Essay on Organ Donation for Students and Children

500+ words essay on organ donation.

Essay on Organ Donation – Organ donation is a process in which a person willingly donates an organ of his body to another person. Furthermore, it is the process of allowing the removal of one’s organ for its transplanting in another person. Moreover, organ donation can legally take place by the consent of the donor when he is alive. Also, organ donation can also take place by the assent of the next of kin of a dead person. There has been a significant increase in organ donations due to the advancement of medical science.

Organ Donation in Different Countries

First of all, India follows the opt-in system regarding organ donation. Furthermore, any person wishing to donate an organ must fill a compulsory form. Most noteworthy, this form is available on the website of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. Also, The Transplantation of Human Organs Act 1994, controls organ donation in India.

The need for organ donation in the United States is growing at a considerable rate. Furthermore, there has also been a significant rise in the number of organ donors in the United States. Most noteworthy, organ donation in the United States takes place only by the consent of the donor or their family. Nevertheless, plenty of organizations are pushing for opt-out organ donation

Within the European Union, the regulation of organ donation takes place by the member states. Furthermore, many European countries have some form of an opt-out system. Moreover, the most prominent opt-out systems are in Austria, Spain, and Belgium. In England, no consent is presumed and organ donation is a voluntary process.

Argentina is a country that has plenty of awareness regarding organ donation. Most noteworthy, the congress of Argentina introduced an opt-out organ donation policy. Moreover, this means that every person over 18 years of age will be a donor unless they or their family state their negative. However, in 2018, another law was passed by congress. Under the new law, the family requirement was removed. Consequently, this means that the organ donor is the only person who can state their negative.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Benefits of Organ Donation

First of all, organ donation is very helpful for the grieving process. Furthermore, many donor families take relief and consolation due to organ donation. This is because they understand that their loved one has helped save the life of other people. Most noteworthy, a single donor can save up to eight lives.

Organ donation can also improve the quality of life of many people. An eye transplant could mean the ability to see again for a blind person. Similarly, donating organs could mean removing the depression and pain of others. Most noteworthy, organ donation could also remove the dependency on costly routine treatments.

Organ donation is significantly beneficial for medical science research. Donated organs offer an excellent tool for conducting scientific researches and experiments. Furthermore, many medical students can greatly benefit from these organs. Most noteworthy, beneficial medical discoveries could result due to organ donation. Organ donation would also contribute to the field of Biotechnology.

To sum it up, organ donation is a noble deed. Furthermore, it shows the contribution of an individual even after death. Most noteworthy, organ donation can save plenty of lives. Extensive awareness regarding organ donation must certainly be spread among the people.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Organ Donation Essay

Table of Contents

Organ donation has proved to be a miracle for the society. Organs such as kidneys, heart, eyes, liver, small intestine, bone tissues, skin tissues and veins are donated for the purpose of transplantation. The donor gives a new life to the recipient by the way of this noble act. Organ donation is encouraged worldwide. The government of different countries have put up different systems in place to encourage organ donation. However, the demand for organs is still quite high as compared to their supply. Effective steps must be taken to meet this ever-increasing demand.

Fill Out the Form for Expert Academic Guidance!

Please indicate your interest Live Classes Books Test Series Self Learning

Verify OTP Code (required)

I agree to the terms and conditions and privacy policy .

Fill complete details

Target Exam ---

Long and Short Essay on Organ Donation in English

We have provided below short and long essay on organ donation in simple English for your information and knowledge.

After going through the essays you will know the significance of organ donation for someone in need, the procedure involved, under what circumstances is it illegal to donate an organ and what are safe physical criterion for organ donation.

You can use these organ donation essay in your school college events wherein you need to give a speech, write an essay or take part in debate.

Essay on Organ Donation in 200 words

Organ donation is done by both living and deceased donors. The living donors can donate one of the two kidneys, a lung or a part of a lung, one of the two lobes of their liver, a part of the intestines or a part of the pancreas. While a deceased donor can donate liver, kidneys, lungs, intestines, pancreas, cornea tissue, skin tissue, tendons and heart valves.

The organ donation process varies from country to country. The process has broadly been classified into two categories – Opt in and Opt out. Under the opt-in system, one is proactively required to register for donation of his/ her organs while in the opt-out system, every individual becomes a donor post death unless he/she opts-out of it.

There is a huge demand for organs. It is sad how several people in different parts of the world die each year waiting for organ transplant. The governments of different countries are taking steps to raise the supply of organs and in certain parts the number of donors has increased. However, the requirement of organs has simultaneously increased at a much rapid speed.

Each one of us should come forward and register to donate organs after death. “Be an organ donor, all it costs is a little love”.

Also Check: Essay on Organ Trafficking

Essay on Organ Donation in 300 words

Organ donation takes place when an organ of a person’s body is removed with his consent while he is alive or with the consent of his family member after his death for the purpose of research or transplant. Kidneys, liver, lungs, heart, bones, bone marrow, corneas, intestines and skin are transplanted to give new life to the receiver.

Organ Donation Process

- Living Donors

Living donors require undergoing thorough medical tests before organ donation. This also includes psychological evaluation of the donor to ensure whether he understands the consequences of donation and truly consents for it.

- Deceased Donors

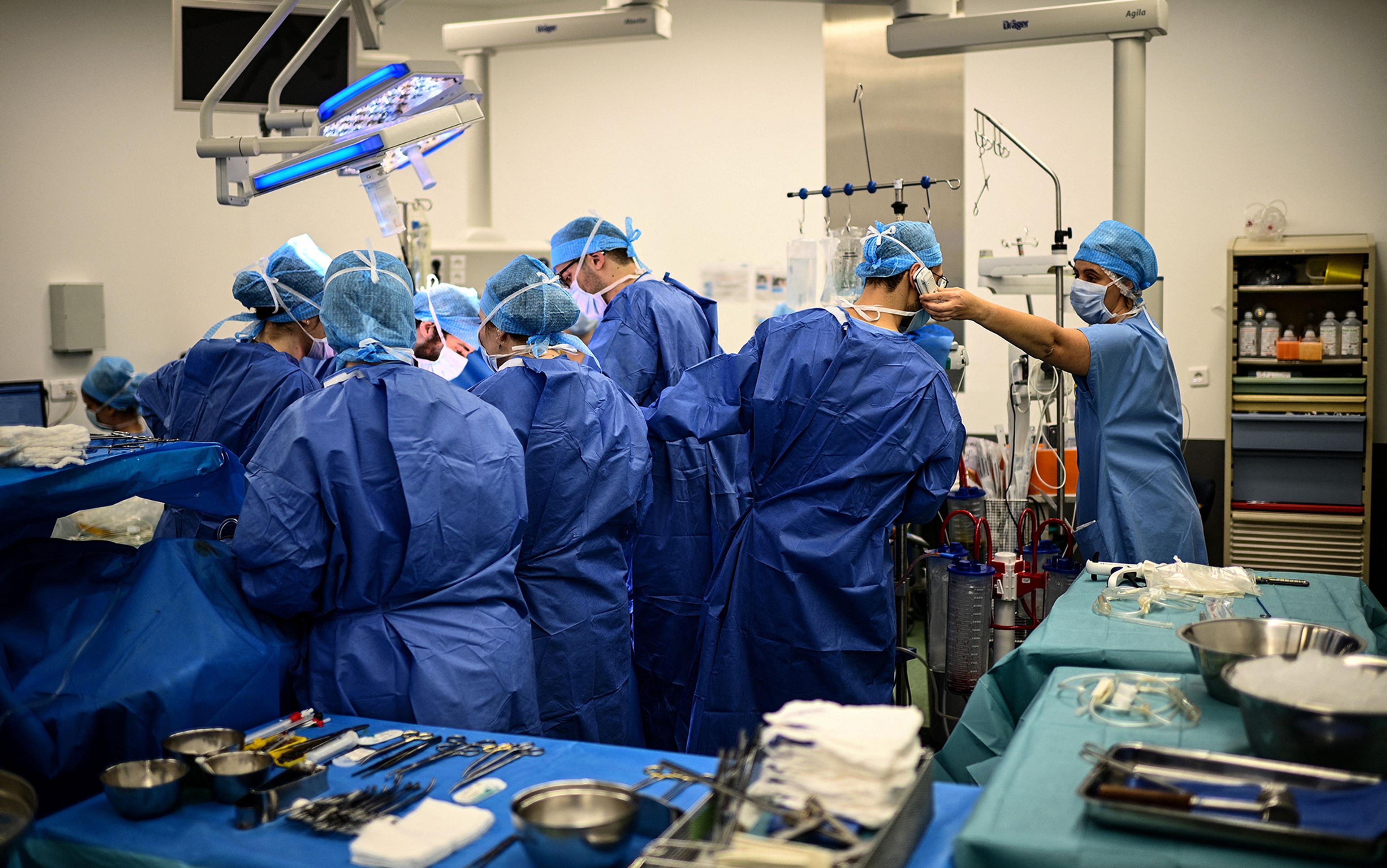

In case of the deceased donors, it is first verified that the donor is dead. The verification of death is usually done multiple times by a neurologist. It is then determined if any of his/ her organs can be donated.

After death, the body is kept on a mechanical ventilator to ensure the organs remain in good condition. Most organs work outside the body only for a couple of hours and thus it is ensured that they reach the recipient immediately after removal.

Gap between Demand and Supply

The demand for organs is considerably higher than the number of donors around the world. Each year several patients die waiting for donors. Statistics reveal that in India against an average annual demand for 200,000 kidneys, only 6,000 are received. Similarly, the average annual demand for hearts is 50,000 while as low as 15 of them are available.

The need for organ donation needs to be sensitized among the public to increase the number of donors. The government has taken certain steps such as spreading awareness about the same by way of TV and internet. However, we still have a long way to go.

Organ donation can save a person’s life. Its importance must not be overlooked. A proper system should be put in place for organ donation to encourage the same.

Essay on Organ Donation in 400 words

Organ donation is the process of allowing organ or tissue to be removed surgically from one person to place it in another person or to use it for research purpose. It is done by the consent of donor in case he is alive or by the consent of next of kin after death. Organ donation is encouraged worldwide.

Kidneys, liver, lungs, heart, bones, bone marrow, skin, pancreas, corneas, intestines and skin are commonly used for transplantation to render new life to the recipient. Organ donation is mostly done after the donor’s death. However, certain organs and tissues such as a kidney, lobe of a lung, portion of the liver, intestine or pancreas can be donated by living donors as well.

Organ Donation Consent Process

There are two types of consents when it comes to organ donation. These are the explicit consent and the presumed consent.

- Explicit Consent: Under this the donor provides a direct consent through registration and carrying out other required formalities based on the country.

- Presumed Consent: This does not include a direct consent from the donor or the next of kin. As the name suggests, it is assumed that the donation would have been allowed by the potential donor in case consent was pursued.

Among the possible donors approximately twenty five percent of the families deny donation of their loved one’s organs.

Organ Donation in India

- Legalised by Law

Organ donations are legal as per the Indian law. The Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA), 1994 enacted by the government of India permits organ donation and legalizes the concept of brain death.

- Documentation and Formalities

The donor is required to fill a prescribed form. The same can be taken from the hospital or other medical facility approached for organ donation or can be downloaded from the ministry of health and family welfare government of India’s website.

In case of a deceased donor, a written consent from the lawful custodian is required in the prescribed application form.

As is the case with the rest of the world, the demand of organs in India is much higher compared to their supply. There is a major shortage of donated organs in the country. Several patients are on the wait list and many of them succumb to death waiting for organ transplant.

The government of India is making efforts to spread awareness about organ transplant to encourage the same. However, it needs to take effective steps to raise the number of donors.

Essay on Organ Donation in 500 words

Organ donation refers to the process of giving organs or tissues to a living recipient who requires a transplant. Organ donation is mostly done after death. However, certain organs can be donated even by a living donor.

The organs that are mostly used for the purpose of transplant include kidney, liver, heart, pancreas, intestines, lungs, bones and bone marrow. Each country follows its own procedure for organ donation. Here is a look at how different countries encourage and process organ donation.

Organ Donation Process – Opt In and Opt Out

While certain countries follow the organ donation opt-in procedure others have the opt-out procedure in place. Here is a look at the difference between these two processes of organ donation:

- Opt In System: In the opt-in system, people are required to proactively sign up for the donation of their organs after death.

- Opt Out System: Under this system, organ donation automatically occurs unless a person specifically makes a request to opt out before death.

Organ Donation in Different Countries

India follows the opt-in system when it comes to organ donation. Anyone who wishes to donate organs needs to fill a prescribed form available on the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India’s website.

In order to control organ commerce and encourage donation after brain death, the government of India came up with the law, The Transplantation of Human Organs Act in the year 1994. This brought about a considerable change in terms of organ donation in the country.

Spain is known to be the world leader in organ donations. It follows the opt-out system for organ donation.

- United States

The need for organs in the United States is growing at a rapid pace. Though there has been a rise in the number of organ donors, however, the number of patients waiting for the organs has increased at a much higher rate. Organ donation in the United States is done only with the consent of the donor or their family. However, several organizations here are pushing for the opt-out organ donation.

- United Kingdom

Organ donation in the United Kingdom is voluntary. Individuals who want to donate their organs after death can register for the same.

This is the only country that has been able to overcome the shortage of transplant organs. It has a legal payment system for organ donation and is also the only country that has legalized organ trade.

Organ donation is quite low in Japan as compared to other western countries. This is mainly due to cultural reasons, distrust in western medicines and a controversial organ transplant that took place in 1968.

In Columbia, the ‘Law 1805’ passed in August 2016, introduced the opt-out policy for organ donation.

Chile opted for the opt-out policy for organ donation under the, ‘Law 20,413’ wherein all the citizens above the age of 18 years will donate organs unless they specifically deny it before death.

Most of the countries around the world suffer from low organ donor rate. The issue must be taken more seriously. Laws to increase the rate of organ donation must be put in place to encourage the same.

Essay on Organ Donation in 600 words

Organ Donation is the surgical removal of a living or dead donor’s organs to place them in the recipient to render him/her a new life. Organ donation has been encouraged worldwide. However, the demand of human organs far outweighs the supply. Low rate of organ donation around the world can be attributed to various reasons. These reasons are discussed below in detail.

Teleological Issues

The moral status of the black market organ donation is debatable. While some argue in favour of it others are absolutely against the concept. It has been seen that those who donate their organs are generally from the poor section of the society and those who can afford these are quite well off. There is thus an imbalance in the trade.

It has been observed that those who can purchase the organs are taking advantage of the ones who are desperate to sell. This is said to be one of the reasons for the rising inequality of status between the rich and the poor. On the other hand, it is argued that those who want to sell their organs should be allowed to do so as preventing them from it is only contributing to their status as impoverished. Those who are in favour of the organ trade also argue that exploitation is preferable to death and hence organ trade must be legalized. However, as per a survey, later in life the living donors regret their decision of donating their organs.

Several cases of organ theft have also come forward. While those in support of the legalization of organ market say that this happens because of the black market nature of trade while others state that legalizing it would only result in the rise of such crimes as the criminal can easily state that the organ being sold has not been stolen.

Deontological Issues

These are defined by a person’s ethical duty to take action. Almost all the societies in the world believe that donating organs voluntarily is ethically permissible. Many scholars believe that everyone should donate their organs after death.

However, the main issue from the standpoint of deontological ethics is the debate over the definitions of life, death, body and human. It has been argued that organ donation is an act of causing self harm. The use of cloning to come up with organs with a genotype identical to the recipient is another controversial topic.

Xenotransplantation which is the transfer of animal organs into human bodies has also created a stir. Though this has resulted in increased supply of organs it has also received a lot of criticism. Certain animal rights groups have opposed the sacrifice of animals for organ donation. Campaigns have been launched to ban this new field of transplantation.

Religious Issues

Different religious groups have different viewpoints regarding organ donation. The Hindu religion does not prohibit people from donating organs. The advocates of the Hindu religion state that it is an individual choice. Buddhists share the same view point.

The Catholics consider it as an act of love and charity. It is morally and ethically acceptable as per them. The Christian Church, Islam, United Methodists and Judaism encourage organ donation. However, Gypsies tend to oppose it as they believe in afterlife. The Shintos are also against it as they believe that injuring a dead body is a heinous crime.

Apart from this, the political system of a country also impacts organ donation. The organ donation rate can increase if the government extends proper support. There needs to be a strong political will to ensure rise in the transplant rate. Specialized training, care, facilities and adequate funding must be provided to ensure a rise.

The demand for organs has always been way higher than their supply due to the various issues discussed above. There is a need to focus on these issues and work upon them in order to raise the number of organ donors.

Essay on Organ Donation FAQs

How do you write an organ donation essay.

To write an organ donation essay, start with an introduction explaining its importance, discuss benefits, address common concerns, and conclude with a call to action for readers to consider becoming donors.

What is a short note on organ donation?

Organ donation involves willingly giving one's organs after death to save lives. It's a selfless act that can bring hope and health to those in need.

How important is organ donation?

Organ donation is crucial as it saves lives by providing organs to individuals suffering from organ failure, offering them a chance for a healthier and longer life.

What is the aim of organ donation?

The aim of organ donation is to provide organs and tissues from willing donors to those in need, improving the quality of life and increasing survival rates for recipients.

What are the 4 types of organ donation?

The four types of organ donation include deceased donation (after death), living donation (from a living person), paired exchange (swapping organs between two donor-recipient pairs), and directed donation (to a specific person).

What is the concept of organ donation?

Organ donation is the voluntary act of giving one's organs or tissues to save or enhance the lives of others, often occurring after death or, in some cases, while the donor is still alive.

Which organ Cannot be donated?

The brain cannot be donated for transplantation. While other organs like the heart, liver, kidneys, and lungs can be donated, the brain's complex functions make it ineligible for donation.

Related content

Talk to our academic expert!

Language --- English Hindi Marathi Tamil Telugu Malayalam

Get access to free Mock Test and Master Class

Register to Get Free Mock Test and Study Material

Offer Ends in 5:00

Organ Donation: Opportunities for Action (2006)

Chapter: 1 introduction, 1 introduction.

I n the 50 years since the first successful organ transplant, thousands of recipients of a transplanted kidney, heart, pancreas, liver, or other solid organ in the United States and throughout the world have had their lives extended and their health enhanced as a result of organ transplantation.

Organ transplantation is unique among surgical procedures, in that the procedure cannot take place without the donation of an organ or a partial organ from another person. Since 1988, more than 390,000 organs have been transplanted, with approximately 80 percent of the transplanted organs coming from deceased donors. In 2005, 7,593 deceased donors provided 23,249 transplanted organs in the United States, and there were 6,896 living donors (OPTN, 2006 1 ).

The success of organ transplantation as a treatment option, the rising incidence of related or contributory medical conditions, improvements in immunosuppressive medications, and other factors have resulted in a rapid escalation in the waiting list for transplantation 2 in recent decades. In 1988, there were 16,026 individuals on the waiting list for an organ transplant; by 1995 the waiting list had increased almost 275 percent to 43,937; and it

FIGURE 1-1 Growth in the number of transplants and in the number of candidates on the transplant waiting list.

SOURCE: HRSA and SRTR (2006).

has since more than doubled so that by January 2006 the waiting list topped 90,000 individuals ( Figure 1-1 ) (IOM, 1999; OPTN, 2006). The waiting list is primarily driven by the need for kidney transplants. The statistics on the transplant waiting list are continually updated, and as of March 24, 2006, there were 91,214 transplant candidates 3 on the waiting list, of whom 65,917 individuals (approximately 70 percent of the waiting list) were candidates for kidney transplantation. In 2005, 44,619 transplant candidates were added to the waiting list (OPTN, 2006).

As the demand for organ transplants far exceeds the current supply of available organs, various efforts are under way to determine how best to reduce the gap between supply and demand. In addition to refinements in hospital processes and protocols, several proposals are being discussed that

might further enhance the system or provide incentives for more individuals or families to consent to organ donation.

In 2004, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and The Greenwall Foundation asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to study the issues involved in increasing the rates of organ donation. This report is the result of a 16-month study conducted by an IOM committee composed of experts in the fields of bioethics, law, health care, organ donation and transplantation, economics, sociology, emergency care, end-of-life care, and consumer decision making.

SCOPE OF THIS REPORT

The IOM committee was charged with reviewing the current efforts and proposals to increase organ donations from deceased donors, including but not limited to educational activities, media campaigns, financial incentives, and presumed-consent laws. The committee was asked to identify ethically controversial proposals and, for those proposals, to

evaluate and address the impact that these proposals may have on existing donation efforts and public perceptions regarding organ donation;

evaluate and address the impact that these proposals may have on specific groups, such as ethnic minorities (specifically, African Americans), socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals, those likely to be disproportionately affected by the proposal, and living donors;

make recommendations about whether particular alterations can be made to various proposals to reduce ethical problems; and

provide recommendations regarding the cost-effectiveness, feasibility, and practicality of implementing such proposals.

To address its charge, the committee held five meetings and gathered information by holding a scientific workshop (see Appendix B for the workshop agenda) and two public comment sessions, talking with numerous individuals in the organ transplantation field, and conducting a literature review. The committee developed a set of perspectives and principles that guided its consideration of the complex issues that it was asked to address ( Chapter 3 ). This report benefits from the work of prior IOM committees that examined organ allocation and donation after circulatory determination of death (IOM, 1997, 1999, 2000). However, this report focuses on organ donation, not on the equally complex issues of organ allocation. Furthermore, it focuses on solid-organ donation and does not address eye and tissue donation. Finally, this report concentrates on increasing rates of deceased donation and considers living donation only briefly in Chapter 9 .

To set the context for the report, this chapter provides an overview of the history and current status of the U.S. system of organ donation and

transplantation and describes in brief some of the organ donation policies and practices of other countries. The chapter also highlights the committee’s thoughts on the evolving terminology in the field of organ donation, provides a discussion of the economic value of increasing the organ supply, and concludes with an emphasis on the benefit of preventive measures to reduce the demand for organ transplantation and minimize the rejection of transplanted organs.

OVERVIEW AND HISTORY OF THE CURRENT U.S. SYSTEM

The current U.S. system of organ donation, recovery, allocation, and transplantation has developed and evolved during the past 50 years. In 1954, the first successful U.S. transplantation involved the transplantation of a kidney between living twin brothers (Merrill et al., 1956). Immunosuppressive medications began to be used in the late 1950s, leading to the first successful transplantation of a kidney from a deceased donor in 1962 (Halloran and Gourishankar, 2001). This transplantation involved an unrelated donor and recipient and the use of the immunosuppressive drug azathioprine (Morrissey et al., 2001). Cyclosporine, discovered in 1978, provided significantly improved immunologic tolerance; and numerous subsequent pharmacologic, surgical, and clinical advances have continued to improve the rates of graft survival and reduce the potential for organ rejection. The growth and development of the field of organ transplantation and the nature of its organization and structure have been guided by state and federal laws and regulations ( Box 1-1 ).

Clarifying Criteria for Determination of Death

The early transplants were generally the result of donations of kidneys from living donors or donations of organs from deceased donors who had been declared dead following the irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function (DeVita et al., 1993). In the late 1960s, improvements in mechanical ventilation and other types of medical support to sustain cardiopulmonary function highlighted the need to clarify the criteria for determining death. This led to clarification of the determination of death by circulatory criteria and to examination of the concept of determining death by neurologic criteria (Report of the Ad Hoc Committee, 1968; Guidelines for the determination of death, 1981). As a result, in addition to clarification of the criteria for the diagnosis of death by irreversible cessation of circulatory function, criteria were developed for the diagnosis of death based on the irreversible loss of function of the whole brain, including the brain stem (neurologic criteria). These criteria were incorporated into the Uniform Determination of Death Act, which was codified into state law in

various forms. For each set of criteria the diagnosis of death requires both the cessation of function and irreversibility (Guidelines for the determination of death, 1981). The use of neurologic criteria for the determination of death has gained wide medical, legal, ethical, and public acceptance in the United States, although debates continue (Bernat, 2005; Laureys, 2005).

Growth and Organization of the Transplantation Field

The increased number of transplantation operations in the 1970s and 1980s and concerns about the allocation of donated organs led to an expanded role for organ procurement organizations (OPOs), some of which had emerged in the 1960s as localized efforts. In 1972, legislation authorized Medicare coverage for kidney transplantation as a treatment for end-stage renal disease. In 1978, amendments to that legislation increased the length of availability of Medicare benefits after a successful kidney transplant from 1 year to 3 years and also increased coverage of kidney acquisition costs and home dialysis costs (Eggers, 2000). The next breakthrough in transplantation came with the advent of reliable and effective immunosuppressive medications to improve graft functioning and survival for patients posttransplantation.

The growing demand for organ transplantation, controversies regarding the allocation of organs, and concerns about payment for organs prompted congressional hearings on organ transplantation in the early 1980s. The resulting federal legislation, the National Organ Transplant Act of 1984, prohibited the sale of human organs; established a task force to address organ donation and allocation issues; and established the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN).

OPTN is charged with developing policies for and implementing an equitable system of organ allocation, maintaining the waiting list of potential recipients, and compiling data from U.S. transplant centers (OPTN, 2004). The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a nonprofit, private voluntary organization, has been the sole administrator of OPTN since the initial contract was awarded in 1986. Oversight for the OPTN contract is provided by the Division of Transplantation in the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. OPOs and transplant centers are required to participate in OPTN. OPTN’s oversight responsibilities focus on solid organ donation and transplantation from deceased donors. OPTN has limited responsibilities regarding living donation and does not have oversight responsibilities regarding tissue donation and distribution, although most OPOs recover tissue as well as solid organs, and a few OPOs are involved in tissue processing.

Currently, the organ donation and transplantation system in the United States is coordinated by 58 OPOs serving unique geographic areas (donor service areas) ( Figure 1-2 ). When a donated organ becomes available, the organ allocation algorithms developed by OPTN-UNOS identify a potential recipient on the basis of multiple factors, including severity of disease; geographic proximity; and blood, tissue, and size matches with the donor. Ongoing efforts are made to ensure impartiality in the allocation process. OPOs are charged with working with individuals, families, and hospital staff to explore consent for and facilitate organ donation; evaluating the

FIGURE 1-2 Donor service areas. Reprinted courtesy of the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations.

medical eligibility of potential donors; coordinating the recovery, preservation, and transportation of donated organs; and educating the public about organ donation (UNOS, 2006).

In addition to the OPOs, the other key organizations involved with organ donation are the donor hospital and the transplant center. Although organ donation, recovery, and transplantation may all occur in the same medical center, it is often the case that the organs are recovered in the donor hospital and are then transported to several transplant centers in the region or across the country. In 2005, 267 transplant centers were operating approximately 865 transplant programs in the United States (UNOS, 2005). This represents significant growth from the 244 transplant programs functioning in 1984 (UNOS, 2004). The number of annual organ transplants

has also significantly increased, from an estimated 7,692 in 1984 to 28,110 in 2005 (UNOS, 2004; OPTN, 2006).

Some of the challenges in further improving the organ donation system result from the heterogeneity of the OPOs, donor hospitals, and transplant centers, each of which serves populations with different demographics. Furthermore, the priorities and norms of the OPOs vary, such as in their approaches to families and their policies on donation after circulatory determination of death (Chapters 4 and 5 ). For example, there is variability in the rates at which consent is obtained for deceased organ donation in various transplant centers and OPOs ( Chapter 4 ). A 2003 study examining the variability among 190 transplant centers found that 30 centers (16 percent) had consent rates of 70 percent or higher, whereas 18 centers had consent rates below 30 percent (DHHS, 2003). This is similar to the variation of donation rates reported by OPOs, which ranged from 34.3 to 77.9 percent in 2004 (SRTR, 2005). As discussed throughout this report, efforts by OPOs and participating hospitals to increase the availability of organs for transplantation are focusing on increasing the consent rate for donation as well as on increasing the population of potential donors.

Although this report focuses on solid organ donation, many of the matters it discusses are closely tied with tissue donation. However, the tissue recovery and distribution system is quite different, particularly in the extent of private-sector commercial involvement. The resulting issues and challenges impact both the solid organ and tissue donation and recovery systems (Youngner et al., 2004).

Deceased Organ Donation

In the United States, deceased organ donation is an opt-in system in which the donation decision is made by the individual or by his or her family.

Most current U.S. transplantations from deceased donors result from deaths determined by neurologic criteria. The donor-eligible deaths determined by neurologic criteria—estimated to number between 10,500 and 16,800 per year—represent only a small fraction of the more than 2 million annual deaths in the United States (Guadagnoli et al., 2003; Sheehy et al., 2003; NCHS, 2005). For deaths determined by neurologic criteria, organ viability can be maintained through ventilatory support and thereby improve opportunities for successful transplantation. Death determined by circulatory criteria is much more common in the population at large, but, because it often occurs outside of the hospital setting, maintaining the viability of the organs presents distinct challenges ( Chapter 5 ).

The Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA) of 1968 specified that the donor’s authorization to donate is legally binding, and the subsequent

amendment of UAGA in 1987 assigned explicit priority to the donor’s intent even if his or her family objected to donation. In several states, the individual’s decision to donate is recorded on an organ donor card, on the individual’s driver’s license, or in a donor registry and is as legally binding as an advance directive regarding end-of-life care (DHHS, 2000). In practice, however, organ donation and recovery involve a complex set of circumstances and decisions.

When the individual’s wishes regarding donation are not known, discussions between the family of the deceased individual and the OPO and hospital staff focus on the opportunity for donation and the family is asked to make a decision about donation. Families often view organ donation as a way to redeem an otherwise tragic situation; as a way to honor their loved one’s life, passions, and philosophies; and as a way to help others live. Despite such positive reasons to consider organ donation, historically only 50 percent of families asked to consent to organ donation do so (JCAHO, 2004). However, progress has been made both in identifying dying patients who would be potentially suitable donors and in obtaining family consent for donation. Gortmaker and colleagues (1998), examining 1990 data, found that 27 percent of eligible patients had not been identified as potential donors or the family had not been contacted. The study found that 48 percent of the families who were asked to donate their loved one’s organs consented to the donation and that 33 percent of the deceased persons who were potential donors became actual donors. This contrasts with data collected between 1997 and 1999 by Sheehy and colleagues (2003), who found that only 16 percent of eligible patients were not identified as potential donors. Results from the latter study showed that 54 percent of the families who were asked to donate consented and that 42 percent of the potential donors became actual donors. These results suggest substantial improvements over the course of the decade, and consent rates have continued to improve in recent years. The process of organ donation is outlined in Figure 1-3 .

It is difficult to determine the uppermost potential for the number of deceased organ donors. Efforts to date have focused on estimating the number of potential deceased organ donors with neurologic determination of death. However, the potential pool also includes a large number of individuals whose deaths are determined by circulatory criteria, although estimating the number of such potential donors is a complex task (see Chapter 5 ).

Guadagnoli and colleagues (2003) estimated the number of potential deceased organ donors (neurologic determination of death) in the United States in 1998 to be 16,796; the actual number of deceased donors in 1998 was 5,793. This analysis used hospital case-mix data, hospital bed size, medical school affiliation, and status as a trauma center to estimate the

FIGURE 1-3 Process of organ donation.

SOURCE: Adapted from Delmonico et al. (2005). Reprinted with permission from Blackwell Publishing.

number of potential organ donors per hospital and then aggregated the data for each OPO. Because of variations in demographics, the number of eligible hospitals, and other factors, there is wide variation in the number of donations that a single OPO works with each year (in 2004 ranging from 13 to 387 donors) (HRSA and SRTR, 2006).

Sheehy and colleagues (2003) reviewed hospital medical records of deaths submitted by 36 OPOs from 1997 through 1999. Forms were completed for deaths occurring in hospital intensive care units for all individuals who met the neurologic criteria for death and who were 70 years of age or younger. That study estimated that each year in the United States there is a national pool of 10,500 to 13,800 potential donors for whom death is determined by neurologic criteria.

As seen in data from 2002 and 2003 ( Table 1-1 ), the annual pool of eligible donors with neurologic determination of death has numbered approximately 12,000.

In 2003, there were approximately 2.4 million deaths in the United States; of those approximately 1 million deaths were of individuals age 15 to 74 years (NCHS, 2005). Despite a number of coexisting conditions that would preclude organ donation, a comparison of the number of potential eligible donors with the number of actual donors ( Table 1-2 ) shows that there could well be a large number of additional donors if technologies and systems are developed in the future to keep organs viable. This would include an increased focus on donation after circulatory determination of death ( Chapter 5 ). Furthermore, issues regarding organs that are recovered but that are not used have yet to be fully explored ( Chapter 2 ; Delmonico et al., 2005).

TABLE 1-1 Eligible, a Actual, and Additional Donors, 2002 and 2003

TABLE 1-2 Deceased Organ Donors, Potential Versus Actual

Transplant Recipients

Transplant recipients probably know best the real value of increasing the numbers of donated organs: an extended lifetime, improved quality of life, and a chance to resume activities that would have been precluded without a transplant. A 10-year overall increase in life expectancy is reported for kidney transplant recipients compared with the life expectancy

for individuals on transplant waiting lists (Wolfe et al., 1999). Transplant recipients not only experience gains in life expectancy but also enjoy improvements in the quality of their lives. A literature review of 218 independent studies involving approximately 14,750 transplant recipients demonstrated statistically significant improvements in physical functioning, mental health, social functioning, and overall perceptions of quality of life following transplantation (Dew et al., 1997). These improvements are particularly striking when they are contrasted with the pretransplant conditions of patients requiring a transplant, such as the health complications and difficulties associated with long-term dialysis and other medical interventions. Moreover, many individuals face imminent death without a transplant. The lack or inferiority of alternative therapies should be considered when post-transplant quality-of-life data are evaluated (Whiting, 2000).

Other factors may have negative effects on a patient’s quality of life posttransplantation. The financial burden of immunosuppression therapy is thought to play a significant role in patient noncompliance with treatment regimens (Chisholm et al., 2000), which may eventually lead to rejection of the transplant and the need for other therapies or retransplantation. 4 Physical side effects and the psychological and social issues that a patient encounters following a transplantation must also be considered. Improved immunosuppression protocols and the provision of patient education and support services have been recommended as ways to promote positive outcomes and enhance the quality of life for transplant recipients (Galbraith and Hathaway, 2004).

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

Most countries around the globe also face such problems as long waiting lists for organ transplantation and challenges with the allocation of scarce organs. In the last decade, organ donation systems, transplantation programs, and organ exchange organizations have received increasing resources and attention from governmental agencies. In some countries, such as Spain and France, the government itself operates those organizations. In other countries, such as the United Kingdom, the organ donation and allocation efforts remain in control of a nongovernmental body affiliated with the nation’s department of health. Most countries (e.g., Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, and The Netherlands) continue to operate a quasipublic system. Most organ exchange organizations operate on a na-

tional basis. However, the Eurotransplant International Foundation serves Austria, Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, and Slovenia; UK Transplant serves the United Kingdom and Ireland; and Scandiatransplant serves Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden.

Bolstering the infrastructure for organ donation and transplantation has been a major focus in a number of countries. In recent years Spain has been successful in significantly increasing its donor rates. Among the major changes instituted in Spain are an active donor detection program conducted by well-trained transplantation coordinators; an extensive transplant coordination network linking national, regional, and hospital efforts; hospital-level coordinators; increased economic reimbursement for hospitals; professional and public education efforts; systematic death audits conducted in hospitals; and a focus on expanded-criteria donors and on donation after circulatory determination of death (Matesanz, 1998, 2003, 2004).

Cross-country comparisons of donation rates are generally based on the number of donors per million population, a measure that has been criticized because of inconsistent definitions ( Box 1-2 ). According to a report by the Council of Europe, Spain had the highest number of deceased donors per million population (34.6) in 2004, with the United States having 24.1 per million population (Council of Europe, 2005) ( Figure 1-4 ). However, it is difficult to draw accurate or meaningful international comparisons, even for those countries closely aligned geographically, politically, and socioeconomically. A combination of factors influences the effective-

FIGURE 1-4 Numbers of deceased donors per million population for various countries, 2004.

SOURCE: Council of Europe (2005).

ness of a given country’s response to organ donation and transplantation: history; political philosophy; social, legal, and cultural factors; economics; and medical professional practices.

In many countries, explicit consent is needed for organ donation. Countries with opt-in policies include the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Germany, The Netherlands, and New Zealand (Abadie and Gay, 2004).

An alternative approach used by a number of countries is a presumed-consent or an opt-out approach, in which the default policy is that citizens are presumed to be organ donors unless they have expressly opted out of the system ( Chapter 7 ). Opt-out or presumed-consent structures enable either verbal or computer registration of an individual’s objection to organ donation. This is applied with various degrees of strictness. Some countries follow a strict or strong presumed-consent model with little to no role for the family in the organ donation decision-making process. Other countries have a presumed-consent law, but in practice the donor family is involved in the consent process. For example, this is the case in Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Spain, Italy, France, and Sweden (Abadie and Gay, 2004).

Ethical, Social, and Cultural Issues

The ethical issues surrounding transplantation have come under close scrutiny in most countries, and legislation has gradually been introduced to

regulate the transplantation process and to protect donors. Trust in a country’s medical establishment is crucial, however. For example, the relatively low rate of donation in Brazil has been attributed, in part, to distrust of the medical community. Brazil has a large underclass with poor access to health care, and the quality of health care varies greatly. When a new policy of presumed consent was established, Brazilians reported difficulties, even obstacles, in registering as nondonors, further fueling fears that the healthcare system authorities were not to be trusted (McDaniels, 1998). The presumed-consent statute was subsequently repealed.

There are wide differences in the policies and statutes regarding living donation among various countries. For example, Iran has a government-regulated program that compensates and monitors living unrelated kidney donors (Ghods, 2004), whereas many other countries prohibit the exchange of money for transplantable organs.

Cultures vary in the extent to which people are willing to donate their own organs and the organs of their deceased relatives (Sanner et al., 1995). Repeated surveys in Sweden have shown that about 66 percent of the public supports donation, but only 40 percent would consent to removal of a relative’s organs if the wishes of the deceased were not known (Sanner, 1994). A common problem across cultures, however, is that few individuals have informed their families of their wishes, and where donor cards are available, even fewer have signed them (Sanner et al., 1995).

Cultures have different views and traditions about death, and there have been significant debates about the determination of death by neurologic criteria. In Denmark in the 1980s and Germany in the 1990s, many believed that prolonged public debates over the determination of death by neurologic criteria led to declines in organ donation rates (Matesanz, 1998). In Japan, cultural and religious beliefs, particularly those associated with the wholeness of nature and of the human body, have played a role in resistance to the determination of death by neurologic criteria. Under a law adopted in 1997 in Japan, death is pronounced by neurologic criteria only in cases of organ donation and only for those who consented, while they were alive, to organ donation and to the use of brain-based criteria (Veatch, 2000). The next of kin must also give their consent to organ procurement and agree to the pronouncement of death (Fitzgibbons, 1999).

Cultural and religious traditions and beliefs about the treatment of the dead body, beliefs about life after death, and fears of mutilation can also influence decisions about organ donation. The major tenets of nearly all religious traditions, however, are compatible with the practice of organ donation ( Chapter 2 ). Yet, religious beliefs are often invoked in expressing resistance to organ donation, perhaps in part reflecting differences between official religious policies and folk beliefs and practices.

TERMINOLOGY

Because the concepts and processes of organ donation are so closely intertwined with emotional issues of death and dying, it is of utmost importance to the committee, as it is to the transplantation community, that the terminology used to describe and discuss all aspects of organ transplantation be both as accurate and as sensitive as possible. Terminology in this field has had both positive and negative connotations. On the one hand, some terms have played a role in creating or propelling myths, have led to increased misconceptions and fears about organ and tissue donation, or have bred mistrust of the system in general. Other terms have a more positive role in the healing process of a hurting family and in motivating the public to agree to donation. The National Donor Family Council and numerous recipient and donor family organizations have been active in addressing terminology.

Some terms that have seemed descriptive or useful in the past are now being reconsidered in favor of terms that are sensitive to the donor family and that affirm the value of individual human life (see Table S-1 in the Summary ). In the past, the term donor did not require any specificity. Today, as more people choose to become living donors, there is a need to distinguish between living and deceased donors. The term cadaveric has been used in the past but has an impersonal connotation (a dead body intended for dissection). The term deceased donor is preferred because it conveys a more positive message and also denotes that it is a donation by an individual human being.

Although the medical community has used the term harvest , it has agricultural and impersonal connotations for the general public. Similarly, the word retrieval suggests the reclamation of an object and can be quite unpalatable, especially to donor families. The preferred word, recovery , helps people to understand that the removal of a loved one’s organs for transplantation is a respectful surgical procedure. The word receive might even be more appropriate because it highlights the gift relationship. Even though the term procure is widely used, it is also receiving close scrutiny. This term, similar to retrieve , has an impersonal connotation that does not fit with the intensely personal and emotional decisions regarding the end of a human life.

The term life support can be a confusing term for a family who has been notified that their loved one is dead. When death occurs, there is no support that can make the individual alive again. After the declaration of death by neurologic criteria, if there is consent for organ donation, the organs may be perfused with oxygen for several hours through mechanical support. Mechanical support and ventilated support are appropriate terms for the support given a deceased person’s organs in the event of organ donation.

Further confusing to families in times of crisis are the terms brain death and cardiac death . To some, these terms imply that certain organs have died but do not convey that this is a final determination of death. In order to avoid such confusions, the committee recommends use of the word death , adding either circulatory determination of death or neurologic determination of death where it is important to have greater specificity. Instead of donation after cardiac death and donation after brain death , the committee believes it would be clearer to use the phrases donation after circulatory determination of death (DCDD) and donation after neurologic determination of death (DNDD). Even though these phrases are more cumbersome, they better convey the finality of death and provide additional information on how that death was declared.

As terms continue to evolve, the committee urges all who are involved in organ transplantation to use words and phrases that clarify rather than mystify the process of organ transplantation and that affirm the value of each individual human life.

It is also important at the outset of this report to clarify the measures of deceased donation that the committee used. The consent rate is defined as the number of patients for whom consent is granted for organ donation (permission may be granted by the individual donor while he or she is alive or by the donor’s family after death) per the total number of patients eligible to be donors. The donation rate (also termed the conversion rate ) is the number of actual donors (i.e., the organs are removed for transplantation) per the total number of individuals eligible to be donors. The consent rate can be slightly higher than the donation (or conversion) rate, since after consent is obtained it might be determined that the organs are not suitable for recovery. Both of these measures have focused on donation after neurologic determination of death. As the measures are currently defined, the denominator for each excludes patients who are eligible for donation after circulatory determination of death. The implications of this approach are further discussed in Chapter 5 .

U.S. EFFORTS TO INCREASE ORGAN DONATION

Current efforts in the United States to increase rates of organ donation involve the collective work of numerous governmental and private-sector organizations. This section provides a brief overview of ongoing efforts. The chapters that follow provide further insights into the many parties that enable, facilitate, and promote organ donation.

HRSA is a major federal funder of research and initiatives to increase organ donation rates in the United States. HRSA’s Division of Transplantation is responsible for administering the federal contracts for OPTN and for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, which collects and analyzes

data on solid-organ transplant recipients. In addition to this operational role, HRSA works to increase organ donation rates through three major avenues: an extramural grants program, which funds model interventions, including social and behavioral, media-based, and clinical interventions ( Appendix E ); the Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaboratives, an ongoing initiative that emphasizes quality improvement and that focuses on improving hospital and OPO collaborations and encouraging best practices in organ donation ( Chapter 4 ); and additional Gift of Life initiatives, including efforts in workplaces, schools, and driver’s education centers, as well as model donor card, donor registry, and similar projects ( Chapter 6 ). In recent years, the level of funding for HRSA’s Division of Transplantation has decreased, with a significant reduction encountered in fiscal year 2006 ( Table 1-3 ). The potential impact of these budget reductions on organ donation efforts is of concern.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds grants for organ transplantation research that primarily focus on biomedical studies of improvements in surgical techniques for transplantation, understanding immune-related processes, and improving graft survival. Additionally, and to a more limited extent, NIH funds have been applied to behavioral research on organ donation. In fiscal year 2005, the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) supported research grants primarily aimed at raising awareness of organ donation in minority communities and improving the role of healthcare professionals in encouraging donation. In addition to these grants, NIDDK and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities support the National Minority Organ and Tissue Transplant Education Program ( Chapter 6 ).

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has the regulatory authority to certify OPOs and hospitals that perform transplantations

TABLE 1-3 Funding History, HRSA Division of Transplantation

for participation in Medicare. CMS administers the End-Stage Renal Disease Program and is active in ensuring quality improvements in transplantation programs.

States play an important role in promoting organ donation through legislative action (e.g., anatomical gift acts and the criteria used for the determination of death), the funding and implementation of organ donor registries ( Chapter 6 ), drivers’ license registration options for organ donation, and other programs (Gilmore et al., 2001). Some states have mandated that information on organ donation be provided as a part of high school driver’s education curriculum.

One of the key responsibilities of OPOs is “educating the public about the critical need for organ donation” (UNOS, 2006). OPOs work closely with donor families, transplant recipients, and others in a range of donation efforts.

In addition, numerous voluntary health organizations focus on public education about organ donation and the provision of support for donor families, living donors, and transplant recipients. For example, the Coalition on Donation is a not-for-profit alliance of national organizations and local coalitions across the United States that have joined forces to educate the public about organ, eye, and tissue donation (Coalition on Donation, 2004). The National Kidney Foundation and similar organizations that focus on relevant diseases and organ systems also support research and efforts for public and professional education. Other organizations, such as the National Donor Family Council, support the needs of donor families, assist the healthcare professionals who work most closely with these families, and raise public awareness.

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations has promoted organ donation efforts by incorporating policies and procedures on the identification and referral of potential donors into hospital accreditation standards.

Professional organizations, including the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations, the American Society of Transplantation, the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, and the Organization for Transplant Professionals, are active in professional education and also work to promote organ donation through advocacy and public education efforts.

THE ECONOMIC VALUE OF INCREASING THE ORGAN SUPPLY

Numerous clinical studies have documented the benefit to patients of organ transplantation in terms of life expectancy and quality of life. Increasing the rates of organ donation would provide these benefits to more patients and would reduce the waiting time for many transplant recipient candidates. Policies that increase the organ supply also entail monetary and

nonmonetary costs. In deciding whether to pursue these policies, it is helpful to know whether the benefits to patients in terms of life expectancy and quality of life outweigh the costs and whether the cost per unit of health gained is low (or, alternatively, the “value” is high) compared with the value of other policies that are implemented to improve health.

The literature on the cost-effectiveness of transplantation provides indirect evidence of the economic value of increasing the organ supply. Kidney transplantation has been estimated to be highly cost-effective compared with the cost of dialysis (Winkelmayer et al., 2002) and is probably cost saving (Matas and Schnitzler, 2003; Whiting et al., 2004). Estimates of the cost-effectiveness of nonrenal transplantation are more variable (Ramsey et al., 1995; Cope et al., 2001; Sagmeister et al., 2002; Longworth et al., 2003; Ouwens et al., 2003). Most of these studies find that the cost per life year gained is less than commonly cited estimates of the value of a life year (Richardson, 2003), although cost data are often incomplete and, for studies based on transplants occurring in European countries, may not be generalizable to the United States. Most of these studies find that the cost per year of life gained is less than $100,000, although the data required for cost-effectiveness studies of nonrenal transplantation are often incomplete.

Several studies have directly addressed the economic value of increasing organ donation. Matas and Schnitzler (2003) estimate that every additional kidney donation from a living donor reduces total spending by more than $90,000. Mendeloff and colleagues (2004) used published estimates of the costs of and quality-adjusted life years gained from kidney, liver, and heart transplants to calculate the monetary value to society of a deceased organ donor, assuming that each donation results in 1.55 kidney transplants, 0.37 heart transplants, and 0.76 liver transplants. They estimated that a deceased organ donor is associated with a gain to transplant recipients of 13 quality-adjusted life years (summed across the transplanted organs) and a $200,000 increase in healthcare spending, although that figure is based on a conservative value of the cost savings from kidney transplantation (Schnitzler et al., 2005a). If it is assumed that a life year is worth $100,000, their “central” estimate is that each donor is worth $1,086,000 to society, or $1,800,000 when their best-case estimates of cost savings and life years gained are used.

Interpretation of the findings of these studies requires one note of caution, however, in that they are based on historical outcomes data, and the patients who would gain access to transplantation as a result of an increased organ supply may differ systematically from patients who currently receive a transplant. For example, in the case of liver transplantation, in which organs are allocated according to a “sickest first” priority rule, an increased supply would allow physicians to perform transplantations for healthier patients, who, under current supply constraints, must wait until

their health declines before they reach the top of the waiting list. Because the cost-effectiveness of transplantation varies widely by age group (Jassal et al., 2003, Schnitzler et al., 2003), primary diagnosis (Longworth et al., 2003; Groen et al., 2004), and other factors, knowledge of the characteristics of the patients who will receive additional organs is important for estimation of the impact of efforts to increase the organ supply. Schnitzler and colleagues (2005b) have made progress on this front by measuring the life years gained from transplantation on the basis of the pretransplantation death rates of patients near the top of each organ-specific waiting list. They have found that an additional deceased organ donor yields a gain of 30.8 life years for these patients (summed across the transplanted organs), assuming that each donation results in 1.4 kidney transplants, 0.80 liver transplants, 0.20 lung transplants, and 0.30 heart transplants. For the case of livers, an analysis by Gibbons and colleagues (2003) suggests that urgent patients (status 1, under the old classification system) derive a greater benefit from transplantation than nonurgent patients.

An increase in the organ supply will increase the number of patients who receive transplants, but even when the number of transplantations is held fixed, an increase in the supply will reduce the waiting times for patients who would eventually receive a transplant anyway. A number of studies indicate that longer waiting times are associated with worse outcomes (Everhart et al., 1997; Howard, 2000; Meier-Kriesche and Kaplan, 2002). It may be possible, however, to provide transplants to patients too early in the course of their disease, in the sense that the benefit of the reduced waiting time is outweighed by the immediate risk of postoperative mortality (Kim and Dickson, 2000; Alagoz et al., 2004).

A number of secondary effects of increasing the organ supply should be considered when the value of increasing donation rates is assessed, although these have not been well documented. If the organ supply increases, providers may place more patients on the waiting list, particularly those who are less likely to benefit from transplantation. Physicians may also become reluctant to use low-quality organs (Howard, 2002).

In evaluating the payoffs from increasing the organ supply, it is important to remember that cost-effectiveness studies are approximations and that some nonmonetary costs and benefits are not easily quantified. Moreover, policies that are implemented to increase the supply of organs must be compared with other opportunities to improve the length and quality of life through public policy. In a country in which so many people have limited access to effective health care, many unexploited opportunities to obtain quality-adjusted life years at a low cost probably exist. Nevertheless, with these caveats in mind, the committee concludes that the available data suggest that well-designed policies to increase deceased and living organ donation are potentially cost-effective and even cost saving.

EMPHASIS ON PREVENTION

In considering the total picture of organ transplantation, it is helpful to step back and examine each of the points at which interventions and initiatives could make a difference in equalizing the supply and the demand for organs for transplantation. The focus of the committee’s task—and thus, the focus of this report—is on increasing the supply of donated organs. However, reducing the demand for organ transplantation would be even more effective, because it would mean that greater numbers of healthier individuals have not reached the point of needing an organ transplant. In general, transplantation should be seen as a rescue technology; it is an invaluable resource and option when it is needed, but prevention measures leading to improved health status are the first line of defense to avoid, where possible, the need for transplantation. The committee recognizes that not all causes of organ deterioration and failure can be prevented; however, for those cases in which prevention could make a difference, it is important to begin to implement preventive interventions at the earliest time possible and to minimize the rejection of the transplanted organ(s).

Transplantation occurs at the end of a continuum of symptoms, diagnoses, treatments, and interventions. The prevention framework of public health, with insights from the Haddon matrix (a model originally developed to address injury prevention), provides a context for considering the numerous points at which interventions could improve health status and reduce the demand for transplantation ( Table 1-4 ).

If transplantation is considered the event, then pre-event measures and interventions could focus on efforts to prevent the onset of disease or minimize its outcomes so that it will not reach the point of requiring transplantation. Examples of pre-event interventions include education on healthy lifestyles and screenings for stroke, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Event interventions focus on high-quality care for the patient during transplantation and the provision of support to the patient and family so that they understand the transplantation procedures and the necessity for follow-up. In the third phase—the post-event phase—the focus is on restoring lost function and former quality of life, with particular attention to access to immunosuppressive therapies and ensuring that the donated and transplanted organ is fully maintained so that retransplantation is not necessary.

The goal, of course, is to minimize the need for organ transplantation by preventing the underlying disease risk factors that lead to organ deterioration and failure. Although not all the medical conditions necessitating organ transplantation can be prevented, preventive interventions and the treatment of contributory diseases as early as possible have the potential to reduce significantly the demand for organ transplantation.

TABLE 1-4 Organ Transplantation Prevention Matrix

ON THE HORIZON

A variety of technological advances in development might improve organ viability or diminish the need for living or deceased organ donation. Ongoing research on organ preservation and organ culture is examining methods to improve organ function and viability. Nanotechnology offers the potential for the insertion of implantable devices that would restore organ function or serve as an organ replacement. For example, mechanical devices such as the left ventricular assist device currently serve as a bridge for those waiting for a heart transplant, but refinements or reengineering

may permit them to be used as a long-term alternative to or replacement for transplantation. Xenotransplantation (transplantation of an organ between two different species) has been an ongoing area of research and has some current clinical applications (e.g., heart valve transplants from pigs). However, the use of organs or tissues from other species continues to encounter biological barriers regarding immunosuppression, organ rejection, and disease transmission as well as the psychosocial concerns of some individuals regarding the use of organs from animals. Stem cell research offers the promise of repairing or restoring organ function in the near future.

Other technologic developments are raising new ethical questions. Organs such as the face and the ovary have been transplanted with some success and raise ethical concerns about identity and reproductive lineage. It is too early to determine if and how public attitudes regarding these developments will impact rates of organ donation.

Until the time that preventive measures diminish the need for transplantation or alternative approaches offer an effective option, numerous families, healthcare and transplantation professionals, and many others continue to make extraordinary efforts each day to ensure that organs are donated and are successfully transplanted with the goal of improving the quality of life and the length of life for transplant recipients.

OVERVIEW OF THIS REPORT

The large gap between the supply and the demand for solid organs has prompted the need to carefully examine a variety of policy, organizational, and institutional changes that might be made to increase rates of organ donation. As discussed in Chapter 2 and throughout the report, a variety of factors influence an individual’s or a family’s decision making regarding organ donation.

This report examines a range of proposals for increasing deceased organ donation ( Table 1-5 ) and briefly discusses some ethical concerns raised by living donation. The committee’s framework—perspectives and principles—for considering these proposals is provided in Chapter 3 . The subsequent chapters examine changes in the organization, processes, and interactions of hospitals and OPOs ( Chapter 4 ); expanding the pool of potential organ donors through donation after circulatory determination of death ( Chapter 5 ); and individual decision making, public education, and research ( Chapter 6 ). Opt-out policies, particularly presumed consent, are discussed in Chapter 7 , and Chapter 8 focuses on financial and nonfinancial incentives. Living donation is discussed in Chapter 9 , and the report concludes in Chapter 10 with a synopsis of the opportunities for action to increase organ donation.

TABLE 1-5 Several Approaches to Increasing Deceased Organ Donation, Issues Examined in This Report

Abadie A, Gay S. 2004. The Impact of Presumed Consent Legislation on Cadaveric Organ Donation: A Cross Country Study. [Online]. Available: http://ksghome.harvard.edu/~aabadie/pconsent.pdf [accessed March 15, 2006].

Alagoz A, Maillart LM, Schaefer AJ, Roberts M. 2004. The optimal timing of living-donor liver transplantation. Management Science 50(10):1420–1430.

Bernat JS. 2005. The concept and practice of brain death. Progress in Brain Research 150: 369–379.

Chisholm MA, Vollenweider LJ, Mulloy LL, Jagadeesan M, Wynn JJ, Rogers HE, Wade WE, DiPiro JT. 2000. Renal transplant patient compliance with free immunosuppressive medications. Transplantation 70(8):1240–1244.

Coalition on Donation. 2004. Who We Are. [Online]. Available: http://www.shareyourlife.org/contact_who.html [accessed August 9, 2005].

Cope JT, Kaza AK, Reade CC, Shockey KS, Kern JA, Tribble CG, Kron IL. 2001. A cost comparison of heart transplantation versus alternative operations for cardiomyopathy. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 72(4):1298–1305.

Council of Europe. 2005. International figures on organ donation and transplantation. Transplant Newsletter 10(1).

Delmonico FL, Sheehy E, Marks WH, Baliga P, McGowan JJ, Magee JC. 2005. Organ donation and utilization in the United States, 2004. American Journal of Transplantation 5(4 Pt 2):862–873.

DeVita MA, Snyder J, Grenvik A. 1993. History of organ donation by patients with cardiac death. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 3(2):113–129.

Dew MA, Switzer GE, Goycoolea JM, Allen AS, DiMartini A, Kormos RL, Griffith BP. 1997. Does transplantation produce quality of life benefits? A quantitative analysis of the literature. Transplantation 64(9):1261–1273.

DHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services), Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. 2000. Analysis of State Actions Regarding Donor Registries. Prepared by The Lewin Group, Inc. [Online]. Available: http://www.organdonor.gov/aspehealth.html [accessed April 3, 2006].

DHHS, Office of the Inspector General. 2003. Variation in Organ Donation Among Transplant Centers. OEI-01-02-00210. Washington, DC: DHHS.

Eggers PW. 2000. Medicare’s end stage renal disease program. Health Care Financing Review 22(1):55–60.

Everhart JE, Lombardero M, Detre KM, Zetterman RK, Wiesner RH, Lake JR, Hoofnagle JH. 1997. Increased waiting time for liver transplantation results in higher mortality. Transplantation 64(9):1300–1306.

Fitzgibbons SR. 1999. Cadaveric organ donation and consent: A comparative analysis of the United States, Japan, Singapore, and China. ILSA Journal of International and Comparative Law 6:73.

Galbraith CA, Hathaway D. 2004. Long-term effects of transplantation on quality of life. Transplantation 77(9):S84–S87.

Ghods AJ. 2004. Changing ethics in renal transplantation: Presentation of Iran model. Transplantation Proceedings 36(1):11–13.

Gibbons RD, Duan N, Meltzer D, Pope A, Penhoet E, Dubler N, Francis C, Gill B, Guinan E, Henderson M, Ildstad S, King PA, Martinez-Maldonado M, Mclain GE, Murray J, Nelkin D, Spellman MW, Pitluck S. 2003. Waiting for organ transplantation: Results of an analysis by an Institute of Medicine committee. Biostatistics 4:207–222.

Gilmore L, Matthews T, McBride VA. 2001. State Strategies for Organ and Tissue Donation: A Resource Guide for Public Officials. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration.

Gortmaker SL, Beasley CL, Sheehy E, Lucas BA, Brigham LE, Grenvik A, Patterson RH, Garrison N, McNamara P, Evanisko MJ. 1998. Improving the request process to increase family consent for organ donation. Journal of Transplant Coordination 8(4): 210–217.

Groen H, van der Bij W, Koeter GH, TenVergert EM. 2004. Cost-effectiveness of lung transplantation in relation to type of end-stage pulmonary disease. American Journal of Transplantation 4(7):1155–1162.

Guadagnoli, E, Christiansen CL, Beasley CL. 2003. Potential organ-donor supply and efficiency of organ procurement organizations. Health Care Financing Review 24(4): 101–110.

Guidelines for the determination of death. 1981. Report of the medical consultants on the diagnosis of death to the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Journal of the American Medical Association 246(19):2184–2186.

Halloran PF, Gourishankar S. 2001. Historical overview of pharmacology and immunosuppression. In: Norman DJ, Turka LA, eds. Primer on Transplantation , 2nd ed. Mt. Laurel, NJ: American Society of Transplantation. Pp. 73–75.

Howard DH. 2000. The impact of waiting time on liver transplant outcomes. Health Services Research 35(5):1117–1134.

Howard DH. 2002. Why do transplant surgeons turn down organs? A model of the accept/ reject decision. Journal of Health Economics 21(6):931–1094.

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration) and SRTR (Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients). 2005. 2004 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data 1994–2003 . [Online]. Available: http://www.optn.org/AR2004/default.htm [accessed March 30, 2006].

HRSA and SRTR. 2006. 2005 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data 1995–2004 . [Online]. Available: http://www.optn.org/AR2005/default.htm [accessed March 3, 2006].

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1997. Non-Heart-Beating Organ Transplantation: Medical and Ethical Issues in Procurement. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1999. Organ Procurement and Transplantation: Assessing Current Policies and the Potential Impact of the DHHS Final Rule. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2000. Non-Heart-Beating Organ Transplantation. Practice and Protocols. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jassal SV, Krahn MD, Naglie G, Zaltzman JS, Roscoe JM, Cole EH, Redelmeier DA. 2003. Kidney transplantation in the elderly: A decision analysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 14(1):187–196.

JCAHO (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations). 2004. Health Care at the Crossroads: Strategies for Narrowing the Organ Donation Gap and Protecting Patients. [Online]. Available: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/E4E7DD3F-3FDF-4ACC-B69E-AEF3A1743AB0/0/organ_donation_white_paper.pdf [accessed March 30, 2006].