Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing Essays in Art History

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Art History Analysis – Formal Analysis and Stylistic Analysis

Typically in an art history class the main essay students will need to write for a final paper or for an exam is a formal or stylistic analysis.

A formal analysis is just what it sounds like – you need to analyze the form of the artwork. This includes the individual design elements – composition, color, line, texture, scale, contrast, etc. Questions to consider in a formal analysis is how do all these elements come together to create this work of art? Think of formal analysis in relation to literature – authors give descriptions of characters or places through the written word. How does an artist convey this same information?

Organize your information and focus on each feature before moving onto the text – it is not ideal to discuss color and jump from line to then in the conclusion discuss color again. First summarize the overall appearance of the work of art – is this a painting? Does the artist use only dark colors? Why heavy brushstrokes? etc and then discuss details of the object – this specific animal is gray, the sky is missing a moon, etc. Again, it is best to be organized and focused in your writing – if you discuss the animals and then the individuals and go back to the animals you run the risk of making your writing unorganized and hard to read. It is also ideal to discuss the focal of the piece – what is in the center? What stands out the most in the piece or takes up most of the composition?

A stylistic approach can be described as an indicator of unique characteristics that analyzes and uses the formal elements (2-D: Line, color, value, shape and 3-D all of those and mass).The point of style is to see all the commonalities in a person’s works, such as the use of paint and brush strokes in Van Gogh’s work. Style can distinguish an artist’s work from others and within their own timeline, geographical regions, etc.

Methods & Theories To Consider:

Expressionism

Instructuralism

Postmodernism

Social Art History

Biographical Approach

Poststructuralism

Museum Studies

Visual Cultural Studies

Stylistic Analysis Example:

The following is a brief stylistic analysis of two Greek statues, an example of how style has changed because of the “essence of the age.” Over the years, sculptures of women started off as being plain and fully clothed with no distinct features, to the beautiful Venus/Aphrodite figures most people recognize today. In the mid-seventh century to the early fifth, life-sized standing marble statues of young women, often elaborately dress in gaily painted garments were created known as korai. The earliest korai is a Naxian women to Artemis. The statue wears a tight-fitted, belted peplos, giving the body a very plain look. The earliest korai wore the simpler Dorian peplos, which was a heavy woolen garment. From about 530, most wear a thinner, more elaborate, and brightly painted Ionic linen and himation. A largely contrasting Greek statue to the korai is the Venus de Milo. The Venus from head to toe is six feet seven inches tall. Her hips suggest that she has had several children. Though her body shows to be heavy, she still seems to almost be weightless. Viewing the Venus de Milo, she changes from side to side. From her right side she seems almost like a pillar and her leg bears most of the weight. She seems be firmly planted into the earth, and since she is looking at the left, her big features such as her waist define her. The Venus de Milo had a band around her right bicep. She had earrings that were brutally stolen, ripping her ears away. Venus was noted for loving necklaces, so it is very possibly she would have had one. It is also possible she had a tiara and bracelets. Venus was normally defined as “golden,” so her hair would have been painted. Two statues in the same region, have throughout history, changed in their style.

Compare and Contrast Essay

Most introductory art history classes will ask students to write a compare and contrast essay about two pieces – examples include comparing and contrasting a medieval to a renaissance painting. It is always best to start with smaller comparisons between the two works of art such as the medium of the piece. Then the comparison can include attention to detail so use of color, subject matter, or iconography. Do the same for contrasting the two pieces – start small. After the foundation is set move on to the analysis and what these comparisons or contrasting material mean – ‘what is the bigger picture here?’ Consider why one artist would wish to show the same subject matter in a different way, how, when, etc are all questions to ask in the compare and contrast essay. If during an exam it would be best to quickly outline the points to make before tackling writing the essay.

Compare and Contrast Example:

Stele of Hammurabi from Susa (modern Shush, Iran), ca. 1792 – 1750 BCE, Basalt, height of stele approx. 7’ height of relief 28’

Stele, relief sculpture, Art as propaganda – Hammurabi shows that his law code is approved by the gods, depiction of land in background, Hammurabi on the same place of importance as the god, etc.

Top of this stele shows the relief image of Hammurabi receiving the law code from Shamash, god of justice, Code of Babylonian social law, only two figures shown, different area and time period, etc.

Stele of Naram-sin , Sippar Found at Susa c. 2220 - 2184 bce. Limestone, height 6'6"

Stele, relief sculpture, Example of propaganda because the ruler (like the Stele of Hammurabi) shows his power through divine authority, Naramsin is the main character due to his large size, depiction of land in background, etc.

Akkadian art, made of limestone, the stele commemorates a victory of Naramsin, multiple figures are shown specifically soldiers, different area and time period, etc.

Iconography

Regardless of what essay approach you take in class it is absolutely necessary to understand how to analyze the iconography of a work of art and to incorporate into your paper. Iconography is defined as subject matter, what the image means. For example, why do things such as a small dog in a painting in early Northern Renaissance paintings represent sexuality? Additionally, how can an individual perhaps identify these motifs that keep coming up?

The following is a list of symbols and their meaning in Marriage a la Mode by William Hogarth (1743) that is a series of six paintings that show the story of marriage in Hogarth’s eyes.

- Man has pockets turned out symbolizing he has lost money and was recently in a fight by the state of his clothes.

- Lap dog shows loyalty but sniffs at woman’s hat in the husband’s pocket showing sexual exploits.

- Black dot on husband’s neck believed to be symbol of syphilis.

- Mantel full of ugly Chinese porcelain statues symbolizing that the couple has no class.

- Butler had to go pay bills, you can tell this by the distasteful look on his face and that his pockets are stuffed with bills and papers.

- Card game just finished up, women has directions to game under foot, shows her easily cheating nature.

- Paintings of saints line a wall of the background room, isolated from the living, shows the couple’s complete disregard to faith and religion.

- The dangers of sexual excess are underscored in the Hograth by placing Cupid among ruins, foreshadowing the inevitable ruin of the marriage.

- Eventually the series (other five paintings) shows that the woman has an affair, the men duel and die, the woman hangs herself and the father takes her ring off her finger symbolizing the one thing he could salvage from the marriage.

Art History

What this handout is about.

This handout discusses a few common assignments found in art history courses. To help you better understand those assignments, this handout highlights key strategies for approaching and analyzing visual materials.

Writing in art history

Evaluating and writing about visual material uses many of the same analytical skills that you have learned from other fields, such as history or literature. In art history, however, you will be asked to gather your evidence from close observations of objects or images. Beyond painting, photography, and sculpture, you may be asked to write about posters, illustrations, coins, and other materials.

Even though art historians study a wide range of materials, there are a few prevalent assignments that show up throughout the field. Some of these assignments (and the writing strategies used to tackle them) are also used in other disciplines. In fact, you may use some of the approaches below to write about visual sources in classics, anthropology, and religious studies, to name a few examples.

This handout describes three basic assignment types and explains how you might approach writing for your art history class.Your assignment prompt can often be an important step in understanding your course’s approach to visual materials and meeting its specific expectations. Start by reading the prompt carefully, and see our handout on understanding assignments for some tips and tricks.

Three types of assignments are discussed below:

- Visual analysis essays

- Comparison essays

- Research papers

1. Visual analysis essays

Visual analysis essays often consist of two components. First, they include a thorough description of the selected object or image based on your observations. This description will serve as your “evidence” moving forward. Second, they include an interpretation or argument that is built on and defended by this visual evidence.

Formal analysis is one of the primary ways to develop your observations. Performing a formal analysis requires describing the “formal” qualities of the object or image that you are describing (“formal” here means “related to the form of the image,” not “fancy” or “please, wear a tuxedo”). Formal elements include everything from the overall composition to the use of line, color, and shape. This process often involves careful observations and critical questions about what you see.

Pre-writing: observations and note-taking

To assist you in this process, the chart below categorizes some of the most common formal elements. It also provides a few questions to get you thinking.

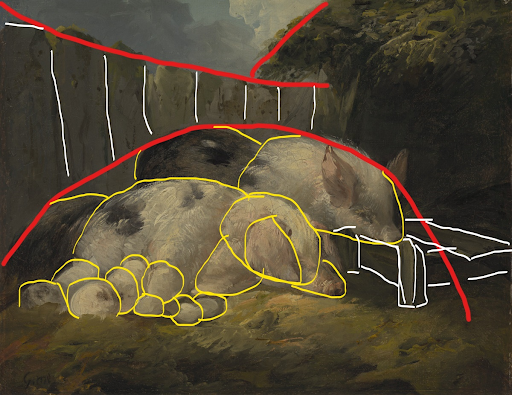

Let’s try this out with an example. You’ve been asked to write a formal analysis of the painting, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty , ca. 1800 (created in Britain and now in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond).

What do you notice when you see this image? First, you might observe that this is a painting. Next, you might ask yourself some of the following questions: what kind of paint was used, and what was it painted on? How has the artist applied the paint? What does the scene depict, and what kinds of figures (an art-historical term that generally refers to humans) or animals are present? What makes these animals similar or different? How are they arranged? What colors are used in this painting? Are there any colors that pop out or contrast with the others? What might the artist have been trying to accomplish by adding certain details?

What other questions come to mind while examining this work? What kinds of topics come up in class when you discuss paintings like this one? Consider using your class experiences as a model for your own description! This process can be lengthy, so expect to spend some time observing the artwork and brainstorming.

Here is an example of some of the notes one might take while viewing Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty :

Composition

- The animals, four pigs total, form a gently sloping mound in the center of the painting.

- The upward mound of animals contrasts with the downward curve of the wooden fence.

- The gentle light, coming from the upper-left corner, emphasizes the animals in the center. The rest of the scene is more dimly lit.

- The composition is asymmetrical but balanced. The fence is balanced by the bush on the right side of the painting, and the sow with piglets is balanced by the pig whose head rests in the trough.

- Throughout the composition, the colors are generally muted and rather limited. Yellows, greens, and pinks dominate the foreground, with dull browns and blues in the background.

- Cool colors appear in the background, and warm colors appear in the foreground, which makes the foreground more prominent.

- Large areas of white with occasional touches of soft pink focus attention on the pigs.

- The paint is applied very loosely, meaning the brushstrokes don’t describe objects with exact details but instead suggest them with broad gestures.

- The ground has few details and appears almost abstract.

- The piglets emerge from a series of broad, almost indistinct, circular strokes.

- The painting contrasts angular lines and rectangles (some vertical, some diagonal) with the circular forms of the pig.

- The negative space created from the intersection of the fence and the bush forms a wide, inverted triangle that points downward. The point directs viewers’ attention back to the pigs.

Because these observations can be difficult to notice by simply looking at a painting, art history instructors sometimes encourage students to sketch the work that they’re describing. The image below shows how a sketch can reveal important details about the composition and shapes.

Writing: developing an interpretation

Once you have your descriptive information ready, you can begin to think critically about what the information in your notes might imply. What are the effects of the formal elements? How do these elements influence your interpretation of the object?

Your interpretation does not need to be earth-shatteringly innovative, but it should put forward an argument with which someone else could reasonably disagree. In other words, you should work on developing a strong analytical thesis about the meaning, significance, or effect of the visual material that you’ve described. For more help in crafting a strong argument, see our Thesis Statements handout .

For example, based on the notes above, you might draft the following thesis statement:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the close proximity of the pigs to each other–evident in the way Morland has overlapped the pigs’ bodies and grouped them together into a gently sloping mound–and the soft atmosphere that surrounds them hints at the tranquility of their humble farm lives.

Or, you could make an argument about one specific formal element:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the sharp contrast between rectilinear, often vertical, shapes and circular masses focuses viewers’ attention on the pigs, who seem undisturbed by their enclosure.

Support your claims

Your thesis statement should be defended by directly referencing the formal elements of the artwork. Try writing with enough specificity that someone who has not seen the work could imagine what it looks like. If you are struggling to find a certain term, try using this online art dictionary: Tate’s Glossary of Art Terms .

Your body paragraphs should explain how the elements work together to create an overall effect. Avoid listing the elements. Instead, explain how they support your analysis.

As an example, the following body paragraph illustrates this process using Morland’s painting:

Morland achieves tranquility not only by grouping animals closely but also by using light and shadow carefully. Light streams into the foreground through an overcast sky, in effect dappling the pigs and the greenery that encircles them while cloaking much of the surrounding scene. Diffuse and soft, the light creates gentle gradations of tone across pigs’ bodies rather than sharp contrasts of highlights and shadows. By modulating the light in such subtle ways, Morland evokes a quiet, even contemplative mood that matches the restful faces of the napping pigs.

This example paragraph follows the 5-step process outlined in our handout on paragraphs . The paragraph begins by stating the main idea, in this case that the artist creates a tranquil scene through the use of light and shadow. The following two sentences provide evidence for that idea. Because art historians value sophisticated descriptions, these sentences include evocative verbs (e.g., “streams,” “dappling,” “encircles”) and adjectives (e.g., “overcast,” “diffuse,” “sharp”) to create a mental picture of the artwork in readers’ minds. The last sentence ties these observations together to make a larger point about the relationship between formal elements and subject matter.

There are usually different arguments that you could make by looking at the same image. You might even find a way to combine these statements!

Remember, however you interpret the visual material (for example, that the shapes draw viewers’ attention to the pigs), the interpretation needs to be logically supported by an observation (the contrast between rectangular and circular shapes). Once you have an argument, consider the significance of these statements. Why does it matter if this painting hints at the tranquility of farm life? Why might the artist have tried to achieve this effect? Briefly discussing why these arguments matter in your thesis can help readers understand the overall significance of your claims. This step may even lead you to delve deeper into recurring themes or topics from class.

Tread lightly

Avoid generalizing about art as a whole, and be cautious about making claims that sound like universal truths. If you find yourself about to say something like “across cultures, blue symbolizes despair,” pause to consider the statement. Would all people, everywhere, from the beginning of human history to the present agree? How do you know? If you find yourself stating that “art has meaning,” consider how you could explain what you see as the specific meaning of the artwork.

Double-check your prompt. Do you need secondary sources to write your paper? Most visual analysis essays in art history will not require secondary sources to write the paper. Rely instead on your close observation of the image or object to inform your analysis and use your knowledge from class to support your argument. Are you being asked to use the same methods to analyze objects as you would for paintings? Be sure to follow the approaches discussed in class.

Some classes may use “description,” “formal analysis” and “visual analysis” as synonyms, but others will not. Typically, a visual analysis essay may ask you to consider how form relates to the social, economic, or political context in which these visual materials were made or exhibited, whereas a formal analysis essay may ask you to make an argument solely about form itself. If your prompt does ask you to consider contextual aspects, and you don’t feel like you can address them based on knowledge from the course, consider reading the section on research papers for further guidance.

2. Comparison essays

Comparison essays often require you to follow the same general process outlined in the preceding sections. The primary difference, of course, is that they ask you to deal with more than one visual source. These assignments usually focus on how the formal elements of two artworks compare and contrast with each other. Resist the urge to turn the essay into a list of similarities and differences.

Comparison essays differ in another important way. Because they typically ask you to connect the visual materials in some way or to explain the significance of the comparison itself, they may require that you comment on the context in which the art was created or displayed.

For example, you might have been asked to write a comparative analysis of the painting discussed in the previous section, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty (ca. 1800), and an unknown Vicús artist’s Bottle in the Form of a Pig (ca. 200 BCE–600 CE). Both works are illustrated below.

You can begin this kind of essay with the same process of observations and note-taking outlined above for formal analysis essays. Consider using the same questions and categories to get yourself started.

Here are some questions you might ask:

- What techniques were used to create these objects?

- How does the use of color in these two works compare? Is it similar or different?

- What can you say about the composition of the sculpture? How does the artist treat certain formal elements, for example geometry? How do these elements compare to and contrast with those found in the painting?

- How do these works represent their subjects? Are they naturalistic or abstract? How do these artists create these effects? Why do these similarities and differences matter?

As our handout on comparing and contrasting suggests, you can organize these thoughts into a Venn diagram or a chart to help keep the answers to these questions distinct.

For example, some notes on these two artworks have been organized into a chart:

| Pigs and Piglets in a Sty | Both Art Works | Bottle in the Form of a Pig | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | Both depict a pig-like animal | ||

| Number | Focus is on two pigs and two piglets (4 animals total) | Focus is on one pig-like animal that makes up the majority of the vessel; vessel’s spout resembles a bird | |

| Colors | White and pink colors on the animals contrast with browns and blues in background | Both use contrasting colors to focus the viewer’s eye | Borders and other elements are defined by black and cream slip to highlight specific anatomical features |

| Setting | Trees, clouds, and wooden fence in background; animals and trough in foreground | No setting beyond the vessel itself | |

| Shape | Rectilinear, vertical shapes of trees and fence contrast with circular, more horizontal shapes of animals | Both use shape to link individual components to the whole composition | Composed of geometric shapes: the body is formed by a round cylinder; ears are concave pyramids, etc. |

As you determine points of comparison, think about the themes that you have discussed in class. You might consider whether the artworks display similar topics or themes. If both artworks include the same subject matter, for example, how does that similarity contribute to the significance of the comparison? How do these artworks relate to the periods or cultures in which they were produced, and what do those relationships suggest about the comparison? The answers to these questions can typically be informed by your knowledge from class lectures. How have your instructors framed the introduction of individual works in class? What aspects of society or culture have they emphasized to explain why specific formal elements were included or excluded? Once you answer your questions, you might notice that some observations are more important than others.

Writing: developing an interpretation that considers both sources

When drafting your thesis, go beyond simply stating your topic. A statement that says “these representations of pig-like animals have some similarities and differences” doesn’t tell your reader what you will argue in your essay.

To say more, based on the notes in the chart above, you might write the following thesis statement:

Although both artworks depict pig-like animals, they rely on different methods of representing the natural world.

Now you have a place to start. Next, you can say more about your analysis. Ask yourself: “so what?” Why does it matter that these two artworks depict pig-like animals? You might want to return to your class notes at this point. Why did your instructor have you analyze these two works in particular? How does the comparison relate to what you have already discussed in class? Remember, comparison essays will typically ask you to think beyond formal analysis.

While the comparison of a similar subject matter (pig-like animals) may influence your initial argument, you may find that other points of comparison (e.g., the context in which the objects were displayed) allow you to more fully address the matter of significance. Thinking about the comparison in this way, you can write a more complex thesis that answers the “so what?” question. If your class has discussed how artists use animals to comment on their social context, for example, you might explore the symbolic importance of these pig-like animals in nineteenth-century British culture and in first-millenium Vicús culture. What political, social, or religious meanings could these objects have generated? If you find yourself needing to do outside research, look over the final section on research papers below!

Supporting paragraphs

The rest of your comparison essay should address the points raised in your thesis in an organized manner. While you could try several approaches, the two most common organizational tactics are discussing the material “subject-by-subject” and “point-by-point.”

- Subject-by-subject: Organizing the body of the paper in this way involves writing everything that you want to say about Moreland’s painting first (in a series of paragraphs) before moving on to everything about the ceramic bottle (in a series of paragraphs). Using our example, after the introduction, you could include a paragraph that discusses the positioning of the animals in Moreland’s painting, another paragraph that describes the depiction of the pigs’ surroundings, and a third explaining the role of geometry in forming the animals. You would then follow this discussion with paragraphs focused on the same topics, in the same order, for the ancient South American vessel. You could then follow this discussion with a paragraph that synthesizes all of the information and explores the significance of the comparison.

- Point-by-point: This strategy, in contrast, involves discussing a single point of comparison or contrast for both objects at the same time. For example, in a single paragraph, you could examine the use of color in both of our examples. Your next paragraph could move on to the differences in the figures’ setting or background (or lack thereof).

As our use of “pig-like” in this section indicates, titles can be misleading. Many titles are assigned by curators and collectors, in some cases years after the object was produced. While the ceramic vessel is titled Bottle in the Form of a Pig , the date and location suggest it may depict a peccary, a pig-like species indigenous to Peru. As you gather information about your objects, think critically about things like titles and dates. Who assigned the title of the work? If it was someone other than the artist, why might they have given it that title? Don’t always take information like titles and dates at face value.

Be cautious about considering contextual elements not immediately apparent from viewing the objects themselves unless you are explicitly asked to do so (try referring back to the prompt or assignment description; it will often describe the expectation of outside research). You may be able to note that the artworks were created during different periods, in different places, with different functions. Even so, avoid making broad assumptions based on those observations. While commenting on these topics may only require some inference or notes from class, if your argument demands a large amount of outside research, you may be writing a different kind of paper. If so, check out the next section!

3. Research papers

Some assignments in art history ask you to do outside research (i.e., beyond both formal analysis and lecture materials). These writing assignments may ask you to contextualize the visual materials that you are discussing, or they may ask you to explore your material through certain theoretical approaches. More specifically, you may be asked to look at the object’s relationship to ideas about identity, politics, culture, and artistic production during the period in which the work was made or displayed. All of these factors require you to synthesize scholars’ arguments about the materials that you are analyzing. In many cases, you may find little to no research on your specific object. When facing this situation, consider how you can apply scholars’ insights about related materials and the period broadly to your object to form an argument. While we cannot cover all the possibilities here, we’ll highlight a few factors that your instructor may task you with investigating.

Iconography

Papers that ask you to consider iconography may require research on the symbolic role or significance of particular symbols (gestures, objects, etc.). For example, you may need to do some research to understand how pig-like animals are typically represented by the cultural group that made this bottle, the Vicús culture. For the same paper, you would likely research other symbols, notably the bird that forms part of the bottle’s handle, to understand how they relate to one another. This process may involve figuring out how these elements are presented in other artworks and what they mean more broadly.

Artistic style and stylistic period

You may also be asked to compare your object or painting to a particular stylistic category. To determine the typical traits of a style, you may need to hit the library. For example, which period style or stylistic trend does Moreland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty belong to? How well does the piece “fit” that particular style? Especially for works that depict the same or similar topics, how might their different styles affect your interpretation? Assignments that ask you to consider style as a factor may require that you do some research on larger historical or cultural trends that influenced the development of a particular style.

Provenance research asks you to find out about the “life” of the object itself. This research can include the circumstances surrounding the work’s production and its later ownership. For the two works discussed in this handout, you might research where these objects were originally displayed and how they ended up in the museum collections in which they now reside. What kind of argument could you develop with this information? For example, you might begin by considering that many bottles and jars resembling the Bottle in the Form of a Pig can be found in various collections of Pre-Columbian art around the world. Where do these objects originate? Do they come from the same community or region?

Patronage study

Prompts that ask you to discuss patronage might ask you to think about how, when, where, and why the patron (the person who commissions or buys the artwork or who supports the artist) acquired the object from the artist. The assignment may ask you to comment on the artist-patron relationship, how the work fit into a broader series of commissions, and why patrons chose particular artists or even particular subjects.

Additional resources

To look up recent articles, ask your librarian about the Art Index, RILA, BHA, and Avery Index. Check out www.lib.unc.edu/art/index.html for further information!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Adams, Laurie Schneider. 2003. Looking at Art . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Barnet, Sylvan. 2015. A Short Guide to Writing about Art , 11th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Tate Galleries. n.d. “Art Terms.” Accessed November 1, 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

ARTS - Herzberg: Writing Essays About Art

- Art History

- Current Artists and Events

- Local Art Venues

- Video and Image Resources

- Writing Essays About Art

- Citation Help

What is a Compare and Contrast Essay?

What is a compare / contrast essay.

In Art History and Appreciation, contrast / compare essays allow us to examine the features of two or more artworks.

- Comparison -- points out similarities in the two artworks

- Contrast -- points out the differences in the two artworks

Why would you want to write this type of essay?

- To inform your reader about characteristics of each art piece.

- To show a relationship between different works of art.

- To give your reader an insight into the process of artistic invention.

- Use your assignment sheet from your class to find specific characteristics that your professor wants you to compare.

How is Writing a Compare / Contrast Essay in Art History Different from Other Subjects?

You should use art vocabulary to describe your subjects..

- Find art terms in your textbook or an art glossary or dictionary

You should have an image of the works you are writing about in front of you while you are writing your essay.

- The images should be of high enough quality that you can see the small details of the works.

- You will use them when describing visual details of each art work.

Works of art are highly influenced by the culture, historical time period and movement in which they were created.

- You should gather information about these BEFORE you start writing your essay.

If you describe a characteristic of one piece of art, you must describe how the OTHER piece of art treats that characteristic.

Example: You are comparing a Greek amphora with a sculpture from the Tang Dynasty in China.

If you point out that the color palette of the amphora is limited to black, white and red, you must also write about the colors used in the horse sculpture.

Organizing Your Essay

Thesis statement.

The thesis for a comparison/contrast essay will present the subjects under consideration and indicate whether the focus will be on their similarities, on their differences, or both.

Thesis example using the amphora and horse sculpture -- Differences:

While they are both made from clay, the Greek amphora and the Tang Dynasty horse served completely different functions in their respective cultures.

Thesis example -- Similarities:

Ancient Greek and Tang Dynasty ceramics have more in common than most people realize.

Thesis example -- Both:

The Greek amphora and the Tang Dynasty horse were used in different ways in different parts of the world, but they have similarities that may not be apparent to the casual viewer.

Visualizing a Compare & Contrast Essay:

Introduction (1-2 paragraphs) .

- Creates interest in your essay

- Introduces the two art works that you will be comparing.

- States your thesis, which mentions the art works you are considering and may indicate whether the focus will be on similarities, differences, or both.

Body paragraphs

- Make and explain a point about the first subject and then about the second subject

- Example: While both superheroes fight crime, their motivation is vastly different. Superman is an idealist, who fights for justice …… while Batman is out for vengeance.

Conclusion (1-2 paragraphs)

- Provides a satisfying finish

- Leaves your reader with a strong final impression.

Downloadable Essay Guide

- How to Write a Compare and Contrast Essay in Art History Downloadable version of the description on this LibGuide.

Questions to Ask Yourself After You Have Finished Your Essay

- Are all the important points of comparison or contrast included and explained in enough detail?

- Have you addressed all points that your professor specified in your assignment?

- Do you use transitions to connect your arguments so that your essay flows into a coherent whole, rather than just a random collection of statements?

- Do your arguments support your thesis statement?

Art Terminology

- British National Gallery: Art Glossary Includes entries on artists, art movements, techniques, etc.

Lee College Writing Center

Writing Center tutors can help you with any writing assignment for any class from the time you receive the assignment instructions until you turn it in, including:

- Brainstorming ideas

- MLA / APA formats

- Grammar and paragraph unity

- Thesis statements

- Second set of eyes before turning in

Contact a tutor:

- Phone: 281-425-6534

- Email: w [email protected]

- Schedule a web appointment: https://lee.mywconline.com/

Other Compare / Contrast Writing Resources

- Southwestern University Guide for Writing About Art This easy to follow guide explains the basic of writing an art history paper.

- Purdue Online Writing Center: writing essays in art history Describes how to write an art history Compare and Contrast paper.

- Stanford University: a brief guide to writing in art history See page 24 of this document for an explanation of how to write a compare and contrast essay in art history.

- Duke University: writing about paintings Downloadable handout provides an overview of areas you should cover when you write about paintings, including a list of questions your essay should answer.

- << Previous: Video and Image Resources

- Next: Citation Help >>

- Last Updated: May 14, 2024 8:50 AM

- URL: https://lee.libguides.com/Arts_Herzberg

How to Write an Art Comparison Essay

Jared lewis, 25 jun 2018.

Writing an art comparison essay can be a difficult task for the novice art student. Students of art or art history often assume that any interpretation is as good as another, but in reality, to adequately interpret a work of art and then compare it to another, you will need to learn a little about the artist and the historical context of the composition.

Research the historical context of each piece of art. In order to adequately understand any work of art you must understand the circumstances under which it was produced. Artists are considered cultural innovators and often have an idea or truth they are trying to convey with any given composition or group of compositions. You have to first understand the artist as a person before you can adequately understand the meaning of his or her work. In order to understand the artist as a person you will also need to understand the time in which they lived. Picking up a good art history or humanities textbook will help you get started understanding the context.

Find the similarities and differences. Once you have placed each work within the proper context and before you actually begin to write your essay, sit down with a sheet of paper and a pen or pencil and write down the similarities and differences in each work. Questions to consider are the historical, political, philosophical, and religious differences of the time in which each work was composed. What do each of these works say about these issues? Do the works contain any symbolism? If so, how do the symbols differ and how are they similar? What do the symbols tell the observer about each composition?

Consider the medium through which the piece of art was created. Is it a painting or sculpture? Is the art representational or abstract? Is there a technique or style used that tells the observer something about the meaning of the composition? Who or what are the subjects of the work? The questions you can ask regarding any particular work of art are actually unlimited, but should always include some of these basic questions.

Compose your essay. Once you have analyzed each key piece of art you should develop some type of thesis statement related to that analysis. For instance, a comparison of any of Jackson Pollack's works with Van Gogh's "Starry Night" might yield a thesis statement indicating that both artists expressed themselves similarly by painting in a manner that revealed their inner emotions. Van Gogh was known to cake the paint onto the canvas and create a visible texture that was reminiscent of his inner torment while Pollack's abstract art was created by slopping paint onto large canvases, often in a drunken rage. You can then compare and contrast the elements of each composition to reveal how these artists methods were similar. The key to writing a good comparison and contrast essay is to be as clear and concise as possible, but also to be as detailed as possible regarding each element of the compositions.

Revise your work. If you are submitting your work for a grade you should take the time to reread and revise your essay before turning it in. Even the best writers rarely get their work exactly right on the first try. Have someone else proofread and offer suggestions for revision if possible. It is generally much easier for someone else to spot clarity issues and point them out than it is for you to do it yourself. Getting a little help from a friend, family member, or colleague is a great way to strengthen your writing and increase your chances of getting a positive response from the reader.

- 1 Academy of Art University: Compare/Contrast Art History Essay

About the Author

Jared Lewis is a professor of history, philosophy and the humanities. He has taught various courses in these fields since 2001. A former licensed financial adviser, he now works as a writer and has published numerous articles on education and business. He holds a bachelor's degree in history, a master's degree in theology and has completed doctoral work in American history.

Related Articles

How to Explain Abstract Art to Children

Michelangelo Art Lesson Ideas for Kids

How to Teach 8 to 12 Year Old Art

How to Write About Appreciation of Artwork

How to Do an In-Text Citation for Art in MLA

How to Answer Compare and Contrast Questions

A Grading Rubric for Art in Higher Education

Types of Art Degrees

Arabesques in Islamic Art

How to Write an Art Exhibition Paper

How To Teach Art to Kids

Fiction Explication Vs. Analysis

How to Teach Poetry in 3rd Grade

How to Write a Conclusion for a Rhetorical Analysis

How to Analyze Poems in College

The Differences Between Reaction Paper & Reflection...

How to Write a Descriptive Essay on a Sculpture

How to Write a Historiographical Essay

Advanced Writing Techniques

How to Write a Comic Book

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

The Writing Place

Resources – how to write an art history paper, introduction to the topic.

There are many different types of assignments you might be asked to do in an art history class. The most common are a formal analysis and a stylistic analysis. Stylistic analyses often involve offering a comparison between two different works. One of the challenges of art history writing is that it requires a vocabulary to describe what you see when you look at a painting, drawing, sculpture or other media. This checklist is designed to explore questions that will help you write these types of art history papers.

Features of An Art History Analysis Paper

Features of a formal analysis paper.

This type of paper involves looking at compositional elements of an object such as color, line, medium, scale, and texture. The goal of this kind of assignment it to demonstrate how these elements work together to produce the whole art object. When writing a formal analysis, ask yourself:

- What is the first element of the work that the audience’s eye captures?

- What materials were used to create the object?

- What colors and textures did the artist employ?

- How do these function together to give the object its overall aesthetic look?

Tips on Formal Analysis

- Describe the piece as if your audience has not seen it.

- Be detailed.

- The primary focus should be on description rather than interpretation.

Features of a Stylistic / Comparative Analysis

Similar to a formal analysis, a stylistic analysis asks you to discuss a work in relation to its stylistic period (Impressionism, Fauvism, High Renaissance, etc.). These papers often involve a comparative element (such as comparing a statue from Early Antiquity to Late Antiquity). When writing a stylistic analysis, ask yourself:

- How does this work fit the style of its historical period? How does it depart from the typical style?

- What is the social and historical context of the work? When was it completed?

- Who was the artist? Who commissioned it? What does it depict?

- How is this work different from other works of the same subject matter?

- How have the conventions (formal elements) for this type of work changed over time?

Tips for Stylistic and Comparative Analysis

- In a comparison, make a list of similarities and differences between the two works. Try to establish what changes in the art world may account for the differences.

- Integrate discussions of formal elements into your stylistic analysis.

- This type of paper can involve more interpretation than a basic formal analysis.

- Focus on context and larger trends in art history.

A Quick Practice Exercise...

Practice - what is wrong with these sentences.

The key to writing a good art history paper involves relating the formal elements of a piece to its historical context. Can you spot the errors in these sentences? What would make the sentences better?

- “Courbet’s The Stone Breakers is a good painting because he uses texture.”

- “Duchamp’s work is in the Dada style while Dali’s is Surrealist.”

- “Pope Julius II commissioned the work.”

- “Gauguin uses color to draw in the viewer’s eye.”

Answers for Practice Sentences

- Better: “Courbet’s The Stone Breakers is a radical painting because the artist used a palette knife to create a rough texture on the surface.”

- Better: “The use of everyday objects in Duchamp’s work reflects the Dada style while Dali’s incorporation of absurd images into his work demonstrates a Surrealist style.”

- Better: “In 1505, Pope Julius II commissioned the sculpture for his tomb.”

- Better: “The first element a viewer notices is the bold blue of the sky in Gauguin’s painting.”

Adapted by Ann Bruton, with the help of Isaac Alpert, From:

The Writing Center at UNC Handouts ( http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/art-history/ )

The Writing Center at Hamilton College ( http://www.hamilton.edu/writing/writing-resources/writing-an-art-history-paper )

Click here to return to the “Writing Place Resources” main page.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.5: How to Compare and Contrast Art

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 46129

- Deborah Gustlin & Zoe Gustlin

- Evergreen Valley College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Comparing modern paintings and historic paintings brings an understanding of how the past influences the present. Learning the elements of art, design, and art methods will help you communicate and write with a new language to compare and contrast art. In this textbook, we will be comparing and contrasting ordinary images of horses, figures, sunflowers, and dots. Like a new language, it becomes more familiar the more the terms used in written descriptions. Looking at art is the foundation of learning how to write descriptive essays. The longer you look, the more information you begin to see, like the brush marks. Asking yourself questions about the brush marks can help you define the type of art you are looking at: Impressionism uses significant broad-brush marks with visible slabs of paint. While Renaissance artists used oil paint with almost hidden brush marks giving a life-like look to the painting. These observations will help you decide what period of art painting can belong in when you do not know the answer.

Comparing Horses

The two paintings, Relay Hunting (1.9) and Foundation Sire (1.10) were created 170 years apart yet are as realistic as photographs taken yesterday. Similar instances, the horses predominantly face away from the viewer displaying the sturdy hind legs and taut muscles. The shining sun marks their coats, reflecting highlights and emphasizing the muscle structure of the animals. Both artists realistically depict the horses causing the viewer to take a second look at the exquisite details of the horses and the surroundings.

In realistic paintings, both artists focused on detail based upon their study of horse anatomy. Rosa Bonheur, who painted the three horses in Relay Hunting (1.9), actually went to meat processing plants and studied the anatomy of the horses while she dissected the animals. Most artists study human anatomy as part of their education. Understanding the body's muscle and bone structure benefits the artists' ability to draw realistic people and animals.

1.13 Study of Horses , Leonardo

The representation of horses throughout human time began on the cave wall, Image of Horse (1.11). We see horses immortalized in bronze statues, captured on film, or drawn in Study of Horses (1.13). Painted in Blue Horses (1.14), etched in Knight, Death and the Devil (1.12), and colored. Horses have been a mode of transportation for thousands of years, and the equine image has been traditional portraiture throughout the ages. These pictures of different types of horses demonstrate they can be drawn or painted in many types of styles. The details in the etched Knight, Death, and the Devil (1.12) establishes the artist as a detail orientated person as opposed to the Blue Horses (1.14), which has a looser painting style and bolder colors.

Comparing Figures

At first glance, The Birth of Venus (1.15) and Rara Avis 19 (1.16) look completely different from each other, or are they? Let us look closer at these two figures—what is the one object in both paintings that is similar? The woman in the center! Both poses are similar, expressionless except what the viewer reads into it, and they display no movement, a very static pose with elongated legs and feet. Neither one of the artists give any weight to the body or use any type of deep perspective space. Both figures have an impossible pose, the shifting of weight over one hip. They both appear to be emerging from the water as if being born from the sea.

They are both colorful and have the impression of a background; land, sea, and trees. However, these two paintings are over 500 years apart, the Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli in 1486 and Rara Avis 19 by Jylian Gustlin in 2014. Botticelli painted in oils on canvas, and his Venus is aloof and uninterested in her surroundings. Gustlin works in acrylic and oil paints on board, using the effects of layers to achieve her distinct and intricate paintings. The figures in the landscape frequently show a moody and brooding figure, yet at the same time, depicting a sense of future. One figure set in a literal translation and the other in a modern view, yet each one escapes from reality.

Comparing Sunflowers

These two pieces of art display the gorgeous sunflower at the height of its flowering. The yellow petals open up towards the sunshine, offering seeds to passing birds. The hint of brown color on the leaves tells the viewer that the fall weather is on its way. These two art pieces are about 140 years apart, one is in paint, and the other is painted fabric. The Sunflowers (1.17) in the vase is by Vincent Van Gogh in 1887, and the sunflower quilt (1.18) is by an unknown quilter, 2004.

The two pieces have many similar components, for example, the colors of the sunflowers are yellow, brown seed pods in the centers, both pictures fill the space, and both painted. The differences are more significant because the quilted sunflowers highly contrast against the dark brown fabric; the flowers in the vase are against a pale blue background. The quilt shows flowers arranged in space not anchored to stems or in a vase, as seen in the painting.

The painting process is also different. Van Gogh painted his sunflowers on canvas with oil paints. The painted quilt fabric became the palette for the sunflowers with mostly yellows, with browns, greens, and oranges in a random array of colors for highlights, cut into individual leaves, and arranged on the background fabric. Both pieces are similar works of art created in different periods with different materials.

Comparing Dots

Dots or points are single primary forms in art. In art, dots can be one or many thousands of dots abstracted into images we may or may not recognize. The dots can be far apart or close together, different colors, monochromatic, or one color. All drawings begin with a single dot from the point of the pencil, and as the pencil moves, it becomes a continuous line of dots, thereby making the dot one of the essential elements in art.

Dots become the focal point of the art, and space in-between the dots are as crucial as the dot itself. The dot can cause tension or harmony depending on the color, size, and how close the dot is to another dot. As dots placed closer together, they start to become an object, a recognizable form.

Yayoi Kusama (born 1929) is considered the 'Princess of Polka Dots' using large distinct polka dots in her two sculptures Flowers (1.19) and Life is the Heart of a Rainbow (1.20). They are red and white polka dots surrounding the trees or the entire room. The polka dots are distinctly circles, especially in the room, as they are far apart and only in two contrasting colors. The red wrapped trees with white polka dots are closer together but still distinct in various sizes in the high contrast. The dots are not touching, and the negative space between them is about the same size throughout.

George Seurat developed a technique of painting with tiny colored dots called Pointillism as he when he branched out from Impressionism. Pointillism relies on small dots of color that blend in the viewer's minds creating a large scene. Up close, each colored dot and brush mark are visible; however, when the viewer steps back several feet, the viewer is surprised with a lifelike painting. The large-scale piece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1.21), transformed art at the turn of the 20th century and inspired artists to work with dots.

The three paintings are all created from dots, small dots, large dots, colored dots on the canvas, on walls, suspended from the ceiling, or suspended in space. The size and color of the dot do matter and can give the viewer a completely different experience.

Art is everywhere you look, everything you wear, and art is beauty. Just look around....

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Department of Art History

Comparativism in Art History

Jas' Elsner

From the publisher :

Featuring some of the major voices in the world of art history, this volume explores the methodological aspects of comparison in the historiography of the discipline. The chapters assess the strengths and weaknesses of comparative practice in the history of art, and consider the larger issue of the place of comparative in how art history may develop in the future. The contributors represent a comprehensive range of period and geographic command from antiquity to modernity, from China and Islam to Europe, from various forms of art history to archaeology, anthropology and material culture studies. Art history is less a single discipline than a series of divergent scholarly fields – in very different historical, geographic and cultural contexts – but all with a visual emphasis on the close examination of objects. These fields focus on different, often incompatible temporal and cultural contexts, yet nonetheless they regard themselves as one coherent discipline – namely the history of art. There are substantive problems in how the sub-fields within the broad-brush generalization called 'art history' can speak coherently to each other. These are more urgent since the shift from an art history centered on the western tradition to one that is consciously global.

Publications

Charles Ray: Adam and Eve

Seeing Race Before Race (with Noémie Ndiaye)

Unseen Art: Making, Vision, and Power in Ancient Mesoamerica

Houses to Die In and Other Essays on Art

Divine Inspiration in Byzantium: Notions of Authenticity in Art and Theology.

Radical Form: Modernist Abstraction in South America

Building with Paper. The Materiality of Renaissance Architectural Drawings , eds. D. Donetti and C. Rachele

The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China (with Orianna Cacchione)

Bisa Butler: Portraits

Francesco da Sangallo e l'identità dell'architettura toscana

“Introduction: Inventing the Nova Reperta,” in Renaissance Invention: Stradanus’s Nova Reperta

First Class: Teaching Chinese Art History at Harvard University and the University of Chicago

Vessels: The Object as Container

A Forest of Symbols: Art, Science, and Truth in the Long Nineteenth Century

Art & Archaeology of the Greek World: A New History, c. 2500–c. 150 BCE

Conditions of Visibility

Pindar, Song, and Space: Towards a Lyric Archaeology

Among Others: Blackness at MoMA

A Companion to Modern and Contemporary Latin American and Latino Art

To Describe a Life: Notes from the Intersection of Art and Race Terror

Architecture and Dystopia

Il'ia i Emiliia Kabakovy

Ellsworth Kelly, Color Panels for a Large Wall

On Art: Ilya Kabakov

Scale & the Incas

Art in Chicago: A History from the Fire to Now

Giuliano da Sangallo: Disegni degli Uffizi

Memory in Motion. Archives, Technology and the Social

The Ark of Civilization

The Poetics of Late Latin Literature

The New World in Early Modern Italy, 1492-1750 (with Elizabeth Horodowich), Cambridge University Press, 2017

1971: A Year in the Life of Color

Ugliness: The Non-Beautiful in Art and Theory

The Autobiography of Video. The Life and Times of a Memory Technology

Zooming In: Histories of Photography in China

The Noisy Renaissance: Sound, Architecture, and Florentine Urban Life

Un/Translatables: New Maps for Germanic Literatures

Art History and Emergency

Imagining the Americas in Medici Florence

Poetry and the Thought of Song in Nineteenth-Century Britain

Image Science: Iconology, Visual Culture, and Media Aesthetics

Antiquity, Theatre, and the Painting of Henry Fuseli

The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs

«Di molte figure adornato»: L’Orlando furioso nei cicli pittorici fra Cinque e Seicento. Milano: Officina Libraria, 2015.

Making Modern Japanese-Style Painting: Kano Hogai and the Search for Images

Aesthetics of Ugliness: A Critical Edition

The Murals of Cacaxtla: The Power of Painting in Ancient Central Mexico

The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo

En Guerre: French Illustrators and World War I

Contemporary Chinese Art

Building a Sacred Mountain: The Buddhist Architecture of China's Mount Wutai

Raoul Hausmann et Les Avant-Gardes

Italian Master Drawings from the Princeton University Art Museum (Laura Giles and Claire Van Cleave), Yale University Press, 2014

Art and Rhetoric in Roman Culture,

Kunst und Archäologie der griechischen Welt: Von den Anfängen bis zum Hellenismus

The Spectacle of the Late Maya Court: Reflections on the Murals of Bonampak

Occupy: Three Inquiries in Disobedience

The Emergence of the Classical Style in Greek Sculpture

Sabine Moritz: Limbo 2013

Capital Culture : J. Carter Brown, the National Gallery of Art, and the Reinvention of the Museum Experience

Fugitive Objects: Sculpture and Literature in the German Nineteenth Century

Seeing Through Race

Awash in Color: French and Japanese Prints

Seeing Madness, Insanity, Media, and Visual Culture

A Story of Ruins: Presence and Absence in Chinese Art and Visual Culture

Art & Archaeology of the Greek World: A New History, c. 2500 - c. 150 BCE

Vision and Communism

Translating Truth: Ambitious Images and Religious Knowledge in Late Medieval France and England

Life, Death and Representation: Some New Work on Roman Sarcophagi

Cloning Terror: the War of Images 9/11 to the Present

A Field Guide to a New Metafield: Bridging the Humanities-Neurosciences Divide

Saints: Faith at the Borders

Éfficacité/Efficacity: How to Do Things with Words and Images?

Wonder, Image, & Cosmos in Medieval Islam

Bild und Text im Mittelalter (Sensus, 2)

Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents

Critical Terms for Media Studies

The Experimental Group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceptualism, Soviet Avant-Gardes

Reinventing the Past: Archaism and Antiquarianism in Chinese Art and Visual Culture

Gerhard Richter: Early Work 1951-1972

Blinky Palermo: Abstraction of an Era

Making History: Wu Hung on Contemporary Art

Elective Affinities: Testing Word and Image Relationships

Veiled Brightness: A History of Ancient Maya Color

Looking and Listening in 19th Century France (With Anne Leonard)

The Chicagoan: A Lost Magazine of the Jazz Age

Poetry and the Pre-Raphaelite Arts: William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti

The Writing of Modern Life: the Etching Revival in France, Britain, and the U.S., 1850-1940

The Late Derrida

How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness

Echo Objects: The Cognitive Work of Images

Severan Culture

Roman Eyes: Visuality and Subjectivity in Art and Text

On the Style Site: Art, Sociality and Media Culture

What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images

Edward Said: Continuing the Conversation

Remaking Beijing: Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space

Neo Rauch: Renegaten

Die Illustrierten Homilien des Johannes Chrysostomos in Byzanz

Chicago Apartments: A Century of Lakefront Luxury

Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties

Kara Walker: Narratives of a Negress

The Name of the Game: Ray Johnson's Postal Performance

Style and Politics in Athenian Vase Painting: The Craft of Democracy, ca. 530-460 B.C.E.

Landscape and Power

Confronting Identities in German Art: Myths, Reactions, Reflections

Pious Journeys: Christian Devotional Art and Practice in the Later Middle Ages and Renaissance

Stress and Resilience: The Social Context of Reproduction in Central Harlem

Joseph Beuys

The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity

Exhibiting Experimental Art in China

Wols Photographs

Building Lives: Constructing Rites and Passages;

Legends in Limestone: Lazarus, Gislebertus, and the Cathedral of Autun

Looking to Learn: Visual Pedagogy at the University of Chicago

Visual Analogy: Consciousness as the Art of Connecting

The Last Dinosaur Book: The Life and Times of a Cultural Icon

Embodying Ambiguity: Androgyny and Aesthetics from Winckelmann to Keller

Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph: The Art of the Roman Empire A.D. 100-450

Rural Scenes and National Representation, Britain 1815-1850

The Double Screen: Medium and Representation in Chinese Painting

The Art of Giovanni Antonio da Pordenone: Between Dialect and Language Volume II

The Art of Giovanni Antonio da Pordenone: Between Dialect and Language Volume I

Pissarro, Neo-Impressionism, and the Spaces of the Avant-Garde

Good Looking: Essays on the Virtue of Images

Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation

Monumentality in Early Chinese Art and Architecture

Pilgrimage Past and Present: Sacred Travel and Sacred Space in the World Religions

Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity

Artful Science: Enlightenment, Entertainment and the Eclipse of Visual Education

D.W. Griffith and the Origins of American Narrative Film

In the Theater of Criminal Justice: The Palais De Justice in Second Empire Paris

Art and the Public Sphere

Cultural Excursions: Marketing Appetites and Cultural Tastes in Modern America

The Wu Liang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art

Kilowatts and Crisis: Hydroelectric Power and Social Dislocation in Eastern Panama

The Woman Question: Society and Literature in Britain and America, 1837-1883

Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology

Hildegard Auer: A Yearning for Art

Munch: His Life and Work

Ruskin and the Art of the Beholder

On Narrative

The Language of Images

Blake's Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry

Humbug: The Art of P. T. Barnum

The Artist in American Society: The Formative Years, 1790-1860

Body Criticism: Imaging the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine

Meiji Modern: Fifty Years of New Japan

AP Art History

Learn all about the course and exam. Already enrolled? Join your class in My AP.

Not a Student?

Go to AP Central for resources for teachers, administrators, and coordinators.

About the Exam

The AP Art History Exam will test your understanding of the art historical concepts covered in the course units, as well as your ability to analyze and compare works of art and place them in historical context.

Mon, May 6, 2024

12 PM Local

AP Art History Exam

This is the regularly scheduled date for the AP Art History Exam.

Exam Components

Section 1: multiple choice.

80 questions 50% of Score

There are two types of multiple-choice questions on the exam:

- Sets of 2-3 questions, with each set based on color images of works of art.

- Individual questions, some of which are based on color images of works of art.

The multiple-choice section includes images of works of art both in and beyond the image set.

You’ll be asked to:

- Analyze visual and contextual elements of works of art and link them to a larger artistic tradition

- Compare 2 or more works

- Attribute works of art beyond the image set

- Analyze art historical interpretations

Section 2: Free Response

6 questions 50% of Score

There are six free-response questions on the exam:

- Question 1: Long Essay–Comparison will ask you to compare a required work of art and another of your choosing and explain the significance of the similarities and differences between those works, citing evidence to support their claim.

- Question 2: Long Essay–Visual/Contextual Analysis will ask you to select and identify a work of art and make assertions about it based on evidence.

- Question 3: Short Essay–Visual Analysis will ask you to describe a work of art beyond the image set and connect it to an artistic tradition, style, or practice.

- Question 4: Short Essay–Contextual Analysis will ask you to describe contextual influences of a work of art in the image set and explain how context can influence artistic decisions or affect the meaning of a work of art.

- Question 5: Short Essay–Attribution will ask you to attribute a work of art beyond the image set to a particular artist, culture, or style, and justify your assertions with evidence.

- Question 6: Short Essay–Continuity and Change will ask you to analyze the relationship between a provided work of art and a related artistic tradition, style, or practice.

- Questions 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6 will include images of works of art.

Exam Essentials

Exam preparation, ap classroom resources.

Once you join your AP class section online, you’ll be able to access AP Daily videos, any assignments from your teacher, and your assignment results in AP Classroom. Sign in to access them.

- Go to AP Classroom

Free-Response Questions and Scoring Information

Go to the Exam Questions and Scoring Information section of the AP Art History exam page on AP Central to review the latest released free-response questions and scoring information.

Past Exam Free-Response Questions and Scoring Information

Go to AP Central to review free-response questions and scoring information from past years.

AP Art History Course and Exam Description

This is the core document for the course. It clearly lays out the course content and describes the exam and AP Program in general.

Services for Students with Disabilities

Students with documented disabilities may be eligible for accommodations for the through-course assessment and the end-of-course exam. If you’re using assistive technology and need help accessing the PDFs in this section in another format, contact Services for Students with Disabilities at 212-713-8333 or by email at [email protected] . For information about taking AP Exams, or other College Board assessments, with accommodations, visit the Services for Students with Disabilities website.

Credit and Placement

Search AP Credit Policies

Find colleges that grant credit and/or placement for AP Exam scores in this and other AP courses.

Additional Information

- LibGuides

- A-Z List

- Help

Art Research Guide

- Art Research

- Art Journals & Guides

- Art in South Florida

- Academic Research & Paper Writing

- Visual, Critical Thinking, & Cultural Literacies

- APA Art Citations

- Chicago Art Citations

- Citing Images on the Web & Social Media

- MLA Art Citations

Art and Architecture Thesaurus Browser

- Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus This vocabulary database, developed by the Getty Research Institute, provides definitions, related terms, alternate forms of speech, synonyms and spelling variants.

- Methods & Theories

- Compare & Contrast

Art History Analysis – Formal Analysis and Stylistic Analysis

Typically in an art history class the main essay students will need to write for a final paper or for an exam is a formal or stylistic analysis.

A formal analysis is just what it sounds like – you need to analyze the form of the artwork. This includes the individual design elements – composition, color, line, texture, scale, contrast, etc. Questions to consider in a formal analysis is how do all these elements come together to create this work of art? Think of formal analysis in relation to literature – authors give descriptions of characters or places through the written word. How does an artist convey this same information?

Organize your information and focus on each feature before moving onto the text – it is not ideal to discuss color and jump from line to then in the conclusion discuss color again. First summarize the overall appearance of the work of art – is this a painting? Does the artist use only dark colors? Why heavy brushstrokes? etc and then discuss details of the object – this specific animal is gray, the sky is missing a moon , etc. Again, it is best to be organized and focused in your writing – if you discuss the animals and then the individuals and go back to the animals you run the risk of making your writing unorganized and hard to read. It is also ideal to discuss the focal of the piece – what is in the center? What stands out the most in the piece or takes up most of the composition?

A stylistic approach can be described as an indicator of unique characteristics that analyzes and uses the formal elements (2-D: Line, color, value, shape and 3-D all of those and mass).The point of style is to see all the commonalities in a person’s works, such as the use of paint and brush strokes in Van Gogh’s work. Style can distinguish an artist’s work from others and within their own timeline, geographical regions, etc.

Methods & Theories To Consider:

Expressionism

Instructuralism

Postmodernism

Social Art History

Biographical Approach

Poststructuralism

Museum Studies

Visual Cultural Studies

Stylistic Analysis Example:

The following is a brief stylistic analysis of two Greek statues, an example of how style has changed because of the “essence of the age.” Over the years, sculptures of women started off as being plain and fully clothed with no distinct features, to the beautiful Venus/Aphrodite figures most people recognize today. In the mid-seventh century to the early fifth, life-sized standing marble statues of young women, often elaborately dress in gaily painted garments were created known as korai. The earliest korai is a Naxian women to Artemis. The statue wears a tight-fitted, belted peplos, giving the body a very plain look. The earliest korai wore the simpler Dorian peplos, which was a heavy woolen garment. From about 530, most wear a thinner, more elaborate, and brightly painted Ionic linen and himation. A largely contrasting Greek statue to the korai is the Venus de Milo. The Venus from head to toe is six feet seven inches tall. Her hips suggest that she has had several children. Though her body shows to be heavy, she still seems to almost be weightless. Viewing the Venus de Milo, she changes from side to side. From her right side she seems almost like a pillar and her leg bears most of the weight. She seems be firmly planted into the earth, and since she is looking at the left, her big features such as her waist define her. The Venus de Milo had a band around her right bicep. She had earrings that were brutally stolen, ripping her ears away. Venus was noted for loving necklaces, so it is very possibly she would have had one. It is also possible she had a tiara and bracelets. Venus was normally defined as “golden,” so her hair would have been painted. Two statues in the same region, have throughout history, changed in their style.

Compare and Contrast Essay

Most introductory art history classes will ask students to write a compare and contrast essay about two pieces – examples include comparing and contrasting a medieval to a renaissance painting. It is always best to start with smaller comparisons between the two works of art such as the medium of the piece. Then the comparison can include attention to detail so use of color, subject matter, or iconography. Do the same for contrasting the two pieces – start small. After the foundation is set move on to the analysis and what these comparisons or contrasting material mean – ‘what is the bigger picture here?’ Consider why one artist would wish to show the same subject matter in a different way, how, when, etc are all questions to ask in the compare and contrast essay. If during an exam it would be best to quickly outline the points to make before tackling writing the essay.

Compare and Contrast Example:

Stele of Hammurabi from Susa (modern Shush, Iran), ca. 1792 – 1750 BCE, Basalt, height of stele approx. 7’ height of relief 28’

Stele, relief sculpture, Art as propaganda – Hammurabi shows that his law code is approved by the gods, depiction of land in background , Hammurabi on the same place of importance as the god, etc.