- Our Mission

How Teachers Can Learn Through Action Research

A look at one school’s action research project provides a blueprint for using this model of collaborative teacher learning.

When teachers redesign learning experiences to make school more relevant to students’ lives, they can’t ignore assessment. For many teachers, the most vexing question about real-world learning experiences such as project-based learning is: How will we know what students know and can do by the end of this project?

Teachers at the Siena School in Silver Spring, Maryland, decided to figure out the assessment question by investigating their classroom practices. As a result of their action research, they now have a much deeper understanding of authentic assessment and a renewed appreciation for the power of learning together.

Their research process offers a replicable model for other schools interested in designing their own immersive professional learning. The process began with a real-world challenge and an open-ended question, involved a deep dive into research, and ended with a public showcase of findings.

Start With an Authentic Need to Know

Siena School serves about 130 students in grades 4–12 who have mild to moderate language-based learning differences, including dyslexia. Most students are one to three grade levels behind in reading.

Teachers have introduced a variety of instructional strategies, including project-based learning, to better meet students’ learning needs and also help them develop skills like collaboration and creativity. Instead of taking tests and quizzes, students demonstrate what they know in a PBL unit by making products or generating solutions.

“We were already teaching this way,” explained Simon Kanter, Siena’s director of technology. “We needed a way to measure, was authentic assessment actually effective? Does it provide meaningful feedback? Can teachers grade it fairly?”

Focus the Research Question

Across grade levels and departments, teachers considered what they wanted to learn about authentic assessment, which the late Grant Wiggins described as engaging, multisensory, feedback-oriented, and grounded in real-world tasks. That’s a contrast to traditional tests and quizzes, which tend to focus on recall rather than application and have little in common with how experts go about their work in disciplines like math or history.

The teachers generated a big research question: Is using authentic assessment an effective and engaging way to provide meaningful feedback for teachers and students about growth and proficiency in a variety of learning objectives, including 21st-century skills?

Take Time to Plan

Next, teachers planned authentic assessments that would generate data for their study. For example, middle school science students created prototypes of genetically modified seeds and pitched their designs to a panel of potential investors. They had to not only understand the science of germination but also apply their knowledge and defend their thinking.

In other classes, teachers planned everything from mock trials to environmental stewardship projects to assess student learning and skill development. A shared rubric helped the teachers plan high-quality assessments.

Make Sense of Data

During the data-gathering phase, students were surveyed after each project about the value of authentic assessments versus more traditional tools like tests and quizzes. Teachers also reflected after each assessment.

“We collated the data, looked for trends, and presented them back to the faculty,” Kanter said.

Among the takeaways:

- Authentic assessment generates more meaningful feedback and more opportunities for students to apply it.

- Students consider authentic assessment more engaging, with increased opportunities to be creative, make choices, and collaborate.

- Teachers are thinking more critically about creating assessments that allow for differentiation and that are applicable to students’ everyday lives.

To make their learning public, Siena hosted a colloquium on authentic assessment for other schools in the region. The school also submitted its research as part of an accreditation process with the Middle States Association.

Strategies to Share

For other schools interested in conducting action research, Kanter highlighted three key strategies.

- Focus on areas of growth, not deficiency: “This would have been less successful if we had said, ‘Our math scores are down. We need a new program to get scores up,’ Kanter said. “That puts the onus on teachers. Data collection could seem punitive. Instead, we focused on the way we already teach and thought about, how can we get more accurate feedback about how students are doing?”

- Foster a culture of inquiry: Encourage teachers to ask questions, conduct individual research, and share what they learn with colleagues. “Sometimes, one person attends a summer workshop and then shares the highlights in a short presentation. That might just be a conversation, or it might be the start of a school-wide initiative,” Kanter explained. In fact, that’s exactly how the focus on authentic assessment began.

- Build structures for teacher collaboration: Using staff meetings for shared planning and problem-solving fosters a collaborative culture. That was already in place when Siena embarked on its action research, along with informal brainstorming to support students.

For both students and staff, the deep dive into authentic assessment yielded “dramatic impact on the classroom,” Kanter added. “That’s the great part of this.”

In the past, he said, most teachers gave traditional final exams. To alleviate students’ test anxiety, teachers would support them with time for content review and strategies for study skills and test-taking.

“This year looks and feels different,” Kanter said. A week before the end of fall term, students were working hard on final products, but they weren’t cramming for exams. Teachers had time to give individual feedback to help students improve their work. “The whole climate feels way better.”

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

Published on January 27, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

Table of contents

Types of action research, action research models, examples of action research, action research vs. traditional research, advantages and disadvantages of action research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about action research.

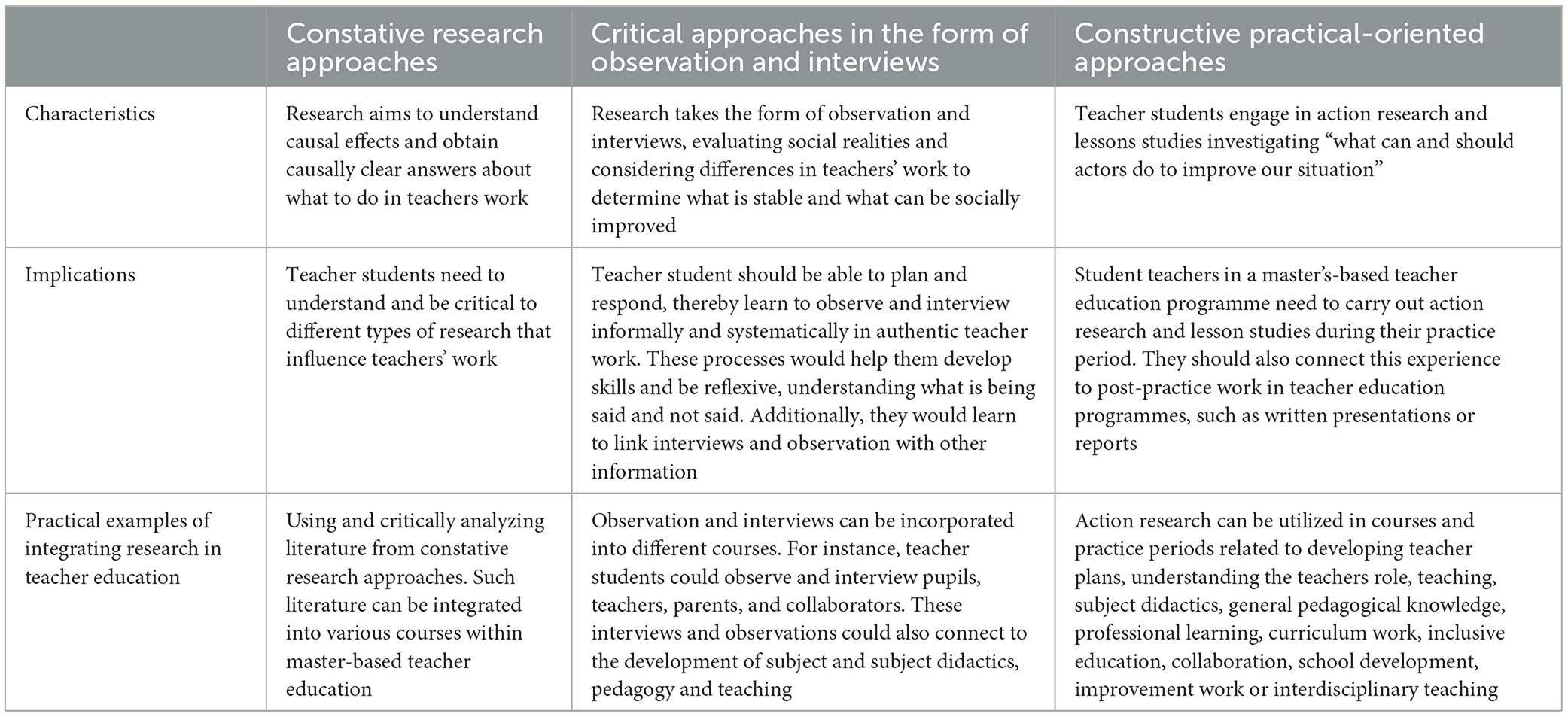

There are 2 common types of action research: participatory action research and practical action research.

- Participatory action research emphasizes that participants should be members of the community being studied, empowering those directly affected by outcomes of said research. In this method, participants are effectively co-researchers, with their lived experiences considered formative to the research process.

- Practical action research focuses more on how research is conducted and is designed to address and solve specific issues.

Both types of action research are more focused on increasing the capacity and ability of future practitioners than contributing to a theoretical body of knowledge.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Action research is often reflected in 3 action research models: operational (sometimes called technical), collaboration, and critical reflection.

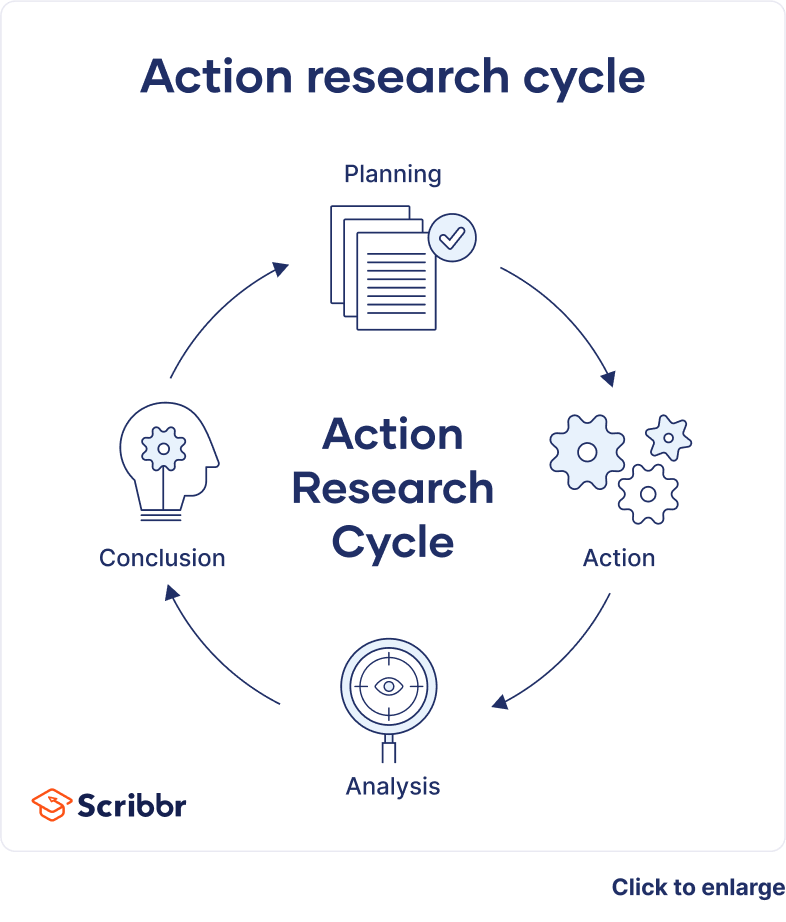

- Operational (or technical) action research is usually visualized like a spiral following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

- Collaboration action research is more community-based, focused on building a network of similar individuals (e.g., college professors in a given geographic area) and compiling learnings from iterated feedback cycles.

- Critical reflection action research serves to contextualize systemic processes that are already ongoing (e.g., working retroactively to analyze existing school systems by questioning why certain practices were put into place and developed the way they did).

Action research is often used in fields like education because of its iterative and flexible style.

After the information was collected, the students were asked where they thought ramps or other accessibility measures would be best utilized, and the suggestions were sent to school administrators. Example: Practical action research Science teachers at your city’s high school have been witnessing a year-over-year decline in standardized test scores in chemistry. In seeking the source of this issue, they studied how concepts are taught in depth, focusing on the methods, tools, and approaches used by each teacher.

Action research differs sharply from other types of research in that it seeks to produce actionable processes over the course of the research rather than contributing to existing knowledge or drawing conclusions from datasets. In this way, action research is formative , not summative , and is conducted in an ongoing, iterative way.

| Action research | Traditional research | |

|---|---|---|

| and findings | ||

| and seeking between variables | ||

As such, action research is different in purpose, context, and significance and is a good fit for those seeking to implement systemic change.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Action research comes with advantages and disadvantages.

- Action research is highly adaptable , allowing researchers to mold their analysis to their individual needs and implement practical individual-level changes.

- Action research provides an immediate and actionable path forward for solving entrenched issues, rather than suggesting complicated, longer-term solutions rooted in complex data.

- Done correctly, action research can be very empowering , informing social change and allowing participants to effect that change in ways meaningful to their communities.

Disadvantages

- Due to their flexibility, action research studies are plagued by very limited generalizability and are very difficult to replicate . They are often not considered theoretically rigorous due to the power the researcher holds in drawing conclusions.

- Action research can be complicated to structure in an ethical manner . Participants may feel pressured to participate or to participate in a certain way.

- Action research is at high risk for research biases such as selection bias , social desirability bias , or other types of cognitive biases .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.

Action research is focused on solving a problem or informing individual and community-based knowledge in a way that impacts teaching, learning, and other related processes. It is less focused on contributing theoretical input, instead producing actionable input.

Action research is particularly popular with educators as a form of systematic inquiry because it prioritizes reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice. Educators are able to simultaneously investigate an issue as they solve it, and the method is very iterative and flexible.

A cycle of inquiry is another name for action research . It is usually visualized in a spiral shape following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2024, January 12). What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/action-research/

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th edition). Routledge.

Naughton, G. M. (2001). Action research (1st edition). Routledge.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is an observational study | guide & examples, primary research | definition, types, & examples, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Neag School of Education

Educational Research Basics by Del Siegle

Action research.

An Introduction to Action Research Jeanne H. Purcell, Ph.D.

Your Options

- Review Related Literature

- Examine the Impact of an Experimental Treatment

- Monitor Change

- Identify Present Practices

- Describe Beliefs and Attitudes

Action Research Is…

- Action research is a three-step spiral process of (1) planning which involves fact-finding, (2) taking action, and (3) fact-finding about the results of the action. (Lewin, 1947)

- Action research is a process by which practitioners attempt to study their problems scientifically in order to guide, correct, and evaluate their decisions and action. (Corey, 1953).

- Action research in education is study conducted by colleagues in a school setting of the results of their activities to improve instruction. (Glickman, 1990)

- Action research is a fancy way of saying Let’s study what s happening at our school and decide how to make it a better place. (Calhoun,1994)

Conditions That Support Action Research

- A faculty where a majority of teachers wish to improve some aspect (s) of education in their school.

- Common agreement about how collective decisions will be made and implemented.

- A team that is willing to lead the initiative.

- Study groups that meet regularly.

- A basic knowledge of the action research cycle and the rationale for its use.

- Someone to provide technical assistance and/or support.

The Action Research Cycle

- Identify an area of interest/problem.

- Identify data to be collected, the format for the results, and a timeline.

- Collect and organize the data.

- Analyze and interpret the data.

- Decide upon the action to be taken.

- Evaluate the success of the action.

Collecting Data: Sources

Existing Sources

- Attendance at PTO meetings

- + and – parent communications

- Office referrals

- Special program enrollment

- Standardized scores

Inventive Sources

- Interviews with parents

- Library use, by grade, class

- Minutes of meetings

- Nature and amount of in-school assistance related to the innovation

- Number of books read

- Observation journals

- Record of peer observations

- Student journals

- Teacher journals

- Videotapes of students: whole class instruction

- Videotapes of students: Differentiated instruction

- Writing samples

Collecting Data: From Whom?

- From everyone when we are concerned about each student’s performance.

- From a sample when we need to increase our understanding while limiting our expenditure of time and energy; more in-depth interviews or observations may follow.

Collecting Data: How Often?

- At regular intervals

- At critical points

Collecting Data: Guidelines

- Use both existing and inventive data sources.

- Use multiple data sources.

- Collect data regularly.

- Seek help, if necessary.

Organizing Data

- Keep it simple.

- Disaggregate numbers from interviews and other qualitative types of data.

- Plan plenty of time to look over and organize the data.

- Seek technical assistance if needed.

Analyzing Data

- What important points do they data reveal?

- What patterns/trends do you note? What might be some possible explanations?

- Do the data vary by sources? Why might the variations exist?

- Are there any results that are different from what you expected? What might be some hypotheses to explain the difference (s)?

- What actions appear to be indicated?

Taking Action

- Do the data warrant action?

- What might se some short-term actions?

- What might be some long-term actions?

- How will we know if our actions have been effective?

- What benchmarks might we expect to see along the way to effectiveness ?

Action Plans

- Target date

- Responsibility

- Evidence of Effectiveness

Action Research Handout

Bibliography

Brubacher, J. W., Case, C. W., & Reagan, T. G. (1994). Becoming a reflective educator . Thousand Oaks: CA: Corwin Press.

Burnaford, G., Fischer, J., & Hobson, D. (1996). Teachers doing research . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Calhoun, Emily (1994). How to use action research in the self-renewing school . Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Corey, S. M. (1953). Action research to improve school practices . New York: Teachers College Press.

Glickman, C. D. (1990). Supervision of instruction: A developmental approach . Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Hubbard, R. S. & Power, B. M. (1993). The art of classroom inquiry . Portsmouth, NH: Heineman.

Lewin, K. (1947). Group decisions and social change. In Readings in social psychology . (Eds. T M. Newcomb and E. L. Hartley). New York: Henry Holt.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Participatory action research in education.

- Anne Galletta Anne Galletta Cleveland State University

- and María Elena Torre María Elena Torre Graduate Center, City University of New York

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.557

- Published online: 28 August 2019

Participatory action research (PAR) is an epistemological framework rooted in critiques of knowledge production made by feminist and critical race theory that challenge exclusive academic notions of what counts as knowledge. PAR legitimizes and prioritizes the expertise and perspectives that come from lived experience and situated knowledge, particularly among those that have been historically marginalized. In education research, a PAR approach typically centers the wisdom and experience of students (or school-age youth) and educators, positioning them as architects of research rather than objects of study. This form of participatory inquiry and collective action serves as a countercurrent in schools, where democratic inquiry and meaning making contradicts the top-down knowledge transmission practices bounded by prescribed curriculum and high-stakes standardized assessments. Like all scholars, those engaged in PAR contend with questions regarding standards of scientific practice and what counts as evidence even as they co-generate knowledge and solidarity with communities in which they may be members or allies that are outside the academy.

PAR projects frequently emerge from a critique of dehumanizing structural arrangements and alienating, often pathologizing, cultural discourses. These critiques spark a desire for research that questions these arrangements and discourses, documenting and engaging critical interpretive perspectives, all with the hope of producing findings that will create cracks and fissures in the status quo and provoke transformational change. PAR builds inquiry in the spaces between what is and what could be, with the assumption that dissonance and/or clashes of meaning with ruptures are generative in the possibility for reframing social problems and reconfiguring human relations. When discordance within the research collective, or between the collective and the outside world, is engaged rather than denied or smoothed over, new and different ways of seeing and being emerge. More than simply a method, critical PAR reflects a philosophical understanding of knowledge as socially produced through history and power, an epistemology that recognizes the liberatory impulse of critique and its potential for transformation. PAR projects privilege standpoints that have been traditionally excluded and excavate operations of power within the research in order to inform analytical lenses necessary to understanding dynamics within the issues and experiences being studied.

Examining the potential of PAR in education requires particular attention to the context of what children and youth encounter on a daily basis. Schools have been and continue to be spaces of struggle and contestation for students, in terms of learning and development, mental health and well-being, and physical safety. Federal policies have hollowed out protections for the most marginalized students, particularly youth of color; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth; and immigrant and undocumented youth. The rampant privatization of public education, narrowing of public governance, and the deceptive branding of corporate reform as “equity” is sobering. PAR in education troubles this very context, offering a research praxis of countervailing power, agitation, and generative ways of knowing, and being in relation. This encyclopedic entry details the ways in which participatory spaces bring people together, through inquiry, across a continuum of privilege and vulnerability to make meaning of the conditions under which we are living, with each other, for our collective liberation.

- participatory action research

- education reform

- participatory contact zones

- generative dissonance

Introduction

Participatory action research (PAR) is an epistemological framework that reconfigures ways of knowing and being in relation—it marks an ontological shift from conventional research practices within the academy. Rooted in critiques of knowledge production made by feminist and critical race theory, PAR challenges exclusive academic notions of expertise, legitimizing, and prioritizing the expertise and perspectives that come from lived experience and situated knowledge, particularly those that have been historically marginalized (Collins, 1998 ; Harding, 1991 ). In education research, a PAR approach typically centers the wisdom and experience of students (or school-age youth) and educators, positioning them as architects of research rather than objects of study (Torre & Fine, 2006 ). Youth and educators are invited as colleagues to design research programs, determine research questions, gather and make sense of relevant literatures/existing knowledge, decide useful methods, collect and analyze data, and create meaningful research products. PAR may draw from a qualitative research approach or it may include quantitative research within a mixed methods approach.

While PAR does not need the participation of the academy, it is often constructed as a collaboration between university-based researchers and youth and sometimes adults outside of the university who are concerned about injustice in a number of public spheres. Together, these research collectives of differently positioned members across institutional and social hierarchies of power—of youth, academics, and, sometimes, elders, educators, artists, lawyers, and policymakers, for example—create what María (Torre, 2009 ) has called “participatory contact zones.” Each member/co-researcher brings her/his/their own reservoir of experiential knowledge and differing angles of vision to the table, into a participatory inquiry space committed to using and infusing these differences throughout the research process. A deeply relational praxis, PAR understands the diverse range of standpoints, and the potential dissonance and/or clashes that come with them, as an important and generative contribution to the research. When discordance within the research collective, or between the collective and the outside world, is engaged rather than denied or smoothed over, new and different ways of seeing and being emerge. For these reasons, PAR engages power and difference as part of an ethical and methodological stance within research. 1

To lay the groundwork for a discussion of the complexities of carrying out PAR projects in and around educational spaces, we begin by establishing some of the contemporary tensions within public education. We then introduce a project with the hope of illustrating some core theoretical, methodological, and ethical commitments of a critical PAR praxis, paying particular attention to the relational and structural dimensions of PAR as well as generative possibilities opened by PAR’s embrace of discontinuities and dissonance. At the heart of what we hope readers will take away from this article is an understanding of participation in PAR as an inherently ethical commitment to redistribute power and legitimacy. This commitment is complexly woven throughout all steps of the research process. In education, like many institutions, decentering privilege and questioning power threatens existing structural arrangements and is often met with hostility by those historically in control. While these challenges tear at the institutional fabric of what has been , the conflicts generated by participation have the potential to create openings and “break with what is supposedly fixed and finished, objectively and independently real” (Greene, 1995 , p. 19) and thus reframe research questions, introduce alternative interpretations, and reposition relations of power toward what could be .

In the next section, we outline the theoretical genealogy of PAR and consider philosophical underpinnings of critical participatory methodologies.

Theoretical Genealogy of PAR

The origins of critical PAR developed in the disciplinary margins of social psychology, education, and sociology. Many of its roots can be traced to community settings and contexts where academics, organizers, and residents gathered to address community problems and political oppression (Fals-Borda, 1977 ; Lewin, 1948 ; Rahman, 1985 ; Wormser & Selltiz, 1951 ). Social psychologist Kurt Lewin, Claire Selltiz, and Margot Wormser stretched the methodologies of their discipline in the 1940s and early 1950s, adapting and developing a practice of action research for problem-solving on issues of racial and ethnic discrimination in the aftermath of World War II (Cherry & Borshuk, 1998 ; Torre & Fine, 2011 ). Lewin ( 1948 ) argued for an action research methodology maintaining a “constant intense tension,” where one “keep[s] both theory and reality fully within his field of vision” (p. 10). Fals-Borda and Rhaman ( 1991 ) describe the use of PAR in Bangladesh, Columbia, India, Nicaragua, Peru, Sri Lanka, the United States, and Zimbabwe where a number of academics in the late 1970s and early 1980s left positions within the university to engage in participatory community research. Some later returned to the academy, committed to the bumpy task of inserting PAR methodologies within rigid disciplinary views of science. This involved altering conventional conceptions of science, challenging the academy’s exclusive hold on “expertise,” and expanding notions of who can legitimately produce knowledge to those outside universities. This shift in power toward collective community efforts investigating human problems signified a recognition of the deep reservoirs of cultural knowledge and local expertise within communities confronting these problems. Further, the emphasis on the urgency of community inquiry in turn deemed action to be an integral part of knowledge production. The commitment to action insisted on a praxis research aimed at disrupting relations of oppression. Embracing Marx’s call to move from interpretation to transformation (Engels, 1886/1946 ), an epistemology emerged around the globe that braided knowledge production, struggles for justice, and participation of the people.

More Than a “Method”

Central to a critical praxis of PAR is a framework that reconfigures relational, structural, and cultural arrangements of power in order to collectively alter ways of thinking about conditions of lived experience. Embodying the spirit of Gramsci (Hoare & Smith, 1971/2000 ), it involves a research process in which social givens are upended, “common sense” is critiqued (p. 637), and the “spontaneous’ consent” by which we participate in everyday structures of oppression is surfaced and troubled (p. 145). More than simply a method, critical PAR reflects a philosophical understanding of knowledge as socially produced through history and power, an epistemology that recognizes the liberatory impulse of critique and its potential for transformation. Projects privilege standpoints that have been traditionally excluded and excavates operations of power within the research in order to inform analytical lenses necessary to understanding dynamics within the issues and experiences being studied. As Morrow and Torres ( 1995 ) note, the experience of privilege and exclusion, sometimes veiled, “is never fully secured, remains precarious, and must be continually negotiated” (p. 278), providing potential for counterhegemony and resistance. In this sense, a PAR approach is both a “rigorous search for knowledge” and what Fals-Borda called a “ vivencia ,” a “progressive evolution toward an overall, structural transformation of society and culture, a process that requires ever renewed commitment, an ethical stand, self-critique and persistence at all levels” (Rahman & Fals-Borda, 1991 , p. 29).

Critical collective participatory methodologies create ways to explore inconsistencies between the external reality of those marginalized by poverty and the consciousness through which the reality is understood. Paulo Freire’s work in Brazil in the 1950s before his incarceration powerfully illustrates the link between the struggle for emancipatory knowledge and the constraints of social reproductive forces in education. He argued for a pedagogical praxis that was “forged with , not for , the oppressed (whether individuals or peoples) in the incessant struggle to regain their humanity” (Freire, 1970/2016 , p. 48). For Freire, key to the struggle for liberation was a movement toward awareness. Within PAR, researchers committed to justice “must perceive the reality of oppression not as a closed world from which there is no exit, but as a limiting situation which they can transform” (p. 49). Freire critiqued education as typically reliant on cultural transmission of knowledge that is widely privileged and credentialized, which he referred to as the “banking theory and practice” which “fail[s] to acknowledge men and women as historical beings” (p. 84).

The work of Lewin, Wormser and Selltiz, Fals-Borda, Rahman, Freire, and others around the globe has continued to inform generations of PAR driven by emancipatory struggle (Zeller-Berkman, 2014 ). Challenging the idea that expertise exists solely within the academy or professions, community leaders of color in the urban United States, alongside interracial solidarity collectives and indigenous peoples from rural and urban communities, have brought their local knowledge and practices to the research table, along with a multiplicity of skills and understandings to new knowledge and alternatives to oppressive structural arrangements (Ayala et al., 2018 ; Cahill et al., 2017 ; Galletta, 2019 ; Smith, 2012 ; Torre et al., 2017 ).

We turn now to a discussion of PAR specifically within the realm of education with the hope of marking important ideas, tensions, and ethical considerations. Our discussion should not be understood as exhaustive since the body of participatory research in education is rich with variation. We should note that the context from which we write is primarily, though not exclusively, within the United States.

Historicizing the Context of Education

It feels impossible to begin a discussion of PAR in education without reflecting first on the ideological, epistemological, geopolitical, and racialized geographies within contemporary philosophical and political trends in PK–12 public education. What does it mean to engage students, teachers, and school communities in a transformative process of democratic inquiry and meaning-making when such communities have been placed in the straightjackets of high-stakes testing and neoliberal restructuring? A second important reflection must attend to the field of educational research itself and the ways the academy has historically privileged and valued particular ways of knowing over others. What then does it mean to engage in open-ended mixed method research in which untraditionally trained researchers determine questions, design methods, and analyze and interpret data? In the following section, we open each of these areas and encourage readers to think about the challenges and tensions these realities produce for a sincere engagement with PAR in education.

Philosophical and Political Trends in Public Education

Deeply constrained by the parameters of individual economic mobility and the neoliberal press for dominance within a global competitive market, the current context of education philosophically and politically is engaged in the transmission of knowledge through standardized curriculum and high-stakes testing. Furthermore, the obligation to facilitate the learning and well-being of children and youth stems from a narrow commitment to investment conditioned on the rate of return for the degree of resources invested. In the late 1980s and 1990s, as school districts were released from desegregation rulings, the move toward resegregation took hold, with increased isolation of poor and working-class students of color and immigrant students. In the mid-1990s and early 2000s, and again in 2015 , federal policy reconceptualized equity. The movement toward atomized standards and measures of achievement and quality in education through state testing, most evident in the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, shifted the equation from input to output equity (Rebell & Wolff, 2008 ) absent scrutiny on gaps in opportunity, capacity, and access to resources. The current moment in education could be described as being under the tyranny of “new managerialism” characterized by a drive for “evidence-based practice” (Davies, 2003 ) with substantial imposition of philanthropic directives and business interests tied to funding (Ball & Junemann, 2012 ; Giridharadas, 2018 ).

Given these political and policy trends, the landscape of public education is saturated in a discourse and materiality reflecting an audit culture of high-stakes standardized testing (Koretz, 2017 ) and corporate education reform (Au & Ferrare, 2015 ; Fabricant & Fine, 2012 ; Lipman, 2004 ). Educational reform in the United States is argued as opportunity through race- and class-neutral individualized school choices that has as its consequence the furthering of the racialization and economic isolation of children and youth in schools “branded” by particular curriculum and outreach to families (Cucchiara, 2013 ; Kimelberg, 2014 ; Lareau, 2014 ; Pattillo, Delale-O’Connor, & Butts, 2014 ; Posey-Maddox, 2014 ). Within education and the connective tissue of the health, legal protection, and criminal justice systems, there is ongoing dispossession of public assets and the accumulation of those assets by private entities (Fine & Ruglis, 2009 ; Harvey, 2004 ; Lipman, 2016 ).

As a result, in terms of learning and development, mental health and well-being, and physical safety, schools have been and continue to be spaces of struggle and contestation for students. This has been evidenced most recently by federal policies that have hollowed out protections for the most marginalized students, particularly youth of color; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth; and immigrant and undocumented youth. In 2018 , the U.S. Department of Education and Department of Justice withdrew support for legal guidance discouraging schools from suspending and expelling students (Lhamon & Gupta, 2014 ). The Department of Justice and Department of Education also withdrew the 2016 legal guidance that schools treat students consistent with their gender identity (Lhamon & Gupta, 2016 ). And, most recently in 2018 , a White House memo expressed the intention to deny the existence of transgender people. This withdrawal of federal policy support and recognition has double impact for LGBTQ students, who report disproportionately high levels of in-school and out-of-school suspensions (Kosciw, Greytak, Zongrone, Clark, & Truong, 2017 , p. 48). Piled on to these shifts away from protecting youth in schools are the recent attacks on young people migrating to the United States and immigrant youth with long-term residency.

These daily lived conditions shape the contours within which PAR unfolds and challenges, raising critical considerations for a research praxis that ignites and supports the full participation and direction from youth who are structurally dispossessed and speaking out within spaces of intersecting lines of resistance.

Privileging What Has Historically “Counted” as Knowledge and the Policing of Such Matters

In addition to conditions on the ground inside PK–12 education, the horizon for educational research has lost considerable capacity for imagining many ways of inquiring into, interpreting, and altering the conditions of human experience in public education. As feminist and critical theorist Patti Lather ( 2004 ) observes about the role of the National Research Council and its 2002 report, Scientific Research in Education : “In spite of its oft-repeated intentions of balance across multiple methods, objectivity is enshrined and prediction, explanation, and verification override description, interpretation, and discovery” (p. 762). With the legislation of the Every Student Succeeds Act, the articulation of criteria for quality research includes four tiers of research standards that define the degree to which educational research is rigorous and replicable. A Foucauldian act of surveillance and control, these tiers of research frame the standardization process, with each tier involving some form of experimental or correlational design, statistical analyses, or measures of significance. The justification for these standards is the assumption that a “high-quality research finding . . . is likely to improve student outcomes or other relevant outcomes” (Every Student Succeeds Act, 8101[21]).

Given this context, critical PAR is an inherently transgressive approach in its attention to power, its privileging of the lived experiences of the most marginalized, its use of problem posing and grounded participatory methodologies, and its commitments to produce knowledge useful for political activism and community mobilization against structures of exclusion and alienation (Cahill, Rios-Moore, & Threatts, 2008 ; Caraballo, Lozenski, Lyiscott, & Morrell, 2017 ; Drame & Irby, 2016 ; Guishard, 2009 ; jones, Stewart, Galletta, & Ayala, 2015 ; Otero & Cammerota, 2011 ; Torre et al., 2008 ; Tuck et al., 2008 ; Wright, 2015 ).

PAR in Education: Predictable Tensions

Some might argue that there is an elephant in the room when one is engaged with PAR projects that take place in schools. Not all participatory research in education is located within schools, but, when it is, predictable tensions often arise. While there are ongoing struggles to reimagine education, formal educational spaces can be alienating hierarchical places where relationships between youth and adults are rigid and not rooted in equality (Irizarry & Brown, 2014 ). Students are generally positioned as receivers of knowledge who are expected to follow directions; they are rarely included in decision-making about policies and cultural practices that shape their experiences, and they often face disciplinary outcomes if they do not do as they are told. In contrast, PAR spaces are built around methodologies that encourage open-ended inquiry, assume that knowledge is co-constructed, challenge conventional power relationships, and aim to disrupt and transform oppressive conditions.

As a result of these tensions, critical PAR projects—projects that consciously incorporate feminist, critical race, decolonial, and neo-Marxist frameworks—make strategic decisions about when and how to study issues in education from within schools and when to instead operate from outside, in community organizations, recreation centers, libraries, and the streets. However, as we discuss in more depth later, regardless of research settings issues of power exist and must be negotiated. When participatory methodologies are uncritically employed, they, like any methodology, can reproduce “the very forms of oppression that participatory approaches seek to disrupt” (Drame & Irby, 2016 , p. 3). All research is vulnerable to gendered and racialized social relations (among others) that appear so natural and inevitable that their toxicity is left undetected (Hall, 1993 ). Critical PAR addresses this by engaging in ongoing questions of privilege and vulnerability throughout the research process, reflecting the theory and history of the origins of PAR.

Participatory Methodologies in the Life of a PAR Project

We work as faculty in public universities, active in formal and informal educational settings, in both classrooms and communities, with a commitment to envisioning the academy as an inclusive public space for inquiry and social action. Anne collaborates with youth, educators, and community leaders in efforts to inquire about and take action toward more equitable relations and structural arrangements in education. María spends much of her time running the Public Science Project, which brings together intergenerational and interracial collectives of academics, organizers, advocates, artists, lawyers, and policymakers to engage participatory research in the interest of transforming unjust conditions. In the next section, we draw from moments within the life of a PAR project in Cleveland, Ohio, called Lives in Transition, to illustrate a set of theoretical, methodological, and ethical characteristics and considerations when engaging PAR in education.

Lives in Transition: Constructing Knowledge and Formulating Critique on the Meaning of School Closure

As was the case in Chicago, Denver, New York City, Philadelphia, and many other urban school districts across the United States, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD) responded to federal accountability policy and state and local school reform initiatives by closing schools in some of the poorest neighborhoods on the city’s east side, where many African American families live. The consequences of these decisions impacted the lives of youth, families, and communities for whom these schools were a part. A collective of approximately 10 high school youth, several teachers, and graduate students and faculty from Cleveland State University came together to document the historical moment and understand the meaning of these school closures for youth and interrogate the discourse of “transformation” by the district. The research collective met regularly from 2010 through 2011 . The origins of this project reflect a common characteristic of PAR beginnings, as noted in our first core dimension of PAR.

Organic and Collective Beginnings

The origins of PAR projects are often organic and collective in nature, responses to realities of groups encountering unfair or unjust historical moments. In the case of the project discussed here, the announcement that the district was going to close schools that had not met state “standards of achievement,” among other measures, interrupted the life of students in Edison High School, a school where Anne and visual artist and PAR researcher vanessa jones were working on a storytelling project. 2 The focus of their project with students in the school at that time was the nature of transitions in the lives of young people. In the midst of narrating significant turning points of their lives through spoken word, art, and music, the participating students encountered a new life transition—as the closure of their high school was impossible to ignore.

Anne, vanessa, and their youth co-researchers faced a critical situation. The storytelling project had created a space where close relationships developed amid both a nurturing and hostile school climate. On the one hand, there were classrooms where teachers understood the brilliance and struggles of their students; on the other, students had to enter the school each day through “weapon detectors” and were subjected to the use of “lockdowns” to empty the hallways. Students facing the closing of their school were filled with uncertainty, anger, and apprehension—affect and reactions that felt in stark contrast to the reform narratives being used by the local district and the federal education policy to justify the closings through the argument that school closure was a “necessary intervention” to save students from “failing” schools. The sharp difference between the “reform” discourse and student experiences signaled the need for inquiry. Ethically, it pointed to a glaring absence. Where was the expertise—the voices, experiences, and ideas—of youth and teachers attending and working inside the schools targeted for closure?

In the year that followed, students displaced by school closures and those in receiving schools were forced to navigate new spaces and relationships. Anne and vanessa decided to collaborate with teachers and graduate students to offer a space for critical PAR in an after-school program in two of the high schools receiving students displaced by school closure. In keeping with the theme of transitions, the project was named Lives in Transition, or LiT.

Recognizing Expertise Beyond the Academy

PAR is guided by experiential knowledge and recognizes the legitimacy of those outside the academy to problem-pose and conduct research about issues impacting their lives. The expertise youth brought to the LiT project was essential to documenting the experience of school closure as they were living it in the present. They wrote poetry, drew maps of their neighborhoods and bus routes, and filmed the processes of the research collective’s engagement in forms of problem-posing. Anne and vanessa brought data sources providing a broader context to the meetings, such as district reports on the criteria used for closures, newspaper clippings on how the district justified its closure decisions, documents on district and state educational policies on school transportation and the use of closed school facilities, as well as historical accounts related to neighborhoods affected by the closures. They invited guests to meetings, who brought specific information needed to complete the inquiry. Critical PAR often draws on the expertise of intergenerational collectives, wherein differentially positioned members carry varied (though sometimes overlapping) funds of knowledge. The validity of the research is strengthened by this breadth of expertise—in this case, the youth knowledge about their communities and schools as well as the adult knowledge of the law, history, or data from particular fields.

In this manner, being on the “inside” of an issue or experience brings an angle of vision likely to afford understanding of the nuances and complexity of the problem being studied. Those positioned outside the community or the study focus may raise questions that reveal gaps in understanding or investment in outsider perspectives. For example, vanessa proposed involving students in the PAR project to the administration at one of the schools receiving students displaced by school closure. The school administration declined extending an invitation to their students to participate, noting that students’ participation in PAR on the experience of school closure might “bring the pain up again” (jones, Stewart, Galletta, & Ayala, 2015 ). While the production of knowledge of those closest to the problem studied offers potential for constructing new knowledge, as indicated here it also may pose a threat to maintaining ways of knowing and being in relation that support the status quo. Alternative angles of vision offered by the youth experiencing school closure may have produced knowledge potentially disruptive to the established logic of the district’s educational policies. In this example, the transgressive nature of PAR is evident, as is the centering of the experience of youth within the construction of knowledge and the repositioning of relationships.

Discontinuities as Potential Reframing Analysis and Repositioning Relationships

PAR is attentive to discontinuities in ways of seeing a problem and the power relations at work within conflicting frames for analyzing a problem. While dissonance and disagreement can be productive to research, they are not always easy. We experienced a moment of conflict for the LiT project where youth researchers were speaking about the varying identities students possessed, which differed depending on whether they were displaced by school closure and sent to a receiving school or were in the receiving school, impacted by the presence of new students transferring in from closed schools. The conversation took place at a research meeting at Granite Hill, a high school that received students from Edison High after Edison was closed. Students and teachers were each arguing from standpoints that held deep knowledge of the experience of dislocation but with different perspectives. The conflict surfaced the reality that students from closed high schools held strong ties to their old schools, and this was reflected in their reluctance to associate themselves with the new school to which they had been transferred. It also underscored for the research collective the importance of place, socially, historically, and geographically for students and school communities, as the school closings involved relocating students across geographic and community boundaries to new schools that often had long-standing rivalries and other competitive relationships with their old (now closed) schools.

Three teachers participated in the LiT PAR collective the year after a number of schools were closed. The teachers, all African American, were recognized as strong student advocates with shared cultural connections with the youth researchers. At the same time each represented different vantage points and varying degrees of structural constraints (Kohfeldt, Chhun, Grace, & Langhout, 2011 ; Ozer, Ritterman, & Wanis, 2010 ). Students knew Ms. Drew and Ms. Turney to be teachers who responded quickly to student challenges, provided rides home when bus fare was unavailable, and supported students when families encountered health crises. The third teacher, Sergeant Goodman, directed the JROTC program. Anne and vanessa had met him through two students who joined JROTC when they arrived at Granite Hill High School, after being transferred from their closed school. He asked to join the project, and though Anne and vanessa shared a broader critique of the presence of JROTC inside poor and working-class urban and rural schools but absent from wealthier suburban schools, they recognized his relationships with the students and his desire to support the project. His presence added to diverse perspectives among the adults who were insiders to the school. vanessa was also an “insider” in many ways as her son attended Cleveland schools, and she shared common experiences of attending underresourced schools serving poor and working-class communities of color. As a member of the research collective she drew organically from these experiences as a student longing for greater “communication, expression, freedom, and forming social connections” in education (jones, 2012 , p. 193). Anne’s race and social class background positioned her at times as an “outsider,” even as her regular presence in classrooms and community meeting spaces offered meaningful relationships with students and teachers and provided exposure to intimate knowledge about what was happening inside the schools.

In this participatory contact zone of sameness and difference—within the research collective—LiT members inquired and engaged multiple positionalities, sparking lenses of analysis used in meaning-making, contestation, humor, and reflection throughout the research process. A student researcher who was displaced spoke about his feelings of loss and defended those who resisted, even resented, assimilation into their receiving school, Granite Hill High. Other youth researchers saw this as deeply problematic and even used the moment to lift the benefits of being a student at Granite Hill, boasting of its athletic prowess and superiority. In what first appeared to be playfulness within the group, there was evident a rub produced by the strong shared frustration over the policy of school closure that, while impacting each of them differently, was enforced on all of them without any control or authorizing on their part.

A youth researcher who had been at Granite Hill for several years responded critically toward displaced students who stayed loyal to their closed school. Frustration hung from the words shared, particularly by one of the teachers. In a discussion punctuated with references to teachers who did and did not help students learn, and resources the school did and did not possess, the statements became personal. Ms. Drew spoke in a raised, emotional tone in her response to a youth researcher’s observation that displaced students retained their former school’s affiliation:

What he’s saying is that, most people who consider themselves from Edison High, they were invested in their school. But if you . . . went to Edison, and you walked the hall all day then, and then your school closed, you have no right to complain. You didn’t go to class and that’s why the numbers went down , because you didn’t go to your class and that’s why Edison had to close. Because if you would have been in class then they would’ve had the numbers they needed.

This biting critique by a teacher, uncharacteristic of her reputation as a student advocate, revealed the abrasive and frequent presence of high-stakes measures as a reference point in the lives of teachers and students. These measures influenced school rankings and led to school closure, dressed up as school reform. Ms. Drew called on the assumptions of a policy context where “numbers” drove decisions that were decontextualized from the lives of youth, their families, and educators. As Ms. Drew continued she revealed her biography of struggling with displacement as a teacher. She noted her affection for her former school and its students. Along with students and other teachers, Ms. Drew had been transferred from Kensington High to Granite Hill just that year. The tension created by her passionate comments forced the research collective to acknowledge that the threat of school closure bleeds into the everyday life of all schools in the district including “receiving schools.”

Ms. Drew: I came from Kensington. I love Kensington . . . I’ve seen plenty of kids . . . that graduated . . . that’s my school. vanessa: So that was a part of the story— Sergeant Goodman: Their pain could be your pain. As easy as Edison High closed, Granite Hill could be next. Ms. Drew: That’s right. Sergeant Goodman: And truth be told Granite Hill is on that list.

We see in this strained moment the created space for problem-posing, in the Freirian sense, as LiT members actively engaged in working out together and naming their “reality” as students and teachers, reflecting on differing and similar experiences of youth and of teachers. In this way, the LiT members came closer to understanding themselves to be “in a situation,” as Freire might say, coming closer to “the very condition of existence” (Freire, 1970/2016 , p. 109). The clash of ideas and interpretations created deeply pedagogic moments relationally and conceptually. Through their own enactments, the very dynamics of what they were studying surfaced. At its best, PAR produces critically pedagogical spaces where tensions and dissonance spark learning for everyone in the collective , not just the youth or the adults, and new possibilities in knowing and being in relation can be imagined.

Situating Lived Experiences of Youth Within Broader Structural Conditions

Within PAR, critical inquiry and ethical praxis situates lived experiences of youth within broader structural conditions. What happens within the PAR collective often speaks to what is happening in the broader context, influencing what students and educators are experiencing within schools. Here LiT members were also engaged in a form of what Drame and Irby ( 2016 ) refer to as interpersonal reflexivity, which interrogates positionalities and the nature of relationships within and beyond us (see also Chiu, 2006 ; Nicholls, 2009 ). Collectively there is a role for reflexivity within critical PAR where as a group we might pause and examine what is happening within the PAR collective to understand how it may be influencing the conceptualization of a project, data collection, analysis of the data, and/or reporting back results. Interpersonal reflexivity involves deliberate attention to the contextual layers of analysis and relations of power operating within the research. As Cammarota and Fine ( 2008 ) write, knowledge gained from research “should be critical in nature, meaning that findings and insights derived from analyses should point to historic and contemporary moves of power and toward progressive changes improving social conditions within the situation studied” (p. 6).

In this manner, ethical considerations impacted analytical practice and reporting back strategies. It meant attending to a broader context within which LiT youth researchers, educators, and university faculty worked together. At the state level, legislation in 2012 had altered school funding policies to allow CMSD to share a portion of local funding with charter schools the district deemed high performing. State per-pupil funding followed students out of district schools and into charter schools as a result of provisions of No Child Left Behind, as one of several consequences for districts with underperforming schools. Also, federal funds flowed to states through legislation specifically supporting the establishment of charter schools. Schools faced closure, followed by the opening up of educational facilities once publicly owned to privatized entities through charter school start-ups and new theme-based district schools in partnership with industry and nonprofit organizations.

These broader structural conditions and their historical significance provided the interpretive material to document the “webs of power that connect institutional and individual lives to larger social formations” (Weis & Fine, 2004 , p. xxi). These considerations were evident in the creative product as LiT prepared to communicate findings to the public. In a performative sharing of pain associated with school closure and the power in reframing this policy as unjust, vanessa jones and Eric Schilling integrated the poetry, images, and narratives of LiT members and produced a film, Lives in Transition: Eviction Notice (jones & Schilling, 2011 ). The film reflected the creative work of the youth in naming their reality and using creative arts to convey the findings from the PAR project to “retrieve and correct official or elitist history and reinterpret it according to class interests” (Fals-Borda, 2001 , p. 30). The metaphor of eviction reflected the realities of the lives of the youth, experienced in residential mobility. Now, as a result of state and local intervention through school accountability policies, students experienced the imposition of a decision with profound relational and material consequences. This counterstory was conveyed in the film.

In the spirit of questioning, a core value and epistemic activity in critical interpretive perspectives, we can see that the beginnings of PAR projects frequently emerge from a critique of dehumanizing structural arrangements and alienating cultural discourse. Those for whom the critique is most profoundly embodied play a central role in the participatory inquiry and action, displacing notions of expertise common within the academy. The tasks of engaging in dialogue and problem-posing often lead to discontinuities in understandings as situated standpoints produce differences in ways of being and knowing. In the next section, we discuss an additional dimension of PAR as we consider ethical commitments within collective production of knowledge.

Layering Collective Analyses

Participatory analysis in PAR involves a layering of collective analyses with critical theory and ethical praxis. The iterative process creates openings for deeper understandings. As the research process unfolds and analyses become more nuanced, new inquiries can organically emerge. Often new questions are prompted by shifting sociopolitical contexts—perhaps evolutions of issues that sparked the research in the first place. This in turn can inspire additional methods, data, and/or analyses.

After the first group of LiT youth researchers left the project to pursue jobs, family responsibilities, and postsecondary education, another group of 25 young people joined the project and extended the work of the earliest LiT collective. This second phase of the LiT project decided to build on earlier analyses with a survey of youth experiences of educational transitions imposed on students, their families, and teachers, without their deliberation. The survey was administered to 258 students across the seven schools that the 25 youth researchers attended, some of which were neighborhood comprehensive high schools while others were recently established theme-based district schools.

The decision to create the survey reflected a continued desire to flesh out and fill in the absent student expertise in the conversation about school reform. Collecting more data on school closure, students changing schools, student–teacher relationships, and transportation challenges from the perspective of the students in the district promised a more nuanced analysis. Notably, it represented an ethical praxis within PAR to center the knowledge and rights of those most impacted by the conditions being studied. The initial LiT research revealed that teachers and students were invested in their teaching and learning and had often built strong communities in their “failed” schools, and the data called the dominant discourse on “failing schools” into question. In this way the emphasis within PAR to engage iterative inquiry processes grounded in lived experiences, layered with critical sociopolitical analyses of contemporary and historical policy and practice, enabled the LiT collective to avoid slipping into reproducing prevalent analyses that stereotyped and dismissed the experience of students and teachers. Drawing on the lessons of DuBois and Freire to resist these seductive and simplistic individual-level analyses that obscure the responsibility of broader sociopolitical power reflects an ethical stance within PAR. Ontologically, this interpretive stance opens space for understanding the realities encountered by students in relation to the conditions under which they are forced to live.

In reviewing the survey data, the LiT research collective engaged in an analytical conversation with data from across the life of the first and second phase of the LiT project, alongside analyses of local history, educational policy, and current structural conditions. For example, survey data showed that 59% of the ninth-grade students said students and teachers did not get along very well. This large percentage signaled a serious break in relationships central to meaningful learning and social and emotional safety among students and teachers. It concerned members of LiT in that it echoed dominant narratives of teacher indifference and student recalcitrance. However, student data also indicated teacher qualities that the collective agreed were important, such as teachers encouraging critical thinking and challenging their students to work hard. Some of the open-ended data on the impact of school closure indicated grief and anger over the severing of productive student relationships with teachers.

How would this apparent contradiction in the data be represented in the reporting back of research findings? This presented not only a question about interpretive validity but also a question about ethical responsibility. As noted by Guishard et al. ( 2018 ), “Knowing and knowledge production inherently come with an epistemological responsibility that is simultaneously, an ethical responsibility” (para. 40). Guishard et al. underscore the ethics inherent in data interpretation and with Thomas Teo call upon researchers to be aware of the responsibility researchers have to interrogate their frames of analysis in order to avoid the reproduction of harm through what Teo ( 2011 ) refers to as epistemological violence directed at communities that have been and may be further marginalized when “equally plausible interpretations of the data are available” and not accessed (p. 247). What interpretation offered validity from a critical and multilayered analysis?

After some discussion of what contributes to teachers and students not getting along, Anne and her university colleagues drew from transcripts of PAR meetings in the first phase of LiT that spoke of strained relationships among students and between students and teachers as schools closed and schools in other neighborhoods received displaced students. Holding together the different forms of data as well as the social and political history in the district allowed the collective to develop a more contextualized and complicated interpretation of survey data.

For example, when the youth researchers dug deeper into the data on students attending multiple schools, they found most of the students responding to the survey reported changing schools at some point in their K–8 trajectory, with 35% reporting having changed schools five to nine times and 6% indicating that school changes occurred more than nine times (Steggert & Galletta, 2018 ). These staggering numbers felt like an important contradiction within a district that uses a K–8 school structure in order to maintain continuity across the elementary and middle school grades. The data points sparked a shift in analysis within the research collective, wherein the phenomenon of “teachers and students not getting along” was no longer easily understood as teacher or student obstinance or disrespect.

Instead a more nuanced interpretation emerged that considered forced relocation; alienation; interrupted student–teacher relations; and severed family and community roots, traditions, and practices. This produced a key theme in the LiT findings: school closure and frequent changing of schools was associated with challenges for youth socially and academically. Situated analytically in relation to the history of school reform initiatives carried out in the district, often exacerbating students’ access to educational opportunity, the data supported LiT’s critique of reform initiatives that failed to actually improve their schools, particularly those serving the most economically stressed neighborhoods. Youth researchers prepared creative products such as video, poetry, and music to report back findings specific to their schools, presenting their findings in classrooms and engaging students who participated in the survey in further problem-posing through these discussions (Giraldo-Garcia & Galletta, 2015 ).

The inclusion of sociopolitical analysis is a key element of a critical PAR praxis, one that involves illuminating the connections between “personal, micro-level experiences of sociopolitical inequities to larger macro-level sociological forces” (Wright, 2015 , p. 196). Wright links this form of analysis to Freire’s concept of critical consciousness, of grasping that which was “not perceived in its deeper implications (if indeed it was perceived at all)” (Freire, 1970/2016 , p. 83). Cahill, Rios-Moore, and Threatts ( 2008 ) engage similar analyses by posing three levels of interpretation, each intertwined with forms of social action: (a) involving looking “closely,” questioning, and examining how lived experience is influenced by broader economic and ideological processes; (b) seeing oneself and one’s community as connected to often unexamined histories; and (c) envisioning with others what could be possible as alternatives to the current struggles (pp. 90–92). We next examine what happened as the research collective engaged individuals and groups in positions of political power and influence when youth researchers and adult allies reported back their research findings.

Ethical Praxis and Epistemological Commitments

PAR opens up spaces within collectives of individuals differently positioned and engages standpoints of power and vulnerability. In doing so, dissonance and conflict arise, signaling moments of discontinuity. These moments offer potential for reframing existing knowledge and relationships. They also may result in the shutting down of transformative possibilities.

This is evident in the experience in which members of LiT reported back survey results. For example, LiT met with the leadership of the School Reform Partnership within Cleveland, the public-private partnership charged by the state with overseeing the city-wide school reform plan, to inform members of its board of the results of the survey. The School Reform Partnership involved elite membership of the city and county business leadership, influential private foundations, a charter organization supported by wealthy donors, higher education leadership, and local religious, community, and parent representatives.

Youth researchers Dana and Marcus arrived with Anne at the building that housed a major city foundation, where the School Reform Partnership also shared office space, described by Marcus as “really corporate-like.” When greeted by the director of this organization, it became clear the LiT reporting back session would take place with this individual and two staff, not the entire board of directors.

Marcus, Dana, and Anne shared the survey findings on the issue of school transportation, relationships between students, student–teacher relationships, frequency of students’ changing schools, and school closure. The clash of perspectives and vast differentials of power produced a stark clarity about how the district’s reform policy did not take the grounded experiences of students and teachers into account. It provided further evidence of one of the early themes of the first phase of the LiT research, that the reforms “were happening to us” without any form of participation along the way. Anne’s notes taken immediately after the meeting capture some of the exchange:

At one point Marcus spoke about what it was like to be at Granite Hill High School, designated by the district as an “investment” school. He talked about seeing his teachers face job insecurity in the school reform policy that required teachers to be interviewed for positions they had held previously, some for a long time. He noted, “students didn’t know if their teachers would be there” the following year . . . The Director of the School Reform Partnership seemed caught off guard by Marcus’ statement, his expression of concern for his teachers, and his affection toward his school. She commented that she hadn’t seen the reform strategies in the same way. Wouldn’t a student at Granite Hill express dissatisfaction with their school [given how poorly the school was performing]? There appeared to be some disjuncture evident to her at that moment, some gap between Marcus’ critique of the reform plan and her logic that “investment schools” were a way to remedy “failing schools.” She said something about not realizing students might love their schools even when their schools “failed” them.

The disjuncture at this moment within the meeting revealed a clear discontinuity of standpoints, commitments, and relations of power. At the same time, it offered the potential for producing new understandings. However, the potential opening apparent in this instance was not sustained or engaged. There was no opportunity to explore it further and produce new understandings and possibly reconfigure relationships or reframe the problems associated with underperforming schools in high-poverty neighborhoods. School closure and replacement, a possibility for Marcus’s school, was referred to as “inevitable” more than once by the director of the School Reform Partnership in talking with the LiT members. This reconnected to a moment three years earlier in the first phase of the LiT project when it was acknowledged that Granite Hill High School was “on the list.” This reference to a set of policy enactments that hung over students and teachers, something out of their control, was noted in a debriefing following the meeting of LiT with the partnership director. The following is an excerpt from the debriefing:

Anne: What point do you think engaged them the most? Marcus: Probably between transportation and school closings, school closings came up a lot. Dana: Yeah. Marcus: To the point that they’re unavoidable, or well, not unavoidable—they’re pretty much gonna happen at some point. Dana: Inevitable. Marcus: Yeah. Dana: Yeah and they kinda expressed that it's not necessarily all within their power if schools are closing but they agreed we need to make other aspects of students’ transition easier.

The naturalizing of the district’s reform strategy of school closure was so threaded through the conversation between the partnership leadership and the LiT members present that it appeared normative. This is evident in Marcus’s and Dana’s replication of the language of inevitability. Equally disturbing is the durability of statements repeated as real by Dana and Marcus when they reflected the director’s skirting of authority in the partnership’s involvement with school closures. In a setting where youth voice was presumably “heard,” the solution offered by the director during the meeting was to ease the transition for students but not end the policy of school closure. As noted by Anderson ( 2017 ), “In schools and districts, spaces for PAR open and close with frequency, making them risky and difficult to sustain when they challenge ‘NPM [new public management]’” (p. 440). The space of dissonance with its potential for transformation was cut short.

In the LiT project, this was evident in the discontinuity that surfaced, however momentary, in the meeting between LiT members and the School Reform Partnership director. Opening space for altering existing ways of knowing and being in relation, for interpretive ambiguity, and for relational dissonance creates cracks and fissures in the status quo from which transformational change might emerge. This level of change can feel impossible at times, for as Freire ( 2016 ) quotes from an unpublished work of José Luiz Fiori, “the structure of domination is maintained by its own mechanical and unconscious functionality” (p. 51, n 6). In the LiT project this dominant resistance was evidenced by the director’s ultimate dismissive statement of school closure as “inevitable.” Her comment, and the dissonance it created, provoked the LiT collective to spend time thinking about their own goals for their research, the ethics of representation, how the data they collected might be used for and against communities to which they felt responsible, which audiences were most important to them, and how they might best be engaged.

Engaging Action

In the iterative movement between inquiry and action throughout the life of a PAR project, the “action” of problem-posing takes as many forms—a reflection of the many different theories of change held by individual researchers and/or research collectives (Tuck & Yang, 2013 ). Typical understandings of action may involve engaging communities of interest in the findings of a PAR project or carrying out strategies responsive to the research findings, such as a plan to address issues uncovered through the research. Many PAR projects also recognize the transformative experiences of members of the research collective as actions (Zeller-Berkman, 2007 ). But actions can also occur or engage those who are “insiders to the problem” who were not involved in the PAR project, as well as press those not directly impacted but who are in positions of power as it relates to the research findings.