- Open access

- Published: 05 September 2019

Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and improving nutrition in children: a cluster randomised controlled trial

- Scott Duncan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8402-2930 1 ,

- Tom Stewart 1 ,

- Julia McPhee 1 ,

- Robert Borotkanics 1 ,

- Kate Prendergast 1 ,

- Caryn Zinn 1 ,

- Kim Meredith-Jones 2 ,

- Rachael Taylor 2 ,

- Claire McLachlan 3 &

- Grant Schofield 1

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity volume 16 , Article number: 80 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

5746 Accesses

20 Citations

24 Altmetric

Metrics details

Most physical activity interventions in children focus on the school setting; however, children typically engage in more sedentary activities and spend more time eating when at home. The primary aim of this cluster randomised controlled trial was to investigate the effects of a compulsory, health-related homework programme on physical activity, dietary patterns, and body size in primary school-aged children.

A total of 675 children aged 7–10 years from 16 New Zealand primary schools participated in the Healthy Homework study. Schools were randomised into intervention and control groups (1:1 allocation). Intervention schools implemented an 8-week applied homework and in-class teaching module designed to increase physical activity and improve dietary patterns. Physical activity was the primary outcome measure, and was assessed using two sealed pedometers that monitored school- and home-based activity separately. Secondary outcome measures included screen-based sedentary time and selected dietary patterns assessed via parental proxy questionnaire. In addition, height, weight, and waist circumference were measured to obtain body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR). All measurements were taken at baseline (T 0 ), immediately post-intervention (T 1 ), and 6-months post-intervention (T 2 ). Changes in outcome measures over time were estimated using generalised linear mixed models (GLMMs) that adjusted for fixed (group, age, sex, group x time) and random (subjects nested within schools) effects. Intervention effects were also quantified using GLMMs adjusted for baseline values.

Significant intervention effects were observed for weekday physical activity at home (T 1 [ P < 0.001] and T 2 [ P = 0.019]), weekend physical activity (T 1 [P < 0.001] and T 2 [P < 0.001]), BMI (T 2 only [ P = 0.020]) and fruit consumption (T 1 only [ P = 0.036]). Additional analyses revealed that the greatest improvements in physical activity occurred in children from the most socioeconomically deprived schools. No consistent effects on sedentary time, WHtR, or other dietary patterns were observed.

Conclusions

A compulsory health-related homework programme resulted in substantial and consistent increases in children’s physical activity – particularly outside of school and on weekends – with limited effects on body size and fruit consumption. Overall, our findings support the integration of compulsory home-focused strategies for improving health behaviours into primary education curricula.

Trial registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, ACTRN12618000590268 . Registered 17 April 2018.

Physical activity and healthy nutrition practices are essential for many aspects of child health and development [ 1 ], including the prevention of chronic health conditions in adolescence and adulthood [ 2 , 3 ]. However, evidence indicates that many children do not meet international physical activity and dietary guidelines [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ], contributing to a rise in obesity and related comorbidities in later life [ 8 ]. The development, implementation, and evaluation of effective and sustainable initiatives that equip children to lead healthy and active lives has become a key public health priority in many countries [ 1 ]. Despite parents having a significant influence on children’s activity and eating patterns, exclusively home-based interventions are logistically impractical. The school setting may provide a unique opportunity for intervention delivery: intervention material can be wide-reaching, especially if made compulsory as part of the curriculum or integrated into school policy [ 9 , 10 , 11 ].

Several systematic reviews indicate that delivering interventions within school can improve several physical activity and diet behaviours in children [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]; however, these effects are often modest at best. Quality of evidence from past randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was criticised in a 2013 Cochrane Review and judged at moderate risk of bias—a reliance on self-reported outcomes, absence of longer term follow-up, lack of blinding, and failing to account for clustering during analyses being common problems [ 12 ]. Additional reviews have concluded that physical activity interventions have had only small to negligible measured effects on total and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, whether assessed immediately post intervention or at six-month follow-up [ 15 , 16 ]. Nonetheless, evidence indicates that school-based physical activity and dietary interventions can be successful in improving indicators related to obesity in children [ 17 ].

To date, the majority of school-based physical activity/nutrition interventions have focused solely on the school environment [ 12 , 18 ], despite reviews indicating that multicomponent interventions involving the family or community in addition to the school are likely to be most effective [ 17 , 19 , 20 ]. Family support and parental restrictions can influence out-of-school physical activity [ 21 ], and the majority of food that children consume originates from the home [ 22 , 23 ]. Therefore, it is unlikely that long-term behaviour change is possible when the influences of the home environment are not addressed. The concept of curriculum-based physical activity or nutrition ‘homework’ is relatively under-utilised. Active for Life Year 5 (AFLY5) aimed to improve in-school and out-of-school physical activity and diet behaviours through professional learning and development for teachers coupled with in-class lessons and homework plans [ 24 ]. While positive effects on screen time and high energy drinks and snacks were observed, there were no significant effects on physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, or body size [ 25 , 26 ].

This paper presents the main findings from the Healthy Homework programme, an eight-week (approximately one school term) intervention designed to improve the physical activity and dietary behaviours of primary-aged children through a compulsory health-related homework schedule, supplemented with curriculum resources for teachers. This approach differs from many previous school-based interventions because the homework component was designed to maximise family engagement, theoretically improving the likelihood of success. Healthy Homework was developed in 2008 with oversight from New Zealand education and health professionals, and underwent extensive piloting in two primary schools [ 27 ]. Despite a small sample size, significant benefits were observed in physical activity and some dietary behaviours. Perhaps most importantly, focus groups revealed that the programme was highly valued by the children, their parents, and participating teachers [ 27 ]. We found that the level of family engagement exceeded expectations, and that the usability and utility of Healthy Homework for teachers was high [ 27 ].

Despite these encouraging results, several limitations were noted: the sample size was small limiting generalisability, the programme required updating to align with the New Zealand Curriculum, body size was not assessed, and the cluster unit was classroom (raising the possibility of between-group contamination). Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the effects of an updated Healthy Homework programme on physical activity, nutrition, and body size in a large sample of New Zealand children randomised at the school level.

Participants

Due to the nature of the intervention, individual participants were accessed via primary (elementary) schools, which acted as the cluster unit in all subsequent analyses. Eligibility criteria for the schools were as follows: enrolment of over 100 students, location within Auckland or Dunedin cities, and a contributing, full primary, or composite structure that included at least one class each of students in school years 3–5. A total of 16 primary schools from Auckland ( n = 10) and Dunedin ( n = 6) were randomly selected to participate in the study from a sampling frame of all eligible schools. Socioeconomic decile ratings of participating schools (determined by the NZ Ministry of Education) ranged from 1 to 10 (where 1 indicates ‘low’ and 10 indicates ‘high’; median [IQR] = 8 [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]). After stratification by decile group (1–7 and 8–10), each school was randomly assigned into the intervention group ( n = 8) or the waitlisted control group (n = 8) by the lead researcher using a random number generator (concealed from participants; 1:1 allocation ratio). This stratification was implemented as only one Decile 1 school was recruited. Schools assigned to the control group were offered the intervention (including all resources) following the final assessment period. One Year 3, Year 4, and Year 5 class from each school were then selected to participate; simple random sampling was used in instances where there were two or more classes per year. Year 6 classes were excluded to permit final follow-up measurements. Enrolment occurred between 01/07/11 and 24/07/12, with measurements staggered across every calendar month (excluding January and December) and school term (1–4); the last follow-up measure occurred at 07/04/13. At the intervention schools, all children in the selected classes received the Healthy Homework programme as part of the schools’ curricula; however, parental consent was required before children were included in the intervention evaluation. All children in each participating class were invited to take part in the evaluation (i.e., no formal inclusion or exclusion criteria aside from consent/assent), which took place in school grounds. Parent information and consent forms were sent home with the children for completion and return. Ethical approval was obtained from the Auckland University of Technology (10/159) and University of Otago (11/084) Ethics Committees.

Based on reference data from the HH feasibility phase [ 27 ], we calculated that a target sample size of 800 children would enable us to detect the following differences in our outcome measures (α = 0.05, 1-β = 0.80): 1000 pedometer steps/day, 30 min.day − 1 of TV/computer time, 0.5 daily servings of fruit and vegetables, 0.5 daily servings of takeaway food, and a BMI z-score of 0.2. These calculations allow for school clustering effects (cluster size = 16; ICC = 0.04), correlation between repeated measures (0.4 for all behavioural variables and 0.8 for BMI z-score), and 25% dropout at each follow-up point.

Intervention design

The design and theoretical basis of the Healthy Homework programme is described in detail elsewhere [ 27 ] and only a brief summary is outlined here. Healthy Homework was an eight-week curriculum-based homework schedule, complemented by an in-class teaching resource, designed to promote physical activity and healthy eating in children (curriculum resources may be provided upon request). The programme was developed under the guidance of an advisory committee comprising experienced health and education professionals (including classroom teachers) with regular input from children and parents. Healthy Homework was based on several established behaviour change theories (including the theory of reasoned action, the theory of planned behaviour, and social-cognitive theory [ 28 ]), and was designed to support the achievement objectives associated with the Health and Physical Education strand of the New Zealand Curriculum [ 29 ]. The research team provided professional learning for the teachers of the three intervention classes at each intervention school, and to one lead teacher in each of the control schools (who were permitted to implement the programme at the conclusion of the final follow-up point). The professional learning protocol was standardised across all schools, and necessitated one half-day release per teacher. Approximately 90 min was spent providing information about the benefits of physical activity and a healthy diet for children’s overall health and development, and the results of previous strategies to integrate these topics into the primary school curriculum. An additional 90 min was spent introducing the teachers to the in-class and homework modules, discussing examples of how to complete tasks, and fielding questions about the programme delivery and evaluation.

At the start of the intervention, all children in participating classes received a homework booklet organised into weekly topics that each contained one physical activity and one nutrition component (e.g., walking and fruit/vegetables, screen time and breakfast, fitness and cooking). Three practical homework options were provided for each topic, and the children were directed by their teacher to complete at least one physical activity and one nutrition task per topic each week (e.g., organising family walks, walking to and from school, limiting screen time, testing the fitness of the family, eating 5+ fruit and vegetables each day, comparing food labels at the supermarket, helping with dinner, preparing a healthy lunch box). Blue or purple rubber wristbands were provided each week for children who completed their homework obligations, with a black colour reserved for those who completed all six tasks on a given week. The intention of the wristbands were to encourage the children to complete more than the minimum number of required tasks. The Healthy Homework classroom curriculum resource was designed to provide the teachers with sufficient educational content and in-class exercises for three 1.5-h sessions delivered on different days throughout each week (including one session reviewing the previous week’s homework). Furthermore, an online portal was developed and monitored to allow teachers to access resources and record student compliance, and to enable children to share homework-related updates with other participants (including those in other schools). Student and teacher modules can be downloaded as Additional files 2 and 3 .

Baseline measurements were taken prior to intervention delivery (T 0 ), and repeated immediately post-intervention (T 1 ) and six-months post-intervention (T 2 ), between August 2011 and April 2013. The team of research assistants responsible for data collection were not blinded to group allocation. Each research assistant was provided with an appropriate level of anthropometric training by experienced researchers prior to data collection.

Physical activity

Weekday physical activity at school, weekday physical activity at home, and weekend physical activity – treated as the primary outcome measures – were assessed using sealed NL-1000 pedometers (New Lifestyles Inc., Lee’s Summit, MO) over five consecutive days (three weekdays, two weekend days). These pedometers have a multiday memory function that automatically stores step counts by day of week for up to 7 days. Our previous research has established the validity of these pedometers for measuring steps in children, with mean percent bias less than 5% for typical walking speeds [ 30 ]. Two pedometers were assigned to each child: one clearly labelled ‘School’ and the other ‘Home’. The ‘School’ pedometer was worn during school hours, while the ‘Home’ pedometer was left inside a collection tray in the classroom. At the conclusion of the school day (approx. 3 pm), each child placed their ‘School’ pedometer in the tray and attached their ‘Home’ pedometer. At the beginning of the next weekday (approximately 9 am), the teacher reminded the children to switch over their pedometers again. Thus, before school and after school activities that were outside of the classroom were captured on the ‘Home’ pedometer. This approach was taken as it removed the need for teachers to coordinate a lengthy collection and handout process, and allowed the differentiation of in-school and out-of-school physical activity, while using a cost-effective but objective measurement device.

Dietary patterns

Key dietary patterns were estimated as secondary outcome measures using items extracted from the Children’s Dietary Questionnaire (CDQ), a parental proxy report that has been validated in children aged 4–16 years [ 31 ]. The CDQ focuses on patterns of food intake over the previous 24 h and/or 7 days rather than actual amounts and types of foods consumed. The questionnaire contained 33 items, 30 of which utilised categorical response options, and three of which utilised open-ended response options. A total of 20 questions referred to dietary patterns over the previous seven-days, 11 questions referred to dietary patterns over the previous 24-h, and two referred to specific meal questions (breakfast and lunch). The four dietary items selected for analyses in this study were: (1) daily fruit consumption, (2) daily vegetable consumption, (3) weekly fast food consumption, and (4) weekly soft drink consumption. These items were selected given their alignment with the New Zealand Food and Nutrition Guidelines, and the high prevalence of soft drink consumption in New Zealand youth [ 32 ]. A copy of the questionnaire may be provided upon request.

Television and computer usage

Two questions pertaining to the frequency and duration of television, computer and gaming console use were also amended to the questionnaire as additional secondary outcome measures. These questions asked parents to recall the amount of time each day (Monday to Sunday) their child spent (1) watching TV, DVDs, or videos, or (2) on the computer or games console (not including school-related work) in the previous week. The total time provided for Monday to Friday was averaged to provide a weekday TV/computer estimate, whereas Saturday and Sunday totals were averaged to provide a weekend estimate.

Standing height was measured to the nearest millimetre with a portable stadiometer (SECA 213, Hamberg, Germany) and weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg on a digital scale (SECA 813, Hamberg, Germany). Waist circumference was measured midway between the iliac crest (highest point of the pelvis at the side) and the lowest rib margin. Participants were asked to remove their shoes and any bulky external clothing (i.e. jackets, coats) prior to assessment. For all anthropometric measures, estimates were taken three times, with the average value used in subsequent analysis. Body mass index (BMI; secondary outcome measure) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by squared height (m 2 ), and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR; secondary outcome measure) was calculated as waist circumference (cm) divided by height (cm).

Statistical analysis

In the first instance, baseline characteristics of the sample were calculated and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), or median and interquartile range (IQR) in cases where the data were not normally distributed. Intention-to-treat analyses were used to test the efficacy of the intervention, regardless of adherence to homework tasks. To simplify analysis and interpretation of the dietary data, categorical CDQ subscales were converted into binary variables using thresholds that approximately balanced the number of responses in each category.

Changes in outcome variables were compared between intervention and control groups using generalised linear mixed models (GLMMs) that adjusted for fixed and random (subjects nested in schools) effects. This approach was taken to account for the intra-school correlations and intra-person correlations between the repeated measures. Outcomes were controlled for baseline measures and age. A gamma probability distribution and an log link function was applied for most outcome variables, the exception being weekday TV, which were evaluated using a Gaussian distribution and identity link function. Models predicted outcomes at completion of the intervention (T 1 ). Additional models predicted outcomes at 6 months post intervention (T 2 ). Marginal effects were evaluated on select variables. Descriptive analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics v23 (IBM Cooperation, USA) and GLMM’s were carried out using Stata V14 (Stata Corporation, USA).

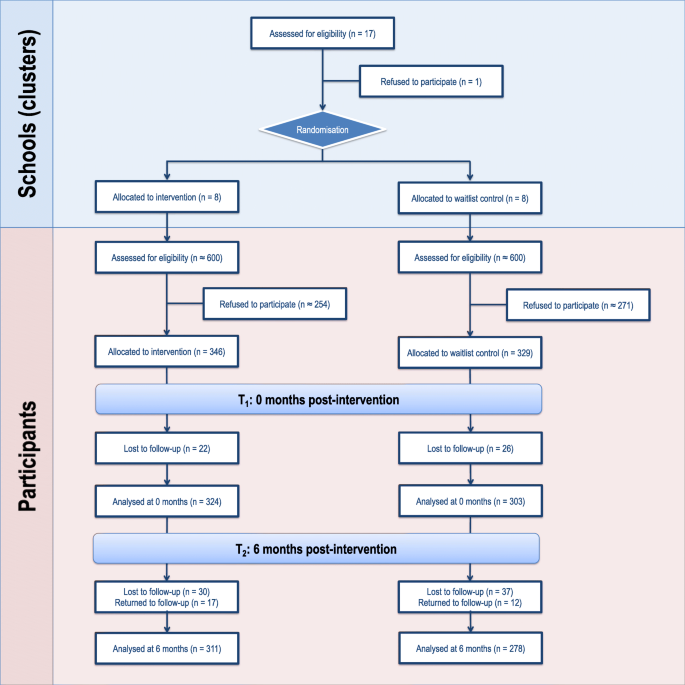

The Healthy Homework intervention was conducted between August 2011 and August 2012. Figure 1 depicts participant allocation and retention across each phase of the study in the form of a CONSORT flow diagram. A total of 675 children (intervention = 171 boys and 175 girls; control = 155 boys and 174 girls) aged 7–10 years provided written parental consent and assent to participate in the evaluation (consent rate = 56.3%). Cluster size (i.e., the number of children from each school) ranged from 14 to 53 (median [IQR] = 47.5 [36.5, 50]). Absent days, changing school, and withdrawals resulted in 46 children that did not participate in the first follow up (T 1 ), and 67 children that did not participate in the second follow-up 6-months post intervention (T 2 ). However, 29 of the 46 children absent from T 1 returned for T 2 . The completed CONSORT checklist can be accessed as an Additional file 1 .

Participant allocation and retention

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the study sample. There were no meaningful differences in age, gender distribution, or physical activity between the intervention and control groups at baseline. However, the intervention group contained notably more participants from schools in lower SES areas, had a higher proportion of children from Maori and Pacific backgrounds, as well as slightly higher BMI, WHtR, and daily servings of vegetables. Overall, the sample averaged 5090 ± 2200 steps/day (mean ± SD) at home on weekdays, 5410 ± 2200 steps/day at school, and 7440 ± 4100 steps/day on weekends, with boys more active than girls. No systematic pattern emerged with regard to the missingness of the data. For outcomes reported by proxy questionnaire, the response rate at T3 averaged between 54 and 60%. We removed weekend activity from our secondary analyses because the response rates were below 50%. All other outcomes evaluated – BMI, weekday activity – had a response rate in excess of 70%.

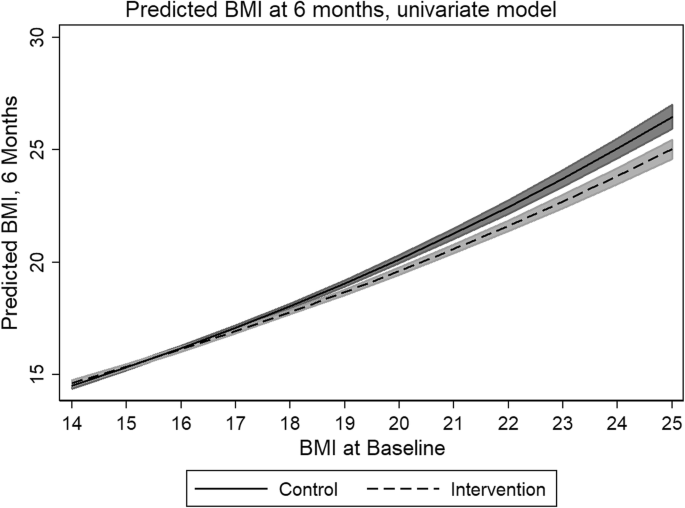

Table 2 presents the results for the GLMMs. In general, the intervention group did not experience a statistically significant reduction in BMI immediately after the completion of the intervention (p: 0.755), but did demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in BMI at 6 months post intervention (p: 0.020). The predicted marginal mean of BMI in the control group at 6 months was 17.451; the intervention group, 17.274. However, marginal analyses revealed that those subjects that are likely to benefit most are students that have a baseline BMI of 17 or higher (Fig. 2 ), with a statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups emerging at this point (β: − 0.267, z: − 2.19, p: 0.028, CI: − 0.017 − 0.001).

Predicted difference in BMI between study groups (univariate model)

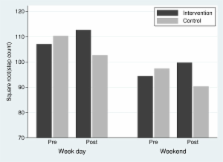

Overall activity increased at T 1 and T 2 time points. This increase was statistically significant for weekday home and weekend activity (Table 2 ). School decile had exhibited a statistically significant impact on weekday home activity at T 1 , with the greatest improvements in weekday home activity occurring in the most socioeconomically deprived schools (Table 3 ). This increase persisted into T 2 , albeit attenuating to just outside of statistical significance (Table 3 ). Weekend television watching increased relative to baseline in those subjects from the most socioeconomically deprived schools at T 2 , and this difference was statistically significant (Table 3 ).

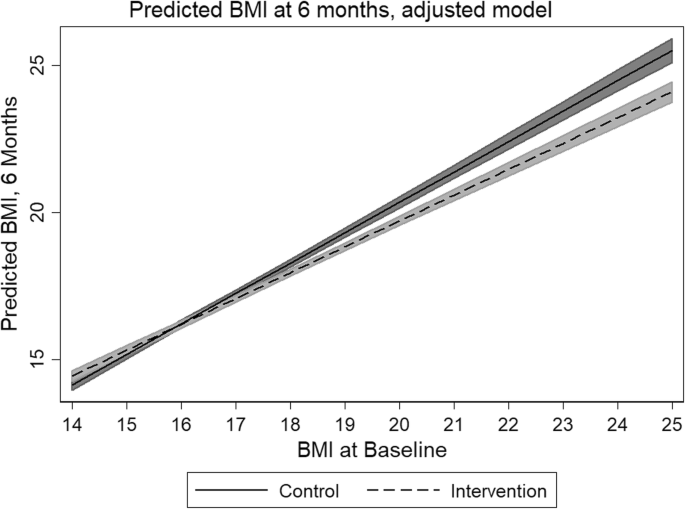

The adjusted model evaluating covariate effect on BMI at T 2 revealed that weekday home activity was the most significant covariate (Table 4 and Fig. 3 ). For each increase in 1000 steps, an almost 0.6 point decrease in BMI was realized. This model was adjusted for school decile. These decreases were most pronounced in the socioeconomically most deprived schools, where subject BMI decreased 0.476 points per 1000 steps, when controlling for other covariates. Proxy-reported vegetable consumption at T 2 was the second most important predictor of BMI reduction at T 2 , where each meal of vegetable consumed resulted in a 0.036 point decrease in BMI. It should be noted that weekend steps could not be evaluated with respect to school decile or BMI at T 2 , because only 39 and 47% matching observations were available (respectively).

Predicted difference in BMI between study groups (adjusted model)

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of the Healthy Homework programme for improving physical activity, dietary patterns, and body size in primary-aged children. Despite being a school-based intervention, a key strength of this study was the design of a homework syllabus that maximised family participation and engagement, thereby targeting out-of-school behaviours. Our results demonstrate significant and sustained increases in physical activity 6-months post-intervention. Of particular note were the large effects on out-of-school physical activity, approximate to hypothetical increases of 15.6 and 29.7% (i.e., intervention effects compared to baseline values) each weekday and weekend day, respectively. This degree of improvement, should it persist over the long term, would likely have a meaningful impact on children’s health and wellbeing: reviews have identified favourable effects on a wide range of physical, psychosocial, and cognitive outcomes of even modest increases in physical activity [ 33 , 34 ]. Furthermore, the relatively larger effects observed in children from the most socioeconomically-deprived schools suggest that this intervention approach may be an effective way of engaging at-risk populations.

Significant intervention effects on BMI and fruit consumption were also observed, although the effects were smaller and inconsistent across time points. Intervention effects on BMI, in particular, were limited. No difference was observed at the end of the intervention, and although a statistically significant difference was observed between groups at T2, such a difference would not be deemed clinically relevant. It is possible that the follow-up time was insufficient to allow any improvements in physical activity to influence body size. Nonetheless, our findings provide some support for the development and implementation of resources that enhance family involvement in health-related curriculum areas.

Despite the positive effects for physical activity, we did not observe any meaningful changes in screen time or dietary patterns. The lack of effect on screen time may be explained by the relatively minor emphasis placed on this topic (only one session); however, half the module featured advice and activities relating to nutrition and diet. We did note via anecdotal feedback that the children appeared to prefer the physical activity topics over the nutrition topics, and perhaps this played a role in the lack of consistent dietary effects. It is possible that physical activity is a more malleable and less complex behaviour than diet in children [ 35 ], or that our questionnaire-based assessment of dietary intake was not sensitive enough to quantify meaningful changes in this sample. In any case, this study suggests that nutrition initiatives in primary schools may not achieve the same level of benefits as similar physical activity programmes.

One of the distinctive aspects of the intervention was its compulsory nature, with a number of key health messages grounded in the national school curriculum [ 29 ]. Although there is promising evidence that purely family-based intervention approaches can improve children’s physical activity and diet [ 36 , 37 ], teaching nutrition and physical activity within the primary-school curriculum provides a cost-effective method of reaching large numbers of children without the requirement of children or families to ‘opt-in’. Given the significant effects on physical activity, body size, and fruit consumption in this study, it appears that curriculum-based, health-related programmes in primary schools can have an impact on the behaviours of children, at least over the short-medium term.

The significant improvements observed in the present study are in contrast to the lack of effects reported by the AFLY5 study [ 25 , 26 ], which featured an intervention design very similar to the present study (both studies targeted similar lifestyle behaviours via compulsory in-class lesson plans and homework tasks). The AFLY5 authors offered several explanations as to why AFLY5 may not have had a significant impact, such as the delay in time between intervention development and implementation, and the potential need for more intensive behavioural change and/or upstream societal or environmental approaches. None of these possibilities, however, explain the difference in outcomes between AFLY5 and Healthy Homework. One clear distinction was that Healthy Homework included a minimum of 14 and a maximum of 42 homework tasks over the 8-week period, whereas AFLY5 provided 10 parent-child interaction activities. Furthermore, AFLY5 researchers reported difficulties motivating some teachers, who felt the need to prioritise literacy and numeracy above health-promoting lessons [ 26 ]. Another similar intervention – the Eat Well and Keep Moving Program – was conducted over a two-year period, and integrated materials designed to increase physical activity, improve dietary patterns, and reduce television viewing within the grade 4 and 5 school curriculum (including homework components) [ 11 ]. The evaluation of the intervention revealed significant improvements in dietary patterns and a marginal decrease in television viewing via 24-h recall questionnaires. The present findings add to this body of evidence by demonstrating the potential for positive physical activity outcomes when using objective measurement techniques; however, the effects of embedding health-related lessons and homework within school curricula appear to be variable, and may depend on the specific population and/or context.

There were several limitations present in this study that should be acknowledged. While we were able to collect data about the overall amount of physical activity, we were not able to clarify with any detail the within-day patterns and intensity of activity. Pedometers were primarily chosen for financial reasons; however, the use of omnidirectional accelerometers would have enabled another level of analysis. Related to this point, we were not able to determine the effects on sedentary behaviour, which cannot be effectively isolated via pedometry. As mentioned earlier, a more comprehensive dietary assessment may have revealed some effect on nutrition, although the substantial response burden may have resulted in participant bias. The four items from the CDQ, selected due to their alignment with NZ policy, may not exhibit the same levels of validity and reliability as the full scales. In addition, generalisability of conclusions based on the data in this study is limited by the selection of participants from only two regions of New Zealand; the study design clearly requires replication in larger and more diverse populations. Socioeconomic decile ratings were not evenly matched by intervention and control group; there was one Decile 1 intervention school, whereas the lowest decile rating in the control group was Decile 3. Another limitation was that the research assistants collecting data were not blinded to the school allocation, which may have introduced accidental or deliberate bias during anthropometric assessment. Finally, intervention fidelity, which would have enabled per protocol analysis, was not assessed.

In summary, we have shown that a curriculum-based health programme can result in consistent improvements to physical activity levels in primary school-aged children, with significant but limited effects on body size and fruit consumption. The next step is to see if such programmes are sustainable within the school environment over a long term, and without input from researchers. The effects of such programmes on academic and neurocognitive outcomes development is also of interest and should be explored in future.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to a confidentiality agreement with participating schools. Enquiries should be addressed to the principal author.

Abbreviations

Active for life year 5

Body mass index

Children’s dietary questionnaire

Generalised linear mixed model

Randomised controlled trial

Baseline, first follow-up, and second follow-up time points

Waist-to-height ratio

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on child health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Google Scholar

Lipsky LM, Haynie DL, Liu D, Chaurasia A, Gee B, Li K, et al. Trajectories of eating behaviors in a nationally representative cohort of U.S. adolescents during the transition to young adulthood. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:138.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Telama R. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a review. Obes Facts. 2009;2:187–95.

Cooper AR, Goodman A, Page AS, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, van Sluijs EM, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in youth: the International children’s accelerometry database (ICAD). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:113.

Vereecken C, Pedersen TP, Ojala K, Krølner R, Dzielska A, Ahluwalia N, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption trends among adolescents from 2002 to 2010 in 33 countries. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:16–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lynch C, Kristjansdottir AG, Te Velde SJ, Lien N, Roos E, Thorsdottir I, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption in a sample of 11-year-old children in ten European countries–the PRO GREENS cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:2436–44.

Tremblay MS, Barnes JD, Gonzalez SA, Katzmarzyk PT, Onywera VO, Reilly JJ, et al. Global matrix 2.0: report card grades on the physical activity of children and youth comparing 38 countries. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:S343–S66.

Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes. 2011;35:891–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Erwin H, Beighle A, Carson RL, Castelli DM. Comprehensive school-based physical activity promotion: a review. Quest. 2013;65:412–28.

Article Google Scholar

Williams AJ, Henley WE, Williams CA, Hurst AJ, Logan S, Wyatt KM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between childhood overweight and obesity and primary school diet and physical activity policies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:101.

Gortmaker SL, Cheung LW, Peterson KE, Chomitz G, Cradle JH, Dart H, et al. Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children: eat well and keep moving. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:975–83.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dobbins M, Husson H, DeCorby K, LaRocca RL. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2):CD007651. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007651.pub2 .

Delgado-Noguera M, Tort S, Martínez-Zapata MJ, Bonfill X. Primary school interventions to promote fruit and vegetable consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2011;53:3–9.

Evans CE, Christian MS, Cleghorn CL, Greenwood DC, Cade JE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to improve daily fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 5 to 12 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:889–901.

Metcalf B, Henley W, Wilkin T. Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54); 2012.

Sims J, Scarborough P, Foster C. The effectiveness of interventions on sustained childhood physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132935.

Wang Y, Cai L, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Weston C, Fawole O, et al. What childhood obesity prevention programmes work? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:547–65.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kriemler S, Meyer U, Martin E, van Sluijs EM, Andersen LB, Martin BW. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: a review of reviews and systematic update. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:923–30.

Van Sluijs EM, McMinn AM, Griffin SJ. Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: systematic review of controlled trials. BMJ. 2007;335:703.

Brown HE, Atkin AJ, Panter J, Wong G, Chinapaw MJ, van Sluijs EM. Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: a systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obes Rev. 2016;17:345–60.

McMinn AM, Griffin SJ, Jones AP, van Sluijs EM. Family and home influences on children’s after-school and weekend physical activity. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(5):805–1.

Rockell JE, Parnell WR, Wilson NC, Skidmore PM, Regan A. Nutrients and foods consumed by New Zealand children on schooldays and non-schooldays. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:203–8.

Regan A, Parnell W, Gray A, Wilson N. New Zealand children's dietary intakes during school hours. Nutr Dietetics. 2008;65:205–10.

Lawlor DA, Jago R, Noble SM, Chittleborough CR, Campbell R, Mytton J, et al. The active for life year 5 (AFLY5) school based cluster randomised controlled trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:181.

Kipping RR, Howe LD, Jago R, Campbell R, Wells S, Chittleborough CR, et al. Effect of intervention aimed at increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary behaviour, and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in children: active for life year 5 (AFLY5) school based cluster randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2014;348:g3256.

Anderson EL, Howe LD, Kipping RR, Campbell R, Jago R, Noble SM, et al. Long-term effects of the active for life year 5 (AFLY5) school-based cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010957.

Duncan S, McPhee JC, Schluter PJ, Zinn C, Smith R, Schofield G. Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children: the healthy homework pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:127.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27:379–87.

Ministry of Education. The New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Ministry of Education; 2007.

Duncan S, Schofield G, Duncan EK, Hinckson EA. Effects of age, walking speed, and body composition on pedometer accuracy in children. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007;78:420–8.

Magarey A, Golley R, Spurrier N, Goodwin E, Ong F. Reliability and validity of the Children's dietary questionnaire; a new tool to measure children's dietary patterns. Int J Ped Obes. 2009;4:257–65.

Sundborn G, Utter J, Teevale T, Metcalf P, Jackson R. Carbonated beverages consumption among New Zealand youth and associations with BMI and waist circumference. Pac Health Dialog. 2014;20(1):81–6.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40.

Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Borghese MM, Carson V, Chaput JP, Janssen I, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:S197–239.

World Health Organization. Interventions on diet and physical activity: what works. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Viitasalo A, Eloranta AM, Lintu N, Vaisto J, Venalainen T, Kiiskinen S, et al. The effects of a 2-year individualized and family-based lifestyle intervention on physical activity, sedentary behavior and diet in children. Prev Med. 2016;87:81–8.

Taylor RW, Cox A, Knight L, Brown DA, Meredith-Jones K, Haszard JJ, et al. A tailored family-based obesity intervention: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136:281–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participating schools, children, and parents for contributing their time and effort to this study.

Funding for the Healthy Homework study was provided by a Health Research Council of New Zealand Project Grant (10–207).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Sport and Recreation, Auckland University of Technology, Private Bag 92006, Auckland, New Zealand

Scott Duncan, Tom Stewart, Julia McPhee, Robert Borotkanics, Kate Prendergast, Caryn Zinn & Grant Schofield

Edgar Diabetes and Obesity Research Centre, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin, New Zealand

Kim Meredith-Jones & Rachael Taylor

School of Education, Federation University Australia, PO Box 663, Ballarat, VIC 3353, Victoria, Australia

Claire McLachlan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SD and GS conceptualised the study, and SD was the principal investigator for the Health Research Council Project Grant. SD, CZ, RT designed the evaluation protocol, and SD, JM, KP, CZ, and CM contributed to the development of intervention resources. JM, KP, and KM recruited all participants and collected the data. KP and KM collated and processed the data, and RB and SD analysed the data. SD and TS drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback throughout the writing process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Scott Duncan .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Written informed parental consent and personal assent was obtained from each participant for the collection and use of the data in future publication. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Auckland University of Technology (10/159) and University of Otago (11/084) Ethics Committees.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

CONSORT 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a randomised trial. (DOC 218 kb)

Additional file 2:

Teachers Manual. (PDF 11980 kb)

Additional file 3:

Students Manual. (PDF 10554 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Duncan, S., Stewart, T., McPhee, J. et al. Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and improving nutrition in children: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16 , 80 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0840-3

Download citation

Received : 08 May 2018

Accepted : 16 August 2019

Published : 05 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0840-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Child health

- Intervention

- Dietary assessment

- Child obesity

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity

ISSN: 1479-5868

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Help & FAQ

Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children: the healthy homework pilot study

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › Research › peer-review

| Original language | English |

|---|---|

| Pages (from-to) | 127 - 136 |

| Number of pages | 10 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 8 |

| DOIs | |

| Publication status | Published - 2011 |

| Externally published | Yes |

Access to Document

- 10.1186/1479-5868-8-127

Other files and links

- RM sElocation

T1 - Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children: the healthy homework pilot study

AU - Duncan, Scott

AU - McPhee, Julia C

AU - Schluter, Philip

AU - Zinn, Caryn

AU - Smith, Richard John McKenzie

AU - Schofield, Grant

UR - http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/127

U2 - 10.1186/1479-5868-8-127

DO - 10.1186/1479-5868-8-127

M3 - Article

SN - 1479-5868

JO - International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity

JF - International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity

- Advanced search

- Peer review

- Record : found

- Abstract : found

- Article : found

Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children: the healthy homework pilot study

Read this article at

- Download PDF

- Review article

- Invite someone to review

Most physical activity and nutrition interventions in children focus on the school setting; however, evidence suggests that children are less active and have greater access to unhealthy food at home. The aim of this pilot study was to examine the efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children.

The six-week 'Healthy Homework' programme and complementary teaching resource was developed under the guidance of an intersectoral steering group. Eight senior classes (year levels 5-6) from two diverse Auckland primary schools were randomly assigned into intervention and control groups. A total of 97 children (57 intervention, 40 control) aged 9-11 years participated in the evaluation of the intervention. Daily step counts were monitored immediately before and after the intervention using sealed multiday memory pedometers. Screen time, sports participation, active transport to and from school, and the consumption of fruits, vegetables, unhealthy foods and drinks were recorded concurrently in a 4-day food and activity diary.

Healthy Homework resulted in a significant intervention effect of 2,830 steps.day -1 (95% CI: 560, 5,300, P = 0.013). This effect was consistent between sexes, schools, and day types (weekdays and weekend days). In addition, significant intervention effects were observed for vegetable consumption (0.83 servings.day -1 , 95% CI: 0.24, 1.43, P = 0.007) and unhealthy food consumption (-0.56 servings.day -1 , 95% CI: -1.05, -0.07, P = 0.027) on weekends but not weekdays, with no interactions with sex or school. Effects for all other variables were not statistically significant regardless of day type.

Conclusions

Compulsory health-related homework appears to be an effective approach for increasing physical activity and improving vegetable and unhealthy food consumption in children. Further research in a larger study is required to confirm these initial results.

Related collections

Karger: Nutrition and Dietetics

Most cited references 40

- Article : not found

Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a 21-year tracking study.

Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: a systematic review.

Effect of school based physical activity programme (KISS) on fitness and adiposity in primary schoolchildren: cluster randomised controlled trial

Author and article information , affiliations.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Comment on this article

Similar content 464 .

- Reflecting on homework in psychotherapy: what can we conclude from research and experience? Authors: Nikolaos Kazantzis , Georgios K Lampropoulos

- Music Therapy for Depression Enhanced With Listening Homework and Slow Paced Breathing: A Randomised Controlled Trial Authors: Jaakko Erkkilä , Olivier Brabant , Martin Hartmann …

- Relationship Between Students’ Prior Academic Achievement and Homework Behavioral Engagement: The Mediating/Moderating Role of Learning Motivation Authors: Susana Rodriguez , José C. Núñez , Antonio Valle …

Cited by 23

- Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: the structured days hypothesis Authors: Keith Brazendale , Michael Beets , R Weaver …

- Family‐based interventions to increase physical activity in children: a systematic review, meta‐analysis and realist synthesis Authors: H. E. Brown , A. Atkin , J. Panter …

- Environmental interventions to reduce the consumption of sugar‐sweetened beverages and their effects on health Authors: Peter von Philipsborn , Jan Stratil , Jacob Burns …

Most referenced authors 589

Efficacy of a Compulsory Homework Programme for Increasing Physical Activity and Healthy Eating in Children: The Healthy Homework Pilot Study

Degree name, journal title, journal issn, volume title.

Background: Most physical activity and nutrition interventions in children focus on the school setting; however, evidence suggests that children are less active and have greater access to unhealthy food at home. The aim of this pilot study was to examine the efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children.

Methods: The six-week ‘Healthy Homework’ programme and complementary teaching resource was developed under the guidance of an intersectoral steering group. Eight senior classes (year levels 5-6) from two diverse Auckland primary schools were randomly assigned into intervention and control groups. A total of 97 children (57 intervention, 40 control) aged 9-11 years participated in the evaluation of the intervention. Daily step counts were monitored immediately before and after the intervention using sealed multiday memory pedometers. Screen time, sports participation, active transport to and from school, and the consumption of fruits, vegetables, unhealthy foods and drinks were recorded concurrently in a 4-day food and activity diary.

Results: Healthy Homework resulted in a significant intervention effect of 2,830 steps.day-1 (95% CI: 560, 5,300, P = 0.013). This effect was consistent between sexes, schools, and day types (weekdays and weekend days). In addition, significant intervention effects were observed for vegetable consumption (0.83 servings.day-1, 95% CI: 0.24, 1.43, P = 0.007) and unhealthy food consumption (-0.56 servings.day-1, 95% CI: -1.05, -0.07, P = 0.027) on weekends but not weekdays, with no interactions with sex or school. Effects for all other variables were not statistically significant regardless of day type.

Conclusions: Compulsory health-related homework appears to be an effective approach for increasing physical activity and improving vegetable and unhealthy food consumption in children. Further research in a larger study is required to confirm these initial results.

Description

Publisher's version, rights statement, permanent link, collections.

Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children: the healthy homework pilot study.

Most physical activity and nutrition interventions in children focus on the school setting; however, evidence suggests that children are less active and have greater access to unhealthy food at home. The aim of this pilot study was to examine the efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children. The six-week Healthy Homework programme and complementary teaching resource was developed under the guidance of an intersectoral steering group. Eight senior classes (year levels 5-6) from two diverse Auckland primary schools were randomly assigned into intervention and control groups. A total of 97 children (57 intervention, 40 control) aged 9-11 years participated in the evaluation of the intervention. Daily step counts were monitored immediately before and after the intervention using sealed multiday memory pedometers. Screen time, sports participation, active transport to and from school, and the consumption of fruits, vegetables, unhealthy foods and drinks were recorded concurrently in a 4-day food and activity diary. Healthy Homework resulted in a significant intervention effect of 2,830 steps.day-1 (95% CI: 560, 5,300, P = 0.013). This effect was consistent between sexes, schools, and day types (weekdays and weekend days). In addition, significant intervention effects were observed for vegetable consumption (0.83 servings.day-1, 95% CI: 0.24, 1.43, P = 0.007) and unhealthy food consumption (-0.56 servings.day-1, 95% CI: -1.05, -0.07, P = 0.027) on weekends but not weekdays, with no interactions with sex or school. Effects for all other variables were not statistically significant regardless of day type. Compulsory health-related homework appears to be an effective approach for increasing physical activity and improving vegetable and unhealthy food consumption in children. Further research in a larger study is required to confirm these initial results.

- DOI: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-127

- Corpus ID: 17153748

Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children: the healthy homework pilot study

- S. Duncan , J. McPhee , +3 authors G. Schofield

- Published in International Journal of… 15 November 2011

- Education, Medicine

55 Citations

Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and improving nutrition in children: a cluster randomised controlled trial, evaluation of school-based interventions including homework to promote healthy lifestyles: a systematic review with meta-analysis, promoting healthy weight in primary school children through physical activity and nutrition education: a pragmatic evaluation of the change randomised intervention study, active homework: an under-researched element of the active schools concept.

- Highly Influenced

- 10 Excerpts

Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Exploring the feasibility of a cluster pilot randomised control trial to improve children’s 24-hour movement behaviours and dietary intake: happy homework, the effects of the change intervention on children's physical activity and health, application of an online combination exercise intervention to improve physical and mental health in obese children: a single arm longitudinal study, effects of a recreational physical activity and healthy habits orientation program, using an illustrated diary, on the cardiovascular risk profile of overweight and obese schoolchildren: a pilot study in a public school in brasilia, federal district, brazil, fitness promotion in a jump rope-based homework intervention for middle school students: a randomized controlled trial, 60 references, evaluation of a pilot school programme aimed at the prevention of obesity in children., evaluation of the nutrition education at primary school (neaps) programme, promoting physical activity participation among children and adolescents., effect of school based physical activity programme (kiss) on fitness and adiposity in primary schoolchildren: cluster randomised controlled trial, evaluation of a community-based intervention to promote physical activity in youth: lessons from active winners, attitudes towards exercise and physical activity behaviours in greek schoolchildren after a year long health education intervention, school physical education: effect of the child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health., outcomes of a field trial to improve children's dietary patterns and physical activity. the child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health. catch collaborative group., the effects of a family fitness program on the physical activity and nutrition behaviors of third-grade children, a 4-year, cluster-randomized, controlled childhood obesity prevention study: stopp, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes

Effects of a recreational physical activity and healthy habits orientation program, using an illustrated diary, on the cardiovascular risk profile of overweight and obese schoolchildren: a pilot study in a public school in Brasilia, Federal District, Brazil

Angeliete garcez militão.

1 Department of Physical Education, Federal University of Rondonia, Brazil

2 Post-Graduate Program in Physical Education, Catholic University of Brasilia, Brazil

Margô Gomes de Oliveira Karnikowski

3 University of Brasilia, Brazil

Fernanda Rodrigues da Silva

4 Laboratory of Physical Evaluation and Training, Catholic University of Brasilia, Brazil

Elba Sancho Garcez Militão

Raiane maiara dos santos pereira.

5 Laboratory of Physical Education and Health Studies, Catholic University of Brasilia, Brazil

Carmen Silvia Grubert Campbell

Introduction.

Educative strategies need to be adopted to encourage the consumption of healthy foods and to promote physical activity in childhood and adolescence. The effects of recreational physical activity and a health-habit orientation program using an illustrated diary on the cardiovascular risk profile of overweight and obese children was investigated.

The weight and height of 314 schoolchildren aged between 9 and 11 years old, in a public school in Brasilia, Federal District, Brazil, were recorded. According to the body mass index (BMI) classification proposed by the World Health Organization, 84 were overweight or obese for their age and sex. Of these children, 34 (40%) participated in the study. Students were divided into two groups matched for sex, age, BMI, percent body fat (%BF): the intervention group (IG, n = 17) and the control group (CG, n = 17). The IG underwent a program of 10 weeks of exercise with recreational activities and health-habit orientation using an illustrated diary of habits, while no such interventions were used with the CG during the study period. Before and after the intervention, the children’s weight, height, BMI, %BF, waist circumference (WC), maximum oxygen intake (VO 2max ), total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, glucose, eating habits, and physical activity level (PAL) were assessed. In analyzing the data, we used descriptive statistics and paired and unpaired t -tests, using a significance level of 0.05. For assessment of dietary habits, a questionnaire, contingency tables, and the chi-squared test were used, with <0.05 set as the significance level.

After 10 weeks of intervention, the IG showed a reduction in BMI (pre: 22.2 ± 2.1 kg/m 2 versus [vs] post: 21.6 ± 2.1 kg/m 2 , P < 0.01); WC (pre: 70.1 ± 6.1 cm vs post: 69.1 ± 5.8 cm, P < 0.01); %BF (pre: 29.2% ± 4.6% vs post: 28.0% ± 4.8%, P < 0.01); systolic blood pressure ( P < 0.01); VO 2max ( P = 0.014); TC ( P < 0.01); LDL ( P < 0.01); triglycerides ( P < 0.01); and intake of candy ( P < 0.01) and soda drinks ( P < 0.01), while an increase in the consumption of fruit ( P < 0.01) and PAL ( P < 0.01) were observed. The CG did not show any change in the health parameters assessed.

The program was effective in reducing risk factors for cardiovascular disease and the use of an illustrative diary may have been the key to this result, since students were motivated to change their poor eating habits and to increase their physical activity level.

Worldwide, obesity is considered to be the epidemic of twenty-first century, and is related to the development of insulin resistance and diabetes, as well as to the predisposition to increases in serum levels of cholesterol and systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure, which are risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD). 1

An analysis of Korean teenagers found that levels of total cholesterol (TC) increased significantly with increasing body mass index (BMI). 2 Furthermore, Reinehr et al 3 in Germany and May et al 4 in the USA found that obese children, when compared with those of normal weight, had higher concentrations of low density lipoprotein (LDL) and lower concentrations of high density lipoprotein (HDL). In Brazil, a positive correlation of waist circumference (WC) and BMI, with blood pressure was observed in schoolchildren in Taguatinga, Federal District. 5

Data from the VIGITEL Brasil 2011: Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico [Surveillance of risk and protective factors for chronic diseases by telephone survey] 6 revealed that the proportion of overweight persons in Brazil had increased, from 42.7% in 2006 to 48.5% in 2011, while the percentage of obese persons increased from 11.4% to 15.8%. In the Federal District, in the same period, the percentage of the population that was overweight or obese increased from 39.8% to 49.2% and from 10% to 15%, respectively. 6 These data show that strategies should be implemented to curb and reduce weight gain in this population.

A way to prevent obesity in adulthood is to treat childhood overweight and obesity. Once excess weight is present in childhood and adolescence it tends to persist in older ages. 7 Further, atherosclerosis and arterial hypertension, pathological processes that start in childhood; life phase; eating habits; physical activity level (PAL); and environmental factors are determining the increase in obesity prevalence. 8

Educative strategies should be adopted to encourage the consumption of healthy foods and to promote physical activity in childhood and adolescence. The school environment is a good place to promote a healthy lifestyle, because this is a place of intense social interaction and is appropriate for educative activities. 9 In particular, school physical education classes represent particularly suitable venues for dissemination of information, discussion, and reflection on healthy habits.

In this regard, our group has created a learning tool for use in physical education classes called an “illustrative diary” that aims to promote knowledge that will motivate students to adopt a healthy diet and to reduce sedentary behavior (watching television, playing video games, and computer use). 10 The instrument consists of a paper pad with blank squares representing each day of the week, which the students fill with figures representing their activities during the day concerning nutrition, physical activities, and sedentary behaviors. Thus, the aim of the study reported here was to evaluate the effects of a program of recreational physical activities, associated with the use of the illustrative diary, on the cardiovascular risk profile of overweight and obese schoolchildren.

Study design and sample selection

This was a pilot study with experimental delimitation conducted in Classe 46 School in Ceilândia, Federal District, Brazil. Students born between 2001 and 2003 enrolled in that school were invited to have their height and weight assessed to identify those overweight and obese for inclusion in the study. A total of 314 students attended the evaluations, of whom 84 were classified as overweight (≥85th and <95th percentile) and obese (>95th percentile) for their age and sex according to the World Health Organization’s BMI classification. 11

From the 84 children classified as overweight and obese, 34 (40%) consented to participate in the study and they were organized into two homogeneous and internally heterogeneous groups, between them, with the same number of participants, and number of males and females in each. The intervention group (IG), which comprised eight male and nine female participants, submitted to a program of recreational physical activity and orientation to healthy lifestyle using the illustrative diary, while the control group (CG), again comprising eight male and nine female participants, continued with their daily normal activities.

The parents of the schoolchildren signed informed consent in accordance with Brazilian Resolution 196/96. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Brasilia (protocol CAAE07297412.4.0000.0029).

Evaluations

Pubertal development, weight, height, WC, cardiorespiratory fitness, blood pressure, and biochemical parameters (fasting glucose [FG], TC, LDL, HDL, and triglyceride [TG] levels) were assessed and skinfold measurements taken. In addition, the level of physical activity and eating habits were measured before and after intervention.

To measure body weight, the adolescents, wearing school uniform and barefoot, were positioned standing on a Wiso scale, model W721 (Wiso, Sportive Technology, Florianopolis, Brazil) with digital display and 100 g of precision while being asked to keep still and stand erect in the middle of the scale, with their arms along their body. For evaluation of stature, a Sanny compact stadiometer, model ES:2040 (Sanny – American Medical do Brasil, Ltda, São Bernardo do Campo, Brazil) fixed on a wall without a gap, accurate to 1 mm, was used with the teenagers barefoot and leaning against the wall, heels together, hands relaxed along the body, and head adjusted in the Frankfurt plane. BMI was determined using the formula: weight in kg/m 2 ). The cutoff points proposed by the World Health Organization classification were used. 11

For evaluation of WC, a Sanny fiberglass tape with a precision of 1 mm was used. The measurement was taken from the lower circumference, located midpoint between the last rib and iliac crest. Tricipital (TR) and subscapular (SB) skinfolds were measured with a Lange Skinfold Caliper skinfold compass (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) with resolution of 5 mm. For measurement of the triciptal, the compass was placed on the back of the right arm of the adolescent, at the midpoint between the lateral projection of the acromion process and inferior margin of the olecranon. The subscapular was measured 1 cm below the inferior angle of the scapula. The %BF was estimated from the results of the sum of the TR and SB using Boileau et al’s equation. 12

Cardiorespiratory fitness, expressed as maximum oxygen uptake (VO 2max [mL·kg −1 ·min −1 ]), was obtained from a 20 m shuttle run test according to the procedure and equations outlined by Léger and Lambert. 13 This test consists of a running in a limited space of 20 m, where the students were submitted to a run in the rhythm of a sound signal. In each signal, they should reach one end marked. The signal is based on the speed (km/h), which starts with 8.5 km/h, increasing by 0.5 km/h each time, until the evaluated student can’t reach one of the extremities after two consecutive signals. The test was conducted in the same school to which they belonged. The track was marked in a span of 20 m and two students took the test at a time, each one supervised by a physical education professional. Leger et al’s formula was used to estimate the VO 2max , using the age and average speed (km/h) data. To identify the extent of pubertal development, the self-assessment method proposed by Tanner 14 was employed. This method allows the student to identify their own maturity stage by observing the development of pubic hair. Individually, each student reported to a researcher of the same sex as themselves, which image presented to them they most identified with. From their responses, each was classified as either prepubescent (stage 1), pubescent (stages 2–4), or postpubescent (stage 5).

Blood pressure was measured three times at intervals of 2 minutes. Before the first measurement, the student sat for 5 minutes. An automatic digital monitor (Omron Hem 705 CP, Omron, Tokyo, Japan) was used with clamps of suitable size with a width of approximately 40% of the arm circumference. The measurements were performed on the right arm and the mean of the three assessments was considered.

For biochemical evaluations, a technician from the Clinical Laboratory of the University of Brasilia went to Classe 46 School between 7.30 and 8.30 am to collect blood by venipuncture. The children were required to fast for 12 hours prior to having their blood collected. Blood (10 mL) was collected in a tube with a gel separator and under vacuum without anticoagulant and transported in a Styrofoam box with dry ice to the analytical laboratory of the University Hospital of Brasilia. For determination of FG, TC, HDL, LDL, and TG, the following methods were used: serum/hexokinase automated and serum/esterase-oxidase, oxidase-peroxidase and Friedewald formula. Dosage of FG was performed with an automated method (colorimetric enzymatic glucose-hexoxidase) in an ARCHITECT C8000 Analyzer (Abbott, Illinois, USA), using 5 mL of serum after being centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 minutes. TC, TG and HDL were analyzed using the enzymatic colorimetric method utilising esterase-oxidase and oxidase-peroxidase, using 5 mL of serum after being centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 minutes. The LDL fraction was obtained using the formula proposed by Friedewald et al. 15 The measurements were performed with the automated method on device ARCHITECT C8000 Analyzer (Abbott, Illinois, USA).

The metabolic equivalent (MET) is defined as the oxygen uptake equivalent to a sitting quietly position (3.5 mL·kg −1 ·min −1 ). The PAL was obtained in MET/week by using the Level of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Teenager Students questionnaire, created and validated by our group. 16 In this questionnaire students were classified into the following categories: sedentary (PAL less than 600 MET/week), irregularly active (PAL greater than 600 and less than 1,500 MET/week), active (PAL greater than 1,500 and less than 3,000 MET/week) and very active (PAL greater than 3,000 MET/week). Dietary habits were assessed by the questionnaire Risk Behaviors of Adolescents Catarinenses – COMPAC 17 in which students were asked about the weekly frequency of consumption of fruit juice, vegetables, fruits, sodas, chips, pasta, sweets, meat, rice and beans.

Intervention program

Students in the IG performed recreational physical activities and received guidance on healthy habits, in a different timetable than they normally study, during 10 weeks, with 20 sessions of 60 minutes each. Each session comprised 5 minutes of stretching, 40 minutes of basic motor recreational activities (running, jumping, and throwing), and 15 minutes recovery time, which included guidance on healthy habits and use of the illustrative diary.

Recreational activities were planned and directed by a physical education teacher to ensure that the children would be active throughout the period doing activities at a moderate to vigorous intensity (65% to 85% of maximum heart rate obtained in the described 20 m shuttle run test). During the activities, students’ heart rate was monitored using a monitor Polar F1TM (Polar Electro Oy, FIN-90440 Kempele, Finland) to ensure the group was exercising within the recommended range.

In terms of the guidance on healthy habits, on the first day of the intervention, each student received a journal made of A4 paper containing pictures representing each weekday, and pages displaying various images of food (fruit, vegetables, candy, fried foods, soft drinks, fruit juice, etc), sedentary activities (watching TV, using a computer, playing video games), and active behavior (jumping rope, jogging, playing soccer, cycling, etc). Colorful pictures were used to represent healthy habits, while black and white pictures were used to represent unhealthy habits. Children were asked to paste pictures into their diary to represent the activities done and foods eaten and to write down the amount of times that they consumed each particular food and the time spent doing each activity. The parents of the students received a note explaining the diary completion activity and recommending that children should take it to school each day that a study recreational activity session was scheduled.

At the end of each recreational activity session, students showed the diary pages that they had filled in daily at home to the teacher and proper habits and inadequate health care were discussed, with the intention of motivating students to improve their lifestyle and making their diaries more colorful as a result.

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations were initially used for variables with parametric distribution. The Shapiro–Wilk test was performed to evaluate the variables’ adherence to a normal curve, where all showed normality ( P < 0.05). Paired and non-paired t -tests were used to compare data between variables. For data analysis of the questionnaire assessment of dietary habits, we used contingency tables and chi-square tests. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 17.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), using a significance level of P < 0.05.

The sample included 34 children (nine girls and eight boys in each group). The mean age of children in the IG and CG was 9.9 years and 10.1 years, respectively. Students were prepubescent and pubescent. All the girls were pubertal and 25% of the boys were prepubertal. The students were divided evenly between both groups to avoid interference of biological age in the research results.

There were no significant differences between the IG and CG in terms of anthropometric parameters, biochemical parameters, blood pressure, or VO 2max , both before and after the intervention. However, when comparing results within the same group, it was observed that unlike the CG, the IG showed significant differences in almost all variables, showing positive reductions in risk factors for CVD ( Table 1 ).

Characteristics of intervention group and control group pre- and post-intervention

| Variable | Intervention (n = 17) | -value | Control (n = 17) | -value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Age (years) | 9.94 ± 0.83 | 10.00 ± 0.93 | – | 10.12 ± 0.86 | 10.12 ± 0.86 | – |

| Weight (kg) | 46.75 ± 7.49 | 46.25 ± 7.46 | 0.012 | 48.05 ± 7.15 | 48.95 ± 8.43 | 0.28 |

| Height (cm) | 1.45 ± 0.9 | 1.46 ± 0.9 | 0.000 | 1.48 ± 0.8 | 1.49 ± 0.08 | 0.00 |

| BMI (kg/m ) | 22.21 ± 2.15 | 21.6 ± 2.08 | 0.000 | 22.17 ± 1.08 | 21.89 ± 2.24 | 0.18 |

| WC (cm) | 70.16 ± 6.15 | 69.15 ± 5.84 | 0.001 | 71.4 ± 4.93 | 71.14 ± 5.99 | 0.60 |

| %BF | 29.25 ± 4.57 | 28.05 ± 4.77 | 0.003 | 29.69 ± 4.88 | 29.53 ± 0.61 | 0.61 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 106.02 ± 9.57 | 101.72 ± 10.37 | 0.000 | 108.25 ± 8.8 | 104.74 ± 8.65 | 0.22 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 65.12 ± 8.25 | 62.92 ± 9.06 | 0.308 | 70.58 ± 11.8 | 65.5 ± 5.22 | 0.10 |

| VO (mL·kg ·min ) | 43.35 ± 2.01 | 44.3 ± 2.37 | 0.014 | 42.95 ± 3.24 | 43.5 ± 3.51 | 0.10 |

| FG (mg/dL) | 84.29 ± 4.01 | 82.12 ± 5.38 | 0.153 | 83.71 ± 8.47 | 84.71 ± 8.44 | 0.45 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 168.82 ± 29.03 | 154.0 ± 26.72 | 0.000 | 158.94 ± 32.59 | 153.88 ± 29.59 | 0.15 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 43.29 ± 8.08 | 41.88 ± 7.36 | 0.152 | 40.71 ± 7.69 | 38.29 ± 9.02 | 0.09 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 107.53 ± 28.38 | 99.76 ± 26.8 | 0.000 | 101.41 ± 28.54 | 95.88 ± 23.92 | 0.17 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 90.24 ± 28.02 | 70.76 ± 24.85 | 0.002 | 83.82 ± 33.46 | 99.0 ± 58.46 | 0.18 |

Abbreviations: %BF, percent body fat; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FG, fasting glucose; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; VO 2max , maximum oxygen intake; WC, waist circumference.