Interventions to improve nurses' job satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 Research Unit of Nursing Science and Health Management, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland.

- 2 Azienda per l'Assistenza Sanitaria n. 5 "Friuli Occidentale", Pordenone, Italy.

- 3 Center for Life Course Health Research, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland.

- 4 Medical Research Center Oulu, Oulu University Hospital and University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland.

- 5 Nursing Research Foundation, Helsinki, Finland.

- 6 The Finnish Centre for Evidence-Based Health Care, Helsinki, Finland.

- 7 WHO Collaborating Centre for Nursing, Helsinki, Finland.

- 8 Oulu University of Applied Sciences, Oulu, Finland.

- 9 Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District, Finland.

- PMID: 32128864

- DOI: 10.1111/jan.14342

Abstract in English, Chinese

Aims: To identify current best evidence on the types of interventions that have been developed to improve job satisfaction among nurses and on the effectiveness of these interventions.

Design: The systematic review is a quantitative systematic review and meta-analysis following a profile-likelihood random-effects model.

Data sources: CINAHL, Medic, and Pubmed (Medline).

Review methods: PICOS eligibility criteria were used to select original studies published between 2003-2019. The articles were screened by title (N = 489), abstract (N = 61), and full-text (N = 47). A total of 20 articles remained after the full-text screening process and further assess on risk of bias. The screening process was conducted by two authors independently and finally agreed together. A meta-analysis was performed to determine how the identified interventions influence nurses' job satisfaction.

Results: The interventions were primarily educational and consisted of workshops, educational sessions, lessons, and training sessions. The postintervention differences between intervention and control groups in meta-analysis revealed that two interventions significantly improved nurses' job satisfaction. Notably, the spiritual intelligence training protocol and Professional Identity Development Program were found to be effective in improving job satisfaction.

Conclusion: Healthcare organizations and managers should consider implementing effective interventions to improve nurses' job satisfaction and reduce turnover. The results reported in this study highlight that nurse managers should focus on organizational strategies that will foster the intrinsic motivation of employees.

Impact: The current nursing shortage and increased turnover intentions are proving to be a global problem. For this reason, it is imperative that nurse managers plan strategies to improve nurses´ job satisfaction. The effective interventions detected in this study are a first step for developing human resource strategies for healthcare organizations. These findings propose that extrinsic factors (e.g., salary and rewards) will never be as effective in maintaining job satisfaction as intrinsic factors (e.g., spiritual intelligence, professional identity, and awareness).

目的: 识别提高护士工作满意度的介入治疗类型及其有效性的现有最佳证据。 设计: 系统综述指的是遵循子集似然随机效应模型的定量系统综述与荟萃分析。 数据来源: CINAHL护理学数据库、Medic国际医疗器械展览会和Pubmed文献服务检索系统(Medline联机医学文献分析和检索系统)。 审查方法: 采用PICOS合格标准用于甄选2003年至2019年期间发表的原创研究。按照标题(N=489)、摘要(N=61)和全文(N=47)对文章进行筛选。在完成全文筛选后,留下20篇文章,进一步评估偏倚风险。由两位作者独立进行筛选过程,并最终达成一致。并且还要进行荟萃分析,以探讨所确定的介入治疗对护士工作满意度的影响。 结果: 介入治疗以教育为主,包括讲习班、教育班、上课和培训班。通过荟萃分析,从干预后介入治疗组与对照组的差异可以看出,两种介入治疗显著提高了护士的工作满意度。值得注意的是,灵性智力训练方案和职业认同发展计划能够行之有效地提高工作满意度。 结论: 医疗机构和管理者应考虑实施有效的介入治疗,以提高护士的工作满意度,减少离职率。本研究报告的结果强调,护士部门的管理人员应当侧重能够培养护士内在动机的组织策略。 影响: 当下医护人员的短缺和离职意愿的攀升被证明是一个全球普遍化的问题。为此,护士部门的管理人员制定提高护士工作满意度的策略势在必行。本研究中发现的有效介入治疗是制定医疗机构人力资源战略的第一步。这些发现表明,在维持护士的工作满意度方面,外在因素(如工资和报酬)永远不及内在因素(如灵性智力、职业认同和认识)来得有效。.

Keywords: interventional study; job satisfaction; meta-analysis; nurses; systematic review.

© 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Publication types

- Meta-Analysis

- Systematic Review

- Job Satisfaction

- Nursing Staff, Hospital*

- Personnel Turnover

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 07 August 2018

Job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses in primary health care: an integrative review

- Elizabeth Halcomb ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8099-986X 1 ,

- Elizabeth Smyth 1 &

- Susan McInnes 1

BMC Family Practice volume 19 , Article number: 136 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

67 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

There has been a significant growth of the international primary health care (PHC) nursing workforce in recent decades in response to health system reform. However, there has been limited attention paid to strategic workforce growth and evaluation of workforce issues in this setting. Understanding issues like job satisfaction and career intentions are essential to building capacity and skill mix within the workforce. This review sought to explore the literature around job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses working in PHC.

An integrative review was conducted. Electronic databases including: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science, and reference lists of journal publications were searched for peer-reviewed literature published between 2000 and 2016 related to registered nurse job satisfaction and career intentions. Study quality was appraised, before thematic analysis was undertaken to synthesise the findings.

Twenty papers were included in this review. Levels of job satisfaction reported were variable between studies. A range of factors impacted on job satisfaction. Whilst there was agreement on the impact of some factors, there was a lack of consistency between studies on other factors. Four of the six studies which reported career intentions identified that nearly half of their participants intended to leave their current position.

This review identifies gaps in our understanding of job satisfaction and career intentions in PHC nurses. With the growth of the PHC nursing workforce internationally, there is a need for robust, longitudinal workforce research to ensure that employment in this setting is satisfying and that skilled nurses are retained.

Peer Review reports

The recruitment and retention of nurses is problematic worldwide. There is a maldistribution of human resources for health, a shortage in the overall number of qualified nurses and an aging nursing workforce [ 1 ]. Job satisfaction has been cited as an important factor contributing to the turnover of nurses and as an antecedent to nursing retention [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Therefore, understanding factors that impact on job satisfaction is important to inform recruitment and retention strategies.

The concept of job satisfaction is multifaceted and complex. Job satisfaction has been the focus of much research around organisational behaviour. Lu, et al. [ 5 ] define job satisfaction as not only how an individual feels about their job but also the nature of the job and the individuals’ expectation of what their job should provide. To this end, job satisfaction is comprised of various components, including; job conditions, communication, the nature of the work, organisational policies and procedures, remuneration and conditions, promotion / advancement opportunities, recognition / appreciation, security and supervision / relationships [ 5 ]. Whilst levels of job satisfaction vary, several common factors emerge across studies [ 6 , 7 ]. These include working conditions and the organisational environment, levels of stress, role conflict and ambiguity, role perceptions and content and organisational and professional commitment [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Given these factors it becomes clear that research about job satisfaction cannot be undertaken across the nursing profession as a whole, but rather needs to consider various settings and organisational environments to understand the issues facing different nursing groups.

Career intentions can be described as the intention to leave ones’ job voluntarily [ 9 ]. This process may start with a psychological response to negative situations in the workplace or undesirable aspects of the job. Subsequently, a cognitive decision is made to leave the position and withdrawal behaviours occur as the person moves out of the workplace [ 10 ]. Like job satisfaction, a number of common determinants for career intention have been identified. These include organisational factors, management style, workload and stress, role perceptions, empowerment, remuneration and employment conditions and opportunities for advancement [ 10 ]. In several studies, job satisfaction has been shown to impact on career intentions [ 11 , 12 ].

Despite the common themes in this workforce literature, much of the research around job satisfaction and career intentions reported to date has focussed on acute care nurses [ 2 , 5 , 6 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 ]. Given the impact of organisational factors, roles and employment conditions it is important to consider different groups of nurses, such as those employed in PHC, who are employed in settings unlike those of their acute care colleagues. PHC nurses practice in a range of settings, including general practices, schools, refugee health services, correctional settings, non-government organisations and community health centres [ 15 ]. As such, their employment conditions and work environments are unlike those of acute care nurses who are employed by large health providers or government funded health services (17). The small business nature of primary care in many countries and the predominance of charities and non-government health providers makes employment in the PHC setting unique [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Lorenz and De Brito Guirardello [ 19 ] describe the PHC work environment as “not always favourable to the professional practice of nurses”(p. 927), citing lack of equipment, inappropriate physical environment and occupational risks as key contributors to dissatisfaction. Additionally, there are significant difference between the roles, responsibilities and work environments of acute and PHC nurses [ 20 ]. These differences and the impact of such factors on job satisfaction and career intentions mean that acute care nursing workforce research cannot be simply generalised to the PHC setting. With the growth in the PHC nursing workforce and the need for a strong nursing workforce in this setting it is timely to explore the job satisfaction and career intentions of PHC nurses. Therefore, this review sought to critically synthesise the literature around the job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses working in PHC.

The underlying research questions are:

What was known about the main outcomes of studies regarding PHC registered nurses job satisfaction?

What was known about the career intentions of PHC registered nurses?

Registered nurses are the focus of the review as they are the largest nursing workforce in PHC [ 21 ].

This integrative literature review is informed by Whittemore and Knafls [ 22 ] framework. It provides a thorough examination of the existing literature following the five stages of review: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation [ 22 ].

Search strategy

A systematic search strategy was designed to guide the search of electronic databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science. Key search terms included; nurs*, primary health care, community care and job satisfaction or career intention. The search was confined to English language peer reviewed papers of original research. Given the significant changes in PHC systems internationally, only papers published between January 2000 and 2016 were considered. The reference lists of publications were also reviewed to identify further literature.

Inclusion criteria

Table 1 details the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Papers were excluded if they focussed on a particular nursing specialty (e.g. community mental health nurses) or were based in residential care settings (e.g. nursing homes), as the issues with this workforce are somewhat different to other PHC settings. Studies that focussed on nurse practitioners and/or advanced practice nurses (e.g. [ 23 ]), or specifically on nurse managers were excluded as these nurses may have different perceptions and experiences to registered nurses. Remoteness itself was not considered to constitute PHC nursing, therefore, papers focussed on rural or remote nurses without being specifically PHC focussed were excluded. Research articles were also excluded if the findings did not isolate PHC nurses from acute care nurses or other health professionals.

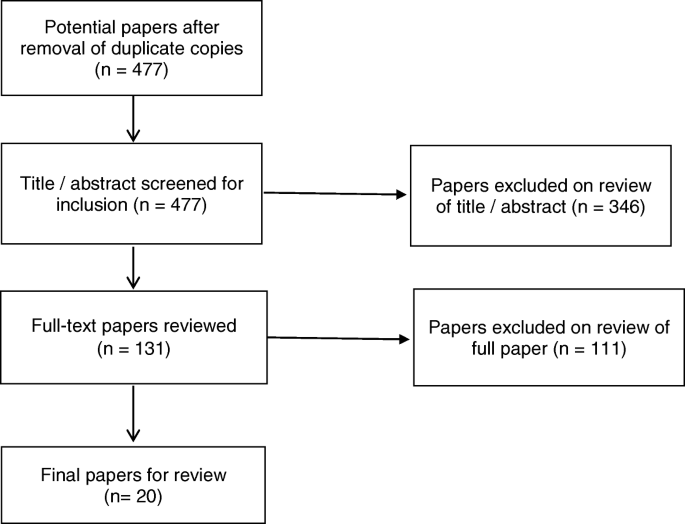

Study selection

After removal of duplicates, 477 citations were yielded from the search. These citations were exported to Endnote X8™ for review of their titles, followed by closer evaluation of the abstract. This process identified that 346 papers did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 131 papers where the full-text was retrieved. Of these papers, 111 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and so were excluded. This left 20 papers for inclusion in the review. (Fig. 1 ).

Process of paper selection – Prisma Flow diagram [ 24 ]

Appraisal of methodological quality

Determining the methodological quality of the included studies was difficult due to the broad sampling frame and various research designs [ 22 ]. As identified by Whittemore and Knafl [ 22 ], there is no gold standard for evaluating quality in research reviews. In this review we conducted quality appraisal using the tool provided by the Center for Evidence Based Management [ 25 ]. The major areas of concern were around the quality of reporting of the instrument development and validity / reliability measures in some papers [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Given the relatively small number of included papers and the minor nature of the limitations identified none of the studies were excluded based on their methodological quality.

Data abstraction and synthesis

Once the included papers were identified all data was abstracted into a summary table. The main characteristics that were extracted included;

Study design

Main outcomes related to job satisfaction or career intention

The nature of the included papers, in terms of the heterogeneity of the measures used, meant that thematic analysis was the most appropriate technique for aggregating the findings. Therefore, data is presented in a narrative form around the key themes that emerged from the literature.

Of the 20 included papers (Table 2 ), 15 (75%) described quantitative studies, 4 (20%) papers described qualitative projects, and the remaining paper (5%) employed a mixed-method approach. Most of the included papers reported research undertaken in Canada ( n = 8, 40%), with other studies coming out of the United Kingdom ( n = 4, 20%), the United States of America ( n = 5, 25%), one paper each from Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Brazil.

The sample sizes of included studies varied from 31 [ 30 ] to 1044 participants [ 26 ]. Participants spanned the scope of PHC and included community nurses, primary health nurses, general practice nurses, school nurses, and district nurses. In some studies the data from various primary care nursing groups was reported in an aggregated form [ 32 ], whilst in other papers there was an attempt to tease out the differences between groups [ 26 , 29 ].

Eleven (55%) papers focussed on job satisfaction only [ 27 , 28 , 30 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ], and three (15%) papers reported only data on career intention or turnover [ 31 , 32 , 41 ]. A further six (30%) papers combined measures of job satisfaction and career intention within the same study [ 2 , 19 , 26 , 29 , 42 , 43 ].

The key features and predominant findings of papers are summarised in Table 2 . Five overarching themes emerged, namely; levels of job satisfaction, factors that enhanced job satisfaction, factors that reduced levels of job satisfaction, career intentions, and, factors that impacted on career intentions.

Levels of job satisfaction

The variation in measurement of job satisfaction across studies and the differences in respondent characteristics makes comparison difficult. Most tools measured job satisfaction quantitatively using a Likert scale (agree to disagree) [ 2 , 19 , 26 , 37 , 38 , 39 ], whilst one study used qualitative data collected from focus groups and interviews [ 28 ]. Studies measured different aspects of job satisfaction including; overall satisfaction (enjoyment, pride), specific aspects of the job (pay, rewards, resources, task requirements, work conditions, training, quality of care, time) and supervision (authority, autonomy, feedback, appreciation, organisational policies, interaction).

In some studies just over half of the respondents were reported to be satisfied with their job [ 19 , 39 ], whilst in other studies a greater majority indicated that they were satisfied [ 28 ]. A small number of studies reported moderate [ 2 , 38 ] to low levels of satisfaction [ 37 , 42 ]. Those studies which reported lower levels of satisfaction used more items to measure satisfaction (42 items and 80 items respectively) [ 37 , 42 ], compared to studies reporting high levels of satisfaction which used only 4 items [ 19 , 39 ].

Factors influencing job satisfaction

The ten studies which explored the relationship between job satisfaction and demographics / professional variables demonstrated significant variation [ 2 , 19 , 29 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 43 ]. Whilst two studies found that age had no significant impact on job satisfaction [ 2 , 43 ], three others demonstrated that older nurses were more satisfied than their younger colleagues [ 29 , 37 , 38 ]. Similarly, there were variable findings related to the impact of education, with three papers finding no relationship with job satisfaction or inconclusive findings [ 2 , 36 , 37 ], and two papers demonstrating that nurses with higher educational qualifications had reported higher work satisfaction [ 34 , 40 ]. In contrast, Delobelle et al. [ 2 ] found that Nursing Assistants and Enrolled Nurses were more satisfied than Registered Nurses.

Curtis and Glacken [ 37 ] reported that those employed for over 10 years had a significantly higher level of job satisfaction than other nurses. However, other studies reported an inverse relationship between years worked in PHC and satisfaction [ 40 ] and no significant differences between satisfaction and years of nursing [ 2 ].

Other factors that positively contributed to satisfaction included control over clinical practice and decision-making [ 19 , 34 , 39 , 40 ], community satisfaction [ 43 ], organisational support [ 19 ], remuneration [ 38 ], and workload [ 39 ].

There was significant agreement between studies in terms of the factors that contributed positively to job satisfaction. These included the professional role, respect and recognition from clients and managers, workplace relationships, autonomy, access to resources and the flexibility of the role [ 2 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 37 , 43 ].

Factors negatively impacting job satisfaction

There was a high level of agreement amongst included studies about factors that negatively impacted respondents’ levels of satisfaction. Seven studies identified concerns about adequate remuneration [ 2 , 28 , 29 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 43 ]. When comparing hospital and community nurses, Campbell, et al. [ 34 ] identified that hospital nurses were significantly more likely than community nurses to be satisfied with their pay.

Another key factor identified in several studies related to the time pressures and high administrative workloads that impact on patient care [ 2 , 26 , 30 , 33 , 37 ]. Other factors identified to negatively impact job satisfaction included; a lack of recognition [ 2 , 28 , 33 , 34 ], poor role clarity [ 30 , 34 , 37 ] and poor organisational communication [ 29 , 34 ].

Career intentions

The included studies present an important picture around career intentions. However, caution needs to be applied in the interpretation of these data, as most studies comprise of an ageing workforce who will naturally retire in the near future. Six studies sought to explore the factors impacting on retention [ 2 , 32 , 34 , 41 , 42 , 43 ] The highest reported career intentions was reported by Delobelle, et al. [ 2 ] with half of all nurse participants ( n = 69; 51.1%) considering leaving PHC in the next 2 years. Both Betkus and MacLeod [ 43 ] and Almalki, et al. [ 42 ] also reported that nearly half (48 and 40%) intended to leave their current PHC job in the next year. Royer [ 32 ] similarly identified that some 46% of participants aged 35–45 years were considering leaving, and almost 40% of those aged 56–65 were thinking about leaving. The remaining two studies reported that few participants intended to leave their current position [ 34 , 41 ].

The findings of the three studies which explored job satisfaction and quality of worklife [ 2 , 42 , 43 ], lacked consistency. Almalki, et al. [ 42 ] demonstrated that quality of worklife was significantly related to turnover intent ( p < 0.001), however, this only explained 26% of the variance and was not included in the final model. Whilst Betkus and MacLeod [ 43 ] reported no correlation between job satisfaction and retention, Delobelle, et al. [ 2 ] found that turnover intent was significantly explained by job satisfaction, age and education ( p < 0.001). Other factors that were identified as having an impact on career intentions included gender [ 42 ], work environment [ 42 ], remuneration [ 42 ], education [ 2 , 41 , 42 ], satisfaction with supervision [ 2 ], feelings of isolation [ 41 ], length of time in position / years of experience [ 32 , 42 ].

This review provides the first synthesis of the literature around job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses working in PHC. Given the differences in organisational context, employment conditions and practice environment that likely impact job satisfaction and career intention [ 17 , 18 , 19 ] it is important that this group are explored beyond the context of the broader nursing workforce. Considering the imperatives to grow the workforce in PHC settings, to meet community demand, understanding this literature is important to inform both practice and policy. Dissatisfaction with nursing employment is reported in the broader nursing workforce literature. In their survey of 33,659 medical–surgical nurses across 12 European countries, Aiken, et al. [ 44 ] concluded that more than one in five nurses were dissatisfied with their employment. The variation in job satisfaction identified in this review highlights the need for further large well-designed longitudinal investigations of the PHC nurse workforce to monitor workforce issues, such as satisfaction and career intentions, over time. Given the links between nurse satisfaction and both retention and patient outcomes [ 44 ], this issue should be prioritised.

Our review demonstrated agreement between studies in terms of the positive impact of a professional role, respect, recognition, workplace relationships and autonomy upon job satisfaction. This is consistent with the acute care nursing literature where modifiable factors within the workplace have been demonstrated to influence both job and career satisfaction [ 45 ]. In their study, Nantsupawat, et al. [ 46 ] demonstrated that job dissatisfaction and intention to leave were significantly lower in nurses who worked in a better work environment. Similarly, in their systematic review, Cicolini, et al. [ 14 ] found a significant link between nurses empowerment and satisfaction. The significant role of such modifiable factors highlights an opportunity for managers, employers and policy makers to implement strategies which can improve the workplace and, subsequently, enhance satisfaction.

A key finding of this review was the negative impact of poor remuneration on job satisfaction. Whilst concerns about pay have been previously identified in the acute sector [ 44 , 47 ], the challenge of lower rates of pay in PHC compared to the acute sector has long been reported [ 17 , 48 ]. This review adds to the evidence-base around the impact of this disparity on the PHC nursing workforce and highlights the significant implications of not addressing this issue.

Our review also revealed that in many studies large numbers of nurses were intending to leave PHC employment in the near future [ 2 , 42 , 43 ]. This clearly has significant implications for the workforce and service delivery. However, measures of the factors affecting career intentions were variable across included studies as were findings. The difficulties in synthesising such disparate data have been previously identified in the acute care literature [ 13 ]. Despite this, there were clear similarities between our review and the broader literature around nurse turnover and intention to leave. In their systematic review of nurses intention to leave their employment, Chan, et al. [ 13 ] identified that intention to leave was impacted by a complex combination of organisational and individual factors. Organisational factors included the work environment, culture, commitment, work demands and social support. In contrast, individual factors related to job satisfaction, burnout and demographic factors. The complex interplay of multiple factors that underlie retention is probably the reason that retention is the highest when interventions such as mentoring and in-depth orientations are used to support staff [ 49 ].

In their study of acute care nurses Galletta, et al. [ 50 ] conclude that the quality of relationships among staff is an important factor in nurses’ decisions to leave. Interprofessional relationships in PHC have long been identified as presenting unique challenges [ 48 , 51 ]. The complex environment of PHC, whereby services are funded by small businesses or non-government agencies [ 52 ], combines with the relatively rapid shift towards interdisciplinary care to create challenges for staff in developing positive relationships [ 53 ]. The importance of positive relationships, respect of roles and recognition of value between co-workers demonstrated in our review highlights the value of further work to enhance interprofessional collaboration.

Limitations

Whilst this review synthesised the available literature, the variation in measurement instruments and sample sizes made comparison difficult. Since not all papers reported the reliability or validity of the instruments they used it is possible that these instruments had issues in their validity. The data presented, however, represents the best available evidence to address the research question.

A further limitation is the variation between PHC settings and international PHC systems that makes comparison difficult. Whilst this review has included all papers written about PHC nurses internationally, local variations mean that care needs to be taken when generalising findings to other contexts, even within PHC.

This review has identified some key factors that impact on both job satisfaction and career intentions amongst PHC nurses. The importance of the work environment and workplace relationships highlights the need to implement strategies that enhance modifiable workplace factors. The numbers of nurses across studies indicating an intention to leave is a significant concern at a time when we need to build the PHC workforce internationally. Findings from this review highlight the need for action by managers, educators, employers and policy makers to enhance support for nurses in PHC.

Implications for practice and research

There is urgent need to build capacity within the PHC nursing workforce internationally to meet service demands. This review has highlighted a number of issues around job satisfaction and career intention that impact on the retention of nurses in PHC. Exploring strategies to address the modifiable antecedents to nurse job dissatisfaction has the potential to improve retention. Maintaining happy and skilled nurses in the workforce has the potential to build workforce capacity and enhance patient outcomes.

This review has demonstrated that gaps remain in our knowledge around job satisfaction and career intention among PHC registered nurses. Further well-designed longitudinal research is required to explore the trajectory of careers in PHC. Additionally, mixed methods approaches are likely required to explore not only quantitative job satisfaction, but also to reveal how the aspects of satisfaction impact on PHC nurses.

Abbreviations

Primary Health Care

Buchan J, Twigg D, Dussault G, Duffield C, Stone PW. Policies to sustain the nursing workforce: an international perspective. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62(2):162–70.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Delobelle P, Rawlinson JL, Ntuli S, Malatsi I, Decock R, Depoorter AM. Job satisfaction and turnover intent of primary healthcare nurses in rural South Africa: a questionnaire survey. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(2):371–83.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

AbuAlRub R, El-Jardali F, Jamal D, Al-Rub NA. Exploring the relationship between work environment, job satisfaction, and intent to stay of Jordanian nurses in underserved areas. ANR. 2016;31:19–23.

PubMed Google Scholar

Spence Laschinger HK, Zhu J, Read E. New nurses’ perceptions of professional practice behaviours, quality of care, job satisfaction and career retention. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(5):656–65.

Lu H, Barriball KL, Zhang X, While AE. Job satisfaction among hospital nurses revisited: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(8):1017–38.

Hayes B, Bonner A, Pryor J. Factors contributing to nurse job satisfaction in the acute hospital setting: a review of recent literature. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(7):804–14.

Atefi N, Abdullah K, Wong L, Mazlom R. Factors influencing registered nurses perception of their overall job satisfaction: a qualitative study. Int Nurs Rev. 2014;61(3):352–60.

Khamisa N, Oldenburg B, Peltzer K, Ilic D. Work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(1):652–66.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Takase M, Yamashita N, Oba K. Nurses' leaving intentions: antecedents and mediating factors. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(3):295–306.

Hayes LJ, O’Brien-Pallas L, Duffield C, Shamian J, Buchan J, Hughes F, Laschinger HKS, North N. Nurse turnover: a literature review – an update. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(7):887–905.

Kim J-K, Kim M-J. A review of research on hospital nurses' turnover intention. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2011;17(4):538–50.

Article Google Scholar

Liu Y. Job satisfaction in nursing: a concept analysis study job satisfaction in nursing. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63(1):84–91.

Chan ZC, Tam WS, Lung MK, Wong WY, Chau CW. A systematic literature review of nurse shortage and the intention to leave. J Nurs Manag. 2013;21(4):605–13.

Cicolini G, Comparcini D, Simonetti V. Workplace empowerment and nurses' job satisfaction: a systematic literature review. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22(7):855–71.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Australian Nursing and Midwifery Workforce Data and additional information. Canberra, Australia; 2014.

Google Scholar

Freund T, Everett C, Griffiths P, Hudon C, Naccarella L, Laurant M. Skill mix, roles and remuneration in the primary care workforce: who are the healthcare professionals in the primary care teams across the world? Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(3):727–43.

Halcomb E, Ashley C, James S, Smythe E. Employment conditions of Australian PHC nurses. Collegian. 2018;25(1):65–71.

Halcomb EJ, Ashley C. Australian primary health care nurses most and least satisfying aspects of work. J Clin Nurs. 2017;36(3–4):535–45.

Lorenz VR, De Brito Guirardello E. The environment of professional practice and burnout in nurses in primary healthcare. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2014;22(6):926–33.

Poghosyan L, Liu J, Shang J, D’Aunno T. Practice environments and job satisfaction and turnover intentions of nurse practitioners: implications for primary care workforce capacity. Health Care Manag Rev. 2015;

Health Workforce Australia: Health Workforce 2025 - Doctors, Nurses and Midwives. Adelaide; 2012.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53.

Desborough J, Parker R, Forrest L. Nurse satisfaction with working in a nurse led primary care walk-in Centre: an Australian experience. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2013;31(1):11–9.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–41.

Center for Evidence Based Management. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cross-Sectional Study. 2014. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Critical-Appraisal-Questions-for-a-Cross-Sectional-Study-july-2014.pdf . Accessed May 22 2017.

Armstrong-Stassen M, Cameron SJ. Concerns, satisfaction, and retention of Canadian community health nurses. J Community Health Nurs. 2005;22(4):181–94.

Flynn L, Deatrick JA. Home care Nurses' descriptions of important agency attributes. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35(4):385–90.

Junious DL, Johnson RJ, Peters RJ Jr, Markham CM, Kelder SH, Yacoubian GS Jr. A study of school nurse job satisfaction. Journal of School Nursing (Allen Press Publishing Services Inc). 2004;20(2):88–93.

Storey C, Cheater F, Ford J, Leese B. Retaining older nurses in primary care and the community. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(7):1400–11.

Stuart EH, Jarvis A, Daniel K. A ward without walls? District nurses' perceptions of their workload management priorities and job satisfaction. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(22):3012–20.

Tourangeau A, Patterson E, Rowe A, Saari M, Thomson H, MacDonald G, Cranley L, Squires M. Factors influencing home care nurse intention to remain employed. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22(8):1015–26.

Royer L. Empowerment and commitment perceptions of community/public health nurses and their tenure intention. Public Health Nurs. 2011;28(6):523–32.

Best MF, Thurston NE. Canadian public health nurses' job satisfaction. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23(3):250–5.

Campbell SL, Fowles ER, Weber BJ. Organizational structure and job satisfaction in public health nursing. Public Health Nurs. 2004;21(6):564–71.

Cameron S, Armstrong-Stassen M, Bergeron S, Out J. Recruitment and retention of nurses: challenges facing hospital and community employers. Can J Nurs Leadersh. 2004;17(3):79–92.

Cole S, Ouzts K, Stepans MB. Job satisfaction in rural public health nurses. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(4):E1–6.

Curtis EA, Glacken M. Job satisfaction among public health nurses: a national survey. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22(5):653–63.

Doran D, Pickard J, Harris J, Coyte PC, MacRae AR, Laschinger HS, Darlington G, Carryer J. The relationship between managed competition in home care nursing services and nurse outcomes. Can J Nurs Res. 2007;39(3):151–65.

Graham KR, Davies BL, Woodend AK, Simpson J, Mantha SL. Impacting Canadian public health nurses' job satisfaction. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(6):427–31.

Tullai-McGuinness S. Home healthcare practice environment: predictors of RN satisfaction. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(3):252–60.

O'Donnell C, Jabareen H, Watt G. Practice nurses' workload, career intentions and the impact of professional isolation: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Nurs. 2010;9(1):2.

Almalki MJ, Fitzgerald G, Clark M. The relationship between quality of work life and turnover intention of primary health care nurses in Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:314.

Betkus MH, MacLeod MLP. Retaining public health nurses in rural British Columbia: the influence of job and community satisfaction. Can J Public Health. 2004;95(1):54–8.

Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, Van den Heede K, Sermeus W. Nurses' reports of working conditions and hospital quality of care in 12 countries in Europe. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(2):143–53.

Laschinger HKS. Job and career satisfaction and turnover intentions of newly graduated nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20(4):472–84.

Nantsupawat A, Kunaviktikul W, Nantsupawat R, Wichaikhum OA, Thienthong H, Poghosyan L. Effects of nurse work environment on job dissatisfaction, burnout, intention to leave. Int Nurs Rev. 2017;64(1):91–8.

Al-Dossary R, Vail J, Macfarlane F. Job satisfaction of nurses in a Saudi Arabian university teaching hospital: a cross-sectional study. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(3):424–30.

Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM, Griffiths R, Daly J. Cardiovascular disease management: time to advance the practice nurse role? Aust Health Rev. 2008;32(1):44–55.

Lartey S, Cummings G, Profetto-McGrath J. Interventions that promote retention of experienced registered nurses in health care settings: a systematic review. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22(8):1027–41.

Galletta M, Portoghese I, Battistelli A, Leiter MP. The roles of unit leadership and nurse–physician collaboration on nursing turnover intention. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(8):1771–84.

McInnes S, Peters K, Bonney A, Halcomb E. An integrative review of facilitators and barriers influencing collaboration and teamwork between general practitioners and nurses working in general practice. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(9):1973–85.

McInnes S, Peters K, Bonney A, Halcomb E. The influence of funding models on collaboration in Australian general practice. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23(1):31–6.

Williams A, Sibbald B. Changing roles and identities in primary health care: exploring a culture of uncertainty. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(3):737–45.

Download references

No funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Nursing, University of Wollongong, Northfields Ave, Wollongong, NSW, 2522, Australia

Elizabeth Halcomb, Elizabeth Smyth & Susan McInnes

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

EH conceived the study, conducted the initial search and participated in the data analysis and drafting of the paper. ES confirmed the initial search and participated in the data analysis and drafting of the paper. SM participated in the data analysis and drafting of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elizabeth Halcomb .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

Professor Elizabeth Halcomb is an Associate Editor of BMC Family Practice. Nil other competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Halcomb, E., Smyth, E. & McInnes, S. Job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses in primary health care: an integrative review. BMC Fam Pract 19 , 136 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0819-1

Download citation

Received : 08 February 2018

Accepted : 12 July 2018

Published : 07 August 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0819-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Primary health care

- Job satisfaction

- Career intention

BMC Primary Care

ISSN: 2731-4553

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Fam Pract

Job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses in primary health care: an integrative review

Elizabeth halcomb.

School of Nursing, University of Wollongong, Northfields Ave, Wollongong, NSW 2522 Australia

Elizabeth Smyth

Susan mcinnes, associated data.

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

There has been a significant growth of the international primary health care (PHC) nursing workforce in recent decades in response to health system reform. However, there has been limited attention paid to strategic workforce growth and evaluation of workforce issues in this setting. Understanding issues like job satisfaction and career intentions are essential to building capacity and skill mix within the workforce. This review sought to explore the literature around job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses working in PHC.

An integrative review was conducted. Electronic databases including: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science, and reference lists of journal publications were searched for peer-reviewed literature published between 2000 and 2016 related to registered nurse job satisfaction and career intentions. Study quality was appraised, before thematic analysis was undertaken to synthesise the findings.

Twenty papers were included in this review. Levels of job satisfaction reported were variable between studies. A range of factors impacted on job satisfaction. Whilst there was agreement on the impact of some factors, there was a lack of consistency between studies on other factors. Four of the six studies which reported career intentions identified that nearly half of their participants intended to leave their current position.

This review identifies gaps in our understanding of job satisfaction and career intentions in PHC nurses. With the growth of the PHC nursing workforce internationally, there is a need for robust, longitudinal workforce research to ensure that employment in this setting is satisfying and that skilled nurses are retained.

The recruitment and retention of nurses is problematic worldwide. There is a maldistribution of human resources for health, a shortage in the overall number of qualified nurses and an aging nursing workforce [ 1 ]. Job satisfaction has been cited as an important factor contributing to the turnover of nurses and as an antecedent to nursing retention [ 2 – 4 ]. Therefore, understanding factors that impact on job satisfaction is important to inform recruitment and retention strategies.

The concept of job satisfaction is multifaceted and complex. Job satisfaction has been the focus of much research around organisational behaviour. Lu, et al. [ 5 ] define job satisfaction as not only how an individual feels about their job but also the nature of the job and the individuals’ expectation of what their job should provide. To this end, job satisfaction is comprised of various components, including; job conditions, communication, the nature of the work, organisational policies and procedures, remuneration and conditions, promotion / advancement opportunities, recognition / appreciation, security and supervision / relationships [ 5 ]. Whilst levels of job satisfaction vary, several common factors emerge across studies [ 6 , 7 ]. These include working conditions and the organisational environment, levels of stress, role conflict and ambiguity, role perceptions and content and organisational and professional commitment [ 5 – 8 ]. Given these factors it becomes clear that research about job satisfaction cannot be undertaken across the nursing profession as a whole, but rather needs to consider various settings and organisational environments to understand the issues facing different nursing groups.

Career intentions can be described as the intention to leave ones’ job voluntarily [ 9 ]. This process may start with a psychological response to negative situations in the workplace or undesirable aspects of the job. Subsequently, a cognitive decision is made to leave the position and withdrawal behaviours occur as the person moves out of the workplace [ 10 ]. Like job satisfaction, a number of common determinants for career intention have been identified. These include organisational factors, management style, workload and stress, role perceptions, empowerment, remuneration and employment conditions and opportunities for advancement [ 10 ]. In several studies, job satisfaction has been shown to impact on career intentions [ 11 , 12 ].

Despite the common themes in this workforce literature, much of the research around job satisfaction and career intentions reported to date has focussed on acute care nurses [ 2 , 5 , 6 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 ]. Given the impact of organisational factors, roles and employment conditions it is important to consider different groups of nurses, such as those employed in PHC, who are employed in settings unlike those of their acute care colleagues. PHC nurses practice in a range of settings, including general practices, schools, refugee health services, correctional settings, non-government organisations and community health centres [ 15 ]. As such, their employment conditions and work environments are unlike those of acute care nurses who are employed by large health providers or government funded health services (17). The small business nature of primary care in many countries and the predominance of charities and non-government health providers makes employment in the PHC setting unique [ 16 – 18 ]. Lorenz and De Brito Guirardello [ 19 ] describe the PHC work environment as “not always favourable to the professional practice of nurses”(p. 927), citing lack of equipment, inappropriate physical environment and occupational risks as key contributors to dissatisfaction. Additionally, there are significant difference between the roles, responsibilities and work environments of acute and PHC nurses [ 20 ]. These differences and the impact of such factors on job satisfaction and career intentions mean that acute care nursing workforce research cannot be simply generalised to the PHC setting. With the growth in the PHC nursing workforce and the need for a strong nursing workforce in this setting it is timely to explore the job satisfaction and career intentions of PHC nurses. Therefore, this review sought to critically synthesise the literature around the job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses working in PHC.

The underlying research questions are:

- What was known about the main outcomes of studies regarding PHC registered nurses job satisfaction?

- What was known about the career intentions of PHC registered nurses?

Registered nurses are the focus of the review as they are the largest nursing workforce in PHC [ 21 ].

This integrative literature review is informed by Whittemore and Knafls [ 22 ] framework. It provides a thorough examination of the existing literature following the five stages of review: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation [ 22 ].

Search strategy

A systematic search strategy was designed to guide the search of electronic databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science. Key search terms included; nurs*, primary health care, community care and job satisfaction or career intention. The search was confined to English language peer reviewed papers of original research. Given the significant changes in PHC systems internationally, only papers published between January 2000 and 2016 were considered. The reference lists of publications were also reviewed to identify further literature.

Inclusion criteria

Table 1 details the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Papers were excluded if they focussed on a particular nursing specialty (e.g. community mental health nurses) or were based in residential care settings (e.g. nursing homes), as the issues with this workforce are somewhat different to other PHC settings. Studies that focussed on nurse practitioners and/or advanced practice nurses (e.g. [ 23 ]), or specifically on nurse managers were excluded as these nurses may have different perceptions and experiences to registered nurses. Remoteness itself was not considered to constitute PHC nursing, therefore, papers focussed on rural or remote nurses without being specifically PHC focussed were excluded. Research articles were also excluded if the findings did not isolate PHC nurses from acute care nurses or other health professionals.

Inclusion / Exclusion Criteria

Study selection

After removal of duplicates, 477 citations were yielded from the search. These citations were exported to Endnote X8™ for review of their titles, followed by closer evaluation of the abstract. This process identified that 346 papers did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 131 papers where the full-text was retrieved. Of these papers, 111 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and so were excluded. This left 20 papers for inclusion in the review. (Fig. 1 ).

Process of paper selection – Prisma Flow diagram [ 24 ]

Appraisal of methodological quality

Determining the methodological quality of the included studies was difficult due to the broad sampling frame and various research designs [ 22 ]. As identified by Whittemore and Knafl [ 22 ], there is no gold standard for evaluating quality in research reviews. In this review we conducted quality appraisal using the tool provided by the Center for Evidence Based Management [ 25 ]. The major areas of concern were around the quality of reporting of the instrument development and validity / reliability measures in some papers [ 26 – 31 ]. Given the relatively small number of included papers and the minor nature of the limitations identified none of the studies were excluded based on their methodological quality.

Data abstraction and synthesis

Once the included papers were identified all data was abstracted into a summary table. The main characteristics that were extracted included;

- Study design

- Main outcomes related to job satisfaction or career intention

The nature of the included papers, in terms of the heterogeneity of the measures used, meant that thematic analysis was the most appropriate technique for aggregating the findings. Therefore, data is presented in a narrative form around the key themes that emerged from the literature.

Of the 20 included papers (Table 2 ), 15 (75%) described quantitative studies, 4 (20%) papers described qualitative projects, and the remaining paper (5%) employed a mixed-method approach. Most of the included papers reported research undertaken in Canada ( n = 8, 40%), with other studies coming out of the United Kingdom ( n = 4, 20%), the United States of America ( n = 5, 25%), one paper each from Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Brazil.

Summary table

The sample sizes of included studies varied from 31 [ 30 ] to 1044 participants [ 26 ]. Participants spanned the scope of PHC and included community nurses, primary health nurses, general practice nurses, school nurses, and district nurses. In some studies the data from various primary care nursing groups was reported in an aggregated form [ 32 ], whilst in other papers there was an attempt to tease out the differences between groups [ 26 , 29 ].

Eleven (55%) papers focussed on job satisfaction only [ 27 , 28 , 30 , 33 – 40 ], and three (15%) papers reported only data on career intention or turnover [ 31 , 32 , 41 ]. A further six (30%) papers combined measures of job satisfaction and career intention within the same study [ 2 , 19 , 26 , 29 , 42 , 43 ].

The key features and predominant findings of papers are summarised in Table Table2. 2 . Five overarching themes emerged, namely; levels of job satisfaction, factors that enhanced job satisfaction, factors that reduced levels of job satisfaction, career intentions, and, factors that impacted on career intentions.

Levels of job satisfaction

The variation in measurement of job satisfaction across studies and the differences in respondent characteristics makes comparison difficult. Most tools measured job satisfaction quantitatively using a Likert scale (agree to disagree) [ 2 , 19 , 26 , 37 – 39 ], whilst one study used qualitative data collected from focus groups and interviews [ 28 ]. Studies measured different aspects of job satisfaction including; overall satisfaction (enjoyment, pride), specific aspects of the job (pay, rewards, resources, task requirements, work conditions, training, quality of care, time) and supervision (authority, autonomy, feedback, appreciation, organisational policies, interaction).

In some studies just over half of the respondents were reported to be satisfied with their job [ 19 , 39 ], whilst in other studies a greater majority indicated that they were satisfied [ 28 ]. A small number of studies reported moderate [ 2 , 38 ] to low levels of satisfaction [ 37 , 42 ]. Those studies which reported lower levels of satisfaction used more items to measure satisfaction (42 items and 80 items respectively) [ 37 , 42 ], compared to studies reporting high levels of satisfaction which used only 4 items [ 19 , 39 ].

Factors influencing job satisfaction

The ten studies which explored the relationship between job satisfaction and demographics / professional variables demonstrated significant variation [ 2 , 19 , 29 , 34 , 36 – 40 , 43 ]. Whilst two studies found that age had no significant impact on job satisfaction [ 2 , 43 ], three others demonstrated that older nurses were more satisfied than their younger colleagues [ 29 , 37 , 38 ]. Similarly, there were variable findings related to the impact of education, with three papers finding no relationship with job satisfaction or inconclusive findings [ 2 , 36 , 37 ], and two papers demonstrating that nurses with higher educational qualifications had reported higher work satisfaction [ 34 , 40 ]. In contrast, Delobelle et al. [ 2 ] found that Nursing Assistants and Enrolled Nurses were more satisfied than Registered Nurses.

Curtis and Glacken [ 37 ] reported that those employed for over 10 years had a significantly higher level of job satisfaction than other nurses. However, other studies reported an inverse relationship between years worked in PHC and satisfaction [ 40 ] and no significant differences between satisfaction and years of nursing [ 2 ].

Other factors that positively contributed to satisfaction included control over clinical practice and decision-making [ 19 , 34 , 39 , 40 ], community satisfaction [ 43 ], organisational support [ 19 ], remuneration [ 38 ], and workload [ 39 ].

There was significant agreement between studies in terms of the factors that contributed positively to job satisfaction. These included the professional role, respect and recognition from clients and managers, workplace relationships, autonomy, access to resources and the flexibility of the role [ 2 , 27 – 31 , 33 , 34 , 37 , 43 ].

Factors negatively impacting job satisfaction

There was a high level of agreement amongst included studies about factors that negatively impacted respondents’ levels of satisfaction. Seven studies identified concerns about adequate remuneration [ 2 , 28 , 29 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 43 ]. When comparing hospital and community nurses, Campbell, et al. [ 34 ] identified that hospital nurses were significantly more likely than community nurses to be satisfied with their pay.

Another key factor identified in several studies related to the time pressures and high administrative workloads that impact on patient care [ 2 , 26 , 30 , 33 , 37 ]. Other factors identified to negatively impact job satisfaction included; a lack of recognition [ 2 , 28 , 33 , 34 ], poor role clarity [ 30 , 34 , 37 ] and poor organisational communication [ 29 , 34 ].

Career intentions

The included studies present an important picture around career intentions. However, caution needs to be applied in the interpretation of these data, as most studies comprise of an ageing workforce who will naturally retire in the near future. Six studies sought to explore the factors impacting on retention [ 2 , 32 , 34 , 41 – 43 ] The highest reported career intentions was reported by Delobelle, et al. [ 2 ] with half of all nurse participants ( n = 69; 51.1%) considering leaving PHC in the next 2 years. Both Betkus and MacLeod [ 43 ] and Almalki, et al. [ 42 ] also reported that nearly half (48 and 40%) intended to leave their current PHC job in the next year. Royer [ 32 ] similarly identified that some 46% of participants aged 35–45 years were considering leaving, and almost 40% of those aged 56–65 were thinking about leaving. The remaining two studies reported that few participants intended to leave their current position [ 34 , 41 ].

The findings of the three studies which explored job satisfaction and quality of worklife [ 2 , 42 , 43 ], lacked consistency. Almalki, et al. [ 42 ] demonstrated that quality of worklife was significantly related to turnover intent ( p < 0.001), however, this only explained 26% of the variance and was not included in the final model. Whilst Betkus and MacLeod [ 43 ] reported no correlation between job satisfaction and retention, Delobelle, et al. [ 2 ] found that turnover intent was significantly explained by job satisfaction, age and education ( p < 0.001). Other factors that were identified as having an impact on career intentions included gender [ 42 ], work environment [ 42 ], remuneration [ 42 ], education [ 2 , 41 , 42 ], satisfaction with supervision [ 2 ], feelings of isolation [ 41 ], length of time in position / years of experience [ 32 , 42 ].

This review provides the first synthesis of the literature around job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses working in PHC. Given the differences in organisational context, employment conditions and practice environment that likely impact job satisfaction and career intention [ 17 – 19 ] it is important that this group are explored beyond the context of the broader nursing workforce. Considering the imperatives to grow the workforce in PHC settings, to meet community demand, understanding this literature is important to inform both practice and policy. Dissatisfaction with nursing employment is reported in the broader nursing workforce literature. In their survey of 33,659 medical–surgical nurses across 12 European countries, Aiken, et al. [ 44 ] concluded that more than one in five nurses were dissatisfied with their employment. The variation in job satisfaction identified in this review highlights the need for further large well-designed longitudinal investigations of the PHC nurse workforce to monitor workforce issues, such as satisfaction and career intentions, over time. Given the links between nurse satisfaction and both retention and patient outcomes [ 44 ], this issue should be prioritised.

Our review demonstrated agreement between studies in terms of the positive impact of a professional role, respect, recognition, workplace relationships and autonomy upon job satisfaction. This is consistent with the acute care nursing literature where modifiable factors within the workplace have been demonstrated to influence both job and career satisfaction [ 45 ]. In their study, Nantsupawat, et al. [ 46 ] demonstrated that job dissatisfaction and intention to leave were significantly lower in nurses who worked in a better work environment. Similarly, in their systematic review, Cicolini, et al. [ 14 ] found a significant link between nurses empowerment and satisfaction. The significant role of such modifiable factors highlights an opportunity for managers, employers and policy makers to implement strategies which can improve the workplace and, subsequently, enhance satisfaction.

A key finding of this review was the negative impact of poor remuneration on job satisfaction. Whilst concerns about pay have been previously identified in the acute sector [ 44 , 47 ], the challenge of lower rates of pay in PHC compared to the acute sector has long been reported [ 17 , 48 ]. This review adds to the evidence-base around the impact of this disparity on the PHC nursing workforce and highlights the significant implications of not addressing this issue.

Our review also revealed that in many studies large numbers of nurses were intending to leave PHC employment in the near future [ 2 , 42 , 43 ]. This clearly has significant implications for the workforce and service delivery. However, measures of the factors affecting career intentions were variable across included studies as were findings. The difficulties in synthesising such disparate data have been previously identified in the acute care literature [ 13 ]. Despite this, there were clear similarities between our review and the broader literature around nurse turnover and intention to leave. In their systematic review of nurses intention to leave their employment, Chan, et al. [ 13 ] identified that intention to leave was impacted by a complex combination of organisational and individual factors. Organisational factors included the work environment, culture, commitment, work demands and social support. In contrast, individual factors related to job satisfaction, burnout and demographic factors. The complex interplay of multiple factors that underlie retention is probably the reason that retention is the highest when interventions such as mentoring and in-depth orientations are used to support staff [ 49 ].

In their study of acute care nurses Galletta, et al. [ 50 ] conclude that the quality of relationships among staff is an important factor in nurses’ decisions to leave. Interprofessional relationships in PHC have long been identified as presenting unique challenges [ 48 , 51 ]. The complex environment of PHC, whereby services are funded by small businesses or non-government agencies [ 52 ], combines with the relatively rapid shift towards interdisciplinary care to create challenges for staff in developing positive relationships [ 53 ]. The importance of positive relationships, respect of roles and recognition of value between co-workers demonstrated in our review highlights the value of further work to enhance interprofessional collaboration.

Limitations

Whilst this review synthesised the available literature, the variation in measurement instruments and sample sizes made comparison difficult. Since not all papers reported the reliability or validity of the instruments they used it is possible that these instruments had issues in their validity. The data presented, however, represents the best available evidence to address the research question.

A further limitation is the variation between PHC settings and international PHC systems that makes comparison difficult. Whilst this review has included all papers written about PHC nurses internationally, local variations mean that care needs to be taken when generalising findings to other contexts, even within PHC.

This review has identified some key factors that impact on both job satisfaction and career intentions amongst PHC nurses. The importance of the work environment and workplace relationships highlights the need to implement strategies that enhance modifiable workplace factors. The numbers of nurses across studies indicating an intention to leave is a significant concern at a time when we need to build the PHC workforce internationally. Findings from this review highlight the need for action by managers, educators, employers and policy makers to enhance support for nurses in PHC.

Implications for practice and research

There is urgent need to build capacity within the PHC nursing workforce internationally to meet service demands. This review has highlighted a number of issues around job satisfaction and career intention that impact on the retention of nurses in PHC. Exploring strategies to address the modifiable antecedents to nurse job dissatisfaction has the potential to improve retention. Maintaining happy and skilled nurses in the workforce has the potential to build workforce capacity and enhance patient outcomes.

This review has demonstrated that gaps remain in our knowledge around job satisfaction and career intention among PHC registered nurses. Further well-designed longitudinal research is required to explore the trajectory of careers in PHC. Additionally, mixed methods approaches are likely required to explore not only quantitative job satisfaction, but also to reveal how the aspects of satisfaction impact on PHC nurses.

No funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Abbreviation, authors’ contributions.

EH conceived the study, conducted the initial search and participated in the data analysis and drafting of the paper. ES confirmed the initial search and participated in the data analysis and drafting of the paper. SM participated in the data analysis and drafting of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

Professor Elizabeth Halcomb is an Associate Editor of BMC Family Practice. Nil other competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Halcomb, Phone: +61 2 4221 3784, Email: ua.ude.wou@bmoclahe .

Elizabeth Smyth, Email: [email protected] .

Susan McInnes, Email: ua.ude.wou@sennicms .

- Open access

- Published: 07 September 2023

Nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction: the role of technology integration, self-efficacy, social support, and prior experience

- Mohammed Hamdan Alshammari 1 &

- Atallah Alenezi 2

BMC Nursing volume 22 , Article number: 308 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5569 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

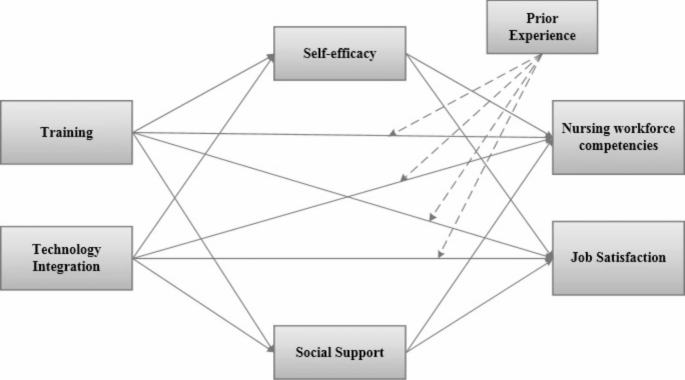

The nursing profession has significant importance in delivering high-quality healthcare services. Nursing practitioners who have essential competencies and who are satisfied with their job are vital in achieving optimum patient outcomes. Understanding the effects of technology integration on nurse workforce competencies and job satisfaction is crucial due to the fast progress of technology in healthcare settings. Furthermore, many elements, including self-efficacy, social support, and prior experience have been recognized as possible mediators or moderators within this association. The primary objective of this quantitative research was to examine the influence of nursing education and the integration of technology on the competencies and job satisfaction of nursing professionals. Additionally, this study aimed to explore the potential mediating and moderating effects of self-efficacy and social support in this relationship.

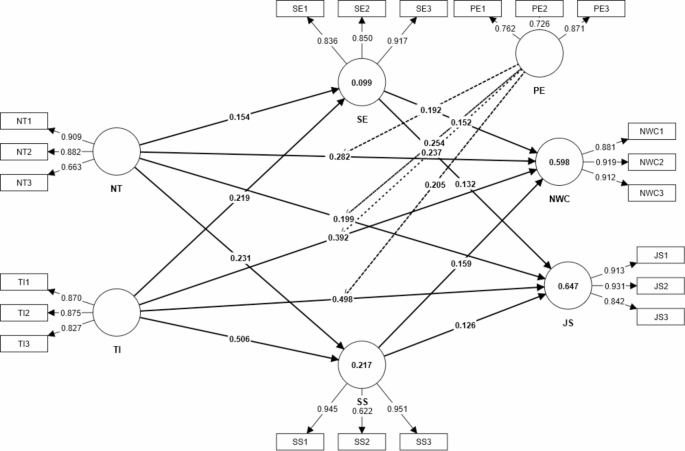

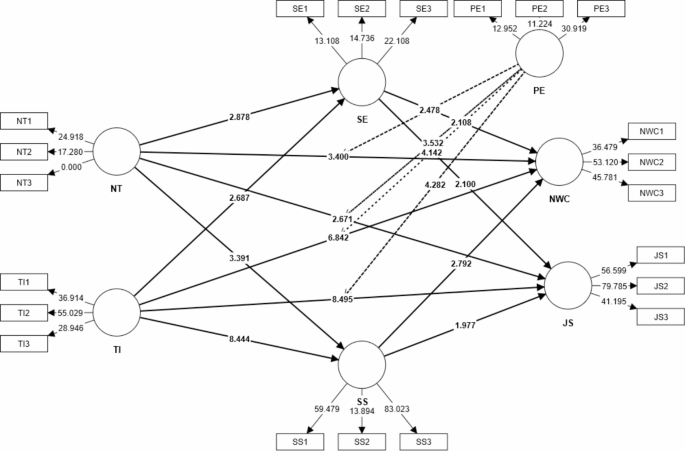

This cross-sectional, quantitative study employed an online survey questionnaire with standardized scales to measure nursing workforce competencies, job satisfaction, self-efficacy, social support, and prior experience. It was completed by 210 registered nurses from various healthcare settings in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Data were analyzed by descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation analysis, multiple regression analysis, and structural equation modeling performed with SPSS 23 and SmartPLS 3.0 software.

The study’s findings revealed that nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction were significantly predicted by nursing training and technology integration. The relationship between nursing training and technology integration, as well as nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction, was partially mediated by self-efficacy and social support. Furthermore, prior experience moderated the relationship between nursing education and technological integration, nursing workforce competencies, and job satisfaction.

Conclusions

The study’s findings suggest that nursing training and technology integration can improve nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction and that self-efficacy and social support play an important role in mediating this relationship. Furthermore, prior experience can have an impact on the efficacy of nursing training and technology integration programs for developing nursing workforce competencies. The study has several practical implications for nursing education, training, and professional development programs, as well as strategies used by healthcare organizations to improve nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction. To maximize their impact on nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction, this study recommends that nursing training and technology integration programs focus on enhancing self-efficacy and social support. Furthermore, the study emphasizes the significance of prior experience when designing and implementing nursing training and technology integration programs.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The nursing profession is an important part of the healthcare industry and plays an important part in ensuring the health and well-being of patients [ 1 ]. The process of incorporating technological tools, resources, and systems into existing operations, practices, and environments is known as technology integration [ 2 ]. It involves integrating technology with established methods and strategies to attain particular objectives and results. The purpose of technology integration is to maximize the potential of technology to enhance processes, collaboration, communication, and overall performance [ 3 ]. The incorporation of technology into nursing education and practice in recent years has had a significant impact on the nursing workforce’s overall competency levels as well as their level of job satisfaction. The combination of nursing training and technological advancements has been found to improve the level of job satisfaction among nurses, which in turn results in better healthcare outcomes for patients [ 4 ].

The nursing workforce’s competencies and their level of satisfaction in their jobs are both essential components of nursing practice necessary for delivering high-quality care to patients [ 5 ]. Job satisfaction refers to the level of contentment and fulfillment that is experienced by nurses in their jobs, while nursing workforce competencies refer to the knowledge, skills, and abilities required for nurses to effectively perform their duties [ 6 ]. Nursing workforce competencies are important because they ensure that nurses have the knowledge and abilities necessary to provide care that is safe, effective, and centered on the patient. It is absolutely necessary to provide competent nursing care in order to reduce healthcare costs, improve patient satisfaction, and prevent unfavorable patient outcomes. Additionally, competent nursing care makes a contribution to the overall quality of the delivery of healthcare as well as the safety of the patient [ 7 ].

The retention of nurses is essential to the upkeep of a steady nursing workforce and job satisfaction is one factor that contributes to their motivation to stay in their positions. Researchers have found a correlation between high levels of job satisfaction and low rates of employee turnover, improved patient outcomes, and increased productivity [ 8 ]. Nurses who report higher levels of job satisfaction are also more likely to participate in activities that contribute to their ongoing learning and professional development, which in turn increases their level of expertise and efficiency as providers of healthcare [ 4 ].

Despite the fact that a number of studies have investigated the effect that nursing training and the incorporation of technology has had on the nursing workforce’s competencies and job satisfaction [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], there is a deficiency in the body of research concerning the factors that influence the success of these relations. To be more specific, there is a dearth of research on the ways in which individual differences, such as personality traits, moderate the relationship between nursing training and technology integration and nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction [ 12 ].

The moderating role of prior experience in the effectiveness of nursing training and technology integration interventions highlights the necessity to consider individual differences when designing and implementing these interventions [ 13 ]. However, additional research is required on other potential moderators, such as personality traits, that may have an impact on the efficacy of nursing education and training programs. It is essential to gain an understanding of the moderating factors that have an effect on the efficacy of nursing education and training programs in order to design nursing interventions that are both more effective and better tailored to meet the varied requirements of the nursing workforce [ 12 ] In addition, nursing educators and practitioners can gain a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the interventions’ effects on nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction by locating potential mediators such as self-efficacy and social support. Self-efficacy and social support were chosen as mediating variables for “individual differences” because they play important roles in shaping individual behavior, attitudes, and results [ 14 , 15 ].

Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in their own ability to complete activities and accomplish desired results. It determines how people approach problems, persevere in the face of adversity, and recover from disappointments. Higher degrees of self-efficacy promotes motivation, confidence, and goal-directed behavior, whereas lower levels might hamper performance and personal growth [ 16 ]. Social support, on the other hand, refers to the assistance, encouragement, and resources supplied by people inside an individual’s social network [ 17 ]. It could come from family, friends, coworkers, or managers. Social support is critical in relieving stress, increasing well-being, and facilitating adaptation to new situations or obstacles. Strong social support networks give emotional support, guidance, and practical aid, positively influencing an individual’s beliefs, behaviors, and overall functioning [ 18 ].

The objectives of this study were:

To investigate the impact of nursing training and technology integration on nursing workforce competencies.

To explore the relationship between nursing training and technology integration and job satisfaction among the nursing workforce.

To examine the mediating role of self-efficacy and social support in the relationship between nursing training and technology integration and nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction.

To determine the moderating role of prior experience in the effectiveness of nursing training and technology integration interventions on nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction.

These objectives aimed to fill a gap in the existing literature and provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of nursing training and technology integration on nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction, as well as the mediating and moderating factors that may influence the efficacy of these interventions. In addition, these objectives sought to identify the factors that may influence the effectiveness of these interventions. The conclusions from this study have the potential to inform nursing educators and practitioners on how to design and implement more effective training programs that cater to the diverse needs of the nursing workforce and better prepare them for the future of healthcare.

This research makes a significant contribution to the existing body of literature on nursing education and training by delivering an in-depth understanding of the influence that nursing training and the integration of technology have had on the competencies of nursing workforces and on job satisfaction. This study provides insight into how nursing educators and practitioners can design and implement more effective training programs that cater to the diverse needs of the nursing workforce. This was accomplished by exploring the mediating and moderating factors that influence the effectiveness of these interventions.

Literature review

Training and nursing workforce competence.