- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Business Education

- Business Law

- Business Policy and Strategy

- Entrepreneurship

- Human Resource Management

- Information Systems

- International Business

- Negotiations and Bargaining

- Operations Management

- Organization Theory

- Organizational Behavior

- Problem Solving and Creativity

- Research Methods

- Social Issues

- Technology and Innovation Management

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Sexual harassment in the workplace.

- Rose L. Siuta Rose L. Siuta Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Texas A&M University

- and Mindy E. Bergman Mindy E. Bergman Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Texas A&M University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.191

- Published online: 25 June 2019

Business and management conceptualizations of sexual harassment have been informed by both legal and psychological definitions. From the psychological perspective, sexual harassment behaviors include harassment based on one’s gender, enacting unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. The most recent psychological theories of sexual harassment acknowledge that it is a gendered experience motivated by the societal stratification of gender and not by sexual gratification.

Harassing behaviors negatively impact individual well-being. Well-documented workplace effects of sexual harassment include reduced job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and productivity, and increased job stress, turnover, withdrawal, and conflict. Sexual harassment negatively affects target’s psychological and physical well-being, including increases in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety symptoms, emotional exhaustion, headaches, sleep problems, gastric distress, and upper respiratory problems. All of these individual-level effects can result in financial decrements for the target and the organization.

Both individual and organizational factors predict sexual harassment. Women are more likely to experience sexual harassment, as well as minoritized persons, with women who embody more than one minority identity being the most likely to experience sexual harassment. This finding supports the interpretation of sexual harassment as motivated by reinforcing societal power hierarchies. Other individual factors such as sexual orientation, age, education level, and marital status are also related to experiencing sexual harassment. At the organizational level, organizational climate, job-gender context, and relative power between the harasser and the target predict sexual harassment. Organizational climates that are more tolerant of sexual harassment produce more sexual harassment. In addition, as masculinity of a work context increases, so does sexual harassment for women. Lastly, those with lower organizational power are more likely to experience sexual harassment, particularly by people with higher levels of power; however, contrapower harassment (harassment of individuals with higher organizational power by those with lower organizational power) can also occur.

Reporting harassment to organizational authorities has been theorized to lead to positive outcomes, but reporting rates are low. This may reflect findings that procedures for reporting are often unclear and that reporting often leads to worse outcomes for targets of harassment than their non-reporting peers.

The two most common approaches to measuring sexual harassment are direct query (explicitly ask about sexual harassment) or behavior experiences (ask respondents about how many sexually harassing behaviors they have experienced). A few considerations for the methodology used in these studies include inconsistency in conceptual or operational definitions of sexual harassment, the framing of a study, the retrospective nature of research asking about past experiences, and the sampling methodology used. A number of gaps remain in the documentation and understanding of sexual harassment phenomena, which intersect with some research practices and challenges. These include (a) the need to take into account factors other than incidence rates, such as perceived severity of experiences; (b) further examination of how multiple minority statuses and intersectional oppression affect harassment; (c) the importance of conducting research on harassment perpetrators; and (d) the examination of culturally informed topics related to sexual harassment, particularly outside Western countries.

- sexual harassment

- organizational climate

- job-gender context

- methodology

Introduction

Sexual harassment is a form of sex-based abuse that happens in the workplace (Berdahl, 2007a ; Fitzgerald, 1993 ; Gutek & Koss, 1993 ). It also happens in schools and other institutions, but because of the nature of this encyclopedia, this review focuses on the workplace. This article focuses primarily on the psychological, rather than the legal, definitions of sexual harassment because the psychological conceptualization of sexual harassment is the same across jurisdictions, time, court decisions, and legislation, but the legal definition is not. Additionally, this article focuses on the psychological conceptualization, because harm to employees and their organizations can occur even when harassing experiences do not rise to the level of a legal standard for harassment. In light of the recent rise of the #MeToo movement (a social media phenomenon whereby a surge of people used social media to acknowledge experiences with sexual harassment following claims levied against prominent figures in Hollywood and business), attention to sexual harassment has become even more urgent in organizational contexts. Results of a meta-analytic study of the workplace sexual harassment literature reveal that approximately 58% of women have experienced sexual harassment (Ilies, Hauserman, Schwochau, & Stibal, 2003 ). In the United States, the prevalence of workplace experiences of sexual harassment is 41% for women and 32% for men (Das, 2009 ). Similar rates have been found in Europe and Australia (AHRC, 2012 ; Latcheva, 2017 ), with 33% of women in Australia and 45–55% of women in Europe experiencing harassment at least once in their lives. Within Europe, women in Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden reported higher prevalence rates (71–81%) than those in Bulgaria, Poland, Portugal, and Romania (24–32%) (Latcheva, 2017 ). Incidence rates of sexual harassment are lower in Eastern nations like China (12.5%; Parish, Das, & Laumann, 2006 ) and Japan (9.5%; Chen et al., 2008 ) than those of Western nation counterparts. Meanwhile, one study on educational contexts in Ethiopia found similar prevalence rates to Western nations (Marsh et al., 2009 ). Thus, it is clear that sexual harassment is a worldwide and common experience.

What Is Sexual Harassment?

In the United States, sexual harassment law is informed by both legislation (e.g., Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 ) and case law (e.g., Burlington v. Ellerth , 2000 ; Faragher v. Boca Raton , 2000 ; Meritor v. Vinson , 1979 ; Oncale v. Sundowner , 1998 ). As new legislation is enacted and court cases accumulate, the parameters change regarding how sexual harassment is defined, what evidence is necessary to support a charge of sexual harassment, and who can be held liable for substantiated claims. Sexual harassment law has long recognized that there are two distinct types or components to sexual harassment: quid pro quo and hostile environment harassment. Quid pro quo harassment, which translates to “this for that,” is the notion that someone’s employment, promotions, compensation, or other terms and conditions of employment are dependent upon submitting to sexual requests or by providing sexual favors. Hostile environment harassment occurs when there is pervasive unwanted sexual attention, gendered and sexualized jokes, and comments, and other behaviors occurring in the organization; it’s as though harassment is “in the air.”

Other countries have different laws and guidance. For example, although each European Union (EU) member country has its own specific law regarding sexual harassment, EU member nations are guided by Directive 2006 /54/EC, which focuses on equal treatment of women and men in the workplace. This Directive states, “Harassment and sexual harassment are contrary to the principle of equal treatment between men and women and constitute discrimination on grounds of sex.” This Directive indicates that both harassment and sexual harassment are designed to intimidate, degrade, offend, or humiliate people, but differ in their content, whereby sexual harassment specifically has sexualized content, whereas harassment is treatment based on sex. Pakistan has two laws that prohibit sexual harassment: section 509 of the Pakistan Criminal Penal Code (a criminal law) and the Protection Against Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act of 2010 (a civil law; Jatoi, 2018 ). In New Zealand, harassment is also covered by two separate laws: the Employment Relations Act 2000 and the Human Rights Act 1993 ; these differ in the timelines for filing a complaint and how (Employment New Zealand, 2018 ). Japan’s legal precedent against sexual harassment began in 1992 following a successful suit whereby a publishing company and one of its employees were found responsible for crude remarks toward a woman, who was driven to quit her job from the negative experience (Huen, 2007 ; Weisman, 1992 ); statutes prohibiting sexual harassment appeared in Japan in 1997 (Huen, 2007 ). Thus, it is clear that there are numerous and varied laws and timelines regarding the prohibition of sexual harassment across the world.

The predominant psychological model of sexual harassment in the workplace was proposed by Fitzgerald, Hulin, and Drasgow ( 1995 ; Gelfand, Fitzgerald, & Drasgow, 1995 ). They argued that sexual harassment is composed of a set of interrelated domains of behavior. These include gender harassment (later split into sexual hostility and sexist hostility; Fitzgerald, Magley, Drasgow, & Waldo, 1999 ; Hay & Elig, 1999 ), unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. Sexist hostility refers to comments and behaviors that indicate that one sex (e.g., females) is worse than the other (e.g., males) in some way, such as being unsuited for some jobs, less intelligent, or humorless. Sexual hostility includes comments and behaviors that have a sexualized component and are demeaning to a group of people (e.g., women) or to an individual person; examples include comments about or attempts to draw a person into discussions about their personal sexual experiences, catcalls, sexual “jokes” or stories, ogling, exhibitionist or exposure behaviors, and sexual gestures. Unwanted sexual attention is behaviors that focus sexualized attention on a person, including unwanted touching (e.g., pats on the buttocks, massaging the shoulders, brushing up against someone), repeated requests for dates, and exposure to pornographic materials; unwanted sexual attention also includes rape and attempted rape. Sexual coercion is behaviors in which one person indicates that the terms and conditions of employment for another person are dependent complying with sexual requests, whether it is engaging in sexual behavior or submitting to sexualized comments and jokes. Fitzgerald et al.’s concepts map onto the legal concepts of harassment, with sexual coercion parallel to quid pro quo harassment and sexist hostility, sexual hostility, and unwanted sexual attention aligning with hostile environment harassment (Fitzgerald, Gelfand, & Drasgow, 1995 ).

Berdahl ( 2007a ) proposed that sexual harassment be reframed and renamed as “sex-based harassment” to emphasize that sexual harassment is not about sexual relationships gone awry, but rather the sex-based social power hierarchies that exist within organizations and the broader societies in which they are embedded. This is critical because it explains (a) why there are differential patterns in who harasses whom (e.g., why men are more likely to harass women than vice versa), (b) why “uppity” (Berdahl, 2007b ; Berdahl & Moore, 2006 ) and other “unattractive” or unconventional women are harassed, and (c) why some men are harassed and which ones are most likely to be harassed (Berdahl, Magley, & Waldo, 1996 ; Fitzgerald & Cortina, 2017 ; Holland et al., 2016 ; Stockdale, Visio, & Batra, 1999 ). This perspective pushes back against the notion that sexual harassment is about sex and attraction and instead purports that it is about power and its preservation. Sexual harassment is a way to maintain power and status; it is a tool to suppress the advancement of women and others who might challenge the power, resources, and status that are held by the people at higher and the highest levels of the sex-based social hierarchy (Maass, Cadinu, Guarnieri, & Grasselli, 2003 ). In essence, lowering another person’s sex-based status is a mechanism for bolstering one’s own sex-based status. Berdahl ( 2007a ) notes that in the United States, the highest levels of the sex-based social hierarchy are occupied by cis, white, hetero, Christian, strong, smart, handsome, “manly” men. To the extent that people deviate from this standard and that they challenge the positions that are held by these men increases their likelihood of being harassed.

Fitzgerald and Cortina ( 2017 ), however, argue that sexual harassment is primarily a women’s issue because sexual harassment primarily occurs toward women. Additionally, they note that while Berdahl’s ( 2007a ) perspective is useful, men are harassed because the harasser perceives them to be “not man enough,” and the harassment that they receive often includes taunts and other behaviors that highlight that they are not “manly.”

It is clear from these recent developments that sexual harassment must be discussed within the context of the social stratification of gender that permits it. Early explanations of sexual harassment defined it as emerging from desire for sexual gratification (for reviews, see Berdahl, 2007a ; Lengnick-Hall, 1995 ; Welsh, 1999 ). Models of sexual harassment then focused on the normative permissiveness toward sexual harassment behaviors, the wide variety of behaviors—including non-sexual behaviors—that sexual harassment encompassed, and the individual and organizational fallout for sexual harassment in the workplace (Fitzgerald et al., 1995 ). Now theories of harassment have evolved to recognize that the gendered nature of sexual harassment is critical to our understanding of it (Berdahl, 2007a ; Fitzgerald & Cortina, 2017 ). In sum, views of sexual harassment have increasingly moved toward an analysis of its motivations as they relate to the social stratification of gender in a larger context and in the specific organizational context, as opposed to a focus on motivations stemming from sexual gratification.

Sexual Harassment as a Psychological Stressor

Fitzgerald et al. ( 1995 ) proposed an “integrated model of sexual harassment.” Their model integrated several psychological perspectives and literatures, including work from the fields of industrial-organizational psychology, clinical psychology, social psychology, violence, trauma, and law and psychology. Most notably, their work framed sexual harassment as a psychological stressor. Their work drew in particular on the transactional model of stress (Folkman, Lazarus, Gruen, & deLongis, 1986 ; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 ). Like other models of stress, the transactional model of stress indicates that stressors are events that tax an individual’s resources and require some action to restore the balance of resources the person had before the event. Further, the model recognizes that stressors can be psychosocial (i.e., occurring in interpersonal relationships and interactions). The transactional model of stress also proposes that the extent to which stressors affect people depends on their primary and secondary appraisals of the event. Primary appraisal is the assessment of how threatening the event is to the person’s well-being, identity, or other important life factor; secondary appraisal is the assessment of what coping resources a person has to remediate the situation. Although they are named “primary” and “secondary” appraisal, it is not the case that primary always and only precedes secondary appraisal. For example, the realization that a person lacks any coping resources (secondary appraisal) to deal with the situation could make it more threatening to the person (primary appraisal).

One reason why this particular model of stress was adopted over other models of stress appears to be that the concepts of primary and secondary appraisal helped explain why similar sex-based behaviors could elicit different responses from different people. For example, a salacious joke told to a group of people could be seen as threatening to Person A and non-threatening or even funny to Person B. Similarly, Person A could perceive a salacious joke told by Person C as threatening and a similar joke told by Person D as non-threatening. Primary and secondary appraisal help explain why this can occur. The context of these jokes, the people who tell them, and the people who hear them change the dynamics of power and subsequent threat. Fitzgerald et al. ( 1995 ) acknowledged this in their model by theorizing personal vulnerability factors that affect the relationship between sexual harassment and job-, psychological-, and health-related outcomes.

However, this perspective also bolstered the “whiner hypothesis” (Magley, Hulin, Fitzgerald, & DeNardo, 1999a ), which argued that women overreact to sex-based workplace experiences. That is, the inclusion of appraisal in Fitzgerald et al.’s ( 1995 ) model of sexual harassment indicates that there is a subjective component to understanding harassment, but the “whiner hypothesis” over-interprets that component to indicate that most harassment is subjective overreaction to harmless behavior. However, research shows that regardless of whether women label their experiences as harassment, they are harmed by harassing behaviors; the whiner hypothesis has been thoroughly debunked (Bergman & Henning, 2008 ; Ilies et al., 2003 ; Magley et al., 1999a ; McDonald, 2012 ; Welsh, 1999 ). Further, there is burgeoning evidence that personal vulnerability factors are as important or more important in identifying why some people are targeted for harassment compared to explaining why some people are more harmed by harassment (Bergman & Henning, 2008 ; Settles, Buchanan, & Colar, 2012 ).

One of the hallmarks of stressors is the negative effect that they have on individual well-being. The next section reports these findings.

Outcomes of Harassment

Research consistently shows that sexual harassment has a negative effect on target well-being, whether psychological, job related, or health related outcomes. In the following, several key effects are highlighted.

Job Outcomes

Sexual harassment negatively affects targets’ job-related well-being. The negative effect of sexual harassment on job satisfaction is well documented in the United States and around the world (Fitzgerald et al., 1997 ; Hutagalung, & Ishak, 2012 ; Malik, Malik, Qureshi, & Atta, 2014 ; Merkin & Shah, 2014 ; Nielsen, Bjørkelo, Notelaers, & Einarsen, 2010 ; Sojo, Wood, & Genat, 2016 ; Wasti, Bergman, Glomb, & Drasgow, 2000 ; Willness, Steel, & Lee, 2007 ). Through meta-analysis, Willness et al. ( 2007 ) demonstrated that sexual harassment negatively affects all forms of workplace satisfaction, with slightly stronger negative effects on satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of work (i.e., co-worker and supervisor satisfaction) compared to satisfaction with the work itself. Beyond job satisfaction, sexual harassment has effects on a number of work-related outcomes, including job stress (Cortina, Fitzgerald, & Drasgow, 2002 ; Lim & Cortina, 2005 ) and organizational commitment (Willness et al., 2007 ).

Sexual harassment has also been negatively linked to a variety of aspects of job performance and turnover (Barling, Rogers, & Kelloway, 2001 ; Liu, Kwan, & Chiu, 2014 ; Magley, Waldo, Drasgow, & Fitzgerald, 1999b ; Raver & Gelfand, 2005 ; Woodzicka & LaFrance, 2005 ). Because both job satisfaction and organizational commitment predict turnover (Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, 2000 ; Mathieu, Fabi, Lacoursière, & Raymond, 2016 ; Meyer, Stanley, Hercovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002 ; Riketta, 2002 ) and both are negatively impacted by sexual harassment, this suggests that experiencing sexual harassment will predict turnover as well. Furthermore, people who are sexually harassed are more likely to turn over than people who are not (Sims, Drasgow, & Fitzgerald, 2005 ). Because harassment can prompt turnover, it can increase financial strain for targets and also damage their ongoing career prospects (McLaughlin, Uggen, & Blackstone, 2017 ). In addition, Willness et al. ( 2007 ) showed a positive relationship between sexual harassment and organizational withdrawal, including avoiding work, missing work, and neglecting to complete job tasks. Gruber ( 2003 ) found that sexual harassment is more likely to result in its targets avoiding work than any other type of outcome, including actual turnover (Willness et al., 2007 ).

The effects of sexual harassment are not limited to just the target of the harassment, but can also spread to other members and areas within the organization. These effects are exemplified by decreased job satisfaction, increased conflict within teams, and increased turnover and withdrawal behaviors that show that when there is an increase in sexual harassment, there is also a decrease in workgroup productivity (Willness et al., 2007 ). Parker and Griffin ( 2002 ) demonstrated that sexual harassment is positively related to conflict within teams and impairment of relationships between team members, which translates to a decrease in team financial performance. In addition to effects of one person’s harassment experiences on team functioning, knowledge of harassment and harassment climate also negatively affect employees and workplaces. Witnessing sexual harassment negatively affects the job satisfaction of the bystander (Dionisi & Barling, 2018 ; Glomb et al., 1997 ; Richman-Hirsch & Glomb, 2002 ). Further, organizational climates that are tolerant of sexual harassment are negatively linked to job satisfaction (Fitzgerald, Drasgow, & Magley, 1999 ).

Health Outcomes

Experiencing sexual harassment has also been linked to a variety of negative health outcomes for the target—both mental and physical (Fitzgerald et al., 1997 ; Nielsen & Einarsen, 2012 ; Sojo et al., 2016 ; Willness et al., 2007 ). Further, Dionisi, Barling, and Dupré ( 2012 ) found that the negative effect on psychological well-being is stronger for threatened and real physical contact forms of sexual harassment than for other types of workplace mistreatment. For women targets, symptoms of PTSD are positively correlated and general psychological well-being is negatively correlated with sexual harassment (Schneider, Swan, & Fitzgerald, 1997 ). Willness et al.’s ( 2007 ) meta-analysis demonstrated that symptoms of PTSD were positively correlated with experiences of sexual harassment. Symptoms of depression and anxiety are also positively correlated with exposure to sexual harassment (Ho, Dinh, Bellefontaine, & Irving, 2012 ; Nielsen & Einarsen, 2012 ). When observing medical diagnoses received by plaintiffs in harassment trials, major depressive disorder and PTSD were the most common mental health symptoms reported (Fitzgerald et al., 1999 ).

Sexual harassment is also linked to alcohol abuse and the risk of eating disorders (Harned & Fitzgerald, 2002 ; Rospenda, Fujshiro, Shannon, & Richman, 2008 ). Schneider, Tomaka, and Palacios ( 2001 ) found that cardiovascular activity increased even after mild experiences of gender harassment. Additionally, there is a positive relationship between experiencing sexual harassment and various psychosomatic symptoms. These include an increase in the experience of headaches, sleep problems, gastric distress, and upper respiratory infections (Barling et al., 1996 ). In addition to physical health problems, those who experience sexual harassment are also more likely to experience emotional exhaustion (de Haas, Timmerman, & Höing, 2009 ). Taken in conjunction, these findings show that sexual harassment has effects on multiple aspects of a target’s life, including job effects, psychological effects, and physical health effects.

Predictors of Harassment

In this section, individual and organizational predictors of sexual harassment are reviewed. These findings are important because they highlight both the individual characteristics that make one more likely to be targeted with sexual harassment, as well as the organizational characteristics that can leave individuals more vulnerable to these experiences. Organizations would benefit from understanding the intersections of individual- and organizational-level predictors to prevent sexual harassment and minimize the harmful effects on targets and co-workers. This would allow more proactive attempts to prevent harassment rather than reactively respond via legal compliance routes.

Target Characteristics Associated With Sexual Harassment

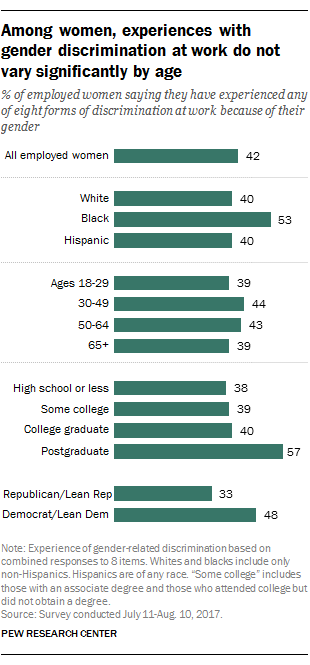

One of the enduring findings in the sexual harassment literature is that women are more likely to experience sexual harassment than men (Foster & Fullagar, 2018 ; Ilies et al., 2003 ; U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, 1981 , 1988 , 1994 ). This is consistent with theories of power in sexual harassment (e.g., Berdahl, 2007a ) as well as theories of intersectional oppression (e.g., Crenshaw, 1989 ). Additionally, intersectionality theory suggests that occupying more than one minoritized 1 category can have a multiplicative effect on sexual harassment (Crenshaw, 1989 ). Generally, intersectionality theories examine how demographic identity markers are inextricably linked because systems of oppression (e.g., racism, sexism) are inextricably linked as ways to uphold the society’s hegemonic power structure. The consequence for sexual harassment research is that a target’s risk for and rates of sexual harassment are likely to increase as the number of minoritized identities increase. One example of this effect is evident in research showing that racially/ethnically minoritized women experience more harassment than white women, white men, or racially/ethnically minoritized men (Berdahl & Moore, 2006 ). Racially and ethnically minoritized women are also more likely to be employed in positions that are lower status and with less organizational power (Bayard, Hellerstein, Neumark, & Troske, 2003 ; Maume, 1999 ), which may leave them vulnerable to the effects of power differences on sexual harassment discussed in the following section. Similarly, women are particularly at risk for experiencing sexual harassment when they come from backgrounds with low sociocultural power (Harned et al., 2002 ). In their theory, Fitzgerald et al. ( 1995 ) highlighted low economic power as a likely strong predictor of sexual harassment and its negative effects (i.e., as a moderator of the sexual harassment–outcome relationship) because people with low economic power have little opportunity to leave their current job for another.

Race and ethnicity also predict experiences of sexual harassment. Bergman and Drasgow ( 2003 ) found that among U.S. military women, the frequency of experiences of sexual harassment differed depending on race, with Native American women reporting the most harassment, Hispanic and black women reporting the next most frequent amount of harassment, followed by Asian women, and with white women indicating the fewest instances of harassment. Similarly, among men in the U.S. military, black men report more frequent experiences of sexual harassment than white men (Settles et al., 2012 ). Additionally, racial/ethnic minoritized persons experience an additional type of sexual harassment, racialized sexual harassment, that reflects both their sex status and their race status (Buchanan, 2005 ; Buchanan & Ormerod, 2002 ; Welsh, Carr, MacQuarrie, & Huntley, 2006 ).

LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) persons are also likely to experience sexual harassment, and in particular to experience a specific form of sexual harassment, sexual orientation harassment, whereby unwanted behaviors are exhibited toward an individual because of their perceived sexual orientation (Ryan & Wessel, 2012 ). This harassment can take the form of direct unwanted expressions or actions, or can come from ambient expressions of hostility toward sexual minorities in the workplace climate. Because sexual orientation can remain a hidden identity in comparison to more outwardly visible determinants of minoritized status, such as race or gender, these individuals may be especially prone to experiencing sexual orientation harassment in its more ambient form. Like other demographic risk factors, sexual orientation–based sexual harassment reflects threats to the sex-based societal power structure (Berdahl, 2007a ). Similarly, men experience a type of sexual harassment, “not man enough” harassment, which is deployed when men violate gender norms (Berdahl et al., 1996 ; Funk & Werhun, 2011 ); this idea has been expanded into “gender policing harassment” in order to encapsulate women’s experiences and an LGBTQ person’s harassment experiences based on perceived violations of gender norms (Konik & Cortina, 2008 ). As a summary statement, people who violate gender norms are more likely to experience sexual harassment (Berdahl, 2007a , 2007b ; Konik & Cortina, 2008 ).

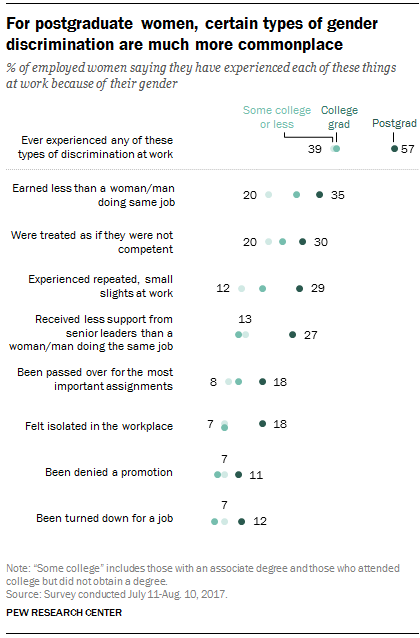

Age, education level, and marital status have also been linked to sexual harassment. Younger people are more likely to experience sexual harassment than their older counterparts (Fain & Anderton, 1987 ). Those who are younger are also more likely to occupy lower positions in organizations and hold less sociocultural power when compared to their older counterparts. Additionally, those who have attained a lower education level are also less likely to hold higher positions in organizations. Individuals with lower education levels are similarly more likely to experience sexual harassment (Fain & Anderton, 1987 ). Lastly, those who are married are less vulnerable to sexual harassment than their single counterparts (Fain & Anderton, 1987 ). Each of these factors might be a proxy for the economic dependence on their current job (Fitzgerald et al., 1995 ).

Organizational-Level Predictors of Harassment

At the organizational level, three major facilitating conditions of sexual harassment have been identified: organizational climate, job-gender context, and relative power between the harasser and the target. Organizational climate is the extent to which the workplace tolerates sexual harassment (Hulin, Fitzgerald, & Drasgow, 1996 ). Job-gender context reflects the gendered nature of a particular job, including the sex ratios within the workgroup, the sex of the supervisor, and the stereotypical gender associated with a job (e.g., surgeon vs. nurse; Gutek, 1985 ). Relative power is the extent to which one person occupies more powerful positions than the other.

There are numerous climates in organizations, corresponding to sets of expectations about particular components of organizational life; because of this, specific instantiations of climate are “climates for” components of the organization (Ostroff, Kinicki, & Muhammad, 2013 ). Organizational climate is generally conceptualized as the normative expectations of the contingencies regarding behaviors—what is rewarded and supported, or condemned and sanctioned (Ostroff et al., 2013 ). Organizational climate relevant to sexual harassment was originally conceptualized and operationalized as organizational tolerance for sexual harassment (Hulin et al., 1996 ), but often is referred to as “organizational climate” or “climate toward harassment.” Regardless of the particular label or measure used, organizational climate in the context of sexual harassment reflects the extent to which sexual harassment is rewarded, supported, or sanctioned in the organization. It reflects the normative expectations of whether sexual harassment is tolerated.

The second major organizational predictor of sexual harassment is job-gendered context (Gutek, 1985 ). This is the extent to which a job is gendered as masculine or feminine. Gender is an integral part of defining power structures within organizations, which includes divisions of organizational power along gender lines, images which reinforce gender stereotypes, male dominance in social interactions, gendered individual identities, and the underlying creation of gendered organizational structures (Acker, 1990 ). Job-gender context includes both the local context and the occupational history and stereotypes. Job-gendered context is often operationalized with assessments of (a) the sex of the supervisor for the position, (b) the local sex ratio of the people in the position and the co-workers attached to it, and (c) the gendered stereotype associated with the job (Fitzgerald et al., 1997 ). Results indicate that women in more masculine jobs (i.e., those that have a man as a supervisor, have more men than women as co-workers, and/or where the job is more associated with men than with women) are more likely to experience sexual harassment (Bergman et al., 2002 ; Fitzgerald et al., 1997 ). This is consistent with Berdahl’s ( 2007a , 2007b ) argument that women who are perceived to be interlopers in male spaces are more likely to be harassed.

The organizational power difference between the target and the harasser is also a factor in experiences of sexual harassment. Not only is occupying positions of lower organizational power associated with a greater risk of sexual harassment for women than for those who occupy positions of higher organizational power (Harned et al., 2002 ), but the power difference between the target and harasser matters as well (Bergman et al., 2002 ). However, it should be noted that relative organizational power is only one marker of the power differential between harasser and target. Contrapower harassment also occurs, such that persons with higher organizational power but lower social power on other aspects experience harassment from persons with lower organizational power but higher social power (Rospenda, Richman, & Nawyn, 1998 ).

Reporting Sexual Harassment

There is considerable interest in the formal reporting of sexual harassment to organizational authorities because reporting is theorized to have significant benefit to both the target of harassment and to the broader organization. Although people indicate in vignette studies that they are likely to confront or report their harassers (see Woodzicka & LaFrance, 2001 , for a review), studies of people in real (rather than “thought experiment,” vignette, or “paper people” studies of harassing situations) indicate otherwise (Bergman at al., 2002 ; Brooks & Perot, 1991 ; Culbertson & Rosenfeld, 1994 ; Firestone & Harris, 2003 ). Note that people can report experiencing sexually harassing behavior even if they do not label it as sexual harassment (Bergman et al., 2002 ).

The low rates of reporting are surprising when considering the theorized positive outcomes of reporting harassment (Bergman et al., 2002 ). Following a report, the harassing behavior should end, which should result in some—although not necessarily full—recovery from the stress resulting from the harassment (Munson, Hulin, & Drasgow, 2000 ). Additionally, reports should provide the opportunity for organizations to identify problematic employees and either sanction them or remove them from the organization; it should also buffer the organization from liability because the organization should respond appropriately (Bergman et al., 2002 ). However, research indicates that despite the putative goals of reporting, people do not benefit from the reporting experience compared to their non-reporting peers; oftentimes, reporters are actually worse off than if they had never reported (Adams-Roy & Barling, 1998 ; Bergman et al., 2002 ; Brooks & Perot, 1991 ; Firestone & Harris, 2003 ; Fitzgerald, Swan, & Fischer, 1995 ; Gruber & Smith, 1995 ; Hotelling, 1991 ; Malamut & Offermann, 2001 ).

The deficits in well-being from reporting are likely due to unclear procedures and negative consequences associated with reporting sexual harassment. Across a number of studies, targets of sexual harassment claimed that the reasons they chose not to report the harassment were due to concerns regarding the definition of harassment, the work environment not being conducive to reporting, questions of what would happen to their job status, and fear of other organizational and personal consequences (Adams-Roy & Barling, 1998 ; Bergman et al., 2002 ; Brooks & Perot, 1991 ; Fitzgerald et al., 1995 ; Gruber & Smith, 1995 ; Hesson-McInnis & Fitzgerald, 1997 ; Hotelling, 1991 ; Malamut & Offermann, 2001 ).

Organizational factors also influence sexual harassment reporting. Notably, organizational climate influences reporting, such that if people perceive others to be accepting of harassment, then they are less likely to report (Bergman et al., 2002 ; Halbesleben, 2009 ; Offermann & Malamut, 2002 ). Additionally, leaders’ views of harassment play a role, such that leaders who are anti-harassment are more likely to have subordinates who report harassment (Offermann & Malamut, 2002 ). Organizational factors appear to be so important that Bergman et al. ( 2002 ) noted that a climate intolerant of harassment is essential because it (a) reduces the harassment in the organization, (b) increases the likelihood of reporting when it does occur, and (c) increases the likelihood that organizations will respond appropriately to those reports.

Organizational Responses to Reporting

When targets of harassment report their experiences to the organization, the organization can make any number of responses (Knapp, Faley, Ekeberg, & DuBois, 1997 ). First is investigation; organizations can intake the report and deploy human resources representatives to investigate to determine whether organizational rules have been broken (Pustolka, 2015 ; Trotter & Zacur, 2012 ). There has been surprisingly little research on sexual harassment investigations. One recent study, however, demonstrates that organizational tolerance for sexual harassment suppresses both learning of sexual harassment investigation skills and the motivation to learn these skills (Goldberg, Perry, & Rawski, 2018 ).

Note, however, that organizations are not required to investigate sexual harassment allegations. It is possible that their policies do not require it (Pustolka, 2015 ). Additionally, the process is a human process, prone to the cognitive errors and biases of human decision makers. Thus, a different response is minimization: organizational representatives could encourage the reporter to drop the complaint or could respond that the complaint is not serious enough to warrant an investigation (Bergman et al., 2002 ). This minimization could happen at the time of the report, making an investigation unlikely to occur, or it could happen during (e.g., through investigator behavior) or after the investigation. In the latter case, it is possible that the report is unsubstantiated, so the reporter has the experience that the complaint was minimized when in actuality the complaint did not meet the standards for concern within the organization. Organizations that are more tolerant of sexual harassment are more likely to use minimization (Bergman et al., 2002 ). Additionally, as the perpetrators’ rank in the organization increases, the use of minimization also increases (Bergman et al., 2002 ).

Organizations could also retaliate against the reporter (Bergman et al., 2002 ). This could again happen at the time of the complaint or during or following an investigation. Retaliation can occur both formally (e.g., reassignment to a different unit in the organization) or informally (e.g., hostile treatment from co-workers; Bergman et al., 2002 ). Unsurprisingly, like the finding for minimization, retaliation is more common when organizations are more tolerant of sexual harassment and when the perpetrator’s rank is higher (Bergman et al., 2002 ).

Organizations can also make positive responses to the report, notably remediation (Bergman et al., 2002 ). Organizational remedies are actions taken against the perpetrator, including informal discussions about behavior, formal notes in employment files, reassignment to other work units or positions, and terminating the employment relationship. Remedies are more common when organizations are less tolerant of sexual harassment and when the perpetrator is lower in organizational rank (Bergman et al., 2002 ). Despite the positive response of organizational remedies, it has less effect on procedural satisfaction with the reporting process than do either retaliation or minimization (Bergman et al., 2002 ). It seems, then, that it is as important—if not more so—to reduce negative responses to sexual harassment reports than to increase positive responses.

At best, reporting sexual harassment does not make things worse for the reporter, but unfortunately it often does; there is no evidence to indicate that reporting actually improves well-being or job attitudes (Adams-Roy & Barling, 1998 ; Bell, Street, & Stafford, 2014 ; Bergman et al., 2002 ; Brooks & Perot, 1991 ; Firestone & Harris, 2003 ; Hesson-McInnis & Fitzgerald, 1997 ; Malamut & Offermann, 2001 ). Following a report of sexual harassment, people are affected by whether the harassment has been adequately addressed. For instance, if it is perceived that the harassment has been addressed, targets of sexual harassment are likely to have fewer symptoms of PTSD and depression and better well-being and post-harassment functioning (Bell et al., 2014 ). Therefore, it is not simply reporting harassment that can improve well-being for the target of sexual harassment, but the target’s perceptions and satisfaction with the reporting process (Bergman et al., 2002 ).

Sexual harassment research spans the methodological spectrum, including qualitative (Good & Cooper, 2014 ), experimental (Bursik, 1992 ; Burgess & Borgida, 1997 ; Pryor, 1987 ), historical (Segrave, 1994 ), legal (Conte, 2010 ), and quantitative methods. Because this review focuses primarily on the psychological aspects of sexual harassment in the workplace, quantitative methods common to psychological research, particularly surveys, predominate. The use of quantitative survey methods leads to queries about two key issues: measurement of sexual harassment and survey construction. Although psychological research in general and the study of sexual harassment in particular use experiments, within the sexual harassment literature these experiments are nearly uniformly vignette studies or “paper people” and do not align well with the lived experiences of sexual harassment targets. (For an exception, see Pryor, 1987 , for an experiment in which sexually harassing behaviors were induced in a laboratory setting.)

Measurement of Sexual Harassment

There are two primary ways of measuring sexual harassment (Culbertson & Rosenfeld, 1993 ): direct query and behavioral experiences. In the direct query method, people are only counted as having experienced sexual harassment if they respond affirmatively to an item such as “Have you been sexually harassed at work?” With the behavioral experiences method, participants indicate which of a list of behaviors they have experienced; they are counted as having been sexually harassed through their responses (i.e., greater than zero). The behavioral experience methods count a person as harassed even if the person does not label it as such (i.e., says “no” to a direct query item).

Considering the differences in methods, it is not surprising that the behavioral experiences approach results in counting more people as harassed than does the direct query method (Ilies et al., 2003 ). Interestingly, both the direct query and behavioral experiences approach result in similar relationships between sexual harassment and a variety of outcomes (Sojo et al., 2016 ). Within the behavioral experiences approach, the predominant measure of sexual harassment is the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (Fitzgerald et al., 1995 ; Fitzgerald et al., 1999 ). However, although it is the most commonly used behavioral experiences measure, there seems to be little substantive difference between using the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire and other behavioral measures in the ability to predict outcomes (Willness et al., 2007 ; Sojo et al., 2016 ).

In commentaries on the sexual harassment literature, theorists point out that there is often inconsistency in the definitions of sexual harassment used across studies and in the behaviors included in the specific operationalizations of behavioral experiences measures (Arvey & Cavanaugh, 1995 ; Fitzgerald & Shullman, 1993 ; Lengnick-Hall, 1995 ; Nye, Brummel, & Drasgow, 2014 ; Timmerman & Bajema, 1999 ). These definitional differences likely produce some discrepancies in the sexual harassment literature, particularly regarding incidence and prevalence of sexual harassment experiences (Ilies et al., 2003 ). Incidence and prevalence rates are typically lower in studies using the direct query method as opposed to those using behavioral experiences methods (Ilies et al., 2003 ; Timmerman & Bajema, 1999 ).

Unsurprisingly, there is considerable debate regarding whether direct query or behavioral experiences methods provide the “true score” rate of sexual harassment. On the one hand, the direct query method asks people to indicate exactly what the researchers want to know: Has sexual harassment occurred? On the other hand, the direct query method is problematic because people often do not know the definition of sexual harassment, or they recognize that their experiences do not meet legal standards of harassment even though they are distressing (Fitzgerald & Shullman, 1993 ). Thus, despite the apparent simplicity of the direct query method, there is considerable room for interpretation (Lengnick-Hall, 1995 ). However, there are still opportunities for interpretation in behavioral experiences methods, such as when an item asks whether a person has heard “suggestive” or “offensive” jokes and stories (Ilies et al., 2003 ). This is considered by some to be a strength of the behavioral experiences approach, because it encourages respondents to ignore jokes and stories that were not offensive (Fitzgerald et al., 1995 ; Fitzgerald & Shullman, 1993 ). On the whole, it seems that the better practice is to use a well-validated behavioral experiences method and, when possible, to also include a direct query.

Beyond the measurement of the frequency of sexual harassment experiences, it is also important to investigate other aspects of sexually harassing behaviors. Arvey and Cavanaugh ( 1995 ), for example, suggested that measures of behavior severity should be taken into account. Consistent with this idea, Berdahl (Berdahl, 2007b ; Berdahl & Moore, 2006 ) incorporated a multiplier when using the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire that measured how bothersome each specific behavior (i.e., item) was, which was then used to create a weighted scale score for sexual harassment. Measures of primary appraisal (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 ) and other indicators of severity have also been used to either multiply or modify measures of sexual harassment (e.g., Bergman et al., 2002 ; Fitzgerald & Shullman, 1993 ; Langhout et al., 2005 ).

Survey Research on Sexual Harassment

Like most survey research, surveys on sexual harassment commonly ask respondents about retrospective accounts of sexual harassment. Oftentimes, researchers specify a length of time or specific markers (e.g., “since joining this organization”). This common practice is useful for narrowing the scope of research and being able to draw conclusions about a particular work environment. For example, an organization might design a survey to ask about sexual harassment in the last year at that organization, rather than lifetime experiences of sexual harassment (e.g., “Have you ever experienced sexual harassment?”) in order to assess the current state of sexual harassment prevalence within the organization. However, it is difficult to compare incidence and prevalence rates that use different time periods for sexual harassment (Timmerman & Bajema, 1999 ).

Additionally, the design of the survey is important to gain participation (Miner-Rubino & Jayaratne, 2011 ). Sexual harassment surveys can be off-putting to potential participants, reducing their likelihood in participating (Galesic & Tourangeau, 2007 ). This is especially concerning because those who choose not to respond to a survey on sexual harassment may be the people with the most severe or frequent experiences. The frame of a survey can include the survey title, topic, purpose, or sponsor. Each of these features may influence how people respond to a survey by providing an interpretive framework for the study and facilitating recall of events, and should therefore be considered carefully during survey creation (Galesic & Tourangeau, 2007 ).

Sexual harassment survey research is typically cross-sectional, meaning that all measurements are collected from participants at one specific point in time (i.e., both the “predictors” and the “outcomes” are in the same survey). Even though theory and evidence indicate the likely causal ordering of sexual harassment, its causes, and its consequences, cross-sectional surveys cannot provide evidence of causality (Cook, Campbell, & Shadish, 2002 ). Moreover, cross-sectional surveys are unable to document the lasting effects of sexual harassment on a person’s well-being (Munson et al., 2000 ). Longitudinal methodology, where measurements are collected from participants at multiple points in time, provides a rich resource of information concerning the evolution of these experiences (McDonald, 2012 ). As with any longitudinal research, there are challenges in longitudinal sexual harassment research (e.g., respondents not returning for Time 2, history effects). However, longitudinal approaches provide a closer approximation to causal studies than do cross-sectional studies (Cook et al., 2002 ).

Qualitative Research on Sexual Harassment

A full treatment of qualitative research, its wide variety of approaches, and their epistemological underpinnings is beyond the scope of this review. However, it is important to acknowledge that qualitative research can obtain a richer understanding of participant experiences than quantitative approaches (e.g., behavioral experience measures). One suggestion that may benefit researchers is using a mixed methods approach, where qualitative methods and quantitative methods supplement each other (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004 ; McDonald, 2012 ). Furthermore, when studying forms of sexual harassment that have received less empirical attention, it may be beneficial to use qualitative or ethnographic methods in order to better define these experiences and understand those who have been targets (Miner-Rubino & Jayaratne, 2011 ). In particular, examining the intersectional experiences of harassment targets (e.g., Buchanan, 2005 ; Buchanan & Ormerod, 2002 ) through qualitative methods might be useful. Qualitative research is also well suited to research questions that explore the role that sexual harassment plays in people’s life histories (McLaughlin et al., 2017 ). Although this could be accomplished in quantitative research, qualitative research allows people to tell their stories as they experienced them, rather than conform to the predetermined questions on a survey.

Sampling in Sexual Harassment Survey Research

Sampling methods used in sexual harassment research are another important consideration. Research on sampling methods has shown that random sampling may produce fewer reports of sexual harassment than when using non-random sampling (Timmerman & Bajema, 1999 ). In their meta-analysis, Ilies et al. ( 2003 ) found that non-probability sampling (compared to probability sampling) produced higher reports of sexual harassment when behavioral experiences methods were used, but lower reports of sexual harassment when direct query methods were used.

Concerns remain about using non-random sampling. Arvey and Cavanaugh’s ( 1995 ) evaluation of sexual harassment methodology highlighted the frequent use of convenience samples and the difficulty of low response rates. A primary concern of non-random sampling is possible selection bias, or the over-inclusion of people who have experienced sexual harassment relative to the population (Arvey & Cavanaugh, 1995 ; Timmerman & Bajema, 1999 ).

However, it is also important to consider why purposive sampling can be useful. In particular, the need to account for intersectional narratives of sexual harassment might require intentional over-inclusion of particular subgroups in a sample. As with research using other non-probability samples, research on sexual harassment should be cautious about drawing population-level conclusions when non-probability samples are used.

Research on Perpetrators of Harassment

Although the research on the experiences of targets of sexual harassment has proliferated, there is a notable paucity of studies on harassers themselves (Pina, Gannon, & Saunders, 2009 ). This is likely due to the difficulties associated with sampling perpetrators. To study sexual harassers, participants would have to admit to committing these offenses without fear of stigmatization or legal recourse. It would be unlikely to find a representative sample of these individuals who would be willing to answer these surveys honestly. Nevertheless, the experiences and motives of sexual harassers are needed facets of research in the literature. Particularly, for researchers interested in interventions, studying those who do the harassing may provide a rich source of information to further support theoretical models. The onus for behavioral change can then be placed on the perpetrators of these behaviors instead of on defensive strategies for targets.

Looking Forward: What More Do We Need to Know?

As reviewed here, it is clear that sexual harassment is common enough to be concerning to organizations. Additionally, it is damaging to targets’ well-being. Sexual harassment is also damaging to organizational productivity. Sexual harassment is a gendered experience. People who have more minoritized demographic markers are more likely to experience sexual harassment. Organizations that tolerate sexual harassment have more of it occurring and respond to reports of harassment in worse ways.

Even with all that is known about harassment, there are still many unknowns. One interesting avenue forward is local culture, outside the organization but more localized than a country. How do localized norms of behavior and gender norms influence the experience of sexual harassment? It is possible that these norms influence both the rate of sexual harassment and the types of harassment experienced. Additionally, the relative tolerance of sexual harassment in the organization and the context in which it is embedded (e.g., the industry, the local area) could influence organizational reputation, willingness to report, and other key factors for the organization. A key example of this is the “bro culture” of Silicon Valley start-ups compared with the gender equality in the same area of the country (Chang, 2018 ; Kurtzleben, 2011 ).

Additionally, there has been little attention to the notion of consent in regards to sexual harassment in workplaces. People may choose to “go along” with sexually harassing behaviors because of the power dynamics inherent in many organizations. However, this does not mean that these individuals have provided consent. This raises the question of whether individuals with less organizational power can ever provide consent to a person holding organizational power and their economic fate over them. There may be situations where consent cannot be freely given and where power differences create environments in which targets may engage in behaviors because they feel that they have no other choice. On the one hand, this is a hallmark of any sexual harassment research (i.e., unwelcome and unwanted behaviors). On the other hand, a deeper understanding of power and consent in the workplace could provide insights into how to provide effective anti-harassment training and how to stop sexual harassment.

Little is known about how public events related to sexual harassment affect sexual harassment in the workplace. This is particularly notable at this historical moment, following the recent rise of the #MeToo movement on social media. Whereas the Me Too movement originated with the efforts of Tarana Burke in 2006 (Johnson & Hawbaker, 2019 ), the confluence of harassment allegations against numerous public figures and social media practices led in fall 2017 to the #MeToo social media campaign to raise awareness of the ubiquity of workplace sexual harassment (Kantor & Twohey, 2017 ). It is as yet unknown what the #MeToo movement will do to influence workplace sexual harassment and gendered relationships. For example, the #MeToo movement might usher in a shift in disclosure practices, whereby individuals post about sexual harassment incidents in private and public online forums. Further, the disclosures that occurred during the height of #MeToo could make future disclosures (whether online or through organizational processes) more likely, as people might expect that they will be believed when they make sexual harassment accusations. Yet there are already concerns about the unintentional consequences of the #MeToo movement, such that some men are overreacting to the #MeToo wave and fear spending one-on-one time with female colleagues and subordinates in the workplace (Bennold, 2019 ). This historical moment is ripe with opportunity to examine and understand how public events and discourse about sexual harassment affect sexual harassment in the workplace.

Finally, it is important to note that sexual harassment research has been conducted around the world, but primarily in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe, with additional research arising from Asia. The construction of gender within different cultures is not homogenous, and therefore the influence of sociocultural hierarchies of gender on sexual harassment would be context specific. In addition, the legal definitions of sexual harassment can vary widely across countries, with some countries lacking a language or legal basis against sexual harassment. Although the review herein suggests that regardless of whether there is a legal definition or a label for harassment, it is damaging to the people who experience it, this is not yet fully documented. Further research is needed throughout the world, particularly in Africa, South America, and developing economies.

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender and Society , 4 (2), 139–158.

- Adams-Roy, J. , & Barling, J. (1998). Predicting the decision to confront or report sexual harassment. Journal of Organizational Behavior , 19 (4), 329–336.

- Arvey, R. D. , & Cavanaugh, M. A. (1995). Using surveys to assess the prevalence of sexual harassment: Some methodological problems. Journal of Social Issues , 51 (1), 39–52.

- Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) . (2012). Working without fear: Results of the sexual harassment national telephone survey .

- Barling, J. , Dekker, I. , Loughlin, C. A. , Kelloway, E. K. , Fullagar, C. , & Johnson, D. (1996). Prediction and replication of the organizational and personal consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Journal of Managerial Psychology , 11 (5), 4–25.

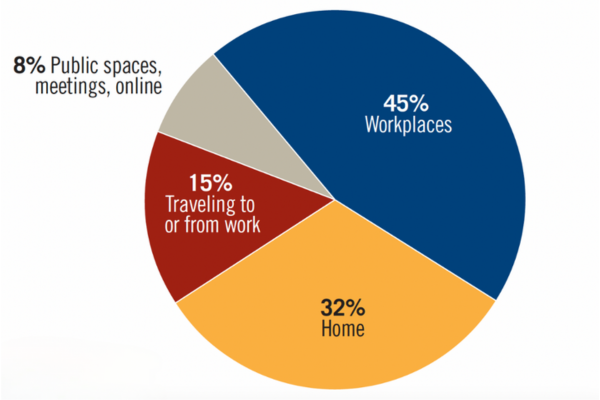

- Barling, J. , Rogers, A. G. , & Kelloway, E. K. (2001). Behind closed doors: In-home workers’ experience of sexual harassment and workplace violence. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 6 (3), 255–269.

- Bayard, K. , Hellerstein, J. , Neumark, D. , & Troske, K. (2003). New evidence on sex segregation and sex differences in wages from matched employee-employer data. Journal of Labor Economics , 21 (4), 887–922.

- Bell, M. E. , Street, A. E. , & Stafford, J. (2014). Victims’ psychosocial well-being after reporting sexual harassment in the military. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation , 15 (2), 133–152.

- Bennold, K. (2019, January 27). Another side of #MeToo: Male managers fearful of mentoring women . New York Times .

- Berdahl, J. L. (2007a). Harassment based on sex: Protecting social status in the context of gender hierarchy. Academy of Management Review , 32 (2), 641–658.

- Berdahl, J. L. (2007b). The sexual harassment of uppity women. Journal of Applied Psychology , 92 (2), 425–437.

- Berdahl, J. L. , Magley, V. J. , & Waldo, C. R. (1996). The sexual harassment of men?: Exploring the concept with theory and data. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 20 (4), 527–547.

- Berdahl, J. L. , & Moore, C. (2006). Workplace harassment: Double jeopardy for minority women. Journal of Applied Psychology , 91 (2), 426–436.

- Bergman, M. E. , & Drasgow, F. (2003). Race as a moderator in a model of sexual harassment: An empirical test. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 8 (2), 131–145.

- Bergman, M. E. , & Henning, J. B. (2008). Sex and ethnicity as moderators in the sexual harassment phenomenon: A revision and test of Fitzgerald et al. (1994). Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 13 (2), 152–167.

- Bergman, M. E. , Langhout, R. D. , Palmieri, P. A. , Cortina, L. M. , & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2002). The (un) reasonableness of reporting: Antecedents and consequences of reporting sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology , 87 (2), 230–242.

- Brooks, L. , & Perot, A. R. (1991). Reporting sexual harassment: Exploring a predictive model. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 15 (1), 31–47.

- Buchanan, N. T. (2005). The nexus of race and gender domination: The racialized sexual harassment of African American women. In P. Morgan & J. Gruber (Eds.), In the company of men: Re-discovering the links between sexual harassment and male domination (pp. 294–320). Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

- Buchanan, N. T. , & Ormerod, A. J. (2002). Racialized sexual harassment in the lives of African American women. Women & Therapy , 25 (3–4), 107–124.

- Burgess, D. , & Borgida, E. (1997). Sexual harassment: An experimental test of sex-role spillover theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 23 (1), 63–75.

- Bursik, K. (1992). Perceptions of sexual harassment in an academic context. Sex Roles , 27 (7–8), 401–412.

- Chang, E. (2018, January 2). “Oh my god, this is so F—ed up”: Inside Silicon Valley’s secretive, orgiastic dark side . Vanity Fair .

- Chen, W. C. , Hwu, H. G. , Kung, S. M. , Chiu, H. J. , & Wang, J. D. (2008). Prevalence and determinants of workplace violence of health care workers in a psychiatric hospital in Taiwan. Journal of Occupational Health , 50 (3), 288–293.

- Cook, T. D. , Campbell, D. T. , & Shadish, W. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Conte, A. (2010). Sexual harassment in the workplace: Law and practice (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Aspen Publishers Online.

- Cortina, L. M. , Fitzgerald, L. F. , & Drasgow, F. (2002). Contextualizing Latina experiences of sexual harassment: Preliminary tests of a structural model. Basic and Applied Social Psychology , 24 (4), 295–311.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum , 1 (8), 139–167.

- Culbertson, A. L. , & Rosenfeld, P. (1993). Understanding sexual harassment through organizational surveys. In P. Rosenfeld , J. E. Edwards , & M. D. Thomas (Eds.), Improving organizational surveys: New directions, methods, and applications (pp. 164–187). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Culbertson, A. L. , & Rosenfeld, P. (1994). Assessment of sexual harassment in the active-duty Navy. Military Psychology , 6 (2), 69–93.

- Das, A. (2009). Sexual harassment at work in the United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 38 (6), 909–921.

- Dionisi, A. M. , & Barling, J. (2018). It hurts me too: Examining the relationship between male gender harassment and observers’ well-being, attitudes, and behaviors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 23 (3), 303–319.

- Dionisi, A. M. , Barling, J. , Dupré, K. E. (2012). Revisiting the comparative outcomes of workplace aggression and sexual harassment. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 17 (4), 398–408.

- Directive 2006/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2006 on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation (recast) . Eur-Lex , Document 32006L0054.

- Employment New Zealand . (2018, May 31). Sexual and racial harassment .

- Fain, T. C. , & Anderton, D. L. (1987). Sexual harassment: Organizational context and diffuse status. Sex Roles , 17 (5–6), 291–311.

- Firestone, J. M. , & Harris, R. J. (2003). Perceptions of effectiveness of responses to sexual harassment in the US military, 1988 and 1995. Gender, Work and Organization , 10 (1), 42–64.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. (1993). Sexual harassment: Violence against women in the workplace. American Psychologist , 48 (10), 1070–1076.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. , Buchanan, N. T. , Collinsworth, L. L. , Magley, V. J. , & Ramos, A. M. (1999). Junk logic: The abuse defense in sexual harassment litigation. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law , 5 (3), 730–759.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. & Cortina, L. M. (2017). Sexual harassment in work organizations: A view from the twenty-first century. In J. W. White & C. Travis (Eds.), Handbook on the psychology of women . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. , Drasgow, F. , Hulin, C. L. , Gelfand, M. J. , & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: a test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied psychology , 82 (4), 578–589.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. , Drasgow, F. , & Magley, V. J. (1999). Sexual harassment in the armed forces: A test of an integrated model. Military Psychology , 11 (3), 329–343.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. , Gelfand, M. J. , & Drasgow, F. (1995). Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology , 17 (4), 425–445.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. , Hulin, C. L. , & Drasgow, F. (1995). The antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: An integrated model. In G. P. Keita & J. J. Hurell (Eds.), Job stress in a changing workforce: Investigating gender, diversity, and family issues (pp. 55–73). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

- Fitzgerald, L. F. , Magley, V. J. , Drasgow, F. , & Waldo, C. R. (1999). Measuring sexual harassment in the military: the sexual experiences questionnaire (SEQ—DoD). Military Psychology , 11 (3), 243–263.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. , & Shullman, S. L. (1993). Sexual harassment: A research analysis and agenda for the 1990s. Journal of Vocational Behavior , 42 (1), 5–27.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. , Swan, S. , & Fischer, K. (1995). Why didn’t she just report him? The psychological and legal implications of women’s responses to sexual harassment. Journal of Social Issues , 51 (1), 117–138.

- Folkman, S. , Lazarus, R. S. , Gruen, R. J. , & DeLongis, A. (1986). Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 50 (3), 571–579.

- Foster, P. J. , & Fullagar, C. J. (2018). Why don’t we report sexual harassment? An application of the theory of planned behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology , 40 (3), 148–160.

- Funk, L. C. , & Werhun, C. D. (2011). “You’re such a girl!” The psychological drain of the gender-role harassment of men. Sex Roles , 65 (1–2), 13.

- Galesic, M. , & Tourangeau, R. (2007). What is sexual harassment? It depends on who asks! Framing effects on survey responses. Applied Cognitive Psychology , 21 (2), 189–202.

- Gelfand, M. J. , Fitzgerald, L. F. , & Drasgow, F. (1995). The structure of sexual harassment: A confirmatory analysis across cultures and settings. Journal of Vocational Behavior , 47 (2), 164–177.

- Glomb, T. M. , Richman, W. L. , Hulin, C. L. , Drasgow, F. , Schneider, K. T. , & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1997). Ambient sexual harassment: An integrated model of antecedents and consequences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 71 (3), 309–328.

- Goldberg, C. , Perry, E. , & Rawski, S. (2018). The direct and indirect effects of organizational tolerance for sexual harassment on the effectiveness of sexual harassment investigation training for HR managers . Human Resource Development Quarterly , 30 (1), 81–100.

- Good, L. , & Cooper, R. (2014). Voicing their complaints? The silence of students working in retail and hospitality and sexual harassment from customers. Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work , 24 (4), 302–316.

- Griffeth, R. W. , Hom, P. W. , & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management , 26 (3), 463–488.

- Gruber, J. (2003). Sexual harassment in the public sector. In M. Paludi & C. A. Paludi Jr. (Eds.), Academic and workplace sexual harassment: A handbook of cultural, social science, management, and legal perspectives (pp. 49–75). Westport, CT: Praeger /Greenwood.

- Gruber, J. E. , & Smith, M. D. (1995). Women’s responses to sexual harassment: A multivariate analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology , 17 (4), 543–562.

- Gutek, B. A. (1985). Sex and the workplace . San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass.

- Gutek, B. A. , & Koss, M. P. (1993). Changed women and changed organizations: Consequences of and coping with sexual harassment. Journal of Vocational Behavior , 42 (1), 28–48.

- de Haas, S. , Timmerman, G. , & Höing, M. (2009). Sexual harassment and health among male and female police officers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 14 (4), 390–401.

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2009). The role of pluralistic ignorance in the reporting of sexual harassment. Basic and Applied Social Psychology , 31 (3), 210–217.

- Harned, M. S. , & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2002). Understanding a link between sexual harassment and eating disorder symptoms: A mediational analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 70 (5), 1170–1181.

- Harned, M. S. , Ormerod, A. J. , Palmieri, P. A. , Collinsworth, L. L. , & Reed, M. (2002). Sexual assault and other types of sexual harassment by workplace personnel: A comparison of antecedents and consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 7 (2), 174–188.

- Harper, S. R. (2013). Am I my brother’s teacher? Black undergraduates, racial socialization, and peer pedagogies in predominantly white postsecondary contexts. Review of Research in Education , 37 (1), 183–211.

- Hay, M. S. , & Elig, T. W. (1999). The 1995 Department of Defense sexual harassment survey: Overview and methodology. Military Psychology , 11 (3), 233–242.

- Hesson-McInnis, M. S. , & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1997). Sexual harassment: A preliminary test of an integrative model. Journal of Applied Social Psychology , 27 , 877–901.

- Ho, I. K. , Dinh, K. T. , Bellefontaine, S. A. , & Irving, A. L. (2012). Sexual harassment and posttraumatic stress symptoms among Asian and White women. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma , 21 (1), 95–113.

- Holland, K. J. , Rabelo, V. C. , Gustafson, A. M. , Seabrook, R. C. , & Cortina, L. M. (2016). Sexual harassment against men: Examining the roles of feminist activism, sexuality, and organizational context. Psychology of Men & Masculinity , 17 (1), 17–29.

- Hotelling, K. (1991). Sexual harassment: A problem shielded by silence. Journal of Counseling & Development , 69 (6), 497–501.

- Huen, Y. (2007). Workplace sexual harassment in Japan: A review of combating measures taken. Asian Survey , 47 (5), 811–827.

- Hulin, C. L. , Fitzgerald, L. F. , & Drasgow, F. (1996). Organizational influences on sexual harassment . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Hutagalung, F. , & Ishak, Z. (2012). Sexual harassment: A predictor to job satisfaction and work stress among women employees. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences , 65 , 723–730.

- Ilies, R. , Hauserman, N. , Schwochau, S. , & Stibal, J. (2003). Reported incidence rates of work-related sexual harassment in the United States: Using meta-analysis to explain reported rate disparities. Personnel Psychology , 56 (3), 607–631.

- Jatoi, B. (2018, February 8). Sexual harassment laws in Pakistan . The Express Tribune .

- Johnson, R. B. , & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational researcher , 33 (7), 14–26.

- Johnson, C. A. & Hawbaker K. (2019, March 7). #MeToo: A timeline of events . Chicago Tribune .

- Kantor, J. & Twohey, M. (2017, October 5). Harvey Weinstein paid off sexual harassment accusers for decades . New York Times .

- Knapp, D. E. , Faley, R. H. , Ekeberg, S. E. , & Dubois, C. L. (1997). Determinants of target responses to sexual harassment: A conceptual framework. Academy of Management Review , 22 (3), 687–729.

- Konik, J. , & Cortina, L. M. (2008). Policing gender at work: Intersections of harassment based on sex and sexuality. Social Justice Research , 21 (3), 313–337.

- Kurtzleben, D. (2011, May 13). The 10 cities with the greatest and least equality . US News and World Report .

- Langhout, R. D. , Bergman, M. E. , Cortina, L. M. , Fitzgerald, L. F. , Drasgow, F. , & Williams, J. H. (2005). Sexual harassment severity: Assessing situational and personal determinants and outcomes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology , 35 (5), 975–1007.

- Latcheva, R. (2017). Sexual harassment in the European Union: A pervasive but still hidden form of gender-based violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence , 32 , 1821–1852.

- Lazarus, R. S. , & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, coping and appraisal . New York, NY: Springer.

- Lengnick-Hall, M. L. 1995. Sexual harassment research: A methodological critique. Personnel Psychology , 48 (4), 841–864.

- Lim, S. , & Cortina, L. M. (2005). Interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace: The interface and impact of general incivility and sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology , 90 (3), 483–496.

- Liu, X.‑Y. , Kwan, H. K. , & Chiu, R. K. (2014). Customer sexual harassment and frontline employees’ service performance in China. Human Relations , 67 , 333–356.

- Maass, A. , Cadinu, M. , Guarnieri, G. , & Grasselli, A. (2003). Sexual harassment under social identity threat: The computer harassment paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 85 (5), 853–870.

- Magley, V. J. , Hulin, C. L. , Fitzgerald, L. F. , & DeNardo, M. (1999a). Outcomes of self-labeling sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology , 84 (3), 390–402.

- Magley, V. J. , Waldo, C. R. , Drasgow, F. , & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1999b). The impact of sexual harassment on military personnel: Is it the same for men and women? Military Psychology , 11 (3), 283–302.

- Malamut, A. B. , & Offermann, L. R. (2001). Coping with sexual harassment: Personal, environmental, and cognitive determinants. Journal of Applied Psychology , 86 (6), 1152.

- Malik, N. I. , Malik, S. , Qureshi, N. , & Atta, M. (2014). Sexual harassment as predictor of low self esteem and job satisfaction among in-training nurses. FWU Journal of Social Sciences , 8 (2), 107–116.

- Marsh, J. , Patel, S. , Gelaye, B. , Goshu, M. , Worku, A. , Williams, M. A. , & Berhane, Y. (2009). Prevalence of workplace abuse and sexual harassment among female faculty and staff. Journal of Occupational Health , 51 (4), 314–322.

- Mathieu, C. , Fabi, B. , Lacoursière, R. , & Raymond, L. (2016). The role of supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment on employee turnover. Journal of Management & Organization , 22 (1), 113–129.

- Maume, D. J., Jr. (1999). Glass ceilings and glass escalators: Occupational segregation and race and sex differences in managerial promotions. Work and Occupations , 26 (4), 483–509.

- McDonald, P. (2012). Workplace sexual harassment 30 years on: A review of the literature. International Journal of Management Reviews , 14 (1), 1–17.

- McLaughlin, H. , Uggen, C. , & Blackstone, A. (2017). The economic and career effects of sexual harassment on working women. Gender & Society , 31 (3), 333–358.

- Merkin, R. S. , & Shah, M. K. (2014). The impact of sexual harassment on job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and absenteeism: findings from Pakistan compared to the United States. SpringerPlus , 3 (1), 215.

- Meyer, J. P. , Stanley, D. J. , Herscovitch, L. , & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior , 61 (1), 20–52.

- Miner-Rubino, K. , & Jayaratne, T. E. (2011). Feminist survey research. In S. N. Hesse-Biber & P. L. Leavy (Ed.), Feminist research practice (pp. 293–325). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Munson, L. J. , Hulin, C. , & Drasgow, F. (2000). Longitudinal analysis of dispositional influences and sexual harassment: Effects on job and psychological outcomes. Personnel Psychology , 53 (1), 21–46.

- Nielsen, M. B. , Bjørkelo, B. , Notelaers, G. , & Einarsen, S. (2010). Sexual harassment: Prevalence, outcomes, and gender differences assessed by three different estimation methods. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma , 19 (3), 252–274.

- Nielsen, M. B. , & Einarsen, S. (2012). Prospective relationships between workplace sexual harassment and psychological distress. Occupational Medicine , 62 (3), 226–228.

- Nye, C. D. , Brummel, B. J. , & Drasgow, F. (2014). Understanding sexual harassment using aggregate construct models. Journal of Applied Psychology , 99 (6), 1204–1221.