Social Media

- Facebook Facebook Circle Icon

- Twitter Twitter Circle Icon

- Flipboard Flipboard Circle Icon

- RSS RSS Circle Icon

- Culture & Media

- Economy & Labor

- Education & Youth

- Environment & Health

- Human Rights

- Immigration

- LGBTQ Rights

- Politics & Elections

- Prisons & Policing

- Racial Justice

- Reproductive Rights

- War & Peace

- Series & Podcasts

- Hurricane Helene

- 2024 Election

Campus Organizers Are Using Research to Expose and Oppose the Global War Machine

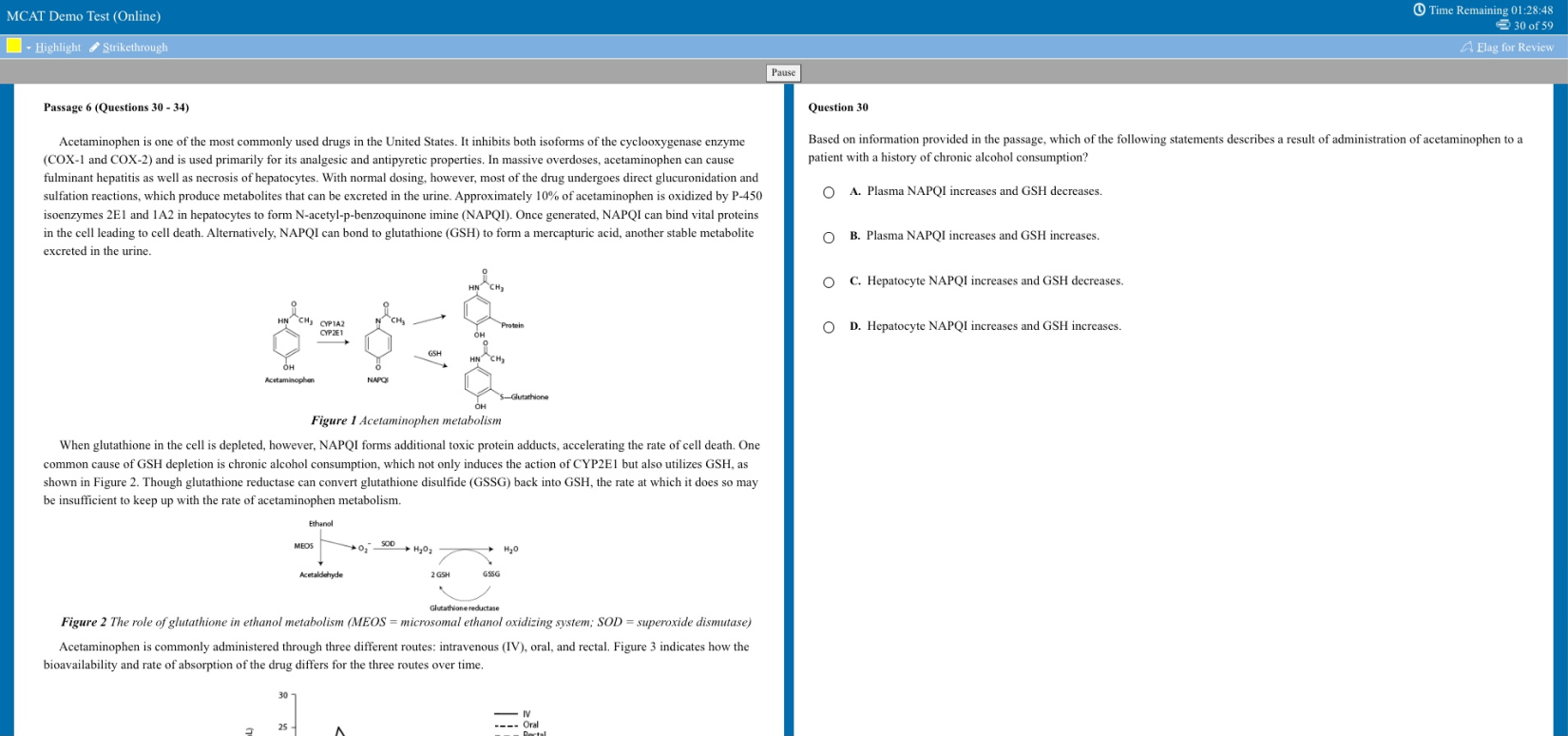

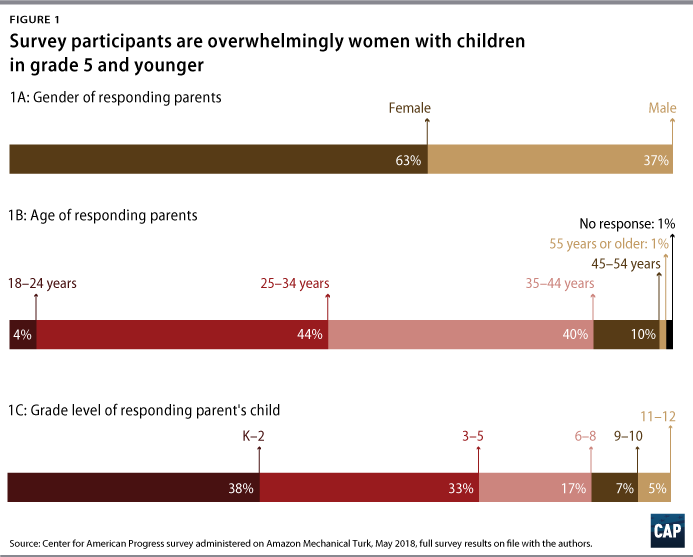

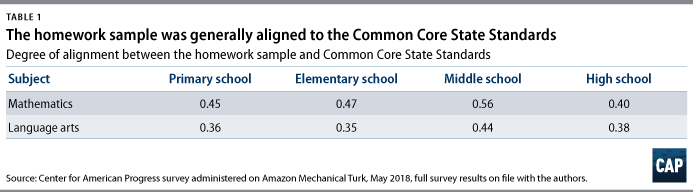

Judge rules catholic employers can deny workers time off for reproductive care, j.d. vance attends pennsylvania town hall hosted by christian nationalist pastor, biden praises carpet-bombing in beirut, tlaib condemns us-funded “bloodbath”, should us public schools eliminate homework.

Excessive homework is creating stress, not learning, for many U.S. students.

When Finnish students enroll in school at age seven, they can expect to take three or four classes a day. There are frequent breaks, plus a daily 20-minute recess. What’s more, when school is dismissed, there’s rarely any work to be completed at home. Nonetheless, Finnish students consistently rank among the world’s highest achievers in reading, math and science.

Experts attribute this to the country’s low ( 5.8 percent ) poverty rate, extensive social welfare system, 12-to-1 student-teacher ratio, and classes that fully integrate special needs students into general education classrooms. They also note that the Finnish government values teachers and encourages staff to prioritize collaboration, network building and the sharing of best practices.

Contrast this with the United States. Throughout the country, many elementary schools have completely eliminated recess. Eighteen percent of students live in poverty and approximately 1.3 million of the nation’s 50.7 million public school students are homeless.

And then there’s homework, which is increasingly assigned to students as young as five. In fact, by high school, the average time teenagers spend on homework is now 3 hours and 58 minutes a night, up from 2 hours and 38 minutes — an increase of 51 percent — over the past several decades.

The reason for this, say pro-homework teachers and administrators, is to raise the scores of U.S. students on standardized tests.

It hasn’t worked. While progressive educators agree that testing is not the only, or even the best, marker of academic achievement, it is still startling that the U.S. ranks 21st in educational outcome among the 34 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) competing countries, while Finland comes in third .

For their part, the National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association support assigning 10 minutes of homework per grade. Under this policy, first graders would be given homework taking no more than 10 minutes a day, while 12 th graders would be given up to two hours of daily work.

But many schools have sidestepped these recommendations, with kindergarteners, first and second graders often getting 25-30 minutes of work per night. Among older students, researchers have noted that excessive homework assignments have led to an increase in stress-related headaches, exhaustion, sleep difficulties and stomach ailments. They also suggest that it contributes to alcohol and drug abuse.

Abolishing Homework

It doesn’t have to be this way.

A Duke University study found that homework does little to boost elementary school achievement, a finding that has led a smattering of K-6 schools in California , Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts and Vermont to either eliminate homework completely or eliminate it during school breaks.

“Kids are terribly stressed about school, grades, peers, parental expectations and the known threats and ideation around climate change,” Nancy Romer, a longtime New York City activist and former psychology professor at Brooklyn College, told Truthout . “Many kids live in a state of impending doom.”

Add in other worries — about gun violence, racial bias, police brutality and sexual assault — and it is obvious that students of all ages have good reason to be fearful and anxious.

But can eliminating homework address even a small part of this anxiety-producing equation, increase academic achievement and lift morale?

The Upside to Homework

Jessie Winslow teaches sixth grade social studies at the Ephraim Curtis Middle School in Sudbury, Massachusetts, a wealthy community with a median household income of more than $170,000.

Winslow acknowledges that her students are coming into school with more anxiety and depression than previous academic cohorts. Nonetheless, she says she feels conflicted about the idea of skipping homework because she thinks that by middle school, students should be able to do some independent work at home. “Homework teaches time management and other coping skills,” she continues. “These kids are going to have situations that will cause them stress and they need to figure out how to handle it.”

Virginia Naughton, a grandmother in Brooklyn, New York, says she sees homework as the most direct way to know what’s going on in kids’ daily lives. “Homework is sort of a pulse, a starting point, to talk about classes, school friends and whatever else is going on,” she says.

Sid Kivanoski, a recently retired teacher at one of New York City’s highly competitive specialized high schools, is also a proponent of homework. He explains that because New York students have to pass Regents exams in English, math, science and social studies to earn a diploma, assigning homework ensures coverage of material that might appear on the exam, but that he was unable to address during class.

“I also gave homework to get them thinking about things that we’d talk about the next day, for example, why they thought the U.S. fought a war in Vietnam,” he says.

Barriers to Homework Completion

Still, Kivanoski knows that many of his students faced enormous challenges in completing their assignments. “I had one kid who would wake up at 2:00 a.m. to do homework because that was the only time it was quiet at home. Another went to the library on the way home every afternoon for the same reason. It was the sole place she could concentrate.”

Likewise, Chicago elementary school teacher Mariam Cosey sees the impact of poverty, hunger, and insecure or overcrowded housing in her classroom each and every day. “I always give my students a choice packet where they can choose which homework assignment they want to complete — word finds or word games, worksheets, or special projects — and it’s always due at the end of the week or on Monday, to give them the opportunity to get it done,” she begins. “Furthermore, I always make sure that there is something that every child has the ability to do.”

She does this despite mandates from the Chicago Board of Education dictating what should be taught and how much homework should be assigned for each grade level. In addition, Cosey offers incentives for her students to encourage assignment completion. The incentives help Cosey assess how a particular student is doing in a specific subject, and also give a window into her students’ home situations. “Kids can pick their prizes. When a child chooses gloves over candy, it tells me what’s going on in that child’s life. We love on these students, wash their faces, bring in clothes for them, and are compassionate. As teachers, we know that these kids need extra love and we give it to them.”

Homeless students face even greater hurdles when it comes to finishing their work. “There are so many barriers,” Barbara Duffield, executive director of SchoolHouse Connection , a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy organization that works to improve the educational achievement of homeless youth, told Truthout . Some are related to the living situation, with barriers like not having a quiet place to study or do homework, or no computer or internet access.

“But remember,” Duffield explains, “only 14.4 percent of students who are homeless are even staying in a shelter. Most are in hotels or motels, moving from couch to couch, or living on the streets. No matter where they’re staying, they may also be caring for their parents or younger siblings. Most are struggling to stay safe. They may be working 30 hours a week while going to school. The notion that homeless students have the time, space and consistency for good home study is seriously flawed.”

This is something that San Diego State University student Destiny Dickerson, the recipient of a SchoolHouse Connection scholarship (which grants post-secondary scholarships to students who’ve experienced homelessness), understands well. Six years ago, when Dickerson was in her first year of high school, her family was evicted from their three-bedroom home. For a short time, they lived with her grandmother, but severe overcrowding made this situation untenable and the family — four kids and two adults — ended up in a series of motels and hotels in and around Rancho Cucamonga, California.

“I would do as much homework as I could in school because there was no guarantee that we’d have WIFI at the hotel,” she explains. “In addition, all of my textbooks were stolen when someone broke into my mom’s car. My parents had told us to keep our homelessness quiet because it was embarrassing to admit that we’d lost our residence, so no one at school knew that I had no books. Some days I’d go to the library to do my homework and some hotels had a communal computer I could use, but sometimes I forgot about doing assignments because I was so focused on what was going on outside of class. I also missed assignments that were posted online since I did not have reliable access to a computer.”

Still, Dickerson maintained a B average throughout high school and reports that her teachers learned of her situation only after she won the SchoolHouse Connection scholarship. “They were shocked,” she says, “and the school cleared all the fees owed for the stolen textbooks and helped me pay for all the senior year activities.”

Dickerson considers herself lucky — she now has an affordable, stable, off-campus apartment, a laptop computer and consistent internet access — and expects to graduate with a degree in psychology in 2022.

Homework for Parents

Shomari Gallagher, a parent in Brooklyn, New York, says that while she appreciates that homework gives her a window into what her 10-year-old son is learning in school, it also often puts parents in the position of being teachers. “If the homework reinforces what they learned in school, fine,” she says. “But to have students struggle to learn something new without the benefit of a teacher’s instruction seems unfair. I sometimes look at my son’s math homework as if it’s a foreign language and have had to watch YouTube videos in order to help him. Homework is the only thing my son and I fight over. At the end of the school day he’s tired and gets frustrated.”

This set-up, Gallagher continues, also favors richer, better-educated parents who already grasp the subject matter, or have the time, research skills and English language proficiency to assist their kids. Moreover, she believes that homework serves an insidious function: “I think it trains kids to become adults who take work home from their jobs,” she says.

A Different Way

The debate over the efficacy of homework is not new. Nonetheless, the U.S. has a long way to go before consensus is reached.

Gin Langan, a mother and substitute teacher in Hayward, California, who is also an active member of the Bad Ass Teachers Association, is an outspoken critic of excessive homework. Nonetheless, she told Truthout that she is distressed by the lack of organizing on this issue.

“Many people are under the impression that homework is something that has to be done,” she begins. I talk to people about this all the time, and I always stress the social inequities in education. I speak about how inappropriate and ineffective it is for homework to be given in lower grades, and how difficult it is for kids who don’t have a quiet place to work. I discuss why we need to shift away from a white middle-class paradigm. But many parents have bought the line that homework is necessary for their kids to be competitive and get into a good college.”

Even worse, she says, in locales like Fremont, California, the district has mandated that homework be given in every grade, K-12, five nights a week.

Nevertheless, Langan believes that fact-based conversations about reducing or eliminating homework are the best way to chip away at the conventional wisdom.

Thankfully, she has the Duke University study and other research to draw on.

A white paper composed by Challenge Success, a California-based educational advocacy group, is one such resource. The paper, “ Changing the Conversation about Homework from Quantity and Achievement to Quality and Engagement ,” offers concrete recommendations for schools, school administrators and parents.

Teachers, the paper concludes, should assign work that students can do on their own, without adult intervention. Moreover, it argues, this work should be doable — not too easy, not too hard, and not too time-consuming — to give the students a sense of accomplishment. Furthermore, the paper suggests that instructors give students a clear overview of the assignment before they leave for the day, and try to focus as many assignments as possible on tasks that can’t be completed at school.

For example, the paper suggests having students conduct interviews that will later be used to compile oral histories or require them to collect soil samples or other materials for a science experiment. Lastly, they caution against busy work, recommend quarterly “no homework nights” for middle school and high school students, and support the elimination of summer and vacation assignments.

As for parents, the paper reminds them that different kids have different study and learning styles — and that they should not elevate one modality over another. To wit: kids who like to get their work done in one sitting immediately after school ends are not inherently superior to kids who prefer taking breaks, working to music, or completing tasks late at night. They also remind parents not to overschedule their children, hover over them, or do the work for them.

But the gold standard may still be the model developed by Finnish educators. There, 15-year-olds spend an average of 2.8 hours a week outside of class doing homework and typically use their free time to play team sports, read, volunteer or socialize with family and friends.

Fundraising Deadline: Missed

Unfortunately, Truthout fell short of our fundraising goal. We still need $9,000 to stay out of the red.

Still, there’s a little time left to make up this difference. Help safeguard our nonprofit journalism: Please make a tax-deductible gift today.

Homework – Top 3 Pros and Cons

Pro/Con Arguments | Discussion Questions | Take Action | Sources | More Debates

From dioramas to book reports, from algebraic word problems to research projects, whether students should be given homework, as well as the type and amount of homework, has been debated for over a century. [ 1 ]

While we are unsure who invented homework, we do know that the word “homework” dates back to ancient Rome. Pliny the Younger asked his followers to practice their speeches at home. Memorization exercises as homework continued through the Middle Ages and Enlightenment by monks and other scholars. [ 45 ]

In the 19th century, German students of the Volksschulen or “People’s Schools” were given assignments to complete outside of the school day. This concept of homework quickly spread across Europe and was brought to the United States by Horace Mann , who encountered the idea in Prussia. [ 45 ]

In the early 1900s, progressive education theorists, championed by the magazine Ladies’ Home Journal , decried homework’s negative impact on children’s physical and mental health, leading California to ban homework for students under 15 from 1901 until 1917. In the 1930s, homework was portrayed as child labor, which was newly illegal, but the prevailing argument was that kids needed time to do household chores. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 45 ] [ 46 ]

Public opinion swayed again in favor of homework in the 1950s due to concerns about keeping up with the Soviet Union’s technological advances during the Cold War . And, in 1986, the US government included homework as an educational quality boosting tool. [ 3 ] [ 45 ]

A 2014 study found kindergarteners to fifth graders averaged 2.9 hours of homework per week, sixth to eighth graders 3.2 hours per teacher, and ninth to twelfth graders 3.5 hours per teacher. A 2014-2019 study found that teens spent about an hour a day on homework. [ 4 ] [ 44 ]

Beginning in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic complicated the very idea of homework as students were schooling remotely and many were doing all school work from home. Washington Post journalist Valerie Strauss asked, “Does homework work when kids are learning all day at home?” While students were mostly back in school buildings in fall 2021, the question remains of how effective homework is as an educational tool. [ 47 ]

Is Homework Beneficial?

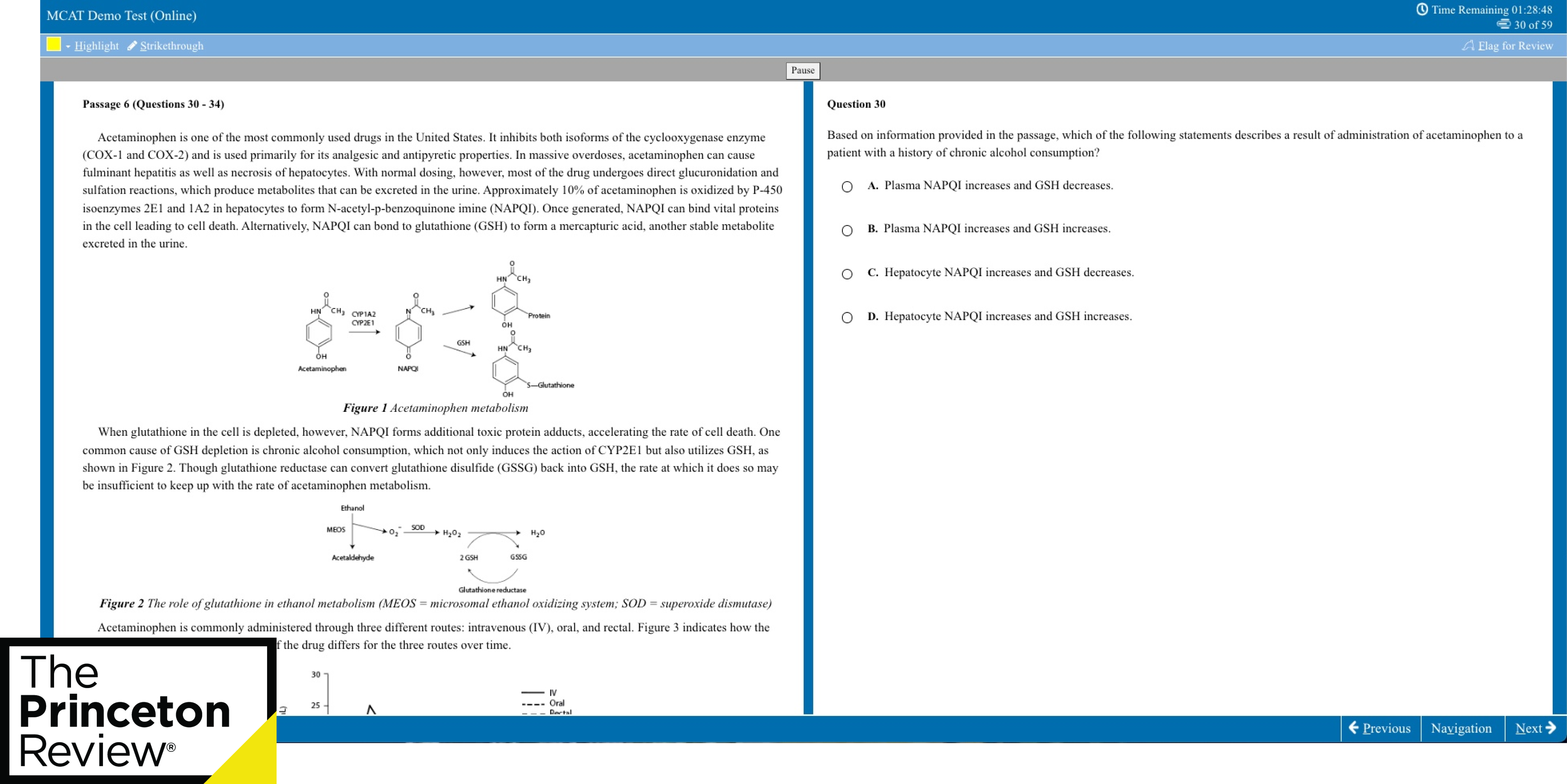

Pro 1 Homework improves student achievement. Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicated that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” [ 6 ] Students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework on both standardized tests and grades. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take-home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school. [ 10 ] Read More

Pro 2 Homework helps to reinforce classroom learning, while developing good study habits and life skills. Students typically retain only 50% of the information teachers provide in class, and they need to apply that information in order to truly learn it. Abby Freireich and Brian Platzer, co-founders of Teachers Who Tutor NYC, explained, “at-home assignments help students learn the material taught in class. Students require independent practice to internalize new concepts… [And] these assignments can provide valuable data for teachers about how well students understand the curriculum.” [ 11 ] [ 49 ] Elementary school students who were taught “strategies to organize and complete homework,” such as prioritizing homework activities, collecting study materials, note-taking, and following directions, showed increased grades and more positive comments on report cards. [ 17 ] Research by the City University of New York noted that “students who engage in self-regulatory processes while completing homework,” such as goal-setting, time management, and remaining focused, “are generally more motivated and are higher achievers than those who do not use these processes.” [ 18 ] Homework also helps students develop key skills that they’ll use throughout their lives: accountability, autonomy, discipline, time management, self-direction, critical thinking, and independent problem-solving. Freireich and Platzer noted that “homework helps students acquire the skills needed to plan, organize, and complete their work.” [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 49 ] Read More

Pro 3 Homework allows parents to be involved with children’s learning. Thanks to take-home assignments, parents are able to track what their children are learning at school as well as their academic strengths and weaknesses. [ 12 ] Data from a nationwide sample of elementary school students show that parental involvement in homework can improve class performance, especially among economically disadvantaged African-American and Hispanic students. [ 20 ] Research from Johns Hopkins University found that an interactive homework process known as TIPS (Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork) improves student achievement: “Students in the TIPS group earned significantly higher report card grades after 18 weeks (1 TIPS assignment per week) than did non-TIPS students.” [ 21 ] Homework can also help clue parents in to the existence of any learning disabilities their children may have, allowing them to get help and adjust learning strategies as needed. Duke University Professor Harris Cooper noted, “Two parents once told me they refused to believe their child had a learning disability until homework revealed it to them.” [ 12 ] Read More

Con 1 Too much homework can be harmful. A poll of California high school students found that 59% thought they had too much homework. 82% of respondents said that they were “often or always stressed by schoolwork.” High-achieving high school students said too much homework leads to sleep deprivation and other health problems such as headaches, exhaustion, weight loss, and stomach problems. [ 24 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] Alfie Kohn, an education and parenting expert, said, “Kids should have a chance to just be kids… it’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.” [ 27 ] Emmy Kang, a mental health counselor, explained, “More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies.” [ 48 ] Excessive homework can also lead to cheating: 90% of middle school students and 67% of high school students admit to copying someone else’s homework, and 43% of college students engaged in “unauthorized collaboration” on out-of-class assignments. Even parents take shortcuts on homework: 43% of those surveyed admitted to having completed a child’s assignment for them. [ 30 ] [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Read More

Con 2 Homework exacerbates the digital divide or homework gap. Kiara Taylor, financial expert, defined the digital divide as “the gap between demographics and regions that have access to modern information and communications technology and those that don’t. Though the term now encompasses the technical and financial ability to utilize available technology—along with access (or a lack of access) to the Internet—the gap it refers to is constantly shifting with the development of technology.” For students, this is often called the homework gap. [ 50 ] [ 51 ] 30% (about 15 to 16 million) public school students either did not have an adequate internet connection or an appropriate device, or both, for distance learning. Completing homework for these students is more complicated (having to find a safe place with an internet connection, or borrowing a laptop, for example) or impossible. [ 51 ] A Hispanic Heritage Foundation study found that 96.5% of students across the country needed to use the internet for homework, and nearly half reported they were sometimes unable to complete their homework due to lack of access to the internet or a computer, which often resulted in lower grades. [ 37 ] [ 38 ] One study concluded that homework increases social inequality because it “potentially serves as a mechanism to further advantage those students who already experience some privilege in the school system while further disadvantaging those who may already be in a marginalized position.” [ 39 ] Read More

Con 3 Homework does not help younger students, and may not help high school students. We’ve known for a while that homework does not help elementary students. A 2006 study found that “homework had no association with achievement gains” when measured by standardized tests results or grades. [ 7 ] Fourth grade students who did no homework got roughly the same score on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) math exam as those who did 30 minutes of homework a night. Students who did 45 minutes or more of homework a night actually did worse. [ 41 ] Temple University professor Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek said that homework is not the most effective tool for young learners to apply new information: “They’re learning way more important skills when they’re not doing their homework.” [ 42 ] In fact, homework may not be helpful at the high school level either. Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, stated, “I interviewed high school teachers who completely stopped giving homework and there was no downside, it was all upside.” He explains, “just because the same kids who get more homework do a little better on tests, doesn’t mean the homework made that happen.” [ 52 ] Read More

Discussion Questions

1. Is homework beneficial? Consider the study data, your personal experience, and other types of information. Explain your answer(s).

2. If homework were banned, what other educational strategies would help students learn classroom material? Explain your answer(s).

3. How has homework been helpful to you personally? How has homework been unhelpful to you personally? Make carefully considered lists for both sides.

Take Action

1. Examine an argument in favor of quality homework assignments from Janine Bempechat.

2. Explore Oxford Learning’s infographic on the effects of homework on students.

3. Consider Joseph Lathan’s argument that homework promotes inequality .

4. Consider how you felt about the issue before reading this article. After reading the pros and cons on this topic, has your thinking changed? If so, how? List two to three ways. If your thoughts have not changed, list two to three ways your better understanding of the “other side of the issue” now helps you better argue your position.

5. Push for the position and policies you support by writing US national senators and representatives .

| 1. | Tom Loveless, “Homework in America: Part II of the 2014 Brown Center Report of American Education,” brookings.edu, Mar. 18, 2014 | |

| 2. | Edward Bok, “A National Crime at the Feet of American Parents,” , Jan. 1900 | |

| 3. | Tim Walker, “The Great Homework Debate: What’s Getting Lost in the Hype,” neatoday.org, Sep. 23, 2015 | |

| 4. | University of Phoenix College of Education, “Homework Anxiety: Survey Reveals How Much Homework K-12 Students Are Assigned and Why Teachers Deem It Beneficial,” phoenix.edu, Feb. 24, 2014 | |

| 5. | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “PISA in Focus No. 46: Does Homework Perpetuate Inequities in Education?,” oecd.org, Dec. 2014 | |

| 6. | Adam V. Maltese, Robert H. Tai, and Xitao Fan, “When is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math,” , 2012 | |

| 7. | Harris Cooper, Jorgianne Civey Robinson, and Erika A. Patall, “Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Researcher, 1987-2003,” , 2006 | |

| 8. | Gökhan Bas, Cihad Sentürk, and Fatih Mehmet Cigerci, “Homework and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review of Research,” , 2017 | |

| 9. | Huiyong Fan, Jianzhong Xu, Zhihui Cai, Jinbo He, and Xitao Fan, “Homework and Students’ Achievement in Math and Science: A 30-Year Meta-Analysis, 1986-2015,” , 2017 | |

| 10. | Charlene Marie Kalenkoski and Sabrina Wulff Pabilonia, “Does High School Homework Increase Academic Achievement?,” iza.og, Apr. 2014 | |

| 11. | Ron Kurtus, “Purpose of Homework,” school-for-champions.com, July 8, 2012 | |

| 12. | Harris Cooper, “Yes, Teachers Should Give Homework – The Benefits Are Many,” newsobserver.com, Sep. 2, 2016 | |

| 13. | Tammi A. Minke, “Types of Homework and Their Effect on Student Achievement,” repository.stcloudstate.edu, 2017 | |

| 14. | LakkshyaEducation.com, “How Does Homework Help Students: Suggestions From Experts,” LakkshyaEducation.com (accessed Aug. 29, 2018) | |

| 15. | University of Montreal, “Do Kids Benefit from Homework?,” teaching.monster.com (accessed Aug. 30, 2018) | |

| 16. | Glenda Faye Pryor-Johnson, “Why Homework Is Actually Good for Kids,” memphisparent.com, Feb. 1, 2012 | |

| 17. | Joan M. Shepard, “Developing Responsibility for Completing and Handing in Daily Homework Assignments for Students in Grades Three, Four, and Five,” eric.ed.gov, 1999 | |

| 18. | Darshanand Ramdass and Barry J. Zimmerman, “Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework,” , 2011 | |

| 19. | US Department of Education, “Let’s Do Homework!,” ed.gov (accessed Aug. 29, 2018) | |

| 20. | Loretta Waldman, “Sociologist Upends Notions about Parental Help with Homework,” phys.org, Apr. 12, 2014 | |

| 21. | Frances L. Van Voorhis, “Reflecting on the Homework Ritual: Assignments and Designs,” , June 2010 | |

| 22. | Roel J. F. J. Aries and Sofie J. Cabus, “Parental Homework Involvement Improves Test Scores? A Review of the Literature,” , June 2015 | |

| 23. | Jamie Ballard, “40% of People Say Elementary School Students Have Too Much Homework,” yougov.com, July 31, 2018 | |

| 24. | Stanford University, “Stanford Survey of Adolescent School Experiences Report: Mira Costa High School, Winter 2017,” stanford.edu, 2017 | |

| 25. | Cathy Vatterott, “Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs,” ascd.org, 2009 | |

| 26. | End the Race, “Homework: You Can Make a Difference,” racetonowhere.com (accessed Aug. 24, 2018) | |

| 27. | Elissa Strauss, “Opinion: Your Kid Is Right, Homework Is Pointless. Here’s What You Should Do Instead.,” cnn.com, Jan. 28, 2020 | |

| 28. | Jeanne Fratello, “Survey: Homework Is Biggest Source of Stress for Mira Costa Students,” digmb.com, Dec. 15, 2017 | |

| 29. | Clifton B. Parker, “Stanford Research Shows Pitfalls of Homework,” stanford.edu, Mar. 10, 2014 | |

| 30. | AdCouncil, “Cheating Is a Personal Foul: Academic Cheating Background,” glass-castle.com (accessed Aug. 16, 2018) | |

| 31. | Jeffrey R. Young, “High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame,” chronicle.com, Mar. 28, 2010 | |

| 32. | Robin McClure, “Do You Do Your Child’s Homework?,” verywellfamily.com, Mar. 14, 2018 | |

| 33. | Robert M. Pressman, David B. Sugarman, Melissa L. Nemon, Jennifer, Desjarlais, Judith A. Owens, and Allison Schettini-Evans, “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background,” , 2015 | |

| 34. | Heather Koball and Yang Jiang, “Basic Facts about Low-Income Children,” nccp.org, Jan. 2018 | |

| 35. | Meagan McGovern, “Homework Is for Rich Kids,” huffingtonpost.com, Sep. 2, 2016 | |

| 36. | H. Richard Milner IV, “Not All Students Have Access to Homework Help,” nytimes.com, Nov. 13, 2014 | |

| 37. | Claire McLaughlin, “The Homework Gap: The ‘Cruelest Part of the Digital Divide’,” neatoday.org, Apr. 20, 2016 | |

| 38. | Doug Levin, “This Evening’s Homework Requires the Use of the Internet,” edtechstrategies.com, May 1, 2015 | |

| 39. | Amy Lutz and Lakshmi Jayaram, “Getting the Homework Done: Social Class and Parents’ Relationship to Homework,” , June 2015 | |

| 40. | Sandra L. Hofferth and John F. Sandberg, “How American Children Spend Their Time,” psc.isr.umich.edu, Apr. 17, 2000 | |

| 41. | Alfie Kohn, “Does Homework Improve Learning?,” alfiekohn.org, 2006 | |

| 42. | Patrick A. Coleman, “Elementary School Homework Probably Isn’t Good for Kids,” fatherly.com, Feb. 8, 2018 | |

| 43. | Valerie Strauss, “Why This Superintendent Is Banning Homework – and Asking Kids to Read Instead,” washingtonpost.com, July 17, 2017 | |

| 44. | Pew Research Center, “The Way U.S. Teens Spend Their Time Is Changing, but Differences between Boys and Girls Persist,” pewresearch.org, Feb. 20, 2019 | |

| 45. | ThroughEducation, “The History of Homework: Why Was It Invented and Who Was behind It?,” , Feb. 14, 2020 | |

| 46. | History, “Why Homework Was Banned,” (accessed Feb. 24, 2022) | |

| 47. | Valerie Strauss, “Does Homework Work When Kids Are Learning All Day at Home?,” , Sep. 2, 2020 | |

| 48. | Sara M Moniuszko, “Is It Time to Get Rid of Homework? Mental Health Experts Weigh In,” , Aug. 17, 2021 | |

| 49. | Abby Freireich and Brian Platzer, “The Worsening Homework Problem,” , Apr. 13, 2021 | |

| 50. | Kiara Taylor, “Digital Divide,” , Feb. 12, 2022 | |

| 51. | Marguerite Reardon, “The Digital Divide Has Left Millions of School Kids Behind,” , May 5, 2021 | |

| 52. | Rachel Paula Abrahamson, “Why More and More Teachers Are Joining the Anti-Homework Movement,” , Sep. 10, 2021 |

More School Debate Topics

Should K-12 Students Dissect Animals in Science Classrooms? – Proponents say dissecting real animals is a better learning experience. Opponents say the practice is bad for the environment.

Should Students Have to Wear School Uniforms? – Proponents say uniforms may increase student safety. Opponents say uniforms restrict expression.

Should Corporal Punishment Be Used in K-12 Schools? – Proponents say corporal punishment is an appropriate discipline. Opponents say it inflicts long-lasting physical and mental harm on students.

ProCon/Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 325 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60654 USA

Natalie Leppard Managing Editor [email protected]

© 2023 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved

- Social Media

- Death Penalty

- School Uniforms

- Video Games

- Animal Testing

- Gun Control

- Banned Books

- Teachers’ Corner

Cite This Page

ProCon.org is the institutional or organization author for all ProCon.org pages. Proper citation depends on your preferred or required style manual. Below are the proper citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order): the Modern Language Association Style Manual (MLA), the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago), the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA), and Kate Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Turabian). Here are the proper bibliographic citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order):

[Editor's Note: The APA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

[Editor’s Note: The MLA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School’s In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Your content has been saved!

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Health & Nursing

Courses and certificates.

- Bachelor's Degrees

- View all Business Bachelor's Degrees

- Business Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Healthcare Administration – B.S.

- Human Resource Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Marketing – B.S. Business Administration

- Accounting – B.S. Business Administration

- Finance – B.S.

- Supply Chain and Operations Management – B.S.

- Communications – B.S.

- User Experience Design – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree (from the School of Technology)

- Health Information Management – B.S. (from the Leavitt School of Health)

- View all Business Degrees

Master's Degrees

- View all Business Master's Degrees

- Master of Business Administration (MBA)

- MBA Information Technology Management

- MBA Healthcare Management

- Management and Leadership – M.S.

- Accounting – M.S.

- Marketing – M.S.

- Human Resource Management – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration (from the Leavitt School of Health)

- Data Analytics – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Information Technology Management – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed. (from the School of Education)

Certificates

- Supply Chain

- Accounting Fundamentals

- Digital Marketing and E-Commerce

Bachelor's Preparing For Licensure

- View all Education Bachelor's Degrees

- Elementary Education – B.A.

- Special Education and Elementary Education (Dual Licensure) – B.A.

- Special Education (Mild-to-Moderate) – B.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary)– B.S.

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– B.S.

- View all Education Degrees

Bachelor of Arts in Education Degrees

- Educational Studies – B.A.

Master of Science in Education Degrees

- View all Education Master's Degrees

- Curriculum and Instruction – M.S.

- Educational Leadership – M.S.

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed.

Master's Preparing for Licensure

- Teaching, Elementary Education – M.A.

- Teaching, English Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Science Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Special Education (K-12) – M.A.

Licensure Information

- State Teaching Licensure Information

Master's Degrees for Teachers

- Mathematics Education (K-6) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grade) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- English Language Learning (PreK-12) – M.A.

- Endorsement Preparation Program, English Language Learning (PreK-12)

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– M.A.

- View all Technology Bachelor's Degrees

- Cloud Computing – B.S.

- Computer Science – B.S.

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – B.S.

- Data Analytics – B.S.

- Information Technology – B.S.

- Network Engineering and Security – B.S.

- Software Engineering – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration (from the School of Business)

- User Experience Design – B.S. (from the School of Business)

- View all Technology Master's Degrees

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – M.S.

- Data Analytics – M.S.

- Information Technology Management – M.S.

- MBA Information Technology Management (from the School of Business)

- Full Stack Engineering

- Web Application Deployment and Support

- Front End Web Development

- Back End Web Development

3rd Party Certifications

- IT Certifications Included in WGU Degrees

- View all Technology Degrees

- View all Health & Nursing Bachelor's Degrees

- Nursing (RN-to-BSN online) – B.S.

- Nursing (Prelicensure) – B.S. (Available in select states)

- Health Information Management – B.S.

- Health and Human Services – B.S.

- Psychology – B.S.

- Health Science – B.S.

- Public Health – B.S.

- Healthcare Administration – B.S. (from the School of Business)

- View all Nursing Post-Master's Certificates

- Nursing Education—Post-Master's Certificate

- Nursing Leadership and Management—Post-Master's Certificate

- Family Nurse Practitioner—Post-Master's Certificate

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner —Post-Master's Certificate

- View all Health & Nursing Degrees

- View all Nursing & Health Master's Degrees

- Nursing – Education (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Family Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Education (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration

- Master of Public Health

- MBA Healthcare Management (from the School of Business)

- Business Leadership (with the School of Business)

- Supply Chain (with the School of Business)

- Accounting Fundamentals (with the School of Business)

- Digital Marketing and E-Commerce (with the School of Business)

- Back End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Front End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Web Application Deployment and Support (with the School of Technology)

- Full Stack Engineering (with the School of Technology)

- Single Courses

- Course Bundles

Apply for Admission

Admission requirements.

- New Students

- WGU Returning Graduates

- WGU Readmission

- Enrollment Checklist

- Accessibility

- Accommodation Request

- School of Education Admission Requirements

- School of Business Admission Requirements

- School of Technology Admission Requirements

- Leavitt School of Health Admission Requirements

Additional Requirements

- Computer Requirements

- No Standardized Testing

- Clinical and Student Teaching Information

Transferring

- FAQs about Transferring

- Transfer to WGU

- Transferrable Certifications

- Request WGU Transcripts

- International Transfer Credit

- Tuition and Fees

- Financial Aid

- Scholarships

Other Ways to Pay for School

- Tuition—School of Business

- Tuition—School of Education

- Tuition—School of Technology

- Tuition—Leavitt School of Health

- Your Financial Obligations

- Tuition Comparison

- Applying for Financial Aid

- State Grants

- Consumer Information Guide

- Responsible Borrowing Initiative

- Higher Education Relief Fund

FAFSA Support

- Net Price Calculator

- FAFSA Simplification

- See All Scholarships

- Military Scholarships

- State Scholarships

- Scholarship FAQs

Payment Options

- Payment Plans

- Corporate Reimbursement

- Current Student Hardship Assistance

- Military Tuition Assistance

WGU Experience

- How You'll Learn

- Scheduling/Assessments

- Accreditation

- Student Support/Faculty

- Military Students

- Part-Time Options

- Virtual Military Education Resource Center

- Student Outcomes

- Return on Investment

- Students and Gradutes

- Career Growth

- Student Resources

- Communities

- Testimonials

- Career Guides

- Skills Guides

- Online Degrees

- All Degrees

- Explore Your Options

Admissions & Transfers

- Admissions Overview

Tuition & Financial Aid

Student Success

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Military and Veterans

- Commencement

- Careers at WGU

- Advancement & Giving

- Partnering with WGU

Should Students Have Homework?

- Classroom Strategies

- See More Tags

By Suzanne Capek Tingley, Veteran Educator, M.A. Degree

It used to be that students were the only ones complaining about the practice of assigning homework. For years, teachers and parents thought that homework was a necessary tool when educating children. But studies about the effectiveness of homework have been conflicting and inconclusive, leading some adults to argue that homework should become a thing of the past.

What Research Says about Homework

According to Duke professor Harris Cooper, it's important that students have homework. His meta-analysis of homework studies showed a correlation between completing homework and academic success, at least in older grades. He recommends following a "10 minute rule" : students should receive 10 minutes of homework per day in first grade, and 10 additional minutes each subsequent year, so that by twelfth grade they are completing 120 minutes of homework daily.

But his analysis didn't prove that students did better because they did homework; it simply showed a correlation . This could simply mean that kids who do homework are more committed to doing well in school. Cooper also found that some research showed that homework caused physical and emotional stress, and created negative attitudes about learning. He suggested that more research needed to be done on homework's effect on kids.

Some researchers say that the question isn't whether kids should have homework. It's more about what kind of homework students have and how much. To be effective, homework has to meet students' needs. For example, some middle school teachers have found success with online math homework that's adapted to each student's level of understanding. But when middle school students were assigned more than an hour and a half of homework, their math and science test scores went down .

Researchers at Indiana University discovered that math and science homework may improve standardized test grades, but they found no difference in course grades between students who did homework and those who didn't. These researchers theorize that homework doesn't result in more content mastery, but in greater familiarity with the kinds of questions that appear on standardized tests. According to Professor Adam Maltese, one of the study's authors, "Our results hint that maybe homework is not being used as well as it could be."

So while many teachers and parents support daily homework, it's hard to find strong evidence that the long-held practice produces positive results.

Problems with Homework

In an article in Education Week Teacher , teacher Samantha Hulsman said she's frequently heard parents complain that a 30-minute homework assignment turns into a three-hour battle with their kids. Now, she's facing the same problem with her own kids, which has her rethinking her former beliefs about homework. "I think parents expect their children to have homework nightly, and teachers assign daily homework because it's what we've always done," she explained. Today, Hulsman said, it's more important to know how to collaborate and solve problems than it is to know specific facts.

Child psychologist Kenneth Barish wrote in Psychology Today that battles over homework rarely result in a child's improvement in school . Children who don't do their homework are not lazy, he said, but they may be frustrated, discouraged, or anxious. And for kids with learning disabilities, homework is like "running with a sprained ankle. It's doable, but painful."

Barish suggests that parents and kids have a "homework plan" that limits the time spent on homework. The plan should include turning off all devices—not just the student's, but those belonging to all family members.

One of the best-known critics of homework, Alfie Kohn , says that some people wrongly believe "kids are like vending machines—put in an assignment, get out learning." Kohn points to the lack of evidence that homework is an effective learning tool; in fact, he calls it "the greatest single extinguisher of children's curiosity that we have yet invented."

Homework Bans

Last year, the public schools in Marion County, Florida, decided on a no-homework policy for all of their elementary students . Instead, kids read nightly for 20 minutes. Superintendent Heidi Maier said the decision was based on Cooper's research showing that elementary students gain little from homework, but a lot from reading.

Orchard Elementary School in South Burlington, Vermont, followed the same path, substituting reading for homework. The homework policy has four parts : read nightly, go outside and play, have dinner with your family, and get a good night's sleep. Principal Mark Trifilio says that his staff and parents support the idea.

But while many elementary schools are considering no-homework policies, middle schools and high schools have been reluctant to abandon homework. Schools say parents support homework and teachers know it can be helpful when it is specific and follows certain guidelines. For example, practicing solving word problems can be helpful, but there's no reason to assign 50 problems when 10 will do. Recognizing that not all kids have the time, space, and home support to do homework is important, so it shouldn't be counted as part of a student's grade.

So Should Students Have Homework?

Should you ban homework in your classroom? If you teach lower grades, it's possible. If you teach middle or high school, probably not. But all teachers should think carefully about their homework policies. By limiting the amount of homework and improving the quality of assignments, you can improve learning outcomes for your students.

Ready to Start Your Journey?

HEALTH & NURSING

Recommended Articles

Take a look at other articles from WGU. Our articles feature information on a wide variety of subjects, written with the help of subject matter experts and researchers who are well-versed in their industries. This allows us to provide articles with interesting, relevant, and accurate information.

{{item.date}}

{{item.preTitleTag}}

{{item.title}}

The university, for students.

- Student Portal

- Alumni Services

Most Visited Links

- Business Programs

- Student Experience

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Student Communities

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Should We Get Rid of Homework?

Some educators are pushing to get rid of homework. Would that be a good thing?

By Jeremy Engle and Michael Gonchar

Do you like doing homework? Do you think it has benefited you educationally?

Has homework ever helped you practice a difficult skill — in math, for example — until you mastered it? Has it helped you learn new concepts in history or science? Has it helped to teach you life skills, such as independence and responsibility? Or, have you had a more negative experience with homework? Does it stress you out, numb your brain from busywork or actually make you fall behind in your classes?

Should we get rid of homework?

In “ The Movement to End Homework Is Wrong, ” published in July, the Times Opinion writer Jay Caspian Kang argues that homework may be imperfect, but it still serves an important purpose in school. The essay begins:

Do students really need to do their homework? As a parent and a former teacher, I have been pondering this question for quite a long time. The teacher side of me can acknowledge that there were assignments I gave out to my students that probably had little to no academic value. But I also imagine that some of my students never would have done their basic reading if they hadn’t been trained to complete expected assignments, which would have made the task of teaching an English class nearly impossible. As a parent, I would rather my daughter not get stuck doing the sort of pointless homework I would occasionally assign, but I also think there’s a lot of value in saying, “Hey, a lot of work you’re going to end up doing in your life is pointless, so why not just get used to it?” I certainly am not the only person wondering about the value of homework. Recently, the sociologist Jessica McCrory Calarco and the mathematics education scholars Ilana Horn and Grace Chen published a paper, “ You Need to Be More Responsible: The Myth of Meritocracy and Teachers’ Accounts of Homework Inequalities .” They argued that while there’s some evidence that homework might help students learn, it also exacerbates inequalities and reinforces what they call the “meritocratic” narrative that says kids who do well in school do so because of “individual competence, effort and responsibility.” The authors believe this meritocratic narrative is a myth and that homework — math homework in particular — further entrenches the myth in the minds of teachers and their students. Calarco, Horn and Chen write, “Research has highlighted inequalities in students’ homework production and linked those inequalities to differences in students’ home lives and in the support students’ families can provide.”

Mr. Kang argues:

But there’s a defense of homework that doesn’t really have much to do with class mobility, equality or any sense of reinforcing the notion of meritocracy. It’s one that became quite clear to me when I was a teacher: Kids need to learn how to practice things. Homework, in many cases, is the only ritualized thing they have to do every day. Even if we could perfectly equalize opportunity in school and empower all students not to be encumbered by the weight of their socioeconomic status or ethnicity, I’m not sure what good it would do if the kids didn’t know how to do something relentlessly, over and over again, until they perfected it. Most teachers know that type of progress is very difficult to achieve inside the classroom, regardless of a student’s background, which is why, I imagine, Calarco, Horn and Chen found that most teachers weren’t thinking in a structural inequalities frame. Holistic ideas of education, in which learning is emphasized and students can explore concepts and ideas, are largely for the types of kids who don’t need to worry about class mobility. A defense of rote practice through homework might seem revanchist at this moment, but if we truly believe that schools should teach children lessons that fall outside the meritocracy, I can’t think of one that matters more than the simple satisfaction of mastering something that you were once bad at. That takes homework and the acknowledgment that sometimes a student can get a question wrong and, with proper instruction, eventually get it right.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Is homework a necessary evil?

After decades of debate, researchers are still sorting out the truth about homework’s pros and cons. One point they can agree on: Quality assignments matter.

By Kirsten Weir

March 2016, Vol 47, No. 3

Print version: page 36

- Schools and Classrooms

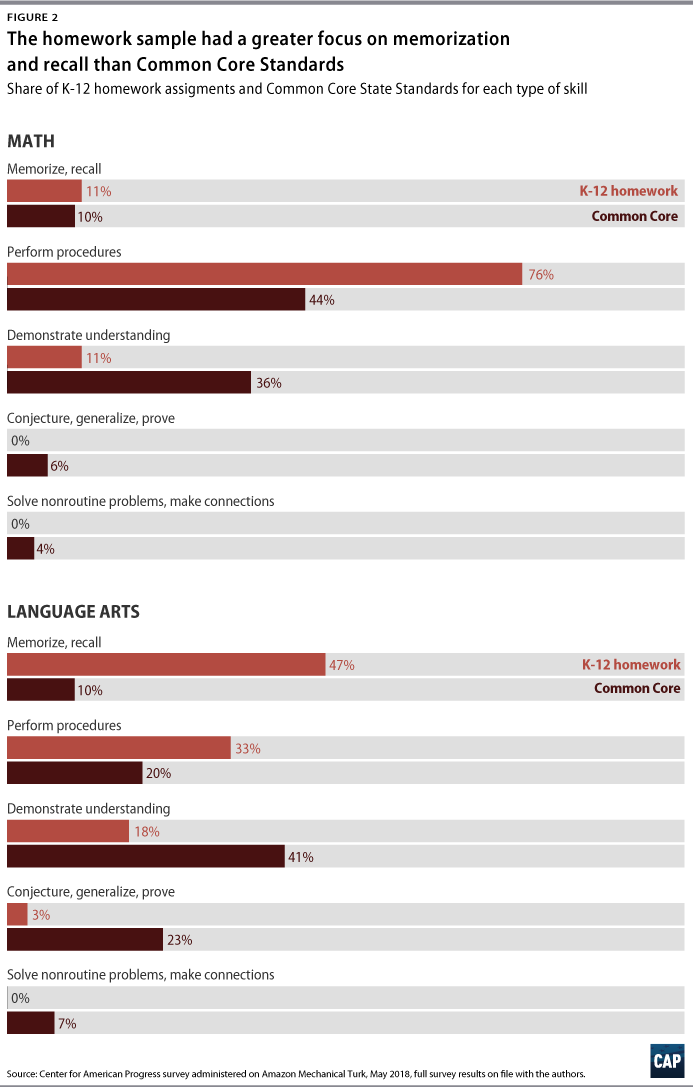

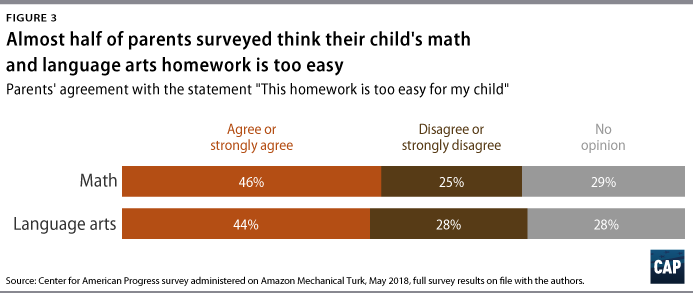

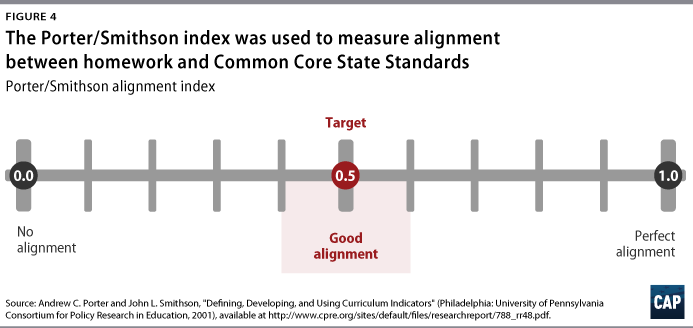

Homework battles have raged for decades. For as long as kids have been whining about doing their homework, parents and education reformers have complained that homework's benefits are dubious. Meanwhile many teachers argue that take-home lessons are key to helping students learn. Now, as schools are shifting to the new (and hotly debated) Common Core curriculum standards, educators, administrators and researchers are turning a fresh eye toward the question of homework's value.

But when it comes to deciphering the research literature on the subject, homework is anything but an open book.

The 10-minute rule

In many ways, homework seems like common sense. Spend more time practicing multiplication or studying Spanish vocabulary and you should get better at math or Spanish. But it may not be that simple.

Homework can indeed produce academic benefits, such as increased understanding and retention of the material, says Duke University social psychologist Harris Cooper, PhD, one of the nation's leading homework researchers. But not all students benefit. In a review of studies published from 1987 to 2003, Cooper and his colleagues found that homework was linked to better test scores in high school and, to a lesser degree, in middle school. Yet they found only faint evidence that homework provided academic benefit in elementary school ( Review of Educational Research , 2006).

Then again, test scores aren't everything. Homework proponents also cite the nonacademic advantages it might confer, such as the development of personal responsibility, good study habits and time-management skills. But as to hard evidence of those benefits, "the jury is still out," says Mollie Galloway, PhD, associate professor of educational leadership at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. "I think there's a focus on assigning homework because [teachers] think it has these positive outcomes for study skills and habits. But we don't know for sure that's the case."

Even when homework is helpful, there can be too much of a good thing. "There is a limit to how much kids can benefit from home study," Cooper says. He agrees with an oft-cited rule of thumb that students should do no more than 10 minutes a night per grade level — from about 10 minutes in first grade up to a maximum of about two hours in high school. Both the National Education Association and National Parent Teacher Association support that limit.

Beyond that point, kids don't absorb much useful information, Cooper says. In fact, too much homework can do more harm than good. Researchers have cited drawbacks, including boredom and burnout toward academic material, less time for family and extracurricular activities, lack of sleep and increased stress.

In a recent study of Spanish students, Rubén Fernández-Alonso, PhD, and colleagues found that students who were regularly assigned math and science homework scored higher on standardized tests. But when kids reported having more than 90 to 100 minutes of homework per day, scores declined ( Journal of Educational Psychology , 2015).

"At all grade levels, doing other things after school can have positive effects," Cooper says. "To the extent that homework denies access to other leisure and community activities, it's not serving the child's best interest."

Children of all ages need down time in order to thrive, says Denise Pope, PhD, a professor of education at Stanford University and a co-founder of Challenge Success, a program that partners with secondary schools to implement policies that improve students' academic engagement and well-being.

"Little kids and big kids need unstructured time for play each day," she says. Certainly, time for physical activity is important for kids' health and well-being. But even time spent on social media can help give busy kids' brains a break, she says.

All over the map

But are teachers sticking to the 10-minute rule? Studies attempting to quantify time spent on homework are all over the map, in part because of wide variations in methodology, Pope says.

A 2014 report by the Brookings Institution examined the question of homework, comparing data from a variety of sources. That report cited findings from a 2012 survey of first-year college students in which 38.4 percent reported spending six hours or more per week on homework during their last year of high school. That was down from 49.5 percent in 1986 ( The Brown Center Report on American Education , 2014).

The Brookings report also explored survey data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which asked 9-, 13- and 17-year-old students how much homework they'd done the previous night. They found that between 1984 and 2012, there was a slight increase in homework for 9-year-olds, but homework amounts for 13- and 17-year-olds stayed roughly the same, or even decreased slightly.

Yet other evidence suggests that some kids might be taking home much more work than they can handle. Robert Pressman, PhD, and colleagues recently investigated the 10-minute rule among more than 1,100 students, and found that elementary-school kids were receiving up to three times as much homework as recommended. As homework load increased, so did family stress, the researchers found ( American Journal of Family Therapy , 2015).

Many high school students also seem to be exceeding the recommended amounts of homework. Pope and Galloway recently surveyed more than 4,300 students from 10 high-achieving high schools. Students reported bringing home an average of just over three hours of homework nightly ( Journal of Experiential Education , 2013).

On the positive side, students who spent more time on homework in that study did report being more behaviorally engaged in school — for instance, giving more effort and paying more attention in class, Galloway says. But they were not more invested in the homework itself. They also reported greater academic stress and less time to balance family, friends and extracurricular activities. They experienced more physical health problems as well, such as headaches, stomach troubles and sleep deprivation. "Three hours per night is too much," Galloway says.

In the high-achieving schools Pope and Galloway studied, more than 90 percent of the students go on to college. There's often intense pressure to succeed academically, from both parents and peers. On top of that, kids in these communities are often overloaded with extracurricular activities, including sports and clubs. "They're very busy," Pope says. "Some kids have up to 40 hours a week — a full-time job's worth — of extracurricular activities." And homework is yet one more commitment on top of all the others.

"Homework has perennially acted as a source of stress for students, so that piece of it is not new," Galloway says. "But especially in upper-middle-class communities, where the focus is on getting ahead, I think the pressure on students has been ratcheted up."

Yet homework can be a problem at the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum as well. Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, Internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs, says Lea Theodore, PhD, a professor of school psychology at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. They are less likely to have computers or a quiet place to do homework in peace.

"Homework can highlight those inequities," she says.

Quantity vs. quality

One point researchers agree on is that for all students, homework quality matters. But too many kids are feeling a lack of engagement with their take-home assignments, many experts say. In Pope and Galloway's research, only 20 percent to 30 percent of students said they felt their homework was useful or meaningful.

"Students are assigned a lot of busywork. They're naming it as a primary stressor, but they don't feel it's supporting their learning," Galloway says.

"Homework that's busywork is not good for anyone," Cooper agrees. Still, he says, different subjects call for different kinds of assignments. "Things like vocabulary and spelling are learned through practice. Other kinds of courses require more integration of material and drawing on different skills."

But critics say those skills can be developed with many fewer hours of homework each week. Why assign 50 math problems, Pope asks, when 10 would be just as constructive? One Advanced Placement biology teacher she worked with through Challenge Success experimented with cutting his homework assignments by a third, and then by half. "Test scores didn't go down," she says. "You can have a rigorous course and not have a crazy homework load."

Still, changing the culture of homework won't be easy. Teachers-to-be get little instruction in homework during their training, Pope says. And despite some vocal parents arguing that kids bring home too much homework, many others get nervous if they think their child doesn't have enough. "Teachers feel pressured to give homework because parents expect it to come home," says Galloway. "When it doesn't, there's this idea that the school might not be doing its job."

Galloway argues teachers and school administrators need to set clear goals when it comes to homework — and parents and students should be in on the discussion, too. "It should be a broader conversation within the community, asking what's the purpose of homework? Why are we giving it? Who is it serving? Who is it not serving?"

Until schools and communities agree to take a hard look at those questions, those backpacks full of take-home assignments will probably keep stirring up more feelings than facts.

Further reading

- Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001