The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

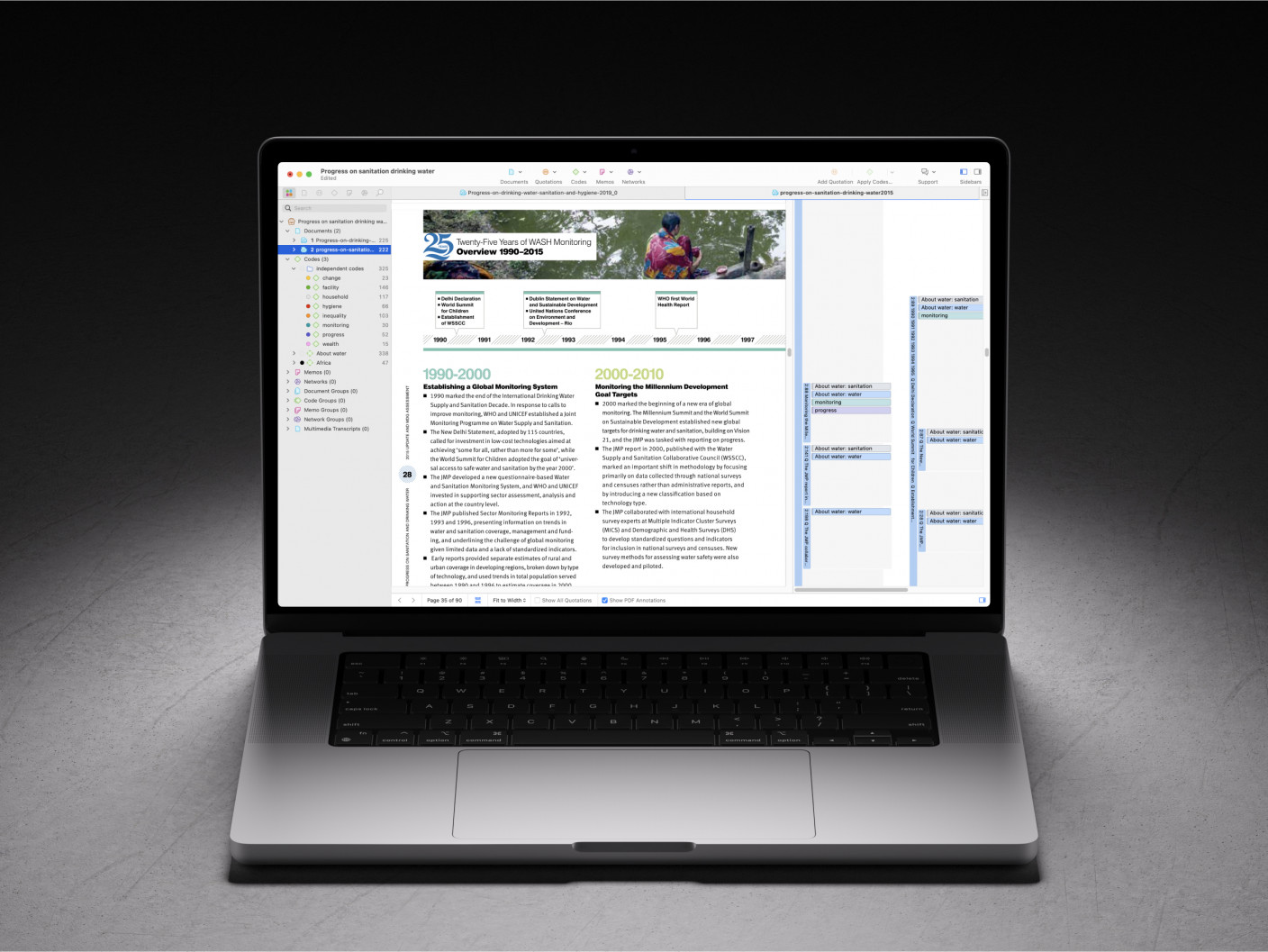

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

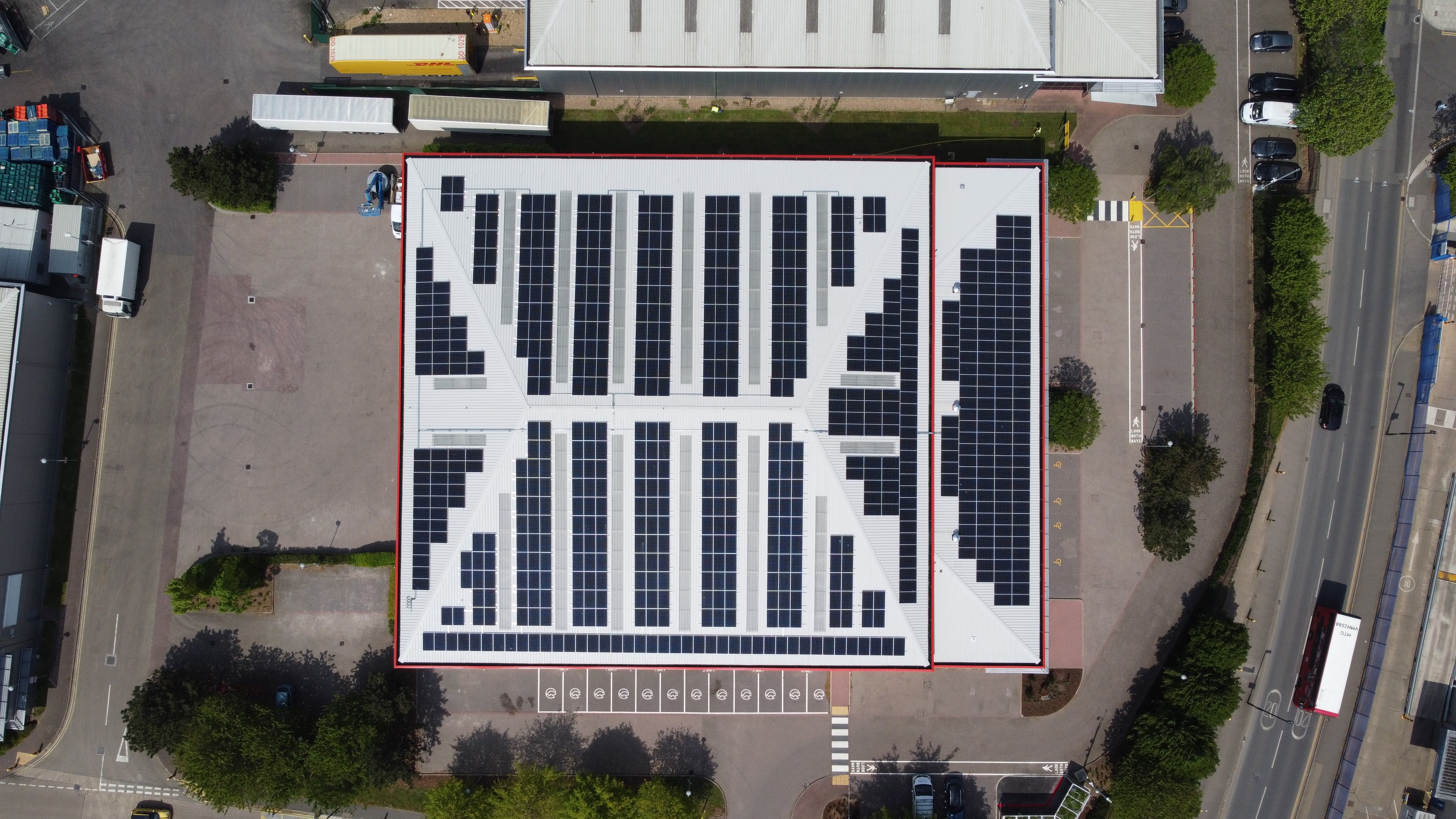

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved July 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sage Choice

Continuing to enhance the quality of case study methodology in health services research

Shannon l. sibbald.

1 Faculty of Health Sciences, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

2 Department of Family Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

3 The Schulich Interfaculty Program in Public Health, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

Stefan Paciocco

Meghan fournie, rachelle van asseldonk, tiffany scurr.

Case study methodology has grown in popularity within Health Services Research (HSR). However, its use and merit as a methodology are frequently criticized due to its flexible approach and inconsistent application. Nevertheless, case study methodology is well suited to HSR because it can track and examine complex relationships, contexts, and systems as they evolve. Applied appropriately, it can help generate information on how multiple forms of knowledge come together to inform decision-making within healthcare contexts. In this article, we aim to demystify case study methodology by outlining its philosophical underpinnings and three foundational approaches. We provide literature-based guidance to decision-makers, policy-makers, and health leaders on how to engage in and critically appraise case study design. We advocate that researchers work in collaboration with health leaders to detail their research process with an aim of strengthening the validity and integrity of case study for its continued and advanced use in HSR.

Introduction

The popularity of case study research methodology in Health Services Research (HSR) has grown over the past 40 years. 1 This may be attributed to a shift towards the use of implementation research and a newfound appreciation of contextual factors affecting the uptake of evidence-based interventions within diverse settings. 2 Incorporating context-specific information on the delivery and implementation of programs can increase the likelihood of success. 3 , 4 Case study methodology is particularly well suited for implementation research in health services because it can provide insight into the nuances of diverse contexts. 5 , 6 In 1999, Yin 7 published a paper on how to enhance the quality of case study in HSR, which was foundational for the emergence of case study in this field. Yin 7 maintains case study is an appropriate methodology in HSR because health systems are constantly evolving, and the multiple affiliations and diverse motivations are difficult to track and understand with traditional linear methodologies.

Despite its increased popularity, there is debate whether a case study is a methodology (ie, a principle or process that guides research) or a method (ie, a tool to answer research questions). Some criticize case study for its high level of flexibility, perceiving it as less rigorous, and maintain that it generates inadequate results. 8 Others have noted issues with quality and consistency in how case studies are conducted and reported. 9 Reporting is often varied and inconsistent, using a mix of approaches such as case reports, case findings, and/or case study. Authors sometimes use incongruent methods of data collection and analysis or use the case study as a default when other methodologies do not fit. 9 , 10 Despite these criticisms, case study methodology is becoming more common as a viable approach for HSR. 11 An abundance of articles and textbooks are available to guide researchers through case study research, including field-specific resources for business, 12 , 13 nursing, 14 and family medicine. 15 However, there remains confusion and a lack of clarity on the key tenets of case study methodology.

Several common philosophical underpinnings have contributed to the development of case study research 1 which has led to different approaches to planning, data collection, and analysis. This presents challenges in assessing quality and rigour for researchers conducting case studies and stakeholders reading results.

This article discusses the various approaches and philosophical underpinnings to case study methodology. Our goal is to explain it in a way that provides guidance for decision-makers, policy-makers, and health leaders on how to understand, critically appraise, and engage in case study research and design, as such guidance is largely absent in the literature. This article is by no means exhaustive or authoritative. Instead, we aim to provide guidance and encourage dialogue around case study methodology, facilitating critical thinking around the variety of approaches and ways quality and rigour can be bolstered for its use within HSR.

Purpose of case study methodology

Case study methodology is often used to develop an in-depth, holistic understanding of a specific phenomenon within a specified context. 11 It focuses on studying one or multiple cases over time and uses an in-depth analysis of multiple information sources. 16 , 17 It is ideal for situations including, but not limited to, exploring under-researched and real-life phenomena, 18 especially when the contexts are complex and the researcher has little control over the phenomena. 19 , 20 Case studies can be useful when researchers want to understand how interventions are implemented in different contexts, and how context shapes the phenomenon of interest.

In addition to demonstrating coherency with the type of questions case study is suited to answer, there are four key tenets to case study methodologies: (1) be transparent in the paradigmatic and theoretical perspectives influencing study design; (2) clearly define the case and phenomenon of interest; (3) clearly define and justify the type of case study design; and (4) use multiple data collection sources and analysis methods to present the findings in ways that are consistent with the methodology and the study’s paradigmatic base. 9 , 16 The goal is to appropriately match the methods to empirical questions and issues and not to universally advocate any single approach for all problems. 21

Approaches to case study methodology

Three authors propose distinct foundational approaches to case study methodology positioned within different paradigms: Yin, 19 , 22 Stake, 5 , 23 and Merriam 24 , 25 ( Table 1 ). Yin is strongly post-positivist whereas Stake and Merriam are grounded in a constructivist paradigm. Researchers should locate their research within a paradigm that explains the philosophies guiding their research 26 and adhere to the underlying paradigmatic assumptions and key tenets of the appropriate author’s methodology. This will enhance the consistency and coherency of the methods and findings. However, researchers often do not report their paradigmatic position, nor do they adhere to one approach. 9 Although deliberately blending methodologies may be defensible and methodologically appropriate, more often it is done in an ad hoc and haphazard way, without consideration for limitations.

Cross-analysis of three case study approaches, adapted from Yazan 2015

| Dimension of interest | Yin | Stake | Merriam |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case study design | Logical sequence = connecting empirical data to initial research question Four types: single holistic, single embedded, multiple holistic, multiple embedded | Flexible design = allow major changes to take place while the study is proceeding | Theoretical framework = literature review to mold research question and emphasis points |

| Case study paradigm | Positivism | Constructivism and existentialism | Constructivism |

| Components of study | “Progressive focusing” = “the course of the study cannot be charted in advance” (1998, p 22) Must have 2-3 research questions to structure the study | ||

| Collecting data | Quantitative and qualitative evidentiary influenced by: | Qualitative data influenced by: | Qualitative data research must have necessary skills and follow certain procedures to: |

| Data collection techniques | |||

| Data analysis | Use both quantitative and qualitative techniques to answer research question | Use researcher’s intuition and impression as a guiding factor for analysis | “it is the process of making meaning” (1998, p 178) |

| Validating data | Use triangulation | Increase internal validity Ensure reliability and increase external validity |

The post-positive paradigm postulates there is one reality that can be objectively described and understood by “bracketing” oneself from the research to remove prejudice or bias. 27 Yin focuses on general explanation and prediction, emphasizing the formulation of propositions, akin to hypothesis testing. This approach is best suited for structured and objective data collection 9 , 11 and is often used for mixed-method studies.

Constructivism assumes that the phenomenon of interest is constructed and influenced by local contexts, including the interaction between researchers, individuals, and their environment. 27 It acknowledges multiple interpretations of reality 24 constructed within the context by the researcher and participants which are unlikely to be replicated, should either change. 5 , 20 Stake and Merriam’s constructivist approaches emphasize a story-like rendering of a problem and an iterative process of constructing the case study. 7 This stance values researcher reflexivity and transparency, 28 acknowledging how researchers’ experiences and disciplinary lenses influence their assumptions and beliefs about the nature of the phenomenon and development of the findings.

Defining a case

A key tenet of case study methodology often underemphasized in literature is the importance of defining the case and phenomenon. Researches should clearly describe the case with sufficient detail to allow readers to fully understand the setting and context and determine applicability. Trying to answer a question that is too broad often leads to an unclear definition of the case and phenomenon. 20 Cases should therefore be bound by time and place to ensure rigor and feasibility. 6

Yin 22 defines a case as “a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context,” (p13) which may contain a single unit of analysis, including individuals, programs, corporations, or clinics 29 (holistic), or be broken into sub-units of analysis, such as projects, meetings, roles, or locations within the case (embedded). 30 Merriam 24 and Stake 5 similarly define a case as a single unit studied within a bounded system. Stake 5 , 23 suggests bounding cases by contexts and experiences where the phenomenon of interest can be a program, process, or experience. However, the line between the case and phenomenon can become muddy. For guidance, Stake 5 , 23 describes the case as the noun or entity and the phenomenon of interest as the verb, functioning, or activity of the case.

Designing the case study approach

Yin’s approach to a case study is rooted in a formal proposition or theory which guides the case and is used to test the outcome. 1 Stake 5 advocates for a flexible design and explicitly states that data collection and analysis may commence at any point. Merriam’s 24 approach blends both Yin and Stake’s, allowing the necessary flexibility in data collection and analysis to meet the needs.

Yin 30 proposed three types of case study approaches—descriptive, explanatory, and exploratory. Each can be designed around single or multiple cases, creating six basic case study methodologies. Descriptive studies provide a rich description of the phenomenon within its context, which can be helpful in developing theories. To test a theory or determine cause and effect relationships, researchers can use an explanatory design. An exploratory model is typically used in the pilot-test phase to develop propositions (eg, Sibbald et al. 31 used this approach to explore interprofessional network complexity). Despite having distinct characteristics, the boundaries between case study types are flexible with significant overlap. 30 Each has five key components: (1) research question; (2) proposition; (3) unit of analysis; (4) logical linking that connects the theory with proposition; and (5) criteria for analyzing findings.

Contrary to Yin, Stake 5 believes the research process cannot be planned in its entirety because research evolves as it is performed. Consequently, researchers can adjust the design of their methods even after data collection has begun. Stake 5 classifies case studies into three categories: intrinsic, instrumental, and collective/multiple. Intrinsic case studies focus on gaining a better understanding of the case. These are often undertaken when the researcher has an interest in a specific case. Instrumental case study is used when the case itself is not of the utmost importance, and the issue or phenomenon (ie, the research question) being explored becomes the focus instead (eg, Paciocco 32 used an instrumental case study to evaluate the implementation of a chronic disease management program). 5 Collective designs are rooted in an instrumental case study and include multiple cases to gain an in-depth understanding of the complexity and particularity of a phenomenon across diverse contexts. 5 , 23 In collective designs, studying similarities and differences between the cases allows the phenomenon to be understood more intimately (for examples of this in the field, see van Zelm et al. 33 and Burrows et al. 34 In addition, Sibbald et al. 35 present an example where a cross-case analysis method is used to compare instrumental cases).

Merriam’s approach is flexible (similar to Stake) as well as stepwise and linear (similar to Yin). She advocates for conducting a literature review before designing the study to better understand the theoretical underpinnings. 24 , 25 Unlike Stake or Yin, Merriam proposes a step-by-step guide for researchers to design a case study. These steps include performing a literature review, creating a theoretical framework, identifying the problem, creating and refining the research question(s), and selecting a study sample that fits the question(s). 24 , 25 , 36

Data collection and analysis

Using multiple data collection methods is a key characteristic of all case study methodology; it enhances the credibility of the findings by allowing different facets and views of the phenomenon to be explored. 23 Common methods include interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. 5 , 37 By seeking patterns within and across data sources, a thick description of the case can be generated to support a greater understanding and interpretation of the whole phenomenon. 5 , 17 , 20 , 23 This technique is called triangulation and is used to explore cases with greater accuracy. 5 Although Stake 5 maintains case study is most often used in qualitative research, Yin 17 supports a mix of both quantitative and qualitative methods to triangulate data. This deliberate convergence of data sources (or mixed methods) allows researchers to find greater depth in their analysis and develop converging lines of inquiry. For example, case studies evaluating interventions commonly use qualitative interviews to describe the implementation process, barriers, and facilitators paired with a quantitative survey of comparative outcomes and effectiveness. 33 , 38 , 39

Yin 30 describes analysis as dependent on the chosen approach, whether it be (1) deductive and rely on theoretical propositions; (2) inductive and analyze data from the “ground up”; (3) organized to create a case description; or (4) used to examine plausible rival explanations. According to Yin’s 40 approach to descriptive case studies, carefully considering theory development is an important part of study design. “Theory” refers to field-relevant propositions, commonly agreed upon assumptions, or fully developed theories. 40 Stake 5 advocates for using the researcher’s intuition and impression to guide analysis through a categorical aggregation and direct interpretation. Merriam 24 uses six different methods to guide the “process of making meaning” (p178) : (1) ethnographic analysis; (2) narrative analysis; (3) phenomenological analysis; (4) constant comparative method; (5) content analysis; and (6) analytic induction.

Drawing upon a theoretical or conceptual framework to inform analysis improves the quality of case study and avoids the risk of description without meaning. 18 Using Stake’s 5 approach, researchers rely on protocols and previous knowledge to help make sense of new ideas; theory can guide the research and assist researchers in understanding how new information fits into existing knowledge.

Practical applications of case study research

Columbia University has recently demonstrated how case studies can help train future health leaders. 41 Case studies encompass components of systems thinking—considering connections and interactions between components of a system, alongside the implications and consequences of those relationships—to equip health leaders with tools to tackle global health issues. 41 Greenwood 42 evaluated Indigenous peoples’ relationship with the healthcare system in British Columbia and used a case study to challenge and educate health leaders across the country to enhance culturally sensitive health service environments.

An important but often omitted step in case study research is an assessment of quality and rigour. We recommend using a framework or set of criteria to assess the rigour of the qualitative research. Suitable resources include Caelli et al., 43 Houghten et al., 44 Ravenek and Rudman, 45 and Tracy. 46

New directions in case study

Although “pragmatic” case studies (ie, utilizing practical and applicable methods) have existed within psychotherapy for some time, 47 , 48 only recently has the applicability of pragmatism as an underlying paradigmatic perspective been considered in HSR. 49 This is marked by uptake of pragmatism in Randomized Control Trials, recognizing that “gold standard” testing conditions do not reflect the reality of clinical settings 50 , 51 nor do a handful of epistemologically guided methodologies suit every research inquiry.

Pragmatism positions the research question as the basis for methodological choices, rather than a theory or epistemology, allowing researchers to pursue the most practical approach to understanding a problem or discovering an actionable solution. 52 Mixed methods are commonly used to create a deeper understanding of the case through converging qualitative and quantitative data. 52 Pragmatic case study is suited to HSR because its flexibility throughout the research process accommodates complexity, ever-changing systems, and disruptions to research plans. 49 , 50 Much like case study, pragmatism has been criticized for its flexibility and use when other approaches are seemingly ill-fit. 53 , 54 Similarly, authors argue that this results from a lack of investigation and proper application rather than a reflection of validity, legitimizing the need for more exploration and conversation among researchers and practitioners. 55

Although occasionally misunderstood as a less rigourous research methodology, 8 case study research is highly flexible and allows for contextual nuances. 5 , 6 Its use is valuable when the researcher desires a thorough understanding of a phenomenon or case bound by context. 11 If needed, multiple similar cases can be studied simultaneously, or one case within another. 16 , 17 There are currently three main approaches to case study, 5 , 17 , 24 each with their own definitions of a case, ontological and epistemological paradigms, methodologies, and data collection and analysis procedures. 37

Individuals’ experiences within health systems are influenced heavily by contextual factors, participant experience, and intricate relationships between different organizations and actors. 55 Case study research is well suited for HSR because it can track and examine these complex relationships and systems as they evolve over time. 6 , 7 It is important that researchers and health leaders using this methodology understand its key tenets and how to conduct a proper case study. Although there are many examples of case study in action, they are often under-reported and, when reported, not rigorously conducted. 9 Thus, decision-makers and health leaders should use these examples with caution. The proper reporting of case studies is necessary to bolster their credibility in HSR literature and provide readers sufficient information to critically assess the methodology. We also call on health leaders who frequently use case studies 56 – 58 to report them in the primary research literature.

The purpose of this article is to advocate for the continued and advanced use of case study in HSR and to provide literature-based guidance for decision-makers, policy-makers, and health leaders on how to engage in, read, and interpret findings from case study research. As health systems progress and evolve, the application of case study research will continue to increase as researchers and health leaders aim to capture the inherent complexities, nuances, and contextual factors. 7

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Basic Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Correlational Research – Methods, Types and...

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Ethnographic Research -Types, Methods and Guide

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

- Foundations

- Write Paper

Search form

- Experiments

- Anthropology

- Self-Esteem

- Social Anxiety

Case Study Research Design

The case study research design have evolved over the past few years as a useful tool for investigating trends and specific situations in many scientific disciplines.

This article is a part of the guide:

- Research Designs

- Quantitative and Qualitative Research

- Literature Review

- Quantitative Research Design

- Descriptive Research

Browse Full Outline

- 1 Research Designs

- 2.1 Pilot Study

- 2.2 Quantitative Research Design

- 2.3 Qualitative Research Design

- 2.4 Quantitative and Qualitative Research

- 3.1 Case Study

- 3.2 Naturalistic Observation

- 3.3 Survey Research Design

- 3.4 Observational Study

- 4.1 Case-Control Study

- 4.2 Cohort Study

- 4.3 Longitudinal Study

- 4.4 Cross Sectional Study

- 4.5 Correlational Study

- 5.1 Field Experiments

- 5.2 Quasi-Experimental Design

- 5.3 Identical Twins Study

- 6.1 Experimental Design

- 6.2 True Experimental Design

- 6.3 Double Blind Experiment

- 6.4 Factorial Design

- 7.1 Literature Review

- 7.2 Systematic Reviews

- 7.3 Meta Analysis

The case study has been especially used in social science, psychology, anthropology and ecology.

This method of study is especially useful for trying to test theoretical models by using them in real world situations. For example, if an anthropologist were to live amongst a remote tribe, whilst their observations might produce no quantitative data, they are still useful to science.

What is a Case Study?

Basically, a case study is an in depth study of a particular situation rather than a sweeping statistical survey . It is a method used to narrow down a very broad field of research into one easily researchable topic.

Whilst it will not answer a question completely, it will give some indications and allow further elaboration and hypothesis creation on a subject.

The case study research design is also useful for testing whether scientific theories and models actually work in the real world. You may come out with a great computer model for describing how the ecosystem of a rock pool works but it is only by trying it out on a real life pool that you can see if it is a realistic simulation.

For psychologists, anthropologists and social scientists they have been regarded as a valid method of research for many years. Scientists are sometimes guilty of becoming bogged down in the general picture and it is sometimes important to understand specific cases and ensure a more holistic approach to research .

H.M.: An example of a study using the case study research design.

The Argument for and Against the Case Study Research Design

Some argue that because a case study is such a narrow field that its results cannot be extrapolated to fit an entire question and that they show only one narrow example. On the other hand, it is argued that a case study provides more realistic responses than a purely statistical survey.

The truth probably lies between the two and it is probably best to try and synergize the two approaches. It is valid to conduct case studies but they should be tied in with more general statistical processes.

For example, a statistical survey might show how much time people spend talking on mobile phones, but it is case studies of a narrow group that will determine why this is so.

The other main thing to remember during case studies is their flexibility. Whilst a pure scientist is trying to prove or disprove a hypothesis , a case study might introduce new and unexpected results during its course, and lead to research taking new directions.

The argument between case study and statistical method also appears to be one of scale. Whilst many 'physical' scientists avoid case studies, for psychology, anthropology and ecology they are an essential tool. It is important to ensure that you realize that a case study cannot be generalized to fit a whole population or ecosystem.

Finally, one peripheral point is that, when informing others of your results, case studies make more interesting topics than purely statistical surveys, something that has been realized by teachers and magazine editors for many years. The general public has little interest in pages of statistical calculations but some well placed case studies can have a strong impact.

How to Design and Conduct a Case Study

The advantage of the case study research design is that you can focus on specific and interesting cases. This may be an attempt to test a theory with a typical case or it can be a specific topic that is of interest. Research should be thorough and note taking should be meticulous and systematic.

The first foundation of the case study is the subject and relevance. In a case study, you are deliberately trying to isolate a small study group, one individual case or one particular population.

For example, statistical analysis may have shown that birthrates in African countries are increasing. A case study on one or two specific countries becomes a powerful and focused tool for determining the social and economic pressures driving this.

In the design of a case study, it is important to plan and design how you are going to address the study and make sure that all collected data is relevant. Unlike a scientific report, there is no strict set of rules so the most important part is making sure that the study is focused and concise; otherwise you will end up having to wade through a lot of irrelevant information.

It is best if you make yourself a short list of 4 or 5 bullet points that you are going to try and address during the study. If you make sure that all research refers back to these then you will not be far wrong.

With a case study, even more than a questionnaire or survey , it is important to be passive in your research. You are much more of an observer than an experimenter and you must remember that, even in a multi-subject case, each case must be treated individually and then cross case conclusions can be drawn .

How to Analyze the Results

Analyzing results for a case study tends to be more opinion based than statistical methods. The usual idea is to try and collate your data into a manageable form and construct a narrative around it.

Use examples in your narrative whilst keeping things concise and interesting. It is useful to show some numerical data but remember that you are only trying to judge trends and not analyze every last piece of data. Constantly refer back to your bullet points so that you do not lose focus.

It is always a good idea to assume that a person reading your research may not possess a lot of knowledge of the subject so try to write accordingly.

In addition, unlike a scientific study which deals with facts, a case study is based on opinion and is very much designed to provoke reasoned debate. There really is no right or wrong answer in a case study.

- Psychology 101

- Flags and Countries

- Capitals and Countries

Martyn Shuttleworth (Apr 1, 2008). Case Study Research Design. Retrieved Jul 14, 2024 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/case-study-research-design

You Are Allowed To Copy The Text

The text in this article is licensed under the Creative Commons-License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) .

This means you're free to copy, share and adapt any parts (or all) of the text in the article, as long as you give appropriate credit and provide a link/reference to this page.