Train Derailments and Collisions

By Leonard Lederman

Since the earliest days of railroads, collisions and derailments have been a constant danger for both passengers and railroad workers. Large-scale disasters have been relatively rare in the Philadelphia region, despite its important role in railroad operation and development. However, news coverage, public outrage, and government intervention resulting from rail accidents around the country forced prominent companies such the Pennsylvania Railroad to adopt new safety technologies and regulations to ease public fears, restore efficiency, and increase daily traffic. Accidents highlighted failures or absences of railroad safety measures locally and across the United States.

Collisions and derailments occurred despite ongoing efforts to improve railroad safety. In the late nineteenth century, railroad companies sought to improve the durability of tracks by switching from iron to steel rails and to reduce accidents by building parallel tracks that allowed trains to pass each other. The Interstate Commerce Commission , created in 1887 to regulate transportation, issued a series of regulations requiring railroad companies to comply with safety regulations. Over time, new technologies such as Automatic Train Stop and eventually electric Automatic Train Control systems and in-cab signaling developed to forcibly stop trains if warning signals were ignored. However, many railroad companies hesitated to implement such costly equipment.

On early railroads of the nineteenth century, multiple trains traveled inbound and outbound on the same lines, making communication key to avoiding collisions and other track hazards. On a single-track road, a train would have to use a siding track off the main line to wait for another train to pass. Before the days of two-way radios, train crews had to rely on schedules, telegraphs at station stops, or simple line of sight in order to locate another train. These capricious methods were often vulnerable to a large degree of human error.

Great Train Wreck of 1856

Such was the case on July 17, 1856, in an event that came to be known as the Great Train Wreck of 1856. That day at the Cohocksink depot in the Kensington section of Philadelphia, a North Pennsylvania Railroad excursion train called the “Picnic Special,” carrying children from St. Michael’s Roman Catholic Sunday School, left the depot later than scheduled. Farther down the line at the Wissahickon station, the crew of the regularly scheduled train the Aramingo had no way of knowing that the Picnic Special was running late and so, after a brief period of waiting, pulled out of the station on the single-track line. The conductor intended to use a siding at Edge Hill to allow the Picnic Special to pass. However, the two trains collided around a blind curve by Camp Hill station, near the site of future Ambler, killing fifty-nine and injuring around one hundred. Immediately following the accident, Wissahickon resident Mary Johnson Ambler (1805-68) packed first-aid supplies and traveled the two miles from her home to care for the wounded. Years later, her heroics inspired the North Pennsylvania Railroad to rename the Wissahickon station as Ambler after her, and the town also took her name in 1888.

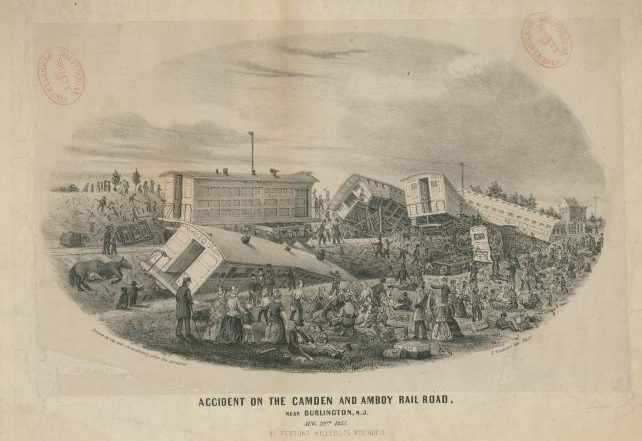

A similar incident had occurred in South Jersey on the Camden-Amboy Railroad on August 29, 1855. In this accident, two trains traveling in opposite directions on the single-track line between Philadelphia and New York spotted each other down the road near Burlington. The northbound train began to reverse. Down the line at a road crossing, a local doctor was driving his two-horse carriage, but windy weather caused dust clouds and made it difficult for both the brakemen and the doctor to see. The train struck the two horses and derailed four of the five train cars. This accident left twenty-one dead and sixty to one hundred wounded, although the doctor was unharmed. These accidents and subsequent derailments, among other highly publicized disasters nationally in the 1850s, aroused public outcry for increased railroad safety and highlighted the dangers of railroad travel in absence of safety measures.

Many railroads did not become double-tracked until traffic increased during and after the Civil War. The Pennsylvania Railroad Company planned its Main Line, connecting Philadelphia to Harrisburg and Pittsburgh, to be double-track from its inception. However, the economic Panic of 1857 halted the double-track progress until the increased traffic of the Civil War made it necessary.

During the Civil War, as Union and Confederate forces used railroads heavily, railroad companies depended on poor quality British iron for tracks that quickly wore out and caused numerous derailments. After the war, railroads turned instead to steel as sturdier and better suited for newer, heavier cars and more powerful locomotives. By the late 1870s, the Independent Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad became one of the first American railroads to install steel rails along its main line. By 1914, Pennsylvania Railroad executives concerned with railroad productivity, more than passenger safety, also recognized broken rails to be a leading cause of derailments.

Automatic Train Stop Systems

Automatic Train Stop (ATS) systems, first patented by Pennsylvania Railroad workers in 1880, added an element of safety by preventing trains from passing restrictive signals. The initial system worked by dropping a bar on the train if it passed a stop signal. The bar would smash a glass cylinder on the locomotive, which would then release air pressure from the brake line and stop the train. In 1922, the Interstate Commerce Commission mandated that forty-nine major railroads implement ATS on at least one passenger division by 1926. However, ATS could not prevent derailments caused by speeding or stalling on a descent. This still remained in the hands of the engine man.

After excessive speed caused a train to derail in February 1947 near Gallitzin in central Pennsylvania, the ICC required all railroads to install cab signaling (in-cab displays corresponding with outside signal lights) or ATS where passenger trains exceeded 72 miles per hour. Finally, after an engine, Red Arrow , sped through a stop signal and collided with the rear end of the Philadelphia Night Express at Bryn Mawr on May 18, 1951, the Pennsylvania Railroad committed to installing cab signaling and Automatic Speed Control, or Automatic Train Control (ATC) as it came to be known. ATC uses electric pulses from the rails to apply the brakes on trains exceeding the speed limit. Similarly, on diesel and electric trains, “dead man” switches could stop the engine should the engineer become incapacitated.

One location, the Frankford Junction curve in Philadelphia, became the site of two accidents seventy-two years apart. On September 6, 1943, PRR’s Congressional Limited derailed as a result of loose equipment in the train’s under carriage. Due to its speed, the train could not respond to the signalman’s warning in time to stop. This accident left seventy-nine killed and 118 injured. Years later, on May 12, 2015, Amtrak train 188 entered the Frankford Junction curve at around 102 mph and flew off the tracks. The track had been recently equipped with Positive Train Control (PTC, a more advanced form of ATC), but it was not yet operational. Had PTC been active, the train’s excessive speed would have triggered the brakes upon passing a warning signal. Eight people were killed and more than two hundred were injured.

The absence of safety measures continued to be one of the leading causes of train derailments. Public outcry over accidents in the earlier, unregulated days of railroads precipitated the creation of safety innovations that protected and saved lives. With a large degree of railroad traffic, the greater Philadelphia region became a testing ground for these innovations. The decline in accident frequency demonstrated that with increased safety technologies, railroads could operate more efficiently and safely. Although train crews no longer operated blindly, in the absence of long-developed safety measures, the rails could still be a dangerous place.

Leonard Lederman earned his master’s degree in history at West Chester University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Major Train Derailments in Greater Philadelphia

November 8, 1833: Hightstown Rail Accident, Hightstown, New Jersey. An overheated journal box caught fire underneath one of the carriages on a Camden & Amboy train between Hightstown and Spotswood, New Jersey, causing an axle to break and derailing the train. The derailment killed one and injured twenty-three. Among the wounded was future New York Central railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877). Also on board the train was former president John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) who, in his journal, recorded the horror of witnessing the wounded victims. This derailment may have been the first fatal passenger train accident in U.S. history.

August 2, 1853: Sunset Cow Wreck, Bulls Island, Lambertville, New Jersey. At sunset, a Belvidere Delaware Railroad train struck a cow on the tracks. Six cars derailed, killing eleven.

August 29, 1855: Camden-Amboy Railroad Wreck, Burlington, New Jersey. Twenty-one people died and sixty to one hundred were injured after a train struck two horses pulling a carriage, causing four cars to derail.

July 17, 1856: Great Train Wreck of 1856, Ambler, Pennsylvania. A regularly scheduled North Pennsylvania Railroad passenger collided with a late excursion train, killing fifty-nine and injuring around one hundred.

October 4, 1877: Milford Wreck, Kimberton, Pennsylvania. Torrential rain from a large tropical storm caused the ground under the tracks near Kimberton to erode. A three-car Philadelphia and Reading Railroad train plunged into the thirty-foot chasm, killing seven.

S eptember 19, 1890: Shoemakersville, Pennsylvania. After two coal trains collided and spilled timber and coal onto a passenger train track, a fast-moving Pottsville Express passenger train struck the coal debris and plunged into the Schuylkill River. Twenty-two people died and more than thirty were injured.

July 30, 1896: Atlantic City, New Jersey. A Reading Railroad Express train plowed into the side of Pennsylvania Railroad Red Men’s excursion train, killing around fifty and injuring over sixty.

December 3, 1903: Greenwood, Delaware. A winter snowstorm, resulting in decreased visibility, caused two trains to collide in the town of Greenwood. One train carried naphtha, a highly flammable liquid, which exploded with such force that Greenwood inhabitants reported glass shattered in almost every building in town. Only one brakeman and a nearby infant were killed, but the resulting fires wounded many and destroyed nine buildings, leaving locals homeless during the snowstorm. Firefighters could not respond until the following morning because the explosion had destroyed telegraph lines.

October 18, 1906: Atlantic City. Improperly placed tracks on a trestle bridge outside Atlantic City caused a West Jersey and Seashore Railroad train to derail, plunging several cars into the mud and water. Fifty died from drowning in the mud and rising water levels. A grand jury exonerated the elderly bridge tender but found the railroad company at fault for improperly placed tracks and a lack of mechanical warning signals.

November 27, 1912: “Sagging Bridge,” Glen Loch, Pennsylvania. The Cleveland Flyer train derailed as the result of a sagging bridge on the Pennsylvania Railroad line. Eight cars derailed, killing four and wounding forty-nine. Investigations found that a cover plate on the bridge had ruptured but could not determine the cause. Evidenced also showed that the train began to derail before it reached the bridge.

September 6, 1943: Frankford Junction, Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania Railroad Congressional Limited derailed on the Frankford Junction curve as a result of loose equipment in the train’s undercarriage. Due to its speed, the train could not respond to the signalmen’s warning in time to stop. This accident left seventy-nine killed and 118 injured.

May 18, 1951: Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. A Pennsylvania Railroad train, Red Arrow , sped through a stop signal and collided with the rear end of the Philadelphia Night Express at Bryn Mawr, killing eleven and wounding fifty-seven.

December 26, 1961: York-Dauphin Station, Philadelphia. A four-car SEPTA subway on the Market-Frankford El line entered a curve just before the York-Dauphin station where it hit a guardrail causing the first three cars to derail. One man was killed and thirty-eight people were injured.

March 7, 1990: Philadelphia. Between 30 th and 15 th Street Stations, a dragging motor box caused a subway car to crash through a pillar, killing four and injuring 162.

May 12, 2015: Frankford Junction, Philadelphia. Amtrak train 188 entered the Frankford Junction curve at around 102 mph and flew off the tracks. The track had been recently equipped with Positive Train Control, but it was not yet operational. Had PTC been active, the train’s excessive speed would have triggered the brakes upon passing a warning signal. Eight people were killed and more than two hundred were injured.

April 3, 2016: Chester, Pennsylvania. A maintenance crew foreman neglected to confirm that dispatchers were routing trains around the work zone. As a result, an Amtrak train on the New York to Savannah line collided with a backhoe, killing two maintenance workers and injuring around forty passengers.

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Mary Johnson Ambler

Wikimedia Commons

On July 17, 1856, two trains collided near the Camp Hill railroad station. After hearing of the crash, Mary Johnson Ambler (1805-68), pictured here, traveled the two miles from her home in Wissahickon to the site of the crash and cared for the wounded. Despite her efforts, fifty-nine people died as a result of this accident, later known as the Great Train Wreck of 1856.

In 1869, the North Pennsylvania Railroad renamed the Wissahickon station in honor of Ambler. The village of Wissahickon also took in the name Ambler in 1888.

Congressional Limited Crash

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

On September 6, 1943, the Congressional Limited derailed at the Frankford Junction curve as a result of loose equipment in the train’s undercarriage. The train was traveling too fast to respond to the signalman’s warning to stop. Seventy-nine people died and 118 were injured in the accident. In this photograph, a crowd observes the wreck.

Market-Frankford Derailment

On December 26, 1961, a SEPTA subway train crashed into a guardrail on the Market-Frankford El line causing the first three cars to derail. The train crashed just before the York-Dauphin Station. The accident killed one man and injured thirty-eight others.

Accident on the Camden and Amboy Rail Road

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

On August 29, 1855, two trains traveling in opposite directions on the single-track line between Philadelphia and New York spotted each other near Burlington. One of the trains reversed direction but struck a horse-drawn carriage, causing four of the five train cars to derail. This lithograph, published soon after the event, depicts rescue workers assisting victims among the wreckage, while a crowd flocks to the scene.

Accident North Pennsylvania Railroad

Library Company of Philadelphia

On July 17, 1856, two trains collided near the future site of Ambler, an event that became known as the Great Train Wreck of 1856. The accident occurred when a North Pennsylvania Railroad excursion train called the “Picnic Special” left the depot later than scheduled and hit another train using the same single-track line. This lithograph, produced from a drawing created at the scene of the accident, depicts the chaos that ensued as passengers jumped from the train to escape the smoke and flames.

Related Topics

- Greater Philadelphia

Time Periods

- Twentieth Century after 1945

- Twentieth Century to 1945

- Nineteenth Century after 1854

- Montgomery County, Pennsylvania

- Burlington County, New Jersey

- North Philadelphia

Related Reading

Aldrich, Mark. Death Rode the Rails American Railroad Accidents and Safety, 1828-1965 . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Bezilla, Michael. Electric Traction on the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1895-1968 . University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1980.

Bibel, George. Train Wreck: The Forensics of Rail Disasters . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

Burgess, George H., and Miles Coverdale Kennedy. Centennial History of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, 1846-1946 . Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Railroad, 1949.

Churella, Albert J. The Pennsylvania Railroad, Volume 1 – Building an Empire 1846 – 1917 . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Gallamore, Robert E., and John R. Meyer. American Railroads . Harvard University Press, 2014.

Lee, Warren F., and Tri-State Railway Historical Society. Down along the Old Bel-Del: The History of the Belvidere Delaware Railroad Company, a Pennsylvania Railroad Company . Albuquerque: Bel-Del Enterprises, Ltd, 1987.

Related Collections

- Philadelphia Record Photo Morgue: Railroad Accidents 1936-1946 Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia.

- Pennsylvania Railroad Collection and Reading Company Collection Hagley Museum and Library 200 Hagley Creek Road, Wilmington, Del.

Related Places

- Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania

- The Railroad in Pennsylvania (ExplorePAhistory.com)

- Mary Ambler (Ambler Main Street)

- How Wissahickon Became Ambler (Historical Society of Montgomery County)

- Tragic Train Wreck at 53rd Street and Baltimore Avenue (PhillyHistory.org)

- Is This the Train Tragedy We'll Learn From? (Hidden City)

- Camden and Amboy Railroad (Delaware River Heritage Trail)

Connecting the Past with the Present, Building Community, Creating a Legacy

Essay on Train Accident

The rhythmic hum of wheels on tracks, the distant whistle announcing arrival or departure—trains are iconic symbols of connectivity and travel. However, with their massive size and intricate systems, accidents involving trains can result in devastating consequences. In this essay, we delve into the somber reality of train accidents, exploring the factors that contribute to their occurrence and the profound impact they have on individuals and communities.

Quick Overview:

- Train accidents can stem from mechanical failures, including issues with brakes, signals, or the overall functioning of the train’s components.

- Malfunctions in critical systems can compromise the train’s ability to operate safely, leading to potential collisions or derailments.

- Human error, such as mistakes made by train operators, signalmen, or maintenance crews, can contribute to accidents.

- Miscommunication or failure to follow established procedures may result in trains moving onto the same track or disregarding vital safety protocols.

- The condition of railway infrastructure, including tracks, bridges, and signaling systems, is crucial to preventing accidents.

- Poor maintenance, inadequate inspections, or outdated infrastructure can lead to accidents, especially during adverse weather conditions.

- Adverse weather conditions, such as heavy rain, snow, or extreme temperatures, can impact the safety of train operations.

- Slippery tracks, reduced visibility, and challenges in maintaining traction contribute to the heightened risk of accidents during inclement weather.

- Train accidents can be influenced by factors beyond the railway environment, such as trespassing, vehicular crossings, or intentional actions like vandalism.

- Ensuring the safety of railway zones requires addressing not only railway-specific issues but also broader societal factors contributing to accidents.

Understanding the Causes and Consequences:

Train accidents are often the result of a complex interplay of mechanical failures, human errors, and environmental factors. Mechanical failures, ranging from brake malfunctions to signal issues, pose a significant risk to train safety. When critical components fail to function as intended, it can compromise the train’s ability to navigate tracks safely, potentially leading to collisions or derailments.

Human errors and miscommunication also play a crucial role in train accidents. Mistakes made by train operators, signalmen, or maintenance crews can have severe consequences. Failure to adhere to established procedures, misinterpretation of signals, or lapses in communication can result in trains moving onto the same track or neglecting vital safety protocols, creating conditions conducive to accidents.

The condition of railway infrastructure is paramount in preventing accidents. Poor maintenance, inadequate inspections, or outdated infrastructure can lead to hazardous conditions, particularly during adverse weather. Adverse weather conditions, including heavy rain, snow, or extreme temperatures, present additional challenges. Slippery tracks, reduced visibility, and difficulties in maintaining traction increase the risk of accidents during inclement weather.

Beyond the railway environment, human factors such as trespassing, vehicular crossings, or intentional actions like vandalism can contribute to accidents. Addressing the broader societal aspects that influence train safety is essential to ensuring the well-being of both passengers and communities living near railway zones.

Conclusion:

Train accidents are tragic events that demand a comprehensive understanding of the multiple factors contributing to their occurrence. Mechanical failures, human errors, infrastructure issues, weather-related challenges, and broader societal factors all play pivotal roles in the dynamics of train accidents. Recognizing the complexity of these incidents is crucial for developing effective preventive measures and safety protocols. As we reflect on the impact of train accidents on individuals, communities, and the transportation industry, it becomes imperative to prioritize safety measures and technological advancements that can mitigate the risks associated with train operations. Only through a holistic approach can we work towards a future where the tracks are not only symbols of connectivity but also corridors of safety and well-being.

Rahul Kumar is a passionate educator, writer, and subject matter expert in the field of education and professional development. As an author on CoursesXpert, Rahul Kumar’s articles cover a wide range of topics, from various courses, educational and career guidance.

Related Posts

How To Write An Argumentative Essay On Political Science?

Creative Essay Writing Techniques: How To Write a Creative Essay

10 Lines on My Mother in English

- Share full article

Advertisement

India’s Train Crash: What We Know

Three trains, with more than 2,200 people onboard, were involved in the crash in Odisha State, the deadliest such disaster in decades. The death toll approached 300.

By Alex Travelli Victoria Kim Erin Mendell and Isabella Kwai

- Published June 3, 2023 Updated June 6, 2023

A train crash in eastern India on Friday was the country’s worst rail disaster in two decades, killing more than 270 people and renewing questions about rail safety in a country that has invested heavily in the system — relied on by millions of people every day — in recent years after a long history of deadly crashes.

How many people are confirmed dead?

Two passenger trains collided around 7 p.m. local time Friday after one of them struck a stationary freight train at full speed and derailed in the Balasore District of Odisha State, according to an initial government report. At least 275 people were killed, according to the state government on Sunday, revising an earlier death toll of 288 after an official said that some victims had been counted twice. More than 1,000 passengers were injured.

In a preliminary assessment, officials say the disaster began when the first of the two passenger trains struck the idled freight train at full speed, and then derailed. A second passenger train, heading in the opposite direction, then struck some of the dislocated cars. Officials are focusing on signal problems as the probable cause.

More than 2,200 passengers in all were onboard the passenger trains, according to railway officials, and at least 23 cars were derailed. The force of the collision left cars so mangled that rescuers used cutting equipment to reach victims.

One of the trains was a Shalimar-Chennai Coromandel Express train, according to South Eastern Railway. The Coromandel Express service connects the biggest cities on India’s east coast at a relatively high speed. The other passenger train was a Yesvantpur-Howrah Superfast Express train, running from a commuter hub in the southern city of Bengaluru to Kolkata, the capital of the northeastern state of West Bengal.

India’s railway minister, Ashwini Vaishnaw, said that he had ordered an investigation into the cause and that those affected by the crash would receive compensation .

Site of the train crash

An initial government report said that the Coromandel Express passenger train derailed while traveling at full speed. Some of its cars collided with a freight train loaded with iron ore.

Derailed cars from

second passenger train

Road crossing

Coromandel Express

passenger train

Freight train

carrying iron ore

Bahanaga Bazar

rail station

Derailed cars

from second

Where did the train crash in India?

The crash occurred at the Bahanaga Bazar station near Balasore, a city near the coast in the northeastern state of Odisha. The area is known for its ancient temples and history as a 17th-century British trading post.

Balasore is several hours by car to the nearest airport, in Bhubaneswar, Odisha’s capital. May is usually the hottest time of year, and daily temperatures reached about 100 degrees in the days before the crash.

The rescue operation was over by Saturday. Dozens of trains had been canceled, but crews successfully restored service in both directions late Sunday after clearing the crashed cars off the tracks. But the delays meant that families of the victims struggled to reach the crash site , and many bodies remain unclaimed, according to local officials and doctors.

How common are train derailments in India?

Often referred to as being crucial to India’s economy, the country’s vast rail network is one of the world’s largest, and is central to lives and livelihoods, particularly in more rural pockets. Nearly all of India’s rail lines, 98 percent, were built from 1870 to 1930, according to a 2018 study published in The American Economic Review.

The deadliest accident in the history of Indian rail is believed to have been in 1981, when a passenger train derailed as it was crossing a bridge in the state of Bihar. Its cars sank into the Bagmati River, killing an estimated 750 passengers; many bodies were never recovered.

Derailments were once frequent in India, with an average of 475 per year from 1980 to around the turn of the century. They have become much less common, with an average of just over 50 a year in the decade leading up to 2021, according to a paper by railway officials presented at the World Congress on Disaster Management.

Rail safety more generally has improved in recent years, with the total number of serious train accidents dropping steadily to 22 in the 2020 fiscal year, from more than 300 annually two decades ago. By 2020, for two years in a row, India had recorded no passenger deaths in rail accidents — a milestone hailed by the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Until 2017, more than 100 passengers were killed every year.

Even so, deadly crashes have persisted. In 2016, 14 train cars derailed in India’s northeast in the middle of the night, killing more than 140 passengers and injuring 200 others. Officials at the time said a “fracture” in the tracks might have been responsible. In 2017, a late-night derailment in southern India killed at least 36 passengers and injured 40 others.

The crash on Friday was the deadliest at least since a collision in 1995 about 125 miles from Delhi that killed more than 350 people.

What does the crash mean for Prime Minister Modi of India?

A main reason for the improved safety of the trains was the elimination of thousands of unsupervised railway crossings, which Mr. Modi’s government said had been achieved in 2019. The relatively low-level engineering work of building underpasses and posting more signal conductors also drastically reduced crashes.

Mr. Modi has made it a priority to improve infrastructure, especially transportation systems, around the country. In recent years, the railroads, among the most visible projects for ordinary citizens, have received attention for a series of high-tech initiatives. Mr. Modi has been inaugurating electric medium-range trains and is building a Japanese-style “bullet train” corridor on the west coast to connect Mumbai with Ahmedabad.

On Saturday, though, instead of inaugurating a new train as scheduled, Mr. Modi visited the scene of the train wreck.

The train system, and especially train accidents, have long affected the fortunes of India’s politicians. The cabinet position of railway minister has been one of the most sought-after posts because it is both high-profile and influential in business and industry. Suresh Prabhu, who is credited with designing New Delhi’s world-class subway system, was pressed into resigning from his post in September 2017, after a series of accidents.

Within hours of Friday’s disaster, some opposition politicians were already calling for the resignation of Mr. Vaishnaw.

Mujib Mashal contributed reporting.

Victoria Kim is a correspondent based in Seoul, focused on international breaking news coverage. More about Victoria Kim

Erin Mendell, an editor on the Live news team in Seoul, has edited and reported from Asia since 2016. She joined The Times in 2022 after more than a decade with The Wall Street Journal, most recently in Hong Kong. More about Erin Mendell

Isabella Kwai is a breaking news reporter in the London bureau. She joined The Times in 2017 as part of the Australia bureau. More about Isabella Kwai

IMAGES

VIDEO