Historic Documents

"ask not what your country can do for you".

We observe today not a victory of party, but a celebration of freedom — symbolizing an end, as well as a beginning — signifying renewal, as well as change. For I have sworn before you and Almighty God the same solemn oath our forebears prescribed nearly a century and three quarters ago. The world is very different now. For man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe — the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state, but from the hand of God. We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans — born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage — and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this Nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world. Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty. This much we pledge — and more. To those old allies whose cultural and spiritual origins we share, we pledge the loyalty of faithful friends. United, there is little we cannot do in a host of cooperative ventures. Divided, there is little we can do — for we dare not meet a powerful challenge at odds and split asunder. To those new States whom we welcome to the ranks of the free, we pledge our word that one form of colonial control shall not have passed away merely to be replaced by a far more iron tyranny. We shall not always expect to find them supporting our view. But we shall always hope to find them strongly supporting their own freedom — and to remember that, in the past, those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside. To those peoples in the huts and villages across the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required — not because the Communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich. To our sister republics south of our border, we offer a special pledge — to convert our good words into good deeds — in a new alliance for progress — to assist free men and free governments in casting off the chains of poverty. But this peaceful revolution of hope cannot become the prey of hostile powers. Let all our neighbours know that we shall join with them to oppose aggression or subversion anywhere in the Americas. And let every other power know that this Hemisphere intends to remain the master of its own house. To that world assembly of sovereign states, the United Nations, our last best hope in an age where the instruments of war have far outpaced the instruments of peace, we renew our pledge of support — to prevent it from becoming merely a forum for invective — to strengthen its shield of the new and the weak — and to enlarge the area in which its writ may run. Finally, to those nations who would make themselves our adversary, we offer not a pledge but a request: that both sides begin anew the quest for peace, before the dark powers of destruction unleashed by science engulf all humanity in planned or accidental self-destruction. We dare not tempt them with weakness. For only when our arms are sufficient beyond doubt can we be certain beyond doubt that they will never be employed. But neither can two great and powerful groups of nations take comfort from our present course — both sides overburdened by the cost of modern weapons, both rightly alarmed by the steady spread of the deadly atom, yet both racing to alter that uncertain balance of terror that stays the hand of mankind's final war. So let us begin anew — remembering on both sides that civility is not a sign of weakness, and sincerity is always subject to proof. Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate. Let both sides explore what problems unite us instead of belabouring those problems which divide us. Let both sides, for the first time, formulate serious and precise proposals for the inspection and control of arms — and bring the absolute power to destroy other nations under the absolute control of all nations. Let both sides seek to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors. Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths, and encourage the arts and commerce. Let both sides unite to heed in all corners of the earth the command of Isaiah — to "undo the heavy burdens -. and to let the oppressed go free." And if a beachhead of cooperation may push back the jungle of suspicion, let both sides join in creating a new endeavour, not a new balance of power, but a new world of law, where the strong are just and the weak secure and the peace preserved. All this will not be finished in the first 100 days. Nor will it be finished in the first 1,000 days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin. In your hands, my fellow citizens, more than in mine, will rest the final success or failure of our course. Since this country was founded, each generation of Americans has been summoned to give testimony to its national loyalty. The graves of young Americans who answered the call to service surround the globe. Now the trumpet summons us again — not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need; not as a call to battle, though embattled we are — but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out, "rejoicing in hope, patient in tribulation" — a struggle against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself. Can we forge against these enemies a grand and global alliance, North and South, East and West, that can assure a more fruitful life for all mankind? Will you join in that historic effort? In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility — I welcome it. I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation. The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavour will light our country and all who serve it — and the glow from that fire can truly light the world. And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country. My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man. Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you. With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God's work must truly be our own.

- Daniel Webster's "Seventh of March" Speech

- FDR's Infamy Speech

This public-domain content provided by the Independence Hall Association , a nonprofit organization in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, founded in 1942. Publishing electronically as ushistory.org. On the Internet since July 4, 1995.

Kennedy's Inaugural Address

Support ushistory.org and buy a poster for your wall!

Click here!

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Who Wrote JFK’s Inaugural?

Does it matter.

I n my childhood imagination, John F. Kennedy slotted somewhere below DiMaggio and above De Niro in a loose ranking of latter-day American deities. When I was just a toddler, the late president left a lasting impression on me, literally, after I pulled a terracotta reproduction of Robert Berks’ iconic sculpture—weighing considerably less, thankfully, than the 3,000-pound original—down from a sideboard and onto my head. On my bedroom wall hung two plaques, one a list of “coincidences”—many trivial, some factually incorrect—between the political careers and assassinations of Kennedy and Abraham Lincoln. The other, also arguably incorrect, was a portrait of Kennedy embossed on black metal, staring out above his famous entreaty in all caps:

“ASK NOT WHAT YOUR COUNTRY CAN DO FOR YOU … ASK WHAT YOU CAN DO FOR YOUR COUNTRY.” J.F.K.

It’s no secret that presidents often speak words they themselves did not write. When George Washington delivered the very first inaugural address, on Apr. 30, 1789, he was reading from a reworked draft composed by his friend and frequent ghostwriter James Madison. In 1861, with the country on the brink of civil war, Lincoln pitched his address to a restive South and planned to end on the crudely formed question, “Shall it be peace or sword?” That is, until his soon-to-be Secretary of State William Seward suggested a less combative, more poetic conjuring of “mystic chords” and “the better angel guardian angel of the nation,” which Lincoln then uncrossed and altered to “the better angels of our nature.” Small matter, perhaps. We don’t require that our politicians be great writers, after all, only effective communicators, and they in turn sometimes benefit from a misattribution in perpetuity of someone else’s eloquence.

In Kennedy’s case, the gift of rhetoric was owed largely to his longtime counsel and legislative aide, Ted Sorensen, who later became his principal speechwriter after the two developed a simpatico understanding of oratory. In his 1965 biography Kennedy , Sorensen wrote:

As the years went on, and I came to know what he thought on each subject as well as how he wished to say it, our style and standard became increasingly one. When the volume of both his speaking and my duties increased in the years before 1960, we tried repeatedly but unsuccessfully to find other wordsmiths who could write for him in the style to which he was accustomed. The style of those whom we tried may have been very good. It may have been superior. But it was not his.

Kennedy believed his inaugural address should “set a tone for the era about to begin,” an era in which he imagined foreign policy and global issues—not least the specter of nuclear annihilation—would be his chief concern. But while Sorensen may have been the only person who could reliably give voice to Kennedy’s ideas, the coming speech was too historic to entrust to merely one man. On Dec. 23, 1960, less than a month before Kennedy would stand on the East Portico of the Capitol to take the oath of office, Sorensen sent a block telegram to 10 men, soliciting “specific themes” and “language to articulate these themes whether it takes one page or ten pages.”

Although Sorensen was without question the chief architect of Kennedy’s inaugural, the final draft contained contributions or borrowings from, among others, the Old Testament, the New Testament, Lincoln, Kennedy rival and two-time Democratic presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson, Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith, historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and, we believe, Kennedy himself.

But an unequivocal puzzling out of exactly who wrote what is, with some exceptions, impossible. Late in his life, Sorensen, who died in 2010, admitted to destroying his own hand-written first draft of the speech at the request of Jacqueline Kennedy, who was deeply protective of her husband’s legacy. When pressed further, Sorensen was famously coy. If asked whether he wrote the speech’s most enduring line, for example, he would answer simply, “Ask not.” During an interview with Richard Tofel, author of Sounding the Trumpet: The Making of John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address , Sorensen seemed to suggest that preservation of the myth was more essential than any single truth about the man:

I recognize that I have some obligation to history, but all these years I have tried to make clear that President Kennedy was the principal author of all his speeches and articles. If I say otherwise, that diminishes him, and I don’t want to diminish him.

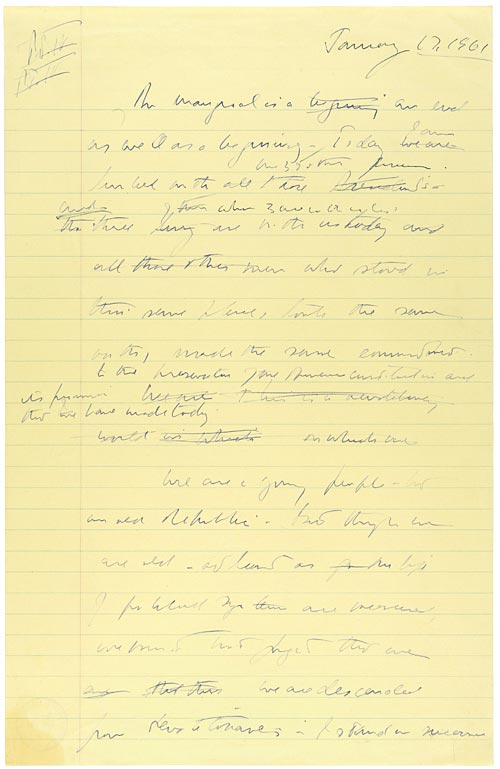

If Jacqueline Kennedy and Ted Sorensen were willing to tear up what may have been the only categorical proof of Sorensen’s primary authorship, President Kennedy—in an incident that can only be described as out-and-out deception—was willing to lie. On Jan. 16 and 17, 1961, at the Kennedy vacation compound in Palm Beach, Fla., Sorensen and JFK polished a near-final draft of the inaugural address and even typed it up on carbon paper. Later on the 17 th , the two flew back to Washington aboard Kennedy’s private plane, the Caroline , with Time correspondent Hugh Sidey, whose reporting on the president veered between the credulous and the hagiographic.

At some point during the flight, Kennedy began scribbling on a yellow legal pad in front of Sidey, as if working out just then his thoughts about the speech. What Kennedy in fact wrote was some of the precise language that had already been committed to typescript. During an interview with historian Thurston Clarke, author of Ask Not: The Inauguration of John F. Kennedy and the Speech that Changed America , Sidey recalled thinking, “My God! It’s three days before the inauguration, and he hasn’t progressed beyond a first draft?”

Not only had Kennedy progressed well beyond that, but he and Sorensen had nailed down what we know to be the penultimate version. Even worse, Kennedy later copied out by hand six or seven more pages—directly, one assumes, from the typewritten copy—and dated it “Jan 17, 1961.” After JFK’s assassination, the pages were displayed in what would become his presidential library and identified as an early draft.

There are a total of 51 sentences in the only text of the inaugural that now matters to the world, the speech as read on Jan. 20, 1961, though it can’t be said, without at least some conjecture, that Kennedy was the principal author of any one of them. I asked Tofel, who is now president of ProPublica, what it means that Kennedy may have been a mere messenger of what many Americans consider to be one of the most pivotal speeches of the 20 th century, second only to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream”:

Kennedy lives on in our history not because of, frankly, enormous accomplishment—he died, at the most generous, before he could accomplish a great deal—but because of his ability to articulate, I think, our most profound values and highest aspirations much better than anyone has before or since. And that is his. It is not Sorensen’s. It is not Galbraith’s. It is not Schlesinger’s. We are talking about him at great length here 50 years after his death, and I believe we are doing that because of the power of words. And in that sense they are his words.

Should Sorensen’s original draft or other lost fragments ever materialize, whatever they might say is surely no match for the shrine that history has erected and the symbolism that hung on the walls of my childhood bedroom. And in that sense, those words belong to me.

Read more in Slate on the 50 th anniversary of the JFK assassination.

Ted Sorensen on the Kennedy Style of Speech-Writing

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In his final book, Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History (2008), Ted Sorensen offered a prediction:

"I have little doubt that, when my time comes, my obituary in the New York Times ( misspelling my last name once again) will be captioned: 'Theodore Sorenson, Kennedy Speechwriter.'"

On November 1, 2010, the Times got the spelling right: "Theodore C. Sorensen, 82, Kennedy Counselor, Dies." And though Sorensen did serve as a counselor and alter ego to John F. Kennedy from January 1953 to November 22, 1963, "Kennedy Speechwriter" was indeed his defining role.

A graduate of the University of Nebraska's law school, Sorensen arrived in Washington, D.C. "unbelievably green," as he later admitted. "I had no legislative experience, no political experience. I'd never written a speech . I'd hardly been out of Nebraska."

Nevertheless, Sorensen was soon called on to help write Senator Kennedy's Pulitzer Prize-winning book Profiles in Courage (1955). He went on to co-author some of the most memorable presidential speeches of the last century, including Kennedy's inaugural address , the "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech, and the American University commencement address on peace.

Though most historians agree that Sorensen was the primary author of these eloquent and influential speeches, Sorensen himself maintained that Kennedy was the "true author." As he said to Robert Schlesinger, "If a man in a high office speaks words which convey his principles and policies and ideas and he's willing to stand behind them and take whatever blame or therefore credit go with them, [the speech is] his" ( White House Ghosts: Presidents and Their Speechwriters , 2008).

In Kennedy , a book published two years after the president's assassination, Sorensen spelled out some of the distinctive qualities of the "Kennedy style of speech-writing." You'd be hard-pressed to find a more sensible list of tips for speakers.

While our own orations may not be quite as momentous as a president's, many of Kennedy's rhetorical strategies are worth emulating, regardless of the occasion or the size of the audience . So the next time you address your colleagues or classmates from the front of the room, keep these principles in mind.

The Kennedy Style of Speech-Writing

The Kennedy style of speech-writing--our style, I am not reluctant to say, for he never pretended that he had time to prepare first drafts for all his speeches--evolved gradually over the years. . . . We were not conscious of following the elaborate techniques later ascribed to these speeches by literary analysts. Neither of us had any special training in composition, linguistics or semantics. Our chief criterion was always audience comprehension and comfort, and this meant: (1) short speeches, short clauses and short words, wherever possible; (2) a series of points or propositions in numbered or logical sequence wherever appropriate; and (3) the construction of sentences, phrases and paragraphs in such a manner as to simplify, clarify and emphasize. The test of a text was not how it appeared to the eye, but how it sounded to the ear. His best paragraphs, when read aloud, often had a cadence not unlike blank verse--indeed at times key words would rhyme . He was fond of alliterative sentences, not solely for reasons of rhetoric but to reinforce the audience's recollection of his reasoning. Sentences began, however incorrect some may have regarded it, with "And" or "But" whenever that simplified and shortened the text. His frequent use of dashes was of doubtful grammatical standing--but it simplified the delivery and even the publication of a speech in a manner no comma, parenthesis or semicolon could match. Words were regarded as tools of precision, to be chosen and applied with a craftsman's care to whatever the situation required. He liked to be exact. But if the situation required a certain vagueness, he would deliberately choose a word of varying interpretations rather than bury his imprecision in ponderous prose. For he disliked verbosity and pomposity in his own remarks as much as he disliked them in others. He wanted both his message and his language to be plain and unpretentious, but never patronizing. He wanted his major policy statements to be positive, specific and definite, avoiding the use of "suggest," "perhaps" and "possible alternatives for consideration." At the same time, his emphasis on a course of reason--rejecting the extremes of either side--helped produce the parallel construction and use of contrasts with which he later became identified. He had a weakness for one unnecessary phrase: "The harsh facts of the matter are . . ."--but with few other exceptions his sentences were lean and crisp. . . . He used little or no slang, dialect, legalistic terms, contractions, clichés, elaborate metaphors or ornate figures of speech. He refused to be folksy or to include any phrase or image he considered corny, tasteless or trite. He rarely used words he considered hackneyed: "humble," "dynamic," "glorious." He used none of the customary word fillers (e.g., "And I say to you that is a legitimate question and here is my answer"). And he did not hesitate to depart from strict rules of English usage when he thought adherence to them (e.g., "Our agenda are long") would grate on the listener's ear. No speech was more than 20 to 30 minutes in duration. They were all too short and too crowded with facts to permit any excess of generalities and sentimentalities. His texts wasted no words and his delivery wasted no time. (Theodore C. Sorensen, Kennedy . Harper & Row, 1965. Reprinted in 2009 as Kennedy: The Classic Biography )

To those who question the value of rhetoric, dismissing all political speeches as "mere words" or "style over substance," Sorensen had an answer. "Kennedy's rhetoric when he was president turned out to be a key to his success," he told an interviewer in 2008. "His 'mere words' about Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba helped resolve the worst crisis the world has ever known without the U.S. having to fire a shot."

Similarly, in a New York Times op-ed published two months before his death, Sorensen countered several "myths" about the Kennedy-Nixon debates, including the view that it was "style over substance, with Kennedy winning on delivery and looks." In the first debate, Sorensen argued, "there was far more substance and nuance than in what now passes for political debate in our increasingly commercialized, sound-bite Twitter-fied culture, in which extremist rhetoric requires presidents to respond to outrageous claims ."

To learn more about the rhetoric and oratory of John Kennedy and Ted Sorensen, have a look at Thurston Clarke's Ask Not: The Inauguration of John F. Kennedy and the Speech That Changed America, published by Henry Holt in 2004 and now available in a Penguin paperback.

- What Is a Rhetorical Device? Definition, List, Examples

- Figure of Speech: Definition and Examples

- Why Did Lee Harvey Oswald Kill JFK?

- The Top 20 Figures of Speech

- How Many U.S. Presidents Have Been Assassinated?

- JFK's Accomplishments in Education and the Space Program

- Invented Ethos (Rhetoric)

- The 5 Canons of Classical Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples of Ethos in Classical Rhetoric

- Effective Speech Writing

- Biography of John F. Kennedy Jr.

- Definition and Examples of Hypocrisis in Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples of Anti-Rhetoric

- 20th Century American Speeches as Literary Texts

- 10 Things to Know About John F. Kennedy

- Pause (Speech and Writing)

Our Last Great Adventure

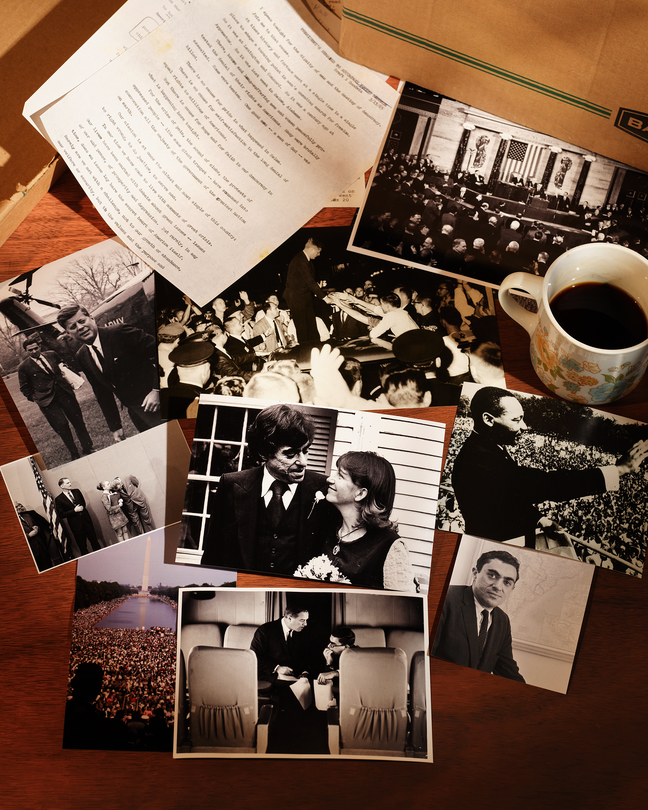

My husband, Richard Goodwin, drafted landmark speeches for JFK and LBJ. Late in life, we dived into his archives, searching for vivid traces of our hopeful youth.

O ne summer morning, seven months after he had turned 80, my husband, Dick Goodwin, came down the stairs, clumps of shaving cream on his earlobes, singing, “The corn is as high as an elephant’s eye,” from the musical Oklahoma!

“Why so chipper?” I asked.

“I had a flash,” he said, looking over the headlines of the three newspapers I had laid out for him on the breakfast table in our home in Concord, Massachusetts. Putting them aside, he started writing down numbers. “Three times eight is 24. Three times 80 is 240.”

“Is that your revelation?” I asked.

Explore the May 2024 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

“Look, my 80-year life span occupies more than a third of our republic’s history. That means that our democracy is merely three ‘Goodwins’ long.”

I tried to suppress a smile.

“Doris, one Goodwin ago, when I was born, we were in the midst of the Great Depression. Pearl Harbor happened on December 7, 1941, my 10th birthday. It ruined my whole party! If we go back two Goodwins, we find our Concord Village roiled in furor over the Fugitive Slave Act. A third Goodwin will bring us back to the point that, if we went out our front door, took a left, and walked down the road, we might just see those embattled farmers and witness the commencement of the Revolutionary War.”

He glanced at the newspapers and went to his study, on the far side of the house. An hour later, he was back to read aloud a paragraph he had just written:

Three spans of one long life traverse the whole of our short national history. One certain thing that a look backward at the vicissitudes of our country’s story suggests is that massive and sweeping change will come. And it can come swiftly. Whether or not it is healing and inclusive change depends on us. As ever, such change will generally percolate from the ground up, as in the days of the American Revolution, the anti-slavery movement, the progressive movement, the civil-rights movement, the women’s movement, the gay-rights movement, the environmental movement. From the long view of my life, I see how history turns and veers. The end of our country has loomed many times before. America is not as fragile as it seems.

“It’s now or never,” he said, announcing that the time had finally come to unpack and examine the 300 boxes of material he had dragged along with us during 40 years of marriage. Dick had saved everything relating to his time in public service in the 1960s as a speechwriter for and adviser to John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Robert F. Kennedy, and Eugene McCarthy: reams of White House memos, diaries, initial drafts of speeches annotated by presidents and presidential hopefuls, newspaper clippings, scrapbooks, photographs, menus—a mass that would prove to contain a unique and comprehensive archive of a pivotal era. Dick had been involved in a remarkable number of defining moments .

He was the junior speechwriter, working under Ted Sorensen, during JFK’s 1960 presidential campaign. He was in the room to help the candidate prepare for his first televised debate with Richard Nixon. In the box labeled DEBATE were pages torn from a yellow pad upon which Kennedy had scrawled requests for information or clarification. Dick was in the White House when the president’s coffin returned from Dallas, and he was responsible for making arrangements to install an eternal flame at the grave site. He was at LBJ’s side during the summit of his historic achievements in civil rights and the Great Society. He was in New Hampshire during McCarthy’s crusade against the Vietnam War, and in the hospital room when Robert Kennedy died in Los Angeles. He was a central figure in the debate over the peace plank during the mayhem of the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago.

For years, however, Dick had resisted opening these boxes. They were from a time he recalled with both elation and a crushing sense of loss. The assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert Kennedy; the war in Vietnam; the riots in the cities; the violence on college campuses—all the turmoil had drawn a dark curtain on the entire decade. He had wanted only to look ahead.

Doris Kearns Goodwin: The divided legacy of Lyndon B. Johnson

Now he had resolved to go back in time. “I’m an old guy,” he said. “If I have any wisdom to dispense, I’d better start dispensing.” A friend, Deb Colby, became his research assistant, and together they began the slow process of arranging the boxes in chronological order. Once that preliminary task had been completed, Dick was hopeful that there might be something of a book in the material he had uncovered. He wanted me to go back with him to the very first box and work our way through all of them. I was not only his wife but a historian.

“I need your help,” he said. “Jog my memory, ask me questions, see what we can learn.” I joined him in his study, and we started on the first group of boxes. We made a deal to try to spend time on this project every weekend to see what might come of it.

Our last great adventure together was about to begin.

Some 30 boxes contained materials relating to JFK’s 1960 presidential campaign. From September 4 to November 8, 1960, Dick was a member of the small entourage that flew across the country with Kennedy for more than two months of nonstop campaigning. The first-ever private plane used by a presidential candidate during a campaign, the Caroline (named for Kennedy’s daughter) had been modified into a luxurious executive office. It had plush couches and four chairs that could be converted into small beds—two of them for Dick and Ted Sorensen. Kennedy had his own suite of bedrooms farther aft.

“You were all so young,” I marveled to Dick after looking up the ages of the team. The candidate was 43; Bobby Kennedy, 34; Ted Sorensen, 32. “And you—”

“Twenty-eight,” he interrupted, adding, “Youngest of the lot.”

After midnight on October 14, 1960, the Caroline landed at Willow Run Airport, near Ypsilanti, Michigan. Three weeks remained until Election Day. Everyone was bone-tired as the caravan set out for Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan.

As they approached the Michigan campus, there was little to suggest that one of the most enduring moments of the campaign was about to occur. It was nearly 2 a.m. by the time the caravan reached the Michigan Union, where Kennedy was scheduled to catch a few hours of sleep before starting on a whistle-stop tour of the state. No one in the campaign had expected to find as many as 10,000 students waiting in the streets to greet the candidate. Neither Ted nor Dick had prepared remarks for the occasion.

As Kennedy ascended the steps of the union, the crowd chanted his name. He turned around, smiled, and introduced himself as “a graduate of the Michigan of the East—Harvard University.” He then began speaking extemporaneously, falling back on his familiar argument that the 1960 campaign presaged the outcome of the race between communism and the free world. But suddenly, he caught a second wind and swerved from his stock stump speech. He asked the crowd of young people what they might be willing to contribute for the sake of the country.

How many of you who are going to be doctors are willing to spend your days in Ghana? Technicians or engineers, how many of you are willing to work in the Foreign Service and spend your lives traveling around the world? On your willingness to do that, not merely to serve one year or two in the service, but on your willingness to contribute part of your life to this country, I think will depend the answer whether a free society can compete.

What stirred Kennedy to these spontaneous questions is not clear. Weariness, intuition, or—most likely, I suspect—because they had lingered in his mind after the third debate with Nixon, which had taken place only hours before and had been focused on whether America’s prestige in the world was rising or falling relative to that of Communist nations. The concept of students volunteering for public service in Africa and Asia might well bolster goodwill for America in countries wavering (as Kennedy had put it) “on the razor edge of decision” between the free world and the Communist system.

Drawing his impromptu speech to a close, Kennedy confessed that he had come to the union on this cold and early morning simply to go to bed. The words elicited raucous laughter and applause that continued to mount when he threw down a final challenge: “May I just say in conclusion that this university is not maintained by its alumni, by the state, merely to help its graduates have an economic advantage in the life struggle. There is certainly a greater purpose, and I’m sure you recognize it.”

Kennedy’s remarks lasted only three minutes—“the longest short speech,” he called it. Yet something extraordinary transpired: The students took up the challenge he posed. Led by two graduate students, Alan and Judith Guskin, they organized, they held meetings , they sent letters and telegrams to the campaign asking Kennedy to develop plans for a corps of American volunteers overseas. Within a week, 1,000 students had signed petitions pledging to give two years of their lives to help people in developing countries.

When Dick and Ted learned of the student petitions, they redrafted an upcoming Kennedy speech on foreign policy to be delivered at the Cow Palace, in San Francisco, working in a formal proposal for “a peace corps of talented young men and women.” We pulled the speech from one of the boxes. Dick’s hand can be readily detected in the closing lines, which used a favorite quote of his from the Greek philosopher Archimedes. “Give me a fulcrum,” Archimedes said, “and I will move the world.” Dick would later invoke the same line in a historic speech by Robert Kennedy in South Africa.

Two days after JFK’s speech at the Cow Palace, the candidate was flying to Toledo, Ohio . He sent word to the Guskins that he would like to meet them and see their petitions, crammed with names. A photo captures the moment when an eager Judy Guskin clutches the petitions before she presents them to the weary-eyed Kennedy, who is reaching out in anticipation.

Later, Dick and Ted had coffee with Judy and Alan. They talked of the Peace Corps and the election, by then only five days away. Nixon had immediately denounced the idea of a Peace Corps—“ a Kiddie Corps ,” he and others called it—warning that it would become a haven for draft dodgers. But for Judy and Alan, as for nearly a quarter of a million others, the Peace Corps would prove a transformative experience. The Guskins were in the first group to travel to Thailand, where Judy taught English and organized a teacher-training program. Alan set up a program at the same school in psychology and educational research. Returning home, they served as founders of the VISTA program, LBJ’s domestic version of the Peace Corps.

For Dick, the Peace Corps, more than any other venture of the Kennedy years, represented the essence of the administration’s New Frontier vision. After JFK’s inauguration, as a member of the White House staff, Dick joined the task force that formally launched the Peace Corps. He was barely older than the typical volunteer.

SUMMER 1963

Dick and I often talked, half-jokingly, half-seriously, about the various occasions when we were in the same place at the same time before we finally met—in the summer of 1972, when he arrived at the Harvard building where I had my office as an assistant professor. I knew who he was. I had heard that he was brilliant, brash, mercurial, arrogant, a fascinating figure. He was more than a decade older than me. His appearance was intriguing: curly, disheveled black hair; thick, unruly eyebrows; a pockmarked face; and several large cigars in the pocket of his casual shirt. We began a conversation that day about LBJ, literature, philosophy, astronomy, sex, gossip, and the Red Sox that would continue for 46 years.

The first occasion when we could have crossed paths but didn’t was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, on August 28, 1963. It was not surprising that we didn’t meet, given that some 250,000 people had gathered for the event.

I was spending the summer before my senior year at Colby College as an intern at the State Department. All government employees had been given the day off and been cautioned to stay home, warned that it wasn’t safe. I was 20 years old—I had no intention of staying home. But I still remember the nervous excitement I felt that morning as I walked with a group of friends toward the Washington Monument. We had been planning to attend the march for weeks.

A state of emergency had been declared as people descended on the capital from all over the country. Marchers arriving by bus and train on Wednesday morning were encouraged to depart the city proper by that night. Hospitals canceled elective surgery to make space in the event of mass casualties. The Washington Senators baseball game was postponed . Liquor stores and bars were closed. We learned that thousands of National Guardsmen had been mobilized to bolster the D.C. police force. Thousands of additional soldiers stood ready across the Potomac, in Virginia.

I asked Dick if these precautions had seemed a bit much. He explained that Kennedy was worried that if things got out of hand, the civil-rights bill he had introduced in June could unravel, and “take his administration with it.” Though government workers were discouraged from attending the march, Dick grabbed Bill Moyers, the deputy Peace Corps director, and headed toward the National Mall.

So there Dick and I were, unknown to each other, both moving along with what seemed to be all of humanity toward the Reflecting Pool and the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, where the march would culminate. I carried a poster stapled to a stick: Catholics, Protestants and Jews Unite in the Struggle for Civil Rights . A sense that I was connected to something larger than myself took hold.

It’s easy to cast a cynical eye upon this youthful exultation, to view it in retrospect as sentimental idealism, but the feelings were genuine, and they were profound. At the start of the march, I had wondered what proportion of the vast throng was white (it was later estimated at 25 percent). By the time I returned to my rooming house in Foggy Bottom, I had forgotten all about calculations and proportions. I had set out that morning apprehensive, yet had been lifted up by the most joyful day of public unity and community I had ever experienced.

Facing the Lincoln Memorial, with Martin Luther King’s soaring “I Have a Dream” speech still ahead, we all held hands, our voices rising as we sang “We Shall Overcome”—the hymn that had long instilled purpose and courage in the foot soldiers of the civil-rights movement. That moment made as deep an impression on Dick as it did on me.

SPRING 1964

During our years of archival sifting, Dick and I, like two nosy neighbors on a party line, tracked down transcripts of conversations recorded by Lyndon Johnson’s secret taping system.

“How splendid to be flies on the wall, to eavesdrop across the decades!” That was Dick’s gleeful response after I read him a transcript of a telephone call between the president and Bill Moyers—by then a special assistant to Johnson—on the evening of March 9, 1964. Here Dick and I were, he in his 80s and I in my 70s, finally privy to the very conversation that, previously unbeknownst to Dick, had led him from the nucleus of the Kennedy camp, through a period of confusion and drift in the aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination, to the highest circles of the Johnson administration.

The phone call began with Johnson grousing about the dreary language in the poverty message that he soon planned to deliver to Congress. Passionately invested in the poverty program, he was dissatisfied with the drafts he had seen and was now pressing Moyers to find “whoever’s the best explainer of this that you can get.”

Johnson: Since [Ted] Sorensen left, we’ve got no one that can be phonetic, and get rhythm … Moyers: The only person I know who can—and I’m reluctant to ask him to get involved in this, because right now it’s in our little circle—is Goodwin. Johnson: Why not just ask him if he can’t put some sex in it? I’d ask him if he couldn’t put some rhyme in it and some beautiful Churchillian phrases and take it and turn it out for us tomorrow … If he will, then we’ll use it. But ask him if he can do it in confidence. Call him tonight and say, “I want to bring it to you now. I’ve got it ready to go, but he wants you to work on it if you can do it without getting it into a column.” Moyers: All right, I’ll call him right now. Johnson: Tell him that I’m pretty impressed with him. He’s working on Latin America already; see how he’s getting along. But can he put the music to it?

As we reached the end of the conversation, Dick swore that he could hear Johnson’s voice clearly in his mind’s ear. “Lyndon’s a kind of poet,” Dick said. “What a unique recipe for high oratory: rhyme, sex, music, phonetics, and beautiful Churchillian phrases.”

We both knew him so well: Dick because he worked with him intimately in the White House and on the 1964 campaign, and I because, after a time as a White House fellow, I’d joined a small team in Texas to help him go through his papers, conduct research, and draft his memoir. From the time Dick and I met, we often referred to the president simply as “Lyndon” when speaking with each other. There are a lot of Johnsons, but there was only one Lyndon .

SPRING 1965

A year and a half after the March on Washington, the memory of its transcendent finale returned to become the heart of the most important speech Dick ever drafted. We pulled a copy of the draft, some notes, the final speech, and newspaper clippings from one of the Johnson boxes.

The moment Dick stepped into the West Wing on the morning of March 15, 1965, he sensed an unusual hubbub and tension. Pacing back and forth in a dither outside Dick’s second-floor office was the White House special assistant Jack Valenti. Normally full of glossy good cheer, Valenti pounced on Dick before he could even open his office door.

The night before, Johnson had decided to give a televised address to a joint session of Congress calling for a voting-rights bill. He believed that the conscience of America had been fired by the events at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, a week earlier, when peaceful marchers had been attacked by Alabama state troopers wielding clubs, nightsticks, and whips.

“He needs the speech from you right away,” Valenti said.

“From me! Why didn’t you tell me yesterday? I’ve lost the entire night,” Dick responded.

“It was a mistake, my mistake,” Valenti acknowledged. He explained that the first words out of the president’s mouth that morning had been “How is Goodwin doing on the speech?” and Valenti had told him he’d assigned it to another aide, Horace Busby. Johnson had erupted, “The hell you did! Get Dick to do it, and now !”

The speech had to be finished before 6 p.m., Valenti told Dick, in order to be loaded onto the teleprompter. Dick looked at his watch. Nine hours away. Valenti asked Dick if there was anything—anything at all—he could get for him.

“Serenity,” Dick replied, “a globe of serenity. I can’t be disturbed. If you want to know how it’s coming, ask my secretary.”

“I didn’t want to think about time passing,” Dick recalled to me. “I lit a cigar, looked at my watch, took the watch off my wrist, and put it on the desk beside my typewriter. Another puff of my cigar, and I took the watch and put it away in my desk drawer.”

“The pressure would have short-circuited me,” I said. “I never had the makings of a good speechwriter or journalist. History is more patient.”

“Well,” Dick said, laughing, “miss the speech deadline and those pages are only scraps of paper.”

Dick examined the folder of notes Valenti had given him. Johnson wanted no uncertainty about where he stood. To deny fellow Americans the right to vote was simply and unequivocally wrong. He wanted the speech to be affirmative and hopeful. He would be sending a bill to Congress to protect the right to vote for all Americans, and he wanted this speech to speed public sentiment along.

In the year since Dick had started working at the White House, he had listened to Johnson talk for hundreds of hours—on planes and in cars, during meals in the mansion and at his ranch, in the swimming pool and over late-night drinks. He understood Johnson’s deeply held convictions about civil rights, and he had the cadences of his speech in his ear. The speechwriter’s job, Dick knew, was to clarify, heighten, and polish a speaker’s convictions in the speaker’s own language and natural rhythms. Without that authenticity, the emotional current of the speech would never hit home.

I knew that Dick often searched for a short, arresting sentence to begin every speech or article he wrote. On this day, he surely found it:

I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy … At times, history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.

No sooner would Dick pull a page out of his typewriter and give it to his secretary than Valenti would somehow materialize, a nerve-worn courier, eager to express pages from Dick’s secretary into the president’s anxious hands. Johnson’s edits and penciled notations were incorporated into the text while he awaited the next installment, lashing out at everyone within range—everyone except Dick.

The speech was no lawyer’s brief debating the merits of the bill to be sent to Congress. It was a credo, a declaration of what we are as a nation and who we are as a people—a redefining moment in our history brought forth by the civil-rights movement.

The real hero of this struggle is the American Negro. His actions and protests, his courage to risk safety and even to risk his life, have awakened the conscience of this nation … He has called upon us to make good the promise of America. And who among us can say that we would have made the same progress were it not for his persistent bravery, and his faith in American democracy?

As the light shifted across his office, Dick became aware that the day suddenly seemed to be rushing by. He opened the desk drawer, peered at the face of his watch, took a deep breath, and slammed the drawer shut. He walked outside to get air and refresh his mind.

In the distance, Dick heard demonstrators demanding that Johnson send federal troops to Selma. Dick hurried back to his office. Something seemed forlorn about the receding voices—such a great contrast to the spirited resolve of the March on Washington. Loud and clear, the words We shall overcome sounded in his head.

It was after the 6-o’clock deadline when the phone in Dick’s office rang for the first time that day. The voice at the other end was so relaxed and soothing that Dick hardly recognized it as the president’s.

“Far and away,” Dick told me, “the gentlest tones I ever heard from Lyndon.”

“You remember, Dick,” Johnson said, “that one of my first jobs after college was teaching young Mexican Americans in Cotulla. I told you about that down at the ranch. I thought you might want to put in a reference to that.” Then he ended the call: “Well, I won’t keep you, Dick. It’s getting late.”

“When I finished the draft,” Dick recalled, “I felt perfectly blank. It was done. It was beyond revision. It was dark outside, and I checked my wrist to see what time it was, remembered I had hidden my watch away from my sight, retrieved it from the drawer, and put it back on.”

There was nothing left to do but shave, grab a sandwich, and stroll over to the mansion. There, greeted by an exorbitantly grateful Valenti, Dick hardly had the energy to talk. Before he knew it, he was sitting with the president in his limousine on the way to the Capitol.

A hush filled the chamber as the president began to speak. Watching from the well of the House, an exhausted Dick marveled at Johnson’s emotional gravity. The president’s somber, urgent, relentlessly driving delivery demonstrated a conviction and exposed a vulnerability that surpassed anything Dick had seen in him before.

There is no constitutional issue here. The command of the Constitution is plain. There is no moral issue. It is wrong—deadly wrong—to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country. There is no issue of states’ rights or national rights. There is only the struggle for human rights … This time, on this issue, there must be no delay, or no hesitation or no compromise with our purpose … But even if we pass this bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches in every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And — we — shall — overcome.

The words came staccato, each hammered and sharply distinct from the others. In Selma, Alabama, Martin Luther King had gathered with friends and colleagues to watch the president’s speech. At this climactic moment when Johnson took up the banner of the civil-rights movement, John Lewis witnessed tears rolling down King’s cheeks.

The time had come for the president to draw on his own experience, to tell the formative story he had mentioned to Dick on the phone.

My first job after college was as a teacher in Cotulla, Texas, in a small Mexican American school. Few of them could speak English, and I couldn’t speak much Spanish. My students were poor, and they often came to class without breakfast, hungry. And they knew, even in their youth, the pain of prejudice. They never seemed to know why people disliked them. But they knew it was so, because I saw it in their eyes. I often walked home late in the afternoon, after the classes were finished, wishing there was more that I could do … Somehow you never forget what poverty and hatred can do when you see its scars on the hopeful face of a young child. I never thought then, in 1928, that I would be standing here in 1965. It never even occurred to me in my fondest dreams that I might have the chance to help the sons and daughters of those students and to help people like them all over this country. But now I do have that chance—and I’ll let you in on a secret: I mean to use it.

The audience stood to deliver perhaps the largest ovation of the night.

I told Dick that I had read an account that when Johnson was later asked who had written the speech, he pulled out a photo of his 20-year-old self surrounded by a cluster of kids, his former students in Cotulla. “ They did,” he said, indicating the whole lot of them.

“You know,” Dick said with a smile, “in the deepest sense, that might just be the truth.”

“God, how I loved Lyndon Johnson that night,” Dick remembered. He long treasured a pen that Johnson gave him after signing the Voting Rights Act. “How unimaginable it would have been to think that in two years time I would, like many others who listened that night, go into the streets against him.”

Nor could I have imagined, as I talked excitedly with my graduate-school friends at Harvard after listening to the speech—certain that a new tide was rising in our country—that only a few years later I would work directly for the president who delivered it. Or that 10 years later, I would marry the man who drafted it.

SPRING 2015

One morning, two years into our project, I found Dick mumbling and grumbling as he worked his way along the two-tiered row of archival containers. “Look how many boxes we have left!” he exclaimed. “See Jackie and Bobby here, more Lyndon, riots and protests, McCarthy, anti-war marches, assassinations. Look at them!”

“I guess we better pick up our pace,” I offered.

“You’re a lot younger than me. Shovel more coal into our old train and let’s go.”

This determination to steam ahead had only increased as Dick approached his mid-80s. A pacemaker regulated his heart, he needed a hearing aid, his balance was compromised. One afternoon, he tripped on the way to feeding the fish in our backyard. He sat down on a bench, a pensive expression on his face. I asked if he was okay.

“I heard time’s winged chariot hurrying near,” he said, quoting Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress,” but then added, “Maybe it was only the hiss of my hearing aid.”

From the June 1971 issue: Richard Goodwin on the social theory of Herbert Marcuse

“Who would you bet on?” he asked me one night at bedtime. “Who will be finished first—me or the boxes?”

Our work on the boxes kept him anchored with a purpose even after he was diagnosed with the cancer that took his life in 2018.

I realize now that we were both in the grip of an enchanted thought—that so long as we had more boxes to unpack, more work to do, his life, my life, our life together would not be finished. So long as we were learning, laughing, discussing the boxes, we were alive. If a talisman is an object thought to have magical powers and to bring luck, the boxes and the future book they held had become ours.

*Lead image sources (left to right from top) : Richard N. Goodwin Papers / Courtesy of Briscoe Center for American History; Cecil Stoughton / Courtesy of LBJ Library; Gibson Moss / Alamy; Associated Press; Yoichi Okamoto / Courtesy of LBJ Library; Marc Peloquin / Courtesy of Doris Kearns Goodwin; Heritage Images / Getty; Bob Parent / Getty; Paul Conklin / Getty; Bettmann / Getty

This essay has been adapted from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s . It appears in the May 2024 print edition with the headline “The Speechwriter.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Share this on:

Theodore sorensen, jfk's speechwriter, has died.

- Ted Sorensen was 82

- Sorensen was a top aide in John F. Kennedy's White House

- He helped pen some of the most recognizable speeches in American political history

(CNN) -- Theodore C. Sorensen, a close adviser and speechwriter to President John F. Kennedy, has died, the White House said Sunday.

Though he wore a number of hats in his relationship with Kennedy and later in life, he is best known publicly as the wordsmith who helped put Kennedy's ideas to paper in what remain some of the most recognizable speeches in American political history.

The youngest top official in the Kennedy White House, Sorensen was an influential policy adviser and a presidential confidante.

He served as special counsel and speechwriter to Kennedy from 1961 to 1963, and participated in secret White House meetings during the Cuban Missile Crisis, according to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Sorensen was a key aide on Kennedy's 1960 presidential campaign and had earlier served as a speechwriter and assistant to Kennedy during his Senate years.

After Kennedy's 1963 assassination, Sorensen helped to shape the young president's legacy, writing four books on the Kennedy years, including the 1965 volume "Kennedy."

Sorensen also played an important role in helping the future president shape 1956's "Profiles in Courage."

A 2008 memoir, "Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History," was a candid look at his relationship with Kennedy.

Sorensen was often asked whether he wrote the classic line from Kennedy's 1961 inaugural address, "Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country."

"Having no satisfactory answer, I long ago started answering the oft-repeated question as to its authorship with the smiling retort: 'Ask not,' " Sorensen wrote in "Counselor."

The lawyer later served as special counsel to President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1963 and 1964.

Sorensen played a major role in completing Sen. Robert F. Kennedy's book "Thirteen Days," based on notes left after the latter's 1968 assassination.

"I got to know Ted after he endorsed my campaign early on," President Barack Obama said in a statement Sunday. "He was just as I hoped he'd be -- just as quick-witted, just as serious of purpose, just as determined to keep America true to our highest ideals."

A native of Lincoln, Nebraska, Sorensen received his law degree in 1951, according to the publication Current Biography. He soon became an administrative assistant to Kennedy, then a newly elected U.S. senator from Massachusetts.

A chief goal was getting Kennedy elected president. Sorensen's efforts included helping Kennedy overcome anti-Catholic prejudice during the successful 1960 campaign.

Sorensen's later career included serving as an attorney in Manhattan, attending Democratic conventions and serving as a presidential and political adviser, according to the JFK Library.

Most Popular

Fine art from an iphone the best instagram photos from 2014, after ivf shock, mom gives birth to two sets of identical twins, inside north korea: water park, sacred birth site and some minders, 10 top destinations to visit in 2015, what really scares terrorists.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Kennedy Aide Ted Sorensen Dies At 82

David Folkenflik

Ted Sorensen, adviser and speechwriter to President John Kennedy, died over the weekend. He was 82.

Copyright © 2010 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Ted Sorensen, JFK's Speechwriter: A Tribute

Tokyo-based writer, speaker, author

Just yesterday I was reading about Ted Sorensen and his involvement with choosing the head of America's propaganda agency, USIA, after Kennedy's election in 1960.

Sorensen, who died today at age 82, put together an outline of the qualifications needed for telling America's story to the world:

- Experience in world affairs and knowledge of foreign peoples

- Should comprehend the 'revolution of rising expectations' throughout the world, and its impact on U.S. foreign policy

- Pragmatic, open-minded, and sensitive to international political events, without being naïve

- Understand the potentialities of propaganda while being aware of its limitations

It was, as Alexander Kendrick writes, "an excellent, almost a hand-tooled description of Edward R. Murrow."

Theodore Sorensen we all know as the great speechwriter, but he was so much more. Sorensen shared Kennedy's commitment to psychological warfare and foreign information programs. Shortly after JFK accepted the nomination for President, he asked the American people:

Can we carry through in an age where we will witness not only new breakthroughs in weapons of destruction but also a race for mastery of the sky and the rain, the ocean and the tides, the far side of space and the inside of men's minds?

It's hard to imagine but Ted Sorensen was a 32-year-old member of the New Frontier, the youngest member of the inner circle of 30- and 40-somethings that dominated Kennedy's cabinet. Murrow, at 52, joked that he was the "Satchel Paige of the Kennedy administration."

Ted's brother Thomas C. Sorensen, who died in 1997, was part of the USIA "troika" that included Sorensen as Director of Policy, Edward R. Murrow as Director and Donald M. Wilson as Deputy Director. Tom Sorenson penned one of the best books on that era called The Word War: The Story of American Propaganda , which includes several chapters on Murrow during the Kennedy years. What a talented brother duo they made.

I take pause today to remember Ted Sorensen for penning one of the greatest presidential speeches of the 20th century, Kennedy's American University Commencement Address on June 10, 1963. Kennedy's post-Cuban Missile Crisis posture was to open up dialogue with the Soviet Union. The United States would call on the USSR to enter into more peaceful negotiations and disarmament talks. Kennedy chose this speech to make his long-distance détente call:

Some say that it is useless to speak of peace or world law or world disarmament, and that it will be useless until the leaders of the Soviet Union adopt a more enlightened attitude. I hope they do. I believe we can help them do it. But I also believe that we must reexamine our own attitudes, as individuals and as a Nation, for our attitude is as essential as theirs. And every graduate of this school, every thoughtful citizen who despairs of war and wishes to bring peace, should begin by looking inward, by examining his own attitude towards the possibilities of peace, towards the Soviet Union, towards the course of the cold war and towards freedom and peace here at home.

First examine our attitude towards peace itself. Too many of us think it is impossible. Too many think it is unreal. But that is a dangerous, defeatist belief. It leads to the conclusion that war is inevitable, that mankind is doomed, that we are gripped by forces we cannot control. We need not accept that view. Our problems are man-made; therefore, they can be solved by man.

With the help of Murrow's USIA, Kennedy's speech was made available to the world. USIA got thousands of requests for copies; India alone requested 35,000 copies. And what did the Soviet Union do in response? It stopped jamming Voice of America broadcasts, announced a willingness to accept a ban on atmospheric testing and on August 5, 1963 signed the Nuclear Test Ban treaty.

With Sorensen's passing, I can only think that words still matter, are powerful, and can change the world, even if for a moment.

Nancy Snow ([email protected]) received her Ph.D. in international relations from American University's School of International Service. She is Associate Professor in the College of Communications at Cal State Fullerton and Adjunct Professor at USC Annenberg. Her forthcoming book, Truth is the Best Propaganda: Murrow in the Kennedy Years , will be published in 2011, fifty years after Murrow's appointment as Director of the U.S. Information Agency.

From Our Partner

More in politics.

Milestone Documents

President John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address (1961)

Citation: Inaugural Address, Kennedy Draft, 01/17/1961; Papers of John F. Kennedy: President's Office Files, 01/20/1961-11/22/1963; John F. Kennedy Library; National Archives and Records Administration.

View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog

View Transcript

On January 20, 1961, President John F. Kennedy delivered his inaugural address in which he announced that "we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty."

The inaugural ceremony is a defining moment in a president’s career — and no one knew this better than John F. Kennedy as he prepared for his own inauguration on January 20, 1961. He wanted his address to be short and clear, devoid of any partisan rhetoric and focused on foreign policy.

Kennedy began constructing his speech in late November, working from a speech file kept by his secretary and soliciting suggestions from friends and advisors. He wrote his thoughts in his nearly indecipherable longhand on a yellow legal pad.

While his colleagues submitted ideas, the speech was distinctly the work of Kennedy himself. Aides recounted that every sentence was worked, reworked, and reduced. The meticulously crafted piece of oratory dramatically announced a generational change in the White House. It called on the nation to combat "tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself" and urged American citizens to participate in public service.

The climax of the speech and its most memorable phrase – "Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country" – was honed down from a thought about sacrifice that Kennedy had long held in his mind and had expressed in various ways in campaign speeches.

Less than six weeks after his inauguration, on March 1, President Kennedy issued an executive order establishing the Peace Corps as a pilot program within the Department of State. He envisioned the Peace Corps as a pool of trained American volunteers who would go overseas to help foreign countries meet their needs for skilled manpower. Later that year, Congress passed the Peace Corps Act, making the program permanent.

Teach with this document.

Previous Document Next Document

Vice President Johnson, Mr. Speaker, Mr. Chief Justice, President Eisenhower, Vice President Nixon, President Truman, Reverend Clergy, fellow citizens:

We observe today not a victory of party but a celebration of freedom--symbolizing an end as well as a beginning--signifying renewal as well as change. For I have sworn before you and Almighty God the same solemn oath our forbears prescribed nearly a century and three-quarters ago.

The world is very different now. For man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe--the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hand of God.

We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans--born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage--and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world.

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.

This much we pledge--and more.

To those old allies whose cultural and spiritual origins we share, we pledge the loyalty of faithful friends. United there is little we cannot do in a host of cooperative ventures. Divided there is little we can do--for we dare not meet a powerful challenge at odds and split asunder.

To those new states whom we welcome to the ranks of the free, we pledge our word that one form of colonial control shall not have passed away merely to be replaced by a far more iron tyranny. We shall not always expect to find them supporting our view. But we shall always hope to find them strongly supporting their own freedom--and to remember that, in the past, those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside.

To those people in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required--not because the communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.

To our sister republics south of our border, we offer a special pledge--to convert our good words into good deeds--in a new alliance for progress--to assist free men and free governments in casting off the chains of poverty. But this peaceful revolution of hope cannot become the prey of hostile powers. Let all our neighbors know that we shall join with them to oppose aggression or subversion anywhere in the Americas. And let every other power know that this Hemisphere intends to remain the master of its own house.

To that world assembly of sovereign states, the United Nations, our last best hope in an age where the instruments of war have far outpaced the instruments of peace, we renew our pledge of support--to prevent it from becoming merely a forum for invective--to strengthen its shield of the new and the weak--and to enlarge the area in which its writ may run.

Finally, to those nations who would make themselves our adversary, we offer not a pledge but a request: that both sides begin anew the quest for peace, before the dark powers of destruction unleashed by science engulf all humanity in planned or accidental self-destruction.

We dare not tempt them with weakness. For only when our arms are sufficient beyond doubt can we be certain beyond doubt that they will never be employed.

But neither can two great and powerful groups of nations take comfort from our present course--both sides overburdened by the cost of modern weapons, both rightly alarmed by the steady spread of the deadly atom, yet both racing to alter that uncertain balance of terror that stays the hand of mankind's final war.

So let us begin anew--remembering on both sides that civility is not a sign of weakness, and sincerity is always subject to proof. Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate.

Let both sides explore what problems unite us instead of belaboring those problems which divide us.

Let both sides, for the first time, formulate serious and precise proposals for the inspection and control of arms--and bring the absolute power to destroy other nations under the absolute control of all nations.

Let both sides seek to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors. Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths and encourage the arts and commerce.

Let both sides unite to heed in all corners of the earth the command of Isaiah--to "undo the heavy burdens . . . (and) let the oppressed go free."

And if a beachhead of cooperation may push back the jungle of suspicion, let both sides join in creating a new endeavor, not a new balance of power, but a new world of law, where the strong are just and the weak secure and the peace preserved.

All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin.

In your hands, my fellow citizens, more than mine, will rest the final success or failure of our course. Since this country was founded, each generation of Americans has been summoned to give testimony to its national loyalty. The graves of young Americans who answered the call to service surround the globe.

Now the trumpet summons us again--not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need--not as a call to battle, though embattled we are-- but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out, "rejoicing in hope, patient in tribulation"--a struggle against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease and war itself.

Can we forge against these enemies a grand and global alliance, North and South, East and West, that can assure a more fruitful life for all mankind? Will you join in that historic effort?

In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility--I welcome it. I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation. The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it--and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.

And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country.

My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you. With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God's work must truly be our own.

Dick Goodwin, the Kennedy-LBJ Speechwriter Who Changed the ’60s—and the Country

For Jack, Bobby, and Lyndon, he wrote some of the most eloquent words they ever spoke and was one of the most important figures of his year.

Jeff Greenfield

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast

In the summer of 1954, Richard Goodwin walked into the Harvard Law School library, ready to begin his first day as a member of the Harvard Law Review; a position all but guaranteeing a path to a life of privilege and prestige. For the son of lower middle-class Jews, it was the reward for years of intense study, with summers working as a fry cook at Revere Beach, supplementing a full scholarship to Harvard Law.

But as he prepared for the dreary work of checking footnotes from a law review article, something snapped. It was as if, he wrote years later, that he was in a prison. So he turned on his heel, drove back to Brookline, waived his student deferment, and joined the army. After his service, he went back to Harvard Law, where he finished first in his class, was president of the Law Review, and won a clerkship from Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter.

Fourteen years later, 2 miles east of Harvard Law, Goodwin sat in his office at MIT, where he held a cushy faculty position. It was early 1968, and Goodwin was increasingly despairing of a Vietnam War that had lost all purpose, and a nation seized by racial and generational tumult. His close friend Robert Kennedy had refused to challenge President Johnson for the Democratic nomination, but Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy was embarked on that quixotic effort in New Hampshire.

So Goodwin quit his post, jumped into his car, and at midnight, arrived at the Perkins Motel in Manchester, New Hampshire, where he rousted McCarthy’s press secretary, Sy Hersh, walked him to his car, pointed to his typewriter and said, “You, me and this typewriter, Sy; together we’re going to overthrow the president of the United States.”

A month later, McCarthy won 42 percent of the primary vote—a stunning, unexpected achievement; four days later, Robert Kennedy entered the race, and two weeks after that, Johnson announced he would not run for another term.

These two anecdotes say much about who Dick Goodwin was: the blend of determination, ability, and, yes, a touch of arrogance; but more than that— they point to what made Goodwin so compelling a figure. The last of the New Frontiersmen—when he died Sunday at 85, he was the last surviving member of President John Kennedy’s 1960 campaign team—he embodied one of Kennedy’s favorite observations, from fellow New Englander Emerson: that “a man must share the actions and passions of his time on peril of being judged not to have lived.” Goodwin didn’t just “share” the actions and passions of his time—he threw himself into them, and in so doing, put his mark on those times.

Goodwin is best known as a speechwriter, who wrote perhaps the single greatest presidential oration of the post-FDR era: Lyndon Johnson’s 1965 speech on the Voting Rights Act (video here ), which proclaimed that “it’s not just Negroes, but really it’s all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

He was also a principal author, along with Adam Walinsky, of Robert Kennedy’s 1966 “Day of Affirmation” speech in South Africa (video here ), which declared: “Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

But his influence extended beyond rhetoric; he was, in a way, an embodiment of at least one part of the ’60s; an era that began with the rise of a younger generation to power, armed with the conviction—which a times shaded into hubris—that it could move mountains, and that ended with an assassin’s bullet in a kitchen pantry in a Los Angeles hotel.

In his late twenties, Goodwin was a lawyer for a House Committee that investigated the enormously popular TV quiz shows of the late 1950s. It was Goodwin, the scholarship kid from a Jewish neighborhood in Boston, who confronted and revealed the fraud behind the performance of Charles Van Doren, the epitome of WASP elitism. (The movie Quiz Show tells the story.)

It was Goodwin who, at age 29, became Ted Sorensen’s deputy speechwriter in JFK’s 1960 campaign. It was Goodwin who, not yet 30, became the deputy assistant secretary of state for Inter-American Affairs and caused a political firestorm by meeting secretly with Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara in Uruguay. (The meeting led to no diplomatic breakthrough, but Guevara did gift Goodwin with a box of fine Havanas, which appealed mightily to the cigar-loving Goodwin.)

By his mid-thirties, he was a close friend of Robert Kennedy, accompanying him on tumultuous trip through South America, where they were harassed by Communist students and swam in piranha-infested waters. It was that friendship that ultimately drew him to leave Gene McCarthy’s campaign and join RFK’s effort, where he worked with director John Frankenheimer on the television ads that helped win primaries in Indiana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and California, where Sirhan Sirhan was waiting in that hotel kitchen.

That, in shorthand, describes what Dick Goodwin did in that decade. But it doesn’t really capture who he was. For one thing, Goodwin shared with Robert Kennedy a mordant sense of humor; a puckish delight in upending the pieties of politics. In his memoir Remembering America , Goodwin describes a memo from a White House aide warning him that a file cabinet of his had been found open at 12:45 a.m. In response, Goodwin sent a memo to the aide, explaining that the aide had just blown up “the most skillful espionage operation in the history of the American government.” The cabinet, he wrote, was filled with deliberately false information.

“Then I usually invite someone from the Russian embassy over for a nightcap. At the appropriate moment (around 12:45 am) I say I have to go over to the mansion and leave”—thus leaving the Soviet agent in possession of totally misleading data.