Korean War: Classic Photos by David Douglas Duncan

Five years after the end of World War II, American soldiers were fighting again, the time in Korea. Here Marine Capt. Francis "Ike" Fenton pondered his fate and the fate of his men after being told that his company was nearly out of ammunition, 1950.

US Marine Captain Francis "Ike" Fenton in despair as he is told that his company is almost out of ammunition while trying to hold off a heavy counter-attack by North Korean forces. (Photo by David Douglas Duncan /The LIFE Images Collection)

Written By: Ben Cosgrove

Few people have lived as long, as varied and as complete a life as David Douglas Duncan. And certainly no photographers ever enjoyed a longer, more varied or more complete career than the Missouri native who became one of the indispensable photojournalists of the 20th century.

Born in Kansas City, Mo., on Jan. 23, 1916, Duncan started taking pictures for newspapers in the 1930s; joined the U.S. Marines after Pearl Harbor; made some of the most indelible photos to come out of World War II and, 20 years later, Vietnam. He documented civil strife and wars in Europe, Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and he captured extraordinary beauty in environments as disparate as the west of Ireland and the deserts of America’s Southwest. He befriended and photographed people such as Picasso and Cartier-Bresson, and he produced the single greatest portfolio of pictures to emerge from the Korean War.

Here, LIFE.com presents a gallery of his celebrated pictures from America’s “Forgotten War.”

Several years before his death in 2018 at age 102, LIFE.com spoke with Duncan about his memories of the conflict — and his hope, in the end, that he might “show something of what a man endures when his country decides to go to war.”

Of his photograph of a Marine captain near the Naktong River after an attack by North Korean troops as ammunition ran dangerously low and reinforcements were nowhere in sight Duncan had written in his 1951 book, This Is War! : “Ike Fenton, drenched and with the rain running in little droplets from his bearded chin, got the news. His tattered Baker Company Marines had only those few rounds in their belts remaining. If the Reds were to launch one more attack they would have to be stopped with bayonets and rifle butts.”

But that attack never came. The Marines held the muddy, blasted, blood-drenched hill. “Radio communication was knocked out by the rain that day,” Duncan told LIFE.com, the recollection still vivid more than six decades later, “and Fenton had to shout most of his orders and sent runners when shouting wouldn’t do. God, he was a cool one. He never lost his head.”

Pictures bring back visceral memories, and Duncan recounted the circumstances around the making of some of his classic photos in a voice at once firm and touched with wonder at the immediacy of his own recall; at the horrors and heroism he witnessed; at the fact that he was there, recording it all.

“I cabled LIFE’s editors in August [1950] from Tokyo,” Duncan said, “and I told them I was heading back to Korea to try and get what I called ‘a wordless story’ that conveyed the message, simply, ‘This is war.’ Not long after that I was covering the fighting near the Naktong River, and I made the picture of Marines running past a dead enemy soldier, their fatigues absolutely soaked to the chest with mud and muck and god knows what else. And this ended up as the cover image for the book, This Is War! , when it came out a year later.”

From the hellish heat of summer to the arctic freeze of winter, Duncan traveled with Marines, documenting the grinding, torturous lives they led and that troops everywhere have always led in war zones the world over.

“It was forty below zero during the retreat from Chosin Reservoir,” Duncan recalls of one especially appalling battle in the winter of 1950. “And the wind chill! The wind was barreling down from Manchuria and must have made it closer to fifty or sixty degrees below zero. It was so damn cold that my film was so brittle it just snapped, like a pretzel. But I managed to unload and load the camera under my gear and get some film in there, and I got some usable shots.”

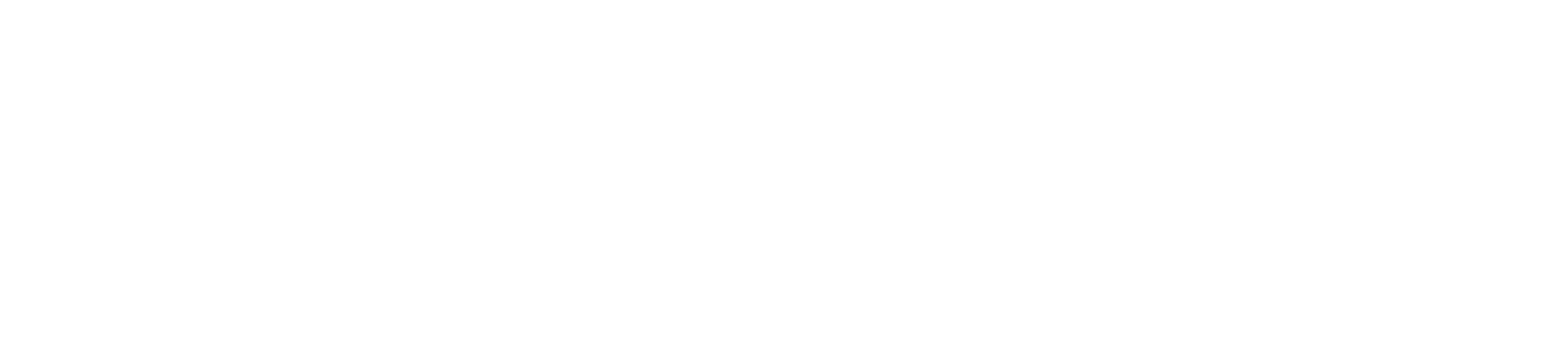

The two-week battle at Chosin, while ending with 30,000 United Nations troops fleeing from at least 60,000 Chinese soldiers that surrounded them, is seen as a decisive battle for one primary reason: it showed that outnumbered allied forces could battle through encircling enemy lines, while at the same time inflicting heavy casualties.

While recalling the unspeakable violence and gnawing deprivation of those years, Duncan makes a point of praising the Americans’ South Korean allies. “The thing that comes to mind right away, right now, when looking at these pictures again,” Duncan said, “is that at no time at no time did any Marine feel he had to look around to see what the South Koreans were doing behind him. The Marines in Korea never feared ‘friendly fire’ or artillery coming from the South Koreans from their allies like they did later in Vietnam, fighting with the South Vietnamese. The Koreans could be trusted.”

The Korean War lasted for roughly three years, from June 25, 1950 when North Korea invaded the South until July 27, 1953, when the United Nations Command, the North Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteers signed an armistice agreement. However, the South Korean president, Syngman Rhee, refused to sign the document meaning that, technically, North and South Korea remained at war.

Five years after the end of World War II, American soldiers were fighting again, the time in Korea. Here Marine Capt. Francis “Ike” Fenton pondered his fate and the fate of his men after being told that his company was nearly out of ammunition, 1950. David Douglas Duncan

American Marines raced past a dead enemy soldier in Korea, September 1950. David Douglas Duncan

Wounded when a mine blew up his Jeep, an ambulance driver sobbed by the side of the road after learning that a friend was killed in the blast, Korea 1950. David Douglas Duncan

“Corporal Leonard Hayworth … shows his utter frustration as he has crawled back from his position only to learn that the ammo is gone. Coda: At the last moment, supplies arrived and the men were able to hold their position.” From David Douglas Duncan’s 1951 book, This Is War! David Douglas Duncan

A wounded American Marine was carried on stretcher improvised from a machine gun, Korea 1950. David Douglas Duncan

A column of American Marines marched down a canyon road dubbed “Nightmare Alley” during their retreat from Chosin Reservoir, Korea, 1950. David Douglas Duncan

Marines retreated from the Chosin Reservoir, Korea, 1950. David Douglas Duncan

American Marines marched down a canyon road dubbed “Nightmare Alley” during their retreat from Chosin Reservoir, Korea, 1950. David Douglas Duncan

A weary American Marine hooded against the cold during the grim retreat from Chosin Reservoir, Korea, winter 1950. David Douglas Duncan

A weary, exhausted Marine huddled against the bitter cold during the retreat from Chosin Reservoir, Korea, winter 1950. David Douglas Duncan

A dazed, hooded Marine clutched a can of food during his outfit’s retreat from the Chosin Reservoir during the Korean War, December 1950. David Douglas Duncan

The fight for Seoul, Korea, 1950. David Douglas Duncan

“This,” Duncan told LIFE.com of a picture made during the fight for Seoul, “is the best picture I made in Korea of civilians—a family running down stairs, a father holding a baby, tanks firing away. Those tanks are taking fire from North Koreans right down the street!” David Douglas Duncan

An American Marine slept in his halted jeep while a puppy whined in his ear during the retreat from the Chosin Reservoir, December 1950. David Douglas Duncan

American Marines passed bodies of fallen comrades during the retreat from the Chosin Reservoir, December 1950. David Douglas Duncan

Marines rested after making it through the canyon road known as Nightmare Alley during the retreat from the Chosin Reservoir, December 1950. David Douglas Duncan

Marines filed past a truck loaded with dead troops during the retreat from the Chosin Reservoir, December 1950. David Douglas Duncan

LIFE photographer David Douglas Duncan in Korea. David Douglas Duncan

More Like This

Eisenstaedt in Postwar Italy (and Yes, That’s Pasta)

A Young Actress Restarts Her Life in Postwar Paris

Eisenstadt’s Images of Change in the Pacific Northwest

Heartland Cool: Teenage Boys in Iowa, 1945

LIFE Said This Invention Would “Annihilate Time and Space”

“The Synanon Fix” in LIFE

Subscribe to the life newsletter.

Travel back in time with treasured photos and stories, sent right to your inbox

| Subtotal | $0 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $0 |

The Korean War: Behind the Battlefront

On the 70th Anniversary of the Korean War Armistice, Werner Bischof’s work stands as a powerful reminder of the human cost of the conflict, which marked a pivotal moment in the photographer’s practice

Werner Bischof

On June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea, marking the start of the Korean War. What followed was a savage conflict that claimed the lives of millions. The invasion followed the intensification of low-level fighting, which had been taking place along the two countries’ temporary border for years. Korea had been divided at the 38th parallel following the end of World War II; the Soviet Army took hold of the North, while US forces established control in the South with a view to eventually unifying the country. Both occupying powers established civilian regimes. However, ongoing resistance from the Soviet Union and North Korea’s new leaders towards attempts at forming one government ensured that Korea remained split.

One year into the fighting, Werner Bischof journeyed to the region to investigate the human cost of the conflict, having just completed an assignment for Magnum in India. On the 70th anniversary of the armistice agreement that halted the hostilities and left Korea divided down a de facto boundary that still exists today, we look back at Bischof’s historic coverage of the war.

Bischof had been invited to join Magnum in 1948, following his extensive documentation of life across Europe in the aftermath of World War II. This was a transitional moment for the photographer who had received an art school training and originally intended to become a painter. Although he did not pursue this route, Bischof began his photographic career working in a studio, creating beautiful images dominated by natural forms and abstract shapes.

However, the experience of documenting post-war Europe made him question his role as a photographer and he became committed to using the medium as a tool for social change. He officially joined the agency in 1949, alongside its four founding members. Moving away from his fine art roots, Bischof continued to embrace a more photojournalistic approach and, from 1951 to 1952, dedicated himself to documenting social and political issues across Asia.

"His photographs had a tendency towards the absolute — a combination of beauty with truth"

- ernst haas.

The photographer’s first stop was India, where he worked on a number of projects including his renowned photo-essay Famine Story, which shed light on the severe famine ravaging the country. Bischof soon became set on traveling to Korea, determined to expose the suffering of civilians caught up in the war.

On the morning of July 5, 1951, he joined ten other correspondents from around the world on a flight to Seoul. “I just had to see for myself how this war was being conducted. (Something else was at play too: I found it important to show the human, the civilian side of the story. The Koreans who were chased out of their homes,)” he wrote in a letter to his wife, Rosellina Bischof, sent from Tokyo on July 11, 1951.

Arts & Culture

After the War

Despite making the transition to photojournalism, Bischof’s relationship with photography remained complex. He particularly struggled with the realities of being a photojournalist and was angered by the prevalence of, what he regarded as, sensationalistic and careless reporting. In the same letter to Rosellina he described his first impressions of Seoul: “Among these ruins, the press center shone as the sole lit block, hundreds of journalists. It seemed to me as if we were vultures on the battlefield, always out for the sensationalistic …” However, it was a desire to go beyond the shocking images strewn across newspapers’ front pages that drove him on. So, as he had done in India, and post-war Europe before, Bischof looked beyond the immediate and produced a poignant documentation of those behind the battlefront.

"It seemed to me as if we were vultures on the battlefield"

- werner bischof.

This deeper and more considered approach to reporting is a defining characteristic of Magnum photographers, but one that was shaped by Bischof’s artistic background too. “I always and in every way go too deep into the subject matter, and that is not journalistic,” he wrote in a letter to Robert Capa, sent from Tokyo on September 9, 1951.

His artistic roots had also equipped him with an appreciation of beauty, which Bischof translated from his studio work into his documentary practice, including the work he produced in Korea. “His photographs had a tendency towards the absolute — a combination of beauty with truth: a stone became a world, a child was all children, a war was all wars,” observed the photojournalist Ernst Haas, an early Magnum colleague.

Theory & Practice

100 Years of Werner Bischof

Magnum photographers.

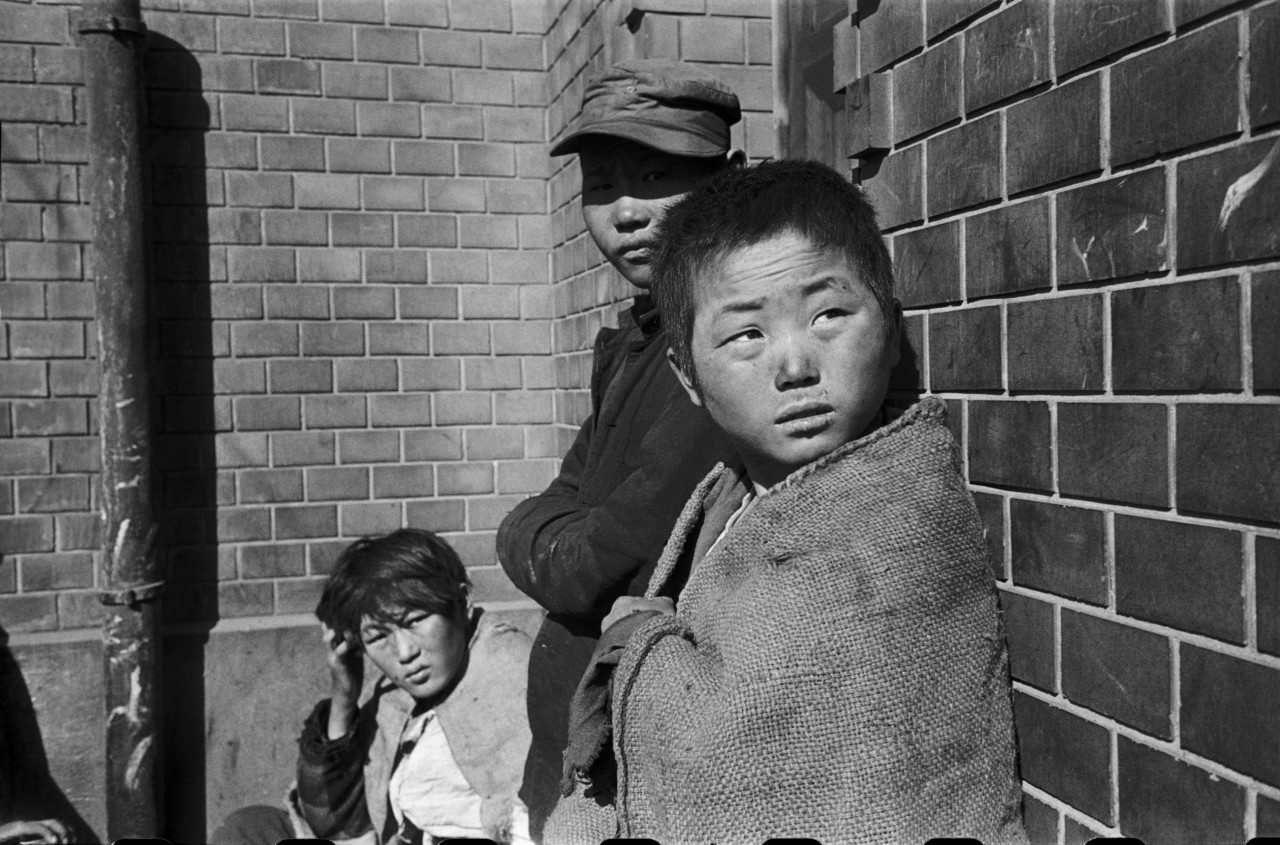

The Forgotten Village

After investigating war-torn Seoul, Bischof traveled to Sanyang-ri, a small village nestled in one of the many valleys of central Korea; an area that had become a no man’s land for troops in battle. “Not a single native Korean male is tolerated in this war zone, not a woman, not a child, only soldiers,” observed Bischof in the report for Magnum Photos, dated July 8, 1951, which he wrote to accompany his images. Bischof accompanied a small Civil Assistance group as they evacuated the inhabitants of this forgotten village. As was the photographer’s intention, the resulting photo story sheds light on the harsh realities for civilians caught up in the conflict.

In his report, Bischof described the desperate scenes he encountered: starving and ill civilians, many of whom were reluctant to leave their homes. The Civil Assistance group moved from house to house, providing clothes, food and medical help. Bischof followed, photographing and making notes as the team evacuated the village and brought its inhabitants to a nearby rendezvous , where they received further assistance.

“In front of another house, a small skeletal body sits in the dazzling sunlight, crouches naked on the floor, absolutely covered in flies. Near to her, her sixteen-year-old brother is unable to use his limbs. A shaven-headed figure in the hut takes no notice. We think it is a child, but the interpreter says it is a thirty-year-old woman,” reads an excerpt from the report.

Escape From North Korea

Chien-chi chang.

Prisoner’s Island

In January 1952 Bischof reluctantly traveled to Koje-Do Island in South Korea to document a United Nations re-education camp for Chinese and North Korean prisoners. On hearing the news that a number of prisoners had been shot, a colleague he was traveling with urged him to go. “I was against it, but John thought it very important — so we flew off, as if it were a Sunday excursion, journalists from around the world, joking cheerful,” he wrote.

The camp was spread over a large area spanning two valleys and was home to around 160,000 North Korean and Chinese prisoners at its height. Journalists were able to explore relatively freely, but were prohibited from talking to inmates.

The Photographs of Early Magnum Member Werner Bischof

"we cannot deny that what we are doing here is political manipulation".

Bischof characteristically focused on the prisoners, creating a series of images documenting their everyday lives and the United Nations attempts at reeducating them. His writing from the trip sheds light on his critical views of the situation: “We cannot deny that what we are doing here is political manipulation and an attempt to make these people grasp the ideas behind our own view of life.”

The photo story was subsequently published in LIFE in March 1952. Bischof’s negative reception of the editors’ selection of images reflected his issues with photojournalism more broadly: “It is difficult to take photographs in a prison camp, to hold onto your humanity, and subsequently to have the best pictures discarded by the censors. I sometimes ask myself whether I have become just another “reporter,” a word that I have always hated so much.”

Werner Bischof: In His Nature

Bischof was deeply affected by the suffering he witnessed in Korea. His images stand as a powerful testament to the massive civilian cost of the war, which remains unresolved to this day. Following his work in Korea, Bischof went on to spend five months in Japan, before traveling to Hong Kong, and then on to Indochina. He remained committed to photography until his untimely death in a road accident in the Andes on the May 16, 1954.

The 75th Anniversary of Operation Husky: the Allied Invasion of Sicily

Robert capa, explore more.

The Second Battle of Fallujah: 15 Years On

Jérôme sessini.

Selfies and Historical Recreation at Korea’s Fake Border

Thomas dworzak.

First Color

Inge morath.

Robert Capa: Israel 1948-1950

The Algerian War

Nicolas tikhomiroff.

The Pacific War: 1942-1945

W. eugene smith.

Questions to My Father

Memory Bank Multiple Perspectives on the Korean War

Read More »

Multiple Perspectives on the Korean War

But as with all historical interpretation, there are other perspectives to consider. The Soviet Union, for its part, denied Truman’s accusation that it was directly responsible. The Soviets believed that the war was “an internal matter that the Koreans would [settle] among themselves.” They argued that North Korea’s leader Kim Il Sung hatched the invasion plan on his own, then pressed the Soviet Union for aid. The Soviet Union reluctantly agreed to help as Stalin became more and more worried about widening American control in Asia. Stalin therefore approved Kim Il Sung’s plan for invasion, but only after being pressured by Chairman Mao Zedong, leader of the new communist People’s Republic of China.

A historian’s job is to account for as many different perspectives as possible. But sometimes language gets in the way. In order to fully understand the Korean War, historians have had to study documents, conversations, speeches and other communications in multiple languages, including Korean, Chinese, English, Japanese and Russian.

In 1995, the famous Chinese historian Shen Zhihua set out to solve a major problem posed by the war. Many people in the west had argued for decades, as Truman did, that North Korea invaded South Korea at the direction of the Soviet Union. Skeptical of that argument, Zhihua spent 1.4 million yuan ($220,000) of his own money to buy declassified documents from Russian historical archives. Then, he had the papers translated into Chinese so he could read them alongside Chinese government documents.

Zhihua found that Stalin had encouraged Mao Zedong to support North Korea’s invasion plan, vaguely promising Soviet air cover to protect North Korean troops. However, Stalin never believed that the United States and the UN would enter the war, and was reluctant to send the Soviet Air Force because he feared direct confrontation with the United States. When the United States landed at Incheon, Mao recognized that the United States and the UN could quickly overrun North Korea. At that point, he decided to support North Korea with or without Soviet aid, as he was determined to stop the Americans. Stalin eventually did send in the Soviet Air Force, but only after pressure from Mao. Zhihua argued that since China decided to take the lead, the Soviet Union played a weaker role in the war than most western historians believed.

The North Koreans had their own view. They argued that the war began not with their invasion of the south, but with earlier border attacks by South Korean leader Syngman Rhee’s forces, ordered by the United States. The DPRK maintains that the American government planned the war in order to shore up the collapsing Rhee government, to help the American economy and to spread its power throughout Asia and around the world.

Journalist Wilfred Burchett reported on those border incidents prior to the North Korean invasion:

“According to my own, still incomplete, investigation, the war started in fact in August-September 1949 and not in June 1950. Repeated attacks were made along key sections of the 38th parallel throughout the summer of 1949, by Rhee’s forces, aiming at securing jump-off positions for a full-scale invasion of the north. What happened later was that the North Korean forces simply decided that things had gone far enough and that the next assault by Rhee’s forces would be repulsed; that- having exhausted all possibilities of peaceful unification, those forces would be chased back and the south liberated.”

In addition to these perspectives, there are others that still need to be fully studied and understood in the west. Certainly the conflict was fueled and abetted by American, Soviet and European and Chinese designs. But, as historian John Merrill argues, Korean perspectives on the conflict need to be better understood. After all, before the war even began, 100,000 Koreans died in political fighting, guerilla warfare and border skirmishes between 1948 and 1950.

Put simply, Koreans across the peninsula had different ideas about what the future of their country would be like once free of foreign occupation. It is up to us to better understand those perspectives. Only then will we have a fuller understanding of the Korean War, its legacy and its influence on the modern world.

American veterans James Argires, Howard Ballard and Glenn Paige provide their own perspectives on the origins of the conflict.

[ Video: James Argires – Perspectives ]

[ Video: Howard Ballard – Perspectives ]

[ Video: Glenn Paige – Perspectives ]

More History

Prewar Context: Western

North Koreans Stream Toward Pusan

Register for a free account to access unlimited free content.

Powered by MOMENTUM MEDIA

- Major Programs

- Special Editions

- Live Streams

- Joint-Capabilities

- Geopolitics and Policy

- land & amphibious /

Photo Essay: The Korean War (1950-1953)

Scroll to read and see more

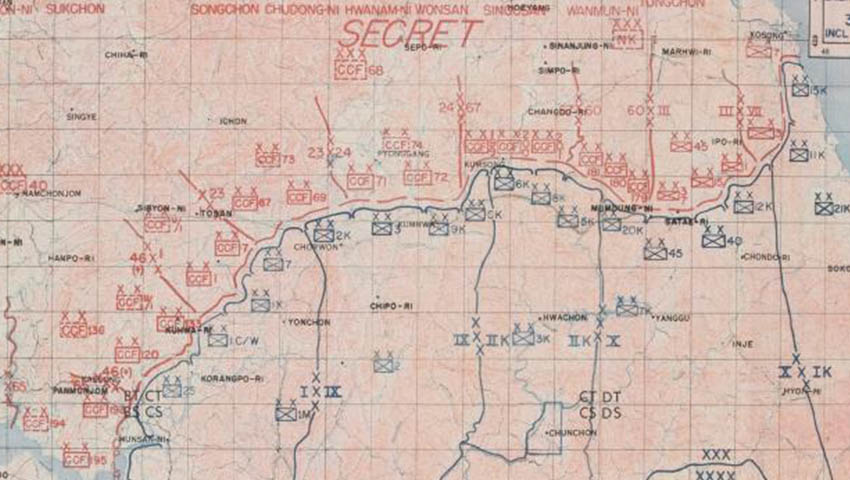

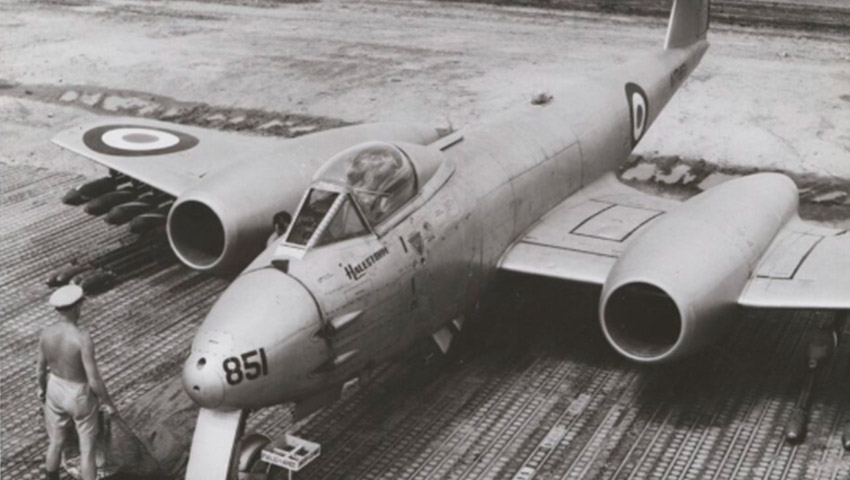

Five short years after the close of WWII, Australia would become embroiled in the US-led invasion of the Korean Peninsula. On 28 June 1950, then-PM Robert Menzies committed the RAN’s Pacific assets to the ‘Forgotten War’; followed soon by No. 77 Squadron (RAAF) and rotating RAR contingents.

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

By becoming a member, I agree to receive information and promotional messages from Defence Connect. I can opt out of these communications at any time. For more information, please visit our Privacy Statement.

Need help signing up? Visit the Help Centre.

After the Chinese-backed North crossed the 38th parallel, the UN Security Council swiftly pushed through UNSC Resolution 82, calling on all members to support the pushback operation as of 25 June 1950. Australia, New Zealand, the US, the UK, and Canada would all join the fight in the days to follow; with the frigate HMAS Shoalhaven stationed in Japan as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (and the destroyer HMAS Bataan on its way to replace the latter), Menzies wasted no time in committing both of these vessels to Korea.

Days later, No. 77 Squadron began sorties over enemy territory, flying American P-51D Mustangs. Less prepared for a surprise outbreak of war, the Australian Army entered the fray on 28 September 1950, landing at Busan (Korea's second city, located at the southern tip of the peninsula). They would assist the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade (and the subsequent 1st Commonwealth Division) through to the signing of the Korean Armistice on 27 July 1953.

This photo essay traces the deployment of Australian forces and assets to Korea, with a particular focus on RAR contingents and the human component.

Korea, 1950

The 38th parallel

The invasion

Hmas shoalhaven.

Sailors of Shoalhaven

No. 77 Squadron

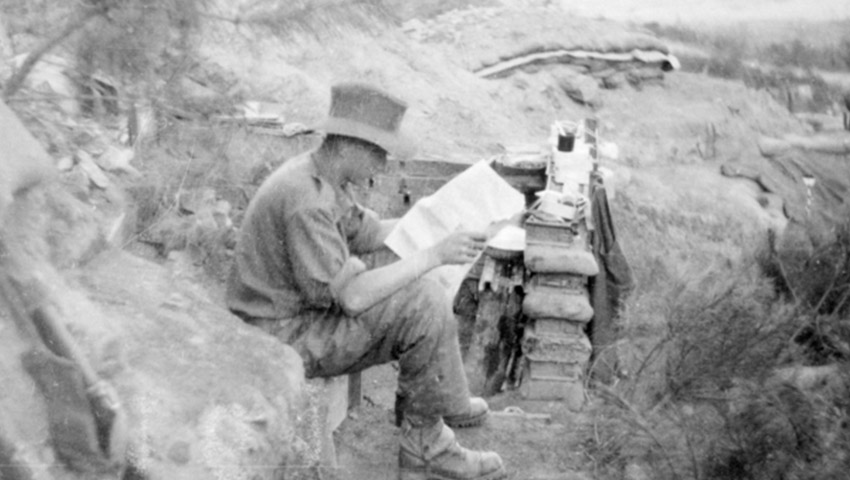

A well-deserved break

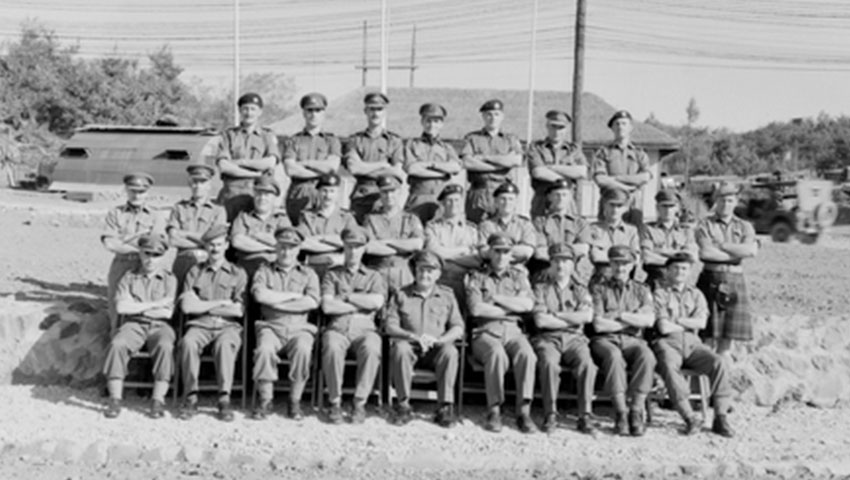

3RAR (Pt. I)

3RAR (Pt. II)

3RAR: a group portrait

Administrative duties

A moment of respite

George Holland

The final parade

1RAR returns

OUR PLATFORMS AND BRANDS

- Accountants Daily

- Accounting Times

- Adviser Innovation

- Australian Aviation

- Cyber Daily

- Defence Connect

- Fintech Business

- Independent Financial Adviser

- Investment Center

- Investor Daily

- Lawyers Weekly

- Money Management

- Mortgage Business

- Property Buzz

- Real Estate Business

- Smart Property Investment

- SMSF Adviser

- Space Connect

- Super Review

- The Adviser

- Wellness Daily

- Which Investment Property

- World of Aviation

EVENTS AND SUMMITS

- Accountants Daily 30 Under 30 Awards

- Adviser Innovation Summit

- Australian Accounting Awards

- Australian Aviation Awards

- Australian Broking Awards

- Australian Defence Industry Awards

- Australian Law Awards

- Australian Space Awards

- Australian Space Summit

- Better Business Summit & Awards

- Corporate Counsel Summit & Awards

- Cyber Security Summit & Awards

- Defence Connect Budget Lunch

- Defence Connect DSR Summit

- Fund Manager of the Year Awards

- ifa Excellence Awards

- ifa Future Forum

- Investor Daily ESG Summit

- Lawyers Weekly 30 Under 30 Awards

- Lawyers Weekly Women in Law Forum

- Mortgage Business Awards

- New Broker Academy

- Partner of the Year Awards

- SME Broker Bootcamp

- SMSF Adviser Technical Day

- Super Fund of the Year Awards

- Women in Finance Awards

- Women in Law Awards

- Accountants Daily Podcast Network

- The Adviser Podcast Network

- Australian Aviation Podcast Network

- Defence Connect Podcast Network

- HR Leader Podcast Network

- The ifa Show

- The Lawyers Weekly Show

- Mortgage Business Podcast Network

- REB Podcast Network

- Relative Return

- The Smart Property Investment Show

- Space Connect Podcast

LEARNING AND EDUCATION

- Momentum Professional

MOMENTUM MARKETS NETWORK

- Momentum Markets

- Momentum Media

- Captivate Events & Communications

- Agile Market Intelligence

STAY CONNECTED

Be the first to hear the latest developments in the defence industry.

- Copyright & Disclaimers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Re-Enacting the Korean War

The battle between the North and South, both real and imagined Photographs by Kim Jae-Hwan / AFP / Getty Images

- South Korea's Case for How the Cheonan Sank

- StumbleUpon

- Del.i.cious

| This web site is dedicated to . This is a photo essay consisting of a series of black and white images taken by my father, Frank S. Farmer and his fellow soldiers, in the last few weeks of, and shortly after, the Korean War, in 1953. Dad was a 26 year-old company commander in the 180th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division, of the Oklahoma National Guard. He was a native Californian, but the enlisted personnel and non-commissioned officers were Oklahomans. My research is not complete as of this writing, but I hope to learn more about his unit and this period of history. There was some fierce fighting, apparently. My Dad was awarded two Bronze Star Medals for bravery in action. He never told me very much about this period. Shortly before Dad's death in 1991, Mr. Jack Harter, his former Executive Officer, sent a tape containing some oral history. Much of this was "insider" material that only the two of them would understand, but clearly this war was a harrowing and moving experience for both. The main objective was to hold a series of hills against Chinese forces, and to survive and go home. There were a number of soldiers on both sides who did not come home. The U. N. force associated with the 180th was a polyglot of U. S., Korean, and Filipino troops. Apparently, there was a great amount of difficulty in coordinating this as a coherent force. If you have any information or comments to share, please contact me. In the mean time, please enjoy the photos. You may view them as a or . Here are more of . Here is more information about the and the , from the . Many Thanks to Those Who Served. Best Regards,

|

|---|

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Cultural Critique

Seen through the Camera Obscura: Life Photographs of the Korean War and Cold War Anxiety of the American Self

- Junghyun Hwang

- University of Minnesota Press

- Number 121, Fall 2023

- pp. 138-161

- 10.1353/cul.2023.a905077

- View Citation

Additional Information

- Buy Article for $19.00 (USD)

The Korean War as seen and shown by Life 's photographic eye constitutes a contested geography in mapping the Cold War and locating America's place in it. Seen through the camera obscura of Life , Korea is conceived as a "terra incognita" of American imagination, and in turn, the magazine as the self-proclaimed national looking glass proves itself to be an interesting peep-box—a kaleidoscope of the American ways of "seeing" the war in Korea, the Cold War, and Americans themselves in the world. Specifically, the article situates Life 's correspondent David Douglas Duncan's photo-essays on the Korean War in the intersections of American and Korean cultural histories, examining them through the lens of Cold War liberalism, which she argues taps deeper into the American frontier myth.

- Buy Digital Article for $19.00 (USD)

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The korean war 101: causes, course, and conclusion of the conflict.

North Korea attacked South Korea on June 25, 1950, igniting the Korean War. Cold War assumptions governed the immediate reaction of US leaders, who instantly concluded that Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin had ordered the invasion as the first step in his plan for world conquest. “Communism,” President Harry S. Truman argued later in his memoirs, “was acting in Korea just as [Adolf] Hitler, [Benito] Mussolini, and the Japanese had acted ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier.” If North Korea’s aggression went “unchallenged, the world was certain to be plunged into another world war.” This 1930s history lesson prevented Truman from recognizing that the origins of this conflict dated to at least the start of World War II, when Korea was a colony of Japan. Liberation in August 1945 led to division and a predictable war because the US and the Soviet Union would not allow the Korean people to decide their own future.

Before 1941, the US had no vital interests in Korea and was largely indifferent to its fate.

Before 1941, the US had no vital interests in Korea and was largely in- different to its fate. But after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his advisors acknowledged at once the importance of this strategic peninsula for peace in Asia, advocating a postwar trusteeship to achieve Korea’s independence. Late in 1943, Roosevelt joined British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kaishek in signing the Cairo Declaration, stating that the Allies “are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent.” At the Yalta Conference in early 1945, Stalin endorsed a four-power trusteeship in Korea. When Harry S. Truman became president after Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, however, Soviet expansion in Eastern Europe had begun to alarm US leaders. An atomic attack on Japan, Truman thought, would preempt Soviet entry into the Pacific War and allow unilateral American occupation of Korea. His gamble failed. On August 8, Stalin declared war on Japan and sent the Red Army into Korea. Only Stalin’s acceptance of Truman’s eleventh-hour proposal to divide the peninsula into So- viet and American zones of military occupation at the thirty-eighth parallel saved Korea from unification under Communist rule.

Deterioration of Soviet-American relations in Europe meant that neither side was willing to acquiesce in any agreement in Korea that might strengthen its adversary.

US military occupation of southern Korea began on September 8, 1945. With very little preparation, Washing- ton redeployed the XXIV Corps under the command of Lieutenant General John R. Hodge from Okinawa to Korea. US occupation officials, ignorant of Korea’s history and culture, quickly had trouble maintaining order because al- most all Koreans wanted immediate in- dependence. It did not help that they followed the Japanese model in establishing an authoritarian US military government. Also, American occupation officials relied on wealthy land- lords and businessmen who could speak English for advice. Many of these citizens were former Japanese collaborators and had little interest in ordinary Koreans’ reform demands. Meanwhile, Soviet military forces in northern Korea, after initial acts of rape, looting, and petty crime, implemented policies to win popular support. Working with local people’s committees and indigenous Communists, Soviet officials enacted sweeping political, social, and economic changes. They also expropriated and punished landlords and collaborators, who fled southward and added to rising distress in the US zone. Simultaneously, the Soviets ignored US requests to coordinate occupation policies and allow free traffic across the parallel.

Deterioration of Soviet-American relations in Europe meant that neither side was willing to acquiesce in any agreement in Korea that might strengthen its adversary. This became clear when the US and the Soviet Union tried to implement a revived trusteeship plan after the Moscow Conference in December 1945. Eighteen months of intermittent bilateral negotiations in Korea failed to reach agreement on a representative group of Koreans to form a provisional government, primarily because Moscow refused to consult with anti-Communist politicians opposed to trustee- ship. Meanwhile, political instability and economic deterioration in southern Korea persisted, causing Hodge to urge withdrawal. Postwar US demobilization that brought steady reductions in defense spending fueled pressure for disengagement. In September 1947, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) added weight to the withdrawal argument when they advised that Korea held no strategic significance. With Communist power growing in China, however, the Truman administration was unwilling to abandon southern Korea precipitously, fearing domestic criticism from Republicans and damage to US credibility abroad.

Seeking an answer to its dilemma, the US referred the Korean dispute to the United Nations, which passed a resolution late in 1947 calling for internationally supervised elections for a government to rule a united Korea. Truman and his advisors knew the Soviets would refuse to cooper- ate. Discarding all hope for early reunification, US policy by then had shifted to creating a separate South Korea, able to defend itself. Bowing to US pressure, the United Nations supervised and certified as valid obviously undemocratic elections in the south alone in May 1948, which resulted in formation of the Republic of Korea (ROK) in August. The Soviet Union responded in kind, sponsoring the creation of the Democratic People’s Re- public of Korea (DPRK) in September. There now were two Koreas, with President Syngman Rhee installing a repressive, dictatorial, and anti-Communist regime in the south, while wartime guerrilla leader Kim Il Sung imposed the totalitarian Stalinist model for political, economic, and social development on the north. A UN resolution then called for Soviet-American withdrawal. In December 1948, the Soviet Union, in response to the DPRK’s request, removed its forces from North Korea.

South Korea’s new government immediately faced violent opposition, climaxing in October 1948 with the Yosu-Sunchon Rebellion. Despite plans to leave the south by the end of 1948, Truman delayed military withdrawal until June 29, 1949. By then, he had approved National Security Council (NSC) Paper 8/2, undertaking a commitment to train, equip, and supply an ROK security force capable of maintaining internal order and deterring a DPRK attack. In spring 1949, US military advisors supervised a dramatic improvement in ROK army fighting abilities. They were so successful that militant South Korean officers began to initiate assaults northward across the thirty-eighth parallel that summer. These attacks ignited major border clashes with North Korean forces. A kind of war was already underway on the peninsula when the conventional phase of Korea’s conflict began on June 25, 1950. Fears that Rhee might initiate an offensive to achieve reunification explain why the Truman administration limited ROK military capabilities, withholding tanks, heavy artillery, and warplanes.

Pursuing qualified containment in Korea, Truman asked Congress for three-year funding of economic aid to the ROK in June 1949. To build sup- port for its approval, on January 12, 1950, Secretary of State Dean G. Ache- son’s speech to the National Press Club depicted an optimistic future for South Korea. Six months later, critics charged that his exclusion of the ROK from the US “defensive perimeter” gave the Communists a “green light” to launch an invasion. However, Soviet documents have established that Acheson’s words had almost no impact on Communist invasion planning. Moreover, by June 1950, the US policy of containment in Korea through economic means appeared to be experiencing marked success. The ROK had acted vigorously to control spiraling inflation, and Rhee’s opponents won legislative control in May elections. As important, the ROK army virtually eliminated guerrilla activities, threatening internal order in South Korea, causing the Truman administration to propose a sizeable military aid increase. Now optimistic about the ROK’s prospects for survival, Washington wanted to deter a conventional attack from the north.

Stalin worried about South Korea’s threat to North Korea’s survival. Throughout 1949, he consistently refused to approve Kim Il Sung’s persistent requests to authorize an attack on the ROK. Communist victory in China in fall 1949 pressured Stalin to show his support for a similar Korean outcome. In January 1950, he and Kim discussed plans for an invasion in Moscow, but the Soviet dictator was not ready to give final consent. How- ever, he did authorize a major expansion of the DPRK’s military capabilities. At an April meeting, Kim Il Sung persuaded Stalin that a military victory would be quick and easy because of southern guerilla support and an anticipated popular uprising against Rhee’s regime. Still fearing US military intervention, Stalin informed Kim that he could invade only if Mao Zedong approved. During May, Kim Il Sung went to Beijing to gain the consent of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Significantly, Mao also voiced concern that the Americans would defend the ROK but gave his reluctant approval as well. Kim Il Sung’s patrons had joined in approving his reckless decision for war.

On the morning of June 25, 1950, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) launched its military offensive to conquer South Korea. Rather than immediately committing ground troops, Truman’s first action was to approve referral of the matter to the UN Security Council because he hoped the ROK military could defend itself with primarily indirect US assistance. The UN Security Council’s first resolution called on North Korea to accept a cease- fire and withdraw, but the KPA continued its advance. On June 27, a second resolution requested that member nations provide support for the ROK’s defense. Two days later, Truman, still optimistic that a total commitment was avoidable, agreed in a press conference with a newsman’s description of the conflict as a “police action.” His actions reflected an existing policy that sought to block Communist expansion in Asia without using US military power, thereby avoiding increases in defense spending. But early on June 30, he reluctantly sent US ground troops to Korea after General Douglas MacArthur, US Occupation commander in Japan, advised that failure to do so meant certain Communist destruction of the ROK.

Kim Il Sung’s patrons [Stalin and Mao] had joined in approving his reckless decision for war.

On July 7, 1950, the UN Security Council created the United Nations Command (UNC) and called on Truman to appoint a UNC commander. The president immediately named MacArthur, who was required to submit periodic reports to the United Nations on war developments. The ad- ministration blocked formation of a UN committee that would have direct access to the UNC commander, instead adopting a procedure whereby MacArthur received instructions from and reported to the JCS. Fifteen members joined the US in defending the ROK, but 90 percent of forces were South Korean and American with the US providing weapons, equipment, and logistical support. Despite these American commitments, UNC forces initially suffered a string of defeats. By July 20, the KPA shattered five US battalions as it advanced one hundred miles south of Seoul, the ROK capital. Soon, UNC forces finally stopped the KPA at the Pusan Perimeter, a rectangular area in the southeast corner of the peninsula.

On September 11, 1950, Truman had approved NSC-81, a plan to cross the thirty-eighth parallel and forcibly reunify Korea

Despite the UNC’s desperate situation during July, MacArthur developed plans for a counteroffensive in coordination with an amphibious landing behind enemy lines allowing him to “compose and unite” Korea. State Department officials began to lobby for forcible reunification once the UNC assumed the offensive, arguing that the US should destroy the KPA and hold free elections for a government to rule a united Korea. The JCS had grave doubts about the wisdom of landing at the port of Inchon, twenty miles west of Seoul, because of narrow access, high tides, and sea- walls, but the September 15 operation was a spectacular success. It allowed the US Eighth Army to break out of the Pusan Perimeter and advance north to unite with the X Corps, liberating Seoul two weeks later and sending the KPA scurrying back into North Korea. A month earlier, the administration had abandoned its initial war aim of merely restoring the status quo. On September 11, 1950, Truman had approved NSC-81, a plan to cross the thirty-eighth parallel and forcibly reunify Korea.

Invading the DPRK was an incredible blunder that transformed a three-month war into one lasting three years. US leaders had realized that extension of hostilities risked Soviet or Chinese entry, and therefore, NSC- 81 included the precaution that only Korean units would move into the most northern provinces. On October 2, PRC Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai warned the Indian ambassador that China would intervene in Korea if US forces crossed the parallel, but US officials thought he was bluffing. The UNC offensive began on October 7, after UN passage of a resolution authorizing MacArthur to “ensure conditions of stability throughout Korea.” At a meeting at Wake Island on October 15, MacArthur assured Truman that China would not enter the war, but Mao already had decided to intervene after concluding that Beijing could not tolerate US challenges to its regional credibility. He also wanted to repay the DPRK for sending thou- sands of soldiers to fight in the Chinese civil war. On August 5, Mao instructed his northeastern military district commander to prepare for operations in Korea in the first ten days of September. China’s dictator then muted those associates opposing intervention.

On October 19, units of the Chinese People’s Volunteers (CPV) under the command of General Peng Dehuai crossed the Yalu River. Five days later, MacArthur ordered an offensive to China’s border with US forces in the vanguard. When the JCS questioned this violation of NSC-81, MacArthur replied that he had discussed this action with Truman on Wake Island. Having been wrong in doubting Inchon, the JCS remained silent this time. Nor did MacArthur’s superiors object when he chose to retain a divided command. Even after the first clash between UNC and CPV troops on October 26, the general remained supremely confident. One week later, the Chinese sharply attacked advancing UNC and ROK forces. In response, MacArthur ordered air strikes on Yalu bridges without seeking Washing- ton’s approval. Upon learning this, the JCS prohibited the assaults, pending Truman’s approval. MacArthur then asked that US pilots receive permission for “hot pursuit” of enemy aircraft fleeing into Manchuria. He was infuriated upon learning that the British were advancing a UN proposal to halt the UNC offensive well short of the Yalu to avert war with China, viewing the measure as appeasement.

On November 24, MacArthur launched his “Home-by-Christmas Offensive.” The next day, the CPV counterattacked en masse, sending UNC forces into a chaotic retreat southward and causing the Truman administration immediately to consider pursuing a Korean cease-fire. In several public pronouncements, MacArthur blamed setbacks not on himself but on unwise command limitations. In response, Truman approved a directive to US officials that State Department approval was required for any comments about the war. Later that month, MacArthur submitted a four- step “Plan for Victory” to defeat the Communists—a naval blockade of China’s coast, authorization to bombard military installations in Manchuria, deployment of Chiang Kai-shek Nationalist forces in Korea, and launching of an attack on mainland China from Taiwan. The JCS, despite later denials, considered implementing these actions before receiving favorable battlefield reports.

Early in 1951, Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway, new commander of the US Eighth Army, halted the Communist southern advance. Soon, UNC counterattacks restored battle lines north of the thirty-eighth parallel. In March, MacArthur, frustrated by Washington’s refusal to escalate the war, issued a demand for immediate surrender to the Communists that sabotaged a planned cease-fire initiative. Truman reprimanded but did not recall the general. On April 5, House Republican Minority Leader Joseph W. Martin Jr. read MacArthur’s letter in Congress, once again criticizing the administration’s efforts to limit the war. Truman later argued that this was the “last straw.” On April 11, with the unanimous support of top advisors, the president fired MacArthur, justifying his action as a defense of the constitutional principle of civilian control over the military, but another consideration may have exerted even greater influence on Truman. The JCS had been monitoring a Communist military buildup in East Asia and thought a trusted UNC commander should have standing authority to retaliate against Soviet or Chinese escalation, including the use of nuclear weapons that they had deployed to forward Pacific bases. Truman and his advisors, as well as US allies, distrusted MacArthur, fearing that he might provoke an incident to widen the war.

MacArthur’s recall ignited a firestorm of public criticism against both Truman and the war. The general returned to tickertape parades and, on April 19, 1951, he delivered a televised address before a joint session of Congress, defending his actions and making this now-famous assertion: “In war there is no substitute for victory.” During Senate joint committee hearings on his firing in May, MacArthur denied that he was guilty of in- subordination. General Omar N. Bradley, the JCS chair, made the administration’s case, arguing that enacting MacArthur’s proposals would lead to “the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy.” Meanwhile, in April, the Communists launched the first of two major offensives in a final effort to force the UNC off the peninsula. When May ended, the CPV and KPA had suffered huge losses, and a UNC counteroffensive then restored the front north of the parallel, persuading Beijing and Pyongyang, as was already the case in Washington, that pursuit of a cease-fire was necessary. The belligerents agreed to open truce negotiations on July 10 at Kaesong, a neutral site that the Communists deceitfully occupied on the eve of the first session.

North Korea and China created an acrimonious atmosphere with at- tempts at the outset to score propaganda points, but the UNC raised the first major roadblock with its proposal for a demilitarized zone extending deep into North Korea. More important, after the talks moved to Panmunjom in October, there was rapid progress in resolving almost all is- sues, including establishment of a demilitarized zone along the battle lines, truce enforcement inspection procedures, and a postwar political conference to discuss withdrawal of foreign troops and reunification. An armistice could have been concluded ten months after talks began had the negotiators not deadlocked over the disposition of prisoners of war (POWs). Rejecting the UNC proposal for non-forcible repatriation, the Communists demanded adherence to the Geneva Convention that required return of all POWs. Beijing and Pyongyang were guilty of hypocrisy regarding this matter because they were subjecting UNC prisoners to unspeakable mistreatment and indoctrination.

On April 11, with the unanimous support of top advisors, the presi- dent fired MacArthur.

Truman ordered that the UNC delegation assume an inflexible stand against returning Communist prisoners to China and North Korea against their will. “We will not buy an armistice,” he insisted, “by turning over human beings for slaughter or slavery.” Although Truman unquestionably believed in the moral rightness of his position, he was not unaware of the propaganda value derived from Communist prisoners defecting to the “free world.” His advisors, however, withheld evidence from him that contradicted this assessment. A vast majority of North Korean POWs were actually South Koreans who either joined voluntarily or were impressed into the KPA. Thousands of Chinese POWs were Nationalist soldiers trapped in China at the end of the civil war, who now had the chance to escape to Taiwan. Chinese Nationalist guards at UNC POW camps used terrorist “re-education” tactics to compel prisoners to refuse repatriation; resisters risked beatings or death, and repatriates were even tattooed with anti- Communist slogans.

In November 1952, angry Americans elected Dwight D. Eisenhower president, in large part because they expected him to end what had be- come the very unpopular “Mr. Truman’s War.” Fulfilling a campaign pledge, the former general visited Korea early in December, concluding that further ground attacks would be futile. Simultaneously, the UN General Assembly called for a neutral commission to resolve the dispute over POW repatriation. Instead of embracing the plan, Eisenhower, after taking office in January 1953, seriously considered threatening a nuclear attack on China to force a settlement. Signaling his new resolve, Eisenhower announced on February 2 that he was ordering removal of the US Seventh Fleet from the Taiwan Strait, implying endorsement for a Nationalist assault on the mainland. What influenced China more was the devastating impact of the war. By summer 1952, the PRC faced huge domestic economic problems and likely decided to make peace once Truman left office. Major food shortages and physical devastation persuaded Pyongyang to favor an armistice even earlier.

An armistice ended fighting in Korea on July 27, 1953.

Early in 1953, China and North Korea were prepared to resume the truce negotiations, but the Communists preferred that the Americans make the first move. That came on February 22 when the UNC, repeating a Red Cross proposal, suggested exchanging sick and wounded prisoners. At this key moment, Stalin died on March 5. Rather than dissuading the PRC and the DPRK as Stalin had done, his successors encouraged them to act on their desire for peace. On March 28, the Communist side accepted the UNC proposal. Two days later, Zhou Enlai publicly proposed transfer of prisoners rejecting repatriation to a neutral state. On April 20, Operation Little Switch, the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners, began, and six days later, negotiations resumed at Panmunjom. Sharp disagreement followed over the final details of the truce agreement. Eisenhower insisted later that the PRC accepted US terms after Secretary of State John Foster Dulles informed India’s prime minister in May that without progress toward a truce, the US would terminate the existing limitations on its conduct of the war. No documentary evidence has of yet surfaced to support his assertion.

Also, by early 1953, both Washington and Beijing clearly wanted an armistice, having tired of the economic burdens, military losses, political and military constraints, worries about an expanded war, and pressure from allies and the world community to end the stalemated conflict. A steady stream of wartime issues threatened to inflict irrevocable damage on US relations with its allies in Western Europe and nonaligned members of the United Nations. Indeed, in May 1953, US bombing of North Korea’s dams and irrigation system ignited an outburst of world criticism. Later that month and early in June, the CPV staged powerful attacks against ROK defensive positions. Far from being intimidated, Beijing thus displayed its continuing resolve, using military means to persuade its adversary to make concessions on the final terms. Before the belligerents could sign the agreement, Rhee tried to torpedo the impending truce when he released 27,000 North Korean POWs. Eisenhower bought Rhee’s acceptance of a cease-fire with pledges of financial aid and a mutual security pact.

An armistice ended fighting in Korea on July 27, 1953. Since then, Koreans have seen the war as the second-greatest tragedy in their recent history after Japanese colonial rule. Not only did it cause devastation and three million deaths, it also confirmed the division of a homogeneous society after thirteen centuries of unity, while permanently separating millions of families. Meanwhile, US wartime spending jump-started Japan’s economy, which led to its emergence as a global power. Koreans instead had to endure the living tragedy of yearning for reunification, as diplomatic tension and military clashes along the demilitarized zone continued into the twenty-first century.

Korea’s war also dramatically reshaped world affairs. In response, US leaders vastly increased defense spending, strengthened the North Atlantic Treaty Organization militarily, and pressed for rearming West Germany. In Asia, the conflict saved Chiang’s regime on Taiwan, while making South Korea a long-term client of the US. US relations with China were poisoned for twenty years, especially after Washington persuaded the United Nations to condemn the PRC for aggression in Korea. Ironically, the war helped Mao’s regime consolidate its control in China, while elevating its regional prestige. In response, US leaders, acting on what they saw as Korea’s primary lesson, relied on military means to meet the challenge, with disastrous results in Việt Nam.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

SUGGESTED RESOURCES

Kaufman, Burton I. The Korean Conflict . Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1999.

“Korea: Lessons of the Forgotten War.” YouTube video, 2:20, posted by KRT Productions Inc., 2000. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fi31OoQfD7U.

Lee, Steven Hugh. The Korean War. New York: Longman, 2001.

Matray, James I. “Korea’s War at Sixty: A Survey of the Literature.” Cold War History 11, no. 1 (February 2011): 99–129.

US Department of Defense. Korea 1950–1953, accessed July 9, 2012, http://koreanwar.defense.gov/index.html.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Read The Diplomat , Know The Asia-Pacific

- Central Asia

- Southeast Asia

- Environment

- Asia Defense

- China Power

- Crossroads Asia

- Flashpoints

- Pacific Money

- Tokyo Report

- Trans-Pacific View

Photo Essays

- Write for Us

- Subscriptions

The Great Korean Garbage War

Recent features.

Bangladeshi University Students Protest Quota System Reforms

What’s in Hong Kong’s Proposed Critical Infrastructure Bill?

Why the Panchen Lama Matters

The Problem With POGOs

Why the Himalayan Region Is Integral to a Rules-Based Order in the Indo-Pacific

Engagement With China Has Had a Multifaceted Impact on Latin American Democracy

Bloggers in the Crosshairs: The Complex Reality of Media Freedom in Uzbekistan

SCO Expansion: A Double-Edged Sword

Shattering Silence: Pakistan’s Journey Against Gender-Based Violence

Japan’s Enhanced Security Engagement With the Pacific Islands

Migrant Workers Pay Sky-high Fees to Expand Taiwan’s Biggest Airport

Indian Foreign Policy Under Narendra Modi: A Decade of Transformation

North Korea responds to a long-standing South Korean provocation.

North Korea has been flying substantial numbers of “trash balloons” over to South Korea. Cell phones sound alerts in the middle of the night whenever these balloons cross over into South Korea. The balloons, which often contain animal waste, have caused quite extensive damage, such as breaking vinyl greenhouses and hitting private cars.

Although confrontations between North and South Korea are usually triggered by North Korea, on this occasion the issue began with the South Koreans.

For many years, South Korean civil groups have been tying USBs containing leaflets criticizing the Kim Jong Un administration, along with South Korean movies, TV series, and K-pop to balloons that are then dispatched northward. The practice has been an irritation for Pyongyang. Leaflets denigrating the Supreme Leader are not only considered outrageous in North Korea, but the North Koreans are also nervous about the influx of South Korean culture, as evidenced in the enactment of the “Law on Rejecting Reactionary Ideology and Culture” in December 2020 and the “Pyongyang Cultural Language Protection Act” in January 2023.

Their patience having run thin, the North Koreans issued a statement in the name of the vice defense minister on May 25, threatening to fly balloons to South Korea. The statement expressed strong concern about “how much effort is required to remove them,” meaning the flying objects from the south, and said that the flying balloons were “a dangerous provocation that can be utilized for a specific military purpose.” With this, Pyongyang is suggesting that balloons can be used as biochemical weapons; as such, its anger is understandable.

Nonetheless, South Korea did not end the practice, and three days later, North Korea began sending balloons toward South Korea, carrying cigarette butts, old batteries, and even excrement. Obviously, Pyongyang concluded that flying leaflets praising Kim Jong Un would have little effect on the South Korean people.

On May 29, Kim Yo Jong, vice department director of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK), jokingly referred to the “trash balloons” as “sincere presents” and criticized South Korea for holding that the leaflet distribution falls under “freedom of expression.” On June 2, the vice defense minister issued another statement unilaterally declaring that this action would be “temporarily halted,” but warned that if the South Korean side resumed distributing leaflets, they would “again dump 100 times more trash.”

The Yoon Suk-yeol administration did not urge South Koreans to exercise restraint, and after a group of North Korean defectors dispatched leaflets toward North Korea on the 6th, the North Koreans began to fly “trash balloons” again on the 8th, although the volume was some way short of “100 times more.” Clearly, it takes some time to prepare such a large number of big balloons.

On the 9th, Kim Yo Jong released another statement, the last sentence revealing her true sentiment. Rather than threatening specific acts of retaliation, it concluded by saying, “I sternly warn Seoul to stop at once this dangerous act that may create a new environment of crisis.” It is quite clear that North Korea only wants to stop the balloons from South Korea, hoping to avoid escalating the issue more than necessary. As further evidence of this, the Rodong Sinmun has not reported on this move to the domestic readership.

North Korea also condemned the balloons from South Korea in June 2020. Back then, it used the practice as an excuse to blow up the Inter-Korean Liaison Office, a symbol of inter-Korean cooperation, and informed the North Korean people in detail about the deterioration of relations with South Korea.

In December 2020, South Korea – then under the Moon Jae-in administration, whose goal was peaceful coexistence with North Korea – enacted the “Law Prohibiting the Sending of Leaflets to North Korea,” which imposed a penalty of up to three years in prison for distributing leaflets. However, in May 2022, to the hardline conservative Yoon Suk-yeol administration took over, and in September 2023, the Constitutional Court ruled the law unconstitutional as it “excessively restricts freedom of expression.”

Retaliating against the “trash balloons,” the South Korean government decided to suspend the Comprehensive Military Agreement (CMA), which had been signed in September 2018, on June 4. Likely the intention was to send a strong message to North Korea, but in reality, this was a significant loss for South Korea as well. Under the agreement, North Korea had made concessions to South Korea, such as acknowledging the existence of the Northern Limit Line (NLL) for the first time. It is not a good idea for South Korea to let go of this framework in an attempt to regulate North Korea’s actions. President Yoon Suk-yeol voluntarily gave up this card just so that he could reject his predecessor’s policy toward North Korea.

Under the assumption that the balloons carry not leaflets or excrement but biochemical weapons, both South and North Korea are on high alert. Unlike ballistic missiles, balloons can be flown at low altitudes in large numbers simultaneously, so there are natural limits to the available countermeasures. With this issue unlikely to end any time soon, it will surely not be long before “trash balloons” that fall into the sea wash up on the coasts of Korean neighbors such as Japan.

ISOZAKI Atsuhito is a professor at Keio University.

The Russia-North Korea Military Alliance: Reducing Its Negative Fallout

By jongsoo lee.

Reading Moon Jae-in’s Memoirs

By isozaki atsuhito.

North Koreans Are Seen Wearing Kim Jong Un Pins for the First Time

By hyung-jin kim.

Tragic Factory Fire Spotlights South Korea’s Unsustainable Immigration Policy

By james constant.

Why is India’s Hindu Right Pro-Israel?

By akhilesh pillalamarri.

Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh Pressured to Join Myanmar’s Civil War

By dayna santana pérez.

Philippines Has ‘Secretly Reinforced’ South China Sea Outpost, Report Claims

By sebastian strangio.

China and the Philippines Inch Closer to Conflict in the South China Sea

By Charles Mok

By Antonio Terrone

By Felix Iglesias

By Jagannath Panda, Ryohei Kasai, and Eerishika Pankaj

The Korean War: Barbarism Unleashed

Contents

“Massacre in Korea” by Pablo Picasso, 1951

I. Introduction: Contrasting views

Remembering the korean war, was the korean war necessary and just, could the war have been avoided, ii. origins and causes of the korean war, backdrop of japanese colonialism, american imperial ambitions, social revolution and repression in north korea.

- Brutal anticommunist pacification in South Korea

- Southern provocations and the origins of the war

Domestic politics and bipartisan support for the war

Iii. military history of the war, north korean blitzkrieg and occupation of seoul.

- “So terrible a liberation:” Pusan, Seoul, Inchon, and Operation Rat Killer

Chinese counterattack and American retreat

High noon: the truman-macarthur stand-off.

- Bombing ‘em back to the Stone Age: Aerial techno-war over North Korea

IV. Public opinion and antiwar dissent in the United States

- Manufacturing consent: Media coverage of the war

The responsibility of intellectuals: “Crackpot Realists” and the New Mandarins

Grassroots antiwar activism and dissent, american soldiers’ experience and disillusionment.

- Letter exchange between a questioning Marine, his father, and Dean Acheson

V. The war’s costs, dirty secrets, and legacies

South korea’s truth and reconciliation commission and atrocities in the war.

- Dirty little secrets: Maltreatment of prisoners of war

Allegations of biological warfare

- “The Horror, The Horror”: Korea’s Lieutenant Kurtz

Racism and class stratification in the U.S. Army

- Canada and Great Britain’s Korean War

Legacies of the war

Recommended resources, about the author, did you know.

- Japan imposed colonial rule over Korea from 1910 to 1945.

- With Japan on the verge of defeat in World War II, two young American army officers drew an arbitrary line across Korea at the 38th parallel, creating an American zone in the south and a Soviet zone in the north. Both South and North Korea became repressive regimes.

- In South Korea, the United States built up a police force and constabulary and backed the authoritarian leader Syngman Rhee, who created a police state. By 1948 partisan warfare had enveloped the whole of South Korea, which in turn became enmeshed in civil war between South and North Korea.

- In North Korea, the government of Kim II-Sung arrested and imprisoned student and church leaders, and gunned down protesters on November 23, 1945. Christians as well as business and land owners faced with the confiscation of their property began fleeing to the South.

- The U.S. Army counter-intelligence corps organized paramilitary commandos to carry out sabotage missions in the North, a factor accounting for the origins of the war. The Korean War officially began on June 25, 1950, when North Korea conducted a massive invasion of the South.

- The U.S. obtained the approval of the United Nations for the defense of South Korea (the Soviet Union had boycotted the UN over the issue of seating China). Sixteen nations supplied troops although the vast majority came from the United States and South Korea. U.S. General Douglas MacArthur headed the United Nations Command.

- The three-year Korean War resulted in the deaths of three to four million Koreans, produced 6-7 million refugees, and destroyed over 8,500 factories, 5,000 schools, 1,000 hospitals and 600,000 homes. Over 36,000 American soldiers died in the war.

- From air bases in Okinawa and naval aircraft carriers, the U.S. Air Force launched over 698,000 tons of bombs (compared to 500,000 tons in the entire Pacific theater in World War II), obliterating 18 of 22 major cities and destroying much of the infrastructure in North Korea.

- The US bombed irrigation dams, destroying 75 percent of the North’s rice supply, violating civilian protections set forth in the Geneva Conventions of 1949.

- The Korean War has been called a “limited war” because the U.S. refrained from using nuclear weapons (although this was considered). Yet the massive destruction of North Korea and the enormous death toll in both North and South mark it as one of the most barbarous wars in modern history.

- Reports of North Korean atrocities and war crimes were well publicized in the United States at the time. The 2005 South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission, however, judged that most of the mass killings of civilians were conducted by South Korean military and police forces, with the United States adding more from the air.

- For all the human suffering caused by the Korean War, very little was solved. The war ended in stalemate with the division of the country at the 38th parallel.

Korean War Memorial in Washington

The Washington war memorial stands in sharp contrast to one of the finest pieces of art to emerge from the war, Pablo Picasso’s painting “Massacre in Korea” (1951). Picasso captured much about the horrors of American style techno-war in depicting a group of robot-like soldiers descending on a village – thought to be Sinchon in South Hwangae Province, North Korea. The soldiers are preparing to execute women and children suspected of sheltering guerrilla combatants. The miracle of the painting is that the faces of the women about to be shot are transformed into masks of art, an expression of life amidst the horror and death that is war.

Korean War Monument in Seoul

The ceremony epitomizes Korea’s status as a “forgotten war” in American memory, one which came between the glorious victory in World War II and inglorious defeat in Vietnam. Writing in the Washington Post , Richard L. Halferty, head of the Texas Korean War Veterans Committee compared the Memorial Day slight with the heroic reception he claimed to have received on a visit to Seoul and Chipyong-ni in 2010, where he was allegedly hugged and thanked by women and men who spotted his Korean War veterans hat. In considering the question, was the war worth it, Halferty urged readers to look at the results. “When the U.S. entered the war to protect the freedom of South Korea, the nation was at the bottom of the world. The Korean people took the freedom we helped buy with our blood and rose to become one of the top economies in the world.” [3]

Korean War Memorial in Pyongyang

Wolfowitz’ analysis is undercut by George Katsiaficas’ history, Asia’s Unknown Uprisings: South Korean Social Movements in the 20 th Century (2012), which shows that democracy emerged in 1987 not because it was promoted by the U.S. but because of the efforts of committed social activists, many of whom endured torture, beatings, and massacres fighting against the American-imposed military dictatorship. For years, the U.S. had built up South Korea’s military and police forces, honoring the generals who committed myriad atrocities, including the 1980 Kwangju massacre, South Korea’s equivalent to the Tiananmen Square massacre in China in 1989. [6]

On June 27, 1950, President Truman sent U.S. forces to Korea under United Nations authority, without a declaration of war from Congress

President Harry S. Truman claimed the U.S. goal in Korea was to prevent the “rule of force in international affairs” and to “uphold the rule of law,” but this was utterly contradicted by American support for right-wing counter-insurgent forces in Greece, which committed large-scale atrocities in suppressing an indigenous left-wing rebellion led by anti-fascist elements, and in subsequent years, by Washington’s overthrow by force of the legally elected governments of Iran and Guatemala in 1953 and 1954, respectively. As Howard Zinn pointed out in Postwar America, 1945-1971 (1973), other cases of aggression or alleged aggression in the world, such as the Arab states invasion of Israel in 1948, did not prompt the U.S. to mobilize the UN or its own armed forces for intervention. Zinn concluded that the decision to intervene in Korea was, at its core, political, designed to uphold the dictatorial U.S. client regime of Syngman Ree and acquire U.S. military bases in South Korea, which the U.S. did as a result of the war. [10]

Survivors wander among the debris in the aftermath of an air raid by U.S. planes over Pyongyang, circa 1950 (photo: Keystone/Getty Images)

Donald Kingsley, head of the UN Korean Relief and Reconstruction Agency, called Korea “the most devastated land and its people the most destitute in the history of modern warfare.” [12] This devastation was inflicted primarily by the United States and its proxies with backing from the United Nations. Taking this into account, the Korean War can be considered to have been a gross injustice and crime for which the U.S. bears important responsibility. To add insult to injury, the war did not resolve the conflict between North and South, which lingers on today, over 60 years later.

Yo Unhyong, South Korean leader who sought peaceful unification

Among Rhee’s victims were moderate nationalist politicians such as Kim Ku, who warned that Koreans should not fight each other, and Yo Un-Hyong, who had wanted the peaceful unification of North and South. Yo had headed a provisional government preceding the U.S. military occupation and advocated a mix of liberal-nationalist and social democratic ideals which were anathema to the Rhee government. Revered in both North and South Korea today, Yo had been a newspaper editor who opposed Japanese colonialism, and though not a communist himself, had always been willing to work with communists. Had the U.S. supported Yo and his efforts to create a unity government with the North, the war and its attendant misery could likely have been avoided and Korea’s history would be much different. Instead, Congress passed the Far Eastern Economic Assistance Act in February 1950, which required immediate termination of U.S. aid to South Korea should a single member of communist-linked parties in the South join the coalition government, or if any member of the North Korean government participated in the South Korean government, which could presage an end to the artificial division of the 2,000-year-old Korean culture. [13]

Japan and the U.S. both entered the imperial competition in Asia at the turn of the 20th century, Japan in Korea and the U.S. in the Philippines. Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Russia had already established control over large areas of Asia.

Beyond occupying South Korea at the end of World War II, U.S. involvement in Korea was a consequence of the long American drive for power in the Asia-Pacific region dating to the seizure of Hawaii and conquest of the Philippines at the turn of the 20 th century. This mission was motivated by a trinity of military, missionary, and business interests. After the defeat of Japan in World War II, the prospect opened up that the region could come under U.S. influence, its rich resources tapped for the benefit of American industry. In a March 1955 Foreign Affairs article, William Henderson of the Council on American Foreign Relations (which Laurence Shoup and William Minter aptly termed the “imperial brain trust”) wrote: “As one of the earth’s great storehouses of natural resources, Southeast Asia is a prize worth fighting for. Five sixths of the world’s rubber, and one half of its tin are produced here. It accounts for two thirds of the world output in coconut, one third of the palm oil, and significant proportions of tungsten and chromium. No less important than the natural wealth was Southeast Asia’s key strategic position astride the main lines of communication between Europe and the Far East.” [20] To secure access to these resources, the U.S. established a chain of military bases from the Philippines through the Ryukyu Archipelago in southern Japan.