- Presidential Message

- Nominations/Elections

- Past Presidents

- Member Spotlight

- Fellow List

- Fellowship Nominations

- Current Awardees

- Award Nominations

- SCP Mentoring Program

- SCP Book Club

- Pub Fee & Certificate Purchases

- LEAD Program

- Introduction

- Find a Treatment

- Submit Proposal

- Dissemination and Implementation

- Diversity Resources

- Graduate School Applicants

- Student Resources

- Early Career Resources

- Principles for Training in Evidence-Based Psychology

- Advances in Psychotherapy

- Announcements

- Submit Blog

- Student Blog

- The Clinical Psychologist

- CP:SP Journal

- APA Convention

- SCP Conference

CASE STUDY Victor (post-traumatic stress disorder)

Case study details.

Victor is a 27-year-old man who comes to you for help at the urging of his fiancée. He was an infantryman with a local Marine Reserve unit who was honorably discharged in 2014 after serving two tours of duty in Iraq. His fiancé has told him he has “not been the same” since his second tour of duty and it is impacting their relationship. Although he offers few details, upon questioning he reports that he has significant difficulty sleeping, that he “sleeps with one eye open” and, on the occasions when he falls into a deeper sleep, he has nightmares. He endorses experiencing several traumatic events during his second tour, but is unwilling to provide specific details – he tells you he has never spoken with anyone about them and he is not sure he ever will. He spends much of his time alone because he feels irritable and doesn’t want to snap at people. He reports to you that he finds it difficult to perform his duties as a security guard because it is boring and gives him too much time to think. At the same time, he is easily startled by noise and motion and spends excessive time searching for threats that are never confirmed both when on duty and at home. He describes having intrusive memories about his traumatic experiences on a daily basis but he declines to share any details. He also avoids seeing friends from his Reserve unit because seeing them reminds him of experiences that he does not want to remember.

- Hypervigilance

- Intrusive Thoughts

- Irritability

- Loss of Interest

- Sleep Difficulties

Diagnoses and Related Treatments

1. posttraumatic stress disorder.

Thank you for supporting the Society of Clinical Psychology. To enhance our membership benefits, we are requesting that members fill out their profile in full. This will help the Division to gather appropriate data to provide you with the best benefits. You will be able to access all other areas of the website, once your profile is submitted. Thank you and please feel free to email the Central Office at [email protected] if you have any questions

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 25 November 2008

A case of PTSD presenting with psychotic symptomatology: a case report

- Georgios D Floros 1 ,

- Ioanna Charatsidou 1 &

- Grigorios Lavrentiadis 1

Cases Journal volume 1 , Article number: 352 ( 2008 ) Cite this article

30k Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

A male patient aged 43 presented with psychotic symptomatology after a traumatic event involving accidental mutilation of the fingers. Initial presentation was uncommon although the patient responded well to pharmacotherapy. The theoretical framework, management plan and details of the treatment are presented.

Recent studies have shown that psychotic symptoms can be a hallmark of post-traumatic stress disorder [ 1 , 2 ]. The vast majority of the cases reported concerned war veterans although there were sporadic incidents involving non-combat related trauma (somatic or psychic). There is a biological theoretical framework for the disease [ 3 ] as well as several psychological theories attempting to explain cognitive aspects [ 4 ].

Case presentation

A male patient, aged 43, presented for treatment with complaints tracing back a year ago to a traumatic work-related event involving mutilation of the distal phalanges of his right-hand fingers. Main complaints included mixed hallucinations, irritability, inability to perform everyday tasks and depressive mood. No psychic symptomatology was evident before the event to him or his social milieu.

Mental state examination

The patient was a well-groomed male of short stature, sturdy build and average weight. He was restless but not agitated, with a guarded attitude towards the interviewer. His speech pattern was slow and sparse, his voice low. He described his current mood as 'anxious' without being able to provide with a reason. Patient appeared dysphoric and with blunted affect. He was able to maintain a linear train of thought with no apparent disorganization or irrational connections when expressing himself. Thought content centred on his amputated fingers with a semi-compulsive tendency to gaze to his (gloved) hand. The patient was typically lost in ruminations about his accident with a focus on the precise moment which he experienced as intrusive and affectively charged in a negative and painful way. He could remember wishing for his fingers to re-attach to his hand almost as the accident took place. A trigger in his intrusive thoughts was the painful sensation of neuropathic pain from his half-mutilated fingers, an artefact of surgery.

He denied and thoughts of harming himself and demonstrated no signs of aggression towards others. Hallucinations had a predominantly depressive and ego-dystonic character. He denied any perceptual disturbances at the time of the examination. Their appearance was typically during nighttime especially in the twilight. Initially they were visual only, involving shapes and rocks tumbling down towards the patient, gradually becoming more complex and laden with significance. A mixed visual and tactile hallucination of burning rain came afterwards while in the time of examination a tall stranger clad in black and raiding a tall steed would threaten and ridicule the patient. He scored 21 on a MMSE with trouble in the attention, calculation and recall categories. The patient appeared reliable and candid to the extent of his self-disclosure, gradually opening up to the interviewer but displayed a marked difficulty on describing his emotions and memories of the accident, apparently independent of his conscious will. His judgement was adequate and he had some limited Insight into his difficulties, hesitantly attributing them to his accident.

He was married and a father of three (two boys and a girl aged 7–12) He had no prior medical history for mental or somatic problems and received no medication. He admitted to occasional alcohol consumption although his relatives confirmed that he did not present addiction symptoms. He had some trouble making ends meet for the past five years. Due to rampant unemployment in his hometown, he was periodically employed in various jobs, mostly in the construction sector. One of his children has a congenital deformity, underwent several surgical procedures with mixed results and, before the time of the patient's accident, it was likely that more surgery would be forthcoming. The patient's father was a proud man who worked hard but reportedly was victimized by his brothers, they reaping the benefits of his work in the fields by manipulating his own father. He suffered a nervous breakdown attributed to his low economic status after a failed economic endeavour ending in him being robbed of the profits, seven years before the accident. There was no other relevant family history.

Before the accident the patient was a lively man, heavily involved as a participant and organizer in important local social events from a young age. He was respected by his fellow villagers and felt his involvement as a unique source of pride in an otherwise average existence. Prior to his accident, the patient was repeatedly promised a permanent job as a labourer and fate would have it that his appointment was supposedly approved immediately after the accident only to be subsequently revoked. He viewed himself as an exploited man in his previous jobs, much the same way his father was, while he harboured an extreme bitterness over the unavailability of support for his long-standing problems. His financial status was poor, being in sick-leave from his previous job for the last four months following the accident and hoping to receive some compensation. Although his injuries were considered insufficient for disability pension he could not work to his full capacity since the hand affected was his primary one and he was a manual labourer.

Given that the patient clearly suffered a high level of distress as a result of his hallucinatory experiences he was voluntary admitted to the 2nd Psychiatric Department of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki for further assessment, observation and treatment. A routine blood workup was ordered with no abnormalities. A Rorschach Inkblot Test was administered in order to gain some insight into patient's dynamics, interpersonal relations and underlying personality characteristics while ruling out any malingering or factitious components in the presentation as suggested in Wilson and Keane [ 5 ]. Results pointed to inadequate reality testing with slight disturbances in perception and a difficulty in separating reality from fantasy, leading to mistaken impressions and a tendency to act without forethought in the face of stress. Uncertainty in particular was unbearable and adjustment to a novel environment hard. Cognitive functions (concentration, attention, information processing, executive functions) were impaired possibly due to cognitive inability or neurological disease. Emotion was controlled with a tendency for impulsive behaviour; however there was difficulty in processing and expressing emotions in an adaptive manner. There were distinct patterns of aggression and anger towards others but expressing those patterns was avoided, switching to passivity and denial rather than succumbing to destructive urges or mature competitiveness. Self-esteem was low with feelings of inferiority and inefficiency.

A neurological examination revealed a left VI cranial nerve paresis, reportedly congenital, resulting in diplopia while gazing to the extreme left, which did not significantly affect the patient. The patient had a chronic complaint of occasional vertigo, to which he partly attributed his accident, although the symptoms were not of a persisting nature.

Initial diagnosis at this stage was 'Psychotic disorder NOS' and pharmacological treatment was initiated. An MRI scan of the brain with gadolinium contrast was ordered to rule out any focal neurological lesions. It was performed fifteen days later and revealed no abnormalities.

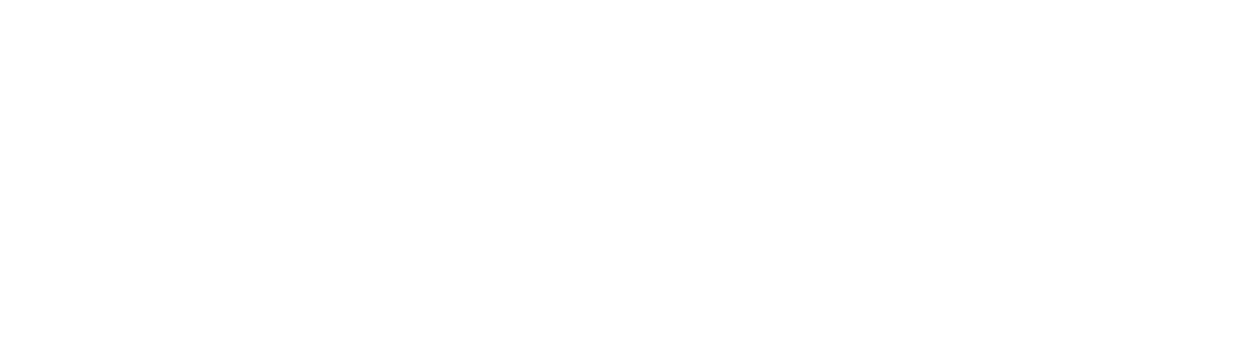

Patient was placed on ziprasidone 40 mg bid and lorazepam 1 mg bid. He reported an immediate improvement but when the attending physician enquired as to the nature of the improvement the patient replied that in his hallucinations he told the tall raider that he now had a tall doctor who would help him and the raider promptly left (sic). Apparently, the random assignment of a strikingly tall physician had an unexpected positive effect. Ziprasidone gradually increased to 80 mg bid within three days with no notable effect to the perceptual disturbances but with the development of akathisia for which biperiden was added, 1 mg tid. Duloxetine was added, 60 mg once-daily, in a hope that it could have a positive effect to his mood but also to this neuropathic pain which was frequent and demoralising. The patient had a tough time accommodating to the hospital milieu, although the grounds were extended and there was plenty of opportunity for walks and other activities. He preferred to stay in bed sometimes in obvious agony and with marked insomnia. He presented a strong fear for the welfare of his children, which he could not reason for. Due to the apparent inability of ziprasidone to make a dent in the psychotic symptomatology, medication was switched to amisulpride 400 mg bid and the patient was given a leave for the weekend to visit his home. On his return an improvement in his symptoms was reported by him and close relatives, although he still had excessive anxiety in the hospital setting. It was decided that his leave was to be extended and the patient would return for evaluation every third day. After three appointments he had a marked improvement, denied any psychotic symptoms while his sleep pattern improved. A good working relationship was established with his physician and the patient was with a schedule of follow-up appointments initially every fifteen days and following two months, every thirty days. His exit diagnosis was "Psychotic disorder Not Otherwise Specified – PTSD". He remained asymptomatic for five months and started making in-roads in a cognitively-oriented psychotherapeutic approach but unfortunately further trouble befell him, his wife losing a baby and his claim to an injury compensation rejected. He experienced a mood loss and duloxetine was increased to 120 mg per day to some positive effect. His status remains tenuous but he retains a strong will to make his appointments and work with his physician. A case conceptualization following a cognitive framework [ 6 ] is presented in Figure 1 .

Case formulation – (Persistent PTSD, adapted from Ehlers and Clark [ 6 ] ) . Case formulation following the persistent PTSD model of Ehlers and Clark [ 6 ]. It is suggested that the patient is processing the traumatic information in a way which a sense of immediate threat is perpetuated through negative appraisals of trauma or its consequences and through the nature of the traumatic experience itself. Peri-traumatic influences that operate at encoding, affect the nature of the trauma memory. The memory of the event is poorly elaborated, not given a complete context in time and place, and inadequately integrated into the general database of autobiographical knowledge. Triggers and ruminations serve to re-enact the traumatic information while symptoms and maladaptive coping strategies form a vicious circle. Memories are encoded in the SAM rather than the VAM system, thus preventing cognitive re-appraisal and eventual overcoming of traumatic experience [ 4 ].

The value of a specialized formulation is made clear in complex cases as this one. There is a relationship between the pre-existing cognitive schemas of the individual, thought patterns emerging after the traumatic event and biological triggers. This relationship, best described as a maladaptive cognitive processing style, culminates into feelings of shame, guilt and worthlessness which are unrelated to similar feelings, which emerge during trauma recollection, but nonetheless acts in a positive feedback loop to enhance symptom severity and keep the subject in a constant state of psychotic turmoil. Its central role is addressed in our case formulation under the heading "ruminations" which best describes its ongoing and unrelenting character. The "what if" character of those ruminations may serve as an escape through fantasy from an unbearably stressful cognition. Past experience is relived as current threat and the maladaptive coping strategies serve as negative re-enforcers, perpetuating the emotional suffering.

The psychosocial element in this case report, the patient's involvement with a highly symbolic activity, demonstrates the importance of individualising the case formulation. Apparently the patient had a chronic difficulty in expressing his emotions and integrating into his social surroundings, a difficulty counter-balanced somewhat with his involvement in the local social events which gave him not only a creative way out from any emotional impasse but also status and recognition. His perceived inability to continue with his symbolic activities was not only an indicator of the severity of his troubles but also a stressor in its own right.

Complex cases of PTSD presenting with hallucinatory experiences can be effectively treated with pharmacotherapy and supportive psychotherapy provided a good doctor-patient relationship is established and adverse medication effects rapidly dealt with. A cognitive framework and a Rorschach test can be valuable in deepening the understanding of individuals and obtaining a personalized view of their functioning and character dynamics. A biopsychosocial approach is essential in integrating all aspects of the patients' history in a meaningful way in order to provide adequate help.

Patient's perspective

"My life situation can't seem to get any better. I haven't had any support from anyone in all my life. Leaving home to go anywhere nowadays is hard and I can't seem to be able to stay anyplace else for a long time either. Just getting to the hospital [where the follow-up appointments are held] makes me very nervous, especially the minute I walk in. Can't seem to stay in place at all, just keep pacing while waiting for my appointment. I am only able to open up somewhat to my doctor, whom I thank for his support. Staying in hospital was close to impossible; I was very stressed and particularly concerned for my children, not being able to be close to them. I still need to have them near-by. Getting the MRI scan was also a stressful experience, confined in a small space with all that noise for so long. I succeeded only after getting extra medication.

I hope that things will get better. I don't trust anyone for any help any more; they should have helped me earlier."

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

stands for 'Post Traumatic Stress Disorder'

for 'Verbally Accessible Memory'

for 'Situationally Accessible Memory'

Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, Braff DL: Positive symptoms of psychosis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1996, 39: 839-844. 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00314-2.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Seedat S, Stein MB, Oosthuizen PP, Emsley RA, Stein DJ: Linking Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Psychosis: A Look at Epidemiology, Phenomenology, and Treatment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003, 191: 675-10.1097/01.nmd.0000092177.97317.26.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Nutt DJ: The psychobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000, 61: 24-29.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brewin CR, Holmes EA: Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003, 23: 339-376. 10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00033-3.

Wilson JP, Keane TM: Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. 2004, The Guilford Press

Google Scholar

Ehlers A, Clark DM: A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000, 38: 319-345. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable support and direction offered by the department's chair, Professor Ioannis Giouzepas who places the utmost importance in creating a suitable therapeutic environment for our patients and a superb learning environment for the SHO's and registrars in his department.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

2nd Department of Psychiatry, Psychiatric Hospital of Thessaloniki, 196 Langada str., 564 29, Thessaloniki, Greece

Georgios D Floros, Ioanna Charatsidou & Grigorios Lavrentiadis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Georgios D Floros .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GF was the attending SHO and the major contributor in writing the manuscript. IC performed the psychological evaluation and Rorschach testing and interpretation. GL provided valuable guidance in diagnosis and handling of the patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Floros, G.D., Charatsidou, I. & Lavrentiadis, G. A case of PTSD presenting with psychotic symptomatology: a case report. Cases Journal 1 , 352 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-352

Download citation

Received : 12 September 2008

Accepted : 25 November 2008

Published : 25 November 2008

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-352

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Ziprasidone

- Psychotic Disorder

- Amisulpride

- Hallucinatory Experience

Cases Journal

ISSN: 1757-1626

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- June 15, 2024 | VOL. 77, NO. 2 CURRENT ISSUE pp.43-100

- March 15, 2024 | VOL. 77, NO. 1 pp.1-42

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) for PTSD: A Case Study

- Alexandra Klein Rafaeli , Psy.D. ,

- John C. Markowitz , M.D.

New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Search for more papers by this author

Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), a time-limited, evidence-based treatment, has shown efficacy in treating major depressive disorder and other psychiatric conditions. Interpersonal Psychotherapy focuses on the patient’s current life events and social and interpersonal functioning for understanding and treating symptoms. This case report demonstrates the novel use of IPT as treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Preliminary evidence suggests IPT may relieve PTSD symptoms without focusing on exposure to trauma reminders. Thus IPT may offer an alternative for patients who refuse (or do not respond to) exposure-based approaches. Interpersonal Psychotherapy focuses on two problem areas that specifically affect patients with PTSD: interpersonal difficulties and affect dysregulation. This case report describes a pilot participant from a study comparing 14 weekly sessions of IPT to treatment with two other psychotherapies. We describe the session-by-session IPT protocol, illustrating how to formulate the case, help the patient identify and address problematic affects and interpersonal functioning, and to monitor treatment response.

Introduction

Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) is a time-limited, evidence-based treatment that focuses on patients’ social and interpersonal functioning, affect, and current life events. It is efficacious in treating major depression, bulimia, and other conditions ( Weissman et al., 2000 ). Developed by the late Gerald Klerman, M.D., and Myrna Weissman, Ph.D., IPT stems from the theoretical work of Harry Stack Sullivan and John Bowlby and from empirical research on the psychosocial aspects of depression. Sullivan (1953) viewed interactions with others as the most profound source of understanding one’s emotions, while Bowlby (1969) considered strong bonds of affection with others the foundation for individual well being. These theorists guide IPT practitioners as they explore their patients’ affective experiences through the lens of the social and the interpersonal.

Initial evidence suggests that IPT may also benefit patients with posttraumatic stress disorder ([PTSD]; Bleiberg & Markowitz, 2005 ; Campanini et al., 2010 ; Krupnick et al., 2008 ; Ray et al., 2010 ; Robertson et al., 2004 ; Robertson et al., 2007 ). There are at least two rationales for testing IPT for this population. First, IPT does not utilize exposure to trauma reminders. Although extensive evidence supports the efficacy of exposure-based therapies for PTSD (Grey, 2008), IPT offers an alternative to patients who may refuse exposure techniques or not respond to them. A recent review article suggested that highly traumatized patients who dissociate may fare better receiving affect-focused therapy than exposure-based therapy ( Lanius et al., 2010 ). Second, IPT works by improving patients’ interpersonal functioning and emotion regulation ( Markowitz et al., 2006 , 2009 ; Markowitz, 2010 ), which are commonly impaired in PTSD (APA, 2000) and therefore, important targets for change. Social support, which IPT helps patients to mobilize, has been shown to be a key factor in preventing and recovering from PTSD ( Brewin et al., 2000 ; Ozer et al., 2003 ).

PTSD is a psychiatric illness triggered by traumatic events: experiencing a natural disaster, witnessing a death, suffering chronic abuse, or otherwise facing a threat to one’s own life or physical integrity. Although most people (50% to 90%) encounter traumas during their lifetimes, only about 8% develop full PTSD ( Kessler et al., 1995 ). Symptoms of PTSD are distressing and often significantly impair social and occupational functioning.

Many forms of psychotherapy have been employed to address PTSD. Those with the strongest evidence base are forms of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which utilize controlled exposure to trauma reminders (Butler et. al., 2000). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy aims to solve problems by working towards changing patterns of irrational thinking or behavior linked to one’s negative emotions. The CBT approach involves exposure to the trauma either through imaginal confrontation of traumatic memories (Foa, 2003) or in vivo exposure to trauma reminders (Joseph, 2008).

In contrast to exposure-based CBT approaches, IPT eschews focusing on the trauma and instead concentrates on the patient’s current life events, particularly on social and interpersonal aspects ( Markowitz, 2010 ). The basic premise of IPT for PTSD is trauma shatters the patient’s sense of interpersonal safety, leading to withdrawal from interpersonal relationships and impaired ability to use social supports to process the traumatic event ( Markowitz et al., 2009 ). By withdrawing, individuals with PTSD cut off vital social supports needed when they are most vulnerable. Because they are interpersonally hypervigilant, emotionally detached or dysregulated, patients with PTSD mistrust relationships ( Bleiberg and Markowitz, 2005 ). Interpersonal Psychotherapy helps the patient to understand rather than avoid feelings, to tolerate such affects, to use them to enhance communication and effectively manage interactions with others, and thereby, to rebuild interpersonal trust. Finding ways to reconnect meaningfully to one’s surrounding world may reinstate severed social networks and reduce PTSD symptoms.

| • | (mourning the death of a significant other), | ||||

| • | (a struggle with a significant other, which the patient is inevitably losing), or | ||||

| • | (any major life change, including having suffered a traumatic event or events) ( ). | ||||

In a role transition, a life change costs the patient an old role and substitutes a new, unwanted one. Treatment helps the patient mourn the loss of the former and develop skills, interpersonal opportunities, and confidence in the latter, new role. Even an interpersonal trauma may have a silver lining.

Empirical Support

Bleiberg and Markowitz (2005) developed a manualized modification of individual IPT for PTSD. A small, open trial treating 14 patients with chronic PTSD yielded improvements across the three PTSD-DSM-IV-TR symptom clusters of hyper arousal, avoidance/numbing, and intrusive symptoms, in addition there were reductions in depression and anger and improvements in social functioning ( Bleiberg & Markowitz, 2005 ). An NIMH-funded, randomized controlled study is currently comparing three 14-week psychotherapies that employ very different mechanisms for treating chronic PTSD: 1) prolonged exposure ( Foa and Rothbaum, 1998 ); 2) IPT, focusing on interpersonal sequelae of PTSD rather than exposure to its traumatic triggers; and 3) relaxation, emphasizing reduction of anxiety through relief of physical tension ( Jacobson, 1938 ). This study will evaluate not only the efficacy of IPT for PTSD, but potential mediators and moderators of treatment outcome.

To illustrate IPT for PTSD, we present data from a pilot case that was not included in the current NIMH study, but served as a valuable training case. This patient received open IPT treatment for PTSD because his Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS, Blake et al., 1995 ) score of 45, while indicating moderate symptom severity ( Weathers et al., 2001 ), fell below the study inclusion threshold of 50 or above. This case served as training for a therapist who was new to the study. The patient exemplifies the complex presentation of most patients who meet DSM-IV criteria for PTSD, who generally report comorbidity ( Kessler et al., 1995 ). His response to treatment illustrates the use of IPT as an alternative approach to reducing PTSD symptoms without exposure techniques.

Mr. A., a 48-year-old male, worked from home as a freelance software engineer. He held a master’s degree in computer science and had worked successfully for many years as a computer programmer, but was currently working sporadically and struggling financially. He requested psychotherapy to address current symptoms of “irritability, sleep disturbance, and interpersonal conflicts.” He reported a history of multiple traumas that he felt contributed to his current difficulties. Although he described attempting to “accept the pain and suffering these past ordeals caused” and to “move on,” he often felt resentful and unable to forgive.

Mr. A. was raised in a blue-collar suburb of Philadelphia, living with his parents and two younger sisters. He reported feeling tremendous pressure to excel, which he attributed to his father’s continual dissatisfaction with Mr. A.’s accomplishments. He had few friends growing up, but was committed and loyal to those he did call friends. He had had a few short-term relationships when younger, was once briefly married, and had a daughter, Chloe, who was currently in her twenties. He described his marriage as “agreeable,” despite feeling the couple shared no common interests and lacked any “passionate connection.” He reported being strongly attached to Chloe from her infancy until age 2. During that interval, he carried out most parental duties while his wife recuperated from a serious back injury. He described his attachment to his daughter during this time as “the most harmonious bond I ever experienced with another human being.”

Mr. A. was currently living with his girlfriend of 7 years, Diane, age 38. He referred to this as a “9/11 relationship”: their first date was in New York on the eve of September 11, 2001, and he believed that the catastrophe brought them closer and created a mutual urgency to “settle down.” Had the terrorist attacks not occurred, he believed their relationship would not have lasted.

Mr. A. exhibited ambivalence about this relationship (and any longterm commitment). He shared a home with Diane, was extremely loyal and devoted, described her with affection, respect, and warmth, and even sometimes referred to her as his fiancée. He described his love for her as strictly platonic, however. They hadn’t been sexually intimate in years, and he saw her more as a “best friend” or “soul mate” than a future wife or mother.

Mr. A.’s description of his interactions with Diane reflected several characteristic behaviors of PTSD ( Markowitz et al., 2009 ). He depicted interactions at home as tense and at times explosive, and attributed these interpersonal struggles to an overall aversion to any “intense feelings.” He would get angry at Diane for intruding on his work space or on his chance to “relax” or “meditate in solitude.” He had created a work environment void of almost all social interaction and found Diane’s presence disturbed his plan, which was to distance himself enough from others so there would be no conflict. His general mistrust in others, another characteristic behavior of PTSD, also added to his uncertainty in his relationship with Diane. For example, Mr. A. had severed ties with Diane’s father over a failed business venture, but Diane continued communicating with him. As a consequence, Mr. A. questioned her fidelity.

Mr. A. reported a shift in his sexuality that he considered the primary cause of his diminished physical attraction towards Diane. Approximately one year before starting IPT, he had become strongly attracted to transsexuals and was daily pursuing contact with the community online. Through Mr. A.’s exploration of the transsexual community, he developed a close “cyber” relationship with Jane, a transsexual living abroad, with whom he frequently e-mailed and “chatted.” Apart from posting photographs online, however, they had never seen each other. Here too, his avoidance of intense feelings seemed to preclude any intimacy. For although he and Jane had discussed setting up a webcam so they could interact more (and even planned to one day meet in person) Mr. A. always stopped short of seeing through with the plans.

Mr. A. initially considered the recent shift in his sexuality a novel curiosity. During the therapy, however, he began to consider the possibility that this attraction was not novel, but part of a longer-standing confusion about sexual orientation.

Trauma History

Mr. A. reported multiple events in his past involving intense fear and humiliation. Some were indeed traumas as defined by the DSM-IV-TR criterion A for PTSD, where others would more appropriately be categorized as subjectively distressing events. Regardless of the clinical classification, each experience Mr. A. recounted evoked vivid and frightful memories. Mr. A.’s first memory dated back to his toddler years. He was told his mother had to stay in the hospital for several weeks after giving birth due to complications, and he would stay with his aunt and uncle. He worried that his mother would die in the hospital and that he would never see her again. He then recounted experiencing additional “emotional trauma” when his aunt “humiliated” him in front of a house full of family members by forcing him to rub his nose in the diaper he had soiled. He linked this memory of shame and disgrace to problems he had in adulthood with sexual intimacy. Mr. A. also recalled the same aunt and uncle so criticizing him for eating messily that it “felt like verbal abuse” and produced a severe food phobia. Other early traumas he revealed at intake included experiencing a hurricane firsthand (age 6) and physical assault by a group of peers in middle school.

The magnitude of Mr. A.’s horrific experiences had no bearing on the impression they left behind. For example, the hurricane and physical assault hardly affected his daily routine; however, his “humiliation” by his aunt (an event not meeting PTSD criterion A) shaped him for years to come. The trauma that most profoundly affected his functioning (DSM-IV criterion A) occurred after Mr. A. and his wife separated. He initially continued to see his child regularly. After several months, however, his wife abruptly abducted Chloe to her native country. Because she left no word for Mr. A., he had no knowledge of his daughter’s well-being or whereabouts for two days. Convinced she had been abducted, he feared for her life. Eventually, he learned that she was safe with her mother, but remained unable to contact or see her.

In the ensuing two years, Mr. A. devoted his life to locating and reconnecting with his daughter. He quit his job, moved to his ex-wife’s country, and immersed himself in custody and abduction law. That Chloe’s age was similar to his when he had first been “traumatized” held great significance for him: his mother had been “taken away,” leaving him fearful and anxious. This memory deepened his need to remain close to his daughter and never to let feel abandoned. A two-year international pursuit and custody battle ensued, including at least two threats on Mr. A.’s life by his ex-father-in law and someone he believed had been hired to kill him by his ex-wife’s family.

Mr. A. underwent a profound role transition with this life trauma. He often referred to his life before and after his daughter’s abduction as if describing two separate individuals: Pretrauma, he reported always having felt “a little mistrustful of others” and acknowledged lifelong “trouble with love and affection,” but was an active, functioning adult who held a full-time job, pursued various hobbies, and even, with some effort, participated in his community. Posttrauma, he struggled to function, to self-regulate, and to find meaning and purpose in his life. His social withdrawal was worsened, and despite seeking numerous therapies and self-help, his PTSD symptoms lingered.

Presenting Complaints

Hyperarousal symptoms.

Mr. A. reported feeling hyperalert and watchful, even when knowing there was no real need. In public settings he experienced moderate hypervigilance. He reported frequent, if brief, startle reactions. He described frequent (daily) intense anger and irritability; on most days, he took this anger out on Diane. Although able to recover relatively quickly from each anger outburst, he found his attempts to suppress anger exhausting, and he noted that the anger outbursts were damaging his relationship with Diane.

Avoidance/Numbing Symptoms

Mr. A. avoided activities, people, and places that evoked strong memories: e.g., phone calls from family members and parties where he might encounter individuals from his past. Avoidant behavior was pervasive: from the cocoon-like home environment, which permitted him to live in virtual isolation (he described choosing to work from home as “adaptive” given his history of interpersonal conflicts in work settings) to avoiding any possible reminder of Chloe’s abduction (he felt “more in control” at home, where he could carefully limit interactions with others). Although he did not meet criteria for substance abuse, he reported using marijuana three times a week and stated that he might not be able to stop using it during treatment. He also reported some loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities, such as sex and sports.

Intrusive symptoms

Although he presenting with a detached affective expression, Mr. A. became visibly upset (as though reliving experiences in the present) when reminded of past traumas or of instances when people betrayed him. Mr. A. reported intrusive daytime thoughts and occasional “bad dreams” about his traumas. The thoughts and nightmares impaired his concentration and made him anxious and uneasy “most of the day.” He described sleep as “chaotic,” compromised by his unstructured daily routine. As a consequence, he was often awake much of the night and then napped sporadically by day.

Other Symptoms

Mr. A. had concerns about his interactions with his most significant others. Although caring deeply for Diane, he worried that he could not reciprocate her romantic feelings for him. He could not imagine deepening their commitment through marriage or starting a family, and he often felt “too emotionally numb” to respond to Diane’s physical or emotional needs. Mr. A. also described considerable conflicts at home. He frequently “snapped” at Diane, and his discomfort with any physical intimacy she initiated caused constant tension between them. He spent most of his days on the computer, chatting online, or talking to his business partner by phone, and even those relatively detached interactions felt stressful.

Previous Treatments

Over the years, Mr. A. had participated in individual, group, and family therapy and had actively sought self-help solutions from books and websites. These had not relieved his ruminations about his distressing past nor helped him cope with high daily levels of anger and frustration. One psychodynamic treatment lasted several years. He also reported a briefer behavioral therapy with an exposure component, and family therapy. Exposure therapy had not helped to quell his anger and anxiety; he was only willing to share parts of his trauma narrative and had resisted any systematic in vivo or imaginal exposure techniques. Similarly, psychodynamic therapy had not reduced his symptoms. Mr. A.’s tendency to control conversations may have turned interpretations into debates. Despite participating in various psychotherapies, Mr. A. had never discussed his sexuality, focusing instead on past traumas.

An independent evaluator assessed Mr. A. using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale ([CAPS] Blake et al., 1995 ) and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression ([Ham-D] Hamilton, 1967 ). Although his scores were subthreshold for the PTSD study, based on his CAPS score (CAPS = 45) ( Weathers et al., 2001 ), he warranted a diagnosis of moderate PTSD. His baseline score on the PTSD Diagnostic Scale Self Report (PSS-SR; Foa, 1993) was 25, which is considered severe ( Foa et al., 2009 ). The Life-Events Checklist ( Johnson et al, 1980 ) and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders (First, 1997) were also administered at intake. Mr. A. met criteria for PTSD, chronic agoraphobia without panic disorder (both lifetime and current), and specific phobia (fear of food being mixed or touching; lifetime and present). Mr. A. was admitted as a pilot IPT case.

Because Mr. A. was not a formal participant, the independent evaluator did not readminister the CAPS following treatment. However, Mr. A. did complete the PSS-SR and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) ( Beck, et al, 1996 ) pre-, mid-, and post-treatment.

Treatment Overview

Mr. A.’s long history of avoidant behaviors and interpersonal conflicts made him appear a good candidate for IPT. Interpersonal Psychotherapy differs theoretically and technically from other PTSD treatments in targeting posttrauma sequelae of impaired interpersonal functioning rather than exposure and re-processing of the traumatic events themselves ( Markowitz, 2010 ). Interpersonal Psychotherapy-PTSD (Markowitz, et al, 2009) comprises 14 weekly sessions of 50-minutes each. The clinician largely devotes the initial two to three sessions to an “interpersonal inventory,” collecting information to identify current relationships, overall patterns of interpersonal behavior, and links between relationships and symptoms. The clinician then formulates the case, linking the DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis to an interpersonal focus that emerged in the assessment, and shares this formulation with the patient. Sessions 3 to 14 focus on addressing and resolving the interpersonal problem area (e.g., role transition); the therapist provides psychoeducation about PTSD as a treatable medical illness that is not the patient’s fault, and serially monitors symptoms. The final sessions focus on termination, an important interpersonal event but one that has been anticipated from the start of the time-limited therapy.

Sessions 1 to 3: Initial phase

Goals for these sessions included exploring in detail Mr. A.’s current and past relationships to understand his interpersonal functioning, to identify interpersonal issues linked to the onset of PTSD symptoms, and to take a trauma history. The therapist first explained the IPT approach to Mr. A. He acknowledged the prominent interpersonal difficulties in his current life and expressed his eagerness r to work on changing his behaviors. The therapist then reviewed Mr. A.’s current PTSD symptoms, which were based on the PSS-SR results. She observed that his avoidance symptoms were the most prominent. She took a general history of traumas throughout Mr. A.’s life. Mr. A. noted that each trauma involved a profound sense of betrayal, which led him to mistrust people and to avoid forming close relationships.

The most important people in Mr. A.’s life were his girlfriend Diane and his daughter Chloe. He felt that his traumas negatively affected both relationships. He was irritable with Diane, and he avoided close contact with Chloe to avoid being hurt. He cited similar problems in other relationships, and reported that the “major trauma” of his life, Chloe’s abduction, unquestionably exacerbated this distancing tendency.

Mr. A. often attempted to advise and guide others, considering that he related to others best by imparting knowledge. Unfortunately, his guidance was often unsolicited and not well accepted. This behavior also arose almost immediately in IPT sessions. Mr. A. elaborated in great detail how particular computer programs worked or what he had learned in a recent self-help class. He would talk without pause for several minutes, despite the therapist’s attempts to interject. This tactic succeeded in avoiding any guidance from the therapist.

A similar process unfolded with his daughter, who had recently expressed interest in studying law. Upon hearing this, Mr. A. began telling her all of the details of his custody battle with her mother, including an enormous number of personal and confidential documents. He deemed this a supportive act; she did not.

Mr. A. admitted that his concept of relationships and his approaches to others often left him feeling distant from the very people he cared for most. At times he felt “betrayed” after doing “so much.” For example, early in his relationship with Diane, her father developed a rare illness. Mr. A. immediately took it upon himself to research extensively alternative treatments. Mr. A. felt he was instrumental in saving her father’s life, but never felt recognized for it.

After Chole and Mr. A. were reunited, he was hurt by Chloe’s decision to live with her mother rather than with him. He also still grieved his lost bond with Chloe when she was a baby, a bond defining to him the purest and most powerful of connections. Although he admitted having struggled for many years with feeling comfortable in romantic relationships and with physical intimacy, he believed this struggle worsened after the abduction.

Mr. A. had trouble accepting affection from Diane. When they met they had sex regularly, but in recent years they stopped sleeping in the same bed and had only been intimate once in recent years. He summarized a recent, deliberate attempt to rekindle passion between them as “the attempt failed.” Diane frequently desired physical closeness, and although he cared for her and wanted to reciprocate the affection for her sake, he found himself recoiling from her touch. He described her as “coming at him” too fast with a hug or a kiss, and he experienced excruciating discomfort from any physical touch.

Just as Mr. A. sought solutions for his “PTSD,” he spent time seeking an explanation for his intimacy difficulties. He began questioning his sexuality, past and present. In his past, he had felt most comfortable with female bisexual partners, and was often told he “made love like a woman.” He felt an unusual bond in his recent online relationship with Jane, a male-to-female transsexual. Extremely attracted to her, he also felt he could be more open and honest online, whereas at home he had to feign interest and affection. He wondered whether this recent attraction stemmed from an online self-help course that encouraged attunement with both his “left” and “right” brain. Attraction to a transsexual, he opined, tapped into his “middle-brain.”

Mr. A. believed yoga, meditation, and spirituality helped him to feel more “balanced.” He stated his primary goal was to become more “disciplined” and “even tempered,” “like the Dalai Lama.” Nonetheless, he continued to struggle with self-regulation in interpersonal situations. His spiritual exercises, all solitary in nature, were not aiding his quest for equilibrium; on the contrary, they enabled Mr. A. to continue avoiding interpersonal contact and any strong emotions such exchanges might evoke.

Ipt Case Formulation

The IPT formulation concisely links symptoms to the focal interpersonal problem area. The formulation, presented as feedback at the end of the initial phase, draws on information gathered from the interpersonal inventory and provides an organizing focus for the remainder of therapy:

I understand from our initial meeting that your interpersonal goals are to be closer to Chloe and to reduce disputes with Diane. I also understand that you’ve always experienced interpersonal difficulties, but that they grew much worse after your daughter’s abduction-triggered PTSD. You have clearly worked hard over the years to overcome problems you’ve had in social arenas, and you’ve tried numerous times to address the painful memories of past traumas that still live with you today .

Your PTSD symptoms still overshadow your feelings and actions. You feel overwhelmed by both your emotions and your environment. Your symptoms are also coupled with an important current life issue you say has you’ve never discussed in past treatments: your sexual identity. Through understanding yourself in relationship to others, you cam mend your social conflicts and reduce your symptoms .

You’ve discussed how hard it is to trust people, and how that has limited your social network for years. Your wife’s abduction of Chloe took away the person closest in the world to you, and has made it extremely difficult—to this day—for you to trust others, to take the risk to connect with those around you. This mistrust is very common in PTSD. Avoidance, numbing, intrusive thoughts are all symptoms of the illness. Although you say that you always had difficulty in social situations, these symptoms are not necessarily part of your character; they’re indication of an illness that you suffer from—an illness that’s treatable and not your fault. The symptoms can improve .

Your mistrust has led you to minimize social contact. You’ve discussed feeling “betrayed ” or “deceived ” after trying to help others many times over .

So you’ve been keeping your distance through “ electronic relationships ” that are more comfortable. Yet, you say you “yearn for closer, more real relationships!”

You are going through a role transition: Uncomfortable feelings about your relationships and your own sexuality have made life extremely confusing, and it’s hard for you to know what you want from whom. What we can work on in the remaining weeks of treatment is how to navigate this transition: Do you want to stay with Diane, deepen a relationship with Jane, or what? If you can understand your feelings and use them to resolve this uncertainty, not only will your life feel better, but you symptoms are likely to subside. Does that make sense to you?

Mr. A. agreed to work on this interpersonal focus.

Session 4 to 10: Middle Phase

Having agreed to focus on his role transition, Mr. A. and the therapist entered the middle phase of IPT. Mr. A. now understood that he was suffering from a treatable illness that was not his fault, with clinical symptoms related to his past traumas. He would learn to detect and monitor these symptoms in the course of therapy, but should not blame himself for having symptoms or for their impact on his relationships. In all likelihood, he would start to feel better and see the symptoms subside.

In his role transition, Mr. A.. was adjusting to changes in what and who attracted him sexually. The therapist introduced strategies to improve interpersonal communication, and helped elicit emotional responses that surfaced in the process. She supported Mr. A. in confronting and wrestling with intense (particularly negative) feelings. Mr. A. also needed to understand that his tendencies to intellectualize emotional experiences and to defend against any unpleasant moods complicated this shift. Tolerating his affects would help him become more connected with others and more open with his sexuality.

The therapist helped him to examine closely current conflicts and arguments. This would help Mr. A. determine what he wanted in these situations and explore interpersonal options, including role play to practice responses, to resolve them. Specific incidents from the week were reviewed, eliciting Mr. A.’s feelings and behaviors, and sessions offered a chance to practice and hone interpersonal skills.

“How have things been since we last met?”

This simple question starts every IPT session. It anchors both therapist and patient by focusing on current feelings and life events related to the focal problem area (role transition) and by eliciting current concrete interpersonal incidents on which to draw when discussing alternative interpersonal techniques ( Weissman et al., 2000 ). Mr. A. could seldom recall any events from his week to discuss and instead, chose to recount stories from his past. His week, after all, intentionally avoided interpersonal encounters; he thought there was little to recount. Alternatively, he would offer a detailed description of a computer program he was developing, dive into monologues about what it takes to be an effective software engineer, or return to his distant past. This parrying the opening IPT question was a fundamental challenge in the treatment.

The therapist persisted in probing each week, seeking to guide Mr. A. to the here and now and away from the distant stories indelibly fixed in his mind. Despite his cocoon-like existence, Mr. A. had interactions with others, though he may have wanted to avoid the affect attached to recent arguments with Diane, or an emotionally charged phone call with Chloe, or a negative response from an online communication.

Mr. A.’s communication style was intellectualized, emotionally detached, expressed in abstract theoretical rather than experiential verbiage. When asked a simple question like, “How did that make you feel?” he responded with an analysis of how his “left brain” was dictating his behavior, making it impossible for his creative, emotional “right brain” to respond. The therapist challenged him to explore the feelings he consistently ignored or avoided, using his vocabulary as an illustration. She suggested that such detached language contributed to his distancing himself from the real feelings situations evoked. She urged him to retell day-to-day encounters using emotional words and describing his momentary experience. Again, the focus was on everyday interactions rather than a review of his trauma experiences, which were in this case, too well rehearsed to evoke genuine emotion. The therapist would then return to the initial question: “How have things been since we last met?”

It was frustrating when, at first, Mr. A. couldn’t break old habits. The therapist felt as Chloe must have when she hoped for her father’s support but instead got a lecture, or Diane might have when trying to connect with him, only to be repeatedly rebuffed. Mr. A. clearly cared deeply about his relationships and suffered from his isolation, but he made it almost impossible to break through the veneer.

By Session 6, Mr. A. was better able to recount specific events from his week, and was willing to take greater emotional risks when feelings surfaced. He described a telephone conversation with Chloe in which they talked more openly about their current lives. He still wished he could have influenced her life decisions (e.g., career choice) and values. He also recognized that many of the feelings he often avoided or suppressed related to his daughter. His years of grieving about time lost with Chloe no longer mattered as much to him as did the importance of their current relationship. He then attributed his current qualms about having children with Diane to regrets and losses surrounding Chloe and to his generalized loss of trust in other people.

The therapist introduced role play for improving Mr. A.’s ability to communicate with his significant others. She encouraged him to limit his phone interactions and increase face-to-face meetings with his business partner. In such meetings, Mr. A. could break his isolation, better read facial and body cues, and circumvent conflict. The therapist clarified that this was not a form of exposure, rather a technique for relating to others better. Mr. A. was initially uncomfortable with this until they role-played scenarios in session.

The therapist encouraged Mr. A. to recognize when he was frustrated or angry with Diane and tell her. With practice, he gradually saw the benefit of this approach in preventing angry outbursts. Similarly, when Jane suddenly broke off on-line communication, the therapist encouraged Mr. A. to confront her rather than avoid the behavior’s meaning and the hurt feelings it evoked. The therapist validated and normalized these negative affects as useful indicators of social encounters.

The therapist used IPT’s medical model and designation of the “sick role” ( Weissman et al., 2000 ) throughout the middle phase to underscore that Mr. A.’s symptoms were not his personality or a personal failing. As Mr. A.’s PTSD symptoms had lingered for decades, he had, unsurprisingly, come to confuse the disorder with his character. He had internalized symptoms, such as avoidance, startle responses, and irritability, as if they were fixed traits he could only manage, not dissolve. With time, he began to recognize the symptoms were not his character and not his fault. Through understanding his emotions and their role in daily minor encounters, he could reduce them so that he would merely experience healthy anxiety when reminded of traumas.

Just as Mr. A. had believed initially that PTSD an intractable part of himself, he also believed that strong feelings, such as anger or sorrow, could produce only negative outcomes. The therapist supported Mr. A. in confronting, rather than avoiding, intense (particularly negative) feelings. Each time he retreated into intellectualized language, she asked him to describe how he was feeling at that moment. Acknowledging, and simply sitting with an intense emotion, was his most challenging task.

This piece of the treatment was crucial, and is central to understanding how IPT differs from other affect-based therapies. Learning to acknowledge one’s emotions and to experience them more deeply is a shared core principle. However, in IPT the patient learns to understand a particular emotion as a response in an interpersonal context and then to communicate the feeling to improve an important relationship. Mr. A. did this with his irritability: his anger outbursts resulted from avoiding or suppressing intense feelings. If he could express his fears, anxiety, or disappointments with Diane as they surfaced, he was less likely to angrily “explode.” He practiced talking with Diane about his feelings when they were at peace, using “I” statements to avoid accusing or attacking language. He also shifted his communication of his feelings during sessions. Instead of “educating” the therapist, he now was willing to verbalize emotions and to explore their interpersonal context.

As the termination phase neared, an evaluator reassessed Mr. A.’s symptoms. His PSS-SR scores improved dramatically, falling from 25 at the start of treatment to 9 by session 8, indicating that he no longer met full criteria for PTSD. His BDI score remained euthymic, falling from 7 to 6.

Early in treatment, Mr. A. had responded hesitantly to techniques the therapist suggested, hiding behind intellectualization and refusing to focus on the present. He progressed as he became more willing to leave his comfort zone and to acknowledge that negative affects are not “bad,” but that sadness, loss, anger, are all useful, socially informative feelings if tolerated. This was a profound shift. He noticed he was becoming less irritable with Diane and his business partner and was less avoidant of social situations. He came to sessions more willing to discuss recent events and resultant feelings. He said this would never come easily or “naturally,” but he saw the benefit in trying. As a result, he felt better.

Session 11-14: Termination Phase

The final sessions reviewed the treatment course and addressed Mr. A.’s progress, his developing skills, and his feelings about ending therapy. The therapist acknowledged the sadness of separation, yet focused on the gains he had made, and reviewed areas where Mr. A. felt more competent and independent to function without therapy. Together they tried to anticipate difficulties that might resurface after treatment. Mr. A. recognized his progress, but voiced disappointment that treatment was ending and wanted to discuss ways to continue. He viewed “endings” negatively, recalling his childhood separation from his parents, his marriage, and his relationship with his daughter. He feared that parting would only bring gloom and helplessness, as it had in his past.

The therapist presented termination as a potentially corrective experience: Mr. A. could work through the feelings that arose in saying goodbye, and potentially, see that not only could he tolerate such emotions, but also that he deserved a sense of completion, mastery of skills, and progress.

At termination, Mr. A. was more socially engaged and communicated more effectively. He now considered his shift in sexuality more a curiosity than a bona fide change in identity, and decided his relationship with Diane was worth nurturing. He became more affectionate with Diane, talking with her more openly about both their future and his past. Diane knew about Chloe’s abduction, but not about the related traumas that contributed to Mr. A.’s fears of intimacy and lasting relationships. She also knew about his online relationship, but their discussions had never gotten past angry, jealous exchanges, so that she had been unaware of his longer standing sexual confusion. Mr. A. also reported that he felt his relationship with his daughter had improved. They talked more and she involved him more in her daily life.

In anticipating difficulties post treatment, Mr. A. expected his “poor people skills” would never remit, and he would need to continue practicing communication skills and challenging himself to approach people. He felt more capable of tolerating negative moods and better able to bounce back from conflicts. Mr. A. reported still thinking about past traumas and the people who had been disloyal to him over the years, but this occurred less often and less intensely.

Assessment of Progress

Mr. A.’s scores on the PSS-SR remained at 9 at session 14. Thus, by the end of the protocol, he was well below the cutoff score for PTSD criteria. His reports indicated improved daily functioning. Although his work schedule continued to disturb his sleep pattern, he reported less nocturnal anxiety. He reported less anger and irritability towards Diane and less conflict at home. He cited an improved relationship with Chloe, and increased hope of restoring their past bond. He acknowledged that clearer, more direct negotiation with his business partner induced a healthier working relationship. Finally, he decreased cannabis use from at least three times a week, to “as needed,” approximately once a week.

Complicating Factors During the Course of Treatment

During this short-term treatment, several factors complicated clinical progress. Mr. A. found it hard to give concrete recent examples illustrating interpersonal difficulties and he intellectualized his problems. A second, related complication was Mr. A.’s smorgasbord of past therapy approaches. He often arrived with a list of items to discuss and had difficulty shifting focus. His rigid preparation for sessions made it hard for the therapist to structure treatment. Similarly, Mr. A.’s “teacher” role interfered with the patient role and he thus avoided affect and interpersonal closeness. Finally, although Mr. A. did not meet full criteria for substance abuse or dependence, his habitual cannabis use was maladaptive.

Treatment Implications

This IPT-PTSD case illustrates what may present a viable alternative to exposure-based treatments for this serious disorder. The patient described grappled for more than 20 years with the aftereffects of a personal trauma. Despite numerous therapies and attempts at self-help, his PTSD had persisted. Neither exposure therapy nor long term psychodynamic therapy had helped to quell his anger, anxiety, and avoidance.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy-PTSD offered Mr. A. a chance to understand himself through his feelings and relationships subsequent to the trauma. No formal exposure techniques were used; instead, IPT-PTSD focused on the patient’s feelings in current interpersonal relationships through decision and communication analyses. The PTSD symptoms appeared to diminish through the processes of understanding feelings and relationship patterns and the slow building of social support.

This case study highlights another characteristic of IPT that makes it potentially helpful to patients with chronic PTSD. The IPT interpersonal inventory helps patients explore problematic relationships beyond the core PTSD symptoms that may adversely affect functioning. Mr. A. struggled with his sexuality. The more he discussed this, the more he connected it to his relationships and PTSD symptoms. Had the therapy focused exclusively on re-exposure to trauma reminders, this key issue might never have surfaced. Yet, the interpersonal issues bordering this patient’s daily functioning were paramount to his dilemma and his progress.

Acknowledgement:

Supported in part by grant R01 MH079078 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

American Psychiatric Association . ( 2000 ). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association. Google Scholar

Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., & Brown, G.K. ( 1996 ). Manual for Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II). San Antonio, TX, Psychology Corporation,. Google Scholar

Blake, D. D., Weathers, F. W., Nagy, L. M., Kaloupek, D. G., Gusman, F. D., Charney, D. S., & Keane, T. M. ( 1995 ). The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress ,;8, 75-90. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Bleiberg, K.L., Markowitz, J.C. ( 2005 ). Interpersonal psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry ; 162,181-3. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Bowlby J. ( 1969 ). Attachment . New York, NY: Basic Books. Google Scholar

Brewin, C.R, Andrews, B., & Valentine, J.D. ( 2000 ). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 68, 748-766. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Butler, A.C., Chapman, J.E., Forman, E.M., & Beck, A.T. ( 2006 ). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review , 26, 7-31. Crossref , Google Scholar

Campanini, R.F., Schoedl, A.F., Pupo, M.C., Costa, A.C., Krupnick, J.L., & Melo, M.F. ( 2010 ). Efficacy of interpersonal therapy-group format adapted to post-traumatic stress disorder: an open-label add-on trial. Depression and Anxiety , 72-77. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Foa, E.B., Rothbaum, B.O. ( 1998 ) Treating the Trauma of Rape: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for PTSD . New York, NY: Guilford Press. Google Scholar

Foa, E.B., Riggs, D.S, Dancu C.V, & Rothbaum, B.O. ( 1993 ) Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder . Journal of Traumatic Stress , 6, 459-473. Crossref , Google Scholar

Foa, E.B., Keane,T.M., & Friedman, M.J. ( 2009 ) Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International . Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Guilford Press. Google Scholar

Foa, E.B, Rothbaum, B., & Furr, J. ( 2003 ) Augmenting exposure therapy with other CBT procedures . Psychiatric Annals , 33, 47-56. Crossref , Google Scholar

Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness . ( 1967 ). British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 6, 278-96. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Jacobson, E. ( 1938 ) Progressive Relaxation . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Google Scholar

Johnson, J.H., McCutcheon, S.M. ( 1980 ) Life Events Checklist . Hemisphere Publishing Corporation. Google Scholar

Joseph, J.S., Gray, M.J. ( 2008 ). BAO Exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder . Journal of Behavior Analysis of offender and Victim: Treatment and Prevention 1, 69-80. Crossref , Google Scholar

Kessler, R.C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., & Nelson, C.B. ( 1995 ). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry , 52, 1048-60. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Klerman, G.L., Weissman, M.M., Rounsaville, B.J., & Chevron, E. ( 1984 ). Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. New York, NY: Basic Books. Google Scholar

Krupnick, J.L., Green, B.L., Stockton, P., Miranda, J., Krause, E., & Mete, M. ( 2008 ) Group interpersonal psychotherapy with low-income women with posttraumatic stress disorder . Psychotherapy Research ,18, 497-507. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Lanius, R.A., Vermetten, E., Loewenstein, R.J., Brand, B., Schmahl, C. Bremner, J.D., & Spiegel, D. ( 2010 ) Emotion modulation in PTSD: clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype . American Journal of Psychiatry , 167, 640-647. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Markowitz, J.C. : ( 2010 ) Cutting Edge: IPT and PTSD . Depression and Anxiety , 27:879-881. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Markowitz, J.C., Milrod, B., Bleiberg, K.L., & Marshall, R.D. ( 2009 ) Interpersonal factors in understanding and treating posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Practice , 15, 133-140. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Markowitz, J.C., Bleiberg, K.L., Christos, P., & Levitan, E. ( 2006 ) Solving interpersonal problems correlates with symptom improvement in interpersonal psychotherapy: preliminary findings . Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease , 194, 15-20. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Ozer, E.J., Best, S.R., Lipsey, T.L., & Weiss, D.S. ( 2003 ) Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin , 129, 52-73. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Ray, R.D., & Webster, R. ( 2010 ) Group Interpersonal Psychotherapy for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study . International Journal of Group Psychotherapy , 60, 131-140. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Robertson, M., Rushton, P.J., Bartrum, M.D., & Ray, R. ( 2004 ) Group-Based Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects . International Journal of Group Psychotherapy , 54, 145-175. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Robertson, M., Rushton, P, Batrim, D., Moore, E., & Morris, P. ( 2007 ) Open trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder . Australasian Psychiatry , 15, 375-379. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

Sullivan, H.S. ( 1953 ). The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. New York, NY: Norton. Google Scholar

Weissman, M.M., Markowitz, J.C., Klerman, G.L. ( 2000 ) Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy . New York: Basic Books. Google Scholar

Weathers, F.W., Keane, T.M., & Davidson,J.R.T. ( 2001 ) Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: a review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiet,y 13, 132-156. Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

- Interpersonal psychotherapy for traumatic grief following a loss due to COVID-19: a case report 29 September 2023 | Frontiers in Psychiatry, Vol. 14

- Survivor‐led relational psychotherapy and embodied trauma: A qualitative inquiry 4 October 2020 | Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, Vol. 21, No. 3

- An Illustration of Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Perinatal Depression Case Reports in Psychiatry, Vol. 2020

- The Moderating Role of Child Maltreatment in Treatment Efficacy for Adolescent Depression 21 July 2020 | Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, Vol. 48, No. 10

- PROTOCOL: Effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy in comparison to other psychological and pharmacological interventions for reducing depressive symptoms in women diagnosed with postpartum depression in low and middle‐income countries: A systematic review 25 February 2020 | Campbell Systematic Reviews, Vol. 16, No. 1

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Gender Dysphoria in a Transgender Woman 13 December 2019 | Archives of Sexual Behavior, Vol. 49, No. 2

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy for PTSD

- Yearbook of Psychiatry and Applied Mental Health, Vol. 2013

- Treating Patients Who Strain the Research Psychotherapy Paradigm Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, Vol. 200, No. 7

- Posttraumatic stress disorder

- interpersonal psychotherapy

- affect dysregulation

- interpersonal difficulties

EMDR Case Studies

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Rebecca

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Rebecca PTSD UK Supporter Rebecca initially shared her EMDR experience on her own website, but has given us permission to

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Ranya

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Ranya Ranya* grew up in a violent and abusive household which led to her developing PTSD. In this case study,

Case Study: EMDR Treatment for Children – AJ

Case Study: EMDR Treatment for Children – AJ After a humiliating experience at school, AJ developed PTSD. Following panic attacks and other symptoms he underwent

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Chris

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Chris Chris developed severe PTSD after being struck from behind by a lorry while on duty as a Police Officer.

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Rachael

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Rachael Rachael was diagnosed with PTSD as a result of the horrific symptoms she experienced following a surgery. Unfortunately, Rachael

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Emily

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Emily Emily underwent EMDR treatment over Zoom to treat her PTSD following a trauma in her job as a Police

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Alani

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Alani After her son was hit by a distracted driver, and in ICU for 6 weeks, Alani developed PTSD. She

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Emma

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Emma After witnessing her husband having a terrifying seizure, Emma was diagnosed with PTSD. She underwent EMDR treatment and in

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Jenna

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Jenna Jenna* was diagnosed with PTSD as a result of an ‘incomplete’ miscarriage and the inconsistent and traumatic care that

Case Study: Sam’s EMDR Treatment

Case Study: Sam’s EMDR Treatment Sam underwent EMDR treatment after being diagnosed with C-PTSD following multiple and sustained traumas in childhood. Here, Sam explains more

Case Study: Jasmine’s EMDR Treatment

Case Study: Jasmine’s EMDR Treatment Jasmine underwent EMDR treatment after being diagnosed with PTSD following a trauma. Here, Jasmine explains more about her EMDR treatment,

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Sophie

Case Study: Sophie’s EMDR Treatment Sophie* underwent EMDR treatment after being diagnosed with PTSD following a trauma. Here, Sophie explains more about her EMDR treatment,

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Darren

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Darren Darren* was diagnosed with PTSD as a result of a medical emergency and underwent EMDR treatment which he says

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Claudia

Case Study: EMDR Treatment – Claudia Claudia* was diagnosed with PTSD as a result of a number of traumatic events in her life and underwent

Case Study: EMDR treatment-Melissa

Case Study: Melissa’s EMDR Treatment Melissa* underwent EMDR treatment after being diagnosed with PTSD following a medical emergency which resulted in an induced coma. Here,

Hello! Did you find this information useful?

Please consider supporting ptsd uk with a donation to enable us to provide more information & resources to help us to support everyone affected by ptsd, no matter the trauma that caused it, ptsd uk blog.

You’ll find up-to-date news, research and information here along with some great tips to ease your PTSD in our blog.

Finding Safety After Trauma – Guest Blog: Finley De Witt In this guest blog by Finley De Witt, Finley explores how to regain a sense of safety after experiencing trauma. Drawing from their experiences as a trauma practitioner and client,

Sunflower Conversations

Sunflower Conversations with PTSD UK We’re delighted to be working alongside the team at Hidden Disabilities Sunflower to raise awareness of PTSD and C-PTSD, and this month, they invited our Business development Manager, Rachel to appear on their podcast… You

PTSD Awareness Day 2024