Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Research Skills Scale for Senior High School Students: Development and Validation

2022, Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal

The goal of this paper was to develop and validate a research scale that can measure the research skills of SHS students. From review of relevant literatures, an initial draft of the scale was crafted. The initial draft of the scale, composing of five constructs and 48 indicators, was subjected to validation by a panel of research experts where two items were omitted. The scale was administered to SHS students (n=126). Exploratory factor analysis was employed to refine the research instrument and reliability testing was undertaken. As a result, 38 items were identified (α = 0.968) in three dimensions: problem conceptualization with 12 items (α = 0.905), research methods and data analysis with 18 items (α = 0.952) and writing and reporting results with eight items (α = 0.918).

Related papers

The purpose of the study was to describe the level of research capabilities of students in the senior high school department of a local university. Differences in the capabilities of students when grouped according to gender were also investigated. In addition, in-depth understanding of their perceived research capability levels was explored. A sequential explanatory mixed-method approach was employed, with 46 Grade 12 students being chosen as respondents through convenience sampling. The study started from a quantitative exploration of the students’ conceptual understanding of the four components of research (the nature of inquiry, understanding of literature and studies, research method, and interpreting results). The Research Achievement Test (RAT) developed prior to this study was used to quantitatively describe the students’ research competencies. Observations on their test performances were used to develop the interview component of the test. Results showed that overall, the s...

Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2012

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2012

AIP Conference Proceedings

Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 2019

According to (inter)national policy and curriculum documents, the acquisition of research skills is an important objective of secondary education. However, the conceptualization and hence the operationalization of this concept seems ambiguous. Furthermore, no test exists to assess students’ proficiency in (a broad range of) research skills in a 11th- and 12th-grade behavioral sciences classroom context. This article first elaborates on what constitutes research skills in this educational context. Second, the development and testing process of the Leuven Research Skills Test (LRST) is described. Third, the psychometric properties and the dimensional structure of the LRST are presented, based on a large-scale sample ( n = 405) of Belgian students in 11th and 12th grade. The results revealed that (a) the LRST is an internal consistent instrument and that (b) a hierarchical model with eight subordinate factors and one single uniting upper level factor appears to be the best fit to the d...

Journal of world Englishes and educational practices, 2022

International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education, 2020

IOSR-JRME, 2020

Background: Writing a scientific research is a very influential segment of the graduation program in King Khalid University (KKU). The purpose of the study is to investigate the research competency of the college students from KKU and to find out the factors that come in between their successful accomplishment of research tasks. Materials and Methods: The present research is an empirical study, essentially based on the qualitative approach. The study sample consisted of 70 students studying in different Colleges of King Khalid University. The data is obtained through a survey questionnaire to assess the students' attitude towards research. The results are displayed in bar graph with a mean value for each set of five items. Furthermore, the result of the observational study carried out in research classroom during three semester of the graduate program, is also presented. Results: The data shows that students' inefficiency in writing skills and their indifferent attitude towards research processes are some of the factors that are the root cause of their ineptitude to produce an authentic and coherent writing. Other factors that influence their research potentials extrinsically or intrinsically are; the limited time duration, their study habits, overburdened with other subjects, and to some extent, their inadequate knowledge about research ethics. Conclusion: The study concludes that with the provision of knowledge for research ethics with some related facilities to students for writing a good research proposal, there would be a positive impact on students' motivation level.

Privind ucenicii la Tine, Te-ai înălţat, Hristoase, la Tatăl, împreună cu Dânsul şezând. Îngerii înainte mergând, strigau: Ridicaţi porţile, ridicaţi, că Împăratul S-a suit la slava cea începătoare de lumină.

International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2010

HTR 69 - 289-300, 1976

Antiqua 56, 2022

Peloro, 2017

Yayuk Putri Rahayu, 2022

Journal of Earth Science, 2020

Physical review, 2019

Composites Part C Open Access, 2024

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2017

Instructional Science, 2007

Revista Colombiana de Cardiología, 2010

Sushruta Journal of Health Policy & Opinion

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Teaching Students How to Research

Discover how the SLICE method can help students find, critically evaluate, and cite sources.

Your content has been saved!

Teaching research skills to students is one of the most important jobs of an educator, as it allows young people to take a much more proactive role in their own learning. Good researchers know how to learn , a skill they can use in school and beyond.

It is essential that students become adept at finding and evaluating sources, vetting arguments, and learning how to navigate both print and digital media. The SLICE method of teaching research, which I devised, is a simple, memorable way for teachers and students who want to better understand the research process. SLICE stands for Sources, Library, Integrity, Citation, and Evaluation.

What’s the difference between a dictionary, encyclopedia, journal, newspaper, and magazine? Students often don’t know these differentiations, and analyzing the types of sources is an important first step for the novice researcher.

I suggest bringing in physical examples of the sources. Show students hard copies of dictionaries and encyclopedias (which they may not have ever seen). Discuss how many of these resources have migrated to the internet, such as Encyclopaedia Britannica , The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , and Oxford Research Encyclopedias .

Next, discuss with the students the different parts of any source (i.e., title, author, publication information, pagination, or abstract in the case of a journal article). This is the anatomy of sources, about which I have written before . Students should know the parts of both books and articles in order to maximize their research efficiency.

Understanding the components of sources allows them to access information quickly via the index or table of contents. While many students rely on citation-generators, it is helpful for them to understand how to write a works-cited page or bibliography without the aid of a website. Knowing the parts of their sources can help them with this.

Another key element of any discussion about sources is delving into the variety of digital sources now available. First, I like to teach them how to use Wikipedia wisely , as it is an online source that many young people turn to first. Demonstrate to students how much of the research has already been done for them on Wikipedia (i.e., through the references, sources, and external links). Then, we look at open-access databases online, such as medical websites ( PubMed , Trip medical database ), journals ( Nature Portfolio , JSTOR ), reputable polling sources ( Pew Research , Gallup , 538 , The Quinnipiac University Poll ), Google Scholar, and others. Talk to your librarian about open-access websites.

Library

Being a good researcher means knowing how to navigate a library, be it a public library, academic library, or school library. There’s simply no way around that— especially with the staggering breadth of information in our society. Libraries are more important than ever, and it is critical that students become confident and proficient library users.

First, teach students the role of libraries in organizing, disseminating, and, in many cases, preserving valuable digital and physical information. Some students may have never even visited a library!

Next, present a lesson on the different library classification systems, such as the Library of Congress system or the Dewey Decimal System. Couple this with a visit to your own school library or a field trip to a public or academic library . Take a tour of a library, getting students to explore its physical space and offerings. Additionally, invite a librarian to speak to your class, and make sure they review the digital resources and electronic databases offered through their library. A librarian would be glad to help students register for library cards, too.

I review with students the integrity of the source. Teach students, for instance, the definition of “peer review,” the peer review process, and how a peer-reviewed source often represents the gold standard of sources. A few examples of high-quality, peer-reviewed journals are Science , The New England Journal of Medicine , American Historical Review , and American Sociological Review .

Then, I usually transition to the integrity of using those sources. Here is where I introduce students to the philosophy and purpose of proper citation. We cite sources to be honest and transparent with our readers, as well as provide “bread crumbs” to readers and other scholars who wish to further examine our topic.

What’s more, I have discovered that students often don’t realize that they need to cite more than just a direct quote.

Next up, I delve into different types of citation methods, making clear that certain citation guides are used for certain fields of study: MLA ( Modern Language Association ) for the humanities, APA ( American Psychological Association ) usually for medical or scientific fields, and The Chicago Manual of Style for business, history, and the arts).

Citation, I explain, is also a road map for students to discover further research. If they read something helpful or compelling in a book or journal article, they can find its source by delving into the citations. I implore students to raid footnotes, endnotes, and bibliographies to find more sources.

Lastly, I try to have students assess sources critically. The CRAAP method— Currency, Relevancy, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose—is one of various techniques educators can use.

Ask the students, “How does the source fit into your research project?” Thinking about this early on can help students plan ahead. Annotated bibliographies can be one way that students answer this important, but often overlooked, question.

Ask Edutopia AI BETA

- Research Skills

50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills

Please note, I am no longer blogging and this post hasn’t updated since April 2020.

For a number of years, Seth Godin has been talking about the need to “ connect the dots” rather than “collect the dots” . That is, rather than memorising information, students must be able to learn how to solve new problems, see patterns, and combine multiple perspectives.

Solid research skills underpin this. Having the fluency to find and use information successfully is an essential skill for life and work.

Today’s students have more information at their fingertips than ever before and this means the role of the teacher as a guide is more important than ever.

You might be wondering how you can fit teaching research skills into a busy curriculum? There aren’t enough hours in the day! The good news is, there are so many mini-lessons you can do to build students’ skills over time.

This post outlines 50 ideas for activities that could be done in just a few minutes (or stretched out to a longer lesson if you have the time!).

Learn More About The Research Process

I have a popular post called Teach Students How To Research Online In 5 Steps. It outlines a five-step approach to break down the research process into manageable chunks.

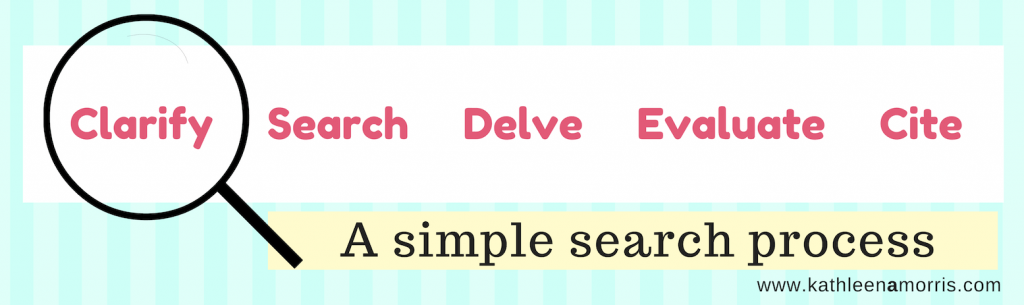

This post shares ideas for mini-lessons that could be carried out in the classroom throughout the year to help build students’ skills in the five areas of: clarify, search, delve, evaluate , and cite . It also includes ideas for learning about staying organised throughout the research process.

Notes about the 50 research activities:

- These ideas can be adapted for different age groups from middle primary/elementary to senior high school.

- Many of these ideas can be repeated throughout the year.

- Depending on the age of your students, you can decide whether the activity will be more teacher or student led. Some activities suggest coming up with a list of words, questions, or phrases. Teachers of younger students could generate these themselves.

- Depending on how much time you have, many of the activities can be either quickly modelled by the teacher, or extended to an hour-long lesson.

- Some of the activities could fit into more than one category.

- Looking for simple articles for younger students for some of the activities? Try DOGO News or Time for Kids . Newsela is also a great resource but you do need to sign up for free account.

- Why not try a few activities in a staff meeting? Everyone can always brush up on their own research skills!

- Choose a topic (e.g. koalas, basketball, Mount Everest) . Write as many questions as you can think of relating to that topic.

- Make a mindmap of a topic you’re currently learning about. This could be either on paper or using an online tool like Bubbl.us .

- Read a short book or article. Make a list of 5 words from the text that you don’t totally understand. Look up the meaning of the words in a dictionary (online or paper).

- Look at a printed or digital copy of a short article with the title removed. Come up with as many different titles as possible that would fit the article.

- Come up with a list of 5 different questions you could type into Google (e.g. Which country in Asia has the largest population?) Circle the keywords in each question.

- Write down 10 words to describe a person, place, or topic. Come up with synonyms for these words using a tool like Thesaurus.com .

- Write pairs of synonyms on post-it notes (this could be done by the teacher or students). Each student in the class has one post-it note and walks around the classroom to find the person with the synonym to their word.

- Explore how to search Google using your voice (i.e. click/tap on the microphone in the Google search box or on your phone/tablet keyboard) . List the pros and cons of using voice and text to search.

- Open two different search engines in your browser such as Google and Bing. Type in a query and compare the results. Do all search engines work exactly the same?

- Have students work in pairs to try out a different search engine (there are 11 listed here ). Report back to the class on the pros and cons.

- Think of something you’re curious about, (e.g. What endangered animals live in the Amazon Rainforest?). Open Google in two tabs. In one search, type in one or two keywords ( e.g. Amazon Rainforest) . In the other search type in multiple relevant keywords (e.g. endangered animals Amazon rainforest). Compare the results. Discuss the importance of being specific.

- Similar to above, try two different searches where one phrase is in quotation marks and the other is not. For example, Origin of “raining cats and dogs” and Origin of raining cats and dogs . Discuss the difference that using quotation marks makes (It tells Google to search for the precise keywords in order.)

- Try writing a question in Google with a few minor spelling mistakes. What happens? What happens if you add or leave out punctuation ?

- Try the AGoogleADay.com daily search challenges from Google. The questions help older students learn about choosing keywords, deconstructing questions, and altering keywords.

- Explore how Google uses autocomplete to suggest searches quickly. Try it out by typing in various queries (e.g. How to draw… or What is the tallest…). Discuss how these suggestions come about, how to use them, and whether they’re usually helpful.

- Watch this video from Code.org to learn more about how search works .

- Take a look at 20 Instant Google Searches your Students Need to Know by Eric Curts to learn about “ instant searches ”. Try one to try out. Perhaps each student could be assigned one to try and share with the class.

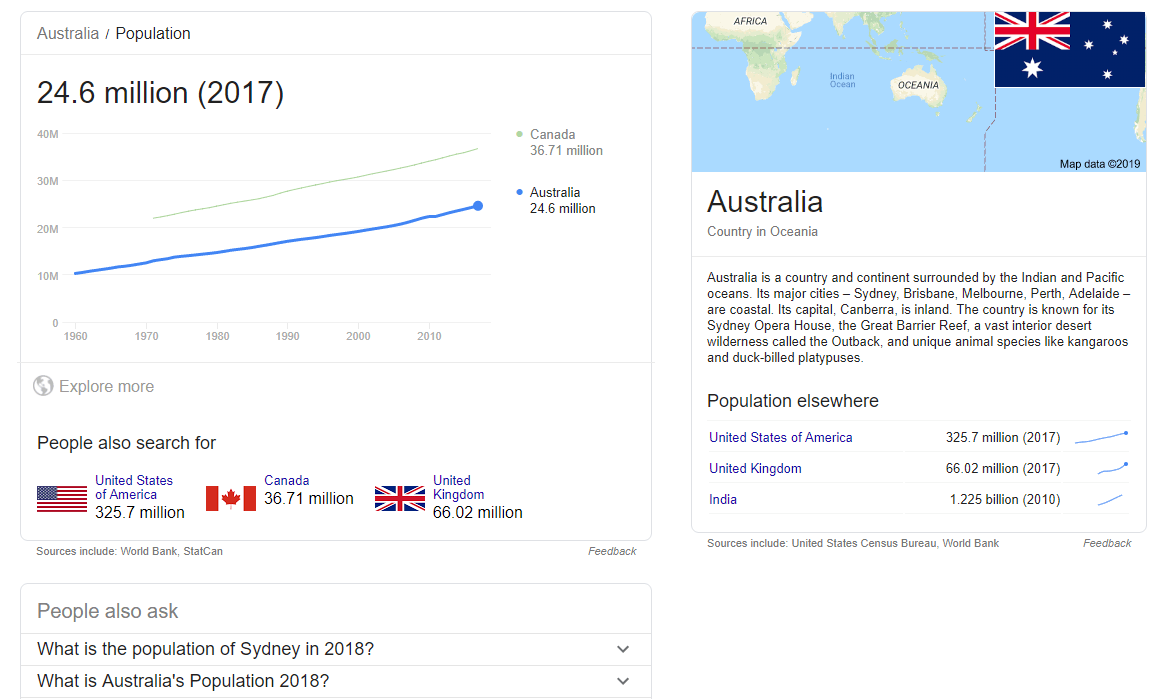

- Experiment with typing some questions into Google that have a clear answer (e.g. “What is a parallelogram?” or “What is the highest mountain in the world?” or “What is the population of Australia?”). Look at the different ways the answers are displayed instantly within the search results — dictionary definitions, image cards, graphs etc.

- Watch the video How Does Google Know Everything About Me? by Scientific American. Discuss the PageRank algorithm and how Google uses your data to customise search results.

- Brainstorm a list of popular domains (e.g. .com, .com.au, or your country’s domain) . Discuss if any domains might be more reliable than others and why (e.g. .gov or .edu) .

- Discuss (or research) ways to open Google search results in a new tab to save your original search results (i.e. right-click > open link in new tab or press control/command and click the link).

- Try out a few Google searches (perhaps start with things like “car service” “cat food” or “fresh flowers”). A re there advertisements within the results? Discuss where these appear and how to spot them.

- Look at ways to filter search results by using the tabs at the top of the page in Google (i.e. news, images, shopping, maps, videos etc.). Do the same filters appear for all Google searches? Try out a few different searches and see.

- Type a question into Google and look for the “People also ask” and “Searches related to…” sections. Discuss how these could be useful. When should you use them or ignore them so you don’t go off on an irrelevant tangent? Is the information in the drop-down section under “People also ask” always the best?

- Often, more current search results are more useful. Click on “tools” under the Google search box and then “any time” and your time frame of choice such as “Past month” or “Past year”.

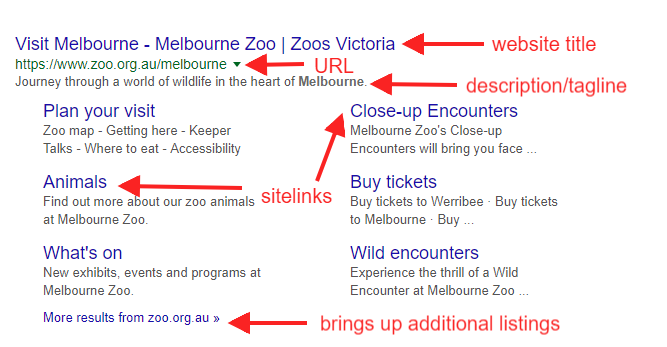

- Have students annotate their own “anatomy of a search result” example like the one I made below. Explore the different ways search results display; some have more details like sitelinks and some do not.

- Find two articles on a news topic from different publications. Or find a news article and an opinion piece on the same topic. Make a Venn diagram comparing the similarities and differences.

- Choose a graph, map, or chart from The New York Times’ What’s Going On In This Graph series . Have a whole class or small group discussion about the data.

- Look at images stripped of their captions on What’s Going On In This Picture? by The New York Times. Discuss the images in pairs or small groups. What can you tell?

- Explore a website together as a class or in pairs — perhaps a news website. Identify all the advertisements .

- Have a look at a fake website either as a whole class or in pairs/small groups. See if students can spot that these sites are not real. Discuss the fact that you can’t believe everything that’s online. Get started with these four examples of fake websites from Eric Curts.

- Give students a copy of my website evaluation flowchart to analyse and then discuss as a class. Read more about the flowchart in this post.

- As a class, look at a prompt from Mike Caulfield’s Four Moves . Either together or in small groups, have students fact check the prompts on the site. This resource explains more about the fact checking process. Note: some of these prompts are not suitable for younger students.

- Practice skim reading — give students one minute to read a short article. Ask them to discuss what stood out to them. Headings? Bold words? Quotes? Then give students ten minutes to read the same article and discuss deep reading.

All students can benefit from learning about plagiarism, copyright, how to write information in their own words, and how to acknowledge the source. However, the formality of this process will depend on your students’ age and your curriculum guidelines.

- Watch the video Citation for Beginners for an introduction to citation. Discuss the key points to remember.

- Look up the definition of plagiarism using a variety of sources (dictionary, video, Wikipedia etc.). Create a definition as a class.

- Find an interesting video on YouTube (perhaps a “life hack” video) and write a brief summary in your own words.

- Have students pair up and tell each other about their weekend. Then have the listener try to verbalise or write their friend’s recount in their own words. Discuss how accurate this was.

- Read the class a copy of a well known fairy tale. Have them write a short summary in their own words. Compare the versions that different students come up with.

- Try out MyBib — a handy free online tool without ads that helps you create citations quickly and easily.

- Give primary/elementary students a copy of Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Citation that matches their grade level (the guide covers grades 1 to 6). Choose one form of citation and create some examples as a class (e.g. a website or a book).

- Make a list of things that are okay and not okay to do when researching, e.g. copy text from a website, use any image from Google images, paraphrase in your own words and cite your source, add a short quote and cite the source.

- Have students read a short article and then come up with a summary that would be considered plagiarism and one that would not be considered plagiarism. These could be shared with the class and the students asked to decide which one shows an example of plagiarism .

- Older students could investigate the difference between paraphrasing and summarising . They could create a Venn diagram that compares the two.

- Write a list of statements on the board that might be true or false ( e.g. The 1956 Olympics were held in Melbourne, Australia. The rhinoceros is the largest land animal in the world. The current marathon world record is 2 hours, 7 minutes). Have students research these statements and decide whether they’re true or false by sharing their citations.

Staying Organised

- Make a list of different ways you can take notes while researching — Google Docs, Google Keep, pen and paper etc. Discuss the pros and cons of each method.

- Learn the keyboard shortcuts to help manage tabs (e.g. open new tab, reopen closed tab, go to next tab etc.). Perhaps students could all try out the shortcuts and share their favourite one with the class.

- Find a collection of resources on a topic and add them to a Wakelet .

- Listen to a short podcast or watch a brief video on a certain topic and sketchnote ideas. Sylvia Duckworth has some great tips about live sketchnoting

- Learn how to use split screen to have one window open with your research, and another open with your notes (e.g. a Google spreadsheet, Google Doc, Microsoft Word or OneNote etc.) .

All teachers know it’s important to teach students to research well. Investing time in this process will also pay off throughout the year and the years to come. Students will be able to focus on analysing and synthesizing information, rather than the mechanics of the research process.

By trying out as many of these mini-lessons as possible throughout the year, you’ll be really helping your students to thrive in all areas of school, work, and life.

Also remember to model your own searches explicitly during class time. Talk out loud as you look things up and ask students for input. Learning together is the way to go!

You Might Also Enjoy Reading:

How To Evaluate Websites: A Guide For Teachers And Students

Five Tips for Teaching Students How to Research and Filter Information

Typing Tips: The How and Why of Teaching Students Keyboarding Skills

8 Ways Teachers And Schools Can Communicate With Parents

10 Replies to “50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills”

Loving these ideas, thank you

This list is amazing. Thank you so much!

So glad it’s helpful, Alex! 🙂

Hi I am a student who really needed some help on how to reasearch thanks for the help.

So glad it helped! 🙂

seriously seriously grateful for your post. 🙂

So glad it’s helpful! Makes my day 🙂

How do you get the 50 mini lessons. I got the free one but am interested in the full version.

Hi Tracey, The link to the PDF with the 50 mini lessons is in the post. Here it is . Check out this post if you need more advice on teaching students how to research online. Hope that helps! Kathleen

Best wishes to you as you face your health battler. Hoping you’ve come out stronger and healthier from it. Your website is so helpful.

Comments are closed.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Al (2017) suggested the conceptualization of research skills as Problem Identification, Questioning, Hypothesis Generation, Construction and Redesign of Artifacts, Evidence Generation, Evidence Evaluation, Drawing Conclusions, and Communicating and Scrutinizing.

The goal of this paper was to develop and validate a research scale that can measure the research skills of SHS students. From review of relevant literatures, an initial draft of the scale was crafted.

Research Skills Scale for Senior High School Students Development and Validation - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. Emy Lacson, Edilberto Dejos, (2022).

Good researchers know how to learn, a skill they can use in school and beyond. It is essential that students become adept at finding and evaluating sources, vetting arguments, and learning how to navigate both print and digital media.

This post shares ideas for mini-lessons that could be carried out in the classroom throughout the year to help build students’ skills in the five areas of: clarify, search, delve, evaluate, and cite. It also includes ideas for learning about staying organised throughout the research process.

high school students receive rarely mirrors what individuals in STEM careers actually do. Students are focused more on memorization than on identifying problems and finding ways to solve those problems. STEM Student Research Handbook engages students with the same inquiry skills used by STEM professionals.

This research study aims to determine the self-assessment of the students' level of research skills to enhance teaching and learning process. This study sought to find the answer to the following research questions:

PDF | On Oct 15, 2020, John Willison and others published Handbook for research skill development and assessment in the curriculum | Find, read and cite all the research you need on...

the principles of research, motivating the student to create a research plan, searching and selecting sources, how to find them, their synthesis, their schedules, predicting results and testing hypotheses.

The primary goal of this study was to determine how contextualized instruction affects the research knowledge and skills among senior high school students.