Cool Green Science

Stories of The Nature Conservancy

The Yeti: A Story of Scientific Misunderstanding

Science has laid to rest any "evidence" of the Yeti, but perhaps it has always overlooked the myth.

Share this article

Share this:.

The Yeti is a cryptozoological phenomenon popularized in the early 20 th century by British mountain explorers in the Himalayas.

Those who claim to have seen it report a modest-sized, two-legged, hairy mountain creature with disproportionately large feet.

A recent scientific study has shown, once and for all, that physical evidence (fur, bone and skin) purported to be from the Yeti are instead from bears, based on genetic analysis.

Bear species that fall within the “range” of the Yeti include Asiatic black bear and two subspecies of brown bears, the Tibetan and Himalayan.

The reports of Yeti sightings began as soon as Western explorers made headway into the Himalayas. The explorers gathered first-hand accounts from locals and translated these observations into prosaic descriptions of the creature’s shape, fur color and gait.

With this, the Western world began to believe that the Yeti could be real, and Yeti-finding expeditions were dispatched.

Over the decades, Yeti encounters continued to accumulate, though physical evidence has always been elusive.

Nonetheless, the existence of the Yeti could never be ruled out. The Himalayan wilderness seemed vast and inaccessible enough for the existence of an undiscovered animal to be plausible.

In his book The Snow Leopard , famed nature writer Peter Matthiessen writes about a 1973 Himalayan expedition to study the blue sheep. Throughout his narrative, the author seems just as primed to spy a Yeti as he is a snow leopard. And we read that his companion, legendary wildlife biologist George Schaller, also refuses to rule out the Yeti’s existence.

Of all mythical beasts, the Yeti has received the most attention in actual peer-reviewed scientific journals. It has been the subject of articles in such top-tier science and conservation publications as Oryx , Proceedings of the Royal Society B and Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution .

The Oryx article, published in 1973, summarized the state of knowledge regarding the Yeti’s existence and proposed that it could be an undiscovered human-like hominid that occupied dense unexplored forest on the lower slopes of the mountains.

All subsequent articles have focused on genetic analysis of purported physical Yeti specimens of hair, bone and skin.

Two recent studies, both published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B , may finally mark an end to this attention from the scientific community. A 2014 paper concluded that all genetic evidence analyzed from purported Yeti specimens actually came from a wide range of known animals.

The 2017 paper examined a refined set of specimens and found that all but one came from bears (the outlier came from a dog).

The authors conclude with finality that “the biological basis of the Yeti legend is local brown and black bears.”

Lost in Translation

But to conclude that the Yeti isn’t “real” may perpetuate a misunderstanding that began when western and eastern cultures met on the slopes of the Himalayas.

We may think of the Yeti as something of a cryptozoological hoax on par with the Loch Ness Monster.

But something about the Yeti, long present in the lore of local cultures, may have been lost in translation.

It may be that these Western strangers far from home may have simply suffered a failure of imagination and did not fully grasp the cultural context of the Yeti myth.

The major religions of the Himalayan region are polytheistic and inclusive, absorbing older folk beliefs and deities as time goes on. This yields a complex spiritual world full of magical beings and places that are in constant interaction with the landscape and affairs of people.

This perspective encompasses old gods and new gods, mountain spirits and river demons.

The purview of a deity may range from being, say, a goddess of destruction, to such minor responsibilities as guarding over a river crossing or one’s home.

Indeed, according to the traditions of Lepcha people who are indigenous to the Himalayan region, the Yeti is an ape-like glacier spirit that holds influence over the success of hunting trips.

Often, tales of the Yeti hint at something that is beyond reality. It isn’t easy to parse the first-hand reports of the Yeti – it is reported as being seen in the flesh, yet it is also given mythical powers.

For example, according to an account by Ang Tsering Sherpa who recalled a time when his father saw a Yeti, “If the Yeti had seen my father first, my father wouldn’t have been able to walk. The Yeti can make people so they can’t walk. Then he eats them.”

The real and unreal intermingle in a world full of helpful and vengeful spirits.

Among these, the Yeti was plucked from obscurity and cultural context to be scrutinized as a creature that literally walks the earth.

In retrospect, perhaps one of the most remarkable aspects of the Yeti legend is that Western science took on its potential existence as a hypothesis to test.

Is the Yeti real?

I imagine that with a certain world view, one could easily accept both answers to this question.

New Findings and Insights

Fortunately, the latest peer-reviewed study of Yetis did not merely debunk the beast. It left us with fascinating new findings about the genetics of bears and an important conservation message.

This is that the Himalayan brown bear isn’t just another bear. It is a unique creature of an ancient lineage that is in critical need of scientific and conservation attention.

Let’s hope the Himalayan brown bear gains much from its association with the Yeti.

In the end, the Yeti may be now what it has always been: a part of the mythology and folklore of its home.

When thinking of the Yeti, I am reminded of Neil Gaiman’s novel American Gods , in which deities from all the world’s religions vie for bandwidth in the human consciousness. The triumphant ones are those who hold the attention of humanity.

The Yeti is an example of a minor deity from a place remote to the Western world that has indeed captured our attention.

This “glacier spirit, god of hunting and lord of all forest beasts” is now renowned across the globe.

The Himalayas are a captivating place, thanks to both its culture and ecology. So, let’s hold on to both myth and reality: long live the Yeti, and long live the Himalayan brown bear.

Join the Discussion

Join the discussion cancel reply.

Please note that all comments are moderated and may take some time to appear.

I think some people are missing the point. It is ‘real’ in the sense that it’s based on a real creature – the Himalayan Brown Bear. But it’s more of a ‘bear-spirit’ than the real animal. As the article says, it’s a cultural thing not a zoological one. As to the Lepcha’s ape-like creature I wonder if that could be a race-memory of orang-utans, which did once inhabit the foothills of the Himalaya; or the langur monkey.

I agree with elizabeth

the yeti is maybe real. im not sure but this looks legit.

I think ‘yeti’ is not real because if he was real he would be I think found by now. I think this is why he isn’t real. When saw some pic he they looked fake and when we find some sighs then we can also find the fingerprints.

I was hiking in the Himalayas with four other people, two Americans, one Nepali, and one Brit, when I spotted something moving in the far distance across the divide on the side of another mountain, maybe two miles away from us. I asked one of the two Americans, who were on a photo safari, if I could use his high-powered lens to get better look. He allowed me to do so. When I looked I saw not one but 9 brown ape-like creatures walking in a scattered line along a path which traversed the side of a mountain. In the lead were three larger ones with two of the smallest ones in close proximity moving along together. About 30 feet behind them were three medium sized ones which were clumped together and sort of tumbling with each other as they moved along. Last, about 20 feet behind the juveniles, was the biggest one. He was also on all fours moving along the path. I described what I saw to the group. Each one took a look. Each of us saw them. Then I asked the owner of lens to take a shot. He told me he would not take a photo because it wasn’t clear. So I asked him I could watch some more.

He handed me the camera with the lens. I watched for another minute or so, and thought of taking a photo without his permission, but was worried to anger the photographer, when, while I was watching, the Nepali threw a rock which landed in the gravel below us. As I was watching the largest one stood up and searched for a second then looked directly at me. Then all of them raced up the trail and disappeared over the edge of the mountain in a matter of seconds.

The largest one’s face was unmistakably ape-like, rounded with flat features. His chest was broad with reddish hair tinged with gold. The group covered in seconds what would take a human maybe 2-3 hours or longer to climb as there was about a 45 degree angle for the side of that mountain. I took the lens from my eyes and looked at the Nepali who smirked at me when I asked him. “Why’d you do that?” He just shrugged his shoulders and laughed.

They definitely exist. But they are so fast and their senses so specified and superior that they have been able to elude us. And I am glad they have been able to do so as we are the most dangerous and cruelest of species on this planet.

Elizabeth, couldn’t agree more!!! Conserving any animal population is to keep Homo sapiens from discovering their populations!

Great piece Joe! Reminded me of a favorite paper: Lozier, J.D., Aniello, P. and Hickerson, M.J., 2009. Predicting the distribution of Sasquatch in western North America: anything goes with ecological niche modelling. Journal of Biogeography, 36(9), pp.1623-1627. https://goo.gl/Md5efF

“Nice”.

What an interesting article, with terrific photos to match. Thanks very much!

Continue Exploring

May 9, 2022

Story type: TNC Science Brief

The Yeti: Asia's Abominable Snowman

The Yeti, once better known as the Abominable Snowman, is a mysterious bipedal creature said to live in the mountains of Asia. It sometimes leaves tracks in snow, but is also said to dwell below the Himalayan snow line. Despite dozens of expeditions into the remote mountain regions of Russia, China and Nepal, the existence of the Yeti remains unproven.

The Yeti is said to be muscular, covered with dark grayish or reddish-brown hair, and weigh between 200 and 400 lbs. (91 to 181 kilograms) It is relatively short compared to North America's Bigfoot, averaging about 6 feet (1.8 meters) in height. Though this is the most common form, reported Yetis have come in a variety of shapes.

History of the Yeti

The Yeti is a character in ancient legends and folklore of the Himalaya people. In most of the tales, the Yeti is a figure of danger, author Shiva Dhakal told the BBC . The moral of the stories is often a warning to avoid dangerous wild animals and to stay close and safe within the community.

Alexander the Great demanded to see a Yeti when he conquered the Indus Valley in 326 B.C. But, according to National Geographic, local people told him they were unable to present one because the creatures could not survive at that low an altitude.

In modern times, when Westerners started traveling to the Himalayas, the myth became more sensational, according to the BBC. In 1921, a journalist named Henry Newman interviewed a group of British explorers who had just returned from a Mount Everest expedition. The explorers told the journalist they had discovered some very large footprints on the mountain to which their guides had attributed to "metoh-kangmi," essentially meaning "man-bear snow-man." Newman got the "snowman" part right but mistranslated "metoh" as "filthy." Then he seemed to think "abominable" sounded even better and used this more menacing name in the paper. Thus a legend was born.

In her book " Still Living? Yeti, Sasquatch, and the Neanderthal Enigma " (1983, Thames and Hudson), researcher Myra Shackley offers the following description, reported by two hikers in 1942 who saw "two black specks moving across the snow about a quarter mile below them." Despite this significant distance, they offered the following very detailed description: "The height was not much less than eight feet ... the heads were described as 'squarish' and the ears must lie close to the skull because there was no projection from the silhouette against the snow. The shoulders sloped sharply down to a powerful chest ... covered by reddish brown hair which formed a close body fur mixed with long straight hairs hanging downward." Another person saw a creature "about the size and build of a small man, the head covered with long hair but the face and chest not very hairy at all. Reddish-brown in color and bipedal, it was busy grubbing up roots and occasionally emitted a loud high-pitched cry."

It's not clear if these sightings were real, hoaxes or misidentifications, though legendary mountaineer Reinhold Messner, who spent months in Nepal and Tibet, concluded that large bears and their tracks had often been mistaken for Yeti. He describes his own encounter with a large, unidentifiable creature in his book " My Quest for the Yeti: Confronting the Himalayas' Deepest Mystery " (St. Martin's, 2001).

In March 1986, Anthony Wooldridge , a hiker in the Himalayas, saw what he thought was a Yeti standing in the snow near a ridge about 500 feet (152 meters) away. It didn't move or make noise, but Wooldridge saw odd tracks in the snow that seemed to lead toward the figure. He took two photographs of the creature, which were later analyzed and proven genuine.

Many in the Bigfoot community seized upon the photos as clear evidence of a Yeti, including John Napier , an anatomist and anthropologist who had served as the Smithsonian Institution's director of primate biology. Many considered it unlikely Wooldridge could have made a mistake because of his extensive hiking experience in the region. The following year, researchers returned to where Wooldridge had taken the photos and discovered that he had simply seen a dark rock outcropping that looked vertical from his position. It was all a mistake — much to the embarrassment of some Yeti believers.

Yeti evidence?

Most of the evidence for the Yeti comes from sightings and reports. Like Bigfoot and the Loch Ness monster , there is a distinct lack of hard proof for the Yeti's existence, though a few pieces of evidence have emerged over the years.

In 1960, Sir Edmund Hillary, the first man to scale Mt. Everest , searched for evidence of the Yeti. He found what was claimed to be a scalp from the beast, though scientists later determined that the helmet-shaped hide was in fact made from a serow, a Himalayan animal similar to a goat.

In 2007, American TV show host Josh Gates claimed he found three mysterious footprints in snow near a stream in the Himalayas. Locals were skeptical, suggesting that Gates — who had only been in the area for about a week — simply misinterpreted a bear track. Nothing more was learned about what made the print, and the track can now be found not in a natural history museum but instead in a small display at Walt Disney World.

In 2010, hunters in China caught a strange animal that they claimed was a Yeti. This mysterious, hairless, four-legged animal was initially described as having features resembling a bear, but was finally identified as a civet , a small cat-like animal that had lost its hair from disease.

A finger once revered in a monastery in Nepal and long claimed to be from a Yeti was examined by researchers at the Edinburgh Zoo in 2011. The finger generated controversy among Bigfoot and Yeti believers for decades, until DNA analysis proved that the finger was human, perhaps from a monk's corpse. [See also: Bigfoot & Yeti DNA Study Gets Serious ]

Russian search for Yeti

The Russian government took an interest in the Yeti in 2011, and organized a conference of Bigfoot experts in western Siberia. Bigfoot researcher and biologist John Bindernagel claimed that he saw evidence that the Yeti not only exist but also build nests and shelters out of twisted tree branches. That group made headlines around the world when they issued a statement that they had "indisputable proof" of the Yeti, and were 95 percent sure it existed based on some grey hairs found in a clump moss in a cave.

Bindernagel may have been impressed, but another scientist who participated in the same expedition concluded that the "indisputable" evidence was hoaxed. Jeff Meldrum, a professor of anatomy and anthropologist at Idaho State University who endorses the existence of Bigfoot, said that he suspected the twisted tree branches had been faked. Not only was there obvious evidence of tool-made cuts in the supposedly "Yeti-twisted" branches, but also the trees were conveniently located just off a well-traveled trail and hardly in a remote area.

Meldrum concluded that the whole Russian expedition was more of a publicity stunt than a serious scientific endeavor, likely designed to increase tourism in the impoverished coal-mining region. Despite quasi-official claims of "indisputable proof" of the Yeti, nothing more has come of the story.

DNA samples

In 2013, Oxford geneticist Bryan Sykes put out a call to all Yeti believers and institutions around the world claiming to have a piece of Yeti hair, teeth or tissue taken from a sighting. He received 57 samples, 36 of which were chosen for DNA testing, according to University College London (UCL) . These samples were then compared with the genomes of other animals stored on a database of all published DNA sequences.

Most of the samples turned out to be from well-known animals, such as cows, horses and bears. However, Sykes found that two of the samples (one from Bhutan and the other from India) were a 100 percent match for the jawbone of a Pleistocene polar bear that lived sometime between 40,000 and 120,000 years ago — a period of time when the polar bear and closely related brown bear were separating as species, according to BBC . Sykes thought the sample was probably a hybrid of a polar bear and a brown bear.

However, two other scientists, Ceiridwen Edwards and Ross Barnett, conducted a re-analysis of the same data. They said that the sample actually belonged to a Himalayan bear, a rare subspecies of the brown bear. Their study results were published in the Royal Society journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Another team of researchers, Ronald H. Pine and Eliécer E. Gutiérrez , also analyzed the DNA and also concluded that "there is no reason to believe that Sykes et al.'s two samples came from anything but ordinary brown bears."

And in 2017, yet another team of researchers analyzed nine "Yeti" specimens , including bone, tooth, skin, hair and fecal samples collected from monasteries, caves and other sites in the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau. They also collected samples from bears in the region and from animals elsewhere in the world.

Of the nine yeti samples, eight were from Asian black bears, Himalayan brown bears or Tibetan brown bears. The ninth was from a dog.

True believers undeterred

The lack of hard evidence despite decades of searches doesn't deter true believers; the fact that these mysterious creatures haven't been found is not taken as evidence that they don't exist, but instead how rare, reclusive, and elusive they are. Like Bigfoot, a single body would prove that the Yeti exist, though no amount of evidence can prove they don't exist. For that reason alone, these animals — real or not — will likely always be with us.

Additional reporting by Traci Pedersen, Live Science contributor.

Additional resources

- BBC: Is the Himalayan Yeti a real animal?

- Bigfoot Encounters: An encounter in Northern India, by Anthony B. Wooldridge

- Committee for Skeptical Inquiry: No Reason to Believe That Sykes’s Yeti-Bear Cryptid Exists

Ever seen Bigfoot's eyeshine in your headlights at night? Heard a splash and sworn you saw Nessie's tail disappearing below the lake surface? Cryptic creatures of myth and legend are known the world over.

Bigfoot, Nessie & the Kraken: Cryptozoology Quiz

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

'Yeti hair' found in Himalayas is actually from a horse, BBC series reveals

Haunting 'mermaid' mummy from Japan is a gruesome monkey-fish hybrid with 'dragon claws,' new scans reveal

China rover returns historic samples from far side of the moon — and they may contain secrets to Earth's deep past

Most Popular

- 2 Newly deciphered papyrus describes 'miracle' performed by 5-year-old Jesus

- 3 Earth's rotating inner core is starting to slow down — and it could alter the length of our days

- 4 Long-lost Assyrian military camp devastated by 'the angel of the Lord' finally found, scientist claims

- 5 32 of the most dangerous animals on Earth

- 2 Astronauts stranded in space due to multiple issues with Boeing's Starliner — and the window for a return flight is closing

- 3 James Webb telescope spots a dozen newborn stars spewing gas in the same direction — and nobody is sure why

- 4 Human ancestor 'Lucy' was hairless, new research suggests. Here's why that matters.

- 5 'The early universe is nothing like we expected': James Webb telescope reveals 'new understanding' of how galaxies formed at cosmic dawn

New Research

Most “Yeti” Evidence Is Actually From Brown Bears

The results dispel the idea of these mythical beasts while providing clues to the ancestry of the elusive Himalayan and Tibetan bears

Jason Daley

Correspondent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/39/8b398670-5883-43b5-8606-dc15f3fcfd32/yeti_bone.jpg)

The yeti, aka the Abominable Snowman, has been part of Himalayan lore for centuries —but has also long intrigued people around the world. Even Alexander the Great demanded to see a yeti when he conquered the Indus Valley in 326 B.C. (he was told they only lurked at higher altitudes). Modern explorers have also tried to track the elusive beast, collecting "evidence" in the form of scat, hair, bones and more from across the Himalayan mountain range.

Now, reports Sarah Zhang at The Atlantic , some of the best of this evidence has been put to the test. And it turns out, most yeti samples actually come from brown bears.

The latest tale began with the filming of a special production on the yeti for the cable television channel Animal Planet. As Zhang reports, the production company, Icon Films, contacted biologist Charlotte Lindqvist in the fall of 2013 with a request: they needed DNA testing of yeti evidence.

Lindqvist is a professor at University of Buffalo who specializes in species genetics and agreed to the unusual project. So the team began sending her samples. According to Sid Perkins at Science , these included a tooth and hair collected from Tibet in the 1930s , scat that was in the collections of a museum operated by the Italian mountaineer and Yeti-chaser Reinhold Messner , as well as a leg bone and other hair samples—all of these were claimed to come from yetis.

In all, Lindqvist and her colleagues examined the mitochondrial DNA of nine supposed yeti samples. They also studied 15 additional samples obtained from Lindqvist's network of contacts that were from Himalayan and Tibetan brown bears and Asian black bears for comparison. They detailed their results in a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Of the nine purported yeti samples, seven came from Himalayan or Tibetan brown bears, one came from a black bear, and one came from a dog. While the producers and "true believers" are likely dismayed by the finding, Lindqvist was ecstatic.

Though it would've been a coup to find some yeti DNA, Lindqvist was after the genetic material of the brown bear sub species—creatures that are still elusive but more rooted in reality.

“When I had to reveal to them that okay, these are bears, I was excited about that because it was my initial motive to get into this,” Lindqvist tells Zhang. “They obviously were a little disappointed.”

As Perkins reports, the team did indeed find some interesting data from the samples. They were able to create the first full mitochondrial genomes for the Himalayan brown bear ( Ursus arctos isabellinus ) and the Himalayan black bear ( Ursus thibetanus laniger ). As Zhang reports, the research also showed the Himalayan brown bear and the Tibetan brown bear are more genetically distinct from one another than previously thought.

Brown bears roam across the northern hemisphere, and many subspecies, like the American grizzly and Alaskan Kodiak bear, are spread across the world, reports Ben Guarino at The Washington Post . The research indicates that the Himalayan subspecies was likely the first to diverge from the ancestral brown bear about 650,000 years ago.

“Further genetic research on these rare and elusive animals may help illuminate the environmental history of the region, as well as bear evolutionary history worldwide—and additional 'Yeti' samples could contribute to this work,” Lindqvist says in a press release . As Zhang reports, the research also puts the kibosh on another theory that emerged from a previous Icon Films investigation of yetis. For that film, the company collaborated with Oxford geneticist Bryan Sykes who examined yeti samples, concluding that one sample matched the DNA from an ancient polar bear. That led to some speculation that the yeti might be a hybrid of a brown bear and polar bear. However, re-examination found that the sample came from a Himalyan brown bear , and Lindqvist believes she sequenced hair from the same sample, confirming that the creature was nothing out of the ordinary.

Even if science doesn't support the yeti's existence, don’t worry: We’ll always have Sasquatch. This mythical beast continues to persist in popular culture amid a sea of hoaxes, blurry photos and breathless cable shows .

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Jason Daley | | READ MORE

Jason Daley is a Madison, Wisconsin-based writer specializing in natural history, science, travel, and the environment. His work has appeared in Discover , Popular Science , Outside , Men’s Journal , and other magazines.

Yeti Legends Are Based on These Real Animals, DNA Shows

The best look yet at supposed Yeti samples also offers valuable insight into the genetic histories of rare Himalayan bears.

Among the snowy peaks of Nepal and Tibet, stories tell of a mysterious ape-like creature called the Yeti. Purported to be a towering human-like figure covered in shaggy fur, the Yeti continues to excite dedicated believers still hoping for evidence that the mythical beast is real. (Read about a man who searched for the Yeti for 60 years .)

Now, DNA analysis of multiple supposed Yeti samples—including hair, teeth, fur, and feces—shows that the stories are based on real animals roaming the high mountains. The results, published this week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B , are the best evidence yet that the Yeti legend is rooted in Himalayan black and brown bears .

Study leader Charlotte Lindqvist of the University at Buffalo in New York and her team examined nine Himalayan Yeti samples from museums and private collections. One was a tooth from a stuffed specimen at the Reinhold Messner Mountain Museum in Italy. Another was a piece of skin from a supposed Yeti hand that became a religious relic in a monastery.

Their detailed DNA work shows that the tooth came from a domestic dog , while the rest of the samples clearly came from Himalayan and Tibetan subspecies of brown bear and an Asian black bear. The results offer a window into the origins of Yeti stories, which have been told for centuries.

“Analysing Yeti samples and showing that the majority are from bears provides a connection between the myths of a rare wildman and a real creature which can occasionally be scary,” says Ross Barnett, an evolutionary biologist and expert on ancient DNA at Durham University in the U.K.

The work also allowed the team to create a new family tree of vulnerable subspecies of Asian bears, which may prove useful in efforts to protect the animals.

Enduring Myth

Lindqvist, who is currently a visiting associate professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, became interested in Yeti lore due to a scientific misunderstanding.

She was involved in the discovery and analysis of a 120,000-year-old polar bear jawbone found in Arctic Norway in 2004. Almost a decade later, she saw her work cited in a University of Oxford study linking that polar bear jaw to Yeti remains.

According to the now controversial paper published in 2014 , two Yeti fur samples from Bhutan and northern India matched up to the ancient polar bear DNA. The team behind it argued that a polar bear-brown bear hybrid could still be alive somewhere in the snowy mountaintops. Lindqvist, however, was not convinced and decided to double check the findings for herself.

“I got a little bit suspicious about how there could be polar bears in the Himalayas,” she says. She also had concerns about the study methods, because the team looked at relatively short and limited sections of DNA.

Her team gathered a total of 24 samples from Asian bears and purported Yetis. While the team could not get their hands on the exact fur samples analysed four years ago, Lindqvist suspects that one of her samples came from the Indian animal. They completed a more detailed analysis of longer DNA sequences, which she says is more likely to yield robust results.

“This study clearly confirms that the Yeti samples tested are actually from bears living in the Himalayas and the Tibetan region,” says Bill Laurence , a conservation biologist at James Cook University in Queensland, Australia, who was not involved in the new paper.

For Lindqvist, collecting and studying so-called Yeti remains was “a nice segue into possibly getting samples and getting better insight into the evolutionary history of bears in the region.”

For instance, her team’s new family tree suggests that while Tibetan brown bears are closely related to brown bears from Europe and North America, critically endangered Himalayan brown bears are part of an older lineage that may have split off from all other bears 650,000 years ago during a period of ice age glaciation.

Barnett says that the new study is doubly important because, prior to this, there had been very little genetic work done on the vulnerable or endangered bears of the region. He hopes the paper will increase understanding of Himalayan brown bears and aid in their conservation.

But even with the robust nature of the new genetic findings, Barnett adds, the legend of the Yeti will likely live on.

“You can’t debunk a myth with anything as mundane as facts,” he says. “As long as the stories are told and retold—and bears are glimpsed in other than ideal conditions or leave melting footprints in the snow—there will be stories of Yetis.”

Follow John Pickrell on Twitter .

Related Topics

You may also like.

Dog DNA tests are on the rise—but are they reliable?

Wild animals are adapting to city life in surprisingly savvy ways

Animal-friendly laws are gaining traction across the U.S.

Surrounded by sounds—of music, science, animals, and more

How the DNA method that caught the Golden State Killer can help catch elephant poachers

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Race in America

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Destination Guide

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Latest DNA Analysis Shows The Yeti Are Actually Just a Bunch of Bears

The Yeti of the mountains of Asia, hairy like a white ape, yet bipedal and standing taller than a man, is numbered among the world's most beloved cryptids. Yet, for all the eyewitness accounts, physical evidence of the beast is proving tricky to pin down.

Nary a fossil, nor a corpse. But, like its American cousin Bigfoot, pieces of hair and bone, of tooth and skin, have made their way into private collections. Now, DNA analysis on nine of those has proven there's still no physical evidence - all those samples came from regular old animals.

The nine samples, collected from the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau, included hair, skin, tooth, bone, and faecal matter. All but one of them turned out to be from bears - Asian black bears, Himalayan brown bears, or Tibetan brown bears.

The remaining sample, a tooth from the Reinhold Messner Mountain Museum, was from a domestic dog.

"Our findings strongly suggest that the biological underpinnings of the Yeti legend can be found in local bears, and our study demonstrates that genetics should be able to unravel other, similar mysteries," said biologist Charlotte Lindqvist from the University at Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences.

Her team isn't the first to conduct DNA analysis on what was believed to be samples of cryptid hair.

In 2014, a team of researchers at the University of Oxford in the UK and the Museum of Zoology in Lausanne, Switzerland, led by Oxford geneticist Bryan Sykes, published a paper describing how they had put 37 hair samples from around the world to the test.

It was the first ever genetic survey of "anomalous primate" samples, and it had, well, a similar result. Every single one of the samples that returned a result matched a known species - from polar bear to sheep to human.

That research, however, was based on a simpler genetic test than the research her team conducted, Lindqvist said. Sykes and his team used mitochondrial RNA sequencing.

Lindqvist and her team applied PCR amplification, mitochondrial sequencing, mitochondrial genome assembly, and phylogenic analysis.

Sykes - not without his detractors among the cryptid enthusiast community - was nevertheless careful to note that a lack of evidence was not proof for the non-existence of anomalous primates.

"Rather than persisting in the view that they have been 'rejected by science', advocates in the cryptozoology community have more work to do in order to produce convincing evidence for anomalous primates and now have the means to do so," Sykes' team wrote in their paper .

Lindqvist draws a different conclusion - that the yeti-cum-bear samples provide evidence that the cryptid myth may have evolved from encounters with real animals.

Just as the okapi, discovered in 1901, was reportedly fabled as an " African unicorn ," for instance, or remains of Australia's megafauna could have given rise to Aboriginal myths such as the Giant Devil Dingo .

"Clearly," Lindqvist said , "a big part of the Yeti legend has to do with bears."

But the research has other applications outside of cryptid research - the DNA sequenced, when compared to living or modern animals, can provide some insight into the evolution of the bears, many of which are vulnerable or endangered.

The team sequenced the mitochondrial DNA of 23 Asian bears (including the Yeti samples) and compared it with other bears around the world.

They found that Tibetan brown bears are closely related to American bears, but Himalayan bears belong to a different evolutionary lineage that split around 650,000 years ago, during a major ice age .

This could have occurred when the ice significantly changed the landscape, separating groups of bears that then followed separate evolutionary paths.

"Further genetic research on these rare and elusive animals may help illuminate the environmental history of the region, as well as bear evolutionary history worldwide - and additional 'Yeti' samples could contribute to this work," Lindqvist said .

The Yeti samples were provided to Lindqvist by production company Icon Films for an Animal Planet special called " Yeti or Not ."

The research has been published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B .

When Edmund Hillary Went in Search of the Yeti

In 1961, the pursuit of the abominable snowman was still taken seriously..

The Yeti Scalp of Khumjung

September 9, 1960: Kathmandu hums with the discordant music of drums and flutes. People disguised as dancing deities have traveled from all over Nepal to clap and sing their way through the streets as part of a festival honoring the Hindu god Indra, revered as the king of heaven. Amid the colorful melee winds 40-year-old Brit Desmond Doig, mountaineer, journalist, and photographer for National Geographic and Life magazine.

In the midst of the chaos, Doig spots a shaggy-haired wool and bamboo figure halfway between a man and an ape adorning the wall of a temple. “To the Nepali they are ‘Ban Manchhuru’,” Doig writes in the 1962 book High in the Thin Cold Air . “To our Sherpas and us… the figures represent the Abominable Snowman.”

Doig hadn’t traveled all the way to the Nepali capital to honor Indra. As part of the 1960-61 Silver Hut expedition led by Edmund Hillary, then the world’s most famous mountaineer, Doig had come in search of a creature that, like a god, occupied the rarified air between myth and reality. He had come in search of Nepal’s abominable snowman, also known as the yeti.

In the 1950s and early ‘60s the Western world was in the grip of yeti mania. In 1951, the legendary mountaineer Eric Shipton had photographed what he believed to be yeti tracks in northeastern Nepal. The following year, Hillary himself encountered a scrap of skin covered in blue-black fur while climbing in the Cho Oyu region of the Himalayas and was told by his Sherpa porters that the hair belonged to a yeti.

Following two bloody World Wars and indeed, Hillary’s earlier exploits, the vast majority of the globe was now known to Western audiences. The sections of the map reading “Here be monsters” were growing fewer and fewer, yet the appetite for undiscovered lands and unseen monsters had never been stronger.

Belief in the yeti can be traced to pre-Buddhist religions, but widespread interest came about as Western mountaineers first began to climb the Himalayas and brought the local legends home with them. When the race to conquer Everest heated up in the 1950s, so too did the number of alleged yeti sightings. Western audiences were hooked, eager for news of this evolutionary hangover halfway between man and beast. Perhaps it was comforting to think that there were beings beyond comprehension surviving at the ends of the wilderness and that, crucially, there were still enough wild places left to hold them.

So popular was the yeti legend that British newspaper the Daily Mail launched its own expedition to Nepal in 1953. The trip cost the equivalent of $1.35 million in today’s money but ultimately failed to find any proof of the yeti. All of which simply meant that in 1960 yetis were still out there to be found.

“The yeti wasn’t considered mythical in the early ’60s,” explains Graham Hoyland, mountaineer and author of Yeti: An Abominable History. Hoyland points to the Nepali government’s official 1947 memo outlining the etiquette of a yeti hunt, republished by the American embassy in Kathmandu in 1959 and issued to Hillary’s party as “ Regulations Covering Mountain Climbing Expeditions in Nepal Relating to Yeti.” It stipulates that the search for yetis required a permit and that a yeti could not be killed except in self-defense.

That Edmund Hillary might set off in search of the abominable snowman, then, was not the wild, conspiracy-theory-baiting story it would appear to be today. That he and Doig might actually encounter a wild yeti was considered a very real possibility.

It was in this spirit that the Hillary expedition set out into the Rolwaling Valley on the morning of September 10, 1960. The valley selected because Sherpas had reported yeti sightings in the area and because of its proximity to Mount Makalu, the world’s fifth highest mountain; the nine-month expedition would go on to study the effects of long-term exposure to high altitudes on human fitness after the search for the yeti was concluded.

Among those traveling on the dual-purpose expedition were Peter Mulgrew and Wally Romanes, who had accompanied Hillary on his 1955-58 expedition to Antarctica; American space physiologist Dr Tom Nevison and glaciologist Barry Bishop, both well suited to measuring the effects of long-term altitude exposure; and Marlin Perkins, director of the Lincoln Park Zoo, and Dr Larry Swan a self-described “Himalayanist,” whose expertise seemed ideal for a yeti hunt. In other words, this was a serious, well-funded and professional expedition, one backed by World Book Encyclopedia

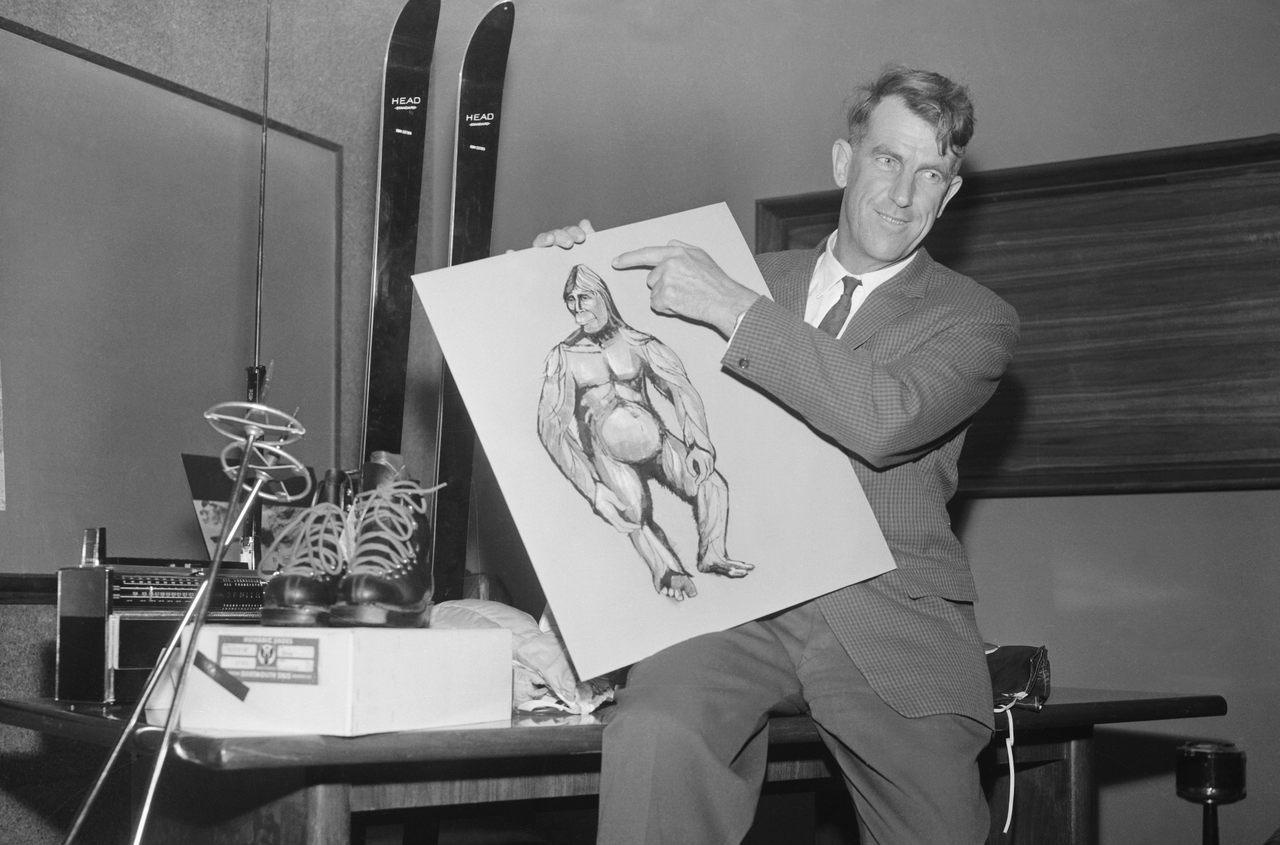

The group would study local stories, tracks and relics purported to be Yeti body parts in order to establish or disprove the legend. “Our ambition, of course, was to capture a live Snowman,” writes Doig. Hillary seemed more skeptical. “I think there is precious little in civilisation to appeal to a Yeti,” Doig reports him as saying.

According to Sherpa legend, the yeti is a genus of high-altitude-dwelling, ape-like creatures with three distinct species: the dzu-teh is a six-to-eight-foot bearlike creature covered in either blond, red, black, or gray hair. Despite being largely vegetarian, dzu-tehs have been known to deploy its long claws in the hunting of cattle. The mih-teh is a two-legged creature the size of a small man and is covered in black or red hair with a long mane hanging over its eyes. Finally, Doig writes, the thelma is said to be a “sad-faced, dwarf-sized beast found in dense forests below 10,000 feet.”

The sheer amount of firepower taken along by the explorers demonstrates a significant sense of caution toward the animal that might or might not exist. Their armory included Cap-Chur guns capable of firing tranquilizer darts as well as rifles, shotguns, tear gas pistols, and “light arms.” “None of us particularly wanted to shoot one,” wrote Doig. “But we carried conventional rifles in self-defense as most accounts of the Yeti describe it as being savage in the extreme.”

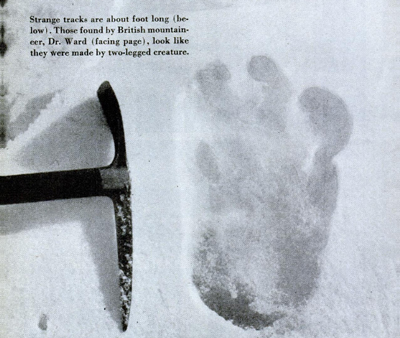

The climbers and scientists were never called upon to defend themselves. The closest they came to encountering a yeti was the strange footprints they found in the snow. Located 20 to 30 inches apart, Doig writes, the prints seemed to be made “by naked human feet—size elevens or even fifteen, broad across the instep, fallen arches, and a big toe that protruded inward.”

Hillary dismissed the prints as having been made by snow leopards or wolves and claimed, “I would like a lot more convincing proof.” Doig, Swan, Perkins, and a few others set to work documenting the tracks with sketch books and measuring tapes, taking photographs, and attempting to make plaster of Paris casts, but it soon became clear that the prints were not made by a mysterious creature, but by the hot sun, which distended the tracks of much smaller, perfectly ordinary animals.

With the Yeti prints discredited, the only remaining “proof” came in the form of scraps of “relics” many locals seemed keen to sell at high prices, such as a “yeti hand” stored at a monastery in Pangboche; an analysis of a photograph revealed it to most likely be a human hand strung together with wire. Likewise, the numerous yeti skins shown to the expedition team—mostly blue-black with a white stripe across the shoulders—were widely agreed to belong to the Tibetan blue bear.

Three Yeti “scalps” held at local monasteries were the hardest pieces of evidence to disprove. After much wrangling, Hillary was given permission to take one scalp abroad for one month to be examined by scientists in Paris, Chicago, and London.

“I have never believed in the existence of the snowman,” Hillary outright claimed in an interview conducted with Stars and Stripes at the start of the scalp’s scientific tour. But he did allow for the possibility he was wrong. “The scalp is hard to explain. It’s a convincing sort of specimen,” he says, likely out of deference to the Sherpa people. “The local people regard it as a yeti scalp and look upon it with respect.”

Eventually, the scientists agreed the scalp was likely a fake, possibly constructed from the skin of a serow, a goat-like creature found in the Himalayas. “Pleasant though we felt it would be to believe in the existence of the Yeti,” Hillary wrote in High in the Thin Cold Air , “when faced with the universal collapse of the main evidence in support of this creature the members of my expedition … could not in all conscience view it as more than a fascinating fairy tale.”

If Hillary had always doubted the existence of the yeti, why set off on a hunt at all? Ed Douglas, author of Tenzing: Hero of Everest and Himalaya: A Human History , suggests that Hillary used the headline-grabbing yeti hunt to get funding for the research portion of the expedition. “The yeti was a useful marketing tool,” writes Douglas. “I doubt Hillary really believed in it except when he was talking to PR people.”

Hoyland, who claims to have encountered a yeti footprint in Bhutan, believes otherwise. “Hillary was a mountaineer, and any mountaineer will jump at the opportunity to go and hunt for a yeti. I did, too.”

Whether Hillary’s Yeti hunt was a public relations stunt or something more, not everyone was satisfied by the expedition’s findings, which came as popular belief in the yeti’s existence began to fade. “I hope we are wrong about the yeti,” Doig wrote in High in the Thin Cold Air . “Whatever one may think of the legend… there certainly is something in the high Himalayas to spark the descriptions of a shaggy red monster walking usually on two feet.”

Podcast: Panorama of the City of New York

Using an ad blocker?

We depend on ad revenue to craft and curate stories about the world’s hidden wonders. Consider supporting our work by becoming a member for as little as $5 a month.

DNA Says 'Yeti' Evidence Comes From Bears, But Will Believers Be Convinced?

Could 'Monsters' Exist in the Modern World?

Podcast: Hårgaberget

Objects of Intrigue: Yeti Scalp

Here Be Dragons: Secrets of One of the Earliest Terrestrial Globes

Meet Nepal’s Mountain Porters

The Story Behind This Giant Rock in the Middle of a Field | Untold Earth

How the Fictional Town of Sleepy Hollow Became Real

Atlas Obscura Tries: Magnet Fishing

A 30-Acre Garden Inspired by the Principles of Modern Physics

The Flesh-Eating Beetles of Chicago's Field Museum

Inside Ohio's Experimental Archaeology Lab

A Visit to Buffalo's Lava Lab

Where Scientists Play With Fire

A Colossal Squid Is Hiding in New Zealand

This Volcano Won't Stop Erupting | Untold Earth

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Pre-Order Atlas Obscura: Wild Life Today!

Add some wonder to your inbox, we'd like you to like us.

Mysteries of the yeti

He authors of a recent proceedings b article on the evolutionary history of brown bears used genetic analyses to show the phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of himalayan and tibetan bears, thus shedding light on the possible identity of the yeti..

The exact identity of the yeti, an ape-like creature, important to folklore and mythology in the Tibetan Plateau-Himalaya region is still surrounded by mystery. The authors of a recent Proceedings B article on the evolutionary history of brown bears used genetic analyses to show the phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of Himalayan and Tibetan bears, thus shedding light on the possible identity of the yeti. We spoke to lead author, Charlotte Lindqvist about this fascinating research and findings.

Tell us about yourself and your research?

I’m an Associate Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University at Buffalo, currently a Visiting Associate Professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. I am an evolutionary geneticist, broadly interested in understanding the processes and patterns of species diversification, and how it is impacted by hybridisation and responses to environmental perturbations, in both animals and plants. One of my research projects involves polar and brown bear evolutionary history and I am sequencing genomes of both modern and ancient, subfossil bears. I find it fascinating how such large and iconic animals display an excellent example of complex speciation in response to climatic changes. This is something we, today, can address much better than ever with genomic data.

What does your paper tell us?

The findings of our paper are two-fold. First, we conducted a comprehensive genetic survey to explore the identity of animal remains. These included bone, skin, hair and fecal samples that had been collected in the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau and were thought by locals to have come from yetis. By analysing the DNA from these samples, we were able to directly determine that they belonged to local black and brown bears. Secondly, as our ultimate goal was to infer the evolutionary history of bears in the region, we sequenced mitochondrial DNA, including complete mitochondrial genomes from some of these animal remains, and reconstructed their phylogenetic history. We show that the Himalayan brown bear, which is a subspecies of brown bear, is the first-branching lineage of modern brown bears, while the Tibetan brown bear, another subspecies, diverged much later. The Himalayan black bear also appears to hold an isolated position among Asian black bears.

Did you discover anything surprising?

Because many of the samples we worked with were of unknown identity, it was exciting to discover that these samples were in fact related to local bears. Although it has previously been anecdotally associated with local bears, the exact identity of the yeti is still surrounded by mystery. A previous study , recently published in Proceedings B, and based on only two purported yeti samples and limited genetic data, had speculated that an unclassified, and possibly hybrid, bear species might be present in the region, but this preliminary finding had been questioned. Our results refute that finding and strongly suggest that the biological basis of the yeti legend is local brown and black bears, and not a mythical creature or previously unknown bear species.

We were also surprised to find the Himalayan brown bear placed at the base of the brown bear family tree as sister lineage to all other modern brown bears. Genetic relationships of most of the world’s brown bear populations have been fairly well studied but very limited data existed of the Himalayan brown bear and it was not clear how these endangered and elusive bears from the northwestern Himalayan region were related to other brown bear populations. It was a similar story with the Himalayan black bear. Our results indicate that both of these bear populations diverged early and experienced long isolation from other bear populations, likely in response to major glaciation events in the region.

What implications does your research have on the field?

To my knowledge, this study represents the most rigorous analysis to date of samples suspected to derive from anomalous or mythical ‘hominid’-like creatures, and it demonstrates that genetics will be able to unravel other, similar mysteries. In recent years, the techniques of recovering DNA from historical and ancient samples have vastly improved and our study also helps to demonstrate that biological samples archived in museums or private collections can significantly aid in our understanding of the genetic variation and phylogeographic patterns of rare and widespread species that may otherwise be difficult to get hold of.

I also hope that our study will help increase the attention on bears in this region. Both brown and black bears in the Himalayas are either vulnerable or critically endangered but not much is known about them. Our study helps placing these bear populations in a global perspective, e.g., they appear to hold important clues to the evolutionary history of bears around the world and likely also the climatic history of the geologically dynamic and young Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau. It is clear that increasing knowledge on their population structure and genetic diversity will not only be important for studies of worldwide brown bear populations but also for estimating population sizes and guiding conservation management strategies of bears in the region.

What made you submit to Proceedings B and what was your experience of the process?

An earlier study about the identity of purported yeti samples had been published in Proceedings B and I thought it would be an appropriate place to submit our paper. But also, I have long known about the journal as a highly respected journal that publishes excellent research of broad impact and felt our work could live up to the rigorous and high standards of the journal. Publishing in Proceedings B was a positive experience and I was impressed by the efficient and quick process.

Proceedings B is looking to publish more high-quality research articles and reviews in the field of evolution. If you have an idea for a review, we strongly encourage you to submit a proposal by completing our proposal template and sending it to the journal. Find out more information about the journal and the submission process .

Main image: Himalayan brown bear from the Deosai National Park, Pakistan. Image credit: Abdullah Khan, Snow Leopard Foundation

Shalene Singh-Shepherd

Senior Publishing Editor, Proceedings B

Related blogs

Madelyn Hernández

In history of science

The many faces of Mary Somerville

Madelyn Hernández examines how a diverse array of representations enriched the legacy of Mary…

Dr Stella Butler

Pioneering women

To mark International Women’s Day, Dr Stella Butler celebrates the achievements of the first women…

Virginia Mills

The Lady and the Leviathan

Virginia Mills celebrates Stereoscopy Day by telling the story of Lady Mary Rosse, the…

Email updates

We promote excellence in science so that, together, we can benefit humanity and tackle the biggest challenges of our time.

Subscribe to our newsletters to be updated with the latest news on innovation, events, articles and reports.

What subscription are you interested in receiving? (Choose at least one subject)

Five Pieces Of Yeti Evidence That’ll Make Skeptics Wish They Were Believers

Proving the Yeti’s existence has become a lifelong endeavor for some. Whether you believe or not, the stories of how people have attempted to demonstrate the Yeti’s existence are bound to entertain.

Animal Planet

Just this week, a groundbreaking study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that Earth is home to well over 1 trillion species, 99.999 percent of which have yet to be discovered.

While this new study focuses on microorganisms, it’s also reminded everyone that of those trillion-plus species, Earth contains about 8.7 million complex lifeforms of the group that includes plants and animals — and that 86 percent of that group has yet to be identified by science.

Refining the lens even further, we must remember the epochal 2004 Nature report, which found evidence that primitive, hobbit-like people ( Homo floresiensis ) distinct from Homo sapiens lived on Indonesia’s Flores Island as recently as 12,000 years ago, a blink of an eye as far as the planet is concerned.

Upon publishing the report, Nature editor Henry Gee wrote , “The discovery that Homo floresiensis survived until so very recently, in geological terms, makes it more likely that stories of other mythical, human-like creatures such as yetis are founded on grains of truth.”

Indeed, no other human-like creature has captivated the human imagination quite like the Yeti. And while no definitive proof of its existence has emerged, the fact that there are so many species yet to be uncovered gives Yeti believers plenty of hope.

In the meantime, they’ve got this Yeti evidence to contemplate, and more coming on Animal Planet’s Yeti or Not , premiering Sunday, May 29, from 9-11PM ET/PT.

The Shipton Footprints

Eric Shipton/Christie’s Alleged Yeti footprints photographed by Eric Shipton in the Menlung Basin, Nepal, 1951. These photographs sold at auction in 2014 for almost $12,000.

Although Yeti research has been marked by several high-profile claims and reports over the past few years, the golden age of Yeti research most likely remains the 1950s. And that golden age likely began with the Shipton footprints.

As interest in summiting Everest peaked in the years following World War II, the British led a reconnaissance expedition up the mountain in order to scout out plans for a future ascent to the very top.

That 1951 trek was led by British mountaineer Eric Shipton. As Shipton and his partners reached Menlung Basin, about 16,000-17,000 feet above sea level, they came across a long series of footprints.

At 12-13 inches long yet twice the width of an adult man’s foot (and with unusual toes), a depth suggestive of weight greater than a man’s, and claw marks nearby, these footprints almost certainly weren’t human.

Fortunately, Shipton photographed the prints. Two days later, the prints were wiped away by sun and wind — and with them the world’s first great piece of Yeti evidence.

The Khumjung Scalp

Nuno Nogueira/Wikimedia Commons The alleged Yeti scalp of Nepal’s Khumjung monastery, introduced to the Western world by famed explorer Edmund Hillary.

Two years later, building upon Shipton’s reconnaissance, Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and Nepalese Sherpa Tenzig Norgay completed what is perhaps history’s greatest feat of exploration when they became the first people to summit Everest.

But while Hillary’s mountaineering is known the world over, few realize that he was also, for a time, one of the world’s foremost Yeti hunters.

In the course of Hillary’s historic ascent, he claims to have spotted mysterious footprints in the snow on the Barun Khola mountain range, which Norgay believed came from a Yeti. However, unlike Shipton, Hillary didn’t photograph them, leaving that alleged Yeti evidence (along with the Yeti hair he’d supposedly found in the Himalayas the year before) lost to history.

In 1960, Hillary launched a full-fledged Yeti hunting expedition into the mountains of Nepal. While there, Hillary and his team visited a monastery in the village of Khumjung. There they acquired a purported Yeti scalp that had been in the village’s possession for over 200 years.

Upon Hillary’s return to London, the world was abuzz at this incredible piece of Yeti evidence — only to be let down after scientists quickly found that the “scalp” was actually the hide of a serow goat.

The “scalp” has since returned to the monastery, where it remains to this day.

PO Box 24091 Brooklyn, NY 11202-4091

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Finally, some solid science on bigfoot.

DNA analysis finds weird bears, but no evidence of Sasquatch or the Abominable Snowman

Blurry photos have long been the main evidence for Bigfoot's existence. But a new genetic analysis finds that hair samples are everything but Bigfoot.

JoshNV/Flickr ( CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 )

Share this:

By Erika Engelhaupt

July 1, 2014 at 7:05 pm

Sometimes in science, you solve one mystery just to create another. So it goes with Bigfoot.

After creating a stir last October with preliminary results, an international research team has published an analysis of dozens of hair samples from mystery animals around the world. None reveal the existence of a yeti or Bigfoot, reports Bryan Sykes , an Oxford University geneticist well-known for his research on human evolution. But two hair samples point to a possible new and (you guessed it) mysterious species: a bear roaming the Himalayas that may be related to ancient polar bears.

Some Bigfoot hunters are thrilled anyway. “It’s quite exciting,” says Loren Coleman, director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine. “This definitely shows there’s DNA in the Himalayas area of an unknown bear,” says Coleman, who embraces the use of a scientific approach to identifying creatures known only from legend. In 2013 his museum even named Sykes cryptozoologist of the year. (Crytozoologists search for animals unknown to science.)

Sykes says he started the project because he was “slightly irritated” that cryptozoologists kept saying they’ve been rejected by mainstream science. At the time, he was perfecting a technique for extracting mitochondrial DNA from a single hair shaft. “I realized I could do a proper scientific study,” he says. “I wasn’t looking for a yeti or anything like that. I was just going to do a scientific review of the evidence.”

And a less mainstream question lurked at the fringes of Sykes’ thoughts: “I’ve always been interested to know whether the Neanderthals and other types of humans became extinct,” he says. Having studied the DNA of ancient human relatives, he was fascinated by the idea that mysterious large mammals reported around the world might be tiny remnant pockets of some human relative. He decided to analyze the DNA of purported yeti samples, thinking there was maybe a 5 percent chance that he would find something interesting, maybe a new mammal species. And maybe a tiny sliver of a chance he’d find something even more surprising.

So in 2012 Sykes and his colleague Michel Sartori of the Museum of Zoology in Lausanne, Switzerland, posted a call for hair and other samples thought to be from yetis, Bigfoot or any other “cryptid” species unknown to science. The researchers would compare stretches of DNA to known species in the GenBank database, which catalogs thousands of species.

In came the hairs. There were hairs from famous expeditions, including a trek by Sir Edmund Hillary, hairs from museums, Buddhist relics, and, Sykes says, “quite a lot of material from Bigfoot enthusiasts in the United States.” Sykes whittled down 95 samples to 37 that were most interesting based on the circumstances of their collection.

Of those 37, the team was able to extract DNA from 30. “A lot of them turned out to be very ordinary animals in their natural habitats,” Sykes says. As the team reports July 1 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B , supposed yeti and bigfoot samples turned out to come from bears (brown, black and polar), horses, raccoons, one human, some canines (the test didn’t narrow down if they were wolves or dogs), cows, sheep, a North American porcupine, a Malaysian tapir and a serow, which is a known animal similar to a goat or antelope.

But two hair samples from the Himalayas were a surprise. These hairs, both brownish in color, perfectly matched a short stretch of DNA once extracted from the jawbone of a 40,000-year-old polar bear. The hairs did not match modern polar bears. One hair came from an animal shot 40 years ago in Ladakh, India, by a hunter who reported that it behaved differently from typical brown bears. The other was collected about 10 years ago in Bhutan, 600 to 800 miles from Ladakh.

The researchers’ best guess is that the hairs are from either an unknown bear species or a hybrid of a brown bear and a polar bear. Such hybrids are known in the Arctic, but genetically resemble modern, rather than ancient, polar bears. If there’s a Himalayan hybrid, it might have descended from a different, long-ago liaison between the species. But since the match between the two hairs and the ancient polar bear resulted from a fragment just 104 DNA letters long, the result is preliminary, and the team hopes to do further analysis. Sykes is even planning an expedition to Ladakh to search for live bears.

“They’re from opposite ends of the Himalayas, so it’s reasonable to imagine that there might be some still alive in between,” Sykes says. He doesn’t think the samples are a hoax, since they were collected decades and hundreds of miles apart and were provided to Sykes by different sources. Plus, only the ancient jawbone is a genetic match.

If there is a previously unknown bear species living in the Himalayas, it may be what people there have seen and reported as a yeti. Coleman says that would be consistent with those reports. “They’re always brown,” he says. The idea of a white “abominable snowman” came from TV shows like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer .

Publishing data in a respected, peer-reviewed journal is a big step for cryptozoology, even if it means finding out that yetis don’t exist. In fact, especially if it means finding out that yetis don’t exist. By subjecting samples to genetic testing, Bigfootologists risk dashing their hopes. And any scientist taking on the task may risk his or her reputation. (Sykes says he wasn’t worried what colleagues would think of his new pursuit: “I’m in the cocktail hour of my career.”)

Maybe more scientists would be willing to test “cryptid” samples, but it takes money and time. No scientist working at a university or lab capable of genetic analysis has “testing Bigfoot samples” in their job description, it’s probably safe to say. Plus, it cost Sykes $2,000 to analyze each ‘yeti’ DNA sample, and not many Bigfoot enthusiasts are keen to pay. Part of Sykes’ work was paid for by a filmmaker, but he paid for the rest himself (and points out that no government funding was used).

Finding a new bear rather than a humanlike primate may be a letdown for some Bigfootologists. But not Loren Coleman. “I’m not disappointed. The whole role of science is to keep searching. We need to have patience,” he says.

And Sykes points out that he hasn’t actually disproven that the animals exist. There’s always some chance, however small, that the right sample just hasn’t been collected. Now, he says, Bigfoot chasers “can go back into the forest knowing that if they get a genuine sample it can be identified, and to a standard that everyone will accept.”

And if the next round of samples don’t turn up yetis, or the next after that, so be it. Maybe we’ll find something interesting anyway, like more new bears. Cryptozoologists like to point to the weirdly striped okapi that was once thought to be mythical. And then there are the recent discoveries of the lesula and olinguito .

Either way, the true Bigfoot believers will undoubtedly keep on believing, even if they embrace the scientific method. After all, the fun of science lies not just in finding answers, but in the thrill of the chase.

Follow me on Twitter: @GoryErika

More Stories from Science News on Genetics

Child sacrifices at famed Maya site were all boys, many closely related

Horses may have been domesticated twice. Only one attempt stuck

Scientists are fixing flawed forensics that can lead to wrongful convictions

Thomas Cech’s ‘The Catalyst’ spotlights RNA and its superpowers

50 years ago, chimeras gave a glimpse of gene editing’s future

The largest known genome belongs to a tiny fern

Here’s why some pigeons do backflips.

A genetic parasite may explain why humans and other apes lack tails

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

29 Great Yeti Facts

Written by Rebekah Little

Modified & Updated: 30 May 2024

Ever wondered about the mysterious Yeti, often dubbed the Abominable Snowman? This elusive creature, said to roam the snowy peaks of the Himalayas, has captured imaginations and sparked debates worldwide. Is the Yeti real or just a myth? Well, hold onto your hats, because we're about to dive into 29 fascinating facts about the Yeti that might just make you a believer—or at least, give you something intriguing to ponder. From ancient legends to modern-day sightings and scientific investigations , the story of the Yeti is a rollercoaster of mystery and intrigue. Ready to get the lowdown on one of the most enigmatic figures in folklore? Let's get started on this wild ride through the snowy unknown!

Key Takeaways:

- The Yeti, also known as the "Abominable Snowman," is a mythical creature from the Himalayas, inspiring scientific investigations, cultural impact, and even tourism.

- Despite lack of concrete evidence, the legend of the Yeti continues to captivate human imagination, fueling expeditions, art, and conservation efforts in the Himalayas.

What Exactly is a Yeti?

Often referred to as the "Abominable Snowman," a Yeti is a mythical creature said to inhabit the Himalayan mountains. This elusive being has captured human imagination for centuries, with numerous expeditions undertaken to prove its existence. Despite the lack of concrete evidence, stories and supposed sightings continue to fuel the legend of the Yeti.

- Yeti is a term that comes from the Tibetan language, meaning "rocky bear."

- Locals in the Himalayas regard the Yeti not just as a myth but as a part of their rich folklore and culture.

Historical Sightings and Evidence

Throughout history, various explorers and locals have claimed to encounter the Yeti, providing a mix of anecdotal evidence and physical "proofs" like footprints in the snow.

- One of the earliest recorded Yeti sightings was by British explorer Charles Howard-Bury in 1921 during an expedition to Mount Everest.

- In 1951, Eric Shipton captured one of the most famous photographs of alleged Yeti footprints, sparking worldwide interest.

Scientific Investigations into the Yeti

Scientists have long been intrigued by the legend of the Yeti, leading to numerous studies and DNA analyses of supposed Yeti samples.

- Most DNA analyses of "Yeti" samples, such as hair or skin, have identified them as belonging to known animals like bears.

- A comprehensive study in 2017 analyzed multiple supposed Yeti artifacts and concluded most were from bears native to the area.

Cultural Impact of the Yeti

The Yeti has not only been a subject of folklore but has also influenced popular culture, appearing in movies, books, and even marketing campaigns.

- The Yeti has been featured in numerous films and television shows, often depicted as a misunderstood creature.

- Merchandise and products, including toys and video games, have been inspired by the Yeti, showcasing its impact beyond folklore.

The Yeti in Modern Expeditions

Despite the scientific community's skepticism, expeditions to find the Yeti continue, fueled by adventurers and enthusiasts hoping to uncover the truth.

- Expeditions in the 21st century have utilized modern technology, like drones and thermal cameras, in hopes of finding evidence of the Yeti.

- Although no conclusive evidence has been found, these expeditions often discover new information about the Himalayas' biodiversity.

The Yeti and Environmental Conservation

Interestingly, the legend of the Yeti has played a role in promoting environmental conservation in the Himalayas.

- Efforts to find the Yeti have led to increased awareness and interest in the conservation of its supposed habitat.

- Some conservation campaigns have used the Yeti as a symbol to promote the protection of endangered species in the region.

The Yeti in Art and Literature

The enigmatic nature of the Yeti has made it a fascinating subject for artists and writers, inspiring a variety of creative works.

- Numerous books, both fiction and non-fiction, have explored the mystery of the Yeti, contributing to its mythos.

- Artists have depicted the Yeti in various forms, from fearsome to friendly, reflecting its complex role in human culture.

The Yeti and Tourism

The mystery surrounding the Yeti has also become a tourist attraction, with many travelers visiting the Himalayas in hopes of a sighting.

- Tours and treks promising a chance to search for the Yeti attract adventure seekers from around the world.

- Museums and exhibitions in the Himalayas feature Yeti-related artifacts, drawing in curious visitors.

The Yeti in Science Fiction and Fantasy

The Yeti's appeal extends into the realms of science fiction and fantasy, where it often represents the unknown and the possibility of undiscovered creatures.

- Science fiction stories have used the Yeti as a symbol of nature's mysteries and the limits of human knowledge.

- In fantasy literature, the Yeti is sometimes portrayed as a guardian of ancient secrets or a being with magical powers.

The Yeti's Influence on Cryptozoology

Cryptozoology, the study of creatures whose existence is not substantiated by mainstream science, counts the Yeti among its most intriguing subjects.

- The Yeti is considered a "cryptid," a creature of folklore that has yet to be scientifically validated.

- Cryptozoologists continue to collect and examine evidence, hoping to prove the existence of the Yeti.

The Yeti and Global Folklore

The Yeti is just one example of a global phenomenon where cultures have legends of mysterious creatures inhabiting their wilds.

- Similar creatures to the Yeti, like North America's Bigfoot or the Australian Yowie, suggest a universal human fascination with the unknown.

- These legends often serve to explain phenomena that ancient peoples found mysterious or frightening.

The Future of Yeti Research

As technology advances, so do the methods available for searching for the Yeti, offering new hope to those convinced of its existence.

DNA testing and environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis offer promising tools for identifying unknown species in the Himalayas.

Satellite imagery and remote sensing technology could potentially uncover evidence of the Yeti's existence from afar.

Despite skepticism, interest in the Yeti remains strong, with new generations of explorers and scientists drawn to its mystery.

The Yeti's enduring legend continues to inspire curiosity and wonder, bridging the gap between myth and reality.

As long as the Himalayas remain vast and largely unexplored, the legend of the Yeti will persist, captivating the imaginations of people worldwide.

The quest for the Yeti not only fuels adventure but also brings attention to the rich biodiversity and cultural heritage of the Himalayas.

Ultimately, whether or not the Yeti is ever found, its story is a testament to the human spirit's quest for discovery and understanding of the natural world.

A Final Peek at the Mystical Yeti

Diving into the world of the Yeti has been nothing short of an adventure. We've uncovered 29 fascinating facts about this elusive creature, each adding a layer to its enigmatic existence. From its deep roots in Himalayan folklore to the intriguing evidence that keeps the scientific community on its toes, the Yeti remains a captivating subject. Whether it's the allure of the unknown or the thrill of the hunt that draws you in, one thing's for sure: the Yeti continues to hold a special place in the realm of cryptids. As we close this chapter, remember, the Yeti isn't just a tale of myth and mystery; it's a testament to humanity's enduring fascination with the wonders of our world. So, keep your eyes peeled and your mind open – who knows what discoveries lie just around the corner?

Frequently Asked Questions

Was this page helpful.

Our commitment to delivering trustworthy and engaging content is at the heart of what we do. Each fact on our site is contributed by real users like you, bringing a wealth of diverse insights and information. To ensure the highest standards of accuracy and reliability, our dedicated editors meticulously review each submission. This process guarantees that the facts we share are not only fascinating but also credible. Trust in our commitment to quality and authenticity as you explore and learn with us.

Share this Fact:

- YETI Holdings-stock

- News for YETI Holdings

Buy Rating on Yeti Holdings: Strategic Product Expansion and Attractive Valuation

In a report released yesterday, Randal Konik from Jefferies maintained a Buy rating on Yeti Holdings ( YETI – Research Report ), with a price target of $54.00 .

Randal Konik has given his Buy rating due to a combination of factors surrounding Yeti Holdings’s recent product developments and the company’s strategic positioning. Konik notes Yeti’s successful product launch cycle, exemplified by the release of the ROADIE 15 cooler, as a key driver for growth. The company has consistently leveraged its ability to expand product colorways and sizes, which enhances customer engagement and drives incremental sales. This approach not only broadens the appeal of Yeti’s existing product lines but also reinforces the brand’s competitive edge while it continues to diversify its product offerings into new market segments such as barware, culinary items, and luggage.