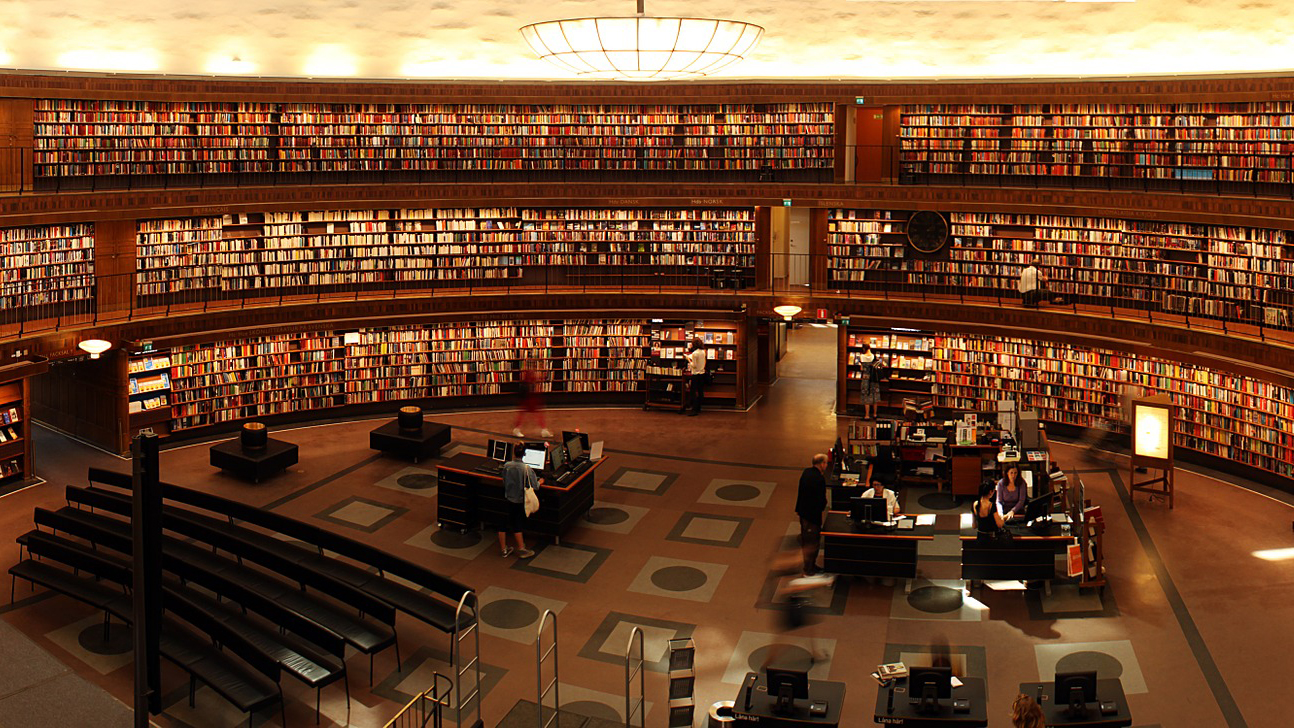

How to decolonize the library

June 27th, 2019.

How diverse is your reading list? (Probably not very…)

March 12th, 2019.

Knowledge production in international trade negotiations is a high stakes game

June 14th, 2019.

Decolonizing scholarly data and publishing infrastructures

May 29th, 2019.

Bad Behavior has blocked 141066 access attempts in the last 7 days.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Diaspora

- Afrocentrism

- Archaeology

- Central Africa

- Colonial Conquest and Rule

- Cultural History

- Early States and State Formation in Africa

- East Africa and Indian Ocean

- Economic History

- Historical Linguistics

- Historical Preservation and Cultural Heritage

- Historiography and Methods

- Image of Africa

- Intellectual History

- Invention of Tradition

- Language and History

- Legal History

- Medical History

- Military History

- North Africa and the Gulf

- Northeastern Africa

- Oral Traditions

- Political History

- Religious History

- Slavery and Slave Trade

- Social History

- Southern Africa

- West Africa

- Women’s History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Steve biko and the black consciousness movement.

- Leslie Anne Hadfield Leslie Anne Hadfield Department of History, Brigham Young University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.83

- Published online: 27 February 2017

The Black Consciousness movement of South Africa instigated a social, cultural, and political awakening in the country in the 1970s. By the mid-1960s, major anti-apartheid organizations in South Africa such as the African National Congress and Pan-Africanist Congress had been virtually silenced by government repression. In 1969, Steve Biko and other black students frustrated with white leadership in multi-racial student organizations formed an exclusively black association. Out of the South African Students’ Organization (SASO) came what was termed Black Consciousness. This philosophy redefined “black” as an inclusive, positive identity and taught that black South Africans could make meaningful change in their society if “conscientized” or awakened to their self-worth and the need for activism. The movement emboldened youth, contributed to the development of Black Theology and cultural movements, and led to the formation of new community and political organizations such as the Black Community Programs organization and the Black People’s Convention.

Articulate and charismatic, Steve Biko was one of the movement’s foremost instigators and prolific writers. When the South African government understood the threat Black Consciousness posed to apartheid, it worked to silence the movement and its leaders. Biko was banished to his home district in the Eastern Cape, where he continued to build community development programs and have a strong political influence. His death at the hands of security police in September 1977 revealed the brutality of South African security forces and the extent to which the state would go to maintain white supremacy. After Biko’s death, the state declared Black Consciousness–related organizations illegal. Activists formed the Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPO) in 1978 to carry on Black Consciousness ideals, though the movement in general waned after Biko’s death. Since then, Biko has loomed over the history of the Black Consciousness movement as a powerful icon and celebrated hero while others have looked to Black Consciousness in forging a new black future for South Africa.

- Black Consciousness

- South African Student’s Organization

- liberation movements

The Rise of Black Consciousness

The Black Consciousness movement became one of the most influential anti-apartheid movements of the 1970s in South Africa. While many parts of the African continent gained independence, the apartheid state increased its repression of black liberation movements in the 1960s. In the latter part of the decade, the major anti-apartheid organizations worked underground or in exile. The state also increased its extra-legal tactics of intimidation, silencing some activists by kidnapping or killing them. This state action crippled anti-apartheid activity and instilled a sense of fear in the larger black community. The state also began creating so-called homelands—small reserves intended to become independent countries for specific ethnic groups to curb black political opposition and urbanization while retaining access to black labor. All of this perpetuated deep-seated cultural racism in South Africa.

As state repression increased, universities and churches tended to have greater freedom to speak out against the government and facilitated the sharing of ideas. The 1960s saw an increase in Christian social movements and growing opposition to apartheid in churches and ecumenical organizations. Both economic prosperity and greater government control led to higher numbers of black students in primary and secondary schools and the expansion of black universities, segregated according to ethnicity. Although apartheid education restricted black aspirations, these schools also became places of politicization where black students could come together and share ideas and experiences. These elements along with the daily experiences and interpretations of individuals who made up the Black Consciousness movement all contributed to its growth. As emerging young adults unencumbered by the fear of older generations, these activists looked for a way to fundamentally change their society. They did this first by targeting the mind of black people in South Africa. But the movement was also about immediate and relevant action that would make South Africans self-reliant. In other words, it sought a full liberation of black South Africans by starting at the level of the individual, an approach not overtly political to begin with.

SASO and Black Consciousness

The beginning of the movement is marked by the formation of the South African Students’ Organization (SASO), officially launched in July 1969 . Black students at various universities, especially at the University of Natal Medical School–Black Section (UNB), the University of Fort Hare, and the University of the North at Turfloop, became increasingly frustrated with the limits of white student leadership in multiracial organizations. At a National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) meeting held in Grahamstown in 1967 and a University Christian Movement (UCM) conference in Stutterheim in July 1968 , the mostly white leadership would not act decisively to challenge the enforced racial segregation of accommodations for the students at the conference. Led primarily by Steve Biko and Barney Pityana, black students decided to form an exclusively black organization to more effectively advance the cause of the oppressed in South Africa.

SASO laid the foundation for what would grow beyond universities and student groups to become a wider movement. It was in SASO that activists formulated the Black Consciousness philosophy. SASO students also started engaging in community development programs and artistic and literary production and eventually moved into political defiance against the state.

Members of SASO as university students had access to a number of different ideas and engaged with each other—students who came to universities with diverse backgrounds, but similar experiences. They also had access to news media and reading materials through student-activist networks. As they debated and read materials from various parts of Africa and the African diaspora, these students formulated what they began to call Black Consciousness. In addition to the influences of various South African perspectives and their experience in student politics, a number of philosophers and leaders from the African continent and the African diaspora helped shape their thinking. Daniel Magaziner described them as “autonomous shoppers in the marketplace of ideas.” 1 SASO students studied Franz Fanon’s analysis of the psychological impact of colonialism, Jean-Paul Sartre’s dialectical analysis, Zambia’s K. K. Kaunda’s African humanism, and Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere’s version of African socialism that emphasized self-reliance and development for liberation. They also read from black American authors, particularly identifying with the Black Power movement (even adopting the raised fist as a gesture of black pride in South Africa) and analyzing the Black Theology of James Cone. SASO students also drew upon the writings of Brazil’s educationalist, Paulo Freire, from which they derived the idea of “to conscientize”—to awaken people to a critical awareness of their situation and their ability to change their situation.

Black Consciousness began to be defined as “an attitude of mind” or “way of life” of black people who believed in their potential and value as black people and saw the need for black people to work together for a holistic liberation. SASO students explained South Africa’s main problem as twofold: white racism and black acquiescence to that racism. They felt that in general, black people had accepted their own inferiority in society. Without a positive, creative sense of self, black people would not challenge the status quo. “The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor [was] the mind of the oppressed,” Biko argued. 2 Thus, Black Consciousness activists worked to change the black mindset, to look inward to build black capacity to realize their own liberation. Biko wrote that colonialism, missionaries, and apartheid had made the black man “a shell, a shadow of man, completely defeated, drowning in his own misery, a slave, an ox bearing the yoke of oppression with sheepish timidity.” He continued:

This is the first truth, bitter as it may seem, that we have to acknowledge before we can start on any programme [ sic ] designed to change the status quo…. The first step therefore is to make the black man come to himself; to pump back life into his empty shell; to infuse him with pride and dignity, to remind him of his complicity in the crime of allowing himself to be misused and therefore letting evil reign supreme in the country of his birth. 3

In affecting a black psychological, social, economic, and even spiritual liberation, activists saw two aspects as vitally important. First, they defined black as a new positive definition that included all people of color discriminated against by the color of their skin. This was a new approach to grouping people divided into apartheid into Coloureds (mixed-race people), Indians, and various black African ethnic groups. They wanted to make South Africa African in the end (though they had a vaguely defined future) but used a political definition of black that referred to a shared experience and outlook that was more cosmopolitan in celebrating black values and culture. A positive black identity would increase black people’s faith in their own potential. Black unity also presented a stronger front against apartheid. SASO came to strongly reject the participation of black South Africans in any apartheid institution that emphasized ethnic separation (including the so-called African homelands). Second, Black Consciousness activists rejected white liberals (whom they defined as any white person seeking to oppose apartheid). They saw white leadership as an obstacle to black liberation because it stifled black leadership and psychological development. As black people understood fully the oppression they experienced firsthand, activists believed they had the insights and knowledge to know what needed to change. White leadership would hinder the development of a truly self-reliant, black society. The phrase “Black man you are on your own” became a slogan of the movement. For many people, including white liberals, this came across as abrasive and startling. Some even accused SASO of promoting reverse racism. For others, it led to a refreshing, emboldened new consciousness.

SASO began with a few black students who worked to recruit other students across black campuses. This was not always easy, but strongholds developed at the University of the North, Zululand, Fort Hare, the Western Cape, and in Durban. SASO students in these various universities traveled around trying to prompt a psychological change among blacks in a number of ways. From the beginning of SASO, students engaged in community work. This began as a way to relieve the suffering of black people in poverty. Yet community projects were also seen as a way to uplift black communities psychologically as well as to improve black self-reliance. Each campus group ran projects in neighboring communities, such as volunteering in local clinics, helping to secure a clean water supply, and running education and literacy programs. The students learned from their experiences and drew upon the methodologies of Freire in particular to help them refine this work.

SASO also spread Black Consciousness through the SASO Newsletter , wherein activists described their philosophy, shared news, and dealt with the nature of their oppression. Asserting the right to speak was important for these activists and they claimed this right in the newsletter, along with other literary forms such as poems and plays. The newsletter also reported on various student meetings where students developed their thinking, debated strategies for the future, and discussed how to engage with the broader community. So-called formation schools—weekend or holiday camps—served as training grounds where students debated societal issues and learned organizational strategies. Acutely aware of the politically hostile environment within which it worked, SASO made it a point to train a number of layers of leadership to ensure the organization would continue if state repression were to hit.

A marker of the “attitude” and “way of life” of Black Consciousness activists was the way they carried themselves. The clothes they wore, their demeanor when interacting with white people, and the music they listened to all portrayed confidence and pride in blackness. The young women involved in the Black Consciousness especially challenged the status quo with new styles by throwing away their skin-lightening creams and wigs and wearing their hair in natural Afros. They also wore bold styles in clothing that pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable at the time, such as very tight pants. Some even smoked cigarettes in public. Though female students were involved in the movement from the beginning—prominent SASO women include Vuyelwa Mashalaba, Deborah Matshoba, Daphne Matshoba, Lindelwe Mabandla, Mamphela Ramphele, Thenjiwe Mthintso—the movement was dominated by male students. Women’s issues were tabled in favor of focusing on black liberation. Female activists had to excel at male ways of debating to gain an influence in SASO. The students also held parties where young women were treated more as objects of sexual desire. For some, this means that women had more conservative roles in the movement; however, some women did gain leadership in the movement, especially in community projects where they challenged conventional gender roles.

The Broader Movement

Before the state took action to suppress Black Consciousness, its influence had expanded beyond university campuses. With the spread of ideas and expansion of organizations linked to Black Consciousness, what began as a student organization grew into a movement with a broad, diffused impact that can be difficult to generalize about or trace precisely.

Cultural Movement

The movement had cultural dimensions, linked in varying degrees to formal organizations. Black Consciousness ideas resonated with poets and theater groups in particular. Some worked directly with SASO. For example, a group of black students and actors from Durban, many of Indian descent, performed their plays at SASO events (these activists formed the Theatre Council of Natal or TECON as well as the South African Black Theatre Union or SABTU). Their plays, such as Black on White and Resurrection , examined what it meant to be black and oppressed in South Africa. Participants and playwrights such as Asha Rambally Moodley and Strinivasa Moodley joined Black Consciousness organizations, while others simply continued to use theater as a way to raise a critical awareness among black communities. Poets such as Oswald Mtshali, Mongane Wally Serote, Don Mattera, Mafika Pascal Gwala, and James Matthews, among others, similarly dealt with black oppression and sought to inspire hope in black self-determination with positive images and themes of resistance and redemption. Black Consciousness promoted music with black themes and origins and influenced the outlook and material in Sowetan literary magazines, such as The Classic , New Classic , and Staffrider . 4 As Mbulelo Mzamane has argued, Black Consciousness effectively used culture as a form of affecting a black awakening and resisting white supremacy in an oppressive political climate. 5

Black Theology

Black Consciousness also contributed to the development of Black Theology in South Africa. Ecumenical organizations, Christian activists, and Black Consciousness adherents all influenced each other. The University Christian Movement (UCM) established a project spearheaded by Sabelo Stanley Ntwasa on Black Theology coming from the United States—an interpretation of Christianity that taught that Christ came to liberate the poor and oppressed, the black populations in the United States and South Africa. SASO joined the UCM in engaging Black Theology in the South African context and resolved to influence a change in leadership in South African churches. SASO and other Black Consciousness organizations supported conferences focused on examining Christianity’s relevancy to black South Africans. 6 A number of those influenced by Black Theology later became leaders of Christian resistance and contextual theology, such as Alphaeus Zulu, Manas Buthelezi, Desmond Tutu, Allan Boesak, and Frank Chikane. Activists worked closely with radical priests and ecumenical organizations, significantly putting these Christian ideals into action. 7

Black Community Programs

In September of 1971 , the Christian Institute and the South African Council of Churches appointed Bennie Khoapa as the director of a division of their Special Project on Christian Action in Society (Spro-cas 2). As the head of the Black Community Programs (BCP), Khoapa combined Christian action with the Black Consciousness philosophy. The organization sought to coordinate among other agencies run by and in the black community and to conscientize black South Africans through publication projects that provided relevant news for black people and promoted a positive black identity. The BCP eventually moved to run its own projects when activists working for the organization found themselves restricted to their home areas by banning orders in 1973 . For example, it ran health clinics such as the Zanempilo Community Health Center in the Eastern Cape, managed cottage industries like the Njwaxa leatherwork factory also in the Eastern Cape, and opened resource centers at its regional offices. It published a yearbook, Black Review . The BCP gave practical expression to Black Consciousness ideals. BCP publications encouraged black publishing in South Africa and became a trusted source of positive information in black communities. Research in villages where the BCP ran its projects has demonstrated that health and economic projects in the Eastern Cape improved black people’s physical conditions and helped villagers gain a greater sense of human dignity. Through this work, the BCP also significantly addressed women’s issues and female activists proved themselves as capable leaders and respected colleagues. 8