The Bleak Prescience of Richard Wright

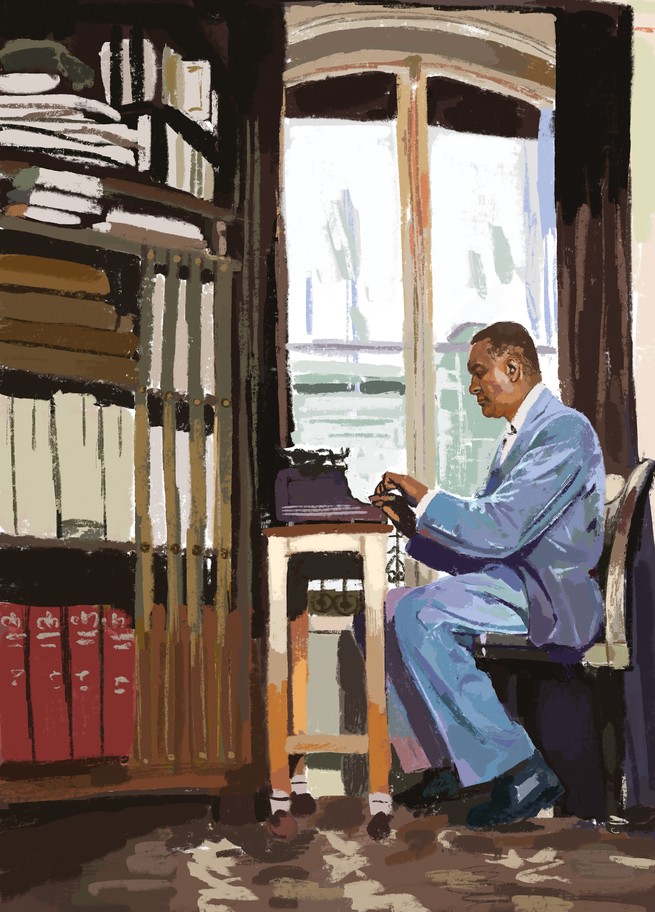

A previously unpublished novel invites a reassessment of a writer criticized for his doctrinaire pessimism about race in America.

This article was published online on May 7, 2021.

R ichard Wright , the father figure of African American literature, both nurtured and was rejected by his two most conspicuous heirs, Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin. Wright, who took Ellison under his wing in New York in the late 1930s, told his acolyte to stop copying him, that he was mimicking, not cultivating his own style. Ellison responded that he was trying to learn to write well by imitating his mentor. That was when they were close. Baldwin, too, started out as a pupil and an admirer who saw Wright poised to be the greatest Black writer in the United States.

Though it happened slowly, by 1941, Ellison betrayed signs of feeling that Wright, affiliated off and on with the Communist Party, wrote fiction that was too ideological and not sensitive enough to nuance: Wright wanted to testify to the monstrosities of white supremacy, rather than the power of Black resilience. Ellison grew committed to the poetry of American democracy, despite how badly it was sullied; he swore by the virtues of individualism. Calling Wright “Poor Richard,” Baldwin joined Ellison in lamenting their mentor’s failure to see the beauty of Black people. The two of them never ceased to love Wright’s prose, but they came to reject his perspective.

From the August 1944 issue: Richard Wright’s “I Tried to Be a Communist”

I admit I’ve been inclined to share their verdict, based on Wright’s first novel, Native Son , published in 1940 , which I read again and again in classes before and during college. I’ve parroted the notes I took in lectures, and I’ve taught a version of those lectures myself: Bigger Thomas was a protagonist stripped of any redeeming qualities, so distorted by the conditions of racism that he became an avatar more than a character, and an unsettling representation of Blackness.

My assessment of Wright has begun to shift over the past couple of years. I’ve read 12 Million Black Voices (1941)—his reflections on the Great Migration, accompanied by Farm Security Administration photographs taken during the Depression—and been struck by his broad sympathy. And I’ve reread Black Boy (1945), a memoir I hadn’t touched since my final year of high school in the Northeast, in a writing seminar led by a teacher born, like me, in Birmingham, Alabama. Wright reached for the very core of the human condition in his portrait of growing up destitute in the Deep South during the early 20th century, and then making his way north: abundance everywhere and terrible hunger, tragedy mixed with the quotidian in the most disorienting ways. The experience he evoked might not have been every Black life, but it was indeed a part of Black life. In Mississippi, the land could swallow you whole. In Chicago, a rat might bite you, because after all, you were made to live in slums no different from rattraps. Wright was showing us something true, if not absolute—how, with the plantation breathing at your back and deferred dreams before you, tragedy happened.

Now that I’ve read The Man Who Lived Underground — a previously unpublished novel held in the Wright archives , also written in the early 1940s—I’m even more convinced that Wright deserves to be looked at with fresh eyes. At first, I texted a friend, “This novel is clearly a direct model for Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man .” My friend wrote back, “That’s why he told Ellison to stop copying him!” Wright’s protagonist is a Black man who is falsely accused of a double homicide and brutalized by the police before escaping into a sewer. Ellison’s protagonist is also a Black man who eventually retreats into a sewer, on an identity quest that has been thwarted aboveground. Yet I quickly discovered that Wright was mapping an unexpected journey.

Read: An arty but superficial take on ‘ Native Son’

Though Native Son had been a best seller, Harper rejected The Man Who Lived Underground , its immediate successor. Readers’ comments in the archives suggest that the editors might have been deterred by the “unbearable” police violence and an imbalance between allegory and graphic detail. The book opens with a harrowing encounter between decent, respectable Fred Daniels, the protagonist, and three police officers. Fred is subjected to torture so extreme that he’s left barely conscious. He loses track of everything in the horror of the moment. His identity disappears, time is drained of meaning, he forgets his pregnant wife and grows unsure about his innocence. The unheimlich , Freud’s idea of the unfamiliar familiar, is a constant presence for Wright: Nothing makes sense, and yet he and we know that this is the way the world is. And then, almost as if in a dream, Fred realizes that the officer guarding him has briefly walked away, and “a vague gathering of all the forces of his body urged him to escape.” Like a disoriented, curious child, he gravitates toward a “gaping manhole.”

Recommended Reading

Stories of Slavery, From Those Who Survived It

Am I What You’re Looking For?

The Origins of Office Speak

The sewer provides a nightmarishly sensual experience. What sounds like a holler might be a skidding car. The slosh of water turns to sludge; a baby passes by him, dead and flushed away. Ellison’s invisible man escapes into an Emersonian isolationism—a reckoning with himself underground. Wright scripts a surreal reencounter with the world as seen through discovered cracks and doors that reveal hidden interiors: In his subterranean wandering, Fred comes upon the basement of a Black church, drawn to it by singing that he finds at once “sonorous and magnificent in its expression of melancholy renunciation” and infuriating in its guilty “whimpering.” He happens on the safe room of a real-estate office, and ends up complicit in a theft that results in another man’s punishment. He finds himself in a coal bin, saved from being scooped up by a worker only because the exhausted old man works in the dark, never turning on the lights.

Viewed from below, the social world, the economy—all manner of ordered things—are clearly absurd. Reason eludes Fred, and empathy flows in at the vision of humanity as “children, sleeping in their living.” After all, what really matters? This isn’t the doctrinal Wright, warning us of the disasters that capitalism creates. This is an unmooring Wright, pushing us past the edge of social analysis and into madness. Perhaps this turn, from leftist literary naturalism to a morbid unraveling of the self, is what most disturbed the Harper editors.

It’s impossible to read Wright’s novel without thinking of this 21st-century moment, when we urgently assert, “Black lives matter.” We live with cycles of repeated violence; the terror of Black innocents being killed is all around us and in our consciousness. Starting in the 1940s, Ellison and Baldwin criticized Wright for his insistence on dramatizing this ineluctable subjugation; they saw Wright himself as submitting, in the process, to Black oppression in America. They believed, each in his own fashion, that Black literature ought to capture hope, possibility, beauty, and endurance. Transcendence and, more important, transformation were possible until they weren’t. Now the tragic absurdity of Fred’s life seems all too familiar. We see it on our screens regularly: the snuff films of white supremacy. Perhaps we have too readily judged Wright’s bearing of witness to be reductively stark and fatalistic. What he observed is still happening, despite all those generations of unyielding hope.

Critics will no doubt liken The Man Who Lived Underground to Kafka, Dostoyevsky, and Sartre. And the analogies are there in Fred’s drive to “assert himself,” to act in the face of “death-like” existence. But the novel is also a Protestant work, as much about God as it is about Black people, as Wright himself explains in an accompanying essay about the novel’s origins titled “Memories of My Grandmother.” In a world beyond understanding and reason, his Seventh-day Adventist grandmother had a religion that imposed meaning on the incomprehensibility of existence. She believed, in accordance with Church doctrine, that right and wrong were starkly distinguished. Strangeness was not to be explored, but simply judged. Guilt preceded assessment: Humans were guilty, and only holiness could save them. In its own way, this fierce Black Protestantism gave psychic refuge to believers but also recommended surrender to the cruelty of the world. In Fred’s odyssey, which leads him back aboveground to confess to the crime he didn’t commit, Wright has him careen from rage at the pervasive burden of guilt to an embrace of it.

As I read, I was reminded of Lorraine Hansberry’s thoughts about Wright’s contested literary status. Like her fellow writers, she valued debate over how best to use literature as a tool of social criticism, but she felt that Baldwin’s attack on Wright was too harsh—as if Wright had to plummet in order for his own star to rise. She disliked the pleasure that white critics took in this literary patricide. In her view, very few American writers could match Wright’s skill and style.

Wright deserves sensitive reconsideration, especially now that so many of us have been proved naive in our belief that an honest rendering of Black people might lead to recognition of our existence in the universality of humanity. When Wright became an expatriate, in the late ’40s, he did not turn his back on America. He found a vantage point that allowed him to understand better what actually went on in a country where Black people “are accused and branded and treated as though they are guilty of something,” as he wrote in his essay. Baldwin, who also moved to France, eventually came to a similar conclusion that with distance from the U.S. came newly clear-eyed intimacy.

I write, again and again, that things have changed for Black Americans, as unjust as the world remains. I say that Black people have displayed remarkable endurance and transformed so much. And yet, I wonder. When the novelist and poet Margaret Walker looked at Richard Wright, a man she loved completely, she worried that he capitulated too easily to the violence. But he, a child of the Black Belt, was up close to it in a way that Walker, a Birmingham-born preacher’s daughter, simply wasn’t. Nor am I. I have visited a squatter’s residence, a crack house, a federal prison, but I haven’t lived in any of them. I have been falsely accused and unfairly judged, but never beaten senseless in the process.

Wright tells an old story that still lives. His Fred carries the name of our most famous Black fugitive, the abolitionist writer Frederick Douglass, and he travels underground in ways more reminiscent of the Underground Railroad than of Dostoyevsky. He finds himself encountering the world, unfiltered by established terms of order, and acquires a tenderness for all people. In the end, his Black existence presents a particular window and a universal predicament—and a reminder: Surrounded by ghastly forces every day, we destroy life with our many idolatries and illusions.

This article appears in the June 2021 print edition with the headline “What Richard Wright Knew.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

- Intellectual Affairs

Notes From the Underground

By Scott McLemee

You have / 5 articles left. Sign up for a free account or log in.

In the sort of coincidence that makes a columnist’s work much easier, the Library of America published Richard Wright’s The Man Who Lived Underground: A Novel on April 20 -- the same day, as it turned out, that a jury in Minneapolis convicted a police officer of murdering George Floyd last year.

It has taken almost eight decades for Wright’s book finally to appear in print. In an evaluation of the manuscript for Wright’s publisher in 1942, one reader described the opening pages of scenes of police brutality, depicted blow by blow, as “unbearable” -- and to revise the text so that it could appear in a literary anthology a couple of years later, Wright cut it by about half. This rendered his short novel into a long short story, with the narrative beginning only after the central character escapes from custody.

The truncated version, which also appeared in a posthumous collection of his short fiction, has been the subject of a substantial body of academic criticism, with the echoes of Dostoevsky and the influence of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (not to mention the possible allusions to Plato’s myth of the cave) all duly considered. But largely missing has been a sense of the brutal context of the subsequent narrative's sometimes dreamlike quality. Reading the work in the form Wright originally intended it to go into the world means facing not only the “unbearable” passages but also the absolute certainly that they were, if anything, understated.

Having now given topicality its due, I’ll venture a guess as to its place in Wright’s work. The Man Who Lived Underground would be among his three or four best books, even if it did not also include another text hitherto only available to scholars consulting the Wright papers at Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library: an essay with the unassuming title “Memories of My Grandmother,” which is certain to be one of Wright’s most discussed writings for at least the next several years.

Toru Kiuchi and Yoshinobu Hakutani’s useful Richard Wright: A Documented Chronology 1908-1960 indicates that he began writing The Man Who Lived Underground in the summer of 1941, a little over a year after his first published novel, Native Son , became an instant best seller. The inspiration came from an article in True Detective , a pulp magazine, about a man who “[got] into various stores in Hollywood by digging a tunnel connecting to the basements and back of the shops.” The culprit was a white man. But the report of his deeds somehow resonated with Wright’s own very complicated feelings about race and religion in African American life in general, and in his grandmother’s life in particular.

When we meet Wright’s underground man at the beginning of the novel, he is a sort of everyman figure called Fred Daniels, which is about as deliberately prosaic a name as you can get. A law-abiding and churchgoing guy, Daniels leaves work on an early Saturday evening with the week’s pay in hand and prepares to go back to the wife who is waiting for him at home -- a day or two away from delivering their firstborn. But he has hardly had time to tuck the dollar bills in his pocket before he hears a voice from inside a cop car: “Come here, boy.”

Daniels is picked up by police for no reason they care to explain, at least not until after they’ve taunted and humiliated him on the ride to the station. Once set up in an interrogation room, they beat Daniels senseless while accusing him of a double murder. Every detail is narrated from his point of view, which shifts from bewilderment and disbelief into an almost dissociated state. Nothing he says has any effect except to bring more wrath down on him. The police offer to let Daniels see his wife if he’ll just sign a statement. The whole sequence is disorienting in part from the reader’s helpless certainty that: a) signing a confession is absolutely the worst action he could take, yet b) refusing would mean the very real possibility of dying in custody.

Wright was testing the outer limits of what the white novel-reading public would have found imaginable at the time. The 21st-century reader has no excuse to be so blinkered, given the documentation of police station torture in Chicago or what Derek Chauvin did not mind doing to George Floyd in public while a video camera recorded it. That said, one aspect of the opening that evoked a surprisingly intense reader response in me was the repeated address to Daniels, a man of about 30, as “boy” -- a usage loaded with more menace and intention to degrade than it seems one word could express.

Seizing an opportune moment , Daniels gets away from the police long enough to open a manhole and descend into the foul gloom of the sewer system. He finds his way around with a few matches and encounters “a huge rat, wet and coated with slime, blinking beady eyes and showing tiny fangs … its forepaws clawing for a hold on the slick brick.” Daniels has no intention of staying any longer than necessary but also no way to know when returning to the surface will be an option.

He finds his way around by touch ("The wall ended, and his fingers toyed experimentally in space, like the antennae of an insect”) and moves toward sounds of what turns out to be an African American church service, held in a basement and visible through a grate. It is the first of several locations he is able to view, and sometimes to enter, from his place in hiding, where he sets up a makeshift “home” from bits and pieces of what he finds during his exploration.

The narrative of his itinerary is both concrete (full of all-too-tangible details) and phantasmagoric, and at some point while reading, I found the phrase “naturalistic surrealism” coming to mind. It is more or less a contradiction in terms. In naturalistic fiction, characters and actions are depicted within, and as products of, an environment; social conditions and physiological drives are never out of view. With surrealism, the landscape is entirely interior; words and deeds obey no logic but that of a dream or fantasy. Wright’s Native Son is a landmark work of American naturalist fiction, and the rat Fred Daniels sees will remind any reader of the earlier novel of its opening scene in the tenement apartment where Bigger Thomas lives. And the narrative arcs for both Thomas and Daniels are defined by as naturalistic a motive as anyone can be: the drive to self-preservation. (Also bearing note: the comparison of Daniels's fingers to antennae.)

But with The Man Who Lived Underground , a nightmarish tone is set from the moment Fred Daniels finds himself overpowered and helpless to respond to accusations of guilt for a crime he doesn’t even know about -- much the situation facing the central figure in Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial . (Spoiler alert: the parallels do not end there.) But this is less a matter of literary influence than of Wright burrowing in to explore the Kafkaesque circumstance of living in his own skin .

Reading “Memories of My Grandmother” makes explicit that any resemblance between Wright’s novel and surrealism is absolutely inevitable. “Surrealism,” Wright explains, “is a manner of looking at the world, a way of feeling and thinking, a method of discovering relationships between things; it is a phase of the creative process.” Nor was he importing it: “The manner in which Negro blues songs juxtapose unrelated images was the advent of surrealism on the American scene.” Wright returned to this line of thought in later work, but this early formulation of the idea is particularly forceful, as if the ideas are taking shape as he writes:

"A black woman, singing the blues, will describe a rainy day, then, suddenly to the same tune and tempo, she will croon of a red pair of shoes; then, without any logical or causal connection, she will sing of how blue and lowdown she feels; the next verse may deal with a horrible murder, the next with a theft, the next with tender love, and so on. This tendency of freely juxtaposing totally unrelated images and symbols and then tying them into some overall concept, mood, feeling, is a trait of Negro thinking and feeling that has always fascinated me. I think it was this part of my grandmother’s personality that fascinated me more than anything else. The ability to tie the many floating items of her environment together into one meaningful whole was the function of her religious attitude. It seemed indicative of a certain strange need on her part.”

Connecting Salvador Dalí and his Seventh-Day Adventist grandmother involves quite a leap, but here Wright is feeling his way into strange depths. “Eternity was so real to her,” he recalls, “that human life had an air of unreality … [Her] never-blinking eyes … seemed to be contemplating human frailty from some invulnerable position outside time and space.” They fought -- quite a bit, it sounds like -- across an enormous psychological distance: “She hovered somewhere off in space so distantly that things that strike us as having no relationship were merged into an organic blur for her, and things that were united for us were either separate or nonexistent for her.”

Pious as his grandmother was, she would have resented Wright's implication that she had anything in common with singers of the blues or paintings in which, e.g., watches melted. And some of his reflections suggest that the author himself only made the connections after writing The Man Who Lived Underground . He writes,

“First, I noticed that Fred Daniels was withdrawn from the world; second, that he suffered a loss of contact with reality in a hard and sharp sense; third, that there was a gradual disintegration of his personality. Yet while noticing this, I also noticed that this whole idea of a man withdrawing from the world had a striking similarity to the life of my grandmother, who, in her religious life, was certainly withdrawn from the world as much as anybody has ever been withdrawn from it, as much as anyone can live in this world and not have anything to do with it.”

If all this has its surrealist aspect, Wright also has a very clear sense of it as (to put it in naturalistic terms) a survival mechanism. In the much shorter version of the text that readers have known for decades, the story of Fred Daniels opens with him plunging directly into the underworld. We soon learn that the police are on his back. But only now, with the novel in its restored form, do you see how they got inside his head -- and all the violence that put them there.

Pennsylvania Campuses Hit Hard by June Job Cuts

Beyond enrollment declines, colleges have cited the fallout of pro-Palestinian protests, the botched FAFSA rollout an

Share This Article

More from intellectual affairs.

The Philosophy of Rapture

Scott McLemee reviews Christopher Hamilton’s Rapture .

Fall Books Roundup

Scott McLemee looks ahead to forthcoming releases on higher ed, the culture wars and leadership.

Insurrection

Scott McLemee reviews John Rennie Short’s Insurrection: What the January 6 Assault on the Capitol Reveals about A

- Become a Member

- Sign up for Newsletters

- Learning & Assessment

- Diversity & Equity

- Career Development

- Labor & Unionization

- Shared Governance

- Academic Freedom

- Books & Publishing

- Financial Aid

- Residential Life

- Free Speech

- Physical & Mental Health

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Socioeconomics

- Traditional-Age

- Adult & Post-Traditional

- Teaching & Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Publishing

- Data Analytics

- Administrative Tech

- Alternative Credentials

- Financial Health

- Cost-Cutting

- Revenue Strategies

- Academic Programs

- Physical Campuses

- Mergers & Collaboration

- Fundraising

- Research Universities

- Regional Public Universities

- Community Colleges

- Private Nonprofit Colleges

- Minority-Serving Institutions

- Religious Colleges

- Women's Colleges

- Specialized Colleges

- For-Profit Colleges

- Executive Leadership

- Trustees & Regents

- State Oversight

- Accreditation

- Politics & Elections

- Supreme Court

- Student Aid Policy

- Science & Research Policy

- State Policy

- Colleges & Localities

- Employee Satisfaction

- Remote & Flexible Work

- Staff Issues

- Study Abroad

- International Students in U.S.

- U.S. Colleges in the World

- Seeking a Faculty Job

- Advancing in the Faculty

- Seeking an Administrative Job

- Advancing as an Administrator

- Beyond Transfer

- Call to Action

- Confessions of a Community College Dean

- Higher Ed Gamma

- Higher Ed Policy

- Just Explain It to Me!

- Just Visiting

- Law, Policy—and IT?

- Leadership & StratEDgy

- Leadership in Higher Education

- Learning Innovation

- Online: Trending Now

- Resident Scholar

- University of Venus

- Student Voice

- Academic Life

- Health & Wellness

- The College Experience

- Life After College

- Academic Minute

- Weekly Wisdom

- Reports & Data

- Quick Takes

- Advertising & Marketing

- Consulting Services

- Data & Insights

- Hiring & Jobs

- Event Partnerships

4 /5 Articles remaining this month.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

- Sign Up, It’s FREE

Advertise Contact Privacy

Browse All Reviews

New Releases

List Reviews by Rating

List Reviews by Author

List Reviews by Title

The Man Who Lived Underground (Review, Recap & Full Summary)

By richard wright.

Book review, full book summary and synopsis for The Man Who Lived Underground by Richard Wright, a (very literary) story about man who is coerced into a false confession and flees to live in the sewers.

(The Full Plot Summary is also available, below)

Full Plot Summary

The one paragraph version of this: Fred Daniels is a black man who gets accused of a double homicide, and the police beat him until he is semi-conscious to coerce him to sign a false confession. He is able to escape into the sewers, where he sets up a makeshift camp. In the tunnels, he dig holes in walls to access various businesses where he steals money, valuables, tools, food and water, etc. He later sees others get falsely accused of these crimes, and finally leaves to turn himself in. By now, the police have found the real perpetrator of the double homicide and are worried that Fred will reveal to others that they framed him. They take him back to the sewers and shoot him.

For more detail, see the full Chapter-by-Chapter Summary .

If this summary was useful to you, please consider supporting this site by leaving a tip ( $2 , $3 , or $5 ) or joining the Patreon !

Book Review

The Man Who Lived Underground by Richard Wright is a novella published in April 2021, the truncated form of which was published as a short story in Wright’s Eight Men collection. Written in the early 1940’s, Wright’s publisher declined to publish it in its full form, fearing it was too graphic and controversial.

While many often discuss how this story was likely influenced by Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground , Wright’s inspiration for the plot itself was from a true crime story published in August 1941 involving a string of unsolved robberies in the same neighborhood where no signs of burglary could be found.

In The Man Who Lived Underground , Fred is a man who has been forced to sign a false confession for murder, demoralized and treated in a way that leads him to understand that he no longer has a place in the world. As he flees into the underground, he wrestles with this new perspective and tries to reconcile it with things like his religious upbringing. In the meantime, he finds that through the sewer system, he can tunnel into the basements of local business and take what he likes.

There is a strong existentialist and nihilistic bent to the character of Fred once he is underground and no longer within the grasp of society. The injustice he experiences forces him to question his morals, his values, his perception of what is valuable in the world and his religion.

In a pandemic-ridden world where we are struggling to face our systemic racial inequalities and other incomprehensible things, The Man Who Lived Underground was almost a weirdly timely book. From his marginalization and unjust treatment at the hands of the police, to trying to understand the world in the face of tragedies, a lot of the sentiments and frustrations that the character expressed are easily translatable into present day. To me, this book was primarily about the demoralizing effect of police brutality, injustice and racism. The main character’s turn towards nihilism is likely relatable for those who have experienced similar things in their lives.

Read it or Skip it?

The Man Who Lived Underground is an aggressively literary and intellectual story. If taken at face value, the story seems somewhat ridiculous, so you really have to appreciate and try to understand what it’s trying to say to enjoy much of the story.

That said, if you do take the time to think about it, it really is a surprisingly (or perhaps, sadly) timely book which expresses a lot of the frustrations and sentiments we are dealing with in present day. While police brutality plays a part to the story, the protagonist’s feelings of being demoralized, detached and alienated from the rest of the world will ring true to many, regardless of race. One of the fundamental questions it seems to ask is, how does one exist in a world with such injustice? What is right or wrong in such a world?

Doubtlessly, this book has plenty of literary value, but nevertheless, it still limits the people who I would recommend this to. And while it makes sense to publish this as a part of Wright’s literary cannon, it should be noted that the short story version of it explores much of the same stuff. Still, if you liked books like The Old Man and the Sea and stuff like that in English class, then you’re probably the type of person who will enjoy dissecting something like this.

For casual readers, I’d say this is probably a hard pass. If your book club likes Reese Witherspoon’s Book Club-type titles, also probably a hard pass. However, if your book club does dive into serious literary fiction from time to time, there is plenty to discuss in this book.

See The Man Who Lived Underground on Amazon.

Book Excerpt

Read the first pages of The Man Who Lived Underground

Share this post

Middle of the Night

The Housemaid is Watching

She’s Not Sorry

The Seven Year Slip

Darling Girls

It Finally Happened + Summer Romances

Best Literary Fiction of 2024 (New & Anticipated)

The Housemaid Book Series Recap

2024’s Best Book Club Books (New & Anticipated)

Bookshelf: Development Diary

Share your thoughts Cancel reply

The Man Who Lived Underground

28 pages • 56 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Story Analysis

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

How would you describe the narrative voice of “The Man Who Lived Underground” and how does it affect your understanding of the story?

Fred seems to grow aware of certain truths about the world while he’s underground. Why can’t he articulate them? Would it make any difference to the aboveground world if he could?

What is the significance of the movie theater Fred visits? What lesson does he draw there? Why does Wright include this scene in the story?

Related Titles

By Richard Wright

Big Black Good Man

Big Boy Leaves Home

Bright and Morning Star

The Man Who Was Almost a Man

Uncle Tom's Children

Featured Collections

African American Literature

View Collection

Black History Month Reads

Books on Justice & Injustice

The Best of "Best Book" Lists

- Literature & Fiction

- Genre Fiction

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The Man Who Lived Underground: A Novel Paperback – November 8, 2022

New York Times Bestseller • One of the Best Books of the Year by Time magazine, the Chicago Tribune , the Boston Globe, and Esquire, and one of Oprah’s 15 Favorite Books of the Year

From the legendary author of Native Son and Black Boy, the novel he was unable to publish during his lifetime—an explosive story of racism, injustice, brutality, and survival. "Not just Wright's masterwork, but also a milestone in African American literature . . . One of those indispensable works that reminds all its readers that, whether we are in the flow of life or somehow separated from it, above- or belowground, we are all human." (Gene Seymour, CNN.com)

“ The Man Who Lived Underground reminds us that any ‘greatest writers of the 20th century’ list that doesn’t start and end with Richard Wright is laughable. It might very well be Wright’s most brilliantly crafted, and ominously foretelling, book.”—Kiese Laymon

Fred Daniels, a Black man, is picked up by the police after a brutal double murder and tortured until he confesses to a crime he did not commit. After signing a confession, he escapes from custody and flees into the city’s sewer system.

This is the devastating premise of Richard Wright's scorching novel, The Man Who Lived Underground, written between his landmark books Native Son (1940) and Black Boy (1945), at the height of his creative powers. Now, for the first time, by special arrangement between the Library of America and the author’s estate, the full text of the work that meant more to Wright than any other (“I have never written anything in my life that stemmed more from sheer inspiration”) is published in the form that he intended, complete with his companion essay, “Memories of My Grandmother.” Malcolm Wright, the author’s grandson, contributes an afterword.

- Print length 240 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Harper Perennial Modern Classics

- Publication date November 8, 2022

- Dimensions 5.31 x 0.54 x 8 inches

- ISBN-10 0062971484

- ISBN-13 978-0062971487

- See all details

Products related to this item .sp_detail_sponsored_label { color: #555555; font-size: 11px; } .sp_detail_info_icon { width: 11px; vertical-align: text-bottom; fill: #969696; } .sp_info_link { text-decoration:none !important; } #sp_detail_hide_feedback_string { display: none; } .sp_detail_sponsored_label:hover { color: #111111; } .sp_detail_sponsored_label:hover .sp_detail_info_icon { fill: #555555; } Sponsored (function(f) {var _np=(window.P._namespace("FirebirdSpRendering"));if(_np.guardFatal){_np.guardFatal(f)(_np);}else{f(_np);}}(function(P) { P.when("A", "a-carousel-framework", "a-modal").execute(function(A, CF, AM) { var DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX = 'adFeedback:desktop:multiAsinAF:sp_detail'; A.declarative('sp_detail_feedback-action', 'click', function(event) { var MODAL_NAME_PREFIX = 'multi_af_modal_'; var MODAL_CLASS_PREFIX = 'multi-af-modal-'; var BASE_16 = 16; var UID_START_INDEX = 2; var uniqueIdentifier = Math.random().toString(BASE_16).substr(UID_START_INDEX); var modalName = MODAL_NAME_PREFIX + "sp_detail" + uniqueIdentifier; var modalClass = MODAL_CLASS_PREFIX + "sp_detail" + uniqueIdentifier; initModal(modalName, modalClass); removeModalOnClose(modalName); }); function initModal (modalName, modalClass) { var trigger = A.$(' '); var initialContent = ' ' + ' ' + ' '; var HEADER_STRING = "Leave feedback"; if (false) { HEADER_STRING = "Ad information and options"; } var modalInstance = AM.create(trigger, { 'content': initialContent, 'header': HEADER_STRING, 'name': modalName }); modalInstance.show(); var serializedPayload = generatePayload(modalName); A.$.ajax({ url: "/af/multi-creative/feedback-form", type: 'POST', data: serializedPayload, headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json', 'Accept': 'application/json'}, success: function(response) { if (!response) { return; } modalInstance.update(response); var successMetric = DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX + ":formDisplayed"; if (window.ue && window.ue.count) { window.ue.count(successMetric, (window.ue.count(successMetric) || 0) + 1); } }, error: function(err) { var errorText = 'Feedback Form get failed with error: ' + err; var errorMetric = DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX + ':error'; P.log(errorText, 'FATAL', DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX); if (window.ue && window.ue.count) { window.ue.count(errorMetric, (window.ue.count(errorMetric) || 0) + 1); } modalInstance.update(' ' + "Error loading ad feedback form." + ' '); } }); return modalInstance; } function removeModalOnClose (modalName) { A.on('a:popover:afterHide:' + modalName, function removeModal () { AM.remove(modalName); }); } function generatePayload(modalName) { var carousel = CF.getCarousel(document.getElementById("sp_detail")); var EMPTY_CARD_CLASS = "a-carousel-card-empty"; if (!carousel) { return; } var adPlacementMetaData = carousel.dom.$carousel.context.getAttribute("data-ad-placement-metadata"); var adDetailsList = []; if (adPlacementMetaData == "") { return; } carousel.dom.$carousel.children("li").not("." + EMPTY_CARD_CLASS).each(function (idx, item) { var divs = item.getElementsByTagName("div"); var adFeedbackDetails; for (var i = 0; i

From the Publisher

| Customer Reviews | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price | — | — | — | $6.99$6.99 |

| Richard Wright's Novels |

| Customer Reviews | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price | — | — | — | — | $12.93$12.93 |

| More from Richard Wright |

Editorial Reviews

“ The Man Who Lived Underground reminds us that any ‘greatest writers of the 20 th century’ list that doesn’t start and end with Richard Wright is laughable. It might very well be Wright’s most brilliantly crafted, and ominously foretelling, book.” — Kiese Laymon

"A tale for today. . . . [Wright's] restored novel feels wearily descriptive of far too many moments in contemporary America." — New York Times

"The power and pain of Wright’s writing are evident in this wrenching novel. . . . Wright makes the impact of racist policing palpable as the story builds to a gut-punch ending, and the inclusion of his essay “Memories of My Grandmother” illuminates his inspiration for the book. This nightmarish tale of racist terror resonates." — Publishers Weekly

“Propulsive, haunting. . . . The graphic, gripping book ends with a revealing companion essay that further explains the themes of this searing novel.” — Oprah Daily

"It's impossible to read Wright’s novel without thinking of this 21st-century moment. . . . Wright deserves sensitive reconsideration, especially now that so many of us have been proved naive in our belief that an honest rendering of Black people might lead to recognition of our existence in the universality of humanity." — Imani Perry, The Atlantic

"Finally, this devastating inquiry into oppression and delusion, this timeless tour de force, emerges in full, the work Wright was most passionate about, as he explains in the profoundly illuminating essay, 'Memories of My Grandmother,' also published here for the first time. This blazing literary meteor should land in every collection." — Booklist (starred review)

"A welcome literary resurrection that deserves a place alongside Wright’s best-known work." — Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

"Never did Wright approach race more directly than in The Man Who Lived Underground ." — Los Angeles Times

"Not just Wright's masterwork, but also a milestone in African American literature . . . The Man Who Lived Underground is one of those indispensable works that reminds all its readers that, whether we are in the flow of life or somehow separated from it, above- or belowground, we are all human." — Gene Seymour, CNN.com

"Like a telegram from mid-century America warning us about our very present, Richard Wright’s novel arrived with the shock of recognition for readers in the midst of a reckoning with racial injustice." — Time Magazine

"To read The Man Who Lived Underground today . . . is to recognize an author who knew his work could be shelved for decades without depreciation. Because this is America. Because police misconduct, to use the genteel 2021 term, is ageless." — Chicago Tribune

"Moves continuously forward with its masterful blend of action and reflection, a kind of philosophy on the run. . . . Whether or not The Man Who Lived Underground is Wright’s single finest work, it must be counted among his most significant." — Clifford Thompson, Wall Street Journal

“Enthralling. . . . You could say that the book’s release now is timely, given that it contains an account of police torture. . . . But that feels false because Wright’s story would have been just as relevant if it had been released 10 years ago or 30, 50, or 80—when he composed it. . . . Maybe, then, it’s more accurate to think of The Man Who Lived Underground as timeless rather than timely.” — New Republic

"This is a significant work of literary fiction from a legendary author that’s absolutely not to be missed." — Book Riot

"Nothing less than the reestablishing of a major legacy." — The Chicago Tribune

“The Man Who Lived Underground is a masterpiece." — Time Magazine

About the Author

Product details.

- Publisher : Harper Perennial Modern Classics (November 8, 2022)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 240 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0062971484

- ISBN-13 : 978-0062971487

- Item Weight : 6.4 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.31 x 0.54 x 8 inches

- #1,805 in Short Stories (Books)

- #2,184 in Classic Literature & Fiction

- #5,123 in Literary Fiction (Books)

About the author

Richard wright.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Products related to this item .sp_detail2_sponsored_label { color: #555555; font-size: 11px; } .sp_detail2_info_icon { width: 11px; vertical-align: text-bottom; fill: #969696; } .sp_info_link { text-decoration:none !important; } #sp_detail2_hide_feedback_string { display: none; } .sp_detail2_sponsored_label:hover { color: #111111; } .sp_detail2_sponsored_label:hover .sp_detail2_info_icon { fill: #555555; } Sponsored (function(f) {var _np=(window.P._namespace("FirebirdSpRendering"));if(_np.guardFatal){_np.guardFatal(f)(_np);}else{f(_np);}}(function(P) { P.when("A", "a-carousel-framework", "a-modal").execute(function(A, CF, AM) { var DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX = 'adFeedback:desktop:multiAsinAF:sp_detail2'; A.declarative('sp_detail2_feedback-action', 'click', function(event) { var MODAL_NAME_PREFIX = 'multi_af_modal_'; var MODAL_CLASS_PREFIX = 'multi-af-modal-'; var BASE_16 = 16; var UID_START_INDEX = 2; var uniqueIdentifier = Math.random().toString(BASE_16).substr(UID_START_INDEX); var modalName = MODAL_NAME_PREFIX + "sp_detail2" + uniqueIdentifier; var modalClass = MODAL_CLASS_PREFIX + "sp_detail2" + uniqueIdentifier; initModal(modalName, modalClass); removeModalOnClose(modalName); }); function initModal (modalName, modalClass) { var trigger = A.$(' '); var initialContent = ' ' + ' ' + ' '; var HEADER_STRING = "Leave feedback"; if (false) { HEADER_STRING = "Ad information and options"; } var modalInstance = AM.create(trigger, { 'content': initialContent, 'header': HEADER_STRING, 'name': modalName }); modalInstance.show(); var serializedPayload = generatePayload(modalName); A.$.ajax({ url: "/af/multi-creative/feedback-form", type: 'POST', data: serializedPayload, headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json', 'Accept': 'application/json'}, success: function(response) { if (!response) { return; } modalInstance.update(response); var successMetric = DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX + ":formDisplayed"; if (window.ue && window.ue.count) { window.ue.count(successMetric, (window.ue.count(successMetric) || 0) + 1); } }, error: function(err) { var errorText = 'Feedback Form get failed with error: ' + err; var errorMetric = DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX + ':error'; P.log(errorText, 'FATAL', DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX); if (window.ue && window.ue.count) { window.ue.count(errorMetric, (window.ue.count(errorMetric) || 0) + 1); } modalInstance.update(' ' + "Error loading ad feedback form." + ' '); } }); return modalInstance; } function removeModalOnClose (modalName) { A.on('a:popover:afterHide:' + modalName, function removeModal () { AM.remove(modalName); }); } function generatePayload(modalName) { var carousel = CF.getCarousel(document.getElementById("sp_detail2")); var EMPTY_CARD_CLASS = "a-carousel-card-empty"; if (!carousel) { return; } var adPlacementMetaData = carousel.dom.$carousel.context.getAttribute("data-ad-placement-metadata"); var adDetailsList = []; if (adPlacementMetaData == "") { return; } carousel.dom.$carousel.children("li").not("." + EMPTY_CARD_CLASS).each(function (idx, item) { var divs = item.getElementsByTagName("div"); var adFeedbackDetails; for (var i = 0; i

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Customers say

Customers find the storyline amazing and meaningful. They also appreciate the content, writing quality, and brevity. Readers also mention the writing is intrigue, social instructiveness, and brief.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Customers find the storyline compelling, riveting, and complex. They also say it's an excellent short read and a timely work from a great author.

"...What a great novel that holds relevance many, many decades later...." Read more

" Very fascinating . The "Afterword" explains it all!" Read more

"...Wright created in The Man Who Lived Underground an intense, inventive story about an innocent black man, beaten by police, who escapes into the..." Read more

"...Stunning. Emotional pile driver ." Read more

Customers find the content amazing, interesting, and worthy addition to Richard Wright's legacy. They also describe the book as stunning and emotional.

"... Wright is brilliant and this book is just another exemplary display of his storytelling genius." Read more

"... Stunning . Emotional pile driver." Read more

"...The whole packed a punch. The book offers that combination of literary excellence , social instructiveness and brevity that has marked many a high..." Read more

"...societal narrative and its gravitational pull on the individual is genius and frightening." Read more

Customers find the writing quality of the book insightful, concise, and creative. They also enjoy the pace and brilliant talents of Richard Wright.

"...Like all of his books, he writes with a quick storytelling pace that makes you feel like you are experiencing the story alongside the main character..." Read more

"...The afterword by Malcolm Wright, grandson, was insightful and concise ." Read more

"...that combination of literary excellence, social instructiveness and brevity that has marked many a high school and college lit teaching classic." Read more

"...It begins with a creative edge , gives you burdensome racial slurring, and ends in cliche but sincere allusion. What does that mean?..." Read more

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Living Underground: A Surprisingly Bright Idea

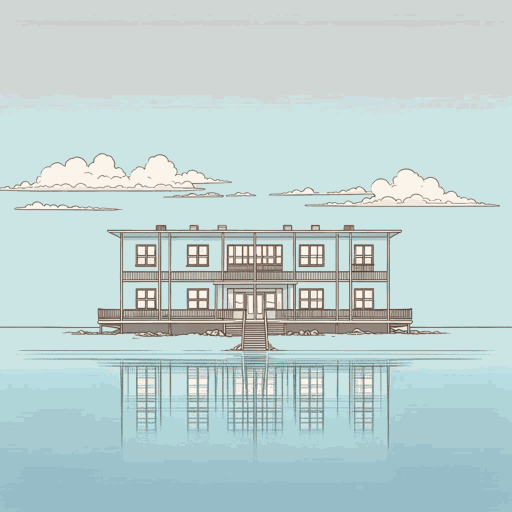

Travis and Ingram’s house (Photo: Dragonfly Hill )

In 2012, Steve Travis and Jeff Ingram buried their house. At first, it looked like a dirty mound until Jeff, the gardener of the two, got some wildflower seeds and meadow grass seeds and, together, they planted the roof. Slowly, the flowers and grasses grew up, and the house, still buried, started becoming really beautiful.

“Now, of course, we have to mow the roof, which is kind of a weird thing,” says Travis.

When Travis and Ingram explain that they’re building an earth-sheltered house, a type of underground house, most people think that they’ve living in a cave. But it’s not like that. The south side is almost entirely window, and on the east and west sides, too, there are big arched windows. At certain times of day, the light streams right through the house, from one end to the other.

From the outside, though, the house is camouflaged by soil. The design represents a longtime dream for the men, who got married recently after being together for 25 years. They wanted the house to blending into the environment, and this type of design, they decided, was one of the best ways to do that. And, sunny as the house is, being inside does feel like living underground, in a way. “You can kind of get the sense of the mass of the house that’s around you,” says Travis. “It’s not imposing, but it’s…I want to say womb-like. It’s very comforting.”

Inside Travis and Ingram’s house (Photo: Dragonfly Hill )

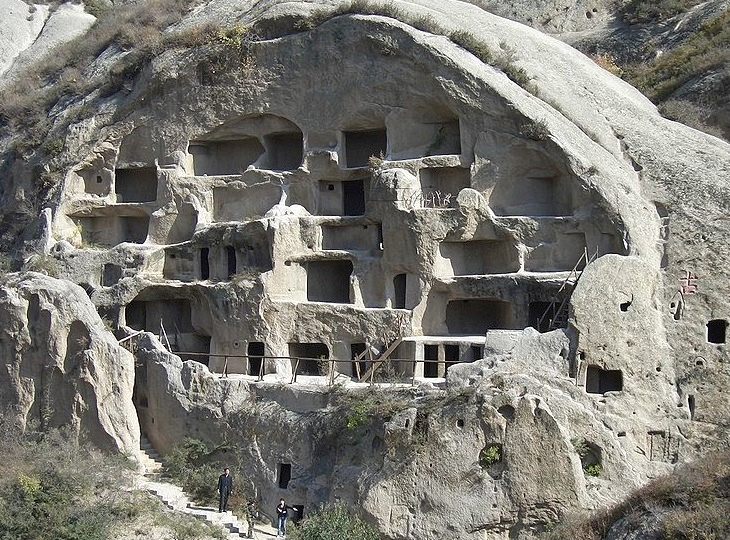

Humans have been building underground housing for millennia; in northern China, cave dwellings date back to the second millennia B.C., and millions of people live still in earth-sheltered houses. Underground housing started out simple, like the dugout house that the Ingalls family moves into, on the banks of Plum Creek, in the Little House series, with vines of flowers framing the door, a thick sod wall fronting it, and a grassy roof that, as Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote, “No one could have guessed…was a roof.”

These days, there are houses built underground in former missile silos, and “iceberg” houses , where beneath a normal-sized house, extensive, luxurious basements might contain everything from bowling alleys to swimming pools. But in America, there are also some thousands of more modest underground houses. Relative to the Ingalls’ one-room sod house, these are sod mansions. But in the scheme of American ostentation, they are among the houses most gentle to the environment that they’re built in and also some of the longest lasting. While suburban McMansion might not last the decade, some of these earth-sheltered houses could be around thousands of years from now.

Ancient cave dwellings in China (Photo: pfctdayelise/Wikimedia )

Underground housing in America would not exist in its present form if not for Malcolm Wells, an architect who grew up in southern New Jersey and migrated later in his life to Cape Cod, Massachusetts. At the beginning of his career, Wells was a conventional architect, whose most prestigious accomplishment was his work on the RCA pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. Not long after that, he looked at the work he was doing and its destructive and transient nature, and he developed a new philosophy of building, which he called “gentle architecture.”

“What would happen if roofs and wall slopes became places for things to grow instead of places for cracked asphalt and graffiti?” he wrote i n a book outlining his ideas . “What if architects routinely brought dying land back to good health?”

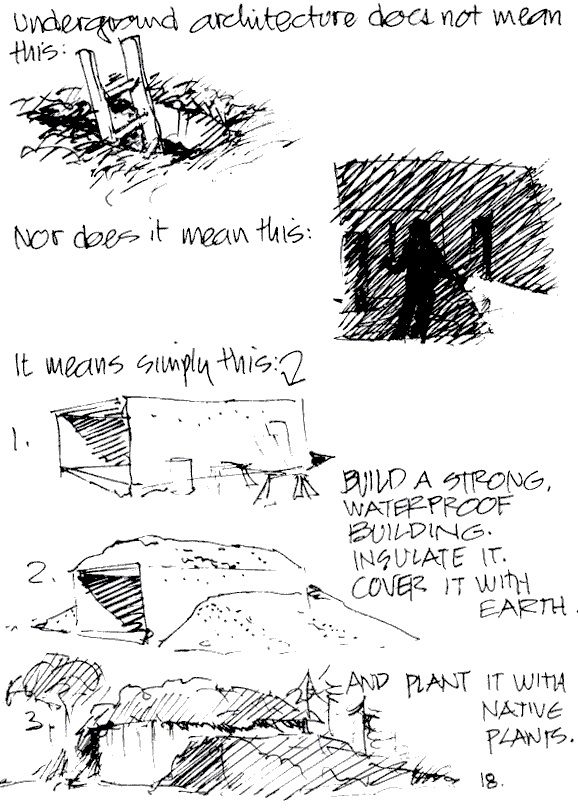

Underground architecture was not the only strategy he saw for achieving this, but it was one of his most original ideas. While not the only way to build without the destroying the land, “it’s simply one of the most promising (and overlooked) of ways,” he wrote. Here’s how he explained it:

(Image: Malcolm Wells )

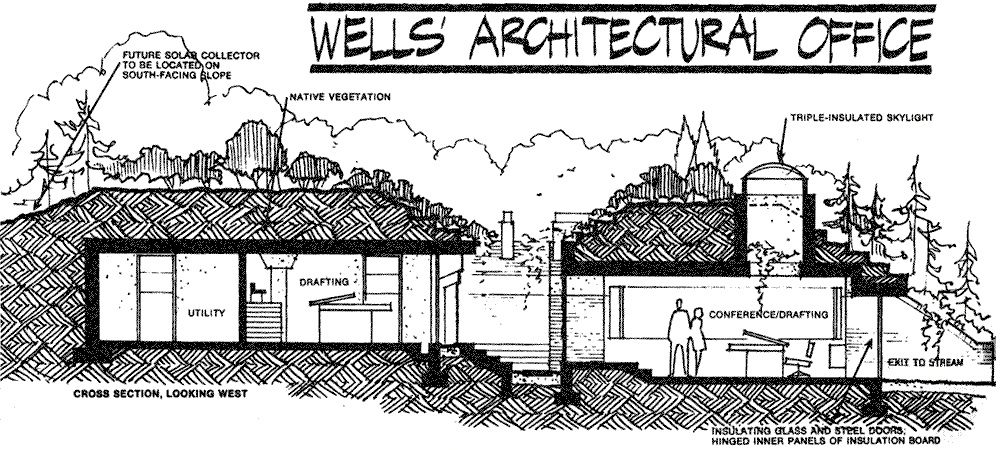

One of the first underground buildings he designed and built was his own office, in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, just outside of Camden.

(Image: Malcolm Wells )

From the entrance, it almost looks as if there’s nothing on the lot.

The entrance to Wells’ office (now occupied by a PR company) (Photo: lamidesign/Flickr )

But that path cuts down into the ground, until it ducks under an entranceway, and into a garden. It’s almost like entering a hidden world.

“Malcolm Wells popularized earth-sheltered housing,” says Rob Roy, the author of Earth-Sheltered Houses and a designer, too. “He gave so many good reasons for building an earth-sheltered house and green roof.”

Earth-sheltered housing, as it came to be called, has a number of aesthetic and practical advantages. A living roof creates a landscape, instead of the tar sea of a shingled roof. And tucking a house into the ground, whether it’s covered with earth or not, helps the house blend more seamlessly into its site, preserving more of what was attractive about the land itself, before people started to mess with it. On a practical level, pushing piles of earth against the sides of a building means that the temperature just outside changes less dramatically than if the building is exposed to the air. While in some climates, outside temperatures might fluctuate from below freezing to almost unbearable heat, the temperature of the ground stays in smaller range, between about 40 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit. It takes less energy to heat and cool an underground house than a traditional house: it’s essentially like building a house in more advantageous climate than the one you’re actually living in.

These qualities were particularly appealing to environmentally minded innovators in the 1970s through about 1985, in what Roy calls “the halcyon days of earth-sheltered housing.”

“Back in the 1970s, when we had a president in the White House who would put on a sweater, underground housing became very popular,” he says. There was an oil crisis, after all. Fortuitously, a small handful of architects (including Frank Lloyd Wright, who wrote that “the berm-type house, with walls of earth, is practical — a nice for of building anywhere: North , South, East, or West”) were experimenting with these designs when the gas prices jumped and interest in energy-efficient housing rose.

Don Metz, an architect in New Hampshire, built his first earth-sheltered house after he came across a beautiful piece of land with a “killer” southern view. “The idea of putting a wedding cake up there got to me,” he says. “I started thinking about how I could minimize the impact of the house I wanted to put there, and it just evolved, to the thought—why don’t I tuck it into the earth? There wasn’t much literature at the time, so I essentially invented the details myself.”

When the oil crisis hit, the work he had done became the object of intense interest. “I got invited to symposia, and it was a happening thing,” he says. He’d hear from clients who wanted him to design and build this exact sort of house. But then, over time, interest tapered off. “The phone stopped ringing with that particular type of call,” he says. “The public seemed to abandon it.”

Metz’ Treadwell House (Photo: Courtesy of Martha E. Diebold Real Estate)

Still, for a time, there was a groundswell of interest: Wells wrote that there were 15 or 20 architects who would regularly build underground, and that 25,000 people interested in underground architecture had written to him. In that period, too, these architects worked through some of the technical difficulties of building underground houses that were properly insulated and waterproofed. They laid the groundwork for today’s builders of underground houses, who have made the process more efficient and cheaper for the small group of people who choose to live inside the earth.

Today, a few companies around the country specialize in earth-sheltered housing. Generally, they offer customizable designs, and will sell the plans, along with an interior metal structure. Often, these houses, like the one Travis and Ingram are building, are created by spraying concrete onto a metal skeleton, waterproofing the resulting dome, and spreading earth on top and to the sides. They can be small, cabin-like structures—or they can be quite large.

“We’ve designed buildings based on our 24-foot model, that are 700 to 800 square feet, like a hunter’s cabin,” says David Skinner, the president of Performance Building Systems. “We’re also in the middle of designing a winery, that’s going to be huge, 32 by 120 feet, and a residence that’s going to be 7,000 square feet. The range is crazy.”

The range of people for whom they build, too, is wide. “We have people who are extremely green and we have people who you’d identify as preppers, and everything in between,” he says.

There is, though, a certain quality that draws together the people who want to build underground. “It tends to draw romantics and dreamers,” says Metz.

Allan Shope’s earth-bermed house (Photo: Durston-Saylor)

Allan Shope, an architect in the Hudson Valley, used to design large houses for the rich and famous, but now he’s focused on projects of the type where he can take his client out to their site at dawn, sit in silence for 20 minutes and later ask them what they saw, what they heard, and what they think that says the design of their house should be. He’s built six or seven earth-sheltered houses, including the one he lives in.

“We didn’t want to make a big statement to world,” he says. “We love the integration of landscape and architecture, so that the landscape overwhelms the house, so that the house feels subservient to the land.”

Inside Allan Shope’s earth-bermed house (Photo: Durston-Saylor)

More than any other “green” reason for choosing an earth-sheltered house, it’s the blending of the existing place and the new home that makes underground housing worthwhile. Now, it’s possible to build an energy-efficient house in all manner of ways: the LEED system is essentially a mix-and-match template for building an environmentally acceptable building. Earth-sheltering’s only real advantage is that it prioritizes preserving some sense of the land itself.

But these houses still do have a bunker-like aspect to them. They do well in tornados, so the actual house doubles as a storm structure. And, built of concrete, they have an estimated life span of hundreds of years. “There are no gutters to clean, it’s essentially fire-proof, it’s earthquake-resistant,” says Travis. “Anything short of a bunker buster bomb, I would survive.”

“There’s concrete 4,000 years old that’s exposed,” says Skinner. “This is not exposed. We have no clue how long these will last. They could around five to ten thousand years, for all we know.”

Amazon Tribes Want to Remain Isolated–So They're Getting the Internet

Using an ad blocker?

We depend on ad revenue to craft and curate stories about the world’s hidden wonders. Consider supporting our work by becoming a member for as little as $5 a month.

Podcast: Sans Souci Palace

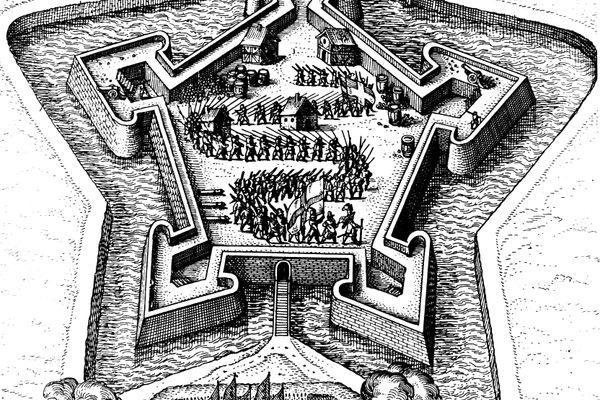

Star Forts Are Military History, and the Base of Some Strange Conspiracy Theories

Podcast: World's Loneliest House

What Can You Do With a 'Failed' Postmodern Utopia?

Step Inside the Giant Dragon of the Wat Samphran Temple

Step Inside Indonesia's Chicken Church

A Home for the Future, Imagined in the Past

Inside a Domed Pyramid With Astounding Acoustics and a History of Miracles

How One Man Built a Sprawling Treehouse With a Dance Floor

Step Inside a Surreal, Dizzying Italian Fortress

Step Inside Gaudí's First House in Barcelona

Explore a Rescued Frank Lloyd Wright Masterpiece

Why There's an 'Italian' Village in Wales

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Pre-Order Atlas Obscura: Wild Life Today!

Add some wonder to your inbox, we'd like you to like us.

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

The Man Who Lived Underground Analysis

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Images and Imagery

The Man Who Lived Underground Analysis. (2016, Jun 04). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/the-man-who-lived-underground-analysis-essay

"The Man Who Lived Underground Analysis." StudyMoose , 4 Jun 2016, https://studymoose.com/the-man-who-lived-underground-analysis-essay

StudyMoose. (2016). The Man Who Lived Underground Analysis . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/the-man-who-lived-underground-analysis-essay [Accessed: 6 Jul. 2024]

"The Man Who Lived Underground Analysis." StudyMoose, Jun 04, 2016. Accessed July 6, 2024. https://studymoose.com/the-man-who-lived-underground-analysis-essay

"The Man Who Lived Underground Analysis," StudyMoose , 04-Jun-2016. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/the-man-who-lived-underground-analysis-essay. [Accessed: 6-Jul-2024]

StudyMoose. (2016). The Man Who Lived Underground Analysis . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/the-man-who-lived-underground-analysis-essay [Accessed: 6-Jul-2024]

- Where I Lived And What I Lived For Pages: 4 (909 words)

- Deconstructing E.E. Cummings' 'anyone lived in a pretty town': A Literary Analysis Pages: 3 (604 words)

- Notes From Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky: Novel Analysis Pages: 3 (812 words)

- Interview with someone who lived during WWII Pages: 6 (1736 words)

- Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground Pages: 10 (2754 words)

- The Weather Underground Pages: 5 (1328 words)

- The Underground Railroad Book Summary Pages: 5 (1481 words)

- Male and Female Archetypes in Eugene Onegin and Notes From Underground Pages: 7 (2040 words)

- Underground to Canada Pages: 2 (378 words)

- If we lived in a perfect world Pages: 3 (631 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

The Spinoff

Pop Culture about 4 hours ago

‘serious ital vibes when i’m blazing’: p digsss shares his perfect weekend playlist.

- Share Story

P Digsss, frontman of the genre-bending Shapeshifter, shares the tunes he keeps on repeat for the perfect weekend.

You don’t need a special scenario to enjoy the musical stylings of Shapeshifter – in fact, it might just be what you need to make the weekend perfect. Just ask their frontman P Digsss because, after all, he’s been doing this for 25 years.

The drum and bass ensemble recently celebrated their quarter century anniversary with sold-out shows across the motu, and limited edition reissues of all of their albums, including Shapeshifter Live. It’s a “bloody great” milestone, P Digsss says, “ still doing what we love and getting better at it. Hard to beat living off one’s art and passion. ”

While the band works on tuning their guitars and preparing for “ a massive set” over the summer, here’s what P Digsss plays to soundtrack the perfect weekend.

Cinematic Orchestra – ‘Everyday’

I love the whole album from start to finish; great way to start my day off, driving to the surf. It has heaps of favourites like ‘All that you give’, ‘Burn Out’ and the incredible ‘All Things To All Men.’ Just magical. It’s one of my favourite albums to cook too as well.

Kyuss – ‘Gardenia’

After a surf on the drive home, Kyuss’ ‘Welcome to Sky Valley’ gets played loud. Love the tuning, the tones and the grit of this monster of an album.

Prince – ‘Purple Rain’

If we are going to say it’s a perfect weekend then I need to hear Prince’s album Purple Rain again from start to finish. It has to be played. He’s the greatest to ever do it.

D’Angelo – ‘Chicken Grease’

I would also check all of D’Angelo ‘Voodoo’ from start to finish … It just makes me want to sing out loud. Timeless wonders such as ‘The Line’, ‘Chicken Grease’ and ‘The Root’ have that soothing vibe, uplifting and just phenomenal musicianship.

Stevie Wonder – ‘Hotter than July ’

Start to finish too – ‘All I Do’, ‘Rocket Love’ and ‘Master Blaster’ are all time. Grew up with this playing at home. It always makes me feel comfy.

Break, Die and MC Fats – ‘Foundation Dub’

This one is a one-off from a comp, the ‘We Gotcha LP,’ honouring the legend MC Fats. Serious ital vibes when I’m blazing.

Ini Kamoze – ‘World-A-Reggae ’

This is from 1984 but timeless. Love a bit of Ini Kamoze! His vocal tones are supreme – “out in the streets they call it murder.”

Shy FX and T. Power – ‘Diary Of A Digital Soundboy’

I think it would be a subpar weekend without some Shy FX, one of the legends of drum and bass. So run the whole album Diary of a Digital Soundboy, from ‘Feelings’ through till ‘Delta VIP’ – top shelf material.

More From Forbes

Have underground music scenes shapeshifted into viral moments.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Khalil Asmall DJing in Brooklyn, New York.

In 2004, just one year after MySpace launched, DJ culture and related niche nightlife scenes underwent a major shift. As party posters and boldly printed graphic fliers started to slowly become extinct for live event promotion, communication and underground communities moved online. Over the last twenty years, the evolution of technology and its impact on facets of everyday life, has drastically changed how culture is transmitted and how communities are connected. Digital viral moments now create an expectation of how an experience will be and simultaneously replace a need to participate in that experience. Has the normalization of bite-sized content erased underground culture or moved the action online?

“Events worked because the community was very much a physical thing, it wasn’t so online-based,” said DJ Khalil Asmall, who recently supervised the music for Netflix’s, The Kitchen , directed by Daniel Kaluuya, and wrapped up 16 years as the co-founder of Livin’ Proof , a London-based event named after DJ Premier’s “Group Home” record .

The same year Twitter launched (2007), Livin’ Proof was born in a small basement in Soho before growing into 800-1000 person capacity rooms at some of London’s premier venues. Every month Asmall along with Snips, Raji Rags, and Budgie helped usher in a new generation of artists, hosting debut international shows for A$AP Rocky , Dom Kennedy and Flatbush Zombies.

Record Stores As A Cultural Hub

Raised on reggae, UK and US hip hop, Motown and surrounded by his fathers’ variety of hand drums, New York-based Asmall started DJing at home for fun when he was a teenager just outside of London. At 18, he joined friends to DJ house parties, working his way into small bars and clubs as the musical talent.

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024

Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024.

A central hub of London’s underground hip hop scene was at Deal Real, a record store on Carnaby Street, where events were held and music was bought and sold. Across the pond in both Los Angeles and New York, record store institution and record label, Fat Beats, was thriving within bicoastal communities and in niche local artist circles. “The community was an ecosystem that gathered together,” said Asmall. While the Livin’ Proof continued to print posters and fliers for promotion, they didn’t collect any data from their community. “I didn’t have to promote our party because people loved it, it wasn’t about me, I wasn’t the center of it–it felt like real community,” said Asmall.

As technology pushed content and digital social interaction to the forefront, platforms like MySpace, Facebook and Twitter found more relevance in the music business although the pace and order in which people used these tools evolved slowly. “MySpace was something you’d do after an experience–you’d load up all the pictures from the party," said James Rubin, Partner and Co Head of Hip Hop at talent agency William Morris Endeavor (WME), where he oversees clients Tyler the Creator, Run The Jewels, Travis Scott, Summer Walker and 6lack. "The difference now is that MySpace isn’t around–you now have a computer in your pocket.”

DJs Become Artists

With the emergence of DJ culture came radio mixes, remixes and mixtape cassettes–a party favor unique to musical “selectors” and an art form now relegated to digital playlists and shareable visual viral streams like Boiler Room , a traveling pop-up with nearly 10,000 DJ performances that was acquired by live ticketing platform, DICE in 2021.

DJs shapeshifted from radio selectors to dance floor directors to internet personalities and producers. With the rise of Instagram, SoundCloud and YouTube, growing a social community has been possible for DJ’s and collectives , removing the flat, single directional communication MySpace or even Facebook (events) offered, allowing DJs to become talent, build visual identities and their own brands.

"DJs became superstars by becoming producers and remixing other people's work or putting out their own records took them to the next level,” said Rubin. "Diplo was one of the early adopters where he was djing in clubs and parties but he was also remixing everyone,” said Rubin. “He was bringing original new sounds to the table, from Baile Funk to Baltimore Club to Dancehall.” From remixing the first video to hit a billion streams on YouTube, “Gangnam Style” by Psy, to Gwen Stefani, Gucci Mane, Lil Nas X and Madonna, Diplo forged a new path for music culture.

"The thing now is that people live on their phones,” said Rubin. “You can stay on your phone in your house and suddenly you don’t need to go out”. The voyeuristic nature of social media has created a unique experience where people feel like they are somehow participating in an event by viewing it through a screen and these viral moments are now the expectation for many.

Living On A Screen

Bite-sized content or miniature trailers that used to be reserved for movie previews now permeate every facet of entertainment content. Promoters, brands, artists and creators develop highlight reels and short videos that are used to show people a glimpse of what happened or what will happen at an event or on a show and in turn, many viewers expect those exact moments to happen and want to be part of those viral moments and capture them to share.

The cycle of expectation created by technology and rewarded by algorithms removes a level of authenticity within a community and creates new priorities for people to participate. Social currency, follower counts and engagement drive participation and motivate all parties incongruently to one place–a screen. “I don’t think people are going to parties for the same reasons. People are here now because they heard the DJ is famous–they’ve seen him or her on Boiler Room. People now want to be part of that viral moment,” said Asmall. “As an artist or DJ you sort of get bullied into this promotional sort of ecosystem all entertainment lives in now. So much content for events–it’s what the platforms want, and as a creator you’re being rewarded for creating this content with followers and views leading to customers.”

Is Long-Form Seeing A Resurgence?

Music, live events, movies, podcasts–everything feels “trailerized”. While there is a surge of short form content, platforms like Spotify are embracing creators and storytelling in new ways–most recently through audiobooks, showing that maybe there is interest in substantially longer plays. “With audio and video podcasts, we see that long-form storytelling is still going strong in spite of short attention spans,” said Anna Sian, Director of Creator Marketing for Podcasts and Audiobooks at Spotify. According to a recent forecast , US podcast listeners will spend an average of 54 minutes per day listening to podcasts with millennials making up 32.7% of podcast listeners.

Tyler, the Creator' performs on stage at Coachella 2024.

The Business Of Live Music

Since the covid pandemic, several small to mid-sized venues have closed or turned over due to high rent and expiring ancient lease terms, pushing many entertainment and DJ communities online. "In New York there are no destinations–it's more about putting on events and they move around and change [venues]. Music has become big business," said Rubin. In April, the Internal Music Summit reported the global dance music industry’s value at $11.8 billion with live events leading growth. “As a genre, electronic music had the smallest fanbase out of rock, Latin and hip-hop but it grew the fastest on streaming and social media platforms in terms of reach and engagement,” wrote Nyshka Chandran in a deeply reported story for Resident Advisor.

ESP HiFi, a Japanese-Style Listening Bar and Cafe.

With a resurgence of vinyl culture seen as a cultural import from Japan’s popular listening bar format, a renewed interest in live yet laid back listening ushers in new ways to listen to and enjoy music in a venue. There are at least a dozen hifi vinyl listening bars in New York City alone.

“There is a bit of a backlash to the fast food culture of social media music consumption, and the reality is that the viral moment you go to see at a club isn’t what you’re going to experience the majority of the time in a crowd,” said Asmall. “There is a growing appetite of people wanting a more authentic experience.”

As digital viral moments jumpstart cultural conversations in music and entertainment, technology has created a new paradigm for community, connection and experiences. With the normalization of bite-sized content, underground culture may not be erased, it may have just moved online.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The Conversation

One Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Forbes Community Guidelines

Our community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain:

- False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in:

- Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user?

- Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.

Thanks for reading our community guidelines. Please read the full list of posting rules found in our site's Terms of Service.

L.A.’s underground celebrates the life of punk iconoclast John Albert

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Once upon a time, the collected works of music journalists, film critics and other cultural correspondents appeared with regularity on the literary landscape.

We relied on their observations to make sense not only of the art we admired and the artists who created it but of the times we lived in and the places we felt at home.

Now? Not so much. The way culture is celebrated, disseminated and reported on has changed, probably forever.

So when a book like “ Running With the Devil: Essays, Articles & Remembrances ” by John Albert appears on the horizon, it feels as anachronistic as a sailing vessel flying the skull and bones.

But John Albert was no ordinary writer.

When he died suddenly from a heart attack last year at the age of 58, he left behind a body of work scattered across the pages of books, anthologies, literary journals and alternative weeklies. His friend and editor, Joe Donnelly, hit on the idea to assemble these pieces in a collection.

“Almost as soon as John died,” Donnelly said, “I started thinking about the responsibility to preserve his writing legacy.”

Donnelly approached their mutual friend Iris Berry, co-founder of Punk Hostage Press , about the project. She didn’t need to be convinced.

“There always seemed to be a kind of magic surrounding John Albert,” Berry said. “A mystery and a charisma that I can’t explain. He definitely left us too soon.”

It’s only fitting, then, that “Running With the Devil” will receive a grand, old-school book launch at Wacko Soap Plant from 4 to 7 p.m. on Sunday, June 30.

Berry and Donnelly will be joined by a crew of underground all-stars that includes Jesse Albert, Jennifer Finch, Brett Gurewitz, Ben Harper, Keith Morris, Arty Nelson, Jerry Stahl, John Waldman and Justin Warfield.

Albert emerged from the exurbs of Los Angeles and embraced the city in all its guises. He was an early member of Christian Death and Bad Religion, two bands whose names suggest a spiritual affinity, or at least a consensus, but couldn’t be more stylistically dissimilar.

He wrote about discovering Black Flag and embracing punk rock with pulp panache: “I have cut my hair short and can’t stop smashing windows.”