- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What are New Year festivals?

- Why does the new year begin on January 1?

- How is New Year’s Eve celebrated?

- Why does a ball drop on New Year’s Eve?

Lunar New Year

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Al Jazeera - What is the Lunar New Year? Traditions and celebrations explained

- China Internet Information Center - The Spring Festival

- CNN - Enter the Year of the Dragon: A 2024 guide to Lunar New Year

- Lunar New Year - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Lunar New Year - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Lunar New Year , festival typically celebrated in China and other Asian countries that begins with the first new moon of the lunar calendar and ends on the first full moon of the lunar calendar, 15 days later. The lunar calendar is based on the cycles of the moon, so the dates of the holiday vary slightly from year to year, beginning some time between January 21 and February 20 according to Western calendars. Approximately 10 days before the beginning of the new lunar year, houses are thoroughly cleaned to remove any bad luck that might be lingering inside, a custom called “sweeping of the grounds.” Traditionally, New Year’s eve and New Year’s day are reserved for family celebrations, including religious ceremonies honouring ancestors. Also on New Year’s day, family members receive red envelopes ( lai see ) containing small amounts of money. Dances and fireworks are prevalent throughout the holidays, culminating in the Lantern Festival , which is celebrated on the last day of the New Year’s celebrations. On this night colourful lanterns light up the houses, and traditional foods such as yuanxiao (sticky rice balls that symbolize family unity), fagao (prosperity cake), and yusheng (raw fish and vegetable salad) are served.

The origins of the Lunar New Year festival are thousands of years old and are steeped in legends . One legend is that of Nian , a hideous beast believed to feast on human flesh on New Year’s day. Because Nian feared the colour red, loud noises, and fire, red paper decorations were pasted to doors, lanterns were burned all night, and firecrackers were lit to frighten the beast away.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Lunar New Year 2024

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 9, 2024 | Original: February 4, 2010

Lunar New Year is one of the most important celebrations of the year among East and Southeast Asian cultures, including Chinese, Vietnamese and Korean communities, among others. The New Year celebration is celebrated for multiple days—not just one day as in the Gregorian calendar’s New Year.

This Lunar New Year, which begins on February 10, is the Year of the Dragon.

China’s Lunar New Year is known as the Spring Festival or Chūnjié in Mandarin, while Koreans call it Seollal and Vietnamese refer to it as Tết .

Tied to the lunar calendar, the holiday began as a time for feasting and to honor household and heavenly deities, as well as ancestors. The New Year typically begins with the first new moon that occurs between the end of January and spans the first 15 days of the first month of the lunar calendar—until the full moon arrives.

Zodiac Animals

Each year in the Lunar calendar is represented by one of 12 zodiac animals included in the cycle of 12 stations or “signs” along the apparent path of the sun through the cosmos.

The 12 zodiac animals are the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog and pig. In addition to the animals, five elements of earth, water, fire, wood and metal are also mapped onto the traditional lunar calendar. Each year is associated with an animal that corresponds to an element.

The year 2024 is slated to be the year of the dragon—an auspicious symbol of power, wisdom and good fortune. The year of the dragon last came up in 2012.

Lunar New Year Foods and Traditions

Each culture celebrates the Lunar New Year differently with various foods and traditions that symbolize prosperity, abundance and togetherness. In preparation for the Lunar New Year, houses are thoroughly cleaned to rid them of inauspicious spirits, which might have collected during the old year. Cleaning is also meant to open space for good will and good luck.

Some households hold rituals to offer food and paper icons to ancestors. Others post red paper and banners inscribed with calligraphy messages of good health and fortune in front of, and inside, homes. Elders give out envelopes containing money to children. Foods made from glutinous rice are commonly eaten, as these foods represent togetherness. Other foods symbolize prosperity, abundance and good luck.

Chinese New Year is thought to date back to the Shang Dynasty in the 14th century B.C. Under Emperor Wu of Han (140–87 B.C.), the tradition of carrying out rituals on the first day of the Chinese calendar year began.

“This holiday has ancient roots in China as an agricultural society. It was the occasion to celebrate the harvest and worship the gods and ask for good harvests in times to come," explains Yong Chen, a scholar in Asian American Studies.

During the Cultural Revolution in 1967, official Chinese New Year celebrations were banned in China. But Chinese leaders became more willing to accept the tradition. In 1996, China instituted a weeklong vacation during the holiday—now officially called Spring Festival—giving people the opportunity to travel home and to celebrate the new year.

Did you know? San Francisco, California, claims its Chinese New Year parade is the biggest celebration of its kind outside of Asia. The city has hosted a Chinese New Year celebration since the Gold Rush era of the 1860s, a period of large-scale Chinese immigration to the region.

Today, the holiday prompts major travel as hundreds of millions hit the roads or take public transportation to return home to be with family.

Among Chinese cultures, fish is typically included as a last course of a New Year’s Eve meal for good luck. In the Chinese language, the pronunciation of “fish” is the same as that for the word “surplus” or “abundance.” Chinese New Year’s meals also feature foods like glutinous rice ball soup, moon-shaped rice cakes (New Year’s cake) and dumplings ( Jiǎozi in Mandarin). Sometimes, a clean coin is tucked inside a dumpling for good luck.

The holiday concludes with the Lantern Festival, which is celebrated on the last day of New Year's festivities. Parades, dances, games and fireworks mark the finale of the holiday.

In Vietnamese celebrations of the holiday, homes are decorated with kumquat trees and flowers such as peach blossoms, chrysanthemums, orchids and red gladiolas. As in China, travel is heavy during the holiday as family members gather to mark the new year.

Families feast on five-fruit platters to honor their ancestors. Tết celebrations can also include bánh chưng , a rice cake made with mung beans, pork, and other ingredients wrapped in bamboo leaves. Snacks called mứt tết are commonly offered to guests. These sweet bites are made from dried fruits or roasted seeds mixed with sugar.

In Korea, official Lunar New Year celebrations were halted from 1910-1945. This was when the Empire of Japan annexed Korea and ruled it as a colony until the end of World War II . Celebrations of Seollal were officially revived in 1989, although many families had already begun observing the lunar holiday. North Korea began celebrating the Lunar New Year according to the lunar calendar in 2003. Before then, New Year's was officially only observed on January 1. North Koreans are also encouraged to visit statues of founder Kim Il Sung, and his son Kim Jong Il, during the holidays and provide an offering of flowers.

Among both North and South Koreans, sliced rice cake soup ( tteokguk ) is prepared to mark the Lunar New Year holiday. The clear broth and white rice cakes of tteokguk are believed to symbolize starting the year with a clean mind and body. Rather than giving money in red envelopes, as in China and Vietnam, elders give New Year's money in white and patterned envelopes.

Traditionally, families gather from all over Korea at the house of their oldest male relative to pay their respects to both ancestors and elders. Travel is less common in North Korea and families tend to mark the holiday at home.

Lunar New Year Greetings

Cultures celebrating Lunar New Year have different ways of greeting each other during the holiday. In Mandarin, a common way to wish family and close friends a happy New Year is “ Xīnnián hǎo ,” meaning “New Year Goodness” or “Good New Year.” Another greeting is “ Xīnnián kuàilè, ” meaning "Happy New Year."

Traditional greetings during Tết in Vietnam are “Chúc Mừng Năm Mới” (Happy New Year) and “Cung Chúc Tân Xuân” (gracious wishes of the new spring). For Seollal, South Koreans commonly say "Saehae bok mani badeuseyo” (May you receive lots of luck in the new year), while North Koreans say "Saehaereul chuckhahabnida” (Congratulations on the new year).

— huiying b. chan , Research and Policy Analyst on the Education Justice Research and Organizing Collaborative team at the New York University Metro Center, edited this report.

"Lunar New Year origins, customs explained," by Laura Rico, University of California, Irvine , February 19, 2015.

"Everything you need to know about Vietnamese Tết," Vietnam Insider , December 3, 2020.

"Seollal, Korean Lunar New Year," by Brendan Pickering, Asia Society .

"The Origin of Chinese New Year," by Haiwang Yuan, Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR , February 1, 2016.

"The Lunar New Year: Rituals and Legends," Asia for Educators .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- HISTORY & CULTURE

Why Lunar New Year prompts the world’s largest annual migration

Observed by billions of people, the festival also known as Chinese New Year or Spring Festival is marked by themes of reunion and hope.

Celebrated around the world, it usually prompts the planet’s largest annual migration of people. And though it is known to some in the West as Chinese New Year , it isn’t just celebrated in China. Lunar New Year falls this year on February 10, 2024, kicking off the Year of the Dragon. It is traditionally a time for family reunions, plenty of food, and some very loud celebrations.

What is the Lunar New Year?

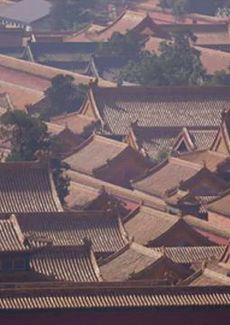

Modern China actually uses a Gregorian calendar like most of the rest of the world. Its holidays, however, are governed by its traditional lunisolar calendar , which may have been in use from as early as the 21st century B.C. When the newly founded Republic of China officially adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1912, its leaders rebranded the observation of the Lunar New Year as Spring Festival, as it is known in China today.

( Learn why some people celebrate Christmas in January. )

As its name suggests, the date of the lunar new year depends on the phase of the moon and varies from year to year. Each year in the lunar calendar is named one of the 12 animals in the Chinese zodiac , which are derived from ancient Chinese folklore. Repeating in a rotating basis, these animals are the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig.

Today, Spring Festival is celebrated in China and Hong Kong; Lunar New Year is also celebrated in South Korea, Tibet, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and places with large Chinese populations. Though the festival varies by country, it is dominated by themes of reunion and hope.

How Lunar New Year is celebrated

For Chinese people, Spring Festival lasts for 40 days and has multiple sub-festivals and rituals. The New Year itself is a seven-day-long state holiday, and on the eve of the new year, Chinese families traditionally celebrate with a massive reunion dinner. Considered the year’s most important meal, it is traditionally held in the house of the most senior family member.

( Learn about Lunar New Year with your kids. )

The holiday may be getting more modern, but millennia-old traditions are still held dear in China and other countries. In China, people customarily light firecrackers, which are thought to chase away the fearful monster Nian. (However, the tradition has been on the decline in recent years due to air pollution restrictions that have hit the fireworks industry hard.) The color red is used in clothing and decorations to ensure prosperity, and people exchange hongbao , red envelopes filled with lucky cash.

Meanwhile in Korea, people make rice cake soup and honor their ancestors during Seollal . And during Tet, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, flowers play an important role in the celebrations.

Lunar New Year has even spawned its own form of travel: During chunyun , or spring migration, hundreds of million people travel to their hometowns in China for family reunions and New Year’s celebrations. In past years, billions of travelers have taken to the road during the 40-day period. Known as the world’s largest human migration, chunyun regularly clogs already busy roads, trains and airports—proof of the holiday’s enduring significance for those who associate it with luck and love.

This story was originally published on January 2, 2020. It has been updated.

Related Topics

- HUMAN MIGRATION

- IMPERIAL CHINA

You May Also Like

This ancient festival is a celebration of springtime—and a brand new year

How the nation chooses its best and brightest Christmas trees

Why Swedish children celebrate Easter by dressing up as witches

Meet 5 of history's most elite fighting forces

How do we know when Ramadan starts and ends? It’s up to the moon.

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Race in America

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Destination Guide

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

The Origin and History of Chinese New Year: When Start and Why

Chinese New Year, also known as the Lunar New Year or the Spring Festival, is the most important among the traditional Chinese festivals. The origin of the Chinese New Year Festival can be traced back to about 3,500 years ago . Chinese New Year has evolved over a long period of time and its customs have undergone a long development process.

A Legend of the Origin of Chinese New Year

Like all traditional festivals in China, Chinese New Year is steeped with stories and myths. One of the most popular is about the mythical beast Nian (/nyen/), who ate livestock, crops, and even people on the eve of a new year. (It's interesting that Nian, the 'yearly beast', sounds the same as 'year' in Chinese.) To prevent Nian from attacking people and causing destruction, people put food at their doors for Nian.

It's said that a wise old man figured out that Nian was scared of loud noises (firecrackers) and the color red. Then, people put red lanterns and red scrolls on their windows and doors to stop Nian from coming inside, and crackled bamboo (later replaced by firecrackers) to scare Nian away. The monster Nian never showed up again. Click to learn more legends about the Chinese New Year .

Chinese New Year's Origin: In the Shang Dynasty

Chinese New Year has enjoyed a history of about 3,500 years. Its exact beginning is not recorded. Some people believe that Chinese New Year originated in the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BC), when people held sacrificial ceremonies in honor of gods and ancestors at the beginning or the end of each year.

Chinese Calendar "Year" Established: In the Zhou Dynasty

The term Nian ('year') first appeared in the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BC). It had become a custom to offer sacrifices to ancestors or gods, and to worship nature in order to bless harvests at the turn of the year.

Chinese New Year Date Was Fixed: In the Han Dynasty

The date of the festival, the first day of the first month in the Chinese lunar calendar, was fixed in the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD). Certain celebration activities became popular, such as burning bamboo to make a loud cracking sound. See when Chinese New Year is and how the date is determined .

In the Wei and Jin Dynasties

In the Wei and Jin dynasties (220–420), apart from worshiping gods and ancestors, people began to entertain themselves. The customs of a family getting together to clean their house, having dinner, and staying up late on New Year's Eve originated among common people.

More Chinese New Year Activities: From the Tang to Qing Dynasties

The prosperity of economies and cultures during the Tang , Song , and Qing dynasties accelerated the development of the Spring Festival. The customs during the festival became similar to those of modern times.

Setting off firecrackers, visiting relatives and friends, and eating dumplings became important parts of the celebration.

More entertaining activities arose , such as watching dragon and lion dances during the Temple Fair and enjoying lantern shows.

The function of the Spring Festival changed from a religious one to entertaining and social ones, more like that of today.

In Modern Times

In 1912, the government decided to abolish Chinese New Year and the lunar calendar, but adopted the Gregorian calendar instead and made January 1 the official start of the new year.

After 1949, Chinese New Year was renamed to the Spring Festival . It was listed as a nationwide public holiday.

Nowadays, many traditional activities are disappearing but new trends have been generated. CCTV (China Central Television) Spring Festival Gala, shopping online, WeChat red envelopes, fireworks shows, and overseas travel make Chinese New Year more interesting and colorful.

You Might Like

- Top 3 Interesting Chinese New Year Legends/Stories

- 10 Quick Facts about Lunar New Year

- How to Celebrate Chinese New Year: Top 18 Traditions

- Chinese New Year Taboos and Superstitions: 18 Things You Should Not Do

- 11-Day China Classic Tour

- 3-Week Must-See Places China Tour Including Holy Tibet

- 8-Day Beijing–Xi'an–Shanghai Private Tour

- How to Plan Your First Trip to China 2024/2025 — 7 Easy Steps

- 15 Best Places to Visit in China (2024)

- Best (& Worst) Times to Visit China, Travel Tips (2024/2025)

- How to Plan a 10-Day Itinerary in China (Best 5 Options)

- China Weather in January 2024: Enjoy Less-Crowded Traveling

- China Weather in March 2024: Destinations, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in April 2024: Where to Go (Smart Pre-Season Pick)

- China Weather in May 2024: Where to Go, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in June 2024: How to Benefit from the Rainy Season

- China Weather in July 2024: How to Avoid Heat and Crowds

- China Weather in August 2024: Weather Tips & Where to Go

- China Weather in September 2024: Weather Tips & Where to Go

- China Weather in October 2024: Where to Go, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in November 2024: Places to Go & Crowds

- China Weather in December 2024: Places to Go and Crowds

Get Inspired with Some Popular Itineraries

More Travel Ideas and Inspiration

Sign up to our newsletter.

Be the first to receive exciting updates, exclusive promotions, and valuable travel tips from our team of experts.

Why China Highlights

Where Can We Take You Today?

- Southeast Asia

- Japan, South Korea

- India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Sri lanka

- Central Asia

- Middle East

- African Safari

- Travel Agents

- Loyalty & Referral Program

- Privacy Policy

Address: Building 6, Chuangyi Business Park, 70 Qilidian Road, Guilin, Guangxi, 541004, China

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Lunar New Year traditions evolve in the Asian diaspora

Suzanne Nuyen

Chinese folk artists perform the lion dance at a temple fair to celebrate the Lunar New Year of Dragon in 2012 in Beijing, China. Feng Li/Getty Images hide caption

Chinese folk artists perform the lion dance at a temple fair to celebrate the Lunar New Year of Dragon in 2012 in Beijing, China.

Jan. 1 is an opportunity to start fresh for many people worldwide. They make resolutions to eat better, become healthier or take control of finances. Unfortunately, many people also abandon their resolutions by February. Luckily, it's around this time that I get a second chance to reflect on my year and set the tone for a new one.

This year, Feb. 10 marks the beginning of the Lunar New Year. It's one of the most important festivals in many Asian countries, including Vietnam , China , Korea as well as the Asian diaspora. The holiday prompts what is considered one of the world's largest annual human migrations as hundreds of millions of people travel back to their familial hometowns for the celebrations, which last up to two weeks. Certain foods are eaten only at this time of year. Often traditional costumes are worn. Celebrants gather to see parades and perform various rites and rituals with elders in order to guarantee a lucky year ahead.

This essay first appeared in the Up First newsletter. Subscribe here so you don't miss the next one. You'll get the news you need to start your day, plus a little fun every weekday and Sundays.

Here in the U.S., I only get to celebrate each Lunar New Year — or Tet, in Vietnamese — for one day each year, as it's not a federally recognized holiday. Nevertheless, my parents made sure we spent our time wisely. We would all take the day off and put on our traditional ao dai to go visit my grandparents. They'd give us red envelopes, called li xi, filled with "lucky" money — but only after we give well wishes to our elders. On the days leading up to the New Year, we thoroughly clean the house up and spend days making banh chung , a sticky rice cake filled with pork belly and mung bean. Tet was always a reflective day focused on mindfulness and setting ourselves up for another successful year.

Lion Dancers perform in China Town on the Lunar New Year on Jan. 26, 2009 in London, England. Dan Kitwood/Getty Images hide caption

Lion Dancers perform in China Town on the Lunar New Year on Jan. 26, 2009 in London, England.

It wasn't until my first Lunar New Year alone in college that I came to appreciate how grounding it can be to spend the first day of the year focused on joy and family.

Members of a family are busy making the traditional lunar new year banh chung , or rice cakes, for sale on the courtyard of their house in Chanh Khuc village in suburban Hanoi. Hoang Dinh Nam/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Members of a family are busy making the traditional lunar new year banh chung , or rice cakes, for sale on the courtyard of their house in Chanh Khuc village in suburban Hanoi.

This year's Tet is two weeks after my wedding date. My husband and I rested for just a few days after our nuptials before jumping in to preparations. In lieu of going home, we've invited the friends we've made in Washington to gather with us to enjoy traditional Vietnamese foods and learn about my traditions. We hope to continue this cultural exchange and share our love and luck with them for years to come.

Suzanne Nuyen and her then-fiancé celebrate the Lunar New Year on Jan. 22, 2023. Suzanne Nuyen/NPR hide caption

Suzanne Nuyen and her then-fiancé celebrate the Lunar New Year on Jan. 22, 2023.

Our celebration is just one example of how members of the Asian diaspora have evolved their Lunar New Year celebrations as they invite loved ones from other cultures to join in. Here's how more of NPR's current and former employees celebrate:

Kathleen Hoang, product manager, Salesforce

Hoang's parents are divorced, and she often splits her holiday between her mother, who is Korean, and her father, who is Chinese and Vietnamese. Her mother's family serves soju and Korean side dishes called banchan alongside photos of loved ones who have passed away. By moving the glasses and dishes around, it's as if her loved ones are enjoying a meal with her beyond the grave.

When she's with her father in D.C., Hoang's family does a deep clean the day before and wakes up early the next day to visit Vietnamese Buddhist temples in the area to pray and donate money. The family has a big meal in the evening. Food is laid out on an alter to honor and welcome ancestors. "New year is important to us because it's a fresh start for the year," her dad says. "Whatever we do on new year day sort of sets the tone for the rest of the year."

Kathleen Hoang, left, and her family celebrate the Lunar New Year in Fort Belvoir, Va., in 2020. Kathleen Hoang/NPR hide caption

Kathleen Hoang, left, and her family celebrate the Lunar New Year in Fort Belvoir, Va., in 2020.

That side of Hoang's family has always been close, and even during the pandemic they made efforts to stay in touch. For her, the Lunar New Year feels like any other regularly scheduled family gathering, albeit slightly more festive. "My dad's older sister makes sure we always meet together every month," she says. "I want to continue that tradition."

Wanyu Zhang, former brand director

Zhang is from Beijing. When she was living in China, her family would come together to make dumplings, hand out lucky money in red envelopes and watch the spring gala on China Central Television before enjoying fireworks at midnight. The Lunar New Year was one of the only times of year she could see her entire extended family. People usually get a week of vacation to celebrate. Special street markets are open all day and night for several weeks.

When Zhang moved to the U.S for college, she found a community of Chinese students to celebrate with, and was able to share the holiday with her non-Asian friends as well. "We built a new family," she said. "I sort of enjoyed it. We were doing something different." These days, it's become a tradition for her to invite a few friends over for a new year studio photo shoot with her boyfriend.

Wanyu Zhang, right, and her friends have a photo shoot to ring in the new year. Matailong Du/matailongdu.com hide caption

Wanyu Zhang, right, and her friends have a photo shoot to ring in the new year.

She keeps in touch with her family regularly, but the Lunar New Year is still a time for her to video chat with the whole family. They still watch the spring gala together virtually. "I want to keep that tradition no matter what," she said.

Zhang plans to stay in the U.S. for a long time, and she finds herself focusing more on the Western holidays that almost everyone celebrates, like Christmas. But she still finds small ways to celebrate and see her family. "It's a reminder that yes, this is still my holiday. But the definition is changing, and emotionally it's changing."

Gary Duong, senior marketing manager

Gary Duong, left and his husband Rick. Duong calls his parents and family every year for the Lunar New Year, but says his relationship with the holiday is complicated. Gary Duong/NPR hide caption

Gary Duong, left and his husband Rick. Duong calls his parents and family every year for the Lunar New Year, but says his relationship with the holiday is complicated.

Duong's parents are ethnically Chinese, but were born and lived in Vietnam. They came to the U.S. during the Vietnam War as refugees. Duong grew up in the Little Saigon area of Orange County, Calif. He remembers paying tributes to his ancestors and eating the same traditional dishes every year, but his relationship with the holiday is complicated.

"My parents never really got me," said Duong, who is gay. "We've always had a distant relationship. The new year doesn't represent much to me," he said. "I sort of know when Chinese New Year is coming up, but I don't really celebrate it. I will call my parents and wish them a new year." He'll also get in touch with his younger brother and niece every year.

Though he doesn't celebrate, Lunar New Year for Duong is still a reset for what he's accomplished, a retrospective look at how far he has come and a celebration of the newness of life.

Maureen Pao, editor and digital producer

Pao grew up in South Carolina with her parents, who emigrated from Taiwan, and Lunar New Year for her was a "big fun holiday," akin to Christmas. Their celebrations usually included partying with the entire local Chinese association. Because there weren't many other Asians in her community, the association spanned several counties. "There was a feeling of community," she said. "Most of the stuff that I learned and practice came from that association." At home, her grandparents would send the family red envelopes, clothes and food from Taiwan.

Pao became much more immersed in the traditions after spending time in mainland China after college. "There was much more cleaning of the house and all the special foods," she said. "Many of my Chinese New Year memories center around the food."

What to Eat? A Daughter's Lunar New Year Dilemma

Her kids attend a Chinese immersion public charter school, where they get more exposure to the holiday. At home, she makes sure to decorate the house for the New Year.

Pao and her husband, who is white, were both keen on making sure their kids grew up familiar with their Chinese roots, and the Lunar New Year is a time to do just that. "It's a time to take stock of the past and to celebrate and get excited about what comes next," she said. "But to me it's especially about family and food. Even when it's just my kids and my husband and me, it still feels very special. It keeps us connected to each other and to Chinese traditions."

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

Products are independently selected by our editors. We may earn an affiliate commission from links.

What the Lunar New Year Means to Me

By Lan Samantha Chang

My preparations for each Lunar New Year begin in the bathroom. On Lunar New Year’s Eve, I turn on the hot water and let the air fill with steam. With my bare toes curled against the chilly floor, I scissor off a lock of hair, clip my nails, and discard these symbolic crumbs of bad luck into the trash. Then I get in the shower, where I suds and scour and scrub down every inch of skin.

“You have to wash off all of the bad luck from the year before.” This was my mother’s imperative, as if bad fortune could accumulate into a grungy layer over the course of the year. As if I had one chance—a crucial opening on a February night—in which it would be possible to get rid of it.

The cleanse on Lunar New Year’s Eve is one of many customs—really, superstitions—taught to me by my late mother and father. It’s part of a larger idea that everything should be immaculate, including the body and the home, which should also be tidied and, most importantly, swept out. This is done to lay a perfect groundwork for the coming year: spotless and unblemished by past trouble. A vision of an annual opportunity, of incremental growth, was a fundamental part of my parents’ Chinese lives long before the 1950s, when they put these lives behind them to face a new existence in the US.

My parents’ catalog of rituals must contain only a fraction of the traditions followed by Lunar New Year’s billion celebrants worldwide. But my mother and father were firm about what they believed. We must eat certain lucky foods: labor-intensive sweet-rice-and-red-bean cakes; steamed dumplings; a whole fish covered with ginger and scallions; and lots of fruit, including, especially, oranges and lychees. The lychees, my mother warned, should not be paired with crabmeat—a bad combination, a dangerously “cold” shock to the system, possibly fatal. And we should never make soup because “if you serve soup on New Year’s, it will rain on every special occasion for the rest of the year.” When we had a rare meal out, we went to my parents’ favorite local restaurant, Bao Ju, in Neenah, Wisconsin. It was named after the Chinese word for firecrackers, which were set off on the New Year to chase away evil spirits. The phone number of the restaurant contained several eights; eight was a lucky number, as was nine, whereas four, the unluckiest number of all, should be avoided.

My parents wished so fervently for luck in the New Year. For good health, of course, but especially for money. And so bits of cash were exchanged, to encourage an increase of fortune. We children thanked our older relatives for annual red envelopes that were sent to us by mail. On the second day of the New Year, my father or mother would usually bundle up in something red and hurtle him or herself into the glacial Wisconsin winter, walking, “in all directions,” in an attempt to encounter the Money God. Such a meeting, I was told, would result in a rich year. My questions about this ritual were met with a dead end. “What does the Money God look like?” I asked my mother. “No one knows.” “Will the Money God appear as a person? Is it an inanimate object?” “I don’t know.” “What are the other gods?” Silence.

Thus my parents shut down my questions whenever I tried to cross-examine them about these protocols. I was lectured on the value of a “rational” Western education. They insisted superstitions were for the ignorant and they would sometimes scold me for even mentioning such topics. I learned to keep my mouth shut and my ears open. My sisters and I overheard my father and mother, behind closed doors, discussing in hushed voices our strengths and weaknesses as students and daughters, referring to our birth animals from the Chinese zodiac. When one of us entered the room, they would immediately stop talking. Maybe they didn’t want us to know of their belief in the irrational; maybe they wanted to protect us from succumbing to fatalism. After I left home for college, my mother would phone me on the holiday to deliver Lunar New Year prognostications for my sisters and myself. If a bad year was coming, I should wear a red bracelet. She claimed the predictions were oddities from the Chinese newspaper. She said she didn’t believe any of it. But if I waited long enough, she would drop bits of information denoting genuine concern for me or one of my sisters—that women born in the Year of Dragon (myself) marry late, for example, and that Horse women (my oldest sister) never marry at all.

Decades later, now that both of my parents are gone, I wonder why their New Year practices were so steeped in superstition. My mother and father had US college educations and my father held a master’s degree in engineering from Columbia University. They each claimed a Western rationality. Did they actually believe that taking certain, ritual actions portended good luck? It’s now too late to ask. My mother died in 2014, and my father died in 2020, outlasting her at age 97.

Of course, my parents longed for money—they had four children and my father’s salary as a researcher didn’t cover extras. As they were unable to afford childcare, my mother stayed home with us. We never ate at McDonald’s. My sisters learned to sew their own prom dresses. When my youngest sister started school, my mother began to work, giving piano lessons in our living room. But as we grew, new financial challenges evolved: transportation, books, tuition.

To my mother, I think, the desire for money must have been a way to manage her anxiety over even larger uncertainties: What would become of her poor health, my impractical career choices, the lack of clarity in my sisters’ and my romantic lives? Maybe in the New Year, I would finally start to make some money as a writer. Maybe I would meet the perfect man: a Monkey or a Rat. Born only 40 years after the end of foot-binding, my mother had studied psychology before she married my father, raised us, and eventually made a career as a respected teacher. She had one of the most open minds I’ve known. But in addition to her belief in the value of education and environment, she held a deep need to assume some power outside of herself. She possessed a kind of fatalism that had emerged, I am guessing, during the constant wishing and hoping through her childhood in wartime China and, later, in the US as an impoverished student with no family support.

My father, a chemical engineer, had worked hard for an education in Western science. He generally scoffed at old customs, keeping his silence on this subject. And yet, he didn’t contradict anything my mother said about it. With a child’s instinct, I sensed he believed in the superstitions my mother explicitly asserted. Even then, I knew my father was more afraid of the power of bad luck than he was hopeful for good luck. He had grown up in mainland China under the Japanese occupation, and had been homeless in a war, before he turned 19. He had gone hungry. The prolonged, high-wire act of his life was arriving in this country at age 30 with nothing, raising a family on an inadequate salary, and somehow managing to put all four of his daughters through Ivy League colleges. As a parent now myself, I can see he took responsibility for our lives, and so his fear of bad fortune was embedded in some deeper, more elemental part of his nature. His fear was the bedrock of the nightmares he suffered since I can remember.

By Elise Taylor

By Emma Specter

By Lilah Ramzi

When they first came to Wisconsin—that desolate, frozen tundra—my mother and father decided to have no family holidays at all. They didn’t believe in American customs. The idea of a fat white man in a red suit sliding down the chimney was entirely bizarre to them. As for Lunar New Year, celebrated by more people than any other holiday in the world, almost no one in Appleton, Wisconsin, knew the slightest thing about it. The gathering of family, the making of sticky rice cakes, the noise and celebration of the New Year in diasporic communities all over the world meant nothing to the people around us.

But after a year, my parents realized how important it was to have something to look forward to. Our family began to celebrate not only the Lunar New Year, but Christmas and Thanksgiving as well. With the arrival of more Chinese families in our town, we gathered with them for a big meal on New Year’s Eve. My mother exchanged rumors on the coming year’s horoscopes with the other mothers, finding a lot to discuss even after my oldest sister, the Horse, was happily married.

Now, as a Chinese American living and teaching at a university in the Midwest, Lunar New Year is a cultural holiday I observe and try to share with my coworkers, friends, and family—a cause for celebration in the coldest, darkest part of winter. I accept my parents’ customs as a way of showing my love for them, my loyalty to them and their experience. Because I live in another small Midwestern city, celebrating Lunar New Year has meant learning to share my rituals with people I love to whom the traditions are not familiar. I’ve also explained these customs to my biracial daughter, who is one generation more removed from my parents and their world.

This New Year’s Eve, I don’t know if I’ll have time to clean the house. But I will set aside an hour for my bathroom ritual. I’ll schedule family haircuts, and send emails reminding non-Chinese friends to wash, clip, and snip. And even though next year will not be a Dragon year, I’ll riffle through the cabinets at work to dig up a worn stuffed dragon, the gilt rubbing off its wings, that was given to me as a New Year gift by a beloved and now deceased mentor. I’ll invite interested students to help me throw a party. We’ll decorate the place with the dragon, red signs, cartoon animals, and streamers. We’ll buy oranges and gold foil-covered chocolate coins. Then we’ll host a big, boisterous Chinese lunch. Everyone will eat, make noise, and scare away demons. They’ll take out their phones and look up their birth animals, and try to predict what will happen to them in the Year of the Rabbit. The following day, I will put on something red, so the Money God can see me, and I will go outside to walk in all directions.

Lan Samantha Chang is the author of the novel The Family Chao .

In this story: hair, Charlie Le Mindu; makeup, Fara Homidi. Produced by Hen’s Tooth Productions. Set Design: Griffin Stoddard.

- Paired Texts

- Related Media

- Teacher Guide

- Parent Guide

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your web browser.

- CommonLit is a nonprofit that has everything teachers and schools need for top-notch literacy instruction: a full-year ELA curriculum, benchmark assessments, and formative data. Browse Content Who We Are About

Your Home Teacher

Home » Essays » Chinese New Year – Few lines, Short Essay and Full Essay

Chinese New Year – Few lines, Short Essay and Full Essay

Few lines about chinese new year.

- Chinese new year is also known as Lunar new year

- It is a Chinese festival celebrating the beginning of a new year of the Chinese calendar.

- In mainland china, the day marks the onset of spring and is referred as the Spring Festival.

- In 2020, the Chinese New Year is celebrated on 25th January and it’s a public holiday.

- This Chinese year is called the Year of the Rat.

Brief essay on Chinese New Year

Chinese New Year is a well-known Chinese festival that celebrates the beginning of a new year of the Chinese calendar. It is also known as lunar New Year or the Spring Festival as it marks the onset of spring. The first day of Chinese New Year begins on the new moon day that happens between 21 January and 20 February. In 2020 the Chinese New Year is celebrated on 25th January commencing the Year of the Rat. Chinese New Year is an important holiday in China and the festival is also celebrated worldwide in regions with significant Chinese populations.

Long Essay on Chinese New Year

Chinese New Year marks the beginning of a new year in the Chinese calendar. It is also termed as “Lunar New Year”, “Chinese New Year Festival”, and “Spring Festival”. Generally, the Chinese New Year falls on different dates every year in the Gregorian calendar. It is calculated based on the first new moon day that falls between 21th of January and 20th of February.

Chinese New Year celebrations starting from the New Year eve and ends with the Lantern festival that is held on the 15th day of the year. Chinese New Year is observed as a public holiday in china and in several countries with sizable Chinese and Korean population. It is the longest holidays in china. The holidays mark the end of the winter’s coldest days and people welcome the spring, praying to Gods for the upcoming planting and harvest season.

Different regional customs and traditions accompany the festival. Eating dumplings, Yule Log cake, tang yuan or ‘soup balls’, and red envelopes with ‘lucky’ money are part of customary celebration. According to some Myth, the Chinese New Year festival celebrates the death of a monster called Nian, which was killed by a brave boy with fire crackers on the New Year’s Eve. And that’s why firecrackers is considered the crucial part of the Spring Festival as it is believed to scare off monsters and bad luck.

This year, 2020, Chinese New Year falls on 25th of January is called the year of the Rat.

2 Responses

this is helpful and great for school

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Loyola University Chicago Libraries

Luc reading/resource lists.

- LUC Libraries Reading/Resource Lists

- Hispanic/Latinx/Latine Heritage Month (Sept 15-Oct 15)

- Remembering September 11, 2001

- Constitution Day (Sept 17)

- Banned Books Week (Oct 1-7, 2023)

- Filipino American History Month (October)

- Indigenous Peoples' Day (October 9)

- Día de los Muertos (Nov 1 & 2)

- Native American Heritage Month (Nov)

- Our Lady of Guadalupe Feast Day (Dec 12)

- Hanukkah/Chanukah

- Diwali 2023: Nov 12

- Martin Luther King Jr. Day

- Black History Month (Feb)

- Lunar New Year

- Women's History Month (March)

- Persian Heritage Month (March)

- Ramadan (March 11-April 9) & Eid al-Fitr (April 9-10), 2024

- Easter (March 31), 2024

- Passover (Apr 22-23), 2024

- Mental Health Awareness Month (May)

- Transgender Day of Visibility (March 31st)

- Arab American Heritage Month (April)

- Poetry Month Celebration (April)

- Earth Day (April 22)

- Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Heritage Month (May)

- Jewish American Heritage Month (May)

- Star Wars Day (May 4)

- International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia (May 17)

- Pride Month (June)

- Immigrant Heritage Month (June)

- World War II: D-Day, 80th Anniversary (June 6, 2024)

- Juneteenth (June 19th)

- Independence Day (July 4th)

- Disability Pride Month (July)

Lunar New Year - Year of the Dragon

The Gregorian calendar is followed and the solar new year is an official holiday in Asian countries. But the lunar new year is still the most important festival in several Southeast and Northeast Asian countries, especially among those of Chinese descent. The lunar new year marks the ending of the old and the beginning of the new year. It is on the first day of the first lunar month. In the Gregorian calendar, the festival falls somewhere between January 21 and February 19. Let's take a look at how this most important holiday is observed in different countries, and check out the list of books!

- While many ring in the Year of the Rabbit, Vietnam celebrates the cat (NPR)

- Happy Year of the Rabbit! Or is it the Year of the Cat? Well, it depends ... (SALON)

- Year of the Rabbit or Year of the Cat? Depends on where you live (PBS)

- Lunar New Year Worldwide Celebrations

- Local Cultural Centers

- Virtual Celebrations

Check out these local organizations and cultural institutions!

- China Institute Chinese New Year Online Family Festival

- Japan America Society of Chicago New Year Origami Workshop

Celebrate the Lunar New Year!

Philippines

The Chinese tradition of representing the years with animals dates back to the Han dynasty (approx. 220 BCE). The 12-year cycle of the animals in the Chinese Zodiac is similar to astrological signs. Each year is represented by an both animal and an element. People who are born in that year are said to have the particular characteristics or mannerisms of the animal, both positive and negative, that are also affected by the element. The 12 animals include rat/mouse, ox/buffalo, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep/goat/ram, monkey, chicken/cock/rooster, dog, and pig. The 5 elements include metal, water, wood, fire, and earth. February 10, 2024, is the beginning of the year of the wood dragon.

The Lunar New Year is an important traditional holiday to China and other Asian countries such as Vietnam, Korea, Singapore, etc. It is also called Chinese New Year, Spring Festival, Asian New Year, Tsagaan Sar, Seollal, or Tết. It occurs on the first day of the first month of the lunar calendar. The exact date of the Lunar New Year can vary from year to year on the Gregorian (U.S.) calendar, which is based on the cycles of the sun since the lunar calendar is based on the phases of the moon.

The Lunar New Year is celebrated over a number of days and is a time for merriment and remembrance with families and friends. Traditional customs include gifts of red envelopes and oranges; special foods such as dumplings and long noodles; and celebrations with fireworks and lion dancers.

China (Spring Festival, Xin Nian)

The celebration starts from the beginning of the twelfth lunar month through the 15th day of the first lunar month, the Lantern Festival. Legend tells that in ancient times, a horrible monster called "nian" (same word for "year") appeared at the end of the year, attacked people and livestock, but the villagers could not defeat it. Finally, the villagers found out the monster would be terrified by the color red and noise. People set off firecrackers, wore red clothes, hang red lanterns, and painted their homes red at the end of the year. The beast panicked and ran away. The cheerful bright red color is the most popular color for the Spring Festival.

Traditional Spring Festival events include:

Twelfth lunar month:

Day 8: Offering of Soup of the Eighth Day (Laba Gruel). Laba gruel is a thick porridge consisting of "various whole grains and/or rice with dried fruits and nuts such as dates, chestnuts, pine seeds, and raisins."

Day 23: Sending off the Kitchen God. The Kitchen God is the agent of the heavenly authority and spends the whole year with the family. On the 23rd of the last month of the lunar year, he ascends to heaven and makes a report of the family. Family present offerings, hoping the deity will speak of good things. A paper horse is set on fire as the god's steed to ascend to heaven.

Day 30: New Year's Eve (Chu xi). Fierce door Gods (Men shen) are pasted on the center panels of doors, auspicious spring scrolls/couplets (Chun lian) on each side of the front door. People sweep the house to send off misfortune. Offerings to gods and ancestors are made. Family reunion meals take place. People stay awake to safeguard the year.

First Lunar Month:

Day 1: New Year's Day. Set off firecrackers. People change into new clothes and visit elders. Elders pass out red envelopes (Hong bao) containing "lucky money" (Ya sui qian). Burn incense and worship deities in temples.

Days 1-5: Relatives/friends visits. Traditional new year food includes meat dumplings (Jiao zi), fish, and sweet steamed glutinous rice pudding (Nian gao). Fruits, nuts, and seeds are popular snacks, conveying "wishes for fertility and long life." Especially in the south part of China, flowers such as lotus, camellia, hand citron, and narcissus are used to decorate home.

Day 15: the Lantern Festival Day (Deng jie) or the Feast of the First Full Moon (Yuanxiao jie). A wild variety of lanterns are displayed. People go to the streets and view processions of stilt walkers, lions dances, dragon parade,s and opera performances. Sweet-tasting glutinous rice flour balls called Yuan xiao, is consumed in every household.

Chang, Mei-Yen. "Lunar New Year In Taiwan." International Journal Of Education Through Art 6.1 (2010): 41-57.

Stepanchuk, Carol and Wong, Charles. Mooncakes and Hungry Ghosts: Festivals of China. San Francisco: China Books & Periodicals, 1991.

Vietnam (Tet Nguyen Dan or Tet)

Tet is the most important annual festival in Vietnam, both culturally and spiritually. It is marked by a four-day public holiday. But the preparation for Tet starts a full month ahead and continues until the seventh day of the new year. About ten to fifteen days before Tet, people begin shopping for the holiday. Square or hexagonal cardboard candy box bearing "Happy New Year" is a must-have for every household on its ancestral altar. A great variety of calendars are available in the market and hung in every house as an ornament. Calendars have almost replaced the old custom of hanging couplets in Chinese calligraphy. Flowering branches and small trees are brought into homes during the holidays. The favorites are peach branches and small potted mandarin trees. The apricot blossom or mai flower is very popular in the South.

In tradition, Tet commences on the twenty-third day of the twelfth month when the Kitchen Gods, the three Ong Tao, are worshiped and travel to heaven to give an annual report of the family they inhabit. A bowl of three small carps is offered to be ridden by the gods for their journey to see the Heavenly King. Rice cake is an essential food to Tet for offering on ancestral altars and giving as gift exchanges between kins and friends. Cylindrical rice cakes (Banh tet) are popular in the South, while square rice cakes (Banh chung) are popular in the North. In the past, it was a tedious task to make rice cakes as people boiled the cakes ten to twelve hours over fires in a large open space. Today rice cakes can be bought in shops or ordered in advance. "Five-fruit tray" (Mam ngu qua) is another common offering on the ancestral altar, which symbolizes the "good fortune and prosperity hoped for" in the new year.

On the twenty-fifth or twenty-sixth day of the last lunar month, ancestral graves are visited and tidied. In the late afternoon of the last day of the old year or the first day of the new year, families hold a ceremony to "honor the ancestors and invite them to enjoy Tet with the living family." The ancestors will protect the family throughout the new year. The family will visit the father's or mother's lineages on the first and second days, and visit teachers or former teachers on the third day of Tet. On the first day of the new year, temples and shrines are full of people. Religious activities also take place at certain sites dedicated to former national or regional heroes.

In rural areas, a new tree, "a long bamboo pole with a pineapple at the top, decorated with a bell, lantern, and flags," would be raised outside the house once the Kitchen God has been sent off. Taking down the neu tree marks the ending of the celebration on the seventh day of the first lunar month.

McAllister, Patrick. "Religion, The State, And The Vietnamese Lunar New Year." Anthropology Today 29.2 (2013): 18-22.

McAllister, Patrick. "Connecting Places, Constructing Tết: Home, City And The Making Of The Lunar New Year In Urban Vietnam." Journal Of Southeast Asian Studies 43.1 (2012): 111-132.

The lunar new year celebration starts on the first and ends on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month. The home is cleaned and tidied for the new year. On new year's eve, families enjoy a festive meal together. On New Year's Day, the younger generation will visit elders and elders will distribute cash in red envelopes. Visitors will bring two mandarin oranges as new year's gifts since the name of orange sounds like "good fortune" and "gold (financial wellbeing)." In return, guests will get back two oranges when they leave, conveying blessings for the new year. Streets in Chinatown are beautifully and lavishly lit, and lanterns are hung up. Dragon dance, lion dance, fireworks, and fire-eating performances are popular activities.

The official site of Singapore Tourism Board: Chinese New year. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

singaporeinfopedia: Chinese New Year customs in Singapore. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

Korea (Seollal)

Seollal (Korean New Year) is a three-day national holiday and focuses on family. People spend a lot of time shopping for ancestral rites and gifts. Thousands of travelers are heading for their hometowns and transportation can be time-consuming.

The day before Seollal, family members gather together to prepare the holiday food. Tteokguk (rice cake soup) is the most important food for both ancestral rites and the New Year meal (Sechan). Rice cake (Tteok) used for tteokguk is prepared by "steaming non-glutinous rice flour, pounding the dough with a mallet until it is firm and sticks, and then shaping it into the form of a rope." The shape of a long rope signifies an expansion of good fortune in the new year. Seollal food preparation requires long hours of work. Nowadays, ready-made food can be purchased or delivered to home.

On the morning of Seollal, people dress in new clothing, especially Korea's traditional costume (Hanbok). Then the families gather to perform ancestral rites to pay respect to ancestors and pray for good fortune in the new year (Charye ritual). It is believed that ancestors will return to enjoy the holiday food. After the ancestral rites, the family shares the holiday food together. According to Korean tradition, eating tteokguk on Seollal adds one year to your age. After the meal, the younger generations will bow deeply to the elders to show respect. In return, the elders will offer good wishes along with gifts of money (Sebaetdon). Family members play traditional folk games and share stories. The most common activity is Yutnori, a board game that involves throwing four wooden sticks.

Paik, Jae-eun. "Tteokguk, Rice Cake Soup." Koreana 21.4 (2007): 76-79.

The Official Site of Korean Tourism Organization: Learn Traditional Culture to Celebrate Seollal! Retrieved February 5, 2021.

The Official Site of Korean Tourism Organization: Celebrating Seollal in Korea: A Glimpse of Local Customs. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

The lunar new year is the most important holiday for Chinese Malaysians. The celebration starts from Winter Solstice and lasts until the fifteenth of the first lunar month. Chinatown in Kuala Lumpur is decorated with red color lanterns and crowded with shoppers. On New Year's Eve, a family reunion dinner will be held. People will stay awake to safeguard the year and light fireworks. On New Year's Day, Chinese Malaysians open their homes for visits from friends of other religions and races. Sweeping the floor on New Year's Day is forbidden as good fortune will be swept away. Bad language and unpleasant topics are strictly discouraged. Relatives and friends will visit each other from the second day of the new year. Yee Sang is a special dish that is only served during Chinese New Year, conveying wishes for prosperity, health, and good luck in the new year. Dragon and lion dances are held in Chinatown and there are many prayers in temples. On the fifteenth day of the first lunar month (Chap Goh Mei, known as Chinese Valentine's Day), young unmarried women will throw tangerines into the sea, wishing to find a good husband.

Wonderful Malaysia, "Chinese New Year in Malaysia." Retrieved February 6, 2021.

Lim, Audrey. "Chap Goh Mei." Retrieved February 6, 2021.

NPR WBZ Chicago, "Yusheng: A Dish To Toss In The air To Celebrate The Chinese New Year." Retrieved February 6, 2021.

On New Year's eve, Thai Chinese will hold ancestral rites, offer fruits, taro, sweets, and other dishes on the altar, and burn incense. After ancestral worship, families will enjoy a reunion meal together. On New Year's Day, Thai Chinese will pay pilgrimage to temples and pray for favorable climatic weather and good wellbeing in the new year. Chinatown in Bangkok is decorated with lanterns, and dragon parades and lion dances are held.

"How Thai Chinese Celebrate the Spring Festival." Retrieved January 24, 2019 (Translated by the author).

Lunar New Year was announced as a public holiday in 2012 in the Philippines. The lunar new year is the most prominent celebration for Chinese Filipinos. People participate in dragon and lion dances in Chinatown and enjoy a Chinese opera performance. Tikoy (sticky rice cake) giving is a tradition and is only available for purchase in stores around Lunar New Year time. Red envelopes containing luck money (Ang pao) are distributed to children.

"Chinese New Year Celebrated in the Philippines." Asia Society. Retrieved February 6, 2021 .

Japan (Shogatsu, 正月)

Since 1873, the official and cultural Japanese New Year has been celebrated on January first based on the Gregorian calendar. Kadomatsu, the bouquet of pine and bamboo which stands for longevity and righteousness, stand before entrance as a new year's decoration. Twisted straw rope (Shimenawa) is put over doors of the house to "bring good luck and keep evil out." New crops and mochi (rice cakes) are offered to gods in thanks and people pray for good harvests in the new year. Osechi is a special cooking for the new year prepared in a four-tiered lacquered box. From new years' eve to the seventh day of January, Japanese people pay their first pilgrimage of the year to shrines or temples and pray for good fortune in the new year (Hatsumode). Children receive pocket money (Otoshidama) from parents and kins. Kite-flying is a popular play for boys and battledore and shuttlecock for girls.

"A guide to New Year traditions in Japan." Japan Today. Retrieved February, 6 2021.

- Curriculum Books (Children's/YA)

- Celebrations

Streaming Films

The way home : a motorcycle journey

Chinese New Year. Episode 1, Migration

Chinese New Year. Episode 2, Reunion

Chinese New Year. Episode 3, Celebration

Coming home for Chinese New Year. Homecoming express

- << Previous: Black History Month (Feb)

- Next: Women's History Month (March) >>

- Last Updated: Jun 10, 2024 2:44 PM

- URL: https://libguides.luc.edu/Lists

Loyola University Chicago Libraries Cudahy Library · 1032 W. Sheridan Rd., Chicago, IL 60660 · 773.508.2632 Lewis Library · 25 E. Pearson St., Chicago, IL 60611 · 312.915.6622 Comments & Suggestions Notice of Non-discriminatory Policy

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

The Significance of Lunar New Year Celebrations

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Lunar New Year Tradition

Cultural Significance

Impact on identity and values, passing on the tradition.

The Significance of Lunar New Year Celebrations. (2024, Jan 26). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/the-significance-of-lunar-new-year-celebrations-essay

"The Significance of Lunar New Year Celebrations." StudyMoose , 26 Jan 2024, https://studymoose.com/the-significance-of-lunar-new-year-celebrations-essay

StudyMoose. (2024). The Significance of Lunar New Year Celebrations . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/the-significance-of-lunar-new-year-celebrations-essay [Accessed: 25 Jun. 2024]

"The Significance of Lunar New Year Celebrations." StudyMoose, Jan 26, 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. https://studymoose.com/the-significance-of-lunar-new-year-celebrations-essay

"The Significance of Lunar New Year Celebrations," StudyMoose , 26-Jan-2024. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/the-significance-of-lunar-new-year-celebrations-essay. [Accessed: 25-Jun-2024]

StudyMoose. (2024). The Significance of Lunar New Year Celebrations . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/the-significance-of-lunar-new-year-celebrations-essay [Accessed: 25-Jun-2024]

- Chinese New Year Celebrations: Embracing Tradition and Unity Pages: 3 (826 words)

- Heian Celebrations: Timeless Joys of New Year's Festivities Pages: 3 (742 words)

- Lantern Festival and Chinese New Year Celebrations Pages: 2 (319 words)

- The Different Customs of New Year Celebrations Around the World Pages: 2 (492 words)

- Unveiling Patriots' Day: Origins, Significance, and Celebrations Pages: 3 (840 words)

- Pakistan Independence Day: Celebrations & Significance Pages: 2 (431 words)

- Decoding Mina Loy's "Lunar Baedeker" Pages: 7 (2017 words)

- Chinese New Year: Favorite Holiday Of The Year Pages: 3 (845 words)

- Public Holidays And Celebrations Pages: 7 (1871 words)

- Brothers Living Away from Home Miss Eid Celebrations Pages: 2 (410 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

What is Lunar New Year and how is it celebrated?

FILE - A woman takes a picture of red lanterns and decorations on display along the trees ahead of the Chinese Lunar New Year at Ditan Park in Beijing, Feb. 4, 2024. In many Asian cultures, the Lunar New Year is a celebration marking the arrival of spring and the start of a new year on the lunisolar calendar. It’s the most important holiday in China where it’s observed as the Spring Festival. (AP Photo/Andy Wong, file)

FILE - Members of Los Angeles Lung Kong Lion Dance Club perform at the L.A. Chinatown Firecracker 45th annual event in Los Angeles, Feb. 18, 2023. On Feb. 10, Asian American communities around the U.S. will ring in the Year of the Dragon with community carnivals, family gatherings, parades, traditional food, fireworks and other festivities. In many Asian countries, it is a festival that is celebrated for several days. In diaspora communities, particularly in cultural enclaves, Lunar New Year is visibly and joyfully celebrated. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, file)

FILE - This Feb. 6, 2013 file photo shows a woman walking out a shop selling seasonal items ahead of Chinese New Year in Chinatown in Bangkok, Thailand. In many Asian cultures, the Lunar New Year is a celebration marking the arrival of spring and the start of a new year on the lunisolar calendar. It’s the most important holiday in China where it’s observed as the Spring Festival. It’s also celebrated in South Korea, Vietnam and diaspora communities around the world. (AP Photo/Sakchai Lalit, File)

FILE - Divers perform an underwater lion dance at the KLCC Aquaria ahead of Chinese Lunar New Year celebrations in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Feb. 4, 2024. In many Asian cultures, the Lunar New Year is a celebration marking the arrival of spring and the start of a new year on the lunisolar calendar. It’s the most important holiday in China where it’s observed as the Spring Festival. It’s also celebrated in South Korea, Vietnam and diaspora communities around the world. (AP Photo/Vincent Thian, file)

FILE - Revelers celebrate Lunar New Year in Manhattan’s Chinatown, Feb. 12, 2023, in New York. On Feb. 10, 2024 Asian American communities around the U.S. will ring in the Year of the Dragon with community carnivals, family gatherings, parades, traditional food, fireworks and other festivities. In many Asian countries, it is a festival that is celebrated for several days. In diaspora communities, particularly in cultural enclaves, Lunar New Year is visibly and joyfully celebrated. (AP Photo/John Minchillo, file)

FILE - A woman offers prayer at the Wong Tai Sin Temple, Jan. 21, 2023, in Hong Kong, to celebrate the Lunar New Year. In many Asian cultures, the Lunar New Year is a celebration marking the arrival of spring and the start of a new year on the lunisolar calendar. It’s the most important holiday in China where it’s observed as the Spring Festival. It’s also celebrated in South Korea, Vietnam and diaspora communities around the world. (AP Photo/Bertha Wang, file)

- Copy Link copied

On Feb. 10, Asian American communities around the U.S. will ring in the Year of the Dragon with community carnivals, family gatherings, parades, traditional food, fireworks and other festivities. In many Asian countries, it is a festival that is celebrated for several days. In diaspora communities, particularly in cultural enclaves, Lunar New Year is visibly and joyfully celebrated.

In the Chinese zodiac , 2024 is the Year of the Dragon. Different countries across Asia celebrate the new year in many ways and may follow a different zodiac.

What is the Lunar New Year?

The Lunar New Year — known as the Spring Festival in China , Tet in Vietnam and Seollal in Korea — is a major festival celebrated in several Asian countries. It is also widely celebrated by diaspora communities around the world.

It begins with the first new moon of the lunar calendar and ends 15 days later on the first full moon. Because the lunar calendar is based on the cycles of the moon, the dates of the holiday vary slightly each year, falling between late January and mid-February.

What are the animals of the zodiac?

Each year honors an animal based on the Chinese zodiac. The circle of 12 animals — the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog and pig — measure the cycles of time. Legend has it that a god beckoned all animals to bid him farewell before his departure from earth and only 12 of them showed up. The Vietnamese zodiac is slightly different, honoring the cat instead of the rabbit and the buffalo instead of the ox.

What are some beliefs and traditions around the Lunar New Year?

One well-known ancient legend speaks of Nian, a hideous monster that feasted on human flesh on New Year’s Day. Because the beast feared the color red, loud noises and fire, people put up red paper dragons on their doors, burned red lanterns all night and set off firecrackers to frighten and chase away the monster.

To this day, the Lunar New Year celebration is centered around removing bad luck and welcoming all that is good and prosperous. Red is considered an auspicious color to ring in the new year. In many Asian cultures, the color symbolizes good fortune and joy. People dress up in red attire, decorate their homes with red paper lanterns and use red envelopes to give loved ones and friends money for the new year, symbolizing good wishes for the year ahead. Gambling and playing traditional games is common during this time across cultures.

Ancestor worship is also common during this time. Many Korean families participate in a ritual called “charye,” where female family members prepare food and male members serve it to ancestors. The final step of the ceremony, called “eumbok,” involves the entire family partaking the food and seeking blessings from their ancestors for the coming year. Vietnamese people cook traditional dishes and place them on a home altar as a mark of respect to their ancestors.

Some Indigenous people also celebrate Lunar New Year this time of year, including members of Mexico’s Purepecha Indigenous group .

How do diaspora communities celebrate?

Members of Asian American communities around the U.S. also organize parades, carnivals and festivities around the Lunar New Year featuring lion and dragon dances, fireworks, traditional food and cultural performances. In addition to cleaning their homes, many buy new things for their home such as furniture and decorate using orchids and other brightly colored flowers.

Lunar New Year is also celebrated as a cultural event by some Asian American Christians and is observed by several Catholic dioceses across the U.S. as well as other churches.

What are some special foods for the new year?

Each culture has its own list of special foods during the new year, including dumplings, rice cakes, spring rolls, tangerines, fish and meats. In the Chinese culture, for example, “changshou mian” or “long-life noodles” are consumed with a wish for a long, healthy and happy life. In Vietnamese culture, banh chung and banh tet — traditional dishes made from glutinous rice — are a must for the celebrations. To make a banh tet, banana leaves are lined with rice, soft mung beans and pork belly and rolled into a tight log, which is then wrapped in the leaves and tied up with strings. Koreans celebrate with tteokguk, a brothy soup that contains thinly sliced rice cakes.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

- Tet An Introduction To Vietnamese...

Tết: An Introduction To Vietnamese New Year

Tết is by far the biggest celebration in Vietnam. Every year, millions of people fly, drive and float their way back to their hometowns to spend quality time with their friends and families. The meals are big, the songs are loud, and everyone’s in a good mood. Vietnamese people wait all year for this, but what is Tết?

Pronounced: Tut (Though Tet is fine.)

The Tết holiday coincides with the Chinese Lunar New Year, which falls sometime around the end of January, or the beginning of February. Generally speaking, Tết is a time to dish out the spoils from a prosperous year — to bring good fortune through generosity. In the months leading up to the holiday, people work long hours to pay for lavish gifts and celebrations. But it’s time spent with family and friends that makes Tết so special.

The first day of Tết is meant to be for immediate family. Parents and grandparents hand out lucky money to their children and grandchildren — usually cash gifts in red envelopes, which is the color of luck. For kids, this means it’s time to load up on new toys and snacks. After the immediate family, it’s time to celebrate with friends and neighbors.

Wealthier families spring for dance ceremonies, often featuring lion dancers (Múa Lân). People believe that the noise from drums and firecrackers keeps evil spirits away. Mood is an important way to receive blessings, so the songs are loud and festive with many hearty toasts of “Một, hai, ba, dzô!” (one, two, cheers, cheers!)

The first visitor of the year is an important consideration in households, because their guest’s status and moral character are decisive harbingers for the upcoming year’s fortunes. Well-respected guests bring good luck. After the first guest, many people are invited to come celebrate together. If you’re a foreigner , expect to be dragged into numerous circles of drunk friends. This is a time to party, after all.

Decorations

Flowers are intricately linked to Tết, and different flowers represent different messages in the home. In the south, you’ll mostly see yellow apricot flowers — a symbol of wealth. In the north, you’ll see pink peach flowers — the color of seduction . To go along with the flowers, people hang envelopes with lucky money around their homes. For public areas, the money in the envelopes is usually fake.

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to $1,665 on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

The most famous snack associated with Tết is Bánh tét — or Tết cake — which is sticky rice, mung bean and pork, boiled inside a leaf. Roadside carts selling these cylindrical green bundles pop up everywhere as the holiday approaches. Just the sight of a bicycle loaded with Tết cakes gets people excited, because it means their favorite holiday is almost here.

Families also have large fruit trays in their homes, featuring plums, bananas, pomelos and tangerines. The more fruit, the better. They’re symbolic of fertility in the upcoming year. No fruit means no babies. Dried fruit is also a popular snack to give to children during the holiday, along with peanut brittle and coconut candies.

The most joyous part of Tết, though, is the meals. They are huge, delicious, and the room is typically full of laughter. People who haven’t seen each other in months catch up and share stories, drinking a lot of beer and liquor in the process. Don’t be surprised if you hear families still going strong in the very early hours of the morning.

The only words you need to know

Learn these words , because you’ll be hearing and saying them a lot should you find yourself in Vietnam during Tết.

Chúc Mừng Năm Mới! (Happy New Year!)

Pronounced: Chook Mung Nam Moi!

Culture Trips launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes places and communities so special.

Our immersive trips , led by Local Insiders, are once-in-a-lifetime experiences and an invitation to travel the world with like-minded explorers. Our Travel Experts are on hand to help you make perfect memories. All our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

All our travel guides are curated by the Culture Trip team working in tandem with local experts. From unique experiences to essential tips on how to make the most of your future travels, we’ve got you covered.

See & Do

Where to find the most spectacular rice fields in vietnam.

Guides & Tips