- Search Search

How to Write a Paper on a Biblical or Theological Topic

Writing research papers is an excellent way to learn because it trains you to gather information, interpret it, and persuasively present an informed opinion. The process teaches you a great deal, but it also equips you to contribute to ongoing discussions on a given topic.

Here’s the basic process of writing a research paper on a biblical or theological topic, either for a class or for your own personal research. Start at the top, or skip to what topic interests you most.

- Pick a topic

- Research your topic

- Construct an outline

- Draft your paper

- Revise and refine

Pick a Topic

Choosing the topic you want to research is often easier said than done. But perhaps the best advice to get the ball rolling is to narrow your scope. When your topic is too broad, you’ll likely find too much information (much of it unhelpful). But when your topic is appropriately focused, you can hone in on the information you need to gather and get down to the business of interpreting it.

For example, choosing to write a paper on the topic of sanctification is too broad to be helpful. But if you narrow your focus to a specific question about sanctification (for example: How do spiritual disciplines contribute to our sanctification?), you’ll find better direction for your research.

Remember, you don’t have to be an expert on the question you want to find an answer to—that’s what the research process will accomplish. You should, however, have an interest in the question and in finding an answer (or several!) to it.

For more on the process of researching and writing a paper, check out these resources:

- The Craft of Research – particularly chapter 3

- Writing & Research: A Guide for Theological Students by Kevin Gary Smith

- Logos Academic Blog: Work with Librarians to Help Students Write Better Papers

Logos Theological Topic Workflow

The Theological Topic Study Workflow in Logos guides you through the steps of studying a theological topic. It taps into the Lexham Survey of Theology and the built-in Theology Guide to give you the topic’s broader context, basic concepts, and issues associated with the topic. Review the biblical support and go deeper in your theological study by reading relevant sections from systematic theologies.

Research Your Topic

With your topic selected, it’s time to find the resources you’re going to use and dig into them. You may find that one resource offers the best discussion of your topic, but you can’t stop there! Researching well means considering opinions that differ from each other (and probably from your own). It’s in the conversation that emerges from engaging with multiple perspectives on a topic that real insight and understanding emerge.

Start the research phase by reviewing literature and building your bibliography, then consult standard sources and peer-reviewed journals.

1. Conduct a literature review and build your bibliography

The process of conducting a literature review and building a bibliography is an iterative process. It’s not a one-time step but a step you’ll return to repeatedly as you move through your research.

Essentially, in this step, you’re discovering what resources exist and cataloging them. As you begin to read the resources you discover, you’ll likely find references to other works that you’ll then want to read.

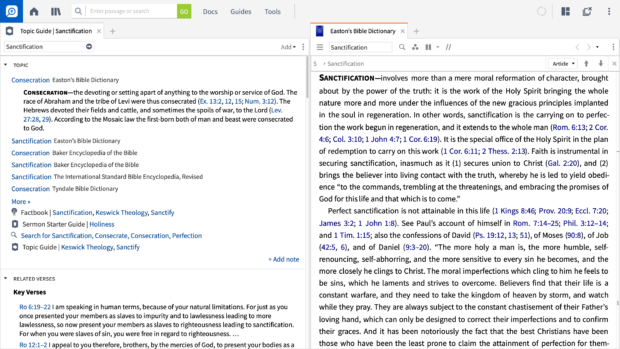

Logos Topic Guide

The Topic Guide gathers information from your library about a topic or concept. Using the Logos Controlled Vocabulary dataset , the guide finds topics in your Bible dictionaries and other resources that correspond to the key term you enter.

2. Consult standard sources

Encyclopedias, commentaries, theological dictionaries, concordances, and other theological reference tools contain useful information that will orient you to the topic you’ve selected and its context, but their biggest help to you at this stage will in their bibliographies. Be sure to check the cross-references often.

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, rev. ed. by E. A. Livingstone and F. L. Cross

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, since its first appearance in 1957, has established itself as the indispensable one-volume reference work on all aspects of the Christian Church. This Revised Edition, published in 2005, builds on the unrivaled reputation of the previous editions. Revised and updated, it reflects changes in academic opinion and Church organization.

Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity (3 vols.) by Angelo Di Berardino

The Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity covers eight centuries of the Christian church and comprises 3,220 entries by a team of 266 scholars from 26 countries representing a variety of Christian traditions. It draws upon such fields as archaeology, art and architecture, biography, cultural studies, ecclesiology, geography, history, philosophy, and theology.

Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (TDNT) (10 vols.) by Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich, Geoffrey William Bromiley

This monumental reference work, complete in ten volumes, is the authorized and unabridged translation of the famous Theologisches Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament, known commonly as “Kittel” and considered by many scholars to be the best New Testament dictionary ever compiled.

3. Consult peer-reviewed journals

Even if you’re writing on a single text (like John 15:1–8 or Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite’s The Divine Names), you need to see what your contemporaries have to say about it to situate your research in its context. This means consulting peer-reviewed journals. As you read, you’ll discover where scholars agree and disagree and how the study of that topic has advanced over time.

Journal of Hebrew Scriptures (11 vols.)

The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures is an academic, peer-reviewed journal devoted to the study of the Hebrew Bible, and provides a forum for critical scholarly exchange. You’ll find hundreds of articles from top Hebrew scholars on trends in Hebrew and Old Testament scholarship, including historical, literary, textual, and interpretive topics.

Construct an Outline

This step is incredibly important, but it’s often overlooked. Start by refining your topic based on your research, then arrange your notes and research materials into a clear outline that will guide you toward a convincing and coherent argument.

See chapters 8 and 9 of The Craft of Research for more guidance on constructing your outline.

Draft Your Paper

You are now ready to draft your paper. Your initial focus is to expand your outline into paragraph form as straightforwardly as possible. While your outline will be essential as you draft, you don’t have to stick to it absolutely. You may discover as you write that a different structure or organization will better advance your argument. While you’re at it, add relevant quotations from your research to clarify your points or support your arguments.

Revise and Refine

Notice the word “draft” in the previous step. That word is intentionally selected because, arguably, the most important part of the writing process is in your revisions. Drafting gets the ball rolling, but revising is where you refine and revise your previous drafts, ensuring your argument is clear and forceful.

Before you send your final paper, you’ll want to make sure you’re writing clearly and using the right style. If you are in school, follow the rules of your academic handbook. If not, adopt a common style guide like APA, Turabian, or the SBL Handbook of Style , and consult online guides like EasyBib or the Chicago Manual of Style for help. You can also find helpful writing advice in The Elements of Style .

If there are multiple paragraphs, just add another paragraph tag. If you need more padding, use an additional text block section as you see below.

While this structure is helpful, you may find that some variation of it works better for you. Go with what works because, at the end of the day, a thoroughly researched and well-written paper is what you’re after.

See how Logos can power research and aid you in the writing process.

Logos Staff

Logos is the largest developer of tools that empower Christians to go deeper in the Bible.

Related articles

Saved through Baptism: A Typology of Immersion Starting with the Flood

Seeing Christ in Job: An Exercise in Typological Reading

How Old Testament Typology Reveals Shadows of Salvation

Typology’s Logic: Chekov’s Gun & Bible Interpretation

Your email address has been added

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

Essays in Analytic Theology: Volume 1

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This book is the first of two volumes collecting together the most substantial work in analytic theology that I have done between 2003 and 2018. The essays in this volume focus on the nature of God, whereas the essays in the companion volume focus on humanity and the human condition. The essays in the first part of this volume deal with issues in the philosophy of theology having to do with discourse about God and the authority of scripture; the essays in the second part focus on divine attributes; and the essays in the third part discuss the doctrine of the trinity and related issues. The book includes one new essay, another essay that was previously published only in German translation, and new postscripts to two of the essays.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 2 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 8 |

| October 2022 | 11 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 3 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 5 |

| November 2022 | 4 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 4 |

| December 2022 | 4 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 7 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 4 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 1 |

| January 2023 | 8 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 5 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 1 |

| January 2023 | 5 |

| January 2023 | 8 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 3 |

| February 2023 | 3 |

| February 2023 | 9 |

| February 2023 | 3 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 2 |

| March 2023 | 2 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 2 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| April 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 3 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 4 |

| May 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 6 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| July 2023 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 4 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 6 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 9 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 4 |

| December 2023 | 6 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 8 |

| January 2024 | 7 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 5 |

| January 2024 | 5 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 3 |

| March 2024 | 3 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 5 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| May 2024 | 2 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 9 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 5 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| May 2024 | 4 |

| May 2024 | 9 |

| May 2024 | 7 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 9 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 1 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 11 |

| June 2024 | 1 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 1 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 1 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 1 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

Sample Student Theses

Global education.

- Global Jackson Orlando Charlotte Washington D.C. Atlanta Houston Dallas Memphis --> New York City Global

- Campus Home

Below are downloads (PDF format) of the M.A. (Religion) theses of some of our graduates to date.

Note: Certain requirements for current thesis students have changed since earlier theses were completed.

| Gregory Cline | 2020 | |

| Hikari Ishido | 2020 | |

| Jeffrey Johnson | 2020 | |

| Elizabeth Krulick | 2020 | |

| Peter Vaughn | 2020 | |

| Jason Burns | 2019 | |

| Jonathan Herr | 2019 | |

| David Lange | 2019 | |

| Steven Neighbors | 2019 | |

| Nancy Nolan | 2019 | |

| Kevin D. Pagan | 2019 | |

| Ronald A. Cieslak | 2019 | |

| Scott Davis | 2018 | |

| R. Shane Hartley | 2018 | |

| Chadwick Haygood | 2018 | |

| Brian Mesimer | 2018 | |

| Dave Perrigan | 2018 | |

| Shane Prim | 2018 | |

| Michael Prodigalidad | 2018 | |

| Craig Riggall | 2018 | |

| Viktor Szemerei | 2018 | |

| Sam Webb | 2018 | |

| Charles Betters | 2017 | |

| Jeffery Blick | 2017 | |

| Aaron Johnstone | 2017 | |

| John Kidd | 2017 | |

| Dean Klein | 2017 | |

| Matthew Lanser | 2017 | |

| Michael Pettingill | 2017 | |

| Tyler Prieb | 2017 | |

| James Rosenquist | 2017 | |

| Adam Sinnett | 2017 | |

| Andrew Warner | 2017 | |

| Jeffrey Chipriano | 2016 | |

| Ryan Dennis | 2016 | |

| Eric Fields | 2016 | |

| Dianne Geary | 2016 | |

| Richard Gimpel | 2016 | |

| Robert Holman | 2016 | |

| Steven Johnstone | 2016 | |

| Ben Jolliffe | 2016 | |

| Paul Y. Kim | 2016 | |

| Paul LeFavor | 2016 | |

| Adam Mabry | 2016 | |

| Christopher Smithson | 2016 | |

| Jason Jolly | 2015 | |

| Eric Mitchell | 2015 | |

| Kevin Shoemaker | 2015 | |

| Pei Tsai | 2015 | |

| Tina Walker | 2015 | |

| Maria Colfer | 2014 | |

| Paul Hamilton | 2014 | |

| Thomas Harr | 2014 | |

| Phillip Hunter | 2014 | |

| Jon Jordan | 2014 | |

| Jeff Lammers | 2014 | |

| David Reichelderfer | 2014 | |

| Clell Smyth | 2014 | |

| Jordan Vale | 2014 | |

| Glenn Waddell | 2014 | |

| William Cron | 2013 | |

| Andrew Hambleton | 2013 | |

| Ian Macintyre | 2013 | |

| Brian Ruffner | 2013 | |

| Paul Schlehlein | 2013 | |

| John Spina | 2013 | |

| Geoffrey Stabler | 2013 | |

| Nathan Carr | 2012 | |

| Joe Chestnut | 2012 | |

| Christopher DiVietro | 2012 | |

| Alicia Gower | 2012 | |

| Matthew Harlow | 2012 | |

| Robert Huffstedtler | 2012 | |

| Matthew Lukowitz | 2012 | |

| Matthew Monahan | 2012 | |

| Robert Olson | 2012 | |

| Sam Sinns | 2012 | |

| Michael Chipman | 2011 | |

| Keith Elder | 2011 | |

| Robert Getty | 2011 | |

| Aaron Hartman | 2011 | |

| Christopher Haven | 2011 | |

| Frederick Lo | 2011 | |

| Scott McManus | 2011 | |

| David Palmer | 2011 | |

| Steven Saul | 2011 | |

| Frank Sindler | 2011 | |

| Bruce Smith | 2011 | |

| David Stiles | 2011 | |

| Linda Stromsmoe | 2011 | |

| Ying Chan Fred Wu | 2011 | |

| Patrick Donohue | 2010 | |

| Chuck Goddard | 2010 | |

| Steve Hays | 2010 | |

| David Herding | 2010 | |

| Samuel Masters | 2010 | |

| Landon Rowland | 2010 | |

| Jason Wood | 2010 | |

| Gerald L. Chrisco | 2009 | |

| J. L. Gerdes | 2009 | |

| Joseph C. Ho | 2009 | |

| Dan Jensen | 2009 | |

| Michael H. McKeever | 2009 | |

| Michael Newkirk | 2009 | |

| Andrew Sherrill | 2009 | |

| Anthony R. Turner | 2009 | |

| Jason Webb | 2009 | |

| Mark A. Winder | 2009 | |

| Renfred Errol Zepp | 2009 | |

| Daniel A. Betters | 2008 | |

| Lynnette Bond | 2008 | |

| Claude Marshall | 2008 | |

| Robinson W. Mitchell | 2008 | |

| James W. Ptak | 2008 | |

| Randy C. Randall | 2008 | |

| Ken Stout | 2008 | |

| Shin C. Tak | 2008 | |

| Daniel A. Weightman | 2008 | |

| Ronald S. Baines | 2007 | |

| Erick John Blore | 2007 | |

| Phillip Gene Carnes | 2007 | |

| Kevin Chiarot | 2007 | |

| J. Grady Crosland, M.D. | 2007 | |

| Natalie P. Flake | 2007 | |

| Dante Spencer Mably | 2007 | |

| Jim Maples | 2007 | |

| Daniel Millward | 2007 | |

| Timothy James Nicholls | 2007 | |

| Greg Schneeberger | 2007 | |

| Steven Walker | 2007 | |

| Michael Winebrenner | 2007 | |

| Andrew Young | 2007 | |

| Richard G. Abshier | 2006 | |

| Dennis Di Mauro | 2006 | |

| Jeffrey Hamling | 2006 | |

| Jonathan Ray Huggins | 2006 | |

| Bradley D. Johnson | 2006 | |

| Ronald A. Julian | 2006 | |

| Noah Denver Manring | 2006 | |

| Daniel Craig Norman | 2006 | |

| James Mark Randle | 2006 | |

| Garry M. Senna | 2006 | |

| Joseph Olan Stubbs | 2006 | |

| Young C. Tak | 2006 | |

| Stephen R. Turley | 2006 | |

| Jeremy Alder | 2005 | |

| John Gordon Duncan | 2005 | |

| Mary Lyn Huffman | 2005 | |

| Gregory Perry | 2005 | |

| Taylor Wise | 2005 | |

| Joshua Guzman | 2004 | |

| Trevor C. Johnson | 2004 | |

| Michael Munoz | 2004 | |

| Yaroslav Viazovski | 2004 | |

| Jack Williamson | 2004 | |

| Dale Courtney | 2003 | |

| Bruce Etter | 2002 |

188 Theology Topics for Discussion, Thesis, & Research Paper

As you may know, theology is the study of religion: its history, traditions, philosophy, morality, and literary works. Are you looking for theology topics? Here, you’ll find plenty of interesting theology topics to write about! Our extensive list includes ideas for a research paper, essay, and discussion, along with theology thesis topics. Read on to discover the most engaging biblical and Christian theology research paper topics and more!

🏆 Best Theology Topics for Discussion

✍️ theology essay topics for college, 👍 good theology research topics & essay examples, 🎓 most interesting theology research paper topics, 🔎 unique theological research topics, 💡 simple theology essay topics, ⛪ master of theology thesis topics, ❓ questions about theology, ✝️ christian theology topics, 📖 biblical theology topics.

- Saint Augustine vs Aquinas: Theological Approaches Comparison

- Eternal Life in John’s Gospel: Theological Perspective

- “Psychology, Theology, and Spirituality in Christian Counseling” Book by McMinn

- Theology: Virgin Mary as a Goddess

- “Christian Theology” by Millard J. Erickson

- The Ashari Theology in Sunni Islam

- Missional Praxis: The Fruit of Theological Reflection

- Theological Translatability, Inspiration, and Authority in Religious Traditions The genesis of human inspiration is a major topic in almost every religion. Degrees of the authoritativeness of scriptures are another important thing in religious traditions.

- Psychology and Theology: Worldview Issues, and Models of Integration The model views theology and psychology as valid disciplines that should not be in conflict as both contribute to the contemporary understanding of human nature.

- Theory and Theology of Helping People The theoretical approach to helping people is found in biblical, Christian, and Church values different from the psychology of helping people.

- Leadership in Church and Its Theological Aspects In theology, leadership has various meanings, but all have their foundation in Christ. All leaders aspire to follow in the footsteps of Jesus and lead others to redemption.

- Scriptural Authority and Theological Interpretation Scriptural authority and theological interpretation are two distinct and different topics. According to Entwistle (2021), scripture is incredibly authoritative.

- Theological Vision of “Pleasantville” by Gary Ross “Pleasantville” by Gary Ross is a movie that brilliantly shows how worldviews are transforming, causing rapid social change.

- Theological Challenges Between Judaism and Christianity Judaism originated from the covenantal relationship between the Jews and God. Christianity emerged from Judaism, and both faiths believe that God is the creator of the universe.

- Global Mission Theology of Samuel Escobar In his thesis on Global Missions, Samuel Escobar, a Latin American theologian, argues that Christian theology is contextual.

- Neo-Orthodoxy Theology: Barth, Brunner et al. Neo-orthodoxy is a concept used in advanced contemporary theology. This essay seeks to evaluate the theologies of Barth, Brunner, Bultmann, and Niebuhr.

- Theology of Family Life, Marriage and Parenting Religious marriage is possible when a ceremony is conducted (simultaneously or separately, depending on religion) with the couple being wed in the eyes of God.

- Biblical Theology of Sexuality and Sex Sexuality, coupled with loyalty, is God’s gift for lovers who want to start a family and be with each other for a long time.

- Understanding the Holy Trinity in Christian Theology The assertion the solo God lives as or in 3 mutually supernatural beings is a popular way to describe the Christian belief of the Holy Trinity.

- The Importance of Theological Study of Film The research paper seeks to build a constructive discussion by defying the notion that although the theological study of films is trendy, it is ultimately a meaningless exercise.

- Theology: Discipleship and a Healthy Church The report presents a disciple-making plan aimed to improve the organization’s efficiency in the task of making disciples and boost evangelistic efforts.

- Narrative Theology: Biblical Metanarrative Biblical metanarrative can underpin systematic and biblical theology, presenting a progressive narrative of God’s revelation to mankind.

- Christian Theology and World Religions: Christianity and Islam Christianity and Islam share many similarities, although they are two distinct religious traditions. The paper analyzes their similarities and differences.

- Apologetics as a Theological Discipline Apologetics is an old discipline of theology that involves the defense of ones’ religious position by systematically reasoning out disputed issues.

- The Religious Pluralism Theological Framework The current theological framework for responding to religious pluralism was significantly shaped by Alan Race’s threefold typology.

- Psychological and Theological Perspectives on Anthropology Psychological and theological perspectives on anthropology have some things in common; for example, they employ the scientific method to some extent.

- Psychology and Christian Theology Integration Finding connections between psychology and Christian theology might be a first step toward integration, and an integrative perspective can lead to the search for parallels.

- Liberation Theology in Mid-20th Century Latin America Liberation theology is a movement in Catholic beliefs and socioeconomic mobility which emerged in mid-20th century Latin America.

- Liberation Theology and Its Expressions This essay delves into and delineates the uniqueness of three expressions of liberation theology within the context of each other.

- Theological Differences Within the Major Christian Traditions Christians are followers of Christ who use the bible as the primary religious book for conducting services and personal spiritual nourishment.

- The Holocaust Impact on Jewish Theology Holocaust had a major impact on Jewish theology by providing an earth-shattering tragedy the likes of which the Jewish have never seen in the past, to explain.

- The Research of Theological History There is a hermeneutical problem in Genesis 1: other approaches exist apart from a traditional one; the summary approach to view entered theological debates in the twentieth century.

- Predestination: The Theological Concept In theology, predestination is the belief that God has predetermined all events, generally concerning the person’s ultimate fate.

- “Psychology, Theology, and Spirituality in Christian Counseling” by Mark McMinn In “Psychology, Theology, and Spirituality in Christian Counseling,” Mark McMinn comes up with a healing model, which involves need, sense of self, and relationship with God.

- Theology of Hope: Moltmann and Pannenberg This essay attempts to compare and contrast the theologies of Moltmann and Pannenberg within the rubric of Theology of Hope.

- Thomas Aquinas: Philosopher and Theologian To this day, Aquinas is widely studied by the philosophy scholars all around the world as a great example of a pragmatic Christian theologian and philosopher.

- Calvinism and Arminianism in Historical Theology Calvinism and Arminianism are theological systems that introduce methods to explain the relations which develop between God and people, which are directed to achieve salvation.

- Biblical Theology and How to Practice It Scholars have used different evangelical approaches to accurately articulate the significance of Christ-themed biblical theology and its prospects.

- Theology and Contextualization in Latin America This paper discusses theology and contextualization in Latin America and aims to give a full-fledged description of contextualization’s impact.

- The Positioning of Systematic Theology The paper states that the purpose of theology is not to investigate God’s phenomenon but to explore issues of belief and approaches to following biblical teaching.

- Evangelical Theology of Grenz and Olson This essay evaluates Evangelical Theology in terms of the affirmations of Grenz and Olson defining what God’s transcendence and immanence are in relation to Evangelical Theology.

- Process and Secular Theology: Tillich and Bonhoeffer This essay proceeds by delving into the connection between the theology of Tillich and Process Theology and the connections between the thoughts of Bonhoeffer and Secular Theology.

- Thinking through Paul: Survey of His Life, Letters and Theology The authors of the book “Thinking through Paul: Survey of His Life, Letters and Theology” wanted to analyze the significance of Paul’s life to Christians.

- Theological Reasoning as a Basis for Faith Theological reasoning strives to pose questions and answer them in terms of sacred theology. Meaning, essences, causes, distinctions, and so on compose the core of reason.

- Holistic Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology The holistic mission provides worshiping, evangelism, dialogue among religions, compassion, seeking justice, peacemaking, ecological protection, and social responsibility.

- Philosophical Anthropology and Theological Perspectives Despite their methodological differences, psychological and theological viewpoints on philosophical anthropology share a high degree of agreement.

- Augustine and Organization of Latin Theology Donatists were exclusively an African schismatic sect who viewed themselves as the true heirs to Christianity and claimed to be the church of martyrs.

- Book Review of “Paul the Jewish Theologian” by Young In the book “Paul the Jewish Theologian”, Young reveals Saul of Tarsus as a rejected individual who never departed from his Jewish roots.

- The Incarnation of Christ: Theological Survey The theory of the Incarnation of Christ is the central teaching of the Christian church. It says that God took a fleshly appearance and a human nature.

- Paul, the Jewish Theologian by B. H. Young The title of the selected book for this review is Paul, the Jewish Theologian: A Pharisee among Christians, Jews, and Gentiles.

- Integrated Theory of Leadership from Theological Perspective This paper has demonstrated that the integrated theory of leadership relies on an adaptive leadership style and theological beliefs.

- White Theology and Its Core Characteristics This paper looks at the factors that distinguish white theology and the ways in which it manifests itself in the Pentecostal church.

- The Theology of Christ Through the Ancient Ecumenical Councils It is essential to trace the development of Christ’s theology through the ancient ecumenical councils and reflect on how they developed the Church’s understanding of Jesus.

- Divine Currency: The Theological Power of Money in the West Money in Christianity is a dangerous matter, which requires careful and proper management to stay on the path of Christ.

- The Theology and Science Roles and Relationships The relationship between science and faith is a relevant topic in theology, and the synthetic approach is one of the most viable solutions.

- “Grace Without Nature”: Theological Understanding of the Imago Dei The essay “Grace without Nature” significantly contributes to expanding human understanding of the meaning of the formula imago Dei.

- Early Christology: Historical Theology Historical theology provides research on the way that the Church has undergone interpreting the Scripture under various conditions determined by the different epochs.

- The Old Testament Theology Review This paper provides the Old Testament theology review, including approaches to Old Testament theology, discussing God and creation, worship and sacrifice, God and the future.

- Integration Model: Theological Reasoning The paper dissects a case study of two couples who are unmarried. It references Piaget, Freud, and Sullivan’s psychological theories and offers adaptations.

- Latin American Liberation Theology Latin American liberation theology was the prime example of contextual theology manifesting in the region, where the praxis model or method of theology was utilized.

- Peculiarities of Religious Belief in Theology The intended audience is theologians and religious communities as well as all people interested in the issue of belief.

- Natural Theology Book by William Paley In his book Natural Theology, William Paley paid considerable attention to the criticism of contemporary transformist concepts.

- Theology: Japan’s View of Christianity Christianity is one of the most extensively practiced religions worldwide, and, in some countries, it even has the status of a state religion.

- Liberation Theology and Gutierrez’s Contribution to It This essay will examine liberation theology’s background and provide a detailed overview of Gutierrez’s contribution to it.

- Theological-Political Treatise According to Spinoza, superstition stems from the willingness of individuals not to link everything to certainty.

- Biodiversity, Environmental Ethics and Theology This paper will focus on the issue of decreasing biodiversity, explaining how environmental ethics and theology apply to this problem.

- The Limits of Language in Theology Apophatic theology suggests that everyone should try to reach beyond the image someone creates when speaking about God, his essence, or plans regarding humanity.

- Lutheran Theology – Insights for Today’s Church Martin Luther’s theology started the reformation in Germany through his famous 95 Theses and, in doing so, helped model the contemporary society and Protestant Church.

- Theology in the Context of World Christianity Perception of shame and guilt in different cultures plays an important role in people’s personalities and their vision of the world itself.

- Lutheran Theology and Its Implications for Contemporary Church and Society This study, therefore, focuses on Lutheran theology and explains why Luther can be regarded as the founder of the modern church and society.

- Malcolm X, a Revolutionary. Philosophical Theology Malcolm X is the eminent personality of the 20th century, widely known for his combat against African-American harassment.

- Theology Doctrine Universalism The purpose of this paper is to discuss universalism. Universalism is a doctrine in theology that refers to universal salvation.

- Christian Theology and World Religions Religion in the context of human history has been a part of people’s existence for many centuries; for some, gods were the creators of the word and its masters.

- Martin Luther King and His Theology Analysis Martin Luther was born in the age of Renaissance, which was blossoming with its artists and their works and which had a positive impact on the development of his personality.

- Religious Study and Theology. I AM statements I AM statements are found both in the New and Old Testament. In the New Testament, the Gospel according to John emphasizes the statements.

- Religious Studies and Theology: Paganism in the Military Paganism has spread far and wide in society. From academia to the military, the practice of paganism is being accepted and accommodated just like other religions.

- Theology History: Forms of Beliefs Humans began to worship physical forms commonly seen around them in the form of oceans, mountains, the sun and the moon, animals, and even weather.

- Theology Concepts Brief Review The gentiles were religiously accepted as Christians by the early Christians because they both common beliefs Jesus Christ.

- Religious Studies & Theology: The Davidic Kingdom The paper is about David – one of the most prominent rulers who united many tribes and established a strong monarchy for the people of Judah and Israel.

- Black Theology and Its Impact on Drug Addiction I have chosen the topic of Black Theology and its impact on drug addiction because I have experienced the impact of opioid addiction on my family.

- Theology in the Enlightenment Age The enlightenment age started gaining momentum in the 13th when Thomas Aquinas recovered the Aristotelian logic that was primarily used in defending Christianity.

- Roman Catholic Theology of Rahner and Kung This article evaluates the theology of Rahner and Kung in terms of how much they pushed for the envelope of traditionally accepted Roman Catholic theology.

- Courage and Paul Tillich’s Philosophy and Theology The research argues that courage is not merely an ethical value but an ontological conception and is opposed by the classical purely moral perspective on courage.

- Marriage Theology Through the Protestant Reformation

- Human Qualities Within Theology

- Christian Theology and Greek Culture

- The Youth and Islam Theology

- Understanding Dialect, Philosophy, and Theology Through Scholasticism

- Relationship Between Theology and Spirituality

- Philosophy, Theology, and Ideology

- Christian Worship Music and Theology

- Roman Catholic Theology and Contemporary Culture

- Relationship Between Science and Theology

- Biblical Foundations for Health Theology

- Theology and Theologians: Differences and Similarities

- Biblical Foundation for Developing Contextual Theology

- Immortality: Philosophy and Theology

- Christian Theology and the Doctrine of Evangelism

- Influential Ideas for Protestant Theology

- The Universalism and Annihilationism Theology

- Holy Trinity and Systematic Theology

- Christian Theology, Family, and Marriage

- Wesleyan Theology and the Concept of Salvation

- The Theology and Anthropology of Mormonism

- Appropriation, Politics, and Theology in the Gospel of Mark

- Liberation Theology and the Catholic Church

- Galileo Galilei and His Impact Theology

- Sexual Theology: Biblical Insight on Sexuality

- Wilfred Cantwell Smith’s World Theology

- Understanding Political Theology and Its Application in the Canadian Democracy

- The Most Important Contribution to Eucharist Theology

- Relationship Between Theology and Natural Science

- Christian Mediation and Theology

- Catholic Moral Theology and the Medical Field

- Buddhist and Christian Ethics Theology

- John Calvin and the Calvinist Theology

- Christian Theology and Feminist Theology

- The Relationship Between Theology and Economics: The Role of the Jansenism Movement

- Comparative Feminist Theology Analysis

- Twentieth-Century Christian Theology and ‘Holiness’

- John and Matthew’s Theology

- Hierarchical Church and Liberation Theology

- Contemporary Theology and Orthodoxy of the New Testament

- Christian Theology and Market Economics

- Biblical Paradigm and Ministry Theology

- Jerusalem Politically Contested City Theology Religion

- Urban Theology Using the Old Testament

- Christian Theology and Religious Beliefs

- Catholic Theology and Scripture Assignment

- Family and Mass Media Influences Theology Religion

- Church History and How It Fits With Biblical Theology

- Mathematics and Theology Blossoming Together

- Christian Counseling, Theology, and Spirituality

- African American Women and Womanist Theology

- Philosophy and Christian Theology

- Christian and Navajo Creation Theology Religion

- Integrating Psychology With Christian Theology

- The Theology, Christology, and Pneumatology of the Book of Revelation

- Integrating Change Models and the Theology of Leadership

- Christianity and Faith, Evangelization, Life and Theology

- Liberation Theology and Discernment

- Anne Hutchinson and Her Theology Theory

- Psychology Theology and Spirituality in Christian Counseling

- Does Religious Theology Undermine the Basic Doctrines of Christianity?

- What’s the Difference Between Reformed Theology and Calvinism?

- What Is the Contribution to and Impact of Feminist Theology in Judaism?

- Is Christian Theology More Modern Than Islamic Theology?

- What Is the Difference Between Philosophy and Theology?

- How Does Mormon Theology Explain Intersex People?

- How Does Moral Theology Differ From Moral Philosophy?

- What Is the Difference Between ‘Biblical’ and ‘Systematic’ Theology?

- Is Constantly Asking Questions a Good Way to Get Better at Christian Theology?

- How Did the Reformation Influence Eucharistic Theology?

- Is Theology an Actual Science or a Pseudoscience?

- What Is a Relationship Between Religion and Theology?

- Has Theology Made Any Contribution to Knowledge in the Past 500 Years?

- Is It True That Early Christianity Was Much Closer to Islam in Theology?

- What Is the Purpose of Heaven and Hell in Christian and Islamic Theology?

- What Parts of Hindu Theology Are Similar to Greek Theology?

- What Effect Did Plato Have on Augustine and the Origins of Christian Theology?

- What Are Some of the Most Controversial Views in Christian Theology?

- What Is the Fundamental Theology Behind Why Jews Disagree With Islam?

- How Do Jehovah’s Witnesses Reconcile Matthew 8:11 With Their Theology?

- Is There a Way to Discuss the Deeper Theology of Religion Without the Extremist Positions?

- To What Extent Has “Existentialism” Influenced Theology?

- What Are Some Examples of the Apophatic Nature of Orthodox Theology?

- Why Is It Important to Differentiate Spirituality, Theology, and Philosophy?

- How the Church Handles Postmodernism Theology?

- The concept of the Holy Trinity and its significance in Christian theology.

- Atonement in Christianity: an analysis of different theories.

- Theodicy: the issue of evil in the world created by benevolent God.

- The views of death and afterlife in Christian eschatology.

- Different theological perspectives on the nature of God.

- Bioethics from the Christian ethics perspective.

- The meaning and significance of Christian sacraments.

- The role of women in Christian theology.

- Liberation theology and its connection to social justice.

- Faith and science: Christian views on evolution and the origin of the universe.

- Covenant theology as an approach to interpreting the Bible.

- Did Jesus Christ fulfill the messianic prophecies in the Old Testament?

- Analysis of the biblical concept of the Kingdom of God.

- A historical-critical approach to interpreting the Bible.

- The role of the Mosaic Law in the Old and New Testaments.

- Analysis of ethical teachings of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount.

- Prophets’ call for social justice: analyzing the Old Testament.

- The apocalyptic imagery in the Book of Revelation.

- How does the Bible address the problem of suffering?

- The biblical understanding of Israel as God’s chosen people.

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, March 1). 188 Theology Topics for Discussion, Thesis, & Research Paper. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/theology-essay-topics/

"188 Theology Topics for Discussion, Thesis, & Research Paper." StudyCorgi , 1 Mar. 2022, studycorgi.com/ideas/theology-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) '188 Theology Topics for Discussion, Thesis, & Research Paper'. 1 March.

1. StudyCorgi . "188 Theology Topics for Discussion, Thesis, & Research Paper." March 1, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/theology-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "188 Theology Topics for Discussion, Thesis, & Research Paper." March 1, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/theology-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "188 Theology Topics for Discussion, Thesis, & Research Paper." March 1, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/theology-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Theology were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on June 24, 2024 .

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Theology Proper - Questions and Answers

This is a series of theological essays on important questions concerning the doctrine of God!

Related Papers

https://www.swrktec.org/theology

Herb Swanson

We surface a brief overview of a few of the problems of contemporary theology, in hope that readers will find a fresh starting place in old evidence: a place to build a consensus that reaches for unanimous agreement in the Spirit.

Domenic Marbaniang

THEOLOGY is about God and Creation, or more precisely perhaps about our ideas of them, how they are formed and somewhat justified, although it is stressed that they can be neither proved nor disproved. This book is a thematic compilation drawn from past works by the author over a period of thirteen years. A new essay was added in 2022.

The Doctrine of God is an introductory textbook aiming to provide a clear and concise introduction to the doctrine of God by addressing some big questions concerning divine attributes and the God-world relationship in mainly recent Christian theology. More precisely the book provides an issue-focused presentation on selected contemporary perspectives. The book in its coverage is however not limited only to recent Christian debates, but frequently features also philosophical and historical voices which complement the debates. The book is therefore not a book in historical theology, or philosophical theology, but rather a book in systematic theology proper covering the contemporary debates relating to major questions surrounding the doctrine of God. Since the book is framed as an introductory textbook its readership is assumed to be mostly students of theology. Given the level of the presented material, its dense and detailed nature will primary be most beneficial to graduate level (p...

Amenu Daba D A B A Waktola

Edward Seely: How Can Churches Facilitate Education Leading to Maturity in Jesus Christ Worldwide?

This PowerPoint presentation on the first of the six loci (Biblical doctrines) of historic Christian systematic theology is an abbreviated version of the accompanying Overview of the Theology section in the larger unabridged PowerPoint (PPT) program, “Essential Christianity: Historic Christian Systematic Theology—With a Focus on Its Very Practical Dimensions, Including God’s Answers to Our Great Questions of Life—for Now and Eternity.” For use in classes that have time constraints, this further condensed version with highlighted subjects indicates the minimum topics to be addressed in class. Ask the class to read the larger version(s), at least the Overview, prior to the class session. Provide opportunities for discussion of any of the subjects in the larger version, the abridged version, or related subjects, especially contemporary implications and applications of the Biblical content. Both the larger unabridged, and the abridged, PPTs in expanded sentence outline format, are for the third session of a nine-week course for adults and youth classes, which offer an introductory overview of historic Christian systematic theology with an emphasis on its many practical applications. This program, the third lesson in the third session of this series (the first lesson, an overview of the overview, needs the first two sessions in an average class of 50 minutes), introduces the doctrine of God, the first of the six loci, of systematic theology. It answers the question: Who is God; what is he like; what has he done; and what is he doing? It also offers a brief look at what God will do in the future, returning to the rest of that subject when the class discusses eschatology, the doctrine of the last things or the end time. This study of the Biblical teaching about God answers why our study needs to begin with God, and then the following Biblical doctrines become much more understandable. For further information on each subject in this course, the teachers and students can access the unabridged PPT on the Christian Theology page of the author’s general Website at https://fromacorntooak12.com/ or on his academic Website at https://seelyedward.academia.edu/research. Each of the PowerPoint presentations is written in an expanded sentence outline format in order to provide a stand-alone resource for teachers, students, and others, including those using it for independent study and/or devotional purposes. Week nine is for a review and discussion of matters the class wants to address. See also the related loci, doctrines, on this Website.

Johannes Zachhuber

Sarah Yardley