Diego Rivera

(1886-1957)

Who Was Diego Rivera?

Now thought to be one of the leading artists of the 20th century, Diego Rivera sought to make art that reflected the lives of the Mexican people. In 1921, through a government program, he started a series of murals in public buildings. Some were controversial; his Man at the Crossroads in New York City's RCA building, which featured a portrait of Vladmir Lenin, was stopped and destroyed by the Rockefeller family.

Rivera was born on December 8, 1886, in Guanajuato, Mexico. His passion for art emerged early on. He began drawing as a child. Around the age of 10, Rivera went to study art at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts in Mexico City. One of his early influences was artist José Posada who ran a print shop near Rivera's school.

In 1907, Rivera traveled to Europe to further his art studies. There, he befriended many leading artists of the day, including Pablo Picasso. Rivera was also able to view influential works by Paul Gaugin and Henri Matisse, among others.

Famous Muralist

Rivera had some success as a Cubist painter in Europe, but the course of world events would strongly change the style and subject of his work. Inspired by the political ideals of the Mexican Revolution (1914-15) and the Russian Revolution (1917), Rivera wanted to make art that reflected the lives of the working class and native peoples of Mexico. He developed an interest in making murals during a trip to Italy, finding inspiration in the Renaissance frescos there.

Returning to Mexico, Rivera began to express his artistic ideas about Mexico. He received funding from the government to create a series of murals about the country's people and its history on the walls of public buildings. In 1922, Rivera completed the first of the murals at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria in Mexico City.

Commercial Success

In the 1930s and '40s, Rivera painted several murals in the United States. Some of his works created controversy, especially the one he did for the Rockefeller family in the RCA building in New York City. The mural, known as "Man at the Crossroads," featured a portrait of Russian Communist leader Vladimir Lenin. The artist had reportedly included Lenin in his piece to portray the turbulent political atmosphere at the time, which was largely defined by conflicting capitalist and socialist ideologies and escalating fears surrounding the Communist Party. The Rockefellers disliked Rivera's insertion of Lenin and, thusly, asked Rivera to remove the portrait, but the painter refused. The Rockefellers then had Rivera stop work on the mural.

In 1934, Nelson Rockefeller famously ordered the demolition of "Man at the Crossroads." Publish backlash against the Rockefellers ensued; after long proclaiming a deep dedication to the arts, the powerful family now looked both hypocritical and tyrannical. John D. Rockefeller Jr. later attempted to explain the destruction of the mural, stating, "The picture was obscene and, in the judgment of Rockefeller Center, an offense to good taste. It was for this reason primarily that Rockefeller Center decided to destroy it."

Later Life and Work

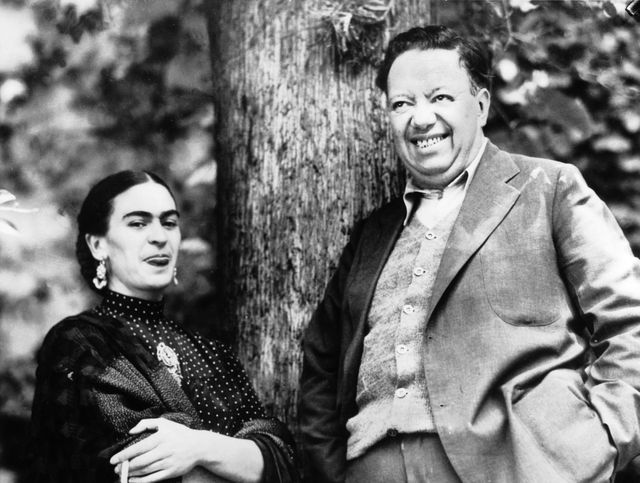

In the late 1930s, Rivera went through a slow period, in terms of work. He had no major mural commissions around this time so he devoted himself to painting other works. While they always had a stormy relationship, Rivera and Kahlo decided to divorce in 1939. But the pair reunited the following year and remarried. The couple hosted Communist exile Leon Trotsky at their home during this period.

Rivera returned to murals with one made for the 1940 Golden Gate International Exposition held in San Franciso. In Mexico City, he spent from 1945 to 1951 working on a series of murals known as "From the Pre-Hispanic Civilization to the Conquest." His last mural was called "Popular History of Mexico."

By the mid-1950s, Rivera's health was in decline. He had traveled abroad for cancer treatment, but doctors were unable to cure him. Rivera died of heart failure on November 24, 1957, in Mexico City, Mexico.

Personal Life

Rivera lost his wife Kahlo, in 1954 and the following year, he married Emma Hurtado, his art dealer.

Since his death, Rivera is remembered as an important figure in 20th-century art. His childhood home is now a museum in Mexico. His life and relationship with Kahlo has been remained a subject of great fascination and speculation. On the big screen, actor Ruben Blades portrayed Rivera in the 1999 movie Cradle Will Rock . Alfred Molina later brought Rivera to life, co-starring with Salma Hayek in the 2002 acclaimed biographical film Frida .

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Diego Rivera

- Birth Year: 1886

- Birth date: December 8, 1886

- Birth City: Guanajuato

- Birth Country: Mexico

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Painter and muralist Diego Rivera sought to make art that reflected the lives of the working class and native peoples of Mexico.

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1957

- Death date: November 24, 1957

- Death City: Mexico City

- Death Country: Mexico

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Diego Rivera Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/diego-rivera

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 27, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Famous Painters

Georgia O'Keeffe

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Margaret Keane

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Who is Frida Kahlo?

Diego Rivera

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- PBS - American Masters - Diego Rivera: Rivera In America

- Artnet - Diego Rivera

- MY HERO - Diego Rivera

- The Art Story - Biography of Diego Rivera

- Art in Context - Diego Rivera - Discover the Life and Legacy of Diego Rivera’s Art

- Smarthistory - The History of Mexico: Diego Rivera’s Murals at the National Palace

- Official Site of Diego Rivera

- San Jose State University - The Timeline of the Turbulent Life of Diego Rivera: His Art and his Politics

- Diego Rivera - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Diego Rivera - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Diego Rivera (born December 8, 1886, Guanajuato , Mexico—died November 25, 1957, Mexico City) was a Mexican painter whose bold large-scale murals stimulated a revival of fresco painting in Latin America .

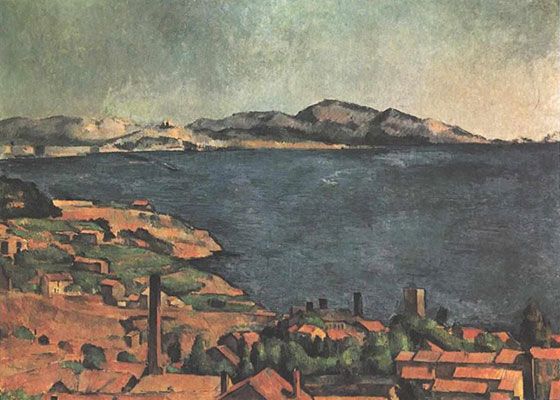

A government scholarship enabled Rivera to study art at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City from age 10, and a grant from the governor of Veracruz enabled him to continue his studies in Europe in 1907. He studied in Spain and in 1909 settled in Paris, where he became a friend of Pablo Picasso , Georges Braque , and other leading modern painters. About 1917 he abandoned the Cubist style in his own work and moved closer to the Post-Impressionism of Paul Cézanne , adopting a visual language of simplified forms and bold areas of colour.

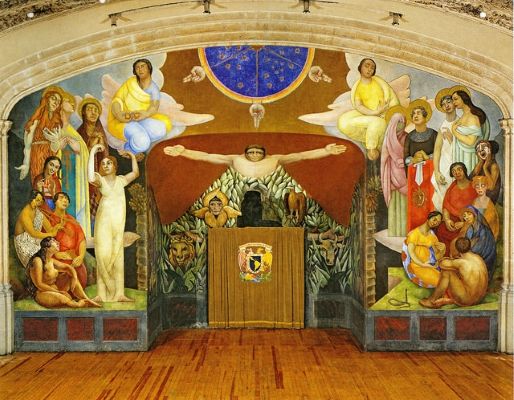

Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921 after meeting with fellow Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros . Both sought to create a new national art on revolutionary themes that would decorate public buildings in the wake of the Mexican Revolution . On returning to Mexico, Rivera painted his first important mural , Creation , for the Bolívar Auditorium of the National Preparatory School in Mexico City. In 1923 he began painting the walls of the Ministry of Public Education building in Mexico City, working in fresco and completing the commission in 1930. These huge frescoes, depicting Mexican agriculture, industry, and culture , reflect a genuinely native subject matter and mark the emergence of Rivera’s mature style. Rivera defines his solid, somewhat stylized human figures by precise outlines rather than by internal modeling. The flattened, simplified figures are set in crowded, shallow spaces and are enlivened with bright, bold colours. The Indians, peasants, conquistadores, and factory workers depicted combine monumentality of form with a mood that is lyrical and at times elegiac.

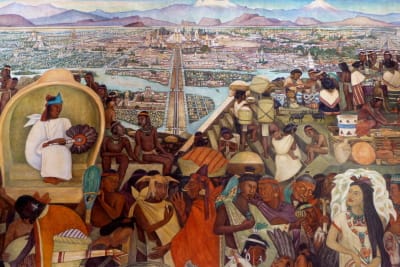

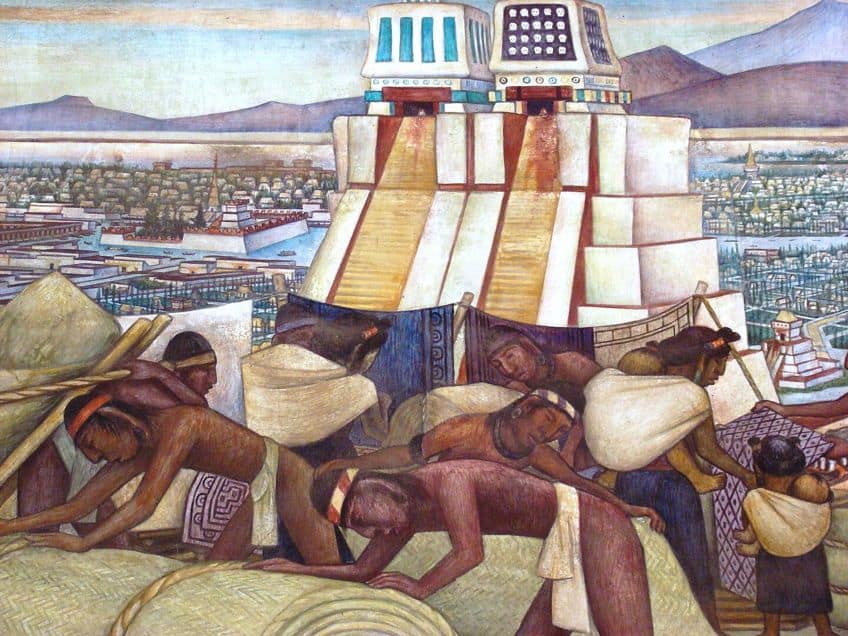

Rivera’s next major work was a fresco cycle in a former chapel at what is now the National School of Agriculture at Chapingo (1926–27). His frescoes there contrast scenes of natural fertility and harmony among the pre-Columbian Indians with scenes of their enslavement and brutalization by the Spanish conquerors. Rivera’s murals in the Cortés Palace in Cuernavaca (1930) and the National Palace in Mexico City (1930–35) depict various aspects of Mexican history in a more didactic narrative style.

Rivera was in the United States from 1930 to 1934, where he painted murals for the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco (1931), the Detroit Institute of Arts (1932), and Rockefeller Center in New York City (1933). His Man at the Crossroads fresco in Rockefeller Center offended the sponsors because the figure of Vladimir Lenin was in the picture; the work was destroyed by the centre but was later reproduced by Rivera at the Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City. After returning to Mexico, Rivera continued to paint murals of gradually declining quality. His most ambitious and gigantic mural, an epic on the history of Mexico for the National Palace, Mexico City, was unfinished when he died. Frida Kahlo , who married Rivera twice, was also an accomplished painter. Rivera’s autobiography, My Art, My Life , was published posthumously in 1960.

Diego Rivera

Mexican Painter and Muralist

Summary of Diego Rivera

Widely regarded as the most influential Mexican artist of the 20 th century, Diego Rivera was truly a larger-than-life figure who spent significant periods of his career in Europe and the U.S., in addition to his native Mexico. Together with David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco , Rivera was among the leading members and founders of the Mexican Muralist movement. Deploying a style informed by disparate sources such as European modern masters and Mexico's pre-Columbian heritage, and executed in the technique of Italian fresco painting, Rivera handled major themes appropriate to the scale of his chosen art form: social inequality; the relationship of nature, industry, and technology; and the history and fate of Mexico. More than half a century after his death, Rivera is still among the most revered figures in Mexico, celebrated for both his role in the country's artistic renaissance and re-invigoration of the mural genre as well as for his outsized persona.

Accomplishments

- Rivera made the painting of murals his primary method, appreciating the large scale and public accessibility—the opposite of what he regarded as the elitist character of paintings in galleries and museums. Rivera used the walls of universities and other public buildings throughout Mexico and the United States as his canvas, creating an extraordinary body of work that revived interest in the mural as an art form and helped reinvent the concept of public art in the U.S. by paving the way for the Federal Art Program of the 1930s.

- Mexican culture and history constituted the major themes and influence on Rivera's art. Rivera, who amassed an enormous collection of pre-Columbian artifacts, created panoramic portrayals of Mexican history and daily life, from its Mayan beginnings up to the Mexican Revolution and post-Revolutionary present, in a style largely indebted to pre-Columbian culture.

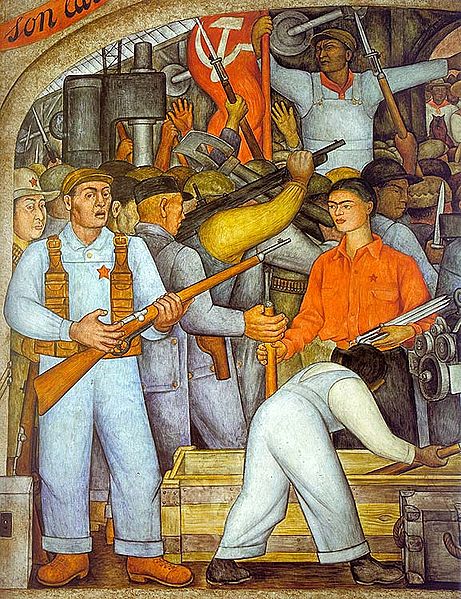

- A lifelong Marxist who belonged to the Mexican Communist Party and had important ties to the Soviet Union, Rivera is an exemplar of the socially committed artist. His art expressed his outspoken commitment to left-wing political causes, depicting such subjects as the Mexican peasantry, American workers, and revolutionary figures like Emiliano Zapata and Lenin. At times, his outspoken, uncompromising leftist politics collided with the wishes of wealthy patrons and aroused significant controversy that emanated inside and outside the art world.

The Life of Diego Rivera

When Diego Rivera first returned home to Mexico from his artistic studies in France, he was so overcome with joy that he fainted. Later, he said, "Great art is like a tree, which grows in a particular place and has a trunk, leaves, blossoms, boughs, fruit, and roots of its own .. The secret of my best work is that it is Mexican."

Important Art by Diego Rivera

View of Toledo

A stunning tribute to two of Rivera's favorite masters—El Greco and Paul Cézanne— View of Toledo exemplifies Rivera's tendency to unite traditional and more modern approaches in his work. The landscape is a reworking of the famous 1597 landscape painting by El Greco, whose work Rivera studied during his time in Spain; Rivera's version even deploys the same viewpoint as the Spanish Old Master. At the same time, the subdued palette, flattened forms, and unconventional use of perspective suggest the artist's reverence for Cézanne, his L'Estaque landscapes. This artwork also documents the beginning of Rivera's Cubist phase.

Oil on canvas - Fundacion Amparo R. de Espinosa, Puebla

Zapatista Landscape - The Guerrilla

In this work, painted during Rivera's sojourn in Paris, the artist deployed Cubism—a style he once characterized as a "revolutionary movement"—to depict the Mexican revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata, here seen with attributes such as a rifle, bandolier, hat, and sarape . The work's collage-like approach is suggestive of the Synthetic rather than Analytic phase of Cubism. Executed at the height of the Mexican Revolution, the painting—later described by its creator as "probably the most faithful expression of the Mexican mood that I have ever achieved"—manifests the increasing politicization of Rivera's work.

Oil on canvas - Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City

Motherhood - Angelina and the Child

Motherhood is a modernizing, Cubist treatment on a perennial art historical theme: the Madonna and Child. In this painting, Angelina Beloff, Rivera's common-law wife for twelve years, holds their newborn son, Diego, who died of influenza just months after his birth. The painting beautifully illustrates Rivera's unique approach to Cubism, which rejected the somber, monochromatic palette deployed by artists such as Pablo Picasso or Georges Braque in favor of vivid colors more reminiscent of those used by Italian Futurist artists like Gino Severini or Giacomo Balla.

Oil on canvas - Museo de Arte Alvar y Carmen T. de Carrillo Gil, Mexico

His first commission from Mexican Minister of Education Jose Vasconcelos, Creation is the first of Rivera's many murals and a touchstone for Mexican Muralism. Treating, in the artist's words, "the origins of the sciences and the arts, a kind of condensed version of human history"—the work is a complex allegorical composition, combining Mexican, Judeo-Christian, and Hellenic motifs. It depicts a number of allegorical figures—among them Faith, Hope, Charity, Education, and Science—all seemingly represented with unmistakably Mexican features. The figure of Song was modeled on Guadalupe Marin, who later became Rivera's second wife. Through such features of the work as the use of gold leaf and the monumental, elongated figures, the mural reflects the importance of Italian and Byzantine art for Rivera's development.

Fresco in encaustic with gold leaf - Museo de San Idelfonso, Mexico City

Man, Controller of the Universe (Man in the Time Machine)

As its title indicates, the painting is a powerful representation of the human race "at the crossroads" of reinforcing or competing forces and ideologies: science, industrialization, Communism, and capitalism. Revealing Rivera's dedication to Communism and other left-wing causes, the painting has at its center a heroic worker surrounded by four propeller-like blades; it contrasts a mocking portrayal of society women, seen on the left, with a sympathetic portrayal of Lenin surrounded by proletarians of different races, on the right. Commissioned by the Mexican government, this painting is a smaller but nearly identical recreation of Man at the Crossroads , the Rockefeller-commissioned mural for the soon-to-be-completed Rockefeller Center. The New York City mural was destroyed a year before this work, amid controversy over Rivera's portrait of Lenin and his subsequent refusal to remove the image.

Fresco - Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City

Portrait of Lupe Marin

In this magnificent portrait of his second wife from whom he separated the previous decade, Rivera again reveals his profound artistic debt to the European painting tradition. Utilizing a device deployed by such artists as Velazquez, Manet, and Ingres—and which Rivera would himself use in his 1949 portrait of his daughter Ruth—he portrays his subject partially in reflection through his depiction of a mirror in the background. The painting's coloration and the subject's expressive hands call to mind another artistic hero, El Greco, while its composition and structure suggest the art of Cézanne.

Oil on canvas - Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City

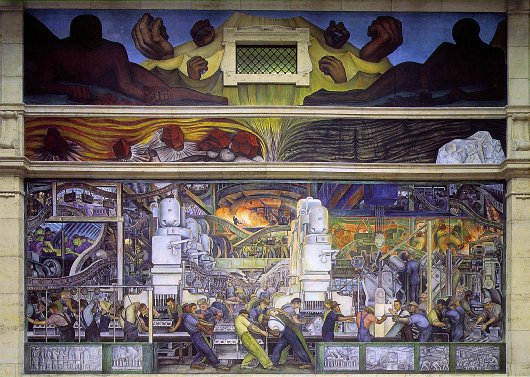

The Detroit Industry Fresco Cycle

The twenty-seven panels comprising this cycle are a tribute to Detroit's manufacturing base and workforce of the 1930s and constitute the finest example of fresco painting in the United States. Here, Rivera takes large-scale industrial production as the subject of the work, depicting machinery with exceptional attention to detail and artistry. The overall iconography of the cycle reflects the duality concept of Aztec culture via the two sides of industry: the one beneficial to society (vaccines) and the other harmful (lethal gas). Other dichotomies recur in this work, as Rivera contrasts tradition and progress, industry and nature, and North and South America. He uses multiple allegories based on the history of the continents, as well as contemporary events to build a dramatic artwork.

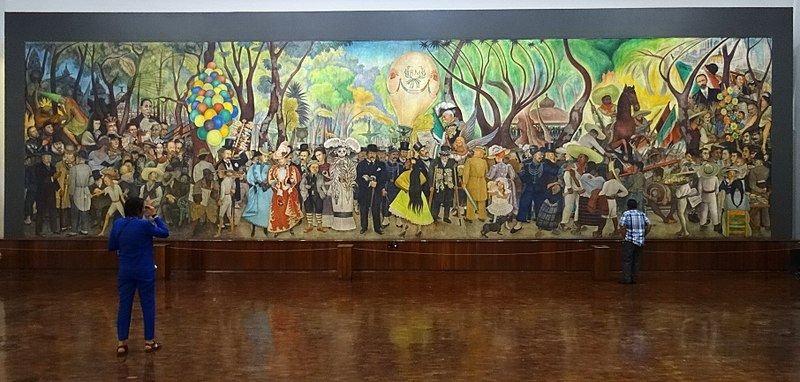

Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park

Rivera revisits the theme of Mexican history in this crowded, dynamic composition, replete with meaningful portraits, historical figures, and symbolic elements. Conceived as a festive pictorial autobiography, Rivera represents himself at the center as a child holding hands with the most celebrated of Guadalupe Posada's creations: the skeletal figure popularly known as "Calavera Catrina." He represents himself joining this quintessential symbol of Mexican popular culture and is shown to be protected by his wife, the painter Frida Kahlo, who holds in her hand the yin-yang symbol, the Eastern equivalent of Aztec duality. The mural combines the artist's own childhood experiences with the historical events and sites that took place in Mexico City's Alameda Park, such as the crematorium for the victims of the Inquisition during the times of Cortes, the U.S. army's encampment in the park in 1848, and the major political demonstrations of the 19 th century. As in many previous works, Rivera juxtaposes historical events and figures, deliberately rejecting the Western tradition of linear narrative.

Transportable fresco - Museo Mural Diego Rivera, Mexico City

Biography of Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera and his fraternal twin brother (who died at the age of two) were born in 1886 in Guanajuato, Mexico. His parents were both teachers; his mother was a devoted Catholic mestiza (part European, part Indian) and his father, a liberal criollo (Mexican of European descent). Diego's exceptional artistic talent was obvious to his parents from an early age, and they set aside a room in the house for him in which he painted his first "murals" on the walls. When Diego was six, his family moved from Guanajuato to Mexico City, to avoid the tensions caused by his father's role as co-editor of the opposition newspaper El Democrata . Once in Mexico City, his mother decided to send Diego to the Carpantier Catholic College.

Early Training

By the age of ten, Rivera decided he wanted to attend art school, despite his father's desire that he pursue a military career. By the age of twelve, Rivera was enrolled full-time at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts, where he received training modeled on conservative European academies; one of his painting teachers had studied with Ingres, and another required Rivera to copy classical sculpture. Trained in traditional techniques in perspective, color, and the en plein air method, Rivera also received instruction from Gerardo Murillo, one of the ideological forces behind the Mexican artistic revolution and a staunch defender of indigenous crafts and Mexican culture. With Murillo's support, Rivera was awarded a travel grant to Europe in 1906.

In Spain, Rivera studied the work of El Greco, Velazquez, Goya, and the Flemish masters that he saw in the Prado Museum, and which provided him with a strong foundation for his later painting. At the studio of the Spanish realist painter Eduardo Chicharro, Rivera became acquainted with the leading figures of the Madrid avant-garde , including the Dada poet Ramon Gomez de la Serna and the writer Ramon Valle-Inclan.

In 1909 Rivera traveled to Paris and Belgium with Valle-Inclan, where he met the Russian painter Angelina Beloff who would be Rivera's partner for twelve years. Returning to Mexico City in 1910, Rivera was offered his first exhibition at the San Carlos Academy. Rivera's return coincided with the onset of the Mexican Revolution, which lasted until 1917. Despite the political upheaval, Rivera's exhibit was a great success, and the money earned from the sale of his work enabled him to return to Europe.

Back in Paris, Rivera became a fervent adherent of Cubism , which he regarded as a truly revolutionary form of painting. However, Rivera's difficult relationships with the other members of the movement came to a tumultuous end following a violent incident with the art critic Pierre Reverdy, resulting in a definitive break with the circle and the termination of his friendships with Picasso , Braque , Juan Gris , Fernand Leger , Gino Severini , and Jacques Lipchitz .

Rivera subsequently shifted his focus to the work of Cézanne and Neoclassical artists such as Ingres, as well as a rediscovery of figural painting. Receiving another grant to travel to Italy to study classical art , Rivera copied Etruscan, Byzantine , and Renaissance artworks, and developed a particular interest in the frescoes of the 14 th and 15 th centuries of the Italian Renaissance. In 1921, following the appointment of Jose Vasconcelos as the new Mexican Minister of Education, Rivera returned to his home country, leaving behind his partner, Angelina Beloff, as well as Marevna Stebelska, another Russian artist, with whom Rivera had a daughter, Marika, in 1919.

Mature Period

Rivera returned to Mexico with a reawakened artistic perspective, deeply influenced by his study of Classical and ancient art. There, he was afforded the opportunity to visit and study many pre-Columbian archaeological sites under the auspices of the Ministry of Education's art program. Yet his first mural painting, produced for the National Preparatory School and entitled Creation (1922), shows a strong influence of Western art. Rivera soon became involved with local politics through his membership in the Revolutionary Union of Technical Workers and his entry into the Mexican Communist Party in 1922. At this time, he painted frescoes in the Ministry of Education in Mexico City and the National School of Agriculture in Chapingo. During the latter project, he became involved with the Italian photographer Tina Modotti , who had modeled for his murals; the affair prompted him to separate from his wife at the time, Lupe Marin.

In 1927, Rivera visited the Soviet Union to attend the celebrations of the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution, an experience he found extremely inspiring. He spent nine months in Moscow, teaching monumental painting at the School of Fine Arts. Upon his return to Mexico, he married the painter Frida Kahlo , who was twenty-one years his junior, and became the director of the Academy of San Carlos. His radical ideas about education earned him enemies among the conservative faculty and student body; at the same time, he was expelled from the Communist Party for his cooperation with the government. Politically cornered, Rivera found support in the American ambassador to Mexico, Dwight W. Morrow, who commissioned him to paint a mural in the Cortes Palace in Cuernavaca depicting the history of that city. A great admirer of Rivera's work, Morrow offered the artist the opportunity to travel to the United States, all expenses paid. Rivera remained in the U.S. for four years. There, the always-prolific artist worked around the clock, painting murals in San Francisco, New York, and Detroit, celebrating the powerful forces of unions, education, industry, and art. In New York, he met with enormous popularity (his one-man show at The Museum of Modern Art had fifty-seven thousand visitors) as well as controversy (some of his murals were threatened with physical harm). Rivera's American adventure ended in 1933, when John D. Rockefeller, Jr., ordered the destruction of the mural he had commissioned for the lobby of Rockefeller Center, Man at the Crossroads , because of both Rivera's unwillingness to eliminate the portrait of Lenin and for what the Rockefeller family regarded as an offensive portrait of David Rockefeller.

Later Years and Death

After Rivera returned to Mexico, he and Kahlo shared a house-studio in a beautiful Bauhaus -style building in Mexico City that can still be visited today. From 1929 until 1945, Rivera worked on and off in the National Palace, creating some of his most famous murals there. In 1937, he and Kahlo helped Leon Trotsky - a major Russian Communist leader - and his wife obtain political exile; the Trotskys lived with Rivera and Kahlo for two years in the "Blue House" in the suburb of Coyoacan. Two years later, Rivera and Kahlo divorced, although they remarried a year later in San Francisco, while Rivera was working for the Golden Gate International Exposition. The two had a tremendously passionate, and an extremely tumultous relationship - one that can easily extrapolated by viewing her very personal artworks. The couple would ultimately remain together until Kahlo's death in 1954.

During his last years, Diego continued to paint murals, sometimes working on portable panels. He also produced a large number of oil portraits, usually of the Mexican bourgeoisie, children, or American tourists. These works are not always remarkable, and they are often infused with a kitschy aesthetic reminiscent of Pop art . However, they were very successful during his lifetime, and provided a way for the artist to acquire more pre-Columbian objects for his spectacular collection. Today, his collection is housed in the Anahuacalli Museum, a building inspired by the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan and designed by Rivera himself.

Widowed and already sick with cancer, Rivera married for the third time in 1955 to Emma Hurtado, his art dealer and rights holder since 1946. Following a trip to the Soviet Union made in the hope of curing his cancer, Rivera died in Mexico in 1957 at age seventy. His wish to have his ashes mingled with those of Kahlo was not honored, and he was buried in the Rotunda of Famous Men of Mexico.

The Legacy of Diego Rivera

Rivera saw the artist as a craftsman at the service of the community, who, as such, needed to deploy an easily accessible visual language. This concept greatly influenced American public art, helping give rise to governmental initiatives such as Franklin Roosevelt's Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration , whose artists depicted scenes from American life on public buildings. With his socially and politically expansive artistic vision, narrative focus, and use of symbolic imagery, Rivera inspired such diverse artists as Ben Shahn , Thomas Hart Benton , and Jackson Pollock .

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on Diego Rivera

- Diego Rivera, 1886-1957: A Revolutionary Spirit in Modern Art (Taschen Basic Art) Our Pick By Andrea Kettenmann

- Dreaming with His Eyes Open: A Life of Diego Rivera (Discovery Series) By Patrick Marnham

- Diego Rivera By Pete Hamill

- Diego Rivera, The Complete Murals Our Pick By Luis Martin Lozano, Juan Coronel Rivera

- Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Murals By Linda Bank Downs

- Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros Our Pick By Desmond Rochfort

- My Art, My Life: An Autobiography (Dover Fine Art, History of Art) Our Pick By Diego Rivera, Gladys March

- Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art Our Pick By Leah Dickerman, Anna Indych-Lopez

- The Diego Rivera Mural Project Info and Preservation of Diego Mural in San Francisco, CA

- Diego Rivera Web Museum Articles and works dedicated to the mexican Muralist

- Diego Rivera Experts

- Diego Rivera Celebrated by Google doodle By David Batty / The Guardian / December 7, 2011

- Time Capsule With Pulse on Present Our Pick By Karen Rosenberg / The New York Times / November 17, 2011

- The Mural Vanishes By Peter Catapano / The New York Times / April 1, 2011

- Kahlo and Rivera, Side by Side in Istanbul Our Pick By Susan Fowler / The New York Times / February 7, 2011

- Rebel without a pause: The Tempestuous Life of Diego Rivera By Jim Tuck / Mexconnect / October 9, 2008

- Rivera, Fridamania's Other Half, Gets His Due By Elisabeth Malkin / The New York Times / December 25, 2007

- Archives of American Art, The Smithsonian Photographs and documents on Rivera, and related artists

- The Cradle will Rock (1999) Rivera's Rockerfeller murals are part of the plot in this movie. Diego Rivera portrayed by Ruben Blades

- Frida (2002) Diego Rivera is portrayed by Alfred Molina in this main-stream movie

Similar Art

The Bay of Marseille, Seen from L'Estaque (1885)

The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope (1905)

Bowl of Fruit, Violin and Bottle (1914)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by The Art Story Contributors

Edited and published by The Art Story Contributors

- World Biography

Diego Rivera Biography

Born: December 8, 1886 Guanajuato, Mexico Died: November 25, 1957 Mexico City, Mexico Mexican painter

Diego Rivera was one of Mexico's most famous painters. He rebelled against the traditional school of painting and developed a style that combined historical, social, and political ideas. His great body of work reflects cultural changes taking place in Mexico and around the world during the turbulent twentieth century.

The young artist

Diego Maria Rivera and his twin brother Carlos were born in Guanajuato, Guanajuato State, Mexico, on December 8, 1886. Less than two years later his twin died. Diego's parents were Diego Rivera and Maria Barrientos de Rivera. His father worked as a teacher, an editor for a newspaper, and a health inspector. His mother was a doctor. Diego began drawing when he was only three years old. His father soon built him a studio with canvas-covered walls and art supplies to keep the young artist from drawing on the walls and furniture in the house. As a child, Rivera was interested in trains and machines and was nicknamed "the engineer." The Rivera family moved to Mexico City, Mexico, in 1892.

In 1897 Diego began studying painting at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts in Mexico City. His instructors included Andrés Ríos Félix Para (1845–1919), Santiago Rebull (1829–1902), and José María Velasco (1840–1912). Para showed Rivera Mexican art that was different from the European art that he was used to. Rebull taught him that a good drawing was the basis of a good painting. Velasco taught Rivera how to produce three-dimensional effects. He was also influenced by the work of José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913), who produced scenes of everyday Mexican life engraved on metal.

In 1902 Rivera was expelled from the academy for leading a student protest when Porfirio Díaz (1830–1915) was reelected president of Mexico. Under Díaz's leadership, those who disagreed with government policies faced harassment, imprisonment, and even death. Many of Mexico's citizens lived in poverty, and there were no laws to protect the rights of workers. After Rivera was expelled, he traveled throughout Mexico painting and drawing.

Art in Europe

Although Rivera continued to work on his art in Mexico, he dreamed of studying in Europe. Finally, Teodora A. Dehesa, the governor of Veracruz, Mexico, who was known for funding artists, heard about Rivera's talent and agreed to pay for his studies in Europe. In 1907 Rivera went to Madrid, Spain, and worked in the studio of Eduardo Chicharro. Then in 1909 he moved to Paris, France. In Paris he was influenced by impressionist painters, particularly Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919). Later he worked in a postimpressionist style inspired by Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Georges Seurat (1859–1891), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Raoul Dufy (1877–1953), and Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920).

As Rivera continued his travels in Europe, he experimented more with his techniques and styles of painting. The series of works he produced between 1913 and 1917 are cubist (a type of abstract art usually based on shapes or objects rather than pictures or scenes) in style. Some of the pieces have Mexican themes, such as the Guerrillero (1915). By 1918 he was producing pencil sketches of the highest quality, an example of which is his self-portrait. He continued his studies in Europe, traveling throughout Italy learning techniques of fresco (in which paint is applied to wet plaster) and mural painting before returning to Mexico in 1921.

Murals and frescoes

Rivera believed that all people (not just people who could buy art or go to museums) should be able to view the art that he was creating. He began painting large murals on walls in public buildings. Rivera's first mural, the Creation (1922), in the Bolívar Amphitheater at the University of Mexico, was the first important mural of the twentieth century. The mural was painted using the encaustic method (a process where a color mixed with other materials is heated after it is applied). Rivera had a great sense of color and an enormous talent for structuring his works. In his later works he used historical, social, and political themes to show the history and the life of the Mexican people.

Between 1923 and 1926 Rivera created frescoes in the Ministry of Education Building in Mexico City. The frescoes in the Auditorium of the National School of Agriculture in Chapingo (1927) are considered his masterpiece. The oneness of the work and the quality of each of the different parts, particularly the feminine nudes, show off the height of his creative power. The general theme of the frescoes is human biological and social development. The murals in the Palace of Cortés in Cuernavaca (1929-1930) depict the fight against the Spanish conquerors.

Marriage, art, and controversy in the United States

In 1929 Rivera married the artist Frida Kahlo (1907–1954). The couple traveled in the United States, where Rivera produced many works of art, between 1930 and 1933. In San Francisco he painted murals for the Stock Exchange Luncheon Club and the California School of Fine Arts. Two years later he had an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. One of his most important works is the fresco in the Detroit Institute of Arts (1933), which depicts industrial life in the United States. Rivera returned to New York and began painting a mural for Rockefeller Center (1933). He was forced to stop work on the mural because it included a picture of Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), the founder of the Russian Communist Party and the first leader of the Soviet Union. Many people in the United States disagreed with communism (a political and economic system in which property and goods are owned by the government and are supposed to be given to people based on their need) and Lenin and the mural was later destroyed. Rivera was a member of the Mexican Communist Party and many of his works included representations of his political beliefs. In New York Rivera also did a series of frescoes on movable panels depicting a portrait of America for the Independent Labor Institute before returning to Mexico in 1933.

Back to Mexico

After Rivera and Kahlo returned to Mexico, he painted a mural for the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City (1934). This was a copy of the project that he had started in Rockefeller Center. In 1935 Rivera completed frescoes, which he had left unfinished in 1930, on the stairway in the National Palace. The frescoes show the history of Mexico from pre-Columbian times to the present and end with an image representing Karl Marx (1818–1883), the German philosopher and economist whose ideas became known as Marxism. These frescoes show Rivera's political beliefs and his support of Marxism. The four movable panels he worked on for the Hotel Reforma (1936) were removed from the building because they depicted a representation of his views against Mexican political figures. During this period he painted portraits of Lupe Marín and Ruth Rivera and two easel paintings, Dancing Girl in Repose and the Dance of the Earth.

In 1940 Rivera returned to San Francisco to paint a mural for a junior college on the general theme of culture in the future. Rivera believed that the culture of the future would be a combination of the artistic genius of South America and the industrial genius of North America. His two murals in the National Institute of Cardiology in Mexico City (1944) show the development of cardiology (the study of the heart) and include portraits of the outstanding physicians in that field. In 1947 he painted a mural for the Hotel del Prado, A Dream in the Alameda.

A celebration of fifty years of art

In 1951 an exhibition honoring fifty years of Rivera's art took place in the Palace of Fine Arts. His last works were mosaics for the stadium of the National University and for the Insurgents' Theater, and a fresco in the Social Security Hospital No. 1. Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954. Diego Rivera died in Mexico City on November 25, 1957.

For More Information

Hamill, Pete. Diego Rivera. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999.

Marnham, Patrick. Dreaming with His Eyes Open: A Life of Diego Rivera. New York: Knopf, 1998.

Rivera, Diego, and Gladys March. My Art, My Life; an Autobiography. New York: Citadel Press, 1960. Reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1991.

Wolfe, Bertram David. The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera. New York: Stein and Day, 1963. Reprint, New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000.

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

Diego Rivera Biography

The public persona of Diego Rivera and the heroic status bestowed upon him in Mexico was such that the artist became the subject of myth in his own lifetime. His own memories, as recorded in his various autobiographies, have contributed to his image as a precocious child of exotic parentage, a young firebrand who fought in the Mexican Revolution, and a visionary who completely repudiated his participation in the European avant-garde to follow a predestined course as the leader of Mexico's art revolution. The facts are more prosaic. The product of a middle-class family, the young artist completed an academic course of training at the prestigious Academic course of San Carlos before leaving Mexico for the traditional period of European study. During his first stay abroad, like many other young painters, he was greatly influenced by Post-Impressionists Paul Cezanne , Van Gogh , and Gauguin . As for participating in the early battles of the Mexican Revolution, recent research would seem to indicate that he did not. Although he was in Mexico for a time in late 1910-early 1911, his tales of fighting with the Zapatistas cannot be substantiated. From the summer of 1911 until the winter of 1920, Rivera lived in Paris. This period of his career has been brilliantly illuminated by Ramon Favela in the 1984-85 exhibition "Diego Rivera: The Cubist Year." The work of these years reveals diverse influences, from the art of El Greco and new applications of mathematical principles, in which Rivera had been well schooled at San Carlos, to subject matter and techniques that reflect the discussions on the role of art in the service of the revolution that preoccupied the community of emigre artists in Montparnasse. During this time period, Diego Rivera left Spain for a long tour in France, Belgium, Holland and England hoping to solve a problem he couldn't really define. He admired greatly the work of Breughel, Hogarth and Francisco Goya . He wished that his work could provoke the intense feeling got when he looked at their work. In Paris he went to a shop where he saw the work of newer painters who called themselves Cubists. He saw Picasso's Harlequin and paintings by Georges Braque and Derain. Rivera spent hours in Paris looking at paintings by Cezanne . Rivera would become a part of this Parisian art world for a decade. He would argue, study, paint, learn so much and do so much; yet at the end of ten years he still felt that something was absent from his work. His paintings seemed only to be enjoyed by well-educated people who could afford to buy them for their homes. He thought that art should be enjoyed by everyone-especially poor, working people. He was developing a growing interest in the masses and began to deepen his understanding of the folk art and ancient masterpieces of his native land. Art, Rivera felt, was never so isolated from life as when he was there in Europe. Even after settling in Paris, Rivera returned every year to Spain to paint - often in the style of cubists such as Pablo Picasso , Salvador Dali , and Paul Klee . During the years from 1913 to 1918, Rivera devoted himself almost entirely to cubism and found himself getting caught up in his search for new truths. Among his works during this period were Portrait of Two Women , Portrait of Ramon Gomez , Eiffel Tower , and Still Life, 1918 . In all of these paintings and indeed of the cubist style as a whole it appeared that the artists took apart their subjects and created new objects of their own creation.

By 1917, River had begun to turn away from Cubism , and by 1918 his rejection of Cubist style, if not all the tenets of Cubism, was complete. The reasons for this rejection have not been completely determined, but certainly the inspiration of the Russian Revolution and the general return to realism among European artists were factors that contributed. In 1920, Rivera went to Italy. There, in the murals of the Italian partners of the quattrocento, he found the inspiration for a new and revolutionary public art capable of furthering the ideals of the ongoing revolution in his native land.

Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921 and soon became one of a number of Mexican and foreign artists who received commissions for murals in public buildings from the new government. By 1923, the completion of the first of his monumental series at the Secretaria de Educacion Publica and his assumption of control over the decoration of the entire building had established his preeminence in the movement now known as the Mexican Mural Renaissance. In his work at the Secretaria, which would occupy him for another four years, and in the chapel at the former Escuela de Agricultura at Chapingo, Rivera brought to full development his classical figure style and his epic approach to historical painting, which focused on subjects that promoted revolutionary ideas and celebrated the indigenous cultural heritage of Mexico. In the period following World War I, the literary, artistic, and intellectual vitality of post-revolutionary Mexico, in which the mural movement played an integral role, created a cultural "mecca" that drew young artists from the United States, Europe, and Latin America. As a result, by the late 1920s, Rivera's murals, and those of Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, were well known in the United States. In the early 1930s, Rivera became one of the most sought-after artists in this country. In addition to numerous commissions for easel paintings, his received commissions for three murals in San Francisco and was given a one-person exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Also, his costume and set designs were used in the ballet H. P. (horsepower), which premiered in Philadelphia; he decorated the central court of Detroit Institute of Arts; he was invited by General Motors to create murals at the Chicago World's Fair, and he painted murals at Rockefeller Center and the New Workers School in New York. Rivera's sojourns in the United States were pivotal to his work. For the first time in his career as a muralist, he was separated from the rich cultural history upon which he drew for his subjects and was under no compulsion to confine himself to the themes in promotion of Mexican nationalist ideals. He was also able, at least temporarily, to escape from the turmoil of his precarious political position in Mexico, where the Mexican Communist Party, of which he had been a member between 1922 and 1929, disapproved of his growing ties to Mexico's government. Finally, he was at last able to indulge his deep fascination with technology, which was evident in a highly developed from in the industrial society of the United States. Rivera's period of work in the United States enabled him to explore an industrial society, to analyze the role of the artist within it, to postulate his link to the universal order by analogy with earlier societies such as that of the Aztecs, and finally to present his own concept of a new society based on science and technology. The murals in the United States served to clarify his understanding of his native Mexico and expanded his personal philosophy. They were the source of inspiration for many of his later works, including the late murals at the Palacio Nacional and those at the Golden Gate Exposition in San Francisco, the Lerma waterworks, and the Hospital de la Raza. Rivera's activities in the United States were marked by controversy. In Detroit, he was accused of using sacrilegious and even pornographic subject matter, his politics were questioned, and he was criticized for causing the dreaded industry to invade the museum. The safety of the murals was even threatened until Edsel Ford made a public statement in their defense. Rivera, who believed that Detroit Industry Fresco cycle was his greatest artistic achievement, was dismayed by these attacks. An even larger and more bitter controversy erupted at Rockefeller Center in New Yor when Rivera included a portrait of Lenin in his representation of the new society. Asked to remove it, Rivera refused and the mural was ultimately destroyed, on the greatest scandals of art history. When Rivera returned to Mexico in December 1933, he was one of the most highly publicized artists in United States history, hailed by the intellectual left and the art community and scorned by conservatives and the corporate patrons who had once sought him out. Rivera's influence on American artists continued throughout the 1930s through the agency of the mural section of the Federal Art Project of the works Progress Administration. This project, which owed its very creation to the example of the Mexican government's commissioning of works for public buildings, distributed to participating artists a handbook outlining Rivera's fresco technique. Rivera's popularity with the American public continued into the 1940s, but his reputation among art critics and scholars diminished as realism and emphasis on social content fell into disfavor in the face of a growing interest in the styles of Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism, then being brought to this country by European artists fleeing Hitler. It is perhaps understandable that Rivera's work became inextricably linked with social realism. His trip to the U.S.S.R. in 1927-28 brought him into contact with many young Russian artists who later carried out government mural commissions, and his works were well known in Moscow through the publication of newspaper and magazine articles. The artists, such as Ben Shahn, with whom Rivera associated during his two stays in New York were politically active individuals who, like their Russian counterparts, admired Rivera as the great revolutionary who had put into practice what they still hoped to achieve. Rivera's political philosophy and the subject of his murals did create a common bond between his work and that of the social realists. However, his mural style, indeed his overall aesthetic, modeled as it was on his studies of Italian Renaissance frescoes, classical proportions, pre-Colombian sculptural forms, Cubist space, and Futurist conventions of movement, bears little relationship to social realism. Over the past forty years, the critical opinion in the United States has remained virtually unchanged: Rivera's work and the Mexican mural movement as a whole have been characterized as politically motivated, stylistically retrograde, and historically isolated. Furthermore, Mexican scholars have traditionally emphasized the overt revolutionary ideals and didactic content of Rivera's murals in Mexico, thus extolling the very aspects of his work that have carried a negative connotation in the United States. In Mexico Rivera's work is synonymous with institutionalized ideals of the Mexican Revolution, which promoted indigenous culture to the exclusion of foreign influence. As a consequence, in Mexico the vast body of published literature on Rivera has concentrated on his Mexican murals, while little attention has been given to his work in the United States and Europe or to his easel paintings and drawings. Rivera's own statements support this view of his art as a unique and indigenous effort in service of revolutionary ideals. In his autobiography, "My Art, My Life", his Paris years and his sojourn in Italy are acknowledged as preparation for the creation of new revolutionary murals, but he characterized the formation of his mural style as spontaneously generated from indigenous Mexican culture:

My homecoming produced an aesthetic exhilaration which it is impossible to describe. It was as if I were being born anew, born in a new world... I was in the very center of the plastic world, where forms and colors existed in absolute purity. In everything I saw a potential masterpiece - the crowds, the markets, the festivals, the marching battalions, the workingmen in the shop and in the fields - in every glowing face, in every luminous child... My style was born as children are born, in a moment, except that this birth had come after a torturous pregnancy of thirty-five years."

While it is clear that the major accomplishments of Rivera's career were his vast mural programs in Mexico and the United States, the tendency of scholars and critics to limit their perspective and focus only on those works has served to overshadow his overall accomplishments as an artist. Rivera's life was filled with contradictions - a pioneer of Cubism who promoted art for art's sake, he became one of the leaders of the Mexican Mural Renaissance; a Marxist/Communist, he received mural commissions from the United States corporate establishment; a champion of the worker, he had a deep fascination with the form and function of machines and pronounced engineer America's greatest artists; a great revolutionary artist, he also painted society portraits. Part of the challenge in organizing this exhibition has been the attempt to separate fact from fiction. Gladys March, who wrote "My Art, My Life" with Rivera, commented on his mythologizing:

Rivera, who... was to transform the history of Mexico into one of the great myths of our century, could not, in recalling his own life to me, suppress his colossal fancy. He had already converted certain events, particularly of his early years, into legends."

Rivera's philosophy of art and life correspond to no specific dogma. He had an extraordinarily well developed intuitive sense that shaped his understanding of the world and his humanistic understanding of the role of the artist and the role of art in society. His ability to masterfully present universal images and ideas in his art continues to captivate the viewers today.

Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park

Man at the crossroads, history of mexico, pan american unity, el vendedora de flores, flower seller, 1942, flower festival, flower carrier, detroit industry murals, frozen assets, portrait of lupe marin, portrait of natasha gelman, symbolic landscape, flower vendor, nude with calla lilies, agrarian leader zapata, jacques lipchitz, indian warrior, crossing the barranca.

Diego Rivera: An expert guide to the artist, revolutionary and storyteller

Alastair Smart and Virgilio Garza, Head of Latin American Art at Christie’s, look at the life and art of the giant of modernism, and arguably the greatest painter in Mexico’s history

- Artist & Makers

Diego Rivera with his mural El agua, el origen de la vida , ( Water, source of life ), Mexico City, 1951. Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Gisèle Freund, reproduction de Georges Meguerditchian. Artwork: © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / DACS 2018

Born in the central Mexican city of Guanajuato in 1886, Diego Rivera went on to become one of the great Modernists of 20th-century art, as well as, arguably, the most important painter in his nation’s history.

Best-known for his murals on public buildings in Mexico and the United States, Rivera also made a number of easel paintings, watercolours and drawings. ‘Above all, he was a magnificent storyteller,’ says Virgilio Garza, Head of Latin American Art at Christie’s. ‘Rivera could tell tales on both an epic scale and a small, intimate one’.

In May 2018, his painting The Rivals realised $9,762,500 in The Collection of David and Peggy Rockefeller sale , setting a world-record price at auction for not just Rivera but any Latin American artist.

.jpg)

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), The Rivals , painted in 1931 . 60 x 50 in (152.4 x 127 cm). Sold for $9,762,500 on 9 May 2018 at Christie’s in New York. Artwork: © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / DACS 2018

Rivera’s early career and Cubism

A child prodigy, he started drawing at three. By the age of 10, Rivera was enrolled full-time at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts, in Mexico City. In 1907, he moved to Europe, settling first in Spain and then Paris. His work from this period reveals the influence of a wealth of European masters: from El Greco to Cézanne.

A friend and rival of Picasso’s, Rivera made his name as part of the Cubist movement. One of his main works in this style was 1915’s Zapatista Landscape , which today forms part of the collection of the Museo Nacional de Arte in Mexico City.

When did Rivera start painting murals?

Rivera returned to his homeland in the early 1920s, shortly after the Mexican Revolution concluded. The artist was one of the revolution’s greatest champions, helping to spread the message of a new Mexico by painting vast, state-sponsored murals — on buildings such as the National Palace and the Secretariat of Public Education in Mexico City. Here he connected the country’s revolutionary present to a heroic, ancient past.

‘Gone was the doubt which had tormented me in Europe,’ said Rivera, later in life. ‘I now painted as naturally as I breathed, spoke, or perspired’.

For Rivera, children were political — ‘They represented the hope of a new generation in a new Mexico’

Once back in Mexico, says his biographer Patrick Marnham in Dreaming with His Eyes Open: A Life of Diego Rivera (1988), ‘he now believed that an artist must be engagé and must not withdraw from society. Rivera challenged the stereotype of the artist as inarticulate genius.’

By the 1930s, he was being commissioned for murals in the United States too — in Detroit, San Francisco and New York — and had become a bona fide star of the art world. Rivera became only the second artist, after Henri Matisse, to be granted a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

Among his American patrons was Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, for whom he produced the aforementioned canvas, The Rivals , depicting a traditional festival in the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

The importance of pre-Columbian culture to Rivera

Rivera was an avid collector of pre-Columbian art, amassing 50,000 pieces over the course of his life, a large proportion of which are housed today at the Anahuacalli Museum in Mexico City.

These had a major influence on his art, the figures in which hark back to the heavily stylised, volumetric figures of Mesoamerican stone carvings. A fine example is 1926’s Madre con Hijos , where a mother and two children of steadfast gaze have a body-shape that might best be described as monumental.

.jpg)

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Communards (Comuna de Paris) , executed in 1928 . 19⅜ x 15½ in (49.2 x 39.4 cm). Sold for $492,500 on 20-21 November 2018 at Christie’s in New York

Common themes in Rivera’s work

Children are among the most common: both in scenes of everyday life and in portraits. Examples include Niña con rebozo , Portrait of Inesita Martínez , and Niña con muñeca de trapo . ‘It was normal for Rivera to paint these tender images of indigenous children that resonated with an American audience,’ Garza says. ‘Many who visited Mexico would bring back home pictures that captured a slice of Mexican culture.’

.jpg)

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Niña con muñeca de trapo , painted in 1939. 32⅛ x 24¾ in (81.6 x 62.9 cm).

.jpg)

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Niña con alcatraces (also known as Alcatraces ), executed circa 1936 . 15⅛ x 11 in (38.4 x 27.9 cm). Sold for $100,000 on 20-21 November 2018 at Christie’s in New York

For Rivera, children — were political. ‘They represented the hope of a new generation in a new Mexico,’ says Garza, ‘the promise of a bright future, marked by equality and social justice. His boys and girls are always captured positively and with dignity.’

.jpg)

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Niño con alcatraces , executed in 1950 . 15⅛ x 11 in (38.4 x 27.9 cm). Sold for $118,750 on 20-21 November 2018 at Christie’s in New York

.jpg)

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Niña con flores amarillas , executed in 1950 . 15 ¼ x 11 in (38.7 x 27.9 cm). Sold for $106,250 on 20-21 November 2018 at Christie’s in New York

In Portrait of Inesita Martinez , one is struck by the subject’s inquisitive eyes; while the girl in Niña con muñeca de trapo sits on a humble chair, holding a shawl-wrapped doll with all the affection that a mother might embrace her baby.

Workers and labourers feature in a large number of Rivera’s works too, as symbols of the noble toil of ordinary Mexicans who’d formed the backbone of their nation for centuries.

In his murals, whole fields or factories of people might be seen working en masse, while in easel paintings — such as Lavanderas con zopilotes , of two women bending their backs to wash clothes in a river — acts of labour tend to be isolated.

The critical reception for Rivera

Rivera died in 1957, aged 70. For most of his life, he was hailed as a master. A biography, written soon after his death by Bertram D. Wolfe, was titled, entirely earnestly, The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera .

Over time, however, his reputation diminished. His brand of social realism fell out of fashion, as movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Pop art came to the fore. The artist came to be seen as something of a propagandist for Communism during the Cold War years.

Towards the end of the 20th century, his popularity was surpassed by that of his wife Frida Kahlo whose work was re-discovered amidst the backdrop of feminist and cultural theory.

‘Understandably, people associate Rivera with his murals, but there’s a real market for his other work, too’ — Virgilio Garza

‘The decline in Rivera's reputation since his death has been remarkable,’ wrote Marnham. ‘In an extraordinary twist of fate, one of the greatest artists of the 20th century is remembered… as merely the unsatisfactory husband of a feminist icon.’

He did receive a big retrospective (marking the centenary of his birth) in 1986, though, which started at the Detroit Institute of Arts before travelling to Philadelphia, Mexico City, Berlin and the Hayward Gallery in London.

As for the 21st-Century, there are signs that Rivera’s reputation is on the up again: in large part because of the more globalised notion of modernism that has developed (in contrast to the Euro-/US-centric notion of old). ‘I think there’s a proper appreciation nowadays,’ says Garza, ‘that Mexican muralism was the first major art movement born in the Americas.’

In recent years, Rivera’s work has appeared in a number of exhibitions alongside Kahlo’s, as well as one at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) alongside Picasso ’s. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art has also just announced it will stage a Rivera retrospective in 2020.

The market for works by Diego Rivera

Like his reputation in the art world as a whole, Rivera’s prices are on the rise. ‘The record-breaking sale of The Rivals was the clearest example of that,’ says Garza, ‘but not the only one’. Four of the top five prices for Rivera works at Christie’s have been achieved since 2015.

‘His Cubist pictures are largely all in public collections,’ Garza adds. ‘What we see at auction are the [post-1920] easel paintings and works on paper, which he produced to supplement his income from mural commissions.

Usually, these are colourful slices of Mexican life featuring, say, peasant children or huge bundles of calla lilies, his favourite flower, which proved popular with contemporary collectors from the United States. Rivera’s small-scale work tends to be more pleasant and less overtly political in subject-matter than his murals.

Sign up for Going Once, a weekly newsletter delivering our top stories and art market insights to your inbox

Another important factor to bear in mind with Rivera’s market is that, in 1959, the Mexican government declared all his art a ‘historic monument’ — essentially imposing strict restrictions on the ability to export it. A large chunk of his works had already left the country by that point, of course, but it does mean something of a limit on supply.

Is there a way in at lower price points? ‘Absolutely,’ says Garza. ‘I recommend the vibrant watercolours Rivera did on rice paper, many of which are exceptionally beautiful. Cargando alcatraces (Tres mujeres, una sentada) , featuring three women carrying calla lilies for sale, is a fine example. Likewise Niña con flores amarillas and Niño con alcatraces , from our upcoming (November 2018) sales.

‘Works on rice paper can range from as little as $20,000 up to $400,000. Understandably, people associate Rivera with his murals, but there’s a real market for his other work, too, that’s both strong and inclusive.’

Related departments

Related lots, related auctions, related content.

Diego Rivera: Renowned Artist Who Courted Controversy

FPG / Getty Images

- History Before Columbus

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Caribbean History

- Central American History

- South American History

- Mexican History

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

Diego Rivera was a talented Mexican painter associated with the muralist movement. A Communist, he was often criticized for creating paintings that were controversial. Along with Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siquieros, he is considered one of the “big three” most important Mexican muralists. Today he is remembered as much for his volatile marriage to fellow artist Frida Kahlo as he is for his art.

Early Years

Diego Rivera was born in 1886 in Guanajuato, Mexico. A naturally gifted artist, he began his formal art training at a young age, but it wasn’t until he went to Europe in 1907 that his talent truly began to blossom.

Europe, 1907-1921

During his stay in Europe, Rivera was exposed to cutting-edge avant-garde art. In Paris, he had a front-row seat to the development of the cubist movement, and in 1914 he met Pablo Picasso , who expressed admiration for the young Mexican’s work. He left Paris when World War I broke out and went to Spain, where he helped introduce cubism in Madrid. He traveled around Europe until 1921, visiting many regions, including southern France and Italy, and was influenced by the works of Cezanne and Renoir.

Return to Mexico

When he returned home to Mexico, Rivera soon found work for the new revolutionary government. Secretary of Public Education Jose Vasconcelos believed in education through public art, and he commissioned several murals on government buildings by Rivera, as well as fellow painters Siquieros and Orozco. The beauty and artistic depth of the paintings gained Rivera and his fellow muralists international acclaim.

International Work

Rivera’s fame earned him commissions to paint in other countries besides Mexico. He traveled to the Soviet Union in 1927 as part of a delegation of Mexican Communists. He painted murals at the California School of Fine Arts, the American Stock Exchange Luncheon Club and the Detroit Institute of the Arts, and another was commissioned for Rockefeller Center in New York. However, it was never completed because of a controversy over Rivera’s inclusion of the image of Vladimir Lenin in the work. Although his stay in the United States was short, he is considered a major influence on American art.

Political Activism

Rivera returned to Mexico, where he resumed the life of a politically active artist. He was instrumental in the defection of Leon Trotsky from the Soviet Union to Mexico; Trotsky even lived with Rivera and Kahlo for a time. He continued to court controversy; one of his murals, at the Hotel del Prado, contained the phrase “God does not exist” and was hidden from view for years. Another, this one at the Palace of Fine Arts, was removed because it included images of Stalin and Mao Tse-tung.

Marriage to Kahlo

Rivera met Kahlo , a promising art student, in 1928; they married the next year. The mixture of the fiery Kahlo and the dramatic Rivera would prove to be a volatile one. They each had numerous extramarital affairs and fought often. Rivera even had a fling with Kahlo's sister Cristina. Rivera and Kahlo divorced in 1940 but remarried later the same year.

Final Years

Although their relationship had been stormy, Rivera was devastated by the death of Kahlo in 1954. He never really recovered, falling ill not long afterward. Although weak, he continued to paint and even remarried. He died of heart failure in 1957.

Rivera is considered the greatest of the Mexican muralists, an art form that was imitated around the world. His influence in the United States is significant: His paintings in the 1930s directly influenced President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s work programs, and hundreds of American artists began creating public art with a conscience. His smaller works are extremely valuable, and many are on display in museums around the globe.

- 7 Major Painting Styles—From Realism to Abstract

- Biography of Frida Kahlo, Mexican Surrealist and Folk Art Painter

- Painterly Places: A Look at the Homes of Artists

- Frida Kahlo Quotes

- The Most Influential Mexicans Since Independence

- 7 Famous People in Mexican History

- What Is Ekphrastic Poetry?

- Biography of Thomas Hart Benton, Painter of American Life

- Romare Bearden

- Biography of Jackson Pollock

- Sigmar Polke, German Pop Artist and Photographer

- Robert Henri, American Realist Painter of the Ashcan School

- Biography of Robert Delaunay, French Abstract Painter

- The Life and Art of John Singer Sargent

- Henri Matisse: His Life and Work

- Life and Work of Gerhard Richter, Abstract and Photorealistic Artist

The Cubist Paintings of Diego Rivera: Memory, Politics, Place

Introduction

Diego María Rivera (1886-1957) is one of the most prominent Mexican artists of the twentieth century. He gained international acclaim as a leader of the Mexican mural movement that sought to bring art to the masses through large-scale works on public walls. In his murals of the 1920s and 1930s Rivera developed a new, modern imagery to express Mexican national identity, which featured stylized representations of the working classes and indigenous cultures and espoused revolutionary ideals. This exhibition highlights Rivera's early foray into cubism, a less known but profoundly important aspect of the artist's development, in which his interest in themes of nationalism and politics first emerges. Featuring twenty-one works created in France and Spain between 1913 and 1915, the selection celebrates the National Gallery's No. 9, Spanish Still Life, 1915, recently bequeathed by Katharine Graham.

During his time abroad, Rivera drew upon the radical innovations of cubism, inaugurated a few years earlier by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Rivera adopted their dramatic fracturing of form, use of multiple perspective points, and flattening of the picture plane, and also borrowed favorite cubist motifs, such as liqueur bottles, musical instruments, and painted wood grain. Yet Rivera's cubism is formally and thematically distinctive. Characterized by brighter colors and a larger scale than many early cubist pictures, his work also features highly textured surfaces executed in a variety of techniques. The paintings on view, produced during a period that coincided with both the Mexican Revolution and World War I, reflect Rivera's expatriate role and explore issues of national identity. Many incorporate souvenirs of Mexico from afar and are infused with revolutionary sympathy and nostalgia. But these references to his native land are often embedded within canvases that refer to new Spanish, French, or Russian allegiances.

Images © 2004 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Av. Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

No. 9, Nature Morte Espagnole , 1915, oil on canvas, Gift of Katharine Graham, 2002.19.1

Rivera's Early Life

Diego Rivera was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, in December 1886, and moved with his family to Mexico City in the early 1890s. Rivera's parents, both educators, were part of the Europeanized professional classes that emerged under the Porfiriato, the lengthy dictatorial regime of President Porfirio Díaz. His prodigious talent was recognized at an early age, and by twelve he was enrolled in the national school of fine arts. Upon completion of his degree, Rivera was awarded a governmental stipend to further his career in art by traveling to Europe. With these funds, he sailed for Spain in January 1907. Remaining in Madrid for more than two years, Rivera studied with the Spanish academic painter Eduardo Chicharro, while assiduously copying from the collections of the Museo del Prado, and over time becoming part of the city's bohemian avant-garde.

In 1909 Rivera embarked on an itinerary of art study in Europe that included visits to Paris, London, and Belgium. In Bruges he met the Russian painter Angelina Beloff, who soon became his companion and common-law wife, and together they moved to Paris. (The two remained a couple until Rivera departed for Mexico in 1921. He married the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo in 1929.) Rivera returned to Mexico for a one-man exhibition of his work that opened on November 20, 1910, a date notorious for its association with the start of the Mexican Revolution. Shortly after the December 20 close of his exhibition, Rivera again departed for Europe; it would be more than a decade--and following the end of the Revolution--before he returned to Mexico. Years later, embarrassed by his lack of revolutionary credentials, the artist claimed to have participated in the fighting, boasting that he had joined Emiliano Zapata's peasant forces and even plotted to kill President Díaz. In truth, Rivera and Beloff spent the next few years working in Spain and France, engaged with neither the strife in Mexico nor with the cubist revolution in art that had been initiated by Picasso and Braque. As his close friend and the subject of Portrait of Martín Luis Guzmán would write, Rivera "arrived calmly and late" to cubism.

Portrait of Martín Luis Guzmán, 1915, oil on canvas, Fundación Televisa, A.C. Mexico City

Montparnasse, Paris

In fall of 1912 Rivera and Beloff established themselves in a studio in Montparnasse, at the heart of bohemian Paris. This left-bank district was rapidly becoming the axis of a cultural vanguard from around the world. There, as the poet Guillaume Apollinaire declared, you could "now find the real artists." Indeed, Picasso took a Montparnasse studio in October 1912, and Rivera's neighbors at 26, rue du Départ included the Dutch modernist Piet Mondrian. The avant-garde debates that fueled cubism proliferated in the cafés that Rivera began to frequent. There he made acquaintances including French artists Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger, Italian Amedeo Modigliani, Japanese painter Tsuguharu Foujita, Polish painter Leopold Gottlieb, Lithuanian painter Chaim Soutine, and the Russian Marc Chagall. Rivera's exposure to what Marcel Duchamp termed "the first really international colony of artists" soon began to inform his work, with Montparnasse--particularly his own studio there--as a prominent new motif.

The commanding fall 1913 painting of fellow Mexican artist Adolfo Best Maugard with a view of the Gare Montparnasse from Rivera's studio can be considered as much an homage to his new home as a portrait of his friend. Maugard is pictured as a strikingly elegant figure, shown gesturing to the Great Ferris Wheel, which was built in 1900 for the Paris World's Fair. The wheel seems to rotate around Maugard's gloved hand; below the sweep of his coat follows the movement of a train rendered in a series of static planes. In situating his friend as integrally related to and yet distanced from these emblems of Paris, Rivera offers a meditation on their common identity as expatriates--at once part of and removed from the place in which they live. The expression of geographical displacement and multiple allegiances would be enduring themes in Rivera's work of the period.

Shortly before the portrait was executed, Maugard visited the Spanish city of Toledo with Rivera and wrote of their admiration of the works of El Greco there. He noted that the sixteenth-century master's influence was strongly felt in Rivera's recent paintings, "especially his series of women with water jugs and landscapes with dramatic skys." The Woman at the Well of later that year--with the expressive pathos of the woman, her simplified drapery, and the stylization of her weighty curving form (which rhymes with the jar and the well)--also subtly recalls El Greco. Painted in Paris, the work thus intimates Rivera's reminiscences of the Moorish-Gothic city.

(left) Retrato de Adolfo Best Maugard (Portrait of Adolfo Best Maugard), 1913, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional de Arte, CONACULTA, INBA, Mexico City

(right) La mujer del pozo (The Woman at the Well), 1913, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional de Arte, CONACULTA, INBA, Mexico City. Verso of Paisaje Zapatista (Zapatista Landscape)

Sojourn to Spain

In The Woman at the Well the artist incorporates a colorful bird form, suggestively Mesoamerican in appearance, which serves as a reminder of Mexico within this Spanish scene. This choice was perhaps influenced by his friend Maugard, who was documenting Mexican archaeological objects in Paris museums. The earthenware jugs, which became a favorite motif in Rivera's Toledan paintings, resemble ancient Mexican ones; for Rivera the similarity may have forged a resonant link between the Spanish city and his homeland. Memory operates as an underlying theme in other ways too: the woman and her water jar are rendered in sequential planes that suggest the passage of time. This synthesis of seen and remembered elements suggests Rivera's absorption of the philosophies of Henri Bergson, which were popular among the avant-garde in the early twentieth century. According to Bergson, individual consciousness is a melding of sensory perception, memories of the past, and anticipation of the future. Thus, there is no objective reality, only subjective understanding filtered through our experiences.