- Resources

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- News & Media

Essay: The Oxford English Dictionary

by Renee Brown

When Beowulf, the greatest and oldest single work of Old English, was composed, there was no dictionary; when Chaucer wrote the legendary Canterbury Tales, there was no dictionary, when the Bard of Avon, William Shakespeare, produced his graceful poems and plays, there was no dictionary. The first, what would today be called, “dictionary” was compiled in 1604 by a man named Robert Cawdray; A Table Alphabeticall was only 120 pages. One hundred and fifty years later, Dr. Samuel Johnson published his Dictionary . This respectable publication documented 40,000 words and provided 114,000 quotations. The project took him nine years to complete single handedly (McCrum 117-9). It was not until one hundred years later that a project was begun which would far outperform the work of Johnson. The idea for a new dictionary was proposed by the Philological Society of London; at the time it was titled New English Dictionary , but it would become known to the world as the Oxford English Dictionary .

The OED is the “accepted authority on the evolution of English language over the last millennium” ( Oxford ). The purpose of a dictionary is to encompass a language “in its entirety,” the easy words as well as the hard ones, the common words as well as the obscure ones (Winchester 86). English is a world language, spreading all over the globe, which means that the language is constantly expanding, so all words, written, spoken, and read, should be documented (Winchester 87). The unique aspect of this reference is that it not only gives definitions for terms, like a dictionary is commonly understood to do, but the OED gives the meanings, history, pronunciation, and spelling of every word in the English language, both past and present. It is an etymological analysis of words ( Oxford ). The objective is to record “every word, every nuance, every shading of meaning and spelling and pronunciation, every twist of etymology, every possible illustrative citation from every English author” (Winchester 103). In essence, the OED is a “biography” for every English word (Winchester 105). The noble, yet immense ambition of Dr. James Murray.

When the idea of the dictionary was proposed in 1879, it was predicted to be 6,400 pages which would take ten years to complete; however, five years after the project began, the dictionary had reached only the word “ant” ( Oxford ). Murray was the first editor of the OED . He was born in Scotland and was self-educated. He devoted twenty-eight years of his life to the dictionary before his death in 1915. It was Murray's believe that quotations needed to be in the dictionary in order to “demonstrate the full range of characteristics of each and every word with a very great degree of precision. Quotations could show exactly how a word had been employed over the centuries” (Winchester 25-6). There are several ways to find words to put in a dictionary: listen to words spoken, copy words from other dictionaries, or read (Winchester 94). This final method was to be employed by the Oxford lexicographers. But it was physically impossible for Murray and his associates to read everything ever written, so they asked for contributors to send in words with definitions, quotations, and illustrations to add to the project. Thousands of people answered the call for help, but one individual in particular contributed to the OED like a madman.

Dr. William Chester Minor was born in Connecticut, became a surgeon, and served in the US army during the Civil War (Winchester 13). He suffered from delusions, thinking that the Irish were trying to kill him (Winchester 16). He came to London, and in February of 1872, Minor shot and killed George Merrett, a man who neither knew Minor nor had any contact with him prior to the attack (Winchester 3). Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum became Minor's home and prison (Winchester xiii). After eight years of confinement, Minor heard of Murray's request for contributors to the dictionary, and seeing this as an opportunity for “intellectual stimulus,” he decided to become a contributor (Winchester 113-4). Minor would read the books in his cell and document every word which he found fascinating; in this manner, he stayed a few letters ahead of the men working in Oxford (Winchester 139). Oxford often received hundreds of words from Minor in a single week (Winchester 155). Murray declared that Minor was “the most prolific of thousands of volunteer contributors” (Winchester xi). Neither Dr. Minor nor Dr. Murray lived to see the completed dictionary.

Although his story is far less dramatic than that of Dr. Minor, there was another major contributor to the OED which should be noted. Dr. Fitzedward Hall wrote to Oxford every single day for twenty-two years, making him another memorable contributor to the renowned Oxford English Dictionary (Winchester 167).

Because of the immense size of the project, the OED was published in fascicles. Volume one, A-B was released in 1884 while the final volume took until 1928 to be completed. Many other editors worked diligently on the project. Henry Bradley, born in Manchester, began his work on the OED in 1888 and continued until his death in 1923. William A. Craigie was the third editor. He became editor in 1901, working mainly from the letter N to the end of the alphabet. C.T. Onions claims that he had the last word on the OED because he was responsible for cross-referencing the word “zyxt,” which is literally the final word in the dictionary. Onions also worked on the longest entry in the dictionary, the word “set” ( Oxford ).

The First Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary is ten volumes, totaling 15, 490 pages. It took the editors seventy years to complete the 252,200 entries. The 2,000 contributors sent in five million quotations, 1,861,200 of which appear in the dictionary (Oxford).

Only five years after the publication of the final volume, Oxford University Press, which had assumed the role of publishing the monstrosity, released the Supplement which updated the OED by adding new words. Four more supplementary volumes were completed between 1972 and 1986. In 1989 the Second Edition was published. There have been three other editors who have worked on updates to the OED. Robert Burchfield was born in New Zealand, and he is responsible for broadening the scope of the dictionary to include words used in North America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, and Pakistan. Many words he assimilated into the dictionary were slang terms. The two current editors are Edmund Weiner and John Simpson ( Oxford ).

The Second Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary is twenty volumes, consisting of 21,730 pages. This massive reference weights 137.72 pounds and took 6,243 pounds of ink to print a single copy of the completed work. There are 291,500 entries with fifty-nine million words and 350 million characters. The longest entry is the word “set” which has 430 senses, 60,000 words, and 326,000 characters. In the Second Edition are 2,436,600 quotations. The most often quoted work is the Bible with 25,000 references; the most often quoted author is Shakespeare with 33,300 references. Hamlet alone is quoted almost 1600 times in the dictionary ( Oxfor d).

In 1992 the text was printed on CD-ROM. This project included 120 typists and fifty proofreaders. The endeavor prices at 13.5 million US dollars and took five years to complete ( Oxford ). Recently the OE D has gone online. It took eighteen months and 150 typists to input the dictionary into the correct format (Elliott). Five hundred and forty megabytes of memory are used to hold the complete dictionary ( Oxford ). In order to get the software development needed to input the information, Oxford University Press spent over one million US dollars (Elliott). Never has the dictionary been profitable to Oxford University Press which spent approximately fifty-five million US dollars to fund the revision program (Oxford). Today there is a website for the Oxford English Dictionary . There is also a “word of the day” site produced by the OED on the website.

The Third Edition of the dictionary is due in 2020, but until then, the OED is continually updated with the release of Supplements (Sharpiro “Dictionary” par. 25). Some interesting words and phrases which have found a home in the dictionary, although they may seem as though they do not belong are chat room, chick flick, duh, munchies, wedgie, and wussy (Sharpiro “Short List” par. 2-11). Others include Grinch, beltway, lap dance, road rage, and get real (Sharpiro “Dictionary” par. 7). The longest word in the dictionary is forty-five letters long: Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis, a lung disease “caused by inhaling very fine ash and sand dust” (Sharpio “Short List” par. 13).

The drive to document the history of every English word fueled Dr. Murray and future editors and staff members to work tirelessly on what we now have as the Oxford English Dictionary . It is unarguably the most complete dictionary in the English language, which is being revised daily. The OED is one of the greatest contributions to language yet, and it remains a paradigm of perfection.

Works Cited

Elliott, Laura. “How the Oxford English Dictionary Went Online.” Ariadne. 26 June 2000. <http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue24/oed-tech>.

McCrum, Robert, William Cran, and Robert MacNeil. The Story of English . 2nd ed. New York: Penguin Books, 1992.

Oxford English Dictionary . 2003. <http://www.oed.com>.

Sharpiro, Howard. “Dictionary Grows as English Language Evolves.” Philadelphia Inquirer . 4 February 2003.

Sharpiro, Howard. “A Short List of New Words.” Philadelphia Inquirer . 4 February 2003.

Winchester, Simon. The Professor and the Madman . New York: Harper Perennial, 1998.

- Kathleen Jones White Writing Center

- Stabley Library, Room 203 431 South Eleventh Street Indiana, PA 15705

- Phone: 724-357-3029

- [email protected]

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.6 Definition

Learning objectives.

- Determine the purpose and structure of the definition essay.

- Understand how to write a definition essay.

The Purpose of Definition in Writing

The purpose of a definition essay may seem self-explanatory: the purpose of the definition essay is to simply define something. But defining terms in writing is often more complicated than just consulting a dictionary. In fact, the way we define terms can have far-reaching consequences for individuals as well as collective groups.

Take, for example, a word like alcoholism . The way in which one defines alcoholism depends on its legal, moral, and medical contexts. Lawyers may define alcoholism in terms of its legality; parents may define alcoholism in terms of its morality; and doctors will define alcoholism in terms of symptoms and diagnostic criteria. Think also of terms that people tend to debate in our broader culture. How we define words, such as marriage and climate change , has enormous impact on policy decisions and even on daily decisions. Think about conversations couples may have in which words like commitment , respect , or love need clarification.

Defining terms within a relationship, or any other context, can at first be difficult, but once a definition is established between two people or a group of people, it is easier to have productive dialogues. Definitions, then, establish the way in which people communicate ideas. They set parameters for a given discourse, which is why they are so important.

When writing definition essays, avoid terms that are too simple, that lack complexity. Think in terms of concepts, such as hero , immigration , or loyalty , rather than physical objects. Definitions of concepts, rather than objects, are often fluid and contentious, making for a more effective definition essay.

Writing at Work

Definitions play a critical role in all workplace environments. Take the term sexual harassment , for example. Sexual harassment is broadly defined on the federal level, but each company may have additional criteria that define it further. Knowing how your workplace defines and treats all sexual harassment allegations is important. Think, too, about how your company defines lateness , productivity , or contributions .

On a separate sheet of paper, write about a time in your own life in which the definition of a word, or the lack of a definition, caused an argument. Your term could be something as simple as the category of an all-star in sports or how to define a good movie. Or it could be something with higher stakes and wider impact, such as a political argument. Explain how the conversation began, how the argument hinged on the definition of the word, and how the incident was finally resolved.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your responses.

The Structure of a Definition Essay

The definition essay opens with a general discussion of the term to be defined. You then state as your thesis your definition of the term.

The rest of the essay should explain the rationale for your definition. Remember that a dictionary’s definition is limiting, and you should not rely strictly on the dictionary entry. Instead, consider the context in which you are using the word. Context identifies the circumstances, conditions, or setting in which something exists or occurs. Often words take on different meanings depending on the context in which they are used. For example, the ideal leader in a battlefield setting could likely be very different than a leader in an elementary school setting. If a context is missing from the essay, the essay may be too short or the main points could be confusing or misunderstood.

The remainder of the essay should explain different aspects of the term’s definition. For example, if you were defining a good leader in an elementary classroom setting, you might define such a leader according to personality traits: patience, consistency, and flexibility. Each attribute would be explained in its own paragraph.

For definition essays, try to think of concepts that you have a personal stake in. You are more likely to write a more engaging definition essay if you are writing about an idea that has personal value and importance.

It is a good idea to occasionally assess your role in the workplace. You can do this through the process of definition. Identify your role at work by defining not only the routine tasks but also those gray areas where your responsibilities might overlap with those of others. Coming up with a clear definition of roles and responsibilities can add value to your résumé and even increase productivity in the workplace.

On a separate sheet of paper, define each of the following items in your own terms. If you can, establish a context for your definition.

- Consumer culture

Writing a Definition Essay

Choose a topic that will be complex enough to be discussed at length. Choosing a word or phrase of personal relevance often leads to a more interesting and engaging essay.

After you have chosen your word or phrase, start your essay with an introduction that establishes the relevancy of the term in the chosen specific context. Your thesis comes at the end of the introduction, and it should clearly state your definition of the term in the specific context. Establishing a functional context from the beginning will orient readers and minimize misunderstandings.

The body paragraphs should each be dedicated to explaining a different facet of your definition. Make sure to use clear examples and strong details to illustrate your points. Your concluding paragraph should pull together all the different elements of your definition to ultimately reinforce your thesis. See Chapter 15 “Readings: Examples of Essays” to read a sample definition essay.

Create a full definition essay from one of the items you already defined in Note 10.64 “Exercise 2” . Be sure to include an interesting introduction, a clear thesis, a well-explained context, distinct body paragraphs, and a conclusion that pulls everything together.

Key Takeaways

- Definitions establish the way in which people communicate ideas. They set parameters for a given discourse.

- Context affects the meaning and usage of words.

- The thesis of a definition essay should clearly state the writer’s definition of the term in the specific context.

- Body paragraphs should explain the various facets of the definition stated in the thesis.

- The conclusion should pull all the elements of the definition together at the end and reinforce the thesis.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

The New York Times

Opinionator | the role of a dictionary.

The Role of a Dictionary

Draft is a series about the art and craft of writing.

When it happens I feel as if I have stepped into a Far Side cartoon. I am a magazine editor, and the galley of an article will come back from a proofreader with a low-frequency word circled and this comment in the margin: “Does this word even exist?” or “Is this a real word?”

Usually the word’s meaning is perfectly self-evident, and the word itself is relatively simple like “unbuyable,” if not deliberately goofy like “semi-idiotic-like.” And I think to myself, of course it exists. Look, there it is, right in front of us.

Sometimes the reader puts his or her suspicion differently and asks, “Is this word in the dictionary?” Having recently spent a large amount of time researching how a particularly well-known American dictionary was made, I have a very different notion of what a word’s presence, or even its absence, in a dictionary implies.

Don’t get me wrong: I like dictionaries, including several that I consult online and most of the 11 that are sitting within arm’s reach as I write this. But my recent affair with lexicography has left me certain of a couple of things.

One is that no dictionary contains every word in the language. Even an unabridged dictionary is, well, abridged. The sciences, medicine and technology generate gobs of words that never make it into a dictionary; numerous foreign words that appear in English-language contexts are left out. A great many words are invented all the time, whether for commercial reasons or to amuse one’s friends or to insult one’s enemies, and then they simply vanish from the record.

Another is that dictionary users and dictionary makers sometimes have very different notions of what a dictionary is for. One may think of it as a legal code for language; the other considers it a very partial report. One wants unambiguous answers about spelling and meaning and grammar and usage; the other aims for neutrality, and the more serious he or she is, the more wary the person is of imposing his or her own notions of good English on the language itself.

From online dictionaries we have learned that the most frequently looked-up words sit along the bookish fringe of everyday language. Among the top ten lookups on Merriam-Webster Online at this moment are holistic , pragmatic , caveat , esoteric and bourgeois . Teaching users about words they don’t already know has been, historically, a primary aim of lexicography, and modern dictionaries do this well.

But, say, you’re already a person of wide reading, and it’s rare that you require such help. And spell-check (despite its own problems with low-frequency words and proper names) is getting you past the usual pitfalls of silent letters, double consonants, indiscernible vowels and other orthographic peculiarities. Perhaps you write for a living. But occasionally, before committing to a word, you like to stop and commune with it, give it a look-over and see what the dictionary has to say about it.

The lexicographer, without a lot of space to work with, has reduced the word to what he takes to be its essential meanings. You ask yourself if the relevant sense matches your proposed use.

Of course, consulting dictionaries in this way is part of our intellectual and cultural training. It goes back to Language Arts homework (“use the word in a sentence”) and vocabulary tests. But the committed writer should be loath to substitute the lexicographer’s (no doubt well-informed but hardly infallible) sense of a word for his own. Not that you get to choose, according to your own whims, what words actually mean, but there is always much more to know about a word than what a dictionary can tell you. For example, to read in certain genres and areas is to see, on a regular basis, words used in ways that lexicographers must ignore or struggle to keep up with.

Dictionary publishers love to send out a press release when they’ve caught on to an important new term from social science or youth culture or technology or politics, which is all well and good, but in following Webster’s you’re following the followers. Language is profoundly conventional, so few of us can claim to be innovators, but the ambitious writer tries to avoid saying what has already been said. This is true for ad copy, political speeches, quality nonfiction and most other types of writing. Journalism, obviously, rests entirely on the claim to be delivering something new. And what is new should sound new, seem new and maybe require quotation marks, your copy editor thinks.

Lately I have been reading “Reporting: The Rolling Stone Style,” published in 1977, which collects feature essays from the magazine’s first 10 years. What strikes me about it is that the reporters do not sound like trade journalists circulating information within a community. Rather they sound like explorers returning from far-off lands, breathless with discovery. Their writing is for people in the know, yes, but to a much a greater degree it is for people who are not in the know.

“Don’t misunderstand, they aren’t your traditional Hilton rubes, this Pasadena burgher and the little woman, they have viewed with compassion the Louds and wouldn’t be caught dead in New York in madras shorts or cameras on straps like talismans, but this, this , it does give them pause and they freeze at the curb like Lot’s wives, hit full-face by the nightmare custard pie of it . . . .”

This was an opening sentence in an article by Tom Burke describing a gay pride parade from the point of view of two well-meaning out-of-towners. Few dictionaries would tell you what the writer means by Hilton , Pasadena , little woman , Louds , “this,” Lot’s wives or nightmare custard pie . Accounting for what words can add up to when writers explore and combine their obvious and non-obvious aspects is not what dictionaries do well or, in most cases, at all.

Early in my career as an editor I grew frustrated with what dictionaries could tell me about words and usage. An ideal dictionary would present an array of real-world examples, weighted somewhat to favor the professional over the amateur but also showing everyday usage alongside more literary examples drawn from books and movies and television and so on.

With the rise of serious online dictionaries, there are some that approach this ideal, including Wordnik and Merriam-Webster’s new unabridged version. They provide more raw information about words, enabling users to draw their own conclusions.

What a dictionary is for is rarely what a writer needs: basic help in using individual words. Of course, when a writer needs such help it is critical that he or she gets it. Only it should be kept in mind that good writing may exceed the boundaries suggested, if not intended, by dictionary definitions. As one lexicographer put it, “Nothing worth writing is written from a dictionary.”

David Skinner is the author of “The Story of Ain’t: America, Its Language, and the Most Controversial Dictionary Ever Published.” He is the editor of Humanities magazine, a member of the usage panel for the American Heritage Dictionary and a contributor to The Weekly Standard.

What's Next

Macdonald DeWitt Library at SUNY Ulster

Eng 101 oer: definition.

- Reading to Write

- Why We Write

- Rhetorical Context

- Brainstorming

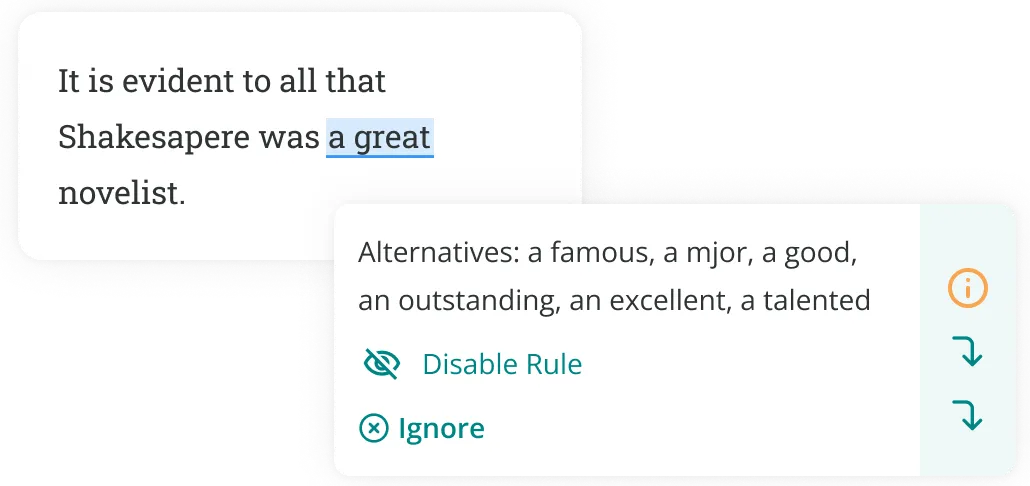

- Proofreading & Editing

- Paragraph Development

- Thesis Statements

- Introductions

- Conclusions

- Transitions & Phrases

- Peer Reviews

- Exemplification

- Classification

- Cause/Effect

- Grammar Resources

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of the definition essay.

- Understand how to write a definition essay.

The Purpose of Definition

The purpose of a definition essay may seem self-explanatory: the purpose of the definition essay is to simply define something. But defining terms in writing is often more complicated than just consulting a dictionary. In fact, the way we define terms can have far-reaching consequences for individuals as well as collective groups.

Take, for example, a word like alcoholism . The way in which one defines alcoholism depends on its legal, moral, and medical contexts. Lawyers may define alcoholism in terms of its legality; parents may define alcoholism in terms of its morality; and doctors will define alcoholism in terms of symptoms and diagnostic criteria. Think also of terms that people tend to debate in our broader culture. How we define words, such as marriage and climate change , has enormous impact on policy decisions and even on daily decisions. Think about conversations couples may have in which words like commitment , respect , or love need clarification.

Defining terms within a relationship, or any other context, can at first be difficult, but once a definition is established between two people or a group of people, it is easier to have productive dialogues. Definitions, then, establish the way in which people communicate ideas. They set parameters for a given discourse, which is why they are so important.

The Structure of a Definition Essay

The definition essay opens with a general discussion of the term to be defined. You then state as your thesis your definition of the term.

The rest of the essay should explain the rationale for your definition. Remember that a dictionary’s definition is limiting, and you should not rely strictly on the dictionary entry. Instead, consider the context in which you are using the word. Context identifies the circumstances, conditions, or setting in which something exists or occurs. Often words take on different meanings depending on the context in which they are used. For example, the ideal leader in a battlefield setting could likely be very different than a leader in an elementary school setting. If a context is missing from the essay, the essay may be too short or the main points could be confusing or misunderstood.

The remainder of the essay should explain different aspects of the term’s definition. For example, if you were defining a good leader in an elementary classroom setting, you might define such a leader according to personality traits: patience, consistency, and flexibility. Each attribute would be explained in its own paragraph.

Writing a Definition Essay

Choose a topic that will be complex enough to be discussed at length. Choosing a word or phrase of personal relevance often leads to a more interesting and engaging essay.

After you have chosen your word or phrase, start your essay with an introduction that establishes the relevancy of the term in the chosen specific context. Your thesis comes at the end of the introduction, and it should clearly state your definition of the term in the specific context. Establishing a functional context from the beginning will orient readers and minimize misunderstandings.

The body paragraphs should each be dedicated to explaining a different facet of your definition. Make sure to use clear examples and strong details to illustrate your points. Your concluding paragraph should pull together all the different elements of your definition to ultimately reinforce your thesis.

Definition Essays

Judy Brady provides a humorous look at responsibilities and relationships in I Want a Wife :

- http://www.columbia.edu/~sss31/rainbow/wife.html

Gayle Rosenwald Smith shares her dislike of the name for a sleeveless T-shirt, The Wife-Beater :

- http://www.usd305.com/212720101692451310/lib/212720101692451310/20100429123836146.pdf

Philip Levine defines What Work Is :

- http://www.ibiblio.org/ipa/poems/levine/what_work_is.php

- http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/what-work-is

Student Sample Essay

Defining Good Students Means More Than Just Grades

Many people define good students as those who receive the best grades. While it is true that good students often earn high grades, I contend that grades are just one aspect of how we define a good student. In fact, even poor students can earn high grades sometimes, so grades are not the best indicator of a student’s quality. Rather, a good student pursues scholarship, actively participates in class, and maintains a positive, professional relationship with instructors and peers.

Good students have a passion for learning that drives them to fully understand class material rather than just worry about what grades they receive in the course. Good students are actively engaged in scholarship, which means they enjoy reading and learning about their subject matter not just because readings and assignments are required. Of course, good students will complete their homework and all assignments, and they may even continue to perform research and learn more on the subject after the course ends. In some cases, good students will pursue a subject that interests them but might not be one of their strongest academic areas, so they will not earn the highest grades. Pushing oneself to learn and try new things can be difficult, but good students will challenge themselves rather than remain at their educational comfort level for the sake of a high grade. The pursuit of scholarship and education rather than concern over grades is the hallmark of a good student.

Class participation and behavior are another aspect of the definition of a good student. Simply attending class is not enough; good students arrive punctually because they understand that tardiness disrupts the class and disrespects the professors. They might occasionally arrive a few minutes early to ask the professor questions about class materials or mentally prepare for the day’s work. Good students consistently pay attention during class discussions and take notes in lectures rather than engage in off-task behaviors, such as checking their cell phones or daydreaming. Excellent class participation requires a balance between speaking and listening, so good students will share their views when appropriate but also respect their classmates’ views when they differ from their own. It is easy to mistake quantity of class discussion comments with quality, but good students know the difference and do not try to dominate the conversation. Sometimes class participation is counted toward a student’s grade, but even without such clear rewards, good students understand how to perform and excel among their peers in the classroom.

Finally, good students maintain a positive and professional relationship with their professors. They respect their instructor’s authority in the classroom as well as the instructor’s privacy outside of the classroom. Prying into a professor’s personal life is inappropriate, but attending office hours to discuss course material is an appropriate, effective way for students to demonstrate their dedication and interest in learning. Good students go to their professor’s office during posted office hours or make an appointment if necessary. While instructors can be very busy, they are usually happy to offer guidance to students during office hours; after all, availability outside the classroom is a part of their job. Attending office hours can also help good students become memorable and stand out from the rest, particularly in lectures with hundreds enrolled. Maintaining positive, professional relationships with professors is especially important for those students who hope to attend graduate school and will need letters of recommendation in the future.

Although good grades often accompany good students, grades are not the only way to indicate what it means to be a good student. The definition of a good student means demonstrating such traits as engaging with course material, participating in class, and creating a professional relationship with professors. While every professor will have different criteria for earning an A in their course, most would agree on these characteristics for defining good students.

Key Takeaways

- Definitions establish the way in which people communicate ideas. They set parameters for a given discourse.

- Context affects the meaning and usage of words.

- The thesis of a definition essay should clearly state the writer’s definition of the term in the specific context.

- Body paragraphs should explain the various facets of the definition stated in the thesis.

- The conclusion should pull all the elements of the definition together at the end and reinforce the thesis.

This is a derivative of WRITING FOR SUCCESS by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution, originally released and is used under CC BY-NC-SA. This work, unless otherwise expressly stated, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

- << Previous: Narration

- Next: Classification >>

- Last Updated: Sep 7, 2023 10:19 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sunyulster.edu/eng101oer

Oxford English Dictionary

Words and phrases, the historical english dictionary.

An unsurpassed guide for researchers in any discipline to the meaning, history, and usage of over 500,000 words and phrases across the English-speaking world.

Understanding entries

Glossaries, abbreviations, pronunciation guides, frequency, symbols, and more

Personal account

Change display settings, save searches and purchase subscriptions

Getting started

Videos and guides about how to use the new OED website

Recently added

- grammaticizing

- okonomiyaki

- bibliographing

- gunsmithing

- broken field

Word of the day

Recently updated.

Word stories

Read our collection of word stories detailing the etymology and semantic development of a wide range of words, including ‘dungarees’, ‘codswallop’, and ‘witch’.

Access our word lists and commentaries on an array of fascinating topics, from film-based coinages to Tex-Mex terms.

World Englishes

Explore our World Englishes hub and access our resources on the varieties of English spoken throughout the world by people of diverse cultural backgrounds.

History of English

Here you can find a series of commentaries on the History of English, charting the history of the English language from Old English to the present day.

- Access or purchase personal subscriptions

- Get our newsletter

- Save searches

- Set display preferences

Institutional access

Sign in with library card

Sign in with username / password

Recommend to your librarian

Institutional account management

Sign in as administrator on Oxford Academic

Word of the Day

Sign up to receive the Oxford English Dictionary Word of the Day email every day.

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information for providing you with this service.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of essay in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- I want to finish off this essay before I go to bed .

- His essay was full of spelling errors .

- Have you given that essay in yet ?

- Have you handed in your history essay yet ?

- I'd like to discuss the first point in your essay.

- boilerplate

- composition

- dissertation

- essay question

- peer review

- go after someone

- go all out idiom

- go down swinging/fighting idiom

- go for it idiom

- go for someone

- shoot the works idiom

- smarten (someone/something) up

- smarten up your act idiom

- square the circle idiom

- step on the gas idiom

essay | Intermediate English

Examples of essay, collocations with essay.

These are words often used in combination with essay .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of essay

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

on top of the world

extremely happy

Keeping up appearances (Talking about how things seem)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun Verb

- Intermediate Noun

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

To add essay to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add essay to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

[ noun es -ey es -ey , e- sey verb e- sey ]

- a short literary composition on a particular theme or subject, usually in prose and generally analytic, speculative, or interpretative.

a picture essay.

- an effort to perform or accomplish something; attempt.

- Philately. a design for a proposed stamp differing in any way from the design of the stamp as issued.

- Obsolete. a tentative effort; trial; assay.

verb (used with object)

- to try; attempt.

- to put to the test; make trial of.

- a short literary composition dealing with a subject analytically or speculatively

- an attempt or endeavour; effort

- a test or trial

- to attempt or endeavour; try

- to test or try out

- A short piece of writing on one subject, usually presenting the author's own views. Michel de Montaigne , Francis Bacon (see also Bacon ), and Ralph Waldo Emerson are celebrated for their essays.

Discover More

Other words from.

- es·sayer noun

- prees·say verb (used without object)

- unes·sayed adjective

- well-es·sayed adjective

Word History and Origins

Origin of essay 1

Example Sentences

As several of my colleagues commented, the result is good enough that it could pass for an essay written by a first-year undergraduate, and even get a pretty decent grade.

GPT-3 also raises concerns about the future of essay writing in the education system.

This little essay helps focus on self-knowledge in what you’re best at, and how you should prioritize your time.

As Steven Feldstein argues in the opening essay, technonationalism plays a part in the strengthening of other autocracies too.

He’s written a collection of essays on civil engineering life titled Bridginess, and to this day he and Lauren go on “bridge dates,” where they enjoy a meal and admire the view of a nearby span.

I think a certain kind of compelling essay has a piece of that.

The current attack on the Jews,” he wrote in a 1937 essay, “targets not just this people of 15 million but mankind as such.

The impulse to interpret seems to me what makes personal essay writing compelling.

To be honest, I think a lot of good essay writing comes out of that.

Someone recently sent me an old Joan Didion essay on self-respect that appeared in Vogue.

There is more of the uplifted forefinger and the reiterated point than I should have allowed myself in an essay.

Consequently he was able to turn in a clear essay upon the subject, which, upon examination, the king found to be free from error.

It is no part of the present essay to attempt to detail the particulars of a code of social legislation.

But angels and ministers of grace defend us from ministers of religion who essay art criticism!

It is fit that the imagination, which is free to go through all things, should essay such excursions.

Related Words

- dissertation

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

Definition of 'essay'

essay in British English

Essay in american english, examples of 'essay' in a sentence essay, cobuild collocations essay, trends of essay.

View usage for: All Years Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

Browse alphabetically essay

- essay competition

- essay contest

- essay discusses

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'E'

Related terms of essay

- essay topic

- photo essay

- short essay

- View more related words

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of essay noun from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

- I have to write an essay this weekend.

- essay on something an essay on the causes of the First World War

- essay about somebody/something Have you done your essay about Napoleon yet?

- in an essay He made some very good points in his essay.

- Essays handed in late will not be accepted.

- Have you done your essay yet?

- He concludes the essay by calling for a corrective.

- I finished my essay about 10 o'clock last night!

- Lunch was the only time she could finish her essay assignment.

- We have to write an essay on the environment.

- You have to answer 3 out of 8 essay questions in the exam.

- the teenage winner of an essay contest

- We have to write an essay on the causes of the First World War.

- be entitled something

- be titled something

- address something

- in an/the essay

- essay about

Definitions on the go

Look up any word in the dictionary offline, anytime, anywhere with the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary app.

Hannah Yang

Table of Contents

Words to use in the essay introduction, words to use in the body of the essay, words to use in your essay conclusion, how to improve your essay writing vocabulary.

It’s not easy to write an academic essay .

Many students struggle to word their arguments in a logical and concise way.

To make matters worse, academic essays need to adhere to a certain level of formality, so we can’t always use the same word choices in essay writing that we would use in daily life.

If you’re struggling to choose the right words for your essay, don’t worry—you’ve come to the right place!

In this article, we’ve compiled a list of over 300 words and phrases to use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essay.

The introduction is one of the hardest parts of an essay to write.

You have only one chance to make a first impression, and you want to hook your reader. If the introduction isn’t effective, the reader might not even bother to read the rest of the essay.

That’s why it’s important to be thoughtful and deliberate with the words you choose at the beginning of your essay.

Many students use a quote in the introductory paragraph to establish credibility and set the tone for the rest of the essay.

When you’re referencing another author or speaker, try using some of these phrases:

To use the words of X

According to X

As X states

Example: To use the words of Hillary Clinton, “You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health.”

Near the end of the introduction, you should state the thesis to explain the central point of your paper.

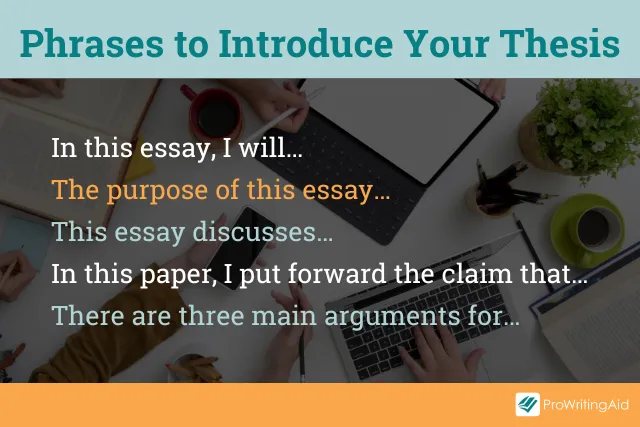

If you’re not sure how to introduce your thesis, try using some of these phrases:

In this essay, I will…

The purpose of this essay…

This essay discusses…

In this paper, I put forward the claim that…

There are three main arguments for…

Example: In this essay, I will explain why dress codes in public schools are detrimental to students.

After you’ve stated your thesis, it’s time to start presenting the arguments you’ll use to back up that central idea.

When you’re introducing the first of a series of arguments, you can use the following words:

First and foremost

First of all

To begin with

Example: First , consider the effects that this new social security policy would have on low-income taxpayers.

All these words and phrases will help you create a more successful introduction and convince your audience to read on.

The body of your essay is where you’ll explain your core arguments and present your evidence.

It’s important to choose words and phrases for the body of your essay that will help the reader understand your position and convince them you’ve done your research.

Let’s look at some different types of words and phrases that you can use in the body of your essay, as well as some examples of what these words look like in a sentence.

Transition Words and Phrases

Transitioning from one argument to another is crucial for a good essay.

It’s important to guide your reader from one idea to the next so they don’t get lost or feel like you’re jumping around at random.

Transition phrases and linking words show your reader you’re about to move from one argument to the next, smoothing out their reading experience. They also make your writing look more professional.

The simplest transition involves moving from one idea to a separate one that supports the same overall argument. Try using these phrases when you want to introduce a second correlating idea:

Additionally

In addition

Furthermore

Another key thing to remember

In the same way

Correspondingly

Example: Additionally , public parks increase property value because home buyers prefer houses that are located close to green, open spaces.

Another type of transition involves restating. It’s often useful to restate complex ideas in simpler terms to help the reader digest them. When you’re restating an idea, you can use the following words:

In other words

To put it another way

That is to say

To put it more simply

Example: “The research showed that 53% of students surveyed expressed a mild or strong preference for more on-campus housing. In other words , over half the students wanted more dormitory options.”

Often, you’ll need to provide examples to illustrate your point more clearly for the reader. When you’re about to give an example of something you just said, you can use the following words:

For instance

To give an illustration of

To exemplify

To demonstrate

As evidence

Example: Humans have long tried to exert control over our natural environment. For instance , engineers reversed the Chicago River in 1900, causing it to permanently flow backward.

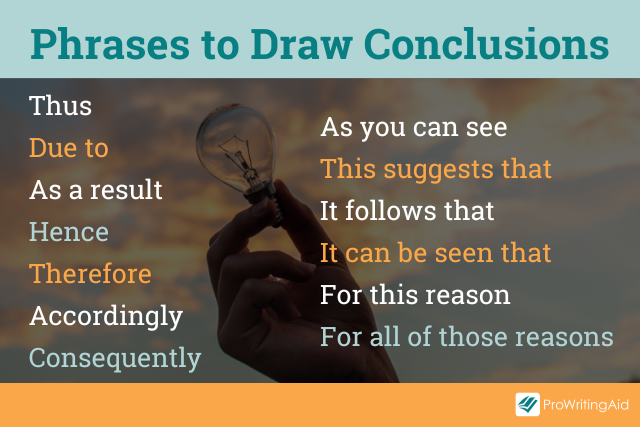

Sometimes, you’ll need to explain the impact or consequence of something you’ve just said.

When you’re drawing a conclusion from evidence you’ve presented, try using the following words:

As a result

Accordingly

As you can see

This suggests that

It follows that

It can be seen that

For this reason

For all of those reasons

Consequently

Example: “There wasn’t enough government funding to support the rest of the physics experiment. Thus , the team was forced to shut down their experiment in 1996.”

When introducing an idea that bolsters one you’ve already stated, or adds another important aspect to that same argument, you can use the following words:

What’s more

Not only…but also

Not to mention

To say nothing of

Another key point

Example: The volcanic eruption disrupted hundreds of thousands of people. Moreover , it impacted the local flora and fauna as well, causing nearly a hundred species to go extinct.

Often, you'll want to present two sides of the same argument. When you need to compare and contrast ideas, you can use the following words:

On the one hand / on the other hand

Alternatively

In contrast to

On the contrary

By contrast

In comparison

Example: On the one hand , the Black Death was undoubtedly a tragedy because it killed millions of Europeans. On the other hand , it created better living conditions for the peasants who survived.

Finally, when you’re introducing a new angle that contradicts your previous idea, you can use the following phrases:

Having said that

Differing from

In spite of

With this in mind

Provided that

Nevertheless

Nonetheless

Notwithstanding

Example: Shakespearean plays are classic works of literature that have stood the test of time. Having said that , I would argue that Shakespeare isn’t the most accessible form of literature to teach students in the twenty-first century.

Good essays include multiple types of logic. You can use a combination of the transitions above to create a strong, clear structure throughout the body of your essay.

Strong Verbs for Academic Writing

Verbs are especially important for writing clear essays. Often, you can convey a nuanced meaning simply by choosing the right verb.

You should use strong verbs that are precise and dynamic. Whenever possible, you should use an unambiguous verb, rather than a generic verb.

For example, alter and fluctuate are stronger verbs than change , because they give the reader more descriptive detail.

Here are some useful verbs that will help make your essay shine.

Verbs that show change:

Accommodate

Verbs that relate to causing or impacting something:

Verbs that show increase:

Verbs that show decrease:

Deteriorate

Verbs that relate to parts of a whole:

Comprises of

Is composed of

Constitutes

Encompasses

Incorporates

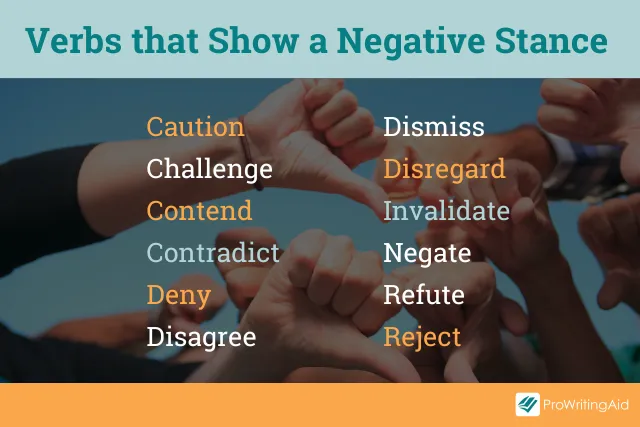

Verbs that show a negative stance:

Misconstrue

Verbs that show a positive stance:

Substantiate

Verbs that relate to drawing conclusions from evidence:

Corroborate

Demonstrate

Verbs that relate to thinking and analysis:

Contemplate

Hypothesize

Investigate

Verbs that relate to showing information in a visual format:

Useful Adjectives and Adverbs for Academic Essays

You should use adjectives and adverbs more sparingly than verbs when writing essays, since they sometimes add unnecessary fluff to sentences.

However, choosing the right adjectives and adverbs can help add detail and sophistication to your essay.

Sometimes you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is useful and should be taken seriously. Here are some adjectives that create positive emphasis:

Significant

Other times, you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is harmful or ineffective. Here are some adjectives that create a negative emphasis:

Controversial

Insignificant

Questionable

Unnecessary

Unrealistic

Finally, you might need to use an adverb to lend nuance to a sentence, or to express a specific degree of certainty. Here are some examples of adverbs that are often used in essays:

Comprehensively

Exhaustively

Extensively

Respectively

Surprisingly

Using these words will help you successfully convey the key points you want to express. Once you’ve nailed the body of your essay, it’s time to move on to the conclusion.

The conclusion of your paper is important for synthesizing the arguments you’ve laid out and restating your thesis.

In your concluding paragraph, try using some of these essay words:

In conclusion

To summarize

In a nutshell

Given the above

As described

All things considered

Example: In conclusion , it’s imperative that we take action to address climate change before we lose our coral reefs forever.

In addition to simply summarizing the key points from the body of your essay, you should also add some final takeaways. Give the reader your final opinion and a bit of a food for thought.

To place emphasis on a certain point or a key fact, use these essay words:

Unquestionably

Undoubtedly

Particularly

Importantly

Conclusively

It should be noted

On the whole

Example: Ada Lovelace is unquestionably a powerful role model for young girls around the world, and more of our public school curricula should include her as a historical figure.

These concluding phrases will help you finish writing your essay in a strong, confident way.

There are many useful essay words out there that we didn't include in this article, because they are specific to certain topics.

If you're writing about biology, for example, you will need to use different terminology than if you're writing about literature.

So how do you improve your vocabulary skills?

The vocabulary you use in your academic writing is a toolkit you can build up over time, as long as you take the time to learn new words.

One way to increase your vocabulary is by looking up words you don’t know when you’re reading.

Try reading more books and academic articles in the field you’re writing about and jotting down all the new words you find. You can use these words to bolster your own essays.

You can also consult a dictionary or a thesaurus. When you’re using a word you’re not confident about, researching its meaning and common synonyms can help you make sure it belongs in your essay.

Don't be afraid of using simpler words. Good essay writing boils down to choosing the best word to convey what you need to say, not the fanciest word possible.

Finally, you can use ProWritingAid’s synonym tool or essay checker to find more precise and sophisticated vocabulary. Click on weak words in your essay to find stronger alternatives.

There you have it: our compilation of the best words and phrases to use in your next essay . Good luck!

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

- TheFreeDictionary

- Word / Article

- Starts with

- Free toolbar & extensions

- Word of the Day

- Free content

es•say

- Anaya Rudolfo Alfonso

- Baldwin James Arthur

- Burroughs John

- Chesterton Gilbert Keith

- Cobbett William

- composition

- Crèvecoeur Michel Guillaume Jean de

- Cunninghame Graham

- disquisition

- dissertation

- espresso maker

- espresso shop

- esprit de corps

- esprit de l'escalier

- Espy James Pollard

- essay question

- Essence of spruce

- Essence of verbena

- essential amino acid

- essential care

- essential cargo

- Essential character

- essential chemicals

- essential communications traffic

- essential condition

- Essential disease

- essential element

- Essad Pasha

- Essad Pasha Toptani

- Essad Toptani

- Essai Fondé sur la Préférence du Patient

- Essais Cliniques en Lorraine

- Essais Cliniques et Validation

- Essais d'Aptitude Par Inter-Comparaison

- Essais Périodiques

- Essanay Film Manufacturing Company

- Essar Power Gujarat Ltd.

- Essar Shipping and Logistics Ltd.

- Essarts Club Archerie

- Essay and Short Answer Question

- Essay Concerning Human Understanding

- Essay editing

- Essay on Criticism

- Essay on Lucidity

- Essay Verification Engine

- Essay Writing Contest

- Essay Writing for the College Bound

- Essays in International Finance

- Essays on Philosophical Method

- Facebook Share

Flower Etymologies For Your Spring Garden

Pilfer: how to play and win, quiz: spot the misspelled word, games & quizzes.

New Challenges Every Day

Word of the Day

June 1, 2024

Get Word of the Day in your inbox!

Great Big List of Beautiful and Useless Words, Vol. 2

Rare and amusing insults, volume 3, why jaywalking is called jaywalking, 'gaslighting,' 'woke,' 'democracy,' and other top lookups, games & quizzes, grammar & usage, 7 pairs of commonly confused words, words commonly mispronounced, is 'irregardless' a real word, did we change the definition of 'literally', time traveler.

Find words from the year you were born … and beyond!

Video: Why Is There a 'C' in 'Indict'?

'nip it in the butt' or 'nip it in the bud', how to remember the spelling of 'definitely', word choices: a new video series from merriam-webster.

Browse the Dictionary

Browse the thesaurus.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

The Donald Trump I Saw on The Apprentice

For 20 years, i couldn’t say what i watched the former president do on the set of the show that changed everything. now i can..

On Jan. 8, 2004, just more than 20 years ago, the first episode of The Apprentice aired. It was called “Meet the Billionaire,” and 18 million people watched. The episodes that followed climbed to roughly 20 million each week. A staggering 28 million viewers tuned in to watch the first season finale. The series won an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Reality-Competition Program, and the Television Critics Association called it one of the best TV shows of the year, alongside The Sopranos and Arrested Development . The series—alongside its bawdy sibling, The Celebrity Apprentice —appeared on NBC in coveted prime-time slots for more than a decade.

The Apprentice was an instant success in another way too. It elevated Donald J. Trump from sleazy New York tabloid hustler to respectable household name. In the show, he appeared to demonstrate impeccable business instincts and unparalleled wealth, even though his businesses had barely survived multiple bankruptcies and faced yet another when he was cast. By carefully misleading viewers about Trump—his wealth, his stature, his character, and his intent—the competition reality show set about an American fraud that would balloon beyond its creators’ wildest imaginations.

I should know. I was one of four producers involved in the first two seasons. During that time, I signed an expansive nondisclosure agreement that promised a fine of $5 million and even jail time if I were to ever divulge what actually happened. It expired this year.

No one involved in The Apprentice —from the production company or the network, to the cast and crew—was involved in a con with malicious intent. It was a TV show , and it was made for entertainment . I still believe that. But we played fast and loose with the facts, particularly regarding Trump, and if you were one of the 28 million who tuned in, chances are you were conned.

As Trump answers for another of his alleged deception schemes in New York and gears up to try to persuade Americans to elect him again, in part thanks to the myth we created, I can finally tell you what making Trump into what he is today looked like from my side. Most days were revealing. Some still haunt me, two decades later.

Nearly everything I ever learned about deception I learned from my friend Apollo Robbins. He’s been called a professional pickpocket, but he’s actually a “perceptions expert.” Apollo has spent his life studying the psychology of how we distort other people’s perceptions of reality and has done so by picking pockets onstage for the entertainment of others. He is a master of deception, a skill that made him, back in the day, the so-called best-kept secret in Las Vegas. After “fanning” his marks with casual, unobtrusive touch designed to make them feel safe or at ease, Apollo determines where the items reside—the wallet inside a breast pocket, the Rolex fastened to a wrist—and he removes these items without detection. He’ll even tell you what he intends to steal before he does it. He does this not to hurt people or bewilder them with a puzzle but to challenge their maps of reality. The results are marvelous. A lot of magic is designed to appeal to people visually, but what he’s trying to affect is your mind, your moods, your perceptions.

As a producer working in unscripted, or “reality,” television, I have the same goal. Like Apollo, I want to entertain, make people joyful, maybe even challenge their ways of thinking. But because I often lack the cinematic power of a movie, with its visual pyrotechnics or rehearsed dialogue, I rely on shaping the perceptions of viewers, manipulating their maps of reality toward something I want them to think or feel.

The presumption is that reality TV is scripted. What actually happens is the illusion of reality by staging situations against an authentic backdrop. The more authentic it is to, say, have a 40-foot wave bearing down on a crab boat in the Bering Sea for Deadliest Catch , the more we can trick you into thinking a malevolent Russian trawler is out there messing with the crabber’s bait. There is a trick to it, and when it works, you feel as if you’re watching a scripted show. Although very few programs are out-and-out fake, there is deception at play in every single reality program. The producers and editors are ostensibly con artists, distracting you with grand notions while we steal from you your precious time.

But the real con that drove The Apprentice is far older than television. The “pig in the poke” comes from an idiom dating to 1555: “I’ll never buy a pig in a poke / There’s many a foul pig in a fair cloak.” It refers to the time-honored scam of selling a suckling pig at market but handing over a bag (the poke) to the purchaser, who never looks inside it. Eventually, he discovers he’s purchased something quite different.

Our show became a 21 st -century version. It’s a long con played out over a decade of watching Trump dominate prime time by shouting orders, appearing to lead, and confidently firing some of the most capable people on television, all before awarding one eligible person a job. Audiences responded to Trump’s arrogance, his perceived abilities and prescience, but mostly his confidence . The centerpiece to any confidence game is precisely that— confidence .

As I walk into my interview for The Apprentice , I inadvertently learn how important it is for every one of us involved to demonstrate confidence above all else.

I sit down with Jay Bienstock, the showrunner, who has one last producer position to fill and needs somebody capable and hardworking. His office is sparse, and the desk is strategically placed directly across from the couch, with a noticeable angle downward from his desk to whomever is seated across from him. (I’m recalling all of the quoted conversations here to the best of my ability; they are not verbatim.)