Economy Matters

Email a friend.

Annual Report

Monetary Policy

Economic Research

Banking & Finance

Regional Economics

Comm/Econ Dev

Inside the Fed

Departments

Data Digests

Financial tips, staff & credits, subscribe to e-mail updates.

Round and Round: The Basics of the Business Cycle

The word cycle contains the notion of regularity. Yet one of the most important cycles of all, the business cycle, is anything but predictable.

Plainly put, the business cycle is how economists refer to the inevitable ups—expansions— and downs—contractions, or recessions—of economic activity over time. But determining exactly when a cycle ends and when a new one begins is often not clear, even to experts, until well after the fact, economists say. What's more, though some of the effects of economic slowdowns are consistent—higher unemployment, less consumer spending, or diminished factory production, to name a few—the precise forces that cause an expansion to end can vary.

Despite plenty of statistics, tools, and models developed to track the economy, knowing exactly what might kill an expansion is elusive, says Atlanta Fed research economist Patrick Higgins , who developed the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow , a popular instrument that provides a "nowcast" of the current quarter's economic growth as measured by gross domestic product, or GDP.

"There are definitely commonalities, but there are differences as well," Higgins said of the way business cycles end.

The path from climb to descent is not always straightforward

The economy is a web of innumerable forces affecting one another in unpredictable and changing ways. Figuring it all out, solving every puzzle, is essentially impossible, economists like Higgins agree.

The path from economic growth to economic slump does not typically go A to B to C. "It's not really linear," Higgins said. "I don't know if we have a good sense of exactly what causes people to hold up on spending or investment, but afterward, you can identify things that happened."

The Atlanta Fed's Pat Higgins. Photo by David Fine

Psychology and real-world surprises contribute to downturns.

What do experts think causes economic booms to end? For many decades after World War II, there were two basic schools of thought. One side, the Keynesians—devotees of the British economist John Maynard Keynes—generally believed that a lack of confidence among consumers and the business community led them to pull back on spending and investment, thus hobbling overall economic activity. Keynes, who died at age 62 in 1946, called the psychological forces "animal spirits."

The other school of thought put more stock in "real business cycle theory," which holds that recessions are less a psychological phenomenon than they are rational responses to concrete events such as a sudden disruption—or "shock," as economists say. This could be a sudden surge in the price of an important commodity like oil, or a change to current or expected technological possibilities, or a big shift in government fiscal policy. Although the financial crisis that triggered the Great Recession would appear to fit some parts of this definition, the events surrounding it were also fueled by a pervasive lack of confidence in the ability of various institutions and individuals to meet their debt obligations.

So, broadly speaking, the pendulum appears to have swung in the direction of the "animal spirits" camp and its offshoots for now, Higgins said. As just one bit of evidence of this, a recent article in the influential British magazine The Economist said that "recessions, to no small degree, are a state of mind."

Personal consumption is most of the economy

To be sure, there is plenty we do know. Start with the basics of the business cycle.

During expansions, such as the present one the nation has enjoyed for more than 10 years, the economy is growing as measured by GDP, the basic economic yardstick that measures all the goods and services produced in the country.

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis tallies GDP each quarter. GDP's single biggest component—nearly 70 percent each year—is personal consumption, or the sum total people spend on goods and services. The next biggest categories are total fixed investment and government spending, each representing about 17 percent of GDP. Total fixed investment consists mostly of money that companies spend on machinery, buildings, software, and so on. But the category also includes investment in the construction of houses and apartment buildings. The total share of those three categories comes to more than 100 percent because net exports of goods and services as a category are subtracted from GDP. (The St. Louis Fed has a graph showing the components of GDP .)

When GDP growth slows from one quarter to the next but is still positive, that is not a recession. A standard, but unofficial, definition of a recession is when GDP falls for two straight quarters. Signs of recession show up in statistics gauging such things as industrial production (the amount of manufacturers' output), total numbers of jobs, the real income (which is adjusted for inflation) of all workers, and manufacturing and trade sales, or sales among firms.

The current economy is strong but sending mixed signals

The current expansion is the longest in the post–World War II era. But in recent months, conflicting signals have emerged about the economic outlook, as Federal Reserve officials have pointed out.

On the one hand, important economic engines including employment and consumer spending are humming along nicely. Taken as a whole, American workers' incomes have grown steadily during the past year. And although consumer confidence has ticked down, surveys show that people generally continue to feel all right about their economic prospects, a key sign that shoppers might keep spending generously.

On the other hand—as economists are prone to say—a few significant warning signs are appearing. The global economy is growing more slowly, U.S. factories are producing less, and business investment growth in capital goods like machines and software has softened. Also, interest rates on government debt—set by supply-and-demand market forces among those buying and selling the debt instruments—are showing signs that could be an indication of oncoming economic weakness. For example, the yield curve recently inverted, meaning that longer-term bonds earn a lower interest rate than shorter-term bonds.

Finally, uncertainty among business executives has been rising, according to the Atlanta Fed's Survey of Business Uncertainty . Such uncertainty tends to tap the brakes on economic growth by making companies hesitant to commit to big investments that can generate new business.

Inflation has gotten lower, business cycles longer

Part of the challenge in predicting the direction of the cycle comes from the numerous complex interactions that make up the cycle. Moreover, the forces that shape the business cycle change over time.

For example, for about 20 years starting in the mid-1960s, inflation was a huge concern. It was over 4 percent throughout much of that period, even soaring above 10 percent at times. However, that changed as the Federal Reserve began more aggressively fighting inflation. Over the past 25 years, it has averaged a bit less than 2 percent, and low inflation has been the main concern for the past decade, Fed chair Jerome Powell said in an August 23 speech .

"By the turn of the century, it was beginning to look like financial excesses and global events would pose the main threats to stability in this new era rather than overheating and rising inflation," Powell said.

Business cycles have also become longer, perhaps partly because greater economic knowledge has helped policymakers formulate monetary and fiscal policy that better nurture macroeconomic growth. Higgins points out that macroeconomic performance today is less volatile than it was from the mid-1940s to the mid-1980s.

Indeed, counting the current expansion, three of the four longest economic growth periods in U.S. history have happened since 1983, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research , the body that officially declares the beginnings and ends of recessions. Since 1945, expansions on average have lasted about six years compared to just under four years, while contractions have grown shorter.

Ultimately, nobody can say definitively when the economy will change direction. Even the best experts generally only know for sure it has turned at least half a year after it happens. The business cycle will continue to present vexing puzzles, but plenty of smart people will keep trying to solve them.

Charles Davidson

Staff writer for Economy Matters

Five questions about business cycles

- February 2001

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- The Brookings Institution

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- J ECONOMETRICS

- Publ Finance Rev

- Maria Kalli

- Gangolf Groh

- Thierry Aimar

- IMF STAFF PAPERS

- Saul J. Lizondo

- Francis X. Diebold

- J ECON PERSPECT

- A.P. Kirman

- Charles I. Plosser

- J.B. Taylor

- Edmund S. Phelps

- Benjamin Friedman

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is a Business Cycle?

- How It Works

- Measuring and Dating

- Relationship With Stock Prices

The Bottom Line

Business cycle: what it is, how to measure it, and its 4 phases.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/headshot1-6c67c442a0684de18fb605c3cd2fb176.png)

- Depression in the Economy: Definition and Example

- Economic Collapse

- Business Cycle CURRENT ARTICLE

- Boom And Bust Cycle

- Negative Growth

- What Was the Great Depression?

- Were There Any Periods of Major Deflation in U.S. History?

- The Greatest Generation

- U.S. Government Financial Bailouts

- Austerity: When the Government Tightens Its Belt

- The New Deal

- The Economic Effects of the New Deal

- Gold Reserve Act of 1934

- Emergency Banking Act of 1933

Madelyn Goodnight / Investopedia

Business cycles are a type of fluctuation found in the aggregate economic activity of a nation—a cycle that consists of expansions occurring at about the same time in many economic activities, followed by similarly general contractions. This sequence of changes is recurrent but not periodic.

The business cycle is also called the economic cycle .

Key Takeaways

- Business cycles are composed of concerted cyclical upswings and downswings in the broad measures of economic activity—output, employment, income, and sales.

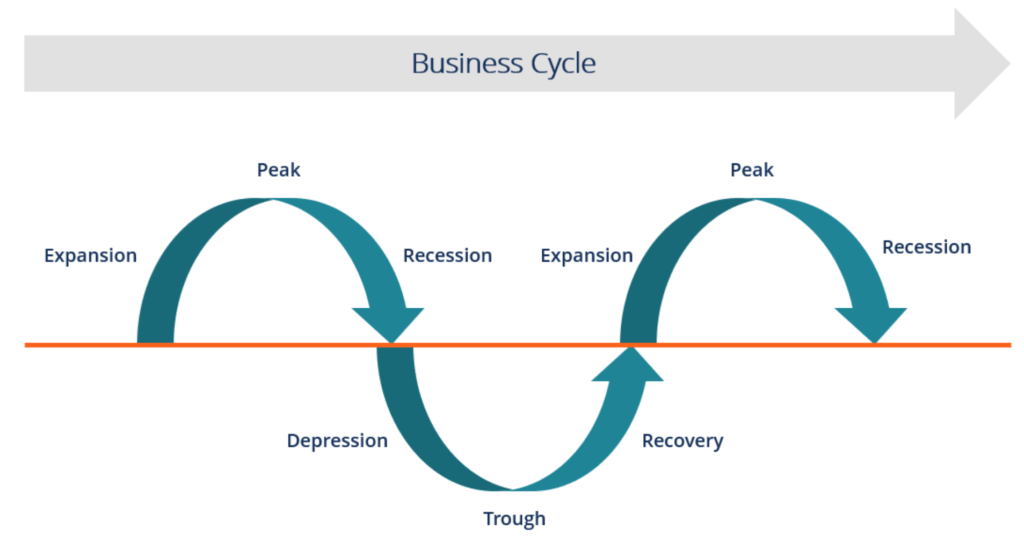

- The alternating phases of the business cycle are expansions and contractions.

- Contractions often lead to recessions, but the entire phase isn't always a recession.

- Recessions often start at the peak of the business cycle—when an expansion ends—and end at the trough of the business cycle, when the next expansion begins.

- The severity of a recession is measured by the three Ds: depth, diffusion, and duration.

Understanding the Business Cycle

In essence, business cycles are marked by the alternation of the phases of expansion and contraction in aggregate economic activity and the co-movement among economic variables in each phase of the cycle.

Aggregate economic activity is represented by not only real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) GDP —a measure of aggregate output—but also the aggregate measures of industrial production, employment, income, and sales, which are the key coincident economic indicators used for the official determination of U.S. business cycle peak and trough dates.

Popular misconceptions are that the contractionary phase is a recession and that two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP (an informal rule of thumb) means a recession.

It's important to note that recessions occur during contractions but are not always the entire contractionary phase. Also, consecutive declines in real GDP are one of the indicators used by the NBER, but it is not the definition the organization uses to determine recessionary periods.

On the flip side, a business cycle recovery begins when that recessionary vicious cycle reverses and becomes a virtuous cycle, with rising output triggering job gains, rising incomes, and increasing sales that feedback into a further rise in output .

The recovery can persist and result in a sustained economic expansion only if it becomes self-feeding, which is ensured by this domino effect driving the diffusion of the revival across the economy.

Of course, the stock market is not the economy. Therefore, the business cycle should not be confused with market cycles , which are measured using broad stock price indices.

Measuring and Dating Business Cycles

The severity of a recession is measured by the three D's: depth, diffusion, and duration. A recession's depth is determined by the magnitude of the peak-to-trough decline in the broad measures of output, employment, income, and sales.

Its diffusion is measured by the extent of its spread across economic activities, industries, and geographical regions. Its duration is determined by the time interval between the peak and the trough.

An expansion begins at the trough (or bottom) of a business cycle and continues until the next peak, while a recession starts at that peak and continues until the following trough.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) determines the business cycle chronology—the start and end dates of recessions and expansions for the United States.

Accordingly, its Business Cycle Dating Committee considers a recession to be "a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales."

The Great Depression featured many recessions, one of which lasted for 44 months.

The Dating Committee typically determines recession start and end dates long after the fact. For instance, after the end of the 2007–09 recession, it "waited to make its decision until revisions in the National Income and Product Accounts [were] released on July 30 and Aug. 27, 2010," and announced the June 2009 recession end date on Sept. 20, 2010.

U.S. expansions have lasted longer than U.S. contractions on average. Between 1945 and 2019, the average expansion lasted about 65 months. The average recession lasted approximately 11 months.

Between the 1850s and World War II, the average expansion lasted about 26 months and the average recession about 21 months. The longest expansion was from 2009 to 2020, which lasted 128 months.

Stock Prices and the Business Cycle

The biggest stock price downturns tend to occur—but not always—around business cycle downturns (e.g., contractions and recessions). For example, the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 took steep dives during the Great Recession. The Dow fell 51.1%, and the S&P 500 fell 56.8% between Oct. 9, 2007 to March 9, 2009.

There are many reasons for this, but primarily, it is because businesses assume defensive measures and investor confidence falls during contractionary periods. Many events occur before people in an economy are aware they are in a contraction, but the stock market trails what is going on in the economy.

So, if there is speculation or rumors about a recession, mass layoffs , rising unemployment, decreasing output, or other indications, businesses and investors begin to fear a recession and act accordingly. Businesses assume defensive tactics, reducing their workforces and budgeting for an environment of falling revenues.

Investors flee to investments "known" to preserve capital, demand for expansionary investments falls, and stock prices drop.

It's important to remember that while stock prices tend to fall during economic contractions, the phase does not cause stock prices to fall—fear of a recession causes them to fall.

What Are the Stages of the Business Cycle?

In general, the business cycle consists of four distinct phases: expansion, peak, contraction, and trough.

What Does a Business Cycle Describe?

A business cycle describes the fluctuations in an economy over a period of time, generally the period from the start of one recession to the start of the next. This would include periods when the economy grows.

Are Business Cycles Predictable?

Generally, business cycles are not predictable. Economies are complex machines that function in a variety of ways and are intertwined in as many ways. The ability to predict how they will move is extremely difficult. There can be signs of changes in an economy, such as changes in inflation and production, but to predict an all-out change in the business cycle is very tough if not impossible.

The business cycle is the time it takes the economy to go through all four phases of the cycle: expansion, peak, contraction, and trough. Expansions are times of increasing profits for businesses, and rising economic output, and are the phase the U.S. economy spends the most time in. Contractions are times of decreasing profits and lower output and are the phase in which the least amount of time is spent.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " All About the Business Cycle: Where Do Recessions Come From? "

The National Bureau of Economic Research. " Business Cycle Dating ."

National Bureau of Economic Research. " The NBER's Recession Dating Procedure ."

Congressional Research Service. " Introduction to U.S. Economy: The Business Cycle and Growth ," Page 1.

National Bureau of Economic Research. " Business Cycle Dating Committee, National Bureau of Economic Research ."

Congressional Research Service. " Introduction to U.S. Economy: The Business Cycle and Growth ," Page 2.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. " Stock Prices in the Financial Crisis ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1068798176-55803c0cec5c404eba646301dc660b04.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

Recent Work on Business Cycles in Historical Perspective: Review of Theories and Evidence

This survey outlines the evolution of thought leading to the rrecent delopments in the study of business cycles.The subject is almost coextensive with short-term macrodynamics and has a large interface withmeconomics of growth, money, inflation, and expectations.The coverage is therefore both very extensive , and selective. The paper first summarizes the "stylized facts" that ought to be explained by the theory.This part discusses the varying dimensions of business cycles; their timing, amplitude, and diffusion features; some international aspects; and recent changes. The next part is a review of the literature on "self-sustaining" cycles. It notes some of the older theories and proceeds to more recent models driven by changes in investment, credit, and price-cost-profit relations. These models are mainly endogenous and deterministic.Exogenous factors and stochastic elements gain importance in the part on the modern theories of cyclical response to monetary and real disturbances.The early monetarist interpretations of the cycle are followed by the newer equilibrium models with price misperceptions and intertemporal substitution of labor. Monetary shocks continue to be used but the emphasis shifts from nominal demand changes and lagged price adjustments to informational lags and supply reactions. Various problems arise, revealed by intensive testing and criticisms.This prompts new attempts to explain the persistence of'cyclical movements and the roles of uncertainty and financial instability, real shocks,and gradual price adjustments. One conclusion is that business cycle research will profit most from (a)the updating of findings from the historical and statistical studies, and (b)using the results to eliminate inconsistencies with the evidence and to move toward a realistic synthesis of the surviving elements of the extant theories.

- Acknowledgements and Disclosures

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

Published Versions

Zarnowitz, Victor. "Recent Work on Business Cycles in Historical Perspective: Review of Theories and Evidence." Journal of Economic Literature, Vol . 23, No. 2, (June 1985), pp. 523-580.

Victor Zarnowitz, 1992. "Recent Work on Business Cycles in Historical Perspective," NBER Chapters, in: Business Cycles: Theory, History, Indicators, and Forecasting, pages 20-76 National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

- Feldstein Lecture

- Presenter: Cecilia E. Rouse

- Methods Lectures

- Presenter: Susan Athey

- Panel Discussion

- Presenters: Karen Dynan , Karen Glenn, Stephen Goss, Fatih Guvenen & James Pearce

Business Cycles

Economies experience times of growth and times of recession. Learn more about these fluctuations known as business cycles.

According to a multisector DSGE model, heterogeneity in shock variances across sectors is critical for matching the empirical relationship between inflation and the distribution of relative price changes.

Alexander L. Wolman and Francisco Ruge-Murcia

The authors show that disruptions in access to corporate bond markets have an economically material, statistically significant impact on the real economy.

Nina Boyarchenko , Richard K. Crump , Anna Kovner and Or Shachar

The authors find evidence that bank capital matters for the tails of future GDP growth, with a relationship that is particularly strong in reducing the probability of the worst GDP outcomes. The relationship between bank capital and growth, however, is not strong for its central tendency.

Nina Boyarchenko , Domenico Giannone and Anna Kovner

Although the communities surrounding universities experienced some shielding effects from previous recessions, the unemployment rate actually increased in these areas following the COVID-19 recession.

Adam Scavette and Robert Calvert Jump

The authors study how changes in banks' lending standards affect economic activity, inflation, and interest rates to gain a better understanding of the macroeconomic effect that banks can have.

Elijah Broadbent , Huberto M. Ennis , Tyler J. Pike and Horacio Sapriza

Andy Bauer and Renee Haltom talk about why consumers and businesses are telling a different story about the economy than the data suggests. They also discuss how economists reconcile such differences between sentiment and data. Bauer and Haltom are regional executives at the Richmond Fed.

President Tom Barkin explores why it has been particularly challenging to predict the path of the economy over the last few years.

Tom Barkin President, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

President Tom Barkin reflects on recent data and shares his view on where the U.S. economy is headed.

Temporary losses look to be severe after the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge and closure of the Port of Baltimore, but there are several reasons to be optimistic about recovery.

Adam Scavette Regional Economist

President Tom Barkin explores different ways to look at recent data, and then gives his own perspective.

Several factors include labor market participation, business cycle volatility and responsiveness to the underlying economic environment.

Marios Karabarbounis

How has the economy navigated previous rate cycles, and how do they compare to the current one?

Erin Henry , Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte and Jack Taylor

President Tom Barkin reflects on 2023 and shares his outlook for the year ahead.

Upcoming Event: What do Uber and the Federal Reserve have in common? They both hire economists! Did you know that some of your favorite brands also hire economists? But what do economists actually do? Registration required.

President Tom Barkin shares how communities in the Fifth District are working to move the needle on housing.

President Tom Barkin explores potential paths for the U.S. economy and their implications for monetary policy.

Is it possible durable goods spending will settle above the pre-pandemic trend line? If so, what might this consumption shift mean for the aggregate economy?

John O'Trakoun Senior Policy Economist

President Tom Barkin explores what’s happening in the labor market and how it could impact the path ahead.

Out of the many components that make up the PPI, one particularly relevant item from the perspective of shoppers may be the PPI's trade indexes.

The current cycle appears to be unique in how inflation has moved during this most recent series of rate hikes.

Conner Mulloy , Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte and Erin Henry

President Tom Barkin discusses what’s driving the resilient U.S. economy and where it may be headed next.

How do state economies behave differently through the ups and downs of national business cycles? Do some states tend to enter recessions sooner (or later) than others? Are some states more recession-proof (or prone) than others?

Nicolas Morales discusses his research on supply chains and the factors that can help them resist and recover from economic shocks, like the COVID-19 pandemic. Morales is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The Richmond Fed Community Conversations team visited Wythe County to explore the region's promises and possibilities.

While auto sales have been trending up over the past several months, we'll look into a couple of reasons why the future may not be so bright.

Wage-price pass throughs may help explain why core goods inflation has risen so much faster in the current expansion than in previous ones.

Changes in unemployment appear to be strong recession predictors, especially when combined with lagged term spreads.

Andreas Hornstein

Moves toward stable inflation and maximum employment can be in conflict in the short term.

Felipe F. Schwartzman

Among the topics discussed were income growth volatility, AI's impact on productivity and how housing price changes affect young businesses.

Tim Sablik and Matthew Wells

Jason Kosakow and Santiago Pinto describe how survey data is gathered and used to assess regional and national economic conditions. Kosakow is survey director and Pinto is a senior economist and policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The lockdowns resulting from COVID-19 provide an opportunity to examine what factors affect the strength of supply chains.

Claire Conzelmann , Nicolas Morales , Gaurav Khanna and Nitya Pandalai-Nayar

Hard (or large) sovereign defaults have been associated with larger negative economic responses than soft defaults.

Brandon Fuller , Grey Gordon and Pablo Guerrón-Quintana

A new real-time measure of credit market sentiment appears to outperform credit conditions indicators currently used in the literature.

Danilo Leiva-León , Gabriel Pérez-Quirós , Horacio Sapriza , Francisco Vazquez-Grande and Egon Zakrajšek

The yield curve is often used to gauge potential recessions. Can its predictive value be improved?

While several indicators have pointed to a recent slowdown in economic activity, one that uses unemployment rates to gauge recession probabilities may offer new insights.

Sonya Ravindranath Waddell shares insights from the latest survey of chief financial officers and other financial decision-makers at companies across the United States. Waddell is a vice president and economist at the Richmond Fed.

As the Fed works to contain inflation, many ask whether we are headed into a recession. President Barkin shares his perspective.

We search for hysteresis in aggregate post-WWII U.S. data. Our findings suggest that hysteresis effects have been virtually absent for the sample excluding the financial crisis and the Great Recession, and they only appear when including the period following the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

Luca Benati and Thomas A. Lubik

Unlike in other recessions, women's labor force participation was impacted more than men's. What impact did child care have?

Kartik B. Athreya and Sierra Stoney

How did unemployment insurance expansion affect recovery from the pandemic-induced recession? What are the effects of federal minimum wage hikes? A recent research conference addressed these questions and more.

John Mullin

The unemployment rate is close to pre-pandemic lows, and job openings are at record highs. Yet, participation and employment rates are still below pre-pandemic levels.

Andreas Hornstein and Marianna Kudlyak

The recent high inflation had been due to price changes in a small group of expenditures, but that changed a few months ago.

Alexander L. Wolman

Studies suggest that short-term effects of such spending are small and long-term effects depend on an economy's sensitivity to such investment.

News about productivity shocks — even when these shocks have not even happened yet — seems to be a powerful additional source of economic fluctuations.

Thomas A. Lubik , Christoph Gortz and Christopher Gunn

Is money essential? How do self-interested parties bargain to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes? These were among questions addressed at a recent research conference.

A surge of interest in starting new businesses could reverse a long-running drought.

The Beveridge curve — which measures the inverse relationship between the unemployment and vacancy rates — has shifted significantly outward and is much steeper than in pre-COVID times.

Thomas A. Lubik

Felipe Schwartzman and Chen Yeh discuss their research on business cycles and what forces impact them on the individual and aggregate level. Schwartzman is a senior economist and Yeh is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The Fed's relatively new repo facilities may create greater price certainty, but the Fed's intervention may mute valuable market signals regarding economic efficiency and stability.

Huberto M. Ennis and Jeff Huther

Some argue that damages from climate change aren't large enough to affect the financial system, but what about amplification effects?

Unemployment insurance seems to help smooth consumer spending after a job loss, but there's disagreement on how much it discourages people from finding new jobs.

How do local government borrowing, default, and migration interact? We find in-migration results in excessive debt accumulation due to a key externality: Immigrants help repay previously issued debt.

Grey Gordon and Pablo Guerrón-Quintana

Household consumption shocks have accounted for close to 40 percent of pre-pandemic business cycle fluctuations.

Christian Matthes and Felipe F. Schwartzman

University of Texas at Austin economist on wage growth, labor's share of income, and the gender unemployment gap

David A. Price

Contrary to the traditional view, adverse events for a single firm can affect the economy as a whole, if the firm is large enough.

Without a recent directly comparable episode, economic forecasters modified their models or sought additional information in data to create forecasts during the pandemic.

Recent legislation has again highlighted the U.S. welfare system. This EB summarizes the welfare system and a "work bias" embedded in many U.S. welfare programs.

Claudia Macaluso

Conducting a statistical analysis of U.S. economic data, economists from the Richmond Fed and the University of Bern find no evidence of hysteresis, the idea that seemingly temporary economic shocks can have permanent effects.

Households' expectations often differ from formal economic forecasts. The researchers quantify these differences and explain them by developing a "theory of time-varying pessimism." Embedding their new theory into a quantitative economic model, they find that fluctuations in pessimism have significant effects on macroeconomic measures, most notably the unemployment rate.

Anmol Bhandari , Jaroslav Borovicka and Paul Ho

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused severe economic distress in the Fifth District, but the regional housing market has proven remarkably resilient.

Benjamin Lukas Intern (2020)

Much of the previous economic research on the aftermath of recessions has focused on their short-term effects on earnings and jobs. New research suggests that with longer-term consequences, workers' earnings, health and family outcomes may be affected.

Emily Green

This paper identifies total factor productivity (TFP) news shocks using standard VAR methodology and documents a new stylized fact: in response to news about future increases in TFP, inventories rise and comove positively with other major macroeconomic aggregates.

Christoph Gortz , Christopher Gunn and Thomas A. Lubik

There is enough research to suggest that sentiment does play a role in shaping the business cycle. The question facing policymakers is what to do about it.

Richmond Fed president Tom Barkin discusses economic conditions and the potential for a recession.

What caused the housing boom and bust of the early 2000s?

Daisuke Ikeda , Toan Phan and Tim Sablik

This Economic Brief evaluates the predictive capabilities of the yield curve and several other leading indicators, including the Conference Board Leading Economic Index (LEI), claims for unemployment insurance, manufacturing activity, consumer lending, and CEO optimism.

Matthew Murphy , Jessie Romero and Roy H. Webb

This brief makes the case that research and policy should focus on four aspects of economic fluctuations: a short-term component (cycles of less than two years), a business cycle component (cycles between two and eight years), a medium-term component (cycles up to thirty-two years), and a long-term component (the trend).

Renee Haltom , Thomas A. Lubik , Christian Matthes and Fabio Verona

The recent flattening of the yield curve has raised concerns that a recession is around the corner. Such concerns stem partly from the fact that yield curve inversions have preceded each of the past seven recessions.

Renee Haltom , Elaine Wissuchek and Alexander L. Wolman

Small banks do, in fact, play a special role in the intermediation of credit in the U.S. economy. But when the cyclical properties of NIM are decomposed into the asset and liability sides of the balance sheet, it appears that the liability side drives the difference in the performance of small and large banks.

Borys Grochulski , Daniel Schwam , Aaron Steelman and Yuzhe Zhang

A downturn following the collapse of an asset bubble — an episode of speculative booms in asset prices — can be severe and sustained, with output and employment often lower than in the prebubble economy. This Economic Brief considers some possible theoretical explanations.

Helen Fessenden and Toan Phan

Economic growth in the United States following the Great Recession has been well below the post-World War II average. Some observers have called this the "new normal."

Aaron Steelman and John A. Weinberg

Real business cycle (RBC) models have been highly successful at explaining business cycles that occurred before 1984. But since then, shifts in comovements and relative volatilities of key economic aggregates have challenged their preeminence.

Thomas A. Lubik , Karl Rhodes , Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte and Felipe F. Schwartzman

Are the majority of inner cities experiencing a renaissance thanks to rapid gentrification, or is growth limited to a small number of high-technology regions, resulting in inequality among metropolitan areas?

Aggregate demand is the total demand for all goods and services in an economy. Should the government try to boost it with fiscal stimulus during recessions?

Renee Haltom Vice President and Regional Executive

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker addressed the Global Interdependence Center in Sarasota, Florida.

Jeffrey M. Lacker President, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey Lacker addressed the Greater Richmond Chamber of Commerce.

Stanford University economist on the effects of economic uncertainty, the role of management practices in economic performance, and fostering good management

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker addressed business leaders during a luncheon hosted by the Rotary Club of Charlotte in Charlotte, N.C.

Andreas Hornstein , Marianna Kudlyak , Fabian Lange and Tim Sablik

This paper studies equilibrium pricing in a product market for an indivisible good where buyers search for sellers.

Guido Menzio and Nicholas Trachter

In this paper, we show that variations in the discount factor estimated using inventories correlate well with established independent measures of credit market frictions.

Thomas A. Lubik , Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte and Felipe F. Schwartzman

The Richmond Fed conducts monthly surveys of business conditions in the manufacturing and service sectors of the Fifth Federal Reserve District. This article provides background information on these surveys and on other manufacturing and service sector surveys.

David A. Price and Aileen Watson

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke about the economic outlook Jan. 17, 2014, in remarks to the Richmond chapter of the Risk Management Association.

In this paper we ask how uncertainty about fiscal policy affects the impact of fiscal policy changes on the economy when the government tries to counteract a deep recession.

Christian Matthes and Josef Hollmayr

We study the impact of intersectoral and interregional trade linkages in propagating disaggregated productivity changes to the rest of the economy.

Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte , Esteban Rossi-Hansberg , Fernando Parro and Lorenzo Caliendo

In a stylized quantitative analysis, we show that the consumption effect dominates, so that unemployment benefits increase per-worker productivity. We also analyze the welfare-maximizing benefit level and find that it decreases as moving costs increase.

David L. Fuller , Marianna Kudlyak and Damba Lkhagvasuren

We study the sovereign debt duration chosen by the government in the context of a standard model of sovereign default.

Juan Carlos Hatchondo and Leonardo Martinez

Robert L. Hetzel

A new database of online job posting data sheds light on how workers search for jobs.

Marianna Kudlyak and Jessie Romero

This paper provides a theoretical framework to quantitatively investigate the optimal accumulation of international reserves to hedge against rollover risk.

Javier Bianchi , Juan Carlos Hatchondo and Leonardo Martinez

In view of the increasing share of long-term unemployment since the 2007-09 recession, we provide an extension of the Shimer (2012) unemployment accounting scheme that allows for both short-term and long-term unemployment and that uses data on the duration distribution of unemployment.

Marianna Kudlyak and David A. Price

We show that, whereas during earlier recessions it was sufficient to examine the flows between employment and unemployment to account for the dynamics of the unemployment rate, this was not true in the Great Recession.

Marianna Kudlyak and Felipe F. Schwartzman

Marianna Kudlyak , Damba Lkhagvasuren and Roman Sysuyev

This paper examines the optimality of fiscal rules and measures their aggregate effects using a baseline sovereign default framework.

Juan Carlos Hatchondo , Leonardo Martinez and Francisco Roch

As households strengthen their balance sheets, their ability to take on new debt to finance consumption is improving, but household debt remains elevated by historical standards, and other determinants of consumer spending remain weak.

R. Andrew Bauer and Betty Joyce Nash

Juan Carlos Hatchondo , David A. Price and Jonathan Tompkins

Robert Schnorbus and Judy Cox

Andreas Hornstein , Thomas A. Lubik and Jessie Romero

Yongsung Chang and Andreas Hornstein

Lacker Addresses Dulles Regional Chamber of Commerce, Chantilly, Va.

Lacker speaks at Southern Growth's 2011 Chairman's Conference in Roanoke, Va.

Since the recession started in 2007, there has been a growing concern that small businesses may lack adequate access to credit. This Economic Brief examines the complexity of small business credit issues.

Betty Joyce Nash and Kimberly Zeuli

Robert Schnorbus and Aileen Watson

Marianna Kudlyak , David A. Price and Juan M. Sanchez

President Lacker Addresses Piedmont, N.C.'s Business Leaders

Marianna Kudlyak

Michael U. Krause and Thomas A. Lubik

Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte

Juan Carlos Hatchondo , Leonardo Martinez and Cesar Sosa Padilla

Lacker Addresses Greensboro, NC Business Leaders

Juan Carlos Hatchondo , Leonardo Martinez and Horacio Sapriza

Marianna Kudlyak , Devin Reilly and Stephen Slivinski

Thomas A. Lubik and Wing Leong Teo

President Lacker addresses the Maryland Bankers Association

Thomas A. Lubik and Stephen Slivinski

Cover Story: The Price is Right? Has the financial crisis provided a fatal blow to the efficient market hypothesis?

President Lacker addresses Charlotte business leaders

Cover Story: Measuring Quality of Life: How should we assess improvements to our standard of living?

Economists and policymakers often use average income as a way to gauge a country's "standard of living." But income alone doesn't capture overall quality of life. Should policymakers use other measures — including health, education, and even aggregate happiness — when making economic policy? Related Links

Lacker addresses VA House Appropriations Committee

Existing policies to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) largely have been structured to subsidize alternative energy technologies. Yet these policies are likely not to be as useful as ones that target CO2 emissions directly, such as an emissions tax or a "cap and trade" program.

Kartik B. Athreya and Renee Haltom

Lacker Speech to Charlotte RMA (Video Available)

Cover Story: Reforming the Raters: Can regulatory reforms adequately realign the incentives of credit rating agencies?

Lacker Speaks to Danville Chamber of Commerce

It is widely believed that public sector spending and investment can restore aggregate economic activity to efficient levels. But some policy responses are likely to be more successful than others.

Lacker Speaks at North Carolina Senate Appropriations Committee

Lacker Speaks at Beijing Banking Summit

President Lacker speaks to Charlottesville, Va., business leaders

President Jeffrey Lacker speaks to the Charleston Metro Chamber of Commerce.

President Lacker addresses the National Association for Business Economics at the 2009 Washington Economic Policy Conference

In this paper we develop a quantitative dynamic stochastic small open economy model with incomplete markets, endogenous fiscal policy and sovereign default where public expenditures and tax rates are optimally procyclical.

Gabriel Cuadra , Juan M. Sanchez and Horacio Sapriza

President Lacker addresses the Risk Management Association, Richmond Chapter

President Lacker speaks to the Maryland Bankers Association.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke December 3, 2008, at the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce Economic Outlook Conference in Charlotte, N.C.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke at the November 21, 2008 meeting of The Tech Council of Maryland in Bethesda, Md.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke November 18, 2008 at the CATO Institute's 26th Annual Monetary Conference in Washington, D.C.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke at the Global Interdependence Center Conference held November 3, 2008 at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke June 5, 2008 at the Distinguished Speakers Seminar European Economics and Financial Centre, London, England.

Michael U. Krause , David Lopez-Salido and Thomas A. Lubik

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke February 5, 2008 to the West Virginia Bankers Association and the Community Bankers of West Virginia in Charleston, W.Va.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke January 18, 2008 to the Risk Management Association in Richmond, Va.

Thomas A. Lubik and Paolo Surico

A. Andrew John and Alexander L. Wolman

It's a pleasure to be here today and to have this opportunity to comment on conducting monetary policy in a low inflation environment.

J. Alfred Broaddus President

Reviews the Bank's operations and includes the article entitled "Accounting for Corporate Behavior"

Marvin Goodfriend and Robert G. King

Business Cycle

A series of expansion and contraction in economic activity

What is a Business Cycle?

A business cycle is a cycle of fluctuations in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) around its long-term natural growth rate. It explains the expansion and contraction in economic activity that an economy experiences over time.

A business cycle is completed when it goes through a single boom and a single contraction in sequence. The time period to complete this sequence is called the length of the business cycle.

A boom is characterized by a period of rapid economic growth, whereas a period of relatively stagnated economic growth is a recession. These are measured in terms of the growth of the real GDP, which is inflation-adjusted.

Stages of the Business Cycle

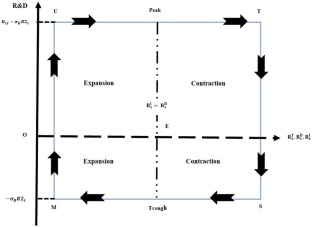

In the diagram above, the straight line in the middle is the steady growth line. The business cycle moves about the line. Below is a more detailed description of each stage in the business cycle:

1. Expansion

The first stage in the business cycle is expansion. In this stage, there is an increase in positive economic indicators such as employment, income, output, wages, profits, demand, and supply of goods and services. Debtors are generally paying their debts on time, the velocity of the money supply is high, and investment is high. This process continues as long as economic conditions are favorable for expansion.

The economy then reaches a saturation point, or peak, which is the second stage of the business cycle. The maximum limit of growth is attained. The economic indicators do not grow further and are at their highest. Prices are at their peak. This stage marks the reversal point in the trend of economic growth. Consumers tend to restructure their budgets at this point.

3. Recession

The recession is the stage that follows the peak phase. The demand for goods and services starts declining rapidly and steadily in this phase. Producers do not notice the decrease in demand instantly and go on producing, which creates a situation of excess supply in the market. Prices tend to fall. All positive economic indicators such as income, output, wages, etc., consequently start to fall.

4. Depression

There is a commensurate rise in unemployment. The growth in the economy continues to decline, and as this falls below the steady growth line, the stage is called a depression.

In the depression stage, the economy’s growth rate becomes negative. There is further decline until the prices of factors, as well as the demand and supply of goods and services, contract to reach their lowest point. The economy eventually reaches the trough. It is the negative saturation point for an economy. There is extensive depletion of national income and expenditure.

6. Recovery

After the trough, the economy moves to the stage of recovery. In this phase, there is a turnaround in the economy, and it begins to recover from the negative growth rate. Demand starts to pick up due to low prices and, consequently, supply begins to increase. The population develops a positive attitude towards investment and employment and production starts increasing.

Employment begins to rise and, due to accumulated cash balances with the bankers, lending also shows positive signals. In this phase, depreciated capital is replaced, leading to new investments in the production process. Recovery continues until the economy returns to steady growth levels.

This completes one full business cycle of boom and contraction. The extreme points are the peak and the trough.

Explanations by Economists

John Keynes explains the occurrence of business cycles is a result of fluctuations in aggregate demand, which bring the economy to short-term equilibriums that are different from a full-employment equilibrium.

Keynesian models do not necessarily indicate periodic business cycles but imply cyclical responses to shocks via multipliers. The extent of these fluctuations depends on the levels of investment, for that determines the level of aggregate output.

In contrast, economists like Finn E. Kydland and Edward C. Prescott, who are associated with the Chicago School of Economics, challenge the Keynesian theories. They consider the fluctuations in the growth of an economy not to be a result of monetary shocks, but a result of technology shocks, such as innovation.

Additional Resources

Thank you for reading CFI’s guide to Business Cycle. To learn more, check out these additional CFI resources:

- Free Economics for Capital Markets Course

- Law of Supply

- Normative Economics

- Cyclical Unemployment

- Inelastic Demand

- See all economics resources

- Share this article

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Advertisement

Business Cycles and the Dynamics of Innovation: a Theoretical Perspective

- Published: 04 March 2023

- Volume 15 , pages 1418–1436, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Manzoor Ahmad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5858-6994 1 ,

- Zahoor Ul Haq 1 &

- Shehzad Khan 2

687 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

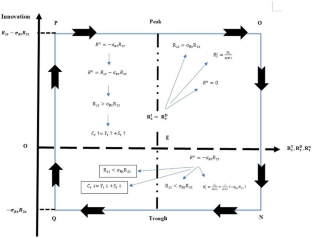

This paper constructs a simple dynamic growth model and deducts four theoretical predictions: prediction I , new knowledge creations and research and development expenditures (R&DE) contribute to economic upturns and downturns; prediction II , the R&DE and new knowledge creations upsurge and fall in the economic expansions and contractions periods, respectively; prediction III , the research intensity and frequency of new knowledge creations increase and reduce during boom and recession periods, respectively; prediction IV , positive and negative shocks in R&DE and new knowledge creation are caused by changes in consumption, saving, R&DE, and innovation activities during economic boom and slump periods; and prediction IV , innovation and gross domestic product have a bidirectional causal nexus during trade cycles.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Source: Ahmad and Zheng ( 2022 )

Similar content being viewed by others

Technological Revolutions and Economic Development: Endogenous and Exogenous Fluctuations

The Cyclical and Nonlinear Impact of R&D and Innovation Activities on Economic Growth in OECD Economies: a New Perspective

Dating the Business Cycles: Research and Development (R&D) Expenditures and New Knowledge Creation in OECD Economies over the Business Cycles

Aghion, P, & Howitt, P. W. (2008). The economics of growth . MIT Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=B9vxCwAAQBAJ

Aghion, P., Askenazy, P., Berman, N., Cette, G., & Eymard, L. (2012). Credit constraints and the cyclicality of r&d investment: Evidence from France. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10 (5), 1001–1024. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01093.x

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad, M., Khan, Z., Rahman, Z. U., Khattak, S. I., & Khan, Z. U. (2021). Can innovation shocks determine CO2 emissions (CO2e) in the OECD economies? A new perspective. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 30 (1), 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2019.1684643

Ahmad, M., & Zheng, J. (2022). The cyclical and nonlinear impact of R&D and innovation activities on economic growth in OECD economies: A new perspective. Journal of the Knowledge Economy . https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00887-7

Anzoategui, D., Comin, D., Gertler, M., & Martinez, J. (2019). Endogenous technology adoption and R&D as sources of business cycle persistence. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 11 (3), 67–110.

Google Scholar

Archibugi, D., & Filippetti, A. (2013). Innovation and economic crisis: Lessons and prospects from the economic downturn . Taylor & Francis. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=iIioAgAAQBAJ

Arndt, J. (1983). The political economy paradigm: foundation for theory building in marketing. Journal of marketing, 47 (4), 44–54. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002224298304700406?journalCode=jmxa

Arnold, L. G. (2006). The dynamics of the Jones R&D growth model. Review of Economic Dynamics, 9 (1), 143–152.

Arrow, K. J. (1972). Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention. In Readings in industrial economics (pp. 219–236). Springer.

Ayres, R. U., & Warr, B. (2010). The economic growth engine: How energy and work drive material prosperity . Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bahamas. (1984). Estimating expenditure on gross domestic product for the Bahamas, 1980–1982 . Department of Statistics. https://books.google.com/books?id=IS9rI1m4PUoC

Barlevy, G. (2007). On the cyclically of research and development. In American Economic Review (Vol. 97, Issue 4, pp. 1131–1164). https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.4.1131

Bayarcelik, E. B., & Taşel, F. (2012). Research and development: Source of economic growth. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58 , 744–753.

Beneito, P., Rochina-Barrachina, M. E., & Sanchis-Llopis, A. (2015). Ownership and the cyclicality of firms’ R&D investment. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11 (2), 343–359.

Bernstein, J. I., & Mamuneas, T. P. (2005). Depreciation estimation, R&D capital stock, and North American manufacturing productivity growth. Annales d’Économie et de Statistique , 383–404.

Castellacci, F. (2007). Evolutionary and new growth theories. Are they converging? Journal of Economic Surveys , 21 (3), 585–627.

Colander, D. C. (2003). Macroeconomics . McGraw-Hill/Irwin. https://books.google.com/books?id=AIoeHbH1QhgC

Comin, D. (2004). R&D: A small contribution to productivity growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 9 (4), 391–421.

Diacon, P. -E., & Maha, L. -G. (2015). The relationship between income, consumption and GDP: A time series, cross-country analysis. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23 , 1535–1543.

Downing, D., & Clark, J. (1992). Business statistics . Barron’s Educational Series. https://books.google.com/books?id=oRNq4rTTHb8C

Fabrizio, K. R., & Tsolmon, U. (2014). An empirical examination of the procyclicality of R&D investment and innovation. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96 (4), 662–675. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00412

Francois, P., & Lloyd-Ellis, H. (2009). Schumpeterian cycles with pro-cyclical R&D. Review of Economic Dynamics, 12 (4), 567–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RED.2009.02.004

Francois, P., & Lloyd-Ellis, H. (2008). Implementation cycles, investment, and growth. International Economic Review, 49 (3), 901–942.

Gabrovski, M. (2020). Simultaneous innovation and the cyclicality of R&D. Review of Economic Dynamics, 36 , 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2019.09.002

Glanville, A., & Glanville, J. (2011). Economics from a global perspective . Glanville Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=tV7jEjMU4QcC

Grabowski, R. (1999). Pathways to economic development . Edward Elgar. https://books.google.com/books?id=JHC4AAAAIAAJ

Guellec, D., & Ioannidis, E. (1997). Causes of fluctuations in R&D expenditures-A quantitative analysis. OECD Economic Studies , 123–138.

Gupta, K. R. (2009). Economics of development and planning (Issue v. 1). Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=ULJTAsND2zgC

Ha, J., & Howitt, P. (2007). Accounting for trends in productivity and R&D: A Schumpeterian critique of semi-endogenous growth theory. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 39 , 733–774.

Hanusch, H., & Pyka, A. (2007). Elgar companion to neo-Schumpeterian economics . Edward Elgar. https://books.google.com/books?id=P0zUrTYpMnkC

Harashima, T. (2005). The pro-cyclical R&D puzzle: Technology shocks and pro-cyclical R&D expenditure. Macroeconomics .

Hottenrott, H., & Zhang, T. (2015). On the cyclicality of R&D investments in the presence of financial constraints and R&D subsidies .

Jones, C. I., & Vollrath, D. (2013). Introduction to economic growth . https://books.google.com/books?id=cQPQLwEACAAJ&dq=Introduction+to+Economic+Growth&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwifwKmx99TgAhUQCewKHXIsBCIQ6AEINDAC

Jones, C. I., & Williams, J. C. (2000). Too much of a good thing? The economics of investment in R&D. Journal of Economic Growth, 5 (1), 65–85.

Kabukcuoglu, Z. (2019). The cyclical behavior of R&D investment during the Great recession. Empirical Economics, 56 (1), 301–323.

Kirchhoff, B. A. (1994). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capitalism: The economics of business firm formation and growth . Praeger. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=_aVSzzMOUTEC

Kiselakova, D., Sofrankova, B., Cabinova, V., Onuferova, E., & Soltesova, J. (2018). The impact of R&D expenditure on the development of global competitiveness within the CEE EU countries. Journal of Competitiveness, 10 (3), 34–50.

Konstantakis, K. N., & Michaelides, P. G. (2017). Does technology cause business cycles in the USA? A Schumpeter-inspired approach. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 43 , 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2017.05.005

Levacic, R. (1976). Macroeconomics: The static and dynamic analysis of a monetary economy . Macmillan. https://books.google.com/books?id=9Bm3AAAAIAAJ

López García, P., Montero Montero, J. M., & Moral Benito, E. (2012). Business cycles and investment in intangibles: Evidence from Spanish firms. Documentos de Trabajo/Banco de España, 1219 .

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22 (1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

Mand, M. (2019). On the cyclicality of R&D activities. Journal of Macroeconomics, 59 , 38–58.

Marcelino-Jesus, E., Sarraipa, J., Beça, M., & Jardim-Goncalves, R. (2017). A framework for technological research results assessment. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing, 30 (1), 44–62.

Matsuyama, K. (1999). Growing through cycles. Econometrica, 67 (2), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00021

Miller, R. L. R., Hornsby, & Clegg, N. W. (1999). Economics today: Macro view . Addison-Wesley Longman, Incorporated. https://books.google.com/books?id=J5uUCMX2yecC

Nafziger, E. W. (2012). Economic development . Cambridge University Press. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=bGxVzEdae7UC

Nuño, G. (2011). Optimal research and development and the cost of business cycles. Journal of Economic Growth, 16 (3), 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-011-9063-4

OECD. (2018). Growth: Rationale for an innovation strategy. 2007. Availabe from https://www.OECD.org/Site/Innovationstrategy/Readingmaterial.htm

Ouyang, M. (2011). On the cyclicality of R&D. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93 (2), 542–553. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00076

Pansera, M., & Owen, R. (2019). Innovation and development: The politics at the bottom of the pyramid . Wiley. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=UMt7DwAAQBAJ

Parkes, H. B., Parkes, & Bamford, H. (1943). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. By Joseph A. Schumpeter. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1942. Pp. x, 381. $3.50. The Journal of Economic History , 3 (02), 238–239. https://econpapers.repec.org/article/cupjechis/v_3a3_3ay_3a1943_3ai_3a02_3ap_3a238-239_5f08.htm

Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94 (5), 1002–1037. https://doi.org/10.1086/261420

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of political Economy, 98 (5), 71–102. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1506720

Romer, P. M. (1994). The origins of endogenous growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8 (1), 3–22.

Root, F. R. (1984). International trade & investment . South-Western Publishing Company. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=pzQFAQAAIAAJ

Ruttan, V. W. (2003). Social science knowledge and economic development: An institutional design perspective . University of Michigan Press.

Saeed, K. (2019). Towards sustainable development: Essays on system analysis of national policy . Taylor \& Francis. https://books.google.com/books?id=bPODDwAAQBAJ

Samuelson, P. A. (2010). Economics . Tata McGraw Hill. https://books.google.com/books?id=gzqXdHXxxeAC

Schiller, B. R. (2005). The macro economy today with discoverecon with Solman videos . McGraw-Hill Higher Education. https://books.google.com/books?id=%5C_-Oc02aqjJQC

Schmookler, J. (1966). Invention and business growth . MA, Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Schot, J., & Steinmueller, W. E. (2018). Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy , 47 (9), 1554–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011

Schumpeter, J. (1911). The theory of economic development . Harvard University Press.

Schumpeter, J. (1939). Business cycles: A theoretical, historical and statistical analysis of the capitalist process . McGraw-Hill Book company Inc.

Schumpeter, J. (1942). Creative destruction. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 825 , 82–85.

Sengupta, J. (2013). Theory of innovation: A new paradigm of growth . Springer International Publishing. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=LTgnAQAAQBAJ

Shinagawa, S. (2013). Endogenous fluctuations with procyclical R&D. Economic Modelling, 30 , 274–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONMOD.2012.09.024

Shleifer, A. (1986). Implementation cycles. Journal of Political Economy, 94 (6), 1163–1190.

Sokolov-Mladenović, S., Cvetanović, S., & Mladenović, I. (2016). R&D expenditure and economic growth: EU28 evidence for the period 2002–2012. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 29 (1), 1005–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2016.1211948

Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70 (1), 65–94.

Solow, R. M. (1957). Technical change and the aggregate production function. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 39 (3), 312. https://doi.org/10.2307/1926047

Szarowská, I. (2017). Does public R&D expenditure matter for economic growth? Journal of International Studies , 10 (2).

Tachi, R., & Walker, R. (1993). The contemporary Japanese economy: An overview . University of Tokyo Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=8FkU46ZQX6QC

Tucker, I. B. (2001). Survey of economics . South-Western College Pub. https://books.google.com/books?id=b156VLO24TcC

Wälde, K. (2002). The economic determinants of technology shocks in a real business cycle model. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 27 (1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1889(01)00018-5

Wälde, K. (2005). Endogenous growth cycles. International Economic Review , 46 (3), 867–894. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3663496

Wood, D., & Wood, D. C. (2010). Economic action in theory and practice: Anthropological investigations . Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=Hs6x76L2EJ8C

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Pakhtunkhwa Economic Policy Research Institute (PEPRI), Faculty of Business and Economics, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Mardan, Pakistan

Manzoor Ahmad & Zahoor Ul Haq

Institute of Business Studies and Leadership, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Mardan, Pakistan

Shehzad Khan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Manzoor Ahmad .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ahmad, M., Haq, Z.U. & Khan, S. Business Cycles and the Dynamics of Innovation: a Theoretical Perspective. J Knowl Econ 15 , 1418–1436 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01155-6

Download citation

Received : 09 October 2021

Accepted : 21 February 2023

Published : 04 March 2023

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01155-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- R&D expenditures

- Technological innovation

- Business cycles

- Economic growth

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Amendment 54: D.9 NuSTAR Phase-1 Proposal Due Date Moved up to January 29, 2025, and Other Changes

NuSTAR General Observer - Cycle 11 (D.9 NuSTAR) solicits proposals for basic research relevant to the NuSTAR mission. NuSTAR Cycle 11 will commence on or about June 1, 2025, and last for a nominal period of 12 months, subject to the mission being extended beyond September 2025 by Astrophysics Senior Review. Further details on the Cycle 11 program may be found at http://nustar.gsfc.nasa.gov . Funding for investigations selected under D.9 NuSTAR is available only to individuals at U.S. institutions who are identified as Principal Investigators (PIs). U.S.-based Co-Investigators on non-U.S.-led proposals are not eligible for funding.

ROSES-2024 Amendment 54 moves up the Phase-1 proposal due date for D.9 NuSTAR earlier to January 29, 2025, and makes several changes to the text: Information about NuSTAR observing time available through the IXPE GO program has been added in Sections 1.1, 1.3, and 1.3.4. NuSTAR Cycle 11 observing time available for ToO proposals has been increased to 1.5 Ms, see Section 1.3.4. A small change was also made to Section 2.1. New text is in bold and deleted text is struck through.

On or about September 27 2024, this Amendment to the NASA Research Announcement "Research Opportunities in Space and Earth Sciences (ROSES) 2024" (NNH24ZDA001N) will be posted on the NASA research opportunity homepage at https://solicitation.nasaprs.com/ROSES2024

Technical questions concerning D.9 NuSTAR may be directed to Tod Strohmayer at [email protected] . Programmatic information may be obtained from Hashima Hasan at [email protected] .

Explore More

Hubble Captures Stellar Nurseries in a Majestic Spiral

NASA’s Hubble Finds that a Black Hole Beam Promotes Stellar Eruptions

NASA’s Artemis Science Instrument Gets Tested in Moon-Like Sandbox

Scientists and engineers tested NASA’s LEMS (Lunar Environment Monitoring Station) instrument suite in a “sandbox” of simulated Moon "soil."

Discover More Topics From NASA

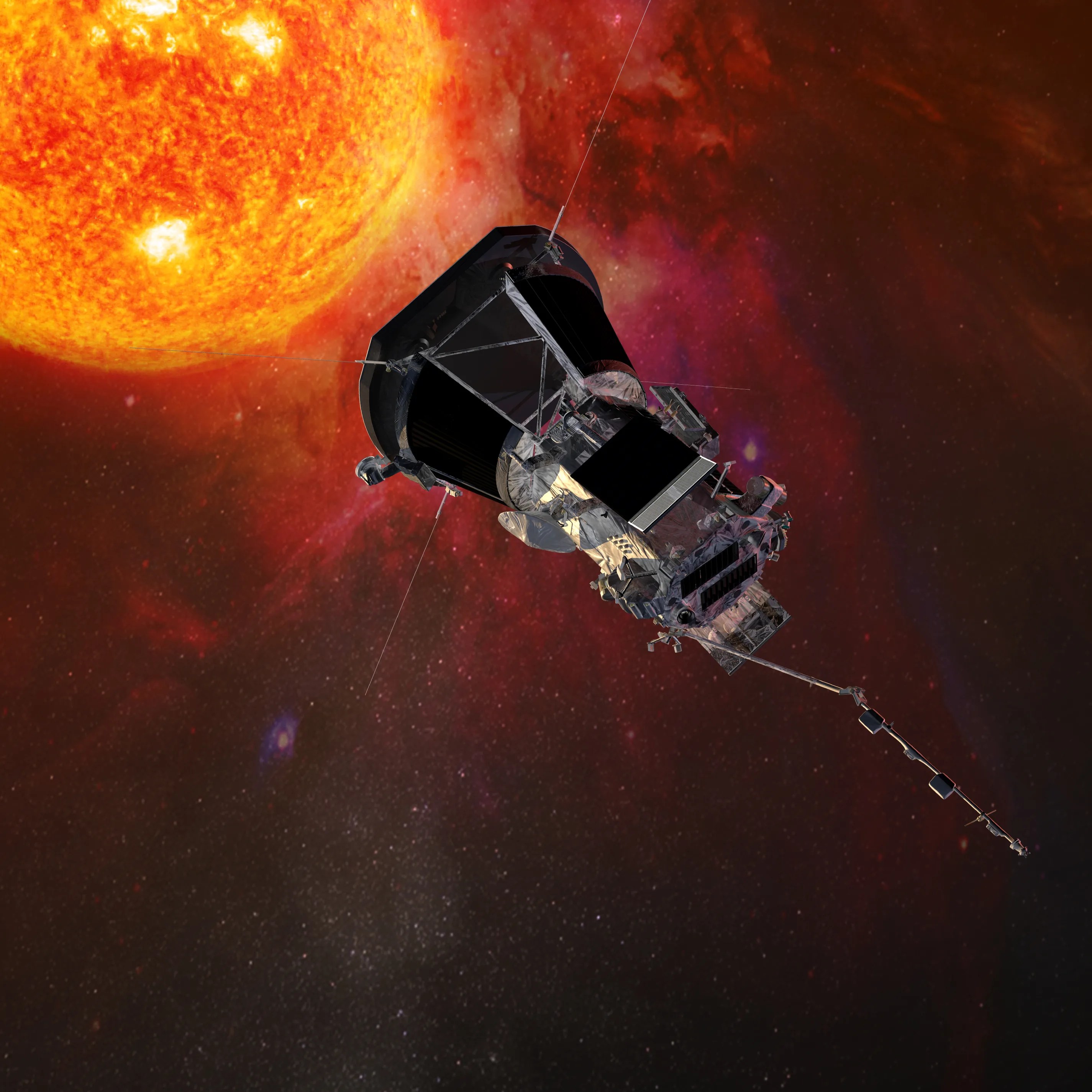

Perseverance Rover

Parker Solar Probe

COMMENTS

Overview. Journal of Business Cycle Research is dedicated to theoretical and empirical aspects of economic fluctuations. An international journal focused on economic tendency and business cycle research. Provides insights into research related to short- to medium-term economic growth.

Business Cycle Synchronization in the EU: A Regional-Sectoral Look through Soft-Clustering and Wavelet Decomposition. Saulius Jokubaitis. Dmitrij Celov. Research Paper 10 December 2023 Pages: 311 - 371.

Inflation has gotten lower, business cycles longer. Part of the challenge in predicting the direction of the cycle comes from the numerous complex interactions that make up the cycle. Moreover, the forces that shape the business cycle change over time. For example, for about 20 years starting in the mid-1960s, inflation was a huge concern.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the topic of nonlinear dynamics in economics which encompasses the definition of business cycles, a historical overview of the research, some well known models on business cycles such as the ones by Goodwin, Kalecky and Kaldor and, finally, a brief description of dynamic stochastic general ...

Explore the latest full-text research PDFs, articles, conference papers, preprints and more on BUSINESS CYCLES. Find methods information, sources, references or conduct a literature review on ...

In subject area: Social Sciences. Business Cycle Research is defined as the study that focuses on how monetary and fiscal policies impact inflation by analyzing key economic time series. It involves compiling data on market value of government liabilities, debt structures, primary surpluses, and discount rates to understand policy interactions ...

Founded in 1920, the NBER is a private, non-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to conducting economic research and to disseminating research findings among academics, public policy makers, and business professionals.

Decades of research on business cycle effects on consumer behavior have led to a diverse, yet scattered body of knowledge. To lay a foundation for moving the field forward, we conduct a semisystematic literature review and differentiate the literature based on (1) behavioral foci studied and (2) underlying theoretical assumptions made. Our ...

Founded in 1920, the NBER is a private, non-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to conducting economic research and to disseminating research findings among academics, public policy makers, and business professionals.

Abstract. This article considers five broad questions about the fundamental nature of business cycles and surveys relevant recent research. It is a slightly revised version of the introductory ...

by David Lopez-Salido, Jeremy C. Stein, and Egon Zakrajsek. Using United States data from 1929 to 2013, Jeremy C. Stein and colleagues emphasize the role of credit-market sentiment as an important driver of the business cycle. 1. HBS Working Knowledge: Business Research for Business Leaders.

The first month of a recession is the month following a peak. Table 3 notes that the business cycle peaked in February 2020, which means the COVID-19 recession started in March 2020. That recession ended in April 2020, the date of the trough. 6 The next expansion began in May 2020.

2.2 Literature on the Causes of Business Cycles. Theories on business cycles (for a review see Semmler [], Hillinger [], Zarnowitz [], Mullineux [] and Cooley []) study volatility of economies and may differ from each other depending on: 1. Their ability to explain cycles without having to rely on outside forces/shocks. They are called endogenous.By contrast, exogenous business cycle theories ...

Lakshman Achuthan is the co-founder of the Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI). Achuthan has nearly 30 years of experience analyzing business cycles, and has been regularly featured in the ...

Victor Zarnowitz, 1992. "Recent Work on Business Cycles in Historical Perspective," NBER Chapters, in: Business Cycles: Theory, History, Indicators, and Forecasting, pages 20-76 National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Founded in 1920, the NBER is a private, non-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to conducting economic research and ...

The business cycle framework was established by economists to study the ups and downs in economic activity. In the early 20th century, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) was one of the first organizations to establish a research program on the measurement and analysis of market fluctuations.

Among the topics discussed were income growth volatility, AI's impact on productivity and how housing price changes affect young businesses. ... Felipe Schwartzman and Chen Yeh discuss their research on business cycles and what forces impact them on the individual and aggregate level. Schwartzman is a senior economist and Yeh is an economist at ...

The question of whole-cycle duration dependence is one way of asking whether business cycles are periodic. Business cycle periodicity often refers to a regularity in time intervals between similar phases of the business cycle.14 The existence of such periodicity has long been de-bated.

A business cycle is a cycle of fluctuations in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) around its long-term natural growth rate. It explains the expansion and contraction in economic activity that an economy experiences over time. A business cycle is completed when it goes through a single boom and a single contraction in sequence.

The Journal of Business Cycle Research promotes the exchange of knowledge and information on theoretical and empirical aspects of economic fluctuations. The range of topics encompasses the methods, analysis, measurement, modeling, monitoring, or forecasting of cyclical fluctuations including but not limited to: business cycles, financial cycles, credit cycles, price fluctuations, sectoral ...

5 concludes and discusses the implications for future research. II. BUSINESS CYCLE DURATION AND DE-TRENDING In their seminal contribution to the so-called classical business cycle literature, Burns and Mitchell (1946) define business cycles as follows: Business cycles are a type of fluctuations found in the aggregate economic activity

Capitalism. Business cycles are intervals of general expansion followed by recession in economic performance. The changes in economic activity that characterize business cycles have important implications for the welfare of the general population, government institutions, and private sector firms. There are numerous specific definitions of what ...

Nonetheless, the business circumstances for companies investing in research and development spending are not the same. Due to the business cycles, its ability to engage in innovation mostly suffers. Moreover, during the recession of 2008-2010, many OECD economies witnessed decreasing research and development spending (Ahmad et al., 2021 ...

NuSTAR General Observer - Cycle 11 (D.9 NuSTAR) solicits proposals for basic research relevant to the NuSTAR mission. NuSTAR Cycle 11 will commence on or about June 1, 2025, and last for a nominal period of 12 months, subject to the mission being extended beyond September 2025 by Astrophysics Senior Review. Further details on the […]