- Countries and Their Cultures

- Culture of Uzbekistan

Culture Name

Alternative names.

Uzbeq, Ozbek

Orientation

Identification. Uzbeks likely take their name from a khan. A leader of the Golden Horde in the fourteenth century was named Uzbek, though he did not rule over the people who would share his name.

Modern Uzbeks hail not only from the Turkic-Mongol nomads who first claimed the name, but also from other Turkic and Persian peoples living inside the country's borders. The Soviets, in an effort to divide the Turkic people into more easily governable subdivisions, labeled Turks, Tajiks, Sarts, Qipchaqs, Khojas, and others as Uzbek, doubling the size of the ethnicity to four million in 1924.

Today the government is strengthening the Uzbek group identity, to prevent the splintering seen in other multiethnic states. Some people have assimilated with seemingly little concern. Many Tajiks consider themselves Uzbek, though they retain the Tajik language; this may be because they have long shared an urban lifestyle, which was more of a bond than ethnic labels. Others have been more resistant to Uzbekization. Many Qipchaqs eschew intermarriage, live a nomadic lifestyle, and identify more closely with the Kyrgyz who live across the border from them. The Khojas also avoid intermarriage, and despite speaking several languages, have retained a sense of unity.

The Karakalpaks, who live in the desert south of the Aral Sea, have a separate language and tradition more akin to Kazakh than Uzbek. Under the Soviet Union, theirs was a separate republic, and it remains autonomous.

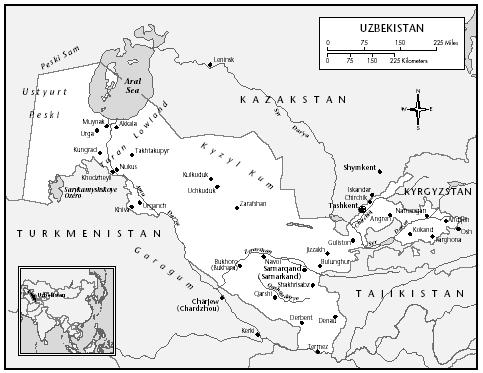

Location and Geography. Uzbekistan's 174,330 square miles (451,515 square kilometers), an area slightly larger than California, begin in the Karakum (Black Sand) and Kyzlkum (Red Sand) deserts of Karakalpakistan. The arid land of this autonomous republic supports a nomadic lifestyle. Recently, the drying up of the Aral Sea has devastated the environment, causing more than 30 percent of the area's population to leave, from villages in the early 1980s and then from cities. This will continue; the area was hit by a devastating drought in the summer of 2000.

Population increases to the east, centered around fertile oases and the valleys of the Amu-Darya River, once known as the Oxus, and the Zeravshan River, which supports the ancient city-states of Bokhara and Samarkand. The Ferghana Valley in the east is the heart of Islam in Uzbekistan. Here, where the country is squeezed between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, the mountainous terrain supports a continuing nomadic lifestyle, and in recent years has provided a venue for fundamentalist guerrillas. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Afghanistan also border the country. In 1867 the Russian colonial government moved the capital from Bokhara to Tashkent. With 2.1 million people, it is the largest city in Central Asia.

Linguistic Affiliation. Uzbek is the language of about twenty million Uzbeks living in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan. The language is Turkic and abounds with dialects, including Qarlug (which served as the literary language for much of Uzbek history), Kipchak, Lokhay, Oghuz, Qurama, and Sart, some of which come from other languages. Uzbek emerged as a distinct language in the fifteenth century. It is so close to modern Uyghur that speakers of each language can converse easily. Prior to Russian colonization it would often have been hard to say where one Turkic language started and another ended. But through prescribed borders, shifts in dialect coalesced into distinct languages. The Soviets replaced its Arabic script briefly with a Roman script and then with Cyrillic. Since independence there has been a shift back to Roman script, as well as a push to eliminate words borrowed from Russian.

About 14 percent of the population—mostly non-Uzbek—speak Russian as their first language; 5 percent speak Tajik. Most Russians do not speak Uzbek. Under the Soviet Union, Russian was taught as the Soviet lingua franca, but Uzbek was supported as the indigenous language of the republic, ironically resulting in the deterioration of other native languages and dialects. Today many people still speak Russian, but the government is heavily promoting Uzbek.

Symbolism. Symbols of Uzbekistan's independence and past glories are most common. The flag and national colors—green for nature, white for peace, red for life, and blue for water—adorn murals and walls. The twelve stars on the flag symbolize the twelve regions of the country. The crescent moon, a symbol of Islam, is common, though its appearance on the national flag is meant not as a religious symbol but as a metaphor for rebirth. The mythical bird Semurg on the state seal also symbolizes a national renaissance. Cotton, the country's main source of wealth, is displayed on items from the state seal to murals to teacups. The architectures of Samara and Bukhara also symbolize past achievements.

Amir Timur, who conquered a vast area of Asia from his seat in Samarkand in the fourteenth century, has become a major symbol of Uzbek pride and potential and of the firm but just and wise ruler—a useful image for the present government, which made 1996 the Year of Amir Timur. Timur lived more than a century before the Uzbeks reached Uzbekistan.

Independence Day, 1 September, is heavily promoted by the government, as is Navruz, 21 March, which highlights the country's folk culture.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The Uzbeks coalesced by the fourteenth century in southern Siberia, starting as a loose coalition of Turkic-Mongol nomad tribes who converted to Islam. In the first half of the fifteenth century Abu al-Khayr Khan, a descendant of Genghis Khan, led them south, first to the steppe and semidesert north of the Syr-Daria River. At this time a large segment of Uzbeks split off and headed east to become the Kazakhs. In 1468 Abu'l Khayr was killed by a competing faction, but by 1500 the Uzbeks had regrouped under Muhammad Shaybani Khan, and invaded the fertile land of modern Uzbekistan. They expelled Amir Timur's heirs from Samarkand and Herat and took over the city-states of Khiva, Khojand, and Bokhara, which would become the Uzbek capital. Settling down, the Uzbeks traded their nomadism for urban living and agriculture.

The first century of Uzbek rule saw a flourishing of learning and the arts, but the dynasty then slid into decline, helped by the end of the Silk Route trade. In 1749 invaders from Iran defeated Bokhara and Khiva, breaking up the Uzbek Empire and replacing any group identity with the division between Sarts, or city dwellers, and nomads. What followed was the Uzbek emirate of Bokhara and Samarkand, and the khanates of Khiva and Kokand, who ruled until the Russian takeover.

Russia became interested in Central Asia in the eighteenth century, concerned that the British might break through from colonial India to press its southern flank. Following more than a century of indecisive action, Russia in 1868 invaded Bokhara, then brutally subjugated Khiva in 1873. Both were made Russian protectorates. In 1876, Khokand was annexed. All were subsumed into the Russian province of Turkistan, which soon saw the arrival of Russian settlers.

The 1910s produced the Jadid reform movement, which, though short-lived, sought to establish a community beholden neither to Islamic dogma nor to Russian colonists, marking the first glimmer of national identity in many years. With the Russian Revolution in 1917 grew hopes of independence, but by 1921 the Bolsheviks had reasserted control. In 1924 Soviet planners drew the borders for the soviet socialist republics of Uzbekistan and Karakalpakistan, based around the dominant ethnic groups. In 1929 Tajikstan was split off from the south of Uzbekistan, causing lasting tension between the two; many Uzbeks regard Tajiks as Persianized Uzbeks, while Tajikstan resented Uzbekistan's retention of the Tajik cities of Bokhara and Samarkand. Karakalpakistan was transferred to the Uzbekistan SSR in 1936, as an autonomous region. Over the ensuing decades, Soviet leaders solidified loose alliances and other nationalities into what would become Uzbek culture.

In August 1991 Uzbek Communists supported the reactionary coup against Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. After the coup failed, Uzbekistan declared its independence on 1 September. Though shifting away from communism, President Islom Kharimov, who had been the Communist Party's first secretary in Uzbekistan, has maintained absolute control over the independent state. He has continued to define a single Uzbek culture, while obscuring its Soviet creation.

National Identity. The Soviet government, and to a lesser extent the Russian colonial government that preceded it, folded several less prominent nationalities into the Uzbeks. The government then institutionalized a national Uzbek culture based on trappings such as language, art, dress, and food, while imbuing them with meanings more closely aligned with Communist ideology. Islam was removed from its central place, veiling of women was banned, and major and minor regional and ethnic differences were smoothed over in favor of an ideologically acceptable uniformity.

Since 1991 the government has kept the Soviet definition of their nationhood, simply because prior to this there was no sense or definition of a single Uzbek nation. But it is literally excising the Soviet formation of the culture from its history books; one university history test had just 1 question of 850 dealing with the years 1924 to 1991.

Ethnic Relations. The Soviet-defined borders left Uzbeks, Kyrgiz, Tajiks, and others on both sides of Uzbekistan. Since independence, tightening border controls and competition for jobs and resources have caused difficulties for some of these communities, despite warm relations among the states of the region.

In June 1989, rioting in the Ferghana Valley killed thousands of Meskhetian Turks, who had been deported there in 1944. Across the border in Osh, Kyrgyzstan, the Uzbek majority rioted in 1990 over denial of land.

There is official support of minority groups such as Russians, Koreans, and Tatars. These groups have cultural centers, and in 1998 a law that was to have made Uzbek the only language of official communication was relaxed. Nevertheless, non-Uzbek-speakers have complained that they face difficulties finding jobs and entering a university. As a result of this and of poor economic conditions, many Russians and others have left Uzbekistan.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

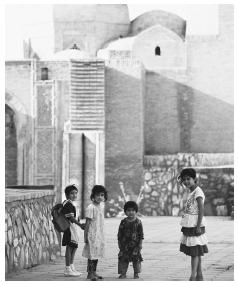

In ancient times the cities of Samarkand and Bokhara were regarded as jewels of Islamic architecture, thriving under Amir Timur and his descendants the Timurids. They remain major tourist attractions.

During the Soviet period, cities became filled with concrete-slab apartment blocks of four to nine stories, similar to those found across the USSR. In villages and suburbs, residents were able to live in more traditional one-story houses built around a courtyard. These houses, regardless of whether they belong to rich or poor, present a drab exterior, with the family's wealth and taste displayed only for guests. Khivan houses have a second-story room for entertaining guests. Since independence, separate houses have become much more popular, supporting something of a building boom in suburbs of major cities. One estimate puts two-thirds of the population now living in detached houses.

The main room of the house is centered around the dusterhon, or tablecloth, whether it is spread on the floor or on a table. Although there are not separate areas for women and children, women tend to gather in the kitchen when male guests are present.

Each town has a large square, where festivals and public events are held.

Parks are used for promenading; if a boy and a girl are dating, they are referred to as walking together. Benches are in clusters, to allow neighbors to chat.

Food and Economy

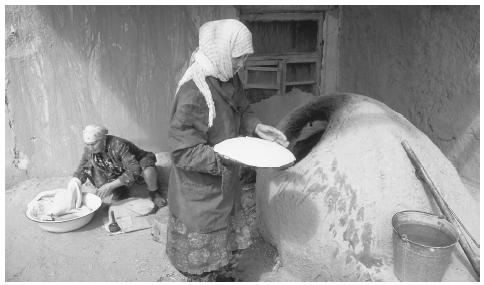

Food in Daily Life. Bread holds a special place in Uzbek culture. At mealtime, bread will be spread to cover the entire dusterhon. Traditional Uzbek bread, tandir non, is flat and round. It is always torn by hand, never placed upside down, and never thrown out.

Meals begin with small dishes of nuts and raisins, progressing through soups, salads, and meat dishes and ending with palov, a rice-and-meat dish synonymous with Uzbek cuisine throughout the former Soviet Union; it is the only dish often cooked by men. Other common dishes, though not strictly Uzbek, include monti, steamed dumplings of lamb meat and fat, onions, and pumpkin, and kabob, grilled ground meat. Uzbeks favor mutton; even the nonreligious eschew pig meat.

Because of their climate, Uzbeks enjoy many types of fruits, eaten fresh in summer and dried in winter, and vegetables. Dairy products such as katyk, a liquid yogurt, and suzma, similar to cottage cheese, are eaten plain or used as ingredients.

Tea, usually green, is drunk throughout the day, accompanied by snacks, and is always offered to guests.

Meals are usually served either on the floor, or on a low table, though high tables also are used. The table is always covered by a dusterhon. Guests sit on carpets, padded quilts, chairs, or beds, but never on pillows. Men usually sit cross-legged, women with their legs to one side. The most respected guests sit away from the entrance. Objects such as shopping bags, which are considered unclean, never should be placed on the dusterhon, nor should anyone ever step on or pass dirty items over it.

The choyhona, or teahouse, is the focal point of the neighborhood's men. It is always shaded, and if possible located near a stream.

The Soviets introduced restaurants where meals center around alcohol and can last through the night.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Uzbeks celebrate whenever possible, and parties usually consist of a large meal ending with palov. The food is accompanied by copious amounts of vodka, cognac, wine, and beer. Elaborate toasts, given by guests in order of their status, precede each round of shots. After, glasses are diligently refilled by a man assigned the task. A special soup of milk and seven grains is eaten on Navruz. During the month of Ramadan, observant Muslims fast from sunrise until sunset.

Basic Economy. The majority of goods other than food come from China, Turkey, Pakistan, and Russia. It is very common for families in detached homes to have gardens in which they grow food or raise a few animals for themselves, and if possible, for sale. Even families living in apartments will try to grow food on nearby plots of land, or at dachas.

Land Tenure and Property. Beginning in 1992, Uzbekistanis have been able to buy their apartments or houses, which had been state property, for the equivalent of three months' salary. Thus most homes have become private property.

Agricultural land had been mainly owned by state or collective farms during the Soviet period. In many cases the same families or communities that farmed the land have assumed ownership, though they are still subject to government quotas and government guidelines, usually aimed at cotton-growing.

About two-thirds of small businesses and services are in private hands. Many that had been state-owned were auctioned off. While the former nomenklatura (government and Communist Party officials) often won the bidding, many businesses also have been bought by entrepreneurs. Large factories, however, largely remain state-owned.

Major Industries. Uzbekistan's industry is closely tied to its natural resources. Cotton, the white gold of Central Asia, forms the backbone of the economy, with 85 percent exported in exchange for convertible currency. Agricultural machinery, especially for cotton, is produced in the Tashkent region. Oil refineries produce about 173,000 barrels a day.

The Korean car maker Daewoo invested $650 million in a joint venture, UzDaewoo, at a plant in Andijan, which has a capacity of 200,000 cars. However, in 1999 the plant produced just 58,000 cars, and it produced far less in 2000, chiefly for the domestic market. With Daewoo's bankruptcy in November 2000, the future of the plant is uncertain at best.

Trade. Uzbekistan's main trading partners are Russia, South Korea, Germany, the United States, Turkey, and Kazakhstan. Before independence, imports were mainly equipment, consumer goods, and foods. Since independence, Uzbekistan has managed to stop imports of oil from Kazakhstan and has also lowered food imports by reseeding some cotton fields with grain.

Uzbekistan is the world's third-largest cotton exporter.

Uzbekistan exported about $3 billion (U.S.), primarily in cotton, gold, textiles, metals, oil, and natural gas, in 1999. Its main markets are Russia, Switzerland, Britain, Belgium, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan.

Division of Labor. According to government statistics, 44 percent of workers are in agriculture and forestry; 20 percent in industry; 36 percent in the service sector. Five percent unemployed, and 10 percent are underemployed. Many rural jobless, however, may be considered agricultural workers.

A particular feature of the Uzbekistan labor system is the requirement of school and university students, soldiers, and workers to help in the cotton harvest. They go en masse to the fields for several days to hand-pick cotton.

Many Uzbeks, particularly men, work in other parts of the former Soviet Union. Bazaars from Kazakhstan to Russia are full of Uzbek vendors, who command higher prices for their produce the farther north they travel. Others work in construction or other seasonal labor to send hard currency home.

About 2 percent of the workforce is of pension age and 1 percent is under sixteen.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. During the Soviet Union, Uzbekistani society was stratified not by wealth but by access to products, housing, and services. The nomenklatura could find high-quality consumer goods, cars, and homes that simply were unattainable by others. Since independence, many of these people have kept jobs that put them in positions to earn many times the $1,020 (U.S.) average annual salary reported by the United Nations. It is impossible to quantify the number of wealthy, however, as the vast majority of their income is unreported, particularly if they are government officials.

Many members of the former Soviet intelligentsia—teachers, artists, doctors, and other skilled service providers—have been forced to move into relatively unskilled jobs, such as bazaar vendors and construction workers, where they could earn more money. Urban residents tend to earn twice the salaries of rural people.

Symbols of Social Stratification. As elsewhere in the former Soviet Union, the new rich tend to buy and show off expensive cars and limousines, apartments, and clothes and to go to nightclubs. Foreign foods and goods also are signs of wealth, as is a disdain for shopping in bazaars.

Political Life

Government. Uzbekistan is in name republican but in practice authoritarian, with Kharimov's Halq Tarakiati Partiiasi, or People's Democratic Party, controlling all aspects of governance. On 9 January 2000 he was reelected for a five-year term, with a 92 percent turnout and a 92 percent yes vote. Earlier, a March 1995 referendum to extend his term to 2000 resulted in a 99 percent turnout and a 99 percent yes vote. The legislature, Oliy Majlis, was inaugurated in 1994. At that time the ruling party captured 193 seats, though many of these candidates ran as independents. The opposition political movement Birlik, or Unity, and the party Erk, or Will, lack the freedom to directly challenge the government.

Makhallas, or neighborhood councils of elders, provide the most direct governance. Some opinion polls have ranked makhallas just after the president in terms of political power. Makhallahs address social needs ranging from taking care of orphans, loaning items, and maintaining orderly public spaces, to sponsoring holiday celebrations. In Soviet times these were institutionalized, with makhalla heads and committees appointed by the local Communist Party. Then and now, however, makhallas have operated less smoothly in neighborhoods of mixed ethnicities.

Leadership and Political Officials. The president appoints the head, or khokim, of each of Uzbekistan's 12 regions, called viloyatlars, and of Karakalpakistan and Tashkent, who in turn appoint the khokims of the 216 regional and city governments. This top-down approach ensures a unity of government policies and leads to a diminishing sense of empowerment the farther one is removed from Kharimov.

Khokims and other officials were chiefly drawn from the Communist Party following independence—many simply kept their jobs—and many remain. Nevertheless, Kharimov has challenged local leaders to take more initiative, and in 1997 he replaced half of them, usually with public administration and financial experts, many of whom are reform-minded.

Corruption is institutionalized at all levels of government, despite occasional prosecution of officials. Students, for example, can expect to pay bribes to enter a university, receive high grades, or be exempted from the cotton harvest.

Social Problems and Control. The government has vigorously enforced laws related to drug trafficking and terrorism, and reports of police abuse and torture are widespread. The constitution calls for independent judges and open access to proceedings and justice. In practice, defendants are seldom acquitted, and when they are, the government has the right to appeal.

Petty crime such as theft is becoming more common; violent crime is much rarer. Anecdotal evidence points to an increase in heroin use; Uzbekistan is a transshipment point from Afghanistan and Pakistan to Europe, and access is relatively easy despite tough antidrug laws.

People are often reluctant to call the police, as they are not trusted. Instead, it is the responsibility of families to see that their members act appropriately. Local communities also exert pressure to conform.

Military Activity. Uzbekistan's military in 2000 was skirmishing with the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, a militant group opposed to the secular regime, and numbering in the hundreds or thousands. Besides clashes in the mountains near the Tajikistani border, the group has been blamed for six car bombings in Tashkent in February 2000.

Uzbekistan spends about $200 million (U.S.) a year on its military and has 150,000 soldiers, making it the strongest in the region.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Most domestic nongovernmental organizations are funded and supported by the government, and all must be registered. Kamolot, registered in 1996, is the major youth organization, and is modeled on the Soviet Komsomol. Ekosan is an environmental group. The Uzbek Muslim Board has been active in building mosques and financing religious education. The Women's Committee of Uzbekistan, a government organization, is tasked with ensuring women's access to education as well as employment and legal rights, and claims three million members.

The government also has set up quasi nongovernmental organizations, at times to deflect attention from controversial organizations. The Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan, for example, was denied registration from 1992 to 1997, before the government set up its own human rights monitor.

The leaders of these groups may receive privileges once granted to the Soviet nomenklatura, such as official cars and well-equipped offices.

There are no independent trade unions, though government-sponsored unions are common. The Employment Service and Employment Fund was set up in 1992 to address issues of social welfare, employment insurance, and health benefits for workers.

Ironically, some truly independent organizations from the Soviet period, such as the Committee to Save the Aral Sea, were declared illegal in 1994. Social groups associated with Birlik also have been denied registration.

Gender Roles and Statuses

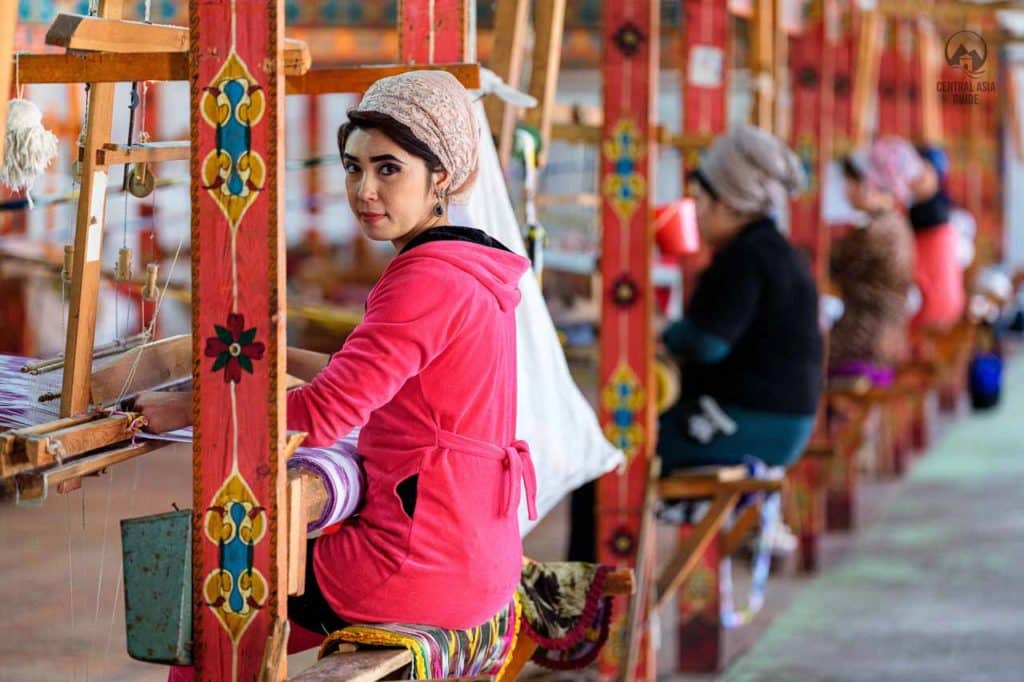

Division of Labor by Gender. Before the Soviet period, men worked outside the house while women did basic domestic work, or supplemented the family income by spinning, weaving, and embroidering with silk or cotton. From the 1920s on, women entered the workforce, at textile factories and in the cotton fields, but also in professional jobs opened to them by the Soviet education system. They came to make up the great majority of teachers, nurses, and doctors. Family pressure, however, sometimes kept women from attaining higher education, or working outside the home. With independence, some women have held on to positions of power, though they still may be expected to comport themselves with modesty. Men in modern Uzbekistan, though, hold the vast majority of managerial positions, as well as the most labor-intensive jobs. It is common now for men to travel north to other former Soviet republics to work in temporary jobs. Both sexes work in bazaars.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Uzbekistan is a male-dominated society, particularly in the Ferghana Valley. Nevertheless, women make up nearly half the workforce. They hold just under 10 percent of parliamentary seats, and 18 percent of administrative and management positions, according to U.N. figures.

Women run the households and traditionally control the family budgets. When guests are present they are expected to cloister themselves from view.

In public women are expected to cover their bodies completely. Full veiling is uncommon, though it is occasionally practiced in the Ferghana Valley. Women often view this as an expression of their faith and culture rather than as an oppressive measure.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Uzbek women usually marry by twenty-one; men not much later. Marriage is an imperative for all, as families are the basic structure in society. A family's honor depends on their daughters' virginity; this often leads families to encourage early marriage.

In traditional Uzbek families, marriages are often still arranged between families; in more cosmopolitan ones it is the bride and groom's choice. Either way, the match is subject to parental approval, with the mother in practice having the final word. Preference is given to members of the kin group. There is particular family say in the youngest son's choice, as he and his bride will take care of his parents. People tend to marry in their late teens or early twenties. Weddings often last for days, with the expense borne by the bride's family. The husband's family may pay a bride price. Polygamy is illegal and rare, but it is not unknown.

Following independence, divorce has become more common, though it is still rare outside of major cities. It is easier for a man to initiate divorce.

Domestic Unit. Uzbek families are patriarchal, though the mother runs the household. The average family size is five or six members, but families of ten or more are not uncommon.

Kin Groups. Close relations extends to cousins, who have the rights and responsibilities of the nuclear family and often are called on for favors. If the family lives in a detached house and there is space, the sons may build their homes adjacent to or around the courtyard of the parents' house.

Socialization

Infant Care. Uzbek babies are hidden from view for their first forty days. They are tightly swaddled when in their cribs and carried by their mothers. Men generally do not take care of or clean babies.

Child Rearing and Education. Children are cherished as the reason for life. The mother is the primary caretaker, and in case of divorce, she will virtually always take the children. The extended family and the community at large, however, also take an interest in the child's upbringing.

When children are young, they have great freedom to play and act out. But as they get older, particularly in school, discipline increases. A good child becomes one who is quiet and attentive, and all must help in the family's labor.

All children go to school for nine years, with some going on to eleventh grade; the government is increasing mandatory education to twelve years.

Higher Education. Enrollment in higher-education institutions is about 20 percent, down from more than 30 percent during the Soviet period. A major reason for the decline is that students do not feel a higher education will help them get a good job; also contributing is the emigration of Russians, and declining standards related to budget cutbacks. Nevertheless, Uzbeks, particularly in cities, still value higher education, and the government gives full scholarships to students who perform well.

Elders are respected in Uzbek culture. At the dusterhon, younger guests will not make themselves more comfortable than their elders. The younger person should always greet the older first.

Men typically greet each other with a handshake, the left hand held over the heart. Women place their right hand on the other's elbow. If they are close friends or relatives, they may kiss each other on the cheeks.

If two acquaintances meet on the street, they will usually ask each other how their affairs are. If the two don't know each other well, the greeting will be shorter, or could involve just a nod.

Women are expected to be modest in dress and demeanor, with clothing covering their entire body. In public they may walk with their head tilted down to avoid unwanted attention. In traditional households, women will not enter the room if male guests are present. Likewise, it is considered forward to ask how a man's wife is doing. Women generally sit with legs together, their hands in their laps. When men aren't present, however, women act much more casually.

People try to carry themselves with dignity and patience, traits associated with royalty, though young men can be boisterous in public.

People tend to dress up when going out of the house. Once home they change, thus extending the life of their street clothes.

Religious Beliefs. Uzbeks are Sunni Muslims. The territory of Uzbekistan has been a center of Islam in the region for a thousand years, but under the Soviet Union the religion was heavily controlled: mosques were closed and Muslim education was banned. Beginning in 1988, Uzbeks have revived Islam, particularly in the Ferghana Valley, where mosques have been renovated. The call to prayer was everywhere heard five times a day before the government ordered the removal of the mosques' loudspeakers in 1998.

The state encourages a moderate form of Islam, but Kharimov fears the creation of an Islamic state. Since the beginning of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan's terror campaign in February 1999, he has cracked down even further on what he perceives as extremists, raising claims of human rights abuses. The government is particularly concerned about what it labels Wahhabism, a fundamentalist Sunni sect that took hold in the Ferghana Valley following independence.

Nine percent of the population is Russian Orthodox. Jews, Baptists, Roman Catholics, Lutherans, Seventh-Day Adventists, evangelical and Pentecostal Christians, Buddhists, Baha'is, and Hare Krishnas also are present.

Religious Practitioners. Most Sunni Uzbeks are led by a state-appointed mufti. Independent imams are sometimes repressed, and in May 1998, a law requiring all religious groups to register with the government was enacted. In addition to leading worship, the Muslim clergy has led mosque restoration efforts and is playing an increasing role in religious education.

Death and the Afterlife. Uzbeks bury their deceased within twenty-four hours of death, in above-ground tombs. At the funeral, women wail loudly and at specific times. The mourning period lasts forty days. The first anniversary of the death is marked with a gathering of the person's friends and relatives.

Muslims believe that on Judgment Day, each soul's deeds will be weighed. They will then walk across a hair-thin bridge spanning Hell, which leads to Paradise. The bridge will broaden under the feet of the righteous, but the damned will lose their balance and fall.

Medicine and Health Care

Current health practices derive from the Soviet system. Health care is considered a basic right of the entire population, with clinics, though ill-equipped, in most villages, and larger facilities in regional centers. Emphasis is on treatment over prevention. Yet the state health care budget—80 million dollars in 1994—falls far short of meeting basic needs; vaccinations, for example, fell off sharply following independence. Exacerbating the situation is a lack of potable water, industrial pollution, and a rise in infectious diseases such as tuberculosis.

Perhaps the most common traditional health practices are shunning cold drinks and cold surfaces, which are believed to cause colds and damage to internal organs, and avoiding drafts, or bad winds. Folk remedies and herbal treatments also are common. An example is to press bread to the ailing part of the body. The sick person then gives a small donation to a homeless person who will agree to take on his or her illness.

Secular Celebrations

The major secular holidays are New Year's Day (1 January); Women's Day (8 March), a still popular holdover from the Soviet Union, when women receive gifts; Navrus (21 March), originally a Zoroastrian holiday, which has lost its religious significance but is still celebrated with Sumaliak soup, made from milk and seven grains; Victory Day (9 May), marking the defeat of Nazi Germany; and Independence Day (1 September), celebrating separation from the Soviet Union.

Uzbeks typically visit friends and relatives on holidays to eat large meals and drink large amounts of vodka. Holidays also may be marked by concerts or parades centered on city or town squares or factories. The government marks Independence Day and Navrus with massive outdoor jamborees in Tashkent, which are then broadcast throughout the country, and places of work or neighborhoods often host huge celebrations.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. During the Soviet period, the government gave extensive support to the arts, building cultural centers in every city and paying the salaries of professional artists. With independence, state funding has shrunk, though it still makes up the bulk of arts funding. Many dance, theater, and music groups continue to rely on the state, which gives emphasis to large productions and extravaganzas, controls major venues, and often has an agenda for the artists to follow.

Other artists have joined private companies who perform for audiences of wealthy business-people and tourists. Some money comes in from corporate sponsorship and international charitable organizations—for example UNESCO and the Soros Foundation's Open Society Institute. Yet many artists have simply been forced to find other work.

Literature. The territory of Uzbekistan has a long tradition of writers, though not all were Uzbek. The fifteenth-century poet Alisher Navoi, 1441–1501, is most revered; among his works is a treatise comparing the Persian and Turkish languages. Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, 973–1048, born in Karakalpakistan, wrote a massive study of India. Ibn Sina, also known as Avicenna, 980–1037, wrote The Cannon of Medicine. Omar Khayyam, 1048–1131, came to Samarkand to pursue mathematics and astronomy. Babur, 1483–1530, born in the Ferghana Valley, was the first Moghul leader of India, and wrote a famous autobiography.

Until the twentieth century, Uzbek literary tradition was largely borne by bakshi, elder minstrels who recited myths and history through epic songs, and otin-oy, female singers who sang of birth, marriage and death.

The Jadids produced many poets, writers, and playwrights. These writers suffered greatly in the Stalinist purges of the 1930s. Later the Soviet Union asked of its writers that they be internationalists and further socialist goals. Abdullah Qahhar, 1907–1968, for example, satirized Muslim clerics. But with the loosening of state control in the 1980s, a new generation of writers renewed the Uzbek language and Uzbek themes. Many writers also were active in Birlik, which started as a cultural movement but is now suppressed.

Graphic Arts. Uzbekistan has begun a revival of traditional crafts, which suffered from the Soviet view that factory-produced goods were superior to handicrafts. Now master craftsmen are reappearing in cities such as Samarkand and Bukhara, supported largely by foreign tourists. Miniature painting is narrative in character, using a wide palette of symbols to tell their stories. They can be read from right to left as a book, and often accompany works of literature. Wood carving, of architectural features such as doors and pillars and of items such as the sonduq, a box given to a bride by her parents, also is regaining a place in Uzbek crafts. Ikat is a method of cloth dying, now centered in the Yordgorlik Silk Factory in Margilan. Silk threads are tie-dyed, then woven on a loom to create soft-edged designs for curtains, clothing, and other uses.

Performance Arts. Uzbek music is characterized by reedy, haunting instruments and throaty, nasal singing. It is played on long-necked lutes called dotars, flutes, tambourines, and small drums. It developed over the past several hundred years in the khanates on the territory of modern Uzbekistan, where musicians were a central feature of festivals and weddings. The most highly regarded compositions are cycles called maqoms. Sozandas, sung by women accompanied by percussion instruments, also are popular. In the 1920s, Uzbek composers were encouraged, leading to a classical music tradition that continues today. Modern Uzbek pop often combines elements of folk music with electric instruments to create dance music.

Uzbek dance is marked by fluid arm and upper-body movement. Today women's dance groups perform for festivals and for entertainment, a practice started during the Soviet period. Earlier, women danced only for other women; boys dressed as women performed for male audiences. One dance for Navruz asks for rain; others depict chores, other work, or events. Uzbek dance can be divided into three traditions: Bokhara and Samarkand; Khiva; and Khokand. The Sufi dance, zikr, danced in a circle accompanied by chanting and percussion to reach a trance state, also is still practiced.

Uzbekistan's theater in the twentieth century addressed moral and social issues. The Jadidists presented moral situations that would be resolved by a solution consistent with Islamic law. During the Soviet period dramatists were sometimes censored. The Ilkhom Theater, founded in 1976, was the first independent theater in the Soviet Union.

Admission to cultural events is kept low by government and corporate sponsorship. It also has become common for dancers to perform for groups of wealthy patrons.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Uzbekistan has several higher-education institutions, with departments aimed at conducting significant research. Funding, however, has lagged since independence. The goal of the Academy of Sciences in Tashkent is practical application of science. It has physical and mathematical, chemicalbiological, and social sciences departments, with more than fifty research institutions and organizations under them.

Bibliography

Adams, Laura L. "What Is Culture? Schemas and Spectacles in Uzbekistan." Anthropology of East Europe Review 16 (2): 65–71, 1998.

Ali, Muhammad. "Let Us Learn Our Inheritance: Get to Know Yourself." AACAR Bulletin 2 (3): 3–18, 1989.

Allworth, Edward A. The Modern Uzbeks: From the Fourteenth Century to the Present; A Cultural History, 1990.

Freedom House 2000. Freedom in the World, The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties, 1999–2000: Uzbekistan Country Report, 2000.

Griffin, Keith. Issues in Development Discussion Paper 13: The Macroeconomic Framework and Development Strategy in Uzbekistan, 1996.

Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch World Report 2000: Uzbekistan, 2000.

Jukes, Geoffrey J.; Kirill Nourzhanov, and Mikhail Alexandrov. Race, Religion, Ethnicity and Economics in Central Asia, 1998.

Kalter, Johannes, and Margareta Pavaloi. Uzbekistan: Heirs to the Silk Road, 1997.

Khan, Azizur Rahman. Issues in Development Discussion Paper 14: The Transition of Uzbekistan's Agriculture to a Market Economy, 1996.

Kharimov, Islom A. Uzbekistan on the Threshold of the Twenty-first Century: Challenges to Stability and Progress, 1998.

Nazarov, Bakhtiyar A., and Denis Sinor. Essays on Uzbek History, Culture, and Language, 1993.

Nettleton, Susanna. "Uzbek Independence and Educational Change," Central Asia Monitor 3, 1992.

Paksoy, H. B. "Z. V. Togan: The Origins of the Kazaks and the Ozbeks," Central Asian Survey 11 (3), 1992.

Prosser, Sarah. "Reform Within and Without the Law: Further Challenges for Central Asian NGOs," Harvard Asia Quarterly, 2000.

Schoeberlein-Engel, John. "The Prospects for Uzbek National Identity," Central Asia Monitor 2, 1996.

"Tamerlane v. Marx;" Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 50 (1), 1994.

U.N. Development Project. Human Development Report: Uzbekistan 1997, 1997.

UNESCO, Education Management Profile: Uzbekistan, 1998.

U.S. Department of State. Background Notes: Uzbekistan , 1998.

U.S. Department of State, Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA World Factbook , 2000.

U.S. Library of Congress. Kazakstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan: Country Studies, 1997.

—J EFF E RLICH

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

Uzbekistan’s History, Economic and Culture Research Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Uzbekistan is a country in central Asia which boarders Kazakhstan in the northern side, Kyrgyzstan in the eastern side and Tajikistan in the southern eastern side. During the 4 th century B.C it was under the Persian rule that had been conquered by Alexander the Great.

The region incorporated Islam as a religion in 8th century when the Arab forces invaded the land. Around the 13 th century the region was taken over by the Mongols from the Seljuk Turks. The 16 th century saw the region been merged with their neighbors but was not to last for long as the region broke into principalities (Adams 19).

However, the city-states, which included khanates, Kokand and Bukhara were not to last for long as the Russians conquered them in the 19 th century. In 1924, the territory was a republic but it is in 1925 that it became an independent under socialist republic. However, in 1991 the country declared its independence making September 1 st their national holiday. The country today enjoys independence with a presidential rule.

Economically, the people of Uzbekistan are agriculturalist, however, the country is endowed with many minerals. Cotton has been their main produce but has recently been replaced by natural gas. The other minerals that the Uzbekistan people are involved with are gold and uranium. The country has recently grown to be a manufacturing country, especially in the automobiles industrial where they are a big exporter to Russian market.

The state has always been in control of most business enterprises, but in the recent past free market has been endorsed (Oliker 46). It is not easy to determine the growth rate of the country because the government keeps unreliable records. However, it is notable much of the wealth of the country is held by the elite in the society with almost a quarter of the population living below the poverty line.

The government has been instrumental in preventing the country from facing capital outflow by ensuring that the country adopts the policy of substitution of their imports. The actions of the government to control economic activities have even made convertibility of different currencies of the world. The low economy has transformed to some of the individuals in the country getting involved to human trafficking business. The business usually involves girls, as they are traffics to other countries as prostitutes (Boĭkova 181).

Amongst the people of Uzbekistan, the elders are the most respected people in the society. They have a mode of greetings where the men put their hands on the heart of other men when greeting them, while women usually put their right hands on each other’s elbow. The mode of dressing especially to women was such that they were to cover their bodies with their heads looking down to avoid any attention. The people of Uzbekistan are mostly Muslims with a small percentage of people enjoying other religions like Buddhist and Jewish.

Traditionally, matters of marriage were left to the man and the women but the approval of the parent was important. Virginity among the women was upheld and women were expected to be married much earlier than the men. Bride price had to be paid by the family of the man, and the cost incurred in the marriage ceremony was covered by the family of the wife (Hanks 83).

There were defined duties of both men and women. While men were expected to work outside, the house women were expected to work indoors engaging in activities like weaving and spinning using cotton. Women were expected to cover the whole of their bodies when in public and they viewed it as observance of their faith (Adams 17). Traditional medicine was also incorporated in their treatment where herbs were used for treatment.

There was also a taboo of drinking cold drinks since it was viewed as the reason why people caught cold. Arts performance that dated back during the soviet rule is still practiced. They include the crafts work as well as miniature painting. However, the practice of their music by the instruments they used in past is still in practice. Dotars that were put on the legs, flutes, and small drums are still used in the performance of their art.

Unlike other countries in central Asia, Uzbekistan has adhered to the principle of legal stability. The constitution gives rights to the people to own private property and it views it as a way of giving self-respect to the people as well as a way of developing the society. Solid constitutional bases have been laid down through the years to promote and upgrade political and social relations.

Economic freedom of the citizens has been highly promoted as well as the spirit of entrepreneurship with an aim of eliminating the repugnant old command-administrative system. The country has also incorporated a legal and organization environment where the society of Uzbekistan integrates with the world. Uzbekistan has adopted an open door policy that grants foreign investors reliable regal guarantee and broad economic opportunities in the economic activities.

The environment for foreign investors has continually been improved as well as simplification of the procedures that are involved in creation of manufacturing enterprise for foreigners (Karimov 172). Regulatory acts created by Uzbekistan have had a comprehensive system of taxation and incentive against poetical and commercial risk for the foreigners. In turn, there has been active participation by foreign investors in this country.

Some of their favorable policies to the foreigners are: freedom of buying property that the state has already privatized as well as ownership rights to these properties. Enterprises owned by foreigners are allowed to export without licenses as well to import duty free property from joint ventures (Karimov 173).

Economic relations between Uzbekistan and the United States have mostly been controlled by the bi-literal trade agreement signed by the two countries. The agreement was signed in 1994 and one of the benefits the agreements had to Uzbekistan was that it had an exemption provision to many of the United States importing tariffs.

In the year 2000, the two countries signed a bilateral investment treaty but it did not come into force because of the weak economic reforms in Uzbekistan. In terms of imports and exports, Uzbekistan imports machines and equipment. Also inclusive in the list of the imports are chemical products and food items, especially the ones that deal in plastics. The exports to the United States include inorganic chemistry products machines and equipment (Group Taylor & Francis 2548).

American companies have also been involved in investing in Uzbekistan economy in establishment of technological base in both agriculture and mining sectors.

Infrastructure and food processing are also other sectors of the economy where American companies have actively involved themselves in. The American company General Motors has also established a strong link with the government of Uzbekistan and collaborated in manufacturing of cars. It is also notable that Uzbekistan is the biggest export of uranium in United States (Zhukov 213).

The relation between United States and Uzbekistan can be traced back to 1991 when Uzbekistan was established as an independent nation. The following year saw the establishment of Uzbekistan embassy in United States. From that time, as part of the U.S policy, campaigns have been launched to support Uzbekistan upheld the rule of law.

The relationship between the two countries increased after September 11 attacks, which led to the war in Afghanistan. However, the closeness between the two countries went a drift when United States requested the international community to get involved in investigating the Andijon violence of 2005.

The reason behind sourness in the relations on was because Uzbekistan did not want involvement of United States or other European powers in influencing the government activities. However, year 2007 saw the two countries improving the relationship among them (Thackrah 240).

The relations were all round as they included security issues civil issues as well as economic issues. It is also an attempt by the United States to ensure that there is peace in central Asia since Uzbekistan is the country with the biggest population and the most instrumental in keeping stability.

The new relation between the two countries has since to improve to the best as in the United States assistance budget there was a provision that seeks to ensure better livelihood for the people of Uzbekistan (Group Taylor & Francis 554). The relationship between the two countries has also promoted the level of education in Uzbekistan as many students from Uzbekistan have studied in American universities.

Works Cited

Adams, Laura L. “The Spectacular State: Culture and National Identity in Uzbekistan.” Durham: Duke University Press , 2010. Print

Boĭkova Elena Vladimirovna, R. B. Rybakov. “Kinship in the Altaic world: proceedings of the 48th Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Moscow 10-15 July, 2005.” Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag , 2006. Print

Group, Taylor & Francis. “Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2004, Volume 4.” Lndon: Routledge , 2003. Print

Group, Taylor & Francis. “Europa World Year Book 2, Book 2.” London: Taylor & Francis, 2004. Print

Hanks, Reuel R. “Central Asia: a global studies handbook.” Califonia: ABC-CLIO, 2005. Print

Karimov, I. A. “Uzbekistan on the threshold of the twenty-first century: challenges to stability and progress.” New York: Palgrave Macmillan , 1998. Print

Oliker Olga, Thomas S. Szayna. “Faultlines of conflict in Central Asia and the south Caucasus: implications for the U.S. Army, Issue 1598.” Califonia: Rand Corporation, 2003. Print

Thackrah, John Richard. “Dictionary of terrorism.” New York: Routledge , 2004. Print

Zhukov, Boris Z. Rumer Stanislav Vi︠a︡cheslavovich. “Central Asia: the challenges of independence.” New York: M.E. Sharpe , 1998. Print

- Social Performance of Gap Inc.

- Medical Ethics: Withholding Information From Patients

- Drug Trafficking and Terrorism in Central Asia: Implications for the US

- Singapore's Advancion in Economy, Tourism and Other Economy Building Sectors

- London as a Global City Essay

- A Trip to the Wonderland: Under the Arches of the Utah National Park

- Environmental Analysis in the UAE

- Physical Geography of Tristan da Cunha

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, February 20). Uzbekistan's History, Economic and Culture. https://ivypanda.com/essays/uzbekistan/

"Uzbekistan's History, Economic and Culture." IvyPanda , 20 Feb. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/uzbekistan/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Uzbekistan's History, Economic and Culture'. 20 February.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Uzbekistan's History, Economic and Culture." February 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/uzbekistan/.

1. IvyPanda . "Uzbekistan's History, Economic and Culture." February 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/uzbekistan/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Uzbekistan's History, Economic and Culture." February 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/uzbekistan/.

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

5 Interesting Historic Sites in Uzbekistan

With humans having lived in uzbekistan as early as the paleolithic period, uzbekistan is home to a number of fascinating historical sites. here's our pick of 5 of the best..

Lucy Davidson

30 sep 2021, @lucejuiceluce.

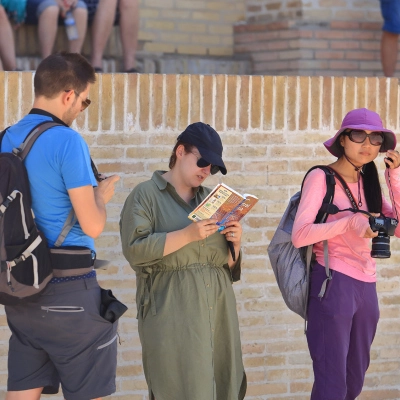

Having once been both a central point of the Silk Road and part of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan is a country which is rich in history. Today, the double-landlocked country is emerging from the break up of the Soviet Union in 1991, and is home to among the most devout Muslim populations in Asia.

Though it is a fairly isolated country, Uzbekistan is full of relatively unknown sites which hark back to its diverse history. From stunning mosques which punctuate the skyline alongside Soviet-era architecture, to older sites such as ancient cities and mausoleums, here are 5 key historic sites in Uzbekistan for any history enthusiast.

1. Guri Amir

Guri Amir, in the former Silk Road city of Samarkand in modern Uzbekistan, is the mausoleum of the Mongol leader Timur (1369-1405), also known as Tamerlane. Timur was responsible for building many of Samarkand’s most impressive sites, including the Registan trio of madrassahs.

A blue-domed building encrusted with Samarkand’s trademark clay tiles, Guri Amir is the final resting place not only of this famous leader, but of his two sons and two grandsons.

2. Registan of Samarkand

Registan is one of the main sites in the ancient city of Samarkand in Uzbekistan. Samarkand was founded in approximately 700 BC and its location along the vital trade route known as the ‘Silk Road’ transformed it into a prosperous centre of commerce.

Now made up of three ornate madrassahs – centres of learning – facing onto a central courtyard, Registan was the medieval centre of Samarkand. Of these three symmetrical buildings, each of which is elaborately adorned with glazed clay tiles, the Ulugh Beg Madrassah is the oldest, dating back to 1420. The other two madrassahs, Sher-Dor and Tillya-Kori, were built in the seventeenth century under the rule of Yalangtush Bakhodur. Registan is part of the UNESCO World Heritage site of Samarkand.

3. The Bibi-Khanym Mosque

The Bibi-Khanym Mosque in Samarkand in Uzbekistan was originally constructed by Timur (1369-1405), a warrior and Mongol leader who ruled this important Silk Road city.

A vast structure crowned by a blue dome and overlooking a courtyard, the Bibi-Khanym Mosque was built by Timur for his wife between 1399 and 1405. Much of the Bibi-Khanym Mosque was destroyed in an earthquake in the nineteenth century and has since been reconstructed.

4. Shah-i-Zinda

Shah-i-Zinda in the UNESCO-listed city of Samarkand in Uzbekistan is an incredible complex of mausoleums, mosques and madrassahs. The most important of these shrines, alluded to by the name ‘Shah-i-Zinda’, meaning ‘living king’, is what is thought to be the mausoleum of Kusam ibn Abbas, cousin of the Prophet Mohammed.

Like many of the buildings in Samarkand, the structures are adorned with geometric shapes created using colourful glazed tiles. Some of the buildings of Shah-i-Zinda have undergone significant (and controversial) renovations and reconstructions.

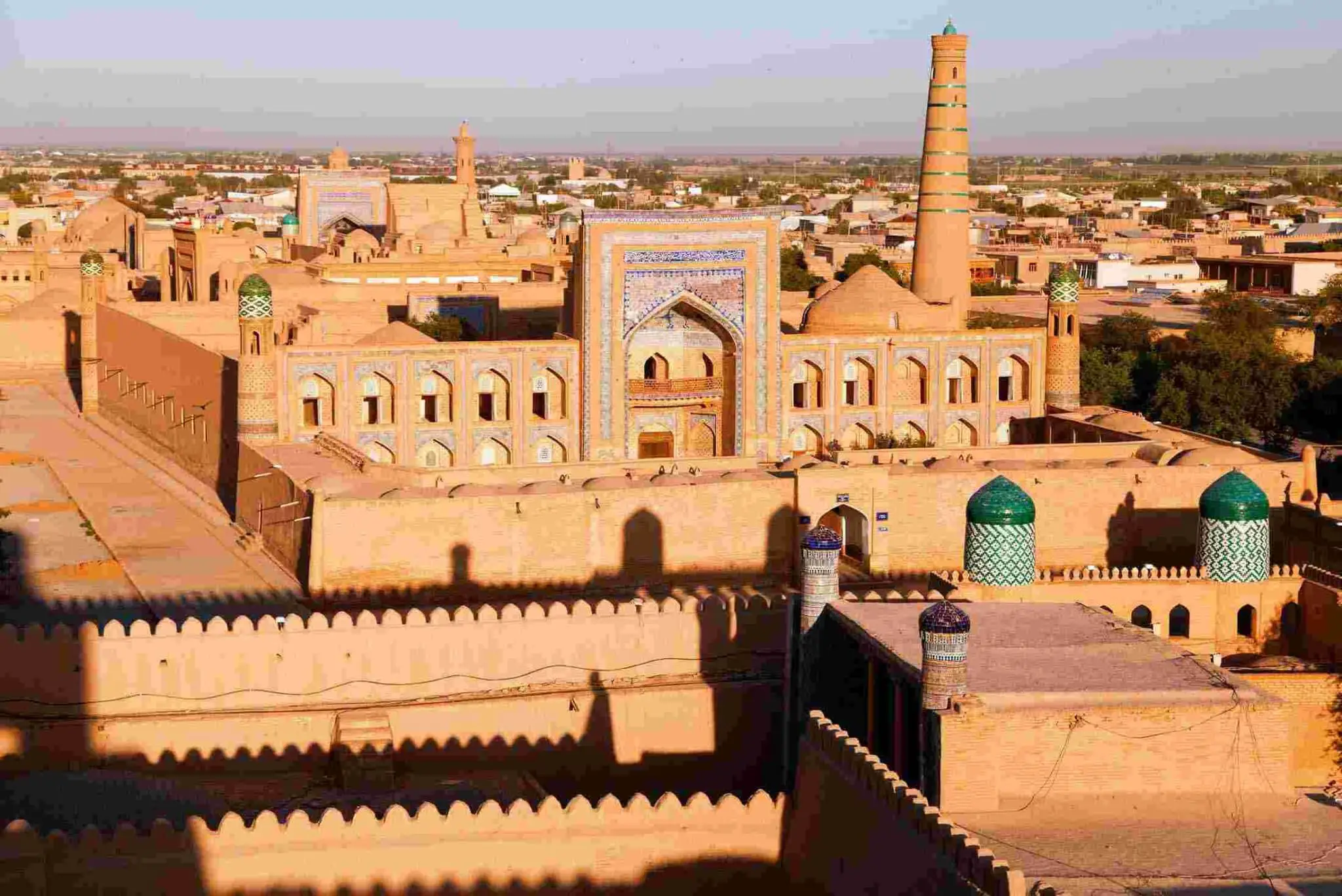

5. Itchan Kala

Itchan Kala is the inner town (protected by brick walls some 10 m high) of the old Khiva oasis, which was the last resting-place of caravans before undergoing the extensive desert crossing to Iran. Although few very old monuments still remain, it is a rounded and well-preserved example of the Muslim architecture of Central Asia.

Today, there are several outstanding structures such as the Djuma Mosque, the mausoleums, and the madrasas as well as the two stunning palaces built at the beginning of the 19th century by Alla-Kulli-Khan.

- About our Authors

- SRAS: Study Abroad or Online

- Folkways: Folk Culture

- PopKult: Popular Culture

- Students Abroad: Travel Guides

- Museum Studies Abroad: High Culture and City Planning

Uzbekistan: A GeoHistory Study Guide

9 November 2022

When the Silk Road passed through Uzbekistan, its cities grew to some of the world’s largest, most prosperous, and most learned. Many of the great architectural marvels built during those years still stand.

Today, Uzbekistan remains Central Asia’s most populous country. Although mostly desert, it is rich in mineral wealth and its Ferghana Valley is the region’s most agriculturally productive area. As the only state to border all five other Central Asian states, Uzbekistan is expected to be increasingly active in integrating the fractious but strategic region, especially as its new president has made this a stated priority.

Geohistory and Historical Development

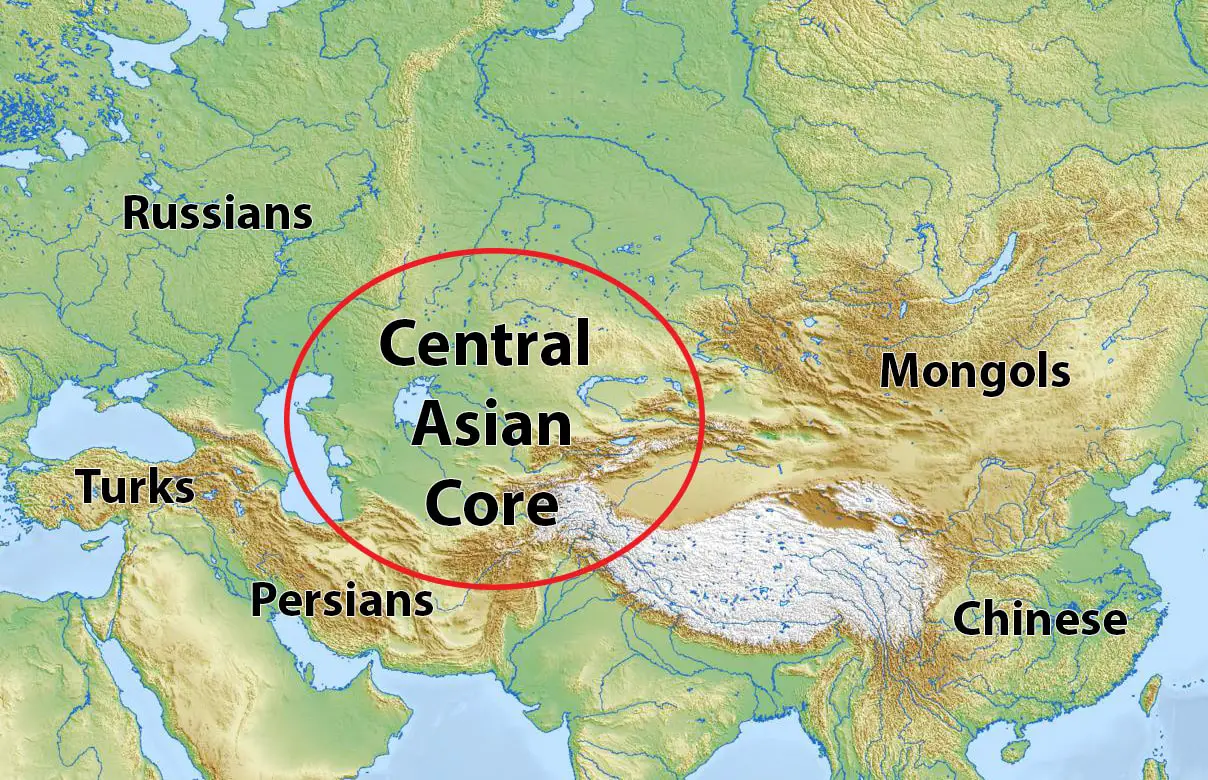

Uzbekistan was likely first populated when the world was much cooler and wetter. The area at that time was covered by grasslands. As it dried and warmed, water became scarcer and people adapted by engineering complex and highly efficient irrigation systems.

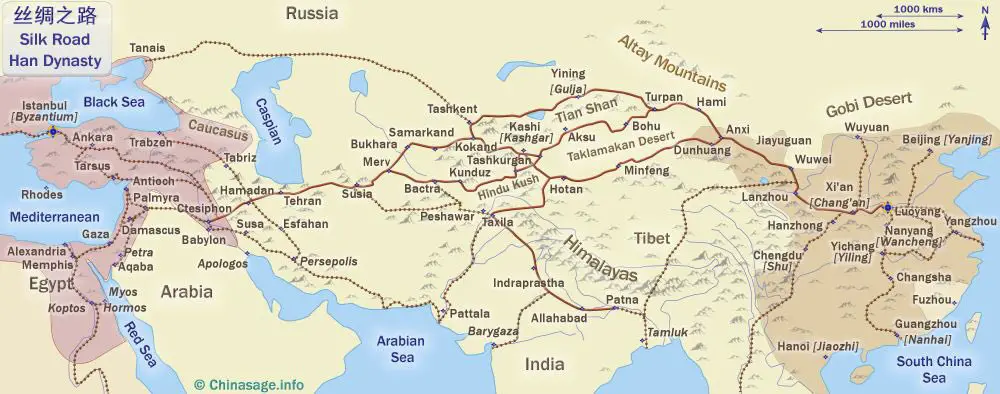

The drying landscape led to greater distance between communities, requiring more travel to sustain trade. This could be one reason why Central Asians were the first equestrians, allowing them to travel farther and faster overland than anyone had before. Central Asia came to be influenced by cultures as far apart as India, China, and Greece. Multiple languages and religions thrived there along what became “The Silk Road” – a multitude of trade networks that carried many goods across Eurasia, including those produced in Central Asia itself such as paper, textiles, pottery, jewelry, and more.

The Silk Road was not a single road – nor did it only carry silk. It was a complex trade network that stretched from China and India to Europe through Central Asia and carried paper, spices, pottery, gold, silver, and much more.

Wealth from this trade allowed rulers to lavishly support the arts and sciences, leading to a golden age between 800 and 1100. Central Asians made many contributions to mathematics including the invention of algebra and major contributions to trigonometry. They also made major contributions to astronomy, literature, religion, and architecture, including the invention of algebra. They also excelled at languages and translated scientific and philosophical works from many different lands. Much of this work was done in Persian or Arabic, which were then strong regional languages useful for widely spreading information. Because of this, many historians have incorrectly called these authors Persian or Arabic. In reality these thinkers were from the dozens of ethnicities native to this land.

Because of the barren distances between them, governments in Central Asia largely functioned as city states which were sometimes incorporated into larger empires but generally maintained a high degree of autonomy.

The firebird is one of many symbols to survive the Zoroastrian era and remain widely popular.

In part because of this diversity and autonomy, Islam was slowly adopted after its introduction with the Arab invasions in the 8th century. Islam was also locally adapted to existing beliefs. To this day, Islam in Central Asia still has its own unique elements, influenced in great part by Zorastrianism.

As advances were made globally in maritime technology, Central Asia’s overland Silk Road declined starting in the late 14th century. In parallel, Central Asia had another great flowering from 1370–1507 under the Timurid Empire, which united the area under a local Turkic-speaking empire for the first time and saw additional advances in politics, the military, science, and the arts.

Although the area would never be as powerful again, it largely maintained independence until the Russians invaded in the 19th century. It regained independence after the fall of the USSR.

Much of this history was spread over an area much larger than modern day Uzbekistan – especially in cities now in Turkmenistan and Afghanistan. However, the Uzbeks see all this history as part of their own cultural foundations.

Economy – Agriculture

A little larger than California, modern Uzbekistan is mostly flat desert. Mountains rise in the east, where most of the country’s water sources originate and where most of its population lives. While only 10% of the country can be used for intensive crop farming, agriculture employs 26% of the population and provides 27% of GDP.

Cotton and wheat, both water-intensive crops, are central to the economy. Soviet-era irrigation made this possible, largely using water that would have otherwise fed into the saline Aral Sea. This created the Aral Sea ecological disaster . The shrinking sea could no longer cool the area, leading to rising temperatures. The once important fishing industry was destroyed. Fine dust and salt from the now-dry sea bed is still blown into cities and farm land, creating health problems and reducing crop yields.

More water-efficient greenhouses for growing fruits and vegetables such as tomatoes and cucumbers for local consumption are increasingly common. However, agricultural reform on a scale that would restore the Aral Sea is not considered possible.

About half of Uzbekistan is desert scrub, and can support sheep and camel production. Industrial yarn, used to produce textiles, is Uzbekistan’s second largest export.

Economy – Minerals and Industry

Gold is, by far, Uzbekistan’s largest export, at about $6 billion a year and drawn from the world’s fourth largest deposits. Copper is the third largest export. Valuable deposits of uranium as well as silver, molybdenum (used in making steel), tungsten, zinc, and lead are also mined.

Uzbekistan’s large and well-educated workforce supports a well-developed industrial base that produces petrochemicals, automobiles (including Chevrolet and Daewoo), machinery (including John Deere tractors), textiles, and processed foods.

Mining and industry employ 30% of the population and produce 30% of GDP.

Economy – Energy, Transport, and Potential Growth

Uzbekistan is a net energy exporter with significant deposits of natural gas, oil, coal, and uranium. Despite a vast potential for solar power, its first plant, a Saudi investment, opened only in 2021. Before that, the only renewable sources of energy came from three hydropower plants in the country’s east. Plans exist to build more solar and wind plants, but considerable investment will be needed to achieve its potential.

Uzbekistan is a double-landlocked country with no sea access and its local rivers flow to inland seas, meaning that the country has very little water transport. Water transport is the the cheapest and most efficient transport means and often needs no additional infrastructure. Most of the world’s major economies today got a boost in some way from river transport and access to international markets via ocean access. Uzbekistan’s international river transport is largely limited to Afghan routes.

Without water transport, Uzbekistan is focusing on rail, the second most efficient. It has created an extensive high speed domestic rail system and is working with international partners to build new lines to increase connectivity and, eventually, access to ocean-accessible ports – in India, Iran, or Georgia. While most of these new lines are still theoretical, a line through Kyrgyzstan to China has already been announced and further expansion is planned.

Internally, a new bypass connecting the fertile Ferghana Valley and central Uzbekistan without the need to cross into Tajikistan was finished in 2016. This irked Tajikistan, which had often used the transit rights as a bargaining chip in relations with Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan is also part of the Turkmen-China Pipeline, completed in 2009, which allows diversification away from Russia and towards China for natural gas sales. Europe is also now looking for ways to directly import Central Asian gas, which would benefit Uzbekistan.

Uzbek airports, even in the capital, are small. However, expansion in air freight and tourist passenger flights is possible. Most major population centers and industrial zones are accessible by public roads in generally good condition.

For growth, most observers still agree that much more could be done to liberalize and streamline agriculture, encourage exports and SMEs, invest in energy efficiency and renewables, and better develop the country’s internal transport networks.

Society and Demographics

Uzbekistan’s population of 35 million is larger than that of the rest of Central Asia combined. With a fertility rate that has stayed above 2 throughout recent history, the population is growing and getting younger due to births and a significant emigration of older individuals seeking opportunity abroad.

About half of Uzbekistan’s population is rural. Despite fairly consistent economic growth for more than two decades, most Uzbeks are quite poor.

Ethnic Uzbeks account for 80% of the population. The Karakalpaks, the only major indigenous minority, have nearly doubled since 1989 but still account for only about 2% of the population, concentrated in an eponymous, semi-autonomous republic that accounts for 40% of Uzbekistan’s total territory. The region is arid and poor but has enjoyed cultural and linguistic freedom. The Karakalpaks have not been very active politically, with the notable exception of the 2022 Karakalpak Protests that erupted when the Uzbek president proposed removing the region’s constitutional autonomy. The protests were quelled only with a declared state of emergency.

Other minorities include growing numbers of Kyrgyz and Tajiks, stable numbers of Kazakhs and a shrinking number of Russians (to about half their 1989 population).

Russian remains taught in schools and is widely spoken in major cities, along with Uzbek. Grocery store labels are often in Russian. Although Uzbekistan adopted the Latin alphabet in 1992, it did not abandon Cyrillic, which remains most common.

More than 90 percent of the country is Muslim. The growing popularity and influence of religion comes with some fears of radicalization, particularly from groups in neighboring Afghanistan such as ISIS.

Briefly on Politics

Under former president Islam Karimov, Uzbekistan became increasingly isolated. He continued various soviet policies such as retaining state ownership of land and major industries, state production quotas and set prices, and conscripting labor, including school children, to help with the annual cotton harvest. This led many international clothing brands to boycott Uzbek cotton. Karimov, however, remains hugely popular in Uzbekistan and is credited with successfully guiding the country through the fall of Communism and to its current state of development.

Shavkat Mirziyoyev came into the presidency in 2016 promising to open the country. He quickly gained a reputation as a hands-on and energetic president, widely touring the country, consolidating his power, and making sure his reforms were being implemented. He also gained visits to many western and eastern countries, including the US.

Reforms have been increasing difficult to implement. For instance, although the state no longer presses for help in the cotton harvest, local bureaucrats, schoolheads, and others with power reportedly still do.

Regional Relations with Bordering Countries

Kazakh relations have been stable and prosperous. All border disputes were resolved by 2019. A formal alliance declared in 2021 has resulted in escalating trade and deeper integration between Central Asia’s two largest and most powerful states.

Turkmen relations were dangerously sour after the fall of the USSR, with border disputes and accusations of assassination plots. After changes in power in both countries, relations are mostly characterized by mutual trade and infrastructure talks.

Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan have Soviet-created enclaves of territory within the others. These have been a source of tension.

Kyrgyz relations are complicated by border disagreements, the treatment of Uzbek minorities in Kyrgyzstan and vice versa. Uzbekistan supplies most of the gas used by southern Kyrgyzstan. Kyrgyzstan aims to develop more hydroelectric power from rivers that flow to Uzbekistan, which worries this would impact its agricultural sector.

Similarly, Uzbekistan once threatened war over the Rogun Dam in Tajikistan. Tajikistan is also highly dependent on Uzbek gas. Tajikistan was also upset by the construction of the Kamchik rail line that allows internal Uzbek lines to bypass Tajik territory, further isolating Tajikistan and depriving it of customs duties. Relations have improved under Uzbekistan’s current president, who has focused on business and profits.

Afghanistan shares a small border with Uzbekistan. During the US occupation of Afghanistan, Uzbekistan provided transport routes and power for the country. Today, although Uzbekistan has not formally recognized the Taliban, it maintains contacts to help secure the border and facilitate trade and diplomacy.

Other Foreign Relations

US relations hit a low in 2005, when, after US criticism of the Andijan Massacre , Uzbekistan forced the US to close its military base in Uzbekistan. Especially since 2019, relations have improved, with the US providing aid to improve transport links to Afghanistan and push against drug and human trafficking from Afghanistan.

Russia’s state-owned Gazprom controls Uzbekistan’s pipelines. Russia is one of two routes for Uzbek gas export and the source of 55% of remittances from Uzbeks working abroad to support their families at home. Remittances make up ~12% of Uzbek GDP. Russia is Uzbekistan’s second largest trading partner. Although Uzbekistan left the Russia-led CSTO in 2019, the countries maintain good relations.

China is Uzbekistan’s largest trading partner and increasingly a source of loans and funding for infrastructure. Uzbekistan is working with Kyrgyzstan to sponsor a much awaited rail project linking China to Uzbekistan through Kyrgyzstan. Later expansions may extend through Turkmenistan to Iran. Connecting Central Asia to eastern Asia and India has long been seen as something as major economic and political goal – but has been spoiled by internal rivalries in Central Asia and instability in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Turkey is Uzbekistan’s fourth largest trading partner. Turkey has recently increased investments to Uzbekistan, building new thermal and natural gas electric plants. The two countries have recently signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement that should help boost investment and trade further. Both are also members of the Organization of Turkic States, which strives to coordinate economic and diplomatic activities between states with Turkic heritage.

Cultural and Identity Markers

The most revered person in Uzbek history is Timur (Tamerlane), the Turco-Mongol conqueror who founded the Bukhara-based Timurid Empire,the first Turkic-speaking empire. Tamerlane is remembered as a great statesman who built monuments, lavishly supported scientists and craftsmen, collected over 600,000 books and made traveling the Silk Road safe, and made Samarkand a world-famous cultural and commercial center.

Ulugbeg was the grandson of Timur, and is remembered as a “king astronomer” who valued education and science over religion and war. He opened his madrasas to men and women, locals and foreigners, Muslims and non-Muslims alike. During his 40 years of rule, no battles were fought, but schools were built and scientists supported.

Babur was another descendent of Timur, born in the Fergana Valley in 1483. He went on to found the Mughal Empire in India and is also highly regarded.

Uzbeks also count among their own many famous scientists that worked or were born within historical empires, but are not all, strictly speaking, Uzbek. This includes figures like Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī, a 9th-century Muslim mathematician and astronomer who introduced Hindu-Arabic numerals to Europe and is credited with inventing algebra. His name means “the native of Khwarazm,” a region that was part of Greater Iran, and is now part of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan has a national epic called Alpamysh, which also spans other Kipchak Turks’ cultures. The tale follows Alpamys and his bride Barchin, how they court, are wed, are separated, and eventually reunited. In the process, Alpamys exemplifies strength, wisdom, and bravery. Today, professional ashiqs still learn and perform the epic to music on traditional instruments, as it was handed down for many generations.

Alpomish also features endless battles, a feature of life at the time as Bukhara, Samarkand, and Khiva were rich prizes for enemy armies and have been among the most invaded places in the world. Alpomish shows that under these conditions, people dream of a hero to unite and protect them, which remains an enduring trope in Uzbek culture and politics.

The author with perhaps the most influence on modern literature is Abdulla Qodiriy, who lived and worked in the early twentieth century. He argued that Uzbekistan should be independent and develop on its own terms. In 1938 he was shot by the Soviets though he was officially sentenced to death only weeks later. Today, Abdulla Qodiriy remains one of Uzbekistan’s most widely read and known authors.

Three very common names in Uzbekistan remain Timur, Ulugbeg, and Abdulla.

Uzbekistan takes its culinary traditions seriously. The main national dish is plov, a hearty mix of rice, meat, carrots, and onions cooked in oil. It first became widely popular under the Abbasid Caliphate. Uzbekistan’s main national dumplings are manti: large, steamed dough packets filled with meat, onions and spices. Similar is the samsa – a large, baked dough packet filled with meat, onions, and spices. Lagman can be either a pasta soup or pasta topped with stewed meat, tomatoes, onions, and spices.

Uzbek cuisine is known as being meat and grain heavy. Often the only salad available is a small cucumber, tomato, and onion mix. Deserts are also sparse, but still enjoyable – tea served with fruit (fresh, stewed, or dried) and nuts and/or halva (an arabic sweet made from seeds or nuts). Halva likely originated in Iran, but is popular throughout Central Asia.

Uzbek holidays are dominated by Ramadan, New Year’s (for which Uzbeks get four days off), and Nowruz, a holiday of Zorastrain descent popular in many countries once dominated by or near to the former Persian empire.

You Might Also Like

When the Silk Road passed through Uzbekistan, its cities grew to some of the world’s largest, most prosperous, and most learned. Many of the great…

The Silk Road Railway: Will It Ever Happen?

In June 2022, the governments of China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan announced that construction on the long-awaited Silk Road Railway will begin in early 2023. A…

A Comparative Look at Coronavirus Responses in Eurasia

The global health crisis has changed life around the world, but in often very different ways in various places. Even countries located close to each…

4 Cities in Uzbekistan: One of the World’s Ancient Civilizations

Uzbekistan is a country that holds a very special place in my heart. I grew up in Uzbekistan but left due to political issues in…

Central Asia: Core and Periphery

Central Asia is, by its most common definition, those five “stans” that were formerly Soviet republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. However, this has…

About the Author

Josh Wilson

Josh has been with SRAS since 2003. He holds an M.A. in Theatre and a B.A. in History from Idaho State University, where his masters thesis was written on the political economy of Soviet-era censorship organs affecting the stage. He lived in Moscow from 2003-2022, where he ran Moscow operations for SRAS. At SRAS, Josh still assists in program development and leads our internship programs . He is also the editor-in-chief for the SRAS newsletter , the SRAS Family of Sites , and Vestnik . He has previously served as Communications Director to Bellerage Alinga and has served as a consultant or translator to several businesses and organizations with interests in Russia.

Program attended: All Programs

View all posts by: Josh Wilson

Indiana University Press

On The Site

Essays on uzbek history, culture, and language.

Preparing your PDF for download...

There was a problem with your download, please contact the server administrator.

Download/Print Leaflet

Edited by Denis Sinor

Published by: Sinor Research Institute of Inner Asian Studies

- 9780933070295

- Published: December 1993

Other Retailers:

- Barnes & Noble

- Books-A-Million

- Description