- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Case Method Teaching and Learning

What is the case method? How can the case method be used to engage learners? What are some strategies for getting started? This guide helps instructors answer these questions by providing an overview of the case method while highlighting learner-centered and digitally-enhanced approaches to teaching with the case method. The guide also offers tips to instructors as they get started with the case method and additional references and resources.

On this page:

What is case method teaching.

- Case Method at Columbia

Why use the Case Method?

Case method teaching approaches, how do i get started.

- Additional Resources

The CTL is here to help!

For support with implementing a case method approach in your course, email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2019). Case Method Teaching and Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved from [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/case-method/

Case method 1 teaching is an active form of instruction that focuses on a case and involves students learning by doing 2 3 . Cases are real or invented stories 4 that include “an educational message” or recount events, problems, dilemmas, theoretical or conceptual issue that requires analysis and/or decision-making.

Case-based teaching simulates real world situations and asks students to actively grapple with complex problems 5 6 This method of instruction is used across disciplines to promote learning, and is common in law, business, medicine, among other fields. See Table 1 below for a few types of cases and the learning they promote.

Table 1: Types of cases and the learning they promote.

| Type of Case | Description | Promoted Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Directed case | Presents a scenario that is followed by discussion using a set of “directed” / close-ended questions that can be answered from course material. | Understanding of fundamental concepts, principles, and facts |

| Dilemma or decision case | Presents an individual, institution, or community faced with a problem that must be solved. Students may be presented with actual historical outcomes after they work through the case. | Problem solving and decision-making skills |

| Interrupted case | Presents a problem for students to solve in a progressive disclosure format. Students are given the case in parts that they work on and make decisions about before moving on to the next part. | Problem solving skills |

| Analysis or issue case | Focuses on answering questions and analyzing the situation presented. This can include “retrospective” cases that tell a story and its outcomes and have students analyze what happened and why alternative solutions were not taken. | Analysis skills |

For a more complete list, see Case Types & Teaching Methods: A Classification Scheme from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

Back to Top

Case Method Teaching and Learning at Columbia

The case method is actively used in classrooms across Columbia, at the Morningside campus in the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), the School of Business, Arts and Sciences, among others, and at Columbia University Irving Medical campus.

Faculty Spotlight:

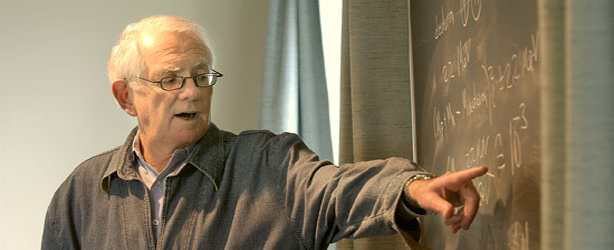

Professor Mary Ann Price on Using Case Study Method to Place Pre-Med Students in Real-Life Scenarios

Read more

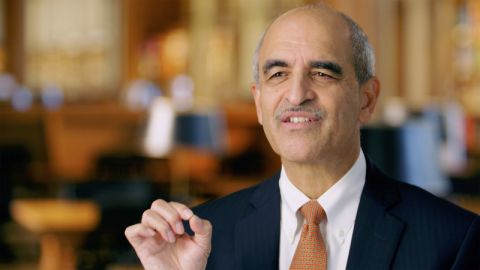

Professor De Pinho on Using the Case Method in the Mailman Core

Case method teaching has been found to improve student learning, to increase students’ perception of learning gains, and to meet learning objectives 8 9 . Faculty have noted the instructional benefits of cases including greater student engagement in their learning 10 , deeper student understanding of concepts, stronger critical thinking skills, and an ability to make connections across content areas and view an issue from multiple perspectives 11 .

Through case-based learning, students are the ones asking questions about the case, doing the problem-solving, interacting with and learning from their peers, “unpacking” the case, analyzing the case, and summarizing the case. They learn how to work with limited information and ambiguity, think in professional or disciplinary ways, and ask themselves “what would I do if I were in this specific situation?”

The case method bridges theory to practice, and promotes the development of skills including: communication, active listening, critical thinking, decision-making, and metacognitive skills 12 , as students apply course content knowledge, reflect on what they know and their approach to analyzing, and make sense of a case.

Though the case method has historical roots as an instructor-centered approach that uses the Socratic dialogue and cold-calling, it is possible to take a more learner-centered approach in which students take on roles and tasks traditionally left to the instructor.

Cases are often used as “vehicles for classroom discussion” 13 . Students should be encouraged to take ownership of their learning from a case. Discussion-based approaches engage students in thinking and communicating about a case. Instructors can set up a case activity in which students are the ones doing the work of “asking questions, summarizing content, generating hypotheses, proposing theories, or offering critical analyses” 14 .

The role of the instructor is to share a case or ask students to share or create a case to use in class, set expectations, provide instructions, and assign students roles in the discussion. Student roles in a case discussion can include:

- discussion “starters” get the conversation started with a question or posing the questions that their peers came up with;

- facilitators listen actively, validate the contributions of peers, ask follow-up questions, draw connections, refocus the conversation as needed;

- recorders take-notes of the main points of the discussion, record on the board, upload to CourseWorks, or type and project on the screen; and

- discussion “wrappers” lead a summary of the main points of the discussion.

Prior to the case discussion, instructors can model case analysis and the types of questions students should ask, co-create discussion guidelines with students, and ask for students to submit discussion questions. During the discussion, the instructor can keep time, intervene as necessary (however the students should be doing the talking), and pause the discussion for a debrief and to ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the case activity.

Note: case discussions can be enhanced using technology. Live discussions can occur via video-conferencing (e.g., using Zoom ) or asynchronous discussions can occur using the Discussions tool in CourseWorks (Canvas) .

Table 2 includes a few interactive case method approaches. Regardless of the approach selected, it is important to create a learning environment in which students feel comfortable participating in a case activity and learning from one another. See below for tips on supporting student in how to learn from a case in the “getting started” section and how to create a supportive learning environment in the Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia .

Table 2. Strategies for Engaging Students in Case-Based Learning

| Strategy | Role of the Instructor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debate or Trial | Develop critical thinking skills and encourage students to challenge their existing assumptions. | Structure (with guidelines) and facilitate a debate between two diametrically opposed views. Keep time and ask students to reflect on their experience. | Prepare to argue either side. Work in teams to develop and present arguments, and debrief the debate. | Work in teams and prepare an argument for conflicting sides of an issue. |

| Role play or Public Hearing | Understand diverse points of view, promote creative thinking, and develop empathy. | Structure the role-play and facilitate the debrief. At the close of the activity, ask students to reflect on what they learned. | Play a role found in a case, understand the points of view of stakeholders involved. | Describe the points of view of every stakeholder involved. |

| Jigsaw | Promote peer-to-peer learning, and get students to own their learning. | Form student groups, assign each group a piece of the case to study. Form new groups with an “expert” for each previous group. Facilitate a debrief. | Be responsible for learning and then teaching case material to peers. Develop expertise for part of the problem. | Facilitate case method materials for their peers. |

| “Clicker case” / (ARS) | Gauge your students’ learning; get all students to respond to questions, and launch or enhance a case discussion. | Instructor presents a case in stages, punctuated with questions in Poll Everywhere that students respond to using a mobile device. | Respond to questions using a mobile device. Reflect on why they responded the way they did and discuss with peers seated next to them. | Articulate their understanding of a case components. |

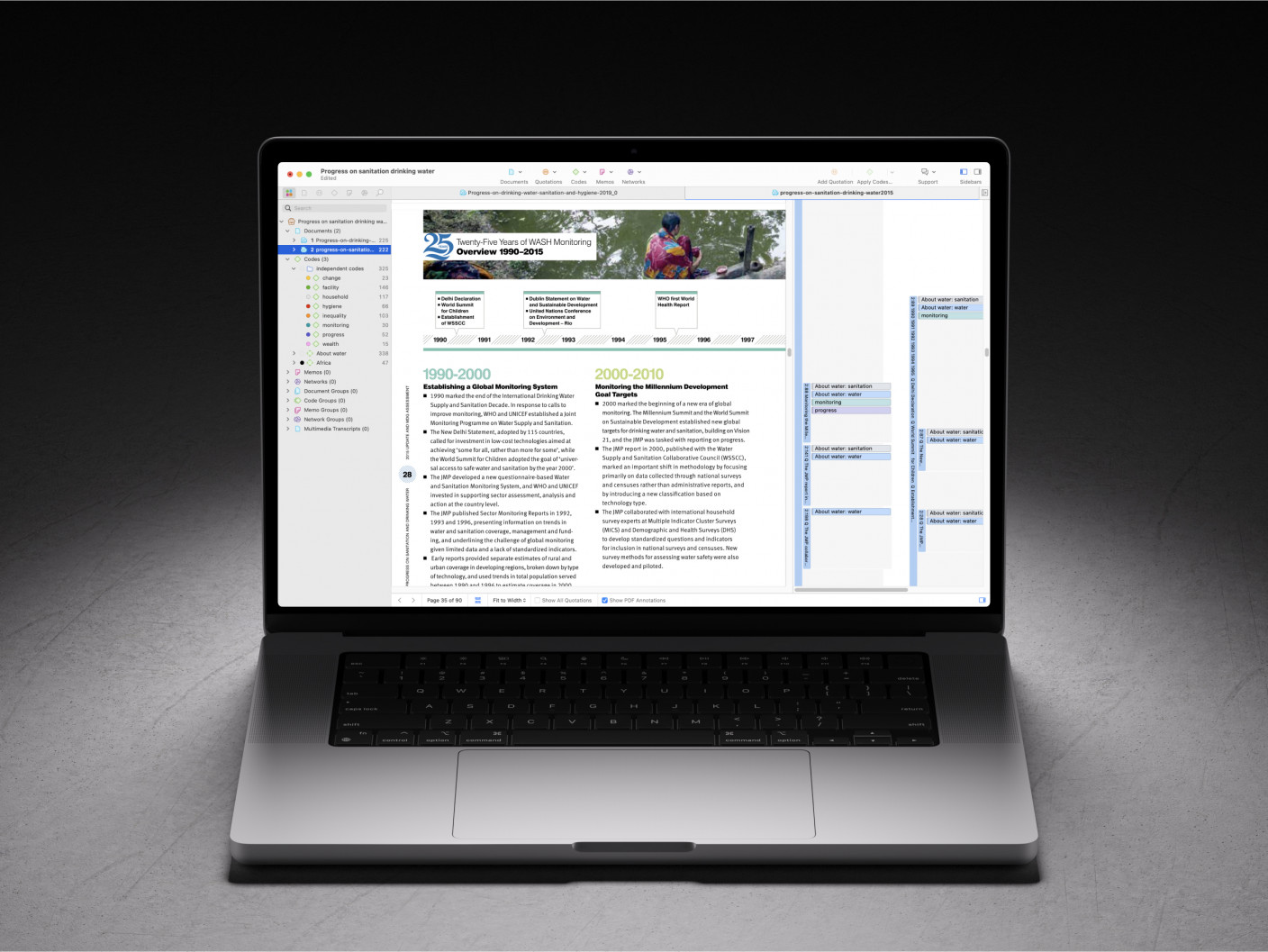

Approaches to case teaching should be informed by course learning objectives, and can be adapted for small, large, hybrid, and online classes. Instructional technology can be used in various ways to deliver, facilitate, and assess the case method. For instance, an online module can be created in CourseWorks (Canvas) to structure the delivery of the case, allow students to work at their own pace, engage all learners, even those reluctant to speak up in class, and assess understanding of a case and student learning. Modules can include text, embedded media (e.g., using Panopto or Mediathread ) curated by the instructor, online discussion, and assessments. Students can be asked to read a case and/or watch a short video, respond to quiz questions and receive immediate feedback, post questions to a discussion, and share resources.

For more information about options for incorporating educational technology to your course, please contact your Learning Designer .

To ensure that students are learning from the case approach, ask them to pause and reflect on what and how they learned from the case. Time to reflect builds your students’ metacognition, and when these reflections are collected they provides you with insights about the effectiveness of your approach in promoting student learning.

Well designed case-based learning experiences: 1) motivate student involvement, 2) have students doing the work, 3) help students develop knowledge and skills, and 4) have students learning from each other.

Designing a case-based learning experience should center around the learning objectives for a course. The following points focus on intentional design.

Identify learning objectives, determine scope, and anticipate challenges.

- Why use the case method in your course? How will it promote student learning differently than other approaches?

- What are the learning objectives that need to be met by the case method? What knowledge should students apply and skills should they practice?

- What is the scope of the case? (a brief activity in a single class session to a semester-long case-based course; if new to case method, start small with a single case).

- What challenges do you anticipate (e.g., student preparation and prior experiences with case learning, discomfort with discussion, peer-to-peer learning, managing discussion) and how will you plan for these in your design?

- If you are asking students to use transferable skills for the case method (e.g., teamwork, digital literacy) make them explicit.

Determine how you will know if the learning objectives were met and develop a plan for evaluating the effectiveness of the case method to inform future case teaching.

- What assessments and criteria will you use to evaluate student work or participation in case discussion?

- How will you evaluate the effectiveness of the case method? What feedback will you collect from students?

- How might you leverage technology for assessment purposes? For example, could you quiz students about the case online before class, accept assignment submissions online, use audience response systems (e.g., PollEverywhere) for formative assessment during class?

Select an existing case, create your own, or encourage students to bring course-relevant cases, and prepare for its delivery

- Where will the case method fit into the course learning sequence?

- Is the case at the appropriate level of complexity? Is it inclusive, culturally relevant, and relatable to students?

- What materials and preparation will be needed to present the case to students? (e.g., readings, audiovisual materials, set up a module in CourseWorks).

Plan for the case discussion and an active role for students

- What will your role be in facilitating case-based learning? How will you model case analysis for your students? (e.g., present a short case and demo your approach and the process of case learning) (Davis, 2009).

- What discussion guidelines will you use that include your students’ input?

- How will you encourage students to ask and answer questions, summarize their work, take notes, and debrief the case?

- If students will be working in groups, how will groups form? What size will the groups be? What instructions will they be given? How will you ensure that everyone participates? What will they need to submit? Can technology be leveraged for any of these areas?

- Have you considered students of varied cognitive and physical abilities and how they might participate in the activities/discussions, including those that involve technology?

Student preparation and expectations

- How will you communicate about the case method approach to your students? When will you articulate the purpose of case-based learning and expectations of student engagement? What information about case-based learning and expectations will be included in the syllabus?

- What preparation and/or assignment(s) will students complete in order to learn from the case? (e.g., read the case prior to class, watch a case video prior to class, post to a CourseWorks discussion, submit a brief memo, complete a short writing assignment to check students’ understanding of a case, take on a specific role, prepare to present a critique during in-class discussion).

Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press.

Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846

Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Garvin, D.A. (2003). Making the Case: Professional Education for the world of practice. Harvard Magazine. September-October 2003, Volume 106, Number 1, 56-107.

Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29.

Golich, V.L.; Boyer, M; Franko, P.; and Lamy, S. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. Pew Case Studies in International Affairs. Institute for the Study of Diplomacy.

Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK.

Herreid, C.F. (2011). Case Study Teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. No. 128, Winder 2011, 31 – 40.

Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries.

Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar

Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153.

Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative.

Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002

Schiano, B. and Andersen, E. (2017). Teaching with Cases Online . Harvard Business Publishing.

Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44.

Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1).

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Additional resources

Teaching with Cases , Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Features “what is a teaching case?” video that defines a teaching case, and provides documents to help students prepare for case learning, Common case teaching challenges and solutions, tips for teaching with cases.

Promoting excellence and innovation in case method teaching: Teaching by the Case Method , Christensen Center for Teaching & Learning. Harvard Business School.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science . University of Buffalo.

A collection of peer-reviewed STEM cases to teach scientific concepts and content, promote process skills and critical thinking. The Center welcomes case submissions. Case classification scheme of case types and teaching methods:

- Different types of cases: analysis case, dilemma/decision case, directed case, interrupted case, clicker case, a flipped case, a laboratory case.

- Different types of teaching methods: problem-based learning, discussion, debate, intimate debate, public hearing, trial, jigsaw, role-play.

Columbia Resources

Resources available to support your use of case method: The University hosts a number of case collections including: the Case Consortium (a collection of free cases in the fields of journalism, public policy, public health, and other disciplines that include teaching and learning resources; SIPA’s Picker Case Collection (audiovisual case studies on public sector innovation, filmed around the world and involving SIPA student teams in producing the cases); and Columbia Business School CaseWorks , which develops teaching cases and materials for use in Columbia Business School classrooms.

Center for Teaching and Learning

The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) offers a variety of programs and services for instructors at Columbia. The CTL can provide customized support as you plan to use the case method approach through implementation. Schedule a one-on-one consultation.

Office of the Provost

The Hybrid Learning Course Redesign grant program from the Office of the Provost provides support for faculty who are developing innovative and technology-enhanced pedagogy and learning strategies in the classroom. In addition to funding, faculty awardees receive support from CTL staff as they redesign, deliver, and evaluate their hybrid courses.

The Start Small! Mini-Grant provides support to faculty who are interested in experimenting with one new pedagogical strategy or tool. Faculty awardees receive funds and CTL support for a one-semester period.

Explore our teaching resources.

- Blended Learning

- Contemplative Pedagogy

- Inclusive Teaching Guide

- FAQ for Teaching Assistants

- Metacognition

CTL resources and technology for you.

- Overview of all CTL Resources and Technology

- The origins of this method can be traced to Harvard University where in 1870 the Law School began using cases to teach students how to think like lawyers using real court decisions. This was followed by the Business School in 1920 (Garvin, 2003). These professional schools recognized that lecture mode of instruction was insufficient to teach critical professional skills, and that active learning would better prepare learners for their professional lives. ↩

- Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries. ↩

- Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press. ↩

- Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative. ↩

- Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK. ↩

- Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846 ↩

- Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153. ↩

- Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44. ↩

- Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1). ↩

- Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002 ↩

- Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar ↩

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

- What is Case-Based Learning? Meaning, Examples, Applications

Case-based learning is a teaching method in which learners are presented with real or hypothetical cases that simulate real-life scenarios to solve them. It enables students to identify the root cause of a problem, and explore various solutions using their knowledge and skills from lessons and research to select the best solution.

Using the case-based learning approach allows students to fine-tune their problem-solving and critical-thinking skills to develop authentic solutions and recommendations to real-life problems. This allows students to solve real-world problems rather than simply memorize answers.

This learning method is also very flexible, as it can be used in both physical and virtual classes. It also has many applications including reviewing legal arguments, business case studies, medical treatments, and more.

What is Case-Based Learning?

Case-based learning, also known as the case method, teaches and assesses students by simulating real-life scenarios. It helps students in acquiring relevant knowledge by posing hypothetical or even real-world problems for them to solve.

Case-based learning enables the understanding of complex problems through the use of previous solutions and optimized recommendations. It’s an effective learning method because it helps students develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

It also helps students in developing their research and collaboration skills to solve new and complex problems. Case-based learning is commonly used in professional fields such as medicine, law, business, engineering, and journalism.

Case studies are typically done in groups or as a class, but educators may occasionally allow students to choose case studies individually.

Why Use Case-Based Learning?

The case-based learning method is a highly recommended teaching method because it allows students to apply classroom and research knowledge and skills to solve real-world problems. Here are the major benefits of using case-based learning:

Authenticity

Learning from real cases helps students understand how their knowledge can be applied to real problems, which makes their learning experience more meaningful.

Students are more likely to solve problems from their perspectives because they are learning from real-life scenarios, which allows them to apply their critical thinking and creativity skills.

Problem-Solving

Using case studies requires students to analyze the scenarios critically and come up with authentic solutions. The process of studying the cases and applying their knowledge and skills to solve the given problem requires students to leverage their critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

When students practice problem-solving skills through case studies regularly they improve their ability to process information quickly and come up with efficient solutions to similar problems. This skill is especially useful in most professional fields because it allows you to deal with unforeseen circumstances and provide appropriate solutions on the spot.

Transferability

Case-based learning allows students to apply their knowledge and skills from lessons, assignments, and assessments to solve new and unfamiliar problems. This makes their knowledge and skills transferable; they can easily adapt to a new environment effectively.

Collaboration

Case studies often include group work, which allows students to practice teamwork and help them develop collaboration skills. Knowing how to collaborate effectively within and across teams is one of the most important soft skills professionals need to build and run organizations effectively.

It also allows students to learn important life skills they can adopt in real-life scenarios.

Flexibility

Case-based learning requires students to provide authentic solutions; the solution is frequently adaptable; it can be used to solve more than one case. It also allows for more flexible learning experiences, such as e-learning and hybrid learning.

What Is the Purpose of a Case Study in Education?

The primary goal of using case studies in learning is to provide students with the opportunity to apply their knowledge and skills to solve real-world problems. They are often used in professions that require adaptable solutions, such as healthcare, law, business, and engineering.

Case-based learning can take place at all levels of education, from primary to tertiary. Starting this type of learning earlier allows students to quickly hone their problem-solving, critical thinking, and creativity skills, which will become muscle memory when they become professionals.

Here are other goals educators achieve with case studies:

- Build students’ problem-solving and critical-thinking skills

- Foster students’ Collaboration skills

- Equip students to solve real-life problems

- Help students develop transferable skills and knowledge to solve new problems.

Teaching Strategies for Case-Based Learning

Case-based learning is only effective when it is used correctly to help students develop problem-solving and analytical skills. Here are some tips for creating an effective case-based learning experience:

Introduce the Case

The first step in creating a successful case-based learning experience is to introduce the case study into the classroom. Be the first to provide information about the case to your students; this helps them understand the context of the case study and where to apply the knowledge and skills gained from it.

Incorporating case studies into relevant lessons is an excellent way to introduce them. For example, if you want to do a case study on the effect of brand voice, include how to create a great brand voice in a lesson plan.

Ask Guiding Questions

When presenting case studies to students, include guiding questions that capture the purpose of the case study. This will direct their critical thinking toward the knowledge and skills you want them to gain from the case study.

Guiding questions also help students avoid being overburdened with information they don’t need, which can lead to intellectual fatigue.

Encourage Teamwork

Group assignments help students develop collaboration skills, which will help them understand how to navigate team collaborations in their future fields. It also allows them to brainstorm multiple ideas at once and analyze them to see if they are feasible solutions.

Provide Feedback

When students present their solutions and recommendations, provide feedback on their approach to help them solve future problems more effectively. Giving students feedback allows them to continuously hone their problem-solving skills while following guiding instructions.

Foster Classroom Discussions

Group discussions and general classroom discussions provide students with different perspectives on how people solve problems. It also enables them to identify what they could do better to achieve a more optimized solution.

Classroom discussion also helps to engage students by allowing them to share their thoughts and provide feedback on what they have learned from the case study.

Encourage Reflection

Encourage students to think about what they learned from the case study and how they will apply what they learned to solve future problems.

What Are the Advantages of Case-Based Learning?

Active learning.

Case-based learning motivates students to apply their knowledge and skills to develop solutions and recommendations. It also encourages students to participate in group discussions which promote both inside and outside classroom collaboration.

As a result, rather than passively listening in class, students are actively learning and looking for ways to use the information to determine authentic solutions to the problem.

Relevant Knowledge

Another major benefit of case studies is that they help students in developing industry and real-world relevant skills and knowledge. The case studies about real-life problems provide students with perspectives on the problems they can expect in their fields in the future and how to deal with them.

Students can focus on acquiring the skills and knowledge that will help them understand real-world cases and how to solve them.

Traditional learning methods, on the other hand, provide students with a wealth of information and limited guidelines for problem-solving. Students may become confused and unable to achieve the lesson’s goal if they are overwhelmed by the volume of information.

Personalized Learning Experience

Case-based learning allows students to learn at their pace, gain relevant skills, and experiment with different problem-solving strategies. This allows students to investigate problem solutions from their point of view, making their learning experience more engaging.

It also allows students to delve deeply into topics that interest them during case studies to come up with unique solutions to the given problem. This strengthens students’ research skills, which will likely come in handy in their future careers.

Develop Students’ Communication Skills

Higher knowledge retention rates.

Most students passively learn with traditional learning, making it difficult for students to recall complex and unfamiliar concepts. Case-based learning, on the other hand, encourages students to actively participate in class, research, and collaborate with their peers, resulting in a more personalized and active learning experience.

The likelihood of students forgetting skills and information acquired through personalized learning is much lower than when they are simply passively listening in class.

What Are the Disadvantages of Case-Based Learning?

While case-based learning is an excellent teaching style that helps students develop the skills they need to be exceptional in their professional fields, it does have some drawbacks. The following are some of the disadvantages of using case-based learning:

Time and Resource Intensive

Of course, all teaching methods necessitate time and resources, but case-based learning necessitates even more from educators. Unlike traditional teaching methods, educators must spend more time preparing course materials, selecting relevant case studies, grouping students, holding discussions, and more.

Limited Scope

Case-based learning has the edge of focusing on relevant cases, which narrows students’ knowledge and skills. However, this has a disadvantage in that students only cover very specific aspects of a topic and end up knowing nothing about other equally important aspects.

Student Readiness

While the goal of case-based learning is to help students fine-tune their problem-solving and critical thinking skills without swamping them with information, it can backfire if the students aren’t ready for authentic cases and assessments.

So, before assigning real-life cases educators must ensure that their students are well-developed enough to understand concepts and their relevance in real-life.

Group Dynamics

Case-based learning encourages teamwork, which allows students to get answers faster and practice their interpersonal and collaborative skills. But if the group dynamic isn’t working because, for example, the managers are inactive and work is delegated to a small number of group members, the group tasks may end up slowing down the students.

Applications of Case-Based Learning

Business education.

Business students often use case studies to analyze real-world problems and solutions.

Law Education

Case studies are often used in law to help students understand legal cases and how to prepare legal arguments.

Healthcare students use case studies to understand patient conditions and develop the best course of treatment.

Professional Development

Case-based learning is a highly effective method for teaching professionals new and relevant skills. They are already familiar with real-world problems; case-based learning allows them to carefully review these cases and find effective solutions that will help them excel in their field.

Examples of Case Based Learning in Education

1. medical treatment.

Medical students are studying the case of a patient with a rare medical condition. The supervisor gives the medical students a list of symptoms, history, and genetic predispositions that could cause the condition and asks them to diagnose the patient and recommend a treatment plan.

2. Environmental Engineering

Students are given a case study of a fictional town that suffers from severe air pollution as a result of CO2 emissions from a nearby cement factory; the town also has a large kaolin deposit. The students are to create kaolin adsorbents to capture CO2.

3. Education

A college education professor gives students a case study of a school that has been struggling with low student achievement for three years. The students must determine what happened in the last three years to cause the low performance and how to develop a strategy to improve the student’s performance.

Case-based learning is a teaching and learning method that helps students develop problem-solving and critical thinking skills to solve real-world problems. It can be used in various fields, including business, law, healthcare, and education.

Although case-based earning is flexible and helpful to students in developing the skills they need to be professionals, it can be resource-intensive and time-consuming for educators.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- active classroom

- case-based learning

- classroom management techniques

- critical thinking skills

- problem solving skills

- Moradeke Owa

You may also like:

Classroom Management Techniques for Effective Teachers

In this article, we’ll review what classroom management means, its components, and how you can create your own classroom management plan

What is Andragogy: Definition, Principles & Application

Introduction Andragogy, or adult learning theory, is a field of study that focuses on how adults learn. It is an interdisciplinary field...

Technology Enhanced Learning: What It Is & Examples

With technology becoming such an integral part of our lives, it is impractical to teach students without it. The major problem with...

Active learning Techniques for Teachers: Strategies & Examples

In this article, we will look at active learning, its importance, techniques for classrooms and its characteristics.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

- Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Case-based learning.

Case-based learning (CBL) is an established approach used across disciplines where students apply their knowledge to real-world scenarios, promoting higher levels of cognition (see Bloom’s Taxonomy ). In CBL classrooms, students typically work in groups on case studies, stories involving one or more characters and/or scenarios. The cases present a disciplinary problem or problems for which students devise solutions under the guidance of the instructor. CBL has a strong history of successful implementation in medical, law, and business schools, and is increasingly used within undergraduate education, particularly within pre-professional majors and the sciences (Herreid, 1994). This method involves guided inquiry and is grounded in constructivism whereby students form new meanings by interacting with their knowledge and the environment (Lee, 2012).

There are a number of benefits to using CBL in the classroom. In a review of the literature, Williams (2005) describes how CBL: utilizes collaborative learning, facilitates the integration of learning, develops students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to learn, encourages learner self-reflection and critical reflection, allows for scientific inquiry, integrates knowledge and practice, and supports the development of a variety of learning skills.

CBL has several defining characteristics, including versatility, storytelling power, and efficient self-guided learning. In a systematic analysis of 104 articles in health professions education, CBL was found to be utilized in courses with less than 50 to over 1000 students (Thistlethwaite et al., 2012). In these classrooms, group sizes ranged from 1 to 30, with most consisting of 2 to 15 students. Instructors varied in the proportion of time they implemented CBL in the classroom, ranging from one case spanning two hours of classroom time, to year-long case-based courses. These findings demonstrate that instructors use CBL in a variety of ways in their classrooms.

The stories that comprise the framework of case studies are also a key component to CBL’s effectiveness. Jonassen and Hernandez-Serrano (2002, p.66) describe how storytelling:

Is a method of negotiating and renegotiating meanings that allows us to enter into other’s realms of meaning through messages they utter in their stories,

Helps us find our place in a culture,

Allows us to explicate and to interpret, and

Facilitates the attainment of vicarious experience by helping us to distinguish the positive models to emulate from the negative model.

Neurochemically, listening to stories can activate oxytocin, a hormone that increases one’s sensitivity to social cues, resulting in more empathy, generosity, compassion and trustworthiness (Zak, 2013; Kosfeld et al., 2005). The stories within case studies serve as a means by which learners form new understandings through characters and/or scenarios.

CBL is often described in conjunction or in comparison with problem-based learning (PBL). While the lines are often confusingly blurred within the literature, in the most conservative of definitions, the features distinguishing the two approaches include that PBL involves open rather than guided inquiry, is less structured, and the instructor plays a more passive role. In PBL multiple solutions to the problem may exit, but the problem is often initially not well-defined. PBL also has a stronger emphasis on developing self-directed learning. The choice between implementing CBL versus PBL is highly dependent on the goals and context of the instruction. For example, in a comparison of PBL and CBL approaches during a curricular shift at two medical schools, students and faculty preferred CBL to PBL (Srinivasan et al., 2007). Students perceived CBL to be a more efficient process and more clinically applicable. However, in another context, PBL might be the favored approach.

In a review of the effectiveness of CBL in health profession education, Thistlethwaite et al. (2012), found several benefits:

Students enjoyed the method and thought it enhanced their learning,

Instructors liked how CBL engaged students in learning,

CBL seemed to facilitate small group learning, but the authors could not distinguish between whether it was the case itself or the small group learning that occurred as facilitated by the case.

Other studies have also reported on the effectiveness of CBL in achieving learning outcomes (Bonney, 2015; Breslin, 2008; Herreid, 2013; Krain, 2016). These findings suggest that CBL is a vehicle of engagement for instruction, and facilitates an environment whereby students can construct knowledge.

Science – Students are given a scenario to which they apply their basic science knowledge and problem-solving skills to help them solve the case. One example within the biological sciences is two brothers who have a family history of a genetic illness. They each have mutations within a particular sequence in their DNA. Students work through the case and draw conclusions about the biological impacts of these mutations using basic science. Sample cases: You are Not the Mother of Your Children ; Organic Chemisty and Your Cellphone: Organic Light-Emitting Diodes ; A Light on Physics: F-Number and Exposure Time

Medicine – Medical or pre-health students read about a patient presenting with specific symptoms. Students decide which questions are important to ask the patient in their medical history, how long they have experienced such symptoms, etc. The case unfolds and students use clinical reasoning, propose relevant tests, develop a differential diagnoses and a plan of treatment. Sample cases: The Case of the Crying Baby: Surgical vs. Medical Management ; The Plan: Ethics and Physician Assisted Suicide ; The Haemophilus Vaccine: A Victory for Immunologic Engineering

Public Health – A case study describes a pandemic of a deadly infectious disease. Students work through the case to identify Patient Zero, the person who was the first to spread the disease, and how that individual became infected. Sample cases: The Protective Parent ; The Elusive Tuberculosis Case: The CDC and Andrew Speaker ; Credible Voice: WHO-Beijing and the SARS Crisis

Law – A case study presents a legal dilemma for which students use problem solving to decide the best way to advise and defend a client. Students are presented information that changes during the case. Sample cases: Mortgage Crisis Call (abstract) ; The Case of the Unpaid Interns (abstract) ; Police-Community Dialogue (abstract)

Business – Students work on a case study that presents the history of a business success or failure. They apply business principles learned in the classroom and assess why the venture was successful or not. Sample cases: SELCO-Determining a path forward ; Project Masiluleke: Texting and Testing to Fight HIV/AIDS in South Africa ; Mayo Clinic: Design Thinking in Healthcare

Humanities - Students consider a case that presents a theater facing financial and management difficulties. They apply business and theater principles learned in the classroom to the case, working together to create solutions for the theater. Sample cases: David Geffen School of Drama

Recommendations

Finding and Writing Cases

Consider utilizing or adapting open access cases - The availability of open resources and databases containing cases that instructors can download makes this approach even more accessible in the classroom. Two examples of open databases are the Case Center on Public Leadership and Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Case Program , which focus on government, leadership and public policy case studies.

- Consider writing original cases - In the event that an instructor is unable to find open access cases relevant to their course learning objectives, they may choose to write their own. See the following resources on case writing: Cooking with Betty Crocker: A Recipe for Case Writing ; The Way of Flesch: The Art of Writing Readable Cases ; Twixt Fact and Fiction: A Case Writer’s Dilemma ; And All That Jazz: An Essay Extolling the Virtues of Writing Case Teaching Notes .

Implementing Cases

Take baby steps if new to CBL - While entire courses and curricula may involve case-based learning, instructors who desire to implement on a smaller-scale can integrate a single case into their class, and increase the number of cases utilized over time as desired.

Use cases in classes that are small, medium or large - Cases can be scaled to any course size. In large classes with stadium seating, students can work with peers nearby, while in small classes with more flexible seating arrangements, teams can move their chairs closer together. CBL can introduce more noise (and energy) in the classroom to which an instructor often quickly becomes accustomed. Further, students can be asked to work on cases outside of class, and wrap up discussion during the next class meeting.

Encourage collaborative work - Cases present an opportunity for students to work together to solve cases which the historical literature supports as beneficial to student learning (Bruffee, 1993). Allow students to work in groups to answer case questions.

Form diverse teams as feasible - When students work within diverse teams they can be exposed to a variety of perspectives that can help them solve the case. Depending on the context of the course, priorities, and the background information gathered about the students enrolled in the class, instructors may choose to organize student groups to allow for diversity in factors such as current course grades, gender, race/ethnicity, personality, among other items.

Use stable teams as appropriate - If CBL is a large component of the course, a research-supported practice is to keep teams together long enough to go through the stages of group development: forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning (Tuckman, 1965).

Walk around to guide groups - In CBL instructors serve as facilitators of student learning. Walking around allows the instructor to monitor student progress as well as identify and support any groups that may be struggling. Teaching assistants can also play a valuable role in supporting groups.

Interrupt strategically - Only every so often, for conversation in large group discussion of the case, especially when students appear confused on key concepts. An effective practice to help students meet case learning goals is to guide them as a whole group when the class is ready. This may include selecting a few student groups to present answers to discussion questions to the entire class, asking the class a question relevant to the case using polling software, and/or performing a mini-lesson on an area that appears to be confusing among students.

Assess student learning in multiple ways - Students can be assessed informally by asking groups to report back answers to various case questions. This practice also helps students stay on task, and keeps them accountable. Cases can also be included on exams using related scenarios where students are asked to apply their knowledge.

Barrows HS. (1996). Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: a brief overview. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 68, 3-12.

Bonney KM. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains. Journal of Microbiology and Biology Education, 16(1): 21-28.

Breslin M, Buchanan, R. (2008) On the Case Study Method of Research and Teaching in Design. Design Issues, 24(1), 36-40.

Bruffee KS. (1993). Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and authority of knowledge. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Herreid CF. (2013). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science, edited by Clyde Freeman Herreid. Originally published in 2006 by the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA); reprinted by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) in 2013.

Herreid CH. (1994). Case studies in science: A novel method of science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 23(4), 221–229.

Jonassen DH and Hernandez-Serrano J. (2002). Case-based reasoning and instructional design: Using stories to support problem solving. Educational Technology, Research and Development, 50(2), 65-77.

Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435, 673-676.

Krain M. (2016) Putting the learning in case learning? The effects of case-based approaches on student knowledge, attitudes, and engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 27(2), 131-153.

Lee V. (2012). What is Inquiry-Guided Learning? New Directions for Learning, 129:5-14.

Nkhoma M, Sriratanaviriyakul N. (2017). Using case method to enrich students’ learning outcomes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 18(1):37-50.

Srinivasan et al. (2007). Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: Effects of a major curricular shift at two institutions. Academic Medicine, 82(1): 74-82.

Thistlethwaite JE et al. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 23. Medical Teacher, 34, e421-e444.

Tuckman B. (1965). Development sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384-99.

Williams B. (2005). Case-based learning - a review of the literature: is there scope for this educational paradigm in prehospital education? Emerg Med, 22, 577-581.

Zak, PJ (2013). How Stories Change the Brain. Retrieved from: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

Instructional Enhancement Fund

The Instructional Enhancement Fund (IEF) awards grants of up to $500 to support the timely integration of new learning activities into an existing undergraduate or graduate course. All Yale instructors of record, including tenured and tenure-track faculty, clinical instructional faculty, lecturers, lectors, and part-time acting instructors (PTAIs), are eligible to apply. Award decisions are typically provided within two weeks to help instructors implement ideas for the current semester.

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning routinely supports members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Benefits of Learning Through the Case Study Method

- 28 Nov 2023

While several factors make HBS Online unique —including a global Community and real-world outcomes —active learning through the case study method rises to the top.

In a 2023 City Square Associates survey, 74 percent of HBS Online learners who also took a course from another provider said HBS Online’s case method and real-world examples were better by comparison.

Here’s a primer on the case method, five benefits you could gain, and how to experience it for yourself.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is the Harvard Business School Case Study Method?

The case study method , or case method , is a learning technique in which you’re presented with a real-world business challenge and asked how you’d solve it. After working through it yourself and with peers, you’re told how the scenario played out.

HBS pioneered the case method in 1922. Shortly before, in 1921, the first case was written.

“How do you go into an ambiguous situation and get to the bottom of it?” says HBS Professor Jan Rivkin, former senior associate dean and chair of HBS's master of business administration (MBA) program, in a video about the case method . “That skill—the skill of figuring out a course of inquiry to choose a course of action—that skill is as relevant today as it was in 1921.”

Originally developed for the in-person MBA classroom, HBS Online adapted the case method into an engaging, interactive online learning experience in 2014.

In HBS Online courses , you learn about each case from the business professional who experienced it. After reviewing their videos, you’re prompted to take their perspective and explain how you’d handle their situation.

You then get to read peers’ responses, “star” them, and comment to further the discussion. Afterward, you learn how the professional handled it and their key takeaways.

HBS Online’s adaptation of the case method incorporates the famed HBS “cold call,” in which you’re called on at random to make a decision without time to prepare.

“Learning came to life!” said Sheneka Balogun , chief administration officer and chief of staff at LeMoyne-Owen College, of her experience taking the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program . “The videos from the professors, the interactive cold calls where you were randomly selected to participate, and the case studies that enhanced and often captured the essence of objectives and learning goals were all embedded in each module. This made learning fun, engaging, and student-friendly.”

If you’re considering taking a course that leverages the case study method, here are five benefits you could experience.

5 Benefits of Learning Through Case Studies

1. take new perspectives.

The case method prompts you to consider a scenario from another person’s perspective. To work through the situation and come up with a solution, you must consider their circumstances, limitations, risk tolerance, stakeholders, resources, and potential consequences to assess how to respond.

Taking on new perspectives not only can help you navigate your own challenges but also others’. Putting yourself in someone else’s situation to understand their motivations and needs can go a long way when collaborating with stakeholders.

2. Hone Your Decision-Making Skills

Another skill you can build is the ability to make decisions effectively . The case study method forces you to use limited information to decide how to handle a problem—just like in the real world.

Throughout your career, you’ll need to make difficult decisions with incomplete or imperfect information—and sometimes, you won’t feel qualified to do so. Learning through the case method allows you to practice this skill in a low-stakes environment. When facing a real challenge, you’ll be better prepared to think quickly, collaborate with others, and present and defend your solution.

3. Become More Open-Minded

As you collaborate with peers on responses, it becomes clear that not everyone solves problems the same way. Exposing yourself to various approaches and perspectives can help you become a more open-minded professional.

When you’re part of a diverse group of learners from around the world, your experiences, cultures, and backgrounds contribute to a range of opinions on each case.

On the HBS Online course platform, you’re prompted to view and comment on others’ responses, and discussion is encouraged. This practice of considering others’ perspectives can make you more receptive in your career.

“You’d be surprised at how much you can learn from your peers,” said Ratnaditya Jonnalagadda , a software engineer who took CORe.

In addition to interacting with peers in the course platform, Jonnalagadda was part of the HBS Online Community , where he networked with other professionals and continued discussions sparked by course content.

“You get to understand your peers better, and students share examples of businesses implementing a concept from a module you just learned,” Jonnalagadda said. “It’s a very good way to cement the concepts in one's mind.”

4. Enhance Your Curiosity

One byproduct of taking on different perspectives is that it enables you to picture yourself in various roles, industries, and business functions.

“Each case offers an opportunity for students to see what resonates with them, what excites them, what bores them, which role they could imagine inhabiting in their careers,” says former HBS Dean Nitin Nohria in the Harvard Business Review . “Cases stimulate curiosity about the range of opportunities in the world and the many ways that students can make a difference as leaders.”

Through the case method, you can “try on” roles you may not have considered and feel more prepared to change or advance your career .

5. Build Your Self-Confidence

Finally, learning through the case study method can build your confidence. Each time you assume a business leader’s perspective, aim to solve a new challenge, and express and defend your opinions and decisions to peers, you prepare to do the same in your career.

According to a 2022 City Square Associates survey , 84 percent of HBS Online learners report feeling more confident making business decisions after taking a course.

“Self-confidence is difficult to teach or coach, but the case study method seems to instill it in people,” Nohria says in the Harvard Business Review . “There may well be other ways of learning these meta-skills, such as the repeated experience gained through practice or guidance from a gifted coach. However, under the direction of a masterful teacher, the case method can engage students and help them develop powerful meta-skills like no other form of teaching.”

How to Experience the Case Study Method

If the case method seems like a good fit for your learning style, experience it for yourself by taking an HBS Online course. Offerings span seven subject areas, including:

- Business essentials

- Leadership and management

- Entrepreneurship and innovation

- Finance and accounting

- Business in society

No matter which course or credential program you choose, you’ll examine case studies from real business professionals, work through their challenges alongside peers, and gain valuable insights to apply to your career.

Are you interested in discovering how HBS Online can help advance your career? Explore our course catalog and download our free guide —complete with interactive workbook sections—to determine if online learning is right for you and which course to take.

About the Author

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. and Distinguished Service University Professor. He served as the 10th dean of Harvard Business School, from 2010 to 2020.

Partner Center

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved July 17, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Search type

University Wide

Faculty / School Portals

- Instructional Strategies

Case-Based Learning

What is case-based learning.

Using a case-based approach engages students in discussion of specific scenarios that resemble or typically are real-world examples. This method is learner-centered with intense interaction between participants as they build their knowledge and work together as a group to examine the case. The instructor's role is that of a facilitator while the students collaboratively analyze and address problems and resolve questions that have no single right answer.

Clyde Freeman Herreid provides eleven basic rules for case-based learning.

- Tells a story.

- Focuses on an interest-arousing issue.

- Set in the past five years

- Creates empathy with the central characters.

- Includes quotations. There is no better way to understand a situation and to gain empathy for the characters

- Relevant to the reader.

- Must have pedagogic utility.

- Conflict provoking.

- Decision forcing.

- Has generality.

Why Use Case-Based Learning?

To provide students with a relevant opportunity to see theory in practice. Real world or authentic contexts expose students to viewpoints from multiple sources and see why people may want different outcomes. Students can also see how a decision will impact different participants, both positively and negatively.

To require students to analyze data in order to reach a conclusion. Since many assignments are open-ended, students can practice choosing appropriate analytic techniques as well. Instructors who use case-based learning say that their students are more engaged, interested, and involved in the class.

To develop analytic, communicative and collaborative skills along with content knowledge. In their effort to find solutions and reach decisions through discussion, students sort out factual data, apply analytic tools, articulate issues, reflect on their relevant experiences, and draw conclusions they can relate to new situations. In the process, they acquire substantive knowledge and develop analytic, collaborative, and communication skills.

Many faculty also use case studies in their curriculum to teach content, connect students with real life data, or provide opportunities for students to put themselves in the decision maker's shoes.

Teaching Strategies for Case-Based Learning

By bringing real world problems into student learning, cases invite active participation and innovative solutions to problems as they work together to reach a judgment, decision, recommendation, prediction or other concrete outcome.

The Campus Instructional Consulting unit at Indiana University has created a great resource for case-based learning. The following is from their website which we have permission to use.

Formats for Cases

- “Finished” cases based on facts: for analysis only, since the solution is indicated or alternate solutions are suggested.

- “Unfinished” open-ended cases: the results are not yet clear (either because the case has not come to a factual conclusion in real life, or because the instructor has eliminated the final facts.) Students must predict, make choices and offer suggestions that will affect the outcome.

- Fictional cases: entirely written by the instructor—can be open-ended or finished. Cautionary note: the case must be both complex enough to mimic reality, yet not have so many “red herrings” as to obscure the goal of the exercise.

- Original documents: news articles, reports with data and statistics, summaries, excerpts from historical writings, artifacts, literary passages, video and audio recordings, ethnographies, etc. With the right questions, these can become problem-solving opportunities. Comparison between two original documents related to the same topic or theme is a strong strategy for encouraging both analysis and synthesis. This gives the opportunity for presenting more than one side of an argument, making the conflicts more complex.

Managing a Case Assignment

- Design discussions for small groups. 3-6 students are an ideal group size for setting up a discussion on a case.

- Design the narrative or situation such that it requires participants to reach a judgment, decision, recommendation, prediction or other concrete outcome. If possible, require each group to reach a consensus on the decision requested.

- Structure the discussion. The instructor should provide a series of written questions to guide small group discussion. Pay careful attention to the sequencing of the questions. Early questions might ask participants to make observations about the facts of the case. Later questions could ask for comparisons, contrasts, and analyses of competing observations or hypotheses. Final questions might ask students to take a position on the matter. The purpose of these questions is to stimulate, guide or prod (but not dictate) participants’ observations and analyses. The questions should be impossible to answer with a simple yes or no.

- Debrief the discussion to compare group responses. Help the whole class interprets and understand the implications of their solutions.

- Allow groups to work without instructor interference. The instructor must be comfortable with ambiguity and with adopting the non-traditional roles of witness and resource, rather than authority.

Designing Case Study Questions

Cases can be more or less “directed” by the kinds of questions asked. These kinds of questions can be appended to any case, or could be a handout for participants unfamiliar with case studies on how to approach one.

- What is the situation—what do you actually know about it from reading the case? (Distinguishes between fact and assumptions under critical understanding)