Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

You won’t even know you’re exercising, but your body will

What’s another word for ‘neuronal map-maker’?

How leaders find happiness — and teach it

When love and science double date.

Illustration by Sophie Blackall

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Sure, your heart thumps, but let’s look at what’s happening physically and psychologically

“They gave each other a smile with a future in it.” — Ring Lardner

Love’s warm squishiness seems a thing far removed from the cold, hard reality of science. Yet the two do meet, whether in lab tests for surging hormones or in austere chambers where MRI scanners noisily thunk and peer into brains that ignite at glimpses of their soulmates.

When it comes to thinking deeply about love, poets, philosophers, and even high school boys gazing dreamily at girls two rows over have a significant head start on science. But the field is gamely racing to catch up.

One database of scientific publications turns up more than 6,600 pages of results in a search for the word “love.” The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is conducting 18 clinical trials on it (though, like love itself, NIH’s “love” can have layered meanings, including as an acronym for a study of Crohn’s disease). Though not normally considered an intestinal ailment, love is often described as an illness, and the smitten as lovesick. Comedian George Burns once described love as something like a backache: “It doesn’t show up on X-rays, but you know it’s there.”

Richard Schwartz , associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and a consultant to McLean and Massachusetts General (MGH) hospitals, says it’s never been proven that love makes you physically sick, though it does raise levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that has been shown to suppress immune function.

Love also turns on the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is known to stimulate the brain’s pleasure centers. Couple that with a drop in levels of serotonin — which adds a dash of obsession — and you have the crazy, pleasing, stupefied, urgent love of infatuation.

It’s also true, Schwartz said, that like the moon — a trigger of its own legendary form of madness — love has its phases.

“It’s fairly complex, and we only know a little about it,” Schwartz said. “There are different phases and moods of love. The early phase of love is quite different” from later phases.

During the first love-year, serotonin levels gradually return to normal, and the “stupid” and “obsessive” aspects of the condition moderate. That period is followed by increases in the hormone oxytocin, a neurotransmitter associated with a calmer, more mature form of love. The oxytocin helps cement bonds, raise immune function, and begin to confer the health benefits found in married couples, who tend to live longer, have fewer strokes and heart attacks, be less depressed, and have higher survival rates from major surgery and cancer.

Schwartz has built a career around studying the love, hate, indifference, and other emotions that mark our complex relationships. And, though science is learning more in the lab than ever before, he said he still has learned far more counseling couples. His wife and sometime collaborator, Jacqueline Olds , also an associate professor of psychiatry at HMS and a consultant to McLean and MGH, agrees.

Spouses Richard Schwartz and Jacqueline Olds, both associate professors of psychiatry, have collaborated on a book about marriage.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

More knowledge, but struggling to understand

“I think we know a lot more scientifically about love and the brain than we did a couple of decades ago, but I don’t think it tells us very much that we didn’t already know about love,” Schwartz said. “It’s kind of interesting, it’s kind of fun [to study]. But do we think that makes us better at love, or helping people with love? Probably not much.”

Love and companionship have made indelible marks on Schwartz and Olds. Though they have separate careers, they’re separate together, working from discrete offices across the hall from each other in their stately Cambridge home. Each has a professional practice and independently trains psychiatry students, but they’ve also collaborated on two books about loneliness and one on marriage. Their own union has lasted 39 years, and they raised two children.

“I think we know a lot more scientifically about love and the brain than we did a couple of decades ago … But do we think that makes us better at love, or helping people with love? Probably not much.” Richard Schwartz, associate professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

“I have learned much more from doing couples therapy, and being in a couple’s relationship” than from science, Olds said. “But every now and again, something like the fMRI or chemical studies can help you make the point better. If you say to somebody, ‘I think you’re doing this, and it’s terrible for a relationship,’ they may not pay attention. If you say, ‘It’s corrosive, and it’s causing your cortisol to go way up,’ then they really sit up and listen.”

A side benefit is that examining other couples’ trials and tribulations has helped their own relationship over the inevitable rocky bumps, Olds said.

“To some extent, being a psychiatrist allows you a privileged window into other people’s triumphs and mistakes,” Olds said. “And because you get to learn from them as they learn from you, when you work with somebody 10 years older than you, you learn what mistakes 10 years down the line might be.”

People have written for centuries about love shifting from passionate to companionate, something Schwartz called “both a good and a sad thing.” Different couples experience that shift differently. While the passion fades for some, others keep its flames burning, while still others are able to rekindle the fires.

“You have a tidal-like motion of closeness and drifting apart, closeness and drifting apart,” Olds said. “And you have to have one person have a ‘distance alarm’ to notice the drifting apart so there can be a reconnection … One could say that in the couples who are most successful at keeping their relationship alive over the years, there’s an element of companionate love and an element of passionate love. And those each get reawakened in that drifting back and forth, the ebb and flow of lasting relationships.”

Children as the biggest stressor

Children remain the biggest stressor on relationships, Olds said, adding that it seems a particular problem these days. Young parents feel pressure to raise kids perfectly, even at the risk of their own relationships. Kids are a constant presence for parents. The days when child care consisted of the instruction “Go play outside” while mom and dad reconnected over cocktails are largely gone.

When not hovering over children, America’s workaholic culture, coupled with technology’s 24/7 intrusiveness, can make it hard for partners to pay attention to each other in the evenings and even on weekends. It is a problem that Olds sees even in environments that ought to know better, such as psychiatry residency programs.

“There are all these sweet young doctors who are trying to have families while they’re in residency,” Olds said. “And the residencies work them so hard there’s barely time for their relationship or having children or taking care of children. So, we’re always trying to balance the fact that, in psychiatry, we stand for psychological good health, but [in] the residency we run, sometimes we don’t practice everything we preach.”

“There is too much pressure … on what a romantic partner should be. They should be your best friend, they should be your lover, they should be your closest relative, they should be your work partner, they should be the co-parent, your athletic partner. … Of course everybody isn’t able to quite live up to it.” Jacqueline Olds, associate professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

All this busy-ness has affected non-romantic relationships too, which has a ripple effect on the romantic ones, Olds said. A respected national social survey has shown that in recent years people have gone from having three close friends to two, with one of those their romantic partner.

More like this

Strength in love, hope in science

Love in the crosshairs

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

“Often when you scratch the surface … the second [friend] lives 3,000 miles away, and you can’t talk to them on the phone because they’re on a different time schedule,” Olds said. “There is too much pressure, from my point of view, on what a romantic partner should be. They should be your best friend, they should be your lover, they should be your closest relative, they should be your work partner, they should be the co-parent, your athletic partner. There’s just so much pressure on the role of spouse that of course everybody isn’t able to quite live up to it.”

Since the rising challenges of modern life aren’t going to change soon, Schwartz and Olds said couples should try to adopt ways to fortify their relationships for life’s long haul. For instance, couples benefit from shared goals and activities, which will help pull them along a shared life path, Schwartz said.

“You’re not going to get to 40 years by gazing into each other’s eyes,” Schwartz said. “I think the fact that we’ve worked on things together has woven us together more, in good ways.”

Maintain curiosity about your partner

Also important is retaining a genuine sense of curiosity about your partner, fostered both by time apart to have separate experiences, and by time together, just as a couple, to share those experiences. Schwartz cited a study by Robert Waldinger, clinical professor of psychiatry at MGH and HMS, in which couples watched videos of themselves arguing. Afterwards, each person was asked what the partner was thinking. The longer they had been together, the worse they actually were at guessing, in part because they thought they already knew.

“What keeps love alive is being able to recognize that you don’t really know your partner perfectly and still being curious and still be exploring,” Schwartz said. “Which means, in addition to being sure you have enough time and involvement with each other — that that time isn’t stolen — making sure you have enough separateness that you can be an object of curiosity for the other person.”

Share this article

You might like.

Real surfing is better than channel surfing, says research focused on healthy aging. But housework is better than nothing.

Researchers discover microscopic ‘brain thesaurus’ that lets neurons derive meaning from spoken words

Symposium examines science, outlines opportunities to tackle mental health crisis

When should Harvard speak out?

Institutional Voice Working Group provides a roadmap in new report

Had a bad experience meditating? You're not alone.

Altered states of consciousness through yoga, mindfulness more common than thought and mostly beneficial, study finds — though clinicians ill-equipped to help those who struggle

College sees strong yield for students accepted to Class of 2028

Financial aid was a critical factor, dean says

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 31 January 2024

A decade of love: mapping the landscape of romantic love research through bibliometric analysis

- Yixue Han 1 ,

- Yulin Luo 1 ,

- Zhuohong Chen 1 ,

- Nan Gao 1 ,

- Yangyang Song 1 &

- Shen Liu 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 187 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

3831 Accesses

24 Altmetric

Metrics details

Given the limited availability of bibliometric and visual analysis on the topic of romantic love, the primary objective of the current study is to fill this gap by conducting a comprehensive visual analysis of relevant literature. Through this analysis, the current study aimed to uncover current research trends and identify potential future directions in the field of romantic love. The current study’s search criteria were met by an impressive 6858 publications found in the Web of Science database for the period between 2013 and 2022. A thorough analysis was conducted on the bibliographic visualization of the authors, organizations, countries, references, and keywords. Over time, there has been a remarkable surge in the number of significant publications. Among the authors in the field of romantic love, Emily A. Impett has emerged as the most prolific. The Journal of Social and Personal Relationships is indeed one of the top journals that has published a significant number of articles on the topic of romantic love. During the preceding decade, the University of California System emerged as a prominent producer of publications centered around romantic love, solidifying the United States’ position as a dominant player in this field. In recent times, there has been a significant surge in the popularity of keywords such as “same-sex,” “conflict resolution,” and “social relationships” within academic literature. These topics have experienced a burst of attention, as evidenced by a substantial increase in references and citations. Through the use of visualization maps and analysis of key publications, the current study offers a comprehensive overview of the key concepts and potential avenues for future research in the field of romantic love. Gaining a deep understanding of the complex dynamics and societal implications of romantic love has been instrumental in formulating policies that embody increased compassion and support. As a result, these policies have played a pivotal role in fostering resilient familial ties and contributing to the enduring stability and prosperity of our social fabric.

Similar content being viewed by others

Who reads contemporary erotic novels and why?

The cultural evolution of love in literary history

Meanings and implications of love: review of the scholarship of love with a sub-Saharan focus

Introduction, the development course of romantic love.

Romantic love, as defined by Hatfield and Rapson ( 1987 ) as an intense longing for union with another, has long been recognized as a driving force behind some of humanity’s most remarkable achievements. Studies by Bartels and Zeki ( 2000 ) and the work of Fehr ( 2013 , 2015 ) have further emphasized its profound impact. Previous research has suggested that romantic love has a crucial role in the development and maintenance of romantic relationships. It involves a transition from the significant investment of time and attention in the initial stages to enhanced communication and satisfaction in committed partnerships (Mizrahi et al. 2022 ). However, recent research has shown that in the United States, the divorce rate has consistently remained at historically high levels. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ( 2017 ), ~40–50% of first marriages end in divorce. In recent times, there has been a trend toward shorter and more prevalent romantic relationships. Alirezanejad ( 2022 ) found that different generations of women have maintained distinct expectations and experiences when it comes to love. Additionally, the significance of commitment in romantic relationships has witnessed a decline. These findings also indicate that there are additional factors at play that influence the dynamics between romantic love and the duration of relationships. The triangular theory of love, being one of the most widely used theories on romantic love, proposes that romantic love consists of three components: intimacy, passion, and an absence of commitment, alongside a willingness to invest resources without expecting reciprocation (Jimenez-Picon et al. 2022 ). The Love Attitude Scale (LAS) developed by Clyde and Susan Hendrick has been a significant contribution in the study of romantic love using psychometric methods. Tobore ( 2020 ) introduced a comprehensive four-fold framework that aims to elucidate the dynamics of how love evolves and diminishes. This framework includes the elements of attraction, empathy or connection, trust, and respect. As a result, the enigmatic and unique nature of romantic love has captivated the attention of scholars from various disciplines, including psychology, biology, sociology, and neuroscience. These scholars have conducted extensive research and investigations into the complexities of romantic love. Thus, the present study conducted a comprehensive and in-depth analysis and discourse on romantic love, spanning multiple research domains. Additionally, the publication emphasized the influence of romantic love on positive emotions as well as its association with various negative behaviors. Furthermore, it underscored the importance of utilizing bibliometric analysis as a valuable approach to study and understand romantic love.

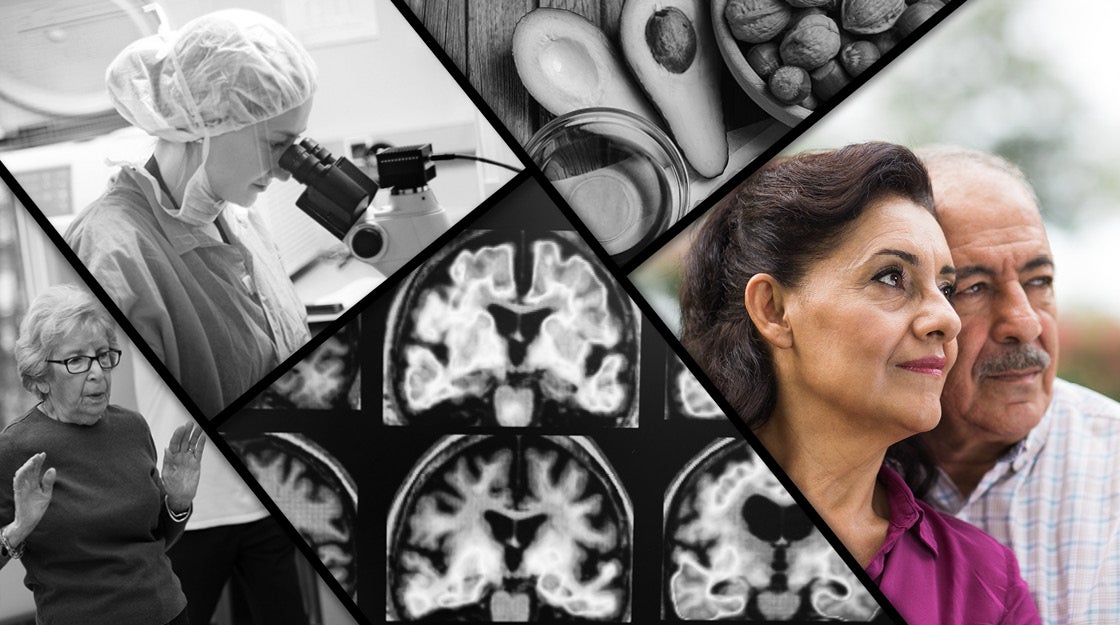

The research directions of romantic love in different disciplines

Psychologists have focused on exploring the relationship between romantic love and negative emotions in individuals with mental illnesses. Lafontaine et al. ( 2020 ) found a correlation between romantic love insecurity, specifically anxiety and avoidance, and the occurrence of intimate partner violence (IPV). This pattern of behavior was shown to undermine relationships and diminish individuals’ sense of security. Moreover, individuals with schizophrenia and other mental health conditions faced significant challenges in building and sustaining healthy interpersonal connections, partly due to the enduring stigma associated with mental illness (Budziszewska et al. 2020 ). Biological researchers have delved into the physiological activities and responses associated with romantic love. Furthermore, biological research has demonstrated that communication plays a crucial role in enhancing romantic relationships by facilitating physiological and behavioral adaptations between partners. For instance, a study by Zeevi et al. ( 2022 ) revealed that men and women in a romantic relationship can enhance their romantic interest in each other by synchronizing their skin electrical activities and modifying their behavior. These findings suggest that the social adaptation of the sympathetic nervous system and motor behavior play a critical role in the romantic attraction between partners. Furthermore, recent biological research conducted by Kerr et al. ( 2022 ) has discovered a correlation between unsuitable adult attachment in romantic relationships and the interpersonal circumplex, which is a component of personality pathology. Furthermore, a sociological study on pair-bonding conducted by Fletcher et al. ( 2015 ) highlighted that romantic love is intricately linked to the evolution and survival of Homo sapiens, making it a biologically significant function with profound evolutionary implications. Neuroscientists have examined the activation of different brain regions that are triggered by romantic love activities. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has emerged as a prominent technique for studying the neurobiological basis of love. Researchers such as Acevedo et al. ( 2020 ) and Chester et al. ( 2021 ) have utilized fMRI to investigate the neural correlates of romantic love and gain insights into the brain mechanisms underlying this complex phenomenon. Neuroscientists have identified specific brain regions associated with love, including the insula and anterior cingulate cortex. These regions are involved in the processing of emotional experiences related to valued objects. A study by Bartels and Zeki ( 2000 ) highlighted the involvement of these brain regions in the experience of romantic love, shedding light on the neural mechanisms underlying the emotional aspects of love. The activation of reward-related areas in the brain, particularly those rich in oxytocin, has been observed in individuals experiencing love. Studies by Acevedo et al. ( 2012 ) and Bartels and Zeki ( 2004 ) have shown that regions associated with reward processing, such as the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens, are involved in the experience of romantic love. Indeed, the involvement of the reward system in love has surpassed expectations. During the initial stages of romantic love, research conducted by Fisher et al. ( 2010 ) has shown that reward-related brain regions, including the bilateral ventral tegmental areas, are activated more strongly compared to the later stages of passion.

The social impact of romantic love

Undoubtedly, falling in love has a profound impact on people’s daily lives, as highlighted by research conducted by Quintard et al. ( 2021 ). Falling in love has been associated with enhanced well-being and has been correlated with fervor, activity, pleasure, and other positive emotions, as noted in research conducted by Langeslag ( 2022 ). However, it is important to acknowledge that the pitfalls of romantic love are often overlooked. Research, such as that conducted by Lonergan et al. ( 2022 ), has found associations between romantic love and criminal activity as well as psychological disorders. Additionally, studies by Aron et al. ( 2005 ), Merritt et al. ( 2022 ) and Li et al. ( 2022 ) have highlighted the presence of unpleasant affective states such as hyperarousal, anxiety, and depression in the context of romantic love. In recent decades, romantic love has undergone significant transformations that have had a substantial impact on both personal and societal life, as emphasized by research conducted by Reis et al. ( 2013 ).

The necessity of bibliometric analysis

Bibliometrics is a field that encompasses the quantitative study of documents, aiming to provide researchers with insights into academic, technological, and scientific advancements (William and Concepción 2001 ). The methodology utilized a range of techniques, including author analysis, concept mapping, clustering, factor analysis, and citation analysis, to investigate historical data and assist scholars in identifying significant trends and emerging directions within their disciplines (Daim et al. 2006 ; Hou et al. 2022 ). The term “bibliometrics” was coined by the distinguished British scientist Allen Richard in 1969, replacing the previously employed term “statistical bibliography.” In recent years, there has been a surging interest in this approach, with a growing number of researchers incorporating it into their work. Bibliometric analysis has been employed in various research domains, including the study of romantic love. These analyses offer valuable insights into the research areas that have been investigated, as well as potential future trends, challenges, and opportunities in the field. To the best of our knowledge, there have been limited previous publications that have specifically analyzed romantic love based on the triangular theory of love development and explored the concept across different disciplines.

In the current study, we utilized state-of-the-art analytical tools, including CiteSpace (6.2.R2), VOSviewer (1.6.18), Microsoft Excel (2019), and Scimago Graphica (1.0.26), in conjunction with the most recent data obtained from the Web of Science (WOS) core collection database. These tools allowed us to conduct a comprehensive bibliometric and visual analysis of publications related to romantic love published in the last decade. By employing these cutting-edge tools and leveraging the extensive data available from WOS, we aimed to gain valuable insights into the research landscape surrounding romantic love during this specific time frame. Our study aimed to achieve several objectives. First, we sought to identify the current research hotspots and trends within the field of romantic love. Second, we aimed to conduct an in-depth examination of visual maps and seminal articles, providing a comprehensive overview of the literature.

Material and methods

Data acquisition and search strategy.

The Web of Science (WOS) platform served as a valuable resource, containing a vast collection of over 9000 significant academic articles. This database stands as one of the oldest and most comprehensive citation index records, encompassing a wide range of disciplines, including social science, engineering technology, biomedicine, arts and humanities, and various other subjects. Since its establishment in 1900, the Web of Science (WOS) has served as a cornerstone of scholarly research and has wielded significant influence within academic circles (Ellegaard and Wallin 2015 ). The quantitative analysis feature of the platform facilitated the acquisition of various types of information related to scholarly publications. This included data on the annual number of papers published, papers published by state or region, popular journals within specific disciplines, frequently utilized publishing houses, and highly downloaded and cited literature. Indeed, references that receive multiple citations play a crucial role in providing a robust foundation for the study of romantic love, as emphasized by Xu et al. ( 2022 ).

The subject matter of romantic love and its interrelation with romantic relationships has a profound impact on the satisfaction and longevity of love between individuals, as highlighted by Zagefka ( 2022 ). Passionate love is a fundamental concept within romantic relationships, as emphasized by Mizrahi et al. ( 2022 ). Sternberg’s triangular theory of love stands as one of the most substantial and frequently referenced frameworks for understanding love, as noted by Sorokowski et al. ( 2021 ). To comprehensively explore the topic, the search strategy incorporated the inclusion of the following elements: The topic could encompass “romantic love,” OR “passionate love,” OR “romantic relationship,” OR “triangular theory of love.”‘ The search was conducted within the Web of Science Core Collection database, which covers the time period from 2013 to 2022. The database indexes the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED) and Social Science Citation Index-Expanded (SSCI-EXPANDED). The search was limited to publications written in the English language. To refine the search and focus on specific types of publications, certain categories were excluded from the search results. These excluded categories included early access, book chapters, proceeding papers, data papers, and retracted publications. By excluding these categories, the search aimed to prioritize reviews and articles, which are typically considered primary sources of scholarly information. As a result of these refined search criteria, a total of 6858 relevant items were identified and included in the analysis.

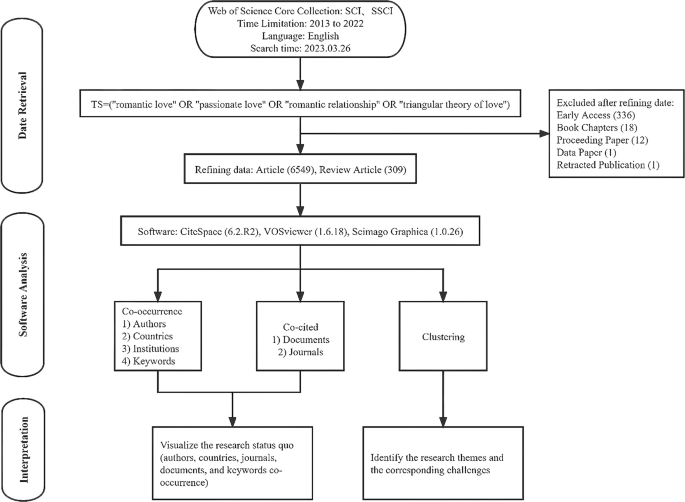

The retrieval strategy employed in this research was designed to maintain the integrity and impartiality of the search process (see Fig. 1 ).

To ensure that the search results were not influenced by daily database updates, all searches were conducted on a single day, specifically on March 26, 2023.

Analysis tool

For bibliometric analysis, the current study utilized a powerful combination of CiteSpace (6.2.R2), VOSviewer (1.6.18), Microsoft Excel (2019), and Scimago Graphica (1.0.26). These state-of-the-art software tools seamlessly integrated insights from scientometrics, information science, computer science, and other related fields to generate highly intuitive and informative visual maps. These maps revealed the development trajectory and structural underpinnings of scientific research. Indeed, each of these four software applications held unique and irreplaceable significance, excelling in specific domains of bibliometric analysis. Excel, for instance, demonstrated unparalleled proficiency in the intuitive transformation of charts. CiteSpace specialized in the clustering of topics and the delineation of the spatio-temporal background of words. VOSviewer played a pivotal role in both displaying and analyzing keywords, leveraging its distinctive capabilities. Lastly, Scimago Graphica contributed significantly to the geographical perspective of statistical analysis, offering insights that were unmatched in their comprehensiveness. Collectively, these tools not only proved indispensable but also brought their individual strengths to the forefront, contributing uniquely to the overall analytical landscape. Indeed, the Excel program was commonly employed to comprehensively analyze key data points such as the number of published papers, frequency of citations, and matched published documents. It was also employed to synthesize all the information for creating intuitive visual representations (Fig. 2 ) to illustrate the trends in the number of publications, citations, and their corresponding fitting functions during different periods. The use of CiteSpace in the current study was focused on highlighting the most salient occurrence burst on a timeline map and detecting the centrality of romantic love studies (Zhang et al. 2022a ). In order to attain a comprehensive understanding of the progress in romantic love research, an evolutionary analysis was undertaken, utilizing CiteSpace’s burst function. Co-occurrence analysis on pertinent keywords is another valuable method used to gain insights into the relationships and patterns among keywords in a specific research domain. Indeed, the analyses conducted, including the evolutionary analysis and co-occurrence analysis, facilitated an examination of the prevailing themes and trends of romantic love across different generations from a chronological perspective. VOSviewer, a powerful visualization tool, was utilized in the current study to portray the borders of romantic love with varying color clusters. It also facilitated the exploration of the co-occurrence of authors, institutions, and keywords associated with romantic love. The circles of various colors and sizes were used to represent the occurrence frequency of distinct cluster words and different keywords, respectively. The examination of keywords in the current study, augmented by chart analysis, delved into a more profound, comprehensive, and scientific level. Scimago Graphica 1.0.18, a tool designed for visualizing international collaboration, proved highly effective in the current study for facilitating the visualization of international collaboration (He et al. 2022 ). By organically combining the atlas and the world map, researchers were able to intuitively observe differences in the number of publications across various countries and the extent of national collaboration between different regions.

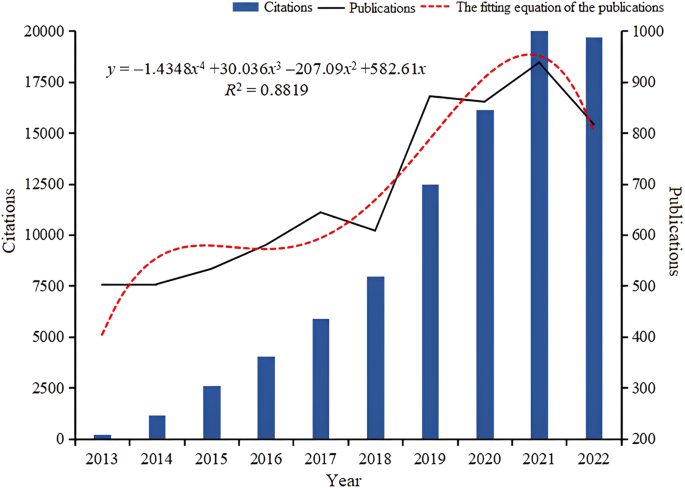

The trend exhibited an upward trajectory, with an estimated 938 publications in 2021, compared to 502 publications in 2013. Notably, the annual publication volume in the field of romantic love had reached its peak in 2021, as indicated by the fitted equation. However, it is worth mentioning that there was a slight decrease in publication numbers during specific periods. From 2017 to 2018, the annual publication count declined from 644 to 608. Similarly, from 2019 to 2020, there was a minor decrease from 872 to 861 publications annually. Additionally, there was a slight decline from 2021 to 2022, with the number of publications decreasing from 938 to 817 annually.

In the previous study, a comprehensive range of factors was considered to provide a thorough and scientifically rigorous atlas analysis of romantic love research. These factors included the annual publication rate, citation counts, H-index, impact factor, centrality, and occurrence/citation burst. An increase in the volume of publications can indicate the growth of a field and provide insights into future research directions (Wang 2016 ). While the number of citations a paper receives may not directly measure an author’s academic influence, it can indicate the recognition of the author’s work by peers worldwide. The “H-index” was a tool for evaluating academic influence, where a researcher with an “H-index” of 10 had 10 papers that had been cited at least 10 times (Wang et al. 2021 ). Since its inception in the 1950s, the impact factor has been widely regarded as a prominent index for ranking scientific literature. It has become an emblem of the prestige and significance of journals and authors in determining the relevance of a journal (Oosthuizen and Fenton 2014 ). For the current study, Journal Citation Reports (JCR) were utilized to calculate impact factors (2021). The centrality of research objects can indeed reflect their impact on the entire field, with greater centrality indicating a greater representation of homologous study content within a subject area. In the study conducted by Gao et al. ( 2021 ), betweenness centrality scores were adjusted to the range of [0, 1]. Specifically, if the betweenness centrality score of a main keyword exceeded 0.10, it was considered to indicate the significance of the study target. In the study conducted by Xu et al. ( 2022 ), the concept of a “burst term” was utilized to refer to an unexpected term that emerged in the research, potentially indicating new directions or orientations discovered during the investigation. The Kleinberg burst detection method, which is implemented in the CiteSpace software, was employed to identify these burst terms and highlight them as indicators of frontier research.

Publication outputs

A total of 6858 records met the search criteria. As depicted in Fig. 2 , the number of annual publications in the field of romantic love has shown a consistent upward trend since 2013. This increase is accompanied by a corresponding surge in citation counts, as indicated by the fitted equation. Citation counts in the field of romantic love have also experienced a significant upsurge since 2013, with an approximate 90-fold increase by 2022. Furthermore, based on current trends and fitting curves, the number of studies in this field is expected to continue rising, with an increasing number of researchers focusing on this topic.

Distribution by journals

The current study retrieved a total of 6858 records from 1251 journals, with ~33.79% of the material published by 20 publications that released more than 50 papers in this field. The top ten journals, accounting for 23.78% (92–400) of all papers published, had an average publication count of 134 papers per journal (see Table 1 ). Among them, the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships (400 publications, IF 2021 = 2.681) had the highest number of papers on romantic love research, followed by Personal Relationships (189 publications, IF 2021 = 1.528), and Personality and Individual Differences (185 publications, IF 2021 = 3.950). Notably, the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology was the most influential professional core journal in this field, boasting the highest impact factor (8.460). Both European and American journals have made significant contributions to this field, with the United States and the United Kingdom accounting for 40% and 50% of the top 10 journal publishing countries/regions, respectively. The impact factors of the top 10 most-published journals ranged from 1.528 to 8.460, with an average of 4.070. It is worth noting that publishing romantic love-related articles in high-impact journals remains challenging.

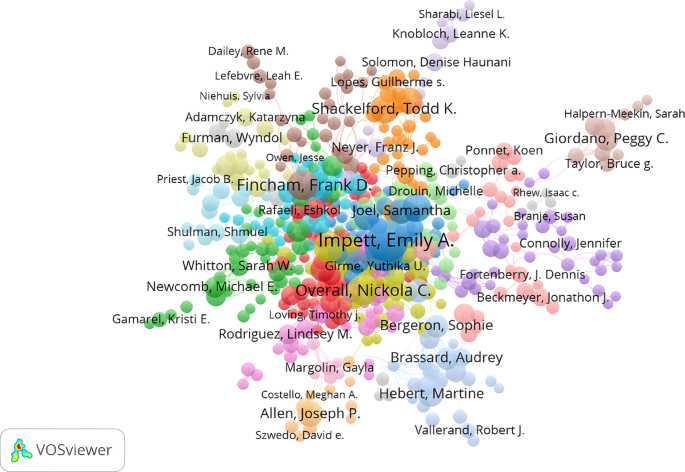

Distribution by authors and research areas

A staggering 15,088 authors contributed to the total number of papers. In Fig. 3 , the collaborative efforts of the writers were illustrated through a network map, where the connections between the nodes signified their collaborative affiliations. Among the top three clusters, the red cluster included authors Joseph P. Allen, Martine Hebert, and Marie-France Lafontaine, who had converged due to their shared research interests in adolescent dating violence and aggression (Cenat et al. 2022 ; Niolon et al. 2015 ). The blue cluster consisted of authors Frank D. Fincham, James K. Monk, and Ashley K. Randall, who had explored the interplay between relationship satisfaction, stress, and relationship maintenance in romantic relationships (Randall and Bodenmann 2017 ; Vennum et al. 2017 ). The yellow cluster included authors Todd K. Shackelford, William J. Chopik, and Justin K. Mogilski, whose work focused on the topic of polygamy (Moors et al. 2019 ; Sela et al. 2017 ). Martine Hebert, Todd K. Shackelford, Frank D. Fincham, and Emily A. Impett emerged as the cooperative network’s central nodes, underscoring their crucial role in advancing research on romantic love.

The authors’ cooperative network was partitioned into eight distinct clusters.

Table 2 provided a rundown of the most productive authors, with their published works ranging from 28 to 74 publications, averaging 41. The H-index, a yardstick for measuring academic influence, was employed to assess their impact. Notably, Emily A. Impett emerged as the dominant force within the cohort of scholars dedicated to the study of romantic love, having authored the most papers among the group (74 publications, H-index = 38). Additionally, Nickola C. Overall (42 publications, H-index = 19) and Amy Muise (60 publications, H-index = 30) also featured prominently as leading contributors to the field.

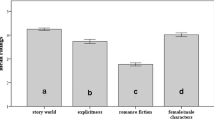

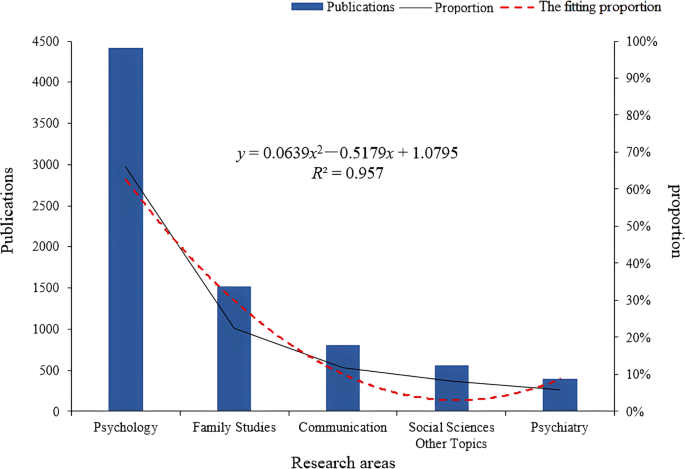

Table 3 and Fig. 4 displayed the number of publications in different fields of study related to the topic of romantic love. Notably, publications in the fields of biology, neuroscience, and economics were also included in Table 3 . The humanities were increasingly collaborating on romantic love research. Furthermore, the topic of romantic love was gaining popularity in the fields of psychology and sociology.

The field of psychology, including psychology and psychiatry, was significantly ahead. The field of sociology encompassed various topics in the social sciences, including sociology and social work.

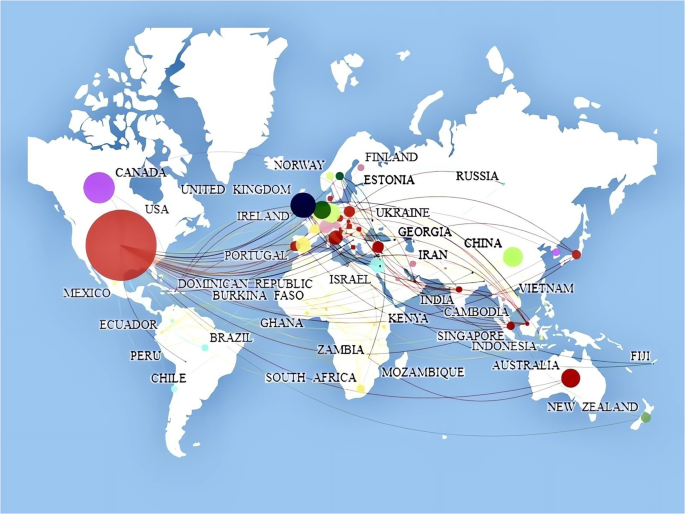

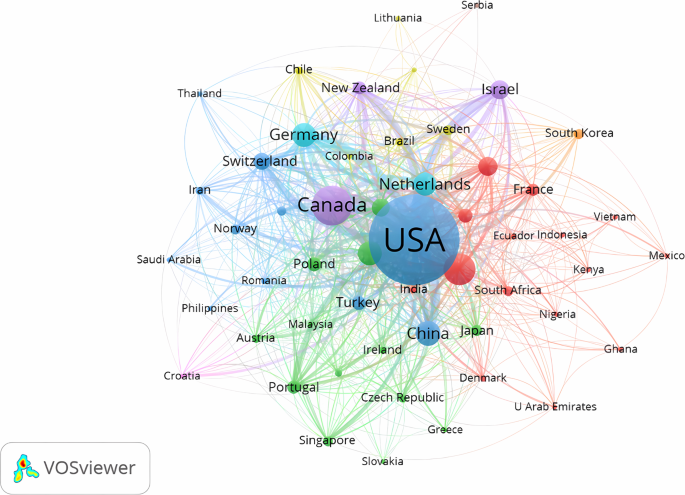

Distribution by country and institution

A total of 6858 publications had been published and disseminated to 104 countries and regions worldwide. In the country analysis, Scimago Graphica had been used to explore the geographic collaboration network of participating nations. The participants of the current study were drawn from 104 different countries spanning Asia, Africa, Europe, North America, and South America, with Europe exhibiting the highest level of overall engagement, underscoring the global trend toward collaboration. The United States and the United Kingdom had demonstrated the greatest degree of cooperation. Notably, China, South Africa, Spain, Italy, France, and other countries with high cooperation densities had formed the most significant multi-center cooperation network in this field (see Fig. 5 ). Figure 6 illustrated international collaboration.

By leveraging Scimago Graphica, it was possible to merge geographical perspectives with national publications and collaborative relationships, providing an intuitive and scientific method to illuminate the various conditions of countries involved in the research on romantic love.

The largest blue cluster was comprised of the United States, China, Switzerland, Turkey, and Norway, demonstrating collaboration across the Americas, Europe, and East Asia.

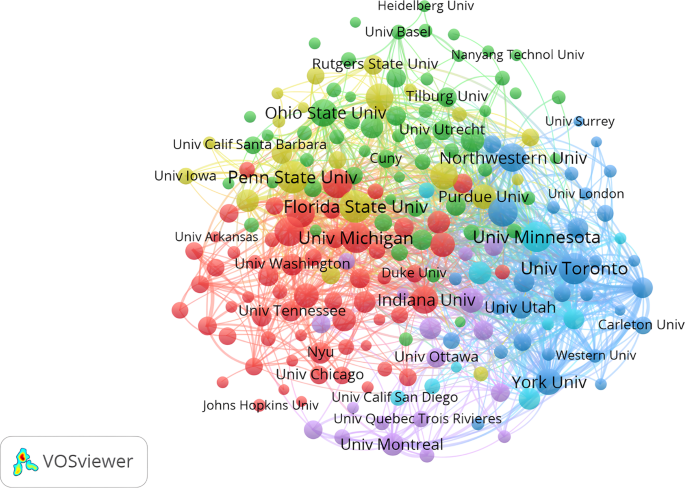

Table 4 outlined the specifics of the top ten countries in the landscape of romantic love research. The United States topped the list with 4092 publications, followed by Canada with 802 publications, and the United Kingdom with 540 publications. It is noteworthy that the majority of publications were disseminated from high-income countries, aligning with the overall prosperity of those nations. Most papers were disseminated in high-income countries. This trend might have stemmed from the overarching principles governing scientific inquiry, or it could be attributed to authors in these nations having the freedom to engage in research spanning areas not necessarily centered on economic growth. However, within the realm of general well-being, this emerges as a pertinent concern. Primarily, high-income countries historically boasted more affluent reservoirs of research resources, encompassing financial backing, cutting-edge equipment, and a pool of adept talent. This affluence empowered researchers in these nations to embark on a diverse array of investigations, spanning domains intricately tied to economic growth and extending to those delving into broader realms such as general well-being and social development. The discernible divergence in resource allocation likely contributed to the disproportionate prevalence of publications in high-income countries. Secondarily, the scrutiny of whether the romantic love research domain intricately correlates with economic growth warrants profound contemplation. At times, the merit of research doesn’t solely reside in its potential to spur short-term economic growth but extends to its impact on the overarching well-being and sustainable evolution of society. High-income countries, historically oriented toward prioritizing protracted social well-being, manifested a proclivity to endorse research that, while not directly contributing to economic growth, played an indispensable role in the comprehensive development of society. Institutional collaboration was vividly portrayed in Fig. 7 , which consisted of six clusters. A total of 3328 institutions contributed to the 6858 articles on romantic love. Of the top 10 organizations, universities occupied the top spot (as indicated in Table 5 ), with the State University System of Florida (246 publications), the University System of Ohio (248 publications), and the University of California System (365 publications) leading the pack. Notably, nine out of the top 10 institutions hailed from the United States, which was a testament to the country’s exceptional research prowess in this field.

The red cluster denoted collaboration among Florida State University, University of Michigan, University of Washington, and Indiana University; the green cluster represented Ohio State University, University of Basel, and Nanyang Technological University; while the blue cluster embodied York University, the University of Toronto, Northwestern University, and Carleton University. Northwestern University, Florida State University, the University of Minnesota, and the University of Toronto were the major nodes in the cooperative network.

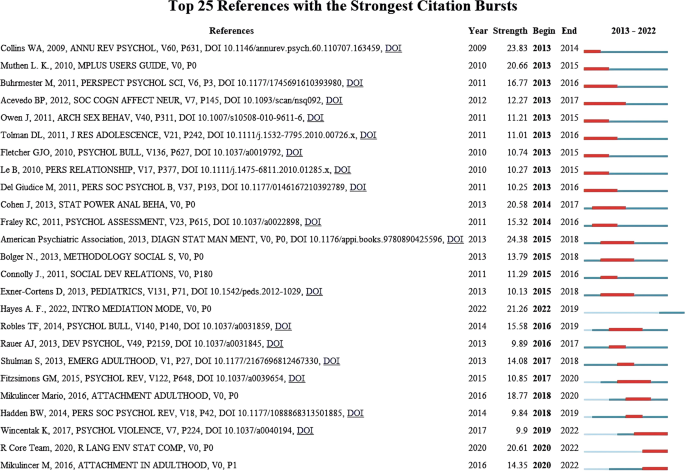

Analysis of references

Reference analysis played a critical role in bibliometric research, as the references with the highest citation bursts formed the foundation of knowledge at the forefront of research (Fitzpatrick 2005 ). In Fig. 8 , the current study presented the most relevant references on romantic love, which had experienced a surge in citations over the past decade. By the end of 2022, Mikulincer and Shaver’s ( 2016 ) articles had seen a significant increase in their citation counts, with the highest spike (14.35) observed in 2016, followed by Wincentak et al.’s ( 2017 ) studies (9.9). These two studies had been widely cited over the years and accurately captured the latest trends in romantic love research.

These references were represented by red and green bars, indicating their frequent and less frequent citation, respectively.

Mikulincer and Shaver’s ( 2016 ) delved into the causes and methods for measuring individual differences in adult attachment, as well as how to modify attachment styles, using several empirical studies. Additionally, they explored the cutting-edge genetics, neurological, and hormonal substrates of attachment, expanding the impact model’s depiction of how the attachment system functioned. In the study, Wincentak et al. ( 2017 ) discussed the prevalence of dating violence among adolescents of different genders using a meta-analysis method, while also examining the potential regulatory effects of age, demographics, and measurement. Research has shown that in adolescent dating violence, the crime rate of women was significantly lower than that of men. Based on the analysis of these articles, current research trends in romantic love included adult attachment and the examination of adolescents’ irrational beliefs about love and the resulting adverse consequences, such as dating violence.

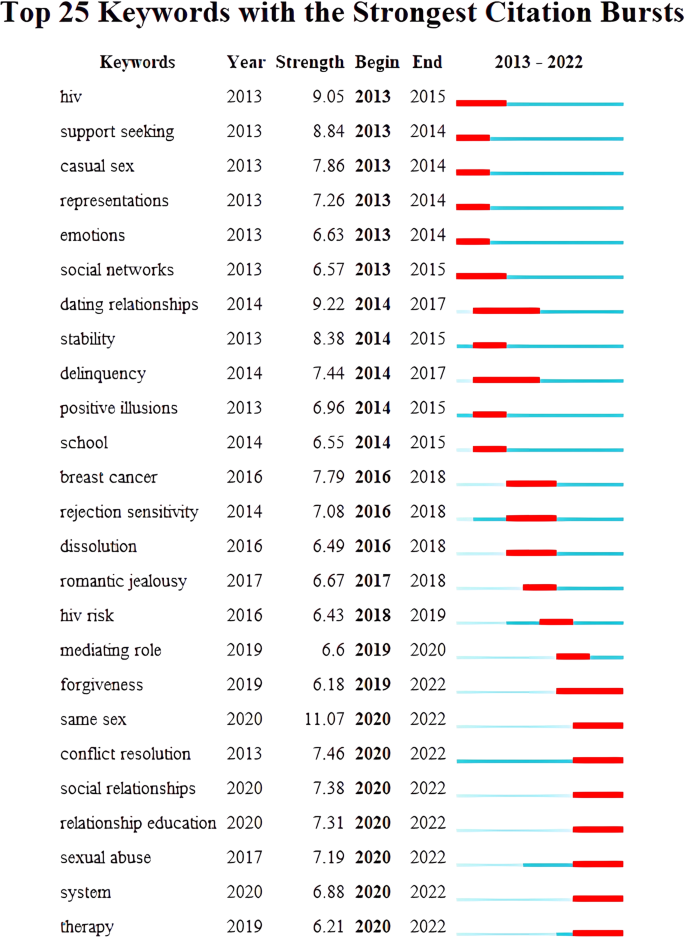

Analysis of keywords

Keyword burst refers to keywords that have shown a sharp increase in frequency over time, enabling the assessment of the current study focus in this area and reflecting the development pattern of future research. The current study extracted the burst terms of various years in the area of romantic love to obtain the burst terms of various years in the area of romantic love (see Fig. 9 ). As we’ve seen, the field had a diverse range of research interests. By the end of 2022, the three words with the highest peak were “same-sex” (2020–2022), “conflict resolution” (2020–2022), and “social relationships” (2020–2022):

Same-sex: in a society that valued heterosexual relationships, same-sex relationships were often met with shame and stigma, leading to additional pressures uniquely linked to their sexual orientation and partnership (Feinstein et al. 2018 ; Rostosky and Riggle 2017 ). Moreover, the online conduct of gay individuals has been demonstrated to have significant implications for their sexual risk behaviors and emotional well-being in romantic relationships (Zhang et al. 2022b ). The development of effective dual interventions has been shown to enhance the health and well-being of same-sex couples and their families. These interventions should also educate parents about the potential negative effects of heteronormative assumptions and attitudes on their children’s positive adolescent development (Pearson and Wilkinson 2013 ).

Conflict resolution: previous research has shown the irony that a person’s favorite individual, such as their romantic partner, is often the very person with whom they engage in destructive behavior during conflicts, making this destructive response one of the most challenging issues in relationships (Alonso-Ferres et al. 2021 ). As a result, it was critical to effectively resolve conflicts in a constructive manner. The emergence of computer-mediated communication (CMC) as a novel conflict resolution approach prompted researchers to explore this matter. Ultimately, they discovered that there were no differences in pain, anger, and conflict resolution levels between face-to-face and CMC discussions (Pollmann et al. 2020 ). Another study focused on neural activity during conflict resolution, revealing that mediation could enhance conflict resolution and was linked to increased activity in the nucleus accumbens, a crucial area of the brain’s reward circuit (Rafi et al. 2020 ). The finding emphasizes the importance of identifying neural mechanisms that could enhance conflict resolution and improve relationship outcomes. By exploring various conflict resolution approaches and associated neural mechanisms, researchers can facilitate a deeper understanding of how to successfully resolve conflicts and enhance relationship satisfaction.

Social relationships: long-term relationships are vital to the mental health of both humans and animals. Positive emotions and experiences, such as romantic or platonic love, play a significant role in the establishment and maintenance of social bonds. With this in mind, researchers integrated brain imaging studies on emotions characterized by social connections to investigate whether and how humans and animals experience social emotions and influences similarly in the context of social relationships (Zablocki-Thomas et al. 2022 ). An ecological and cross-cutting perspective study found that black Americans viewed their partner’s interactions regarding discrimination as an opportunity for their romantic partner to offer support, as revealed in semi-structured interviews (Rice 2023 ). Furthermore, as romantic relationships represent one of the most unique types of social connections, researchers utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning techniques to explore the neurobiological mechanisms of romantic relationships (Eckstein et al. 2023 ), offering valuable insight for the preservation and maintenance of social relationships and interactions.

Over the last 10 years, the most popular keywords were “same-sex” (11.07), “dating relationships” (9.22), and “HIV” (9.05), indicating high demand for these topics in recent years. The keywords with the longest blasting times were “dating relationships” (2014–2017) and “delinquency” (2014–2017). The phrases that were still trending in 2022 were hotspots.

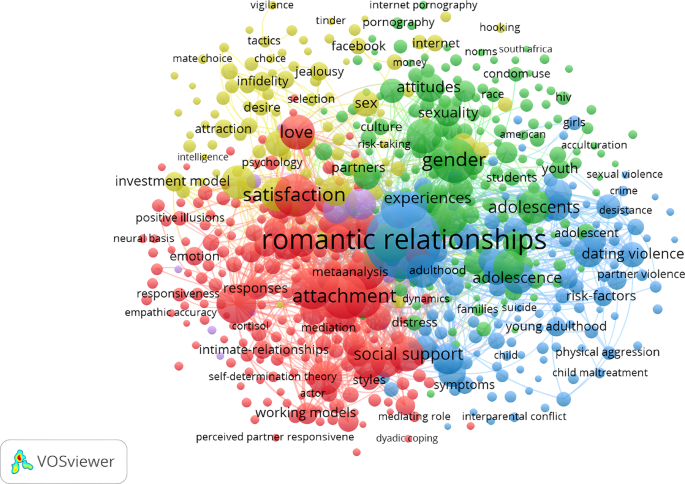

Figure 10 illustrated the relationship between keywords. The connection strength between two nodes was a quantitative measure of their relationship. The most frequently used keyword, “romantic relationship,” was represented by the largest node in Fig. 10 (see Table 6 ). The “romantic relationship” (2036) node had thicker lines than “attachment” (766), “gender” (728), “satisfaction” (664), “behavior” (529), “marriage” (508), “commitment” (419), “adolescents” (417), “associations” (395), and “intimate partner relationship” (336). The nodes had a minimum link strength of 150. The close connections between “romantic relationship” and “marriage,” “commitment,” and “intimate partnership” demonstrated the importance of stable, long-term relationships in maintaining romantic love (Fu et al. 2012 ).

The connection strength between two nodes was a quantitative measure of their relationship. The total link strength of a node was the sum of its link strengths relative to all other nodes (Liao et al. 2018).

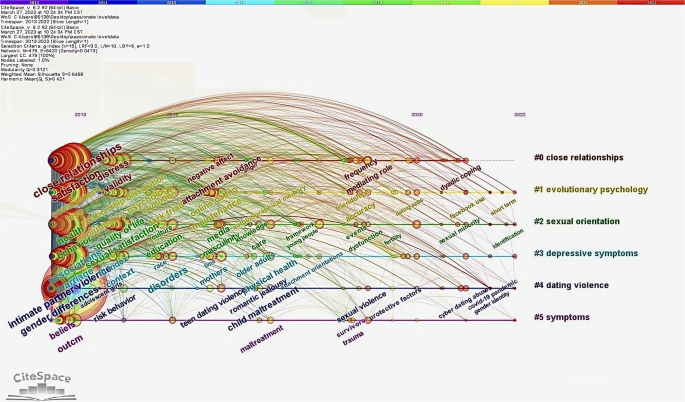

Keywords are essential in identifying the central themes and prospective avenues of a publication. By examining the co-occurrence of keywords, one can discern the current trajectory of research and development in a specific field (Zhang et al. 2022c ). In the present investigation, a total of 16,148 keywords were extracted from 6858 articles related to romantic love, with 10,571 being used only once, accounting for 65.46% of the total keywords. Through keyword co-occurrence analysis, six distinct color-coded clusters were identified, comprising attachment, gender, romantic relationships, personality, communication, and dynamics. The red cluster, attachment, delved into the complex relationships among commitment, fulfillment, companionship, and attachment insecurity. To address the diminished satisfaction in partner relationships caused by attachment insecurity, promoting healthy dualistic coping strategies (DCS) was recommended (Peloquin et al. 2022 ). The green cluster, gender, focused on the issues of dating violence victimization experienced by young individuals of different genders, with sexual minorities being particularly vulnerable to bullying (Cosma et al. 2022 ). The blue cluster, romantic connections, primarily examined the link between depressive symptoms and violent intimate partner relationships. Recent studies showed that dating violence and peer victimization were prevalent among young individuals (Smith et al. 2021 ) and that dating aggression was associated with both internalized and externalized psychopathology in young couples (Lantagne and Furman 2021 ). Additionally, the misuse of internet dating may lead to depression (Toplu-Demirtas et al. 2020 ). Apart from the six clusters mentioned, there was a noticeable trend toward integrating research with neuroimaging technology, which might lead to the emergence of new clusters in the realm of romantic love. The interconnectedness of attachment, gender, and romantic relationships was evident in the strong theoretical foundation and widespread attention these clusters received, whereas the clusters of personality, communication, and dynamics were more peripherally related. Due to their significance, future research on romantic love will continue to explore topics such as intimate partner violence, teenage dating violence victimization, attachment insecurity, and sexual abuse, with a focus on the three interconnected clusters of attachment, gender, and romantic relationships. In traditional notions, our understanding of romantic love had primarily consisted of terms such as romantic relationships and intimate commitments. However, practical issues such as misperceptions about love and a lack of regard for partners have gradually shifted the subject matter of research pertaining to romantic love toward dating violence. The research trajectory demonstrates a shift in the focus of romantic love research from a more idealized perspective toward a more realistic one. Finally, Fig. 11 displayed a keyword timeline graph that depicted when the most prevalent keywords first appeared and their evolving importance over time.

This keyword timeline graph was depicted when the most prevalent keywords first appeared and their evolving importance over time.

The current study used advanced bibliometrics and literature data visualization techniques with CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and Web of Science to examine the growth of research publications in the field of romantic love, as well as the main research nations, journals, and emerging trends. The thorough review provided insight into the present status of development and research in this field, while also clarifying the historical path of scholarship and providing clear guidance for future research. Using bibliometric methods, the study investigated romantic love research from 2013 to 2022. The results showed a steady increase in publications on this topic, with a slight decrease noted in 2019, likely due to the detrimental impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic research. However, the analysis of current trends indicates a projected increase in research output on romantic love in the coming years.

Romantic love has been a global phenomenon, with Europe and the United States leading in widespread participation and clear concentration. Among the top 10 countries producing research in this field, the United States led with 4092 publications between 2013 and 2022. China, ranking fourth in terms of publications, emerged as the most prolific developing nation (328). However, compared to the United States, China lagged behind in publications and international collaboration. Therefore, China needs to expand its research efforts in this area and broaden its international partnerships. The top ten research institutions, mainly universities, played a vital role in advancing this field. Notably, nine out of ten of these institutions were located in the United States, further highlighting the preeminent position of American academic institutions in this area of study.

In the current study, we have discovered noteworthy findings regarding notable authors in the field of romantic love. The research studies have primarily focused on four distinct perspectives: the Limerence Theory, the Rate of Change in Intimacy Model, the Self-Expansion Model, and the Triangular Theory of Love. These perspectives have proposed four possible sources of romantic passion and assessed empirical evidence for and against each. Among the authors, Emily A. Impett has emerged as the most prolific author (Carswell and Impett 2021 ). Frank D. Fincham, who has the highest H-index, has conducted extensive research on the interplay between mindfulness and idiosyncratic mindfulness in romantic relationships. Notably, his research on adolescent intimate partner violence has received the most citations (Cui et al. 2013 ; Frank and Ross 2017 ; Kimmes et al. 2018 ). Furthermore, we found that an author’s centrality and citation frequency did not always correlate with their number of publications, indicating that various factors had contributed to an author’s academic influence (Zhang et al. 2022a ).

The term “burst term” refers to a term that unexpectedly appears in research and may indicate new directions or a novel perspective derived from research (Xu et al. 2022 ). According to Fig. 8 , the following references experienced a citation burst by the end of 2022: (1) Mikulincer and Shaver ( 2016 ) delved into the causes and measures of individual differences in adult attachment, explored the modifiability of attachment styles, and unveiled cutting-edge research in genetics, neurology, and hormones associated with attachment. They also extended the impact model’s depiction of the attachment system’s operation. (2) Wincentak et al. ( 2017 ) conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the prevalence of dating violence among adolescents of various genders, while also examining the potential impact of age, demographic factors, and measurement methods. Their findings suggested that the rate of perpetration of dating violence was significantly higher among male adolescents than female adolescents. In other words, male adolescents were more likely to engage in dating violence than their female counterparts. This gender difference in dating violence rates highlighted the need for targeted prevention and intervention efforts to address this issue among young people.

CiteSpace displayed keywords in bursts, as shown in Fig. 9 . These data were significant for reference in cutting-edge prediction research. The terms “same-sex,” “conflict resolution,” and “social relationships” might be used frequently in the coming years, indicating potential areas of focus within the domain of romantic love:

Same-sex: same-sex relationships faced unique pressures and stigma in a society that largely valued heterosexual partnerships, leading to feelings of shame and additional stressors based on sexual orientation (Feinstein et al. 2018 ; Rostosky and Riggle 2017 ). Notably, studies have revealed that the online behavior of gay individuals could significantly impact their emotional well-being and sexual risk behaviors within their romantic relationships (Zhang et al. 2022b ). To improve the health and well-being of same-sex couples and their families, effective dual interventions have been developed, including educating parents about the potential harm caused by heteronormative assumptions and attitudes on their children’s adolescent development (Pearson and Wilkinson 2013 ).

Conflict resolution: prior research has revealed the paradox that a person’s beloved partner, such as their significant other, is often the individual with whom they engage in harmful behavior during conflicts. The negative reaction could be one of the most challenging issues in a relationship (Alonso-Ferres et al. 2021 ). Therefore, it is imperative to resolve conflicts in a successful manner. Computer-mediated communication (CMC) has emerged as a novel approach to conflict resolution, and researchers have investigated this matter, concluding that there are no disparities in the levels of pain, anger, and conflict resolution between face-to-face and CMC discussions (Pollmann et al. 2020 ). Another study explored the neural mechanisms during conflict resolution, and researchers discovered that mediation could improve conflict resolution and was linked to elevated activity in the nucleus accumbens, a crucial area in the brain’s reward circuit (Rafi et al. 2020 ).

Social relationships: long-term relationships play a critical role in maintaining the mental health of both humans and animals. Positive emotions and emotional experiences, such as romantic or platonic love, are intricately linked to the formation and sustenance of social bonds. To gain insights into how social emotions manifest in both humans and animals, researchers integrated brain imaging studies of emotions associated with social connections (Zablocki-Thomas et al. 2022 ). From an ecological and cross-cutting perspective, another study found that Black Americans viewed their partner’s interactions around discrimination as an opportunity for their romantic partner to provide support, as revealed in semi-structured interviews (Rice 2023 ). Furthermore, given the unique nature of romantic relationships in social interactions, researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) techniques to investigate the neurobiological mechanisms of such relationships (Eckstein et al. 2023 ), which could serve as a reference for the preservation and cultivation of social relationships.

To our knowledge, our study represented a novel application of quantitative bibliometric tools such as CiteSpace and VOSviewer to analyze the literature on romantic love over the past decade. While our analysis yielded intriguing insights into the research landscape of this field, our study was not without limitations. First and foremost, our sample was limited to articles and reviews available in a single database, and thus, may not have been fully representative of the entire research landscape on this topic. Second, the current study restricted our data collection to English-language publications, and future studies may benefit from including publications in other languages to ensure a more comprehensive analysis. Additionally, including different types of publications, such as conference papers and working papers, might have provided further insights into recent advancements in the field. Furthermore, it could be acknowledged that the analysis in the current study could be expanded to consider the contributions of other scholars and institutions in the field, beyond those captured by our data set. Finally, while the bibliometric tools used in our analysis were objective, our interpretation of the results remained subjective and may have been subject to varying interpretations.

Concluding remarks

Research significance and future development.

The present study’s comprehensive analysis of the literature on romantic love, as well as its reporting of research findings across diverse domains over the past decade, offered a solid groundwork for future research and potential worldwide applications. From 2013 to 2022, a staggering 6858 articles and reviews on romantic love were published globally, indicating a bright future for this field of inquiry. In terms of research potency, the United States led the pack, with the University of California System accounting for the majority of publications in the area of romantic love, and Emily A. Impett ranking as the most prolific contributor. The Journal of Social and Personal Relationships had published the most articles on romantic love research, while the most recent trends in romantic love-related keywords included “same-sex,” “conflict resolution,” and “social relationships.” The current research was predominantly centered around intimate relationships, evolutionary psychology, sexual orientation, and symptoms of depression. The trends elucidated by these findings underscore the holistic and interdisciplinary nature of romantic love within the realms of psychology, sociology, biology, and neuroscience. Subsequent investigations into romantic love hold the promise of a more profound amalgamation of methodologies derived from psychology and neuroscience, thereby illuminating the physiological underpinnings of love and emotional experiences. This prospect entails a meticulous exploration of brain activity, probing how intricate psychological processes intertwine with biology to forge the intricacies of romantic relationships. Furthermore, romantic love research stands poised to cultivate seamless integration and interdisciplinary cooperation across a spectrum of fields in the future, yielding profound ramifications.

Method limitation

The current study, which utilized tools such as CiteSpace and Vosviewer for a quantitative analysis of the literature on romantic love over the past 10 years, is the first of its kind to our knowledge. Our investigation, though producing intriguing results through bibliometric analysis and visualization of related articles, is not without its limitations. Firstly, the samples utilized were limited to a single database (WOS), which may not encompass all relevant publications on the subject. Secondly, the scope of our data collection was limited to articles and reviews in English only, leaving out potential information from other types of publications such as working papers and conference papers. In future studies, a broader consideration of different languages should also be given. Additionally, the neural mechanism and physiological function of romantic love remain an under-researched area with limited empirical evidence to support ongoing controversy.

Data availability

Original data for the current study are available via this link: https://rec.ustc.edu.cn/share/0d874150-b039-11ee-be97-f5a41b2eeb6e .

Acevedo BP, Aron A, Fisher HE, Brown LL (2012) Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 7(2):145–159

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Acevedo BP, Poulin MJ, Collins NL, Brown LL (2020) After the honeymoon: neural and genetic correlates of romantic love in newlywed marriages. Front Psychiatry 11:634

Article Google Scholar

Alirezanejad S (2022) Becoming a wife, a beloved, or both: caught in feminine struggle in Tehran. Sex Cult 26(3):811–833

Alonso-Ferres M, Valor-Segura I, Expósito F (2021) Elucidating the effect of perceived power on destructive responses during romantic conflicts. Span J Psychol 24:e21

Aron A, Fisher H, Mashek DJ, Strong G, Li H, Brown LL (2005) Reward, motivation, and emotion systems associated with early-stage intense romantic love. J Neurophysiol 94(1):327–337

Bartels A, Zeki S (2000) The neural basis of romantic love. NeuroReport 11(17):3829–3834

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bartels A, Zeki S (2004) The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love. NeuroImage 21(3):1155–1166

Budziszewska MD, Babiuch-Hall M, Wielebska K (2020) Love and romantic relationships in the voices of patients who experience psychosis: an interpretive phenomenological analysis. Front Psychol 11:570928

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Carswell KL, Impett EA (2021) What fuels passion? An integrative review of competing theories of romantic passion. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 15(8):e12629

Cenat JM, Mukunzi JN, Amedee LM, Clormeus LA, Dalexis RD, Lafontaine MF, Hebert M (2022) Prevalence and factors related to dating violence victimization and perpetration among a representative sample of adolescents and young adults in Haiti. Child Abus Negl 128(3):105597

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017) Key statistics from the National Survey of Family Growth—D Listing. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/key_statistics/d.htm#divorce

Chester DS, Martelli AM, West SJ, Lasko EN, Brosnan P, Makhanova A, McNulty JK (2021) Neural mechanisms of intimate partner aggression. Biol Psychol 165:108195

Cosma A, Kolto A, Young H, Thorsteinsson E, Godeau E, Saewyc E, Gabhainn SN (2022) Romantic love and involvement in bullying and cyberbullying in 15-year-old adolescents from eight European countries and regions. J LGBT Youth 20(1):33–54

Cui M, Gordon M, Ueno K, Fincham FD (2013) The continuation of intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. J Marriage Fam 75(2):300–313

Daim TU, Rueda G, Martin H, Gerdsri P (2006) Forecasting emerging technologies: use of bibliometrics and patent analysis. Technol Forecast Soc Change 73(8):981–1012

Eckstein M, Stossel G, Gerchen MF, Bilek E, Kirsch P, Ditzen B (2023) Neural responses to instructed positive couple interaction: an fMRI study on compliment sharing. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 18(1):nsad005

Ellegaard O, Wallin JA (2015) The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: how great is the impact? Scientometrics 105(3):1809–1831

Feinstein BA, McConnell E, Dyar C, Mustanski B, Newcomb ME (2018) Minority stress and relationship functioning among young male same-sex couples: an examination of actor–partner interdependence models. J Consult Clin Psychol 86(5):416–426

Fehr B (2013) The social psychology of love. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L (eds.) The Oxford handbook of close relationships. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 201–233

Google Scholar

Fehr B (2015) Love: conceptualization and experience. In: Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Simpson JA, Dovidio JF (eds.) APA handbook of personality and social psychology, vol 3 interpersonal relations. American Psychological Association, Washington, p 495–522

Chapter Google Scholar

Fisher HE, Brown LL, Aron A, Strong G, Mashek D (2010) Reward, addiction, and emotion regulation systems associated with rejection in love. J Neurophysiol 104(1):51–60

Fitzpatrick RB (2005) Essential science indicators. Med Ref Serv Q 24(4):67–78

Fletcher GJ, Simpson JA, Campbell L, Overall NC (2015) Pair-bonding, romantic love, and evolution: the curious case of homo sapiens. Perspect Psychol Sci 10(1):20–36

Frank DF, Ross WM (2017) Infidelity in romantic relationships. Curr Opin Psychol 13:70–74

Fu Y, Zhou Y, Liang ZY, Li S (2012) New insights into the neurophysiological mechanism of romantic love. Chin Sci Bull 57(35):3376–3383

Gao C, Wang R, Zhang L, Yue CW (2021) Visualization analysis of CRISPR gene-editing knowledge map based on Citespace. Biol Bull 48(6):705–720

Hatfield E, Rapson RL (1987) Passionate love/sexual desire: can the same paradigm explain both? Arch Sex Behav 16(3):259–278

He TM, Ao JW, Duan CC, Yan R, Li XM, Liu L, Li XF (2022) Bibliometric and visual analysis of nephrotoxicity research worldwide. Front Pharmacol 13:940791

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hou ZM, Jiang P, Su ST, Zhou HH (2022) Hotspots and trends in multiple myeloma bone diseases: a bibliometric visualization analysis. Front Pharmacol 13:1003228

Jimenez-Picon N, Romero-Martin M, Romero-Castillo R, Palomo-Lara JC, Alonso-Ruiz M (2022) Internalization of the romantic love myths as a risk factor for gender violence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Res Soc Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-022-00747-2

Kerr S, Penner F, Ilagan G, Choi‑Kain L, Sharp C (2022) Maternal interpersonal problems and attachment security in adolescent offspring. Borderline Pers Disord Emot Dysregulation 9(1):18

Kimmes JG, Jaurequi ME, May RW, Srivastava S, Fincham FD (2018) Mindfulness in the context of romantic relationships: initial development and validation of the relationship mindfulness measure. J Marital Fam Ther 44(4):575–589

Lafontaine MF, Azzi S, Bell-Lee B, Dixon-Luinenburg T, Guérin-Marion C, Bureau JF (2020) Romantic perfectionism and perceived conflict mediate the link between insecure romantic attachment and intimate partner violence in undergraduate students. J Fam Violence 36(2):195–208

Langeslag SJE (2022) Electrophysiological correlates of romantic love: a review of EEG and ERP studies with beloved-related stimuli. Brain Sci 12(5):551

Lantagne A, Furman W (2021) A dyadic perspective on psychopathology and young adult physical dating aggression. Psychol Violence 11(6):569–579

Li Y, Wagner B, Guo G (2022) Romantic partnerships and criminal offending: examining the roles of premarital cohabitation, serial cohabitation, and gender. Justice Q. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2022.2118618

Liao HC, Tang M, Luo L, Li CY, Chiclana F, Zeng XJ (2018) A bibliometric analysis and visualization of medical big data research. Sustainability 10(1):166

Lonergan M, Saumier D, Pigeon S, Etienne PE, Brunet A (2022) Treatment of adjustment disorder stemming from romantic betrayal using memory reactivation under propranolol: a open-label interrupted time series trial. J Affect Disord 317:98–106

Merritt OA, Rowa K, Purdon CL (2022) Context matters: criticism and accommodation by close others associated with treatment attitudes in those with anxiety. Behav Cogn Psychother 51(1):1–11

Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2016) Attachment in adulthood: structure, dynamics, and change, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Mizrahi M, Lemay EP, Maniaci MR, Reis HT (2022) Seeds of love: positivity bias mediates between passionate love and prorelationship behavior in romantic couples. J Soc Personal Relatsh 39(7):2207–2227

Moors AC, Ryan W, Chopik WJ (2019) Multiple loves: the effects of attachment with multiple concurrent romantic partners on relational functioning. Personal Individ Differ 147:102–110

Niolon PH, Kuperminc GP, Allen JP (2015) Autonomy and relatedness in mother-teen interactions as predictors of involvement in adolescent dating aggression. Psychol Violence 5(2):133–143

Oosthuizen JC, Fenton JE (2014) Alternatives to the impact factor. Surgeon 12(5):239–243

Pearson J, Wilkinson L (2013) Family relationships and adolescent well-being: are families equally protective for same-sex attracted youth? J Youth Adolescence 42(9):1494–1496

Peloquin K, Boucher S, Benoit Z, Jean M, Beauvilliers L, Carranza-Mamane B, Brassard A (2022) “We’re in this together”: attachment insecurities, dyadic coping strategies, and relationship satisfaction in couples involved in medically assisted reproduction. J Marital Fam Ther 49(1):92–110

Pollmann MMH, Crockett EE, Vanden Abeele MMP, Schouten AP (2020) Does attachment style moderate the effect of computer-mediated versus face-to-face conflict discussions? Pers Relatsh 27(1):939–955

Quintard V, Jouffe S, Hommel B, Bouquet CA (2021) Embodied self-other overlap in romantic love: a review and integrative perspective. Psychol Res 85(3):899–914

Rafi H, Bogacz F, Sander D, Klimecki O (2020) Impact of couple conflict and mediation on how romantic partners are seen: an fMRI study. Cortex 130:302–317

Randall AK, Bodenmann G (2017) Stress and its associations with relationship satisfaction. Curr Opin Psychol 13:96–106

Reis HT, Aron A, Clark MS, Finkel EJ (2013) Ellen Berscheid, Elaine Hatfield, and the emergence of relationship science. Perspect Psychol Sci 8(5):558–572

Rice TM (2023) Echoes of slavery: reflections on contemporary racial discrimination in Black Americans’ romantic relationships. J Soc Pers Relat. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075231154934

Rostosky SS, Riggle ED (2017) Same-sex relationships and minority stress. Curr Opin Psychol 13:29–38

Sela Y, Mogilski JK, Shackelford TK, Zeigler-Hill V, Fink B (2017) Mate value discrepancy and mate retention behaviors of self and partner. J Personal 85(5):730–740

Smith K, Hebert M, Brendgen M, Blais M (2021) The mediating role of internalizing problems between peer victimization and dating violence victimization: a test of the stress generation hypothesis. J Interpers Violence 37(1):13–14

Sorokowski P, Sorokowska A, Schmehl S et al. (2021) Universality of the triangular theory of love: adaptation and psychometric properties of the Triangular Love Scale in 25 countries. J Sex Res 58(1):106–115

Tobore TO (2020) Towards a comprehensive theory of love: the quadruple theory. Front Psychol 11:862

Toplu-Demirtas E, May RW, Seibert GS, Fincham FD (2020) Does cyber dating abuse victimization increase depressive symptoms or vice versa? J Interpers Violence 37(2):1–17

Vennum A, Monk JK, Pasley BK, Fincham FD (2017) Emerging adult relationship transitions as opportune times for tailored interventions. Emerg Adulthood 5(4):293–305

Wang LF, Liu XN, Zhang K, Liu ZC, Yi Q, Jiang J, Xia YY (2021) A bibliometric analysis and review of recent researches on Piezo (2010–2020). Channels 15(1):310–321

Wang ZM (2016) Comparative analysis of research hotspots of related data at home and abroad. Knowl Manag Forum 1(3):163–173

William WH, Concepción SW (2001) The literature of bibliometrics, scientometrics, and informetrics. Scientomerics 52(2):291–314

Wincentak K, Connolly J, Card N (2017) Teen dating violence: a meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychol Violence 7(2):224–241

Xu ZP, Shao TJ, Dong ZB, Li SL (2022) Research progress of heavy metals in desert-visual analysis based on CiteSpace. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(29):43648–43661

Article CAS Google Scholar

Zablocki-Thomas PB, Rogers FD, Bales KL (2022) Neuroimaging of human and non-human animal emotion and affect in the context of social relationships. Front Behav Neurosci 16:994504

Zagefka H (2022) Lay beliefs about the possibility of finding enduring love: a mediator of the effect of parental relationship quality on own romantic relationship quality. Am J Fam Ther. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2022.2084797

Zeevi L, Selle NK, Kellmann EL, Boiman G, Hart Y, Atzil S (2022) Bio‑behavioral synchrony is a potential mechanism for mate selection in humans. Sci Rep 12(1):4786

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhang AD, Reynolds NR, Huang CM, Tan SM, Yang GL, Yan J (2022b) The process of contemporary gay identity development in China: the influence of internet use. Front Public Health 10:954674

Zhang F, Ye J, Bai Y, Wang H, Wang W (2022c) Exercise-based renal rehabilitation: a bibliometric analysis from 1969 to 2021. Front Med 9:842919

Article ADS Google Scholar

Zhang SY, Wang S, Liu RL, Dong H, Zhang XH, Tai XT (2022a) A bibliometric analysis of research trends of artificial intelligence in the treatment of autistic spectrum disorders. Front Psychiatry 13:967074

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Starting Fund for Scientific Research of High-Level Talents at Anhui Agricultural University (rc432206) and the Outstanding Youth Program of Philosophy and Social Sciences in Anhui Province (2022AH030089) to SL.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, 230036, Anhui, China

Yixue Han, Yulin Luo, Zhuohong Chen, Nan Gao, Yangyang Song & Shen Liu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SL worked toward conceptualization, validation, supervision, foundation, and editing. YH worked toward methodology, writing, and formal analysis. YL, ZC, NG, and YS worked toward writing, validation, and formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shen Liu .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the current study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required as the current study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions