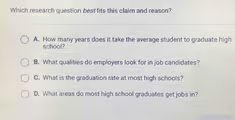

Which research question best fits this claim and reason? A. How many years does it take the average student to graduate high school? B. What qualities do employers look for in job candidates? C. What is the graduation rate at most high schools? D. What areas do most high school graduates get jobs in?

Gauth ai solution, gauth ai pro.

B. What qualities do employers look for in job candidates?

Explanation

The claim provided focuses on higher education and the factors influencing college admissions and graduation rates. Therefore, the research question that best fits this claim is: B. What qualities do employers look for in job candidates? This question is the most relevant as it pertains to the skills and attributes that high school graduates need to possess to be successful in the job market after completing their education