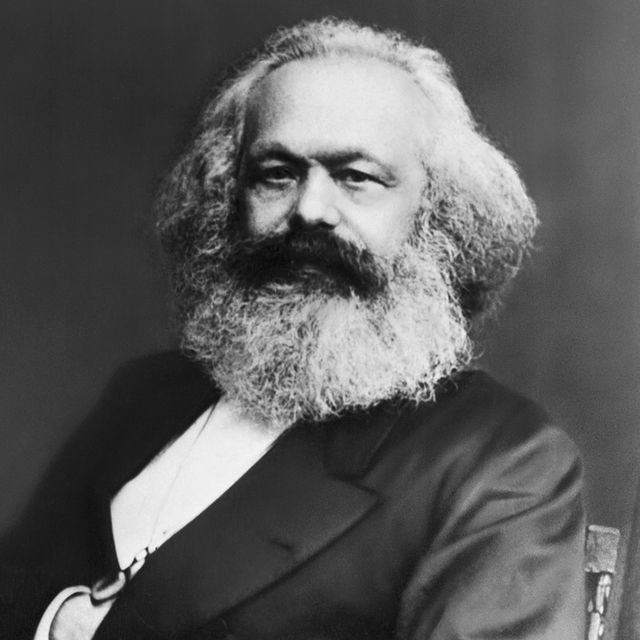

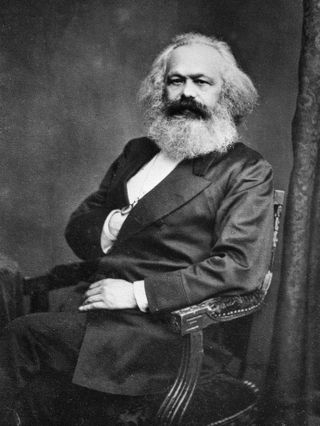

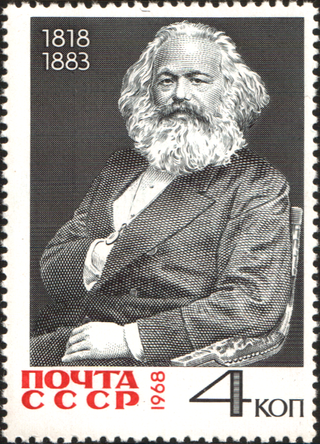

German philosopher and revolutionary socialist Karl Marx published 'The Communist Manifesto' and 'Das Kapital,' anticapitalist works that form the basis of Marxism.

(1818-1883)

Who Was Karl Marx?

Karl Marx began exploring sociopolitical theories at university among the Young Hegelians. He became a journalist, and his socialist writings would get him expelled from Germany and France. In 1848, he published The Communist Manifesto with Friedrich Engels and was exiled to London, where he wrote the first volume of Das Kapital and lived the remainder of his life.

Karl Heinrich Marx was one of nine children born to Heinrich and Henrietta Marx in Trier, Prussia. His father was a successful lawyer who revered Kant and Voltaire, and was a passionate activist for Prussian reform. Although both parents were Jewish with rabbinical ancestry, Karl’s father converted to Christianity in 1816 at the age of 35.

This was likely a professional concession in response to an 1815 law banning Jews from high society. He was baptized a Lutheran, rather than a Catholic, which was the predominant faith in Trier, because he “equated Protestantism with intellectual freedom.” When he was 6, Karl was baptized along with the other children, but his mother waited until 1825, after her father died.

Marx was an average student. He was educated at home until he was 12 and spent five years, from 1830 to 1835, at the Jesuit high school in Trier, at that time known as the Friedrich-Wilhelm Gymnasium. The school’s principal, a friend of Marx’s father, was a liberal and a Kantian and was respected by the people of Rhineland but suspect to authorities. The school was under surveillance and was raided in 1832.

In October of 1835, Marx began studying at the University of Bonn. It had a lively and rebellious culture, and Marx enthusiastically took part in student life. In his two semesters there, he was imprisoned for drunkenness and disturbing the peace, incurred debts and participated in a duel. At the end of the year, Marx’s father insisted he enroll in the more serious University of Berlin.

In Berlin, he studied law and philosophy and was introduced to the philosophy of G.W.F. Hegel, who had been a professor at Berlin until his death in 1831. Marx was not initially enamored with Hegel, but he soon became involved with the Young Hegelians, a radical group of students including Bruno Bauer and Ludwig Feuerbach, who criticized the political and religious establishments of the day.

In 1836, as he was becoming more politically zealous, Marx was secretly engaged to Jenny von Westphalen, a sought-after woman from a respected family in Trier who was four years his senior. This, along with his increasing radicalism, caused his father angst. In a series of letters, Marx’s father expressed concerns about what he saw as his son’s “demons,” and admonished him for not taking the responsibilities of marriage seriously enough, particularly when his wife-to-be came from a higher class.

Marx did not settle down. He received his doctorate from the University of Jena in 1841, but his radical politics prevented him from procuring a teaching position. He began to work as a journalist, and in 1842, he became the editor of Rheinische Zeitung , a liberal newspaper in Cologne. Just one year later, the government ordered the newspaper’s suppression, effective April 1, 1843. Marx resigned on March 18th. Three months later, in June, he finally married Jenny von Westphalen, and in October, they moved to Paris.

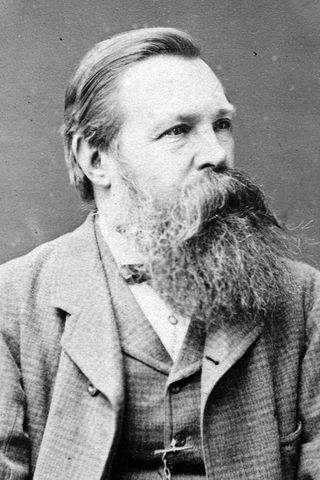

Paris was the political heart of Europe in 1843. There, along with Arnold Ruge, Marx founded a political journal titled Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals). Only a single issue was published before philosophical differences between Marx and Ruge resulted in its demise, but in August of 1844, the journal brought Marx together with a contributor, Friedrich Engels, who would become his collaborator and lifelong friend. Together, the two began writing a criticism of the philosophy of Bruno Bauer, a Young Hegelian and former friend of Marx’s. The result of Marx and Engels’s first collaboration was published in 1845 as The Holy Family .

Later that year, Marx moved to Belgium after being expelled from France while writing for another radical newspaper, Vorwärts! , which had strong ties to an organization that would later become the Communist League.

In Brussels, Marx was introduced to socialism by Moses Hess, and finally broke off from the philosophy of the Young Hegelians completely. While there, he wrote The German Ideology , in which he first developed his theory on historical materialism. Marx couldn’t find a willing publisher, however, and The German Ideology -- along with Theses on Feuerbach , which was also written during this time -- were not published until after his death.

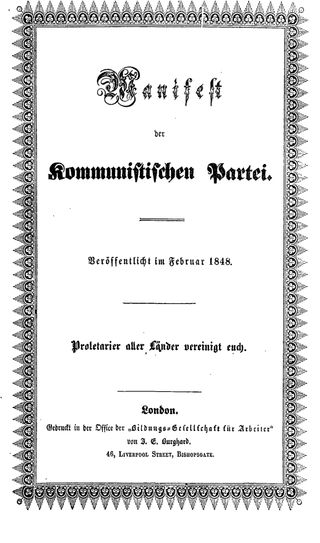

At the beginning of 1846, Marx founded a Communist Correspondence Committee in an attempt to link socialists from around Europe. Inspired by his ideas, socialists in England held a conference and formed the Communist League, and in 1847 at a Central Committee meeting in London, the organization asked Marx and Engels to write Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei (Manifesto of the Communist Party).

The Communist Manifesto, as this work is commonly known, was published in 1848, and shortly after, in 1849, Marx was expelled from Belgium. He went to France, anticipating a socialist revolution, but was deported from there as well. Prussia refused to renaturalize him, so Marx moved to London. Although Britain denied him citizenship, he remained in London until his death.

In London, Marx helped found the German Workers’ Educational Society, as well as a new headquarters for the Communist League. He continued to work as a journalist, including a 10-year stint as a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune from 1852 to 1862, but he never earned a living wage and was largely supported by Engels.

Marx became increasingly focused on capitalism and economic theory, and in 1867, he published the first volume of Das Kapital. The rest of his life was spent writing and revising manuscripts for additional volumes, which he did not complete. The remaining two volumes were assembled and published posthumously by Engels.

Marx died of pleurisy in London on March 14, 1883. While his original grave had only a nondescript stone, the Communist Party of Great Britain erected a large tombstone, including a bust of Marx, in 1954. The stone is etched with the last line of The Communist Manifesto (“Workers of all lands unite”), as well as a quote from the Theses on Feuerbach.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Karl Heinrich Marx

- Birth Year: 1818

- Birth date: May 5, 1818

- Birth City: Trier

- Birth Country: Germany

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: German philosopher and revolutionary socialist Karl Marx published 'The Communist Manifesto' and 'Das Kapital,' anticapitalist works that form the basis of Marxism.

- Business and Industry

- Education and Academia

- Astrological Sign: Taurus

- University of Berlin

- University of Bonn

- Nationalities

- Death Year: 1883

- Death date: March 14, 1883

- Death City: London

- Death Country: England

Philosophers

Marcus Garvey

Francis Bacon

Auguste Comte

Charles-Louis de Secondat

Saint Thomas Aquinas

William James

John Stuart Mill

A Brief Biography of Karl Marx

The Father of Communism influenced world events

- Major Sociologists

- Key Concepts

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

Karl Marx (May 5, 1818–March 14, 1883), a Prussian political economist, journalist, and activist, and author of the seminal works, "The Communist Manifesto" and "Das Kapital," influenced generations of political leaders and socioeconomic thinkers. Also known as the Father of Communism, Marx's ideas gave rise to furious, bloody revolutions, ushered in the toppling of centuries-old governments, and serve as the foundation for political systems that still rule over more than 20 percent of the world's population —or one in five people on the planet. "The Columbia History of the World" called Marx's writings "one of the most remarkable and original syntheses in the history of human intellect."

Personal Life and Education

Marx was born in Trier, Prussia (present-day Germany) on May 5, 1818, to Heinrich Marx and Henrietta Pressberg. Marx's parents were Jewish, and he came from a long line of rabbis on both sides of his family. However, his father converted to Lutheranism to evade antisemitism prior to Marx's birth.

Marx was educated at home by his father until high school, and in 1835 at the age of 17, enrolled at Bonn University in Germany, where he studied law at his father's request. Marx, however, was much more interested in philosophy and literature.

Following that first year at the university, Marx became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen, an educated baroness. They would later marry in 1843. In 1836, Marx enrolled at the University of Berlin, where he soon felt at home when he joined a circle of brilliant and extreme thinkers who were challenging existing institutions and ideas, including religion, philosophy, ethics, and politics. Marx graduated with his doctoral degree in 1841.

Career and Exile

After school, Marx turned to writing and journalism to support himself. In 1842 he became the editor of the liberal Cologne newspaper "Rheinische Zeitung," but the Berlin government banned it from publication the following year. Marx left Germany—never to return—and spent two years in Paris, where he first met his collaborator, Friedrich Engels.

However, chased out of France by those in power who opposed his ideas, Marx moved to Brussels, in 1845, where he founded the German Workers’ Party and was active in the Communist League. There, Marx networked with other leftist intellectuals and activists and—together with Engels—wrote his most famous work, " The Communist Manifesto ." Published in 1848, it contained the famous line: "Workers of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains." After being exiled from Belgium, Marx finally settled in London where he lived as a stateless exile for the rest of his life.

Marx worked in journalism and wrote for both German and English language publications. From 1852 to 1862, he was a correspondent for the "New York Daily Tribune," writing a total of 355 articles. He also continued writing and formulating his theories about the nature of society and how he believed it could be improved, as well as actively campaigning for socialism.

He spent the rest of his life working on a three-volume tome, "Das Kapital," which saw its first volume published in 1867. In this work, Marx aimed to explain the economic impact of capitalist society, where a small group, which he called the bourgeoisie, owned the means of production and used their power to exploit the proletariat, the working class that actually produced the goods that enriched the capitalist tsars. Engels edited and published the second and third volumes of "Das Kapital" shortly after Marx's death.

Death and Legacy

While Marx remained a relatively unknown figure in his own lifetime, his ideas and the ideology of Marxism began to exert a major influence on socialist movements shortly after his death. He succumbed to cancer on March 14, 1883, and was buried in Highgate Cemetery in London.

Marx's theories about society, economics, and politics, which are collectively known as Marxism, argue that all society progresses through the dialectic of class struggle. He was critical of the current socio-economic form of society, capitalism, which he called the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, believing it to be run by the wealthy middle and upper classes purely for their own benefit, and predicted that it would inevitably produce internal tensions which would lead to its self-destruction and replacement by a new system, socialism.

Under socialism, he argued that society would be governed by the working class in what he called the "dictatorship of the proletariat." He believed that socialism would eventually be replaced by a stateless, classless society called communism .

Continuing Influence

Whether Marx intended for the proletariat to rise up and foment revolution or whether he felt that the ideals of communism, ruled by an egalitarian proletariat, would simply outlast capitalism, is debated to this day. But, several successful revolutions did occur, propelled by groups that adopted communism—including those in Russia, 1917-1919 , and China, 1945-1948. Flags and banners depicting Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Russian Revolution, together with Marx, were long displayed in the Soviet Union . The same was true in China, where similar flags showing the leader of that country's revolution, Mao Zedong , together with Marx were also prominently displayed.

Marx has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history, and in a 1999 BBC poll was voted the "thinker of the millennium" by people from around the world. The memorial at his grave is always covered by tokens of appreciation from his fans. His tombstone is inscribed with words that echo those from "The Communist Manifesto," which seemingly predicted the influence Marx would have on world politics and economics: "Workers of all lands unite.”

- The Differences Between Socialism and Communism

- List of Current Communist Countries in the World

- Understanding Karl Marx's Class Consciousness and False Consciousness

- So What Is Culture, Exactly?

- Mode of Production in Marxism

- What Is Capitalism?

- Karl Marx's Greatest Hits

- Biography of Antonio Gramsci

- The Main Points of "The Communist Manifesto"

- These 4 Quotes Completely Changed the History of the World

- Understanding Conflict Theory

- All About Marxist Sociology

- Biography of Sociologist George Herbert Mead

- Vladimir Lenin Quotes

- History of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 7, 2019 | Original: November 9, 2009

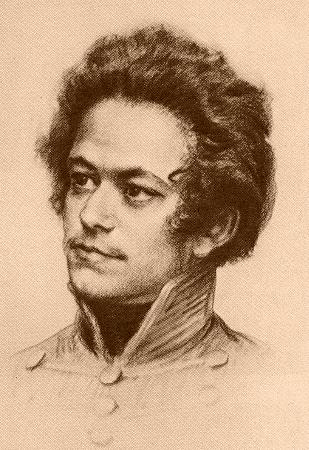

As a university student, Karl Marx (1818-1883) joined a movement known as the Young Hegelians, who strongly criticized the political and cultural establishments of the day. He became a journalist, and the radical nature of his writings would eventually get him expelled by the governments of Germany, France and Belgium. In 1848, Marx and fellow German thinker Friedrich Engels published “The Communist Manifesto,” which introduced their concept of socialism as a natural result of the conflicts inherent in the capitalist system. Marx later moved to London, where he would live for the rest of his life. In 1867, he published the first volume of “Capital” (Das Kapital), in which he laid out his vision of capitalism and its inevitable tendencies toward self-destruction, and took part in a growing international workers’ movement based on his revolutionary theories.

Karl Marx’s Early Life and Education

Karl Marx was born in 1818 in Trier, Prussia; he was the oldest surviving boy in a family of nine children. Both of his parents were Jewish, and descended from a long line of rabbis, but his father, a lawyer, converted to Lutheranism in 1816 due to contemporary laws barring Jews from higher society. Young Karl was baptized in the same church at the age of 6, but later became an atheist.

Did you know? The 1917 Russian Revolution, which overthrew three centuries of tsarist rule, had its roots in Marxist beliefs. The revolution’s leader, Vladimir Lenin, built his new proletarian government based on his interpretation of Marxist thought, turning Karl Marx into an internationally famous figure more than 30 years after his death.

After a year at the University of Bonn (during which Marx was imprisoned for drunkenness and fought a duel with another student), his worried parents enrolled their son at the University of Berlin, where he studied law and philosophy. There he was introduced to the philosophy of the late Berlin professor G.W.F. Hegel and joined a group known as the Young Hegelians, who were challenging existing institutions and ideas on all fronts, including religion, philosophy, ethics and politics.

Karl Marx Becomes a Revolutionary

After receiving his degree, Marx began writing for the liberal democratic newspaper Rheinische Zeitung, and he became the paper’s editor in 1842. The Prussian government banned the paper as too radical the following year. With his new wife, Jenny von Westphalen, Marx moved to Paris in 1843. There Marx met fellow German émigré Friedrich Engels, who would become his lifelong collaborator and friend. In 1845, Engels and Marx published a criticism of Bauer’s Young Hegelian philosophy entitled “The Holy Father.”

By that time, the Prussian government intervened to get Marx expelled from France, and he and Engels had moved to Brussels, Belgium, where Marx renounced his Prussian citizenship. In 1847, the newly founded Communist League in London, England, drafted Marx and Engels to write “The Communist Manifesto,” published the following year. In it, the two philosophers depicted all of history as a series of class struggles (historical materialism), and predicted that the upcoming proletarian revolution would sweep aside the capitalist system for good, making the workingmen the new ruling class of the world.

Karl Marx’s Life in London and “Das Kapital”

With revolutionary uprisings engulfing Europe in 1848, Marx left Belgium just before being expelled by that country’s government. He briefly returned to Paris and Germany before settling in London, where he would live for the rest of his life, despite being denied British citizenship. He worked as a journalist there, including 10 years as a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune, but never quite managed to earn a living wage, and was supported financially by Engels. In time, Marx became increasingly isolated from fellow London Communists, and focused more on developing his economic theories. In 1864, however, he helped found the International Workingmen’s Association (known as the First International) and wrote its inaugural address. Three years later, Marx published the first volume of “Capital” (Das Kapital) his masterwork of economic theory. In it he expressed a desire to reveal “the economic law of motion of modern society” and laid out his theory of capitalism as a dynamic system that contained the seeds of its own self-destruction and subsequent triumph of communism. Marx would spend the rest of his life working on manuscripts for additional volumes, but they remained unfinished at the time of his death, of pleurisy, on March 14, 1883.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

GREAT THINKERS Karl Marx

Karl Marx ranks among the most influential political philosophers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He spawned a far-reaching intellectual and cultural movement, known as Marxism; and a worldwide political organization under the name of communism, both of which followed Marx’s lead by propagating the doctrines of class struggle, historical materialism, and the inherent contradictions of industrial capital. For this reason his ideas are well known and his works are widely available, though his earlier writings, which are more philosophical and less dogmatic than the later economic works, have sometimes been suppressed by Communist publishers.

Marx was born in 1818 in Trier, in the Rhineland, then part of Prussia. Though he came from a long line of rabbis, Marx’s father was a lawyer with liberal views who left Judaism and became a Protestant for social reasons. Marx attended the University of Bonn briefly before becoming a student of law, theology, and philosophy at the University of Berlin. At Bonn he had been a member of the Poets’ Club, which counted many political radicals as members. In Berlin, he joined the Doctor Club, where he associated with the Young Hegelians, whose work he would later adapt for his teaching on historical materialism. During his college years Marx wrote some fiction and poetry; a number of his love poems, written to his girlfriend Jenny von Westphalen, are also available to us. Jenny and Karl met as children, courted as teenagers, married after their studies, had seven children, and lived together through old age.

Marx wrote his doctoral thesis on the difference between the materialism of Democritus and Epicurus. His thesis adviser was the heterodox Hegelian Bruno Bauer, and the thesis was controversial at the University of Berlin for its explicit atheism and overt attacks on theology. Marx was forced to submit it to the more liberal University of Jena, which gave him his PhD in 1841. In Berlin Marx became the editor of the short-lived Rheinische Zeitung , in which he regularly criticized not only the conservative Prussian government, but also socialists whom he thought did not understand either that a real practical struggle was required for revolution, or that incremental political reforms were insufficient and potentially counterproductive. Marx exhibited here his lifelong intellectual and political practice, called for by his theoretical conclusions with regard to the purpose of philosophy, of engaging in political disputes not necessarily to refute his opponents, but to denounce them; and to offer his own teaching, not as possibility or interpretation, but as a necessary fact obvious to anyone without ulterior motives.

After the closing of Rheinische Zeitung , Marx moved to Paris, where he continued his radical activity on behalf of socialism, began to study political economy, and further engaged with the Young Hegelian critique of religion. Indeed, his thought can be characterized very roughly as a synthesis of three themes: socialism, political economy, and the critique of religion. At this time Marx co-edited the one and only issue of German socialist Arnold Ruge’s radical publication, Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher , in which he published two of his most important works, Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right and On the Jewish Question . Here he began to apply the logic of Hegelian dialectic and adapt the critique of religion offered by the Young Hegelians to economic relations, providing the framework for the later, more detailed critique of political economy and for the“scientific socialism” of Das Kapital . In 1844 Marx published with Vorwärts! a utopian socialist German-language newspaper in France, and wrote his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts , in which he sought to justify his developing economic theories in Hegelian terms.

1844 was also when Marx met Frederich Engels, writer of The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 , with whom he will forever be associated. Together they wrote The Holy Family. In 1845 he wrote the brief “Theses on Feuerbach,” which claimed that if man is to be made whole, and not to live an alienated existence, he must change the material conditions that cause that alienation. The task of the philosopher, Marx here expresses most succinctly, is to enlighten the world by changing it.

Marx was expelled from France in 1845. He went to Brussels, where he began, with Engels, to write The German Ideology. While in Brussels Marx helped transform a group with whom he was associated, the League of the Just, into an overt political organization called the Communist League. The Communist Manifesto is a program of action for this League. He imagined the transformation from capitalism to socialism would happen quickly, and expended great energy over the next two years trying to bring it along. Expelled from Brussels, he moved first to Paris and then Cologne, where he started and ran the Neue Rheinische Zeitung . Marx then fled to London, where he lived for the rest of his life in relative poverty. He was employed, though, as a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune . Marx wrote often on the American slavery crisis, likening slaves to the industrial proletariat. In London Marx wrote the first volume of Das Kapital and made notes for the three additional volumes that were later published by Engels. In 1864 he became involved with the International Workingmen’s Association (now known as the First International), was elected to the General Council, and ultimately prevailed over those in the group, such as Mikhail Bakunin, who disagreed with his understanding of socialism. The First International disbanded in 1876, and when Marx died in 1883 there was no clearly recognized intellectual head of the worldwide socialist movement. Most socialist thinkers positioned themselves in relation to Marx’s thought, and as Marxism seemed to require a chief dogmatist and interpreter of events, competition for this position ensued.

For further biographical reading, see:

The Cambridge Companion to Marx , Ed. Terrell Carver, Cambridge: 1992.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Karl Marx summary

Know about the life and works of karl marx.

Karl Marx , (born May 5, 1818, Trier, Rhine province, Prussia [Ger.]—died March 14, 1883, London, Eng.), German political philosopher, economic theorist, and revolutionary. He studied humanities at the University of Bonn (1835) and law and philosophy at the University of Berlin (1836–41), where he was exposed to the works of G.W.F. Hegel . Working as a writer in Cologne and Paris (1842–45), he became active in leftist politics. In Paris he met Friedrich Engels , who would become his lifelong collaborator. Expelled from France in 1845, he moved to Brussels, where his political orientation matured and he and Engels made names for themselves through their writings. Marx was invited to join a secret left-wing group in London, for which he and Engels wrote the Communist Manifesto (1848). In that same year, Marx organized the first Rhineland Democratic Congress in Germany and opposed the king of Prussia when he dissolved the Prussian Assembly. Exiled, he moved to London in 1849, where he spent the rest of his life. He worked part-time as a European correspondent for the New York Tribune (1851–62) while writing his major critique of capitalism , Das Kapital (3 vol., 1867–94). He was a leading figure in the First International from 1864 until the defection of Mikhail Bakunin in 1872. See also Marxism ; communism ; dialectical materialism.

- Table of Contents

- New in this Archive

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Karl Marx (1818–1883) is best known not as a philosopher but as a revolutionary, whose works inspired the foundation of many communist regimes in the twentieth century. It is hard to think of many who have had as much influence in the creation of the modern world. Trained as a philosopher, Marx turned away from philosophy in his mid-twenties, towards economics and politics. However, in addition to his overtly philosophical early work, his later writings have many points of contact with contemporary philosophical debates, especially in the philosophy of history and the social sciences, and in moral and political philosophy. Historical materialism — Marx’s theory of history — is centered around the idea that forms of society rise and fall as they further and then impede the development of human productive power. Marx sees the historical process as proceeding through a necessary series of modes of production, characterized by class struggle, culminating in communism. Marx’s economic analysis of capitalism is based on his version of the labour theory of value, and includes the analysis of capitalist profit as the extraction of surplus value from the exploited proletariat. The analysis of history and economics come together in Marx’s prediction of the inevitable economic breakdown of capitalism, to be replaced by communism. However Marx refused to speculate in detail about the nature of communism, arguing that it would arise through historical processes, and was not the realisation of a pre-determined moral ideal.

1. Marx’s Life and Works

- 2.1. On The Jewish Question

- 2.2. Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: Introduction

- 2.3. 1844 Manuscripts

- 2.4. Theses on Feuerbach

3. Economics

4.1 the german ideology, 4.2 1859 preface, 4.3 functional explanation, 4.4 rationality, 4.5 alternative interpretations, 5. morality, other internet resources, related entries.

Karl Marx was born in Trier, in the German Rhineland, in 1818. Although his family was Jewish they converted to Christianity so that his father could pursue his career as a lawyer in the face of Prussia’s anti-Jewish laws. A precocious schoolchild, Marx studied law in Bonn and Berlin, and then wrote a PhD thesis in Philosophy, comparing the views of Democritus and Epicurus. On completion of his doctorate in 1841 Marx hoped for an academic job, but he had already fallen in with too radical a group of thinkers and there was no real prospect. Turning to journalism, Marx rapidly became involved in political and social issues, and soon found himself having to consider communist theory. Of his many early writings, four, in particular, stand out. ‘Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Introduction’, and ‘On The Jewish Question’, were both written in 1843 and published in the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher. The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts , written in Paris 1844, and the ‘Theses on Feuerbach’ of 1845, remained unpublished in Marx’s lifetime.

The German Ideology , co-written with Engels in 1845, was also unpublished but this is where we see Marx beginning to develop his theory of history. The Communist Manifesto is perhaps Marx’s most widely read work, even if it is not the best guide to his thought. This was again jointly written with Engels and published with a great sense of excitement as Marx returned to Germany from exile to take part in the revolution of 1848. With the failure of the revolution Marx moved to London where he remained for the rest of his life. He now concentrated on the study of economics, producing, in 1859, his Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy . This is largely remembered for its Preface, in which Marx sketches out what he calls ‘the guiding principles’ of his thought, on which many interpretations of historical materialism are based. Marx’s main economic work is, of course, Capital (Volume 1), published in 1867, although Volume 3, edited by Engels, and published posthumously in 1894, contains much of interest. Finally, the late pamphlet Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875) is an important source for Marx’s reflections on the nature and organisation of communist society.

The works so far mentioned amount only to a small fragment of Marx’s opus, which will eventually run to around 100 large volumes when his collected works are completed. However the items selected above form the most important core from the point of view of Marx’s connection with philosophy, although other works, such as the 18 th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852), are often regarded as equally important in assessing Marx’s analysis of concrete political events. In what follows, I shall concentrate on those texts and issues that have been given the greatest attention within the Anglo-American philosophical literature.

2. The Early Writings

The intellectual climate within which the young Marx worked was dominated by the influence of Hegel, and the reaction to Hegel by a group known as the Young Hegelians, who rejected what they regarded as the conservative implications of Hegel’s work. The most significant of these thinkers was Ludwig Feuerbach, who attempted to transform Hegel’s metaphysics, and, thereby, provided a critique of Hegel’s doctrine of religion and the state. A large portion of the philosophical content of Marx’s works written in the early 1840s is a record of his struggle to define his own position in reaction to that of Hegel and Feuerbach and those of the other Young Hegelians.

2.1 ‘On The Jewish Question’

In this text Marx begins to make clear the distance between himself and his radical liberal colleagues among the Young Hegelians; in particular Bruno Bauer. Bauer had recently written against Jewish emancipation, from an atheist perspective, arguing that the religion of both Jews and Christians was a barrier to emancipation. In responding to Bauer, Marx makes one of the most enduring arguments from his early writings, by means of introducing a distinction between political emancipation — essentially the grant of liberal rights and liberties — and human emancipation. Marx’s reply to Bauer is that political emancipation is perfectly compatible with the continued existence of religion, as the contemporary example of the United States demonstrates. However, pushing matters deeper, in an argument reinvented by innumerable critics of liberalism, Marx argues that not only is political emancipation insufficient to bring about human emancipation, it is in some sense also a barrier. Liberal rights and ideas of justice are premised on the idea that each of us needs protection from other human beings who are a threat to our liberty and security. Therefore liberal rights are rights of separation, designed to protect us from such perceived threats. Freedom on such a view, is freedom from interference. What this view overlooks is the possibility — for Marx, the fact — that real freedom is to be found positively in our relations with other people. It is to be found in human community, not in isolation. Accordingly, insisting on a regime of rights encourages us to view each other in ways that undermine the possibility of the real freedom we may find in human emancipation. Now we should be clear that Marx does not oppose political emancipation, for he sees that liberalism is a great improvement on the systems of feud and religious prejudice and discrimination which existed in the Germany of his day. Nevertheless, such politically emancipated liberalism must be transcended on the route to genuine human emancipation. Unfortunately, Marx never tells us what human emancipation is, although it is clear that it is closely related to the idea of non-alienated labour, which we will explore below.

2.2 ‘Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Introduction’

This work is home to Marx’s notorious remark that religion is the ‘opiate of the people’, a harmful, illusion-generating painkiller, and it is here that Marx sets out his account of religion in most detail. Just as importantly Marx here also considers the question of how revolution might be achieved in Germany, and sets out the role of the proletariat in bringing about the emancipation of society as a whole.

With regard to religion, Marx fully accepted Feuerbach’s claim in opposition to traditional theology that human beings had invented God in their own image; indeed a view that long pre-dated Feuerbach. Feuerbach’s distinctive contribution was to argue that worshipping God diverted human beings from enjoying their own human powers. While accepting much of Feuerbach’s account Marx’s criticizes Feuerbach on the grounds that he has failed to understand why people fall into religious alienation and so is unable to explain how it can be transcended. Feuerbach’s view appears to be that belief in religion is purely an intellectual error and can be corrected by persuasion. Marx’s explanation is that religion is a response to alienation in material life, and therefore cannot be removed until human material life is emancipated, at which point religion will wither away. Precisely what it is about material life that creates religion is not set out with complete clarity. However, it seems that at least two aspects of alienation are responsible. One is alienated labour, which will be explored shortly. A second is the need for human beings to assert their communal essence. Whether or not we explicitly recognize it, human beings exist as a community, and what makes human life possible is our mutual dependence on the vast network of social and economic relations which engulf us all, even though this is rarely acknowledged in our day-to-day life. Marx’s view appears to be that we must, somehow or other, acknowledge our communal existence in our institutions. At first it is ‘deviously acknowledged’ by religion, which creates a false idea of a community in which we are all equal in the eyes of God. After the post-Reformation fragmentation of religion, where religion is no longer able to play the role even of a fake community of equals, the state fills this need by offering us the illusion of a community of citizens, all equal in the eyes of the law. Interestingly, the political liberal state, which is needed to manage the politics of religious diversity, takes on the role offered by religion in earlier times of providing a form of illusory community. But the state and religion will both be transcended when a genuine community of social and economic equals is created.

Of course we are owed an answer to the question how such a society could be created. It is interesting to read Marx here in the light of his third Thesis on Feuerbach where he criticises an alternative theory. The crude materialism of Robert Owen and others assumes that human beings are fully determined by their material circumstances, and therefore to bring about an emancipated society it is necessary and sufficient to make the right changes to those material circumstances. However, how are those circumstances to be changed? By an enlightened philanthropist like Owen who can miraculously break through the chain of determination which ties down everyone else? Marx’s response, in both the Theses and the Critique, is that the proletariat can break free only by their own self-transforming action. Indeed if they do not create the revolution for themselves — in alliance, of course, with the philosopher — they will not be fit to receive it.

2.3 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts

The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts cover a wide range of topics, including much interesting material on private property and communism, and on money, as well as developing Marx’s critique of Hegel. However, the manuscripts are best known for their account of alienated labour. Here Marx famously depicts the worker under capitalism as suffering from four types of alienated labour. First, from the product, which as soon as it is created is taken away from its producer. Second, in productive activity (work) which is experienced as a torment. Third, from species-being, for humans produce blindly and not in accordance with their truly human powers. Finally, from other human beings, where the relation of exchange replaces the satisfaction of mutual need. That these categories overlap in some respects is not a surprise given Marx’s remarkable methodological ambition in these writings. Essentially he attempts to apply a Hegelian deduction of categories to economics, trying to demonstrate that all the categories of bourgeois economics — wages, rent, exchange, profit, etc. — are ultimately derived from an analysis of the concept of alienation. Consequently each category of alienated labour is supposed to be deducible from the previous one. However, Marx gets no further than deducing categories of alienated labour from each other. Quite possibly in the course of writing he came to understand that a different methodology is required for approaching economic issues. Nevertheless we are left with a very rich text on the nature of alienated labour. The idea of non-alienation has to be inferred from the negative, with the assistance of one short passage at the end of the text ‘On James Mill’ in which non-alienated labour is briefly described in terms which emphasise both the immediate producer’s enjoyment of production as a confirmation of his or her powers, and also the idea that production is to meet the needs of others, thus confirming for both parties our human essence as mutual dependence. Both sides of our species essence are revealed here: our individual human powers and our membership in the human community.

It is important to understand that for Marx alienation is not merely a matter of subjective feeling, or confusion. The bridge between Marx’s early analysis of alienation and his later social theory is the idea that the alienated individual is ‘a plaything of alien forces’, albeit alien forces which are themselves a product of human action. In our daily lives we take decisions that have unintended consequences, which then combine to create large-scale social forces which may have an utterly unpredicted, and highly damaging, effect. In Marx’s view the institutions of capitalism — themselves the consequences of human behaviour — come back to structure our future behaviour, determining the possibilities of our action. For example, for as long as a capitalist intends to stay in business he must exploit his workers to the legal limit. Whether or not wracked by guilt the capitalist must act as a ruthless exploiter. Similarly the worker must take the best job on offer; there is simply no other sane option. But by doing this we reinforce the very structures that oppress us. The urge to transcend this condition, and to take collective control of our destiny — whatever that would mean in practice — is one of the motivating and sustaining elements of Marx’s social analysis.

2.4 ‘Theses on Feuerbach’

The Theses on Feuerbach contain one of Marx’s most memorable remarks: “the philosophers have only interpreted the world, the point is to change it” (thesis 11). However the eleven theses as a whole provide, in the compass of a couple of pages, a remarkable digest of Marx’s reaction to the philosophy of his day. Several of these have been touched on already (for example, the discussions of religion in theses 4, 6 and 7, and revolution in thesis 3) so here I will concentrate only on the first, most overtly philosophical, thesis.

In the first thesis Marx states his objections to ‘all hitherto existing’ materialism and idealism. Materialism is complimented for understanding the physical reality of the world, but is criticised for ignoring the active role of the human subject in creating the world we perceive. Idealism, at least as developed by Hegel, understands the active nature of the human subject, but confines it to thought or contemplation: the world is created through the categories we impose upon it. Marx combines the insights of both traditions to propose a view in which human beings do indeed create — or at least transform — the world they find themselves in, but this transformation happens not in thought but through actual material activity; not through the imposition of sublime concepts but through the sweat of their brow, with picks and shovels. This historical version of materialism, which transcends and thus rejects all existing philosophical thought, is the foundation of Marx’s later theory of history. As Marx puts it in the 1844 Manuscripts, ‘Industry is the real historical relationship of nature … to man’. This thought, derived from reflection on the history of philosophy, together with his experience of social and economic realities, as a journalist, sets the agenda for all Marx’s future work.

Capital Volume 1 begins with an analysis of the idea of commodity production. A commodity is defined as a useful external object, produced for exchange on a market. Thus two necessary conditions for commodity production are the existence of a market, in which exchange can take place, and a social division of labour, in which different people produce different products, without which there would be no motivation for exchange. Marx suggests that commodities have both use-value — a use, in other words — and an exchange-value — initially to be understood as their price. Use value can easily be understood, so Marx says, but he insists that exchange value is a puzzling phenomenon, and relative exchange values need to be explained. Why does a quantity of one commodity exchange for a given quantity of another commodity? His explanation is in terms of the labour input required to produce the commodity, or rather, the socially necessary labour, which is labour exerted at the average level of intensity and productivity for that branch of activity within the economy. Thus the labour theory of value asserts that the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of socially necessary labour time required to produce it. Marx provides a two stage argument for the labour theory of value. The first stage is to argue that if two objects can be compared in the sense of being put on either side of an equals sign, then there must be a ‘third thing of identical magnitude in both of them’ to which they are both reducible. As commodities can be exchanged against each other, there must, Marx argues, be a third thing that they have in common. This then motivates the second stage, which is a search for the appropriate ‘third thing’, which is labour in Marx’s view, as the only plausible common element. Both steps of the argument are, of course, highly contestable.

Capitalism is distinctive, Marx argues, in that it involves not merely the exchange of commodities, but the advancement of capital, in the form of money, with the purpose of generating profit through the purchase of commodities and their transformation into other commodities which can command a higher price, and thus yield a profit. Marx claims that no previous theorist has been able adequately to explain how capitalism as a whole can make a profit. Marx’s own solution relies on the idea of exploitation of the worker. In setting up conditions of production the capitalist purchases the worker’s labour power — his ability to labour — for the day. The cost of this commodity is determined in the same way as the cost of every other; i.e. in terms of the amount of socially necessary labour power required to produce it. In this case the value of a day’s labour power is the value of the commodities necessary to keep the worker alive for a day. Suppose that such commodities take four hours to produce. Thus the first four hours of the working day is spent on producing value equivalent to the value of the wages the worker will be paid. This is known as necessary labour. Any work the worker does above this is known as surplus labour, producing surplus value for the capitalist. Surplus value, according to Marx, is the source of all profit. In Marx’s analysis labour power is the only commodity which can produce more value than it is worth, and for this reason it is known as variable capital. Other commodities simply pass their value on to the finished commodities, but do not create any extra value. They are known as constant capital. Profit, then, is the result of the labour performed by the worker beyond that necessary to create the value of his or her wages. This is the surplus value theory of profit.

It appears to follow from this analysis that as industry becomes more mechanised, using more constant capital and less variable capital, the rate of profit ought to fall. For as a proportion less capital will be advanced on labour, and only labour can create value. In Capital Volume 3 Marx does indeed make the prediction that the rate of profit will fall over time, and this is one of the factors which leads to the downfall of capitalism. (However, as pointed out by Marx’s able expositor Paul Sweezy in The Theory of Capitalist Development , the analysis is problematic.) A further consequence of this analysis is a difficulty for the theory that Marx did recognise, and tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to meet also in Capital Volume 3. It follows from the analysis so far that labour intensive industries ought to have a higher rate of profit than those which use less labour. Not only is this empirically false, it is theoretically unacceptable. Accordingly, Marx argued that in real economic life prices vary in a systematic way from values. Providing the mathematics to explain this is known as the transformation problem, and Marx’s own attempt suffers from technical difficulties. Although there are known techniques for solving this problem now (albeit with unwelcome side consequences), we should recall that the labour theory of value was initially motivated as an intuitively plausible theory of price. But when the connection between price and value is rendered as indirect as it is in the final theory, the intuitive motivation of the theory drains away. A further objection is that Marx’s assertion that only labour can create surplus value is unsupported by any argument or analysis, and can be argued to be merely an artifact of the nature of his presentation. Any commodity can be picked to play a similar role. Consequently with equal justification one could set out a corn theory of value, arguing that corn has the unique power of creating more value than it costs. Formally this would be identical to the labour theory of value. Nevertheless, the claims that somehow labour is responsible for the creation of value, and that profit is the consequence of exploitation, remain intuitively powerful, even if they are difficult to establish in detail.

However, even if the labour theory of value is considered discredited, there are elements of his theory that remain of worth. The Cambridge economist Joan Robinson, in An Essay on Marxian Economics , picked out two aspects of particular note. First, Marx’s refusal to accept that capitalism involves a harmony of interests between worker and capitalist, replacing this with a class based analysis of the worker’s struggle for better wages and conditions of work, versus the capitalist’s drive for ever greater profits. Second, Marx’s denial that there is any long-run tendency to equilibrium in the market, and his descriptions of mechanisms which underlie the trade-cycle of boom and bust. Both provide a salutary corrective to aspects of orthodox economic theory.

4. Theory of History

Marx did not set out his theory of history in great detail. Accordingly, it has to be constructed from a variety of texts, both those where he attempts to apply a theoretical analysis to past and future historical events, and those of a more purely theoretical nature. Of the latter, the 1859 Preface to A Critique of Political Economy has achieved canonical status. However, The German Ideology , co-written with Engels in 1845, is a vital early source in which Marx first sets out the basics of the outlook of historical materialism. We shall briefly outline both texts, and then look at the reconstruction of Marx’s theory of history in the hands of his philosophically most influential recent exponent, G.A. Cohen, who builds on the interpretation of the early Russian Marxist Plekhanov.

We should, however, be aware that Cohen’s interpretation is not universally accepted. Cohen provided his reconstruction of Marx partly because he was frustrated with existing Hegelian-inspired ‘dialectical’ interpretations of Marx, and what he considered to be the vagueness of the influential works of Louis Althusser, neither of which, he felt, provided a rigorous account of Marx’s views. However, some scholars believe that the interpretation that we shall focus on is faulty precisely for its lack of attention to the dialectic. One aspect of this criticism is that Cohen’s understanding has a surprisingly small role for the concept of class struggle, which is often felt to be central to Marx’s theory of history. Cohen’s explanation for this is that the 1859 Preface, on which his interpretation is based, does not give a prominent role to class struggle, and indeed it is not explicitly mentioned. Yet this reasoning is problematic for it is possible that Marx did not want to write in a manner that would engage the concerns of the police censor, and, indeed, a reader aware of the context may be able to detect an implicit reference to class struggle through the inclusion of such phrases as “then begins an era of social revolution,” and “the ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out”. Hence it does not follow that Marx himself thought that the concept of class struggle was relatively unimportant. Furthermore, when A Critique of Political Economy was replaced by Capital , Marx made no attempt to keep the 1859 Preface in print, and its content is reproduced just as a very much abridged footnote in Capital . Nevertheless we shall concentrate here on Cohen’s interpretation as no other account has been set out with comparable rigour, precision and detail.

In The German Ideology Marx and Engels contrast their new materialist method with the idealism that had characterised previous German thought. Accordingly, they take pains to set out the ‘premises of the materialist method’. They start, they say, from ‘real human beings’, emphasising that human beings are essentially productive, in that they must produce their means of subsistence in order to satisfy their material needs. The satisfaction of needs engenders new needs of both a material and social kind, and forms of society arise corresponding to the state of development of human productive forces. Material life determines, or at least ‘conditions’ social life, and so the primary direction of social explanation is from material production to social forms, and thence to forms of consciousness. As the material means of production develop, ‘modes of co-operation’ or economic structures rise and fall, and eventually communism will become a real possibility once the plight of the workers and their awareness of an alternative motivates them sufficiently to become revolutionaries.

In the sketch of The German Ideology , all the key elements of historical materialism are present, even if the terminology is not yet that of Marx’s more mature writings. Marx’s statement in 1859 Preface renders much the same view in sharper form. Cohen’s reconstruction of Marx’s view in the Preface begins from what Cohen calls the Development Thesis, which is pre-supposed, rather than explicitly stated in the Preface. This is the thesis that the productive forces tend to develop, in the sense of becoming more powerful, over time. This states not that they always do develop, but that there is a tendency for them to do so. The productive forces are the means of production, together with productively applicable knowledge: technology, in other words. The next thesis is the primacy thesis, which has two aspects. The first states that the nature of the economic structure is explained by the level of development of the productive forces, and the second that the nature of the superstructure — the political and legal institutions of society— is explained by the nature of the economic structure. The nature of a society’s ideology, which is to say the religious, artistic, moral and philosophical beliefs contained within society, is also explained in terms of its economic structure, although this receives less emphasis in Cohen’s interpretation. Indeed many activities may well combine aspects of both the superstructure and ideology: a religion is constituted by both institutions and a set of beliefs.

Revolution and epoch change is understood as the consequence of an economic structure no longer being able to continue to develop the forces of production. At this point the development of the productive forces is said to be fettered, and, according to the theory once an economic structure fetters development it will be revolutionised — ‘burst asunder’ — and eventually replaced with an economic structure better suited to preside over the continued development of the forces of production.

In outline, then, the theory has a pleasing simplicity and power. It seems plausible that human productive power develops over time, and plausible too that economic structures exist for as long as they develop the productive forces, but will be replaced when they are no longer capable of doing this. Yet severe problems emerge when we attempt to put more flesh on these bones.

Prior to Cohen’s work, historical materialism had not been regarded as a coherent view within English-language political philosophy. The antipathy is well summed up with the closing words of H.B. Acton’s The Illusion of the Epoch : “Marxism is a philosophical farrago”. One difficulty taken particularly seriously by Cohen is an alleged inconsistency between the explanatory primacy of the forces of production, and certain claims made elsewhere by Marx which appear to give the economic structure primacy in explaining the development of the productive forces. For example, in The Communist Manifesto Marx states that: ‘The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production.’ This appears to give causal and explanatory primacy to the economic structure — capitalism — which brings about the development of the forces of production. Cohen accepts that, on the surface at least, this generates a contradiction. Both the economic structure and the development of the productive forces seem to have explanatory priority over each other.

Unsatisfied by such vague resolutions as ‘determination in the last instance’, or the idea of ‘dialectical’ connections, Cohen self-consciously attempts to apply the standards of clarity and rigour of analytic philosophy to provide a reconstructed version of historical materialism.

The key theoretical innovation is to appeal to the notion of functional explanation (also sometimes called ‘consequence explanation’). The essential move is cheerfully to admit that the economic structure does indeed develop the productive forces, but to add that this, according to the theory, is precisely why we have capitalism (when we do). That is, if capitalism failed to develop the productive forces it would disappear. And, indeed, this fits beautifully with historical materialism. For Marx asserts that when an economic structure fails to develop the productive forces — when it ‘fetters’ the productive forces — it will be revolutionised and the epoch will change. So the idea of ‘fettering’ becomes the counterpart to the theory of functional explanation. Essentially fettering is what happens when the economic structure becomes dysfunctional.

Now it is apparent that this renders historical materialism consistent. Yet there is a question as to whether it is at too high a price. For we must ask whether functional explanation is a coherent methodological device. The problem is that we can ask what it is that makes it the case that an economic structure will only persist for as long as it develops the productive forces. Jon Elster has pressed this criticism against Cohen very hard. If we were to argue that there is an agent guiding history who has the purpose that the productive forces should be developed as much as possible then it would make sense that such an agent would intervene in history to carry out this purpose by selecting the economic structures which do the best job. However, it is clear that Marx makes no such metaphysical assumptions. Elster is very critical — sometimes of Marx, sometimes of Cohen — of the idea of appealing to ‘purposes’ in history without those being the purposes of anyone.

Cohen is well aware of this difficulty, but defends the use of functional explanation by comparing its use in historical materialism with its use in evolutionary biology. In contemporary biology it is commonplace to explain the existence of the stripes of a tiger, or the hollow bones of a bird, by pointing to the function of these features. Here we have apparent purposes which are not the purposes of anyone. The obvious counter, however, is that in evolutionary biology we can provide a causal story to underpin these functional explanations; a story involving chance variation and survival of the fittest. Therefore these functional explanations are sustained by a complex causal feedback loop in which dysfunctional elements tend to be filtered out in competition with better functioning elements. Cohen calls such background accounts ‘elaborations’ and he concedes that functional explanations are in need of elaborations. But he points out that standard causal explanations are equally in need of elaborations. We might, for example, be satisfied with the explanation that the vase broke because it was dropped on the floor, but a great deal of further information is needed to explain why this explanation works. Consequently, Cohen claims that we can be justified in offering a functional explanation even when we are in ignorance of its elaboration. Indeed, even in biology detailed causal elaborations of functional explanations have been available only relatively recently. Prior to Darwin, or arguably Lamark, the only candidate causal elaboration was to appeal to God’s purposes. Darwin outlined a very plausible mechanism, but having no genetic theory was not able to elaborate it into a detailed account. Our knowledge remains incomplete to this day. Nevertheless, it seems perfectly reasonable to say that birds have hollow bones in order to facilitate flight. Cohen’s point is that the weight of evidence that organisms are adapted to their environment would permit even a pre-Darwinian atheist to assert this functional explanation with justification. Hence one can be justified in offering a functional explanation even in absence of a candidate elaboration: if there is sufficient weight of inductive evidence.

At this point the issue, then, divides into a theoretical question and an empirical one. The empirical question is whether or not there is evidence that forms of society exist only for as long as they advance productive power, and are replaced by revolution when they fail. Here, one must admit, the empirical record is patchy at best, and there appear to have been long periods of stagnation, even regression, when dysfunctional economic structures were not revolutionised.

The theoretical issue is whether a plausible elaborating explanation is available to underpin Marxist functional explanations. Here there is something of a dilemma. In the first instance it is tempting to try to mimic the elaboration given in the Darwinian story, and appeal to chance variations and survival of the fittest. In this case ‘fittest’ would mean ‘most able to preside over the development of the productive forces’. Chance variation would be a matter of people trying out new types of economic relations. On this account new economic structures begin through experiment, but thrive and persist through their success in developing the productive forces. However the problem is that such an account would seem to introduce a larger element of contingency than Marx seeks, for it is essential to Marx’s thought that one should be able to predict the eventual arrival of communism. Within Darwinian theory there is no warrant for long-term predictions, for everything depends on the contingencies of particular situations. A similar heavy element of contingency would be inherited by a form of historical materialism developed by analogy with evolutionary biology. The dilemma, then, is that the best model for developing the theory makes predictions based on the theory unsound, yet the whole point of the theory is predictive. Hence one must either look for an alternative means of producing elaborating explanation, or give up the predictive ambitions of the theory.

The driving force of history, in Cohen’s reconstruction of Marx, is the development of the productive forces, the most important of which is technology. But what is it that drives such development? Ultimately, in Cohen’s account, it is human rationality. Human beings have the ingenuity to apply themselves to develop means to address the scarcity they find. This on the face of it seems very reasonable. Yet there are difficulties. As Cohen himself acknowledges, societies do not always do what would be rational for an individual to do. Co-ordination problems may stand in our way, and there may be structural barriers. Furthermore, it is relatively rare for those who introduce new technologies to be motivated by the need to address scarcity. Rather, under capitalism, the profit motive is the key. Of course it might be argued that this is the social form that the material need to address scarcity takes under capitalism. But still one may raise the question whether the need to address scarcity always has the influence that it appears to have taken on in modern times. For example, a ruling class’s absolute determination to hold on to power may have led to economically stagnant societies. Alternatively, it might be thought that a society may put religion or the protection of traditional ways of life ahead of economic needs. This goes to the heart of Marx’s theory that man is an essentially productive being and that the locus of interaction with the world is industry. As Cohen himself later argued in essays such as ‘Reconsidering Historical Materialism’, the emphasis on production may appear one-sided, and ignore other powerful elements in human nature. Such a criticism chimes with a criticism from the previous section; that the historical record may not, in fact, display the tendency to growth in the productive forces assumed by the theory.

Many defenders of Marx will argue that the problems stated are problems for Cohen’s interpretation of Marx, rather than for Marx himself. It is possible to argue, for example, that Marx did not have a general theory of history, but rather was a social scientist observing and encouraging the transformation of capitalism into communism as a singular event. And it is certainly true that when Marx analyses a particular historical episode, as he does in the 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon , any idea of fitting events into a fixed pattern of history seems very far from Marx’s mind. On other views Marx did have a general theory of history but it is far more flexible and less determinate than Cohen insists (Miller). And finally, as noted, there are critics who believe that Cohen’s interpretation is entirely wrong-headed (Sayers).

The issue of Marx and morality poses a conundrum. On reading Marx’s works at all periods of his life, there appears to be the strongest possible distaste towards bourgeois capitalist society, and an undoubted endorsement of future communist society. Yet the terms of this antipathy and endorsement are far from clear. Despite expectations, Marx never says that capitalism is unjust. Neither does he say that communism would be a just form of society. In fact he takes pains to distance himself from those who engage in a discourse of justice, and makes a conscious attempt to exclude direct moral commentary in his own works. The puzzle is why this should be, given the weight of indirect moral commentary one finds.

There are, initially, separate questions, concerning Marx’s attitude to capitalism and to communism. There are also separate questions concerning his attitude to ideas of justice, and to ideas of morality more broadly concerned. This, then, generates four questions: (1) Did Marx think capitalism unjust?; (2) did he think that capitalism could be morally criticised on other grounds?; (3) did he think that communism would be just? (4) did he think it could be morally approved of on other grounds? These are the questions we shall consider in this section.

The initial argument that Marx must have thought that capitalism is unjust is based on the observation that Marx argued that all capitalist profit is ultimately derived from the exploitation of the worker. Capitalism’s dirty secret is that it is not a realm of harmony and mutual benefit but a system in which one class systematically extracts profit from another. How could this fail to be unjust? Yet it is notable that Marx never concludes this, and in Capital he goes as far as to say that such exchange is ‘by no means an injustice’.

Allen Wood has argued that Marx took this approach because his general theoretical approach excludes any trans-epochal standpoint from which one can comment on the justice of an economic system. Even though one can criticize particular behaviour from within an economic structure as unjust (and theft under capitalism would be an example) it is not possible to criticise capitalism as a whole. This is a consequence of Marx’s analysis of the role of ideas of justice from within historical materialism. That is to say, juridical institutions are part of the superstructure, and ideas of justice are ideological, and the role of both the superstructure and ideology, in the functionalist reading of historical materialism adopted here, is to stabilise the economic structure. Consequently, to state that something is just under capitalism is simply a judgement applied to those elements of the system that will tend to have the effect of advancing capitalism. According to Marx, in any society the ruling ideas are those of the ruling class; the core of the theory of ideology.

Ziyad Husami, however, argues that Wood is mistaken, ignoring the fact that for Marx ideas undergo a double determination in that the ideas of the non-ruling class may be very different from those of the ruling class. Of course it is the ideas of the ruling class that receive attention and implementation, but this does not mean that other ideas do not exist. Husami goes as far as to argue that members of the proletariat under capitalism have an account of justice which matches communism. From this privileged standpoint of the proletariat, which is also Marx’s standpoint, capitalism is unjust, and so it follows that Marx thought capitalism unjust.

Plausible though it may sound, Husami’s argument fails to account for two related points. First, it cannot explain why Marx never described capitalism as unjust, and second, it does not account for the distance Marx wanted to place between his own scientific socialism, and that of the utopian socialists who argued for the injustice of capitalism. Hence one cannot avoid the conclusion that the ‘official’ view of Marx is that capitalism is not unjust.

Nevertheless, this leaves us with a puzzle. Much of Marx’s description of capitalism — his use of the words ‘embezzlement’, ‘robbery’ and ‘exploitation’ — belie the official account. Arguably, the only satisfactory way of understanding this issue is, once more, from G.A. Cohen, who proposes that Marx believed that capitalism was unjust, but did not believe that he believed it was unjust (Cohen 1983). In other words, Marx, like so many of us, did not have perfect knowledge of his own mind. In his explicit reflections on the justice of capitalism he was able to maintain his official view. But in less guarded moments his real view slips out, even if never in explicit language. Such an interpretation is bound to be controversial, but it makes good sense of the texts.

Whatever one concludes on the question of whether Marx thought capitalism unjust, it is, nevertheless, obvious that Marx thought that capitalism was not the best way for human beings to live. Points made in his early writings remain present throughout his writings, if no longer connected to an explicit theory of alienation. The worker finds work a torment, suffers poverty, overwork and lack of fulfillment and freedom. People do not relate to each other as humans should.

Does this amount to a moral criticism of capitalism or not? In the absence of any special reason to argue otherwise, it simply seems obvious that Marx’s critique is a moral one. Capitalism impedes human flourishing.

Marx, though, once more refrained from making this explicit; he seemed to show no interest in locating his criticism of capitalism in any of the traditions of moral philosophy, or explaining how he was generating a new tradition. There may have been two reasons for his caution. The first was that while there were bad things about capitalism, there is, from a world historical point of view, much good about it too. For without capitalism, communism would not be possible. Capitalism is to be transcended, not abolished, and this may be difficult to convey in the terms of moral philosophy.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, we need to return to the contrast between scientific and utopian socialism. The utopians appealed to universal ideas of truth and justice to defend their proposed schemes, and their theory of transition was based on the idea that appealing to moral sensibilities would be the best, perhaps only, way of bringing about the new chosen society. Marx wanted to distance himself from this tradition of utopian thought, and the key point of distinction was to argue that the route to understanding the possibilities of human emancipation lay in the analysis of historical and social forces, not in morality. Hence, for Marx, any appeal to morality was theoretically a backward step.

This leads us now to Marx’s assessment of communism. Would communism be a just society? In considering Marx’s attitude to communism and justice there are really only two viable possibilities: either he thought that communism would be a just society or he thought that the concept of justice would not apply: that communism would transcend justice.

Communism is described by Marx, in the Critique of the Gotha Programme , as a society in which each person should contribute according to their ability and receive according to their need. This certainly sounds like a theory of justice, and could be adopted as such. However it is possibly truer to Marx’s thought to say that this is part of an account in which communism transcends justice, as Lukes has argued.

If we start with the idea that the point of ideas of justice is to resolve disputes, then a society without disputes would have no need or place for justice. We can see this by reflecting upon Hume’s idea of the circumstances of justice. Hume argued that if there was enormous material abundance — if everyone could have whatever they wanted without invading another’s share — we would never have devised rules of justice. And, of course, Marx often suggested that communism would be a society of such abundance. But Hume also suggested that justice would not be needed in other circumstances; if there were complete fellow-feeling between all human beings. Again there would be no conflict and no need for justice. Of course, one can argue whether either material abundance or human fellow-feeling to this degree would be possible, but the point is that both arguments give a clear sense in which communism transcends justice.

Nevertheless we remain with the question of whether Marx thought that communism could be commended on other moral grounds. On a broad understanding, in which morality, or perhaps better to say ethics, is concerning with the idea of living well, it seems that communism can be assessed favourably in this light. One compelling argument is that Marx’s career simply makes no sense unless we can attribute such a belief to him. But beyond this we can be brief in that the considerations adduced in section 2 above apply again. Communism clearly advances human flourishing, in Marx’s view. The only reason for denying that, in Marx’s vision, it would amount to a good society is a theoretical antipathy to the word ‘good’. And here the main point is that, in Marx’s view, communism would not be brought about by high-minded benefactors of humanity. Quite possibly his determination to retain this point of difference between himself and the Utopian socialists led him to disparage the importance of morality to a degree that goes beyond the call of theoretical necessity.

Primary Literature

- Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels, Gesamtausgabe (MEGA), Berlin, 1975–.

- –––, Collected Works , New York and London: International Publishers. 1975.

- –––, Selected Works , 2 Volumes, Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1962.

- Marx, Karl, Karl Marx: Selected Writings , 2 nd edition, David McLellan (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Secondary Literature

See McLellan 1973 and Wheen 1999 for biographies of Marx, and see Singer 2000 and Wolff 2002 for general introductions.

- Acton, H.B., 1955, The Illusion of the Epoch , London: Cohen and West.

- Althusser, Louis, 1969, For Marx , London: Penguin.

- Althusser, Louis, and Balibar, Etienne, 1970, Reading Capital , London: NLB.

- Arthur, C.J., 1986, Dialectics of Labour , Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Avineri, Shlomo, 1970, The Social and Political Thought of Karl Marx , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bottomore, Tom (ed.), 1979, Karl Marx , Oxford: Blackwell.

- Brudney, Daniel, 1998, Marx’s Attempt to Leave Philosophy . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Carver, Terrell, 1982, Marx’s Social Theory , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carver, Terrell (ed.), 1991, The Cambridge Companion to Marx , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carver, Terrell, 1998, The Post-Modern Marx , Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Cohen, Joshua, 1982, ‘Review of G.A. Cohen, Karl Marx’s Theory of History ’, Journal of Philosophy , 79: 253–273.

- Cohen, G.A., 1983, ‘Review of Allen Wood, Karl Marx ’, Mind , 92: 440–445.