Good review practice: a researcher guide to systematic review methodology in the sciences of food and health

- About this guide

- Part A: Systematic review method

- What are Good Practice points?

- Part C: The core steps of the SR process

- 1.1 Setting eligibility criteria

- 1.2 Identifying search terms

- 1.3 Protocol development

- 2. Searching for studies

- 3. Screening the results

- 4. Evaluation of included studies: quality assessment

- 5. Data extraction

- 6. Data synthesis and summary

- 7. Presenting results

- Links to current versions of the reference guidelines

- Download templates

- Food science databases

- Process management tools

- Screening tools

- Reference management tools

- Grey literature sources

- Links for access to protocol repository and platforms for registration

- Links for access to PRISMA frameworks

- Links for access to 'Risk of Bias' assessment tools for quantitative and qualitative studies

- Links for access to grading checklists

- Links for access to reporting checklists

- What questions are suitable for the systematic review methodology?

- How to assess feasibility of using the method?

- What is a scoping study and how to construct one?

- How to construct a systematic review protocol?

- How to construct a comprehensive search?

- Study designs and levels of evidence

- Download a pdf version This link opens in a new window

Scoping Study

Do you need a scoping study.

A scoping study is usually carried out before a full systematic review, to assess the breath of the research around the topic of interest. It may be used to determine how well the subject is researched and whether there is enough evidence or a real need to conduct a full systematic review. They are also planned to map keywords to relevant concepts and put the research topics in context. Scoping exercises are not mandatory and are only planned if there is a need to overview the state of the art for the topic of interest.

In relevance to systematic reviews, they are widely used to:

- investigate the volume and state of available literature,

- map concepts, keywords, and policies,

- to narrow down the scope of broad questions and make them suitable for the use of the SR methodology.

The method of scoping research topics was first developed by the EPPI-Centre to pilot systematic reviews of environmental questions. They were then extended to clinical and social science topics and are gradually being adopted in other scientific disciplines.

How to conduct a scoping study

Scoping studies are descriptive and often not comprehensive, but they provide a roadmap of literature. They follow similar steps to a systematic review process to summarise the state of current research on a topic without the need for data extraction, quality assessment or sensitivity analysis.

A standard framework proposed by Arksey, and O’Malley [2] is commonly used in clinical and healthcare research. This framework can be adapted and applied in other fields as well.

It consists of the following 5 steps: Step 1: Identifying the research question, Step 2: Identifying relevant studies, Step 3: Study selection, Step 4: Charting the data, Step 5: Collating, summarising, and reporting results.

Identifying the research question : the objective of the review question and the purpose of the scoping study determine which aspects of the study are important and what details are needed to provide an appropriate description. For example, to assess different applications of an intervention, a map of relevant literature to find all subpopulation might be planned.

Identifying relevant studies : regardless of the topic, at least 2 key elements of the research question set the foundation for a scoping study: the population and the outcome of interest. But unlike systematic review questions scoping questions seek to describe important aspects of relevant research. For instance, an intervention question can be centered around “what kind” of interventions have been applied to a particular subject for an outcome of interest.

Study selection : the search strategies of scoping studies are often designed to capture a broader spectrum of literature. As a result, the study selection process often is done at two different levels to manage the volume. First, all irrelevant and out of focus literature are removed by screening through citations or titles and abstracts. Then the screening procedure is followed for the full texts of relevant literature.

Charting the data : this stage of the scoping method can differ considerably based on the purpose. These details can include study characteristics, details of the populations, type and volume of relevant primary studies, details of various concepts and topics, etc.

Collating, summarising, and reporting results : The presentation formats are also guided by the purpose of the scoping review and often consist of tabulated forms that are used to organise and chart the data accordingly. When inputs or agreements from different field experts are needed, an optional consultation step is sometimes carried out in the end.

Good practice point : For the purpose of good practice this stage should be managed by at least 2 reviewers to make sure all relevant literatures are included. If the scoping review is intended for publication, a protocol should be developed before undertaking it, to outline the methods and objectives.

Links to access examples of scoping studies

| Organisation | Link |

| EPPI Centre | EPPI Centre you can find examples of systematic maps within social and health care contexts.

|

| CCE | you can find an example of systematic map by CCE environmental management reviews. Systematic maps are registered on cee websites and the database is free and available to search.

|

| Cochrane Library |

|

|

|

|

- << Previous: How to assess feasibility of using the method?

- Next: How to construct a systematic review protocol? >>

- Last Updated: May 17, 2024 6:08 PM

- URL: https://ifis.libguides.com/systematic_reviews

- Open access

- Published: 08 October 2021

Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application

- Micah D. J. Peters 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Casey Marnie 1 ,

- Heather Colquhoun 4 , 5 ,

- Chantelle M. Garritty 6 ,

- Susanne Hempel 7 ,

- Tanya Horsley 8 ,

- Etienne V. Langlois 9 ,

- Erin Lillie 10 ,

- Kelly K. O’Brien 5 , 11 , 12 ,

- Ӧzge Tunçalp 13 ,

- Michael G. Wilson 14 , 15 , 16 ,

- Wasifa Zarin 17 &

- Andrea C. Tricco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4114-8971 17 , 18 , 19

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 263 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scoping reviews are an increasingly common approach to evidence synthesis with a growing suite of methodological guidance and resources to assist review authors with their planning, conduct and reporting. The latest guidance for scoping reviews includes the JBI methodology and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—Extension for Scoping Reviews. This paper provides readers with a brief update regarding ongoing work to enhance and improve the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews as well as information regarding the future steps in scoping review methods development. The purpose of this paper is to provide readers with a concise source of information regarding the difference between scoping reviews and other review types, the reasons for undertaking scoping reviews, and an update on methodological guidance for the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews.

Despite available guidance, some publications use the term ‘scoping review’ without clear consideration of available reporting and methodological tools. Selection of the most appropriate review type for the stated research objectives or questions, standardised use of methodological approaches and terminology in scoping reviews, clarity and consistency of reporting and ensuring that the reporting and presentation of the results clearly addresses the review’s objective(s) and question(s) are critical components for improving the rigour of scoping reviews.

Rigourous, high-quality scoping reviews should clearly follow up to date methodological guidance and reporting criteria. Stakeholder engagement is one area where further work could occur to enhance integration of consultation with the results of evidence syntheses and to support effective knowledge translation. Scoping review methodology is evolving as a policy and decision-making tool. Ensuring the integrity of scoping reviews by adherence to up-to-date reporting standards is integral to supporting well-informed decision-making.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Given the readily increasing access to evidence and data, methods of identifying, charting and reporting on information must be driven by new, user-friendly approaches. Since 2005, when the first framework for scoping reviews was published, several more detailed approaches (both methodological guidance and a reporting guideline) have been developed. Scoping reviews are an increasingly common approach to evidence synthesis which is very popular amongst end users [ 1 ]. Indeed, one scoping review of scoping reviews found that 53% (262/494) of scoping reviews had government authorities and policymakers as their target end-user audience [ 2 ]. Scoping reviews can provide end users with important insights into the characteristics of a body of evidence, the ways, concepts or terms have been used, and how a topic has been reported upon. Scoping reviews can provide overviews of either broad or specific research and policy fields, underpin research and policy agendas, highlight knowledge gaps and identify areas for subsequent evidence syntheses [ 3 ].

Despite or even potentially because of the range of different approaches to conducting and reporting scoping reviews that have emerged since Arksey and O’Malley’s first framework in 2005, it appears that lack of consistency in use of terminology, conduct and reporting persist [ 2 , 4 ]. There are many examples where manuscripts are titled ‘a scoping review’ without citing or appearing to follow any particular approach [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This is similar to how many reviews appear to misleadingly include ‘systematic’ in the title or purport to have adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement without doing so. Despite the publication of the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and other recent guidance [ 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ], many scoping reviews continue to be conducted and published without apparent (i.e. cited) consideration of these tools or only cursory reference to Arksey and O’Malley’s original framework. We can only speculate at this stage why many authors appear to be either unaware of or unwilling to adopt more recent methodological guidance and reporting items in their work. It could be that some authors are more familiar and comfortable with the older, less prescriptive framework and see no reason to change. It could be that more recent methodologies such as JBI’s guidance and the PRISMA-ScR appear more complicated and onerous to comply with and so may possibly be unfit for purpose from the perspective of some authors. In their 2005 publication, Arksey and O’Malley themselves called for scoping review (then scoping study) methodology to continue to be advanced and built upon by subsequent authors, so it is interesting to note a persistent resistance or lack of awareness from some authors. Whatever the reason or reasons, we contend that transparency and reproducibility are key markers of high-quality reporting of scoping reviews and that reporting a review’s conduct and results clearly and consistently in line with a recognised methodology or checklist is more likely than not to enhance rigour and utility. Scoping reviews should not be used as a synonym for an exploratory search or general review of the literature. Instead, it is critical that potential authors recognise the purpose and methodology of scoping reviews. In this editorial, we discuss the definition of scoping reviews, introduce contemporary methodological guidance and address the circumstances where scoping reviews may be conducted. Finally, we briefly consider where ongoing advances in the methodology are occurring.

What is a scoping review and how is it different from other evidence syntheses?

A scoping review is a type of evidence synthesis that has the objective of identifying and mapping relevant evidence that meets pre-determined inclusion criteria regarding the topic, field, context, concept or issue under review. The review question guiding a scoping review is typically broader than that of a traditional systematic review. Scoping reviews may include multiple types of evidence (i.e. different research methodologies, primary research, reviews, non-empirical evidence). Because scoping reviews seek to develop a comprehensive overview of the evidence rather than a quantitative or qualitative synthesis of data, it is not usually necessary to undertake methodological appraisal/risk of bias assessment of the sources included in a scoping review. Scoping reviews systematically identify and chart relevant literature that meet predetermined inclusion criteria available on a given topic to address specified objective(s) and review question(s) in relation to key concepts, theories, data and evidence gaps. Scoping reviews are unlike ‘evidence maps’ which can be defined as the figural or graphical presentation of the results of a broad and systematic search to identify gaps in knowledge and/or future research needs often using a searchable database [ 15 ]. Evidence maps can be underpinned by a scoping review or be used to present the results of a scoping review. Scoping reviews are similar to but distinct from other well-known forms of evidence synthesis of which there are many [ 16 ]. Whilst this paper’s purpose is not to go into depth regarding the similarities and differences between scoping reviews and the diverse range of other evidence synthesis approaches, Munn and colleagues recently discussed the key differences between scoping reviews and other common review types [ 3 ]. Like integrative reviews and narrative literature reviews, scoping reviews can include both research (i.e. empirical) and non-research evidence (grey literature) such as policy documents and online media [ 17 , 18 ]. Scoping reviews also address broader questions beyond the effectiveness of a given intervention typical of ‘traditional’ (i.e. Cochrane) systematic reviews or peoples’ experience of a particular phenomenon of interest (i.e. JBI systematic review of qualitative evidence). Scoping reviews typically identify, present and describe relevant characteristics of included sources of evidence rather than seeking to combine statistical or qualitative data from different sources to develop synthesised results.

Similar to systematic reviews, the conduct of scoping reviews should be based on well-defined methodological guidance and reporting standards that include an a priori protocol, eligibility criteria and comprehensive search strategy [ 11 , 12 ]. Unlike systematic reviews, however, scoping reviews may be iterative and flexible and whilst any deviations from the protocol should be transparently reported, adjustments to the questions, inclusion/exclusion criteria and search may be made during the conduct of the review [ 4 , 14 ]. Unlike systematic reviews where implications or recommendations for practice are a key feature, scoping reviews are not designed to underpin clinical practice decisions; hence, assessment of methodological quality or risk of bias of included studies (which is critical when reporting effect size estimates) is not a mandatory step and often does not occur [ 10 , 12 ]. Rapid reviews are another popular review type, but as yet have no consistent, best practice methodology [ 19 ]. Rapid reviews can be understood to be streamlined forms of other review types (i.e. systematic, integrative and scoping reviews) [ 20 ].

Guidance to improve the quality of reporting of scoping reviews

Since the first 2005 framework for scoping reviews (then termed ‘scoping studies’) [ 13 ], the popularity of this approach has grown, with numbers doubling between 2014 and 2017 [ 2 ]. The PRISMA-ScR is the most up-to-date and advanced approach for reporting scoping reviews which is largely based on the popular PRISMA statement and checklist, the JBI methodological guidance and other approaches for undertaking scoping reviews [ 11 ]. Experts in evidence synthesis including authors of earlier guidance for scoping reviews developed the PRISMA-ScR checklist and explanation using a robust and comprehensive approach. Enhancing transparency and uniformity of reporting scoping reviews using the PRISMA-ScR can help to improve the quality and value of a scoping review to readers and end users [ 21 ]. The PRISMA-ScR is not a methodological guideline for review conduct, but rather a complementary checklist to support comprehensive reporting of methods and findings that can be used alongside other methodological guidance [ 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. For this reason, authors who are more familiar with or prefer Arksey and O’Malley’s framework; Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien’s extension of that framework or JBI’s methodological guidance could each select their preferred methodological approach and report in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR checklist.

Reasons for conducting a scoping review

Whilst systematic reviews sit at the top of the evidence hierarchy, the types of research questions they address are not suitable for every application [ 3 ]. Many indications more appropriately require a scoping review. For example, to explore the extent and nature of a body of literature, the development of evidence maps and summaries; to inform future research and reviews and to identify evidence gaps [ 2 ]. Scoping reviews are particularly useful where evidence is extensive and widely dispersed (i.e. many different types of evidence), or emerging and not yet amenable to questions of effectiveness [ 22 ]. Because scoping reviews are agnostic in terms of the types of evidence they can draw upon, they can be used to bring together and report upon heterogeneous literature—including both empirical and non-empirical evidence—across disciplines within and beyond health [ 23 , 24 , 25 ].

When deciding between whether to conduct a systematic review or a scoping review, authors should have a strong understanding of their differences and be able to clearly identify their review’s precise research objective(s) and/or question(s). Munn and colleagues noted that a systematic review is likely the most suitable approach if reviewers intend to address questions regarding the feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness or effectiveness of a specified intervention [ 3 ]. There are also online resources for prospective authors [ 26 ]. A scoping review is probably best when research objectives or review questions involve exploring, identifying, mapping, reporting or discussing characteristics or concepts across a breadth of evidence sources.

Scoping reviews are increasingly used to respond to complex questions where comparing interventions may be neither relevant nor possible [ 27 ]. Often, cost, time, and resources are factors in decisions regarding review type. Whilst many scoping reviews can be quite large with numerous sources to screen and/or include, there is no expectation or possibility of statistical pooling, formal risk of bias rating, and quality of evidence assessment [ 28 , 29 ]. Topics where scoping reviews are necessary abound—for example, government organisations are often interested in the availability and applicability of tools to support health interventions, such as shared decision aids for pregnancy care [ 30 ]. Scoping reviews can also be applied to better understand complex issues related to the health workforce, such as how shift work impacts employee performance across diverse occupational sectors, which involves a diversity of evidence types as well as attention to knowledge gaps [ 31 ]. Another example is where more conceptual knowledge is required, for example, identifying and mapping existing tools [ 32 ]. Here, it is important to understand that scoping reviews are not the same as ‘realist reviews’ which can also be used to examine how interventions or programmes work. Realist reviews are typically designed to ellucide the theories that underpin a programme, examine evidence to reveal if and how those theories are relevant and explain how the given programme works (or not) [ 33 ].

Increased demand for scoping reviews to underpin high-quality knowledge translation across many disciplines within and beyond healthcare in turn fuels the need for consistency, clarity and rigour in reporting; hence, following recognised reporting guidelines is a streamlined and effective way of introducing these elements [ 34 ]. Standardisation and clarity of reporting (such as by using a published methodology and a reporting checklist—the PRISMA-ScR) can facilitate better understanding and uptake of the results of scoping reviews by end users who are able to more clearly understand the differences between systematic reviews, scoping reviews and literature reviews and how their findings can be applied to research, practice and policy.

Future directions in scoping reviews

The field of evidence synthesis is dynamic. Scoping review methodology continues to evolve to account for the changing needs and priorities of end users and the requirements of review authors for additional guidance regarding terminology, elements and steps of scoping reviews. Areas where ongoing research and development of scoping review guidance are occurring include inclusion of consultation with stakeholder groups such as end users and consumer representatives [ 35 ], clarity on when scoping reviews are the appropriate method over other synthesis approaches [ 3 ], approaches for mapping and presenting results in ways that clearly address the review’s research objective(s) and question(s) [ 29 ] and the assessment of the methodological quality of scoping reviews themselves [ 21 , 36 ]. The JBI Scoping Review Methodology group is currently working on this research agenda.

Consulting with end users, experts, or stakeholders has been a suggested but optional component of scoping reviews since 2005. Many of the subsequent approaches contained some reference to this useful activity. Stakeholder engagement is however often lost to the term ‘review’ in scoping reviews. Stakeholder engagement is important across all knowledge synthesis approaches to ensure relevance, contextualisation and uptake of research findings. In fact, it underlines the concept of integrated knowledge translation [ 37 , 38 ]. By including stakeholder consultation in the scoping review process, the utility and uptake of results may be enhanced making reviews more meaningful to end users. Stakeholder consultation can also support integrating knowledge translation efforts, facilitate identifying emerging priorities in the field not otherwise captured in the literature and may help build partnerships amongst stakeholder groups including consumers, researchers, funders and end users. Development in the field of evidence synthesis overall could be inspired by the incorporation of stakeholder consultation in scoping reviews and lead to better integration of consultation and engagement within projects utilising other synthesis methodologies. This highlights how further work could be conducted into establishing how and the extent to which scoping reviews have contributed to synthesising evidence and advancing scientific knowledge and understandings in a more general sense.

Currently, many methodological papers for scoping reviews are published in healthcare focussed journals and associated disciplines [ 6 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. Another area where further work could also occur is to gain greater understanding on how scoping reviews and scoping review methodology is being used across disciplines beyond healthcare including how authors, reviewers and editors understand, recommend or utilise existing guidance for undertaking and reporting scoping reviews.

Whilst available guidance for the conduct and reporting of scoping review has evolved over recent years, opportunities remain to further enhance and progress the methodology, uptake and application. Despite existing guidance, some publications using the term ‘scoping review’ continue to be conducted without apparent consideration of available reporting and methodological tools. Because consistent and transparent reporting is widely recongised as important for supporting rigour, reproducibility and quality in research, we advocate for authors to use a stated scoping review methodology and to transparently report their conduct by using the PRISMA-ScR. Selection of the most appropriate review type for the stated research objectives or questions, standardising the use of methodological approaches and terminology in scoping reviews, clarity and consistency of reporting and ensuring that the reporting and presentation of the results clearly addresses the authors’ objective(s) and question(s) are also critical components for improving the rigour of scoping reviews. We contend that whilst the field of evidence synthesis and scoping reviews continues to evolve, use of the PRISMA-ScR is a valuable and practical tool for enhancing the quality of scoping reviews, particularly in combination with other methodological guidance [ 10 , 12 , 44 ]. Scoping review methodology is developing as a policy and decision-making tool, and so ensuring the integrity of these reviews by adhering to the most up-to-date reporting standards is integral to supporting well informed decision-making. As scoping review methodology continues to evolve alongside understandings regarding why authors do or do not use particular methodologies, we hope that future incarnations of scoping review methodology continues to provide useful, high-quality evidence to end users.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials are available upon request.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Article Google Scholar

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:15.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Peters M, Marnie C, Tricco A, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Paiva L, Dalmolin GL, Andolhe R, dos Santos W. Absenteeism of hospital health workers: scoping review. Av enferm. 2020;38(2):234–48.

Visonà MW, Plonsky L. Arabic as a heritage language: a scoping review. Int J Biling. 2019;24(4):599–615.

McKerricher L, Petrucka P. Maternal nutritional supplement delivery in developing countries: a scoping review. BMC Nutr. 2019;5(1):8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fusar-Poli P, Salazar de Pablo G, De Micheli A, et al. What is good mental health? A scoping review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:33–46.

Jowsey T, Foster G, Cooper-Ioelu P, Jacobs S. Blended learning via distance in pre-registration nursing education: a scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020;44:102775.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid-based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis: JBI; 2020.

Google Scholar

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):28.

Sutton A, Clowes M, Preston L, Booth A. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Inf Libr J. 2019;36(3):202–22.

Brady BR, De La Rosa JS, Nair US, Leischow SJ. Electronic cigarette policy recommendations: a scoping review. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(1):88–104.

Truman E, Elliott C. Identifying food marketing to teenagers: a scoping review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):67.

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224.

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. All in the family: systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):183.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Ghassemi M, et al. Same family, different species: methodological conduct and quality varies according to purpose for five types of knowledge synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;96:133–42.

Barker M, Adelson P, Peters MDJ, Steen M. Probiotics and human lactational mastitis: a scoping review. Women Birth. 2020;33(6):e483–e491.

O’Donnell N, Kappen DL, Fitz-Walter Z, Deterding S, Nacke LE, Johnson D. How multidisciplinary is gamification research? Results from a scoping review. Extended abstracts publication of the annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play. Amsterdam: Association for Computing Machinery; 2017. p. 445–52.

O’Flaherty J, Phillips C. The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: a scoping review. Internet High Educ. 2015;25:85–95.

Di Pasquale V, Miranda S, Neumann WP. Ageing and human-system errors in manufacturing: a scoping review. Int J Prod Res. 2020;58(15):4716–40.

Knowledge Synthesis Team. What review is right for you? 2019. https://whatreviewisrightforyou.knowledgetranslation.net/

Lv M, Luo X, Estill J, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a scoping review. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(15):2000125.

Shemilt I, Simon A, Hollands GJ, et al. Pinpointing needles in giant haystacks: use of text mining to reduce impractical screening workload in extremely large scoping reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(1):31–49.

Khalil H, Bennett M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Peters M. Evaluation of the JBI scoping reviews methodology by current users. Int J Evid-based Healthc. 2020;18(1):95–100.

Kennedy K, Adelson P, Fleet J, et al. Shared decision aids in pregnancy care: a scoping review. Midwifery. 2020;81:102589.

Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Recio-Saucedo A, Griffiths P. Characteristics of shift work and their impact on employee performance and wellbeing: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;57:12–27.

Feo R, Conroy T, Wiechula R, Rasmussen P, Kitson A. Instruments measuring behavioural aspects of the nurse–patient relationship: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(11-12):1808–21.

Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):33.

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–4.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Rios P, et al. Engaging policy-makers, health system managers, and policy analysts in the knowledge synthesis process: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):31.

Cooper S, Cant R, Kelly M, et al. An evidence-based checklist for improving scoping review quality. Clin Nurs Res. 2021;30(3):230–240.

Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, et al. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):208.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Rios P, Pham B, Straus SE, Langlois EV. Barriers, facilitators, strategies and outcomes to engaging policymakers, healthcare managers and policy analysts in knowledge synthesis: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e013929.

Denton M, Borrego M. Funds of knowledge in STEM education: a scoping review. Stud Eng Educ. 2021;1(2):71–92.

Masta S, Secules S. When critical ethnography leaves the field and enters the engineering classroom: a scoping review. Stud Eng Educ. 2021;2(1):35–52.

Li Y, Marier-Bienvenue T, Perron-Brault A, Wang X, Pare G. Blockchain technology in business organizations: a scoping review. In: Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii international conference on system sciences ; 2018. https://core.ac.uk/download/143481400.pdf

Houlihan M, Click A, Wiley C. Twenty years of business information literacy research: a scoping review. Evid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2020;15(4):124–163.

Plug I, Stommel W, Lucassen P, Hartman T, Van Dulmen S, Das E. Do women and men use language differently in spoken face-to-face interaction? A scoping review. Rev Commun Res. 2021;9:43–79.

McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, et al. Reporting scoping reviews - PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the other members of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) working group as well as Shazia Siddiqui, a research assistant in the Knowledge Synthesis Team in the Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto.

The authors declare that no specific funding was received for this work. Author ACT declares that she is funded by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis. KKO is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Episodic Disability and Rehabilitation with the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of South Australia, UniSA Clinical and Health Sciences, Rosemary Bryant AO Research Centre, Playford Building P4-27, City East Campus, North Terrace, Adelaide, 5000, South Australia

Micah D. J. Peters & Casey Marnie

Adelaide Nursing School, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, 101 Currie St, Adelaide, 5001, South Australia

Micah D. J. Peters

The Centre for Evidence-based Practice South Australia (CEPSA): a Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, 5006, Adelaide, South Australia

Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, Terrence Donnelly Health Sciences Complex, 3359 Mississauga Rd, Toronto, Ontario, L5L 1C6, Canada

Heather Colquhoun

Rehabilitation Sciences Institute (RSI), University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 160-500 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1V7, Canada

Heather Colquhoun & Kelly K. O’Brien

Knowledge Synthesis Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 1053 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1Y 4E9, Canada

Chantelle M. Garritty

Southern California Evidence Review Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, 90007, USA

Susanne Hempel

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 774 Echo Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 5N8, Canada

Tanya Horsley

Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH), World Health Organisation, Avenue Appia 20, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland

Etienne V. Langlois

Sunnybrook Research Institute, 2075 Bayview Ave, Toronto, Ontario, M4N 3M5, Canada

Erin Lillie

Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 160-500 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1V7, Canada

Kelly K. O’Brien

Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation (IHPME), University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 155 College Street 4th Floor, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 3M6, Canada

UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organisation, Avenue Appia 20, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland

Ӧzge Tunçalp

McMaster Health Forum, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Michael G. Wilson

Department of Health Evidence and Impact, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, 209 Victoria Street, East Building, Toronto, Ontario, M5B 1T8, Canada

Wasifa Zarin & Andrea C. Tricco

Epidemiology Division and Institute for Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, 155 College St, Room 500, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 3M7, Canada

Andrea C. Tricco

Queen’s Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, School of Nursing, Queen’s University, 99 University Ave, Kingston, Ontario, K7L 3N6, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MDJP, CM, HC, CMG, SH, TH, EVL, EL, KKO, OT, MGW, WZ and AT all made substantial contributions to the conception, design and drafting of the work. MDJP and CM prepared the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrea C. Tricco .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

Author ACT is an Associate Editor for the journal. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Peters, M.D.J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H. et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev 10 , 263 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

Download citation

Received : 29 January 2021

Accepted : 27 September 2021

Published : 08 October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scoping reviews

- Evidence synthesis

- Research methodology

- Reporting guidelines

- Methodological guidance

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 26 July 2016

Advancing scoping study methodology: a web-based survey and consultation of perceptions on terminology, definition and methodological steps

- Kelly K. O’Brien 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Heather Colquhoun 3 , 4 ,

- Danielle Levac 5 ,

- Larry Baxter 6 ,

- Andrea C. Tricco 7 ,

- Sharon Straus 7 ,

- Lisa Wickerson 3 , 8 ,

- Ayesha Nayar 1 ,

- David Moher 9 , 10 &

- Lisa O’Malley 11

BMC Health Services Research volume 16 , Article number: 305 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

25k Accesses

16 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scoping studies (or reviews) are a method used to comprehensively map evidence across a range of study designs in an area, with the aim of informing future research practice, programs and policy. However, no universal agreement exists on terminology, definition or methodological steps. Our aim was to understand the experiences of, and considerations for conducting scoping studies from the perspective of academic and community partners. Primary objectives were to 1) describe experiences conducting scoping studies including strengths and challenges; and 2) describe perspectives on terminology, definition, and methodological steps.

We conducted a cross-sectional web-based survey with clinicians, educators, researchers, knowledge users, representatives from community-based organizations, graduate students, and policy stakeholders with experience and/or interest in conducting scoping studies to gain an understanding of experiences and perspectives on the conduct and reporting of scoping studies. We administered an electronic self-reported questionnaire comprised of 22 items related to experiences with scoping studies, strengths and challenges, opinions on terminology, and methodological steps. We analyzed questionnaire data using descriptive statistics and content analytical techniques. Survey results were discussed during a multi-stakeholder consultation to identify key considerations in the conduct and reporting of scoping studies.

Of the 83 invitations, 54 individuals (65 %) completed the scoping questionnaire, and 48 (58 %) attended the scoping study meeting from Canada, the United Kingdom and United States. Many scoping study strengths were dually identified as challenges including breadth of scope, and iterative process. No consensus on terminology emerged, however key defining features that comprised a working definition of scoping studies included the exploratory mapping of literature in a field; iterative process, inclusion of grey literature; no quality assessment of included studies, and an optional consultation phase. We offer considerations for the conduct and reporting of scoping studies for researchers, clinicians and knowledge users engaging in this methodology.

Conclusions

Lack of consensus on scoping terminology, definition and methodological steps persists. Reasons for this may be attributed to diversity of disciplines adopting this methodology for differing purposes. Further work is needed to establish guidelines on the reporting and methodological quality assessment of scoping studies.

Peer Review reports

Scoping studies are a method to comprehensively synthesize evidence across a range of study designs. Scoping studies (or reviews) may be defined as “exploratory projects that systematically map the literature available on a topic, identifying key concepts, theories, sources of evidence and gaps in the research” [ 1 ]. Researchers may undertake a scoping study to examine the extent, range and nature of research activity, determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review, synthesize and disseminate findings, or identify gaps in existing literature [ 2 ].

Scoping studies have become increasingly popular in health research. The number of scoping studies has increased immensely in the past six years with over half of scoping studies published after 2012, demonstrating their growing potential to inform research agendas, and policy and practice recommendations [ 3 ]. Despite their increasing use and abundant promise for impact on practice, policy and research, no clear criteria exist to guide and evaluate scoping study rigor or reporting. While quality criteria and reporting guidelines exist for other methodological approaches, such as systematic reviews [ 4 – 6 ], and clinical practice guidelines [ 7 ], none have been established for scoping studies. Specific guidelines may enhance the reporting of scoping studies that address features related to breadth of purpose, evidence inclusion, and iterative nature of scoping studies that are unique from other syntheses.

In 2005, Arksey and O’Malley published a six-stage methodological framework for conducting scoping studies: identifying the research question, searching for relevant studies, selecting studies, charting the data, collating, summarizing and reporting the results, and consulting with stakeholders to inform or validate study findings [ 2 ]. In 2010, Levac et al. proposed recommendations, building on each stage of the scoping study framework, highlighting considerations for advancement, application and relevance of scoping studies in health research [ 8 ]. Additional recommendations for scoping study methodology have since been published, demonstrating the ongoing need and interest for advancement of this field [ 9 – 11 ]. Despite the progress to date, there remains no universal agreement on the definition or methodological steps for this approach [ 12 ].

We think it is important to address the methodological quality of this emerging method of evidence synthesis. Establishing a better understanding of current experiences including strengths and challenges of conducting scoping studies and exchanging knowledge and perspectives on terminology and methodological steps among stakeholders who share scoping study expertise is a first step to collaboratively advancing this methodology and providing a foundation for future development of methodological criteria in this field.

Our aim was to understand the experiences of, and considerations for conducting scoping studies from the perspective of clinicians, educators, researchers, graduate students and knowledge users with interest and experience in this methodology. Primary objectives were to 1) describe experiences conducting scoping studies including strengths and challenges, and 2) describe perspectives on terminology, definition and methodological steps. A secondary objective was to 3) discuss considerations in the conduct and reporting of scoping studies. Results will increase awareness of the methodological issues among researchers, clinicians and members of the knowledge user community to help inform future efforts on guidance of scoping study methodology.

We conducted a web-based survey followed by a multi-stakeholder consultation meeting. For the purposes of this work, we used the term ‘scoping study’ throughout in accordance with the original Arksey and O’Malley Framework [ 2 ].

We conducted a cross-sectional web-based survey with a sample of researchers, health professionals, graduate students, policy makers and people living with chronic diseases in Canada, the United States and United Kingdom who possessed expertise and interest in scoping study and knowledge synthesis methodology. Individuals were invited to participate in the survey followed by a 2 day scoping study meeting to gain an understanding of the experiences, including strengths and challenges in conducting scoping studies, and obtain views on terminology, definition and methodological steps inherent to rigorous conduct of scoping studies.

We discussed the survey results in a multi-stakeholder scoping study consultation meeting with clinicians, academics, graduate students, representatives from community-based organizations, community members living with chronic illnesses, and policy and funding stakeholders. The goal of this meeting was to translate research evidence related to scoping study methodology and to establish priorities for the future development of criteria in the conduct and reporting of scoping studies [ 13 ].

We received ethics approval from the University of Toronto Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (Protocol Reference #: 31214).

Participants

We administered a web-based self-administered questionnaire using a modified Dillman approach [ 14 ] and FluidSurveys [ 15 ] to all stakeholders who were invited to attend a 2 day scoping meeting in Toronto, Canada in June 2015.

We used a combination of snowball and purposive sampling to identify approximately 80 researchers, clinicians, graduate students, policy makers, and knowledge users in Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States. We asked researchers, knowledge users and collaborators for names and email addresses of individuals who they felt possessed an interest and expertise in scoping study methodology. Invited individuals also provided names and contact information of potential additional invitees. This process was critical in order to mobilize diverse participants who represent both developers and users of scoping studies in clinical practice, research and policy.

Given the consultative nature of this work, participants were likely persons whom members of the team previously worked with in an education, research or community-based capacity. In the case of the scoping study survey, completed questionnaires were considered implied consent. In the case of the meeting consultation, consent was based on the individual accepting the invitation and attending the meeting. All participants were invited to provide their name to be acknowledged in the manuscript (see Acknowledgements).

Data collection

Scoping study questionnaire.

We developed a scoping study questionnaire to describe the experiences, and views on scoping study terminology and methodological steps. The questionnaire was developed and pre-tested by four members of the scoping study team. The questionnaire took approximately 20 min to complete and included 22 items across six domains: 1) personal information; 2) experiences conducting scoping studies; 3) strengths and challenges of conducting scoping studies; 4) opinions on scoping study terminology, 5) key considerations for methodological steps and rigor, and 6) additional comments (see Additional file 1 – Scoping Study Questionnaire).

We sent an initial invitation email with an overview of the purpose of the scoping study survey and a link to the questionnaire. We sent three thank you / reminder emails at 1, 2 and 4 weeks after the initial email, thanking those who completed the questionnaire and asking those who had not responded to complete the questionnaire.

Scoping consultation meeting

The 2-day scoping study consultation meeting summarized the state of evidence in the field of scoping studies in the context of knowledge synthesis methodology. Sessions included a combination of structured presentations from speakers, a panel, and large and small group discussion segments to facilitate knowledge transfer and exchange of opinions for establishing a common definition and consensus surrounding methodological steps of scoping studies. Results from the web-based survey pertaining to terminology, definition and methodological steps were presented throughout the meeting followed by opportunities for discussion (see Additional file 2 – Scoping Study Meeting Agenda).

Perspectives on the scoping survey results were documented at the multi-stakeholder consultation through the following methods: 1) participants were asked to submit written considerations about the new and emerging issues in the field of scoping study methodology; 2) participants were encouraged to express their ideas as they pertained to the scoping study survey results related to terminology, definition, and methodological steps during the meeting discussion; and 3) six graduate student rapporteurs documented the discussion throughout the meeting. Responses on the questionnaire included information on the experiences, strengths and challenges of conducting scoping studies (objective #1). Collectively, data pertaining to perspectives and recommendations derived from the survey questionnaire and meeting sources provided the foundation for perspectives on terminology, definition and methodological steps (objective #2) and identifying key considerations for the conduct and reporting of scoping studies (objective #3).

Scoping Study Questionnaire : We calculated the view, participation and completion rates of the online questionnaire [ 16 ]. We analyzed questionnaire data using descriptive statistics using frequencies and percent (categorical items) and median and interquartile ranges (continuous items). We analyzed open ended response items using content analysis [ 17 ]. Three members of the core research team independently read the open-ended questions from the questionnaire to obtain an overall impression of the responses; and met to discuss overall impressions (KKO, HC, DL).

Scoping Study Meeting Rapporteur Notes : We analyzed the rapporteur data capturing the discussion at the scoping study meeting using content analysis [ 17 ]. Two members of the team independently read the rapporteur notes to obtain an overall impression of the reflections; and met to discuss overall impressions (KKO, LW). Rapporteur notes were independently coded by two members of the team (KKO, LW). Coding involved highlighting words or captions that captured key thoughts and concepts related to scoping study methodology. These codes were then clustered into broader categories that were collectively used to supplement the perspectives on terminology, definition and methodological steps and inform the key considerations for conduct and reporting of scoping studies.

The three reviewers for the questionnaire data (KKO, HC, DL) and two reviewers for the rapporteur summaries (KKO and LW) met twice to discuss the findings from the content analysis and six authors (KKO, LW, DL, HC, LB, AN) reviewed a preliminary version of the key considerations for refinement.

Results and discussion

Of the 83 invitations, 63 (76 %; 63/83) viewed the questionnaire, and 54 (65 %; 54/83) completed the questionnaire [ 16 ]. The majority of respondents self-identified as researchers, coordinators, or managers (54 %), followed by graduate students (24 %), knowledge translation brokers (7 %), educators (4 %), community members (4 %), clinicians (2 %), policy makers (2 %), librarians (2 %), and consultants (2 %). Most respondents were from Canada (92 %; n = 50), with two participants from the UK (4 %) and two from the United States (4 %).

The scoping meeting was attended by 48 participants comprised of researchers (42 %; 20/48), graduate student trainees (29 %; 14/48), educators (13 %; 6/48), service providers (8 %; 4/48); community members (2 %; 1/48); and other professions (consultant, civil society representative and information specialist) (6 %; 3/48). The majority of meeting participants were affiliated with universities or academic institutions (58 %; 28/48), followed by community-based, not-for-profit, knowledge broker/translation, and government organizations (23 %; 11/48), research organizations (13 %; 6/48), and hospitals (6 %; 3/48). Most participants were from Canada (94 %; n = 45), with two from the United States (4 %), and one from the UK (2 %). Given our recruitment strategy was primarily through snowball sampling, participants were knowledgeable or had an interest in the field of scoping studies.

We report the findings as derived from the scoping study questionnaire related to experiences, strengths and challenges of conducting scoping studies (objective #1), followed by collective interpretations from the survey questionnaire and meeting consultation as they relate to terminology, definition and methodological steps (objective #2). We then reflect on key considerations that emerged from the scoping questionnaire and meeting consultation for moving forward (objective #3).

Experiences, strengths and challenges of conducting scoping studies

Experience with scoping studies.

The majority of questionnaire respondents (85 %) had experience engaging in a scoping study with most (87 %) having completed at least one scoping study and almost half having had a scoping study published or in press in a peer-reviewed journal (46 %; 25/54) (Table 1 ). Roles ranged from conceptualizing and refining the research question, oversight, conducting literature searches / reviews, scanning titles and abstracts to determine study inclusion, data extraction, synthesizing the evidence, writing-up, and disseminating findings. Most respondents engaged in scoping studies to examine the extent, range, nature of research activity (91 %), to map a body of evidence, and to identify gaps in the field; which was similarly documented as common purposes for conducting scoping studies [ 11 ] (Table 1 ).

Of the 46 respondents (85 %) who were involved in a scoping study, 19 (41 %) had engaged in a stakeholder consultation, 7 (37 %) of which went through Research Ethics Board (REB) review for the process. Reasons for pursuing REB review were because investigators intended to publish results and/or conducted interviews with ‘experts’. Respondents chose not go through REB review when the scoping study was conducted by a community organization, when there was no formal REB process available, when respondents did not plan to publish in an academic journal, when the scoping study was done to inform a systematic review, or the consultation involved stakeholders as part of a steering committee who provided feedback throughout the study. Finally, the majority of participants utilized a framework opposed to only half of investigators in a previous review suggesting there is increasing appetite for adopting a more rigorous approach to this methodology [ 11 ].

Strengths and challenges of scoping studies

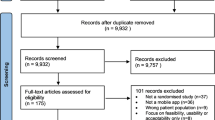

Many scoping study strengths were dually identified as challenges (Fig. 1 ). Respondents described the strengths of scoping studies in relation to their ability to provide an ‘ overview of the state of evidence in a field’ their ‘ breadth’ , ‘ broad scope’ and ‘ tool for mapping broad and diverse topics’ to inform future work. Strengths associated with scoping study methodology included their flexibility , inclusion of published and unpublished (grey) literature, inclusion of literature with a wide range of study designs and methodologies, and the potential to combine qualitative and quantitative synthesis approaches. Respondents highlighted the systematic process (replicable, transparent, rigorous) that provides the ability to explore and synthesize evidence on a newly emerging topic (or topic with little published evidence), using an approach that is ‘ not as rigid as systematic reviews’ . Additional strengths included the ability for scoping studies to focus on the state of research activity rather than evaluate the quality of existing literature, the ability to assist policy makers to make evidence-informed decisions, and engagement of stakeholders with expertise in a given content area throughout all stages of the process.

Strengths and Challenges of Scoping Studies

Challenges dually identified as strengths of scoping studies included the flexibility, broad scope and inclusion of grey literature which posed challenges when trying to establish boundaries to the study scope (Fig. 1 ). One challenge included the variability in terminology and unclear definitions of concepts of interest, which made identifying the study scope difficult. The flexible and iterative process of defining (and redefining) the research question, search strategy and selection criteria required increased time and resources which was difficult to ascertain at the beginning of the study. The broad scope combined with lack of clarity around boundaries left some with an overwhelming amount of data, posing challenges for feasibility as scoping studies were often time-consuming and took longer than originally anticipated. This could place a scoping study at risk of quickly becoming out of date. Some respondents expressed challenges with the utility of a final product or outcome that was sometimes uncertain at the outset of the study: “Sometimes it feels like a lot of work just to identify gaps or determine that more research is needed.”

Respondents expressed challenges with the lack of detailed steps, guidance, standards, or methodology (particularly if and how to synthesize data from selected studies). They described the need for more clarification about the need and steps associated with the consultation phase. Some described difficulty finding unpublished (or grey) forms of evidence, synthesizing evidence from diverse sources with different types of data, diversity of reviewers or investigators involved, and lack of clarity of how to conduct the synthesis (or analysis) leaving some with an overwhelming amount of data if the scope was broad; and the lack of quality appraisal that resulted in the need for caution in interpretation. Some described challenges with the feasibility conducting the stakeholder consultation. Finally, respondents described challenges of reporting results succinctly, and the difficulty publishing scoping studies with limitations in journal word counts.

Scoping terminology

The majority of respondents preferred the term ‘scoping review’ (68 %) over ‘scoping study’ (11 %) with remaining respondents unsure or having no opinion suggesting either term could be appropriate, depending on the study (20 %) (Table 2 ).

Respondents who preferred the term ‘scoping review’ tended to focus on the literature review component of the methodology stating ‘review’ is “ a more accurate description ”, “ consistent with methods of evidence synthesis such as systematic reviews and meta-analysis methods” . As one respondent stated:

“the term “review” aligns with the purpose of the research….to review what was published in the literature, and to do so in a somewhat systematic way. Although it technically is a “study”, calling it a “review” seems to be more precise in my mind.”

Respondents who preferred ‘scoping study’ did so because they “ take into account the analysis (thematic) component which differs from the mere summary or synthesis in other types of reviews” . Another participant stated his/her preference in relation to the analytical difference between scoping studies and other types of knowledge syntheses:

“Scoping studies have distinct goals and thus should be viewed as distinct entities and not as “less than” systematic reviews…. the intent is not only to review the literature but to conceptualize it in a manner that speaks to the research question. I do not feel that the term ‘review’ covers the extent of analytic work of this type of study.”

Others felt that the term ‘scoping study’ provided clear language that helps distinguish them from ‘scoping reviews’ that have become a “ catch-all term for everything that is not a systematic review” . Finally, scoping study terminology was preferred by those who felt the term ‘study’ encompassed the entire methodology, the literature (or evidence) review phase as well as the consultation phase. It was also acknowledged as the term coined by Arksey and O’Malley, the developers of the original Scoping Study Framework.

Defining features of scoping studies

Respondents described defining features of scoping studies, many of which were similar to strengths of the methodology (Table 1 ). Participants described the distinction of scoping studies from other forms of knowledge syntheses such as literature reviews, systematic or rapid reviews: “ [scoping studies] are not as rigorous as systematic reviews but more distinctive in methodology” and are “less likely to be strongly influenced by opinion than a traditional literature review”.

Others struggled to distinguish scoping studies from other forms of syntheses as one participant stated:

“This is challenging to distinguish. In many aspects scoping reviews are similar to systematic reviews in methodology with the capture of the broad research question, broad eligibility criteria, no quality assessment and consultation exercise.”

Given the similarities in comprehensiveness and systematic nature, “the difference in method is not as great as some might think”. Similarly another participant did not perceive there to be distinctions between scoping studies and other syntheses:

“I do not think that there is anything inherently distinct about scoping study methodology…I think that the ‘scoping study phenomenon’ is the product of a methodological title being applied widely and loosely for reasons that are completely logical given the current context of health sciences research.”

Overall, participants described similarities between scoping and systematic reviews in relation to transparency, rigor, and systematic nature, whereas the distinction between scoping and literature reviews were easier to distinguish with scoping studies taking on a more systematic and rigorous nature of methodology.

Methodological steps

The majority of respondents to the scoping questionnaire (90 %) agreed that scoping studies should involve grey literature, and 31 % (16/54) felt that quality assessments of individual included studies should become a part of scoping methodology. Some respondents felt that quality assessment depends on the nature of the research question; for example if a question pertained to effectiveness of an intervention then quality assessment may be critical opposed to the exploration or description of an emerging topic where there may be less formulated evidence in a field.

Perspectives on terminology, definition, and methodological steps

The following results include collective interpretations of the survey results from the meeting consultation as they relate to terminology, definition and methodological steps.

Terminology

Despite our intention, no consensus was achieved related to scoping terminology. Two opposing views appeared to emerge from the meeting: individuals who align scoping reviews (note the terminology) with other types of systematic reviews, and those who view scoping studies as distinct from other reviews. This may explain the lack of consensus surrounding terminology, methodological steps and positivist versus constructivist approaches (associated with reviews versus studies, respectively) to scoping the field of evidence. Others felt the distinction between ‘study’ over ‘review’ was attributed to the higher analytical level of synthesis of data from existing evidence (rather than reporting frequencies of literature characteristics) as well as the consultation phase that requires primary data collection and qualitative approaches to analysis, which results in a new outcome or product that is relevant and meaningful to the field; examples include a framework of existing evidence, or recommendations for future research priorities.

While the majority of questionnaire respondents (68 %) preferred the term scoping review (over study), the meeting provided insight to the historical development of the Scoping Study Framework from the perspective of Arksey and O’Malley. The preference for scoping review seemed to emerge from the methodological steps referencing review of the literature, and feeling that ‘scoping review’ provided more legitimacy and rigor if considered in the same classification of systematic reviews, which have clear established steps and reporting criteria [ 24 ]. However, the term ‘scoping study’ was intentionally chosen to distance itself from the ‘systematic review’ specifically aimed at determining clinical effectiveness of an intervention, to broaden awareness and inclusion of other types of evidence beyond the randomized controlled trial which may be traditionally favored in systematic reviews [ 13 ]. Scoping studies are intended to map a field and expose gaps in evidence. Developers borrowed elements from systematic reviews such as scoping studies as rigorous, systematic, replicable, and transparent while adding elements such as the iterative or flexible nature of the steps, lack of quality appraisal and addition of the consultation phase. Nevertheless, results suggest scoping studies may have evolved where researchers view them as a form of knowledge synthesis, hence adopting the term ‘review’. Overall, the way in which we distinguish scoping studies from other forms of reviews within the broader context of syntheses will be important for moving forward.

Challenges adopting universal terminology and a definition may be a reflection of the complex and diverse reasons in which someone may adopt scoping methodology, the diversity of research questions which this methodology may address (i.e. Arksey and O’Malley discuss four possible purposes alone), and the uptake across diverse disciplines using the methodology.

Another challenge distinguishing scoping studies from scoping reviews may be attributed to the systematic nature which both approaches adopt. Most survey respondents believed scoping studies (and reviews) are carried out systematically and it is the systematic characteristic that differentiates scoping studies (or reviews) from literature reviews. However, both terms (study and review) affiliate with similar characteristics with respect to their systematic, comprehensive and transparent nature, which may lead to difficulty in establishing how scoping studies are distinguished from other types of reviews. Peters et al. expressed the importance of distinguishing between scoping reviews and ‘comprehensive’ systematic reviews that also rely on synthesizing evidence from different study designs [ 25 ]: ‘While in a scoping review the goal is to determine what kind of evidence is available on the topic and to represent this evidence by mapping or charting the data, comprehensive systematic reviews are designed to answer a series of related but still very specific questions’ (Page 8) [ 25 ]. Scoping studies involve mapping the evidence describing the quantity, design and characteristics in a field opposed to systematic reviews which tend to address a specific narrowly defined research question [ 23 ]. This further highlights the importance of choosing the synthesis approach (and terminology) that best addresses the original research question. For instance, scoping studies may be better suited to exploratory questions in emerging fields that involve complex multi-factorial interventions with less high level randomized controlled trial evidence (e.g. rehabilitation), or areas with an abundance of grey but relevant literature that has not traditionally been taken up in a given field (e.g. policy). For example, scoping studies have been used to explore the emerging field of HIV and aging [ 26 ]. Authors characterized the literature describing the impact of aging on the health of older adults living with HIV (e.g. types of study design, participants, interventions (if applicable), health care domains addressed) and provided recommendations for future HIV and aging research [ 26 ].

Meeting participants generally agreed on a working definition of scoping studies as proposed by Colquhoun et al. [ 12 ] adapted to: ‘ a scoping study or scoping review is a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to an emerging area or field by systematically and iteratively searching, selecting, summarizing and potentially synthesizing existing knowledge .’

Debate emerged over the extent to which data are summarized or synthesized in scoping studies, whether synthesis is a defining characteristic of scoping studies and whether this makes it distinct from a literature review. For instance, the step of ‘collating the data’ could span the spectrum of pure counting of characteristics (descriptive) to a more analytical (thematic or content analysis) for variables of interest such as characteristics of interventions, outcomes, and authors conclusions. Debate also ensued over whether scoping studies should always yield recommendations for practice and policy, which require a higher level of synthesis and interpretation, and whether recommendations should only be developed after the formal consultation phase.

Overall, results from the survey and multi-stakeholder consultation provided rich insight into the views and perspectives of scoping terminology, definition and methodological steps providing further insight into why a lack of consensus may exist. The diversity of fields increasingly adopting this methodology may offer some explanation to the challenges seen to date in adopting a universal term and definition. Nevertheless, for this methodology to maintain the rigor which it aspires to achieve and sustain, it is critical we consider adopting clear and consistent language that may be transferrable across disciplines.

Overall, meeting participants viewed scoping studies as systematic, rigorous and transparent, while allowing for flexibility of process. The following features emerged as distinct characteristics for each of the methodological steps: 1) research question and scoping purpose (exploratory, mapping, breadth); 2) search strategy and study selection (iterative, inclusive of grey literature and diverse study designs), 3) charting collating and summarizing (involves no quality assessment of included studies, may be iterative, synthesis could range from descriptive (counting characteristics of studies) to analytical (syntheses of qualitative and quantitative data involving thematic or content analysis) and 4) consultation phase conducted after the literature review (emerging from the field of qualitative research that involves consultation with knowledge users and community members to address the research question; an essential form of knowledge transfer and exchange).

While ongoing consultation may occur in other types of studies or reviews (providing expertise, context and interpretation), the consultation phase in scoping studies was viewed as a formalized and distinct phase involving key informants and/or stakeholders with expertise in the field of inquiry. The consultation phase in scoping studies, if undertaken, requires formal recruitment, data collection, qualitative approaches to analysis and interpretation, and ethics board review. Consultation goes beyond integrated or end-of-study knowledge translation and exchange and involves acquiring new information, enabling investigators to formally present findings from the literature synthesis, obtaining further experiential evidence and perspectives related to the scope of inquiry, and offering interpretations and considerations for the broader field. These characteristics provide a foundation from which to support our above proposed scoping study definition and will help to inform the development of future reporting guidelines.

Key considerations in scoping study methodology

To our knowledge this is the first study to explore experiences and opinions on scoping study methodology from the perspectives of researchers, clinicians, community members, representatives from community-based organizations, and policy stakeholders with expertise and/or interest in this methodology. This work directly builds on earlier work in an attempt to offer considerations related to terminology, definition and guidance on the methodological steps and rigor for the conduct and reporting of scoping studies [ 8 , 9 , 11 , 12 ].

We will now discuss key considerations for engaging in scoping study methodology that emerged from the survey and multi-stakeholder consultation with researchers, clinicians, knowledge users and policy stakeholders.

Ongoing debate of scoping terminology, definition, and purpose: Respondents expressed the need to develop clarity and consensus on terminology, definition, and purpose of conducting a scoping study. This will help to indicate when a scoping study is appropriate (and when it is not), and provide a foundation for developing detailed descriptions of each methodological step in conducting and reporting guidance for scoping studies. In the future we might consider whether clarity around the conceptual meaning of the terms ‘scoping study’ versus ‘scoping review’ may help to distinguish where this methodology lies on the spectrum of knowledge syntheses. Scoping studies also may be referred to either a map or syntheses, depending on whether they describe the characteristics versus synthesize the literature [ 27 ]. We did not specifically aim to determine how scoping study definitions and methodologies differ or align with other types of syntheses. This is an important focus of future work. Distinguishing ways in which scoping studies (or reviews) differ from other review methodologies for key dimensions including aims and approaches, structure and components; and breadth and depth, provides a strategy for clarifying the definition and purpose of this methodology [ 28 ].