- Short Contribution

- Open access

- Published: 01 March 2018

Enhancing SARA: a new approach in an increasingly complex world

- Steve Burton 1 &

- Mandy McGregor 2

Crime Science volume 7 , Article number: 4 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

38k Accesses

2 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

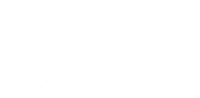

The research note describes how an enhancement to the SARA (Scan, Analyse, Respond and Assess) problem-solving methodology has been developed by Transport for London for use in dealing with crime and antisocial behaviour, road danger reduction and reliability problems on the transport system in the Capital. The revised methodology highlights the importance of prioritisation, effective allocation of intervention resources and more systematic learning from evaluation.

Introduction

Problem oriented policing (POP), commonly referred to as problem-solving in the UK, was first described by Goldstein ( 1979 , 1990 ) and operationalised by Eck and Spelman ( 1987 ) using the SARA model. SARA is the acronym for Scanning, Analysis, Response and Assessment. It is essentially a rational method to systematically identify and analyse problems, develop specific responses to individual problems and subsequently assess whether the response has been successful (Weisburd et al. 2008 ).

A number of police agencies around the world use this approach, although its implementation has been patchy, has often not been sustained and is particularly vulnerable to changes in the commitment of senior staff and lack of organisational support (Scott and Kirby 2012 ). This short contribution outlines the way in which SARA has been used and further developed by Transport for London (TfL, the strategic transport authority for London) and its policing partners—the Metropolitan Police Service, British Transport Police and City of London Police. Led by TfL, they have been using POP techniques to deal with crime and disorder issues on the network, with some success. TfL’s problem-solving projects have been shortlisted on three occasions for the Goldstein Award, an international award that recognises excellence in POP initiatives, winning twice in 2006 and 2011 (see Goldstein Award Winners 1993–2010 ).

Crime levels on the transport system are derived from a regular and consistent data extract from the Metropolitan Police Service and British Transport Police crime recording systems. In 2006, crime levels on the bus network were causing concern. This was largely driven by a sudden rise in youth crime with a 72 per cent increase from 2005 to 2006: The level rose from around 290 crimes involving one or more suspects aged under 16 years per month in 2005 to around 500 crimes per month in 2006.

Fear of crime was also an issue and there were increasing public and political demands for action. In response TfL, with its policing partners, worked to embed a more structured and systematic approach to problem-solving, allowing them to better identify, manage and evaluate their activities. Since then crime has more than halved on the network (almost 30,000 fewer crimes each year) despite significant increases in passenger journeys (Fig. 1 ). This made a significant contribution to the reduction in crime from 20 crimes per million passenger journeys in 2005/6 to 7.5 in 2016/17.

Crime volumes and rates on major TfL transport networks and passenger levels

Although crime has being falling generally over the last decade, the reduction on London’s public transport network has been comparatively greater than that seen overall in London and in England and Wales (indexed figures can be seen in Fig. 2 ). The reductions on public transport are even more impressive given that there are very few transport-related burglary and vehicle crimes which have been primary drivers of the overall reductions seen in London and England and Wales. TfL attributes this success largely to its problem-solving approach and the implementation of a problem-solving framework and supporting processes.

UK, London and transport crime trends since 2005/6

A need for change

TfL remains fully committed to problem-solving and processes are embedded within its transport policing, enforcement and compliance activities. However, it has become apparent that its approach needs to develop further in response to a number of emerging issues:

broadening of SARA beyond a predominant crime focus to address road danger reduction and road reliability problems;

increasing strategic complexity in the community safety and policing arena for example, the increased focus on safeguarding and vulnerability;

the increasing pace of both social and technological change, for example, sexual crimes such as ‘upskirting’ and ‘airdropping of indecent images’ (see http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/london-tube-sexual-assault-underground-transportation-harassment-a8080756.html );

financial challenges and resource constraints yet growing demands for policing and enforcement action to deal with issues;

greater focus on a range of non-enforcement interventions as part of problem solving responses;

a small upturn in some crime types including passenger aggression and low-level violence when the network is at peak capacity;

increasing focus on evidence-led policing and enforcement, and;

some evidence of cultural fatigue among practitioners with processes which indicated a refresh of the approach might be timely.

Implications

In response, TfL undertook a review of how SARA and its problem-solving activities are being delivered and considered academic reviews and alternative models such as the 5I’s as developed by Ekblom ( 2002 ) and those assessed by Sidebottom and Tilley ( 2011 ). This review resulted in a decision to continue with a SARA-style approach because of its alignment with existing processes and the practitioner base that had already been established around SARA. This has led to a refresh of TfL’s strategic approach to managing problem-solving which builds on SARA and aims to highlight the importance of prioritisation, effective allocation of intervention resources and capturing the learning from problem-solving activities at a strategic and tactical level. Whilst these stages are implicit within the SARA approach, it was felt that a more explicit recognition of their importance as component parts of the process would enhance overall problem-solving efforts undertaken by TfL and its policing partners. The revised approach, which recognises these important additional steps in the problem-solving process, has been given the acronym SPATIAL—Scan, Prioritise, Analyse, Task, Intervene, Assess and Learn as defined in Table 1 below:

SPATIAL adapts the SARA approach to address a number of emerging common issues affecting policing and enforcement agencies over recent years. The financial challenges now facing many organisations mean that limited budgets and constrained resources are inadequate to be able to solve all problems identified. The additional steps in the SPATIAL process help to ensure that there is (a) proper consideration and prioritisation of identified ‘problems’ (b) effective identification and allocation of resources to deal with the problem, considering the impact on other priorities and (c) capture of learning from the assessment of problem-solving efforts so that evidence of what works (including an assessment of process, cost, implementation and impact) can be incorporated in the development of problem-solving action and response plans where appropriate. The relationship between SARA and SPATIAL is shown in Fig. 3 below:

SARA and SPATIAL

In overall terms SPATIAL helps to ensure that TfL and policing partners’ problem-solving activities are developed, coordinated and managed in a more structured way. Within TfL problem-solving is implemented at three broad levels—Strategic, Tactical and Operational. Where problems and activities sit within these broad levels depends on the timescale, geographic spread, level of harm and profile. These can change over time. Operational activities continue to be driven by a problem-solving process based primarily on SARA as they do not demand the same level of resource prioritisation and scale of evaluation, with a SPATIAL approach applied at a strategic level. In reality a number of tactical/operational problem-oriented policing activities will form a subsidiary part of strategic problem-solving plans. Table 2 provides examples of problems at these three levels.

The processes supporting delivery utilise existing well established practices used by TfL and its partners. These include Transtat (the joint TfL/MPS version of the ‘CompStat’ performance management process for transport policing), a strategic tasking meeting (where the ‘P’ in SPATIAL is particularly explored) and an Operations Hub which provides deployment oversight and command and control services for TfL’s on-street resources. Of course, in reality these processes are not always sequential. In many cases there will be feedback loops to allow refocusing of the problem definition and re-assessment of problem-solving plans and interventions.

For strategic and tactical level problems, the SPATIAL framework provides senior officers with greater oversight of problem-solving activity at all stages of the problem-solving process. It helps to ensure that TfL and transport policing resources are focussed on the right priorities, that the resource allocation is appropriate across identified priorities and that there is oversight of the problem-solving approaches being adopted, progress against plans and delivery of agreed outcomes.

Although these changes are in the early stages of implementation, it is already clear that they provide the much needed focus around areas such as strategic prioritisation and allocation of TfL, police and other partner resources (including officers and other interventions such as marketing, communications and environmental changes). The new approach also helps to ensure that any lessons learned from the assessment are captured and used to inform evidence-based interventions for similar problems through the use of a bespoke evaluation framework (adaptation of the Maryland scientific methods scale, see Sherman et al. 1998 ) and the implementation of an intranet based library. The adapted approach also resonates with practitioners because it builds on the well-established SARA process but brings additional focus to prioritising issues and optimising resources. More work is required to assess the medium and longer term implications and benefits derived from the new process and this will be undertaken as it becomes more mature.

Eck, J., & Spelman, W. (1987). Problem - solving: problem - oriented policing in newport news . Washington, D.C.: Police Executive Research Forum. https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=111964 .

Ekblom, P. (2002). From the source to the mainstream is uphill: The challenge of transferring knowledge of crime prevention through replication, innovation 5 design against crime paper the 5Is framework and anticipation. In N. Tilley (Ed.), Analysis for crime prevention, crime prevention studies (Vol. 13, pp. 131–203).

Goldstein, H. (1979). Improving Policing: A Problem-Oriented Approach. Univ. of Wisconsin Legal Studies Research Paper No. 1336. pp. 236–258. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2537955 . Accessed 21 Jan 2018.

Goldstein, H. (1990). Problem-oriented policing create space independent publishing platform. ISBN-10: 1514809486.

Goldstein Award Winners (1993–2010), Center for Problem-Oriented Policing. http://www.popcenter.org/library/awards/goldstein/ . Accessed 21 Jan 2018.

Scott, M. S., & Kirby, S. (2012). Implementing POP: leading, structuring and managing a problem-oriented police agency . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Google Scholar

Sidebottom, A., & Tilley, N. (2011). Improving problem-oriented policing: the need for a new model. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 13 (2), 79–101.

Article Google Scholar

Sherman, L., Gottfredson, D., MacKenzie D., Eck, J., Reuter, P. & Bushway, S. (1988). Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising. National Institute of Justice Research Brief. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/171676.pdf . Accessed 14 Dec 2017.

Weisburd, D., Telep, C.W., Hinkle, J. C., & Eck, J. E. (2008). The effects of problem oriented policing on crime and disorder. https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/media/k2/attachments/1045_R.pdf . Accessed 21 Jan 2018.

Download references

Authors’ contributions

The article was co-authored by the two named authors. SB developed the original concept and developed the methodology and MM helped refine the ideas for practical implementation and provided additional content to the document. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Ethical approval and consent to participate, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

60 Fordwich Rise, London, SG14 2BN, UK

Steve Burton

Transport for London, London, UK

Mandy McGregor

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Steve Burton .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Burton, S., McGregor, M. Enhancing SARA: a new approach in an increasingly complex world. Crime Sci 7 , 4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-018-0078-4

Download citation

Received : 18 September 2017

Accepted : 19 February 2018

Published : 01 March 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-018-0078-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Problem solving

- Transport policing

- Problem oriented policing

Crime Science

ISSN: 2193-7680

- General enquiries: [email protected]

The SARA Model builds on Herman Goldstein’s Problem-Oriented Policing and was developed and coined by John Eck and William Spelman (1987) in Problem solving: Problem-oriented policing in Newport News . Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum.

The SARA model is a decision-making model that incorporates analysis and research, tailoring solutions to specific problems, and most importantly, evaluating the effectiveness of those responses. The acronym SARA stands for:

Scanning: Identifying, prioritizing and selecting problems that need addressing using both data from police and other sources as well as community and citizen input.

Analysis: Deeply analyzing the causes of the problem, including the underlying causes of repeated calls for service and crime incidents.

Response: Determining and implementing a response to a particular problem. Ideas for responses should be “evidence-based” when possible (see, for example, the Matrix ) or at least tailored to the specific problem at hand using general principles of good crime prevention.

Assessment: Often the most ignored part of the SARA model, this requires assessing and evaluating the impact of a particular response and being willing to try something different if the response was not effective.

For more information see this Matrix resource as well as the POP Center .

Problem-Solving and SARA

- First Online: 28 April 2022

Cite this chapter

- Iain Agar 4

730 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Criminologist Herman Goldstein articulated the problem-oriented approach to policing (hereafter, POP) in 1979, recognising that many of the isolated incidents responded to by police are symptomatic of more substantive problems rooted within a disparate array of social and environmental conditions. The basic elements of problem-solving, and indeed problem-solving analysis, begin with grouping incidents as problems and putting them at the heart of policing – the problem becoming a unit of police work (Goldstein H, Problem oriented policing. Temple Univ. Pr, Philadelphia, 1990). The aim of problem-solving is to improve policing by enabling the most efficient use of our finite resources to serve the public effectively. In this chapter, we will work through the organisational theory of POP from the analyst perspective, broken down into two parts – the active role of the analyst in problem-solving and identifying suitable responses, followed by an extended breakdown of the stages in a SARA model and how you can become a problem-solving crime analyst.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Problem-oriented policing: matching the science to the art

Dissecting a Criminal Investigation

Policing a negotiated world: a partial test of klinger’s ecological theory of policing.

https://popcenter.asu.edu/pop-guides

What Works Crime Reduction Toolkit https://whatworks.college.police.uk/toolkit/Pages/Welcome.aspx

Evidence-Based Policing Matrix https://cebcp.org/evidence-based-policing/the-matrix/

Crime Science Journal https://crimesciencejournal.biomedcentral.com/

Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing https://www.springer.com/journal/41887

Allison, P., & Allison, P. D. (2001). Missing data . University of Pennsylvania.

Google Scholar

Ariel, B., Bland, M., & Sutherland, A. (2021). Experimental designs . Sage.

Ashby, M. P. J. (2020). Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Science, 9 (1). Available at: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/ep87s/ . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Bachman, R., & Schutt, R. K. (2020). Fundamentals of research in criminology and criminal justice: Fifth Edition . Sage Publications, Inc.

Birks, D., Coleman, A., & Jackson, D. (2020). Unsupervised identification of crime problems from police free-text data. Crime Science, 9 (1). Available at: https://crimesciencejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40163-020-00127-4 . Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Boba, R. (2003). Problem analysis in policing . Police Foundation. Available at: https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/library/reading/pdfs/problemanalysisinpolicing.pdf . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Boba Santos, R. (2017). Crime analysis with crime mapping . Sage Publications, Inc.

Borrion, H., Ekblom, P., Alrajeh, D., Borrion, A. L., Keane, A., Koch, D., Mitchener-Nissen, T., & Toubaline, S. (2020). The problem with crime problem-solving: Towards a second generation pop? The British Journal of Criminology, 60 (1).

Bowers, K., Tompson, L., Sidebottom, A., Bullock, K., & Johnson, S. D. (2017). Reviewing evidence for evidence-based policing. In J. Knutsson & L. Tompson (Eds.), Advances in evidence-based policing . Routledge.

Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1995). Criminality of place. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 3 (3), 5–26.

Article Google Scholar

Brayley, H., Cockbain, E., & Laycock, G. (2011). The value of crime scripting: Deconstructing internal child sex trafficking. Policing, 5 (2), 132–143. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/policing/article/5/2/132/1518450 . Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Brown, R., Scott, M. S., & Remington, F. J. (2007). Implementing responses to problems . United States of America 07. Available at: https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/implementing_responses_to_problems.pdf . Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Burton, S., & McGregor, M. (2018). Enhancing SARA: A new approach in an increasingly complex world. Crime Science, 7 (1).

Chainey, S. (2012). Improving the explanatory content of analysis products using hypothesis testing. Policing, 6 (2), 108–121.

Clarke, R. V., & Eck, J. (2003). Becoming a problem-solving crime analyst in 55 small steps . Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science, University College London. Available at: https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/library/reading/PDFs/55stepsUK.pdf . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Clarke, R. V. G., & Schultze, P. A. (2005). Researching a problem . U.S. Dept. Of Justice, Office Of Community Oriented Policing Services. Available at: https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/researching_a_problem.pdf . Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review , [online] 44 (4), 588–608.

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (1986). The reasoning criminal: Rational choice perspectives on offending . Transaction Publishers.

Book Google Scholar

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (2016). The rational choice perspective. In R. Wortley & M. Townsley (Eds.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Eck, J. E., & Spelman, W. (1987). Problem-solving: Problem-oriented policing in Newport News . U.S. Dept. Of Justice, National Institute Of Justice. Available at: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/111964NCJRS.pdf . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Eck, J. E. (2017). Assessing responses to problems: an introductory guide for police problem-solvers: 2nd Edition . U.S. Dept. Of Justice, Office Of Community Oriented Policing Services. Available at: https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/assessing_responses_to_problems_final.pdf . Accessed 07 Mar 2021.

Eck, J.E. (2019). Advocate: Why Problem-Oriented Policing. In: D. Weisburd and A.A. Braga, eds., Police Innovation: Contrasting Perspectives. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Ekblom, P. (2005). The 5Is framework: Sharing good practice in crime prevention. In E. Marks, A. Meyer, & R. Linssen (Eds.), Quality in crime prevention . Hannover.

Ekblom, P., & Pease, K. (1995). Evaluating crime prevention. In M. Tonry & D. Farrington (Eds.), From building a safer society: Strategic approaches to crime prevention (Vol. 19, pp 585–662). United States.

Goldstein, H. (1990). Problem oriented policing . Temple Univ. Pr.

Goldstein, H. (2003). Problem analysis in policing . Police Foundation.

Guilfoyle, S. (2013). Intelligent policing: how systems thinking methods eclipse conventional management practice . Triarchy Press.

Heeks, M., Reed, S., Tafsiri, M., & Prince, S. (2018). Economic and social costs of crime . Home Office. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/732110/the-economic-and-social-costs-of-crime-horr99.pdf Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Heuer, R. J. (1999). Psychology of intelligence analysis. Washington, D.C.: Center For The Study Of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency.

Hinkle, J. C., Weisburd, D., Telep, C. W., & Petersen, K. (2020). Problem-oriented policing for reducing crime and disorder: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 16 (2).

Johnson, S. D., Tilley, N., & Bowers, K. J. (2015). Introducing EMMIE: An evidence rating scale to encourage mixed-method crime prevention synthesis reviews. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 11 (3), 459–473.

Kennedy, D. M. (2020). Problem-oriented public safety. In M. S. Scott & R. V. Clarke (Eds.), Problem-oriented policing successful case studies . Routledge.

Kime, S., & Wheller, L. (2018). The policing evaluation toolkit . College of Policing. Available at: https://whatworks.college.police.uk/Support/Documents/The_Policing_Evaluation_Toolkit.pdf . Accessed 7 Mar 2021.

Kuang, D., Brantingham, P. J., & Bertozzi, A. L. (2017). Crime topic modeling. Crime Science, 6 (1). Available at: https://crimesciencejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40163-017-0074-0 . Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Ratcliffe, J. (2008). Intelligence-led policing . Willan Publishing.

Ratcliffe, J. H. (2014). Towards an index for harm-focused policing. Policing, 9 (2), 164–182. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/policing/article/9/2/164/1451352 . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Ratcliffe, J. (2016). Intelligence-led policing (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ratcliffe, J. (2018). Reducing crime: A companion for police leaders . Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Scott, M., & Kirby, S. (2012). Implementing POP: Leading, structuring and managing a Problem-Oriented Police Agency . Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC. Available at: https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/60830/1/popmanualfinal_copy.pdf . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Sherman, L. W. (1997). Preventing crime: what works, what doesn’t, what’s promising: A report to the United States Congress . College Park, Md Univ. Of Maryland. Available at: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/171676.pdf . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Sherman, L.W. (2020). How to count crime: The Cambridge harm index consensus. Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing .

Sidebottom, A., & Tilley, N. (2011). Improving problem-oriented policing: The need for a new model? Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 13 (2), 79–101.

Sidebottom, A., Tilley, N., & Eck, J. E. (2012). Towards checklists to reduce common sources of problem-solving failure. Policing, 6 (2), 194–209.

Sidebottom, A., Bullock, K., Ashby, M., Kirby, S., Armitage, R., Laycock, G., & Tilley, N. (2020). Successful police problem-solving: A practice guide . Jill Dando Institute of Security and Crime Science, University College London. Available at: https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/successful_police_problem_solving_a_guide.pdf . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Skogan, W. G. (1977). Dimensions of the dark figure of unreported crime. Crime & Delinquency, 23 (1), 41–50.

Telep, C. W., & Weisburd, D. (2012). What is known about the effectiveness of police practices in reducing crime and disorder? Police Quarterly, 15 (4), 331–357.

Tilley, N., Read, T. and Great Britain. Home Office. Research, Development And Statistics Directorate. Policing And Reducing Crime Unit. (2000). Not rocket science?: problem-solving and crime reduction: Paper 6 . Home Office, Policing And Reducing Crime Unit. Available at: https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/library/reading/pdfs/Rocket_Science.pdf . Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Tilley, N. (2008). Crime Prevention . Willan Pub..

Townsley, M., Mann, M., & Garrett, K. (2011). The missing link of crime analysis: A systematic approach to testing competing hypotheses. Policing, 5 (2), 158–171. Available at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/91925/ . Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Walker, J. T., & Drawve, G. R. (2018). Foundations of crime analysis: Data, analyses, and mapping . Routledge.

Weisburd, D., Telep, C. W., Hinkle, J. C., & Eck, J. E. (2010). Is problem-oriented policing effective in reducing crime and disorder? Criminology & Public Policy, 9 (1), 139–172.

Weisburd, D., Hinkle, J. C., & Telep, C. (2019). Updated protocol: The effects of problem-oriented policing on crime and disorder: An updated systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 15 (1–2). Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cl2.1089 . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Wheeler, A. P. (2016). Tables and graphs for monitoring temporal crime trends. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 18 (3), 159–172.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Essex Police, Chelmsford, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Iain Agar .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

Matthew Bland

Barak Ariel

Norfolk and Suffolk Constabularies, Ipswich, UK

Natalie Ridgeon

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Agar, I. (2022). Problem-Solving and SARA. In: Bland, M., Ariel, B., Ridgeon, N. (eds) The Crime Analyst's Companion. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94364-6_14

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94364-6_14

Published : 28 April 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-94363-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-94364-6

eBook Packages : Law and Criminology Law and Criminology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- What is Problem-Oriented Policing?

- History of Problem-Oriented Policing

- Key Elements of POP

The SARA Model

- The Problem Analysis Triangle

- Situational Crime Prevention

- 25 Techniques

- Links to Other POP Friendly Sites

- About POP en Español

A commonly used problem-solving method is the SARA model (Scanning, Analysis, Response and Assessment). The SARA model contains the following elements:

- Identifying recurring problems of concern to the public and the police.

- Identifying the consequences of the problem for the community and the police.

- Prioritizing those problems.

- Developing broad goals.

- Confirming that the problems exist.

- Determining how frequently the problem occurs and how long it has been taking place.

- Selecting problems for closer examination.

- Identifying and understanding the events and conditions that precede and accompany the problem.

- Identifying relevant data to be collected.

- Researching what is known about the problem type.

- Taking inventory of how the problem is currently addressed and the strengths and limitations of the current response.

- Narrowing the scope of the problem as specifically as possible.

- Identifying a variety of resources that may be of assistance in developing a deeper understanding of the problem.

- Developing a working hypothesis about why the problem is occurring.

- Brainstorming for new interventions.

- Searching for what other communities with similar problems have done.

- Choosing among the alternative interventions.

- Outlining a response plan and identifying responsible parties.

- Stating the specific objectives for the response plan.

- Carrying out the planned activities.

Assessment:

- Determining whether the plan was implemented (a process evaluation).

- Collecting pre and postresponse qualitative and quantitative data.

- Determining whether broad goals and specific objectives were attained.

- Identifying any new strategies needed to augment the original plan.

- Conducting ongoing assessment to ensure continued effectiveness.

N8 Policing Research Partnership

Implementing evidence-based policing: delivering change at the frontline.

by Helen Gordon-Smith | Mar 4, 2019 | 0 comments

We don’t call it training, this is an education. I want people who question what they are taught not just follow what they are taught.

For some years, GMP has engaged in research partnerships with universities. However, we started formally to use evidence-based policing in 2016 and created a research board and a network of EBP Champions. The reason for doing this was to improve informed decision making, so our people can make better choices based on evidence. An evidence-based practice HUB was established in 2018 and set about boosting the number of EBP Champions which now stands at 81. We also created an internal website for our people to see what is happening and access research. The EBP Hub is made up of a small team led by myself, and we support people who are conducting research, tests and problem oriented policing plans.

Our approach

The use of academic research to inform policing practice is not new but the approach we are taking is new, if not pioneering. We are creating leader/leader relationships rather than leader/follower relationships and equipping our people with the skills to take ownership of problems and think of innovative ways to reduce crime and keep people safe. The Hub model ensures we can coordinate this from the centre and have oversight of what is happening and where. This works well in connecting our EBP Champions to other people in our workforce and/or academics who have experience and an interest in a particular field. Equally, we are able to better shape our relationships with universities in respect of what policing topics and research questions will have real tangible impact for practitioners.

The process we are establishing in GMP is still very much in its early stages. In autumn 2018 we held a 5 day course focused on various evidence based research findings and criminological theories. The course also discussed how to break down a problem and look at it in terms of victims, offenders and locations and then how to approach that problem using evidence based policing methodologies. We don’t call it training, this is an education. I want people who question what they are taught not just follow what they are taught. This is about improving their skills as problem solvers in an evidence based way and ensuring they think differently about how they approach their work.

At our most recent workshop in January 2019, we saw some of those skills in practice. The day focused on issues in Greater Manchester through the lens of the OSARA model, a 5 stage process designed to facilitate a Problem-Orientated Policing approach (including: Objective, Scanning, Analysis, Response, Assessment). Each issue was presented and then opened up for discussion and feedback terms of the conclusions reached and action taken, how appropriate the success measures were and the wider knock-on effects of the intervention (such as has the issue been tackled or simply moved on). It raised some interesting debate amongst those present and offered a platform to show learning in practice and how methodologies can be applied to current, rather than hypothetical, situations.

They key driver for me in developing and implementing this process has always been to create a fully evidenced organisation where all of our people ask themselves ‘is this the best way of doing this, is their another way and how can we do things better?’ The workshop in February did just that. Ultimately, GMP is about community safety and we want people using research to make informed decisions to enhance community safety. This requires people to understand the importance of robust evaluation of policing operations and tactics, in order to learn from what worked and more importantly in order to learn from what didn’t. The EBP Champions are key to embedding this problem solving mind-set. We have great people here in GMP and I am privileged to be able to shape and equip a number of them with skills that enhance how they go about their work. My aim is to grow the cohort of EBP Champions and spread what we are doing to a wider audience in 2019.

Where we are going

As with all new concepts and ways of working there will undoubtedly be some resistance from those who feel it is not in the organisations best interest and, particularly in the case of policing, that we are expanding our remit to include the work of other agencies. A lot of policing demand is however not centred on what some people may call ‘traditional policing’, though some feel we should be dealing with just these issues. Contemporary policing has many challenges but the ethos is the same, we exist to protect society and help keep people safe. Some push back has come from when others think it is another agencies responsibility and we are fixing their problems for them. My views on this are that is if it is creating policing demand and we have an opportunity to reduce that demand then we should, and in most cases involve that partner in the process. The feedback is really good from people in the EBP Champions network, they feel really fulfilled that they are doing what they joined to do and making a real difference in improving people’s lives in the communities where they serve.

We are at the beginning of a journey in GMP. We have further evidence based policing workshops planned and I will be taking a number of colleagues from GMP to the SEBP conference in London in March 2019. We will also be hosting events at GMP that will be available for all of our people to attend. One will be with the N8 Policing Research Partnership to showcase the great work this partnership is delivering. It is important to the growth of what we are trying to achieve that people learn new things, sometimes things that have no direct relevance to their particular line of work. Equally, it is evidence based that learning new things is a major factor in enhancing people’s well-being!

Roger Pegram sits on the N8 Policing Research Partnership Steering Group as one of the GMP representatives. He is writing here in his personal capacity.

Recent Posts

- Report recommends shift in priorities, ten years on from Clare’s Law

- Procedural Justice: The vital role of trust and accountability for racially minoritised young women and girls

- N8 PRP Announces New 3 Year Phase, Seeks New Policing Co-Director

- What works in improving interagency responses to missing children investigations?

- N8 PRP Announces New Events and Registration Discount for Major Drugs Conference

- February 2024

- January 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- November 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- September 2021

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- September 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- August 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- The Open University

- Accessibility hub

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Start this free course now. Just create an account and sign in. Enrol and complete the course for a free statement of participation or digital badge if available.

4 Identifying potential solutions

4.1 decision making in policing.

In the following video, Police Officer Ben Hargreaves discusses the challenges around decision making for community safety.

While this is a powerful framework for problem solving (and has been adopted by police forces across the UK) it cannot be seen in isolation from the underlying social and psychological perspectives. Your own personal biases and preferences will have an impact on how you understand and interpret data and the way you relate to policies and ‘objective’ guidelines. Much of this will also be impacted by culture and the unspoken rules evident in organisations.

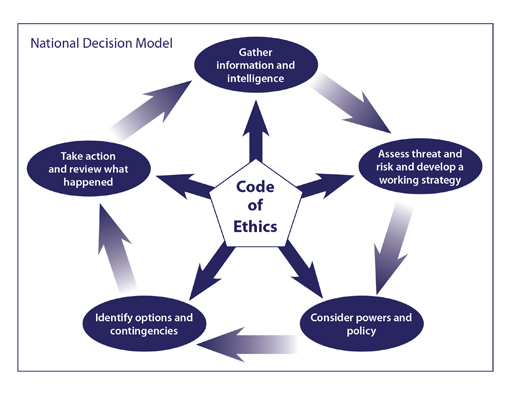

The National Decision Model

The NDM is a police framework designed to make the decision-making process easier and standardised. It should be used by all officers, decision makers and assessors who are involved in the whole decision process. Not only is it used for making decisions but to assess and judge those decisions. It can also be used to improve future decisions and help to create techniques and methods for many different situations.

The NDM is based around the police force mission statement and the Code of Ethics, which should be considered when completing each of the stages. You should ask yourself whether the action you are considering is consistent with the Code of Ethics, what the police service would expect, and what the community and the public as a whole would expect of you.

The NDM stages are:

Stage 1 Gather information about the problem in hand. Not only should you work out what you do know, but what you do not know. You will use the information gathered in stage 1 throughout the rest of the process and also when your decisions are being assessed and judged after the event.

Stage 2 Determine the threat, its nature and extent so that you can assess the situation and make the right decisions. Ask yourself, do you need to take the necessary action straight away or is this an ongoing problem? What is the most likely outcome and what would be the implications? Are the police the most appropriate people to deal with the problem, and are you best equipped to help resolve the problem at hand or would somebody else be better?

Stage 3 Knowing what the problem is, you will need to determine what powers you and the police have to combat the problem. Ask yourself which powers will be needed and if the required powers and policies need any additional or specialist assistance to be instigated and introduced. Is there any legislation that covers the process?

Stage 4 Armed with all of the information regarding the problem and any policies and other legislations that may exist, you are in a position to draw up a list of options. You should also use this opportunity to develop a contingency plan or a series of contingencies that can provide you with a backup plan if things do not go exactly to plan.

Stage 5 Once you have determined the most appropriate action, it is time to put this in place. Perform the most desirable action and, if necessary, begin the process again to get the best results possible. Review the process and determine whether or not you could have done things better and what you would do in the future if you were faced with a similar, or the same, problem.

Pentagon with text at the centre surrounded by five ovals with text. Block arrows pointing from central pentagon to each oval. Further block arrows pointing from each oval to the next in a clock-wise direction, indicating a cycle sequence.

Central pentagon text is ‘Code of Ethics’

Oval text as follows moving clockwise:

12 o’clock ‘Gather information and intelligence’

2 o’clock ‘Assess threat and risk and develop a working strategy’

5 ‘clock ‘Consider powers and policy’

7 o’clock ‘Identify options and contingencies’

10 o’clock ‘Take action and review what happened’

When it comes to policing, there are many standard decision making models to refer to such as OSARA and the National Decision Model. What they share is an attempt to put a common, objective framework on decision making efforts so that decisions can be objectively supported and justified, can be explained to colleagues and can be clearly analysed for lessons and understanding after the fact

Problem solving

A guide to problem solving.

Nick Dean - Chief Constable Cambridgeshire Constabulary

‘Policing our neighbourhoods’ is at the centre of what we do here in Cambridgeshire. We have taken great strides in placing this at the core of our policing model and the future investment in our neighbourhood teams is welcome. The concept of problem solving as the bedrock of policing; the foundation upon which everything else is built. I am a great believer in investing in tackling the cause of issues and in achieving long term, sustainable solutions. A problem solving approach is vital if we are to make a real difference to our communities. Since my arrival in force I have witnessed some fantastic initiatives making a real difference in improving the quality of life of those we serve. However, problem solving is not just limited to neighbourhoods; it should be at the heart of how we approach issues and concerns in whatever field of work we operate.

Very often communities approach us or our partners when they really need help and we have a duty to respond in a positive way. Of course I recognise that we cannot do everything but those key concerns, affecting people’s quality of life, causing harm and distress to communities should be our priority.

We have invested in problem solving training and guidance and this document adds to the reference material already available. Working together with our communities and partners we can make a real and sustainable difference; that is why I am a real advocate of problem solving.

Cambridgeshire is a safe county but working together and with our communities we can make it even safer, protecting the public by getting to the root cause of issues; taking a problem solving approach allows us to achieve that goal.

I look forward to working alongside you to make a real difference.

Crime prevention is ultimately problem solving

Introduction to problem solving.

The majority of problems we see seem relatively straightforward on the surface, for example, young people causing anti-social behaviour, and we assume we know how to solve them. Nevertheless problems often fail to respond to our interventions. Quite often this is because we haven’t taken the time to properly understand the underlying causes of the problem. South Cambridgeshire Community Safety Partnership has adopted a problem solving approach that will enable you to have a thorough understanding of problems that your community faces and assist you to identify and address the underlying causes at an earlier stage and ultimately prevent a problem becoming a crime.

The benefits of our approach also include:

- A consistent approach to problem solving across the county

- The ability to better co-ordinate problem solving activity with and between partners

- The identification and sharing of effective practice

- A simple process with minimal bureaucracy

Identifying problems

A problem can be defined as:

- A cluster of similar, related or recurring incidents rather than a single incident.

- An issue of substantial community concern

Or a combination of:

- A type of behaviour

- A person(s)

- A special event or time

- A specific desirable object or hot product

Most problems can be resolved with straightforward enforcement and/or prevention measures, and the police and our partner agencies are the initial people that are called. Once that call is made there is an assumption that the matter will be resolved. However where a problem becomes more complex, persistent or includes a risk of harm to a victim/community then a problem solving approach is needed.

A complex problem can be described as:

- A complex or persistent issue that cannot be quickly resolved and which requires to coordinate activity from more than one agency (may include neighbourhood priorities) and often the community itself.

- An issue which presents a high risk of harm to a community or an individual (for example, identified through the vulnerability assessment process).

- A regular event which has a significant impact on police/partner resources/the community (for example, mischief at night).

Once identified however a problem must be managed in a structured and co-ordinated way that addresses the underlying causes.

Think of it as an overflowing bath. You can keep bailing out the water but unless you turn off the tap the problem will still exist.

Please see the below interesting video that describes the SARA model - Scanning/Analysis/Response/Assessment.

We have an issue we would like to tackle – what do we do?

The SARA model is a widely used and effective method to help understand the underlying causes of problems, to identify solutions and to assess the effectiveness of responses.

The model above has been part of policing for over 30 years. Whilst it is important to work through each stage of the model the objective stage may become clear once the scanning stage has been completed. The problem solving plan will help ensure that your responses are robust and effective and will provide a clear audit trail.

The first stage of the model is to ensure that you know there is a problem and what the problem is that you want to solve. The nature of a problem may appear obvious, e.g. young people involved in anti-social behaviour in a shopping precinct. Nevertheless it is important to clearly and concisely define the problem otherwise responses may become too complex and any action you take may fail to get to the root of the problem.

Scanning will enable you to understand the scale of your problem.

Perceptions of crime/community safety and the realities of crime levels/community safety are very different matters. This stage will help you separate the two.

It may be useful to ask yourself some initial questions to help you define the problem:

- Does the problem actually exist? – If the problem has been reported by someone you may need to check against crime and incident data or by speaking to communities, voluntary groups, partner agencies etc.

- How frequently does the problem occur and how long has it been happening?

- What impact is the problem having on our community, police or other agencies?

- Is anyone else already dealing with this problem? Do they know what I know? Can I give them more information to inform their response.

- What are the risks associated with this problem? – Will the problem resolve itself or does it require intervention to stop it. This will inform the type and level of response.

- What do I want to achieve? – This is a crucial question because the effectiveness of any action you take will be judged against the objectives you set. Whilst resolving a problem may be desirable this will not always be possible. Sometimes mitigating or reducing the effects of a problem through raising awareness of the issue will be all you can do.

The answers to these questions serves to assist the police and other agencies to fully acknowledge the impact of the problem and how we can support you to tackle the issue. If this problem is likely to lead to an enforcement initiative, either civilly or criminally then your initial evidence of the scanning phase can be vital to agencies in progressing matters.

Thorough analysis is the key to developing effective solutions. Research should first be directed towards the problem and its causes before you start thinking about solutions, otherwise your actions might not actually deal with the real problem. There are two key elements to the analysis of a problem:

- Understand the problem through research

- Identify possible solutions

Understand the problem through research – Don’t assume you know what is causing it as you may be wrong! It can be useful to develop a working hypothesis about why the problem is occurring but be prepared to challenge and change that hypothesis.

Think of it like an investigation. These questions may be helpful to ask:

- What data is available to help us understand what is happening?

- When is it happening and how often? Are there any key times/days?

- How long has it been going on?

- Where is it happening? What are the features of the location?

- Who is affected and how? Do victims have any common characteristics?

- What events and conditions contribute to the problem?

- What do you know about the perpetrators? Do they have common characteristics?

- Why is it happening? What are the motives of those involved?

- How do the incidents happen? By breaking the problem behaviour down into steps you may that find each step provides an opportunity to intervene.

- What partners should be involved?

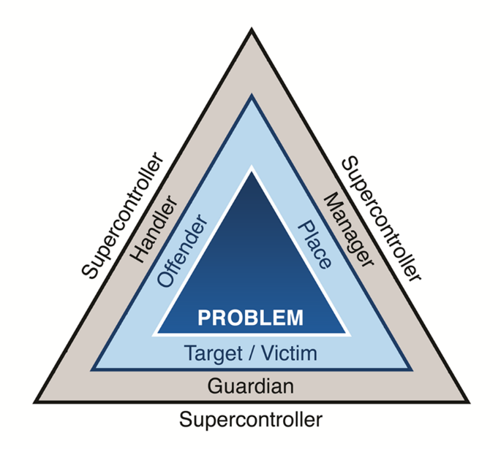

- What other resources are available to get a better understanding of this type of problem (e.g. specialist advice, academic research, College of Policing etc.) Once you’ve been able to answer as many of these questions as you can begin to start to solve the problem through analysis of the information. The best tool for doing this is the Problem Analysis Triangle .

This is based on the idea that a problem can only exist if an offender and victim/target are located at the same place at the same time without the presence of a capable guardian. If you take away one element of the triangle then the problem may not occur.

For most problems, changing some elements of the triangle will have more of an impact than changing others would. In general focus on the parts of the triangle that you and your partners can have the most impact on.

From your analysis you will quickly identify these elements, so where offenders are targeting numerous locations and victims, e.g. burglaries then you would mainly target the offenders. But if those burglaries were at repeat locations with repeat victims, then your approach might be to make those locations and victims less vulnerable e.g. target hardening. It may also be necessary to work with other residents to ensure that no further opportunities are created for a returning offender.

See the Problem Analysis Triangle as a useful tool to 'question' each side of the triangle - what do you know about the offender/victim/location. Then ask yourself what may be missing and what would you need to know.

Identify potential solutions – Having gained a better understanding of the root causes of the problem you need to consider possible solutions. It is unlikely that one intervention on its own will solve the problem. It may well require co-ordinated activity by different agencies.

Remember that any proposals you come up with need to be achievable and proportionate to the threat posed by the problem.

Consider the following:

- How is the problem addressed at the moment and what are the strengths and limitations of the current response?

- What powers or duties do the police or others have to deal with the problem?

- What experience do colleagues or partners have in dealing with this type of problem? – meetings or focus groups can identify things you hadn’t considered.

- What other agencies (such as the voluntary sector) might be able to help?

- What can I do to increase the risk for the offender/s (for example, increasing the likelihood of being caught) or reduce the rewards from their crime (like property marking)?

- What can I do to discourage offending behaviour or divert offenders?

- How can I reduce the likelihood of a person/location being subject to crime/anti-social behaviour?

- What examples of good practice are available? - It is likely that someone somewhere has faced a similar problem. There are plenty of resources available to you to find some good practice.

By this point you should have plenty of information about the problem, a good understanding of the threats posed, an idea about what you want to achieve and the powers and options available to you.

The Response phase involves selecting the most appropriate options available and developing an SARA plan. If other agencies are involved in the response then you should develop the plan in consultation with them and be prepared to negotiate. If you disagree on what works or what options to choose then you might need to compromise or try to influence others. It helps to know what resources/ services other agencies have available to them. For example Local Authority teams can access a range of Early Intervention Services, Registered Social Landlords have a host of tools in their toolbox to manage tenants.

Again, SMART can help you choose the most appropriate actions:

- Specific – Those responsible for delivering an action should have a clear understanding of what it is they are being asked to do.

- Measurable – You need to be able to assess whether the activity has had a direct impact on the problem. What output and outcomes do you expect to see?

- Achievable – Setting unrealistic plans can lead to failure, frustration and a loss of victim/community confidence. Whoever is going to deliver the plan needs to have the capacity, resources and powers to do so.

- Relevant – There should be a clear link between the action you take and what you are trying to achieve.

- Time Bound – You should build in regular reviews of your activity and agree how long the activity will run before it is evaluated. The reviews may form part of existing partnership structures, for example problem solving groups.

In addition your SARA plan should:

- Be proportionate – E.g. covert policing tactics or large numbers of police resources may not be justified by the threat posed by the problem.

- Be sustainable - If a constant resource is the solution, e.g. frequent police patrols, then this itself can become a problem, especially if the reason for engaging in the problem solving itself was to reduce the demand on the police/partners.

- Have an exit strategy to move the solution from a police owned and driven response to a sustainable community-owned response.

- Be cost effective - Funding can often be an issue when it comes to responses – a broad, inclusive partnership can often bid to funding streams that the police, as a sole agency cannot. Some funding streams only allow applications from non-statutory bodies – however if, for example, the local church is one of the stakeholders, then they might bid on behalf of the partnership with the bidding skills of the whole partnership being used to compile the bid.

- ‘Think outside the box’ – Innovative (and even bizarre) initiatives have been the basis for proven long-term solutions.

Having identified options that are SMART you need to agree a delivery plan with partners. The OSARA plan should identify who is responsible for elements of that activity.

- Enforcement – What powers can police or partners employ, including investigating offences, pursuing CBOs, tenancy enforcement etc.

- Prevention – Activity can be focused on any element of the PAT triangle, e.g. target hardening a victim’s address, Neighbourhood Watch, imposing curfews on suspects, encouraging offenders to engage in substance misuse treatment etc.

- Information/Intelligence – Sources of information about a problem should be kept under review and new ones identified. This will help to identify any changes in the nature of a problem as well as evidencing the effectiveness of your response.

- Communication – Consider how you will continue to engage with partners to review activity and share information. You should also consider how you will continue to engage with victim/s and the wider community. This will provide reassurance that you are dealing with their problem and will encourage the flow of information.

The OSARA plan and the details of activity undertaken should be shared between partners so that everyone knows what others are doing. In Cambridgeshire Constabulary this will mostly be NPTs who will be used for this purpose by police and information will need to be shared with partners as laid out in an information sharing agreement.

Regular review meetings should be held during the Response phase. Progress against actions agreed as part of the plan should be reviewed, and an assessment made of whether the plan is likely to achieve the overall objectives. If it isn’t you may need to consider revisiting the Scanning phase.

Evaluation of the response to a problem is critically important in:

- Determining whether the plan was implemented as intended (if not, why not?).

- Determining whether it had the desired effect (did you achieve your goals?).

- Identifying what didn’t work and any changes needed to the plan. This may involve going back round the OSARA model.

- Identifying what did work as well as recognising and sharing good practice.

If we don’t properly evaluate our response, we can never know if what we have done actually had any effect. This is the case even if the problem has stopped because it may have just stopped on its own and not because of our activity.

The assessment can be done using a variety of data which you will have identified during the scanning phase, for example

- Calls for service – Have they increased/decreased?

- Crime and incident data – Has the problem stopped or simply moved elsewhere or changed in nature?

- Victim/Community feedback – What is their perception of the problem now?

- Media and social media reporting reduced or stopped

Debriefing is an important component of evaluation and should always be included and encouraged at the conclusion of all operations or plans where possible. By involving as many stakeholders as you can in any debrief you will gain a holistic view of what went well, what didn’t go well and why?

The details of your evaluation should be recorded on the Problem Solving Plan and retained. This is so that anyone dealing with a similar case in the future will be able to access the details of your problem.

Consideration should be given to whether your response could be considered as good practice.

This may include:

- Innovative ideas that have minimised the impact or solved the problem.

- Introduction of a scheme / initiative that has solved or minimised the problem

- Exceptional multi-agency work to solve a problem

- Successful use of anti-social behaviour powers/legislation to deal with the problem

Where responses have been successful and represent good practice they should be shared. Partnerships and Operational Support can do this via good practice and may share more widely with policing colleagues on Knowledge Hub, so that others who are dealing with similar problems can learn from your experience. By doing this we will be able to build up a local library of effective practice that will help us deliver a consistent service to victims across the County and improve our overall response to crime and anti-social behaviour.

Identifying good practice also provides us with an opportunity to recognise the good work of those involved. It is a chance for anyone to say thank you and well done or even to nominate someone for a commendation or an award.

10 Principles of Crime Prevention

- Target hardening

- Target removal

- Removing the means to commit crime

- Reducing the payoff

- Access control

- Surveillance

- Environment change

- Rule setting

- Increasing the chance of being caught

- Deflecting offenders

|

Twenty-five techniques of situational prevention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Steering column locks and immobilisers - Anti-robbery screens - Tamper-roof packaging |

- Take routine precautions: go out in a group at night, leave signs of occupancy, carry phone - “Cocoon” neighbourhood watch

|

- Off-street parking - Gender-neutral phone directories - Unmarked bullion trucks

|

- Efficient queues and polite service - Expanded seating - Soothing music/muted lights

|

- Rental agreements - Harassment codes - Hotel registration |

|

- Entry phones - Electronic card access - Baggage screening |

- Improved street lighting - Defensible space design - Support whistleblowers

|

- Removable car radio - Women’s refuges - Pre-paid cards for pay phones |

- Separate enclosures for rival soccer fans - Reduce crowding in pubs - Fixed cab fares

|

- “No parking” - “Private property” - “Extinguish camp fires” |

|

- Ticket needed for exit - Export documents - Electronic merchandise tags |

- Taxi drivers IDs - “How’s my driving?” decals - School uniforms |

- Property marking - Vehicle licensing and parts making - Cattle branding |

- Control on violent pornography - Enforce good behaviour on soccer field - Prohibit racial slurs

|

- Roadside speed display boards - Signatures for customs declarations - “Shoplifting is stealing” |

|

- Street closures - Separate bathrooms for women - Disperse pubs |

- CCTV for double-deck buses - Two clerks for convenience stores - Reward vigilance |

- Monitor pawn shops - Controls on classified ads - Licensing street vendors |

- “Idiots drink and drive” - “It’s OK to say no” - Disperse troublemakers at school

|

- Easy library checkout - Public lavatories - Litter bins |

|

- “Smart” guns - Disabling stolen cell phones - Restrict spray paint sales to juveniles |

- Red light cameras - Burglar alarms - Security guards |

- Ink merchandise tags - Graffiti cleaning - Speed humps |

- Rapid repair of vandalism - V-chips in TVs - Censor details of modus operandi

|

- Breathalyzers in pubs - Server intervention - Alcohol-free events |

Contact Details

By selecting continue you are consenting to us setting cookies. We do not store personal information.

Criminal Justice Know How

We connect community with the criminal justice system.

- Law Enforcement

The S.A.R.A. Model

by Kelly M. Glenn, 2020

When we prevent crime, we prevent victimization, which is the ultimate goal! Several theories exist involving crime prevention, including (but not limited to):

- Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (C.P.T.E.D.)

- The Broken Window Theory

- The S.A.R.A. Model (Scan, Analyze, Respond, Assess)

- The Crime Prevention Triangle

The S.A.R.A. Model of crime prevention is a part of what was coined as “Problem-Oriented Policing” by Herman Goldstein in 1979. Problem-Oriented Policing, or POP, was a response to reactive, incident-driven policing in which successes in addressing community problems were short-lived. Before we get into how the S.A.R.A. Model changed that, let’s take a look at an example of a law enforcement response that would be considered reactive and incident-driven with short-lived success:

Officer Comar was assigned to patrol a densely populated downtown area where foot traffic was fairly moderate. Maris, owner of a local convenience store, called 9-11 nearly every day wanting the police department to come run off the drunks that would come into her store, buy a beer, and then hang around on her sidewalk drinking and asking other patrons to buy them more alcohol. For Maris, her store felt more like a get together for middle-aged men who traded showers, shaving, and jobs for getting drunk on her doorstep by 10 a.m. Once the store closed for the night, she would spend considerable time waking up the ones that had passed out and cleaning up their trash. Her main complaint, though, was that they alienated customers and that she was losing good business because of them. Going to the store and running them off was part of Officer Comar’s daily routine. In fact, because she went so often, she got into the habit of pulling into the parking lot, even if Maris didn’t call, hitting her siren, and watching them disperse. Officer Comar considered this good, proactive police work, and Maris was happy that she didn’t always have to pick up the phone to solve the problem.

In our scenario, we can clearly identify a community problem: the local convenience store was overrun by alcohol addicts, and law-abiding citizens were avoiding the business to avoid the drunks. But was Officer Comar truly doing good, proactive police work by showing up several times a shift to run them off, and was Maris getting the best service from her local police department?

We’ll find out!

In 1987, Eck and Spelman built upon the Problem-Oriented Policing approach by using the S.A.R.A. Model to address community problems and crime. S.A.R.A. looks to identify and overcome the underlying causes of crime and disorder versus just treating the symptoms. It can be applied to any community problem by implementing each of four steps in the model: Scanning, Analysis, Response, and Assessment.

First Step – Scanning

During the scanning phase, law enforcement works with community members to identify existing or potential problems and prioritize them. It’s helpful to answer a few questions within this phase:

- Is this problem real or perceived? For example, do the 291 calls for service to report speeders in a residential area really mean that drivers are exceeding the speed limit? Or, are the calls coming from one resident who is irritated that drivers won’t slow down to below the speed limit when she crosses the street to check her mail?

- What are the consequences of not addressing this problem? Are the consequences merely a matter of inconvenience for some people, or does this particular problem impact the health, safety, prosperity, happiness, etc. of community members?

- How often does this problem occur? Is it daily? Weekly? Just during certain seasons, or when a big event occurs in town?

If we think about Maris and her convenience store, we can clearly identify a few existing symptoms of a problem. First, Maris is losing business due to the drunks hanging out on her sidewalk all day. Second, other community members who may rely on this convenience store as their easiest option for groceries and goods, may be avoiding it to avoid the drunks. Third, Maris is maintaining somewhat of a common nuisance. She has an environment that is conducive to crime and disorder, which is creating a burden on local police services. Prioritizing this community problem and reducing or eliminating the aforementioned symptoms by tackling the root cause(s) could be a win for many people. Let answer the above questions with our scenario in mind:

- Is this problem real or perceived? The problem is real. Maris’s declining sales, the police department’s calls for service, and Officer Comar’s own observations and actions support the legitimacy of the issue.

- What are the consequences of not addressing this problem? This problem will not go away on its own. In fact, if trouble loves company, we can predict that the group of drunks will continue to grow, thus increasing the calls for service to the police department. Additionally, Maris’s business will continue to struggle, and without enough customers, the convenience store could eventually close, creating a burden for citizens who do depend upon it.

- How often does this problem occur? As calls for service show, this problem is a daily occurance. More than likely, it is a bigger problem during fair weather than when it’s cold or rainy; however, the problem is consistent and reocurring.

Now that we’ve scanned for the community problem, identified it, and prioritized it by answering some questions, let’s tackle our next step!

Second Step: Analysis

When we analyze a known community problem, we use relevant data to learn more. Our goal is to be effective in reducing or eliminating it, so we must pinpoint possible explanations for why or how the problem is occuring. Again, we can ask some useful questions to guide us:

- What relevant data is available? Statistics? Calls for service? Demographics?

- What are some possible explanations for why or how the problem is occuring? Are there environmental issues? Is there a behavioral issue? Is there a lack of appropriate legislation or policy to enforce a solution? Is there a lack of community services?

- What is currently being done to address the problem? Is anything at all being done? If something is being done, why is it ineffective? Who is involved in the current response? What resources are being dedicated to the current response?

Let’s take a look at how we can answer these questions when working with Maris within our scenario:

- What relevant data is available? Maris can provide records for declining sales, and they can be compared to various seasons of the year when weather may impact the gatherings of the local drunks outside of her convenience store. The police department can use the number of calls for service, as well as data on how each call for service was cleared (arrest, warning, report, etc.). The police department can also see if other more serious crimes are linked to this problem (physical fights between drunks, thefts out of customer vehicles, etc.). Collectively, they can identify the average ages of the individuals, as well as their socioeconomic status.

- Maris’s store is open to the public, and the drunks are part of the public.

- Maris’s store is located in an area that is accessible to foot traffic, and these drunks live in nearby housing.

- These drunks suffer from an addiction to alcohol, and Maris sells beer.

- The drunks can pay for the beer whether it be from money they earn, money they receive in public assistance, or money that is given to them by other generous customers.

- Maris calls the police department when she wants the drunks to leave; although sometimes, Officer Comar will automatically address the issue when she drives by.

- The current response is ineffective because the drunks come back later and/or return the following day.

- Maris, Officer Comar, and the local police department are involved in the current response.

- The current response depletes the taxpayer funded resources via the use of the local police department.

Now that a lot of the brain work is done, it’s time to turn ideas into action. Let’s take a look at the third step in the S.A.R.A. Model:

Third Step: Response

In this phase of addressing crime, law enforcement and community partners work together to identify and select responses, or interventions, that are most likely to lead to long-term success in reducing or eliminating the community problem they have scanned and analyzed.

Two questions should be asked during this phase:

- What are some possible ways to address the problem? Do we need more community partners? Do we need to alter access? Do we need to install monitoring devices? Does a law or policy need to be implemented or changed? Do we need to better enforce the ones we already have? Do we need to make a list of community services and make referrals?

- Which of the potential responses are going to be most successful? Which interventions will attack the root causes, not the symptoms? What interventions will have a positive long-term impact?

Using our scenario, let’s list some possible ways to address Maris’s problem at her convenience store, as well as select the interventions that are likely going to lead to long-term success. Remember, this is a team effort, and Maris definitely should have some input!

- Although Maris’s store is open to the public, her business is privately owned and located on private property. Existing laws in her locality protect private business and property owners by allowing them to bar people from the property as long as it is not discriminatory based on protected classes, so Maris does have the legal authority to ban the drunks from her property and business. During a meeting with the police department, in which everyone is sharing information and working together to come up with a response plan, Officer Comar confirms what Maris already suspected: many of these addicts have long histories of arrests for public intoxication, trespassing, etc., and going to jail for a night or two isn’t much of a deterrent for them. While she can go through the effort of barring each one and the police department can make arrests, both she and the police department agree that it’s not the most effective route for long-term success. This intervention was eliminated from the response plan.

- Maris’s store is accessible to foot traffic, which is both a blessing and a curse. There is nothing she can do or wants to do to alter the way her customers enter her business or property. With that said, Maris does not have “No Loitering” signs posted on the property, and her locality has enforceable loitering laws. “No Loitering” signage could motivate customers to make their necessary transactions and leave, but she has always been hesitant to put them up because she does not want to appear “unfriendly” to youth who come by and chat over a bag of chips and a soda. She also learns that despite there being a local ordinance against loitering, the local judges are hesitant to impose any significant sanctions for it. Maris opts not to install “No Loitering” signage. This intervention was eliminated from the response plan.