This document originally came from the Journal of Mammalogy courtesy of Dr. Ronald Barry, a former editor of the journal.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Yale J Biol Med

- v.84(3); 2011 Sep

Focus: Education — Career Advice

How to write your first research paper.

Writing a research manuscript is an intimidating process for many novice writers in the sciences. One of the stumbling blocks is the beginning of the process and creating the first draft. This paper presents guidelines on how to initiate the writing process and draft each section of a research manuscript. The paper discusses seven rules that allow the writer to prepare a well-structured and comprehensive manuscript for a publication submission. In addition, the author lists different strategies for successful revision. Each of those strategies represents a step in the revision process and should help the writer improve the quality of the manuscript. The paper could be considered a brief manual for publication.

It is late at night. You have been struggling with your project for a year. You generated an enormous amount of interesting data. Your pipette feels like an extension of your hand, and running western blots has become part of your daily routine, similar to brushing your teeth. Your colleagues think you are ready to write a paper, and your lab mates tease you about your “slow” writing progress. Yet days pass, and you cannot force yourself to sit down to write. You have not written anything for a while (lab reports do not count), and you feel you have lost your stamina. How does the writing process work? How can you fit your writing into a daily schedule packed with experiments? What section should you start with? What distinguishes a good research paper from a bad one? How should you revise your paper? These and many other questions buzz in your head and keep you stressed. As a result, you procrastinate. In this paper, I will discuss the issues related to the writing process of a scientific paper. Specifically, I will focus on the best approaches to start a scientific paper, tips for writing each section, and the best revision strategies.

1. Schedule your writing time in Outlook

Whether you have written 100 papers or you are struggling with your first, starting the process is the most difficult part unless you have a rigid writing schedule. Writing is hard. It is a very difficult process of intense concentration and brain work. As stated in Hayes’ framework for the study of writing: “It is a generative activity requiring motivation, and it is an intellectual activity requiring cognitive processes and memory” [ 1 ]. In his book How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing , Paul Silvia says that for some, “it’s easier to embalm the dead than to write an article about it” [ 2 ]. Just as with any type of hard work, you will not succeed unless you practice regularly. If you have not done physical exercises for a year, only regular workouts can get you into good shape again. The same kind of regular exercises, or I call them “writing sessions,” are required to be a productive author. Choose from 1- to 2-hour blocks in your daily work schedule and consider them as non-cancellable appointments. When figuring out which blocks of time will be set for writing, you should select the time that works best for this type of work. For many people, mornings are more productive. One Yale University graduate student spent a semester writing from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. when her lab was empty. At the end of the semester, she was amazed at how much she accomplished without even interrupting her regular lab hours. In addition, doing the hardest task first thing in the morning contributes to the sense of accomplishment during the rest of the day. This positive feeling spills over into our work and life and has a very positive effect on our overall attitude.

Rule 1: Create regular time blocks for writing as appointments in your calendar and keep these appointments.

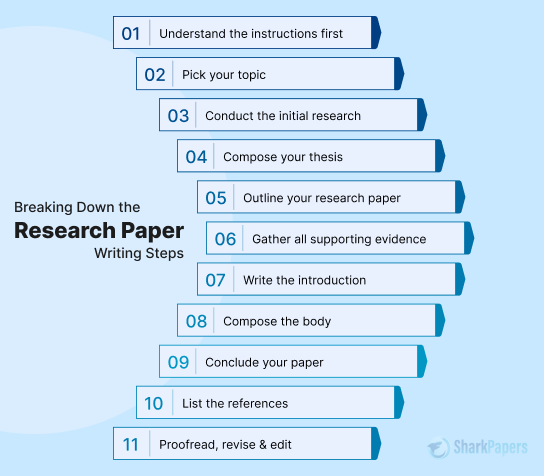

2. start with an outline.

Now that you have scheduled time, you need to decide how to start writing. The best strategy is to start with an outline. This will not be an outline that you are used to, with Roman numerals for each section and neat parallel listing of topic sentences and supporting points. This outline will be similar to a template for your paper. Initially, the outline will form a structure for your paper; it will help generate ideas and formulate hypotheses. Following the advice of George M. Whitesides, “. . . start with a blank piece of paper, and write down, in any order, all important ideas that occur to you concerning the paper” [ 3 ]. Use Table 1 as a starting point for your outline. Include your visuals (figures, tables, formulas, equations, and algorithms), and list your findings. These will constitute the first level of your outline, which will eventually expand as you elaborate.

The next stage is to add context and structure. Here you will group all your ideas into sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion ( Table 2 ). This step will help add coherence to your work and sift your ideas.

Now that you have expanded your outline, you are ready for the next step: discussing the ideas for your paper with your colleagues and mentor. Many universities have a writing center where graduate students can schedule individual consultations and receive assistance with their paper drafts. Getting feedback during early stages of your draft can save a lot of time. Talking through ideas allows people to conceptualize and organize thoughts to find their direction without wasting time on unnecessary writing. Outlining is the most effective way of communicating your ideas and exchanging thoughts. Moreover, it is also the best stage to decide to which publication you will submit the paper. Many people come up with three choices and discuss them with their mentors and colleagues. Having a list of journal priorities can help you quickly resubmit your paper if your paper is rejected.

Rule 2: Create a detailed outline and discuss it with your mentor and peers.

3. continue with drafts.

After you get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to, the process of real writing begins. Copy your outline into a separate file and expand on each of the points, adding data and elaborating on the details. When you create the first draft, do not succumb to the temptation of editing. Do not slow down to choose a better word or better phrase; do not halt to improve your sentence structure. Pour your ideas into the paper and leave revision and editing for later. As Paul Silvia explains, “Revising while you generate text is like drinking decaffeinated coffee in the early morning: noble idea, wrong time” [ 2 ].

Many students complain that they are not productive writers because they experience writer’s block. Staring at an empty screen is frustrating, but your screen is not really empty: You have a template of your article, and all you need to do is fill in the blanks. Indeed, writer’s block is a logical fallacy for a scientist ― it is just an excuse to procrastinate. When scientists start writing a research paper, they already have their files with data, lab notes with materials and experimental designs, some visuals, and tables with results. All they need to do is scrutinize these pieces and put them together into a comprehensive paper.

3.1. Starting with Materials and Methods

If you still struggle with starting a paper, then write the Materials and Methods section first. Since you have all your notes, it should not be problematic for you to describe the experimental design and procedures. Your most important goal in this section is to be as explicit as possible by providing enough detail and references. In the end, the purpose of this section is to allow other researchers to evaluate and repeat your work. So do not run into the same problems as the writers of the sentences in (1):

1a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation. 1b. To isolate T cells, lymph nodes were collected.

As you can see, crucial pieces of information are missing: the speed of centrifuging your bacteria, the time, and the temperature in (1a); the source of lymph nodes for collection in (b). The sentences can be improved when information is added, as in (2a) and (2b), respectfully:

2a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000g for 15 min at 25°C. 2b. To isolate T cells, mediastinal and mesenteric lymph nodes from Balb/c mice were collected at day 7 after immunization with ovabumin.

If your method has previously been published and is well-known, then you should provide only the literature reference, as in (3a). If your method is unpublished, then you need to make sure you provide all essential details, as in (3b).

3a. Stem cells were isolated, according to Johnson [23]. 3b. Stem cells were isolated using biotinylated carbon nanotubes coated with anti-CD34 antibodies.

Furthermore, cohesion and fluency are crucial in this section. One of the malpractices resulting in disrupted fluency is switching from passive voice to active and vice versa within the same paragraph, as shown in (4). This switching misleads and distracts the reader.

4. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness [ 4 ].

The problem with (4) is that the reader has to switch from the point of view of the experiment (passive voice) to the point of view of the experimenter (active voice). This switch causes confusion about the performer of the actions in the first and the third sentences. To improve the coherence and fluency of the paragraph above, you should be consistent in choosing the point of view: first person “we” or passive voice [ 5 ]. Let’s consider two revised examples in (5).

5a. We programmed behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods) as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music. We operationalized the preferred and unpreferred status of the music along a continuum of pleasantness. 5b. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. Ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal were taken as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness.

If you choose the point of view of the experimenter, then you may end up with repetitive “we did this” sentences. For many readers, paragraphs with sentences all beginning with “we” may also sound disruptive. So if you choose active sentences, you need to keep the number of “we” subjects to a minimum and vary the beginnings of the sentences [ 6 ].

Interestingly, recent studies have reported that the Materials and Methods section is the only section in research papers in which passive voice predominantly overrides the use of the active voice [ 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. For example, Martínez shows a significant drop in active voice use in the Methods sections based on the corpus of 1 million words of experimental full text research articles in the biological sciences [ 7 ]. According to the author, the active voice patterned with “we” is used only as a tool to reveal personal responsibility for the procedural decisions in designing and performing experimental work. This means that while all other sections of the research paper use active voice, passive voice is still the most predominant in Materials and Methods sections.

Writing Materials and Methods sections is a meticulous and time consuming task requiring extreme accuracy and clarity. This is why when you complete your draft, you should ask for as much feedback from your colleagues as possible. Numerous readers of this section will help you identify the missing links and improve the technical style of this section.

Rule 3: Be meticulous and accurate in describing the Materials and Methods. Do not change the point of view within one paragraph.

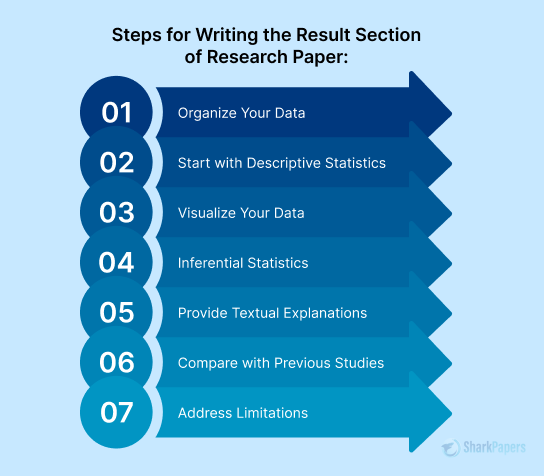

3.2. writing results section.

For many authors, writing the Results section is more intimidating than writing the Materials and Methods section . If people are interested in your paper, they are interested in your results. That is why it is vital to use all your writing skills to objectively present your key findings in an orderly and logical sequence using illustrative materials and text.

Your Results should be organized into different segments or subsections where each one presents the purpose of the experiment, your experimental approach, data including text and visuals (tables, figures, schematics, algorithms, and formulas), and data commentary. For most journals, your data commentary will include a meaningful summary of the data presented in the visuals and an explanation of the most significant findings. This data presentation should not repeat the data in the visuals, but rather highlight the most important points. In the “standard” research paper approach, your Results section should exclude data interpretation, leaving it for the Discussion section. However, interpretations gradually and secretly creep into research papers: “Reducing the data, generalizing from the data, and highlighting scientific cases are all highly interpretive processes. It should be clear by now that we do not let the data speak for themselves in research reports; in summarizing our results, we interpret them for the reader” [ 10 ]. As a result, many journals including the Journal of Experimental Medicine and the Journal of Clinical Investigation use joint Results/Discussion sections, where results are immediately followed by interpretations.

Another important aspect of this section is to create a comprehensive and supported argument or a well-researched case. This means that you should be selective in presenting data and choose only those experimental details that are essential for your reader to understand your findings. You might have conducted an experiment 20 times and collected numerous records, but this does not mean that you should present all those records in your paper. You need to distinguish your results from your data and be able to discard excessive experimental details that could distract and confuse the reader. However, creating a picture or an argument should not be confused with data manipulation or falsification, which is a willful distortion of data and results. If some of your findings contradict your ideas, you have to mention this and find a plausible explanation for the contradiction.

In addition, your text should not include irrelevant and peripheral information, including overview sentences, as in (6).

6. To show our results, we first introduce all components of experimental system and then describe the outcome of infections.

Indeed, wordiness convolutes your sentences and conceals your ideas from readers. One common source of wordiness is unnecessary intensifiers. Adverbial intensifiers such as “clearly,” “essential,” “quite,” “basically,” “rather,” “fairly,” “really,” and “virtually” not only add verbosity to your sentences, but also lower your results’ credibility. They appeal to the reader’s emotions but lower objectivity, as in the common examples in (7):

7a. Table 3 clearly shows that … 7b. It is obvious from figure 4 that …

Another source of wordiness is nominalizations, i.e., nouns derived from verbs and adjectives paired with weak verbs including “be,” “have,” “do,” “make,” “cause,” “provide,” and “get” and constructions such as “there is/are.”

8a. We tested the hypothesis that there is a disruption of membrane asymmetry. 8b. In this paper we provide an argument that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

In the sentences above, the abstract nominalizations “disruption” and “argument” do not contribute to the clarity of the sentences, but rather clutter them with useless vocabulary that distracts from the meaning. To improve your sentences, avoid unnecessary nominalizations and change passive verbs and constructions into active and direct sentences.

9a. We tested the hypothesis that the membrane asymmetry is disrupted. 9b. In this paper we argue that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

Your Results section is the heart of your paper, representing a year or more of your daily research. So lead your reader through your story by writing direct, concise, and clear sentences.

Rule 4: Be clear, concise, and objective in describing your Results.

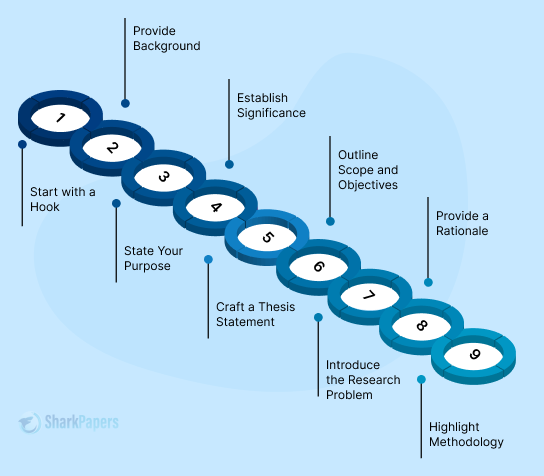

3.3. now it is time for your introduction.

Now that you are almost half through drafting your research paper, it is time to update your outline. While describing your Methods and Results, many of you diverged from the original outline and re-focused your ideas. So before you move on to create your Introduction, re-read your Methods and Results sections and change your outline to match your research focus. The updated outline will help you review the general picture of your paper, the topic, the main idea, and the purpose, which are all important for writing your introduction.

The best way to structure your introduction is to follow the three-move approach shown in Table 3 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak [ 11 ].

The moves and information from your outline can help to create your Introduction efficiently and without missing steps. These moves are traffic signs that lead the reader through the road of your ideas. Each move plays an important role in your paper and should be presented with deep thought and care. When you establish the territory, you place your research in context and highlight the importance of your research topic. By finding the niche, you outline the scope of your research problem and enter the scientific dialogue. The final move, “occupying the niche,” is where you explain your research in a nutshell and highlight your paper’s significance. The three moves allow your readers to evaluate their interest in your paper and play a significant role in the paper review process, determining your paper reviewers.

Some academic writers assume that the reader “should follow the paper” to find the answers about your methodology and your findings. As a result, many novice writers do not present their experimental approach and the major findings, wrongly believing that the reader will locate the necessary information later while reading the subsequent sections [ 5 ]. However, this “suspense” approach is not appropriate for scientific writing. To interest the reader, scientific authors should be direct and straightforward and present informative one-sentence summaries of the results and the approach.

Another problem is that writers understate the significance of the Introduction. Many new researchers mistakenly think that all their readers understand the importance of the research question and omit this part. However, this assumption is faulty because the purpose of the section is not to evaluate the importance of the research question in general. The goal is to present the importance of your research contribution and your findings. Therefore, you should be explicit and clear in describing the benefit of the paper.

The Introduction should not be long. Indeed, for most journals, this is a very brief section of about 250 to 600 words, but it might be the most difficult section due to its importance.

Rule 5: Interest your reader in the Introduction section by signalling all its elements and stating the novelty of the work.

3.4. discussion of the results.

For many scientists, writing a Discussion section is as scary as starting a paper. Most of the fear comes from the variation in the section. Since every paper has its unique results and findings, the Discussion section differs in its length, shape, and structure. However, some general principles of writing this section still exist. Knowing these rules, or “moves,” can change your attitude about this section and help you create a comprehensive interpretation of your results.

The purpose of the Discussion section is to place your findings in the research context and “to explain the meaning of the findings and why they are important, without appearing arrogant, condescending, or patronizing” [ 11 ]. The structure of the first two moves is almost a mirror reflection of the one in the Introduction. In the Introduction, you zoom in from general to specific and from the background to your research question; in the Discussion section, you zoom out from the summary of your findings to the research context, as shown in Table 4 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak and Hess [ 11 , 12 ].

The biggest challenge for many writers is the opening paragraph of the Discussion section. Following the moves in Table 1 , the best choice is to start with the study’s major findings that provide the answer to the research question in your Introduction. The most common starting phrases are “Our findings demonstrate . . .,” or “In this study, we have shown that . . .,” or “Our results suggest . . .” In some cases, however, reminding the reader about the research question or even providing a brief context and then stating the answer would make more sense. This is important in those cases where the researcher presents a number of findings or where more than one research question was presented. Your summary of the study’s major findings should be followed by your presentation of the importance of these findings. One of the most frequent mistakes of the novice writer is to assume the importance of his findings. Even if the importance is clear to you, it may not be obvious to your reader. Digesting the findings and their importance to your reader is as crucial as stating your research question.

Another useful strategy is to be proactive in the first move by predicting and commenting on the alternative explanations of the results. Addressing potential doubts will save you from painful comments about the wrong interpretation of your results and will present you as a thoughtful and considerate researcher. Moreover, the evaluation of the alternative explanations might help you create a logical step to the next move of the discussion section: the research context.

The goal of the research context move is to show how your findings fit into the general picture of the current research and how you contribute to the existing knowledge on the topic. This is also the place to discuss any discrepancies and unexpected findings that may otherwise distort the general picture of your paper. Moreover, outlining the scope of your research by showing the limitations, weaknesses, and assumptions is essential and adds modesty to your image as a scientist. However, make sure that you do not end your paper with the problems that override your findings. Try to suggest feasible explanations and solutions.

If your submission does not require a separate Conclusion section, then adding another paragraph about the “take-home message” is a must. This should be a general statement reiterating your answer to the research question and adding its scientific implications, practical application, or advice.

Just as in all other sections of your paper, the clear and precise language and concise comprehensive sentences are vital. However, in addition to that, your writing should convey confidence and authority. The easiest way to illustrate your tone is to use the active voice and the first person pronouns. Accompanied by clarity and succinctness, these tools are the best to convince your readers of your point and your ideas.

Rule 6: Present the principles, relationships, and generalizations in a concise and convincing tone.

4. choosing the best working revision strategies.

Now that you have created the first draft, your attitude toward your writing should have improved. Moreover, you should feel more confident that you are able to accomplish your project and submit your paper within a reasonable timeframe. You also have worked out your writing schedule and followed it precisely. Do not stop ― you are only at the midpoint from your destination. Just as the best and most precious diamond is no more than an unattractive stone recognized only by trained professionals, your ideas and your results may go unnoticed if they are not polished and brushed. Despite your attempts to present your ideas in a logical and comprehensive way, first drafts are frequently a mess. Use the advice of Paul Silvia: “Your first drafts should sound like they were hastily translated from Icelandic by a non-native speaker” [ 2 ]. The degree of your success will depend on how you are able to revise and edit your paper.

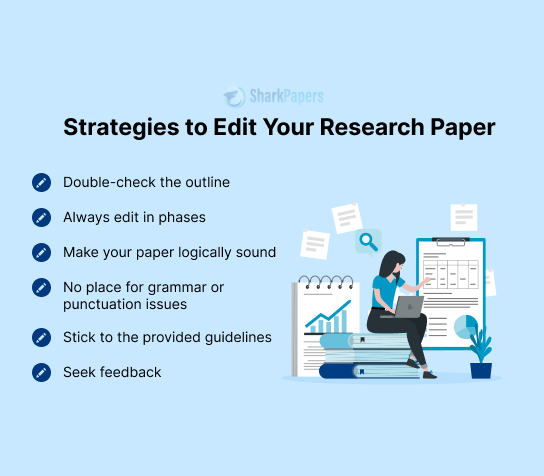

The revision can be done at the macrostructure and the microstructure levels [ 13 ]. The macrostructure revision includes the revision of the organization, content, and flow. The microstructure level includes individual words, sentence structure, grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

The best way to approach the macrostructure revision is through the outline of the ideas in your paper. The last time you updated your outline was before writing the Introduction and the Discussion. Now that you have the beginning and the conclusion, you can take a bird’s-eye view of the whole paper. The outline will allow you to see if the ideas of your paper are coherently structured, if your results are logically built, and if the discussion is linked to the research question in the Introduction. You will be able to see if something is missing in any of the sections or if you need to rearrange your information to make your point.

The next step is to revise each of the sections starting from the beginning. Ideally, you should limit yourself to working on small sections of about five pages at a time [ 14 ]. After these short sections, your eyes get used to your writing and your efficiency in spotting problems decreases. When reading for content and organization, you should control your urge to edit your paper for sentence structure and grammar and focus only on the flow of your ideas and logic of your presentation. Experienced researchers tend to make almost three times the number of changes to meaning than novice writers [ 15 , 16 ]. Revising is a difficult but useful skill, which academic writers obtain with years of practice.

In contrast to the macrostructure revision, which is a linear process and is done usually through a detailed outline and by sections, microstructure revision is a non-linear process. While the goal of the macrostructure revision is to analyze your ideas and their logic, the goal of the microstructure editing is to scrutinize the form of your ideas: your paragraphs, sentences, and words. You do not need and are not recommended to follow the order of the paper to perform this type of revision. You can start from the end or from different sections. You can even revise by reading sentences backward, sentence by sentence and word by word.

One of the microstructure revision strategies frequently used during writing center consultations is to read the paper aloud [ 17 ]. You may read aloud to yourself, to a tape recorder, or to a colleague or friend. When reading and listening to your paper, you are more likely to notice the places where the fluency is disrupted and where you stumble because of a very long and unclear sentence or a wrong connector.

Another revision strategy is to learn your common errors and to do a targeted search for them [ 13 ]. All writers have a set of problems that are specific to them, i.e., their writing idiosyncrasies. Remembering these problems is as important for an academic writer as remembering your friends’ birthdays. Create a list of these idiosyncrasies and run a search for these problems using your word processor. If your problem is demonstrative pronouns without summary words, then search for “this/these/those” in your text and check if you used the word appropriately. If you have a problem with intensifiers, then search for “really” or “very” and delete them from the text. The same targeted search can be done to eliminate wordiness. Searching for “there is/are” or “and” can help you avoid the bulky sentences.

The final strategy is working with a hard copy and a pencil. Print a double space copy with font size 14 and re-read your paper in several steps. Try reading your paper line by line with the rest of the text covered with a piece of paper. When you are forced to see only a small portion of your writing, you are less likely to get distracted and are more likely to notice problems. You will end up spotting more unnecessary words, wrongly worded phrases, or unparallel constructions.

After you apply all these strategies, you are ready to share your writing with your friends, colleagues, and a writing advisor in the writing center. Get as much feedback as you can, especially from non-specialists in your field. Patiently listen to what others say to you ― you are not expected to defend your writing or explain what you wanted to say. You may decide what you want to change and how after you receive the feedback and sort it in your head. Even though some researchers make the revision an endless process and can hardly stop after a 14th draft; having from five to seven drafts of your paper is a norm in the sciences. If you can’t stop revising, then set a deadline for yourself and stick to it. Deadlines always help.

Rule 7: Revise your paper at the macrostructure and the microstructure level using different strategies and techniques. Receive feedback and revise again.

5. it is time to submit.

It is late at night again. You are still in your lab finishing revisions and getting ready to submit your paper. You feel happy ― you have finally finished a year’s worth of work. You will submit your paper tomorrow, and regardless of the outcome, you know that you can do it. If one journal does not take your paper, you will take advantage of the feedback and resubmit again. You will have a publication, and this is the most important achievement.

What is even more important is that you have your scheduled writing time that you are going to keep for your future publications, for reading and taking notes, for writing grants, and for reviewing papers. You are not going to lose stamina this time, and you will become a productive scientist. But for now, let’s celebrate the end of the paper.

- Hayes JR. In: The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences, and Applications. Levy CM, Ransdell SE, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing; pp. 1–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silvia PJ. How to Write a Lot. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitesides GM. Whitesides’ Group: Writing a Paper. Adv Mater. 2004; 16 (15):1375–1377. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soto D, Funes MJ, Guzmán-García A, Warbrick T, Rotshtein T, Humphreys GW. Pleasant music overcomes the loss of awareness in patients with visual neglect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009; 106 (14):6011–6016. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofmann AH. Scientific Writing and Communication. Papers, Proposals, and Presentations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeiger M. Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez I. Native and non-native writers’ use of first person pronouns in the different sections of biology research articles in English. Journal of Second Language Writing. 2005; 14 (3):174–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodman L. The Active Voice In Scientific Articles: Frequency And Discourse Functions. Journal Of Technical Writing And Communication. 1994; 24 (3):309–331. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarone LE, Dwyer S, Gillette S, Icke V. On the use of the passive in two astrophysics journal papers with extensions to other languages and other fields. English for Specific Purposes. 1998; 17 :113–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Penrose AM, Katz SB. Writing in the sciences: Exploring conventions of scientific discourse. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swales JM, Feak CB. Academic Writing for Graduate Students. 2nd edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hess DR. How to Write an Effective Discussion. Respiratory Care. 2004; 29 (10):1238–1241. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belcher WL. Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks: a guide to academic publishing success. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Single PB. Demystifying Dissertation Writing: A Streamlined Process of Choice of Topic to Final Text. Virginia: Stylus Publishing LLC; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Faigley L, Witte SP. Analyzing revision. Composition and Communication. 1981; 32 :400–414. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flower LS, Hayes JR, Carey L, Schriver KS, Stratman J. Detection, diagnosis, and the strategies of revision. College Composition and Communication. 1986; 37 (1):16–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Young BR. In: A Tutor’s Guide: Helping Writers One to One. Rafoth B, editor. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers; 2005. Can You Proofread This? pp. 140–158. [ Google Scholar ]

BIOLOGY JUNCTION

Test And Quizzes for Biology, Pre-AP, Or AP Biology For Teachers And Students

A Step-By-Step Guide on Writing a Biology Research Paper

For many students, writing a biology research paper can seem like a daunting task. They want to come up with the best possible report, but they don’t realize that planning the entire writing process can improve the quality of their work and save them time while writing. In this article, you’ll learn how to find a good topic, outline your paper, use statistical tests, and avoid using hedge words.

Finding a good topic

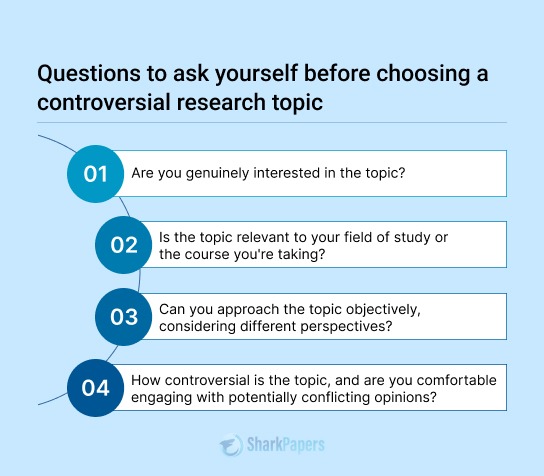

The first step in writing a well-constructed biology research paper is choosing a topic. There are a variety of topics to choose from within the biological field. Choose one that interests you and captures your attention. A compelling topic motivates you to work hard and produce a high-quality paper.

While choosing a topic, keep in mind that biology research is time-consuming and requires extensive research. For this reason, choosing a topic that piques the interest of the reader is crucial. In addition to this, you should choose a topic that is appropriate for the type of biology paper you need to write. After all, you do not want to bore the reader with an inane paper.

A good biology research paper topic should be well-supported by solid scientific evidence. Select a topic only after thorough research, and be sure to include steps and references from reliable sources. A biological research paper topic can be an interesting journey into the world of nature. You could choose to research the effects of stress on the human body or investigate the biological mechanisms of the human reproductive system.

Outlining your paper

The first step in drafting a biological research paper is to create an outline. This is meant to be a roadmap that helps you understand and visualize the subject. An outline can help you avoid common writing mistakes and shape your paper into a serious piece of work. The next step is to gather information about the subject that will support your main idea.

Once you have a topic, you can start writing your outline. Outlines should include at least one idea, a brief introduction, and a conclusion. The introduction, ideas, and conclusion should be numbered in the order you plan to present your information. The main ideas are generally a collection of facts and figures. For example, in a literature review, these points might be chapters from a book, a series of dates from history, or the methods and results of a scientific paper.

When writing a biological research paper, you should use scholarly sources. While there is a lot of misinformation on the internet, it’s best to stick to academic essay writing service to get the most accurate information. Most libraries allow you to select a peer-review filter that will restrict your search results to academic journals. It’s also helpful to be familiar with the differences between scholarly and popular sources.

Using statistical tests

Using statistical tests when writing a biological paper requires that you make certain assumptions about the results you are describing. The most common statistical tests are parametric tests that are based on assumptions about conditions or parameters. About 22% of the papers in our review reported violations of these assumptions, and such violations can lead to inappropriate or invalid conclusions.

Statistical tests are important in biological research because they allow researchers to determine if their data is statistically significant or not. The power of these tests depends on the size of the dataset. Larger datasets produce more significant results. The power of these tests also depends on the assumption of independence between measurements. This is important because the results can be different if there are duplications or different levels of replications.

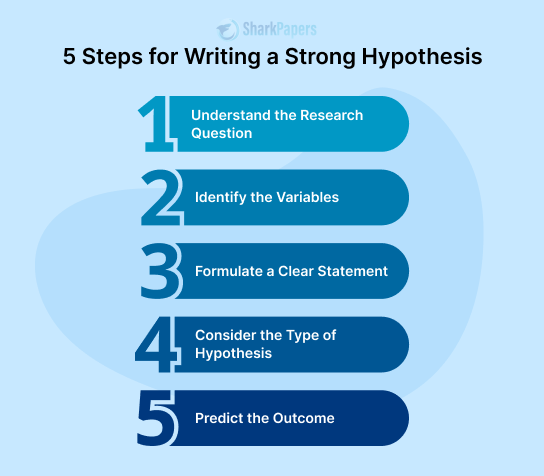

Hypothesis tests are useful in evaluating experimental data. They identify differences and patterns in data. They are useful tools for structuring biological research.

Avoiding hedge words

Hedge words are phrases or words used to express uncertainty in a scientific paper. They can help writers avoid making inaccurate claims while still being respectful of the reader’s opinion. However, writers must be careful to avoid using too many hedges.

Listed below are a few guidelines to help you avoid these words:

- Hedge words shift the burden of responsibility from the writer to the reader.

- Hedge words can be a sign of uncertainty or overstatement. They can also be used to limit the scope of an assertion. They also convey an opinion or hypothesis. When choosing a hedging strategy, be careful not to use words such as “no data” or “unreliable.” These words can convey a degree of uncertainty and imply that the findings cannot be confirmed.

The use of hedge words is common in academic writing. However, they hurt your audience. It is a linguistic strategy that writers use as a way to reassure readers. The goal is to guide readers and make them feel comfortable with the idea that the author does not know all the answers.

Choosing a format

Biological research papers have different formats, and you should choose one that suits the nature of your paper. It should be based on credible and peer-reviewed sources. The best sources to use for biology papers are books, specialized journals, and databases. Avoid personal blogs, social networks, and internet discussions, as these are not suitable for a research paper.

Biology research papers focus on a specific issue and present different arguments in support of a thesis. Traditionally, they are based on peer-reviewed sources, but you can also conduct your independent research and present unique findings. Biology is a complex field of study. The subject matter varies, from the basic structure of living things to the functions of different organs. It also explores the process of evolution and the life span of different species.

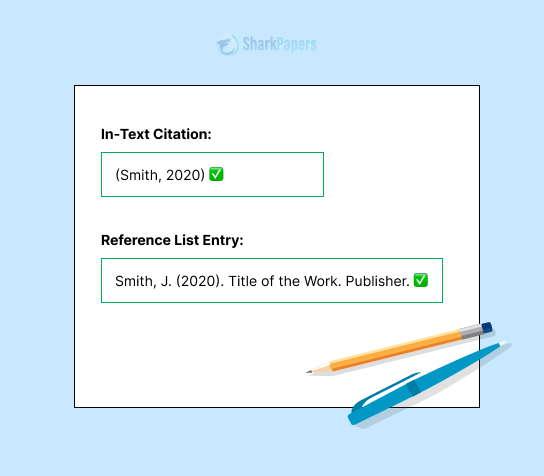

Formatting your bibliography

When writing a biological research paper, the format of your bibliography is crucial. It should follow a standardized citation style such as the “Author, Date” scientific style. The format should be arranged alphabetically by author, and you should use numbered references to indicate key sources.

Reference lists must be comprehensive and contain enough information to enable readers to find the sources themselves. Although the format is not as important as completeness, it can help readers quickly identify the authors and sources. Bibliographies are usually reverse-indented to make them easier to find.

In-text citations should include the author’s last name, preferred name, and the page number. Usually, authors do not separate their surname and year of publication. In addition, you should also include the location, which is usually the publisher’s office.

If a work has more than four authors, you should list up to ten in the reference list. The first author’s surname should be used, followed by “et al.” Likewise, you should list more than ten authors in the reference list.

When writing a biological research paper, it is important to ensure that your bibliography is formatted properly. When you write the title, you should use boldface and uppercase letters. The title should also be focused, not too long or too short. It should take one or two lines and all text should be double-spaced. You should also type the author’s name after the title. Don’t forget to indicate the location of your research as well as the date you submitted the paper.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Write a Biology Research Paper: A Comprehensive Guide

In academic circles, mastering the art of writing a biology research paper is imperative. This guide offers you a holistic approach to tackle this challenging task. You'll find detailed insights into planning, structuring, and executing your paper, ensuring that you engage your audience with well-researched, credible data. From the initial steps to the final submission, we'll walk you through each process, dissecting the complex parts to provide a manageable roadmap. We’ll cover topics from starting a biology research paper to its outline, body, and conclusion, all while keeping your academic goals in focus. So let's dive in!

How to Start a Biology Research Paper

When commencing a biology research paper, your first task is to select a topic that interests both you and your readers. The topic should be relevant to the study of biology and present opportunities for you to showcase your findings. A well-chosen topic will make the research process smoother and help you craft a paper that resonates with your audience. Remember, the success of your paper largely depends on your initial groundwork, so make it count. Check out recent science journals for research publication inspiration.

How to Structure a Biology Research Paper

After picking your topic, the next step is planning the structure of your biology research paper. The structure should comprise of an introduction, body, and conclusion. It's crucial to create an outline before diving into the writing process, as this helps to organize your thoughts and findings. The outline should cover each section of the paper, from the introduction to the conclusion, including the arguments, experimental procedures, and vital information you intend to include.

Understanding the Biology Research Paper Outline

A biology research paper outline serves as your blueprint. It guides you through the writing process, making sure you don't drift off-topic. Your outline should include the thesis statement, the main points for your arguments, the experimental procedures to be followed, and the data you'll collect. It's also the space to decide how you'll present your research findings to your readers in a comprehensible manner. With a well-prepared outline, you'll find that writing your paper becomes significantly easier.

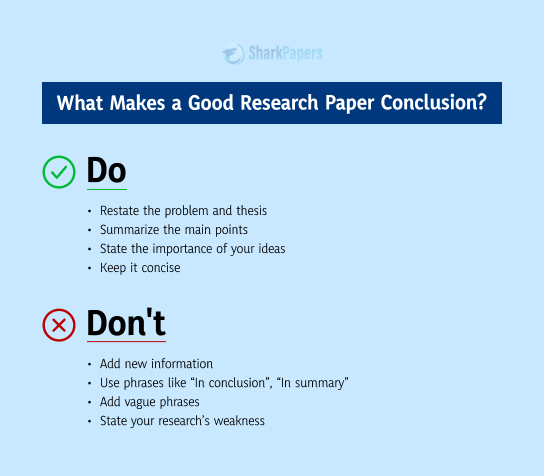

How to End a Biology Research Paper

Concluding a biology research paper effectively involves summarizing your key findings and stating their implications. It's not just about restating what you've already said; it's a final opportunity to leave a lasting impression on your audience. Your conclusion should reiterate your thesis statement and provide a summary of the key points made in the paper's body. It's essential to also discuss the significance of your findings and how they contribute to existing scientific research.

Submitting to Science Journals for Research Publication

After completing your paper, the final step is to submit it to reputable science journals for research publication. Peer-reviewed journals are the gold standard in the scientific community. Your paper will undergo rigorous review, ensuring it meets the academic and scientific criteria of the journal. The process may require revisions, but don't be disheartened. These are steps to ensure that your research is robust, accurate, and worthy of academic recognition.

A Comprehensive Research

The term 'comprehensive research' implies the exhaustive and detailed nature of your study. Make sure your research is thorough and leaves no stone unturned. This will lend credibility and depth to your biology research paper, enhancing its value in academic circles.

Introduction of Biology Research Paper

The introduction sets the tone for your biology research paper. It's where you outline the objective, the research question, and the thesis statement. Make it engaging enough to captivate your readers but academic enough to convey the paper’s significance.

Body of Biology Research Paper

The body is where you present your findings, experimental procedures, and analysis. Structure it logically, using headings and subheadings to guide the reader through your arguments and data. Consistency and clarity are key to keeping your audience engaged.

Conclusion of Biology Research Paper

In your conclusion, make sure to tie all your findings back to your research question and thesis statement. A compelling conclusion will summarize the research, restate the importance of your study, and suggest potential avenues for future research.

Dos and Don'ts

- Do conduct a thorough literature review.

- Do create an exhaustive outline.

- Don't use jargon without explaining it.

- Don't ignore formatting guidelines.

Final Thoughts

Completing a biology research paper is a complex yet rewarding academic exercise. It's a chance to contribute to the scientific community and showcase your ability to conduct research, analyze data, and articulate your findings. With careful planning, diligent research, and thoughtful writing, you can create a paper that not only meets academic standards but also serves as a meaningful addition to existing scientific literature.

Useful Resources: https://techthanos.com/ways-of-using-chatgpt-in-the-classroom/

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Getting started with your research paper outline

Levels of organization for a research paper outline

First level of organization, second level of organization, third level of organization, fourth level of organization, tips for writing a research paper outline, research paper outline template, my research paper outline is complete: what are the next steps, frequently asked questions about a research paper outline, related articles.

The outline is the skeleton of your research paper. Simply start by writing down your thesis and the main ideas you wish to present. This will likely change as your research progresses; therefore, do not worry about being too specific in the early stages of writing your outline.

A research paper outline typically contains between two and four layers of organization. The first two layers are the most generalized. Each layer thereafter will contain the research you complete and presents more and more detailed information.

The levels are typically represented by a combination of Roman numerals, Arabic numerals, uppercase letters, lowercase letters but may include other symbols. Refer to the guidelines provided by your institution, as formatting is not universal and differs between universities, fields, and subjects. If you are writing the outline for yourself, you may choose any combination you prefer.

This is the most generalized level of information. Begin by numbering the introduction, each idea you will present, and the conclusion. The main ideas contain the bulk of your research paper 's information. Depending on your research, it may be chapters of a book for a literature review , a series of dates for a historical research paper, or the methods and results of a scientific paper.

I. Introduction

II. Main idea

III. Main idea

IV. Main idea

V. Conclusion

The second level consists of topics which support the introduction, main ideas, and the conclusion. Each main idea should have at least two supporting topics listed in the outline.

If your main idea does not have enough support, you should consider presenting another main idea in its place. This is where you should stop outlining if this is your first draft. Continue your research before adding to the next levels of organization.

- A. Background information

- B. Hypothesis or thesis

- A. Supporting topic

- B. Supporting topic

The third level of organization contains supporting information for the topics previously listed. By now, you should have completed enough research to add support for your ideas.

The Introduction and Main Ideas may contain information you discovered about the author, timeframe, or contents of a book for a literature review; the historical events leading up to the research topic for a historical research paper, or an explanation of the problem a scientific research paper intends to address.

- 1. Relevant history

- 2. Relevant history

- 1. The hypothesis or thesis clearly stated

- 1. A brief description of supporting information

- 2. A brief description of supporting information

The fourth level of organization contains the most detailed information such as quotes, references, observations, or specific data needed to support the main idea. It is not typical to have further levels of organization because the information contained here is the most specific.

- a) Quotes or references to another piece of literature

- b) Quotes or references to another piece of literature

Tip: The key to creating a useful outline is to be consistent in your headings, organization, and levels of specificity.

- Be Consistent : ensure every heading has a similar tone. State the topic or write short sentences for each heading but avoid doing both.

- Organize Information : Higher levels of organization are more generally stated and each supporting level becomes more specific. The introduction and conclusion will never be lower than the first level of organization.

- Build Support : Each main idea should have two or more supporting topics. If your research does not have enough information to support the main idea you are presenting, you should, in general, complete additional research or revise the outline.

By now, you should know the basic requirements to create an outline for your paper. With a content framework in place, you can now start writing your paper . To help you start right away, you can use one of our templates and adjust it to suit your needs.

After completing your outline, you should:

- Title your research paper . This is an iterative process and may change when you delve deeper into the topic.

- Begin writing your research paper draft . Continue researching to further build your outline and provide more information to support your hypothesis or thesis.

- Format your draft appropriately . MLA 8 and APA 7 formats have differences between their bibliography page, in-text citations, line spacing, and title.

- Finalize your citations and bibliography . Use a reference manager like Paperpile to organize and cite your research.

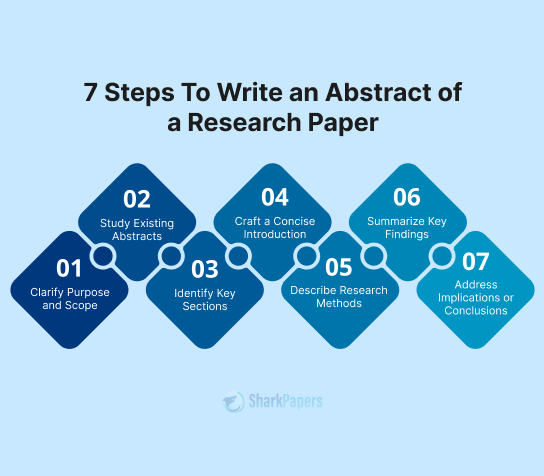

- Write the abstract, if required . An abstract will briefly state the information contained within the paper, results of the research, and the conclusion.

An outline is used to organize written ideas about a topic into a logical order. Outlines help us organize major topics, subtopics, and supporting details. Researchers benefit greatly from outlines while writing by addressing which topic to cover in what order.

The most basic outline format consists of: an introduction, a minimum of three topic paragraphs, and a conclusion.

You should make an outline before starting to write your research paper. This will help you organize the main ideas and arguments you want to present in your topic.

- Consistency: ensure every heading has a similar tone. State the topic or write short sentences for each heading but avoid doing both.

- Organization : Higher levels of organization are more generally stated and each supporting level becomes more specific. The introduction and conclusion will never be lower than the first level of organization.

- Support : Each main idea should have two or more supporting topics. If your research does not have enough information to support the main idea you are presenting, you should, in general, complete additional research or revise the outline.

How Can You Create a Well Planned Research Paper Outline

You are staring at the blank document, meaning to start writing your research paper . After months of experiments and procuring results, your PI asked you to write the paper to publish it in a reputed journal. You spoke to your peers and a few seniors and received a few tips on writing a research paper, but you still can’t plan on how to begin!

Writing a research paper is a very common issue among researchers and is often looked upon as a time consuming hurdle. Researchers usually look up to this task as an impending threat, avoiding and procrastinating until they cannot delay it anymore. Seeking advice from internet and seniors they manage to write a paper which goes in for quite a few revisions. Making researchers lose their sense of understanding with respect to their research work and findings. In this article, we would like to discuss how to create a structured research paper outline which will assist a researcher in writing their research paper effectively!

Publication is an important component of research studies in a university for academic promotion and in obtaining funding to support research. However, the primary reason is to provide the data and hypotheses to scientific community to advance the understanding in a specific domain. A scientific paper is a formal record of a research process. It documents research protocols, methods, results, conclusion, and discussion from a research hypothesis .

Table of Contents

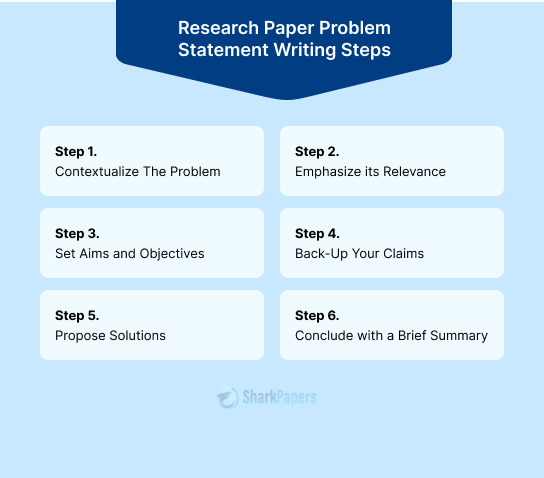

What Is a Research Paper Outline?

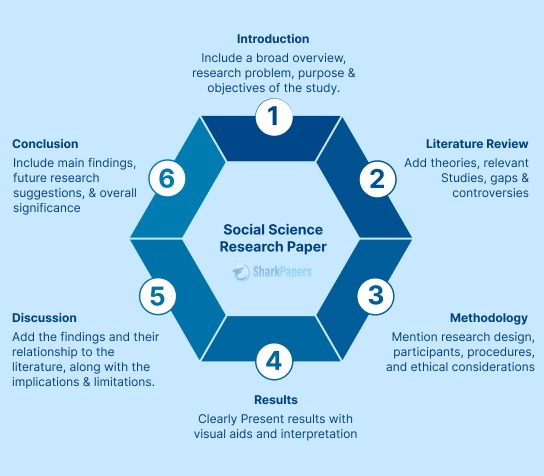

A research paper outline is a basic format for writing an academic research paper. It follows the IMRAD format (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion). However, this format varies depending on the type of research manuscript. A research paper outline consists of following sections to simplify the paper for readers. These sections help researchers build an effective paper outline.

1. Title Page

The title page provides important information which helps the editors, reviewers, and readers identify the manuscript and the authors at a glance. It also provides an overview of the field of research the research paper belongs to. The title should strike a balance between precise and detailed. Other generic details include author’s given name, affiliation, keywords that will provide indexing, details of the corresponding author etc. are added to the title page.

2. Abstract

Abstract is the most important section of the manuscript and will help the researcher create a detailed research paper outline . To be more precise, an abstract is like an advertisement to the researcher’s work and it influences the editor in deciding whether to submit the manuscript to reviewers or not. Writing an abstract is a challenging task. Researchers can write an exemplary abstract by selecting the content carefully and being concise.

3. Introduction

An introduction is a background statement that provides the context and approach of the research. It describes the problem statement with the assistance of the literature study and elaborates the requirement to update the knowledge gap. It sets the research hypothesis and informs the readers about the big research question.

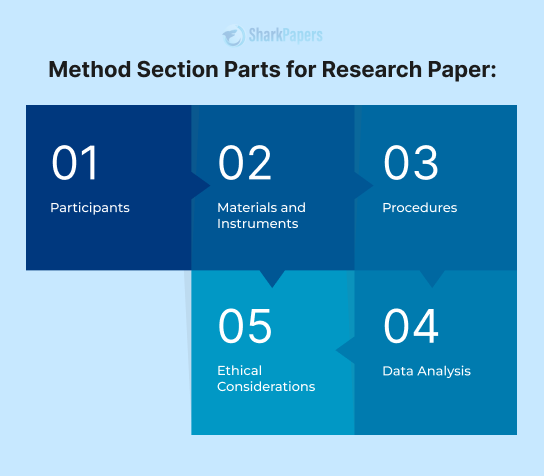

This section is usually named as “Materials and Methods”, “Experiments” or “Patients and Methods” depending upon the type of journal. This purpose provides complete information on methods used for the research. Researchers should mention clear description of materials and their use in the research work. If the methods used in research are already published, give a brief account and refer to the original publication. However, if the method used is modified from the original method, then researcher should mention the modifications done to the original protocol and validate its accuracy, precision, and repeatability.

It is best to report results as tables and figures wherever possible. Also, avoid duplication of text and ensure that the text summarizes the findings. Report the results with appropriate descriptive statistics. Furthermore, report any unexpected events that could affect the research results, and mention complete account of observations and explanations for missing data (if any).

6. Discussion

The discussion should set the research in context, strengthen its importance and support the research hypothesis. Summarize the main results of the study in one or two paragraphs and show how they logically fit in an overall scheme of studies. Compare the results with other investigations in the field of research and explain the differences.

7. Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements identify and thank the contributors to the study, who are not under the criteria of co-authors. It also includes the recognition of funding agency and universities that award scholarships or fellowships to researchers.

8. Declaration of Competing Interests

Finally, declaring the competing interests is essential to abide by ethical norms of unique research publishing. Competing interests arise when the author has more than one role that may lead to a situation where there is a conflict of interest.

Steps to Write a Research Paper Outline

- Write down all important ideas that occur to you concerning the research paper .

- Answer questions such as – what is the topic of my paper? Why is the topic important? How to formulate the hypothesis? What are the major findings?

- Add context and structure. Group all your ideas into sections – Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion.

- Add relevant questions to each section. It is important to note down the questions. This will help you align your thoughts.

- Expand the ideas based on the questions created in the paper outline.

- After creating a detailed outline, discuss it with your mentors and peers.

- Get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to.

- The process of real writing begins.

Benefits of Creating a Research Paper Outline

As discussed, the research paper subheadings create an outline of what different aspects of research needs elaboration. This provides subtopics on which the researchers brainstorm and reach a conclusion to write. A research paper outline organizes the researcher’s thoughts and gives a clear picture of how to formulate the research protocols and results. It not only helps the researcher to understand the flow of information but also provides relation between the ideas.

A research paper outline helps researcher achieve a smooth transition between topics and ensures that no research point is forgotten. Furthermore, it allows the reader to easily navigate through the research paper and provides a better understanding of the research. The paper outline allows the readers to find relevant information and quotes from different part of the paper.

Research Paper Outline Template

A research paper outline template can help you understand the concept of creating a well planned research paper before beginning to write and walk through your journey of research publishing.

1. Research Title

A. Background i. Support with evidence ii. Support with existing literature studies

B. Thesis Statement i. Link literature with hypothesis ii. Support with evidence iii. Explain the knowledge gap and how this research will help build the gap 4. Body

A. Methods i. Mention materials and protocols used in research ii. Support with evidence

B. Results i. Support with tables and figures ii. Mention appropriate descriptive statistics

C. Discussion i. Support the research with context ii. Support the research hypothesis iii. Compare the results with other investigations in field of research

D. Conclusion i. Support the discussion and research investigation ii. Support with literature studies

E. Acknowledgements i. Identify and thank the contributors ii. Include the funding agency, if any

F. Declaration of Competing Interests

5. References

Download the Research Paper Outline Template!

Have you tried writing a research paper outline ? How did it work for you? Did it help you achieve your research paper writing goal? Do let us know about your experience in the comments below.

Downloadable format shared which is great. 🙂

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

- AI in Academia

- Trending Now

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Setting Rationale in Research: Cracking the code for excelling at research

Mitigating Survivorship Bias in Scholarly Research: 10 tips to enhance data integrity

The Power of Proofreading: Taking your academic work to the next level

Facing Difficulty Writing an Academic Essay? — Here is your one-stop solution!

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

Research Paper Writing Guides

Biology Research Paper

Last updated on: May 13, 2024

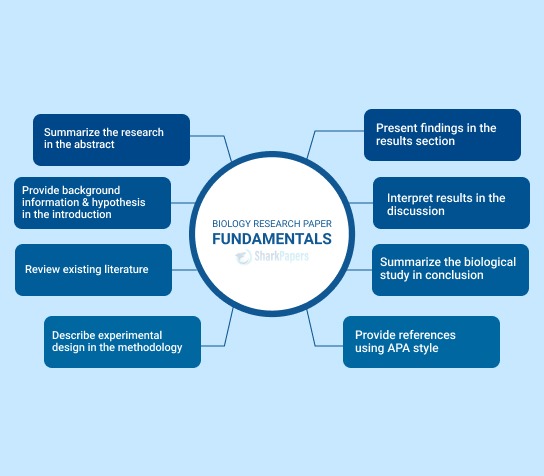

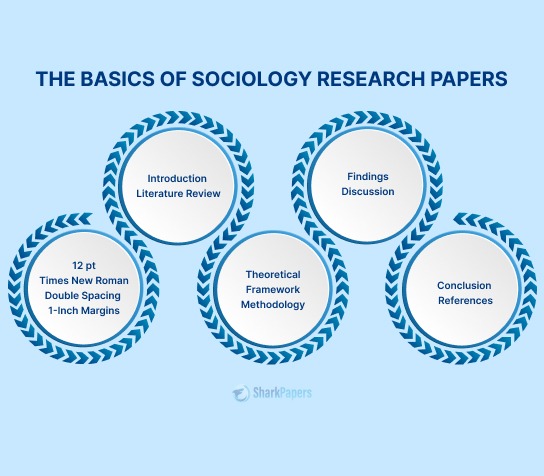

Understanding the Basics of Biology Research Papers

By: Barbara P.

12 min read

Reviewed By:

Published on: Mar 27, 2024

From structuring to finding suitable topics, many research students struggle with understanding biology research papers. The lack of guidance can lead to confusion and frustration, which hinders academic progress and makes it difficult to craft quality research papers .

Whether you're a high school student or a college researcher, this blog has all the essentials you need to craft a stellar biology research paper. We'll walk you through the basics of structure, formatting, examples, and topics.

Let's explore biology papers together in order to enrich your academic experience.

On this Page

What is a Biology Research Paper?

A biology research paper explores living organisms, their habitat, structure, and more. These papers contribute to the collective knowledge of biology and are typically written by scientists, researchers, or scholars.

Biology research papers cover a wide range of topics, including molecular biology, genetics, ecology, evolution, physiology, and more.

Just like other types of research papers , the content is based on empirical evidence obtained through experiments, observations, or analyses.

In these research papers, you analyze specific issues, support claims with evidence, and discuss unique findings. Their primary goal is to broaden the understanding of the biological sciences and contribute to the ongoing development of the field.

How to Structure Your Biology Research Paper?

Similar to structuring other types of research papers, your biology paper requires careful organization to communicate your findings effectively. Here is the standard biology research paper outline you should follow:

- Title of the paper: Be concise and descriptive.

- Author(s) name(s): List all contributors.

- Affiliation(s): Include academic institutions.

- Date: When the paper was completed or submitted.

- For the abstract section , summarize your research question, methods, results, and conclusions in 150–250 words.

- Highlight the significance of your findings within the field of biology.

Introduction

- In the research paper introduction , provide background information on the topic, including relevant biological concepts and previous research.

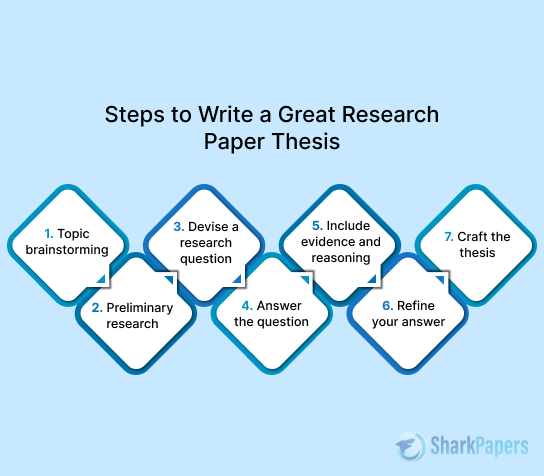

- Clearly state your research question or hypothesis.

- Explain the importance of your research within the broader context of biology.

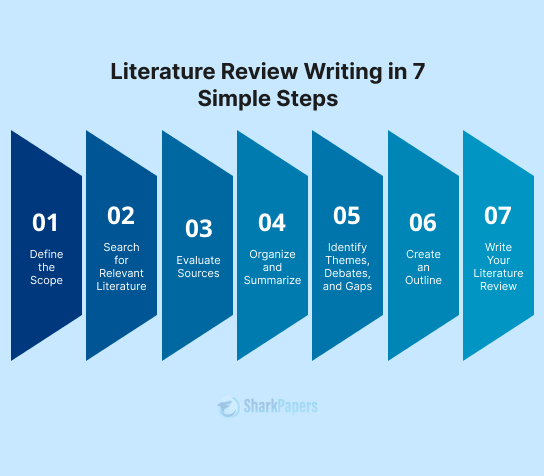

Literature Review

- Review existing literature related to your research topic when writing the literature review .

- Discuss key findings, controversies, and gaps in knowledge.

- Justify the need for your research based on previous studies.

- In the method section , describe the experimental design or data collection technique in detail.

- Explain how you manipulated variables or conducted observations.

- Provide sufficient information for others to replicate your study.

Results

- Present your findings objectively and concisely in the results section .

- Use tables, graphs, or figures to illustrate data effectively.

- Include statistical analyses if applicable.

- To write the discussion section , interpret your results in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

- Discuss any unexpected findings and potential sources of error.

- Compare your results with previous studies and theories.

- Explore the broader implications of your findings within the field of biology.

- Summarize the main findings of your research in the conclusion section .

- Restate your research question or hypothesis and whether it was supported.

- Suggest directions for future research based on your findings.

- At the end, you should list all sources cited in your paper, using a consistent citation style throughout.

Formatting Your Biology Research Paper

For writing a biology paper, there are no specific formatting rules. Having said that, the APA style is commonly used for scientific research papers. You can get guidance from our APA research paper format guide to write down your biology research paper effectively.

Biology Research Paper Examples

To understand biological research papers better, you should take a look at some examples. Here are some:

Biology Research Paper Introduction Example

If you are interested in the above paper, you can read the complete biology research paper example here .

If you're looking for valuable resources and guidance on biology research papers, consider exploring the resources available through the Penn Foster Biology Research Paper Library.

Biology Research Paper Example High School PDF

Biology Research Paper Example PDF

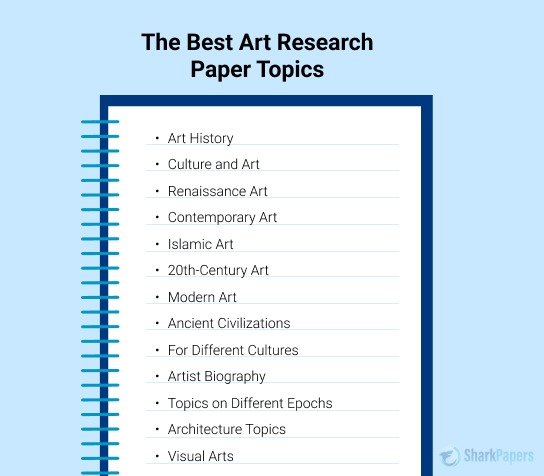

Interesting Biology Research Paper Topics

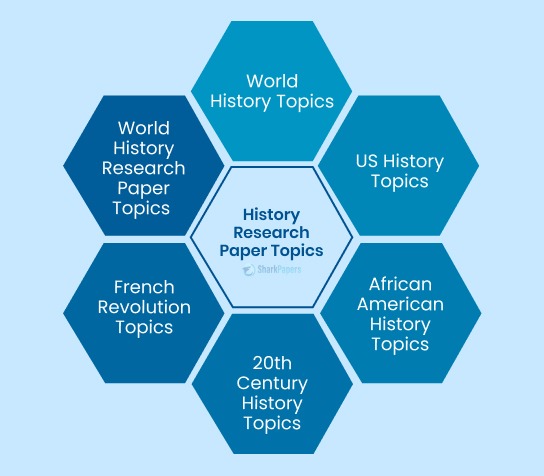

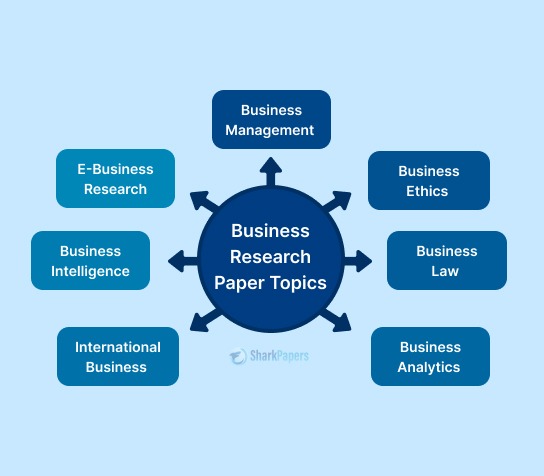

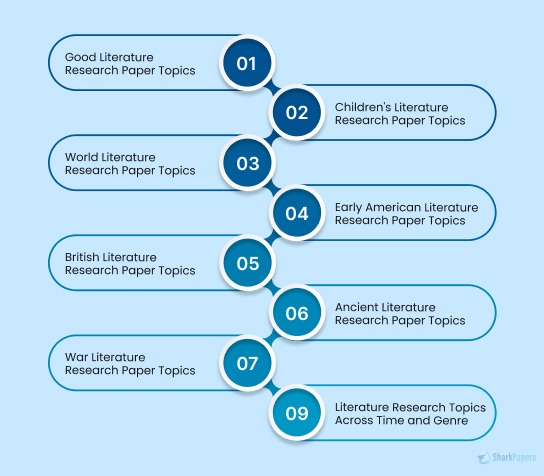

Here are some good topics to write a biology research paper on.

Biology Research Paper Topics for College Students

- Investigate the Impact of Biodiversity Loss on Ecosystem Stability.

- Explore the Evolutionary Adaptations of Plants to Environmental Stress.

- Examine the Role of Microorganisms in Soil Fertility and Nutrient Cycling.

- Analyze the Genetic Diversity of Endangered Species and Its Conservation Implications.

- Study the Ecological Effects of Invasive Species on Native Ecosystems.

- Investigate the Relationship Between Climate Change and Species Distribution Patterns.

- Explore the Ecological Significance of Keystone Species in Natural Communities.

- Examine the Effects of Pollution on Aquatic Ecosystems and Biodiversity.

- Analyze the Impact of Habitat Fragmentation on Wildlife Populations.

- Investigate the Role of Ecological Restoration in Ecosystem Rehabilitation and Conservation.

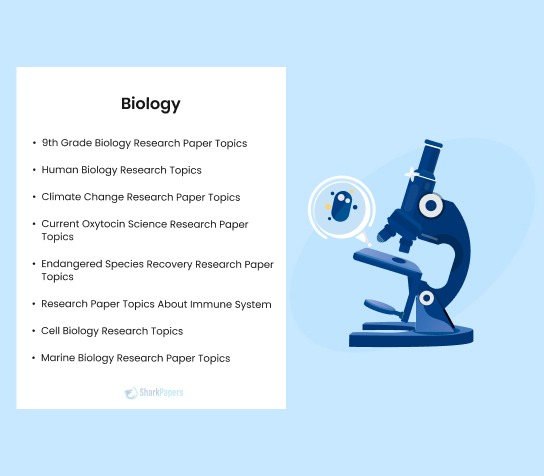

Marine Biology Research Paper Topics

- Explore the Effects of Ocean Acidification on Marine Invertebrates.

- Examine the Relationship Between Marine Microorganisms and Climate Change.

- Investigate the Impact of Oil Spills on Coastal Marine Ecosystems.

- Analyze the Adaptation Strategies of Deep-Sea Creatures to Extreme Environments.

- Study the Effects of Noise Pollution on Marine Mammals.

- Explore the Role of Seagrass Beds in Coastal Carbon Sequestration.

- Examine the Genetic Diversity of Coral Reefs and Its Implications for Conservation.

- Investigate the Ecological Importance of Polar Marine Ecosystems in a Warming Climate.

- Analyze the Behavioral Ecology of Marine Predators in Different Oceanic Regions.

- Explore the Dynamics of Harmful Algal Blooms and Their Impact on Marine Life.

Cancer Biology Research Paper Topics

- Explore the Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Cancer Progression.

- Examine the Molecular Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in Cancer Cells.

- Investigate the Potential of Immunotherapy in Treating Solid Tumors.

- Analyze the Epigenetic Regulation of Gene Expression in Cancer Development.

- Study the Tumor Heterogeneity and Its Implications for Personalized Medicine.

- Explore the Crosstalk Between Cancer Cells and the Immune System.

- Examine the Role of Cancer Stem Cells in Tumor Initiation and Progression.

- Investigate the Impact of Metabolic Reprogramming on Cancer Cell Growth.

- Analyze the Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Cancer Pathogenesis.

- Explore the Development of Targeted Therapies Against Specific Cancer Signaling Pathways.

Molecular Biology Research Paper Topics

- Explore the Mechanisms of DNA Replication and Repair in Eukaryotic Cells.

- Examine the Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Gene Regulation and Genome Stability.

- Investigate the Molecular Basis of Cellular Senescence and Aging.

- Analyze the Regulation of Apoptosis and Its Implications in Disease States.

- Study the Molecular Mechanisms of Chromatin Remodeling and Epigenetic Regulation.

- Explore the Dynamics of Protein Folding and Misfolding in Neurodegenerative Diseases.

- Examine the Role of Autophagy in Cellular Homeostasis and Disease Pathogenesis.

- Investigate the Molecular Basis of Signal Transduction Pathways in Cellular Signaling.

- Analyze the Role of MicroRNAs in Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation.

- Explore the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Cancer Metastasis and Invasion.

Cell Biology Research Paper Topics

- Explore the Role of Organelle Dynamics in Cellular Function and Homeostasis.

- Examine the Molecular Mechanisms of Cell Division and Mitotic Regulation.

- Investigate the Role of Endocytic Pathways in Cellular Trafficking and Signaling.

- Analyze the Molecular Basis of Cell-Cell Adhesion and Intercellular Communication.

- Study the Regulation of Cell Cycle Progression and Checkpoints in Response to DNA Damage.

- Explore the Dynamics of Cytoskeletal Elements in Cell Morphology and Motility.

- Examine the Role of Cellular Membrane Dynamics in Vesicle Trafficking and Fusion.

- Investigate the Molecular Mechanisms of Cell Fate Determination and Differentiation.

- Analyze the Role of Autophagy in Cellular Homeostasis and Stress Response.

- Explore the Molecular Basis of Cellular Senescence and Aging.

Do’s and Don'ts of Biology Research Papers

When writing biology research papers, there are some important do's and don'ts that you should always take care of. Let’s explore them.

Do Use Clear Language: Use simple and straightforward language to explain your ideas and findings. Avoid jargon and technical terms unless necessary.

Do Provide Clear Definitions: Define any specialized terms or concepts that might be unfamiliar to your readers. This helps ensure that your paper is accessible to a wider audience.

Do Organize Your Paper Clearly: Structure your paper with clear headings and subheadings to help readers navigate through your research easily. A well-organized paper improves readability and comprehension.

Do Support Your Claims with Evidence: Back up your arguments and findings with evidence from reliable sources, such as peer-reviewed journals and reputable textbooks. This strengthens the credibility of your research.

Do Incorporate Articles Published Across Time: Include both recent articles published in scientific journals and classic works from the past. This provides a comprehensive understanding of your research topic's historical context and development.

Do Proofread Your Paper: Before submitting your paper, carefully proofread it for grammatical errors, typos, and inconsistencies. A well-written paper demonstrates professionalism and enhances the clarity of your message.

Don'ts

Don't Plagiarize: Avoid copying text or ideas from other sources without proper attribution. Plagiarism is unethical and can have serious consequences for your academic or professional reputation.

Don't Overuse Technical Jargon: While some technical terms are necessary for biology papers, avoid overloading your paper with too much specialized language. This can confuse readers who are not familiar with the terminology.

Don't Make Unsupported Claims: Make sure that all statements and conclusions in your paper are supported by evidence. Avoid making unsubstantiated claims or drawing conclusions that are not backed by your research findings.

Don't Use Ambiguous Language: Be precise and specific in your writing to avoid ambiguity. Clearly define terms and concepts to prevent misinterpretation by your readers.

Don't Ignore Contradictory Evidence: Acknowledge and address contradictory evidence or alternative interpretations that may challenge your hypotheses or conclusions. Ignoring conflicting data can undermine the credibility of your research.

Don't Wait Until the Last Minute: Start working on your paper well in advance of the deadline to allow ample time for research, writing, and revisions. Procrastination can lead to rushed work and lower-quality output.

By following these dos and don'ts, you can write a biology research paper that effectively communicates your ideas and findings in a clear and accessible manner.

To sum up, in this blog, we discussed the essentials of biology research papers, including their structure and what they cover. Our blog also discussed various topics in biology like marine, cancer, molecular, and cell biology, which can interest college students.

For those in need of additional support with their biology research papers, SharkPapers.com is a paper writing service online that is always ready to provide writing assistance. Our team of professionals can help navigate the complexities of biology research paper writing.

Remember, with the right resources and assistance, tackling biology research papers can be a rewarding and enlightening experience. Don't hesitate to reach out to our service, we can help write your research papers with ease!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a good topic for a biology research paper.

A compelling topic for a biology research paper could be “The Impact of CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing on Genetic Diseases.” This topic allows exploration into the revolutionary gene-editing technology and its potential to treat or prevent genetic disorders, offering insights into the ethical considerations and future implications of genomic interventions.

A compelling topic for a biology research paper could be “The Impact of CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing on Genetic Diseases.” This topic allows exploration into the revolutionary gene-editing technology and its potential to treat or prevent genetic disorders, offering insights into the ethical considerations and future implications of genomic interventions. How long should a biology research paper should be?

Medical and biology research papers and dissertations are typically around 10,000 to 15,000 words long. They cover in-depth studies on important topics, providing valuable information to the scientific community.

What can I research in biology?

- Genetics: Study of genes and heredity.

- Ecology: Interactions between organisms and their environment.

- Cell Biology: Structure and function of cells.

- Evolution: Mechanisms and patterns of species change.

- Physiology: Functions and processes of living organisms.

- Microbiology: Study of microscopic organisms.

- Biotechnology: Application of biological principles in various fields.

- Developmental Biology: Growth and development of organisms.

- Neuroscience: Study of the nervous system.

- Molecular Biology: Study of biological molecules.