An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

A Case Study of Environmental Injustice: The Failure in Flint

Carla campbell.

1 Department of Public Health Sciences, Room 408, College of Health Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso, 500 W. University Ave, El Paso, TX 79968, USA

Rachael Greenberg

2 National Nurse-led Care Consortium (NNCC), Philadelphia, PA 19102, USA; su.ccnn@grebneergr

Deepa Mankikar

3 Research and Evaluation Group, Public Health Management Corporation, Philadelphia, PA 19102, USA; gro.cmhp@rakiknamd

Ronald D. Ross

4 Occupational and Environmental Medicine Consultant, Las Cruces, NM 88001, USA; [email protected]

The failure by the city of Flint, Michigan to properly treat its municipal water system after a change in the source of water, has resulted in elevated lead levels in the city’s water and an increase in city children’s blood lead levels. Lead exposure in young children can lead to decrements in intelligence, development, behavior, attention and other neurological functions. This lack of ability to provide safe drinking water represents a failure to protect the public’s health at various governmental levels. This article describes how the tragedy happened, how low-income and minority populations are at particularly high risk for lead exposure and environmental injustice, and ways that we can move forward to prevent childhood lead exposure and lead poisoning, as well as prevent future Flint-like exposure events from occurring. Control of the manufacture and use of toxic chemicals to prevent adverse exposure to these substances is also discussed. Environmental injustice occurred throughout the Flint water contamination incident and there are lessons we can all learn from this debacle to move forward in promoting environmental justice.

1. Description of the Flint Water Crisis

At this point, most Americans have heard of the avoidable and abject failure of government on the local, state and federal level; environmental authorities; and water company officials to prevent the mass poisoning of hundreds of children and adults in Flint, Michigan from April 2014 to December 2015 [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. One tends to imagine chemical poisoning as a victim dropping dead in a murder mystery, or the immediate casualties in an industrial accident or a chemical warfare attack. Unlike the release of methyl isocyanate gas in Bhopal, India in 1984 or the release of radiation with the radiation accident in Chernobyl, Ukraine in 1986, the poisoning of the population in Flint was an insidious one. People drinking the contaminated water would never have known they had elevated blood lead levels (BLLs) without specific medical testing for blood lead levels. In fact, if the water contamination had not been made public, most exposed children and their families would have never suspected they were being exposed over a 20-month period of time, and it would be expected that the water contamination and lead exposure would have continued up until today.

Lead can cause immediate acute poisoning but the subacute, moderate, long-term exposure impact of concern in Flint is more common, and much more insidious. Any resulting behavioral disturbance or loss of intellectual function would probably not been have linked by their physicians or families to lead poisoning, and instead accepted as something that had just occurred. Additionally, the adverse effects from this event may take years to surface as most negative health effects from low-level lead exposure develop slowly [ 4 ]. Hypertension and kidney damage may not present until long after the exposure. Any resulting behavioral disturbance or loss of intellectual function would probably have not been linked by their physicians or families to lead poisoning, and instead accepted as something that had just occurred.

The Flint disaster was due to the switch in water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River, which was then not treated with an anti-corrosion chemical to prevent lead particles and solubilized lead from being released from the interior of water pipes, particularly those from lead service lines or those with lead solder. This water was known to be very corrosive, so corrosive that, in fact, it was not used by the nearby auto industry [ 2 ]. The General Motors plant switched to water from the neighboring Flint Township when General Motors noticed rust spots on newly machined parts [ 2 ]. This corrosive new water supply was then not treated with the anti-corrosion treatment, in noncompliance with the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Lead and Copper Rule, which calls for action when a water supply is found to be corrosive to prevent the potential release of metals from water service lines [ 5 ].

A national water expert, Dr. Marc Edwards, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech University, has stated that the published instructions by EPA for collection of water samples for lead analysis were biased in the direction of underestimating the lead content of the water samples. He had spent years communicating this problem to EPA without a subsequent change in these instructions [ 6 ]. Dr. Edwards testified before Congress in spring 2016 that the Regional EPA Administrator was not alert to what was happening in Flint. Dr. Edwards also published papers previously bringing to the public attention the lead contamination of drinking water in Washington, DC. After Washington, DC made a change in its water disinfectant from chlorine to chloramine, residents were exposed to water with high levels of lead (140 ppb and above) from 2001 to 2004 [ 7 , 8 ]. This resulted in an increase of blood lead levels in young children (many from high-risk neighborhoods) of four times the amount that it was prior to the change in water disinfectant [ 7 , 8 ]. Dr. Edwards was a key player in ensuring that this issue was brought to light and those responsible parties were held accountable [ 9 ]. For comparison, the EPA standard for maximum contaminant level for lead in water is 15 ppb [ 5 ].

Regarding the Flint, Michigan water contamination incident, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a local pediatrician, performed a study looking at blood lead levels (BLLs) from Flint children from 2013 (before the water change) to 2015 (after the water change), assessing the percentage of BLLs over the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reference level of 5 µg/dL, reviewing water levels in Flint, and identifying geographical locations of blood and water levels using geospatial analysis. Her study demonstrated that the level of elevated blood lead levels (above 5 µg/dL) in a group of Flint children almost doubled between levels collected prior to the change in water source and afterwards; among children living in the area with highest water lead levels the percentage with elevated BLLs was approximately three times higher when compared to pre-diversion levels (4% versus 10.6%) [ 10 ]. These are extraordinary changes! (The specific blood lead levels or even range of BLLs was not reported in the article.) Unfortunately, many children in Flint already had multiple risk factors for lead poisoning, including “poor nutrition, concentrated poverty, and older housing stock” [ 10 ].

2. Elevated Blood Lead Levels in US Children and the Adverse Health Impacts and Costs of Exposure

Lead exposure in young children can lead to decrements in intelligence, development, behavior, attention, and other neurological functions. Two giants in childhood lead poisoning research and advocacy, Dr. Philip Landrigan and Dr. David Bellinger, summarize the adverse effects of lead very completely, yet succinctly: “Lead is a devastating poison. It damages children’s brains, erodes intelligence, diminishes creativity and the ability to weigh consequences and make good decisions, impairs language skills, shortens attention span, and predisposes to hyperactive and aggressive behavior. Lead exposure in early childhood is linked to later increased risk for dyslexia and school failure.” [ 11 ] Other articles and reports have also confirmed these adverse effects [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ].

Therefore, it is important to determine the extent of the problem of elevated blood lead levels in U.S. children. Currently, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2003 to 2012, 3.24% of children overall aged 1–5 years had a BLL > 5 µg/dL, compared with 7.8% of non-Hispanic Black (NHB) children [ 21 ]. Males had higher adjusted BLLs than females, and a higher poverty income ratio was associated with lower adjusted blood lead levels. Adjusted BLLs increased in renter-occupied (as opposed to owner-occupied) homes and with an increase in the numbers of smokers inside the home [ 21 ]. A previous analysis by Dixon et al. [ 22 ] of NHANES data from 1999 to 2004 found that BLLs were affected by the levels of lead in the floor and the condition of and surface type of the floor; that non-Hispanic Black children had higher BLLs than non-Hispanic white (NHW) children; that Mexican-born children had higher BLLs than those born in the U.S.; that houses built before 1940 were associated with children with higher BLLs; that children living in houses with a smoker had higher BLLs than those living with non-smokers; and that the odds of NHB children having BLLs > 5 µg/dL and > 10 µg/dL were more than double that of NHW children [ 21 , 22 ]. A recent report suggested that many children requiring blood lead testing due to Medicaid insurance status or state or city requirements for testing are not getting tested, and/or the results are not being properly followed up on [ 23 ].

The costs from lead poisoning are considerable, as are the cost savings for prevention of childhood lead poisoning. Attina and Trasande state that in the United States and Europe the lead-attributable economic costs have been estimated at $50.9 and $55 billion dollars, respectively [ 24 ]. Interestingly, they estimate a total cost of $977 billion of international dollars in low- and middle-income countries, with economic losses equal to $134.7 billion in Africa, $142.3 billion in Latin American and the Caribbean, and $699.9 billion in Asia, giving a total economic loss for these countries in the range of $728.6–$1,162.5 billion [ 24 ]. A previous analysis showed that each dollar invested in lead paint hazard control results in a return of $17–$221 or a net savings of $181–$269 billion for a specific cohort of children under six years of age as the benefits of BLL reduction would include categories such as health care, lifetime earnings, tax revenue, special education, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, and the direct costs of crime [ 25 ]. Another prior analysis estimated the economic benefits resulting from an historic lowering of children’s BLLs as measured by data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to be $110–$319 billion for each year’s cohort of 3.8 million two-year-old children, using a discounted lifetime earnings of $723,300 for each two-year-old child in 2000 dollars [ 26 ]. These estimated benefits were due to projected improvements in worker productivity due to increased intelligence quotient (I.Q.) points.

3. How the Flint Case and Other Examples Exhibit Environmental Injustice

Most affected by this egregious environmental disaster was a mostly poor and African-American population [ 27 ]. Some have speculated whether such an error in judgment might have occurred if a different population had been involved, and The New York Times uses the term racism in its editorial [ 27 ]. Another New York Times article talks of an analysis of emails from Governor Rick Snyder’s office that did not mention race but talked of costs involving Flint’s water supply, questioned scientific data regarding water contamination with lead, and mentioned uncertainties about the duties of state and local health officials [ 28 ]. It also mentions that some civil rights advocates were indicating that the Flint water crisis appeared to represent environmental racism [ 28 ]. The article goes on to discuss that the switch in water source was explicitly decided in favor of saving money for the financially unstable city of Flint, and that an emergency manager appointed by Gov. Snyder to carry out the running of the city was himself African-American [ 28 ]. One of Gov. Snyder’s key staff people sounded an alarm about the concern for lead in water, but the state health department responded back that the Flint water was safe [ 28 ].

The Flint Water Advisory Task Force, comprised of five experts in public health and water policy and convened by Governor Snyder, repeatedly stated in its findings that the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) improperly and inaccurately described the Flint water as being safe, which unfortunately was then interpreted as accurate by other state agencies and city and county agencies [ 29 ]. The Task Force report also described the Flint water crisis as “a story of government failure, intransigence, unpreparedness, delay, inaction and environmental injustice”, and adds that the MDEQ failed in its responsibility to properly enforce drinking water regulations, while the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHD) failed its mission to protect public health [ 29 ]. A recent article suggests these two agencies produced sampling data that were flawed, failed to provide accurate information to the Governor’s office, the EPA and the public, and did not respond appropriately when given information by environmental health and medical professionals [ 30 ]. The Task Force report also explains that state-appointed emergency managers replaced local decision-makers in Flint, thus removing “the checks and balances and public accountability that come with public decision-making” [ 29 ]. The group also credits the public and engaged Flint citizens with continuing to question government leadership (although the Task Force noted “callous and dismissive responses to citizens’ expressed concerns”), and the media for its investigative journalism of the crisis [ 29 ]. The Task Force’s conclusion was that “Flint water customers were needlessly and tragically exposed to toxic levels of lead and other hazards through mismanagement of their drinking water supply” [ 29 ]. The Flint Water Advisory Task Force suggests that the Michigan governor should issue an executive order to mandate training and guidance on environmental justice across all state agencies, with acknowledgement that the Flint crisis of water contamination is an example of environmental injustice which has fallen on a predominantly African-American community [ 29 ]. The Task Force issued 44 recommendations to remedy the results of the failure of proper governance and resultant lead poisoning [ 29 , 30 ].

Many have spoken out about this environmental injustice, including research scientists and clinicians [ 11 , 31 , 32 , 33 ] and public health professionals [ 34 ]. Even the EPA administrator, Gina McCarthy, is speaking about how Michigan evaded the EPA regarding the Flint water crisis and how this type of disaster cannot happen elsewhere [ 34 , 35 ]. Dr. Robert Bullard, dean of the School of Public Health at Texas Southern University, calls the Flint water crisis—leading to lead exposure and poisoning with long delays in addressing the problem—a classic case of environmental racism [ 36 ]. “Environmental racism is real…so real that even having the facts, having the documentation and having the information has never been enough to provide equal protection for people of color and poor people” [ 37 ]. He continues, “It takes longer for the response and it takes longer for the recovery in communities of color and low-income communities.” [ 37 ] He explains that regional EPA officials and state officials in Michigan responded first with a cover-up, “and then defensively—either trying to avoid responsibility or minimizing the extent of the damage”, as contrasted with handling of other environmental problems in predominantly white communities [ 37 ]. An example is then given of government officials on all levels helping to clean up a spill of coal ash in Roane County, Tennessee, in a mostly white community [ 37 ]. A Democrat who represents Flint, Michigan, Representative Dan Kildee, called race “the single greatest determinant of what happened in Flint” [ 28 ]. What is the solution? Dr. Bullard suggests that real solutions will result when communities previously left out of decision-making are offered a seat at the table [ 31 ]. In order to stop unequal protection from environmental hazards, Dr. Bullard has come up with five principles he suggests government adopt to further environmental justice: “guaranteeing the right to environmental protection, preventing harm before it occurs, shifting the burden of proof to the polluters, obviating proof of intent to discriminate, and redressing existing inequities” [ 37 ]. Charles Lee, another author writing about environmental justice who worked in the Office of Environmental Justice at EPA, quotes a definition of the environment as “the place where we live, where we work, and where we play” [ 38 ]. He goes on to state that “environmental justice must be the starting point for achieving healthy people, homes, and communities” [ 38 ]. Lastly, the Flint Water Task Force elaborates on its finding of environmental injustice in the Flint case. “Environmental justice or injustice, therefore, is not about intent. Rather, it is about process and results—fair treatment, equal protection, and meaningful participation in neutral forums that honor human dignity…The facts of the Flint water crisis lead us to the inescapable conclusion that this is a case of environmental injustice. Flint residents, who are majority Black or African American and among the most impoverished of any metropolitan area in the United States, did not enjoy the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards as that provided to other communities” [ 29 ].

The reader is referred to several references [ 1 , 2 , 3 ] for a more detailed timeline of the specific events and actions that occurred in Flint. The Flint Water Task Force report also provides a summary of its findings and recommendations, giving greater details on the specific events and actions during the switch in water supply [ 29 ]. Regardless of the motivations behind the water supply mismanagement, we must improve governmental safeguards and public health surveillance to strive to avoid such needless exposures to environmental toxicants in the future.

Another recent disaster, involving contamination of local water supplies, was that of the contamination of the Animas River in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico by mine waste from the Gold King Mine, leading to excessively high levels of some toxic elements metals including lead, arsenic and cadmium (all of these being toxic metals) [ 39 , 40 , 41 ]. The river water was subsequently off limits for agricultural use and closed for recreational use [ 39 , 42 ]. The Navajo Nation has recently expressed how difficult and problematic this poisoning of their drinking water source has been to this tribe, and that they have not been adequately reimbursed for the adverse impacts to their water source and way of life [ 43 , 44 ]. The Native American Rights Fund states that a source of clean and abundant water is hard to come by for many Native tribes and peoples and that many face health and developmental risks from environmental problems such as surface and groundwater contamination, hazardous waste disposal, illegal dumping, and mining wastes, all of which can contribute to poor quality of water [ 45 ]. As the Flint, the Navajo Nation, and the Native American Rights group exposures highlight, poor and minority communities are unfortunately too often exposed to poisonous chemicals in their neighborhoods and on their tribal lands, leading to environmental injustice [ 44 ].

Not only has the incident in Flint brought to light the contamination of Flint’s water system, it raises issues about local water supplies to towns and cities, and particularly to child care centers and school systems, around the nation [ 46 , 47 , 48 ]. This has caused our nation to focus on investigating for lead contamination in water supplies in other cities, particularly in school systems, child care centers and other places occupied by children [ 49 , 50 ]. A Huffington Post article states that the Flint water crisis has provided a wake-up call to the country with the “discovery” of poisoned water in many communities in the U.S., and that our water infrastructure is outdated and deteriorating, and that water sampling procedures for lead are also “dangerously” outdated, as they allow for 10% of the population to be exposed to levels over the EPA maximum contaminant level [ 51 ]. Some cities have been cited for their exemplary actions in keeping their city water supplies free from lead contamination [ 52 ].

Historically, the scientists in the companies that put lead in gasoline and lead in paint became aware of the dangers of those specific lead exposures, but it took much time to finally remove lead from these products; many counties banned the use of lead-based paint in residential housing before the U.S. did [ 53 , 54 ]. One author states, “Flint’s tragedy is shedding light on a health issue that’s been lurking in U.S. households for what seems like forever. But that demands the question: Why has lead poisoning never really been treated like what it is—the longest-lasting childhood-health epidemic in U.S. history?” [ 55 ]. Bliss then goes on to describe how when in the 1950s, when “millions of children had had been chronically or acutely exposed (to lead)” and this had been linked to health problems, that “If the lead industry had stepped up then (or if it had been forced to by government)”, maybe lead poisoning would have been treated like any other major childhood disease—polio, for example. In the 1950s, “Fewer than sixty thousand new cases of polio per year created a near-panic among American parents and a national mobilization that led to vaccination campaigns that virtually wiped out the disease within a decade”, write Rosner and Markowitz [ 56 ]. “With lead poisoning, the industry and federal government could have mobilized together to systemically detoxify the nation’s lead-infested housing stock, and end the epidemic right there” [ 55 ]. Bliss then goes on to describe how “the industry’s powerful leaders diverted the attention of health officials away from their products, and toward class and race” by associating childhood lead poisoning with that of a child “with ‘ignorant’ parents living in ‘slums’” [ 55 ]. Bliss goes on to state that “lead poisoning in children can be eradicated…Today the cost of detoxifying the entire nation hovers around $1 trillion, says Rosner. Any federal effort to systematically identify and remove lead from infested households would be complex, decades-long, and require ongoing policy reform. ‘But it’s also saving a next generation of children,’ Rosner says. ‘You’re actually going to stop these kids from being poisoned. And isn’t that worth something?’” [ 56 ]. “And Rosner is a tiny bit hopeful. Amid national conversation about economic inequality, a housing crisis, and the value of black and Latino lives, the attention that Flint has brought to lead might usher in the country’s first comprehensive lead-poisoning prevention program” [ 56 ].

With the information about lead contamination in Flint and many cities around the country, one might wonder whether there is a dearth of information or recommendations about how to prevent and manage childhood lead poisoning. There is not. Many authors have weighed in on this question recently [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 15 , 17 , 19 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 ], some with very specific plans and ideas. Primary prevention of lead exposure has been particularly emphasized in almost all of them. Landrigan and Bellinger compel us to “map the sources of lead, get the lead out, and make sure there is no new lead” [ 11 ]. Jacobs and colleagues at the National Center for Healthy Housing have started a campaign for lead exposure detection and lead poisoning prevention based on these three principles: “find it, fix it, and fund it” [ 33 ]. Some call for revised standards for lead in air, house dust, soil and water [ 12 , 61 , 62 , 63 ]. The chief causes of lead exposure are nicely summarized by Levin and colleagues [ 64 ]. Unfortunately, childhood lead poisoning prevention is often deemed to be not important enough to work on, with other pressing medical and public health problems intervening; it is also complicated, complex and involves many stakeholders. Thus, the clinicians, government officials, and public health officials looking for a quick fix and a one-prescription answer to this medical problem are often disappointed and discouraged.

Concern about the neurotoxic effects of lead has been expanded now to include the neurotoxic effects of many more new chemicals out in use by the American public, including children. Children are exposed to chemicals in their everyday lives, as these are found in toys, children’s products, personal care items such as shampoos and skin creams, on foods in the form of pesticide residues, and in the air in the form of air pollutants. Some authors have weighed in on the need for more control of the manufacture and use of these toxicants and for more research into adverse health effects [ 31 , 65 , 66 ]. In 2015, a unique group of research scientists, clinicians, government representatives, and health care advocates met to form the Project TENDR (Targeting Environmental Neurodevelopmental Risks) which focuses on engendering action to prevent exposure of fetuses, infants and children to environmental toxicants [ 67 ]. The group has created a list of five chemical classes of neurotoxins which have adverse effects on brain development. The list includes lead, specific air pollutants, organophosphate pesticides, phthalates, and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), which are flame retardants. These were selected based on the degree of evidence for their adverse effects and the ability of this group and other scientists, clinicians, government officials, and advocates to work effectively to prevent exposures to these toxicants. Project TENDR has recently released a consensus statement with many signatures of both individuals and groups [ 67 , 68 , 69 ], as well as other articles on the project’s work [ 70 ]. Later this year, the group will release specific recommendations for prevention of exposure to the five chemical groups. The recent passage of the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act has been a welcome revision and updating of the Toxic Substances Control Act promulgated by EPA in 1976 [ 71 , 72 , 73 ]. This is a step in right direction for better control of exposures to lead and other toxic chemicals in our environment.

4. Future Directions: How to Move Toward Environmental Justice

How do we remedy the situation in Flint, Michigan, and prevent future episodes similar to the Flint and Navajo Nation disasters? The Flint Water Task Force recommends that the MDHHS establish a Flint Toxic Exposure Registry to follow-up on the children and adults who were residing in Flint from April 2014 until the present, and carry out more aggressive clinical and public health follow-up for all children with elevated BLLs in the state [ 29 ]. It also recommends that routine lead screening and appropriate follow-up occur in the children’s medical homes (with the primary care provider) [ 29 ]. Additionally, the Task Force recommends that the Genesee County Health Department improve follow-up of health concerns in cooperation with the MDHHS and City of Flint “to effect timely, comprehensive, and coordinated activity and ensure the best health outcomes for children and adults affected” [ 29 ]. Dr. Hanna-Attisha has established the Flint Child Health and Development Fund which will support children and their families to obtain the optimum health and development outcomes, early childhood education, access to a pediatric medical home, improved nutrition and integrated social services [ 6 ]. The Michigan State University (MSU)/Hurley Pediatric Public Health Initiative will assess, monitor, and intervene to increase children’s readiness to succeed in school by providing the above services, along with stimulating environments and parenting education [ 6 ]. This type of close follow-up has been recommended under the Flint Recovery and Remediation section of the Flint Water Task Force, as well as a recommendation to establish a dedicated subsidiary fund in the Michigan Health Endowment Fund for funding health-related services for Flint residents [ 29 ]. Therefore, local efforts will be taken to counteract the negative consequences of exposure to lead for Flint’s children. Several recent publications support the positive effects that enriched home environments can have on cognition and behavior in both human and animal studies [ 74 , 75 , 76 ].

Secondly, government agencies at the federal, state and local level and municipal authorities will need to improve their performance to ensure environmental justice, rather than contribute toward environmental injustice. This was mandated in an Executive Order by President William Clinton which requires all federal agencies to take action to ensure environmental justice [ 77 ]. The American Academy of Pediatrics provides a good starting point regarding childhood lead exposure prevention with their recommendation that “The US EPA and HUD should review their protocols for identifying and mitigating residential lead hazards (e.g., lead-based paint, dust, and soil) and lead-contaminated water from lead service lines or lead solder and revise downward the allowable levels of lead in house dust, soil, paint, and water to conform with the recognition that there are no safe levels of lead” [ 12 ]. They also give many other recommendations for government, as well as for pediatricians and other health care providers, for reducing and preventing children’s exposure to lead. Other groups, authors and reports have weighed in on what needs to be fixed and carried out, as indicated earlier in this article. As Bellinger puts it, “We know where the lead is, how people are exposed, and how it damages health. What we lack is the political will to do what should be done” [ 32 ].

Looking at the Flint case specifically, why was the water supply switched in Flint? The evidence seems to point to financial reasons for this. In Flint, state officials decided to save money without concern for providing environmental protections for a community at well-established increased risk. This is clear injustice in environmental protection to a low income and minority community. Why weren’t the corrosion control measures implemented? The Flint Water Task Force implicates various leadership groups, including the MDEQ, MDHHS, Michigan’s Governor’s Office, State-appointed Emergency Managers, the EPA, and City of Flint, although the MDEQ and EPA seem to share most culpability [ 29 ].

5. Conclusions

In short, this crisis was the result of failures on every level. We have presented various comments about how environmental racism and injustice played into this situation. Why were the concerns and complaints about water quality from a mostly African-American community not addressed? The facts presented demonstrate that environmental injustice is the major and underlying factor involved in the events in Flint. Having a state-appointed emergency manager in charge took away the normal communication the City of Flint might have had with its residents and constituents. The Flint Water Task Force has a list of 44 recommendations, mostly directed at the various agencies and offices involved, for improving the situation and preventing further problems [ 29 ]. Much of this involves recommending that these entities seek and follow expert advice, whether on water treatment techniques or protecting the public’s health [ 29 ]. It is also imperative to rebuild relationships with Flint’s community and respond to community needs in order to make real and lasting change. Perhaps putting the Flint situation under a microscopic analysis may prevent future episodes of such environmental injustice.

We must do a better job at moving forward and preventing environmental injustice; our future work is cut out for us.

Author Contributions

The concept of the paper was developed by all of the authors. Carla Campbell performed the lead writing. Rachael Greenberg, Deepa Mankikar and Ronald Ross contributed references, edited the paper, and contributed to the revisions. All authors reviewed the article and approved the final content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Instructional Materials

- Free Resources

- For Preservice Teachers

- NCCSTS Case Collection

- Science and STEM Education Jobs

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Browse All Titles

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Submit Book Proposal

- Web Seminars

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Leaders Institute • New Orleans 24

- National Conference • Philadelphia 25

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Submit a Proposal

- Conference Reviewers

- Past Conferences

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

Case Studies in Environmental Justice

A Joint Science– Humanities Project

Science Scope—September/October 2020 (Volume 44, Issue 1)

By Elizabeth Schibuk and Melissa Psallidas

Share Start a Discussion

CONTENT AREA Environmental Science and Humanities

GRADE LEVEL 7

BIG IDEA/UNIT Environmental justice

ESSENTIAL PRE-EXISTING KNOWLEDGE Some knowledge of ecology and water pollution is helpful but not required.

TIME REQUIRED 2 weeks

COST $0–$100 depending on inclusion of artistic project and existing available supplies

SAFETY No safety issues

We work in a school where conversations around race, income, and equity are integral to everyday learning. These topics serve as the foundation of our curriculum and drive the “why” of each unit of study. We felt it was both natural and necessary to end the year with an interdisciplinary unit that addressed environmental injustice and its disproportionate effect on individuals and communities of color.

Research has shown that using real-world contexts to teach science content can improve both motivation and achievement in science ( Kuhn and Muller 2014 ). For two weeks, we integrated our seventh-grade science and humanities classes, creating an extended “project block” where we co-taught a large combined class of two seventh-grade sections. Students went to their project-block class for 2.5 hours a day for a series of learning tasks that we co-designed and co-taught. In these two weeks, students in seventh grade learned about large themes in the study of environmental justice and became deep experts in one of four case studies in environmental racism. Students discovered and unpacked the layered implications of environmental racism, the notion that exposures to environmental risks are not equally distributed by race and class ( Mohai, Pellow, and Roberts 2009 ). Their culminating task was to create both a feature article that highlighted their case study as an example of environmental racism and an original watercolor protest piece. Together, these two work products would demonstrate their understanding of environmental justice as it applies to their case study and empower them to create artwork to express their reactions and share their voice on this issue. Figure 1 maps out the timeline for the project, each step of which is explained in greater detail in the article.

Unit timeline for the project

| Day 1

| |

| Days 2-4

| |

| Day 5-6

| |

| Day 7-10

| |

| Day 11

|

Although many schools might not have the scheduling flexibility to organize the instructional day for science and humanities team-teaching, our hope is that science and humanities teachers interested in interdisciplinary learning could lift pieces of this project in ways that work well in their teaching context when and where possible (see Wonder Week Student Overview in Online Supplemental Materials ).

Unit launch

The project began with a set of experiences designed to build students’ awareness of the relationship between environmental health and factors such as race and income in the United States.

Gallery walk

Students built background knowledge about the upcoming content by analyzing various images, artwork, maps, and graphs that pertained to environmental racism. Examples include photographs from abandoned industrial waste sites, infographics about the history of environmental justice, photographs from environmental protests, and a variety of artwork. The images were sorted into six stations, through which students rotated and gathered observations and curiosities in their note-catchers (see Gallery Walk Note-Catcher in Online Supplemental Materials ). At the end of the gallery walk, students were prompted to define environmental racism using nothing but their inferencing skills and what they had gathered from the sources. At this point in the process, students were able to gather that there were clearly differences in the overall environmental health of communities of color and predominantly white communities, but they hadn’t yet dug into how or why.

Building background knowledge

Graphing task.

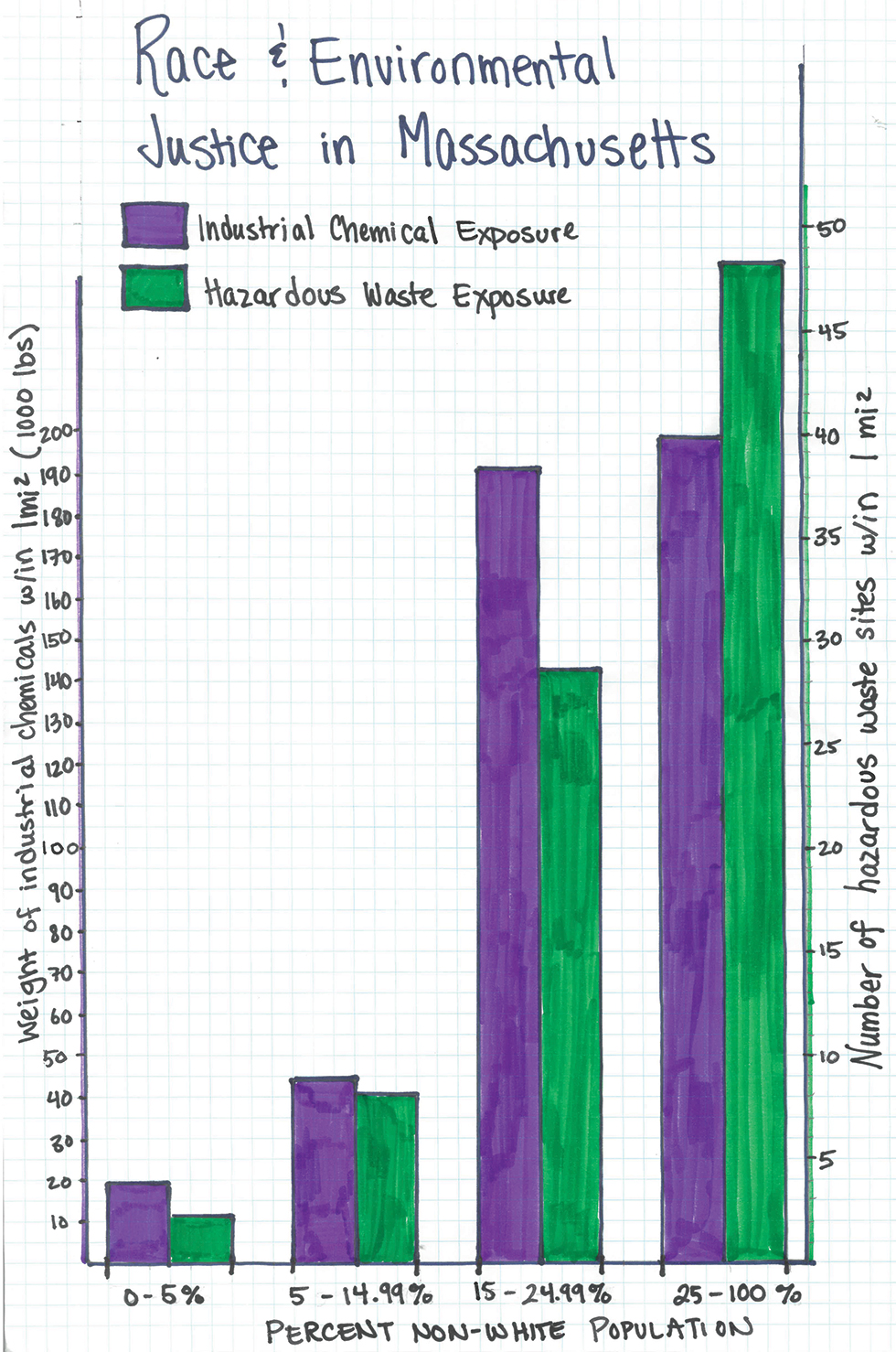

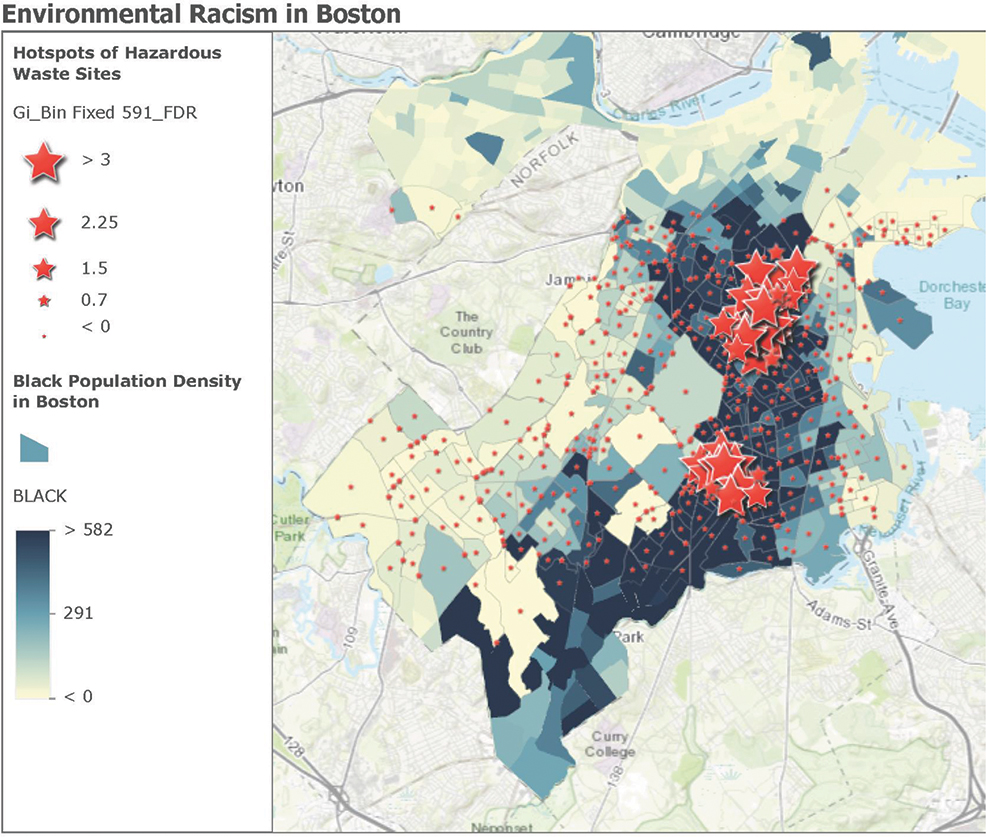

Following the gallery walk, students dug deeper into the issue of environmental racism through a data analysis task (see Environmental Racism: Exploring the Data in Online Supplemental Materials ). Students were given tabulated data about industrial chemical and hazardous waste exposure and release sites in Massachusetts, as a function of income bracket and of race. Students began by studying the data and deciding what type of graph to make, then were coached in creating two double bar graphs (one for income and one for race). Because the two data sets (industrial chemical and hazardous waste exposure) have different units and different orders of magnitude, students needed to create two y -axes. Students were coached in creating one y -axis on the left for weight of industrial chemical exposure and a second one on the right for the number of hazardous waste release sites (see sample graph in Figure 2 ). Students were also asked to look for patterns in a map (see Figure 3 ) that similarly addressed the relationship between hazardous waste exposure and race, and in so doing working toward grades 6–8 application of the crosscutting concept of patterns in science.

Sample student graph of authentic data about industrial hazardous waste expoata about industrial hazardous waste exposure as a function of percentage of nonwhite population and later as a function of average neighborhood income

Map of Boston displaying Black population density and hazardous waste hotspots (map courtesy of Erin Duffer)

The initial idea for this graphing task came from the graphs available in the Teaching Tolerance activity “Biases in Exposure to Pollution in Massachusetts,” but the activity was rewritten and expanded so that students were creating their own graphs. The graphing task played an instrumental role in supporting students in building out their working definition of environmental racism on the basis of pattern seeking in data analysis and not strictly in reading or note-taking.

Common text

We read a common text about the Gulf Coast oil spill in 2010 to continue to build a stronger foundational knowledge base about environmental racism before splitting into differentiated case study groups. Students read excerpts from the article “The Gulf Oil Spill: An Environmental Justice Disaster” by Julie Weiss from Teaching Tolerance and from the article “Why Oil Spills are a Racial Issue” by Cord Jefferson, published in The Root (see Resources for links to both articles). This study solidified the notion that a natural disaster itself may not be an act of racism, but the circumstances in the aftermath, or the negligence and indifference beforehand, can be. Students concluded that the impact of the spill was felt most keenly by low-income families and people of color, not because of the coincidental and accidental location of the spill, but because of the intentional disposal of oil-related debris. After the reading assignment, students revisited their original definition of environmental racism, making edits and additions on the basis of what they had learned in the article.

We hosted an environmental justice panel driven by questions that students had generated from the gallery walk and graphing task. We invited a local college professor who specializes in environmental justice, a local reporter who has written about relevant topics, and a faculty member who was living in Puerto Rico during hurricane Maria. Students had time to ask questions of the visitors to deepen the knowledge they had already begun building in reading the common texts.

Common film

In our last background-building learning task, we watched “Rise” (Season 1, Episode 1: Sacred Water: Standing Rock Part 1), a film about the Dakota Access Pipeline and conflict around water pollution and indigenous land rights (see “Rise” film assignment in Online Supplemental Materials ). We used this film screening as an opportunity to discuss the concept of a “case study” as an approach to learning about an issue.

Case study research and mentor text analysis

In preparing for the project, we curated resources for four different case studies in environmental justice:

- Hurricane Katrina and the federal government’s relief efforts after the storm

- Asthma and its disproportionate effect on people of color

- Maquiladoras (foreign-owned factories located in Mexico)

- Tar Creek, the Native American land that became a U.S. Superfund site in 1983

To transition from building background knowledge to case study research, we previewed the four case study options for students through a gallery walk where they could peruse some of the research artifacts such as video clips, article excerpts, graphics, and images that would become source material for each case study.

Students were given the opportunity to express their case study preferences and then were assigned a case study based on their stated preference as well as their current reading level as some case studies had more accessible source material prepared. We then gave each student a research folder with preselected print research materials and guided note-taking sheets for their case study. We were able to guarantee each student either their first or second choice, and students readily jumped in with their assigned group.

Differentiation in reading instruction

Students were grouped on the basis of their STAR Reading scores and Fountas and Pinnell data. Lexile (L) levels of assigned informational texts were informed by STAR Reading reports. The Maquiladoras and Tar Creek groups had heterogeneous mixes of all students reading at or above grade level, and all reading materials ranged from 1095L–1465L (grades 10–11). Students in the Hurricane Katrina group were reading slightly below grade level, around 1030L (grade 7). Students in the Asthma group needed additional reading and writing supports, and read texts around 950L (grade 6). All reading instruction was guided by seventh-grade informational text reading standards.

Students in the Maquiladoras and Tar Creek groups were assigned a reading partner within their group. In each pairing, there was at least one student who read above grade level and one student who read at a seventh-grade level. During daily reading time, these students read a vocabulary preview to introduce words in the text that would be difficult to define solely using context clues and background knowledge. Each day students had different instructions for their “during reading” task, but they could mostly guide their own learning as a case study team from the materials and written instructions provided (see Asthma Texts with Stop and Jots, Hurricane Katrina Articles with Stop and Jots, Maquiladoras Texts with Stop and Jots, and Tar Creek Texts with Stop and Jots, all in Online Supplemental Materials ).

Students in the Hurricane Katrina group needed more support to access their assigned research materials. Each day the Katrina group began with teacher guidance in previewing important vocabulary from that day’s text. This group also received reading instruction, but students were guided through the process (using modelling and think alouds) for the first few paragraphs of their assigned text before being left to do it as a group without a teacher. They then continued the process on their own after the teacher left the group.

Students in the Asthma group received guided instruction from a teacher or support staff at most times during the research process. Although most of their research materials were also rigorous texts with seventh-grade vocabulary and text structure, they also had supplemental visual and multimedia resources that allowed them to gain background knowledge before approaching the daily text. By previewing the text content with accessible resources, students were able to more effectively make meaning of grade-level texts.

At the end of every class, students shared their groups’ new findings as they pertained to the topic of environmental justice. After these closing share-outs, students would revisit their working definition of environmental racism and again make necessary edits or additions based on their new knowledge.

Science research: Building content expertise

The final stage of the students’ research process was to work through a self-directed series of science content learning tasks (available in the linked resources) that asked students to use text and audiovisual resources to build scientific background knowledge related to their case studies (see Science Background Research: Asthma Case Study, Katrina Case Study, Maquiladoras Case Study, and Tar Creek Case Study, all in Online Supplemental Materials ). The assignments are similar for the four case studies, but the materials and some of the questions are tailored specifically to the relevant science content of each case study.

Collapsed church sits in the deserted Lower Ninth Ward neighborhood of New Orleans seven months post-Katrina

In their case-study science work, students were asked questions designed to guide them to the understanding that the environmental degradation described in each of these case studies is the result of urbanization and development happening without an ethic of environmental stewardship.

These science tasks also supported students in building supplemental knowledge in human physiology such that they could understand the impact of relevant pollutants on the human body. Students were given an opportunity to choose a relevant body system that they were most interested in learning about and using the Scholastic Study Jams video series to build their knowledge of how this organ system is meant to function. The Study Jam films are freely available online and present content in an accessible student-friendly manner, filled with visuals and contextual anecdotes. By using film, students can watch, take notes, and digest the content at their own pace. Students made connections back to their case study reading to build their understanding of how exposure to toxins in the affected populations impacted the physical health and wellness of those exposed.

Situating the science content research at the end of the case study research gave a compelling reason for students to deeply engage with the readings and films, as they had already developed an interest in understanding the injustices done onto those affected in their case study through their research. Students were being asked to learn about environmental degradation and human physiology to help them better understand the implications of the relevant toxins on the populations they were studying, and in turn to strengthen the feature articles they would then be writing. Students were asked to consider how human activities were at the root of each environmental justice issue and thus consider growing human impact on the environment.

Creating final products

Writing workshop: teaching feature article writing.

With their background case-study reading and science learning complete, students were ready to begin their feature articles. Students became journalists, drafting feature stories that shared their insights on their particular case study. The articles drew connections between the environmental hazards detailed in the case study and the role of race and class. Feature article instruction was approached in two different buckets: first structure, then style. Students analyzed the structure of a number of feature articles, observing everything from the font size of subheadings to the reasoning for shorter, chunked paragraphs that enhance readability and flow. All instruction about structure and organization of feature articles was delivered through analysis of mentor texts (exemplar feature articles to develop understanding of format and content; see Feature Article Mentor Text Notes in Online Supplemental Materials ). Students incorporated case study research into their feature articles as they aimed to elevate the voices of those affected by the environmental injustice at hand, while sharing and citing reliable research studies and data.

Before thinking about style and craft, students dedicated two days of writing workshop time to organization and structure. They analyzed purpose and structure of feature articles, then brainstormed the purpose of their own article (see Feature Article Brainstorm and Outline in Online Supplemental Materials ). Once they determined their own purpose for writing, they began organizing their ideas into separate sections with headings. By sifting through their research folders—rich with annotated articles, notes from multimedia sources, and exit tickets—students were able to synthesize key ideas from their research and organize them into different sections of their feature article. They also ordered these sections in such a way that would intentionally reveal important information to the reader and enhance the purpose of their article. To transition from the brainstorming process, which mainly focused on synthesis and organization, to the drafting process, where they would be focusing on craft and style, students drafted the topic sentence for each section. Once each student’s topic sentences were approved, they began drafting their articles.

Differentiation in writing instruction

The Maquiladoras, Tar Creek, and Hurricane Katrina groups all received writing instruction together, while the Asthma group received separate, more scaffolded instruction. The Asthma group needed support synthesizing the information from multiple resources into a few paragraphs organized by topic and delivered in a purposeful order. They used a graphic organizer that held space for exactly three sections (whereas the other three groups had free range about the amount of sections they felt necessary, and some students drafted up to six separate headings). They were instructed to create a first section that would give important introductory knowledge to the reader, essentially defining asthma and listing its causes. Through guided small-group instruction, they sifted through their learning materials to find at least one quote that would fit into this section. Then they jotted down bullet points of other information they would include that belonged under this first heading. They were then instructed to draft a section explaining who is mostly affected by asthma. Last, they came up with the topic of the third section on their own. Essentially, there was a gradual release process as they worked to draft the first section, then the second, then the third, which was done independently.

At the end of the drafting process, students from all groups participated in a peer-revision activity. Students received a partner in their own group for the first round and a partner in a different group for the second round. They provided feedback by marking up a printed copy of their partner’s feature article with colors that indicated area of growth in a particular part of the rubric (see Feature Article Rubric: Maquiladoras, Hurricane Katrina, Tar Creek in Online Supplemental Materials ). This color-coded revision process allowed for students to give their peers guided, rubric-based feedback, without simply making the revision for them.

Protest paintings: Incorporating artistry

As a school with an arts-focused mission, we seek opportunities to harness our students’ passion for art as a lever for engagement and for building a sense of personal connection to the curricular content. In creating a rigorous visual art component for this assignment, students are asked to consider how they can leverage visual imagery to engage and invest their audience in the content, which in turn reinforces their own sense of investment and attachment to the content. In addition, in writing their artist statements, students are provided with another learning opportunity to synthesize their learning and its broader meaning.

We began the visual arts component of the project around the time students were beginning to write their feature articles. This allowed us to break up the 2.5-hour project block into smaller components, split between art studio and writer’s workshop. We opened our studio time with a gallery walk studying examples of environmental protest art (see Environmental Protest Art, Gallery Walk Note-Catcher in Online Supplemental Materials ).

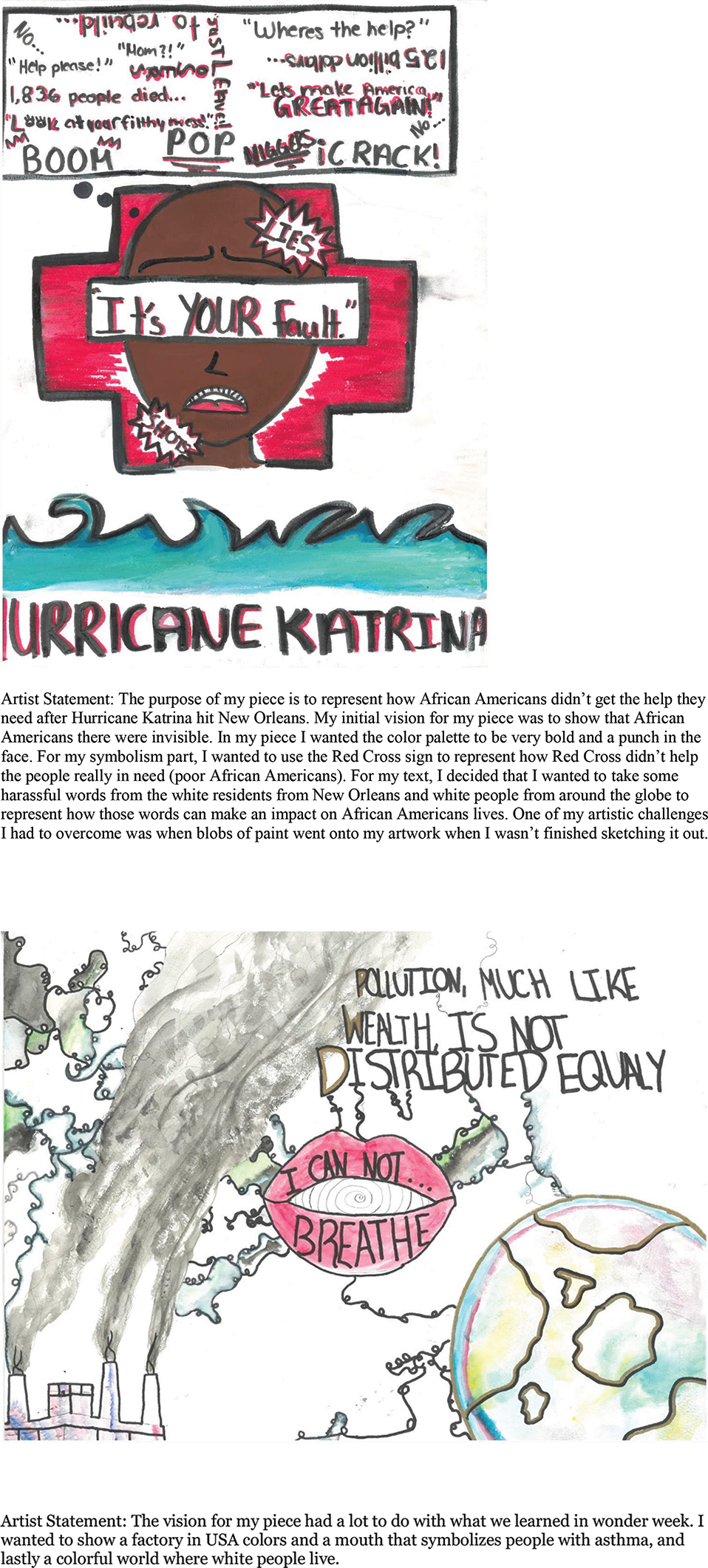

After the gallery walk, students completed an art planning document that was designed to help them think about how to create their own environmental protest art that explicitly references and responds to what they had learned about their case study (see Art Project Planning in Online Supplemental Materials ). The art planning document asked students to gather the three most compelling stories, facts, and questions they encountered in their research, and from there to brainstorm three symbols and three phrases they could use to communicate this learning in their work. Students were challenged to intentionally and purposefully use symbolism to teach and make a statement about environmental racism in the context of their case study, a process they then wrote about in their final artist statements (see student artwork in Figure 4 and Artist Statement Directions in Supplemental Online Materials).

Sample student artwork and artist statements: TOP: one student in the Hurricane Katrina case study group; BOTTOM: one student in the Asthma case study group

Celebration of learning

Our school follows the EL (formerly Expeditionary Learning) model. One of the core foundational tenets of EL is that expeditions culminating in public displays of student work “compel students to reflect on and articulate what they have learned, how they learned, questions they answered, research they conducted, and areas of strength and struggles” ( EL Education n.d. ). Celebrations of learning are a core ritual at our school, and nearly every major project or learning expedition culminates with a public display of student work. The formats vary depending on grade level, content, and type of work. Consistent, however, is the notion that students know from the beginning that their work will be made public for their peers, faculty, administrators, parents, and friends of the school. The celebration of learning is not just a display of work, but a learning experience for students where they practice reciting, synthesizing, and reflecting on their learning.

Students at our school take leadership roles in planning and curating celebrations of learning, building authentic ownership over their work and a true sense of pride. Students were invited to participate in a voluntary planning committee for the celebration of learning. We do not screen for student skill level or work quality in the celebration of learning committee—it is entirely voluntary and open to all students who are interested. We frame participation as optional, not for extra credit or any other transactional reward, and a leadership opportunity. All students plan and prepare for the event, and are active participants on the day of the event, but inviting interested students into the fold in planning the logistics of the event further builds investment and excitement across the class community.

The celebration of learning for this project took the format of a gallery exhibit. Students set up a gallery of their artwork, organized into clusters by case study, with their printed artist statements and printed feature articles on display (see One-Page Story Sample and Student Artwork with Artists’ Statements in Online Supplemental Materials ). Students stood by their work during a 45-minute block while guests from across the school community came to observe students’ artwork, read their feature articles, and ask students questions about their learning.

Science assessment

Students’ work in this project was assessed not according to performance expectations but rather to the Next Generation Science Standards science and engineering practices: analyzing and interpreting data, and obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information ( NGSS Lead States 2013 ). As this project was a multidisciplinary experience meant to sit separately from the main curriculum, we welcomed the invitation to focus assessment on the applications of science and engineering practices to more deeply understanding a socio-scientific issue.

Students were explicitly assessed in analyzing and interpreting data in the introductory graphing activity where they created two double-bar graphs using data sets about local environmental health exposure concerns. When writing about their graphs, and the relationship between income, race, and exposure to industrial chemicals and hazardous waste, students needed to demonstrate their ability to see and discuss patterns in data (see Environmental Racism Data Task Rubric in Online Supplemental Materials ).

Students were also assessed in obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information through their final written feature article (see Science Background Research Rubric in Online Supplemental Materials ). In this work they were engaging with the (grades 3–5) application of this practice, as they were expected to read and understand grade-appropriate scientific texts. In a future iteration of this project, we would push to the (grade 6–8) application of this practice by providing students with complex data sets relevant to their case studies and guiding them through the analysis of this data and its connection to their case study.

Reflections, tips, and future considerations

As we think forward on how to improve students’ learning in this project, we believe that a more explicit introduction to the purpose of journalism and feature articles, specifically science journalism, could have enriched students’ writing. Additionally, we noticed that students needed support in learning how to fluently integrate science content into their feature writing. Some students were able to authentically weave in their knowledge of human physiology and the impact that modern life is having on the natural world, while others left out their science content knowledge entirely. In the future, we would take additional time to have students explicitly study how science journalists weave science content explanations into their work in the context of a broader piece whose main focus is a human interest story, but one grounded in science.

Elizabeth Schibuk ( [email protected] ) is a middle school science teacher and Melissa Psallidas is a middle school humanities teacher, both at the Conservatory Lab Charter School in Dorchester, Massachusetts.

Jefferson, C. 2010, September 2. Why oil spills are a racial issue. The Root. https://www.theroot.com/why-oil-spills-are-a-racial-issue-1790883618

Weiss, J. 2010. The Gulf oil spill: An environmental justice disaster . https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/the-gulf-oil-spill-an-environmental-justice-disaster

Online Supplemental Materials

Art Project Planning— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Artist Statement Directions— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Asthma Texts with Stop and Jots— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Environmental Protest Art, Gallery Walk Note-Catcher— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Environmental Racism Data Task Rubric— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Environmental Racism: Exploring the Data— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Feature Article Brainstorm and Outline— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Feature Article Mentor Text Notes— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Feature Article Rubric: Maquiladoras, Hurricane Katrina, Tar Creek— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Gallery Walk Note-Catcher— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Hurricane Katrina Articles with Stop and Jots— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Maquiladoras Texts with Stop and Jots— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

One-Pager Story Sample— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

“Rise” Film Assignment— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Science Background Research: Asthma Case Study— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Science Background Research: Katrina Case Study— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Science Background Research: Maquiladoras Case Study— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Science Background Research: Tar Creek Case Study— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Science Background Research Rubric— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Student Artwork with Artists’ Statements— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Tar Creek Texts with Stop and Jots— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

Wonder Week Student Overview— https://www.nsta.org/online-connections-science-scope

EL Education. n.d. Celebrations of learning: Why this practice matters .

Kuhn J., and Muller A.. 2014. Context-based science education by newspaper story problems: A study on motivation and learning effects . Perspectives in Science 2 (1-4): 5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pisc.2014.06.001

Mohai P., Pellow D., and Roberts J.T.. 2009. Environmental justice . Annual Review of Environment and Resources 34 (1): 405–430. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348.

NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For states, by states . Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Jefferson C. 2010, September 2. Why oil spills are a racial issue . The Root.

Weiss J. 2010. The Gulf oil spill: An environmental justice disaster .

Feature Article Brainstorm and Outline—

Feature Article Mentor Text Notes—

Feature Article Rubric: Maquiladoras, Hurricane Katrina, Tar Creek—

Gallery Walk Note-Catcher—

Hurricane Katrina Articles with Stop and Jots—

Maquiladoras Texts with Stop and Jots—

One-Pager Story Sample—

“Rise” Film Assignment—

Science Background Research: Asthma Case Study—

Science Background Research: Katrina Case Study—

Science Background Research: Maquiladoras Case Study—

Science Background Research: Tar Creek Case Study—

Science Background Research Rubric—

Student Artwork with Artists’ Statements—

Tar Creek Texts with Stop and Jots—

Wonder Week Student Overview—

Equity Inclusion

You may also like

Reports Article

: Domestic Case Studies : International Case Studies :

| Domestic Case Studies |

| Ashley Atkinson |

| Allison Parker |

| Jamie Kendziuk |

| Kate McCormick |

| Deborah Kolben |

| Jeanette Wardynski |

| Scott Sherman |

| Curt Davidson |

| Josh Poshman |

| Steve Dancy |

| Jeffery Rebitzke |

| Melissa McMillan |

| Becca Meuninck |

| Harry Statter |

| Michelle Lin |

| Sarah Brooks |

| Elyse Bolterstein |

| Liam Kelly |

| Allie Choi |

| Jim Mezza |

| Peter Macjewski |

| Melissa Resslar |

| Michael Perrin |

| J Holtzman |

| Alicia Lyttle |

| Kathryn Whiteman |

| Leslie Lott |

| Kimberly Clark |

| Ryan Polkowski |

| Amal Berry |

| Jackie Callahong, et al |

| |

| Alice Cheshire |

| Erin King, Scott TenBrink, Jon Gunther, Deepti Reddy, Amy MacDonnald, Shanna Wheeler |

| Erin King, Scott TenBrink, Jon Gunther, Deepti Reddy, Amy MacDonnald, Shanna Wheeler |

| Capree Houston |

| Max Bayrum |

| Matthew Weinbaum |

| International Case Studies |

| Cheryl Gregory |

| Brian Maguranyanga |

| Jeremy Lopatin |

| Ben Peacock |

| Kristi Jacques |

| Kathleen Grimes |

| Julie Narimatsu |

| Nisha Kapadia |

| Hui Ling Lee |

| Stephanie J. Sprague |

| Paul R. Siersma |

| Pattrick Callahan |

| Hsun-Yi-Hsieh |

| Lena Van Haren |

| Erin King, Scott TenBrink, Jon Gunther, Deepti Reddy, Amy MacDonnald, Shanna Wheeler |

The Aspen Institute

©2024 The Aspen Institute. All Rights Reserved

- 0 Comments Add Your Comment

Communities Need Safe Drinking Water: A Rural Environmental Justice Case Study

April 3, 2024 • Community Strategies Group

Vision: Community Solutions for Safe Drinking Water

Everyone deserves to have clean drinking water. But for much of our history, rural communities and Native nations — especially historically marginalized communities — have lacked access to this basic foundation of life and health. While unsafe drinking water is an environmental justice and public health issue for both urban and rural places, rural communities face barriers related to scale and remoteness that require specialized solutions, including prioritization and support from non-rural agencies, organizations, and leaders. Across the country, rural communities and Native nations are working to build systems that work for their specific needs.

Voices: Communities Creating Clean Water Systems

Access to safe drinking water is a question of environmental justice because structural racial, economic, and geographic inequities have contributed to the causes of water contamination and hindered efforts to create needed systems for affected communities. Structural discrimination based on place, race, and class has contributed to the location of pollution sources near underinvested communities and communities of color like Ivanhoe, NC, as well as to challenges in accessing funding and other support for solutions.

The communities and organizations profiled in this case study are all working hard to design, build, and maintain effective rural clean water systems. They are envisioning and building thriving futures of equitable rural prosperity. They generously shared their thoughts, focusing on two key questions: What structural challenges keep rural communities from accessing clean water solutions? and What will it take for rural communities to drive their own clean water solutions?

“In my traditional Indigenous head, they’re not actually natural disasters, they’re human disasters. Mama, she’s just doing what she needs to do, she’s being insulted and abused. What are we going to do with those water systems [damaged by disasters]—are we going to rebuild them as is? How do we think outside the box on reconstructions? How are we going to construct water systems that are more resilient and can withstand more? How are we going to protect our source water? How are we going to lessen depletion?” Jacqueline Shirley, RCAC

Place Matters

“Why don’t they just move?” This all-too-common urban response to rural challenges — even from well-intentioned leaders with a stated focus on equity — is to question whether struggling rural communities should exist at all. There is a common and persistent sentiment that people should simply leave these places rather than receive investment and support. As shocking as this response may be, given its prevalence, it is essential to address it directly.

First, people are not pieces on a game board — they have deep relationships with family, friends, community, and land that sustain them as key parts of their history and identity. Rural place-based networks are essential to the health of rural people and communities, and they support people when formal systems fail them — and formal systems are failing rural people, especially in historically marginalized communities.

Second, for communities of color and Native communities, the land they occupy is a vital part of their history, resilience, and perseverance. These communities were often forced to their current locations because the land was less desirable, and they should not be asked to abandon these places without the investment and opportunity they have historically been denied.

Finally, rural and urban communities are also deeply interdependent — rural communities provide food, energy, manufacturing, and other resources that the country depends on, though this relationship has historically been inequitable and extractive. At the most basic level, rural communities are valuable in and of themselves and deserve to achieve equitable prosperity and thrive on their own terms.

“Rural economic justice is so different from what everybody understands — we have to do so much education. My fear is by the time people I work with get to explain what it’s like, the funds will have evaporated and folks who really need it won’t get it. I feel like we’ve missed some grants because the funders didn’t quite get the difference between rural and urban projects.” Sherri White-Williamson, EJCAN

Aspen CSG’s consultant Rebecca Huenink led the writing process for our What’s Working in Rural series. We are grateful for her contributions.

Related Posts

April 26, 2024 Energy and Environment Program & 1 more

February 22, 2024 María Ortiz Pérez

The best of the Institute, right in your inbox.

Sign up for our email newsletter

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This document contains Case Studies from the Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Program. These studies highlight some of the success and effective strategies of previous projects. to ask a question, provide feedback, or report a problem. Discover.

Environmental injustice occurred throughout the Flint water contamination incident and there are lessons we can all learn from this debacle to move forward in promoting environmental justice. Keywords: environmental justice, lead poisoning, water contamination, Flint water crisis

While the five case studies in this report highlight. successful strategies using collaborative problem-solving approaches, these and other communities also faced several common barriers in addressing each local environmental and/or public health concern:

Surveys looked at perceptions and awareness of environmental injustice of residents in the given area. Survey included eight demographic questions and 15 questions pertaining to environmental justice, with seven closed ended questions and eight open-ended questions (see appendix 1).

Case study research and mentor text analysis. In preparing for the project, we curated resources for four different case studies in environmental justice: Hurricane Katrina and the federal government’s relief efforts after the storm. Asthma and its disproportionate effect on people of color.

As part each students' coursework in Environmental Justice: Domestic and International, case studies were written on various grassroots struggles for environmental justice in the United States and all over the world. Students were asked to locate and research a struggle in environmental justice.

Map of Airport-Related Injustice and Resistance. This online interactive map brings together case studies documenting a diversity of injustice related to airport projects across the world. It was developed in collaboration between the Environmental Justice Atlas and Stay Grounded.

Students were asked to locate and research a struggle in environmental justice on behalf of a grassroots environmental organization, and then offer recommendations to that organization for continued action.

Environmental justice, a term coined by Robert Bullard, Paul Mohai, Robin Saha, and Beverly Wright in the 1980s, describes the equitable distribution of environmental benefits and harms experienced as a result of rectifying systems of oppression.

Access to safe drinking water is a question of environmental justice because structural racial, economic, and geographic inequities have contributed to the causes of water contamination and hindered efforts to create needed systems for affected communities.